Introduction

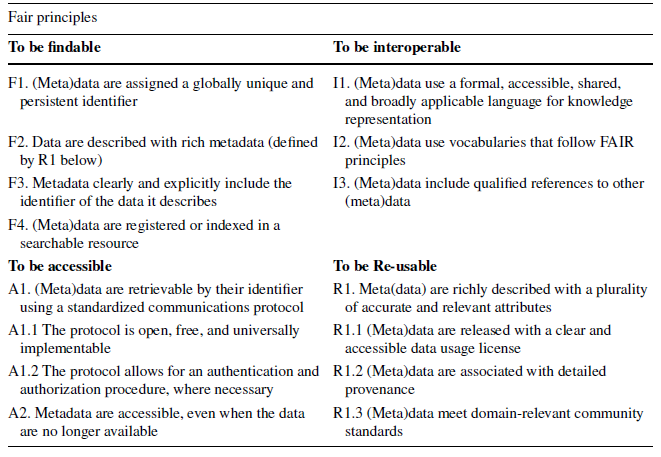

The data and code supporting research projects and related publications are often governed according to various data management policies of employers, funders, professional societies, or journals under the umbrella of reproducible research, open science, or FAIR principles. After the tenth anniversary of the FAIR principles, it behooves us to ask: How can political science research and election studies become more re-useful in these contexts? In 2014, a group of stakeholders with an interest in scholarly data publication came together at a Lorenz Center workshop entitled ‘Jointly Designing a Data Fairport’ in Leiden, Netherlands. Workshop participants discussed approaches to data publication that would render data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR), with particular emphasis on FAIR for machines. The notion emerged that “... through the definition of, and widespread support for, a minimal set of community-agreed guiding principles and practices, all stakeholders could more easily discover, access, appropriately integrate and re-use, and adequately cite, the vast quantities of information being generated by contemporary data-intensive science” (Wilkinson et al. 2016, 3). Funders were already leveraging data management plans to encourage a culture of reproducible research by this time (Smale et al. 2018). So too were corporations and research organizations formalizing the role of the data steward in what had become increasingly data-driven enterprises and projects (Plotkin 2013; Rosenbaum Reference Rosenbaum2010). By 2016, “The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship” were published elaborating on the Lorenz workshop concept through a declaration of the principles accompanied by a succinct explication of data and metadata indicators for each principle. Table 1.

Table 1 XXXX. Wilkinson et al. 2016

The principles and their indicators for machine-actionable data and metadata have since become goalposts for funders and targets for researchers inside and outside the open science community. The principles support reproducible science but are open science agnostic. Indicator A1.2 provides for an authentication and authorization procedure. Data sharing according to the principles can be as “open as possible, as closed as necessary” (Landi et al. Reference Landi, Thompson and Giannuzzi2020, 1). In other words, the principles should have as much utility in for-profit, proprietary drug development as they do in editorial guidelines for open access journals, and the wide range of scholarly communication that falls between.

Challenges and implementation considerations

In the ten intervening years since the Leiden workshop, FAIR implementations have flourished in a multiplicity of disciplines (Jacobsen et al. Reference Jacobsen, de Miranda Azevedo, Juty, Batista, Coles, Cornet and Courtot2020). As evidenced in the 2019 final report and action plan from the European Commission Expert Group on FAIR Data entitled “Turning FAIR into Reality,” governments, along with funding agencies and publishers, have honed their incentives and mandates for scientific data management and stewardship informed by the FAIR Principles (The EU Experts Group on FAIR Data 2019). Through professional organizations such as ECPR, distributed networks of scholars and practitioners have been addressing the best ways for authors to share data and code to enable reviewers and readers to achieve accurate, efficient machine-actionable re-use. For example, at the 2022 general conference of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) in Innsbruck, Austria, panelists convened “Developing an ecosystem of FAIR, Linked, and Open Data in and beyond Political Science” (Basile et al. 2022). Journal editors are similarly adopting protocols and guidelines on research transparency for authors (Mayo-Wilson et al. Reference Mayo-Wilson, Grant, Supplee, Kianersi, Amin, DeHaven and Mellor2021). For example, editors of European Political Science (EPS) presented new guidelines in 2023 for research transparency and open data when publishing in EPS alongside a thoughtful outline of the role and responsibility of journal editors in promoting an open data culture and awareness (Basile et al. Reference Basile, Blair and Buckley2023). This work builds upon and extends earlier initiatives in the discipline, such as the so-called DA-RT statement (Data Access and Research Transparency) and associated policies (Lupia and Elman Reference Lupia and Elman2014). Along the way, documented challenges (Mons et al. 2017) and solutions (Jacobsen et al. Reference Jacobsen, de Miranda Azevedo, Juty, Batista, Coles, Cornet and Courtot2020) for implementing FAIR at the dataset, project, repository, jurisdictional, funder and organizational level. FAIRification challenges may arise from contradictory or non-aligned vocabularies, use of non-persistent identifiers that are not globally unique or machine resolvable, as well as from a lack of agreement within a discipline about how to appropriately label and adopt standard units of measurement. Because of FAIR’s specificity when it comes to use of vocabularies that follow the FAIR principles (Principle I2), the development and implementation of machine readable, authoritative ontologies is an early phase challenge for disciplinarians hitherto inexperienced in use of such tools. Such challenges can largely be overcome through collaborative workshops where scholarly communities refine formal vocabularies, build FAIR implementation profiles, and make decisions about digital infrastructure standards (e.g., ORCIDS, DOIs), as well as through alignment with national and international standards. But, by far the biggest challenge for FAIR convergence can be passive isolationism as described in Jacobson et al. (Reference Jacobsen, de Miranda Azevedo, Juty, Batista, Coles, Cornet and Courtot2020, 27):

Implementation choices made in smaller self-identified communities of practice could eventually be accepted and merged with larger organizations. Using “stick” based compliance incentives (e.g., government health ministries or funding agencies that create FAIR certifications or requirements for funding) could prove a strong driving force towards convergence. However, this process needs to be guided and will not always occur spontaneously; not so much because communities do not want to reach convergence and hence interoperability, but because they are “too busy minding their own business”.

Thankfully, no discipline needs to go it alone when it comes to FAIR. Collaboration across non-proximate fields can serve here as an engine of innovation (Mustillo 2025, 5) Re-use of FAIR implementation profiles for example, can be more than just a nod to a FAIR indicator type, it can pave a way for disciplines to learn from each other and leapfrog ahead.

Ways forward toward FAIR

This section introduces a tripartite people, process, technology (P/P/T) change management framework. Alongside that framework, a practicum portfolio is presented. In 1960, Leavitt argued that for organizational change to be successful, a business must manage and evaluate impacts across four interdependent categories: structure, people, technology and tasks (Leavitt 1965). Leavitt’s four-point diamond model with structure and tasks folded together as “process” informed the golden triangle concept of people, process and technology (P/P/T) that would later be taught in business education and further popularized for technology project management in the 1990’s by Schneier in computer security (2013). The golden triangle strategy emphasizes how planning for, managing, and measuring progress on all three sides of a P/P/T triangle is key in successful technology projects. Taking up this model, GO FAIR Initiative popularized a “Change, Train, Build” golden triangle or three pillars approach for individuals and organizations seeking to reap the benefits of FAIR digital transformation.Footnote 1

Three pillars approach

-

1. GO CHANGE: focusing on priorities, policies and incentives for implementing FAIR; A socio-cultural change involving relevant stakeholders at all levels relevant for the flourishing of Open Science.

-

2. GO TRAIN: coordinating FAIR awareness and skills development training; Training the required data stewards capable of designing and implementing proper data management plans including FAIR data and services.

-

3. GO BUILD: coordinating FAIR technology; Designing and building the technical standards, best practices and infrastructure components needed to implement the FAIR data principles.

The three pillars framework above offers FAIR implementors a P/P/T strategy with a strong lineage in both business and technology for communicating and effecting contemporary digital transformation.

In all three pillars, FAIR Communities of Mutual Support can be difference making. Communities of mutual support and their activities may be global, regional, national, disciplinary, or project-based with groups implementing at various levels of FAIR maturity. Such a “taking up” percolates at different rates within communities and can be characterized by burgeoning awareness and adoption (Mustillo 2025). Enabling FAIR data is an example of an ambitious FAIR change project funded by the Arnold Foundation and convened by the American Geophysical Union (AGU). The project brought together 300 leaders from a coalition of various disciplinary and subdisciplinary groups representing the international Earth and space science community to develop standards to connect researchers, publishers, and data repositories in the Earth and space sciences to enable FAIR data on a large scale (Stall et al. 2017). Among the aims were to help: 1) researchers understand and follow expectations regarding data curation; 2) publishers adopt and implement standard and best practices around data citation; and 3) make data discoverable and accessible, including to the public. In contrast, the physical sciences community in the USA first took up FAIR through a much smaller NSF funded MPS FAIR hackathon, convening about 40 participants from four sub-disciplines: Materials Science, Light Source Research, High Energy Physics and Chemistry alongside FAIR experts from the bioscience and earth observing communities (Hildreth and Meyers 2020). The workshop used the three pillars to frame the agenda through presentations from speakers, demonstrations with mature and immature projects and products, and by introducing participants to hands-on FAIR experiences working with their own disciplinary data. Another approach is to combine forces across institutions leveraging disciplinary and subdisciplinary strengths like the “Data Curation Network: A Cross-Institutional Staffing Model for Curating Research Data” (Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Carlson, Hudson-Vitale, Imker, Kozlowski, Olendorf and Stewart2018) or the International Society of Biocuration (Bateman Reference Bateman2010; Burge et al. 2012). Academic Institutions and Disciplinary societies like these above who invest in social infrastructure for supporting and enabling knowledgeable FAIR data stewards ensure that their researchers will receive support throughout the data lifecycle and especially for curatorial review. When their data are later published in line with the FAIR principles, it is thereby maximized for re-use and social impact. A recent research project by members of the data curation network found that because of curation support, 90% of researchers felt more confident sharing their data (Carlson and Narlock et al. 2023). Community approaches like any one of these could be taken up by political scientists and/or data stewards supporting the field. In the context of the EU, the goals and outputs articulated in “Making Science Happen: A New Ambition for Research Infrastructures in the European Research Area” share a main message for a stronger Europe which emphasizes the necessity to “exploit the potential of Research Infrastructures as major promoters of Open Science providing FAIR (data which meet principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability) and quality certified Open Data” (The StR-ESFRI2 project 2020, 7).

The essays in this symposium, including this one, are positioned to help political scientists similarly advance the FAIRness of their research data and software sharing. The discipline already has a history of commitments to such endeavors, as evidenced by Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR)’s efforts to increase the transparency, findability and reproducibility of political science data. In 2020, Margaret Levenstein, Director ICPSR, spoke about “the importance of machine-readable DMPs (data management plans) and PIDs (persistent identifiers) for enhancing research practices of graduate students and faculty as well as the usefulness for planning repository services'' (Meyers, Ruttenberg and Hudson-Vitale 2020). Technical implementation initiatives are already emerging in political science. A few noteworthy examples at disciplinary and subdisciplinary levels are: ICPSR's Research Data Ecosystem, a National Resource for Reproducible, Robust, and Transparent Social Science Research in the 21st Century (NSF 2022), Party Facts (Döring and Regel Reference Döring and Regel2019), and Monitoring Electoral Democracy (MEDem 2023 & 2018) which is an instance of a new political data infrastructure with FAIR change, train, build aligned P/P/T affordances.

A practicum portfolio for FAIR research

A portfolio of examples from each pillar illustrating ways to begin FAIRifying is offered next to aid disciplinary communities like political science, which can take them up for (re)use in their own contexts. The portfolio includes: The FAIR Data Stewardship Template, a FAIR Events Primer, The Top 10 FAIR Data & Software Things, and two FAIRification Framework options. The portfolio section concludes with an overview of the FAIRification process illustrated by the FAIR Hour Glass, and a brief summation of the benefits inherent in leveraging ontologies, and assessment tools to improve FAIRness. The FAIR Data Stewardship Template (Kirkpatrick et al. 2021) is a planning tool for organizational and institutional change that leads to implementation of FAIR principles for local assets and services. The Template was first developed for use at a 2020 Force11 Scholarly Communication Institute session on “Advancing FAIR Data Stewardship: Fostering Institutional Planning and Service Development” and is shared openly online and licensed CC BY-NC to encourage organizational re-use. The template can be used by disciplinary communities to surface priority needs for workshops in the training pillar, implementations/prototypes in the build pillar, and for digital transformation events in the change pillar.

Workshops and tutorials are a great way to develop an informed community of practice. In their 2019 publication, “FAIR National Election Studies: How Well Are We Doing?” Workshops on Metadata for Machines (M4M)Footnote 2 and FAIR Implementation Profiles (Schultes, Magagna et al. 2020) fill gaps by helping disciplinarians get hands-on FAIR learning experience and benefit from guided FAIR implementation strategies. The Data Management Training Clearinghouse (DMTC)Footnote 3 is a registry for excellent online learning resources focusing on data skills and capacity building for research data management, data stewardship and data education. Before you write a proposal to get funding for a FAIR event, before you develop curriculum, or deliver a workshop, read yourself in. Use the DMTC and web search for recent examples. Consult with funders, colleagues and experts to ascertain what’s a best fit for your disciplinary learners in the moment.

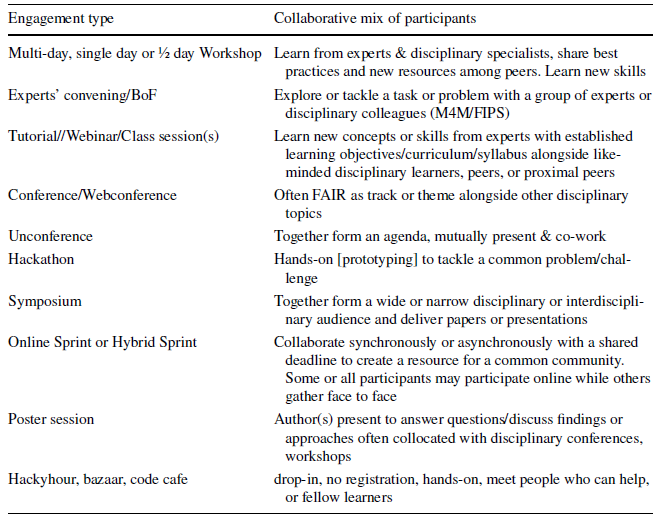

The FAIR Events primer is a lighthearted presentation developed for a GO FAIR Professional Development Workshop audience that gathered in 2020 with an aim of advancing FAIR and GO FAIR in the USA (Meyers 2020). The primer outlines different ways groups can convene to achieve consensus and progress on FAIR maturity. For specific examples of successful engagement strategies for various timeframes, and group sizes, see Table 2.

Table 2 XXXX. (Adapted from Meyers 2020)

The Top 10 FAIR Data & Software Things are brief guides (stand alone, self-paced training materials), called "Things," that can be used by a research community like political science to understand how to make their research (data and software) more FAIR (Martinez et al. 2019). Each [sub]discipline/topic has its own specific list, for example, Top Ten Things Astronomy. (Cruz et al. Reference Cruz, Erdmann, Hettne, Genova, Kenworthy, Meyers, Rol, Santander-Vela and Yeomans2019) Eder & Jedinger in their Reference Eder and Jedinger2019 publication, “FAIR National Election Studies: How Well Are We Doing?” investigate the extent to which eighteen election studies achieve the goals of the FAIR principles by creating checklists for each principle in order to assess the FAIR fitness of large-scale election studies observing the extent to which the FAIR principles “still need to be adapted to derive concrete guidelines for data producers in the field of Election studies” (2019, 653). A way forward would be for political science subdisciplines to hold short hackathons with data curators to develop topically aligned Top Ten FAIR Things lists. Each Thing in these lists would feature explicit references to FAIR principles/indicators, a subdiscipline specific learning segment, and a subdiscipline specific activity segment that allows learners to see example(s) of a FAIR concept in practice and to interact with the concepts to reinforce learning/experience. If the Top Ten Things can be imagined as small sets of recipe cards for FAIR, then FAIRPlus Project’s FAIR Cookbook Footnote 4 is an example of an internet navigable resource offering a dashboard where users can see FAIR ingredients and recipes all in one place.

The FAIR Cookbook is comprehensive and navigable like an e-book (see the left-hand sidebar menu depicted in the Fig. 1 screenshot). The Cookbook features a compilation of “recipes” for FAIR Data Management in the Life Sciences (FAIRPlus b). and offers an excellent search & filter interface allowing users to isolate content by its maturity level, audience, or whether it is hands-on or has executable code.

Fig. 1 FAIR Cookbook (screenshot)-credit FAIRPlus

The Three-point FAIRification Framework, as conceived by the GO FAIR Initiative is one way to get from “recipes” to “implementation” as it brings three stepwise activities together in series to maximize re-use of existing resources, maximize interoperability, and accelerate convergence on standards and technologies supporting FAIR data and services.

-

1. The FAIRification process can start with the previously mentioned Metadata for Machines (M4M) workshops (GO FAIR Initiative a). These workshops bring a community of practice together to consider their domain-relevant metadata requirements and other policy considerations, and formulate these considerations as machine-actionable metadata components.M4M workshops can kick-start disciplinary FAIRification efforts. These are often lightweight, fast-track 1-day events well suited as a pre or post conference workshops.

-

2. The re-usable metadata schemata produced in M4M workshops can speed composition of a community’s FAIR Implementation Profile (FIP) (GO FAIR Initiative b) . When political science researchers ask themselves “Are there one or more communities that we can model our persistent identifier choices and workflows on?”, they can get started by looking at others’ FIPs in the context of a workshop and use community developed tools to facilitate FIP choice making and construction. FIP2DMP is such a mapping resource that interoperates between a FAIR Implementation Profile (FIP) and a Data Management Plan (DMP) template implemented in the Data Stewardship Wizard (Hettne Reference Hettne, Magagna, Gambardella, Suchánek, Schoots and Schultes2023).

-

3. A FAIR Implementation Profile in turn can guide the configuration of FAIR infrastructure. Implementing FAIR Data Points (FDP) (GO FAIR International c) or FAIR Digital Objects (FDO) (GO FAIR International d) are the final steps in the journey to contribute to, and fully participate in, a global Internet of FAIR Data and Services.

The FAIRplus Consortium, an international project with partners from academia and major pharmaceutical companies, similarly has three distinct components in its flexible, multi-level, domain-agnostic FAIRification framework (FAIRplus -b). The FAIRplus framework was developed as practical guidance to improve the FAIRness for both existing and future clinical and molecular datasets (Welter & Juty et al. Reference Welter, Juty, Rocca-Serra, Xu, Henderson, Gu and Strubel2023). The three components are:

-

1. A reusable FAIRification Process, which outlines the main phases of a FAIRification activity

-

2. a FAIRification Template, which breaks down key elements of the process into a series of steps to follow when undertaking a FAIR transformation;

-

3. and a FAIRification Work Plan layout, which provides a structure for organizing FAIR implementation work tailored to the needs of a specific project.

The Three Point FAIRification framework shared by GO FAIR, and the FAIRification framework shared by FAIRplus each offer viable models for communities to incrementally engage in what “going FAIR” means within their projects and disciplines. These frameworks offer academic institutions, disciplinary scholars, and their publishers practical, referenceable ways to step through community implementation decisions on persistent identifiers for scholars and works, metadata standards, and how to leverage ontologies.

Ontologies play a crucial role in FAIR (meta)data. Explicitly, FAIR indicators I1 & I2 (see Table 1) require and depend upon ontologies for FAIR maturity. The use of ontologies can improve interoperability between heterogeneous systems and aid researchers and publishers in defining terms in such a way as to minimize intra and interdisciplinary confusion over term definitions. “Coming to Terms with FAIR Ontologies” opens a discussion about existing, ongoing and required initiatives and instruments to facilitate FAIR ontology sharing on the Web (Poveda-Villalón et al. 2020). There are also online tools, like FOOPS! (Garijo et al. 2021), a web service designed to assess the compliance of vocabularies or ontologies against the FAIR principles. FOOPS! performs a total of 24 different checks and not only detects best practices according to each principle, but also offers an explanation of why a particular principle fails in a tested ontology, offering helpful suggestions to overcome common issues.

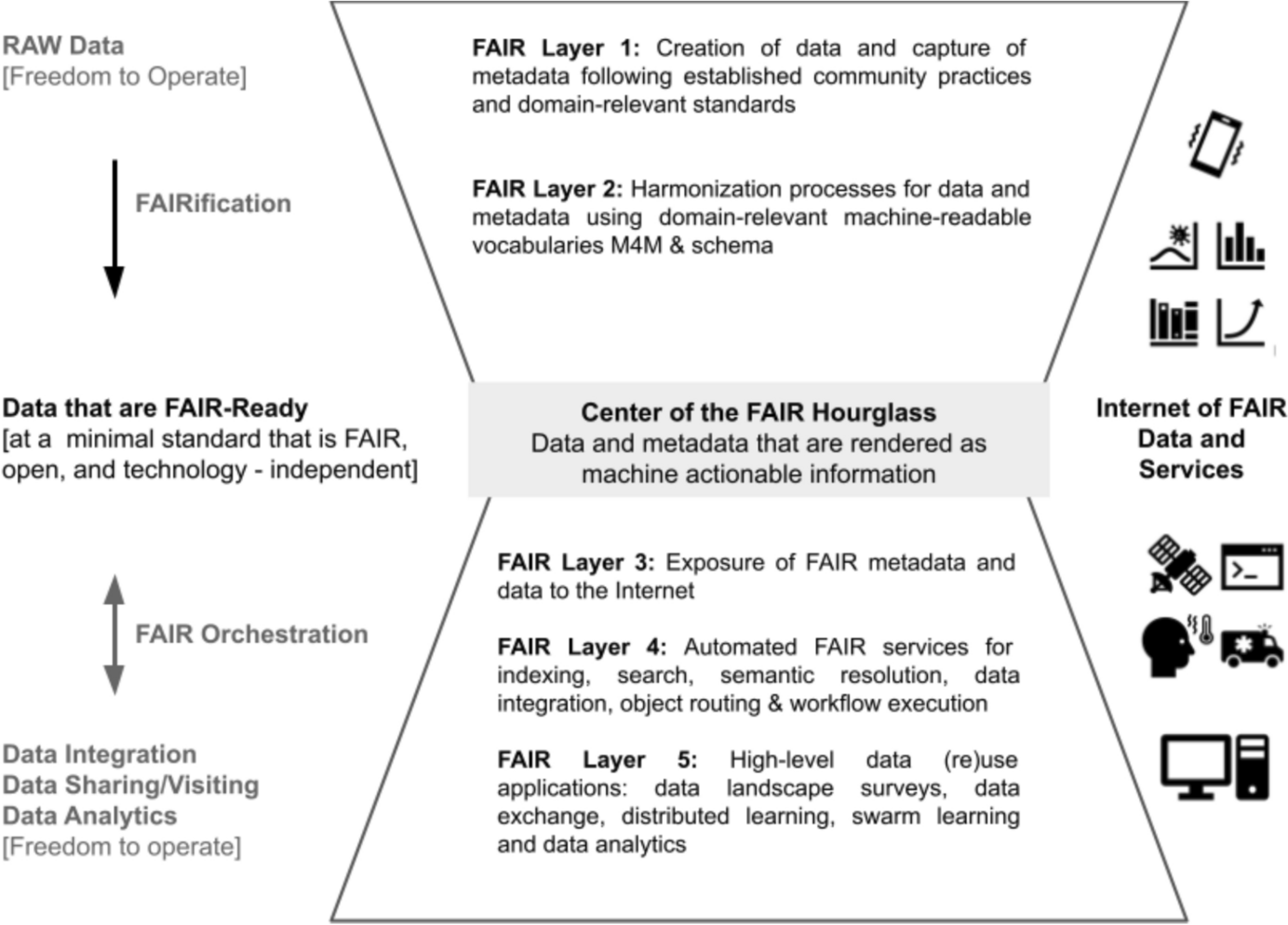

FAIR Assessment checkers can help disciplinary data sharers, their data stewards, and repository managers assess FAIRness of (meta) data. Self-assessment can be done using questionnaire type instruments or checklists (see Eder and Jedinger). FAIR questionnaires can be helpful tools, especially for non-technical stakeholders and/or in the context oxlink:href="_f workshops where not every participant will be a researcher or data provider who has their own data sets to evaluate. However, it is important to emphasize, in the context of FAIR assessment especially, that FAIR is for humans AND machines. Because FAIR (meta) data are meant to be machine actionable, software (e.g., FOOPS!) should be able to perform FAIR tests against shared data. The whitepaper “Community-driven governance of FAIRness assessment: an open issue, an open discussion” aims to “serve as a starting point to foster an open discussion around FAIRness governance and the mechanism(s) that could be used to implement it to be trusted, broadly representative, appropriately scoped, and sustainable” (Wilkinson and Sansone et al. 2022a). Tools like the FAIR Evaluator (Wilkinson and Batista 2023), or the Preservation Quality Tool Project’s PresQT (Wang et al. 2016), or FAIR EVA (Aguilar Gómez & Bernal Reference Aguilar Gómez and Bernal2023) can be used to test the FAIRness of digital objects and improve machine testability/actionability. The initial hackathons of the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) FAIR Metrics and Data Quality Task Force reckoned with the need for “Apples-to-Apples” (A2A1) benchmarks to support evaluation of (meta)data publishing across a multidisciplinary landscape of heterogeneous FAIR implementations (Wilkinson and Sansone et al. 2022b). The above-mentioned FAIR Metrics and Data Quality Task Force’s workshops also describe an accompanying metadata publishing design pattern known as “FAIR Signposting.” It can provide a “transparent, compliant, and straightforward mechanism for guiding automated agents through metadata spaces to locate three essential FAIR elements: the globally unique identifier (GUID), the data records, and the corresponding metadata (Wilkinson and Sansone et al. Reference Wilkinson, Sansone, Grootveld, Dennis, Hecker, Huber and Soiland-Reyes2024). Disciplinary data sharing communities in political science may want to test their preferred data sharing platforms for ease of use with automated FAIRness assessment tools and iteratively test shared (meta) data as it becomes FAIR-ready as illustrated in the FAIR HOURGLASS (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 FAIR Hourglass—derived from Schultes Reference Schultes2023 (CC BY 4.0)

Summarizing FAIR as a minimal standard with affordances.

The FAIR HourGlass concept, illustrated below by Schultes, is a summary of FAIRification benefits that takes its inspiration from the “hourglass” architecture of the Internet. The sustainability, longevity and long-term impact of the internet have been afforded in no small part by the centering of http(s) protocol (small, reliable, free). FAIR (meta)data is similarly advantaged for sustainability and designed to “occupy the center “ like http did for the internet; offering freedom to operate at the wider ends of the hourglass while relying on defined interoperability at its narrow center. The Hourglass diagram further describes how FAIRification progresses overtime by layers, enabling an internet of FAIR data and services.

Schultes clarifies that:

“The FAIR Hourglass is not a particular method of FAIR implementation, but a framework that structures the decisions and activities common to any FAIRification or FAIR Orchestration effort. The overall hourglass shape, and the restricted waist at the center, alludes to a strategy toward FAIR data re-use inspired by the distributed, technical infrastructure composing the Internet. In FAIR data networks however, this infrastructure must be augmented with domain-relevant community standards declared by communities of practice. The FAIR Hourglass is therefore not a purely technical architecture, but a socio-technical framework” (Schultes Reference Schultes2023, 16).

Conclusion

Taken together, the items provided in the above practicum portfolio and the availability of FAIR assessment tools and ontology strategies form a toolkit for overcoming common issues in maturing, governing and publishing FAIR data. Political Science and its many subdisciplines have several fruitful avenues for pursuing paths forward to greater FAIRness. Many academic institutions now offer FAIR informed data curation services and training. Funders and publishers increasingly offer FAIR informed infrastructure. The time may be now to gather and envision: “What might a FAIR Cookbook for Political Science include?” Whether through automated testing of FAIRness for data and code submitted alongside papers, or through initiatives to raise awareness and strengthen data stewardship collaboration, the computability and re-usefulness of political science research will be improved through adoption and implementation of FAIR data stewardship best practices.

Data Availability Statement

No underlying data are available for this article, since no datasets were generated or analyzed during this study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest Statement On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.