1. Introduction

The capability to predict the onset of particle motion is fundamental to numerous natural and industrial processes, ranging from sediment transport in rivers, estuaries and coastal waters to slurry flows in dredging and mining operations (Van Rijn Reference Van Rijn1993; Wierschem et al. Reference Wierschem, Groh, Rehberg, Aksel and Krülle2008). Identifying the threshold conditions for the transport of pollutants, such as microplastics (1 μm−5 mm), in environmental settings also requires a deep understanding of particle dynamics, which, for slightly buoyant particles, are particularly sensitive to hydrodynamic forces (Kane et al. Reference Kane, Clare, Miramontes, Wogelius, Rothwell, Garreau and Pohl2020). Therefore, a detailed examination of the early stages of particle motion is necessary (Nielsen Reference Nielsen1992; Buffington & Montgomery Reference Buffington and Montgomery1997; Vowinckel et al. Reference Vowinckel, Jain, Kempe and Fröhlich2016; Eyal et al. Reference Eyal, Enzel, Meiburg, Vowinckel and Lensky2021). The motion threshold has been extensively studied, driven by applications in civil and coastal engineering (Wilcock Reference Wilcock1993; Agudo & Wierschem Reference Agudo and Wierschem2012; Petit et al. Reference Petit, Houbrechts, Peeters, Hallot, Van Campenhout and Denis2015).

The criterion introduced by Shields (Reference Shields1936) is often used to determine the conditions of incipient sediment transport. According to Shields’ criterion, the motion of a sediment layer exposed to steady flow begins once the hydrodynamic force acting tangentially to the bottom surface exceeds the frictional resistance between the mobile layer and the underlying substrate, which is proportional to the layer’s submerged weight (see figure 1 a). This balance leads to the definition of the Shields parameter, given by the ratio between tangential and vertical forces. At the threshold of incipient motion, this parameter equals the sediment friction coefficient. The critical value of the Shields parameter depends solely on the granular Reynolds number, which quantifies the relative contributions of inertial and viscous forces at the sediment grain scale. By definition, the Shields parameter is inherently a statistical measure due to the randomness of the bottom geometry, as well as flow–particle and particle–particle interactions. In practice, the threshold is typically determined empirically for an ensemble of grains on a rough bed, with critical values accompanied by subjective definitions of different stages of motion (Breusers & Schukking Reference Breusers and Schukking1971).

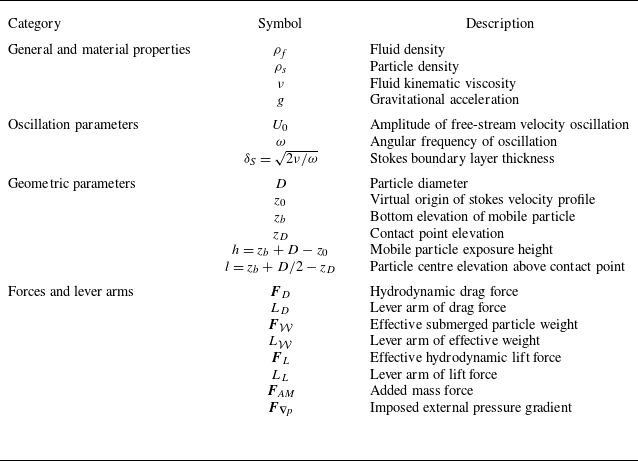

Figure 1. (a) Side view of a hypothetical uniform layer of mobile spheres lying on a regular substrate, i.e. the Shields approach. (b) Top view and (c) side view of the present particle arrangement, where grey spherical particles form a fixed substrate, and the red sphere represents the mobile particle. The blue curve illustrates the Stokes velocity profile. Red arrows indicate the hydrodynamic drag, lift and effective weight forces (added mass and imposed pressure gradient forces are not shown in this sketch). The corresponding lever arms are shown as black double-headed arrows, referenced to the downstream-side contact points (which coincide in this side view). The symbols are categorised and described in table 1.

Recently, there has been a growing emphasis on developing more precise criteria for the motion threshold of a single particle and characterising particle dynamics immediately following the motion onset. These efforts have primarily involved combinations of detailed experiments (Charru et al. Reference Charru, Larrieu, Dupont and Zenit2007; Agudo & Wierschem Reference Agudo and Wierschem2012) and analytical methods (Agudo et al. Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017; Topic et al. Reference Topic, Retzepoglu, Wensing, Illigmann, Luzi, Agudo and Wierschem2019). Unlike the statistical nature of the Shields criterion, these approaches provide well-defined thresholds for the motion of individual spherical particles, directly linking them to specific flow conditions, material properties, local bed structure and the influence of other surrounding particles (Agudo et al. Reference Agudo, Dasilva and Wierschem2014, Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017).

It should be stressed that the previously mentioned studies focus exclusively on unidirectional steady flows. However, the insights gained from these studies have only limited applicability in settings with transient ambient flows. Oscillatory flows, in particular, are critical in many engineering and environmental settings, such as in the periodic agitation of submerged particles in multiphase mixtures or the back-and-forth motion near sediment bedforms induced by coastal waves (Sleath Reference Sleath1984; Nielsen Reference Nielsen1992). Oscillatory flows are well known to be more complex than unidirectional flows, even under laminar conditions. Nonlinear residual flows, such as steady streaming flows, can significantly affect particle dynamics on small and (very) large time scales compared with the period of oscillation (van Overveld et al. Reference van Overveld, Shajahan, Breugem, Clercx and Duran-Matute2022b ). The complex particle–fluid interactions can lead to self-organisation into a wide range of patterns, including chains and bands in diluted systems (van Overveld, Clercx & Duran-Matute Reference van Overveld, Clercx and Duran-Matute2023) or vortex ripples in dense systems (Sleath Reference Sleath1984). Despite their importance, oscillatory flows have received far less attention than unidirectional flows. To our knowledge, a similarly rigorous analytical approach for oscillatory flows has yet to be developed to determine the conditions at the onset of particle motion.

Overall, the unique description of the physics in an oscillatory flow needs one additional dimensionless parameter compared with the unidirectional case, since the system has an additional degree of freedom. This is analogous to general particle motion in oscillatory flows (Klotsa et al. Reference Klotsa, Swift, Bowley and King2007; van Overveld et al. Reference van Overveld, Breugem, Clercx and Duran-Matute2022a ,Reference van Overveld, Shajahan, Breugem, Clercx and Duran-Matute b ). Consequently, reported values for the Shields criterion (or its single-particle equivalent described by Agudo et al. Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017) will depend not only on the granular Reynolds number, but also on an additional dimensionless parameter related to the oscillatory flow component, such as the frequency-dependent viscous length scale relative to the exposed particle’s diameter (Klotsa et al. Reference Klotsa, Swift, Bowley and King2007; Mazzuoli et al. Reference Mazzuoli, Kidanemariam, Blondeaux, Vittori and Uhlmann2016; van Overveld et al. Reference van Overveld, Shajahan, Breugem, Clercx and Duran-Matute2022b , Reference van Overveld, Clercx and Duran-Matute2023).

Due to the larger parameter space, the dynamics of particle motion in oscillatory flows may differ significantly from those in unidirectional flows. In the latter, once a particle starts moving, it is slightly lifted from its pocket in the bed, exposing a larger surface area to the ambient flow and increasing the drag force induced by the ambient flow, accelerating the particle even further. This feedback mechanism produces a sharp transition between stationary and dynamic states, assuming laminar flow conditions without fluctuations. In contrast, oscillatory flows introduce several additional complexities, including unsteady forces such as added mass and Basset history forces, which induce complex dynamics (van Overveld et al. Reference van Overveld, Clercx and Duran-Matute2023). Notably, analytical solutions to the problem have been derived for specific cases, such as the periodic motion of a small particle in an unbounded viscous fluid (Coimbra & Rangel Reference Coimbra and Rangel2001), which was later experimentally validated (Coimbra et al. Reference Coimbra, L’esperance, Lambert, Trolinger and Rangel2004). More generally, analytical approaches for particle motion in time-dependent flows have been developed, provided the velocity field is sufficiently smooth (Van Hinsberg, ten Thije Boonkkamp & Clercx Reference Van Hinsberg, ten Thije Boonkkamp and Clercx2011). Moreover, the velocity profile in an oscillatory flow is often non-monotonic, like for a Stokes boundary layer over a flat bottom. As a result, both the drag force and associated lever arm are transient quantities, yielding a complex time-varying torque. The particle’s dynamics can become even more intricate after the onset of motion. Depending on the flow’s oscillation period relative to the particle’s settling time, the particle may not settle in or even reach the next pocket in the bed before the flow reverses.

From a conceptual perspective, we classify particle behaviour into several progressive modes of motion. Initially, the particle may remain static when the hydrodynamic forces are too weak to induce any movement. As the forcing increases, the particle may exhibit a wiggling motion, characterised by brief periodic movements, typically near moments of maximum drag or shear stress. By definition, the amplitude of this motion is small, as the particle remains within a single pocket of the bed, falling back into its original position and coming to rest before the ambient flow reverses direction. This motion is expected to be periodic under laminar flow conditions where fluctuations are absent. As the driving forces continue to increase, the particle may start to roll between pockets in the bed, always maintaining contact with at least one other particle. Rolling is expected to precede any slipping or sliding, consistent with predictions for unidirectional flow (Agudo et al. Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017). Even under laminar flow conditions, this rolling motion can be aperiodic, with the particle approaching a neighbouring pocket but not coming to rest before the flow direction reverses. When the driving force is sufficiently large to lift the particle temporarily from the substrate, it may hop between pockets (Topic et al. Reference Topic, Agudo, Luzi, Czech and Wierschem2022). As the driving force increases further, the particle may eventually become suspended for extended periods, moving freely without touching the substrate.

In this work, we comprehensively explore the threshold of particle motion under oscillatory flow conditions and the subsequent dynamics post-initiation. We first analyse the governing equations, provide theoretical predictions for the relevant dimensionless parameters and make quantitative predictions for the conditions at the onset of motion. We then extend our study using laboratory experiments, exploring the parameter space to identify the threshold for different flow conditions using a combination of particle tracking and particle image velocimetry (PIV). We complement our experimental findings with direct numerical simulation (DNS) to give insight into the transient forces acting on the particle and to explore the three-dimensional flow field near the onset of motion. The flow field around the particles in the simulations is fully resolved, with the particles accounted for using an immersed boundary method. To faithfully reproduce the motion onset, the numerical framework is supplemented by a particle–particle contact model that accounts for the build-up and release of elastic energy around contact points when the particle is still at rest. Throughout our broad approach, we particularly pay attention to the implications of the additional degree of freedom, distinguishing it from the more commonly studied unidirectional flow cases.

The work is structured as follows. We give an overview of the system in § 2, followed by the experimental approach in § 3 and the numerical approach in § 4. The results with accompanying discussion and comparison to other criteria are given in § 5, and concluding remarks in § 6.

2. Formulation of the problem

We first present a systematic overview of the physical system consisting of a single mobile, spherical particle resting on top of one fixed layer of monosized spherical particles, hereafter referred to as substrate. The oscillatory flow of an incompressible Newtonian fluid is driven by an externally imposed harmonic pressure gradient over a horizontal flat wall, resulting in an oscillatory boundary layer (OBL). Figures 1(b) and 1(c) provide accompanying sketches of the particle and flow configuration. For a regular substrate, the relevant dimensional parameters are the particle diameter

![]() $D$

, the amplitude of velocity oscillations far from the bottom

$D$

, the amplitude of velocity oscillations far from the bottom

![]() $U_0$

, the angular oscillation frequency

$U_0$

, the angular oscillation frequency

![]() $\omega$

, the kinematic viscosity of the fluid

$\omega$

, the kinematic viscosity of the fluid

![]() $\nu$

, the fluid density

$\nu$

, the fluid density

![]() $\rho _{\!f}$

, the particle density

$\rho _{\!f}$

, the particle density

![]() $\rho _s$

, the gravitational acceleration

$\rho _s$

, the gravitational acceleration

![]() $g$

, the exposure height of the particle to the ambient flow

$g$

, the exposure height of the particle to the ambient flow

![]() $h$

and the elevation

$h$

and the elevation

![]() $l$

of the particle centre relative to its contact points with the bed. These quantities and other main parameters are listed in table 1.

$l$

of the particle centre relative to its contact points with the bed. These quantities and other main parameters are listed in table 1.

Table 1. Overview of the main parameters describing material properties, oscillation characteristics, geometric configuration (cf. figure 1), and relevant forces and associated lever arms.

2.1. Governing equations

2.1.1. Fluid motion

The flow is governed by the continuity equation

and by the incompressible Navier–Stokes equation

where

![]() $p$

is the pressure,

$p$

is the pressure,

![]() $t$

is the time and

$t$

is the time and

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}=(u,v,w)$

is the fluid velocity with the components referred to the Cartesian coordinates

$\boldsymbol{u}=(u,v,w)$

is the fluid velocity with the components referred to the Cartesian coordinates

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}=(x,y,z)$

. The unit vector

${\boldsymbol{x}}=(x,y,z)$

. The unit vector

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

points in the

$\widehat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

points in the

![]() $x$

-direction, aligned with the oscillatory flow, and

$x$

-direction, aligned with the oscillatory flow, and

![]() $z$

denotes the wall-normal coordinate pointing upwards. The last term in (2.2) corresponds to the imposed oscillatory pressure gradient.

$z$

denotes the wall-normal coordinate pointing upwards. The last term in (2.2) corresponds to the imposed oscillatory pressure gradient.

In the laminar regime, the velocity in the oscillatory boundary layer over a flat, smooth wall located at

![]() $z=z_0$

, is given by the Stokes boundary layer solution

$z=z_0$

, is given by the Stokes boundary layer solution

where

![]() $\delta _S=\sqrt {2\nu /\omega }$

denotes the boundary layer thickness, i.e. the characteristic viscous length scale (Landau & Lifshitz Reference Landau and Lifshitz1987; Acheson Reference Acheson1990).

$\delta _S=\sqrt {2\nu /\omega }$

denotes the boundary layer thickness, i.e. the characteristic viscous length scale (Landau & Lifshitz Reference Landau and Lifshitz1987; Acheson Reference Acheson1990).

The presence of bottom roughness adds a remarkable complexity to the problem, even when the roughness elements are monosized spherical particles arranged regularly on a horizontal wall (Mazzuoli et al. Reference Mazzuoli, Kidanemariam, Blondeaux, Vittori and Uhlmann2016; Agudo et al. Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017). Notably, roughness can amplify nonlinear effects, such as steady streaming (Lyne Reference Lyne1971; Riley Reference Riley2001), and thereby influence the stability of the oscillatory boundary layer, eventually causing a transition to turbulence (Mazzuoli & Vittori Reference Mazzuoli and Vittori2016; Kaptein et al. Reference Kaptein, Duran-Matute, Roman, Armenio and Clercx2020). Presently, we consider a compact square arrangement of the bottom substrate.

The influence of substrate roughness on the undisturbed flow is reflected in the velocity field overlapping with the top layer of the substrate. In other words, the flow does not vanish at the top of the substrate, but instead penetrates into it to some extent. When modelling the flow using a Stokes profile, this effective penetration is accounted for by adjusting

![]() $z_0$

, the virtual wall location, as illustrated in figure 1(c). In practice,

$z_0$

, the virtual wall location, as illustrated in figure 1(c). In practice,

![]() $z_0$

is chosen such that far above the substrate, the Stokes velocity profile matches the velocity field obtained from the DNS or experiments. Note that the mean velocity at

$z_0$

is chosen such that far above the substrate, the Stokes velocity profile matches the velocity field obtained from the DNS or experiments. Note that the mean velocity at

![]() $z=z_0$

in the DNS or experiments does not necessarily vanish. The influence of substrate roughness on the flow experienced by the mobile particle is quantified by the particle exposure height

$z=z_0$

in the DNS or experiments does not necessarily vanish. The influence of substrate roughness on the flow experienced by the mobile particle is quantified by the particle exposure height

where

![]() $z_b$

is the bottom elevation of the mobile particle.

$z_b$

is the bottom elevation of the mobile particle.

2.1.2. Particle motion

The translational velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_s$

of a spherical particle is described by Newton’s second law

$\boldsymbol{u}_s$

of a spherical particle is described by Newton’s second law

where

![]() $V_s=\pi D^3/6$

is the particle volume,

$V_s=\pi D^3/6$

is the particle volume,

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt B}$

is the resultant of body forces,

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt B}$

is the resultant of body forces,

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt C}$

is the resultant of inter-particle contacts due to interactions with the substrate and

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt C}$

is the resultant of inter-particle contacts due to interactions with the substrate and

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}$

is the resultant of surface forces

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}$

is the resultant of surface forces

where

![]() $P$

denotes the imposed pressure,

$P$

denotes the imposed pressure,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tau }_\nu$

the viscous stress tangential to the sphere surface

$\boldsymbol{\tau }_\nu$

the viscous stress tangential to the sphere surface

![]() $\mathcal S$

, and

$\mathcal S$

, and

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}$

the surface-normal unit vector. In the

$\boldsymbol{n}$

the surface-normal unit vector. In the

![]() $x$

-direction, following Maxey–Riley–Gatignol’s approach, the hydrodynamic force

$x$

-direction, following Maxey–Riley–Gatignol’s approach, the hydrodynamic force

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}$

can be modelled as the sum of the drag force and contributions from added mass, Basset force and imposed pressure gradient (Gatignol Reference Gatignol1983; Maxey & Riley Reference Maxey and Riley1983). While not strictly exact, this decomposition provides a reasonable approximation for small particles, where drag is predominantly viscous and the effects of flow unsteadiness, captured by the added mass, Basset and pressure gradient terms, can be effectively treated as additional contributions to the steady-state drag model. In the

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}$

can be modelled as the sum of the drag force and contributions from added mass, Basset force and imposed pressure gradient (Gatignol Reference Gatignol1983; Maxey & Riley Reference Maxey and Riley1983). While not strictly exact, this decomposition provides a reasonable approximation for small particles, where drag is predominantly viscous and the effects of flow unsteadiness, captured by the added mass, Basset and pressure gradient terms, can be effectively treated as additional contributions to the steady-state drag model. In the

![]() $z$

-direction, the hydrodynamic force corresponds to the lift force.

$z$

-direction, the hydrodynamic force corresponds to the lift force.

The net body force

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt B}$

, proportional to the volume occupied by the particle, results from the sum of contributions due to gravity and buoyancy

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt B}$

, proportional to the volume occupied by the particle, results from the sum of contributions due to gravity and buoyancy

where

![]() $g$

is the gravitational acceleration pointing in the negative

$g$

is the gravitational acceleration pointing in the negative

![]() $z$

-direction,

$z$

-direction,

![]() $-\hat {\boldsymbol{z}}$

.

$-\hat {\boldsymbol{z}}$

.

The rotation of a spherical particle is described by Euler’s second law

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{\varOmega }_s$

denotes the particle angular velocity. The torques acting on the particle arise from interactions with the substrate

$\boldsymbol{\varOmega }_s$

denotes the particle angular velocity. The torques acting on the particle arise from interactions with the substrate

![]() $\boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt C}$

and hydrodynamic viscous stresses

$\boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt C}$

and hydrodynamic viscous stresses

with

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_c$

denoting the particle centre coordinates. For a rolling particle in the compact square arrangement (cf. figure 1

b), rotation occurs around the contact point at elevation

$\boldsymbol{x}_c$

denoting the particle centre coordinates. For a rolling particle in the compact square arrangement (cf. figure 1

b), rotation occurs around the contact point at elevation

![]() $z_D$

. The distance between

$z_D$

. The distance between

![]() $z_D$

and the particle centre elevation is given by

$z_D$

and the particle centre elevation is given by

as shown in figure 1(c).

2.2. Dimensional considerations

Let us now consider the following dimensionless variables of the hydrodynamic problem, indicated with asterisks,

which were also considered by Mazzuoli & Vittori (Reference Mazzuoli and Vittori2016). Moreover, the following dimensionless quantities characterising the particle dynamics are introduced

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{x}_s^* &= \dfrac {\boldsymbol{x}_s}{D}, \quad \boldsymbol{u}_s^* = \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_s}{U_0}, \quad \boldsymbol{\varOmega }_s^* = \frac {D\boldsymbol{\varOmega }_s}{U_0}, \quad \boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt C}^* = \frac {\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt C}}{{\mathcal W}_s}, \quad \boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt C}^* = \frac {2\boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt C}}{{\mathcal W}_sD}, \nonumber \\ \quad \boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}^* &= \frac {\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}}{\tau _{\nu 0}\pi D^2}, \quad \boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt S}^* = \frac {2\boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt S}}{\tau _{\nu 0}\pi D^3}, \quad \boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt B}^* = \frac {\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt B}}{{\mathcal W}_s}, \quad \boldsymbol{T}_B^* = \frac {2\boldsymbol{T}_B}{{\mathcal W}_sD}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{x}_s^* &= \dfrac {\boldsymbol{x}_s}{D}, \quad \boldsymbol{u}_s^* = \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_s}{U_0}, \quad \boldsymbol{\varOmega }_s^* = \frac {D\boldsymbol{\varOmega }_s}{U_0}, \quad \boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt C}^* = \frac {\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt C}}{{\mathcal W}_s}, \quad \boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt C}^* = \frac {2\boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt C}}{{\mathcal W}_sD}, \nonumber \\ \quad \boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}^* &= \frac {\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}}{\tau _{\nu 0}\pi D^2}, \quad \boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt S}^* = \frac {2\boldsymbol{T}_{\kern-1.5pt S}}{\tau _{\nu 0}\pi D^3}, \quad \boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt B}^* = \frac {\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt B}}{{\mathcal W}_s}, \quad \boldsymbol{T}_B^* = \frac {2\boldsymbol{T}_B}{{\mathcal W}_sD}, \end{align}

where the contact forces are normalised by the particle submerged weight

![]() ${\mathcal W}_s=(\rho _s-\rho _{\!f})gV_s$

, and the hydrodynamic forces are normalised by the characteristic viscous shear stress

${\mathcal W}_s=(\rho _s-\rho _{\!f})gV_s$

, and the hydrodynamic forces are normalised by the characteristic viscous shear stress

![]() $\tau _{\nu 0}=\rho _{\!f}U_0\omega \delta _S/2$

multiplied by the area of the particle surface

$\tau _{\nu 0}=\rho _{\!f}U_0\omega \delta _S/2$

multiplied by the area of the particle surface

![]() $\pi D^2$

.

$\pi D^2$

.

We now use (2.11) and (2.12) to non-dimensionalise the governing equations for both the fluid phase and the particle motion. Hence, the dimensionless form of (2.1) and (2.2) reads

and

respectively, where

is the Reynolds number of the oscillatory boundary layer. Substitution into (2.5) and (2.8) yields

for the particle translation and

for the particle rotation, where

is the particle–fluid density ratio,

is the normalised viscous length scale, and

is the ratio between the amplitude of the oscillatory acceleration far from the bottom and the specific gravitational acceleration. From this point onward, all variables are non-dimensional unless otherwise indicated and the asterisks are omitted for notational convenience.

According to (2.16), when lift forces (i.e. the vertical component of

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}$

) are relatively small, vertical motion is primarily determined by the balance between contact forces and effective weight, with the dimensionless acceleration being inversely proportional to

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}$

) are relatively small, vertical motion is primarily determined by the balance between contact forces and effective weight, with the dimensionless acceleration being inversely proportional to

![]() $s\varGamma$

. Horizontal motion is governed by the horizontal components of the contact force

$s\varGamma$

. Horizontal motion is governed by the horizontal components of the contact force

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt C}$

and the hydrodynamic force

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt C}$

and the hydrodynamic force

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}$

, the latter comprising contributions from the imposed pressure gradient and drag, which are proportional to

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\kern-1.5pt S}$

, the latter comprising contributions from the imposed pressure gradient and drag, which are proportional to

![]() $\delta /s$

.

$\delta /s$

.

The dynamic problem involves nine distinct dimensional parameters (

![]() $U_0$

,

$U_0$

,

![]() $D$

,

$D$

,

![]() $\omega$

,

$\omega$

,

![]() $\rho _{\!f}$

,

$\rho _{\!f}$

,

![]() $\rho _s$

,

$\rho _s$

,

![]() $\nu$

,

$\nu$

,

![]() $g$

,

$g$

,

![]() $h$

,

$h$

,

![]() $l$

) and is, therefore, uniquely characterised by six independent dimensionless parameters. Four of these already appeared in the governing equations:

$l$

) and is, therefore, uniquely characterised by six independent dimensionless parameters. Four of these already appeared in the governing equations:

![]() $\delta$

,

$\delta$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_\delta$

,

${\textit{Re}}_\delta$

,

![]() $s$

and

$s$

and

![]() $\varGamma$

. In addition, the dynamics of the exposed particle depend on two geometric parameters,

$\varGamma$

. In addition, the dynamics of the exposed particle depend on two geometric parameters,

![]() $H=h/D$

and

$H=h/D$

and

![]() $L = l/D$

, which relate to the substrate arrangement and are defined by (2.4) and (2.10), respectively.

$L = l/D$

, which relate to the substrate arrangement and are defined by (2.4) and (2.10), respectively.

Combinations of these numbers result in other dimensionless quantities that are frequently considered in sediment transport problems, such as the particle mobility number

which is the ratio between the convective force and the submerged weight of the particle (Mazzuoli et al. Reference Mazzuoli, Kidanemariam, Blondeaux, Vittori and Uhlmann2016, Reference Mazzuoli, Kidanemariam and Uhlmann2019; Vittori et al. Reference Vittori, Blondeaux, Mazzuoli, Simeonov and Calantoni2020).

Finally, the bulk flow velocity

![]() $U_0$

does not necessarily represent the local flow around the mobile particle, especially when

$U_0$

does not necessarily represent the local flow around the mobile particle, especially when

![]() $\delta$

is large. The flow conditions near the substrate are better captured by the Shields parameter, representing the dimensionless shear stress at the bed as

$\delta$

is large. The flow conditions near the substrate are better captured by the Shields parameter, representing the dimensionless shear stress at the bed as

where

![]() $\tau _0$

denotes the instantaneous bottom shear stress. According to the Shields criterion, this stress represents the horizontal hydrodynamic force per unit area acting on the top layer of particles resting on the substrate. This force is approximately equal to the shear stress evaluated at an elevation

$\tau _0$

denotes the instantaneous bottom shear stress. According to the Shields criterion, this stress represents the horizontal hydrodynamic force per unit area acting on the top layer of particles resting on the substrate. This force is approximately equal to the shear stress evaluated at an elevation

![]() $z_0$

, which typically lies within one particle diameter

$z_0$

, which typically lies within one particle diameter

![]() $D$

above the base of the top layer

$D$

above the base of the top layer

![]() $z_b$

(see figure 1

a). In our configuration, where the mobile layer consists of a single particle and the particle-induced disturbance to the flow is negligible,

$z_b$

(see figure 1

a). In our configuration, where the mobile layer consists of a single particle and the particle-induced disturbance to the flow is negligible,

![]() $z_0$

is close to

$z_0$

is close to

![]() $z_b$

(see figure 1

c). Consequently, the shear stress at

$z_b$

(see figure 1

c). Consequently, the shear stress at

![]() $z_0$

closely approximates the actual shear stress acting at the base of the mobile particle. In the absence of a substrate (i.e. a single sphere lying on a smooth wall),

$z_0$

closely approximates the actual shear stress acting at the base of the mobile particle. In the absence of a substrate (i.e. a single sphere lying on a smooth wall),

![]() $\tau _{0}$

can be computed by evaluating the derivative of the Stokes profile (2.3) at

$\tau _{0}$

can be computed by evaluating the derivative of the Stokes profile (2.3) at

![]() $z=z_0=0$

, yielding

$z=z_0=0$

, yielding

![]() $\theta = (\sqrt {2}/2)\delta \varGamma \sin (t+\pi /4 )$

. Finally, we stress that, in contrast to steady flow conditions, the Shields parameter

$\theta = (\sqrt {2}/2)\delta \varGamma \sin (t+\pi /4 )$

. Finally, we stress that, in contrast to steady flow conditions, the Shields parameter

![]() $\theta$

in (2.22) oscillates over time, implying that both the magnitude and the duration of the hydrodynamic forcing determine the onset of motion.

$\theta$

in (2.22) oscillates over time, implying that both the magnitude and the duration of the hydrodynamic forcing determine the onset of motion.

2.3. Model for the motion threshold

The detailed derivation underlying the model for the motion threshold is given in Appendix A, while the main concepts are summarised in this section.

Under the assumption that an exposed particle is more likely to roll rather than slip or slide out of a pocket in the bed (Agudo et al. Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017), the motion threshold is governed by a torque balance. This balance includes a stabilising contribution from the submerged weight and typically destabilising contributions from drag, lift, added mass and the imposed pressure gradient. However, these torques may be out of phase, meaning some may have stabilising effects during parts of the oscillation cycle. The Basset history term is omitted from the present balance, since its contribution is expected to be small for the range of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_\delta$

considered. In the absence of a substrate, its magnitude is approximately

${\textit{Re}}_\delta$

considered. In the absence of a substrate, its magnitude is approximately

![]() $10\,\%{-}20\,\%$

of drag, while precise evaluation in the present geometry remains challenging. Moreover, since the history force is related to flow acceleration, its phase does not coincide with that of the drag force, further limiting its influence on the onset of particle motion.

$10\,\%{-}20\,\%$

of drag, while precise evaluation in the present geometry remains challenging. Moreover, since the history force is related to flow acceleration, its phase does not coincide with that of the drag force, further limiting its influence on the onset of particle motion.

Lubrication forces are not included, as prior studies have shown good agreement without them (Agudo et al. Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017), and they are not expected to be significant compared with dominant contributions such as drag and pressure gradients in the present parameter range. The dimensionless spanwise component of the particle torque

![]() $\boldsymbol{T}$

referred to an arbitrary point is defined by

$\boldsymbol{T}$

referred to an arbitrary point is defined by

where the terms on the right-hand side denote contributions of drag, lift, added mass, pressure gradient, submerged weight and inter-particle contacts, respectively. In this section, let us evaluate the torque contributions referring to the contact point elevation at the incipient rolling conditions, i.e. when

![]() $T_{y}=0$

and the mobile particle has only two contact points aligned in the spanwise direction, such that also

$T_{y}=0$

and the mobile particle has only two contact points aligned in the spanwise direction, such that also

![]() $T_{Cy}=0$

. Therefore, in the definition of the spanwise component of the hydrodynamic torque

$T_{Cy}=0$

. Therefore, in the definition of the spanwise component of the hydrodynamic torque

![]() $T_{\textit{Sy}}$

provided by (2.9), the coordinates

$T_{\textit{Sy}}$

provided by (2.9), the coordinates

![]() $(x_c,z_c)$

are replaced by

$(x_c,z_c)$

are replaced by

![]() $(x_D,z_D)$

.

$(x_D,z_D)$

.

The primary challenge lies in relating the hydrodynamic torque contributions to the ambient flow, for which we adopt an approach similar to that of Agudo et al. (Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017) for steady shear flows. In general, there is no analytical formulation for the velocity field

![]() $u$

that captures all substrate-induced variations. Therefore, we introduce a horizontal plane-average to obtain an effective velocity profile that represents the mean flow. This averaged profile is defined as

$u$

that captures all substrate-induced variations. Therefore, we introduce a horizontal plane-average to obtain an effective velocity profile that represents the mean flow. This averaged profile is defined as

where

![]() $\mathcal A$

denotes the substrate area. The averaging procedure accounts for spatial velocity variations induced by the substrate, which are present even in non-turbulent flow conditions. Notably, while the ambient flow is free of turbulent fluctuations, random velocity fluctuations may still appear in the wake downstream of the mobile particle.

$\mathcal A$

denotes the substrate area. The averaging procedure accounts for spatial velocity variations induced by the substrate, which are present even in non-turbulent flow conditions. Notably, while the ambient flow is free of turbulent fluctuations, random velocity fluctuations may still appear in the wake downstream of the mobile particle.

Although

![]() $\langle u\rangle$

cannot be computed analytically, our numerical simulations provide full access to the three-dimensional velocity field, allowing us to evaluate the plane-average directly. The resulting mean velocity profiles are well approximated by a vertically shifted Stokes solution (2.3) (see figure 16 in Appendix A) for the parameter values presently considered. The torque due to the hydrodynamic drag is defined as the moment of the drag force with respect to the contact point between the particle and the substrate. For the spherical particle, this torque is modelled as

$\langle u\rangle$

cannot be computed analytically, our numerical simulations provide full access to the three-dimensional velocity field, allowing us to evaluate the plane-average directly. The resulting mean velocity profiles are well approximated by a vertically shifted Stokes solution (2.3) (see figure 16 in Appendix A) for the parameter values presently considered. The torque due to the hydrodynamic drag is defined as the moment of the drag force with respect to the contact point between the particle and the substrate. For the spherical particle, this torque is modelled as

according to (A5), where

is the first moment of the streamwise ambient velocity (see (A3)) with

![]() $z_b$

and

$z_b$

and

![]() $z_D$

denoting the

$z_D$

denoting the

![]() $z$

-coordinates of the lowest point of the exposed particle and of the rotation axis, respectively (see figure 1

c). Similarly, the contribution of lift to the hydrodynamic torque is based on Saffman’s (Reference Saffman1965) expression, see (A15). Notably, both the expressions of drag and lift in dimensionless form contain correction coefficients that depend on the instantaneous particle Reynolds number

$z$

-coordinates of the lowest point of the exposed particle and of the rotation axis, respectively (see figure 1

c). Similarly, the contribution of lift to the hydrodynamic torque is based on Saffman’s (Reference Saffman1965) expression, see (A15). Notably, both the expressions of drag and lift in dimensionless form contain correction coefficients that depend on the instantaneous particle Reynolds number

where

![]() $u_c$

denotes the ambient velocity at the same elevation as the particle centre and

$u_c$

denotes the ambient velocity at the same elevation as the particle centre and

![]() $\zeta =(H-1/2)/\delta$

is the normalised elevation of the particle centre above the zero level of the velocity profile

$\zeta =(H-1/2)/\delta$

is the normalised elevation of the particle centre above the zero level of the velocity profile

![]() $z_0$

.

$z_0$

.

The ratio

![]() $\varUpsilon$

between the aforementioned destabilising contributions and the stabilising contribution due to submerged weight is given by

$\varUpsilon$

between the aforementioned destabilising contributions and the stabilising contribution due to submerged weight is given by

\begin{align} \varUpsilon &\equiv \dfrac {T_{\textit{Sy}}^{\textit{drag}}+T^{\boldsymbol{\nabla}\kern-1pt p}_{\textit{Sy}}+T_{\textit{Sy}}^{\textit{AM}}+T_{\textit{Sy}}^{\textit{lift}}}{T_{\textit{By}}} \nonumber\\ &=4\varGamma \left [ 9C'\delta ^2H g\left (t,\frac {H}{\delta }\right )\,L_D + h(t,\zeta )\,L + \frac {9.66}{\pi \sqrt {2}}\,C^{\prime \prime }\dfrac {\delta ^3}{{\textit{Re}}_\delta }\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}_s^3}L_L \right ]\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \varUpsilon &\equiv \dfrac {T_{\textit{Sy}}^{\textit{drag}}+T^{\boldsymbol{\nabla}\kern-1pt p}_{\textit{Sy}}+T_{\textit{Sy}}^{\textit{AM}}+T_{\textit{Sy}}^{\textit{lift}}}{T_{\textit{By}}} \nonumber\\ &=4\varGamma \left [ 9C'\delta ^2H g\left (t,\frac {H}{\delta }\right )\,L_D + h(t,\zeta )\,L + \frac {9.66}{\pi \sqrt {2}}\,C^{\prime \prime }\dfrac {\delta ^3}{{\textit{Re}}_\delta }\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}_s^3}L_L \right ]\!, \end{align}

where

![]() $C'$

and

$C'$

and

![]() $C''$

are correction coefficients for the drag and lift forces, respectively, and

$C''$

are correction coefficients for the drag and lift forces, respectively, and

![]() $L_D$

and

$L_D$

and

![]() $L_L$

are their corresponding lever arms, as detailed in Appendix A. The function

$L_L$

are their corresponding lever arms, as detailed in Appendix A. The function

captures the effect of shielding by the substrate, and

groups the contributions of the pressure gradient and added mass. Equation (2.28) allows us to define the criterion for the initiation of rolling motion, depending on (dimensionless) time

![]() $t$

and five dimensionless numbers:

$t$

and five dimensionless numbers:

Note that the contribution of

![]() $s$

to the threshold is contained within the parameter

$s$

to the threshold is contained within the parameter

![]() $\varGamma$

. Once the threshold is exceeded,

$\varGamma$

. Once the threshold is exceeded,

![]() $s$

becomes an independent control parameter that governs the relative importance of particle inertia in the dynamics.

$s$

becomes an independent control parameter that governs the relative importance of particle inertia in the dynamics.

Both

![]() $H$

and

$H$

and

![]() $L$

are primarily determined by the geometry of the bottom substrate. For a substrate composed of spheres in a compact square arrangement,

$L$

are primarily determined by the geometry of the bottom substrate. For a substrate composed of spheres in a compact square arrangement,

![]() $L = \sqrt {2}/4 \approx 0.35$

. The value of

$L = \sqrt {2}/4 \approx 0.35$

. The value of

![]() $H$

is related to the effective position of the virtual origin

$H$

is related to the effective position of the virtual origin

![]() $z_0$

of the velocity profile within the substrate crevices. In a similar substrate configuration but under steady flow conditions, Agudo et al. (Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017) and Topic et al. (Reference Topic, Agudo, Luzi, Czech and Wierschem2022) positioned

$z_0$

of the velocity profile within the substrate crevices. In a similar substrate configuration but under steady flow conditions, Agudo et al. (Reference Agudo, Illigmann, Luzi, Laukart, Delgado and Wierschem2017) and Topic et al. (Reference Topic, Agudo, Luzi, Czech and Wierschem2022) positioned

![]() $z_0$

at a distance

$z_0$

at a distance

![]() $0.077D$

below the top of the substrate, corresponding to

$0.077D$

below the top of the substrate, corresponding to

![]() $H=2L+0.077\approx 0.78$

. In our DNS results,

$H=2L+0.077\approx 0.78$

. In our DNS results,

![]() $H\approx 0.84$

(cf. table 2).

$H\approx 0.84$

(cf. table 2).

To get familiar with the

![]() $\varUpsilon$

-criterion (2.28)–(2.31) and distinguish the different contributions to the particle torque, figure 2(a) shows the time variation of

$\varUpsilon$

-criterion (2.28)–(2.31) and distinguish the different contributions to the particle torque, figure 2(a) shows the time variation of

![]() $\varUpsilon$

for constant parameters

$\varUpsilon$

for constant parameters

![]() $H=0.8$

,

$H=0.8$

,

![]() $L=0.35$

and

$L=0.35$

and

![]() $\varGamma =0.45$

, which are representative of the present experimental and numerical conditions.

$\varGamma =0.45$

, which are representative of the present experimental and numerical conditions.

Figure 2. (a) Temporal evolution of the motion threshold parameter

![]() $\varUpsilon$

, as defined by (2.28), for typical parameter values in the present experiments and simulations (specifically matching DNS run 3, see table 2):

$\varUpsilon$

, as defined by (2.28), for typical parameter values in the present experiments and simulations (specifically matching DNS run 3, see table 2):

![]() $\delta =0.12$

,

$\delta =0.12$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_\delta =41$

,

${\textit{Re}}_\delta =41$

,

![]() $\varGamma =0.45$

,

$\varGamma =0.45$

,

![]() $s=1.81$

,

$s=1.81$

,

![]() $H=0.8$

and

$H=0.8$

and

![]() $L=0.36$

(black line). Dotted lines represent relative contributions of hydrodynamic drag (blue), lift (green) and added mass plus imposed pressure gradient (red). (b) Normalised time interval

$L=0.36$

(black line). Dotted lines represent relative contributions of hydrodynamic drag (blue), lift (green) and added mass plus imposed pressure gradient (red). (b) Normalised time interval

![]() $\Delta t_{\varUpsilon \gt 1}$

during which the motion threshold condition (2.31) is exceeded, as a function of

$\Delta t_{\varUpsilon \gt 1}$

during which the motion threshold condition (2.31) is exceeded, as a function of

![]() $\varGamma$

(proportional to the forcing strength) for various values of

$\varGamma$

(proportional to the forcing strength) for various values of

![]() $\delta$

, with other parameters as in panel (a). Crosses mark the characteristic time scale

$\delta$

, with other parameters as in panel (a). Crosses mark the characteristic time scale

![]() $\tau$

(2.33) for the particle to reach the crest of the substrate.

$\tau$

(2.33) for the particle to reach the crest of the substrate.

2.4. Particle motion just above the motion threshold

Assuming that the particle rolls during the early stages of its motion, as verified in § 5.1, we define the spanwise rotation angle

![]() $\phi _s$

as the angle swept by the particle while rolling from its initial position to the crest of the substrate particle, before settling into the adjacent pocket. For the present substrate configuration, a compact square arrangement, we find

$\phi _s$

as the angle swept by the particle while rolling from its initial position to the crest of the substrate particle, before settling into the adjacent pocket. For the present substrate configuration, a compact square arrangement, we find

![]() $\phi _s=\pi /2-\arctan (\sqrt {2})\approx 0.62$

. The angle

$\phi _s=\pi /2-\arctan (\sqrt {2})\approx 0.62$

. The angle

![]() $\phi _s$

may alternatively be obtained by integrating Euler’s second law (2.17) twice with respect to time, which yields

$\phi _s$

may alternatively be obtained by integrating Euler’s second law (2.17) twice with respect to time, which yields

where

![]() $\tau$

denotes the characteristic (dimensionless) time for the particle to reach the substrate crest, hereafter referred to as the ‘time to crest’, and

$\tau$

denotes the characteristic (dimensionless) time for the particle to reach the substrate crest, hereafter referred to as the ‘time to crest’, and

![]() $T_{\textit{Sy}}$

and

$T_{\textit{Sy}}$

and

![]() $T_{Cy}$

represent the characteristic values of the respective torque components during this time. Close to the motion threshold, the difference between stabilising and destabilising torques is small. Based on the scaling analysis in § 2.2, the resultant dimensionless torque (i.e. the left-hand side of (2.17)) is expected to be of order unity during the early stages of motion. Furthermore, the same analysis suggests that

$T_{Cy}$

represent the characteristic values of the respective torque components during this time. Close to the motion threshold, the difference between stabilising and destabilising torques is small. Based on the scaling analysis in § 2.2, the resultant dimensionless torque (i.e. the left-hand side of (2.17)) is expected to be of order unity during the early stages of motion. Furthermore, the same analysis suggests that

![]() $3\delta T_{\textit{Sy}}$

and

$3\delta T_{\textit{Sy}}$

and

![]() $T_{Cy}/\varGamma$

, i.e. the terms between brackets in (2.32), are typically of the same order of magnitude. Then, the characteristic time to crest scales as

$T_{Cy}/\varGamma$

, i.e. the terms between brackets in (2.32), are typically of the same order of magnitude. Then, the characteristic time to crest scales as

where

![]() $K_C=U_0/(\omega D)$

is the Keulegan–Carpenter number, describing the relative importance of hydrodynamic drag to inertial forces in oscillatory flows. The range of

$K_C=U_0/(\omega D)$

is the Keulegan–Carpenter number, describing the relative importance of hydrodynamic drag to inertial forces in oscillatory flows. The range of

![]() $K_C$

values covered in this study spans from 2.5 to 80 in the simulations and from 0.58 to 10 in the experiments.

$K_C$

values covered in this study spans from 2.5 to 80 in the simulations and from 0.58 to 10 in the experiments.

Figure 2(b) shows the normalised time interval

![]() $\Delta t_{|\varUpsilon |\gt 1}$

, representing the fraction of the oscillation period during which the motion threshold (2.31) is met. The prediction of

$\Delta t_{|\varUpsilon |\gt 1}$

, representing the fraction of the oscillation period during which the motion threshold (2.31) is met. The prediction of

![]() $\Delta t_{|\varUpsilon |\gt 1}$

is crucial for determining whether a particle can accelerate sufficiently to overcome substrate barriers and settle into neighbouring pockets before flow reversal. At low forcing (small

$\Delta t_{|\varUpsilon |\gt 1}$

is crucial for determining whether a particle can accelerate sufficiently to overcome substrate barriers and settle into neighbouring pockets before flow reversal. At low forcing (small

![]() $\varGamma$

), the threshold is typically not exceeded (

$\varGamma$

), the threshold is typically not exceeded (

![]() $\Delta t_{|\varUpsilon |\gt 1}=0$

). As

$\Delta t_{|\varUpsilon |\gt 1}=0$

). As

![]() $\varGamma$

increases,

$\varGamma$

increases,

![]() $\Delta t_{|\varUpsilon |\gt 1}$

grows rapidly and asymptotically approaches

$\Delta t_{|\varUpsilon |\gt 1}$

grows rapidly and asymptotically approaches

![]() $2\pi$

, corresponding to continuous particle motion throughout the oscillation cycle. The dependence on

$2\pi$

, corresponding to continuous particle motion throughout the oscillation cycle. The dependence on

![]() $\delta$

reflects the effect of flow uniformity at the particle scale, where larger values of

$\delta$

reflects the effect of flow uniformity at the particle scale, where larger values of

![]() $\delta$

(more shear-like flow) promote particle motion at lower

$\delta$

(more shear-like flow) promote particle motion at lower

![]() $\varGamma$

, for otherwise identical parameters. The figure also shows the predicted time to crest (2.33), marked by crosses. Below each cross, the duration during which

$\varGamma$

, for otherwise identical parameters. The figure also shows the predicted time to crest (2.33), marked by crosses. Below each cross, the duration during which

![]() $|\varUpsilon |\geq 1$

is too short for the particle to roll over the crest of the substrate particle, resulting in wiggling motion. Above the cross, the particle can roll out of its pocket and reach a neighbouring one. Notably, for small

$|\varUpsilon |\geq 1$

is too short for the particle to roll over the crest of the substrate particle, resulting in wiggling motion. Above the cross, the particle can roll out of its pocket and reach a neighbouring one. Notably, for small

![]() $\delta$

, the time to crest diverges. In this regime, the oscillation frequency is sufficiently high that flow reversal occurs before the particle can accelerate sufficiently, preventing it from rolling over the substrate.

$\delta$

, the time to crest diverges. In this regime, the oscillation frequency is sufficiently high that flow reversal occurs before the particle can accelerate sufficiently, preventing it from rolling over the substrate.

3. Experimental approach

The experiments are carried out in an oscillatory flow tunnel (OFT) and serve a dual purpose. First, they enable the characterisation of flow conditions and particle behaviour as a function of the problem’s parameters close to the motion threshold. Second, they validate and inform the numerical simulations.

3.1. Experimental set-up

Figure 3 shows a schematic overview of the set-up. We use a custom-made OFT consisting of an acrylic tank with inner dimensions

![]() $(100\times 50\times 30)\,\textrm {cm}$

in the streamwise, spanwise and vertical directions, respectively. A U-shaped lid is suspended within this tank, creating a central section with two parallel flat plates spaced

$(100\times 50\times 30)\,\textrm {cm}$

in the streamwise, spanwise and vertical directions, respectively. A U-shaped lid is suspended within this tank, creating a central section with two parallel flat plates spaced

![]() ${30}\,\textrm {mm}$

apart. Each end of the tank contains a vertical section with a free surface, measuring

${30}\,\textrm {mm}$

apart. Each end of the tank contains a vertical section with a free surface, measuring

![]() ${50}\,\textrm {mm}$

in width. The tank is filled with tap water with mass density

${50}\,\textrm {mm}$

in width. The tank is filled with tap water with mass density

![]() $\rho _{\!f}=(0.999\pm 0.001)\times {10^{3}}{\,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{- 3}}$

and kinematic viscosity

$\rho _{\!f}=(0.999\pm 0.001)\times {10^{3}}{\,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{- 3}}$

and kinematic viscosity

![]() $\nu =(1.05\pm 0.01)\times {10}^{-6}{\,\textrm {m}^2\,\textrm {s}^{- 1}}$

. Special care has been taken to ensure a watertight seal between the lid and the side walls of the outer tank at the front and back (out of plane). A partially submerged piston with a width of

$\nu =(1.05\pm 0.01)\times {10}^{-6}{\,\textrm {m}^2\,\textrm {s}^{- 1}}$

. Special care has been taken to ensure a watertight seal between the lid and the side walls of the outer tank at the front and back (out of plane). A partially submerged piston with a width of

![]() ${48}\,\textrm {mm}$

is placed in the left column, covering approximately

${48}\,\textrm {mm}$

is placed in the left column, covering approximately

![]() $77\,\%$

of the free surface area (as seen from above). The piston is driven by a PID-controlled linear motor (LinMot P01-37×120F/100×180-HP) in a vertical oscillatory motion. This motion modulates the water level in the left column, generating a hydrostatic pressure difference between the left and right columns, which in turn drives the flow through the central horizontal section. The piston does not fully cover the free surface in the lateral direction, but it is sufficiently large to generate the necessary flow through vertical oscillations of the water level. A tight seal or full interfacial coverage is not required, as this would involve extreme forces and special care to prevent friction.

$77\,\%$

of the free surface area (as seen from above). The piston is driven by a PID-controlled linear motor (LinMot P01-37×120F/100×180-HP) in a vertical oscillatory motion. This motion modulates the water level in the left column, generating a hydrostatic pressure difference between the left and right columns, which in turn drives the flow through the central horizontal section. The piston does not fully cover the free surface in the lateral direction, but it is sufficiently large to generate the necessary flow through vertical oscillations of the water level. A tight seal or full interfacial coverage is not required, as this would involve extreme forces and special care to prevent friction.

Figure 3. (a) Schematic of the oscillatory flow tunnel (OFT), where a harmonically oscillating piston (grey) drives flow between two parallel flat plates. On the bottom, a single mobile particle (white) lies on top of a fixed monolayer (black), with a vertical laser sheet (green) illuminating the cross-section parallel to the oscillation direction. (b) Experimental snapshot (

![]() $\delta \approx 0.12$

and

$\delta \approx 0.12$

and

![]() $s=1.81$

) showing the substrate, exposed particle and laser-illuminated tracer particles. (c) A contrast-enhanced snapshot overlaid with velocity vectors obtained using PIV, scaled and colour-coded by magnitude (green to red for increasing velocity magnitude).

$s=1.81$

) showing the substrate, exposed particle and laser-illuminated tracer particles. (c) A contrast-enhanced snapshot overlaid with velocity vectors obtained using PIV, scaled and colour-coded by magnitude (green to red for increasing velocity magnitude).

The substrate consists of a monolayer of spheres with a diameter of

![]() $(5.950\pm 0.005)\,\textrm {mm}$

, arranged in a square lattice with

$(5.950\pm 0.005)\,\textrm {mm}$

, arranged in a square lattice with

![]() ${6.0}\,\textrm {mm}$

centre-to-centre spacing, forming a

${6.0}\,\textrm {mm}$

centre-to-centre spacing, forming a

![]() $25\times 26$

particle grid aligned with the oscillation direction. The spheres are securely positioned in circular holes (

$25\times 26$

particle grid aligned with the oscillation direction. The spheres are securely positioned in circular holes (

![]() ${3.0}\,\textrm {mm}$

in diameter) on a bottom plate, with a 5 mm-high surrounding frame preventing the layer from shifting. The bottom plate and frame are CNC milled to ensure a highly regular spacing and alignment of the substrate spheres. A single spherical particle with diameter

${3.0}\,\textrm {mm}$

in diameter) on a bottom plate, with a 5 mm-high surrounding frame preventing the layer from shifting. The bottom plate and frame are CNC milled to ensure a highly regular spacing and alignment of the substrate spheres. A single spherical particle with diameter

![]() $D={(5.950\pm 0.005)}\,\textrm {mm}$

is placed on top of the substrate approximately in the centre of the grid. Its density is either

$D={(5.950\pm 0.005)}\,\textrm {mm}$

is placed on top of the substrate approximately in the centre of the grid. Its density is either

![]() $\rho _s={(1.09\pm 0.05) \times {10}^{3}}{\,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{-3}}$

or

$\rho _s={(1.09\pm 0.05) \times {10}^{3}}{\,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{-3}}$

or

![]() $\rho _s={(1.81\pm 0.05)\times {10}^{3}}{ \,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{-3}}$

for light and heavy particles, respectively. All spheres used in the experiments are plastic BB pellets made of polylactic acid (PLA) and are specially designed to be smooth and highly spherical.

$\rho _s={(1.81\pm 0.05)\times {10}^{3}}{ \,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{-3}}$

for light and heavy particles, respectively. All spheres used in the experiments are plastic BB pellets made of polylactic acid (PLA) and are specially designed to be smooth and highly spherical.

We use PIV to characterise the oscillating flow field, specifically to measure the mean flow velocity

![]() $U_0$

far from the bed (e.g. as in figure 4) and to obtain the velocity profile near the exposed particle (cf. figure 16). A vertical two-dimensional slice of the velocity field is captured above the bed and around the exposed particle using a laser sheet approximately

$U_0$

far from the bed (e.g. as in figure 4) and to obtain the velocity profile near the exposed particle (cf. figure 16). A vertical two-dimensional slice of the velocity field is captured above the bed and around the exposed particle using a laser sheet approximately

![]() ${5}\,\textrm {mm}$

wide, similar to the particle’s diameter. The sheet is centred on the exposed particle and aligned with both the substrate grid and the oscillation direction, which limits out-of-plane reflections. The laser illuminates non-fluorescent polycrystalline tracer particles (Optimage PIV Seeding Powder with nominal diameter of

${5}\,\textrm {mm}$

wide, similar to the particle’s diameter. The sheet is centred on the exposed particle and aligned with both the substrate grid and the oscillation direction, which limits out-of-plane reflections. The laser illuminates non-fluorescent polycrystalline tracer particles (Optimage PIV Seeding Powder with nominal diameter of

![]() ${100}\, {\unicode{x03BC} } \rm{m}$

) and operates in a double-pulsed mode, emitting two pulses separated by

${100}\, {\unicode{x03BC} } \rm{m}$

) and operates in a double-pulsed mode, emitting two pulses separated by

![]() ${5.0}\,\textrm {ms}$

, with pulse pairs generated at a frequency of 15 Hz. A RedLake MegaPlus II camera equipped with a Nikon 28 mm

${5.0}\,\textrm {ms}$

, with pulse pairs generated at a frequency of 15 Hz. A RedLake MegaPlus II camera equipped with a Nikon 28 mm

![]() $f/2.8$

lens records the experiment from the side (along the

$f/2.8$

lens records the experiment from the side (along the

![]() $y$

-axis), perpendicular to the laser sheet plane (

$y$

-axis), perpendicular to the laser sheet plane (

![]() $xz$

) to further minimise reflections from the substrate and the mobile sphere. Nevertheless, some reflections near the particle are unavoidable due to the finite thickness of the sheet. Figure 3 shows a typical snapshot, where the vertical laser sheet illuminates the substrate at the bottom of the image, the mobile particle on top and the tracer particles dispersed in the fluid for PIV analysis.

$xz$

) to further minimise reflections from the substrate and the mobile sphere. Nevertheless, some reflections near the particle are unavoidable due to the finite thickness of the sheet. Figure 3 shows a typical snapshot, where the vertical laser sheet illuminates the substrate at the bottom of the image, the mobile particle on top and the tracer particles dispersed in the fluid for PIV analysis.

Figure 4. (a) Temporal evolution of the space-averaged flow velocity above the substrate,

![]() $u$

(blue), and the (normalised) particle position,

$u$

(blue), and the (normalised) particle position,

![]() $x_s$

(red), over approximately three oscillation periods, obtained from the OFT experiments (

$x_s$

(red), over approximately three oscillation periods, obtained from the OFT experiments (

![]() $s=1.81$

,

$s=1.81$

,

![]() $\delta \approx 0.11$

,

$\delta \approx 0.11$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_\delta \approx 150$

,

${\textit{Re}}_\delta \approx 150$

,

![]() $\varGamma \approx 0.13$

,

$\varGamma \approx 0.13$

,

![]() $\psi \approx 1.1$

). The velocity amplitude is gradually ramped up to identify the conditions for incipient motion. The complementary DNS data (black) show the trajectory of a rolling particle just above the motion threshold for run 4 (

$\psi \approx 1.1$

). The velocity amplitude is gradually ramped up to identify the conditions for incipient motion. The complementary DNS data (black) show the trajectory of a rolling particle just above the motion threshold for run 4 (

![]() $\psi =1.1$

). Roman numerals mark every eight frames, corresponding to the snapshots in panel (b). The inset shows the particle motion and velocity over a longer duration, with the highlighted region corresponding to the main plot.

$\psi =1.1$

). Roman numerals mark every eight frames, corresponding to the snapshots in panel (b). The inset shows the particle motion and velocity over a longer duration, with the highlighted region corresponding to the main plot.

The PIV recordings are analysed with the image processing software PIVview2C (v3.9.3). For each image pair, instantaneous velocity vectors are computed within interrogation windows of

![]() $32 \times 32$

pixels (roughly corresponding to

$32 \times 32$

pixels (roughly corresponding to

![]() $3\times {3}\,\textrm {mm}$

, approximately the particle radius), with 50 % overlap between adjacent interrogation windows (Prasad Reference Prasad2000). Each window typically contains 10–20 tracer particles. Figure 3(c) shows a typical frame after PIV analysis. A high-pass filter and pixel value threshold are applied to the original image to enhance the contrast of the tracer particles. The coloured arrows represent velocity vectors within each interrogation window.

$3\times {3}\,\textrm {mm}$

, approximately the particle radius), with 50 % overlap between adjacent interrogation windows (Prasad Reference Prasad2000). Each window typically contains 10–20 tracer particles. Figure 3(c) shows a typical frame after PIV analysis. A high-pass filter and pixel value threshold are applied to the original image to enhance the contrast of the tracer particles. The coloured arrows represent velocity vectors within each interrogation window.

Finally, a preferential path for the mobile particle may arise due to secondary flows or minor substrate irregularities. While the latter contributions are minimised by using CNC-milled components and uniform particles, factors such as imperfect levelling of the tank and inertial effects from the piston’s motion (e.g. vortex shedding) may still contribute to minor asymmetries in the flow. While these asymmetries are typically irrelevant, they can influence particle motion near the threshold, where small torque differences may result in a preferred direction of particle movement.

3.2. Measurement approach

For a given particle–fluid combination and substrate geometry, the density ratio

![]() $s$

and the geometrical parameter

$s$

and the geometrical parameter

![]() $L$

remain constant across all experiments. The parameter

$L$

remain constant across all experiments. The parameter

![]() $H$

, primarily determined by the substrate geometry (as discussed in § 2.3), is also assumed to remain approximately constant. Three independent degrees of freedom remain (

$H$

, primarily determined by the substrate geometry (as discussed in § 2.3), is also assumed to remain approximately constant. Three independent degrees of freedom remain (

![]() $\delta$

,

$\delta$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_\delta$

,

${\textit{Re}}_\delta$

,

![]() $\varGamma$

), all depending on the flow conditions. For comparison with DNS results, we also consider the particle mobility number

$\varGamma$

), all depending on the flow conditions. For comparison with DNS results, we also consider the particle mobility number

![]() $\psi =\delta {\textit{Re}}_\delta \varGamma /2$

(see (2.21)). In each experiment, the oscillation frequency

$\psi =\delta {\textit{Re}}_\delta \varGamma /2$

(see (2.21)). In each experiment, the oscillation frequency

![]() $\omega$

is fixed while gradually increasing the piston’s stroke, thereby increasing the fluid velocity amplitude

$\omega$

is fixed while gradually increasing the piston’s stroke, thereby increasing the fluid velocity amplitude

![]() $U_0$

. The constant frequency implies that the value of

$U_0$

. The constant frequency implies that the value of

![]() $\delta$

remains constant within each experiment, but varies across different trials as the frequency is adjusted. At each stroke value, the piston oscillates for ten periods before its peak-to-peak amplitude is slightly increased: by

$\delta$

remains constant within each experiment, but varies across different trials as the frequency is adjusted. At each stroke value, the piston oscillates for ten periods before its peak-to-peak amplitude is slightly increased: by

![]() ${5}\,\textrm {mm}$

at lower amplitudes and by

${5}\,\textrm {mm}$

at lower amplitudes and by

![]() ${1}\,\textrm {mm}$

near the motion threshold. The oscillation period ranges between

${1}\,\textrm {mm}$

near the motion threshold. The oscillation period ranges between

![]() $1.0$

s and

$1.0$

s and

![]() ${1.8}\,\textrm {s}$

, corresponding to the Stokes boundary layer thickness

${1.8}\,\textrm {s}$

, corresponding to the Stokes boundary layer thickness

![]() $\delta _S\approx 0.58{-}{0.78}\,\textrm {mm}$

, which is significantly smaller than the

$\delta _S\approx 0.58{-}{0.78}\,\textrm {mm}$

, which is significantly smaller than the

![]() ${30}\,\textrm {mm}$

spacing between the parallel plates. This ensures that the velocity profile above the bottom remains unaffected by the OFT’s upper boundary (van Overveld et al. Reference van Overveld, Breugem, Clercx and Duran-Matute2022a

). The ranges of dimensionless parameters explored near the motion threshold are listed in table 2.

${30}\,\textrm {mm}$

spacing between the parallel plates. This ensures that the velocity profile above the bottom remains unaffected by the OFT’s upper boundary (van Overveld et al. Reference van Overveld, Breugem, Clercx and Duran-Matute2022a

). The ranges of dimensionless parameters explored near the motion threshold are listed in table 2.

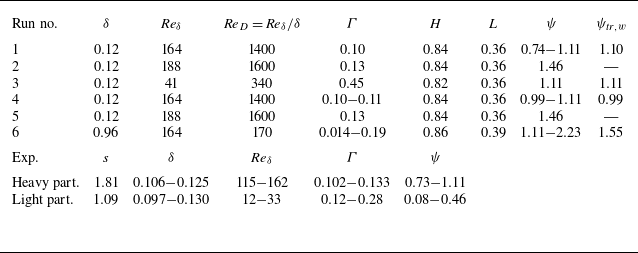

Table 2. Values of the dimensionless parameters that characterise the DNS cases, alongside experimental ranges near the motion threshold (corresponding to the symbols in figure 6). The Reynolds number based on the particle diameter is denoted by

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_D$

. The final column reports the threshold value of the mobility number

${\textit{Re}}_D$

. The final column reports the threshold value of the mobility number

![]() $\psi _{{\textit{tr}},w}$

for the onset of wiggling motion. In the DNS, the density ratio is fixed at

$\psi _{{\textit{tr}},w}$

for the onset of wiggling motion. In the DNS, the density ratio is fixed at

![]() $s=1.813$

and the value of

$s=1.813$

and the value of

![]() $\psi$

is explicitly prescribed. In the experiments,

$\psi$

is explicitly prescribed. In the experiments,

![]() $\psi$

is not an independent control parameter but follows from the other dimensionless parameters.

$\psi$

is not an independent control parameter but follows from the other dimensionless parameters.

4. Numerical approach

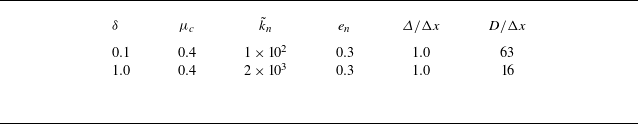

Direct numerical simulations (DNSs) are conducted to extend the experimental results and to determine the dynamics of the mobile particle during its early stages of motion. The simulations are designed to closely replicate the experiments at

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_\delta \approx 164$

, using a matching geometry with the exception that the substrate in the DNS extends across the entire horizontal bottom plane. The incompressible Navier–Stokes equations (2.2) are solved numerically using a second-order central-difference scheme to discretise the spatial derivatives and a Runge–Kutta-based fractional-step method to advance in time. At the top boundary (far above the substrate), a stress-free condition is imposed, while periodic boundary conditions are applied in both horizontal directions. At the bottom of the numerical domain, i.e. on the plane supporting the fixed bed, a no-slip/no-penetration condition is enforced. The no-slip/no-penetration boundary conditions at the fluid–solid interfaces of both the fixed and mobile particles are enforced using an immersed boundary method (IBM) developed for particulate flows by Uhlmann (Reference Uhlmann2005). This method employs a direct forcing approach, adding a localised volume force term to the momentum equations. The additional forcing term is explicitly computed at each time step as a function of the particle position and velocity, providing the stress distribution at each particle’s surface. The dynamics of the mobile particle are determined by Newton’s second law for its translation and by Euler’s second law for its rigid-body rotation, according to (2.5) and (2.8), respectively. The hydrodynamic forces and torques result from the zeroth and first angular moments of the stresses, respectively, integrated over the particle surface. The contribution of inter-particle contacts is given by the sum of the contact forces between a considered particle and its neighbours, computed using a discrete element method (DEM) similar to that proposed by Kidanemariam & Uhlmann (Reference Kidanemariam and Uhlmann2014). The present approach, which is described in Appendix B, accounts for inter-particle static friction, simultaneously incorporating elastic, inelastic and frictional contributions to the tangential force at each contact point. Correct evaluation of the inter-particle contact force is necessary for describing the early stages of particle motion because the mobile particle may either roll or slide. Tables 2 and 3 show the values of the parameters characterising the flow conditions and the computational domain, respectively. The density ratio is fixed at

${\textit{Re}}_\delta \approx 164$

, using a matching geometry with the exception that the substrate in the DNS extends across the entire horizontal bottom plane. The incompressible Navier–Stokes equations (2.2) are solved numerically using a second-order central-difference scheme to discretise the spatial derivatives and a Runge–Kutta-based fractional-step method to advance in time. At the top boundary (far above the substrate), a stress-free condition is imposed, while periodic boundary conditions are applied in both horizontal directions. At the bottom of the numerical domain, i.e. on the plane supporting the fixed bed, a no-slip/no-penetration condition is enforced. The no-slip/no-penetration boundary conditions at the fluid–solid interfaces of both the fixed and mobile particles are enforced using an immersed boundary method (IBM) developed for particulate flows by Uhlmann (Reference Uhlmann2005). This method employs a direct forcing approach, adding a localised volume force term to the momentum equations. The additional forcing term is explicitly computed at each time step as a function of the particle position and velocity, providing the stress distribution at each particle’s surface. The dynamics of the mobile particle are determined by Newton’s second law for its translation and by Euler’s second law for its rigid-body rotation, according to (2.5) and (2.8), respectively. The hydrodynamic forces and torques result from the zeroth and first angular moments of the stresses, respectively, integrated over the particle surface. The contribution of inter-particle contacts is given by the sum of the contact forces between a considered particle and its neighbours, computed using a discrete element method (DEM) similar to that proposed by Kidanemariam & Uhlmann (Reference Kidanemariam and Uhlmann2014). The present approach, which is described in Appendix B, accounts for inter-particle static friction, simultaneously incorporating elastic, inelastic and frictional contributions to the tangential force at each contact point. Correct evaluation of the inter-particle contact force is necessary for describing the early stages of particle motion because the mobile particle may either roll or slide. Tables 2 and 3 show the values of the parameters characterising the flow conditions and the computational domain, respectively. The density ratio is fixed at

![]() $s=1.813$

in all simulations, matching experiments with heavier particles. The lighter particles, with density ratios closer to unity, could not be accurately simulated due to stability limitations of the numerical approach.

$s=1.813$

in all simulations, matching experiments with heavier particles. The lighter particles, with density ratios closer to unity, could not be accurately simulated due to stability limitations of the numerical approach.

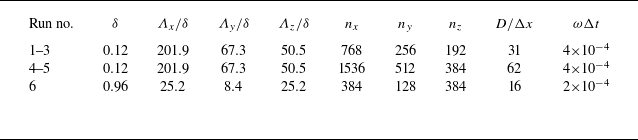

Table 3. Simulation domain parameters, where

![]() $\varLambda$

represents the size of the computational domain, while

$\varLambda$

represents the size of the computational domain, while

![]() $n$