Introduction

The study of objects of bodily adornment can offer diverse insights into the lives and cultures of those who made and wore them. Depending on the context, these objects can serve to communicate aspects of identity, ethnicity and social status, among other nuanced cultural classifications. Excavations at the Ortiz site in south-western Puerto Rico (Figure 1) in 1993 recovered five human burials, the earliest directly dated burials from the island (Pestle et al. Reference Pestle, Perez and Koski-Karell2023). All five burials were accompanied by pendants made from a lustrous black rock (LBR) that does not occur with any frequency in the site’s broader lithic assemblage. Initial examination of this LBR concluded it may be a phosphatic marine fossil material (Van Meter et al. Reference Van Meter, Pestle, Koski-Karell and Carden2022). To determine the source material and gain insight into the manufacture of these pendants, we conducted a combined programme of optical light and scanning electron microscopy, elemental analysis and thin-section petrography. The results allow us to explore the possible symbolism of these unique and intriguing objects of bodily adornment.

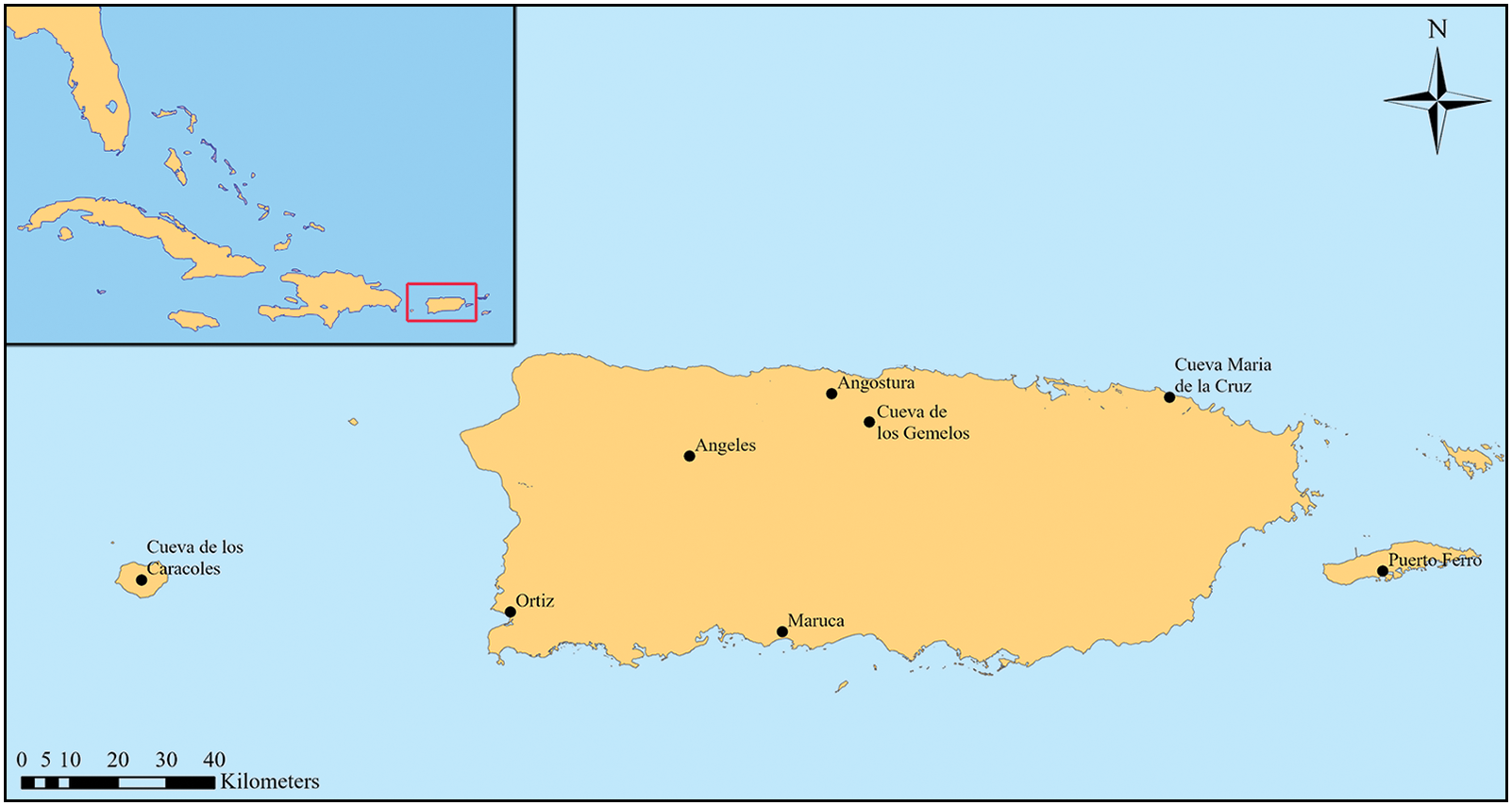

Figure 1. Map of Puerto Rico showing the location of Ortiz and other sites mentioned in the text (figure by authors).

Culture history

Three ‘ages’ are ascribed to the culture history of Puerto Rico: Archaic (c. 1000–200 BC), Ceramic (200 BC–AD 1500) and Historic (post-AD 1500) (Rouse Reference Rouse1992). As we judge the use of ‘Archaic’ to be pejorative, historically inaccurate and falsely homogenising, we prefer the use of the term ‘Early Period’ in discussing Puerto Rico’s first inhabitants (Rivera-Collazo Reference Rivera-Collazo2011; Pestle et al. Reference Pestle, Laguer-Díaz, Schneider, Carden, Sherman and Koski-Karell2021, Reference Pestle, Perez and Koski-Karell2023). Modelling of the available radiocarbon dates for this earliest period (n = 86) indicates that humans were present on the island of Puerto Rico from at least 4300–4050 cal BC, and that cultural manifestations associated with the Early Period (e.g. flaked lithics, edge-grinders, extended burials with ochre, and a general lack of pottery) lasted until between cal AD 130 and 430 (Rodríguez Ramos et al. Reference Rodríguez Ramos, Rodríguez López and Pestle2023). While the Early Period was the longest lasting of Puerto Rico’s three ages, it remains the least well-understood.

In Puerto Rico, most sites associated with this earliest occupation phase are either small (<500m2) shell middens located near present-day coastlines (Lundberg Reference Lundberg, Ayubi and Haviser1991; Rouse Reference Rouse1992) or workshops located near sources of high-quality lithic raw materials, like chert (Pantel Reference Pantel and Bullen1976, Reference Pantel1988, Reference Pantel, Cummins and King1991; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Questell and Rodríguez Ramos2001; Knippenberg Reference Knippenberg2006). Yet this association is often made on negative evidence alone (i.e. an absence of ceramics). A small number of more complex Early Period sites have been identified (Figure 1). These include Angostura (Ayes Suárez Reference Ayes Suárez2023), Cueva María de la Cruz (Rouse & Alegría Reference Rouse and Alegría1990), Maruca (Crespo-Torres Reference Crespo-Torres1997; Rodríguez López Reference Rodríguez López2004), Puerto Ferro (Chanlatte Baik & Narganes Storde Reference Chanlatte Baik, Narganes Storde, Cummins and King1991; Crespo Torres Reference Crespo-Torres, Jaén Esquivel, López Alonso, Márquez Morfin and Hernández E.1998) and the Ortiz site (Pestle et al. Reference Pestle, Laguer-Díaz, Schneider, Carden, Sherman and Koski-Karell2021, Reference Pestle, Perez and Koski-Karell2023). The larger size, spatial arrangements, mortuary practices and diversity of artefact assemblages of these sites all challenge notions of the island’s earliest inhabitants as itinerant, acephalous foragers. Moreover, the presence at some sites of ceramics (Rodríguez Ramos et al. Reference Rodríguez Ramos, Babilonia, Curet and Ulloa2008) and plant microfossils from South American domesticates (Pagán Jiménez et al. Reference Pagán Jiménez, Rodríguez López, Chanlatte Baik and Narganes Storde2005) further undermines prior assumptions about Early Period lifeways.

Regional setting

South-western Puerto Rico is the location of an abundance of archaeological sites belonging to the earliest period of the island’s inhabitation. Site files held by the State Historic Preservation Office/Oficina Estatal de Conservación Historica (SHPO/OECH) and Consejo de Arqueología Terrestre/Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña (ICP) indicate that more than 60 per cent of the documented sites in the region are associated with these early inhabitants. This is a notable and unexplained departure from the temporal pattern observed elsewhere on the island, where early sites are outnumbered by later, Ceramic Age manifestations.

The Ortiz site (ICP-CAT-CR-88-03-02) is in the municipio of Cabo Rojo (18°1′48″N, 67°10′12″W) in the island’s south-west corner. The site was initially explored in the 1980s in advance of planned development (Ortiz Sepúlveda et al. Reference Ortiz Sepúlveda, Irizarry and Ortiz1987, Reference Ortiz Sepúlveda, Irizarry, Anderson and Ortiz1988), and further site delimitation and excavation were conducted in 1993 by a commercial team led by Daniel Koski-Karell. The 1993 excavations revealed a roughly 500m2 site that included a 0.3–0.4m-deep midden consisting of abundant marine invertebrate remains (Pestle et al. Reference Pestle, Laguer-Díaz, Schneider, Carden, Sherman and Koski-Karell2021), lithic artefacts representing all stages of stone tool manufacture (Sabo et al. Reference Sabo, Koski-Karell and Pestle2023) and lesser quantities of vertebrate fauna, coral and other artefacts.

Five human burials were also uncovered (Pestle et al. Reference Pestle, Perez and Koski-Karell2023). These include one older adult (45+ years) probable female (Burial 1), an adult of indeterminate sex (Burial 2), two middle-adult (25–45 years) probable males (Burials 3 and 4) and a young-adult (17–24 years) probable male (Burial 5). Strontium isotope analysis suggests a local origin for all five individuals, while stable isotope-based dietary reconstruction suggests higher C4/CAM carbohydrate and marine protein consumption than seen elsewhere on the island in the Early or Ceramic periods (Pestle et al. Reference Pestle, Perez and Koski-Karell2023).

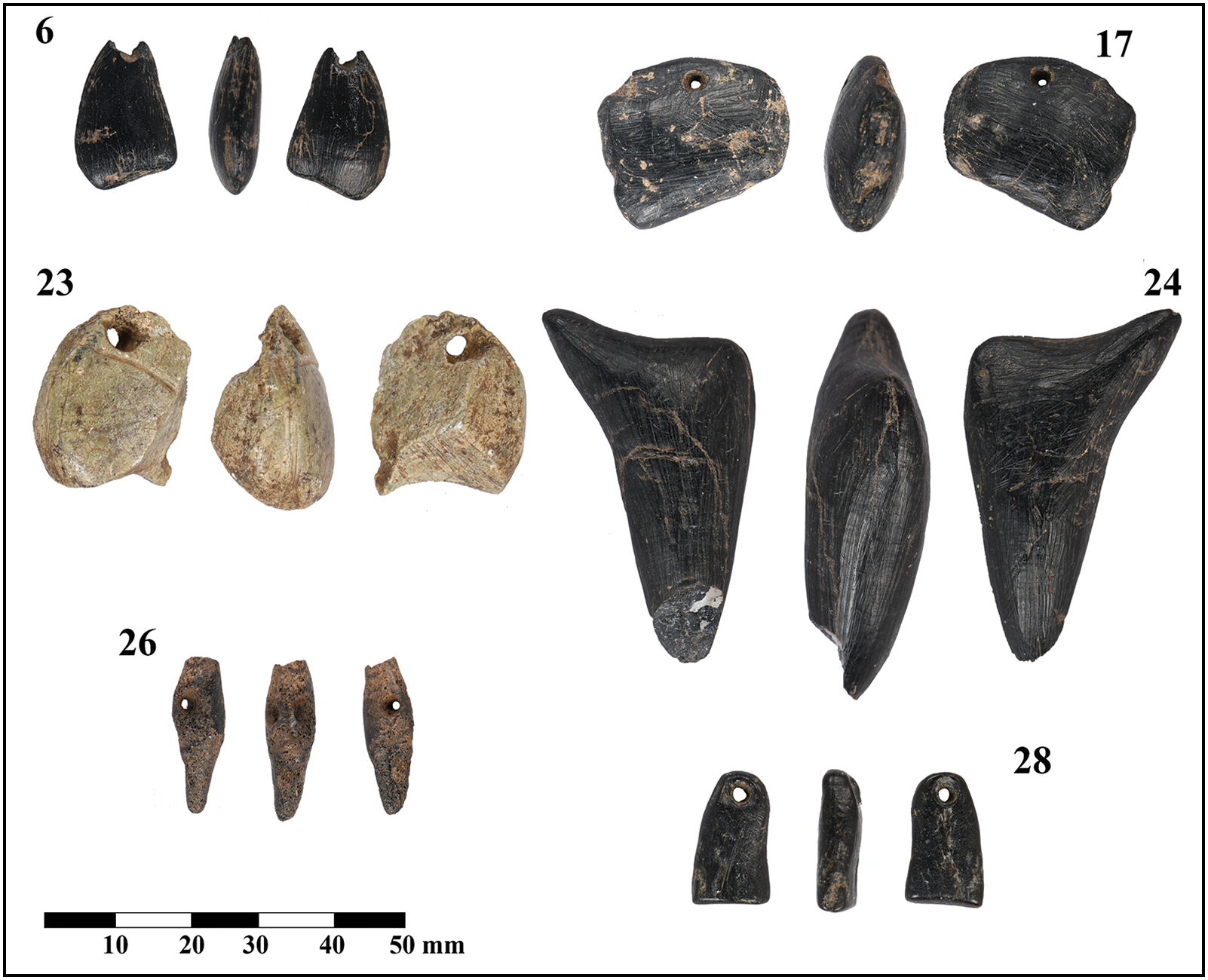

Nine radiocarbon dates from the Ortiz site provide an overall temporal range of 2300 cal BC–cal AD 240, with the directly dated burials spanning a period as long as 1880–800 cal BC, making the Ortiz burials the oldest directly dated human burials from the island (see Table 1). Based on site location, copious subsistence remains, the variety of recovered lithic artefacts and the presence of human burials, we have previously hypothesised (Pestle et al. Reference Pestle, Perez and Koski-Karell2023) that the Ortiz site was a continuously or recurrently occupied habitation site of the Early Period, with canonical mortuary treatments (consistent alignment, proximity, and depth of the burials, positioning of the body, provisioning of grave goods), and thus a shared community identity, that persisted for a millennium.

Table 1. Radiocarbon dates (n = 9) for the Ortiz site.

* Denotes calibration of recently obtained bone collagen using the method detailed in Pestle et al. (Reference Pestle, Perez and Koski-Karell2023).

The meaning(s) of adornment

Objects of adornment are defined here as items that are worn or displayed on the body, including clothing, jewellery, beads, pendants and accessories. When studied within their specific cultural contexts, objects of adornment can be powerful tools for investigating the construction and communication of social identity (Mattson Reference Mattson2021).

Understandings of objects of adornment have shifted substantially over time. While earlier considerations focused almost exclusively on adornments as markers of wealth or social status, contemporary understandings acknowledge that no universal meaning exists, and that objects must be studied within their specific cultural context (Joyce Reference Joyce2005; Papapetros Reference Papapetros2010; Abadía & Nowell Reference Abadía and Nowell2015; Mayer & Choyke Reference Mayer and Choyke2017; Mattson Reference Mattson2021). Additionally, as identity and personhood are now understood to be complex, fluid and negotiated phenomena, objects of adornment, when employed as an identity marker, are used not only to display identity, but to construct it (Jones Reference Jones1997; Fowler Reference Fowler2004; Díaz-Andreu et al. Reference Díaz-Andreu, Lucy, Babic and Edwards2005; Joyce Reference Joyce2005; Insoll Reference Insoll2007; Amundsen-Meyer et al. Reference Amundsen-Meyer, Engel and Pickering2011; Mattson Reference Mattson2021). Because the inherent signals are so nuanced and culturally specific, the experience and meaning of adornments can and do vary (Joyce Reference Joyce2005). Within the same community, similar adornments can have diverse meanings and communicate disparate ideas (Falci et al. Reference Falci, Cuisin, Delpuech, Van Gijn and Hofman2019), and one meaning does not necessarily preclude any other (Ayes Suárez Reference Ayes Suárez1992).

Put simply, the study of objects of adornment has the potential to reveal information beyond the social and economic status of their wearers. With modern technologies, researchers can uncover more detailed biographies of these objects, which intertwine with the biographies, beliefs and lifeways of the ancient peoples who wore them and, in turn, of the communities to which they belonged (Mayer & Choyke Reference Mayer and Choyke2017). For instance, culturally identifiable objects of adornment can track communities, connections and movement across Europe (Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren and d’Errico2006), and garment styles in the Andes are potent indicators of ethnicity and shared ideologies/cosmologies (Rodman Reference Rodman1992; Cassman Reference Cassman2000). In both examples, close analysis of the objects of adornment within their respective cultural contexts yielded far more comprehensive understandings of the societies that made and used them. While considering objects of adornment in this deeper manner opens new lines of inquiry, the approach also has stark limitations: when very few objects of adornment are found, or when very little is known about the culture that made or used them, we can only hypothesise as to their meaning (Mattson Reference Mattson2021).

In Puerto Rico, objects of adornment and their source materials are being used to rethink perceived island boundaries (Rodríguez Ramos Reference Rodríguez Ramos2007). One example is a class of spirally decorated pendant known as bobitos that have been found in several locations across Puerto Rico. On Mona Island, one such pendant is made of basalt, which is not found on that island. This bobito, or the stone from which it was made, must have been imported from the main island of Puerto Rico, illustrating patterns of movement of ideas, goods and people among and between Puerto Rico and neighbouring islands (Ayes Suárez Reference Ayes Suárez1992; Rodríguez Ramos Reference Rodríguez Ramos2007). This movement, and its pattern of concomitant social and cultural connections, is one example of a host of studies focused on the movement and cultural significance of various raw materials and objects of adornment during the Caribbean Ceramic Age (e.g. Knippenberg Reference Knippenberg2006; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Bright, Boomert and Knippenberg2007; Queffelec Reference Queffelec2023). Such work emphasises the frequency and intensity of far-flung networks of exchange in these media, the circulation of ideas that drove and accompanied them, and the existence of a shared cultural identity that they fomented (Bérard Reference Bérard, Keegan, Hofman and Rodríguez Ramos2013). The present work seeks to examine the meaning of ornamentation in the preceding Early Period, and to consider what the presence, or indeed the absence, of long-distance movement of such objects or their raw material antecedents may have signified.

Comparanda

Objects of adornment have been found in excavations at several early Puerto Rican sites (Figure 1), although some details are contested due to inconsistencies in archaeological documentation. Such artefacts fall into two broad categories, beads and pendants, which are distinguished by the placement of perforations: beads are centrally perforated, while pendants are “perforated at one or both ends rather than symmetrically through the middle” (Mayer & Choyke Reference Mayer and Choyke2017: 1). Stone beads are found at the sites of Angostura (Barceloneta municipality), Cueva los Gemelos (Morovis) and Puerto Ferro on the island of Vieques, marine shell beads at Maruca (Ponce municipality) and beads of marine fish bone at Angostura (Chanlatte Baik & Narganes Storde Reference Chanlatte Baik, Narganes Storde, Cummins and King1991; Ayes Suárez Reference Ayes Suárez1992, Reference Ayes Suárez2023; Rodríguez Ramos Reference Rodríguez Ramos2007). Pendants, typically made of stone, are found at sites including Angostura, Angeles (Utuado) and Cueva de los Caracoles on Mona Island (Ayes Suárez Reference Ayes Suárez1992, Reference Ayes Suárez2023; Rodríguez Ramos Reference Rodríguez Ramos2007). Two stone pendants from Angostura (one from a mortuary context) seem to be made from serpentinite (Ayes Suárez Reference Ayes Suárez2023: 171), a rock that only occurs in the south-western corner of Puerto Rico.

Materials and methods

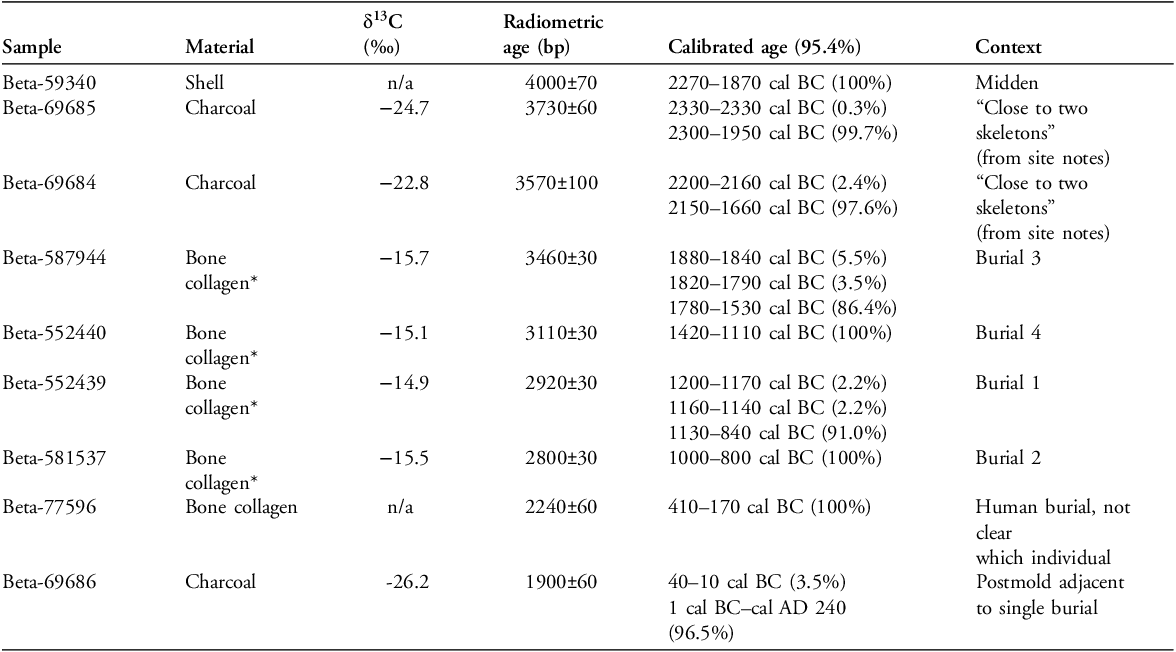

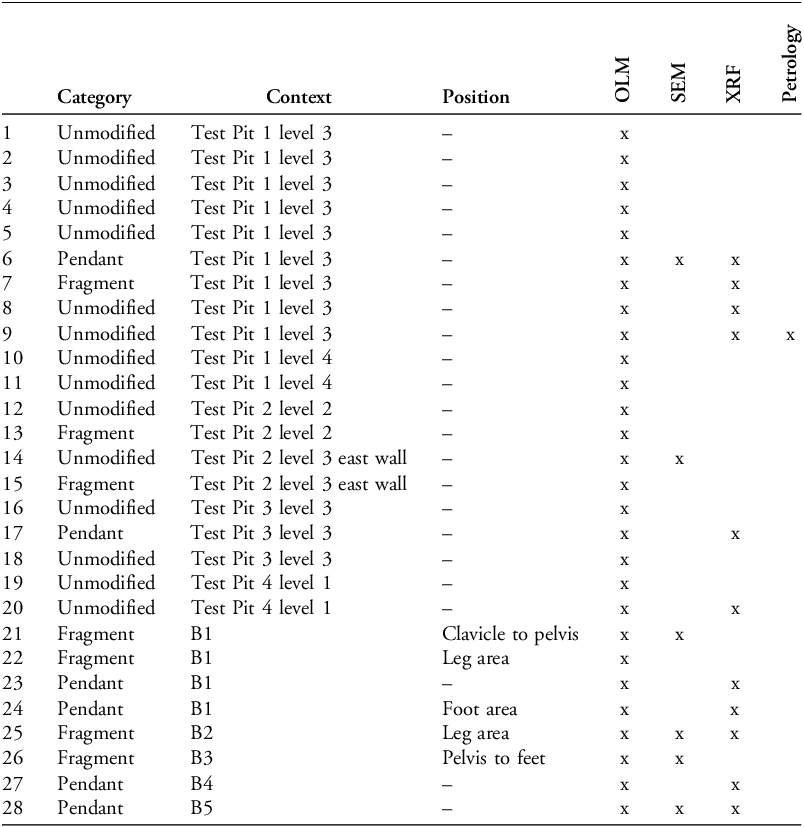

Twenty-eight artefacts from the Ortiz excavation were designated as ‘amulets’ by the excavators. Of these, we classified six as pendants (Figure 2), seven as pendant fragments and 15 as unmodified rocks of the same source material as the pendants (Table 2). Our classification was based on the presence or absence of signs of modification, including striations (bunched parallel grooves), perforations (holes made via piercing or drilling) and incisions (isolated grooves) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Six complete or nearly complete pendants from Ortiz (figure by authors).

Table 2. Details of 28 artefacts identified by excavators as ‘amulets’.

Position in regards to the body is given (when available) and the analyses performed for each artefact are indicated.

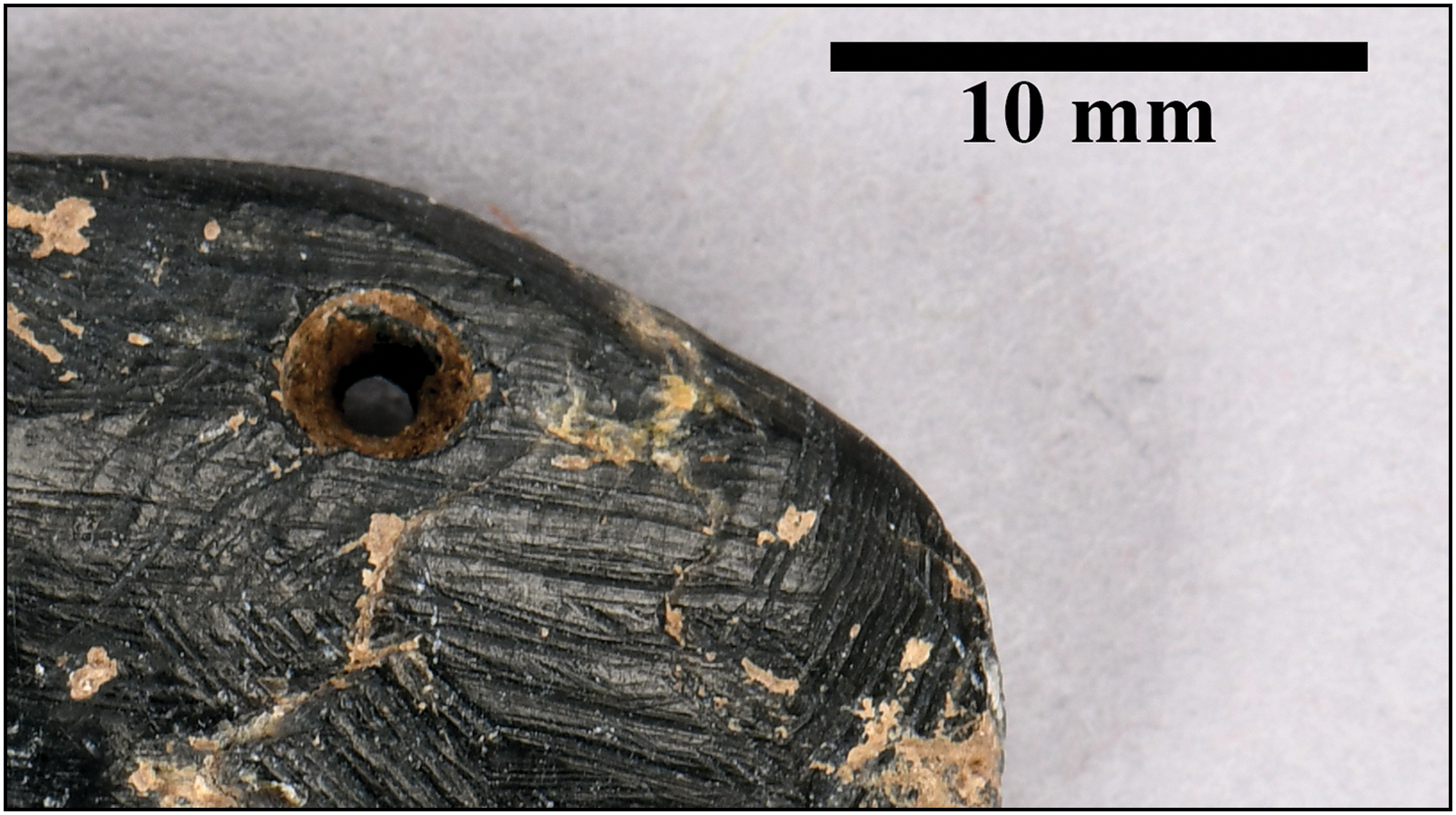

Figure 3. Optical light micrograph of artefact no. 17 showing striations and biconical perforation (figure by authors).

Five of the six complete/nearly complete pendants possess rounded margins; the intensity of the striations and the lustre of the surfaces serve as a testament to the amount of labour invested in shaping the ornaments. Artefact no. 26 appears to be the perforated tooth of an animal (likely dog, but could be marine mammal), while no. 24 takes the form of a (fossilised) shark tooth, albeit lacking one lateral portion of its base/root. Based on their shape, artefact nos. 6 and 28 might also be classified as teeth or facsimiles thereof. Artefact no. 17, however, does not conform to this pattern, and no. 23 is ambiguous in form due to its incompleteness, although it is the sole ornament with an obvious incision: a gently curving line that diagonally crosses its ventral surface.

Four of the six pendants (nos. 6, 17, 24 & 28) and all the pendant fragments are made of LBR; artefact no. 23 is made of a green-tan stone and artefact no. 26 was fashioned from a faunal tooth. The character of the LBR, the frequency with which it was used as the raw material for pendants, and its general paucity in the rest of the site assemblage marked it as of particular interest for further study.

At least one pendant, whole or fragmented, was found in association with each of the Ortiz burials: four with Burial 1 and one each with Burials 2–5 (see Table 2). It is possible that the other artefacts also came from mortuary contexts, as the margins of the grave cuts were not always clear during excavation, the graves having been dug into, and refilled with, the contents of the site’s shell midden.

All 13 pendants and pendant fragments were analysed using optical light microscopy (OLM), with a subset being the subject of further analysis by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), x-ray fluorescence (XRF) and petrography (see Table 2). The aims of these analyses included the characterisation and measurement of striations, incisions and perforations, the determination (if possible) of materials/tools used in pendant manufacture and the documentation of elemental composition and mineralogy. Selection of samples for all analysis beyond OLM was based on size and degree of completeness; no complete pendants were subject to destructive analysis (thin sectioning), which was performed only on unmodified rock of the type used for pendant manufacture.

OLM was performed at magnifications of 15–50× using a Leica M165C stereo microscope, incident lighting and Leica Application Suite software. SEM was undertaken at the Microstructure and Micromechanics Laboratory (Prof. Giacomo Po) at the University of Miami, using the secondary electron detector of a Zeiss Gemini Ultra Plus FESEM at 5keV acceleration voltage with no conductive coating. XRF was performed using an AVAATECH XRF core scanner in the Palaeoclimatology Lab of the Department of Marine Geosciences, University of Miami. All samples were scanned twice (10kV, 1000mA, no filter; 30kV, 1000mA, Pd filter) to acquire readings for the range of elements reported here. Petrography was performed using a Leica DM750P polarising light microscope in the Department of Marine Geosciences. A thin section made of assumed source material (artefact no. 9) was observed under 4–10× magnification and analysed using the Leica Application Suite v.3.8.

Results

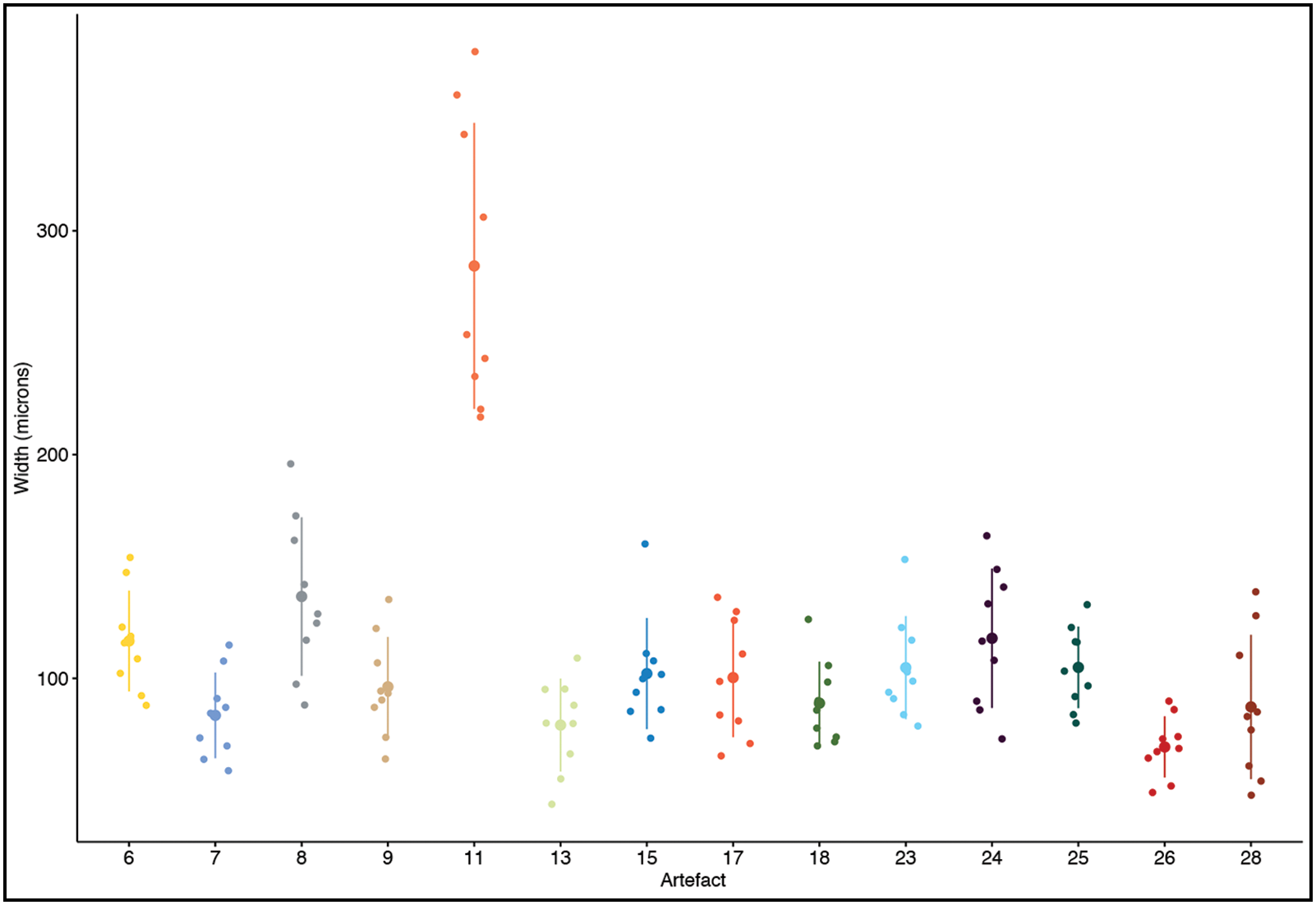

OLM analysis permitted the determination of the shape and width of striations, marks which we associate with the shaping/smoothing of the pendants. The width of these ‘U’-bottomed grooves in 12 of the pendant/pendant fragments range from 49–196μm (Figure 4). The striations of pendant fragment no. 11 are outliers, with groove widths ranging from 217–380μm. All widths are consistent with abrasion or shaping of the pendants using a fine-grained sandstone abrader (sand grains measuring 50–2000μm), although coral files (which can have grain sizes of similar or larger size) also may have been used. Analysis of the perforations indicates a biconical form (‘double cone’; Queffelec et al. 2018), likely bored using a chert drill. Chert is the raw material used most frequently at the Ortiz site for lithic production and possesses the requisite hardness and sharpness to produce the observed perforations.

Figure 4. Striation widths on different artefacts: larger dot represents mean; bar represents one standard deviation (figure by authors).

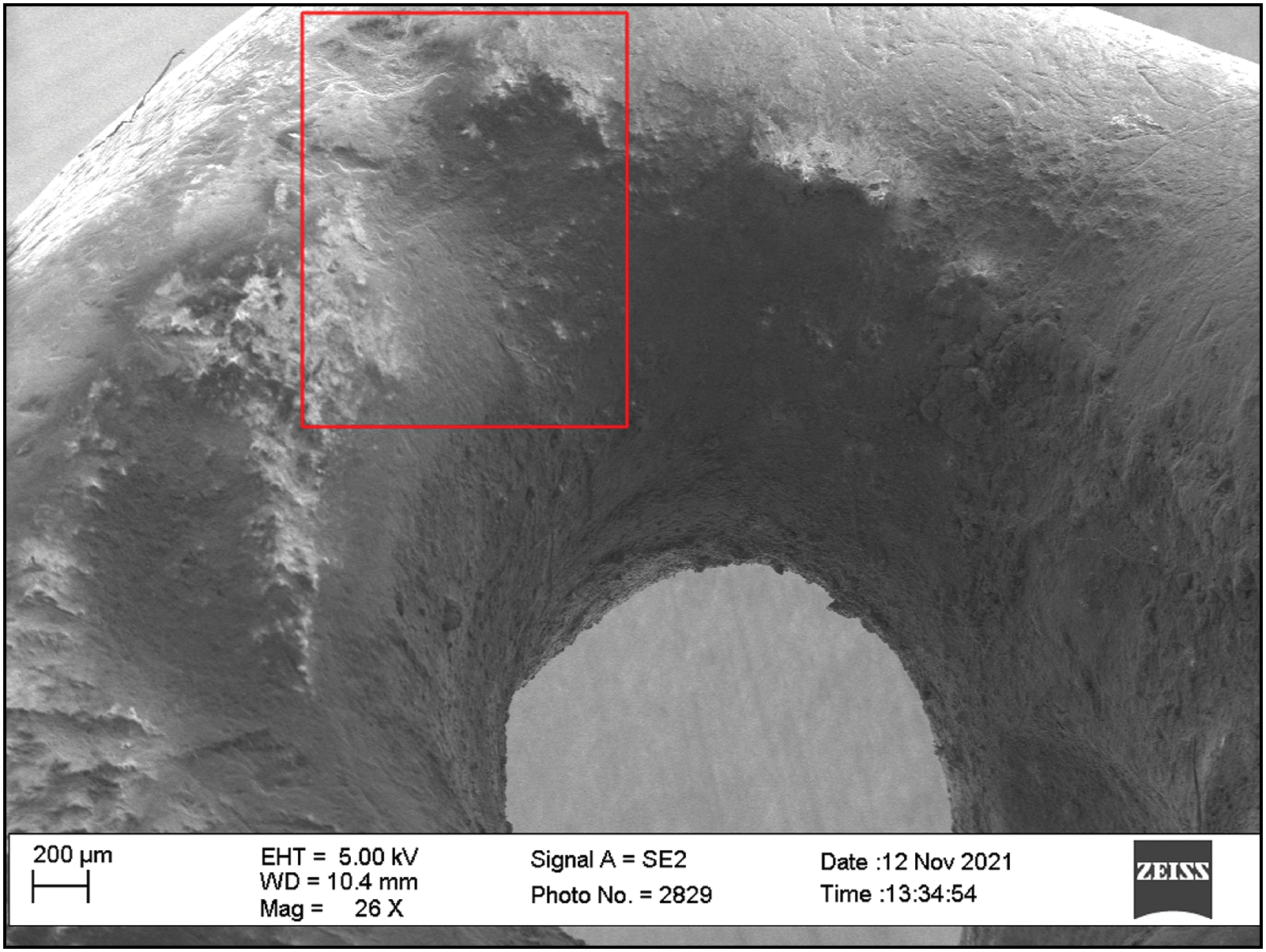

Six pendants/pendant fragments were selected for SEM to further characterise the marks associated with the process of manufacture. Striation widths measured using OLM were validated using SEM, which also confirmed that the perforations made for stringing the pendants were biconical. In the case of artefact no. 28, we were able to identify wear on the perforation associated with stringing, indicating that it had likely been worn prior to burial, identifying it as an object of adornment in life as well as death (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Scanning electron micrograph of artefact no. 28 showing biconical perforation and smoothed/worn area above perforation possibly resulting from stringing (indicated in red) (figure by authors).

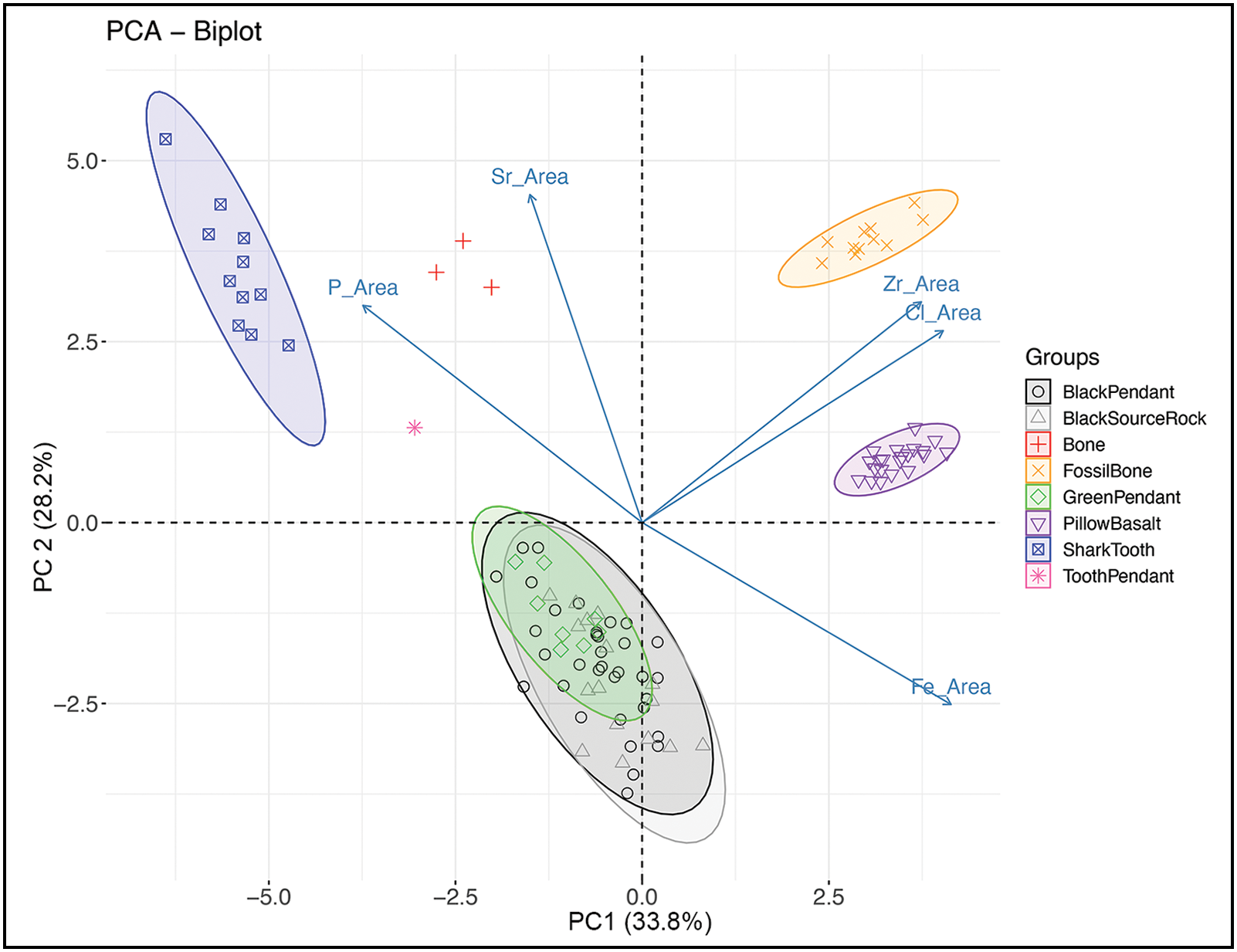

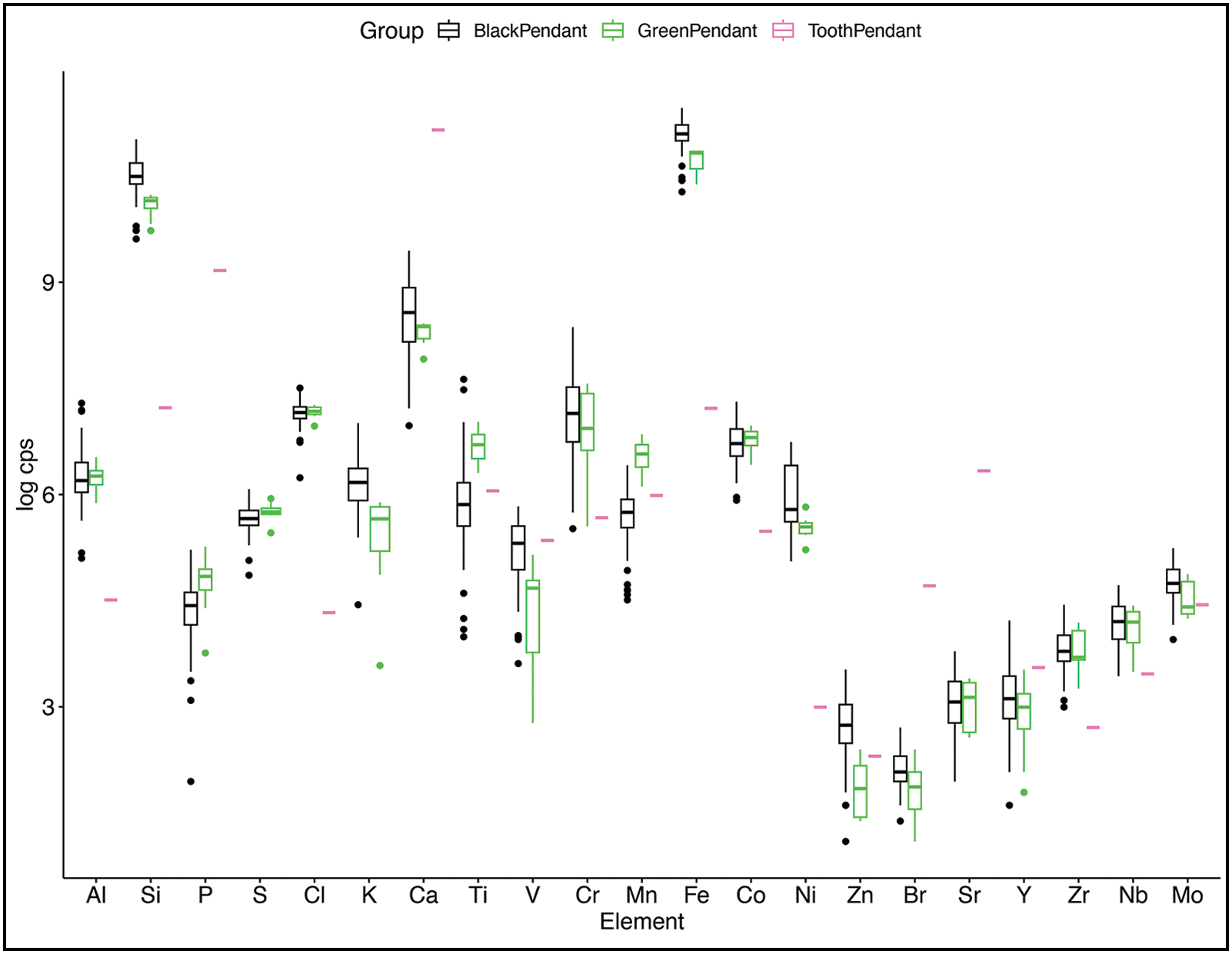

XRF of eight pendants/pendant fragments (six black, one green and one possible faunal tooth) and five possible source materials (bone, fossil bone, fossil shark tooth, pillow basalt and five samples of unmodified LBR) yielded four key results (full elemental data provided in the online supplementary material (OSM) Table S1). First, as seen in Figure 6, there are clear compositional differences among the five possible source materials, which rule out bone, fossil bone, fossil shark tooth and pillow basalt as the raw material for pendant manufacture. Second, there is marked elemental similarity of both the black and green pendants with the samples of LBR identified as a possible source material. Third, there are notable elemental similarities between the black pendants and the solitary green pendant (artefact no. 23). Fourth, the pendant identified as likely being animal tooth (artefact no. 27) is most similar in its elemental composition to bone and fossil shark tooth, perhaps indicating that it was made of a subfossil faunal tooth.

Figure 6. PCA biplot of the elemental composition (as determined by XRF) of eight pendants/pendant fragments and five possible source materials, with groupings and elements with largest contributions to component loading noted (P – phosphorus, Sr – strontium, Zr – zirconium, Cl – chlorine, Fe – iron) (figure by authors).

Narrowing the consideration to just the eight pendants/pendant fragments (Figure 7), the overall similarity in elemental composition of the black and green pendants is evident, as is the dissimilarity of artefact no. 27, the faunal-tooth pendant. The high iron (Fe) and silicon (Si) content of both the black and green pendants are consistent with serpentinite, a green-black metamorphic rock. The absence of magnesium (Mg) suggests the nearly complete alteration of peridotite, the ultramafic parent rock of serpentinite. Variation in Fe, which is responsible for serpentinite’s dark colour, may explain the overall elemental similarity of the green and black amulets while also accounting for their varied colouration. While high calcium (Ca) and chromium (Cr) content is not entirely consistent with serpentinite, the presence of these elements may be a result of late-stage calcite vein infill and of residual pyroxene, respectively.

Figure 7. Elemental composition (as determined by XRF) of eight pendant/pendant fragments, grouped by type (figure by authors).

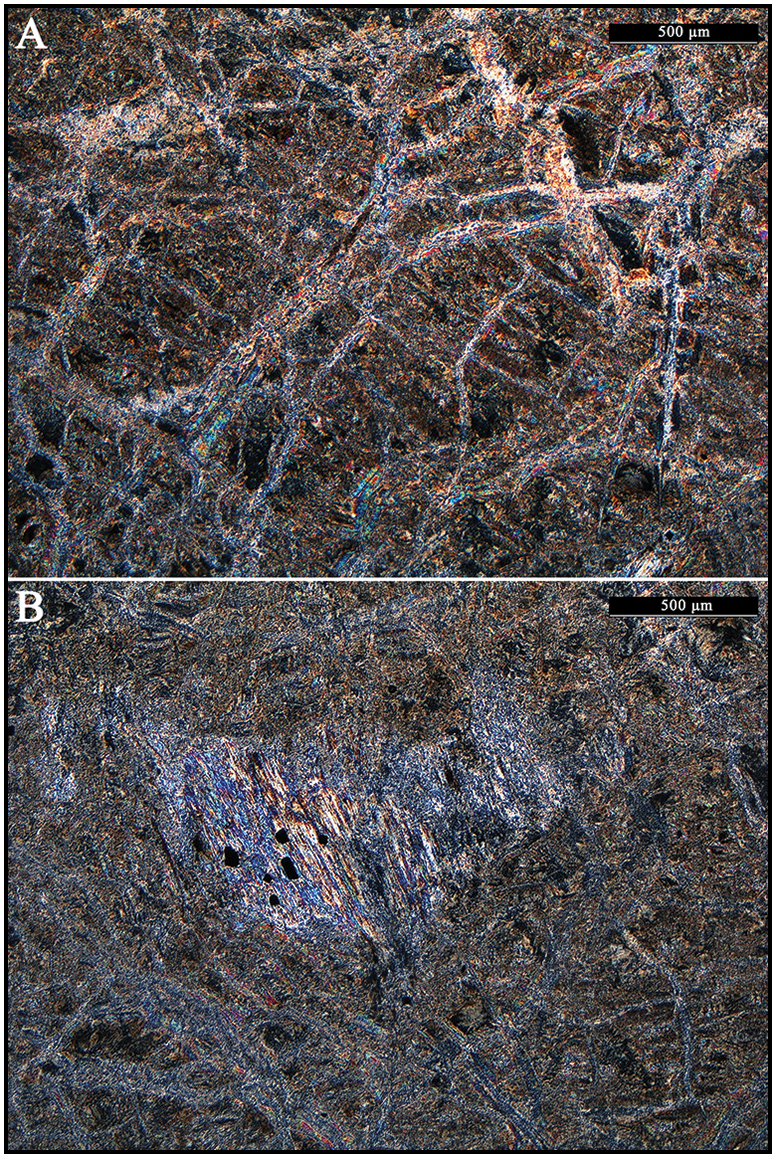

Petrographic analysis of artefact no. 9 (Figure 8) confirms the source of most of the pendants, revealing typical serpentinite mesh and bastite (orthopyroxene) textures overlaid by veining episodes (Roehrig et al. Reference Roehrig, Laó-Dávila and Wolfe2015: 198). Serpentine-group minerals are known for their low hardness (2.5–3.5 on the Mohs scale), which allows them to be carved, and the softness of the petrographic sample appears to fall within this range. There are three separate serpentinite belts in south-western Puerto Rico (the Rio Guanajibo, Monte del Estado and Sierra Bermeja formations), the only region of the island in which serpentinite occurs (Roehrig et al. Reference Roehrig, Laó-Dávila and Wolfe2015: 198). These formations also include chert, another key raw material of the Early Period, found in abundance at the Ortiz site.

Figure 8. Petrographic thin section of artefact no. 9 showing mesh with subsequent veining (A) and bastite texture (B) typical of highly metamorphosed serpentinite (figure by authors).

Discussion

All five burials excavated at the Ortiz site were found to include at least one pendant or pendant fragment. Due to the ubiquity of pendants in the burials, it is unlikely that they indicated social or economic status differences, although the fact that Burial 1 had multiple pendants could be taken to indicate some form of rank or could be connected with aspects of gender, as Burial 1 contained the only (possible) female.

Considered together, we contend that these pendants, which were worn in both life and death, would have signalled belonging to a particular social group, one which returned to the Ortiz site repeatedly, over dozens of generations. The pendants, which formed part of a standardised set of mortuary practices spanning a millennium, would not only have connected each of the five individuals to one another, but also to their immediate surroundings. While serpentinite may have been procured for its workability, the use of a material that is geologically restricted to south-western Puerto Rico (although also present along boundary zones of the Caribbean plate in the other Greater Antillean islands; Dengo Reference Dengo and Shagam1972) suggests a profound familiarity with the local environment. Evidence that at least one pendant had been worn in life only strengthens the hypothesis for the use of these objects as signalling devices of belonging and identity. Thus, we take the ubiquity of serpentinite pendants in mortuary contexts at the Ortiz site to suggest a form of inalienable wealth. Inalienable possessions are those that are excluded from exchange and a broader economic realm, finding their value instead in their persistence in the social group in which they originated (Weiner Reference Weiner1985). The deposition of such signalling devices in burials, which intrinsically removed the pendants from circulation, could “‘anchor’ a clan or a lineage to a particular locality, physically securing its identity and ancestral right” (Weiner Reference Weiner1985: 211). The anchoring function of these pendants, hewn from an exclusively local material, would have tied those buried at the Ortiz site to that place, thus lending the place significance and helping to affect the deceased’s claim to it.

These concepts of locality form a counterpoint to themes of intra- and inter-island connection and exchange often invoked in interpretations of objects of adornment in the Ceramic Age of the Caribbean (Knippenberg Reference Knippenberg2006; Queffelec Reference Queffelec2023). While the circulation of certain classes of raw material and finished adornments across the Greater and Lesser Antilles in the Ceramic Age suggests engagement in spheres of movement and exchange, and even a widely shared social vernacular and identity, in this Early Period example we find instead the construction and signalling of an identity fundamentally rooted in the local. This reading does not negate interpretations of the broad connections characteristic of the Ceramic Age, but rather points out that, at this earlier time and in this specific place, identity may have been defined in more local terms. The transformation of meaning of serpentinite as a raw material, from signifying locality in the Early Period to being a central commodity in widespread exchange and dispersed identity construction in the Ceramic Age (Bérard Reference Bérard, Keegan, Hofman and Rodríguez Ramos2013; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Mol, Rodríguez Ramos, Knippenberg, Berard and Losier2014), is a consummate example of context-based changes in meaning of objects of adornment. Indeed, the discovery of a serpentinite pendant at the north coastal site of Angostura (Ayes Suárez Reference Ayes Suárez2023), while problematising the argument about connection to place, may also speak to a distinct coeval meaning of serpentinite adornments in the Early Period.

Conclusion

While objects of adornment have been discovered at other sites in Puerto Rico, the Ortiz pendants are unique because of their early date, large number and the extended period in which they were provided as a burial accompaniment. As objects of adornment often are used “to create, contest, and transform… identities” (Mattson Reference Mattson2021: 1), we read these pendants as potent signals and symbols of belonging, both within the group of people who lived/died at Ortiz, and to its place and region. This emphasis on the local, on signalling in life and death one’s belonging to ‘here’, represents a distinct meaning for objects of adornment in the Early Period compared with the ensuing Ceramic Age. Due to the limited amount of information about both the Ortiz site and pendant use among early inhabitants of Puerto Rico, these conclusions must remain contingent and future discoveries at the Ortiz site or elsewhere in Puerto Rico could shed further light on the meaning of these unique objects of adornment. Until then, the pendants found at the Ortiz site stand as an important testament to processes of adornment and identity construction among the early inhabitants of Puerto Rico.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Consejo de Arqueología Terrestre/Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña and L. Antonio Curet. Additionally, we thank James Coakley, William Hixson and Giacomo Po (University of Miami College of Engineering). Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding statement

Portions of this research were supported by the National Institute of Archaeology, USA, and the Anthropological Research Council, USA.

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10177 and select the supplementary materials tab.