Introduction

Citizens’ Assemblies (CAs) are a specific form of deliberative mini-publics that are increasingly used to address complex policy challenges, especially in climate governance (Boswell, Dean, and Smith Reference John and Rikki Dean2023; Smith Reference Smith2024; Willis, Curato, and Smith, Reference Willis, Curato and Smith2022). They involve randomly selected citizens who deliberate and provide policy recommendations (Curato Reference Curato2021). However, their implementation and uptake largely depend on political parties and elites, which may perceive these novel instruments as challenging their authority (Elstub and Escobar Reference Elstub and Escobar2019; Setälä Reference Setälä2017). Given the growing use of deliberative mini-publics by representative institutions (Paulis et al. Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2021), research has explored their interaction with political parties (Gherghina Reference Gherghina2024; Gherghina, Soare, and Jacquet Reference Gherghina, Soare and Jacquet2020a).

This research follows two strands. The first examines how parties use internal deliberation to involve grassroots members, reform hierarchical structures, and adopt more horizontal decision-making models (Barberà and Rodríguez-Teruel Reference Barberà and Rodríguez-Teruel2020; Gherghina, Soare, and Jacquet Reference Gherghina, Soare and Jacquet2020b; Wolkenstein Reference Wolkenstein2018). The second focuses on parties’ external use of deliberation, exploring their role as initiators (Oross and Tap Reference Oross and Tap2021), commitments in electoral pledges (Gherghina and Mitru Reference Gherghina and Mitru2024), and officials’ support for citizens’ assemblies (Gherghina, Close, and Carman Reference Gherghina, Close and Carman2023; Jacquet, Niessen, and Reuchamps Reference Jacquet, Niessen and Reuchamps2022; Rangoni, Bedock, and Talukder Reference Rangoni, Bedock and Talukder2023). Studies also analyze the political uptake of assembly recommendations (Fournier et al. Reference Fournier, Van Der Kolk, Carty, Blais and Rose2011; Galván Labrador and Zografos Reference Galván Labrador and Zografos2024; Minsart and Jacquet Reference Minsart, Jacquet, Reuchamps, Vrydagh and Welp2023). Beyond normative motivations—such as enhancing legitimacy or strengthening citizen engagement—this literature highlights two main factors shaping parties’ stance on citizens’ assemblies: ideology and electoral competition (Becerril-Viera, Ganuza, and Motos Reference Viera, Isabel and Motos2024; Font, Galais, and Motos Reference Font, Galais and Rico2024; Font and Motos Reference Font and Motos2023). Regarding ideology, as they historically advocate inclusivity, equality, and collective decision making, progressive left-wing and Green parties tend to be more supportive, promoting citizens’ assemblies, particularly on climate policy, a primary issue for parties on this side of the political spectrum. Regarding electoral competition, traditional governing parties, deeply rooted in representative democracy and benefiting from the status quo, are often more reluctant, as participatory mechanisms could weaken their control over policy making. In contrast, opposition parties, especially those structurally accustomed to electoral losses, are more likely to support citizens’ assemblies because they redistribute decision-making power to citizens and challenge incumbents.

Despite research on parties and deliberation, little is known about how electoral and ideological factors influence real-world deliberative processes. This article addresses this gap by analyzing parties’ engagement with a citizens’ assembly on climate organized in Luxembourg in 2022 (Klima Biergerrot—KBR). After describing Luxembourg’s context and the KBR, it examines parties’ involvement before, during, and after the climate assembly (up to the 2023 national election), highlighting the complex interplay between citizens’ assemblies and party politics.

The Case of Luxembourg

Luxembourg provides a unique context for studying party responses to a citizens’ assembly, particularly on climate issues. Unlike neighboring countries, the KBR was Luxembourg’s first major deliberative initiative (Paulis, Kies, and Verhasselt Reference Paulis, Kies and Verhasselt2024). This reflects Luxembourg’s historically stable political system, dominated by three traditional parties: the Christian Social People’s Party (CSV), the Democratic Party (DP), and the Luxembourg Socialist Workers’ Party (LSAP). High trust in representative institutions, small-state dynamics (population: 560,000), and strong economic performance have limited structural incentives for participatory procedures.

Luxembourg’s demographics complicate the picture, with 40% of residents being nonnationals, who are excluded from national elections yet affected by policies.Footnote 1 Their inclusion has fueled integration debates, which provided fertile ground for newer left-wing parties (the Greens and the Left) and populist right-wing parties (Alternative Democratic Reform—ADR) since the 1980s. Tensions peaked during the 2015 referendum on nonnational voting rights, initiated by Luxembourg’s first-ever three-party, progressive coalition government (DP, LSAP, and the Greens) and where conservative opposition from the CSV and populist ADR reflected deep societal divides (De Jonge and Petry Reference De Jonge, Petry and Smith2021). Citizens’ assemblies could thus foster inclusiveness but risk deepening ideological conflicts on this matter.

As a high-polluting country,Footnote 2 Luxembourg faces pressure for stringent climate action. Following the Greens’ 2018 gains, the three-party coalition (DP, LSAP, and Greens) was reconducted and prioritized climate policy, eventually further polarizing the parties over a climate assembly’s outcomes, especially near elections.

The Klima Biergerrot

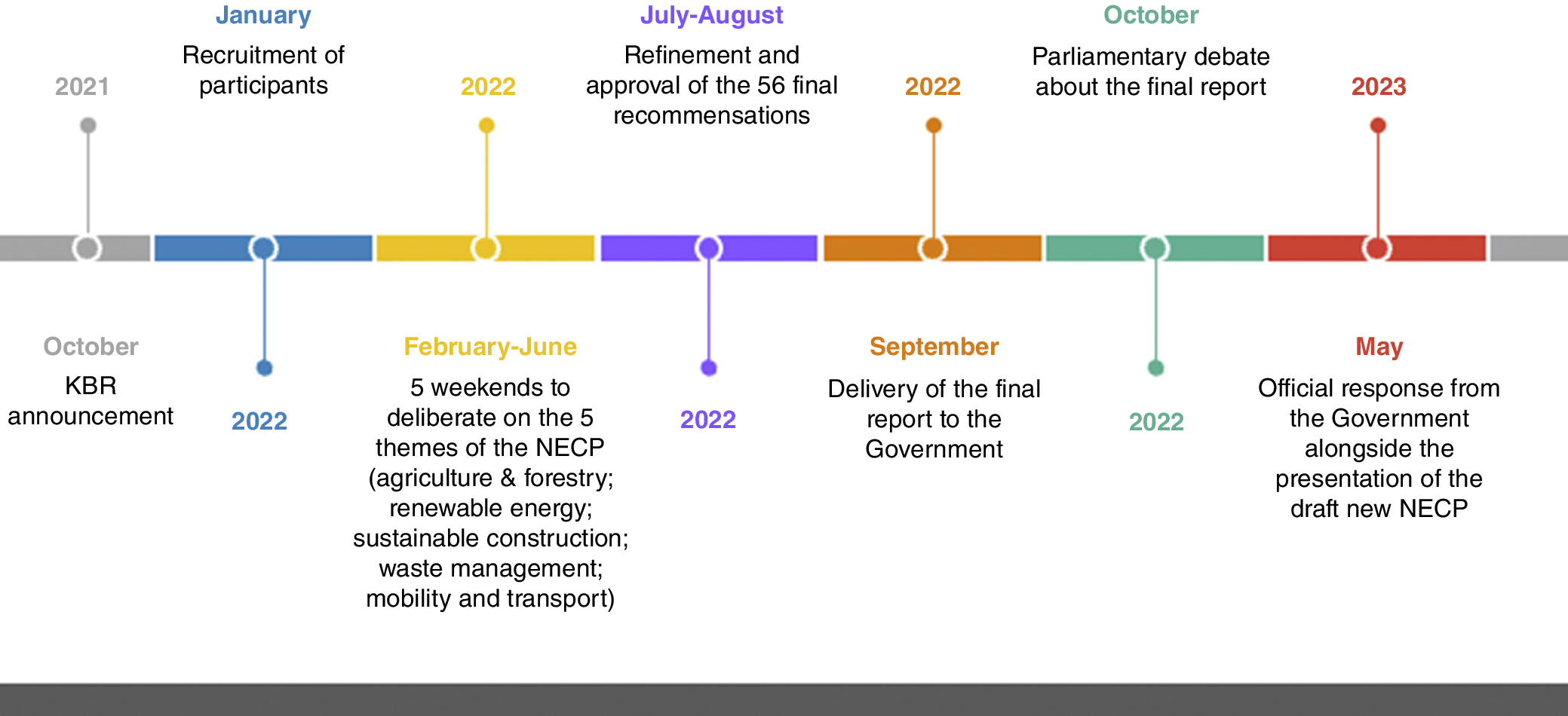

The KBR, commissioned by the Luxembourg Government, was held over eight months in 2022 (Figure 1). The deliberation phases involved five weekends (February-June), followed by a decision-making phase (July–August) to refine and approve 56 recommendations. It gathered 100 participants, including national citizens, nonnational residents, and cross-border workers, to assess current climate commitments and propose measures for the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). The final report was submitted in September, debated in parliament in October, and received an official government response alongside the draft NECP presentation in May 2023.Footnote 3

Figure 1 Deliberation Phases of the Klima Biergerrot

Of the 56 proposals, which align with mitigation strategies from other European climate assemblies (Lage et al. Reference Jonas, Thema, Zell-Ziegler, Best, Cordroch and Frauke2023), five resulted in new NECP measures and 19 reinforced existing ones, demonstrating policy impact. Flagship measures, such as increasing the CO2 tax, limiting livestock, reducing speed limits, and cutting fossil fuel subsidies, gained media and parliamentary attention due to their economic and social implications. The speed limit reduction measure was properly implemented in 2024 but is still debated (Chauty Reference Chauty2024).

Political Parties’ Reactions to the KBR

Before the Deliberative Process: The Calm before the Storm?

The Liberal Prime Minister’s announcement of the KBR in October 2021 elicited little reaction from other parties. Instead, civil society voiced skepticism in the media about the climate assembly’s effectiveness and its alignment with existing stakeholder bargaining structures (Klein Reference Klein2021).

During the deliberative process: A government/opposition game

Despite a limited communication strategy to avoid influence (Paulis, Kies, and Verhasselt Reference Paulis, Kies and Verhasselt2024), KBR’s media attention grew in June 2022 before the last deliberation weekend. Based on anonymous witnesses, a newspaper criticized the lack of transparency in procedural choices (agenda and schedule, participant recruitment, and expert selection; Brucker Reference Brucker2022), prompting the main opposition party, the conservative CSV, to echo these concerns in a parliamentary question.Footnote 4 The government clarified that recruitment and facilitation were outsourced to professionals and that the anonymous witnesses’ statements reported in the media were unrepresentative of assembly members.

This sequence underscores opposition-government dynamics, as the CSV challenged an initiative framed as pro-government. Although this may contradict the theory supposing opposition parties to be more favorable to citizens’ assembly, the CSV was in opposition for the first time since 1945, being historically a winning party with little interest in altering the status quo. Meanwhile, the Greens, usually in opposition and for the first time in power, had a chance to push for their participatory agenda. Moreover, discrediting the DP, the CSV’s longtime coalition partner, was a strategic move, as the DP had allied with left-wing parties to sideline the CSV in previous elections. Thus, both short- and long-term electoral dynamics help explain parties’ reactions to this deliberative process.

Postprocess parliamentary debate: Parties show their cards

Once the report was delivered to the government, parliamentary debateFootnote 5 focused more on policy recommendations rather than the procedure itself. It revealed ideological divisions, especially between conservative and progressive parties. The populist ADR dismissed all proposals as aligning with the Greens’ agenda. The CSV criticized again the assembly’s composition, specifically the underrepresentation of farmers’ interests, which the party traditionally defends. They opposed proposals that affected agriculture and rejected increasing the CO2 tax, citing the financial strain on car-dependent citizens. In contrast, all the progressive parties (DP, LSAP, Greens, Left, and Pirates) supported the outcomes, although the LSAP was more reserved. While acknowledging that some proposals could be quickly implemented, the LSAP noted that others required EU-level action. Like the CSV, they questioned the feasibility of the CO2 pricing model due to its financial effects on citizens. The motion to integrate KBR proposals into the NECP passed with 33 votes (DP, Greens, LSAP, Left); 21 CSV MPs abstained, and the ADR and Pirates voted against it. This debate shows the importance of the issue at stake and how ideological preferences may particularly condition the parties’ reception of the proposals made by a citizens’ assembly.

Furthermore, recentering the discussion on the procedural aspects, the Pirates and the Left called for more radical democratic reforms and the installation of a permanent citizens’ council, a proposal previously introduced by the Pirates in 2019. This shows again how structurally losing parties are generally ready to change the status quo.

Postprocess elections: Game changer or flogging a dead horse?

The 2023 national election was a test case to measure the KBR’s influence on party stances regarding citizens’ assemblies, with 2018 serving as a comparison. The incumbent GreensFootnote 6 and DPFootnote 7 manifestos directly referenced it, advocating for a permanent climate assembly. As in the KBR’s parliamentary debate, the PiratesFootnote 8 supported the implementation of a permanent citizens’ assembly, but they did not limit it to climate policy making. Although these three parties promoted referendums in 2018, they shifted to citizens’ assemblies in 2023. The LeftFootnote 9 strongly supported citizen participation in both the 2018 and 2023 programs, particularly on climate and urban planning, but the party provided limited insight on the format. Their parliamentary discourse, however, indicates a stronger commitment to citizens’ assemblies. The incumbent LSAPFootnote 10 also moved from supporting referenda in 2018 to citizens’ assemblies in 2023 yet emphasizing that they should be consultative and not replace representative decision making, maintaining a strong commitment to representative democracy as a historical “winning party.” In contrast, the CSVFootnote 11 remained silent on citizen participation in both election programs, indirectly underscoring their strong attachment to the status quo. The ADRFootnote 12 continuously supported binding referendums on core issues like security and immigration. Overall, the campaign revealed ideological divides, with progressive parties embracing citizens’ assemblies and the conservative right remaining skeptical.

The CSV’s 2023 landslide victory and the Greens’ heavy losses altered prospects for the replication of citizens’ assemblies, which was recommended by the KBR members and broadly accepted by the Luxembourg population (Paulis, Kies, and Verhasselt Reference Paulis, Kies and Verhasselt2024). The coalition agreement between the CSV and DP pledged to “pursue a climate policy that involves citizens in major decisions,”Footnote 13 referencing the KBR’s learnings, likely due to DP’s influence. However, the CSV’s dominance in the government casts doubt and, when the former Green Environment Minister questioned the new government’s stance on citizens’ assemblies,Footnote 14 the new CSV PM reaffirmed a preference for traditional participatory channels like elections and petitions, stating “no intention to implement an institutionalized procedure of citizen deliberation at the national level” and thus signaling limited prospects for future citizens’ assemblies.

Conclusion

This article investigated the interplay between political parties and deliberative processes through the case of a citizens’ assembly on climate in Luxembourg (Klima Biergerrot–KBR). Despite the specificities of the Luxembourgish context and the limitations of desk research to further analyze the motives behind parties’ reactions, our study yields insights into the role of ideology and electoral competition in shaping parties’ engagement with a deliberative process.

Our study yields insights into the role of ideology and electoral competition in shaping parties’ engagement with a deliberative process.

Opposition-government dynamics primarily shaped reactions to procedural aspects, with the main opposition party, CSV, questioning the legitimacy of what they framed as a pro-government initiative. Although opposition parties often support democratic alternatives, CSV—Luxembourg’s largest party—was unusually relegated to opposition when the KBR took place. They used this status to challenge an initiative led by newly empowered parties (the Greens) or former allies that distanced themselves (the DP). Similar strategies by conservative opposition parties against progressive-led participatory processes have been observed in Spain (Viera, Ganuza, and Motos Reference Viera, Isabel and Motos2024). More broadly, attachment to representative democracy—often emphasized by CSV—has driven political resistance to citizens’ assemblies across various contexts (Rangoni, Bedock, and Talukder Reference Rangoni, Bedock and Talukder2023). For the DP—and to a lesser extent, the LSAP—support for citizens’ assemblies may align with trends found for example among certain German traditional parties, which embrace deliberative procedures that maintain party dominance in decision-making (Gherghina, Geissel, and Henger Reference Gherghina, Brigitte and Fabian2024). Meanwhile, consistent with previous findings, smaller opposition parties like the Left and Pirates strongly supported citizens’ assemblies, while the populist right rejected them, favoring referendums instead (Gherghina and Mitru Reference Gherghina and Mitru2024).

Ideological divisions shaped reactions to the KBR’s climate policy recommendations. The DP and Greens, alongside smaller progressive parties (the Left and Pirates), praised the citizens’ proposals, reaffirming their commitment to climate action. As ruling parties, the DP and Greens ensured that the recommendations received political consideration, an often-missing ingredient in other climate assemblies (Galván Labrador and Zografos 2024). Conversely, conservative parties (CSV and ADR) criticized the proposals that clashed with their ideological preferences. Although reaffirming the attachment to the status quo after the process and during the following campaign, the CSV’s victory in the 2023 election raises doubts about the future of citizens’ assemblies under the new government and the broader trajectory of climate policy, which remains a lower priority. This also raises a broader question: Would conservative parties have responded differently (and perhaps more positively) if the assembly had addressed an issue more aligned with their priorities? Future research should explore this across different contexts and policy areas.

FUNDING

This article is based on work from the COST Action CA22149 Research Network for Interdisciplinary Studies of Transhistorical Deliberative Democracy (CHANGECODE), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.