1. Introduction

In this paper I provide a syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic analysis of two idiomatic expressions of denial or objection in colloquial Italian, col cavolo (1) and un cavolo (2):Footnote 1

I argue that, despite superficial appearances (a ‘denial’ function of sorts and the occurrence of the same lexical item), these expressions are distinct both structurally and functionally, and that they represent two very different strategies. Col cavolo is a focal, non-verbal predicate of emphatic polarity, the negative counterpart of a class of Italian expressions of emphatic affirmation like certo che, lit. ‘certain that’, which select for full clauses and convey the speaker’s epistemic attitude towards the propositional content of the lower clause; while emphatic affirmations express high commitment to p, col cavolo conveys high commitment to ¬p. On the other hand, un cavolo is what is known in the literature as a ‘metalinguistic negator’, which rejects or objects to an antecedent utterance, comparable to the English ones discussed by Horn (Reference Horn1985, Reference Horn1989) and exemplified below:

What they do have in common, and what I will argue they have in common with other left-peripheral negators (LPNs) and objectors, is the expression of the speaker’s commitment and attitude towards the proposition/utterance. Moreover, the superficial commonality of incorporating the same vulgar element is not unmotivated: cavolo represents a low-scalar endpoint, which is originally employed in both cases to convey minimal speaker commitment to p (hence, high commitment to ¬p) or opposition to including the proposition into the Common Ground.

Relatedly, I propose that un cavolo derives its use as an utterance objector from an illocutionary extension of its use as a vulgar minimiser, along with other members of the same class of Italian indefinite-like expressions which can function as what I call utterance minimisers, by having their scalar semantics recast at discourse level as conveying minimal interest in, or relevance of, the utterance they modify – not necessarily implying falsehood or reversal of truth conditions, then. This is taken to derive from a conventionalised implicature from minimisation to (pragmatic) irrelevance, a development which is compared to a similar cline in Latin.

The second purpose of this article is to provide a typology of the syntax of left-peripheral negators based on the comparison between the Italian cases and similar expressions described in previous literature. In particular, I will hypothesise that the interpretation of the negative import and licensing capabilities of LPNs are a function of their derivational history, and depends on whether they establish a relation to the lower TP-level PolP (by either movement or Agree).

The article is organised as follows. In Section 2 I provide an overview of the concepts of external and metalinguistic negation, falsum, and of existing analyses of the syntactic and semantic-pragmatic properties of idiomatic negators and LPNs. Section 3 offers an analysis of col cavolo as a negative, focal non-verbal predicate reversing the polarity of the lower clause and expressing high speaker commitment against its inclusion in the Common Ground. Section 4 is an analysis of un cavolo as an utterance minimiser, a pragmatic, utterance-level extension of the low-scalar import of its use as a vulgar minimiser. Section 5 summarises the similarities and differences between the two negators and lays out a structural typology of LPNs and utterance minimisers. Section 6 concludes.

2. Clarifying the Terminology: External, Metalinguistic, and Emphatic Negation

Before discussing col cavolo and un cavolo, it is necessary to present a brief background on the notion of emphatic negation and to define in which sense similar illocutionary operators are considered negative in the previous literature. This will allow us to correctly identify the features of the two constructions under exam and their relevance for cross-linguistic analysis.

2.1. Metalinguistic negation and falsum

The concept of external negation opens Horn’s (Reference Horn1985) work on the pragmatic ambiguity of metalinguistic negation. Consider (5), originally due to Bertrand Russell, and (6):

In (5), negation does not negate the predicate bald, but the presupposition that a king of France exists; in (6), negation cancels the implicature that tall means ‘moderately tall’: a ‘descriptive’ understanding of negation would be contradictory, since one cannot be colossal without also being tall. Negation thus appears to be ambiguous, capable of denying either asserted or non-asserted (implicated, presupposed, etc.) content. Horn argues that the ambiguity can be resolved in the following way: ‘negation […] is not semantically ambiguous. Rather, we are dealing with a pragmatic ambiguity, a built-in duality of use’ (Horn Reference Horn1985: 132; emphasis in the original). Other uses which Horn notes are difficult to lead back to a logic or semantic ambiguity are those which object only to formal aspects of an utterance (his She’s not Lizzie, if you please—she’s Her Imperial Majesty). For these cases, Horn recovers Ducrot’s (Reference Ducrot1972) concept of metalinguistic negation, defined as ‘a means for objecting to a previous utterance on any grounds whatsoever, including […] the way it was pronounced’ (Horn Reference Horn1985: 134). Thus, by virtue of its association with the pragmatic rather than semantic level, metalinguistic negation conveys an objection to an utterance, rather than the truth of a proposition. This corresponds to ‘a use distinction: [negation] can be a descriptive truth-functional operator, taking a proposition p into a proposition not-p, or a metalinguistic operator which can be glossed “I object to u”, where u is crucially a linguistic utterance rather than an abstract proposition’ (Horn Reference Horn1985: 136).

The idea that metalinguistic negation is a pragmatic device rather than a semantic operator accounts for further differences with descriptive negation. As Karttunen and Peters (Reference Karttunen and Peters1979: 46–47) originally noted, metalinguistic uses of negation fail to license polarity items:

Horn comments that since negation in (7) targets not the assertion but the implicature carried by manage, it is truth-conditionally and semantically inert, and as such, it is not a suitable licensor for any.

The idea that negation may be recast as a discourse/illocutionary operator was reprised by Repp (Reference Repp2009, Reference Repp, Gutzmann and Gärtner2013), who proposes a discourse operator for ‘illocutionary negation’ which she calls falsum (8).Footnote 2 This operator has similar semantics to Romero and Han’s (Reference Romero and Han2004: 627) verum (cf. fn. 2), the difference being that whereas under verum the proposition is a member of the Common Ground, falsum conveys that it is not:

In prose, given all the worlds w′ which conform to x’s epistemic state (knowledge) in w, and all the worlds w″ which conform to x’s conversational goals in w′, it is for sure that the proposition p is not in the Common Ground in w″. Repp proposes that the two operators express what she calls ‘degrees of strength of sincerity’. Sincerity conditions, a reflex of the Maxim of Quality requiring the speaker to believe that the proposition expressed is true, are a gradable property; while verum conveys that the speaker’s degree of sincerity is high, falsum conveys that the degree is zero. Thus, while Repp’s formula does not include a negative operator, the contribution of falsum is essentially equivalent to negation, but it is applied at the level of the illocution rather than at the propositional level (what Repp calls ‘illocutionary negation’).Footnote 3

Thus, the speaker who uses falsum objects to the addition of p to the Common Ground on the basis of the fact that it cannot be felicitously uttered (cf. Horn’s understanding of metalinguistic negation as operating at the level of the utterance). But crucially, while it may have the same logic effect of negation at the truth-conditional level, it will not correspond to negation semantically (for instance in terms of licensing capabilities) as it applies at a different level than the propositional level at which descriptive negation applies, which is why falsum/metalinguistic negation cannot license NPIs either (English expresses falsum by stressing the negative marker, cf. fn. 2):

2.2. The syntax of ‘metalinguistic negators’

In line with Horn’s observation that languages do not lexicalise a separate external negator, Repp’s falsum is lexically identical to the standard negator. Yet, languages often possess idiomatic expressions which convey metalinguistic negation or falsum. Martins (Reference Martins2014: 645–649) discusses peripheral metalinguistic negators in European Portuguese, like uma ova, lit. ‘a fish’s roe’ (note that viver is an intransitive verb, which excludes that uma ova is a direct object):

These expressions can appear on their own in fragments:

They can co-occur with standard negation yielding a double negation reading:

They have wide scope (e.g., they scope over both conjuncts in a sequence of coordinated events):

Martins (Reference Martins2014: 651) takes these and other features as evidence that these elements are externally merged in the left periphery. When uma ova is sentence-initial no movement operation takes place, while when it is sentence-final IP-topicalisation follows External Merge of uma ova in SpecCP (I adapt and simplify Martins’ 2014: 653 analysis for brevity):

Martins relates the connection between metalinguistic negation and the CP to Farkas and Bruce’s (Reference Farkas and Bruce2010) distinction between initiating and responding assertions. The former have ‘absolute’ polarity features, while the latter have ‘relative’ ones, which means that, while with initiating assertions the polarity is independent of the discourse context, with responding ones (including Verum/falsum) the polar features interact with the polarity of the utterance they react to. Farkas and Bruce (Reference Farkas and Bruce2010: 106–107) propose two kinds of polarity features for responding moves, [same] for confirmation and [reverse] for opposition. Martins (Reference Martins2014: 664) proposes a further one, inspired by Horn’s (Reference Horn1985) classic definition of metalinguistic negation: the feature [objection], which is carried by metalinguistic negators. These examples illustrate that metalinguistic negators can coexist with an independent expression of (positive or negative) polarity in the lower proposition, causing a double negation effect. Martins (Reference Martins2014: 665) takes ‘the exclusive features of responding assertions, that is, relative polarity features, to be grammatically encoded in the CP domain, whereas absolute polarity features are encoded in ΣP, the topmost functional projection in the IP domain’ (cf. Laka Mugarza Reference Laka Mugarza1990). Martins thus advocates for a double syntactic exponence of polarity, with different functions and interpretations. These observations can be tied to the assumption (Speas & Tenny Reference Speas, Tenny and Di Sciullo2003, Ramchand & Svenonius Reference Ramchand and Svenonius2014 a.o.) that the CP-layer is the locus of the interface between syntax and discourse. It is thus fitting that a discourse-managing operator like metalinguistic negation should be preferentially expressed in this clausal area.

Martins (Reference Martins, Espinal and Déprez2020) points out another difference between standard negation and metalinguistic negative markers, coherent with their left-peripheral nature: the latter take wide scope over the lower material, as also discussed by Lasnik (Reference Lasnik1972: 50–51). Consider her examples:

While the standard negator allows for scope ambiguity with respect to the reason adjunct in (17), the negative idiomatic phrase in (18) only allows for the reading in which negation scopes over the reason adjunct.

2.3. Left-peripheral negation is not (necessarily) metalinguistic

Despite Martins’ observations, it is important to stress that not all expressions of left-peripheral negation are metalinguistic in nature. Several languages possess idiomatic negators which are left-peripheral but do not present the hallmarks of metalinguistic negation. Moreover, some languages have been argued in the literature to express not only idiomatic or emphatic negation, but even standard negation in dedicated left-peripheral projections. Well-known cases are Gbe languages, for whose negation Aboh (Reference Aboh, Aboh and Essegbey2010) proposes a left peripheral position just below FocP. Another is Modern Irish, which has negative complementisers which McCloskey (Reference McCloskey, Aboh, Haeberli, Puskás and Schönenberger2017) derives from Agree with a TP-level [iNeg]-bearing PolP.

Moreover, there are further cases of expressive or emphatic left-peripheral negation which, though idiomatic, do not have any presuppositional or metalinguistic import, can license (some) polarity-sensitive items, and are truth-conditionally equivalent to sentential negation. I will review three which are relevant to the present discussion: British/Irish English fuck-inversion (Sailor Reference Sailor2017, Reference Sailor, Wolfe and Woods2020), Russian xuj-negation (Erschler Reference Erschler2023), and Irish Demonic Negation (McCloskey Reference McCloskey2009, Reference McCloskey2018, D’Antuono Reference D’Antuono2024a).

2.3.1. Fuck-inversion

Fuck-inversion is exemplified below (Sailor Reference Sailor2017: 88):

This construction is characterised by subject-verb inversion, similar to negative inversion proper, followed by a taboo term. Like negative inversion proper, fuck-inversion is downward-entailing (Sailor Reference Sailor2017: 91) and licenses polarity items, even strong ones like until (Sailor Reference Sailor2017: 92):Footnote 4

Sailor also notes that fuck-inversion differs from metalinguistic negators. To begin with, it can be used in the absence of an overt linguistic antecedent (Sailor Reference Sailor2017: 95):

It can also be used to answer information-seeking questions, similarly to regular negative inversion and again differently from metalinguistic negators (Sailor Reference Sailor2017: 96):

Sailor proposes that the taboo term does not instantiate the negative component of the construction; rather, it (partially) realises the emphatic component: fuck is a polarity-sensitive focus particle, to which Sailor assigns the Spec position of the vP-peripheral FocP (Belletti Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004). Negative inversion is triggered by the presence of a null negative operator à la Zeijlstra (Reference Zeijlstra2004), which moves to the left-peripheral SpecFocP from the TP-level PolP, causing the auxiliary to raise to Foc° (hence the incompatibility with a lower expression of negation, cf. fn. 4), similarly to Haegeman’s (Reference Haegeman, Horn and Kato2000) account of ‘overt’ negative inversion in terms of the Negative Criterion (e.g., Never have I seen such a thing):

2.3.2. Xuj negation in Russian

Erschler (Reference Erschler2023: 2) discusses the Russian vulgar negator xuj:

Xuj gives rise to double negation when it co-occurs with the standard negative marker (Erschler Reference Erschler2023: 3):

Xuj licenses polarity items (27), but crucially not ni-words (28), which Erschler (Reference Erschler2023: 10–12) argues to be Negative Concord Items (NCIs)Footnote 5 which are licensed locally by a null Neg° operator in the lower PolP rather than with xuj (cf. (29)); thus, xuj is incapable of licensing negative concord items, but it can license (weak) polarity-sensitive items (Erschler Reference Erschler2023: 6–7):

Erschler proposes the structure (29), where the lower PolP hosts a negative operator responsible for negating the clause (and for licensing NCIs like ni-words); xuj, which is associated with another negative operator, is ‘segregated’ in a higher left-peripheral PolP:

Thus, xuj and the standard negative operator occupy separate, independent projections, which explains the obligatory double-negation reading when they co-occur.

2.3.3. Irish ‘Demonic Negation’

D’Antuono (Reference D’Antuono2024a) offers an account of Irish ‘Demonic Negation’ (named after McCloskey Reference McCloskey2009, Reference McCloskey2018):

D’Antuono proposes that dheamhan, originally meaning ‘(to a) demon’, grammaticalised as an emphatic negator and is externally merged in a left-peripheral PolP, as indicated by the ‘indirect’ complementiser aN – distinguished by the nasalisation of the initial consonant of the following verb – which following McCloskey (Reference McCloskey, Epstein and Seely2002) diagnoses base-generation in the left-periphery. Additionally, dheamhan can be followed by a constituent of any grammatical category – the object DP duine (ar bith) in (30b) – in this instance with a scalar effect comparable to Germanic Negative Inversion (i.e., Not a single person did I see). In this case, the ‘direct’ complementiser aL appears, which causes lenition of the initial consonant of the following verb and is a diagnostic of movement to the left periphery (McCloskey Reference McCloskey, Epstein and Seely2002), indicating that the constituent to the right of Demonic Negation has been raised to the left-periphery. D’Antuono (Reference D’Antuono2024a) offers the following analysis for the two versions of Demonic Negation, which he calls respectively ‘Bare Demonic Negation’ and ‘Demonic Negation plus XP’:

Like fuck-inversion and xuj, dheamhan can also license polarity items, like ar bith, both in the left periphery and in the lower clause. Moreover, it can co-occur with a lower sentential negation yielding double negation, again like xuj:

Importantly, Demonic Negation is not limited to the expression of metalinguistic or external negation: it is not a presuppositional negator or a marker of denial. D’Antuono concludes that Demonic Negation is a full-fledged negative operator, with the complete palette of readings that are available to standard negation and with polarity-licensing capabilities, and not a metalinguistic negator.

It is clear from this brief overview that the idiomatic or emphatic nature of expressive negators does not automatically correlate with an ‘external’, ‘special’, or ‘metalinguistic’ semantic-pragmatic specialisation, let alone with left-peripheral position. What the association with the left periphery does appear to correlate with is an emphatic, evidential, or epistemic import, and the expression of a strong attitude of the speaker towards the proposition. In what follows, I will discuss how the two Italian expressions fare with respect to the typology just expounded and to the analyses existing in the previous literature.

3. The Syntax of Col Cavolo

The main topic of this section is the expression col cavolo (henceforth CC, lit. ‘with the cabbage’). The relevant construction is repeated below; (34b), a counterpart of Sailor’s (Reference Sailor2017: 95) example, illustrates that CC is not a ‘presuppositional’ negator, since it does not have to constitute a denial of a previous statementFootnote 6:

Thus, CC does not have to constitute a reversing action in Farkas and Bruce’s (Reference Farkas and Bruce2010) terms: it is not specialised as a responsive move to a previous utterance (though it is very commonly used in denials due to its emphatic import). Prosodically, CC bears focal prominence. It is followed by a clause headed by the complementiser che. Footnote 7 Col cavolo can also be used in negative fragments:

Semantically, CC conveys a strong commitment on the part of the speaker to the truth of ¬p (or, conversely, to the falsehood of p), p being the proposition of the lower clause.

It is tempting to associate CC with FocP, not least because of the pitch prominence that is associated with it. There are several facts which seem to support this analysis. Firstly, it is incompatible with another focalised constituent (under any interpretation):

Notably, for me it is also incompatible with Foci in the lower clause (which aligns with the fact that CC takes obligatory wide scope, cf. (58)):

Instead, it is compatible with topics, or with CLLD constituents in general, and can occur below them (38a) and also below Scene-setting adverbials (38b):

Finally, the very fact that it can be used in fragment answers also seems to conform to a focal analysis for CC, given Merchant’s (Reference Merchant2004) suggestion that fragments are moved to SpecFocP.

To clarify the syntax of CC, it will be useful to examine a class of Italian non-verbal predicates which bear a considerable similarity to the expressions under exam.

3.1. Italian non-verbal predicates

The non-verbal predicates I mean to examine are those mentioned by Poletto and Zanuttini (Reference Poletto and Zanuttini2013: 133) in their study of sì che/no che sentences in Italian. These are adjectives like certo, chiaro, ovvio (‘certain, clear, obvious’), followed by a clausal complement.

These elements also share the peculiar focal features of CC ((40)–(42) are adaptations of the authors’ (10)–(12), (16), and (47)).Footnote 8 They are incompatible with the presence of a focussed constituent:

They are compatible with CLLD constituents (41) and provide fragment answers (42):

Poletto and Zanuttini’s (Reference Poletto and Zanuttini2013: 124) main empirical object are sì che/no che sentences:

These negators present the same familiar features of CC and of other non-verbal predicates: they are emphatic, they are incompatible with the copula and with focussed constituents, and they are compatible with CLLD constituents.

Poletto and Zanuttini (Reference Poletto and Zanuttini2013) consider the status of the complementisers in this type of structure to be unclear. In Rizzi’s (Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997) cartography, che is the complementiser sitting in the head of the highest projection of the left periphery, ForceP. Nonetheless, they claim that this cannot be correct for the case at hand. Consider (44) (Poletto & Zanuttini Reference Poletto and Zanuttini2013: 130):

If answer particles are assumed to occupy SpecFocP in Italian, the fact that this position is found below che (and below CLLD constituents) would derive the wrong surface structure. Moreover, CLLD constituents, which are taken to occur below ForceP (Benincà & Poletto Reference Benincà, Poletto and Rizzi2004), may occur below the complementiser in sì che/no che sentences (Poletto & Zanuttini Reference Poletto and Zanuttini2013: 131). I believe this to be the case for CC sentences as well:

Thus, both CC and no che appear to sit above ForceP. A crucial difference between no che sentences and CC is that the former require the presence of negation in the lower clause:

For the combined reasons given above, Poletto and Zanuttini propose that sì che/no che sentences are biclausal, i.e., the particles lie above ForceP – the topmost projection – because like CC they scope over a full clause. They propose the following structure for sì che/no che (Poletto & Zanuttini Reference Poletto and Zanuttini2013: 136):

The authors posit a PolP (Laka Mugarza’s Reference Laka Mugarza1990 ΣP) whose Spec is occupied by an empty category e, which is valued as negative by a higher null negative operator in ForceP, in turn connecting no to the clause introduced by che. When this happens,

the head of PolP is realized as non; otherwise, the head of PolP is null. This is the reason why the co-occurrence of no and non gives rise to single instance of negation, and not to double negation: no binds an operator which has the same value as the head of PolP, non, resulting in a single chain. (Poletto & Zanuttini Reference Poletto and Zanuttini2013: 136)

This also explains why focussed constituents are not allowed with sì che/no che sentences: the operator chain of Focus fronting would create a minimality violation with the polarity chain, the authors note.

As for the position of the answer particle in sì che/no che sentences, Poletto and Zanuttini (Reference Poletto and Zanuttini2013: 135, adapted) propose that it occupies the Spec of the PolP of the higher clause, possibly moving to its SpecFocP.

The polar chain with the lower negation represents a crucial difference between no che sentences and CC which, along with the aforementioned similarities, will further inform the structural analysis of CC.

3.2. Back to col cavolo

A first, obvious difference between no che sentences and CC is that the latter is compatible with both a positive and a negative lower clause (in contrast to fuck-inversion). If CC scopes over a negative clause, double negation occurs:

It thus appears that the polarity of the clause introduced by che is independent from the negative contribution of CC. No simultaneous binding of the polar variable in PolP seems to be at work between the lower non and CC in (49b), and the result is that the two negations cancel each other out, as with Demonic Negation and xuj. As noted by Poletto and Zanuttini, non-verbal predicates like certo may also take a negative lower clause. It seems, then, that with CC there is no ‘continuous’ chain with the lower PolP.

In Poletto and Zanuttini’s analysis, the purpose of the negative operator in ForceP is to relate the answer particle in the higher clause to the polarity of the lower one. But in the case of CC, no such relation appears to exist: as illustrated, CC cannot agree with the lower negation, but only yields double negation in composition with it. On the other hand, if no agreement chain is formed between the variable in SpecPolP and the operator in SpecForceP, what prevents a focussed constituent from moving to the Spec of the lower FocP? This movement would not induce any minimality effect. Everything falls out if, as argued, CC itself sits in a focus projection: CC is incompatible with focussed constituents because it occupies Focus.Footnote 9

Can we say that CC is extracted from the lower clause, like the negative operator in fuck-inversion? As mentioned in fn. 7, CC can also appear rightmost, at least for some speakers. It could then be suggested that CC is extracted from a lower position, perhaps an adjunct position. This analysis does not appear to be satisfactory, though. First of all, for some speakers the sentence-final version is unavailable (fn. 7). This unavailability would be bewildering if CC were extracted from that position. Moreover, when a constituent is Focus-fronted to the left periphery in Italian no complementiser appears before it, differently from clefts (Belletti Reference Belletti2008). CC does not allow for the presence of the copula, which suggests that it is a different construction (and conversely requires the presence of the complementiser, which is impossible for Focus-fronted constituents in Italian, cf. (50b)):

Moreover, CC sentences do not appear to have the corrective or mirative interpretation that is available in Italian to constituents that are focus-fronted (Bianchi & Bocci Reference Bianchi, Bocci and Piñón2012, Bianchi et al. Reference Bianchi, Bocci and Cruschina2016) or clefted. For instance, in (50b) the focalisation of Gianni creates a set of alternatives (Rooth Reference Rooth1992), to the effect that Gianni is understood as the entity which makes the proposition true out of a given set. Additionally, if CC is truly extracted from a lower position, it loses its idiomatic meaning. Consider the examples in (51), with an adjunct concerning a literal cabbage in (51a), and CC in (51b):

(51a), albeit slightly burdened by successive-cyclic movement, is acceptable in Italian with an extraction from the lower clause. (51b) relates to the previous observation that the emphasis of CC is associated with an attitude towards p, which in turn requires an association with an epistemic centre or point of view (Potts Reference Potts2007). In (51b), the negative force of CC can only apply to the speaker’s attitude. It cannot mean that Gianni had no intention whatsoever of coming, as would be expected if col cavolo were possibly/optionally generated as a negative adjunct in the lower clause (thus associated with Gianni’s epistemic state) and later moved to the high SpecFocP. In this connection, consider (52):

In (52) CC can emphasise Gianni’s intention of not coming,Footnote 10 with the propositional attitude attributed to the subject. This is the reading which is not available for (51b), where Gianni’s coming is embedded under another clause. Conversely, this interpretation is only possible if CC is embedded, as in (53):

This set of properties means that the anchoring (in Speas & Tenny’s Reference Speas, Tenny and Di Sciullo2003 terms) of CC does not have to correspond to the Speaker; it can also be associated with the subject of the clause immediately dominated by CC, but crucially it must be local to it and cannot reconstruct into an even lower clause. Hence it cannot have Ā-moved to a higher SpecFocP from there. I take this to imply that CC is base-generated in its Spellout position, as proposed by Martins (Reference Martins2014, Reference Martins, Espinal and Déprez2020), Erschler (Reference Erschler2023), and D’Antuono (Reference D’Antuono2024a) for their respective expressions. This, in turn, makes it more plausible that, for those speakers who accept it, sentence-final CC also occupies this position in a biclausal structure, with the lower clause moving to a SpecTopP (or GroundP) above the FocP hosting the LPN, as illustrated belowFootnote 11:

(54) makes sense of the focal features of CC, as well as of the clause-externality it shares with other non-verbal predicates and no che sentences. Yet, I would like to discuss an interesting alternative analysis, due to an anonymous reviewer. Krifka (Reference Krifka, Hartmann and Wöllstein2023) proposes a ‘layer of assertions’ model whereby a region exists above ForceP, composed of discourse-managing projections: a Judgement phrase, which hosts evidential modifiers identifying the source of the epistemic attitude towards the proposition (e.g., apparently), a Commitment phrase which expresses the (speaker’s) commitment to the lower proposition (German wirklich, ‘really’), and a Speech Act phrase which motivates or explains the speech act, or relates it to other ones (German offen gesagt, ‘frankly speaking’):

It is natural to associate CC with the ComP, since Krifka himself proposes that other expressions of polar commitment/Verum/falsum (like Egyptian Arabic wallahi, Mughazy Reference Mughazy2003) occupy this position. CC would thus sit in ComP. The CC-final version would be derived by movement of the lower clause to SpecActP, perhaps motivated by the latter’s ‘relational’ function with respect to the Common Ground.

The proposition-externality of ComP allows an alternative explanation of the ‘biclausality’ effect of CC and of other non-verbal predicates. The FocP- and ComP-based analysis are both viable in my view. The latter could also account for the fact that one of the few types of elements which may occur after CC are epistemic modifiers, assumed to occur in JPFootnote 12:

Yet, I believe that taking CC to sit in a FocP better accounts for the focal features of CC and for its complementarity with other Foci. The fact that CC is low enough to occur below Topics, CLLD constituents, and Scene-setting adverbials (38) also follows more easily from the FocP analysis. In what follows I will adopt (54), while maintaining that (56) is a possible alternative structure.Footnote 13

The clause-external nature of CC is further supported by a parallelism with Martins’ (Reference Martins, Espinal and Déprez2020) example in (18):

That CC cannot scope over the reason adjunct alone further confirms its external position with respect to the lower clause it dominates, as well as the base-generation analysis.

I would like to propose that this is a crucial divide among LPNs: those which are internally merged into the left periphery (like negation in fuck-inversion) or participate in an Agree chain with the TP-level PolP (like no che) have full licensing capabilities, and consequently either require (in the case of Agree, cf. no che *(non)) or ban (in the case of movement, cf. fuck-inversion) the presence of a negation in the lower clause; those which are base-generated in the left periphery (like CC, xuj, and Demonic Negation) only have limited licensing capabilities and yield double negation with a negative lower PolP, to which they are not related by either Agree or movement. In the next subsection I will further argue for this analysis.

3.3. Col cavolo and polarity licensing

A classic test for the negativity of a marker is its ability to license polarity-sensitive items. These tests align CC with LPNs like xuj and Demonic Negation. Most of the Italian polarity items are NCIs (cf. fn. 5), and CC does not seem to be able to license them:

This is in line with Erschler’s observation that xuj cannot license the NCI ni-words in Russian. If CC sentences are indeed biclausal, then the ungrammaticality of (59) may be due to the difficulty in licensing NCIs across domains (a consequence of the clause-bound nature of the Agree operation) rather than to the lack of negative import in CC.

There are some Italian idioms which have the distribution of weak NPIs. One is the phrase alzare un dito, ‘lift a finger’. That alzare un dito is a weak NPI is demonstrated by the fact that, apart from negation, it can be licensed by monotone decreasing quantifiers (60a) and in long-distance configurations (60b):

Now, alzare un dito is acceptable in the scope of CC, and so are other weak elements like mai, ‘(n)ever’, just as (weak) PIs are licensed by xuj and Demonic Negation:

This aligns with the fact that, like fuck-inversion, CC is nonveridical (i.e., does not entail the truth of the following proposition, Giannakidou Reference Giannakidou1998), or in any case monotone decreasing (62):

Regardless of whether it is nonveridicality, downward entailment (Ladusaw Reference Ladusaw1979), or some other property that licenses weak NPIs, then, it is unsurprising that CC should license them.

Does this prove that CC is not formally negative? Like its cross-linguistic counterparts, CC can indeed be negative (i.e., have the same semantic import as a sentential negator like non), with the impossibility of licensing NCIs being due to locality restrictions on Agree. Consider (63), featuring the strong NPI affatto, ‘at all’ (suggested by Matteo Greco, p.c.):

Like NCIs, strong NPIs must be licensed locally by negation (and mere downward monotonicity is insufficient, cf. (63b)), so biclausality suffices to exclude (63a), without this militating for the non-negativity of CC. The polarity licensing facts go in the direction of my own structural analysis; yet, I think that the relevance of the licensing pattern of CC goes beyond this observation. Again, base-generated LPNs like CC and xuj have limited licensing capabilities, while those which are related to the lower PolP by Agree or movement, like no che, fuck-inversion, as well as Irish standard negation, pattern together both in terms of the possibility and interpretation of a lower negation, and in terms of polarity and negative licensing.Footnote 14

The generalisation is that when an LPN is base-generated, the semantic effects of its negative import cannot ‘reach’ into the lower clause: a negator bound to occur in the left periphery by its association with discourse or speaker orientation is non-local to the lower clause unless it is related to its PolP by Agree or movement. Thus, base-generated LPNs can only license those weak elements in their scope for which their properties of nonveridicality and downward monotonicity suffice. LPNs related to the semantically active negation/polarity of the TP-layer, on the other hand, share in its full semantic and licensing capabilities.

4. Un Cavolo: Metalinguistic ‘Negators’ as Utterance Minimisers

Despite superficial similarities, un cavolo (‘a cabbage’, UC) is radically different from CC: it is functionally and pragmatically distinct, syntactically different, and I will conclude that this expression is not even a negator, but rather a vulgar minimiser with its import applied at the level of the utterance. Yet, I believe that its analysis will considerably enrich the understanding of what ‘metalinguistic negators’ are, and its lexical kinship with CC will be at least in part motivated. UC is exemplified again in (64):

In (64), the speaker refuses to allow the interlocutor’s proposition into the Common Ground. (Part of) the interlocutor’s utterance is repeated, and UC either follows or precedes it. UC can also appear in isolation, in which case it works like an emphatic negative answer particle (64B′). Differently from CC, UC can only be used in response to another utterance (65a), or in any case to reject given information (65b), no new lexical material can be added to it (65c), and it cannot answer information-seeking questions, which do not presuppose their answer (65d):

These features (especially (65a–c)), which Sailor (Reference Sailor2014) fittingly terms neophobia, are reminiscent of the conversational moves he calls ‘retorts’ (of which sì che/no che sentences appear to be a subcase):

Retorts are ‘polarity-reversing assertions’ – which is also reminiscent of what CC does. The difference with retorts proper is that CC is not intrinsically responsive (34b): retorts reverse the polarity of an antecedent, and Sailor claims that they are related to the lower ΣP by movement or by an operator (the similarity with Poletto and Zanuttini’s analysis of no che and with fuck-inversion is apparent):

On the other hand, CC is both independent from an antecedent and from the polarity of the lower clause.

Conversely, while being responsive, UC is more ‘metalinguistic’ than retorts: it does not so much refer to the truth or falsehood of the proposition, rather it objects to an utterance being accepted into the Common Ground. For instance, in the context of (70) John may well be a doctor: (70B) objects to the utterance on the grounds of the irrelevance of this fact in the face of his incompetence:

The modifiability of the ‘inherited’ material from the previous utterance is also limited: the utterance is almost completely opaque (the only elements which can be modified with respect to the antecedent are deictic ones, like 1st and 2nd person pronouns and locative adverbs; for the rest, the preceding utterance is repeated verbatim). When only part of the utterance is repeated, it is generally the part with which the speaker disagrees:

It has no polarity-licensing capability whatsoever:

These features of UC confirm that it acts as a metalinguistic objector, rather than as a semantic negator dealing in truth conditions.

This is also confirmed by the fact that the rejected utterance may express no truth conditions at all. Consider the following real-life, spontaneous example (from an episode of the Italian TV show Propaganda Live, La7). An old lady at a demonstration cannot advance because of the crowd and, more insurmountably, because of a barrier. A man tells her Prego (‘please/I beg you/be my guest’), a fixed expression, to invite her to pass. The old lady answers:

Connectedly, consider (74):

(74B) cannot be interpreted as a negative imperative (‘Do not go’), but only as a rejection of the imperative illocution as a whole (‘I am not going’, ‘Do not tell me to go’, or something along those lines).

I would like to make a tentative hypothesis at this point. A remarkable aspect of UC is its DP structure, which it shares with other metalinguistic objectors which have a similar distribution and function: un fico secco ‘a dried fig’, un cappero ‘a caper’, un accidente ‘a disgrace/curse’, un corno ‘a horn’, and also with Portuguese and Spanish ones (uma ova, una mierda, cf. Martins Reference Martins, Espinal and Déprez2020). These items have in common either the fact of being vulgar or that of having a referent that is of little worth or desirability. In fact, they can be taken to be scalar endpoints, with the scale based on intrinsic value or relevance of the referent of the head noun (Zeijlstra Reference Zeijlstra2018). The presence of a determiner, and in particular of the indefinite article un, then, is not due to chance; it denotes an atomic, scalar endpoint.Footnote 15 The purpose of these expressions is to equate the (conversational/informational) value of the preceding utterance to the lower end of an epistemic scale of relevance, downplaying its communicative or informational value.Footnote 16 These utterances are a kind of equative structure: they minimise the contribution of the targeted utterance to a scalar point that is so low that the utterance itself is inferred to be informationally worthless. This scalar or minimising flavour of ‘metalinguistic negators’ is fundamental for an understanding of their uses and semantics; they are, in a sense, utterance minimisers.

As for the syntax of UC, I see two alternatives. One is that, given its (pseudo-)predicative nature, this equative construction is similar to a small clause, where UC is a predicate expressing minimal conversational/informational value of the SubjP, which is occupied by the opaque linguistic material under discussionFootnote 17:

An anonymous reviewer proposes an alternative analysis in terms of Wiltschko’s (Reference Wiltschko2021) interactional language model. Similarly to Krifka (Reference Krifka, Hartmann and Wöllstein2023), Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko2021) posits an ‘interactional spine’ above the CP layer, devoted to speaker-addressee interaction (cf. Speas & Tenny Reference Speas, Tenny and Di Sciullo2003) and Common Ground management:

The reviewer proposes that UC could be associated with GroundSpkrP, where it values a [coincidence] feature as negative, thus objecting to the addition of an antecedent p to the Common Ground without asserting its polar opposite, which is what UC does. The copy of the lower material, which conversationally ‘belongs’ to the addressee, may be assumed to raise to GroundAdrP:

The reviewer’s suggestion is valuable; perhaps the small clause analysis fares better with respect to the pseudo-predicative nature of the UC construction, as well as with the syntactic opacity of the lower material, which behaves more like inert, quoted metalinguistic material. As with the alternative analysis of CC in (56), I maintain this as a possible alternative for UC.Footnote 18

The small clause approach is also reminiscent of other cases of ‘Root Small Clauses’ (Progovac Reference Progovac2015: 35), among which ‘Mad magazine sentences’ (78) (Akmajian Reference Akmajian1984)Footnote 19:

These are expressions, often exclamative, associated with Common Ground/QUD negotiation (78), strong illocution (79), or a QUD-terminating assessment (80). UC could be considered as a similar case of Root SC, modulo the possibility of quoting full sentential (albeit opaque) material in the SubjP.

I believe that UC is also crucial for an understanding of the inferential nature of linguistic negation. Minimal amounts or minimisation, like scalarity, are often grouped among those features which have some kind of semantic solidarity with or dependency from negation. Yet, negation itself sometimes arises as a consequence of pragmatic inferences. An exemplar case of consolidation of a hyponegative interpretation (understood as a negative interpretation arising in the absence of an overt expression of negation, cf. Horn Reference Horn2009) is the negative use of Latin minime ‘minimally’, the superlative of parum, adverbial ‘little’.

Minime can be interpreted as an emphatic, reinforced negation (‘not at all’), also in isolation as a fragment answer. Its original reference to a scalar endpoint can thus be pragmatically maximized to convey emphatic negation. This inference could be explained along the following lines. In the case of fragment answers to yes-no questions, the speaker has the chance to give a positive or negative answer. According to the Maxim of Quality, both are preferable to other less informative answers (as long as truth is preserved). In other words, yes and no (or their cross-linguistic counterparts) are the best (most informative) answers to a yes-no question. Other answers, like those expressing uncertainty or ignorance, are only acceptable when the speaker cannot truthfully provide a polar answer. But with minime, the speaker comes as close as possible to the brink of negation without expressing it. When one is asked, for instance, if they want something or not, it is quaint to answer that they want it ‘minimally’. This almost negative answer is then pushed off the brink by an implicature, which is conventionalised in Latin, to the point that minime can substitute for standard negation as an emphatic negator. If you want or believe something to the least conceivable degree, then you most likely do not want or believe it at all, as the implicature goes.

Thus, minimal quantification can be pragmatically maximised – or minimised – to non-existence and, when applied to a sentence, the discourse effect is equated to that of negation proper. When applied to an utterance, as in the case of Italian metalinguistic objectors, it quantifies its communicative relevance as lowest, thus qualifying it as unworthy of inclusion in the Common Ground. Thus, the outer appearance of Italian metalinguistic objectors is not an idiomatic quirk of language, but rather a reflection of their semantic and pragmatic features.

As a confirmation that these items are indeed minimisers of some kind, consider (82):

These items can be used as arguments and adjuncts in negative sentences in the same capacity as minimisers. More precisely, they belong to the loosely defined category of ‘vulgar minimisers’ (Postal Reference Postal and Postal2004, Garzonio & Poletto Reference Garzonio and Cecilia2008: 65–66) or ‘squatitives’ (Horn Reference Horn, Hoeksema, Rullmann, Sánchez-Valencia and van der Wouden2001, De Clercq Reference De Clercq, Nouwen and Elenbaas2011). In Italian, these minimisers are negative in isolation (though they are not grammatical in preverbal position):

This unusual behaviour shows that vulgar minimisers, as noted by Larrivée (Reference Larrivée2021), are amenable neither to the category of NCIs nor to that of NPIs, but are rather situated along a gradient of negativity (for an alternative approach to the grammar of aggressive expressions in Italian in terms of their association with an EvalP, cf. Giorgi & Poletto Reference Giorgi and Poletto2019). These items are not acceptable in downward-entailing contexts, showing that they are not weak NPIs:

Yet, they seem fine in long-distance configurations:

(88) shows that un cavolo has some ability to convey a sort of (close to) zero interpretation, as similarly observed by Larrivée (Reference Larrivée2021). This is especially common with predicates expressing worth or value, a context in which vulgar minimisers often present a negative or low-scalar interpretation independently from a negative licensor (Zeijlstra Reference Zeijlstra2018):

The possibility of these readings suggests that these items are low-scalar endpoints. Thus, the suggestion that UC is an utterance minimiser receives further corroboration: this expression is, abstractly, simply a minimiser. Whether it is used as an indefinite or as an utterance minimiser depends on its structural usage. When it appears in argument or adjunct position, it functions as a vulgar minimiser, while when it modifies an echoic antecedent, its minimising import is predicated at discourse/pragmatic level, to indicate minimal relevance of the utterance.Footnote 20

5. CC, UC, and the Typology of Peripheral Negators

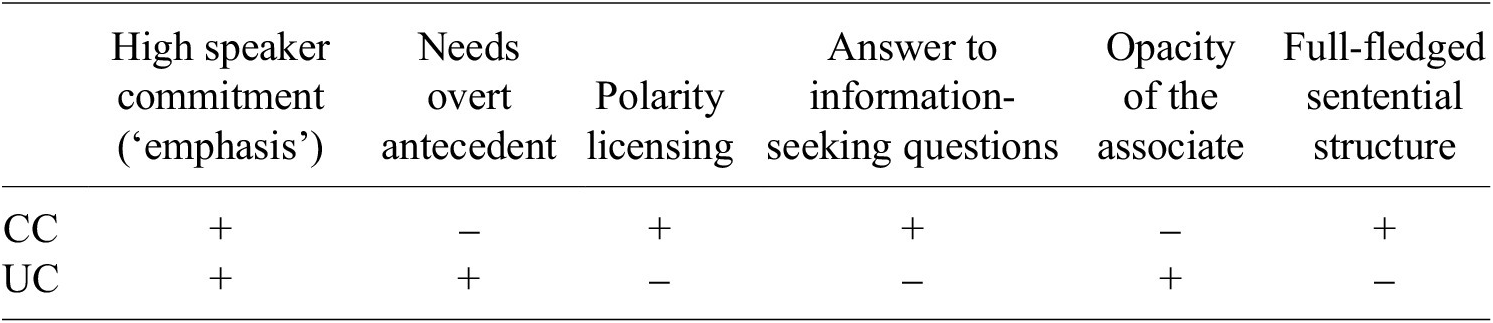

The features of CC and UC are summarised in Table 1, which illustrates how two apparently similar expressions, which could be rashly grouped under the same heading of ‘metalinguistic’ negator, instead instantiate two very different types of objects:

Table 1. Features of CC and UC

These features clearly identify UC as a metalinguistic objector, while CC comes out as an emphatic LPN. The only things they have in common (apart from expressing a disagreement/denial of sorts) are (i) high speaker commitment, and (ii) the occurrence of the same lexeme (cavolo or its variants). I believe these two commonalities are related, since speaker commitment often associates with the emphatic endpoint-referring quality of minimising expressions (Chierchia Reference Chierchia2013).

Where do CC and UC stand with respect to the LPNs described in Section 1? More or less, in the position in which those LPNs stand with respect to each other. For some, a focal position has been proposed (the null negator of fuck-inversion, CC, and no che sentences are brought together by this feature, though the latter are assumed to participate in a biclausal structure), while others are assumed to head their own polar projection (Russian xuj and Irish Demonic Negation):

While as made clear in the previous pages these elements differ in their licensing capabilities, they are all associated with a high commitment on the part of the speaker, which I propose to analyse as the expression of a low degree of strength of sincerity.

As already noted, that the association with the left periphery should be related to a special function or interpretation is not surprising. It was also made with respect to another type of negation which in the literature is assumed to operate on something other than the assertion: expletive negation. It was proposed that expletive negation is not different from truth-conditional negation; rather, it is applied to an implicated, rather than asserted, layer of meaning (Krifka Reference Krifka, Hanneforth and Fanselow2010, Delfitto Reference Delfitto2013, Delfitto et al. Reference Delfitto, Melloni and Vender2019). Greco (Reference Greco2020a, Reference Greco2020b) in particular makes the case that expletive negation is also left-peripheral, a claim developed in particular for the type of Italian expletive negation he terms Surprise Negation:

This mirative negation, Greco proposes, derives its speaker-oriented, emphatic nature from the association with the left periphery, in a dynamic view of syntax in which the interpretation of an operator, including negation, is influenced by or associated with the domain in which it is merged or interpreted. Speaker orientation, or the expression of a certain epistemic attitude, is the thin thread which associates the various types of LPN to the left periphery and between them.

If this is what LPNs have in common, what appears to make the biggest difference among them is whether they associate with the PolP in the lower TP or not. Those which do (no che, fuck-inversion, mutatis mutandis standard negation in Irish and Gbe), by means of movement or agreement chains, are in a sense left-peripheral enrichments, associates, or manifestations of the sentential negation in the TP-layer, while those which are base-generated and have no association with the lower PolP are ‘pure’ LPNs, with limited polarity licensing abilities in the lower clause due to non-locality, and yielding double negation with an independent lower negative PolP. CC belongs to the latter category, and I propose that UC belongs to neither, instead representing a type of objector which I call ‘utterance minimiser’.

I would like to conclude on a diachronic note. Un cavolo (and the original, much coarser un cazzo) is barely attested in writing historically due to its vulgar and colloquial nature, but it surfaces profusely in G.G. Belli’s (1791–1863) Sonetti romaneschi (Belli & Teodonio Reference Belli and Teodonio1998), which reproduce the speech of the lower classes of Rome. Belli uses un cazzo as a vulgar minimiser as in Modern Italian (95), but also as a minimiser in positive contexts (96), and as an emphatic negative adverbial (97)–(98) ((97) is ungrammatical in my contemporary Italian); in this latter use, it could be fronted, thus conveying emphatic negation on its own (99):

Belli also uses UC as an utterance minimiser and as a holophrastic rejector:

We may hypothesise that the uses as a reinforcing associate of sentential negation functioned as a bridging context for the utterance-minimising interpretation of UC.

As for the minimising origin of CC, there is a further very interesting example by Belli:

Crucially, here CC is not yet negative; it rather has a minimising flavour: it means that the situation can be remedied with minimal means. While this is an isolated example, it gives a feel of the original minimising import of CC from which its pragmatic negativisation may have originated.

6. Conclusions

In this paper I discussed two superficially similar expressions in colloquial Italian, col cavolo and un cavolo. My aim was twofold: primarily, (i) to provide an analysis of the similarities and differences between these expressions, showing that they represent two very different strategies, and secondly (ii) to use the structural analysis of CC and UC as a starting point for a cartography of left-peripheral negators, relating their syntax to the nature of their interpretation and functions.

I argued that CC is a left-peripheral negator which is base-generated in FocP – arguably in a biclausal structure like similar Italian non-verbal predicates – or possibly in Krifka’s (Reference Krifka, Hartmann and Wöllstein2023) ComP, which expresses a zero degree of commitment to the truth of the lower proposition. It is syntactically external to the lower proposition. This explains why it can only license weak PIs for which downward entailment or nonveridicality suffice, while being unable to license strong NPIs or NCIs which require a local negative operator. On the other hand, UC is what is termed in previous literature a ‘metalinguistic negator’, a type of objector which I have renamed as ‘utterance minimiser’. I argued that this objector use derives from an extension of its function as a vulgar minimiser: when used in a small clause-like equative structure, in which it follows material copied from an antecedent utterance, UC expresses pragmatic minimisation of the antecedent, predicating its discourse irrelevance. This array of facts explains the opaqueness of the antecedent in terms of modifiability or polarity licensing. What brings together CC and UC is the incorporation of the vulgar minimiser cavolo and its variants, whose reference to a lower endpoint results in an expression of speaker commitment against the inclusion of the lower proposition (CC) or of antecedent material (UC) in the Common Ground.

Typologically, the most relevant generalisations with respect to LPNs and metalinguistic ‘negators’ are the following: (i) their use and interpretation is a function of their structural position and derivation: LPNs which are related to the TP-level PolP, either by movement or agreement, are ‘amphibious’, with the resulting chain having both the features of sentential negation (also in terms of polarity licensing abilities) and the high commitment/discourse-managing function typical of LPNs. Those which are base-generated in the left periphery, on the other hand, have limited polarity licensing capabilities and yield double negation with a lower expression of negative polarity: they are native left-peripheral objects and hence non-local to the lower material. (ii) Metalinguistic ‘negators’ (or at least a subset of them) like UC, uma ova, una mierda, etc., are completely different objects which function as utterance minimisers, participating in an equative structure which predicates minimal conversational/informational worth of a previous utterance (or part thereof).

This analysis is based on a selection of relatively well-attested expressions. Hopefully, future research will expand this picture, further verifying the present generalisation that the structural position and derivational history of LPNs – and the original scalar semantics of utterance minimisers – allow a mapping of their semantic-pragmatic interpretation to their internal composition and external syntax.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a heavily reworked version of the contents and analysis of Chapter 1, Part II of my doctoral dissertation (D’Antuono Reference D’Antuono2024b). It is also, I believe, a considerably improved one, which I owe in no small part to the dedication of the editors and to the careful, insightful, and constructive comments of three anonymous reviewers for JL (who are not to be held responsible for any shortcomings). This research was partly funded by the PRIN Research Grant n. 20222jen3b of the Italian Ministry of University and Research, ‘An integrated approach to negation: Core syntactic processes, lexical structure, and linguistic microvariation’, which is hereby gratefully acknowledged.