Impact statement

Mental health disorders remain one of the leading causes of disability and impairment worldwide, particularly in post-conflict settings, where one in five people suffers from a mental health disorder at any point in time. This is particularly evident in Sierra Leone, where youth exposed to war violence have demonstrated higher levels of mental health problems, but access to mental health care remains limited. The present analysis examines the Youth Readiness Intervention (YRI), which is a trans-diagnostic, evidence-based group mental health intervention comprising 12 modules delivered by nonspecialists, for war-affected youth. The Entrepreneurship Promotion Program (ENTR), developed by a German Development Agency, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, and the Sierra Leone Ministry of Youth, combined with the YRI, provides business skills and knowledge over 15 sessions, tailored for rural youth with limited literacy. This analysis aims to quantify the return on investment (ROI) of the YRI and ENTR, using an ROI framework to capture economic benefits, including productivity (employment), healthcare savings and economic returns to the local community. Results show that the YRI + ENTR has a higher implementation cost compared to implementing the ENTR alone. Both programs (compared to the control) have a positive ROI, ranging from $1.01 to $1.95 for the YRI + ENTR and $2.53 to $6.92 for the ENTR alone. In one of the ROI pathways – that is, healthcare savings – we find that the YRI + ENTR results in an 8.5-fold larger healthcare savings compared to the ENTR alone. Using sensitivity analysis to simulate a reduction in implementation costs for the YRI + ENTR through government subsidized programs increases the ROI to between $1.32 and $2.54. Our findings are important for mental health researchers, the Sierra Leone government, development actors and policymakers seeking to utilize or expand the implementation of evidence-based mental health interventions, as they demonstrate the economic importance of investing both in livelihoods programs and evidence-based mental health interventions concurrently in war-affected settings. Findings should be used to inform future implementation of the YRI or similar evidence-based mental health programs, as beyond demonstrated programmatic effectiveness, the YRI, implemented alongside the ENTR, results in broad economic benefits and returns to society.

Introduction

Mental health disorders remain one of the leading causes of disability and impairment worldwide (GBD, 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators 2022). In post-conflict settings, one in five persons suffers from a mental health disorder at any point in time (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019). Most mental health disorders begin in childhood and adolescence (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Angermeyer, Anthony, de Graaf, Demyttenaere, Gasquet, De Girolamo, Gluzman, Gureje, Haro, Kawakami, Karam, Levinson, Medina Mora, Oakley Browne, Posada-Villa, Stein, Adley Tsang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee, Heeringa, Pennell, Berglund, Gruber, Petukhova, Chatterji and Üstün2007; Merikangas et al., Reference Merikangas, Nakamura and Kessler2009), and if left untreated, can be associated with several negative consequences, including reduced economic productivity (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Silva, Plagerson, Cooper, Chisholm, Das, Knapp and Patel2011).

Complicating the burden of mental health problems is a myriad of challenges for treating mental health disorders in low- and middle-income countries and fragile and conflict-affected regions such as Sierra Leone (Betancourt and Williams, Reference Betancourt and Williams2008; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Pinninti, Irfan, Gorczynski, Rathod, Gega and Naeem2017; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Chatterji, Evans-Lacko, Gruber, Sampson, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Borges, Bruffaerts, Bunting, de Almeida, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, He, Hinkov, Karam, Kawakami, Lee, Navarro-Mateu, Piazza, Posada-Villa, de Galvis and Kessler2017; World Bank, 2025). Sierra Leone faces numerous challenges, including a shortage of trained mental health specialists and few resource investments in mental health services by local governments (Fricchione et al., Reference Fricchione, Borba, Alem, Shibre, Carney and and Henderson2012; Keynejad et al., Reference Keynejad, Dua, Barbui and Thornicroft2018; Sierra Leone, 2021), resulting in estimates that upwards of 98% of people with mental health disorders are not receiving treatment (Yoder et al., Reference Yoder, Tol, Reis and de Jong2016; Hopwood et al., Reference Hopwood, Sevalie, Herman, Harris, Collet, Bah and Beynon2021). There are increased risk factors for child and adolescent mental health in post-conflict settings, including exposure to armed conflict, community violence, poverty and a prevalence of serious physical health concerns (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Silva, Plagerson, Cooper, Chisholm, Das, Knapp and Patel2011; Miller and Jordans, Reference Miller and Jordans2016). In Sierra Leone, which suffered a brutal civil war from 1991 to 2002, youth exposed to war violence have demonstrated greater psychosocial problems throughout their lifetimes (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Brennan, Rubin-Smith, Fitzmaurice and Gilman2010, Reference Betancourt, McBain, Newnham and Brennan2013). Several initiatives to combat these challenges have arisen over the past two decades, due to increased awareness at both the national and international level (Ager et al., Reference Ager, Horn, Bah, Wurie and Samai2025); however, local capacity remains limited.

There is growing evidence that integrating mental health interventions into alternative delivery platforms is feasible, acceptable and effective for improving the mental health of youth affected by war and adversity (Newnham et al., Reference Newnham, McBain, Hann, Akinsulure-Smith, Weisz, Lilienthal, Hansen and Betancourt2015; Bond et al., Reference Bond, Farrar, Borg, Keegan, Journeay, Hansen, Mac-Boima, Rassin and Betancourt2022; Desrosiers et al., Reference Desrosiers, Freeman, Mitra, Bond, Dal Santo, Farrar, Borg, Jambai and Betancourt2023). The Youth Readiness Intervention (YRI) was initially delivered in educational settings, and later, integrated into youth employment programs tied to regional economic development in Sierra Leone. The YRI was designed to be integrated into education or livelihoods programs in order to reach a greater scale as educational and livelihoods programs in Sierra Leone, which are relatively well-scaled, whereas community-based mental health services are not. The ability of the YRI to be integrated into novel delivery platforms, specifically youth employment, is critical as recent estimates suggest that 60% of youth are unemployed in Sierra Leone (Alemu, Reference Alemu2016), and that a large share of youth in Sierra Leone struggle with mental health problems (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Brennan, Rubin-Smith, Fitzmaurice and Gilman2010). The YRI aligns with Sierra Leone’s regional economic development goals, and this approach has proven to be an effective means of addressing both the mental health needs and economic challenges faced by male and female youth. The government’s recent policies to improve mental health for youth demonstrate a commitment to addressing these issues, even though resources have yet to be fully allocated. The potential to integrate evidence-based mental health support into existing youth employment and education programs provides a promising pathway for expanding access to care and improving the well-being of Sierra Leone’s youth.

Prior research in Sierra Leone has found YRI to be associated with improved mental health and pro-social outcomes, in addition to improved classroom behavior and school performance (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, Akinsulure-Smith, Brennan, Weisz and and Hansen2014). The results are positive as the primary goals of the YRI are to decrease anxiety and depression symptoms, and to improve emotion regulation and daily functioning (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Franchett, Kirk, Brennan, Rawlings, Wilson, Yousafzai, Wilder, Mukunzi, Mukandanga, Ukundineza, Godfrey and Sezibera2020). Further, the preliminary results of a more recent hybrid type-II trial, wherein the YRI was integrated into youth employment programs, also demonstrate that the YRI can be effectively integrated into alternative delivery platforms, such as entrepreneurship programs, and is associated with improved mental health and socioeconomic outcomes (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Farrar, Placencio-Castro, Desrosiers, Brennan, Hansen, Akinsulure-Smith, Su, Bangura and Betancourt2024). Despite the positive outcomes, when delivered in school settings, the YRI has not been found to be cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold using standard quality-adjusted life year (QALY) measures (McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Salomon, Kim and Betancourt2016), which may inhibit further expansion and funding of such programs.

Given the positive associations between the YRI when integrated into an alternate delivery platform, a youth entrepreneurship program and improved mental health and pro-social outcomes (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Farrar, Placencio-Castro, Desrosiers, Brennan, Hansen, Akinsulure-Smith, Su, Bangura and Betancourt2024), the study aims to capture the costs and broader economic impact of these benefits through a return on investment (ROI) analysis. Traditional economic evaluations often utilize cost-effectiveness methodologies (Jack et al., Reference Jack, Wagner, Petersen, Thom, Newton, Stein, Kahn, Tollman and Hofman2014; Kafali et al., Reference Kafali, Cook, Canino and Alegria2014; McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Salomon, Kim and Betancourt2016; Wilson-Barthes et al., Reference Wilson-Barthes, Chrysanthopoulou, Atwoli, Ayuku, Braitstein and Galárraga2021), which have several limitations (Raffery, Reference Raffery2001), often not considering the broader economic returns of a program (McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Salomon, Kim and Betancourt2016), such as the YRI and ENTR, and thus do not capture the full value of prevention programs. Furthermore, within cost-effectiveness evaluations of mental health interventions, while QALYs have been most often used to report on cost-effectiveness (Kinyanda et al., Reference Kinyanda, Kyohangirwe, Mpango, Tusiime, Ssebunnya, Katumba, Tenywa, Mugisha, Taasi, Sentongo, Akena, Laurence, Muhwezi, Weiss, Neuman, Greco, Knizek, Levin, Kaleebu, Araya, Ssembajjwe and Patel2021), these measures do not sufficiently capture the key intervention outcomes in most mental health interventions, and more holistic analyses may more accurately present results (McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Salomon, Kim and Betancourt2016). Additionally, for programs like YRI with demonstrated effectiveness across broad program outcomes (mental health, prosocial behavior, daily functioning and outcomes in education and livelihood programs), cost effectiveness analyses, which rely on standard cost-effectiveness measurement like QALYs, are not able to capture these full program benefits, emphasizing the need for a more holistic cost analysis to capture the array of benefits from multi-pronged programs like YRI (McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Salomon, Kim and Betancourt2016). Therefore, in this analysis, we estimate the cost of implementing the YRI and then utilize a ROI to capture broader benefits, including short- and long-run productivity, healthcare utilization reduction and cost savings and local returns to the community.

Materials and methods

YRI and ENTR intervention protocol

The YRI is a trans-diagnostic, evidence-based mental health group intervention comprising 12 group-based modules facilitated by nonspecialists (see a longer description of the study protocol by Betancourt et al. (Reference Betancourt, Hansen, Farrar, Borg, Callands, Desrosiers, Antonaccio, Williams, Bangura and Brennan2021)). The intervention is divided into three phases: connection (which promotes peer support, social engagement and community reintegration), integration (which promotes mental processing and adaptation) and stabilization (which aids in the development of emotional control and safety). The Youth FORWARD trial integrated the YRI with an Entrepreneurship Promotion Program (ENTR) of the German Development Agency, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, and the Sierra Leone Ministry of Youth using a Collaborative Team Approach. The ENTR program provided business skills and knowledge over 15 sessions (3 weeks), tailored for male and female youth in rural areas with limited literacy. The YRI was delivered before the ENTR to evaluate immediate and long-term effects. To be included in the study, male and female youth between the ages of 18–30 years old were selected based on predetermined inclusion criteria: unemployed nor engaged in school, not pregnant and elevated scores on instruments measuring emotion regulation and functioning, including the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0, n.d.) and Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (2021)). In the three districts of Koinadugu, Kono, and Kailahun, participants were designated to one of three study arms: YRI + ENTR, ENTR-only, or control. Sessions were led by a total of 12 facilitators and recorded for supervision purposes by 3 supervisors. Depending on the agreed timeline in respective communities, some modules were delivered once a week, totaling 12 sessions over 12 weeks, while others opted for twice a week, completing the 12 modules in just 6 weeks.

Data collection

Data were collected by trained research team members based at Caritas Sierra Leone (Caritas Sierra Leone, 2025). An initial data collection effort was conducted 4 years after the main trial, which included roughly 50% of the full sample. This initial follow-up collected data on key program outcomes, including mental health and employment status. The data collection process utilized a two-step stratified random sampling approach to select participants. The analysis presented below did not utilize data from this initial data collection effort.

The second data collection effort – henceforth referred to as the 2024 telephone survey – obtained data on mortality status, income, healthcare utilization and spending habits, for the remaining cohort not included in the initial data collection effort (N = 567 youth, including 198 control, 172 ENTR-only and 190 YRI + ENTR). Data for the 2024 telephone survey were collected between June and August 2024. Full data collection methodology is provided in the Methods Annex.

Costing analysis

Standard activity-based costing (ABC) methodology (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan1994) was used to guide the costing analysis to estimate the cost of the YRI and ENTR implementation, using a societal perspective (Neumann et al., Reference Neumann, Sanders, Russell, Siegel and Ganiats2016; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Neumann, Basu, Brock, Feeny, Krahn, Kuntz, Meltzer, Owens, Prosser, Salomon, Sculpher, Trikalinos, Russell, Siegel and Ganiats2016). Following the YRI and ENTR protocol described above and in Betancourt et al. (Reference Betancourt, Hansen, Farrar, Borg, Callands, Desrosiers, Antonaccio, Williams, Bangura and Brennan2021), and utilizing ABC methodology, the costs relevant to implementation were decomposed into defined activities with associated frequencies, participants and facilitators to determine the YRI and ENTR implementation total cost. Following standard ABC methodology, broad categories of cost were collected, including personnel, recurrent and capital costs (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan1994; Dunlap et al., Reference Dunlap, Kuklinski, Cowell, Bowser, Campbell, Fernances, Kemburu, Livingston, Prosser, Roa, Smart and Yilmazer2022). The research team met with in-country staff to develop and review all activities related to YRI and ENTR implementation. Based on the data provided by the in-country staff, two main cost categories were reported as part of the ABC analysis: recurrent costs and consumable costs. As there were no full-time salaried staff employed through the YRI and ENTR, staff stipend costs were included as part of recurrent costs. Recurrent costs also included the stipends given to participants. YRI + ENTR participants were given a stipend to reduce participation barriers, such as transportation and meal costs for each YRI program session. Additionally, both YRI + ENTR and ENTR participants were given a single stipend at the end of the ENTR program as a start-up fund. Opportunity costs for youth participants were estimated using Sierra Leone’s national minimum wage to account for potential wages earned if youth were working instead of participating in the intervention. Rental space, utilized to host the intervention activities, was included as part of the recurrent costs and also as a proxy for indirect costs of implementing the YRI and ENTR in community settings (U.S. Economic Development Administration, n.d.).

Lodging and travel costs were calculated using budgetary and secondary data. Budgetary data were extracted to identify stipends utilized for daily travel to implementation sites, and per diem lodging and meal stipends for facilitators and supervisors. Travel to the implementation districts was completed once at the beginning of implementation from Freetown, Sierra Leone, to each of the implementation districts and once following completion of the YRI and ENTR implementation, estimated at a 400-km round trip. Secondary data were extracted to determine the average vehicle fuel efficiency of the region (Global Fuel Economy Initiative, 2020), which was then multiplied by the distance of the trip to determine the liters of fuel required. The number of liters was then multiplied by the average per-liter fuel cost and the number of times the trip was taken to determine the total fuel cost. The total fuel cost was then divided by the number of facilitators and supervisors to determine the per-person fuel cost. This per-person fuel cost was allocated to each study arm based on the number of facilitators and supervisors in each arm. Consumable costs included all supply costs, such as printed manuals, pens, stationery, note pads, snacks and meals provided during implementation to participants.

Costs were collected from implementation data, budget reports and supplemented with national secondary data, where needed. The following cost items, as they were reported in aggregate across all implementation arms, were weighted based on the proportion of the total sample in each study arm: ENTR facilitator stipends, travel and lodging costs, rental space and consumable costs. A costing template was utilized for all cost calculations, and costs were reported in terms of total implementation costs and per-participant costs. While costs were reported in varying currencies given Sierra Leone’s currency modifications, all costs were adjusted for inflation in new Leones and converted to 2024 USD using United Nations Operational Rates of Exchange rates (23.3 Leones = 1 USD) (United Nations, 2025).

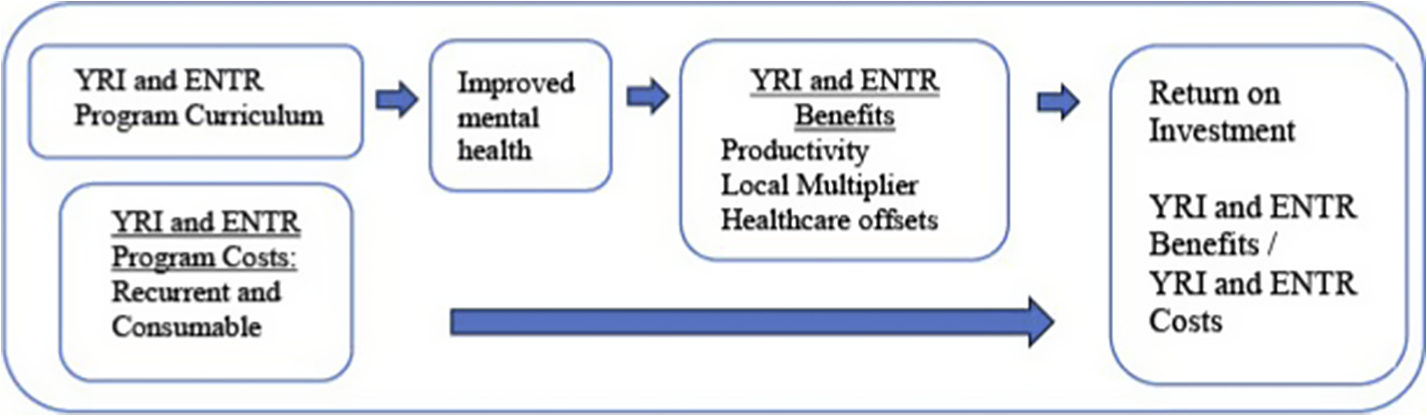

ROI analysis framework

The ROI analysis of the YRI and ENTR, using a societal perspective, can be conceptualized through the theory of change and framework (Figure 1) developed by the research team to understand how the services and resources provided during the YRI and ENTR could impact the lives of youth and the community. As shown in Figure 1, participating in the YRI and ENTR activities could result in key benefits captured through improved health and well-being, as well as mortality reduction, which can have a direct impact on productivity, returns to the local community (local multiplier) and healthcare offsets. Total benefits are compared with the total costs (recurrent and consumable costs) needed to implement the program to calculate the ROI.

Figure 1. Return on investment analysis theory of change framework.

ROI benefits

ROI benefits were calculated to capture economic returns in three ways: productivity, healthcare offsets and local multiplier. Productivity returns were calculated to estimate the economic return from employment for two time periods: lifetime earnings (net present value [NPV]) and 5 years of earnings (short-run). Both calculations utilized as inputs those who participated in the YRI and ENTR, adjusting for employment ratios and mortality. The NPV of the per-person, lifetime gross domestic product (GDP) per capita return for Sierra Leone (World Bank Open Data, n.d.-a) from 2019 to 2061 was calculated for each YRI and ENTR intervention participant, taking into consideration the age they participated in the intervention and when they would enter the workforce. GDP per capita was utilized, for this estimation, to capture an individual’s income over time, as the income reported in the telephone survey was self-reported and only captured income at a single time point. We utilized a GDP growth rate of 2.5% and a discount rate of 5% for the calculation (Sierra Leone, 2024). The 2.5% growth rate was assumed to capture future variations in growth rates for Sierra Leone. We conducted a sensitivity analysis using a GDP growth rate of 5%, with the final ROI presented in Annex Table 6. For the lifetime earning calculation, we assumed participants would enter the workforce at the age of intervention delivery and exit at 60 years old, the standard retirement age for someone from Sierra Leone. To the lifetime earning calculation, we applied the average unemployment rate, at the time of the telephone survey, for each study arm to account for unemployment variation across study arms over the lifetime. In order to capture variation in the impact on unemployment from the intervention across arms, we estimated productivity returns with a low and a high unemployment rate. The low unemployment rate was the average unemployment rate across all three arms at the time of the 2024 telephone survey. The high unemployment rate was calculated using a 1-standard deviation lower employment rate with the following standard deviations (Standard deviations of employment: YRI + ENTR = 13.32%; ENTR only = 9.06%; Control = 18.90%) to capture future variations in the employment rate.

Mortality information was captured in the productivity return by including GDP per capita returns for only the lives lived by study participants in each arm. For the 5-year calculation, we assumed participants would enter the workforce at the age of intervention delivery and exit after only 5 years (rather than a lifetime of earning), also considering unemployment and mortality over this short-run period.

To estimate the economic returns to the local community, a local economic multiplier approach was utilized to capture where individuals were spending their income and the subsequent returns to their community (Domanski and Gwosdz, Reference Domanski and Gwosdz2010; Bowser et al., Reference Bowser, Kleinau, Berchtold, Kapaon and Kasa2023). This multiplier was calculated using the percent of YRI and ENTR participants’ salaries reported to be spent in their local areas, defined as within 50 km of their residence or community. Data for the local multiplier were obtained during the 2024 telephone survey. The average percent of income spent by individuals in their local area was calculated by study arm and was then multiplied by the average self-reported income to determine the average amount returned to the community. The reported monthly income was multiplied by 12 to estimate the annual income and then used in calculating the annualized local multiplier.

The final return pathway estimated the amount of healthcare cost offsets due to YRI and ENTR participants utilizing less healthcare services or less intense healthcare services and the associated cost reductions. Healthcare utilization information, including information related to the number of healthcare visits and the type of facility visited in the last 30 days, was obtained from YRI and ENTR participants during the 2024 telephone survey to capture an overall average cost of utilizing any type of healthcare facility. Respondents were also asked to report whether the healthcare facility visited was more or less than 50 km away from their residence, and the information was used to assess indirect costs associated with the healthcare visit. Unit costs for each healthcare visit (inpatient and outpatient) were extracted from the WHO CHOICE estimates with matched bed-day costs based on the facility type respondents reported utilizing. Additional direct medical, direct nonmedical costs and travel costs were approximated using prior analyses by Phull et al. (Reference Phull, Grimes, Kamara, Wurie, Leather and Davies2021)) to reach a total direct medical, direct nonmedical and indirect healthcare visit cost. Direct medical, direct nonmedical and indirect costs were estimated by visit type (see Annex Table 1 for costs assigned) and travel distance required. Finally, additional indirect costs for missed work were estimated using participants’ self-reported income for assumed days of missed work based on visit type. For ROI calculation, healthcare offsets were annualized by multiplying the 30-day healthcare utilization savings by 12 months (Linden and Samuels, Reference Linden and Samuels2013; Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, Reynolds, Kimes, Rosales and Chan2015). This offset represented the estimated 12-month savings based on the average monthly savings from reported utilization.

ROI calculation

Lifetime earnings and short-run ROI calculations were conducted. Lifetime earning was defined as the NPV of productivity for 12 months, assuming a lifetime of earnings. The ROI for the lifetime earnings was calculated as the total benefits divided by the total costs. Total benefits included productivity, cost offsets and local multiplier in lifetime. Total costs included recurrent and consumable costs for the implementation of the YRI and ENTR.

Using benefit components (productivity, cost offsets and local multiplier), we generated per-person amounts. These per-person amounts were then differenced between study arms to estimate the returns from the YRI + ENTR compared to the control and from the ENTR-only to the control. The difference in returns was then multiplied by the total study arm population to estimate the return for all participants. This difference in return was conducted due to telephone survey limitations on half of the sample.

All of the costing methods described above were followed and were compliant with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards statement, as shown in Annex Table 8.

Sensitivity analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, using the lifetime earnings, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to estimate the ROI of YRI and ENTR implementation under reduced implementation costs. As such, the participant stipends related to the YRI were reduced to match the stipend provided in the ENTR program, assuming conditions where the Sierra Leone government subsidized this cost. All other costs were held constant. The results of this costing analysis are shown in Annex Table 2. Second, a short-run ROI was conducted, defined as the NPV of productivity assuming 5 years of employment. The short-run 5-year earnings were calculated as the total benefits over 5 years divided by the total costs. Results of the 5-year ROI are presented in Annex Table 3. Third, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to present the implementation costs in purchasing power parity, using a conversion factor of 4.79 (World Bank Open Data, n.d.-b), which is shown in Annex Table 5. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using a GDP growth rate of 5% and the resulting ROI is presented in Annex Table 6.

Results

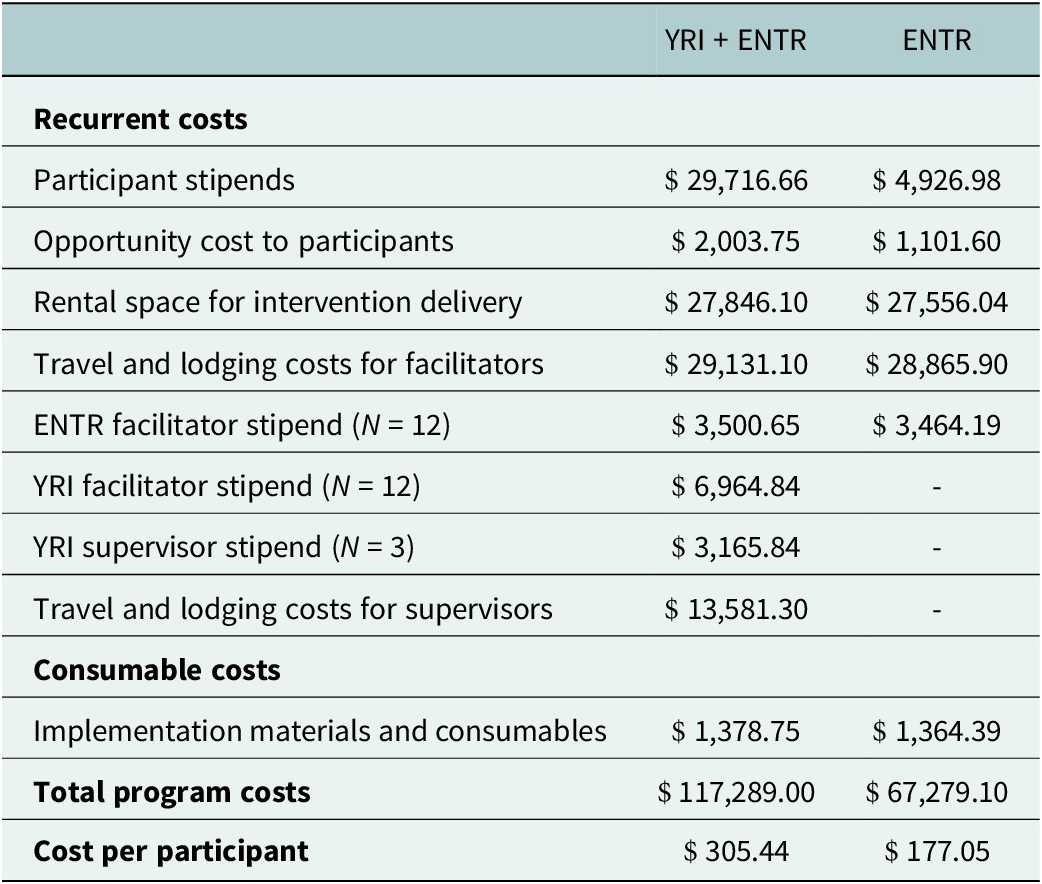

Table 1 presents the cost of implementing the YRI and the ENTR and the ENTR alone. As shown in Table 1, the total implementation cost for the YRI and ENTR is $117,289.00, and the ENTR-alone implementation is $67,279.10. The results show that the cost per participant in the YRI and ENTR group is $305.44, whereas the ENTR alone per participant cost is $177.05. The results show that, for the YRI and ENTR group participant stipends, travel costs and space rentals are the largest contributors to the total implementation cost.

Table 1. Costs of the YRI and ENTR implementation (2024 USD)

Although not shown in the main text (see Annex Table 4), characteristics of the sample at baseline show that participants have a mean age of 25 years across all study arms. Additionally, based on data collected during the 2024 telephone survey, the YRI + ENTR group has a higher monthly income compared to both the ENTR-only group and the control group ($41.19 per person per month, $36.47 per person per month and $32.65 per person per month, respectively). The unemployment rate is 1.80% in the YRI + ENTR, 0.70% in the ENTR alone and 2.68% in the control. The geographic distribution of participants is shown as well, with relatively even distribution across the three districts across study arms (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Farrar, Placencio-Castro, Desrosiers, Brennan, Hansen, Akinsulure-Smith, Su, Bangura and Betancourt2024).

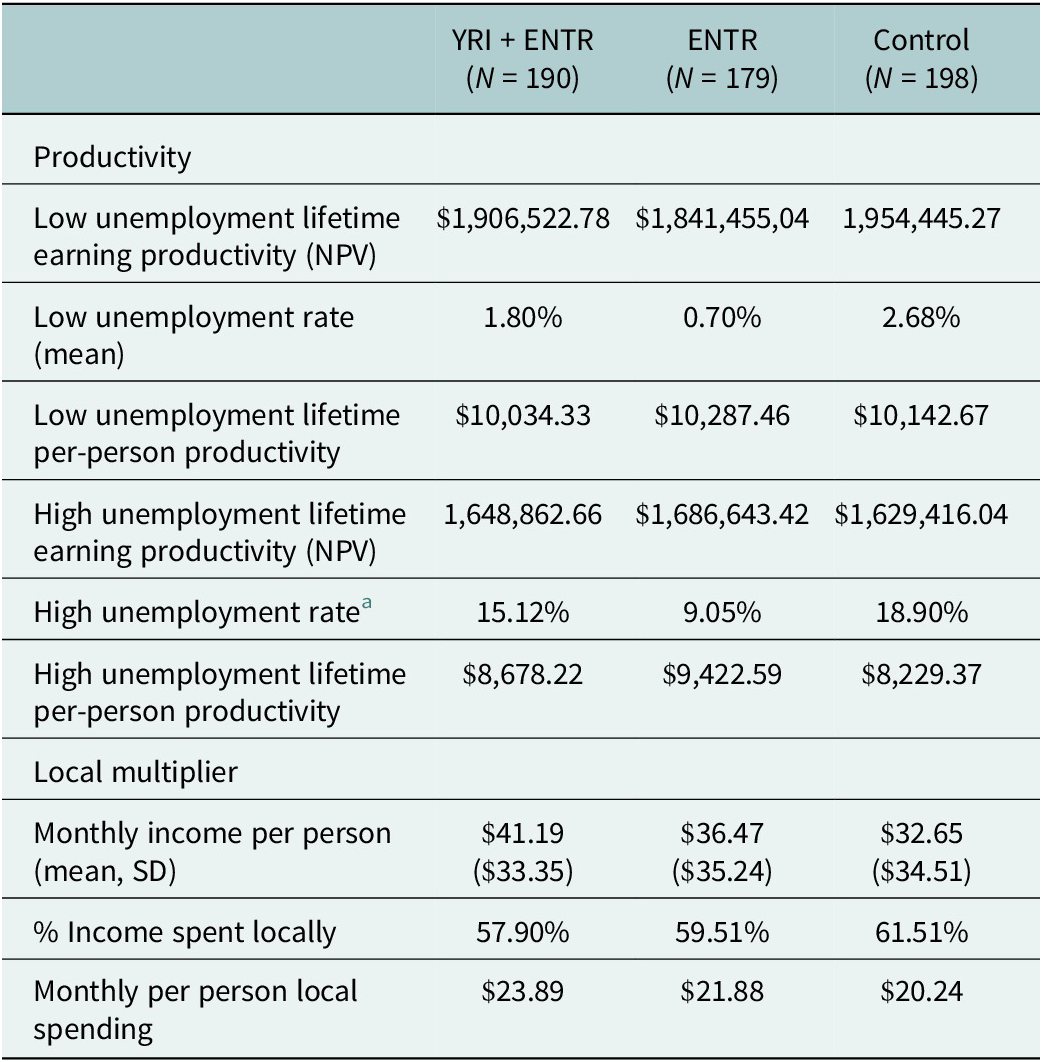

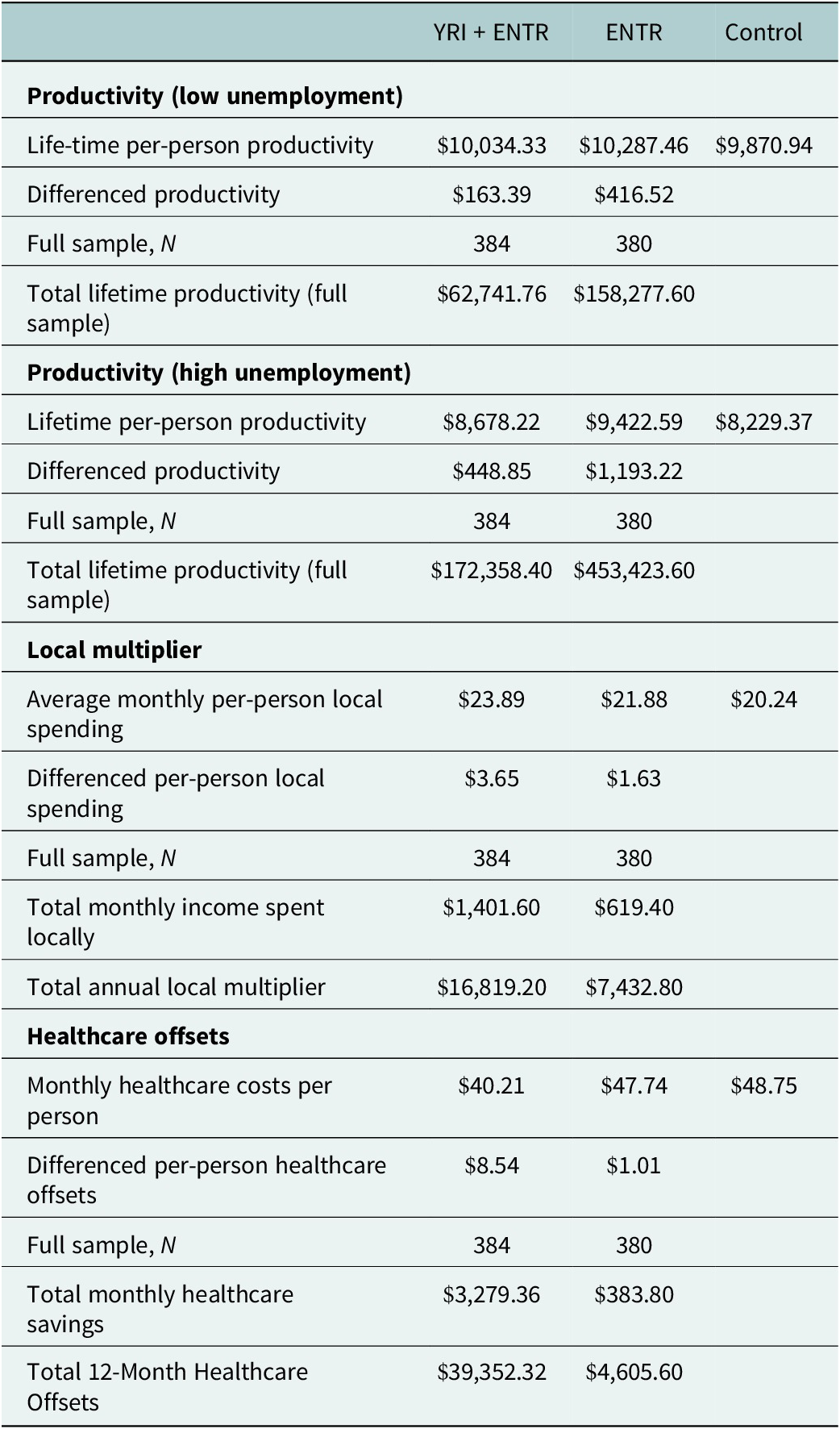

Table 2 details the long-run productivity, with low and high unemployment estimates and local multiplier calculations by study arm. Total long-run productivity, calculated as the annualized NPV of the lifetime GDP return presented as a total value and as a per capita value, both adjusted for low unemployment, is presented in the first three rows of Table 3. As shown, the long-run productivity return, assuming the low unemployment rate, is $10,034.33 per person for the YRI + ENTR group, $10,287.46 for the ENTR alone group and $10,142.67 for the control group. Average unemployment at the time of the survey (low unemployment) is highest in the control group (2.68%), followed by the YRI + ENTR (1.80%) and the ENTR alone (0.70%). Rows 4–6 of Table 2 show that under high unemployment conditions, the long-run productivity return is $8,678.22 for the YRI + ENTR, $9,422.59 for the ENTR-only group and $8,229.37 for the control. The high unemployment rates are 15.12% for the YRI + ENTR, 9.05% for the ENTR alone and 18.90% for the control. The last three rows of Table 2 show the results for the local multiplier, showing the highest economic returns to local communities in the YRI and ENTR group ($23.89 per person), followed by the ENTR-alone group ($21.88 per person) and then the control group ($20.24 per person).

Table 2. Productivity and local multiplier

Note: Standard deviation (SD).

a 1 SD of the employment rates (Standard deviations of employment: YRI + ENTR = 13.32%; ENTR only = 9.06%; Control = 18.90%) were utilized to calculate the high unemployment rates.

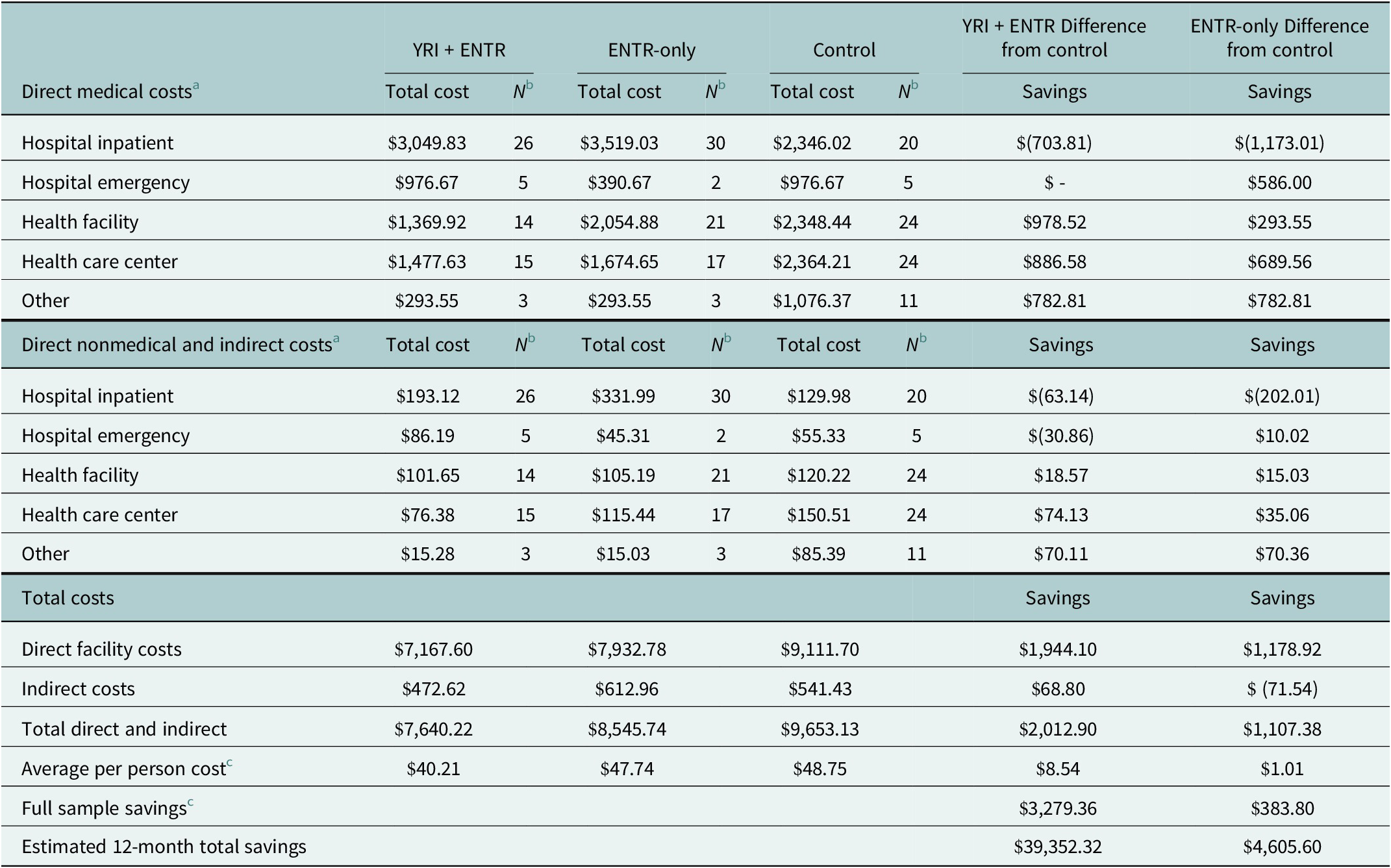

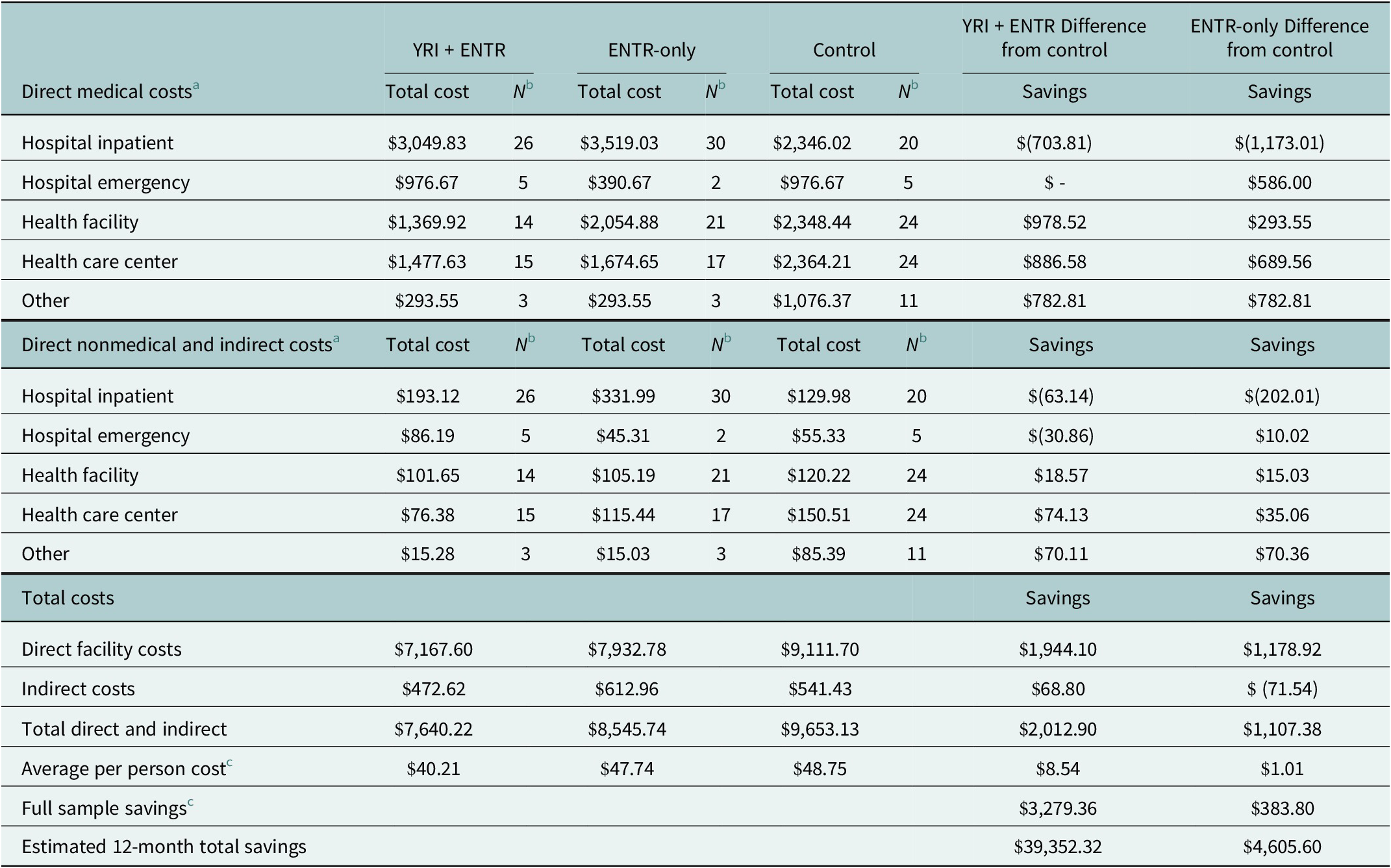

Table 3. Healthcare utilization and costs estimates, monthly and 12 months (2024 USD)

Note: Parenthesis indicate negative number.

a Direct facility costs captures the bed day, medications and medical supply costs estimated by Phull et al. (Reference Phull, Grimes, Kamara, Wurie, Leather and Davies2021). Direct nonmedical captures meal and travel costs (Phull et al. Reference Phull, Grimes, Kamara, Wurie, Leather and Davies2021) and indirect costs captures missed wages due to travel and healthcare visit time.

b N denotes the number of survey respondents who reported utilizing each respective type of care, in each study arm.

c Average per-person costs are based on N = 190 (YRI + ENTR), N = 172 (ENTR-only) and N = 198 (control). Full sample savings are based on N = 384 (YRI + ENTR), N = 380 (ENTR-only) and N = 387 (control).

Table 3 shows healthcare utilization and cost estimates for the past 30 days, including direct and indirect healthcare costs for the sample of participants surveyed. Results show total direct healthcare costs are lowest in the YRI and ENTR group ($7,167.60), compared to the ENTR alone ($7,932.30) and control group ($9,111.70). While the ENTR alone ($3,519.03) has the highest hospital inpatient costs, both the YRI + ENTR ($3,049.83) and the ENTR alone ($3,519.03) inpatient hospital costs are higher than the control ($2,346.02). The results also show that direct nonmedical and indirect healthcare costs, including travel, meals and opportunity costs, are highest in the ENTR only, followed by the control and then the YRI + ENTR groups ($612.96, $541.43 and $472.62, respectively). As such, the estimated average per-person healthcare costs for the YRI + ENTR group is lower than the ENTR-only and control groups ($40.21, $47.74 and $48.75, respectively). This results in a total estimated monthly savings for the entire sample of $3,279.92 for the YRI + ENTR compared to the control and compared to an estimated monthly savings of $384.39 for the ENTR-only group compared to the control. Estimated annual savings are $39,359.04 for the YRI + ENTR compared to the control and $4,612.71 for the ENTR-only group compared to the control. Full calculations are shown in Annex Table 7.

Table 4 utilizes the results of the long-run productivity and local multiplier (Table 2) and the healthcare offsets (Table 3) to calculate the full sample returns and cost offsets for productivity, local spending and health care offsets. The total annual productivity return, using average unemployment at the time of the survey, is $62,741.76 for the YRI + ENTR and $158,277.60 return of the ENTR-only, compared to the control. The results show that the total annual productivity return, using a high unemployment rate, is $172,358.40 for the YRI + ENTR and $453,423.60 for the ENTR-only, compared to the control. The estimated differenced total monthly healthcare savings, calculated utilizing the same steps as other returns, are found to be $3,279.36 for the YRI+ ENTR and $383.80 for the ENTR-only compared to the control. The total annual health care cost offsets for the YRI + ENTR ($39,352.32) are 8.5 times that of the ENTR alone ($4,605.60).

Table 4. Annual productivity and monthly local multiplier and healthcare offsets

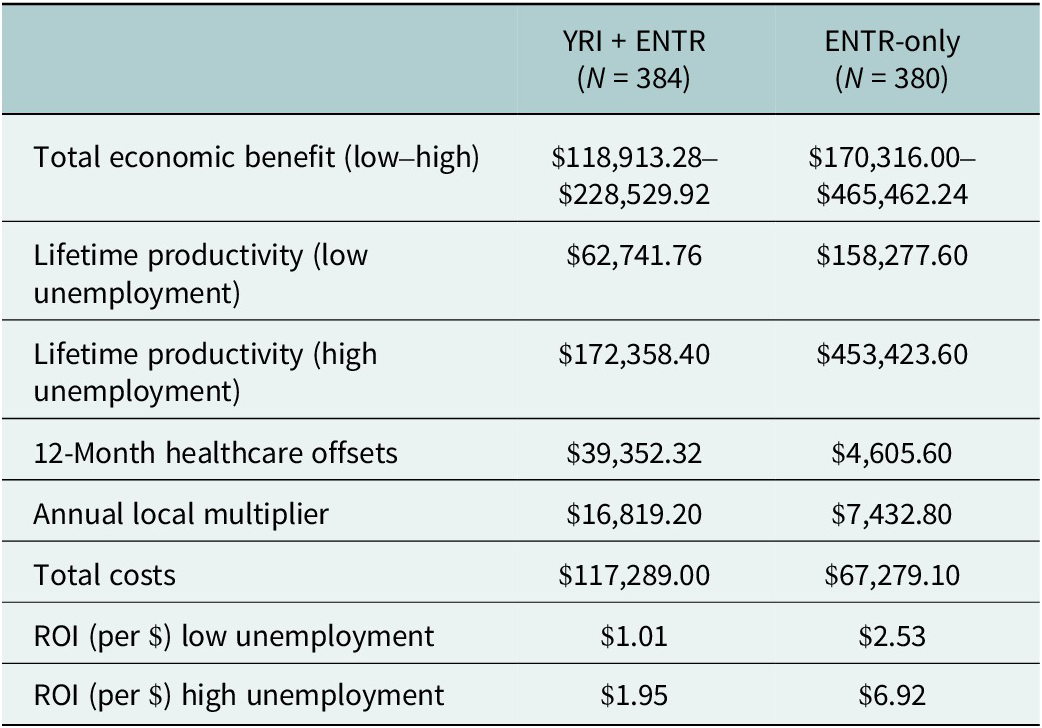

Table 5 shows the estimated annualized ROI calculated as the total economic benefits, capturing the sum of lifetime productivity (working until retirement age), annual healthcare offsets and the annual local multiplier, divided by the total implementation costs. The results show that the total economic benefit ranges from $118,913.28 to $228,529.92 for the YRI + ENTR group. The total economic benefit for the ENTR alone ranges from $170,316.00 to $465,462.24. The ROI (per $ invested) for the ENTR is higher than the YRI + ENTR ($2.53 and $1.01, respectively), driven by higher YRI + ENTR implementation costs.

Table 5. Estimated ROI of YRI and ENTR implementation (2024 USD)

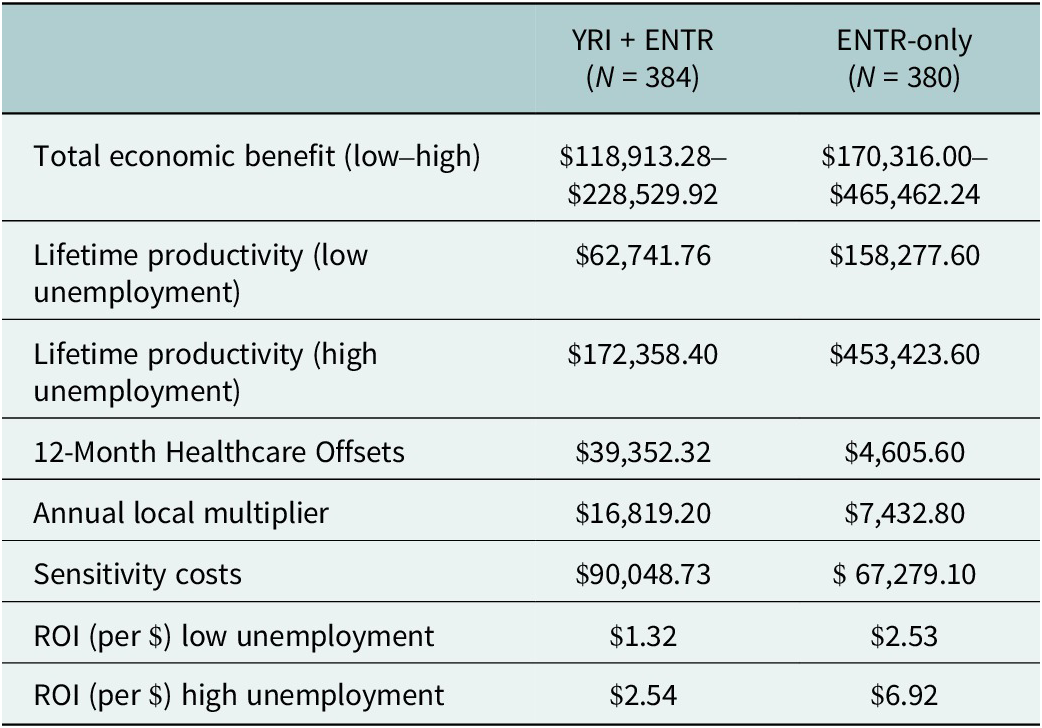

Table 6 shows the subsidized implementation where costs are reduced for implementing the YRI + ENTR, using the lifetime annualized ROI calculations. With the reduction of YRI-specific participant stipends (Annex Table 2), the YRI + ENTR total costs reduce to $90,048.73, while the ENTR costs remain constant. As such, shown below, with lower total program costs, the range for ROI for the YRI + ENTR increases to $1.32 to $2.54.

Table 6. Estimated ROI of YRI and ENTR Implementation with subsidized implementation of the YRI program (2024 USD)

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to examine the broader economic returns of the evidence-based group mental health intervention (YRI) for use in conflict-affected settings and a standard entrepreneurship program (ENTR), as well as the combination of both programs (YRI + ENTR). The analysis utilizes a comprehensive ROI framework to estimate the economic benefits of the YRI and ENTR programs and specifically captures benefits beyond those captured in a traditional cost-effectiveness analysis utilizing the QALY. This analysis builds upon prior cost-effectiveness analysis of similar programs (McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Salomon, Kim and Betancourt2016), to encapsulate economic returns in terms of productivity, cost offsets and returns to the local community. The results of this analysis are important to consider in future implementation of the YRI or similar youth mental health programs due to the broad nature of economic benefits found. Additionally, these results, paired with program outcomes, suggest that YRI implementation alongside another program, such as the ENTR, is successful in producing positive outcomes (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Farrar, Placencio-Castro, Desrosiers, Brennan, Hansen, Akinsulure-Smith, Su, Bangura and Betancourt2024) and economic returns.

While the results of the cost analysis highlight that the YRI + ENTR implementation costs are higher compared to the ENTR only implementation (305.44 USD per participant for YRI + ENTR and 107.55 USD per participant for ENTR-only), these results are likely due to longer intervention length, increased stipend costs and travel. Another study by McBain et al. finds a cost of 104 USD (2016) for YRI alone implemented in schools, which is most likely similar to the cost of the YRI program presented above if the ENTR costs are netted out and inflation is accounted for (McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Salomon, Kim and Betancourt2016), confirming the costs found in this analysis. Future implementation of the YRI may seek to lower program costs through expanding implementation or implementing the YRI alongside government-subsidized programming, as discussed below (Bond et al., Reference Bond, Farrar, Borg, Keegan, Journeay, Hansen, Mac-Boima, Rassin and Betancourt2022).

This analysis finds that both the YRI and ENTR programs result in a positive ROI. It is important to note that under the higher unemployment scenario, a larger ROI is observed for both programs, likely as a result of key programming, such as the focus of the YRI + ENTR on social-emotional skills to participants (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, Akinsulure-Smith, Brennan, Weisz and and Hansen2014; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Farrar, Placencio-Castro, Desrosiers, Brennan, Hansen, Akinsulure-Smith, Su, Bangura and Betancourt2024) and employment training provided in the ENTR program, which provides additional benefits in comparison to controls. Compared to other health interventions, the size of the ROI ($1.01 for the YRI + ENTR and $2.53 for the ENTR) is similar to other mental health interventions (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Knapp, Weng, Ndaferankhande, Stubbs, Gregoire, Chorwe-Sungani and Stewart2024; Connecticut Health Foundation, 2017; van Dongen et al., Reference van Dongen, van Berkel, Boot, Bosmans, Proper, Bongers, van der Beek, van Tulder and van Wier2016). For example, an ROI analysis for scaling screening and psychosocial treatment for women in Malawi found an initial ROI of $1.05 (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Knapp, Weng, Ndaferankhande, Stubbs, Gregoire, Chorwe-Sungani and Stewart2024). Other ROIs have utilized a social ROI (SROI) model, which captures the value of additional social benefits, including other stakeholders indirectly impacted by the intervention, resulting in a larger ROI (Kadel et al., Reference Kadel, Stielke, Ashton, Masters and Dyakova2022). Returns from mental health interventions captured through SROIs have been shown to be over $11 (Kadel et al., Reference Kadel, Stielke, Ashton, Masters and Dyakova2022). Future analyses may consider a broader social return from the YRI intervention to capture the impact on other potential stakeholders (Banke-Thomas et al., Reference Banke-Thomas, Madaj, Charles and van den Broek2015; Kadel et al., Reference Kadel, Stielke, Ashton, Masters and Dyakova2022).

Given the high implementation costs of the YRI + ENTR, the sensitivity analysis was conducted to simulate implementation under government subsidy, which assumes the participants are paid a single stipend following program completion, rather than a stipend for every session. As such, the reduced YRI program costs would result in a greater total economic return and a higher ROI for the YRI + ENTR. Subsidized programs may allow for greater efficiency of programming, which can lead to broader implementation and increased enrollment, extending program benefits and economic returns. However, further research is needed to understand the feasibility of a large-scale government-supported intervention and the potential barriers, such as funding, to ensure that program benefits, such as improved mental health and functioning, are maintained. Additionally, while preliminary long-term participant follow-up suggests that mental health benefits are sustained, further study is required to understand if economic benefits, such as employment and income, are also sustained. These findings are important for researchers and government stakeholders, as large-scale implementation feasibility and outcomes should be tested.

One key difference in the magnitude of the returns for the YRI + ENTR and the ENTR alone is the difference in healthcare cost offsets. For the annualized results reported above, the healthcare cost offsets for the YRI + ENTR are upwards of 8.5 times higher than those of the ENTR. This is likely driven by the YRI program components’ impacts on general mental health, emotion regulation and problem-solving (Newnham et al., Reference Newnham, McBain, Hann, Akinsulure-Smith, Weisz, Lilienthal, Hansen and Betancourt2015; Desrosiers et al., Reference Desrosiers, Carrol, Ritsema, Higgins, Momoh and Betancourt2024; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Farrar, Placencio-Castro, Desrosiers, Brennan, Hansen, Akinsulure-Smith, Su, Bangura and Betancourt2024), likely leading to lower utilization of overall healthcare services. While the YRI + ENTR arm has one of the highest hospital inpatient utilization costs, this may be driven by improved knowledge of healthcare seeking, health literacy and higher disposable income or insurance, which reduces economic barriers to accessing inpatient services. This outcome may also be due to the YRI curriculum’s focus on emotion regulation, which has been shown to improve coping and development of problem-solving skills, which may assist in more effective communication (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Hansen, Farrar, Borg, Callands, Desrosiers, Antonaccio, Williams, Bangura and Brennan2021). Focusing on health care benefits from mental health programming, like those offered through the YRI program, can have significant benefits to individual health and to the health system.

Limitations

While this analysis captures broader economic benefits of the YRI and ENTR programs, there are several limitations. In terms of data collection, the 2024 telephone survey was limited to half of the participants due to funding restrictions and only collected data at one time point. These limited data are available on participants regarding updated employment status and healthcare utilization, which may result in some bias in estimates. Additionally, the employment rates captured in this analysis are a single point in time and are dependent on external factors, resulting in lower or higher unemployment rates and incomes over working life. Future analysis should incorporate additional data on employment to examine how variation over time impacts productivity. This analysis utilized GDP per capita to estimate productivity returns to overcome data limitations, which are subject to limitations (Radek and Viktar, Reference Radek and Viktar2022). Similarly, due to the limitations in the number of questions asked during the 2024 telephone survey, it was necessary to approximate healthcare costs from external sources, which may result in an underestimation of healthcare costs experienced by participants. As such, we are unable to report uncertainty measures, such as standard deviations, for these costs, as this was not reported by the secondary data source. Additionally, the self-reported healthcare utilization from the past 30 days was annualized to capture an estimated average annual usage of healthcare services for this population; however, there is likely unobserved variation in healthcare use (Linden and Samuels, Reference Linden and Samuels2013), which warrants further study. The estimation of productivity returns is based upon the use of an estimated 2.5% annual growth rate in GDP per capita; however, there is the possibility of both lower and higher growth rates in the Sierra Leone context (see Annex Table 6 for an estimation with a 5% growth rate). This analysis is also limited in its ability to test statistical differences between cost outcomes, as the study was powered to examine differences in primary YRI and ENTR program outcomes. Similarly, despite a large sample of participants, the study was not powered to examine subgroup effects, such as the program impacts and returns by gender or age. Finally, the local management costs are included as part of the facilitator and supervisor stipends and, therefore, could not be assessed as separate cost inputs.

Conclusions

The estimation of the YRI + ENTR ROI demonstrates a positive economic return utilizing a comprehensive ROI framework. This analysis highlights the need to move beyond the benefits captured in a traditional cost-effectiveness analysis. The results of this analysis also demonstrate that future YRI or similar youth mental health programs should consider alternative implementation mechanisms to reduce implementation costs, resulting in stronger programmatic economic returns.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.10069.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.10069.

Data availability statement

Data available from the corresponding author (DB) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Caritas Sierra Leone for their assistance in data collection.

Author contribution

D.B.: Analysis, writing and review. B.R.: Analysis, writing and review. K.N.: Writing and critical review. M.P.C.: Analysis, writing and review. J.F.: Writing and critical review. T.S.B.: Led study design, secured funding, critical review and finalization.

Financial support

This study was funded by the project ‘Expanding the Reach of Evidence-Based Mental Health Treatment: Diffusion and Spillover of Mental Health Benefits Among Peer Networks and Caregivers of Youth Facing Compounded Adversity in Sierra Leone’ through a grant from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Mental Health R01MH117359).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethics statement

The data collected for this analysis were approved by the Boston College Institutional Review Board under protocol number 19.153.05.

Comments

Dear Global Mental Health Editors,

Please find the attached manuscript entitled Return-on-Investment of a Mental Health Intervention for

War-affected Youth in Sierra Leone, which is under consideration for publication in Global Mental

Health.

This analysis used a comprehensive Return-on-Investment (ROI) analysis framework to quantify the

economic benefits of the Youth Readiness Intervention (YRI) implemented alongside an

entrepreneurship (ENTR) program for war-affected youth in Sierra Leone. The benefits included

productivity (employment), healthcare savings and economic returns to the local community. We first

conducted a costing analysis using standard Activity-Based Costing methodology to determine the

implementation costs associated with the YRI and ENTR programs. The total benefits were

approximated using national secondary and participant level data to estimate healthcare costs,

employment and returns to the local community. The ROI then captured the return per dollar invested

based on the sum of total benefits divided by the total costs. We additionally conduct sensitivity

analyses to estimate the ROI under conditions where implementation costs could be subsidized by

government funding.

The results show that the YRI+ENTR has a higher implementation cost compared to implementing the

ENTR alone. Both programs (compared to the control) have a positive ROI: $2.76 for the YRI+ENTR and

$3.39 for the ENTR alone. We find that the YRI+ENTR results in an 8.5-fold larger healthcare saving

compared to the ENTR alone. Using sensitivity analysis to simulate a reduction in implementation costs

for the YRI+ENTR through government subsidized programs increases the ROI to $3.60. These findings

are important for mental health researchers and policy makers for future implementation of the YRI or

similar programs as we demonstrate the broad range of economic benefits.

This paper has not been published nor submitted for publication by another journal. We confirm that all

authors made substantial contributions to the concept, design, analysis, or interpretation of data and

the drafting or revising of the manuscript, and that all authors have approved the manuscript for

submission. We declare that no authors have any competing interests.