Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) represents the concept by which companies consciously and willingly invest their effort in activities that go beyond the primary focus of their business and positively influence social and natural environment. The concept of socially responsible business became a conventional practice in contemporary business endeavors, because all the involved parties significantly benefit from it. Nowadays, social responsibility implies the management's obligation to undertake certain activities contributing to the improvement of the business system of the company as well as bringing a long-lasting benefit to the stakeholders and society as a whole (Jamali, El Dirani, & Harwood, Reference Jamali, El Dirani and Harwood2015; Nazari, Hrazdil, & Mahmoudian, Reference Nazari, Hrazdil and Mahmoudian2017).

Despite the continuous interests of researchers for a comprehensive explication, the CSR concept still lacks a precise definition and clearly identified dimensions (Carroll, Reference Carroll2016; Dahlsrud, Reference Dahlsrud2008; Mueller, Hattrup, Spiess, & Lin-Hi, Reference Mueller, Hattrup, Spiess and Lin-Hi2012). Essentially, most CSR definitions presuppose companies' engagement beyond legal obligations with the aim of diminishing the negative impact and improving general conditions of the society and the environment in which it operates (McWilliams, Siegel, & Wright, Reference McWilliams, Siegel and Wright2006). More recent definitions even place CSR in the center of a company's strategy incorporating vital stakeholders' interests and providing measurable performances achieved through sustainable investments and strong environmental and social practices (Manasakis, Reference Manasakis2018; Mullerat, Reference Mullerat2013).

Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2006) defines CSR as a consideration of the internal and external stakeholders of the company in an ethical and socially responsible way (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2006). Conflicting needs of stakeholders and other global economic factors affect the company and result in a higher level of companies' involvement in CSR activities (Kudłak, Szocs, Krumay, & Martinuzzi, Reference Kudłak, Szocs, Krumay and Martinuzzi2018). Stakeholders put constant pressure on companies to define measures and demonstrate the influence of their business on the surroundings (Seroka-Stolka, Reference Seroka-Stolka2016). On the contrary, CSR is a powerful tool that companies can use to shape the stakeholders' opinions and behavior. Managers try to increase the knowledge of how and under which conditions CSR activities will achieve benefits and a competitive advantage for the company, but also how CSR activities should be communicated to stakeholders in order to attain the aforementioned results. Consequently, more attention from researchers and practitioners is being paid to CSR effectiveness concerning stakeholders (Brunton, Eweje, & Taskin, Reference Brunton, Eweje and Taskin2017; Cherian & Pech, Reference Cherian and Pech2017; Costa & Menichini, Reference Costa and Menichini2013; Rivera, Bigne, & Curras-Perez, Reference Rivera, Bigne and Curras-Perez2016).

Although there is a growing number of research studies on CSR concept as a global phenomenon, there are some research gaps that leave room for further investigation in this field. There is the evident lack of research on CSR in post-socialist countries, especially of comparative type. Comparative research must include differences in cultures and business cultures (Golob & Bartlett, Reference Golob and Bartlett2007; Jackson & Bartosch, Reference Jackson and Bartosch2016; Ling, Reference Ling2019) as an important parameter of analysis, since national culture values have significant impact on the attitudes on the organizational culture and values, even stronger than demographic characteristics (Taras, Steel, & Kirkman, Reference Taras, Steel and Kirkman2011). The aim of this research is to address this issue and point to possible differences in the perception of employees regarding the CSR in business cultures in Russia, Bulgaria and Serbia. For this purpose, the quantitative research was carried out. The data were collected during the period from 2017 to 2018, using a structured questionnaire, to determine the level of awareness and attitudes of employees about the implementation of CSR activities in the companies they work for.

Many studies dealt with CSR in large companies while the CSR in the context of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) had been given less attention. The proposed approach for the assessment of CSR takes employees from companies of different sizes belonging to different countries into account. This paper proposes multi-dimensional concepts that require the identification of a number of criteria and their weights in order to consider important CSR aspects and prioritize the observed alternatives. The study uses the five-dimensional approach to CSR, based on the Dahlsrud's study that refers to the environmental, social, economic, stakeholder and voluntariness dimension (Dahlsrud, Reference Dahlsrud2008). Through the comparison of different cultural contexts, the present paper offers valuable implications for further development and implementation of the concept in the observed countries. Besides scholars considering a new approach in understanding and presenting the CSR, additional merit of this research can be found in generalized knowledge possibly useful to company managers or for the countries' governments aiming to make proper decisions regarding the CSR concept.

The paper is structured as follows. After the Introduction section, an extensive literature review is provided in the next section with special attention devoted to a cross-cultural analysis of the researched countries and five CSR dimensions. In the section – ‘Methodology,’ the implemented procedure is thoroughly explained. The results of the study are presented in the section ‘Results’ and ‘Discussion’ section underscores the most important findings of the paper. The paper finishes with the section ‘Conclusion,’ which underlines some important comparisons, limitations and future research directions.

Literature review

Although some of the stakeholders support the approach that the company has the responsibility for fulfilling its principal goal only – profit, and any further engagement represents a useless waste of resources (Friedman, Reference Friedman1970), other stakeholders' viewpoint is that a company has the obligation to take care of other interests, not just the ones of shareholders (Kudłak et al., Reference Kudłak, Szocs, Krumay and Martinuzzi2018; Tian, Liu, & Fan, Reference Tian, Liu and Fan2015; Yu & Choi, Reference Yu and Choi2016; Zhang, Oo, & Lim, Reference Zhang, Oo and Lim2019). Although the scientific interest for CSR is rapidly growing, scarcely was research conducted with a purpose of comparing the attitudes of certain stakeholder groups, especially employees (Dawkins, Jamali, Karam, Lin, & Zhao, Reference Dawkins, Jamali, Karam, Lin and Zhao2014; Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Hattrup, Spiess and Lin-Hi2012). Companies that implement CSR activities can have significant benefits directly reflected in the enhancement of corporate reputation, increasing user satisfaction and competitive advantage, while indirectly affecting the increase in sales, profits and other performance (Ghosh, Reference Ghosh2017; Park, Reference Park2019; Saeidi, Sofian, Saeidi, Saeidi, & Alireza Saaeidi, Reference Saeidi, Sofian, Saeidi, Saeidi and Alireza Saaeidi2015). Furthermore, the activities the company undertakes have a strong positive impact on employees since they identify with company's values and their satisfaction with work and performance is likewise improved (Ali, Ur Rehman, Ali, Yousaf, & Zia, Reference Ali, Ur Rehman, Ali, Yousaf and Zia2010; Brammer, Millington, & Rayton, Reference Brammer, Millington and Rayton2007; Gürlek & Tuna, Reference Gürlek and Tuna2019). Previous research showed that organizational culture, including authentic organizational values, kept the unity of the organization via the manifestation of the typical organizational behavior, shared values and internal integration (Brunton, Eweje, & Taskin, Reference Brunton, Eweje and Taskin2017). Hence, it is important for companies to evaluate the internal results of their own CSR activities, as well as the impact on the surroundings.

The review of literature carried out by Dos (Reference Dos2017) revealed that few studies had considered assessing the attitudes of stakeholders on CSR where the size of a company is taken as the parameter of distinction. The research mainly dealt with the ranking of large companies (Ebrahimi, Zohrei, & Emadi, Reference Ebrahimi, Zohrei and Emadi2014; Lamata, Liern, & Pérez-Gladish, Reference Lamata, Liern and Pérez-Gladish2016). The size of the company is very important in studying CSR because, unlike large companies, SMEs define, implement and monitor CSR practices differently, but also evaluate and report on them to a lesser degree (Stojanović, Mihajlović, & Schulte, Reference Stojanović, Mihajlović, Schulte and Mihajlović2016). Large companies are prevalently conscious of the importance of building strong relationships with the society and CSR is integrated in their business and communication strategies promoting ethical and human values and favorable business practice (Perrini, Russo, & Tencati, Reference Perrini, Russo and Tencati2007). Large companies, also, have more resources to invest in their surroundings and they tend to make stronger influence on economy and society.

However, the growing importance of SMEs for national and local economies shifts the focus of CSR to this area, as well. Adoption of the CSR practice in SMEs is generally based only on the compliance with legislation and regulations, considering limited resources and impossibility to create significant benefits from the CSR practice. On the contrary, some research studies showed that proactive CSR implemented in SMEs enables the overcoming of the lack of resources and obtaining direct benefits from responsible practice (Aragon-Correa, Hurtado-Torres, Sharma, & Garcia-Morales, Reference Aragon-Correa, Hurtado-Torres, Sharma and Garcia-Morales2008; Santos, Reference Santos2011). Although SMEs can benefit from socially responsible investments in local community and vicinity, previous research showed lagging in the engagement of SMEs in comparison with large companies (Perrini, Russo, & Tencati, Reference Perrini, Russo and Tencati2007).

Cross-cultural analysis

When it comes to comparative research on CSR conducted abroad, there are several directions. One group of comparative research studies relates to the comparison of legislation and institutional analysis of CSR strategies in different corporate governance systems, such as the Anglo-American and Continental European approach (Matten & Moon, Reference Matten and Moon2008). The second group of research studies deals with similar cases, that is, with the investigation of differences in CSR approach in states with similar socio-political traditions (Williams & Aguilera, Reference Williams, Aguilera, Crane, Matten, McWilliams, Moon and Siegel2008). The extensive comparative investigation considering stakeholders', especially employees', opinions measurement and comparison from several states is rarely presented in the literature (Chaudhary, Reference Chaudhary2017; Dawkins et al., Reference Dawkins, Jamali, Karam, Lin and Zhao2014).

Although the CSR is a global phenomenon, national context and cultural heritage notably influence the manner in which the CSR is implemented in certain countries (Crotty, Reference Crotty2016; Halme, Roome, & Dobers, Reference Halme, Roome and Dobers2009). A socially responsible business should imply a unique system of values and principles, respecting basic responsibilities, regardless of the place of operation. However, the companies are facing various national and local issues and their actions should support the specific needs of the society and its surroundings. The countries covered by the current study (Russia, Bulgaria and Serbia) provide a wide observation frame taking the cultural perspective of former socialist states into account, which are, at present, at a different level of economic development. All three countries have gone through major political, economic and social changes in the last 20 years.

Although in Western business cultures CSR has developed as a well-planned part of strategic management and marketing (Morozova & Britvin, Reference Morozova and Britvin2013), with the process of establishing socialist policy in Russia social responsibility obtained specific features. During the Soviet Union period, the entrepreneurial activity was almost non-existent and companies were managed by the state. Solving social problems was the obligation of the state, where business entities were just the intermediaries for fulfilling government demands. With the change of the system and opening Russia to the global market, the situation has significantly changed. Russian society started to alter its ways and got involved in solving social problems expecting a certain level of business righteousness from business entities. Another very important trigger for the responsible behavior of Russian companies is the internationalization of business. If they want to do business on the international market, Russian companies need to adopt CSR as a practice that provides stable business relationships enhancing unfavorable business reputation. Therefore, CSR in Russia has developed in a way that integrates the form of social responsibility and inherited values, current social establishment and international, socially responsible principles.

In recent years, the European Union (EU) has become a leader in acceptance and application of CSR. Although CSR has attracted a lot of attention in the EU, numerous regulations have been put forward and many initiatives introduced. Essentially, voluntary acceptance of measures and taking responsibilities is still being emphasized (Mullerat, Reference Mullerat2013).

CSR in Bulgaria is a relatively new concept introduced as a part of the EU integration and under the influence of foreign multinational companies. In the period prior to the transition, in Bulgaria, CSR activities were implemented as a part of social and environmental norms that regulate working conditions, relationships between economic entities and environmental protection (Matev, Gospodinova, Peev, & Yordanov, Reference Matev, Gospodinova, Peev and Yordanov2009). The analysis of the latest CSR manifestations of the Bulgarian business has shown the evolution from a traditional chaotic model of charity to social investment (Antonova, Stoycheva, Kunev, & Kostadinova, Reference Antonova, Stoycheva, Kunev and Kostadinova2018). In the practice of domestic enterprises, there is no systematized CSR implementation, yet certain activities have been implemented since the importance of CSR's impact on a company's competitiveness and the increased stakeholder confidence has already been taken into account (Kunev, Kostadinova, & Stoycheva, Reference Kunev, Kostadinova and Stoycheva2017; Matev et al., Reference Matev, Gospodinova, Peev and Yordanov2009). Although the government and companies promote socially responsible behavior, great distrust is still present pertaining to the company's sincere intentions in implementing CSR activities and prejudice related to the benefits of applying socially responsible practice (Lyubenova, Reference Lyubenova2014).

Although the concept of CSR in developed economies has existed for decades, in most companies in Serbia this concept is still in development. Serbia is a candidate for the EU membership and is currently facing numerous challenges related to new market principles and requirements set by the EU. Serbia has to tackle with specific economic heritage and an unfavorable reputation arising from economic sanctions and reduced business activity in the 1990s. The CSR concept appeared after the year 2000, in response to the aforementioned problems and increased public pressure, but also because of the need to fulfill the requirements demanded of Serbia as a candidate state for the EU membership. Moreover, the arrival of foreign companies further contributed to the popularization of this concept in Serbia. Declarative devotion of the institutions to improve the CSR environment is indicative in recent years, but the consistent implementation is still missing. The attitude of the stakeholders toward the socially responsible behavior of companies remains distrustful in Serbia (Simic-Antonijevic, Vojnovic, & Grujic, Reference Simic-Antonijevic, Vojnovic and Grujic2015). By examining the current state of the CSR, the study pointed out that companies still had insufficient awareness and knowledge of the benefits of socially responsible business, because they perceived it as activities that required the investment of financial resources making no profit. The engagement of the companies is primarily focused on activities that attract the attention of the media and the community (Ivanović-Đukić, Reference Ivanović-Đukić2011).

After considering the current situation in Russia, Bulgaria and Serbia, having predominantly the previous research results in mind, it seems evident that the level of CSR development in companies and enterprises, as well as its elaboration in scientific papers, leaves enough room for significant improvement. Weak institutional and legal framework and deficiency of standards represent an important challenge for CSR introduction and implementation in companies belonging to the countries in question (Arevalo & Aravind, Reference Arevalo and Aravind2011). Companies operating in these countries apply CSR in accordance with the current level of awareness regarding the usefulness and importance of CSR inclusion in business.

CSR dimensions

In one of the attempts to formulate a unique definition of CSR, Dahlsrud (Reference Dahlsrud2008) underscored five key dimensions: environmental, social, economic, stakeholder and voluntariness dimension, which define CSR with exceptional comprehensiveness, because 97% of the definitions include at least three of these five dimensions (Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Hattrup, Spiess and Lin-Hi2012). After carefully studying the aspects of corporate responsibility (Hanzaee & Rahpeima, Reference Hanzaee and Rahpeima2013), it was concluded that these five dimensions integrated the relevant priorities and set goals for the implementation of the CSR concept in the best way (Slack, Brandon-Jones, & Johnston, Reference Slack, Brandon-Jones and Johnston2013). The definition of the European Commission, one of the most widely accepted ones, also mentions these five dimensions of CSR as a ‘Concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis’ (European Commission, 2001: 8).

The key areas of CSR activity are generated in order to overcome difficulties in meeting socially responsible intentions. One must bear in mind that not every company can implement all CSR activities across every domain, thus theorists and practitioners are trying to develop and perfect the models for the ideal choice and implementation of the CSR in order to achieve pre-defined economic and social goals. In other words, companies must define areas to which they want to direct their efforts, for example, deciding whether to increase general wealth through activities focused on the social dimension of CSR, to reduce the negative ecological influence by directing activities toward the environmental dimension, to improve business and work environment through the economic dimension or, to establish quality relations with stakeholders, simultaneously bearing in mind that all the aforementioned should be voluntary far beyond mere regulation adherence.

The environmentally responsible behavior of the company has the goal of preventing, responding to and reducing the impact of production on natural environment. Environmental management can be implemented through the optimization of processes, products and services, conservation of raw materials, energy usage and reduction of pollution (Hens et al., Reference Hens, Block, Cabello-Eras, Sagastume-Gutierez, Garcia-Lorenzo, Chamorro and Vandecasteele2018; Pimenta & Gouvinhas, Reference Pimenta and Gouvinhas2011). Even greater proactive environmental concerns can be achieved through focusing on innovations, cleaner production, green products, eco-efficiency and eco-leadership (Alt, Díez-de-Castro, & Lloréns-Montes, Reference Alt, Díez-de-Castro and Lloréns-Montes2015; Buysse & Verbeke, Reference Buysse and Verbeke2003). The ability of companies to increase their competitive position by implementing socially responsible activities in the field of environmental protection depends on available resources, capabilities of the management, the industrial sector and normative regulations. This approach suggests that companies should focus on sustainability trough reducing expenses by decreasing environmental risks, improving the relationship with consumers based on the eco-friendly image, and achieving financial results in the long run (Fijałkowska, Zyznarska-Dworczak, & Garsztka, Reference Fijałkowska, Zyznarska-Dworczak and Garsztka2018).

Adding responsibility to society in existing financial circumstances provides benefits both to the company and the community. In order to successfully nurture CSR's social dimension, the company's management should establish a balance between numerous, often opposed, stakeholder demands (Calabrese, Costa, Menichini, & Rosati, Reference Calabrese, Costa, Menichini and Rosati2013). Allocating the company's resources to solving social problems reduces tensions and conflicts between the company and the environment. On the one hand, by improving social well-being the company provides support for its activities and business. On the other hand, placing a positive image of responsible engagement ensures a competitive position and better economic performance resulting from more favorable social performance. In this way, a valuable basis for the long-term sustainability of a business is provided (Margolis & Walsh, Reference Margolis and Walsh2003).

The economic dimension refers to the adequate management of a business that establishes the balance between financial results, ethical and living standards. Within this dimension there is the obligation of producing quality goods and services, as well as initiating technological progress and innovation with the aim of creating new values for consumers while achieving economic unity of the society. The economic responsibility is predominant (Carroll, Reference Carroll2016), and responsibilities incorporated by other dimensions cannot be attained without it.

Freeman's (Reference Freeman1984) Stakeholder theory suggests that in order to effectively address problems relating to the creation of values, ethics and governance, it is necessary to analyze relations with all groups that influence or are under the influence of business (Parmar, Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Purnell, & De Colle, Reference Parmar, Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Purnell and De Colle2010). Communication and commitment to building positive relationships with all stakeholders and continual adaptation to a changing environment are required for the success of this business concept. The stakeholder theory is omnipresent in academic and corporate circles, explaining the way companies conduct and monitor stakeholder management, so the results of interaction are beneficial to business and non-business sides (Carroll, Reference Carroll2015; Thao, Anh, & Velencei, Reference Thao, Anh and Velencei2019). Managing a company based on the principles of the stakeholder concept of CSR implementation implies looking for solutions which do not require a trade-off between stakeholder interests, yet they rather focus on satisfying everyone.

Companies operating today voluntarily include additional activities into their business to operate in a socially, economically and environmentally-oriented manner. Although the prescribed rules and standards regulate a part of relevant activities, related to the aforementioned areas, a large part of the company's responsible activities is carried out on its own initiative and is much more than simply obeying the rules. The voluntariness dimension reflects the values and ethical aspirations of the company's management toward philanthropic contribution, respect for society and prevention of social damage. The verification of CSR implementation results still lacks in clear and satisfying frames; performance indicators are diverse and the reliability of measuring voluntary engagement is fairly low (Jamali, Reference Jamali2008).

Methodology

Since the success of CSR activities is closely dependent on the simultaneous implementation of a larger number of activities, deciding and selecting the most adequate actions involves making decisions with a synchronized monitoring of numerous criteria. For this reason, the multi-criteria decision-making approach and tools, as well as different hybrid models were used in previous papers to increase rationality in decision making (Wang, Yang, & Lin, Reference Wang, Yang and Lin2015), for the evaluation of CSR dimensions (García-Melón, Pérez Gladish, Gómez-Navarro, & Méndez Rodriguez, Reference García-Melón, Pérez Gladish, Gómez-Navarro and Méndez Rodriguez2016; Menichini & Rosati, Reference Menichini and Rosati2014; Petrillo, De Felice, García-Melón, & Pérez-Gladish, Reference Petrillo, De Felice, García-Melón and Pérez-Gladish2016; Slapikaite, Reference Slapikaite2016), or for the ranking of companies (Ebrahimi, Zohrei, & Emadi, Reference Ebrahimi, Zohrei and Emadi2014; Lamata, Liern, & Pérez-Gladish, Reference Lamata, Liern and Pérez-Gladish2016).

In this paper, the integrated multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) methodology of Entropy-PROMETHEE-GAIA was applied in a way not previously available in the literature pertaining to the CSR. This approach was developed due to the need for differentiating the levels of perception instead of detecting the relations among examined elements resulting from using statistical methods.

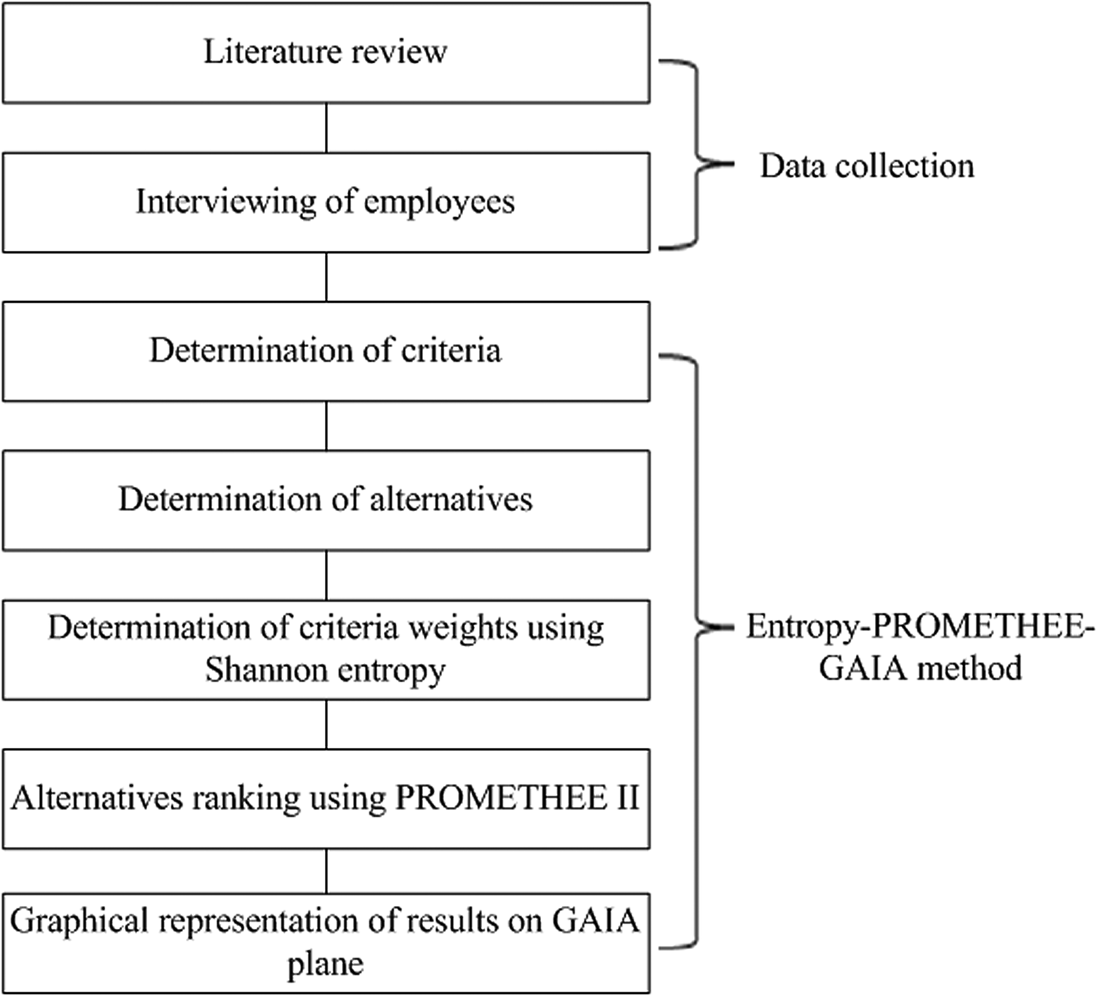

The research methodology and application of the integrated MCDA approach, proposed in this paper consists of several phases presented in Figure 1. A comprehensive literature review represented the first phase of the research in order to define the basic elements of CSR and the measurement scale for assessing the respondents' opinions. The second phase consisted of collecting the data by interviewing the employees working in small-, medium-sized and large companies. The next three phases represented the steps in performing the proposed methodology by defining the criteria based on the statistical analysis of the collected data, determination of alternatives using various descriptive variables, and estimation of criteria weights using Shannon entropy (Anthony, Behnoee, Hassanpour, & Pamucar, Reference Anthony, Behnoee, Hassanpour and Pamucar2019; Hassanpour & Pamučar, Reference Hassanpour and Pamučar2019). The last two phases included the implementation of PROMETHEE II and GAIA methods for the final ranking of small, medium-sized and large companies and graphical representation of results.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the proposed approach.

The questionnaire was applied as a research instrument for obtaining the opinion of employees. The questions were developed and structured based on the existing literature and adapted to the needs of the research (Fortier, Reference Fortier2013; Gallardo-Vázquez & Sanchez-Hernandez, Reference Gallardo-Vázquez and Sanchez-Hernandez2014; Madueño, Jorge, Conesa, & Martínez-Martíneza, Reference Madueño, Jorge, Conesa and Martínez-Martíneza2016; Turker, Reference Turker2009). The survey was carried out during the period from 2017 to 2018, when the same standardized questionnaire was translated into the native languages of the countries participating in the research, and distributed to the respondents. In order to accomplish a high level of question comprehension, the respondents were mostly interviewed in person while a smaller number of questionnaires was distributed online. In this way, the high response rate with completely and properly fulfilled questionnaires was achieved. The interviews were conducted anonymously, without the respondents naming the company they work for, so they could freely and objectively estimate given statements, without facing the potential pressure from the managers. A research collaborator from each country was responsible for collecting a similar number of surveys, so that the results could be adequately compared and analyzed. The sample was very heterogeneous containing the answers of employees from different types and sizes of companies, as well as different job positions.

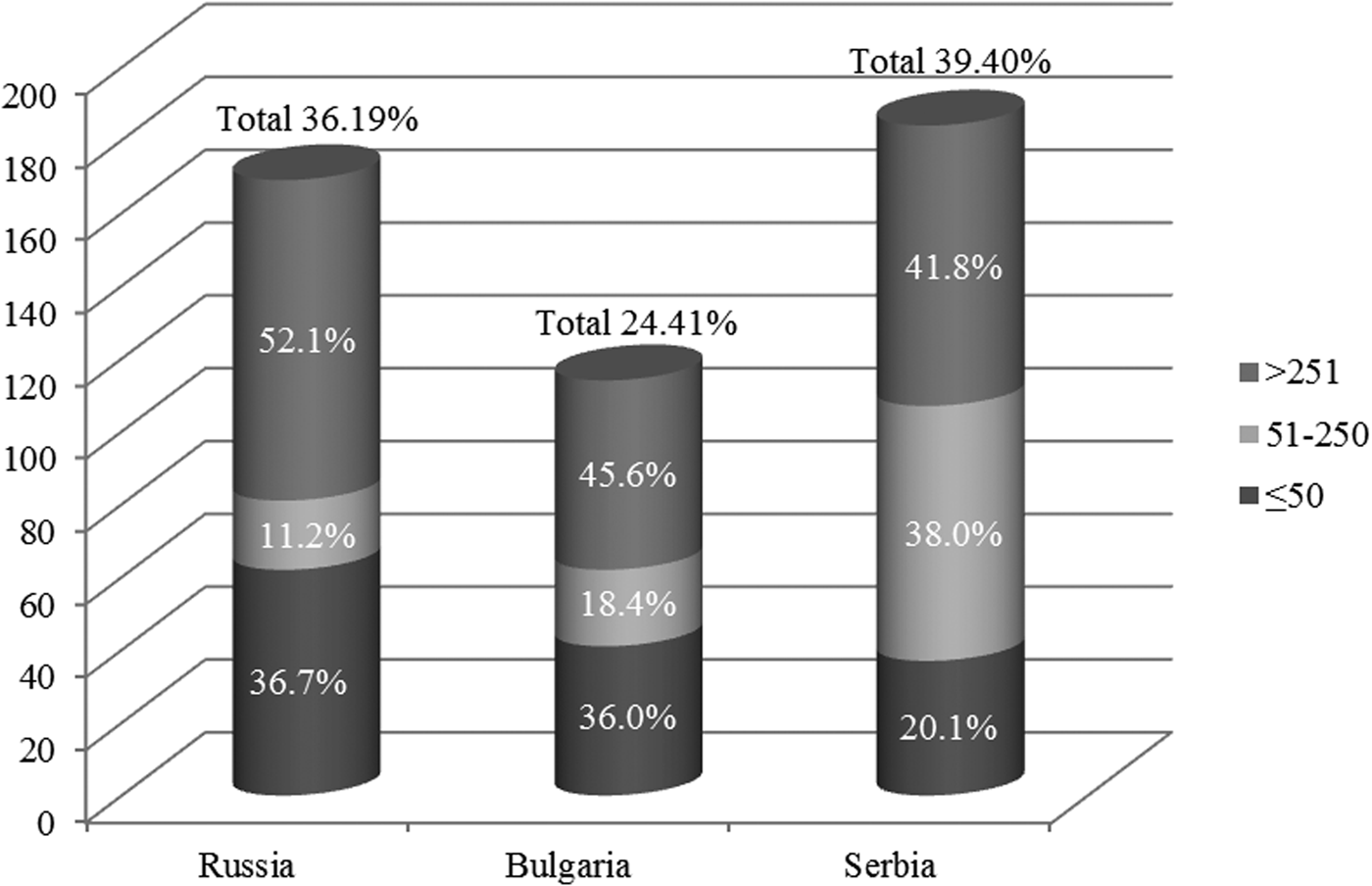

The questionnaire consisted of questions related to the recognition of the CSR concept, demographics and the companies of the respondents. The employees from Russia, Bulgaria and Serbia evaluated the importance of five CSR dimensions (Dahlsrud, Reference Dahlsrud2008) in the companies they work for. The employees expressed their opinion by using a 5-point Likert scale, from value 1 indicating that the statement is not applicable, to value 5 – fully applicable. In total, 467 correctly filled questionnaires were collected: 169 (36.19%) from Russia, 114 (24.41%) from Bulgaria and 184 (39.40%) from Serbia (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Structure of the company by size.

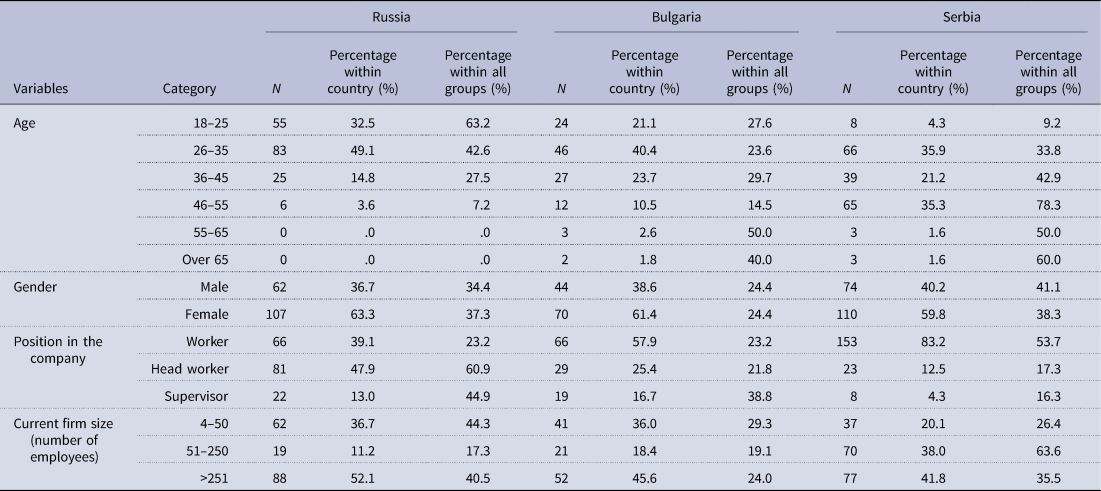

The size of the company is determined based on the number of employees according to the EU recommendation 2003/361. Micro-enterprises with less than 10 employees and small businesses with less than 50 employees were grouped together; medium-sized enterprises are those with up to 250 employees; while those with over 250 employees are defined as large ones. The structure of the company by size in relation to the total number within the state, in percentages, is presented in Figure 2. The descriptive statistics of the sample is presented in Table 1. The descriptive data were presented as percentages within the country and percentages within all groups. Most of the respondents in the age groups 18–25 and 26–35 are from Russia, 63.2% and 42.6% respectively, while those belonging to the age groups 36–45 and 46–55 are from Serbia, 42.9% and 78.3%, respectively. Female respondents slightly prevailed in the samples from all three countries: 63.3% in the Russian sample, 61.4% in the Bulgarian sample, and 59.8% in the Serbian sample. Concerning the position in the company, most of the respondents were manual workers especially in Bulgaria and Serbia, 57.7% and 83.2%, respectively, while, when it comes to Russia head workers belonged to the main group in the sample with 47.9%.

Table 1. Descriptive statistic of the sample

The ranking of opinions of employees was performed using the integrated Entropy-PROMETHEE-GAIA method consisting of several steps (Figure 1).

In order to establish an adequate model, the criteria for CSR assessment were defined through five dimensions: environmental, social, economic, stakeholder and voluntariness.

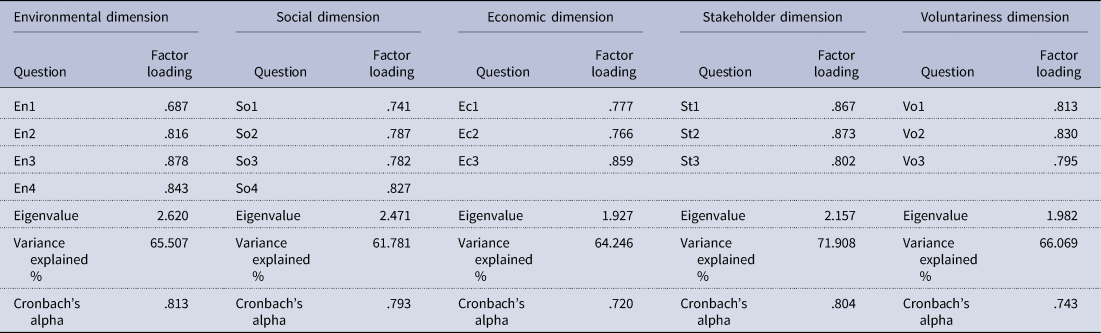

By performing the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and considering all five mentioned dimensions, 17 criteria were defined describing the observed elements in the best manner. The reliability of the groups of questions defining the dimensions was verified using Cronbach's alpha coefficient showing a high reliability since all coefficients exceed the cut-off point of .7 (Field, Reference Field2009). The results of the EFA and reliability check are presented in Table 2 and the items in the scales adopted for this study are enclosed in the Appendix.

Table 2. Results of exploratory factor analysis

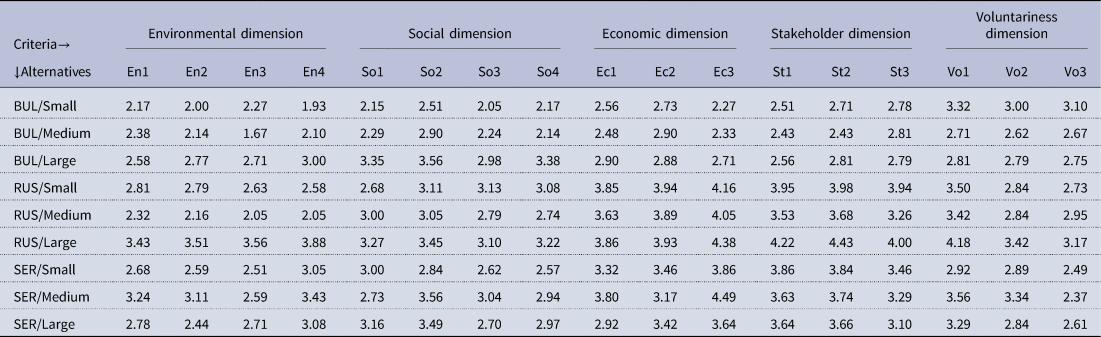

Alternatives are defined as a combination of several variables. Due to the complexity of the research, two demographic questions from the questionnaire were used – the country from which the respondents came and the size of the company in which the respondents work. Nine alternatives representing combinations of states/sizes of the company were created, see Table 3.

Table 3. Initial data for PROMETHEE II ranking

The assessment of the importance of the CSR dimensions, which represent the criteria in the proposed model, was performed using the entropy method (Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Behnoee, Hassanpour and Pamucar2019; Hassanpour & Pamučar, Reference Hassanpour and Pamučar2019). Determining the weight of the criteria can be a difficult task in MCDA. There are two ways to obtain the weight of the criteria. The direct approach implies that the weights are determined by experts, surveys and other common methods, where the weight of the criteria is obtained before collecting the data on alternatives. The indirect approach implies that the weights are determined from the collected data and reflect the information contained in the very data. The direct approach to determining the severity of the criteria is subjective because the weight of the criteria is determined based on subjective estimates by decision-makers, while the indirect approach is more objective because the weights of the criteria are determined by studying the decision matrix and the information contained in the very criteria (Hassanpour & Pamučar, Reference Hassanpour and Pamučar2019; Kao, Reference Kao2010; Milićević & Župac, Reference Milićević and Župac2012). One of the frequently used methods for objectively determining the weights of the criteria is the entropy method in which weights are obtained as values of the distinction between alternatives (Hafezalkotob & Hafezalkotob, Reference Hafezalkotob and Hafezalkotob2016; Radulescu, Fedajev, & Nikolić, Reference Radulescu, Fedajev and Nikolić2017).

The Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluation (PROMETHEE) is a frequently used method for ranking alternatives taking a number of criteria into account (Kilic, Zaim, & Delen, Reference Kilic, Zaim and Delen2015; Živković, Arsić, & Nikolić, Reference Živković, Arsić and Nikolić2017). Since its appearance, the method has gone through a series of upgrades and modifications, a fairly significant one being the addition to the GAIA plane that enables graphic representation of the obtained ranking results (Mareschal & Brans, Reference Mareschal and Brans1988). The PROMETHEE method is based on an outranking approach where alternatives are compared by determining the dominance of one alternative relative to others, taking all defined criteria into account (Nikolić, Jovanović, Mihajlović, & Živković, Reference Nikolić, Jovanović, Mihajlović and Živković2009).

The PROMETHEE II method allows the overall ranking of alternatives obtained by computing positive (Φ+) and negative (Φ−) outranking flows for each alternative. A positive flow determines how much alternative outrank other alternatives, while the negative flow shows how much other alternatives outrank the given alternative. Based on the outranking flows, the total net flow (Φ) was calculated which provided the final order of the alternatives.

After obtaining the ranks, the GAIA plane was formed to understand the numerical results more precisely. The GAIA plane depicts the relations among the ranked alternatives, criteria and the best possible outcome. The sensitivity analysis was performed to determine how different values of criteria weights affected the ranking of alternatives (Doan & De Smet, Reference Doan and De Smet2018).

Results

Based on the structure of the questionnaire and the obtained results, after performing the EFA the decision-making table was defined. The initial data in the decision table were obtained from employees' responses as mean values of assessments for each question (Dobrosavljević & Urošević, Reference Dobrosavljević and Urošević2019), see Table 3.

The weights were obtained for each of the criteria using the entropy method (Table 4). The analysis of the values showed that the attitudes of employees are the most homogeneous in the voluntariness dimension (wv = .07) and the greatest diversity in answers, and hence the greatest influence on ranking, belongs to the environmental dimension (w 2 = .33).

Table 4. The weight coefficients for each criterion

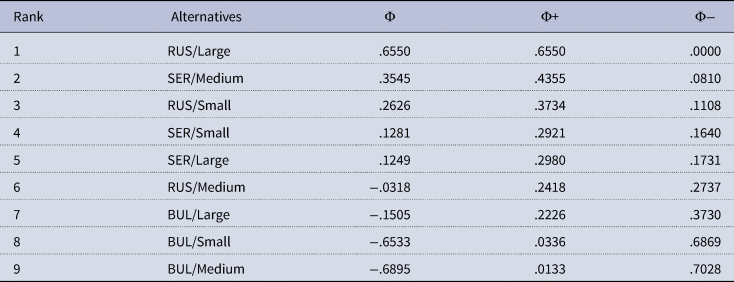

The outranking method PROMETHEE II was used for the ranking of employees' attitudes in relation to the state/company size. The results of the ranking are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Results of PROMETHEE II ranking

Judging by the obtained rankings, the highest importance of the CSR is ascribed by employees in large companies in Russia (Φ = .6550) followed by employees in medium-sized companies in Serbia (Φ = .3545). All three categories of companies from Bulgaria are ranked the worst – large ones go first, followed by medium-sized and finally micro/small enterprises (Φ = −.1505, −.6533 and −.6895, respectively).

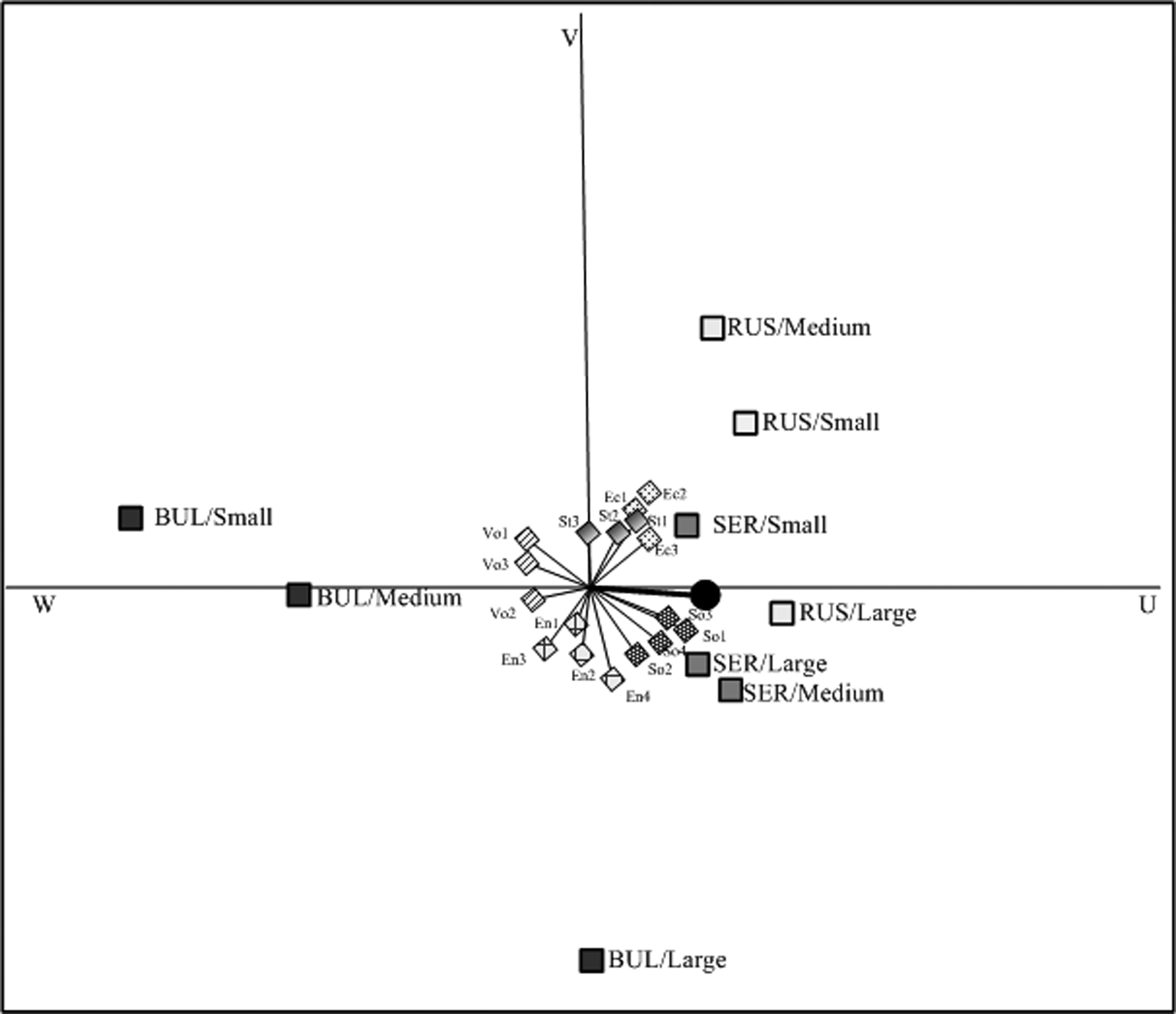

PROMETHEE II ranking results are additionally supported by the graphic representation via GAIA plane (Figure 3).

Figure 3. GAIA plane.

The decision stick (pi stick), which is presented on the GAIA plane with a circle at the top, represents the weights of the criteria and indicates their reliability. Since the weights of the criteria are determined by the objective method of entropy, the GAIA plane shows high compliance of the weight with the preferences obtained based on the respondents' answers.

The economic and stakeholder dimensions are closest to each other which means that the respondents value both equally. Expressed attitudes about CSR have more balanced answers in relation to all other dimensions.

The GAIA plane positions of alternatives show alternatives with similar profiles relative to the criteria. The companies from Bulgaria are positioned far from others, hence Bulgarian employees have different attitudes, regardless of the size of the company in which they work, and the recognition level of CSR activities is very low.

When using the MCDA methods, the results are conditioned by the weights of criteria. Sometimes small changes in the values of the weights of coefficients can cause changes in the ranking of alternatives and therefore the sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine these variations (Karczmarczyk, Jankowski, & Wątróbski, Reference Karczmarczyk, Jankowski and Wątróbski2018; Pamučar, Božanić, & Ranđelović, Reference Pamučar, Božanić and Ranđelović2017; Stanković, Stević, Das, Subotić, & Pamučar, Reference Stanković, Stević, Das, Subotić and Pamučar2020). The tested stability intervals for the first three ranked alternatives and for the first ranked alternative only are shown in Table 6. The wide stability intervals mean that the position of first ranked alternative, large companies from Russia will not change the position if the weights of most criteria are changed. Stability intervals for the first three ranked alternatives vary, and even small changes in the weight value of Ec2, St3 and Vo3 can cause different ordering of the first three alternatives.

Table 6. Stability intervals for individual criteria in the PROMETHEE II ranking

Discussion

The current paper focuses on CSR from the perspective of employees from Russia, Bulgaria and Serbia, working in micro/small, medium-sized or large companies. The integrated Entropy-PROMETHEE-GAIA method was used for comparing and ranking of employees' attitudes.

The assumption that the size of the company significantly influences the level of CSR implementation and collection of benefits from the perspective of employee assessment is correct to a certain extent. During the ranking, the grouping according to the size of the company was not obtained. The analysis of the obtained results pointed out the differences in the attitudes of employees where the highest significance of CSR was given by the employees from large companies operating in Russia. The latter is explained by the fact that large companies operate internationally and easily accept global business trends. Moreover, their business is more exposed to the control of public opinion and institutions. Russia belongs to the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) group of fast growing economies, therefore, the position and economical influence of Russia in the world economy is constantly increasing. Business sector empowerment and ambitions of Russian companies to operate at foreign markets will continue to motivate more profound engagement in all aspects of socially responsible behavior.

The smallest rating of evaluation of the CSR concept importance was received from employees in Bulgaria. This confirms the assumption that the level of understanding and implementation of CSR depends on the level of economic strength of the state. Public discussion on the issue in Bulgaria has gained importance in recent years. The transition from a paternalistic model of social policy, which is characteristic of the socialist type of public relations, to corporative responsibility, represents a slow process, especially if trial and error methods are used (Kunev, Kostadinova, & Stoycheva, Reference Kunev, Kostadinova and Stoycheva2017).

Observing the results of the rankings of employees' attitudes from Serbia considering all three categories of companies, the best ranking was noted in medium-sized enterprises. This can be explained by the economy in Serbia, where some of the largest systems and companies are still owned by the state, while medium-sized enterprises are on the free market and embrace new trends in business faster. Strong institutional frameworks, the existence of legislation and the government insisting on taking over the social role of companies in society should likewise significantly contribute to the quantity and quality of implemented CSR activities.

Conclusion

Social responsibility is a way of connecting companies with the society, the environment and the stakeholders. The main purpose of the company, as a driving force of economic activities aimed at producing welfare, is changing from the welfare of certain groups to responding to the needs of the society. This new level of interest reflects on the monitoring of people's needs and the formation of an environment where companies are no longer business initiators only, but the initiators of the change in the society, as well.

Earlier research already showed significant differences between companies from the United States and Europe in expressing their involvement in the CSR. This can be attributed to differences in the level of government engagement in economic and social activities, wherein US companies have greater corporate discretion and less state interference, but also different assumptions about business and society (Matten & Moon, Reference Matten and Moon2008). Additionally in Russia and Eastern European countries, due to various national business systems with late liberalization of the market, CSR developed later and more slowly (Matten & Moon, Reference Matten and Moon2008). The results of this cross-national research also indicate that variations in the perception of CSR are more dependent on economic and cultural differences, than the size of the company. The Russian companies showed greater level of CSR implementation in comparison with Bulgarian and Serbian ones. This can be explained by the fact that Russia belongs to the 10 great emerging economies, while Bulgaria and Serbia are middle-income countries.

Cross-cultural differences in attitudes and expectations toward CSR are the consequence of traditional values, principles and beliefs that are embedded in ex-socialist societies. The research by Alas and Rees (Reference Alas and Rees2006) showed that employees in post-transitional economies still focus on job security, welfare and pay as principal CSR expectations. This research showed slightly different results, where besides stakeholders' concerns, other dimensions, especially environmental, got great significance in ranking.

Post-socialist states are facing significant challenges in the development of a new business environment and may miss significant opportunities arising from the application of CSR (Sharma, Reference Sharma2019). By defining new institutional frameworks, reducing corruption and positive legislation aimed at establishing responsible business, governments can considerably influence the business environment and CSR adoption (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Oo and Lim2019). However, with CSR commitment, companies are gaining substantial impact. Putting the society and surroundings in the business focus, valuable distinction from the competition as well as a certain form of self-regulation can be achieved (Jamali & Mirshak, Reference Jamali and Mirshak2007), in order to yield better business and social results.

Two noticed limitations of this research can be singled out. First, the results cannot be generalized since the research was conducted in countries with a rather peculiar socio-economic development. Accordingly, further research should be initiated distributing the survey in other South-Eastern European countries. Moreover, the research can expand on developed West European countries undergoing no transition period and where the tradition of CSR is more progressive, so that the results can be compared and new conclusions and recommendations provided. The second limitation relates to the applied methodology, since the choice of different MCDA methods for ranking and weights determination can yield different ranking of alternatives. Future studies should address this limitation by introducing other appropriate methods for testing and comparison.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendix

Items used for assessing the opinion of employees toward CSR dimensions

Environmental dimension: Which of the following measures has your company adopted to reduce environmental impact?

-

En1. Waste recycling

-

En2. Sustainable packaging

-

En3. Develop of environmental friendly product

-

En4. Life Cycle Assessment processes

Social dimension: Which are concrete actions toward the community in which your company operates?

-

So1. Donating to organizations having social or environmental utility

-

So2. Sponsorship of sport and cultural events

-

So3. Cause-Related Marketing campaign

-

So4. Partnership projects of social solidarity

Economic dimension: Which of the following your company implements?

-

Ec1. Employees' compensation is related to their skills and their results

-

Ec2. The guarantee of our products and/or services is broader than the market average

-

Ec3. We provide our customers with accurate and complete information about our products and/or services

Stakeholder dimension: Which of the following activities concerning employees your company implements?

-

St1. Company foster training and professional development of employees

-

St2. Company complies with standards related to labor risks, health, safety and hygiene programs

-

St3. Company is committed to the improvement of the quality of life of our employees

Voluntariness dimension: Which of the following behavior your company demonstrate?

-

Vo1. Our company has a strong sense of CSR

-

Vo2. Our company encourages us to participate in volunteer activities

-

Vo3. Our company organizes ethics training programs for us