1. Introduction

Buoyancy-driven convection in porous media spans diverse applications, scales and flow regimes (Kong & Saar Reference Kong and Saar2013; Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017; Hewitt Reference Hewitt2020; Wood, He & Apte Reference Wood, He and Apte2020; De Paoli Reference De Paoli2023), including geothermal energy systems (Kohl et al. Reference Kohl, Evans, Hopkirk, Jung and Rybach1997; Saar Reference Saar2011; Scott, Driesner & Weis Reference Scott, Driesner and Weis2016), thermal energy storage (Mabrouk et al. Reference Mabrouk, Naji, Benim and Dhahri2022) and advanced high-temperature gas-cooled reactors (Bu et al. Reference Bu, Li, Ma, Sun, Zhang and Chen2020). Horton–Rogers–Lapwood convection (HRLC), the porous medium equivalent of Rayleigh–Bénard convection, describes the basic phenomenon of a porous medium bounded by a hot bottom surface and a cold top surface, as shown in figure 1(a) (Horton & Rogers Jr Reference Horton and Rogers1945; Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017). The HRLC has been extensively studied across scales, from Darcy to non-Darcy regimes, through numerical simulations (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Jiang, Chong, Zhu, Wan, Verzicco, Stevens, Lohse and Sun2020; Korba & Li Reference Korba and Li2022; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Fu and De Paoli2024) and laboratory experiments (Elder Reference Elder1967; Kladias & Prasad Reference Kladias and Prasad1991; Keene & Goldstein Reference Keene and Goldstein2015; Ataei-Dadavi et al. Reference Ataei-Dadavi, Chakkingal, Kenjeres, Kleijn and Tummers2019; Bavandla & Srinivasan Reference Bavandla and Srinivasan2025). However, direct observation of buoyancy-driven convection at field scales remains challenging, often relying on indirect methods such as magnetotelluric imaging of high-conductivity zones (Samrock et al. Reference Samrock, Grayver, Eysteinsson and Saar2018).

Numerous studies use Darcy-scale governing equations to describe the macroscopic dynamics of HRLC, averaging model properties (e.g. thermo-physical properties, porosities and permeabilities) over a representative elementary volume (REV) (Whitaker Reference Whitaker2013; Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017; De Paoli Reference De Paoli2023). These models simplify domain geometry and the dynamics by spatially averaging properties relevant to momentum and heat transfer, typically assuming thermal equilibrium, inertia-free conditions. Despite strong convection, many models reduce to Darcy–Oberbeck–Boussinesq (DOB) equations, neglecting inertial terms and the sub-REV dynamics at small Darcy numbers (Hewitt, Neufeld & Lister Reference Hewitt, Neufeld and Lister2012; Korba & Li Reference Korba and Li2022). To address situations where inertial effects are non-negligible, extensions of the DOB framework incorporate Brinkman and Forchheimer terms (Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017) or local thermal non-equilibrium models (Bear Reference Bear2013; Karani & Huber Reference Karani and Huber2017). These approaches allow for more accurate representation of velocity and temperature fields in regimes where Darcy’s assumptions begin to break down. In parallel, to represent sub-REV processes within the REV-scale framework, closure models – such as dispersion tensors (Bear Reference Bear2013) – are introduced into the governing equations. These additions help capture the effects of microscale heterogeneities and mixing that are otherwise averaged out in traditional Darcy-scale models. The reliability and applicability of such models are typically assessed via laboratory experiments and direct numerical simulations (DNS), which, despite offering valuable insights, are constrained by spatial resolution, computational cost and the persistent challenge of upscaling microscale processes to the REV scale.

To characterise the HRLC dynamics across scales, key dimensionless groups serve as fundamental model inputs, derived via dimensional analysis (Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017). The dimensionless fluid Rayleigh number (Ra

![]() $_{\mkern -2mu f}$

), defined as

$_{\mkern -2mu f}$

), defined as

characterises buoyancy-driven flow in the absence of a porous medium, where

![]() $g$

$g$

![]() $(\text{L}\,\text{T}^{- 2})$

is gravitational acceleration,

$(\text{L}\,\text{T}^{- 2})$

is gravitational acceleration,

![]() $\beta _{\mkern -2mu f}$

$\beta _{\mkern -2mu f}$

![]() $(\text{K}^{-1})$

the fluid thermal expansion coefficient,

$(\text{K}^{-1})$

the fluid thermal expansion coefficient,

![]() $\Delta T = T_{\mkern -2mu H} - T_{\mkern -2mu C}$

$\Delta T = T_{\mkern -2mu H} - T_{\mkern -2mu C}$

![]() $(\text{K})$

the temperature difference between the hot and cold boundaries,

$(\text{K})$

the temperature difference between the hot and cold boundaries,

![]() $H$

$H$

![]() $(\text{L})$

the domain height,

$(\text{L})$

the domain height,

![]() $\alpha _{\mkern -2mu f}$

$\alpha _{\mkern -2mu f}$

![]() $(\text{L}^2\,\text{T}^{- 1})$

the fluid’s thermal diffusivity and

$(\text{L}^2\,\text{T}^{- 1})$

the fluid’s thermal diffusivity and

![]() $\nu$

$\nu$

![]() $(\text{L}^2\,\text{T}^{- 1})$

its kinematic viscosity. Here, Ra

$(\text{L}^2\,\text{T}^{- 1})$

its kinematic viscosity. Here, Ra

![]() $_{\mkern -2mu f}$

quantifies the competition between buoyancy forces and the combined damping effects of viscosity and thermal diffusion.

$_{\mkern -2mu f}$

quantifies the competition between buoyancy forces and the combined damping effects of viscosity and thermal diffusion.

In the presence of porous media, buoyancy-driven flow is typically characterised by the so-called Darcy–Rayleigh number (

![]() $Ra^*$

), which incorporates the intrinsic permeability

$Ra^*$

), which incorporates the intrinsic permeability

![]() $K$

$K$

![]() $(\text{L}^2)$

of the porous medium under laminar flow conditions. It is defined as (Combarnous & Bories Reference Combarnous and Bories1975)

$(\text{L}^2)$

of the porous medium under laminar flow conditions. It is defined as (Combarnous & Bories Reference Combarnous and Bories1975)

where Da is the dimensionless Darcy number, given by

![]() $\textit {Da} = K / H^2$

, and

$\textit {Da} = K / H^2$

, and

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu f} / k_{\mkern -2mu m} = \lambda$

is the ratio of fluid to effective thermal conductivities of the porous medium. The Darcy number relates the medium’s permeability to the characteristic length scale of the system, providing a measure of how strongly the porous structure constrains fluid flow. A decreasing Darcy number indicates that the porous medium becomes a porous continuum, assuming the intra-porous dynamics is effectively averaged out on the characteristic length scale, as demonstrated in figure 16. Since the effective diffusivity

$k_{\mkern -2mu f} / k_{\mkern -2mu m} = \lambda$

is the ratio of fluid to effective thermal conductivities of the porous medium. The Darcy number relates the medium’s permeability to the characteristic length scale of the system, providing a measure of how strongly the porous structure constrains fluid flow. A decreasing Darcy number indicates that the porous medium becomes a porous continuum, assuming the intra-porous dynamics is effectively averaged out on the characteristic length scale, as demonstrated in figure 16. Since the effective diffusivity

![]() $\alpha _{\mkern -2mu m} = ( {k_{\mkern -2mu m}}/{(\rho c_p)_f})$

is an output of the system’s geometry, studies typically use the solid-to-fluid thermal conductivity ratio (

$\alpha _{\mkern -2mu m} = ( {k_{\mkern -2mu m}}/{(\rho c_p)_f})$

is an output of the system’s geometry, studies typically use the solid-to-fluid thermal conductivity ratio (

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu r} = k_{\mkern -2mu s} / k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) and the volumetric heat capacity ratio (

$ k_{\mkern -2mu r} = k_{\mkern -2mu s} / k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) and the volumetric heat capacity ratio (

![]() $ \sigma = (\rho c_{\mkern -2mu p})_{\mkern -2mu s} / (\rho c_{\mkern -2mu p})_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) as input parameters. Note that

$ \sigma = (\rho c_{\mkern -2mu p})_{\mkern -2mu s} / (\rho c_{\mkern -2mu p})_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) as input parameters. Note that

![]() $\alpha _{\mkern -2mu m}$

is expressed with

$\alpha _{\mkern -2mu m}$

is expressed with

![]() $(\rho c_p)_f$

in the denominator, because the advective heat transport in the porous energy equation is carried solely by the fluid phase, while the solid enters only through conduction and storage terms. Here,

$(\rho c_p)_f$

in the denominator, because the advective heat transport in the porous energy equation is carried solely by the fluid phase, while the solid enters only through conduction and storage terms. Here,

![]() $\rho$

(ML

$\rho$

(ML

![]() $^{-3}$

) is the density,

$^{-3}$

) is the density,

![]() $c_p$

(L

$c_p$

(L

![]() $^2$

T

$^2$

T

![]() $^{-2}$

K

$^{-2}$

K

![]() $^{-1}$

) is the isobaric heat capacity.

$^{-1}$

) is the isobaric heat capacity.

The dimensionless fluid Prandtl number (

![]() $\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) is defined as

$\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) is defined as

and quantifies the ratio of momentum to thermal diffusivity, describing the fluid’s relative viscous and thermal transport behaviour.

Wang & Bejan (Reference Wang and Bejan1987) proposed that under strongly convective conditions in porous media, the buoyancy force is balanced by the inertial resistance described by the Forchheimer term, leading to the relation

where

![]() $c_{\mkern -2mu F}$

is the dimensionless form drag coefficient of the porous matrix. Based on this balance, they introduced a new dimensionless group, the porous-medium Prandtl number (

$c_{\mkern -2mu F}$

is the dimensionless form drag coefficient of the porous matrix. Based on this balance, they introduced a new dimensionless group, the porous-medium Prandtl number (

![]() $\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu p}$

), defined as

$\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu p}$

), defined as

which accounts for the permeability, form drag and the ratio of thermal diffusivities of the fluid and the porous medium.

A key output of natural convection studies is the heat transfer efficiency, quantified by the dimensionless Nusselt number (

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

) that represents the ratio of total heat transfer (convective + conductive) to purely conductive transfer

$\textit{Nu}$

) that represents the ratio of total heat transfer (convective + conductive) to purely conductive transfer

Elder (Reference Elder1967) experimentally studied HRLC in uniform granular porous media and a Hele-Shaw (HS) cell. Convective heat transport was examined via the

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

–

$\textit{Nu}$

–

![]() $Ra^*$

relationship. Convection onset occurred at

$Ra^*$

relationship. Convection onset occurred at

![]() $Ra$

$Ra$

![]() $^{*}\approx 40$

(

$^{*}\approx 40$

(

![]() $\pm$

10 %), closely matching the theoretical prediction of

$\pm$

10 %), closely matching the theoretical prediction of

![]() $4\pi ^2$

from linear stability analysis of a steady Darcy-scale system (Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017). Beyond onset,

$4\pi ^2$

from linear stability analysis of a steady Darcy-scale system (Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017). Beyond onset,

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

was shown to scale with

$\textit{Nu}$

was shown to scale with

![]() $Ra^*$

. For media of larger grains, the

$Ra^*$

. For media of larger grains, the

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

–

$\textit{Nu}$

–

![]() $Ra^*$

trend flattened between

$Ra^*$

trend flattened between

![]() $Ra^* = 10^2$

and

$Ra^* = 10^2$

and

![]() $Ra^* = 10^3$

, indicating a breakdown of the inertia-free assumption as the boundary layer (BL) approaches the porous-medium scale. Buretta & Berman (Reference Buretta and Berman1976) experimentally showed that a Rayleigh number based on fluid-saturated bed properties effectively correlates data across permeable beds, provided that the pore size remains below the BL thickness. Kladias & Prasad (Reference Kladias and Prasad1991) extended earlier findings by examining the influence of porosity (fluid volume fraction,

$Ra^* = 10^3$

, indicating a breakdown of the inertia-free assumption as the boundary layer (BL) approaches the porous-medium scale. Buretta & Berman (Reference Buretta and Berman1976) experimentally showed that a Rayleigh number based on fluid-saturated bed properties effectively correlates data across permeable beds, provided that the pore size remains below the BL thickness. Kladias & Prasad (Reference Kladias and Prasad1991) extended earlier findings by examining the influence of porosity (fluid volume fraction,

![]() $ \varphi$

(–), fluid Prandtl number

$ \varphi$

(–), fluid Prandtl number

![]() $ \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}$

, Darcy number

$ \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}$

, Darcy number

![]() $ Da$

, and relative thermal conductivity ratio

$ Da$

, and relative thermal conductivity ratio

![]() $ \lambda = k_{\mkern -2mu f}/k_{\mkern -2mu m}$

. Their results are consistent with the Darcy–Brinkman–Forchheimer (DBF) model, showing increased heat transfer with larger

$ \lambda = k_{\mkern -2mu f}/k_{\mkern -2mu m}$

. Their results are consistent with the Darcy–Brinkman–Forchheimer (DBF) model, showing increased heat transfer with larger

![]() $ Da$

(

$ Da$

(

![]() $ Da = \textit {O}(10^{-6})$

–

$ Da = \textit {O}(10^{-6})$

–

![]() $\textit {O}(10^{-4})$

), higher modified Rayleigh numbers

$\textit {O}(10^{-4})$

), higher modified Rayleigh numbers

![]() $ Ra^*$

(

$ Ra^*$

(

![]() $ Ra^* = \textit {O}(10^{0})$

–

$ Ra^* = \textit {O}(10^{0})$

–

![]() $\textit {O}(10^{6})$

) and elevated

$\textit {O}(10^{6})$

) and elevated

![]() $ \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}$

(e.g. comparing water and glycerol). However, their measurements suggest that the DBF model underestimates the stabilising effect of highly conductive solid matrices, resulting in lower Nusselt numbers than predicted. Regarding the asymptotic, inertial regime, Keene & Goldstein (Reference Keene and Goldstein2015) report in a packed-bed experiment a scaling of

$ \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}$

(e.g. comparing water and glycerol). However, their measurements suggest that the DBF model underestimates the stabilising effect of highly conductive solid matrices, resulting in lower Nusselt numbers than predicted. Regarding the asymptotic, inertial regime, Keene & Goldstein (Reference Keene and Goldstein2015) report in a packed-bed experiment a scaling of

![]() $ \textit{Nu} \propto Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}^{0.298}$

in the classical regime, and

$ \textit{Nu} \propto Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}^{0.298}$

in the classical regime, and

![]() $ \textit{Nu} \propto (Ra^*)^{0.319}$

using the Darcy–Rayleigh scaling at

$ \textit{Nu} \propto (Ra^*)^{0.319}$

using the Darcy–Rayleigh scaling at

![]() $ Da = \textit {O}(10^{-5})$

. Bavandla & Srinivasan (Reference Bavandla and Srinivasan2025) experimentally examined the effect of

$ Da = \textit {O}(10^{-5})$

. Bavandla & Srinivasan (Reference Bavandla and Srinivasan2025) experimentally examined the effect of

![]() $\lambda$

on HRLC at Darcy numbers (

$\lambda$

on HRLC at Darcy numbers (

![]() $Da = \textit {O}(10^{-8})$

–

$Da = \textit {O}(10^{-8})$

–

![]() $\textit {O}(10^{-7})$

) in a packed bed with

$\textit {O}(10^{-7})$

) in a packed bed with

![]() $\lambda \leqslant \textit {O}(10^{-2})$

. To account for inertial effects, they use the porous-medium Prandtl number (

$\lambda \leqslant \textit {O}(10^{-2})$

. To account for inertial effects, they use the porous-medium Prandtl number (

![]() $\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu p}$

) and observe that the transition to inertial HRLC occurs when

$\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu p}$

) and observe that the transition to inertial HRLC occurs when

![]() $Ra^* \sim \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu p}$

. Deviations from this criterion are attributed to violations of the porous-continuum assumption at large Darcy numbers.

$Ra^* \sim \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu p}$

. Deviations from this criterion are attributed to violations of the porous-continuum assumption at large Darcy numbers.

Figure 1. (a) Fully saturated porous domain with solid inclusions (black) selected to study HRLC. Relevant geometric scales are indicated and presented in table 2. (b) Benchmark model used in § 2.2 after Merrikh & Lage (Reference Merrikh and Lage2005). The domain hosts 16 unit cells (dotted), each unit cell has length

![]() $a + 2b$

with

$a + 2b$

with

![]() $a = 3b$

and

$a = 3b$

and

![]() $b = 12$

lattice nodes.

$b = 12$

lattice nodes.

Direct numerical simulations have significantly advanced the understanding of natural convection by allowing controlled exploration of parameter spaces. Merrikh & Lage (Reference Merrikh and Lage2005) analysed solid geometry effects on convection using a two-dimensional model with square rods in a regular array. Their configuration applied a temperature gradient perpendicular to gravity, as illustrated in figure 1(b), deviating from the classic HRLC set-up shown in figure 1(a). They showed that heat transfer is strongly influenced by the number of blocks and resulting permeability, affecting the Darcy number (

![]() $Da$

). In models similar to figure 1(b), Raji et al. (Reference Raji, Hasnaoui, Naïmi, Slimani and Ouazzani2012) investigated porosities (

$Da$

). In models similar to figure 1(b), Raji et al. (Reference Raji, Hasnaoui, Naïmi, Slimani and Ouazzani2012) investigated porosities (

![]() $ \varphi$

) from 90 % to 58 %, Darcy numbers (

$ \varphi$

) from 90 % to 58 %, Darcy numbers (

![]() $ Da$

) of

$ Da$

) of

![]() $ \textit {O}(10^{-5})$

–

$ \textit {O}(10^{-5})$

–

![]() $ \textit {O}(10^{-6})$

and conductivity ratios (

$ \textit {O}(10^{-6})$

and conductivity ratios (

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

) ranging from

$ k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

) ranging from

![]() $ 10^{-3}$

to

$ 10^{-3}$

to

![]() $ 10^{3}$

, focusing on solid block fragmentation and thermal transport. For

$ 10^{3}$

, focusing on solid block fragmentation and thermal transport. For

![]() $10^{-1} \leqslant k_{\mkern -2mu r} \leqslant 10^{1}$

,

$10^{-1} \leqslant k_{\mkern -2mu r} \leqslant 10^{1}$

,

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

decreased significantly with increasing

$\textit{Nu}$

decreased significantly with increasing

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

. For

$k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

. For

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu r} \in (-\infty , 10^{-2}] \cup [10^{2}, \infty )$

,

$ k_{\mkern -2mu r} \in (-\infty , 10^{-2}] \cup [10^{2}, \infty )$

,

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

remained largely insensitive to

$\textit{Nu}$

remained largely insensitive to

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

. Karani & Huber (Reference Karani and Huber2017) performed DNS of HRLC at the onset of convection in a square block array with porosity

$k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

. Karani & Huber (Reference Karani and Huber2017) performed DNS of HRLC at the onset of convection in a square block array with porosity

![]() $\varphi = 50\,\%$

, and compared the results with Darcy-scale simulations using the DOB model, incorporating both local thermal equilibrium and local thermal non-equilibrium formulations. For Ra

$\varphi = 50\,\%$

, and compared the results with Darcy-scale simulations using the DOB model, incorporating both local thermal equilibrium and local thermal non-equilibrium formulations. For Ra

![]() $^* \leqslant 200$

, convection onset deviated from

$^* \leqslant 200$

, convection onset deviated from

![]() $4\pi ^2$

when

$4\pi ^2$

when

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r} \neq 1$

. For

$k_{\mkern -2mu r} \neq 1$

. For

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 1/13$

, the onset occurs earlier (

$k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 1/13$

, the onset occurs earlier (

![]() $\sim 35$

) and

$\sim 35$

) and

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

increases more steeply than in homogeneous models (

$\textit{Nu}$

increases more steeply than in homogeneous models (

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 1$

). In contrast, for

$k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 1$

). In contrast, for

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 50$

, convection sets in later, and

$k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 50$

, convection sets in later, and

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

exhibits a more gradual increase. When

$\textit{Nu}$

exhibits a more gradual increase. When

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 1$

, their results matched the Darcy-scale simulations at the onset of convection. In a follow up study, Karani et al. (Reference Karani, Rashtbehesht, Huber and Magin2017) introduced a fractional-order derivative model in the heat equation to refine Darcy-scale simulations and align them with pore-scale results. The fractional-order model characterises the intermediate behaviours between advective and diffusive regimes and accounts for macroscopic thermal dispersion effects. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Jiang, Chong, Zhu, Wan, Verzicco, Stevens, Lohse and Sun2020) highlight the effect of porosity on heat transfer, driven by competing effects of flow coherence and porous resistance. They simulated the transition from pure Rayleigh–Bénard convection (RBC) to porous convection in square arrays, 45° rotated arrays and random porous media at

$k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 1$

, their results matched the Darcy-scale simulations at the onset of convection. In a follow up study, Karani et al. (Reference Karani, Rashtbehesht, Huber and Magin2017) introduced a fractional-order derivative model in the heat equation to refine Darcy-scale simulations and align them with pore-scale results. The fractional-order model characterises the intermediate behaviours between advective and diffusive regimes and accounts for macroscopic thermal dispersion effects. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Jiang, Chong, Zhu, Wan, Verzicco, Stevens, Lohse and Sun2020) highlight the effect of porosity on heat transfer, driven by competing effects of flow coherence and porous resistance. They simulated the transition from pure Rayleigh–Bénard convection (RBC) to porous convection in square arrays, 45° rotated arrays and random porous media at

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 1$

with

$k_{\mkern -2mu r} = 1$

with

![]() $\varphi \geqslant 67\,\%$

. For high porosity (

$\varphi \geqslant 67\,\%$

. For high porosity (

![]() $\varphi \geqslant 70\,\%$

), their results showed that porous media stabilise convection cells, enhancing heat transfer by over 10 % compared with pure RBC, indicating that porous drag is not always dominant. The

$\varphi \geqslant 70\,\%$

), their results showed that porous media stabilise convection cells, enhancing heat transfer by over 10 % compared with pure RBC, indicating that porous drag is not always dominant. The

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

–

$\textit{Nu}$

–

![]() $Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}$

scaling exhibit two regimes: a lower regime (

$Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}$

scaling exhibit two regimes: a lower regime (

![]() $\textit{Nu} \propto {Ra}_{\mkern -2mu f}^{0.65}$

at

$\textit{Nu} \propto {Ra}_{\mkern -2mu f}^{0.65}$

at

![]() $\varphi = 75\,\%$

) and an upper regime that converges to the pure RBC scaling law (

$\varphi = 75\,\%$

) and an upper regime that converges to the pure RBC scaling law (

![]() $\textit{Nu} \propto {Ra}_{\mkern -2mu f}^{0.3}$

). They predict that the transition occurs when the thermal BL thickness (

$\textit{Nu} \propto {Ra}_{\mkern -2mu f}^{0.3}$

). They predict that the transition occurs when the thermal BL thickness (

![]() $\delta _{\textit{th}}$

) equals the pore-throat length (

$\delta _{\textit{th}}$

) equals the pore-throat length (

![]() $l_{\textit{pore}}$

), calculated as

$l_{\textit{pore}}$

), calculated as

![]() $\delta _{\textit{th}} = H / (2\textit{Nu})$

under the assumption of a perfectly mixed domain. Korba & Li (Reference Korba and Li2022) studied conjugate heat transfer in a square array of square-shaped porous media with porosities

$\delta _{\textit{th}} = H / (2\textit{Nu})$

under the assumption of a perfectly mixed domain. Korba & Li (Reference Korba and Li2022) studied conjugate heat transfer in a square array of square-shaped porous media with porosities

![]() $75\,\% \geqslant \varphi \geqslant 36\,\%$

, using DNS and comparing results with DOB models. They found that pore-scale parameters strongly affect the

$75\,\% \geqslant \varphi \geqslant 36\,\%$

, using DNS and comparing results with DOB models. They found that pore-scale parameters strongly affect the

![]() $ \textit{Nu}$

–

$ \textit{Nu}$

–

![]() $ Ra^*$

scaling, with DNS yielding

$ Ra^*$

scaling, with DNS yielding

![]() $ \textit{Nu} \propto (Ra^{*})^{0.319}$

at high

$ \textit{Nu} \propto (Ra^{*})^{0.319}$

at high

![]() $ Ra$

, while the DOB model predicts a steeper scaling of

$ Ra$

, while the DOB model predicts a steeper scaling of

![]() $ \textit{Nu} \propto (Ra^{*})^{0.9}$

. This discrepancy is likely attributed to the small Darcy number assumption in the DOB model, which ensures that

$ \textit{Nu} \propto (Ra^{*})^{0.9}$

. This discrepancy is likely attributed to the small Darcy number assumption in the DOB model, which ensures that

![]() $ Ra^* \ll \textit{Pr}_{\!p}$

across all cases, thereby justifying the exclusion of inertial effects.

$ Ra^* \ll \textit{Pr}_{\!p}$

across all cases, thereby justifying the exclusion of inertial effects.

In the context of pure hydrodynamics in porous media composed of cylinder arrays, Khalifa, Pocher & Tilton (Reference Khalifa, Pocher and Tilton2020) used DNS to investigate the transition from laminar to inertial flows. For staggered configurations, they examined porosities ranging from 90 % to 30 % and identified two asymptotic dynamical regimes: laminar flow at low Reynolds numbers (Darcy regime) and vortex shedding at high Reynolds numbers, using the cylinder diameter as the characteristic length scale. Between these, they defined intermediate regimes referred to as the transition and Forchheimer regimes. As porosity decreases, the laminar regime extends to higher Reynolds numbers, and the transition regime broadens. However, below 40 % porosity, they observed a marked shift: the Forchheimer regime vanishes, and vortex shedding emerges directly from an early inertial regime.

Despite extensive experimental and numerical studies on HRLC, several limitations remain. Many experiments and simulations apply the Darcy–Rayleigh scaling well into the inertial regime, even though this scaling inherently arises from a force balance between porous drag and buoyancy, making it unsuitable for capturing inertial effects. While experiments of packed beds offer valuable domain-scale data, their opacity limits the direct observation of pore- to domain-scale interactions, particularly during the onset of inertial convection. Direct numerical simulations can capture these effects but are typically performed in highly porous media (

![]() $\varphi \gt 45 \,\%$

), leaving lower-porosity cases underexplored. Furthermore, many studies use square arrays aligned with the forcing direction, which reduces tortuosity effects and introduces pure-fluid layers at the domain boundaries.

$\varphi \gt 45 \,\%$

), leaving lower-porosity cases underexplored. Furthermore, many studies use square arrays aligned with the forcing direction, which reduces tortuosity effects and introduces pure-fluid layers at the domain boundaries.

Karani et al. (Reference Karani, Rashtbehesht, Huber and Magin2017) showed that the solid-to-fluid conductivity ratio (

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu r} = k_{\mkern -2mu s} / k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) significantly affects the onset of convection. For

$ k_{\mkern -2mu r} = k_{\mkern -2mu s} / k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) significantly affects the onset of convection. For

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu r} \lt 1$

, representing insulating solids, the system becomes more prone to instability, and convection initiates at lower Darcy–Rayleigh numbers. Conversely, for

$ k_{\mkern -2mu r} \lt 1$

, representing insulating solids, the system becomes more prone to instability, and convection initiates at lower Darcy–Rayleigh numbers. Conversely, for

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu r} \gt 1$

, heat is more efficiently conducted through the solid matrix, delaying the onset. Korba & Li (Reference Korba and Li2022) investigated the influence of both

$ k_{\mkern -2mu r} \gt 1$

, heat is more efficiently conducted through the solid matrix, delaying the onset. Korba & Li (Reference Korba and Li2022) investigated the influence of both

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

and the volumetric heat capacity ratio

$ k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

and the volumetric heat capacity ratio

![]() $ \sigma$

in the asymptotic, inertial regime at

$ \sigma$

in the asymptotic, inertial regime at

![]() $ Ra^* \gt 10^3$

. Wang & Bejan (Reference Wang and Bejan1987) propose a transition criterion from laminar to inertial HRLC at

$ Ra^* \gt 10^3$

. Wang & Bejan (Reference Wang and Bejan1987) propose a transition criterion from laminar to inertial HRLC at

![]() $Ra^* \sim \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu p}$

.

$Ra^* \sim \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu p}$

.

The objective of this study is to understand how porosity and diffusivity contrasts between the solid and fluid phases affect the transition from laminar to inertial HRLC. A central question is how local instabilities govern the global transition to an inertia-driven regime. This is achieved using a lattice Boltzmann model that resolves the Navier–Stokes–Fourier dynamics. Simulations are conducted in a square porous cavity featuring a 45° oriented staggered cylinder array, with porosity decreasing from 43 % to 33 %. Half-cylinders are placed along the cavity walls to embed the porous structure into the thermal BLs (figure 1).

The study begins by analysing purely hydrodynamic flow to understand how inertial effects emerge at the pore scale and influence domain-scale behaviour. From this, a local criterion for inertial flow is derived and applied statistically across the domain to estimate the fraction of pores required to trigger global transition. We then explore how decreasing porosity affects this transition, first in pure hydrodynamics and then in HRLC. The hydrodynamic analysis provides a controlled basis to isolate the influence of thermal conductivity contrast

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

on the onset of inertial convection. Finally, we examine the combined role of porosity and conductivity ratio across laminar and inertial regimes using a Darcy–Forchheimer framework. Although the geometry is idealised and isotropic, the approach captures key mechanisms governing porous convection.

$ k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

on the onset of inertial convection. Finally, we examine the combined role of porosity and conductivity ratio across laminar and inertial regimes using a Darcy–Forchheimer framework. Although the geometry is idealised and isotropic, the approach captures key mechanisms governing porous convection.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the porous model, governing equations and lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) implementation, along with benchmarking. Section 3 establishes a hydrodynamic and convective baseline at 43 % porosity, then analyses the transition to inertial HRLC in a homogeneous setting. Section 4 investigates how the porosity and conductivity ratio

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

modulate inertial transitions. The combined impact of the porosity and conductivity ratio is then assessed within the Darcy–Forchheimer framework and discussed using the concept of plume-scale confinement

$k_{\mkern -2mu r}$

modulate inertial transitions. The combined impact of the porosity and conductivity ratio is then assessed within the Darcy–Forchheimer framework and discussed using the concept of plume-scale confinement

![]() $\varLambda$

(Noto, Letelier & Ulloa Reference Noto, Letelier and Ulloa2024). Section 5 concludes with the key findings and their implications for inertial porous convection.

$\varLambda$

(Noto, Letelier & Ulloa Reference Noto, Letelier and Ulloa2024). Section 5 concludes with the key findings and their implications for inertial porous convection.

2. Methods

2.1. Governing equations, Navier–Stokes–Fourier system

The governing dynamics in pore-scale HRLC is fully described by mass, momentum and energy conservation for an incompressible fluid, following the low-Mach-number assumption. We express the equations in dimensionless form under the Boussinesq approximation, which considers density variations only in the buoyancy term. To achieve this, it is necessary to define characteristic quantities, including a characteristic velocity

![]() $u_{\mkern -2mu 0}$

(L T−1), and time scale

$u_{\mkern -2mu 0}$

(L T−1), and time scale

![]() $t_{\mkern -2mu 0}$

(T). Anticipating the role of inertia, we employ a free-fall velocity scale derived from the balance between inertia and buoyancy at the system’s quasi-steady state

$t_{\mkern -2mu 0}$

(T). Anticipating the role of inertia, we employ a free-fall velocity scale derived from the balance between inertia and buoyancy at the system’s quasi-steady state

Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

(L T−1) represents the fluid’s velocity,

$\boldsymbol{u}$

(L T−1) represents the fluid’s velocity,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla}$

$\boldsymbol{\nabla}$

![]() $(\text{L}^{-1})$

denotes the spatial gradient and

$(\text{L}^{-1})$

denotes the spatial gradient and

![]() $\Delta T$

is the imposed temperature difference between the accelerated parcel of fluid and its reference temperature. This relationship leads us to define a velocity scale as the free-fall velocity

$\Delta T$

is the imposed temperature difference between the accelerated parcel of fluid and its reference temperature. This relationship leads us to define a velocity scale as the free-fall velocity

where

![]() $H$

is a characteristic length of the domain. The associated convective characteristic time scale is then

$H$

is a characteristic length of the domain. The associated convective characteristic time scale is then

\begin{align} t_{\,\mkern -2mu 0} = \sqrt {\frac {H}{g \beta _{\mkern -2mu f} \Delta T}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} t_{\,\mkern -2mu 0} = \sqrt {\frac {H}{g \beta _{\mkern -2mu f} \Delta T}}. \end{align}

The resulting dimensionless, incompressible system retains the essential balance between convective and diffusive transport, governed by the Rayleigh number (Ra

![]() $_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) and Prandtl number ({Pr}

$_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) and Prandtl number ({Pr}

![]() $_{\mkern -2mu f}$

), and is given by (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Jiang, Chong, Zhu, Wan, Verzicco, Stevens, Lohse and Sun2020) as follows.

$_{\mkern -2mu f}$

), and is given by (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Jiang, Chong, Zhu, Wan, Verzicco, Stevens, Lohse and Sun2020) as follows.

Continuity equation

Momentum conservation (incompressible Navier–Stokes equation)

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \boldsymbol{u}}{\partial t} + (\boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol {\cdot }\boldsymbol {\nabla }) \boldsymbol{u} = -\boldsymbol{\nabla }p + \sqrt {\frac {\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}}{Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}}} {\nabla} ^2 \boldsymbol{u} + \theta _{\mkern -2mu f} \boldsymbol{e}_z . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \boldsymbol{u}}{\partial t} + (\boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol {\cdot }\boldsymbol {\nabla }) \boldsymbol{u} = -\boldsymbol{\nabla }p + \sqrt {\frac {\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}}{Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}}} {\nabla} ^2 \boldsymbol{u} + \theta _{\mkern -2mu f} \boldsymbol{e}_z . \end{equation}

Heat conservation in fluid

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \theta _{\mkern -2mu f}}{\partial t} + \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot } \boldsymbol{\nabla }\theta _{\mkern -2mu f} = \sqrt {\frac {1}{Ra_{\mkern -2mu f} \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}}} {\nabla} ^2 \theta _{\mkern -2mu f} . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\partial \theta _{\mkern -2mu f}}{\partial t} + \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot } \boldsymbol{\nabla }\theta _{\mkern -2mu f} = \sqrt {\frac {1}{Ra_{\mkern -2mu f} \textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}}} {\nabla} ^2 \theta _{\mkern -2mu f} . \end{equation}

Heat conservation in solid

Here,

![]() $\theta _{\mkern -2mu f}$

and

$\theta _{\mkern -2mu f}$

and

![]() $\theta _{\mkern -2mu s}$

represent the non-dimensional temperatures in the fluid and solid, scaled by

$\theta _{\mkern -2mu s}$

represent the non-dimensional temperatures in the fluid and solid, scaled by

![]() $\Delta T$

, respectively, while

$\Delta T$

, respectively, while

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }p$

denotes the non-dimensional pressure gradient, scaled by the dynamic pressure scale

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }p$

denotes the non-dimensional pressure gradient, scaled by the dynamic pressure scale

![]() $\rho _{\mkern -2mu 0} (H/t_{\mkern -2mu 0})^2$

. The dimensionless parameter

$\rho _{\mkern -2mu 0} (H/t_{\mkern -2mu 0})^2$

. The dimensionless parameter

![]() $\alpha _{\mkern -2mu r} = \alpha _{\mkern -2mu s} / \alpha _{\mkern -2mu f}$

represents the ratio of solid to fluid thermal diffusivity.

$\alpha _{\mkern -2mu r} = \alpha _{\mkern -2mu s} / \alpha _{\mkern -2mu f}$

represents the ratio of solid to fluid thermal diffusivity.

At the fluid–solid interface

![]() $ \varOmega$

, with normal vector

$ \varOmega$

, with normal vector

![]() $ \boldsymbol{n}$

, the following boundary conditions are imposed in the porous domain: (i) no slip for velocity,

$ \boldsymbol{n}$

, the following boundary conditions are imposed in the porous domain: (i) no slip for velocity,

![]() $ \boldsymbol{u} = 0$

; (ii) continuity of temperature,

$ \boldsymbol{u} = 0$

; (ii) continuity of temperature,

![]() $ \theta _{\mkern -2mu f} = \theta _{\mkern -2mu s}$

; and (iii) continuity of normal heat flux,

$ \theta _{\mkern -2mu f} = \theta _{\mkern -2mu s}$

; and (iii) continuity of normal heat flux,

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu f} ( {\partial \theta _{\mkern -2mu f}}/{\partial \boldsymbol{n}}) = k_{\mkern -2mu s} ( {\partial \theta _{\mkern -2mu s}}/{\partial \boldsymbol{n}})$

, where

$ k_{\mkern -2mu f} ( {\partial \theta _{\mkern -2mu f}}/{\partial \boldsymbol{n}}) = k_{\mkern -2mu s} ( {\partial \theta _{\mkern -2mu s}}/{\partial \boldsymbol{n}})$

, where

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

and

$ k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

and

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu s}$

denote the thermal conductivities of the fluid and solid phases, respectively. Additionally, the top and bottom walls are held at constant temperatures

$ k_{\mkern -2mu s}$

denote the thermal conductivities of the fluid and solid phases, respectively. Additionally, the top and bottom walls are held at constant temperatures

![]() $ T_{\mkern -2mu H}$

and

$ T_{\mkern -2mu H}$

and

![]() $ T_{\mkern -2mu C}$

, representing the hot and cold boundaries, respectively, while the lateral walls are thermally insulated (adiabatic) (figure 1).

$ T_{\mkern -2mu C}$

, representing the hot and cold boundaries, respectively, while the lateral walls are thermally insulated (adiabatic) (figure 1).

2.2. Lattice Boltzmann method

2.2.1. Methodological overview

The LBM is employed as an efficient alternative to traditional Navier–Stokes–Fourier solvers in the low-Mach regime (Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017; Succi Reference Succi2018). The LBM solves the discrete velocity Boltzmann equation (DVBE)

where

![]() $f_k$

denotes the particle distribution function along discrete velocities

$f_k$

denotes the particle distribution function along discrete velocities

![]() $\boldsymbol{c}_k$

,

$\boldsymbol{c}_k$

,

![]() $\varOmega _k$

is the collision operator and

$\varOmega _k$

is the collision operator and

![]() $F_k$

represents forcing terms. By appropriate choice of velocity discretisation and collision model, the compressible Navier–Stokes and energy equations can be recovered. In this study, two coupled three-dimensional, 19-velocity (D3Q19)-LBMs are used:

$F_k$

represents forcing terms. By appropriate choice of velocity discretisation and collision model, the compressible Navier–Stokes and energy equations can be recovered. In this study, two coupled three-dimensional, 19-velocity (D3Q19)-LBMs are used:

![]() $f_k$

for mass–momentum conservation and

$f_k$

for mass–momentum conservation and

![]() $g_k$

for energy conservation (Guo & Shu Reference Guo and Shu2013). Simulations are implemented within the open-source STLBM framework (Latt, Coreixas & Beny Reference Latt, Coreixas and Beny2021), which provides out-of-the-box GPU acceleration through modern C++ paradigms (Larkin & Stulova Reference Larkin and Stulova2024), thereby greatly reducing the computational time required for the extensive parametric studies conducted in this work.

$g_k$

for energy conservation (Guo & Shu Reference Guo and Shu2013). Simulations are implemented within the open-source STLBM framework (Latt, Coreixas & Beny Reference Latt, Coreixas and Beny2021), which provides out-of-the-box GPU acceleration through modern C++ paradigms (Larkin & Stulova Reference Larkin and Stulova2024), thereby greatly reducing the computational time required for the extensive parametric studies conducted in this work.

In the context of LBMs, the simulation of hydrodynamics with natural convection and conjugate heat transfer in porous media relies on several key features, summarised below, with additional technical details available in Appendix B.

-

(i) Hydrodynamics. The LBM relies on the collide-and-stream scheme

(2.9)which is second-order accurate in space and time (He, Chen & Doolen Reference He, Chen and Doolen1998; Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017). The collision model \begin{equation} f_k(\boldsymbol{r}+\boldsymbol{c}_k\Delta t,t+\Delta t)=\varOmega _k(\boldsymbol{r},t)+F_k(\boldsymbol{r},t), \end{equation}

\begin{equation} f_k(\boldsymbol{r}+\boldsymbol{c}_k\Delta t,t+\Delta t)=\varOmega _k(\boldsymbol{r},t)+F_k(\boldsymbol{r},t), \end{equation}

$\varOmega _k$

is usually approximated by the Bhatnagar–Gross–Krook (BGK) operator (Bhatnagar, Gross & Krook Reference Bhatnagar, Gross and Krook1954; Qian, D’Humières & Lallemand Reference Qian, D’Humières and Lallemand1992)(2.10)which relaxes distributions

$\varOmega _k$

is usually approximated by the Bhatnagar–Gross–Krook (BGK) operator (Bhatnagar, Gross & Krook Reference Bhatnagar, Gross and Krook1954; Qian, D’Humières & Lallemand Reference Qian, D’Humières and Lallemand1992)(2.10)which relaxes distributions \begin{equation} \varOmega _k = -\frac {\Delta t}{\tau } \big (f_k - f_k^{eq}\big ), \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \varOmega _k = -\frac {\Delta t}{\tau } \big (f_k - f_k^{eq}\big ), \end{equation}

$f_k$

toward equilibrium

$f_k$

toward equilibrium

$f_k^{eq}$

with relaxation time

$f_k^{eq}$

with relaxation time

$\tau$

, linked to kinematic viscosity through

$\tau$

, linked to kinematic viscosity through

$\nu =c_s^2(\tau -1/2)\Delta t$

, where

$\nu =c_s^2(\tau -1/2)\Delta t$

, where

$c_s$

is the speed of sound in lattice units. Density and momentum follow from the distribution moments (

$c_s$

is the speed of sound in lattice units. Density and momentum follow from the distribution moments (

$\rho = \sum _k f_k$

and

$\rho = \sum _k f_k$

and

$\rho \boldsymbol{u} = \sum _k f_k\boldsymbol{c}_k$

), while buoyancy is introduced via a forcing scheme (Peng, Shu & Chew Reference Peng, Shu and Chew2003).

$\rho \boldsymbol{u} = \sum _k f_k\boldsymbol{c}_k$

), while buoyancy is introduced via a forcing scheme (Peng, Shu & Chew Reference Peng, Shu and Chew2003).

-

(ii) Improved accuracy for pore-scale simulations. Here, accuracy is enhanced by the two-relaxation-time (TRT) operator (Ginzburg, Verhaeghe & d’Humieres Reference Ginzburg, Verhaeghe and d’Humieres2008), which separates symmetric and antisymmetric modes with relaxation times

$\tau _+$

and

$\tau _+$

and

$\tau _-$

. This operator allows independent control of kinematic viscosity, while an additional parameter

$\tau _-$

. This operator allows independent control of kinematic viscosity, while an additional parameter

$\varLambda _{\textit{TRT}}$

is used to improve the accuracy of LBMs in under-resolved conditions (only a few points per pore) and at low Reynolds numbers (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg2007; Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017). It is commonly set to

$\varLambda _{\textit{TRT}}$

is used to improve the accuracy of LBMs in under-resolved conditions (only a few points per pore) and at low Reynolds numbers (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg2007; Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017). It is commonly set to

$3/16$

following Talon et al. (Reference Talon, Bauer, Gland, Youssef, Auradou and Ginzburg2012).

$3/16$

following Talon et al. (Reference Talon, Bauer, Gland, Youssef, Auradou and Ginzburg2012). -

(iii) Energy and conjugate heat transfer. A second LBM recovers the energy equation using distributions

$g_k$

with BGK collisions (Yue et al. Reference Yue, Chai, Wang and Shi2021). The equilibrium

$g_k$

with BGK collisions (Yue et al. Reference Yue, Chai, Wang and Shi2021). The equilibrium

$g_k^{eq}$

depends on

$g_k^{eq}$

depends on

$\rho c_p T$

, velocity

$\rho c_p T$

, velocity

$\boldsymbol{u}$

and an adjustable parameter

$\boldsymbol{u}$

and an adjustable parameter

$A$

for stability. Thermal conductivity in each phase (

$A$

for stability. Thermal conductivity in each phase (

$f$

:fluid,

$f$

:fluid,

$s$

:solid) is related to the relaxation time via(2.11)while the temperature field is obtained from the zeroth moment,

$s$

:solid) is related to the relaxation time via(2.11)while the temperature field is obtained from the zeroth moment, \begin{equation} \kappa _{f,s} = A c_s^2 \!\left (\tau _{f,s}-\frac {1}{2}\right )\!\Delta t, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \kappa _{f,s} = A c_s^2 \!\left (\tau _{f,s}-\frac {1}{2}\right )\!\Delta t, \end{equation}

$\rho c_p T = \sum _k g_k$

. This enables direct treatment of conjugate heat transfer with distinct

$\rho c_p T = \sum _k g_k$

. This enables direct treatment of conjugate heat transfer with distinct

$(\rho c_p)$

and

$(\rho c_p)$

and

$\kappa$

in the fluid and solid domains.

$\kappa$

in the fluid and solid domains.

-

(iv) Boundary and initial conditions. Boundaries are treated with link-wise schemes. No-slip adiabatic walls are imposed with bounce back (Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017), while Dirichlet conditions for prescribed temperatures are enforced via an anti-bounce-back scheme (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Shi, Guo, Chai and Lu2012). Distribution functions are initialised at equilibrium, which allows one to easily impose any macroscopic field (e.g. velocity, density or temperature) consistently with the physical phenomena of interest.

Before presenting our main results, we benchmark the numerical approach against two canonical problems: the onset of RBC (Shan Reference Shan1997) and conjugate heat transfer in a square cavity with 16 blocks (Merrikh & Lage Reference Merrikh and Lage2005; Raji et al. Reference Raji, Hasnaoui, Naïmi, Slimani and Ouazzani2012; Karani & Huber Reference Karani and Huber2015; Lu, Lei & Dai Reference Lu, Lei and Dai2017; Landl et al. Reference Landl, Prieler, Monaco and Hochenauer2023). These validations set the stage for § 3, where we analyse hydrodynamic flow and steady conduction, establish a baseline for inertial effects and subsequently investigate the transition to oscillatory HRLC.

2.2.2. Model benchmark

Our model is first benchmarked against the onset of pure-fluid RBC, following the procedure of Shan (Reference Shan1997). Convection was observed at a critical Rayleigh number of

![]() $\textit {Ra}_{cr} = 1711.2$

with a corresponding critical wavenumber

$\textit {Ra}_{cr} = 1711.2$

with a corresponding critical wavenumber

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu c} = 3.117$

in the

$k_{\mkern -2mu c} = 3.117$

in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane, determined by measuring the exponential growth rate of the vertical velocity at the onset of convection. These values were obtained for a fluid relaxation time of

$y$

plane, determined by measuring the exponential growth rate of the vertical velocity at the onset of convection. These values were obtained for a fluid relaxation time of

![]() $\tau ^+ = 0.6$

on a mesh of

$\tau ^+ = 0.6$

on a mesh of

![]() $N_x \times N_z = 202 \times 101$

, using bounce-back boundary conditions at the top and bottom and periodic boundary conditions elsewhere. This result exhibits a 0.2 % relative deviation from the reference value of 1707.8, derived from linear stability analysis and confirmed by experimental observations (Shan Reference Shan1997).

$N_x \times N_z = 202 \times 101$

, using bounce-back boundary conditions at the top and bottom and periodic boundary conditions elsewhere. This result exhibits a 0.2 % relative deviation from the reference value of 1707.8, derived from linear stability analysis and confirmed by experimental observations (Shan Reference Shan1997).

The implemented LBM model is further validated against conjugate heat transfer in porous media, following the benchmark used in previous studies (Merrikh & Lage Reference Merrikh and Lage2005; Raji et al. Reference Raji, Hasnaoui, Naïmi, Slimani and Ouazzani2012; Karani & Huber Reference Karani and Huber2015; Lu et al. Reference Lu, Lei and Dai2017, Reference Lu, Lei and Dai2018; Landl et al. Reference Landl, Prieler, Monaco and Hochenauer2023). The benchmark is conducted in a two-dimensional porous medium of size

![]() $H \times H$

consisting of a regular array of 16 square blocks (each 60

$H \times H$

consisting of a regular array of 16 square blocks (each 60

![]() $\times$

60 lattice nodes), which yields a porosity of

$\times$

60 lattice nodes), which yields a porosity of

![]() $ \varphi = 64\,\%$

, as shown in figure 1(b). While

$ \varphi = 64\,\%$

, as shown in figure 1(b). While

![]() $Ra_{\mkern -2mu f} = 10^5$

and

$Ra_{\mkern -2mu f} = 10^5$

and

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

is kept constant in the benchmark, the solid-to-fluid thermal conductivity ratio (

$k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

is kept constant in the benchmark, the solid-to-fluid thermal conductivity ratio (

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu r} = k_{\mkern -2mu s}/k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) is varied between

$k_{\mkern -2mu r} = k_{\mkern -2mu s}/k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

) is varied between

![]() $0.1$

and

$0.1$

and

![]() $100$

to analyse its influence on heat transfer. The Nusselt number for the benchmark problem is calculated as described in (Merrikh & Lage Reference Merrikh and Lage2005)

$100$

to analyse its influence on heat transfer. The Nusselt number for the benchmark problem is calculated as described in (Merrikh & Lage Reference Merrikh and Lage2005)

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \textit{Nu} &= \frac {h_{\text{av}} H}{k_{\mkern -2mu f}} = \left ( \frac {H}{T_{\mkern -2mu H} - T_{\mkern -2mu C}} \right ) \left [ \frac {1}{H} \int _{0}^{H}\! \left . - \frac {\partial T}{\partial x} \right |_{x=0} {\rm d}y \right ] \\ &= - \int _{0}^{1}\! \left . \frac {\partial \theta }{\partial \xi } \right |_{\xi =0} {\rm d}\eta , \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \textit{Nu} &= \frac {h_{\text{av}} H}{k_{\mkern -2mu f}} = \left ( \frac {H}{T_{\mkern -2mu H} - T_{\mkern -2mu C}} \right ) \left [ \frac {1}{H} \int _{0}^{H}\! \left . - \frac {\partial T}{\partial x} \right |_{x=0} {\rm d}y \right ] \\ &= - \int _{0}^{1}\! \left . \frac {\partial \theta }{\partial \xi } \right |_{\xi =0} {\rm d}\eta , \end{aligned} \end{equation}

where

![]() $h_{{av}}$

is the average heat transfer coefficient,

$h_{{av}}$

is the average heat transfer coefficient,

![]() $\xi =x/H$

is the dimensionless streamwise coordinate and

$\xi =x/H$

is the dimensionless streamwise coordinate and

![]() $\eta =y/H$

is the dimensionless vertical coordinate.

$\eta =y/H$

is the dimensionless vertical coordinate.

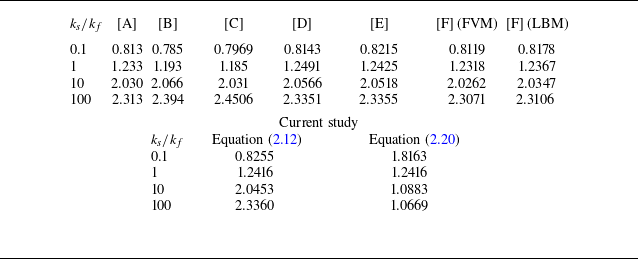

Table 1 presents the benchmark results, showing quantitative agreement between our LBM model and previous studies based on either LBM and finite volume (FVM) simulations.

Table 1. Predictions for

![]() $\textit{Nu}$

along the hot wall for various solid-to-fluid thermal conductivity ratios. The top section presents results from previous studies, while the bottom section includes results from the present study, calculated with (2.12) and (2.20). References: [A] Merrikh & Lage (Reference Merrikh and Lage2005), [B] Raji et al. (Reference Raji, Hasnaoui, Naïmi, Slimani and Ouazzani2012), [C] Karani & Huber (Reference Karani and Huber2015), [D] Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Lei and Dai2017), [E] Lu, Lei & Dai (Reference Lu, Lei and Dai2018), [F] Landl et al. (Reference Landl, Prieler, Monaco and Hochenauer2023).

$\textit{Nu}$

along the hot wall for various solid-to-fluid thermal conductivity ratios. The top section presents results from previous studies, while the bottom section includes results from the present study, calculated with (2.12) and (2.20). References: [A] Merrikh & Lage (Reference Merrikh and Lage2005), [B] Raji et al. (Reference Raji, Hasnaoui, Naïmi, Slimani and Ouazzani2012), [C] Karani & Huber (Reference Karani and Huber2015), [D] Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Lei and Dai2017), [E] Lu, Lei & Dai (Reference Lu, Lei and Dai2018), [F] Landl et al. (Reference Landl, Prieler, Monaco and Hochenauer2023).

However, we argue that this calculation (using (2.12)) of the Nusselt number is not adequate. This method neglects heterogeneity in steady-state heat conduction and produces unphysical values below unity (noting that

![]() $ \textit{Nu} \geqslant 1$

by definition), along with an inverted trend in Nusselt number versus

$ \textit{Nu} \geqslant 1$

by definition), along with an inverted trend in Nusselt number versus

![]() $ k_r$

. For the interested reader, we share further discussion and illustrative benchmarks on this issue in the supplementary material, § 8.

$ k_r$

. For the interested reader, we share further discussion and illustrative benchmarks on this issue in the supplementary material, § 8.

2.3. Porous model, numerical diagnosis and dynamical regime

The porous model used in this study is at the transition between pore scale and continuum scale (Appendix C4). In this study, the domain-to-pore unit ratio is fixed at

![]() $ H/h = 9$

, while the cylinder spacing

$ H/h = 9$

, while the cylinder spacing

![]() $ L$

is varied to control the porosity, which ranges from 32.55 % to 43.44 % (figure 1

a). In order to ensure that the resulting scaling laws are not affected by grid resolution, we conducted additional simulations at twice the standard resolution for the lowest-porosity case in the inertial regime (figures 6 and 15). The baseline resolution corresponds to 30 lattice nodes per cylinder radius.

$ L$

is varied to control the porosity, which ranges from 32.55 % to 43.44 % (figure 1

a). In order to ensure that the resulting scaling laws are not affected by grid resolution, we conducted additional simulations at twice the standard resolution for the lowest-porosity case in the inertial regime (figures 6 and 15). The baseline resolution corresponds to 30 lattice nodes per cylinder radius.

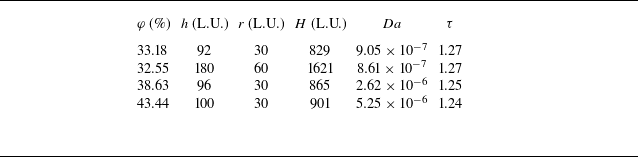

Table 2. Tabulated values for the simulation domains used (see figure 1

a). Here, L.U. stands for lattice units (metre equivalent). The table presents porosity (

![]() $\varphi$

), unit pore scale (

$\varphi$

), unit pore scale (

![]() $h$

), cylinder radius (

$h$

), cylinder radius (

![]() $r = D/2$

), domain height/width (

$r = D/2$

), domain height/width (

![]() $H$

), Darcy number (

$H$

), Darcy number (

![]() $Da$

) and tortuosity (

$Da$

) and tortuosity (

![]() $\tau$

).

$\tau$

).

To isolate the role of inertia, we first perform purely hydrodynamic simulations by imposing a pressure gradient,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}P$

, across the system volume,

$\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}P$

, across the system volume,

![]() $V$

, and measure the resulting effective discharge velocity in the forcing direction,

$V$

, and measure the resulting effective discharge velocity in the forcing direction,

![]() $U_{\mkern -2mu i}$

, using the Dupuit–Forchheimer relationship (Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017)

$U_{\mkern -2mu i}$

, using the Dupuit–Forchheimer relationship (Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017)

For simplicity, we omit the subscript and denote

![]() $U_{\mkern -2mu i}$

simply as

$U_{\mkern -2mu i}$

simply as

![]() $U$

. These measurements are performed using the hydrodynamic LBM model described in § 2.2 with

$U$

. These measurements are performed using the hydrodynamic LBM model described in § 2.2 with

![]() $\tau ^+ = 0.505$

and periodic boundary conditions in all directions of the porous models depicted in figure 1(a).

$\tau ^+ = 0.505$

and periodic boundary conditions in all directions of the porous models depicted in figure 1(a).

In the Darcy regime, the discharge velocity is linearly proportional to the pressure gradient

where

![]() $ \mu$

(ML

$ \mu$

(ML

![]() $^{-1}$

T

$^{-1}$

T

![]() $^{-1}$

) denotes the fluid dynamic viscosity.

$^{-1}$

) denotes the fluid dynamic viscosity.

As the flow rate increases, the relationship between effective discharge and pressure gradient becomes progressively nonlinear while still steady, and eventually transitions to an unsteady regime characterised by vortex shedding within the porous matrix (Khalifa et al. Reference Khalifa, Pocher and Tilton2020), referred to as the Hopf bifurcation (Agnaou, Lasseux & Ahmadi Reference Agnaou, Lasseux and Ahmadi2016).

The Forchheimer regime emerges as inertial effects become significant, introducing nonlinear pressure–velocity scaling. These deviations are captured by extending Darcy’s law with a quadratic correction term

where

![]() $ K_{\mkern -2mu F}$

(L

$ K_{\mkern -2mu F}$

(L

![]() $^2$

) denotes the effective Forchheimer permeability. Experimental results by Dukhan, Bağcı & Özdemir (Reference Dukhan, Bağcı and Özdemir2014) suggest that

$^2$

) denotes the effective Forchheimer permeability. Experimental results by Dukhan, Bağcı & Özdemir (Reference Dukhan, Bağcı and Özdemir2014) suggest that

![]() $ K_{\mkern -2mu F}$

differs from the intrinsic permeability

$ K_{\mkern -2mu F}$

differs from the intrinsic permeability

![]() $K$

, with a deviation quantified by the permeability ratio

$K$

, with a deviation quantified by the permeability ratio

![]() $ \sigma _{\mkern -2mu F} = K_{\mkern -2mu F} / K$

.

$ \sigma _{\mkern -2mu F} = K_{\mkern -2mu F} / K$

.

To facilitate comparison across porous configurations and flow intensities, the pressure–velocity relationships are recast in dimensionless form using the normalised pressure gradient (Fand et al. Reference Fand, Kim, Lam and Phan1987; Khalifa et al. Reference Khalifa, Pocher and Tilton2020)

which expresses the actual pressure gradient relative to the Darcy prediction. The corresponding scaling laws for the different flow regimes are

\begin{equation} \left \{ \begin{array}{lll} G = 1 & \quad \text{(Darcy regime),} \\[6pt] G = \frac {1}{\sigma _{\mkern -2mu F}} + \frac {c_{\mkern -2mu F}}{\sqrt {\sigma _{\mkern -2mu F}}} \textit{Re} & \quad \text{(Forchheimer regime),} \\[6pt] G = q + r \textit{Re} & \quad \text{(Vortex-shedding regime).} \end{array} \right . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left \{ \begin{array}{lll} G = 1 & \quad \text{(Darcy regime),} \\[6pt] G = \frac {1}{\sigma _{\mkern -2mu F}} + \frac {c_{\mkern -2mu F}}{\sqrt {\sigma _{\mkern -2mu F}}} \textit{Re} & \quad \text{(Forchheimer regime),} \\[6pt] G = q + r \textit{Re} & \quad \text{(Vortex-shedding regime).} \end{array} \right . \end{equation}

In these expressions,

![]() $ \sigma _{\mkern -2mu F}$

and

$ \sigma _{\mkern -2mu F}$

and

![]() $ c_{\mkern -2mu F}$

represent the linear and quadratic resistance contributions in the Forchheimer regime, while

$ c_{\mkern -2mu F}$

represent the linear and quadratic resistance contributions in the Forchheimer regime, while

![]() $ q$

and

$ q$

and

![]() $ r$

serve as analogous coefficients in the vortex-shedding regime. The Reynolds number is defined as

$ r$

serve as analogous coefficients in the vortex-shedding regime. The Reynolds number is defined as

![]() $ \textit{Re} = U \sqrt {K} / \nu$

, where

$ \textit{Re} = U \sqrt {K} / \nu$

, where

![]() $ \sqrt {K}$

acts as a characteristic length scale (Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017).

$ \sqrt {K}$

acts as a characteristic length scale (Nield & Bejan Reference Nield and Bejan2017).

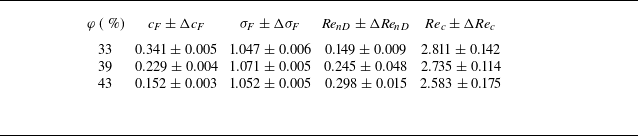

To quantify the transition to non-Darcy behaviour, we define the non-Darcy Reynolds number,

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD}$

, as the point where the pressure gradient exceeds the Darcy prediction by 1 %. Although this criterion may appear arbitrary, intersecting fitted Darcy, transitional and Forchheimer regimes also requires selection of a cutoff for the included data points, which is equally subjective. Nevertheless, this criterion yields results consistent with those obtained by such intersection methods, as shown by Khalifa et al. (Reference Khalifa, Pocher and Tilton2020). The associated uncertainty,

$ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD}$

, as the point where the pressure gradient exceeds the Darcy prediction by 1 %. Although this criterion may appear arbitrary, intersecting fitted Darcy, transitional and Forchheimer regimes also requires selection of a cutoff for the included data points, which is equally subjective. Nevertheless, this criterion yields results consistent with those obtained by such intersection methods, as shown by Khalifa et al. (Reference Khalifa, Pocher and Tilton2020). The associated uncertainty,

![]() $ \Delta \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD}$

, is defined by the spacing to the next lower Reynolds number in the dataset.

$ \Delta \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD}$

, is defined by the spacing to the next lower Reynolds number in the dataset.

The onset of the vortex-shedding regime is identified as the first occurrence of unsteady flow, defining the critical Reynolds number

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}$

. Its uncertainty,

$ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}$

. Its uncertainty,

![]() $ \Delta \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}$

, corresponds to the interval between the last steady and the first unsteady data point.

$ \Delta \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}$

, corresponds to the interval between the last steady and the first unsteady data point.

The Forchheimer regime is characterised by fitting the normalised pressure gradient

![]() $ G$

over the steady-state interval

$ G$

over the steady-state interval

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD} \leqslant \textit{Re} \leqslant \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}$

, where the parameters

$ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD} \leqslant \textit{Re} \leqslant \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}$

, where the parameters

![]() $ \sigma _{\mkern -2mu F}$

and

$ \sigma _{\mkern -2mu F}$

and

![]() $ c_{\mkern -2mu F}$

are obtained with a regression confidence of

$ c_{\mkern -2mu F}$

are obtained with a regression confidence of

![]() $ R^2 \gt 0.99$

.

$ R^2 \gt 0.99$

.

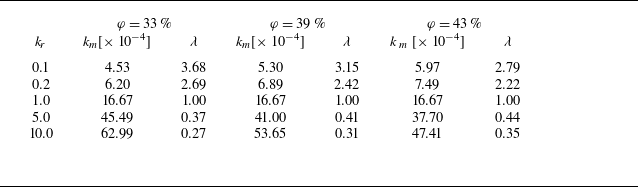

Having established the hydrodynamic behaviour, we now turn to heat transfer in HRLC. As shown in § 2.2.2, the accurate evaluation of

![]() $ \textit{Nu}$

relies on the proper determination of the effective thermal conductivity of the porous medium. The effective thermal conductivity

$ \textit{Nu}$

relies on the proper determination of the effective thermal conductivity of the porous medium. The effective thermal conductivity

![]() $ k_{\mkern -2mu m}$

is determined prior to each HRLC simulation by running a conduction-only case below the onset of convection (

$ k_{\mkern -2mu m}$

is determined prior to each HRLC simulation by running a conduction-only case below the onset of convection (

![]() $ Ra_{\mkern -2mu f} = 1$

), using the same parameters as in the main simulation (see table 5 in Appendix A for the comprehensive list of symbols used throughout this study).

$ Ra_{\mkern -2mu f} = 1$

), using the same parameters as in the main simulation (see table 5 in Appendix A for the comprehensive list of symbols used throughout this study).

We start the simulations with a linear temperature profile along the gravitational direction and wait until the vertical heat flux remains constant within

![]() $10^{-7}$

over a time window of

$10^{-7}$

over a time window of

![]() $ t = 0.01\, H^2 / \alpha _{\mkern -2mu f}$

. The conductive heat flux

$ t = 0.01\, H^2 / \alpha _{\mkern -2mu f}$

. The conductive heat flux

![]() $ q_{\textit{cond}}$

is computed as

$ q_{\textit{cond}}$

is computed as

where

![]() $ k(x)$

is the local thermal conductivity, either of the fluid or of the solid, and

$ k(x)$

is the local thermal conductivity, either of the fluid or of the solid, and

![]() $ {{\rm d}T}/{{\rm d}z}\big |_{\mkern -2mu z=0}$

denotes the temperature gradient at the bottom wall. The effective medium thermal conductivity is obtained using Fourier’s law as

$ {{\rm d}T}/{{\rm d}z}\big |_{\mkern -2mu z=0}$

denotes the temperature gradient at the bottom wall. The effective medium thermal conductivity is obtained using Fourier’s law as

As mentioned in the previous section, the definition of the Nusselt number proposed in previous publication may take non-physical values less than unity. Throughout the rest of this study, we adopt a definition similar to Karani & Huber (Reference Karani and Huber2017)

\begin{equation} \textit{Nu} = 1 + \frac {\frac {1}{V} \int _V u_{\mkern -2mu i} \ T \, {\rm d}V }{\alpha _{\mkern -2mu m} \, \frac {\Delta T}{H}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \textit{Nu} = 1 + \frac {\frac {1}{V} \int _V u_{\mkern -2mu i} \ T \, {\rm d}V }{\alpha _{\mkern -2mu m} \, \frac {\Delta T}{H}}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $ u_{\mkern -2mu i}$

denotes the local fluid velocity component aligned with the macroscopic temperature gradient.

$ u_{\mkern -2mu i}$

denotes the local fluid velocity component aligned with the macroscopic temperature gradient.

Following Nield & Bejan (Reference Nield and Bejan2017), we define the Reynolds number in the context of convection as

where

![]() $ U$

is the discharge velocity in the direction of the macroscopic temperature gradient, as introduced earlier. The absolute value reflects that inertial effects depend on the magnitude of the flow, regardless of its direction, while

$ U$

is the discharge velocity in the direction of the macroscopic temperature gradient, as introduced earlier. The absolute value reflects that inertial effects depend on the magnitude of the flow, regardless of its direction, while

![]() $ \sqrt {K}$

serves as the characteristic pore-scale length.

$ \sqrt {K}$

serves as the characteristic pore-scale length.

3. Inertial effects in HRLC at fixed porosity and conductivity ratio

3.1. Transition from Darcy to non-Darcy flow in hydrodynamics

Before analysing the role of inertia in HRLC, we first examine isothermal hydrodynamic flow driven by a pressure gradient at a fixed porosity of

![]() $ \varphi = 43\,\%$

. To characterise the distinct flow regimes, we evaluate the relationship between the normalised pressure gradient

$ \varphi = 43\,\%$

. To characterise the distinct flow regimes, we evaluate the relationship between the normalised pressure gradient

![]() $ G$

(2.16) and the permeability-based Reynolds number, spatially averaged over the fluid domain,

$ G$

(2.16) and the permeability-based Reynolds number, spatially averaged over the fluid domain,

![]() $ \langle \textit{Re} \rangle _H$

.

$ \langle \textit{Re} \rangle _H$

.

Figure 2. (a) Pore-scale streamlines illustrating: (i) laminar (Darcy) flow; (ii) steady inertia-dominated flow (Forchheimer regime); and (iii) unsteady flow with vortex shedding (snapshot in time). (b) Log–log plot of the normalised pressure gradient

![]() $ G$

versus the domain-averaged permeability-based Reynolds number

$ G$

versus the domain-averaged permeability-based Reynolds number

![]() $ \langle \textit{Re} \rangle _H$

. Transitions between regimes are indicated by vertical dashed lines, denoting the onset of non-Darcy flow (

$ \langle \textit{Re} \rangle _H$

. Transitions between regimes are indicated by vertical dashed lines, denoting the onset of non-Darcy flow (

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD}$

) and the onset of vortex shedding (

$ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD}$

) and the onset of vortex shedding (

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}$

).

$ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}$

).

Figure 2(b) compares the simulation results (square symbols) with the regime-specific scaling laws (solid lines) introduced in (2.17).

Following the procedure outlined in § 2.3, we identify the regime transitions for

![]() $ \varphi = 43\,\%$

at

$ \varphi = 43\,\%$

at

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD} \approx 0.3$

and

$ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD} \approx 0.3$

and

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c} \approx 2.6$

. The fitted parameters are

$ \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c} \approx 2.6$

. The fitted parameters are

The Darcy regime corresponds to the inertialess limit, while the Forchheimer regime reflects a finite-Reynolds-number correction to Darcy’s law. As proposed by Khalifa et al. (Reference Khalifa, Pocher and Tilton2020), the initial inertial deviations from the laminar regime may follow the quadratic scaling

![]() $ G = \sigma ^{-1} + \gamma \textit{Re}^2$

, which they designate as the transitional regime. Given the limited validity of this scaling, we interpret the interval

$ G = \sigma ^{-1} + \gamma \textit{Re}^2$

, which they designate as the transitional regime. Given the limited validity of this scaling, we interpret the interval

![]() $ [\textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD}, \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}]$

as a transitional range between Darcy and vortex-shedding flow, and refer to the steady inertial dynamics in this range as Forchheimer-type behaviour.

$ [\textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu nD}, \textit{Re}_{\mkern -2mu c}]$

as a transitional range between Darcy and vortex-shedding flow, and refer to the steady inertial dynamics in this range as Forchheimer-type behaviour.

3.2.

Thermal convection in a homogeneous porous medium (

$k_{\mkern -2mu s}=k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

)

$k_{\mkern -2mu s}=k_{\mkern -2mu f}$

)

This section presents the HRLC results for a porous medium of a moderate porosity

![]() $ \varphi = 43\,\%$

(

$ \varphi = 43\,\%$

(

![]() $ Da = 5.25 \times 10^{-6}$

), saturated with a fluid with a thermal conductivity of

$ Da = 5.25 \times 10^{-6}$

), saturated with a fluid with a thermal conductivity of

![]() $k_{\mkern -2mu f}=k_{\mkern -2mu s}$

and

$k_{\mkern -2mu f}=k_{\mkern -2mu s}$

and

![]() $\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}=1$

, representing the base case of uniform thermal conductivity (i.e.

$\textit{Pr}_{\mkern -2mu f}=1$

, representing the base case of uniform thermal conductivity (i.e.

![]() $\lambda =1$

).

$\lambda =1$

).

3.2.1. From steady to oscillatory convection

Figure 3. Snapshots of the normalised temperature field

![]() $\theta$

(top), and time-averaged Nusselt number versus Rayleigh-fluid number (bottom), across different flow regimes but for fixed porosity

$\theta$

(top), and time-averaged Nusselt number versus Rayleigh-fluid number (bottom), across different flow regimes but for fixed porosity

![]() $\varphi = 43\,\%$

and Darcy number (

$\varphi = 43\,\%$

and Darcy number (

![]() $Da = 5.25 \times 10^{-6}$

). The horizontal colour map encodes the degree of temporal variability in the heat transport (i.e.

$Da = 5.25 \times 10^{-6}$

). The horizontal colour map encodes the degree of temporal variability in the heat transport (i.e.

![]() $\textit{Nu}(t)$

). Blue regions indicate steady-state convection, while shaded regions represent the uncertainty in the onset of harmonic oscillations. As

$\textit{Nu}(t)$

). Blue regions indicate steady-state convection, while shaded regions represent the uncertainty in the onset of harmonic oscillations. As

![]() $Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}$

increases, multi-frequency oscillatory convection emerges, denoted as vigorous oscillatory convection.

$Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}$

increases, multi-frequency oscillatory convection emerges, denoted as vigorous oscillatory convection.

Figure 3 presents instantaneous thermal fields, shown as non-dimensional temperature

![]() $ \theta =(T-T_{\mkern -2mu C})/(T_{\mkern -2mu H}-T_{\mkern -2mu C})$

, illustrating the transition from steady to quasi-steady states across a range of fluid Rayleigh numbers

$ \theta =(T-T_{\mkern -2mu C})/(T_{\mkern -2mu H}-T_{\mkern -2mu C})$

, illustrating the transition from steady to quasi-steady states across a range of fluid Rayleigh numbers

![]() $ Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}$

, along with the corresponding Nusselt–Rayleigh relationship. The colour coding (steady state, harmonic oscillatory and vigorous oscillatory) qualitatively represents the temporal behaviour of the vertical heat flux (

$ Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}$

, along with the corresponding Nusselt–Rayleigh relationship. The colour coding (steady state, harmonic oscillatory and vigorous oscillatory) qualitatively represents the temporal behaviour of the vertical heat flux (

![]() $ \textit{Nu}$

), while the shaded region illustrates the uncertainty associated with the transition to oscillatory behaviour. At sufficiently low

$ \textit{Nu}$

), while the shaded region illustrates the uncertainty associated with the transition to oscillatory behaviour. At sufficiently low

![]() $ Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}$

, just above the onset of convection, the system exhibits a steady central upwelling flanked by two lateral downwellings, characteristic of a mode-2 convection pattern. The Nusselt number initially follows an approximately linear scaling,

$ Ra_{\mkern -2mu f}$