1.1 What Is Law?

Although the subject-matter of jurisprudence (sometimes called ‘legal theory’) is not understood in precisely the same way everywhere, everyone agrees that the question of the nature of law falls within the purview of jurisprudence. The central question is ‘What is law?’, or ‘What is the nature of law?’, and it is usually here that one encounters legal positivism and its main challenger, natural law theory, for the first time. The central question in the debate between legal positivists and natural law thinkers – the perennial finalists in the world cup of legal theoryFootnote 1 – is often said to concern the relation between law and (true) morality: Whereas natural law thinkers maintain that law is necessarily moral, that there is a necessary connection between law and morality, legal positivists hold instead that the relation between law and morality is contingent, that law is sometimes moral, sometimes immoral, and argue that the question of whether we have an obligation to obey the law can be answered only after we have considered the content and the administration of the law in the relevant jurisdiction.Footnote 2 However, in this introduction we shall focus on legal positivism, not the legal positivism/natural law debate, and we shall attempt to provide a fuller and more adequate characterisation of legal positivism than just saying that legal positivists reject the view that there is a necessary connection between law and morality, as well as to identify certain important types of legal positivism.

However, given the energy expended throughout history by legal philosophers and jurists on the legal positivism/natural law debate and on natural law theory and legal positivism considered separately,Footnote 3 one may wonder if yet another volume on legal positivism is needed. But although much has already been said about legal positivism, we believe that there is more to say, not only about what legal positivism is, or might be, and about different types of legal positivism but also about different geographical traditions of legal positivism, about the central figures of legal positivism, about the fundamental tenets of legal positivism, about the problem of legal normativity considered within the framework of legal positivism, about the meta-ethical underpinnings of legal positivism, if any, about the value or disvalue of law positivistically conceived and of positivistic legal arrangements and, of course, about the perceived problems of legal positivism, such as its alleged totalitarian implications. If we add to these questions the circumstance that there is in many quarters a considerable lack of clarity as to what, exactly, the term ‘legal positivism’ stands for, or should stand for, we believe that there is ample justification for bringing together a number of chapters on legal positivism in a volume such as this.

What we offer in this volume, then, is a rather comprehensive and systematic discussion by experts in the field of these and similar questions. Although some authors find fault with legal positivism, or even doubt its continued significance in the legal-philosophical landscape, we believe that legal positivism will continue to attract considerable interest in the future, not only among legal philosophers and legal scholars in general but also among other students of the humanities and the social sciences, such as philosophers, historians, political scientists, sociologists or economists. For what is interesting about legal positivism is not, of course, the taxonomic question of whether a given theory or approach is or is not positivistic, although this question may sometimes be considered important, for example by writers of textbooks, but rather a variety of general and foundational questions that tend to be raised in almost any discussion of legal positivism. For example, there are questions about what law is, and what its purpose or function, if any, is, about its action-guiding capacity and its capacity to live up to the ideals of the Rechtsstaat or the Rule of Law, and about the existence and content of an obligation to obey the law. In addition, there are questions about the relation of law to the state, to coercion, to morality, to norms and human behaviour, to legislation, to judicial decision-making and to custom, and about how to analyse legal statements and interpret legal norms; and there is the general question of whether and, if so, how we can know the answers to these and similar questions; and more. Questions like these have for a long time attracted, and will surely continue to attract, the interest of almost anyone wishing to understand human affairs.

1.1.1 Legal Positivism as an Intellectual Tradition

As we shall see, this volume assumes that we can speak meaningfully of some central tenets of legal positivism, and that legal positivists are thinkers who accept these tenets. Nevertheless, not everything that is said about legal positivism in the volume immediately concerns these tenets. To see the relevance of matters that do not immediately concern the tenets, one may choose to think of legal positivism along the lines of (what we shall refer to as) normative, theoretical, ideological or methodological positivism (to be introduced in Section 1.1.6) or, alternatively, to think of it not as a theory (or a set of tenets) at all but rather as an intellectual tradition that includes a number of writers in different countries over a long stretch of time, dealing with rather different topics, whose connections to one another are at least partly to be found in an attitude to legal scholarship or an interest in certain themes or questions and, perhaps, ultimately in terms of family resemblance in Wittgenstein’s sense.Footnote 4 This way of conceiving of legal positivism is in keeping with our claim that there is in many quarters a considerable lack of clarity as to what the term ‘legal positivism’ stands for, and also with our related claim that in three of the main geographical traditions of legal positivism, the German, the Italian and the French, the equivalents to the English term ‘legal positivism’ have had no very clear meaning.

1.1.2 Geographical Traditions

Compared to natural law theory, legal positivism is a newcomer on the scene. In Europe, it developed in the nineteenth century along somewhat different lines in England, France, Germany and Italy – in the case of Italy due to autochthonous re-elaborations of ideas from the French codification-centred tradition, the German tradition and Auguste Comte’s positivistic philosophy.Footnote 5 Thus, Jeremy Bentham, who wrote on legal positivism already in the late eighteenth century, appears to have been the first legal positivist in England, though it has been said that his predecessor, Thomas Hobbes, too, was a legal positivist, or at least an ancestor of Benthamite legal positivism.Footnote 6 In Germany, Gustav Hugo, Friedrich Carl von Savigny and Georg Friedrich Puchta, all writing in the first half of the nineteenth century, can be said to have been the first legal positivists;Footnote 7 and in France, the members of the exegetical school, including Jean-Charles Florent Demolombe and Raymond-Théodore Troplong, writing in the nineteenth century, are said to have been the first legal positivists.Footnote 8 In Italy, finally, legal positivism in the shape of ideological or methodological (or scientific) positivism was the ruling view until the 1960s; and since then these forms of legal positivism together with theoretical positivism have been the subject of sophisticated meta-philosophical reflections by Norberto Bobbio and Uberto Scarpelli, in particular.Footnote 9

Although the different geographical traditions of legal positivism are similar, being traditions of legal positivism, they are also different. For example, Karl Olivecrona points out that nineteenth-century legal positivism in England and Germany differed in that the former type of theory aimed at providing a factual, naturalistic explanation of the nature of law and did not purport to account for the binding (or obligatory) force of law, whereas the latter type of theory did aim to account precisely for the binding force of law, which it conceived in non-naturalistic terms.Footnote 10 Moreover, the French tradition of legal positivism appears to differ from the other traditions in that even though some scholars and judges have indeed called themselves positivists, or have been called positivists by others, there has been almost no legal-philosophical discussion of legal positivism conceived as a theory of law, though things have begun to change in the past twenty years or so. Indeed, it appears that the equivalents to the English term ‘legal positivism’ in German, Italian and French – Rechtspositivismus, positivismo giuridico and positivisme juridique, respectively – have for a long time had no very clear meaning and that the debates on legal positivism in these jurisdictions have only in the second half of the twentieth century come to touch on the central tenets of legal positivism, as we understand them today, and as they will be presented in this introduction. The various geographical traditions of legal positivism will be treated in Part II of the volume.

1.1.3 Central Figures

We have said that there is in many quarters a lack of clarity as to what ‘legal positivism’ stands for, or should stand for. There can, however, be no doubt that, through the years in the respective traditions, some writers have been considered central figures of legal positivism. Thus, central figures in the German tradition, in addition to von Savigny and Puchta, include Rudolf von Ihering, Georg Jellinek, Hans Kelsen and Ota Weinberger; central figures in the Italian tradition, in addition to Bobbio, include Icilio Vanni, Biagio Brugi, Alessandro Levi and, in more recent times, Uberto Scarpelli, Giovanni Tarello and Luigi Ferrajoli; central figures of the French tradition, in addition to the mentioned members of the exegetical school, include Raymond Carré de Malberg and Léon Duguit;Footnote 11 and central figures in the British tradition, in addition to Bentham, include John Austin, T. E. Holland, H. L. A. Hart and Joseph Raz. Finally, a central figure in the history of legal positivism is the contemporary Argentinian legal philosopher Eugenio Bulygin. The versions of legal positivism defended by some of these central figures will be treated in Part III of the volume. As the reader will see, however, it is not clear that they are always talking about the same thing, and it may in some cases be a challenge to determine the precise sense in which they were thought to be legal positivists, or precisely how this sense relates to our understanding today of what legal positivism is.

1.1.4 Descriptive Legal Positivism: A Framework Theory

As we have said, we may distinguish between different types of legal positivism, such as descriptive positivism, as we might refer to it, theoretical positivism, normative positivism, ideological positivism and methodological (or scientific) positivism. Our focus in this volume, however, is going to be on descriptive legal positivism, which is considered by most of its defenders to be the central form of legal positivism;Footnote 12 and in what follows, we have this version in mind when we speak of ‘legal positivism’, unless we indicate otherwise.

Accordingly, we might say that what legal positivism does, at least as legal positivists see it, is to lay down conditions that have to be satisfied by anything that purports to be a correct theory of law: If X does not satisfy the relevant conditions, X will not be, and cannot be, a correct theory of law. Speaking about a central tenet of legal positivism, the social thesis, Joseph Raz puts it thus: the social thesis ‘is best viewed not as a “first-order” thesis but as a constraint on what kind of theory of law is an acceptable theory’.Footnote 13 On this analysis, Kelsen’s, Hart’s and Raz’s theories are first-order theories of law in the sense that they are theories precisely of law, and they are positivistic in the sense that they conform to the fundamental tenets of legal positivism (to be discussed in Section 1.1.5); and we might therefore refer to legal positivism as a second-order theory of law in the sense that it is primarily a theory about theories of law, not a theory of law.

Alternatively, we might think of legal positivism not as a second-order theory but as a first-order theory that differs from other first-order theories of law, like the ones defended by Kelsen, Hart, Raz and others, by being more general, in much the same way that consequentialism differs from utilitarianism or ethical egoism by being more general. Thus, whereas consequentialism ascribes moral value to actions, events and states of affairs solely because of their consequences, utilitarianism ascribes value to such things solely because of their consequences for human happiness (or perhaps welfare).Footnote 14 On this analysis, too, legal positivism lays down adequacy conditions for theories of law. Some might prefer this latter way of characterising legal positivism on the grounds that they find the distinction between specificity and generality to be less problematic than the distinction between first- and second-order theories.

If we think of legal positivism as a framework theory in one of the ways suggested, that is, as a theory laying down adequacy conditions for theories of law, we see that it is not much of an objection to legal positivism to point out that in itself it does not say much about what law is, how it should be interpreted and applied, or whether it should be obeyed or disobeyed, and so forth. For, on this analysis, to be a legal positivist is not to have a complete theory of what law is, how it should be interpreted and applied, or about law obedience, and so forth.Footnote 15

1.1.5 Descriptive Legal Positivism: Central Tenets

Even though legal positivists differ on a number of issues, most of them accept three central tenets, namely, the social thesis, the separation thesis and the thesis of social efficacy.Footnote 16 In addition, some legal positivists accept a fourth thesis, called the semantic thesis.Footnote 17 Crudely put, the social thesis has it that what is law and what is not is a matter of social fact; the separation thesis says that there is no necessary connection between law and morality;Footnote 18 the thesis of social efficacy says that the validity (or existence) of law presupposes that the law is socially efficacious; and the semantic thesis has it, in one version, that legal normative or evaluative terms such as ‘right’, ‘duty’ and ‘authority’ have different meanings (senses) from the corresponding moral terms and, in another version, that (first-order) legal statements are statements solely about social facts.

Some legal positivists maintain that the backbone of legal positivism is to be found in the social thesis.Footnote 19 The precise meaning of the social thesis has been debated by legal positivists for the past forty years or so, however.Footnote 20 For example, while exclusive legal positivists argue that, properly understood, the social thesis requires (in a conceptual sense) the use of exclusively factual criteria of legal validity, and hold that any reference to moral values (primarily in the rule of recognition but also in, say, constitutional provisions) is best understood as granting the judge power and discretion to create new law,Footnote 21 inclusive legal positivists maintain instead that the criteria of validity can, but need not, be of a moral nature, provided they are grounded in (social) facts.Footnote 22 That is to say, whereas exclusive legal positivists insist that both the basis and the content of the criteria of validity be factual, inclusive legal positivists hold instead that while the basis of such criteria must be factual, their content need not be factual but can be normative or evaluative. One may, however, also think of this debate as concerning the correct interpretation of the separation thesis. On that analysis, whereas exclusive positivists defend the ‘separation thesis’, inclusive positivists defend the ‘separability thesis’.Footnote 23

In more recent years, the jurisprudential debate about the social thesis has also concerned the question of whether the social foundation of law, often taken to be something like a rule of recognition, is to be understood along the lines of legal conventionalism or along the lines of a more recent view called law as a shared activity.Footnote 24 Whereas H. L. A. Hart,Footnote 25 Gerald J. PostemaFootnote 26 and Andrei Marmor,Footnote 27 to mention only a few, have defended a conventionalist account of the rule of recognition, Jules Coleman and Scott Shapiro have both defended a law-as-a-shared-activity account of this foundational rule.Footnote 28 The main difference between these two types of account is that whereas the former takes the social practice underlying, or constituting, the rule of recognition to be necessarily conventional, the latter defends instead an account of said practice according to which a conventional element may, but need not, be part of the practice.

Some legal positivists choose, however, to focus their discussions of legal positivism on the separation thesis instead of the social thesis. For example, although Hart emphasizes the idea of the rule of recognition in the Concept of Law, he explicitly identifies legal positivism with the separation thesis;Footnote 29 and Matthew Kramer in his In Defense of Legal Positivism concentrates on the legal positivist claim that law and morality are ‘strictly separable’, that legality and morality are ‘disjoinable’.Footnote 30 Robert Alexy, too, in his critique of legal positivism, chooses to focus not on the social thesis but precisely on the separation thesis because he believes that the social thesis is not unique to legal positivism but is accepted by all serious non-positivists.Footnote 31

The separation thesis, we have said, has it that there is no necessary connection between law and morality, where the relevant morality is understood to be true morality, not the morality or moralities actually accepted by the subjects of the relevant law. But, as we have pointed out, some contemporary legal positivists, including Joseph Raz, Leslie Green and John Gardner, reject the separation thesis, arguing that there are indeed necessary connections between law and morality.Footnote 32 Gardner, for example, points out that law and morality ‘are necessarily alike in both necessarily comprising some valid norms’.Footnote 33 How, then, are we to understand the separation thesis if we wish to think of it as a tenet of legal positivism? The proper way to qualify this thesis, we believe, is to think of the necessary connection in question as a connection between morality and the content of law.Footnote 34 We may then usefully distinguish between the separation thesis conceived as a thesis about the content of (first-order) legal statements, namely, a thesis according to which such legal statements do not entail (first-order) moral statements,Footnote 35 and the separation thesis conceived as a thesis about legal status, according to which even (grossly) immoral norms can be (part of) law. It seems, however, that the majority of those who consider the separation thesis take it to be primarily a thesis about legal status and only secondarily, if at all, a thesis about the content of legal statements,Footnote 36 often with no explicit view of the logical relation between the two versions of the thesis. Kelsen, for example, appears to have in mind the status question when he maintains that ‘[a]ny content whatever can be law; there is no human behavior that would be excluded simply by virtue of its substance from becoming the content of a legal norm’Footnote 37 and the question of statement content when he claims that ‘[a] statement about the law must not imply any judgment about the moral value of the law, about its justice or injustice’.Footnote 38

To see that there really is a difference between the separation thesis about statement content and the separation thesis about legal status, it may be helpful to consider the position of a moral error theorist, such as John Mackie,Footnote 39 as regards the separation thesis. If you are an error theorist, you believe that all moral statements are false, and this means that you will have to accept the separation thesis about legal status, though you may choose to reject the separation thesis about statement content. For if you do not accept the status version of the thesis, you will not be able to recognize the existence of legal systems, and this would be decidedly odd; if, on the other hand, you do not accept the statement-content version of the thesis, you may without much oddity hold that legal statements entail (false) moral statements.

One reason to focus one’s attention on the social thesis rather than the separation thesis, conceived as a thesis about legal status, is that the latter thesis follows from the former, assuming that the laws of logic do not allow that a normative (or evaluative) conclusion can follow from a (consistent) set of factual premises.Footnote 40 That is to say, if, in keeping with the social thesis, we determine what the law is using factual criteria, and if we cannot deduce a normative (or an evaluative) conclusion from a (consistent) set of factual premises, the separation thesis about legal status follows. We thus assume here that a factual criterion is necessarily a non-normative, and therefore a non-moral, criterion. If ethical naturalism is true, however, this is not so. For, according to ethical naturalism, moral properties are (necessarily) natural, that is, factual, properties.Footnote 41 It does not, however, follow that natural (factual) properties are moral properties; this means that even if it follows from the social thesis that legal properties are natural properties, it does not follow from this thesis that they are also moral properties.

The thesis of social efficacy, which has it that the validity of law (in the sense of membership in the system) presupposes that the law is socially efficacious, that, on the whole, the citizens obey and the legal officials enforce the law, is also an important part of the legal positivist package. As Kelsen puts it, ‘[a] legal order as a whole and the particular legal norms which form this legal order are to be considered valid [in the sense of being binding and, indirectly, in the sense of being members of the system] only if they are, by and large, obeyed and applied, only if they are effective’.Footnote 42 This important thesis has not received much attention from either legal positivists or non-positivists, however,Footnote 43 and, as a result, its import is not absolutely clear.Footnote 44 One may, for example, wonder what counts as obedience, how much obedience or law enforcement is necessary and sufficient for a legal order to be efficacious, or how one is to weigh citizen obedience against the enforcement of the law by officials. For example, should we say that a legal order (a legal system) is socially efficacious, if the citizens disobey its norms but the officials enforce them?

The semantic thesis, too, can be understood in more than one way.Footnote 45 As we have seen, it may say that legal normative (or evaluative) terms such as ‘right’, ‘duty’ and ‘authority’ do not have the same meaning (sense) as the corresponding moral terms, or it may instead say that (first-order) legal statements are statements solely about social facts.Footnote 46 One may accept the former while rejecting the latter version of the thesis; but if one rejects the former, one will also have to reject the latter, unless one accepts ethical naturalism. In any case, most scholars who have considered the semantic thesis in print have focused on the former version;Footnote 47 whereas some prominent legal positivists accept this version of the thesis,Footnote 48 others, equally prominent, reject it.Footnote 49

It is worth noting here that one reason to accept the version of the semantic thesis according to which normative or evaluative terms have a special, legal sense is that in this way one can uphold the separation thesis conceived as a thesis about the content of legal statements. For if ‘right’ and ‘duty’, say, have special, legal senses, which differ from their moral senses (and do not in any way include the latter), then to maintain that Smith has a legal duty to pay his taxes is not necessarily to maintain that Smith has a moral duty to pay his taxes. If instead one rejects the semantic thesis but wishes to uphold the separation thesis conceived as a thesis about the content of legal statements, one could perhaps follow Raz and maintain that law-appliers and others make detached, instead of committed, legal statements.Footnote 50 The fundamental tenets of legal positivism will be treated in Part IV of the volume.

1.1.6 Other Types of Legal Positivism

Legal positivism conceived along these lines – descriptive legal positivism, as we have called it – should be distinguished from normative positivism.Footnote 51 Whereas the former is an analytical theory that concerns the concept of law, or the nature of law, or both, the latter has it that there are good normative (typically, moral) reasons for accepting one or more of the mentioned main tenets of (descriptive) legal positivism, for example, that the administration of justice becomes more stable and predictable if law-appliers and citizens do not have to exercise moral judgement in order to find out what the law is.Footnote 52 Thus, as normative positivists see it, the question of which theory of law to embrace is a normative, not an analytical one. To be able to take a stand on whether the basic tenets of (descriptive) legal positivism are correct, they reason, one has to consider questions about the value and function(s) of law and legal arrangements.Footnote 53

Descriptive positivism is also different from both theoretical positivism and ideological positivism, which have been discussed especially, but by no means exclusively, in the Latin world. Whereas theoretical positivism (in the narrow sense) is a substantive theory of law, according to which law is a set of commands issued by the sovereign, legal interpretation is a cognitive and the application of law is a deductive enterprise, ideological positivism has it that one ought to obey the law because it is the law, or at least that one ought to obey the law if it promotes or realises good values, like peace, order, formal justice, legal certainty and so forth.Footnote 54 Finally, descriptive positivism is different from methodological positivism, which is a theory not of law but of legal science, and which has it that legal science, properly understood, is descriptive and value-neutral.Footnote 55 We might say with Stephen Perry that methodological positivism has it that there is no necessary connection between morality and legal science.Footnote 56

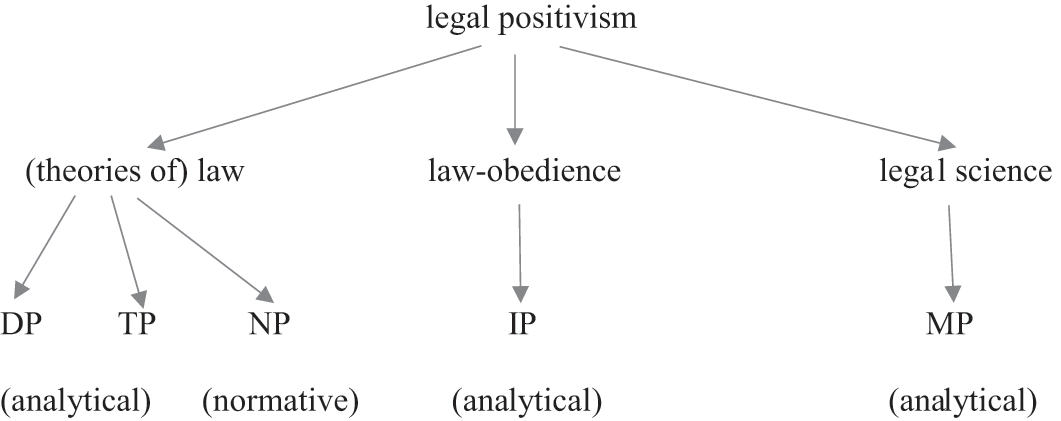

The difference between normative and methodological positivism, then, is that whereas normative positivists maintain that there are good normative (and, in most cases, no non-normative) reasons to espouse the mentioned tenets of (descriptive) legal positivism, methodological positivists are concerned not with law but with legal science, and maintain that legal science, properly understood, is value-neutral. That is to say, whereas both descriptive and normative positivism are concerned with law (or theories of law), methodological positivism is concerned with legal science; and whereas both descriptive and methodological positivism are (or purport to be) descriptive (or analytical), normative positivism is explicitly normative.Footnote 57 As Figure 1.1 illustrates,Footnote 58 we can thus think of legal positivism as a theory of law (or a theory of theories of law), as a theory of law-obedience, or as a theory of legal science.

Figure 1.1 Types of legal positivism

1.1.7 Objections to Legal Positivism

Although legal positivism is, and has been, a fairly widely accepted theory of law, it has not been without its critics. One recurring objection has been that one cannot account for the normativity of law within the framework of legal positivism. Not only have non-positivists, such as Lon Fuller and Ronald Dworkin, objected to Hart’s theory of law, that it cannot account for the normativity of law,Footnote 59 but also both Kelsen and Hart have objected to John Austin’s theory of law, that it cannot distinguish between legal norms and the orders of a highwayman. As Hart once put it, ‘Law surely is not the gunman situation writ large, and legal order is surely not to be thus simply identified with compulsion.’Footnote 60 This general objection is a bit difficult to assess, however, because it is not obvious how we are to understand the relevant type of normativity.Footnote 61 For example, it appears that whereas Fuller and Dworkin, and even Kelsen, had in mind some type of moral normativity, Hart had in mind a specifically legal, non-moral normativity.Footnote 62 And whereas it seems clear that one cannot account for the normativity of law conceived as a type of moral normativity while insisting on the separation thesis, one could likely account for Hart’s specifically legal normativity, while defending this thesis.

A related question is whether legal positivists have to be moral nihilists or sceptics, or at least expressivists (or non-cognitivists) or relativists.Footnote 63 The idea would be that if morality is in some sense subjective, then any infusion of moral considerations into the process of determining what the law is would contribute to making the law indeterminate,Footnote 64 and this in turn would explain why legal positivists insist on the separation of law and morality. One could, however, also reason that if expressivism, or error theory, is true, the question of whether law is necessarily normative does not make much sense, as there will then be no such property as normativity that the law could have, either contingently or necessarily. Consequently, legal positivists who find the question of the normativity of law to be interesting have good reason to espouse some version of moral cognitivism. As one might expect, a brief survey of the writings of leading legal positivists makes it clear that they have differed quite a bit on meta-ethical questions: Whereas some have espoused versions of non-cognitivism or (meta-ethical) relativism,Footnote 65 others have defended moral cognitivism.Footnote 66 The questions of the normativity of law and meta-ethics will be discussed in Part V of the volume.

Let us note, finally, that some authors have raised quite different objections either to legal positivism, or to positivist theories of law, such as Hart’s theory. For example, Gustav Radbruch has argued that legal positivism facilitated the spread of Nazism in Germany,Footnote 67 and Ronald Dworkin has objected that Hart’s theory of law cannot account either for the existence of legal principles or for so-called theoretical disagreement.Footnote 68 These objections, especially Radbruch’s objection, conceived as a general claim about totalitarian tendencies of legal positivism, have been rather popular among critics of legal positivism and so deserve close scrutiny.Footnote 69 As for the Radbruchian objection, we might say that the idea is that descriptive legal positivism, in at least some of its versions, really amounts to ideological positivism. These objections will be considered in Part VI of the volume.

1.2 Contributions

The volume is divided into six parts. Part I deals with fundamentals of legal positivism, Part II considers the main traditions of legal positivism, and Part III treats central figures of legal positivism. Part IV treats the main tenets of legal positivism, Part V deals with questions of normativity and values, and Part VI, finally, considers various critiques of legal positivism.

Taking the essential thesis of legal positivism to be that all law is positive law or, if you will, that all law has sources, Leslie Green considers in Chapter 2 the relationships between legal positivism and ‘its closest cousin’, legal realism, focusing mainly on American legal realism. He aims, in particular, to explain why legal realists disagree with legal positivists about the role that legal rules play in the explanation of judicial decision-making. Noting that positivists and realists agree that law is constituted by social facts, that judges sometimes make law, and that law is morally fallible and should be studied in a realistic spirit, Green locates the point of disagreement in their different understandings of the boundary-lines between law and non-law, a boundary-line that is important to legal realists, too. His idea is that, unlike positivists, realists believe that a significant number of sources of law are only permissive sources – that is, sources such as foreign law, international treaties or academic writings, which judges are permitted but not required to use, and which can sometimes, perhaps rather often, be outweighed by considerations of policy, or justice, or the equities of the case and so forth – and that this fact explains why realists can hold that law is so indeterminate as to undermine the causal efficacy of legal rules, while sharing the positivist view that all law has sources. Green also maintains that the dispute between realists and positivists, thus conceived, is partly conceptual and partly empirical because it involves a failure on the part of the realists to grasp what rule-following involves as well as a failure to look at the given empirical material, that is, instances of rule-following in and out of court.

In Chapter 3, Fred Schauer discusses normative positivism, explaining that this type of positivism comes in two main versions, namely, in the shape of a prescription to legal actors and in the shape of a prescription to legal institutional designers. He begins by distinguishing the position of normative positivists from the position of those who claim that (descriptive) legal positivism is more normative than its proponents have been willing to acknowledge, and he proceeds to consider Jeremy Bentham’s normative positivism as well as H. L. A. Hart’s thoughts, as expressed in several different writings, about why, normatively and not merely descriptively, a positivistic understanding of the concept of law should be preferred to a non-positivistic one. Having done that, Schauer argues that a full appreciation of the artefactual nature of law leads to the conclusion that a culture can modify its concept of law in order to make it as useful a concept as possible, and that if normative positivism is a plausible position, it follows not only that choosing a concept of law on moral grounds is a moral position but also that choosing to see the enterprise of legal theory in a normative way itself amounts to a normative position.

Brian Leiter continues in Chapter 4 with a consideration of the relation between legal positivism and legal realism. He argues that H. L. A. Hart’s theory of law is really a species of legal realism in a general sense that covers both American and Scandinavian realism, and that there are four ways in which this is so, namely, that the law operates primarily outside the courts; that the law is sometimes rationally indeterminate; that the law is explicable in wholly naturalistic terms; and that the law is not necessarily morally good. He points out, however, that American and Scandinavian realism are nevertheless quite different, and argues that H. L. A. Hart’s well-known critiques of these two types of legal realism are misguided. Focusing on American legal realism, he explains that Hart fails to distinguish clearly between conceptual rule-scepticism, which is a theory about the nature of law, according to which law consists in court decisions and predictions about them, and empirical rule-scepticism, which says that there are some cases (especially appellate ones) where judges are not bound by legal rules. As Leiter sees it, while conceptual rule-scepticism is indeed mistaken, the Americans do not embrace it, and while they do embrace empirical rule-scepticism, this type of rule-scepticism is justified. Leiter also maintains that Joseph Raz’s view that law necessarily claims legitimate authority involves a highly moralised and unrealistic view of what it is for law to claim authority – namely, the so-called service conception of authority – and actually amounts to a repudiation of realism in legal theory, including Hart’s realism.

In Part II, our contributors turn to consider the history of legal positivism. Stephan Kirste begins in Chapter 5 with an account of the German tradition. Discussing in chronological order legal scholars who were active in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, he identifies four main types of German legal positivism, namely, jurisprudential, sociological, naturalistic, and statutory positivism, as well as a fifth type of legal positivism that he calls the general theory of law. His idea is that these theories were legal positivist theories because they shared an epistemological aim, namely, that of establishing legal science as a science in its own right, independent of both the natural and the social sciences, and because they held that only positive law in the sense of enacted norms or customary norms is law. He then considers in more detail the theories of Hans Kelsen and Gustav Radbruch as examples of legal positivist theories, pointing out – contrary to what Radbruch and others have claimed – that the National Socialists were not legal positivists but were actually critical of legal positivism. He also points out that although legal positivism lost its dominance in the wake of the post–World War II revival of natural law theory, it was soon able to reassert its influence, and he considers the theories of Ota Weinberger, Niklas Luhmann and Norbert Hoerster as examples of post–World War II versions of legal positivism. Finally, Kirste points out that since the late sixties, several authors, including Peter Koller and Ottfrid Höffe, have been aiming to overcome the gulf between natural law theory and legal positivism, and that, in contemporary German legal scholarship, the debate between legal positivism and non-positivism continues, although it is now less intense than it used to be, partly because the Basic Law of 1949 has solved many contentious issues by including principles like human dignity, individual freedom, equality and more.

Michel Troper continues in Chapter 6 with an account of the French tradition of legal positivism. Although he points out that there is hardly a single French legal scholar who subscribes to any of the three versions (or aspects) of legal positivism distinguished by Norberto Bobbio,Footnote 70 namely, theoretical, methodological and ideological positivism, Troper identifies five groups of French legal scholars who have called themselves legal positivists or have been called legal positivists by others, namely, the exegetical school, the sociological school and Leon Duguit, Raymond Carré de Malberg, the Vichy scholars, and the analytical legal positivists; and he proceeds to consider them in turn. He explains, inter alia, that Carré de Malberg put forward a theory of positive law that aims to be descriptive, according to which positive law is a product of the will of the state and the state possesses an inherent capacity to obligate the citizens by means of its laws. He points out, however, that while Carré de Malberg’s description of French positive law aims to reveal an essence of the state, in reality the description proceeds from a set of abstractions that reflect his own normative theory of the state; and that this means that Carré de Malberg, while professing to espouse methodological positivism, is actually closer to defending ideological positivism.

In Chapter 7, Riccardo Guastini considers the Italian tradition of legal positivism and argues that the idea of legal positivism conceived as a type of legal philosophy appeared for the first time in a 1950 essay by Norberto Bobbio, and that Bobbio proceeded in a later essay to make distinctions among methodological positivism, theoretical positivism and ideological positivism. Guastini explains that Bobbio argued that methodological positivism is a (normative) view about legal scholarship, namely, that it should be descriptive; that theoretical positivism is a substantive theory of law, according to which law is a set of commands issued by the sovereign, legal interpretation is a cognitive enterprise and the application of law is a matter of deduction; that ideological positivism is the view that one ought to obey the law regardless of its content; and that all three types of legal positivism share the view that there is no such thing as natural law. Guastini also explains that contemporary Italian legal philosophers reject theoretical positivism and mostly conceive of legal positivism along methodological lines, holding that there is no natural law, that it is important to distinguish between expository and censorial jurisprudence (in Bentham’s terminology) and that there is no (objective) obligation to obey the law.

In Chapter 8, Gerald J. Postema considers the British tradition of legal positivism, arguing – contrary to the received opinion – that we may view contemporary, post-Hartian British legal positivism or, more broadly, post-Hartian British jurisprudence as having developed naturally from the legal philosophies put forward by Matthew Hale and Thomas Hobbes in the seventeenth century, which in turn were part of an earlier and philosophically more ambitious, non-positivistic tradition, the thetic tradition, dating back to Marsilius of Padua, Jean Bodin and, ultimately, to Thomas Aquinas. And if we do, Postema continues, we will see that instead of being a quirky ancestor of the British positivist tradition, Jeremy Bentham appears as the high point of the thetic tradition, which came to an end when John Austin disengaged British jurisprudence from Bentham’s legal philosophy. We see, then, Postema notes, that Austin’s jurisprudence changed the direction of British jurisprudence from the thetic tradition to a positivist approach to the study of jurisprudence, one that continues to this day and sees jurisprudence as isolated not only from moral philosophy and metaphysics but also from history, social theory and comparative studies. He notes in conclusion that one need not embrace Bentham’s or Hobbes’s substantive doctrines to sense that something may have been lost with the change of direction initiated by Austin.

Part III is devoted to central figures of legal positivism. In Chapter 9, Philip Schofield considers Jeremy Bentham’s legal positivism. He explains that Bentham made a fundamental distinction between expository jurisprudence, which concerns the law as it is, and censorial jurisprudence, which concerns the law as it ought to be, and between local and universal expository jurisprudence, and that he took the subject-matter of universal expository jurisprudence to be terms (or concepts), such as ‘obligation’, ‘right’ and ‘validity’, that are common to all legal systems. He proceeds to point out that Bentham introduced a method for analysing or clarifying such terms, namely, the method of paraphrasis, according to which the analyst is to focus not on a term in isolation but on a sentence that features the term, and to attempt to find another sentence that is equivalent to the first and is such that its terms correspond to simple ideas that are derived from physical objects that we can perceive with our senses. Finally, Schofield argues, contrary to H. L. A. Hart, that Bentham was neither a substantive nor a methodological legal positivist. For, he explains, Bentham’s utilitarianism, characterised by its naturalistic basis and its claim to govern every aspect of human action, led him to conceive of value judgements as a type of empirical statements and hence the idea of a conceptual separation of fact and value, as required by substantive legal positivism, would have made no sense to him. Moreover, he points out, Bentham would not have accepted the methodological view that expository jurisprudence is a value-neutral enterprise, since this enterprise, like every other, was undertaken just because of its value in terms of promoting utility.

Michael Lobban continues in Chapter 10 with a consideration of John Austin’s legal positivism. Having explained that Austin thought of jurisprudence as the study of concepts, principles and distinctions that are common to various, possibly only mature, legal systems, he proceeds to consider Austin’s command theory and concept of a sovereign as well as Austin’s thoughts on the relation between law and morality and on legal reasoning and judge-made law. He explains that, on Austin’s analysis, laws properly so-called, as distinguished from rules of positive morality, are commands issued by the sovereign to the subjects, and that something is a command only if there is a sanction behind it. He also explains that a sovereign is a person (or a body of persons) to which the bulk of the population is in a habit of obedience, and who is not themselves in a habit of obedience to another determinate human superior, and considers the objection that the idea of a habit of obedience cannot account for the legal authority of the lawmaker, for the idea of a succession of lawmakers or for the idea of a legally limited lawmaker. Lobban also observes that Austin argued that there is no necessary connection between law and morality, defended a version of rule-utilitarianism and held that the principle of utility was a good index to divine law. Finally, he points out that Austin advocated a textual approach to the interpretation of statutes, that he held that the law in a precedent is to be found in the ratio decidendi of the precedent and that customary rules do not become legal rules until they are recognised by courts.

Starting out from the presupposition that legal positivism is premised on the assumption of a strict separation among the world of law, the world of morality and the social world, Jens Kersten explains in Chapter 11 that George Jellinek’s phenomenological theory of reflective legal positivism aims to answer the question of how the world of law is connected to, and can respond to, changes in the social world. The general idea of Jellinek’s legal positivism, he explains, is that a state has two sides, a legal side and a social side, and three elements, people, territory and political power, and that these elements have to be structured and defined with the help of the concept of legal auto-limitation of political power, that is, the concept of the state’s capacity to limit its own power by incurring legally binding obligations. On this analysis, Kersten points out, the central element in Jellinek’s legal positivism is that of political power, which structures and defines the territory and the people (the citizens) and also structures and defines the state by binding it to legal rules, especially constitutional rules.

In Chapter 12, Michael Green defends a ‘Kelsenian’ non-naturalist and non-reductive version of legal positivism that, he argues, is similar to the pure theory of law expressed in Hans Kelsen’s works. Kelsen is a peculiar legal positivist by Anglophone standards because he rejects the social thesis. As Kelsen sees it, law does not ultimately depend upon social facts about a community’s legal practices. The legal order is normative and so stands outside the spatiotemporal and causal world of nature. Nevertheless, Kelsen can be described as a positivist for two reasons. First, he accepts the separation thesis: law does not ultimately depend upon moral facts. Second, he accepts what Green calls the ‘positivity thesis’. When a world without social facts is interpreted in the light of the legal order, there are no legal obligations. All that is interpreted as existing, legally, is an authorisation: human beings are empowered to generate legal obligations by creating communities with legal practices. In this sense, all legal obligations are posited – only worlds with certain social facts are interpreted as having legal obligations, and the content of the obligations is drawn from those social facts.

Green argues that the heart of the Kelsenian argument against the social thesis is a form of legal anti-psychologism that is similar to the logical anti-psychologism offered by Gottlob Frege. Inferences from premises about social facts to legal conclusions cannot be based in psychological, social or any other contingent facts because the relationship between the truth of the premises and the truth of the conclusion will not be necessary. These inferences must instead be based in facts about a non-natural legal order. This is similar to Frege’s argument that the necessity involved in logical inferences can be explained only by reference to a non-natural ‘third realm’. It is also similar to the moral non-naturalist’s argument that the necessity involved in moral inferences can be explained only by reference to a non-natural moral order.

A challenge to this Kelsenian position is the view that the non-natural facts upon which legal inferences are based concern the concept of law, not a legal order. According to these concept-of-law facts, each community has an independent legal system, and the way that one should make inferences in that system depends solely upon social facts about the relevant community’s legal practices. Green argues that this approach can be successfully resisted by invoking Kelsen’s doctrine of the unity of law. He concludes that the question of the viability of the doctrine is therefore a question of the utmost importance in philosophy of law.

Matthew Kramer argues in Chapter 13 that H. L. A. Hart was able to reinvigorate the tradition of legal positivism by disconnecting legal positivism from the command theory of law defended by his predecessors Bentham and Austin; by introducing through his own theory of law some new and fruitful concepts into legal thinking, such as the internal point of view, the distinction between primary and secondary rules, and the idea of a rule of recognition; by clarifying the meaning of and the reasons behind the separability of law and morality through a consideration of the many different ways in which law and morality are, or could be, connected; and by introducing the idea of the minimum content of natural law and clarifying the relation between this idea and the separability of law and morality. Kramer also explains that, even though a legal system can fulfil its basic function of securing the conditions of civilisation only if it includes rules prohibiting murder, assault, fraud and other types of very serious misconduct, the relevant protection provided by the legal system against those types of misconduct need not be extended to all groups of citizens. Consequently, because no true moral principles would permit such a difference in treatment between groups of citizens, Hart’s account does not reveal any necessary connections between those principles and legal norms.

In Chapter 14, Pierluigi Chiassoni explains that, in the early 1960s, Norberto Bobbio put forward a descriptive theory of legal positivism consisting of two main parts, namely, a definition of legal positivism as the view that there is no law but positive law (the exclusivity thesis) and an analysis of such a view as one that would encompass ‘three aspects’, namely, legal positivism as an approach to the study of law (scientific or methodological positivism), legal positivism as a theory of positive law (theoretical positivism) and legal positivism as a doctrine of obedience to positive law qua law (ideological positivism). He proceeds to explain that legal positivism as an approach to the study of law involves a commitment to a value-neutral study of positive law; that theoretical positivism encompasses both a narrow and a broad theory; and that we may distinguish among three versions of legal positivism as a doctrine of obedience to positive law qua law, namely, (i) an unconditional version, (ii) a moderate, conditional, relative version and (iii) a very moderate, conditional, relative version, and that these versions differ in important ways. As a second dimension of Bobbio’s discussion of legal positivism, Chiassoni considers Bobbio’s theory of legal science, distinguishing three stages of its development and characterising them as amounting, in turn, to an anti-positivist, a positivist and a post-positivist conception of legal science, respectively.

In Chapter 15, Brian Bix considers Joseph Raz’s approach to legal positivism. Bix’s focus is on Raz’s version of the social thesis, the so-called sources thesis, according to which all law is source-based, in the sense that the existence and content of law is determined using exclusively factual (social) considerations. He considers Raz’s two main arguments in support of the sources thesis, namely, the argument from authority and the argument from different functions, as well as certain objections to these arguments put forward by other legal philosophers, including Jules Coleman, Ronald Dworkin and John Finnis. The argument from authority, he explains, is that law necessarily claims legitimate authority, that the function of a practical authority is to mediate between reasons for an action and the action, that the authority would not be able to perform this function if the subjects of the authority had to consider the reasons for the action in order to figure out what the authority’s decision was, and that the subjects must be able to see the decision as the authority’s pronouncement. The argument from different functions is that deliberation and execution are two different functions, that moral considerations are appropriate on the level of deliberation but not on the level of execution, that determining what the law is is a matter of discerning the products of other institutions’ prior deliberation, and that while judges applying statutes and deciding cases may be involved both in executing the products of prior legislative and judicial decisions, and in deliberating anew (in modifying existing law or filling in gaps), the distinction between the two remains important.

In Chapter 16, María Cristina Redondo considers Eugenio Bulygin’s legal positivism. Having explained that Bulygin is an analytical philosopher who espouses an anti-realist meta-ethics and who conceives of legal philosophy as analytical philosophy applied to the legal domain, she proceeds to explain that Bulygin’s legal positivism embraces the separation thesis, a version of the social thesis (which Bulygin calls the ‘social sources thesis’) and an indeterminacy thesis according to which law is sometimes indeterminate and that in such a case the judge has discretion to decide the case before him; and, she adds, Bulygin holds that it follows from his version of the social thesis that law can be necessarily normative only in a weak, relative sense. Redondo explains that Bulygin espouses two methodological theses that are positivistic, namely, that the task of legal philosophers is to explicate legal concepts, and that we need to maintain in our legal thinking a distinction between norms and normative propositions; and that he espouses three substantive theses that are also positivistic, namely, that legal positivists must adopt a concept of relative normative validity in order to account for the existence of legal rights and duties, that legal interpretation must proceed on the assumption of linguistic conventionalism and that there is a fundamental and unbridgeable distinction between prescriptive and power-conferring norms. She points out that the reason why these theses can be said to be positivistic is that they all, in one way or another, make a value-neutral study of law possible, that is, they make methodological positivism possible.

Part IV is devoted to the main tenets of legal positivism, namely, the social thesis, the separation thesis, the thesis of social efficacy and the (optional) semantic thesis. The first three chapters are devoted to the social thesis. Conceiving of legal positivism as a conceptual theory about the nature, as distinguished from the validity, of law, and focusing on an important version of legal positivism thus conceived, namely social-practice legal positivism, Stefano Bertea considers in Chapter 17 two ways of understanding the social thesis, namely, along the lines of legal conventionalism and law as a shared activity, respectively. He argues that on neither interpretation of the social thesis can social-practice legal positivism account for the necessary normativity of law, that is, for the necessary capacity of law to impose (genuine) obligations and confer (genuine) rights on both officials and citizens. Bertea points out that there are fundamentally two ways in which legal positivists conceptualise legal obligation, namely, as a genuine requirement set forth in the law or else as a perspectival requirement, and that on the former conceptualisation, legal obligations will bind only those who are committed to the legal enterprise, and that on the latter, they will bind only those who adopt the standpoint of the legal system; and he objects that on the former conceptualisation, legal positivism fails to account for legal obligations that apply to the citizens, and that on the latter interpretation, it turns out that law is not really necessarily obligation-imposing at all.

In Chapter 18, Tomasz Gizbert-Studnicki considers the question of how we are to understand the social thesis and whether the social thesis, properly understood, can handle Hume’s guillotine, that is, the thesis that one cannot deduce a normative (or an evaluative) conclusion from a (consistent) set of factual premises. Having distinguished three interpretations of the social thesis, he proceeds to focus on one of these, the social fact thesis, according to which the existence and the content of legal facts are ultimately fully determined by brute social facts, and which is stronger than the other two theses. Gizbert-Studnicki then considers three different ways of understanding the relation between social facts and legal facts along the lines of the social fact thesis, namely, reduction, supervenience and grounding. He maintains that, while all three relations are more or less problematic, the grounding relation is to be preferred, and that adopting the idea of grounding helps us avoid Hume’s guillotine. For, he points out, grounding is not a matter of entailment, which is a relation between propositions, but is a metaphysical relation that holds between facts.

Torben Spaak argues in Chapter 19 that legal positivists need to consider the social thesis in light of an important distinction between two levels of legal thinking, namely, the level of the sources of law (validity or existence) and the level of the interpretation and application of law (content), and that they have good reason to restrict the scope of the social thesis to the former level. He argues that, by restricting the scope of the social thesis in this way, inclusive legal positivists can avoid having to assume that moral judgements can be true in a non-relative way, that exclusive legal positivists can avoid having to say that judges are creating new law instead of applying pre-existing law, if and insofar as they invoke moral considerations in their interpretation and application of the law, and that both inclusive and exclusive legal positivists can avoid Dworkin’s theoretical disagreement objection. He argues in conclusion that legal positivism conceived as a theory about the validity or existence of law will still be a significant theory. For, he points out, since judges and other law-appliers rarely deviate from the plain meaning of statutory provisions, even ‘uninterpreted’ legal norms can guide human behaviour; and this means that legal positivism thus conceived retains a feature valued by all legal positivists, namely, that it makes it possible to present the law of the land in a morally neutral way.

Andrei Marmor continues in Chapter 20 with a consideration of the separation thesis, which he understands as saying that whether a given norm is legally valid (in the sense of being a member of the relevant legal system) depends on its sources, not its merits. Observing that the distinction between sources and merits is very close to the distinction between is and ought, he considers the objection – raised by Ronald Dworkin, in particular – that the separation thesis cannot be upheld because it is impossible to distinguish between sources and merits, between is and ought. Responding to this objection, Marmor considers not only the case of what grounds the validity of legal norms but also the parallel case of what makes an object a piece of art, and argues that the separation thesis can indeed be upheld, provided we see it as an answer not to the question ‘What is law?’ but to the question ‘What counts as law?’. He concludes by pointing out that his response is in keeping with a central concern on the part of legal positivists, namely, that of providing a reductive explanation of legal validity, that is, a complete explanation of legal validity in terms of social facts, and that it also offers support for exclusive over inclusive legal positivism.

In Chapter 21, Wil Waluchow considers the theories known as inclusive and exclusive legal positivism. He begins by explaining that the idea behind the separation thesis is that there is nothing in the bare notion of law that guarantees that law has any degree of moral merit, and proceeds to present Ronald Dworkin’s challenge to the separation thesis, namely, that since law necessarily consists not only of the so-called settled law (statutes, precedents and so forth) but also of the principles of political morality that are part of the best constructive interpretation of the settled law, the connection between what the law is and what the law ought to be is much stronger than the separation thesis allows for. He then considers the responses to Dworkin’s challenge by the adherents to exclusive and inclusive positivism, respectively: Whereas exclusive positivists insist that the separation thesis, properly understood, has it that, as a conceptual matter, legal validity cannot depend on morality, inclusive positivists maintain instead that the thesis has it that legal validity can, but need not, depend on morality. Finally, Waluchow considers and rejects Joseph Raz’s argument from authority, which supports the exclusivist interpretation of the separation thesis, while accepting Jules Coleman’s argument from convention, which supports the inclusivist interpretation of said thesis, adding that inclusive legal positivism can more easily account for the ways in which moral and legal validity appear to interact with each other in modern constitutional democracies.

In Chapter 22, Brian Tamanaha discusses the thesis of social efficacy, that for law to exist it must be generally obeyed by the populace. He begins by arguing that not only are many legal systems not socially efficacious, because in many situations significant parts of the population do not obey the law but follow other sets of norms, but it is also true that two (or more) legal orders may be efficacious in the same society, sometimes in different parts of a country. He concludes from this that what he refers to as the monopoly view of law, that there is in each society one and only one legal order that is supreme, on which much legal theorising is premised, is clearly false. Turning to the idea of law-obedience, which is required by the social efficacy thesis and which he takes to involve as a conceptual matter a conscious attempt on the part of the citizens to follow the law, Tamanaha argues that the notion that the citizens obey the law cannot be squared with the fact that many, perhaps most, people do not really know what the law requires of them, and that this in turn means that we need a different conception of social efficacy, namely, one according to which the social efficacy of law is to be found in the presence of a background legal fabric that people rely on without having any specific knowledge of the content of the law. He then explains the import of this idea of social efficacy in terms of five factors, including the growth and proliferation in the past 200 years of law-utilising public and private organisations as the predominant vehicles of social action, and the frequent use of fixed form contracts.

Michael S. Green concludes this part of the volume, in Chapter 23, with a consideration of a strong version of the semantic thesis, according to which legal statements are descriptive statements solely about social facts. He starts out from the foundational thesis of positivism, the social thesis, which has it that the existence and content of the law are ultimately based solely in social facts about a community. But Green notes that there are two versions of this thesis. Under the reduction version, a legal system and its laws consist of social facts. Under the assignment version, by contrast, they are not social entities at all. They are norms, understood as abstract objects. But the grounds for assigning these abstract objects to a community are ultimately solely social facts. Focusing on the assignment version of the social thesis, Green asks, first, ‘Does the semantic thesis follow from the social thesis?’ His answer to this question is no. Even if the social thesis is true, legal statements need not be solely about social facts. Indeed, they could be about moral facts. He then asks, ‘Even if the semantic thesis does not follow from the social thesis, to what extent do legal statements actually conform to the semantic thesis?’ He argues that, for assignment positivists, there is an easy reason to conclude that the answer to the second question is negative in the sense that legal statements describe abstract objects. Green argues that this simple account of the semantics of legal statements is superior to expressivist accounts because it avoids the Frege-Geach problem. It is also superior to Raz’s account, in which legal statements describe moral facts, because it can explain why those who make legal statements need not be committed to conformity with the law. He also argues that the simple account, not expressivism, is the one adopted by H. L. A. Hart.

Part V concerns questions about normativity and values in relation to legal positivism. Kevin Toh begins in Chapter 24 by arguing that legal philosophers inquiring into the nature of law should follow meta-ethicists and abandon (what Toh calls) the double-duty presumption – that is, the presumption that the facts that amount to the existence of a legal system must also constitute the ultimate grounds of first-order legal judgments. Still, Toh explores the possibility of there being some sort of non-contingent connection between first-order legal thinking and second-order theorising about the nature of law, or, more specifically, the possibility of the facts that amount to the existence of a legal system imposing some modal constraints on the composition of ultimate legal grounds, so that only norms that satisfy certain moral or all-things-considered normative tests qualify as legally valid norms. He considers, in particular, Peter Railton’s recent attempt to strengthen Hart’s account of acceptance of norms by arguing that, in genuine normative guidance, acceptances must be accompanied by positive evaluations of the goals or purposes that would be achieved by following the norms. Toh concludes, however, that, in the end, Railton’s account of legal systems, based on his account of normative guidance, does not quite implicate a significant modal constraint on the composition of the ultimate legal grounds. And this result counsels against conceiving both legal positivism and anti-positivism as anything more than strictly first-order legal theses about the law of particular jurisdictions.

In Chapter 25, Brian Bix considers the question of the normativity of law within the framework of legal positivism. He begins by pointing out that the very idea of the normativity of law has been understood in different ways by different authors, and while writers on the normativity of law often purport to be ‘explaining the normativity of law’, it is often left unclear precisely what is meant by that. He goes on to propose that we analyse the concept of normativity in terms of reasons for action, arguing that such reasons must be something more than prudential reasons and pointing out that the proper question is whether law gives us reasons for actions of the relevant type that we would not have without law. He also considers the difficulty that Hume’s law creates for legal positivists who wish to account for the normativity of law, and the possibility of legal normativity as sui generis. Bix proceeds to consider consequentialist justifications for the normativity of law proposed by Hobbes and Hume, Kelsen’s theory of the basic norm, Gerald Postema’s claim that the rule of recognition is a coordination convention, Scott Shapiro’s planning theory of law, and David Enoch’s triggering account, according to which law gives rise to reasons for action by triggering non-legal reasons that already apply to us. Given the problems with these approaches, Bix concludes that it is difficult to establish from within the legal positivist tradition that law creates entirely new moral obligations.

In Chapter 26, José Juan Moreso considers Luigi Ferrajoli’s ‘Garantismo’, a theory of law related to legal positivism that has been quite influential in the Italian- and Spanish-speaking world. He explains that the word ‘Garantismo’ suggests a conception of law as a system of constitutional guarantees of human rights, and distinguishes two main ideas in Ferrajoli’s theory, namely, the separability (separation) thesis and a distinction between valid law and law in force. Ferrajoli’s idea, Moreso explains, is that the introduction into a legal system of constitutional rights gives rise to a distinction between validity and social efficacy, since even if a statute enacted by the legislature violates a constitutional right, it might become socially effective. He points out, however, that the distinction between legal validity and legal existence is not new and can actually be traced back to the Federalist Papers and the American case Marbury v. Madison of 1803, and that Ferrajoli’s conception of constitutional democracy is very similar to Dworkin’s conception. Having done that, Moreso introduces Ferrajoli’s distinction between a constitutionalism of guarantees and a constitutionalism of rights, where the former, positivistic conception of constitutionalism accepts the separability thesis and conceives of legal norms as rules, and the latter, anti-positivistic conception rejects the separability thesis and conceives of legal norms as rules or principles. He criticises this distinction and Ferrajoli’s preference for the former conception, however, arguing that – contrary to what Ferrajoli thinks – accepting a distinction between rules and principles does not have to lead to lack of legal certainty. Finally, Moreso points out that Ferrajoli is best thought of as an inclusive legal positivist.

Part VI, finally, is devoted to critiques of legal positivism. Martin Borowski argues in Chapter 27 that Radbruch’s most important critique of legal positivism is to be found not in his explicit writings on legal positivism but in his own legal philosophy, especially the so-called Radbruch formula of 1946, and that the Radbruch formula entails a rejection of the separation thesis with an eye to the criteria for the identification of valid legal norms. What is more, he argues that Radbruch’s basal criterion, according to which ‘law is the reality whose meaning is to serve justice’ – the basal criterion Radbruch supported even before World War II – implies a necessary connection between law and morality. Radbruch’s explicit claim, Borowski goes on, that legal positivism was to blame for the situation in Germany is unconvincing because the Nazis did not, as a matter of fact, hold that law is law and should be applied according to its plain meaning in all circumstances but were actually willing to apply a statute contrary to its wording if this suited their purposes.

In Chapter 28, Kenneth Winston argues that Lon Fuller’s critique of legal positivism was rather special in focusing on issues that lay beneath the surface of the usual intramural disputes, and thus related only indirectly to what positivists such as Kelsen and Hart said explicitly when expounding their views. Winston explains that, as a pragmatist, Fuller largely eschewed conceptual or semantic questions, focusing instead on questions of methodology and governance, in particular the adequacy of a scientific approach to understanding human society and the role played by agency and purpose in ordering civic life. In a phrase, Fuller faulted legal positivists for encouraging the kind of social engineering perspective reflected in bureaucratic/regulatory states. As he saw it, the importance of a pragmatic jurisprudence – and its superiority over other social sciences – lies precisely in the practical experience and concerns that lawyers possess (and other social scientists lack) and that they bring to bear in fashioning the participatory social architecture that is better at protecting human freedom.

Dennis Patterson argues in Chapter 29 that Dworkin’s critique of legal positivism, specifically Dworkin’s critique of Hart’s positivistic theory of law, went through two stages, first the critique put forward in Dworkin’s 1967 article ‘The Model of Rules’, which focused on the alleged inability of the rule of recognition to account for the existence of legal principles, and then the critique that found expression in Law’s Empire and concerned the theory’s alleged inability to account for the existence of theoretical disagreement in law. Patterson’s conclusion, however, is that, although Dworkin, in his mature critique, made a number of valid points, such as identifying the lack of a thought-out view on legal interpretation in Hart’s legal philosophy, he ultimately failed to undermine Hart’s theory. As Patterson sees it, although legal positivists lack a thought-out view of legal interpretation, there is nothing in the theory of legal positivism that stops them from developing such a theory, and he suggests three crucial criteria that a positivistic theory of legal interpretation must satisfy, namely, minimal mutilation of existing law, coherence and generality.

In Chapter 30, Veronica Rodriguez-Blanco clarifies and develops John Finnis’s objection to legal positivism in the shape of Hart’s theory, namely, that it is unstable because it utilises the notion of an internal point of view, which does not have sufficient discriminatory power to distinguish, as participants in the legal practice wish to do, between good and not so good legal norms, between rational and non-rational court decisions, and so forth. She explains that Finnis’s account of human action is superior to Hart’s because Finnis realises that understanding human action in law involves understanding the point of the action, and that such understanding requires the use of the Aristotelian focal meaning (or central case) methodology, which does have sufficient discriminatory power to distinguish between good and not so good norms, and so forth. The reason why theories of Hart’s general type are unstable, and theories of Finnis’s general type are not, she explains, is that the former, but not the latter, are unable to account for the causal link between mental state and action. Rodriguez-Blanco also argues that, as a result of the concentration in the past fifty years or so on the part of Anglophone legal philosophers on Dworkin’s critique of Hart’s legal positivism, legal philosophers have missed an opportunity to learn, through studying and debating Finnis’s critique of Hart’s theory, about the philosophy of practical reason and the theory of action; and that this in turn means that now they are not in as good a position as they might have been to contribute significantly to debates about normative questions and learn about the nature of law and its relation to agency, reasons for action and goodness.

Jan Sieckmann argues in Chapter 31 that the central claim of Robert Alexy’s critique of legal positivism is that there is a necessary connection between morality and the content of law, and that therefore the separation thesis is false; and he explains that whereas, in his earlier writings, Alexy adduced three distinct arguments in support of the connection thesis, namely, the argument from injustice, the argument from principles and the argument from the necessary claim of law to correctness, he has substituted in his later writings a more general argument from the dual nature of law for the three mentioned, more specific arguments. Having explained that Alexy situates his critique within the perspective of a participant, as distinguished from the perspective of an observer, Sieckmann goes on to maintain that Alexy has changed the focus of the debate about legal positivism from a primary concern with questions of legal validity to a more general concern with questions of the nature of law by emphasising that in addition to the usual classifying connections between morality, on the one hand, and legal systems, legal acts and legal norms, on the other, there are also qualifying connections. For, he explains, Alexy holds that whereas a (purported) legal system that does not raise a claim to correctness lacks legal character (the idea of a classifying connection), a legal system that raises but does not satisfy a claim to correctness, and individual legal acts and legal norms that do not raise a claim to correctness, or raise one that they do not satisfy, are legally defective (the idea of a qualifying connection). Sieckmann concludes that Alexy has shown that, for those who choose to adopt the perspective of a participant, legal positivism is not an adequate theory of law.