Introduction

Depressive symptoms are highly prevalent mental health conditions that can have significant long-term impacts on health and well-being among adolescents (Moukaddam et al., Reference Moukaddam, Cavazos, Nazario, Murtaza and Shah2019). Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a leading cause of global disability, with rates of depressive symptoms among adolescents in the United States rising from 8.1% in 2009 to 15.8% in 2019 and youth depression diagnoses increasing by 56% during this period (Keyes & Platt, Reference Keyes and Platt2024; Santomauro et al., Reference Santomauro, Herrera, Shadid, Zheng, Ashbaugh, Pigott, Abbafati, Adolph, Amlag, Aravkin, Bang-Jensen, Bertolacci, Bloom, Castellano, Castro, Chakrabarti, Chattopadhyay, Cogen, Collins and Ferrari2021; Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Martinez, Chow, Carter, Negriff, Velasquez, Spitzer, Zuberbuhler, Zucker and Kumar2024). Adolescent depressive symptoms are associated with significant impairment in daily functioning, poorer academic outcomes, psychiatric comorbidities, interpersonal relationship problems, and suicidality risk (Clayborne et al., Reference Clayborne, Varin and Colman2019; Kalin, Reference Kalin2021). Furthermore, having the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence is associated with a more severe course of depressive pathology compared to those with later onset, necessitating investigation of what may underlie variations in trajectories of depressive symptoms early in development (Crockett et al., Reference Crockett, Martínez and Jiménez-Molina2020; Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Clark, Van, Collinson and Baune2017). Depressive symptoms are influenced by genetic and environmental factors (e.g., family processes), and the interplay among them (Kwong et al., Reference Kwong, López-López, Hammerton, Manley, Timpson, Leckie and Pearson2019). Yet, prior genetically-informed research has primarily focused on White populations of European ancestry (EA) and rarely investigated gene–environment interplay in adolescent depressive symptom trajectories. The current study addressed these limitations of the literature by examining how polygenic scores for major depressive disorder (MDD-PGS) influenced trajectories of depressive symptoms among a sample of Black, Latinx, and White adolescents and investigating how family conflict and parental acceptance may act as moderating and/or mediating mechanisms through which polygenic risk predicts trajectories of depressive symptoms.

Trajectories of depressive symptoms

Prior research suggests depressive disorders often develop during adolescence and that adolescents may follow different trajectories of depressive symptoms (Grimes et al., Reference Grimes, Adams, Thng, Edmonson-Stait, Lu, McIntosh, Cullen, Larsson, Whalley and Kwong2024; Kwong et al., Reference Kwong, López-López, Hammerton, Manley, Timpson, Leckie and Pearson2019; Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Clark, Van, Collinson and Baune2017). Musliner and colleagues (Reference Musliner, Munk-Olsen, Eaton and Zandi2016) found that most studies identify three to four different depressive trajectories for adolescents, where youth often fall into a low-risk, moderate-stable, elevated/increasing, or decreasing trajectories (Musliner et al., Reference Musliner, Munk-Olsen, Eaton and Zandi2016). While most adolescents belong to low-risk groups, variations in trajectories emerge by the severity of symptoms (i.e., low, medium, high) and persistence (i.e., increasing, stable, decreasing) of depressive symptoms. Black, Hispanic, and Asian adolescents have been found to be at greater risk of following trajectories with elevated depressive symptoms (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Swendsen, Rose and Dierker2008). Elam and colleagues leveraged the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study and utilized growth mixture modeling to categorize varying trajectory patterns across Black (3 classes), Latinx (2 classes), and White adolescents (4 classes) (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024). Across racial/ethnic groups, high-risk and low-risk trajectories were observed. We aim to further expand on these findings with the ABCD 5.0 data release, which includes full information from baseline to the 3-year follow-up and examines how polygenic risk for MDD, with a larger and more ancestrally diverse GWAS, interplays with family and parenting processes through both gene–environment interaction (GxE) and gene–environment correlation (rGE) processes to predict membership in depressive trajectories among Black, Latinx, and White adolescents.

Gene–environment interplay and adolescent depressive symptoms

Past research demonstrates that MDD is heritable, with twin studies demonstrating moderate heritability estimates of around 30-50% (Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Assche, Andlauer, Choi, Luykx, Schulte and Lu2021), highlighting the importance of both genetic predispositions and the environment. Genome wide association studies (GWAS) demonstrate that MDD is polygenic, influenced by hundreds of genetic risk variants (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Adams, Clarke, Hafferty, Gibson, Shirali, Coleman, Hagenaars, Ward, Wigmore, Alloza, Shen, Barbu, Xu, Whalley, Marioni, Porteous, Davies, Deary and McIntosh2019). However, few studies have used PGS to examine longitudinal trajectories of depressive symptoms among youth (Morneau-Vaillancourt et al., Reference Morneau-Vaillancourt, Palaiologou, Polderman and Eley2025). Prior research in European-descent adults has found PGS for depression and parental conflict to be associated with higher-risk and more persistent trajectories of depressive symptoms (Kwong et al., Reference Kwong, López-López, Hammerton, Manley, Timpson, Leckie and Pearson2019). Similarly, MDD-PGS has been found to predict intercept-levels, but not linear or quadratic changes, in depressive symptoms among Dutch adolescents (Nelemans et al., Reference Nelemans, Boks, Lin, Oldehinkel, van Lier, Branje and Meeus2021). Past cross-sectional research has found MDD-PGS to predict depressive outcomes among African ancestry and Latinx-ancestry adolescents and adults (Ahern et al., Reference Ahern, Thompson, Fan and Loughnan2023; Cha et al., Reference Cha, Lee, van Dijk, Kim, Kim, Murphy, Talati, Joo and Weissman2024; Kanjira et al., Reference Kanjira, Adams, Jiang, Tian, Lewis, Kuchenbaecker and McIntosh2025; Rabinowitz et al., Reference Rabinowitz, Campos, Benjet, Su, Macias-Kauffer, Méndez, Martinez-Levy, Cruz-Fuentes and Rentería2020). However, prior longitudinal studies investigating MDD-PGS as predictors of adolescent depressive trajectories in the ABCD study has found significant effects among European-ancestry but not Black or Latinx youth, which may be attributed to the use of smaller and less-diverse GWAS (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024; Grimes et al., Reference Grimes, Adams, Thng, Edmonson-Stait, Lu, McIntosh, Cullen, Larsson, Whalley and Kwong2024). GxE and rGE are two important frameworks employed to explore the interplay between genetic factors and environmental influences in the development of mental disorders (Price & Jaffee, Reference Price and Jaffee2008). With GxE, the effects of genetic factors on traits or outcomes are modified by environmental factors (Plomin et al., Reference Plomin, DeFries and Loehlin1977). Prior candidate gene-based studies, in samples of predominantly European-ancestry groups, have indicated significant GxE effects between genetic risk for depressive symptoms and family-level environmental stressors such as childhood maltreatment and family stress, however many of these effects have failed to replicate with larger samples (Border et al., Reference Border, Johnson, Evans, Smolen, Berley, Sullivan and Keller2019; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Uddin, Subramanian, Smoller, Galea and Koenen2011).

Utilizing PGS, Cleary and colleagues (Cleary et al., Reference Cleary, Fang, Zahodne, Bohnert, Burmeister and Sen2023) found that adults of EA who were at high polygenic risk for MDD reported greater depressive symptoms in the absence of social support and reported fewer depressive symptoms in the presence of social support when compared to their peers with low polygenic risk for MDD. Moreover, Elam et al. (Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024) found evidence of a GxE interaction between MDD-PGS and socioeconomic status among Black youth, such that polygenic risk for MDD predicted greater likelihood of being in the decreasing class when compared to the low-risk class for youth in families with lower household incomes (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024). Overall, prior research is inconclusive on the role of GxE in adolescent depressive symptoms (Morneau-Vaillancourt et al., Reference Morneau-Vaillancourt, Palaiologou, Polderman and Eley2025). There is limited prior research utilizing PGS to investigate GxE in developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms among adolescents and polygenic research for depression has been investigated in predominantly European-ancestry populations (Belsky & Domingue, Reference Belsky and Domingue2023; Border et al., Reference Border, Johnson, Evans, Smolen, Berley, Sullivan and Keller2019; Kwong et al., Reference Kwong, López-López, Hammerton, Manley, Timpson, Leckie and Pearson2019). Further research is essential to explore how environmental context can strengthen or weaken the influence of MDD-PGS on depressive symptom trajectories across racially/ethnically diverse groups of adolescents.

In contrast, rGE posits that individuals with a genetic predisposition for MDD can influence their exposure to certain environmental factors through either 1) passive rGE, which occurs when individuals inherits genes from parents and the individuals’ environment is shaped by their parents genes; 2) active rGE, when an individual actively selects certain environments due to their genetic predispositions; or 3) evocative rGE, when an individual modifies their environment by evoking reactions from others due to their genetic predispositions (Cheesman et al., Reference Cheesman, Eilertsen, Ahmadzadeh, Gjerde, Hannigan, Havdahl, Young, Eley, Njølstad, Magnus, Andreassen, Ystrom and McAdams2020). Prior research has found adolescent polygenic risk for depressive symptoms to be correlated with elevated stress exposure and interpersonal stress among Dutch youth (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Docherty, Finsaas, Kotov, Shabalin, Waszczuk, Katz, Davila and Klein2023). These findings suggest that adolescents with greater genetic risk for MDD may be more likely to experience interpersonal stressful experiences, such as family conflict and lower-perceived parental acceptance. The gene–environment cascade theoretical framework posits that youth with greater genetic risk for MDD may evoke more aversive environments and parenting, which exacerbates their own risk for psychopathology over time (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Lemery-Chalfant and Chassin2023). For example, polygenic risk for depressive symptoms was associated with more MDD symptoms among European-American adolescents through lower levels of parental knowledge (Su et al., Reference Su, Kuo, Bucholz, Edenberg, Kramer, Schuckit and Dick2018). Further investigation is required to examine how family processes may mediate the relationship between genetic risk for MDD and depressive trajectories in youth.

The role of family environment

Prior meta-analyses demonstrate that adolescents raised in households with high parental support and warmth are more likely to experience lower levels of depressive symptoms and better mental well-being across racial/ethnic backgrounds (Khaleque, Reference Khaleque2013; Li & Meier, Reference Li and Meier2017; Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017). Whereas high amounts of family conflict within the home increase risk for the development of depressive symptoms across Black, Latinx, and White youth (Choe et al., Reference Choe, Stoddard and Zimmerman2014; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Spiro, Young, Gibb, Hankin and Abela2015; Montoro & Ceballo, Reference Montoro and Ceballo2021; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Padilla-Walker, McLean and Hurst2020). Parent–child relationship problems have been found to be a significant indicator of high-risk and increasing depressive trajectories across youth (Shore et al., Reference Shore, Toumbourou, Lewis and Kremer2018). The family environment may serve to exacerbate or buffer genetic risk for depressive symptoms in children, that is, a GxE, but past research is currently inconclusive. Utilizing a longitudinal twin-design of predominantly European-ancestry adolescents, Rice and colleagues (Reference Rice, Harold, Shelton and Thapar2006) found that genetic factors had a greater effect on predicting depressive symptoms for adolescents when family conflict was high (Rice et al., Reference Rice, Harold, Shelton and Thapar2006). However, many of the prior significant GxE results for depressive symptoms have typically focused on adverse child experiences in samples of European-descent (Assary et al., Reference Assary, Vincent, Keers and Pluess2018; Border et al., Reference Border, Johnson, Evans, Smolen, Berley, Sullivan and Keller2019). Meta-analytic studies have failed to reveal significant interactive effects between MDD-PGS, childhood adversity, and depressive outcomes (Peyrot et al., Reference Peyrot, Van der Auwera, Milaneschi, Dolan, Madden, Sullivan, Strohmaier, Ripke, Rietschel, Nivard, Mullins, Montgomery, Henders, Heat, Fisher, Dunn, Byrne, Air, Wray and Penninx2018). However, Mullins et al. (Reference Mullins, Power, Fisher, Hanscombe, Euesden, Iniesta, Levinson, Weissman, Potash, Shi, Uher, Cohen-Woods, Rivera, Jones, Jones, Craddock, Owen, Korszun, Craig and Lewis2016) found that, among a clinical sample of European-ancestry adults, adverse childhood experiences had the greatest effect on depressive symptoms among those with lower polygenic risk scores for MDD compared to those with high polygenic risk (Mullins et al., Reference Mullins, Power, Fisher, Hanscombe, Euesden, Iniesta, Levinson, Weissman, Potash, Shi, Uher, Cohen-Woods, Rivera, Jones, Jones, Craddock, Owen, Korszun, Craig and Lewis2016). Prior studies, to the best of our knowledge, have not examined how family conflict and parental acceptance may interact with MDD-PGS to predict trajectories of depressive problems across Black, Latinx, or White adolescents. The unique methodology of the present study lies in its 1) longitudinal design to investigate trajectories of depression, 2) focus on a racially and ethnically diverse sample of early adolescents, and 3) examination of positive and negative aspects of family environments and parenting in gene–environment interplay. A study conducted Nelemans and colleagues (Reference Nelemans, Boks, Lin, Oldehinkel, van Lier, Branje and Meeus2021) revealed a significant GxE between MDD-PGS and parental criticism among Dutch adolescents, such that those with greater MDD-PGS were more likely to have more severe depressive outcomes if they experienced frequent critical parenting (Nelemans et al., Reference Nelemans, Boks, Lin, Oldehinkel, van Lier, Branje and Meeus2021). Thus, family conflict and parental acceptance may serve to exacerbate or buffer, respectively, the effect of MDD-PGS on depressive trajectories of Black, Latinx, and White adolescents.

The gene–environment cascade framework posits that genetic risk for depressive symptoms in children may increase risk for depression through exposure to negative environments, via rGE (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Lemery-Chalfant and Chassin2023). Although parenting behaviors may buffer children’s internalizing outcomes, children’s genetics can also influence parenting and the parent–child relationship as well (Cheesman et al., Reference Cheesman, Eilertsen, Ahmadzadeh, Gjerde, Hannigan, Havdahl, Young, Eley, Njølstad, Magnus, Andreassen, Ystrom and McAdams2020; Machlitt-Northen et al., Reference Machlitt-Northen, Keers, Munroe, Howard, Trubetskoy and Pluess2022). MDD-PGS have been associated with family processes such as lack of parental involvement, lower parental knowledge, and greater family conflict in European-Ancestry youth (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Wiste, Radmanesh, Almli, Gogarten, Sofer, Faul, Kardia, Smith, Weir, Zhao, Soare, Mirza, Hek, Tiemeier, Goveas, Sarto, Snively, Cornelis and Smoller2016; Ensink et al., Reference Ensink, de Moor, Zafarmand, de Laat, Uitterlinden, Vrijkotte, Lindauer and Middeldorp2020; Machlitt-Northen et al., Reference Machlitt-Northen, Keers, Munroe, Howard, Trubetskoy and Pluess2022; Su et al., Reference Su, Kuo, Bucholz, Edenberg, Kramer, Schuckit and Dick2018). However, there is a lack of literature utilizing PGS to test how adolescent-perceived parental acceptance and family conflict may function as a mediator in associations between MDD genetic risk and depressive symptom trajectories, particularly among racially and ethnically minoritized youth.

Racial–ethnic differences in family context and depressive outcomes

Cultural norms and values, and socioeconomic factors can influence parenting practices and shape racial/ethnic differences in parent–child relationships (Khoury-Kassabri & Straus, Reference Khoury-Kassabri and Straus2011; Le et al., Reference Le, Ceballo, Chao, Hill, Murry and Pinderhughes2008; Rothenberg et al., Reference Rothenberg, Lansford, Bornstein, Chang, Deater-Deckard, Di Giunta, Dodge, Malone, Oburu, Pastorelli, Skinner, Sorbring, Steinberg, Tapanya, Uribe Tirado, Yotanyamaneewong, Alampay, Al-Hassan and Bacchini2020). For example, racial/ethnic and cultural norms in family obligations, parent–child closeness, and adolescent autonomy may underlie variations in the relationship between parenting behaviors and adolescent mental health outcomes (Cahill et al., Reference Cahill, Updegraff, Causadias and Korous2021; Rothenberg et al., Reference Rothenberg, Lansford, Bornstein, Chang, Deater-Deckard, Di Giunta, Dodge, Malone, Oburu, Pastorelli, Skinner, Sorbring, Steinberg, Tapanya, Uribe Tirado, Yotanyamaneewong, Alampay, Al-Hassan and Bacchini2020). Past research highlights that racially and ethnically minoritized adolescents are more likely to report elevated depressive symptoms and are less likely to receive mental health treatment than White adolescents (Alegria et al., Reference Alegria, Vallas and Pumariega2010; López et al., Reference López, Barrio, Kopelowicz and Vega2012). These findings underscore the need to explore differences across racially/ethnically diverse samples of youth when assessing the impact of family processes on developmental outcomes.

Underrepresentation of racial/Ethnic minoritized populations in behavioral genetics research

Behavioral genetics has made notable progress in uncovering the genetic foundations of complex traits and diseases, particularly through the use of cutting-edge genome-wide polygenic score methods. However, most GWAS have focused on samples of primarily EA (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019). As a result, the PGS derived from these studies may not accurately represent the genetic architecture of non-EA populations, limiting the generalizability and applicability of these scores to diverse populations and potentially exacerbating preexisting health disparities. Utilizing large and diverse GWAS and leveraging genetic information from multiple ancestral groups through methods such as PRS-CSx increases the predictive performance of PGS in diverse and admixed populations (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Sadeeq, Kumuthini, Ajayi, Wells, Solomon, Ogunlana, Adetiba, Iweala, Brors and Adebiyi2023; Ahern et al., Reference Ahern, Thompson, Fan and Loughnan2023; Gunn & Lunetta, Reference Gunn and Lunetta2024; Ruan et al., Reference Ruan, Lin, Feng, Chen, Lam, Guo, He, Sawa, Martin, Qin, Huang and Ge2022). While, past research has found MDD-PGS to predict depressive outcomes among African-ancestry and Latinx-ancestry adolescents, these studies have often been cross-sectional in nature and have not examined how MDD-PGS may interplay with family and parenting variables to predict depressive trajectories. (Ahern et al., Reference Ahern, Thompson, Fan and Loughnan2023; Cha et al., Reference Cha, Lee, van Dijk, Kim, Kim, Murphy, Talati, Joo and Weissman2024; Kanjira et al., Reference Kanjira, Adams, Jiang, Tian, Lewis, Kuchenbaecker and McIntosh2025; Rabinowitz et al., Reference Rabinowitz, Campos, Benjet, Su, Macias-Kauffer, Méndez, Martinez-Levy, Cruz-Fuentes and Rentería2020). Doing so is important, as family processes are an important component of adolescent development (Buehler, Reference Buehler2020). We aim to examine the utility of polygenic risk scores in predicting depressive trajectories among racially and ethnically minoritized youth and gene–environment interplay with the family environment in predicting trajectories of depressive symptoms across Black, Latinx, and White youth (Belsky & Domingue, Reference Belsky and Domingue2023).

Current aims

The aims of the present study are multifold: First, we aimed to identify depressive symptom trajectories from late childhood (Time 1; 9 – 10 years old) to early adolescence (Time 4; 12 – 13 years old) using latent growth curve analysis and growth mixture modeling among groups of Black, Latinx, and White adolescents. Second, the study aimed to test whether adolescents with higher polygenic risk scores for adult-MDD (MDD-PGS), lower adolescent-perceived parental acceptance, and greater family conflict, were at greater risk of being higher-risk trajectories of depressive symptoms.

Third, we examined how family conflict and parental acceptance at Time 1 may interact with MDD-PGS (GxE) to predict depressive symptom trajectories. We hypothesized that the association between MDD-PGS and odds of following higher risk trajectories of depressive symptoms would be stronger for youth who experience lower levels of parental acceptance or higher levels of family conflict, compared to those with higher levels of parental acceptance or lower levels of family conflict.

Finally, this study aimed to test how parental acceptance and family conflict may mediate the relationship between MDD-PGS and trajectories of depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that higher MDD-PGS would be associated with higher-risk trajectories through lower parental acceptance and greater family conflict.

Method

Participants

The present study leveraged the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, a large-scale longitudinal, multisite study in the United States that recruited 11,875 adolescents and their primary caregivers. The ABCD Study collected extensive genetic, neurological, behavioral, sociocultural, and family measures to better understand developmental pathways across adolescence. To approximate the racial and ethnic composition of adolescents in the United States, the study utilized a multistage sampling strategy. This approach consisted of selecting 21 study sites across the nation, using probability sampling to choose schools within each site, and recruiting eligible children based on demographic data from annual school enrollment records for 3rd and 4th grades from the National Center for Education Statistics and the American Community Survey (ACS) (Garavan et al., Reference Garavan, Bartsch, Conway, Decastro, Goldstein, Heeringa, Jernigan, Potter, Thompson and Zahs2018). The ABCD Study received ethical approval from the institutional review board (IRB) of the University of California, San Diego, with each study site obtaining additional approval from their respective IRBs. Written informed consent was obtained from all primary caregivers, and verbal assent was provided by all participating adolescents. Data for the current study were drawn from ABCD Data Release 5.0.

Procedures

The ABCD Study is a large longitudinal study that collects data annually. For the present study, data from the baseline (Time 1), 1-year follow-up (Time 2), the 2-year follow-up (Time 3), and the 3-year follow-up (Time 4) assessments were used from adolescents who identified as Non-Hispanic Black (“Black”), Hispanic/Latinx (“Latinx”), and Non-Hispanic White (“White”). Other racial/ethnic groups were not included due to small sample sizes. The analytic sample included a total of 10,486) adolescents (Time 1; Mage = 9.92 years, 47.4% female; Black = 1,769; Latinx = 2,258 White = 6,459, Follow-up data was collected approximately one, two, and three years later (Time 2, Time 3, Time 4) when adolescents were between 10 – 11, 11 – 12, and 12 – 13 years old. Adolescents reported on parental acceptance and family conflict within the home and whereas primary caregivers reported on their child’s depressive symptoms.

At Time 1, saliva samples were collected and then transferred from the collection site to the Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository (RUCDR) for genotyping. (Uban et al., Reference Uban, Horton, Jacobus, Heyser, Thompson, Tapert, Madden and Sowell2018). The genotyping of the samples was performed using the Smokescreen Genotyping Array. (Baurley et al., Reference Baurley, Edlund, Pardamean, Conti and Bergen2016). The genotyping array was analyzed, quality controlled, phased, and imputed using cutting-edge methods. After quality-control, 11,0999 unique individuals and 516,598 unique genetic variants remained in the ABCD study. Imputation was performed via the TOPMed imputation server using mixed ancestry and Engle v2.4 phasing. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) were excluded from analysis if they had a genotyping rate of below 0.95, a minor allele frequency of below 0.01, or were in violation of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p < 10 − 6).

Measures

Adolescent depressive symptoms

Adolescent depressive symptoms were reported using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) which is a 113-item parent-report questionnaire on children’s emotions and behaviors over the past 6 months (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach, Kreutzer, DeLuca and Caplan2011). A depressive symptoms scale was constructed based on CBCL items that align with the DSM-5 criteria for depressive disorders. (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach2013). At each assessment, parents reported the degree to which various behaviors were present in their children through the use of a 3-point Likert scale (0 = not true; 2 = very true or often true). Example items are feeling too guilty, lacking energy, and enjoying little. Adolescent depressive symptom scores were created by taking the sum of 14 DSM-5 oriented items for depressive symptoms at all time points (Cronbach’s alpha T1: Black = .71, Latinx = .73, White = .71; T2: Black = .75, Latinx = .73, White = .74; T3: Black = .73, Latinx = .77, White = .75; T4: Black = .77, Latinx = .79, White = .78).

Parental acceptance

Parental acceptance was assessed through adolescent report using acceptance using 5 items from the Child’s Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory (Schaefer, Reference Schaefer1965). Adolescents rated the degree to which they agreed with various statements about their primary caregiver on a 3-point Likert Scale (1 = Not like him/her; 3 = A lot like him/her). A mean-score was calculated by averaging across items which asked such as “My parent is easy to talk to” or “My parent smiles at me very often.” The measure was found to have acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha: Black = .71, Latinx = .72, White = .71).

Family conflict

At Time 1, youth completed 9 true/false items using the Family Environment Scale-Conflict Subscale (Moos & Moos, Reference Moos and Moos1986), to assess the expression of anger and the frequency of conflict within the family. Composite scores were created by summing across items and example items included “Family members sometimes get so angry they throw things” and “Family members often criticize each other.” The internal consistency was found to be acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha: Black = .68, Latinx = .64, White = .67).

Polygenic scores for major depressive disorder (MDD-PGS)

Previous research shows that the effectiveness and reliability of PGS are primarily influenced by the statistical power and sample size of the discovery GWAS, as well as the ancestral similarities between the target and discovery samples (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Kuchenbaecker, Walters, Chen, Popejoy, Periyasamy, Lam, Iyegbe, Strawbridge, Brick, Carey, Martin, Meyers, Su, Chen, Edwards, Kalungi, Koen, Majara and Duncan2019). MDD-PGS were calculated based on summary statistics from the largest published trans-ancestry GWAS of depression conducted by the Major Depressive Working Group of the Psychiatric Genetics Consortium (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Streit, Meng, Awasthi, Adey, Choi, Chundru, Coleman, Ferwerda, Foo, Gerring, Giannakopoulou, Gupta, Hall, Harder, Howard, Hübel, Kwong, Levey and McIntosh2025). In this GWAS, 688,808 participants with major depression and 4.3 million controls were meta-analyzed across 109 studies. The GWAS sample contained 3,887,532 EA participants, 131,996 African Ancestry (AA), 340,403 Hispanic/Latin American Ancestry participants (LA), 368,328 East Asian participants, 29,682 South Asian participants, and 272,165 mixed ancestry participants. MDD-PGS were calculated for Black, Latinx, and White adolescents utilizing PRS-CSx after filtering and matching across the discovery GWAS sample, the 1000 Genomes reference sample, and the ABCD participants. PRS-CSx is a Bayesian regression and shrinkage technique that uplifts GWAS summary statistics from multiple ancestries and results in more precise estimates compared to traditional methods of polygenic score construction and PRS-CS (Ruan et al., Reference Ruan, Lin, Feng, Chen, Lam, Guo, He, Sawa, Martin, Qin, Huang and Ge2022). To account for genetic admixture and population stratification, ABCD participants were first assigned to ancestral groups based on principal components derived from the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 reference populations (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Zheng-Bradley, Smith, Kulesha, Xiao, Toneva, Vaughan, Preuss, Leinonen, Shumway, Sherry and Flicek2012). Principal components were then calculated within each subgroup to account for within-ancestry stratification (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024). MDD-PGS scores were calculated using PLINK 1.9 and both PRS-CSx and PRS-CSx Meta scores were calculated (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Chow, Tellier, Vattikuti, Purcell and Lee2015; Ruan et al., Reference Ruan, Lin, Feng, Chen, Lam, Guo, He, Sawa, Martin, Qin, Huang and Ge2022). PRS-CSx produces ancestry-specific posterior SNP effect sizes whereas PRS-CSx Meta produces a single set of posterior effects through inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis (Ahern et al., Reference Ahern, Thompson, Fan and Loughnan2023; Ruan et al., Reference Ruan, Lin, Feng, Chen, Lam, Guo, He, Sawa, Martin, Qin, Huang and Ge2022). PRS-CSx and PRS-CSx Meta have shown improved performance in predicting depressive outcomes among African, European, and admixed ancestry youth in the ABCD study (Ahern et al., Reference Ahern, Thompson, Fan and Loughnan2023; Cha et al., Reference Cha, Lee, van Dijk, Kim, Kim, Murphy, Talati, Joo and Weissman2024). For Black youth, the meta-analyzed European and African ancestry scores best predicted depressive symptoms. For Latinx youth, the meta-analyzed European and Hispanic/Latin American-ancestry scores best predicted depressive symptoms. For White youth, the European-ancestry aligned PGS best predicted depressive symptoms. In order to account for population stratification and genetic admixture across racial/ethnic groups, residualized polygenic risk scores were used, which regressed out the top 10 principal components representing genetic ancestry.

Covariates

Participants’ demographic characteristics (e.g., biological sex, puberty) may influence the development of depressive symptoms (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Yang, Li and Yuan2021). Adolescents self-reported on their sex (i.e., Male, Female, Other). Due to the low prevalence of those identifying as “Other,” sex was coded as 0 = Male, 1 = Female. Caregivers reported on their adolescent’s race/ethnicity and age. Parental education was calculated by averaging parental education level across both caregivers. Data was used from only one caregiver when education status was not available for both. Adolescent completed the 5-item Pubertal Development Scale at T1 and T3, which asks adolescents to rate their pubertal development on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = has not yet started, 4 = seems to have completely changed) (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Magis-Weinberg, Guazzelli Williamson, Ladouceur, Whittle, Herting, Uban, Byrne, Barendse, Shirtcliff and Pfeifer2021; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Crockett, Richards and Boxer1988). Similar (e.g., body hair) and sex-specific items were summed across males and females such as items on facial hair development, menstruation, and deepening voices.

Data analysis

Preliminary analyses, descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and ANOVAs were carried out using SPSS 29.0. ANOVAs were conducted to examine mean-level differences in study variables between participants with and without missing data at T2, T3, and T4. Missing data was addressed using multiple imputation (Li et al., Reference Li, Stuart and Allison2015). Specifically, independent variables were imputed 20 times for each racial/ethnic group using Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation in Mplus (8.0) (Gelman & Rubin, Reference Gelman and Rubin1996; Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, White, Carlin, Spratt, Royston, Kenward, Wood and Carpenter2009). All following models were conducted in Mplus (8.0)

Latent growth curve analysis was conducted for Black, Latinx, and White adolescents in parallel models to examine if growth mixture modeling was necessary to assess heterogeneity in depressive symptom trajectories. After discovering statistically significant variance in intercepts, linear slopes, and quadratic slopes for Black, Latinx, and White youth, growth mixture models were conducted in parallel models for White, Black, and Latinx adolescents, to allow for examination of potential racial/ethnic differences in the effects of PGS for MDD and family variables in predicting class membership (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019). The study utilized growth mixture modeling to determine class membership of participants by trajectories of depressive symptoms at T1 (9 – 10 years), T2 (10 – 11 years), T3 (11 – 12 years) and T4 (12 – 13 years). Intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope were specified in all models. Growth mixture modeling was performed iteratively, starting with a 1-class model and progressively increasing to a 6-class model. Model fit selection for number of classes was based on various model fit indices where preference was given to lower Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayes Information Criterion (BIC) values, significant Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio testing, entropy (values closer to 1 indicate clearer delineation of classes), sample size of classes, interpretability, and theory as metrics for class selection (Vermunt, Reference Vermunt2024).

After class selection, multinominal logistic regressions, using the R3Step method in Mplus, were conducted to examine associations between MDD-PGS, family conflict, parental acceptance, covariates and odds of trajectory class membership (Asparouhov & Muthen, Reference Asparouhov and Muthen2014). The R3step approach is recommended as it first estimates latent classes before estimating the effect of variables on class-membership. To test for GxE interactions we included interaction terms created by multiplying MDD-PGS with mean-centered family conflict (MDD-PGS × family conflict) and MDD-PGS with mean-centered parental acceptance (MDD-PGS × parental acceptance) to the models. To test for rGE, mediation analyses with logistic regression were conducted such that parental acceptance and family conflict were tested as mediators in the association between MDD-PGS and trajectory class membership. Following recommendations from Hsiao and colleagues (Reference Hsiao, Kruger, Lee Van Horn, Tofighi, MacKinnon and Witkiewitz2021) on conducting latent class mediation models, trajectory latent class membership was extracted as an observed variable (rather than latent) and mediation models were examined by alternating the trajectory reference class in each model, to estimate indirect effects across all classes (e.g., Model 1: reference group = Class 1, Model 2= reference group = Class 2) (Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Kruger, Lee Van Horn, Tofighi, MacKinnon and Witkiewitz2021). Indirect effects were tested using MODEL INDIRECT in Mplus, with indirect effects estimated by bootstrapping 5,000 times (Shrout & Bolger, Reference Shrout and Bolger2002). Due to software constraints, missing data was estimated using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation procedures rather than multiple imputation in the mediation models.

Results

Descriptive statistics

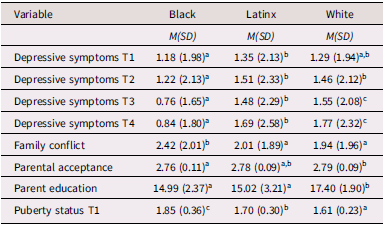

Mean levels of variables are presented in Table 1 and bivariate correlations are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Overall, low levels of depressive symptoms were observed across adolescents. Black adolescents reported fewer depressive symptoms than both Latinx and White adolescents at all timepoints. Latinx and White adolescents, on average, reported lower family conflict than Black adolescents. White adolescents reported significantly higher parental acceptance than Black or Latinx adolescents. Higher average parental education was observed among White adolescents than Black and Latinx adolescents. Black adolescents reported significantly higher levels of pubertal development at T1 than White and Latinx adolescents. Latinx adolescents reported significantly higher pubertal development at T1 than White adolescents. Families with missing data at T2-T4 were more likely to report lower parental education and greater pubertal development at T1. Black and Latinx families were more likely to have missing data. Families with missing data at later time points (i.e., T3 and T4) reported lower levels of parental acceptance in addition to greater family conflict. Families with missing data at T4 reported greater adolescent depressive symptoms at T1 and T3.

Table 1. Differences across race/ethnicity for study variables

Note. Different superscript values represent significant differences in mean-levels across racial/ethnic groups at p < .01.

Latent growth curve analysis

Latent growth curve analyses revealed significant variation in the linear and quadratic slopes of depressive symptoms for Black, Latinx, and White youth (Supplemental Table 2). Linear and quadratic slope estimates were nonsignificant for Latinx and White youth. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine whether MDD-PGS and family-level variables predicted intercept and slopes of depressive symptoms (Supplemental Table 3). MDD-PGS and family conflict predicted greater intercept-levels of depressive symptoms among Black, Latinx, and White adolescents. Parental acceptance predicted lower intercept-levels of depressive symptoms among Latinx and White, but not Black adolescents. Among White adolescents, MDD-PGS predicted a positive linear slope and negative quadratic slope, whereas family conflict predicted a negative linear slope. Among White and Latinx adolescents, being female predicted greater quadratic slopes of depressive symptoms. No variables predicted linear slopes among Black and Latinx youth nor quadratic slopes of depressive symptoms among Black youth.

Growth mixture modeling

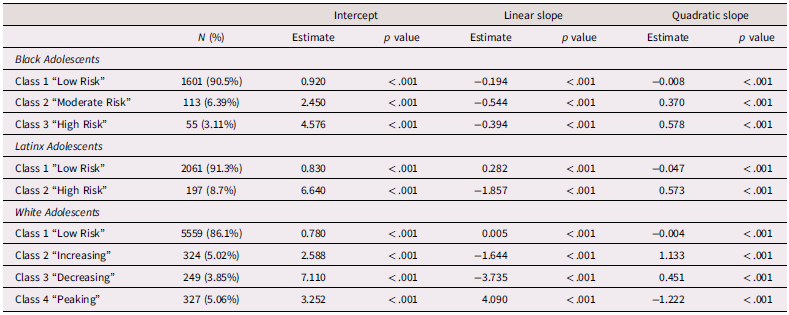

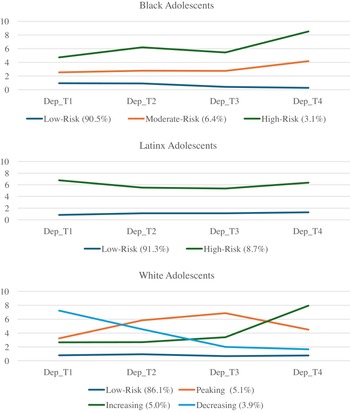

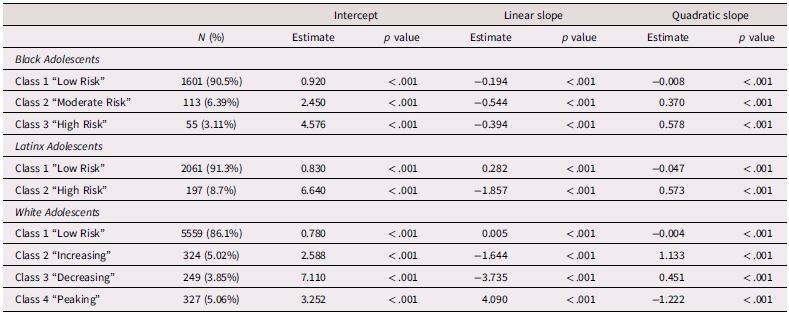

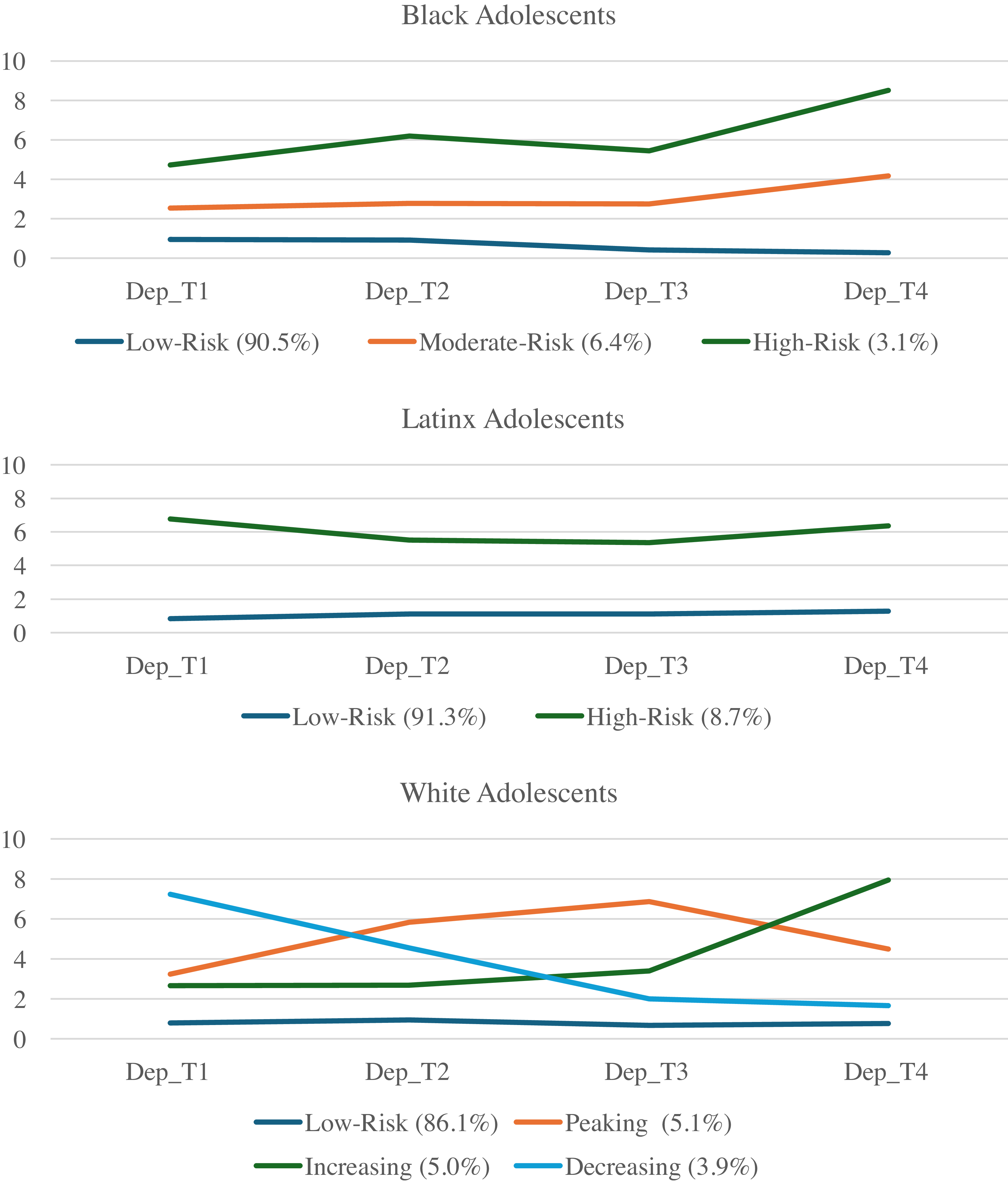

Due to the significant levels of linear and quadratic variance and lack of significant linear and quadratic slopes, growth mixture modeling was conducted beginning with a 1-class solution which was iteratively increased to 6 classes to find the best fitting model for the data (Supplemental Table 4). Classes were chosen based on comparison of AIC/BIC values, entropy, and the presence of significant p-values from Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Testing. Consistent with Elam et al. (Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024), for Black adolescents, three classes emerged which included a low risk (Class 1, n = 1,601 90.5%), a moderate risk (Class 2, n = 113, 6.39%), and a high-risk (Class 3, n = 55, 3.11%) class. For Latinx adolescents, two classes emerged which included a low-risk trajectory (Class 1, n = 2,061, 91.3%) and high-risk trajectory (Class 2, n = 197, 8.7%) class. For White adolescents, four classes emerged which included a low risk (Class 1, n = 5,559, 86.1%), increasing (Class 2, n = 324 5.02%), decreasing, (Class 3, n = 249, 3.85%), and “peaking” group which increased from T1 – T2 but decreased from T2 – T4 (Class 4, n = 327, 5.06%). Class trajectories and estimated class means, linear slopes, and quadratic slopes are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2. Class characteristics of Adolescent depressive trajectories

Figure 1. Trajectories of depressive symptoms across Black, Latinx, and White adolescents.

Main effects of MDD-PGS and family processes on trajectories of depressive symptoms

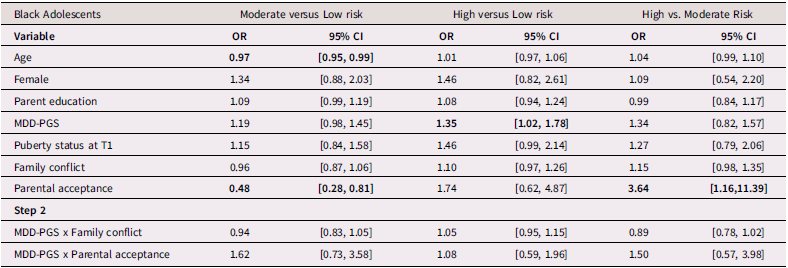

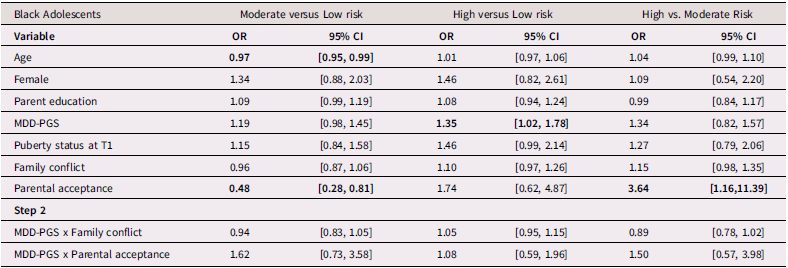

Black adolescents

Table 3 presents findings (odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals) from the multinomial logistic regression for Black adolescents. Among Black adolescents, MDD-PGS predicted greater odds of being in the high-risk class versus the low-risk class. Higher adolescent-perceived parental acceptance was associated with greater odds of being in the low-risk and high-risk versus the moderate-risk depressive trajectory. Family conflict was not associated with trajectories of depressive symptoms.

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression and interaction for Black Adolescent depressive trajectories

Note. OR = Odds ratio, CI = 95% Confidence Interval, MDD-PGS = Major Depressive Disorder Polygenic Risk Score. Bolded values represent statistically significant findings.

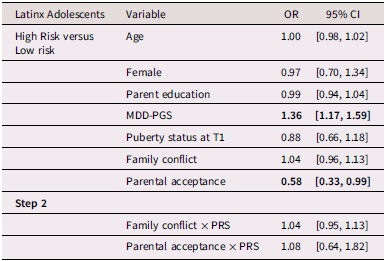

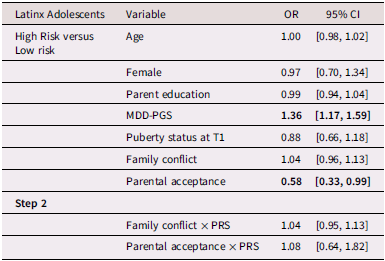

Latinx adolescents

Table 4 presents multinomial logistic regression results for Latinx adolescents. Among Latinx adolescents, MDD-PGS was associated with greater odds of being in the high-risk versus the low-risk class. Family conflict was not associated with trajectory membership. Greater adolescent-perceived parental acceptance was associated with higher odds of being in the low-risk versus the high-risk depressive trajectory.

Table 4. Multinomial logistic regression and interaction for Latinx Adolescent depressive trajectories

Note. OR = Odds ratio, CI = 95% Confidence interval, MDD-PGS = Major Depressive Disorder Polygenic Risk Score. Bolded values represent statistically significant findings.

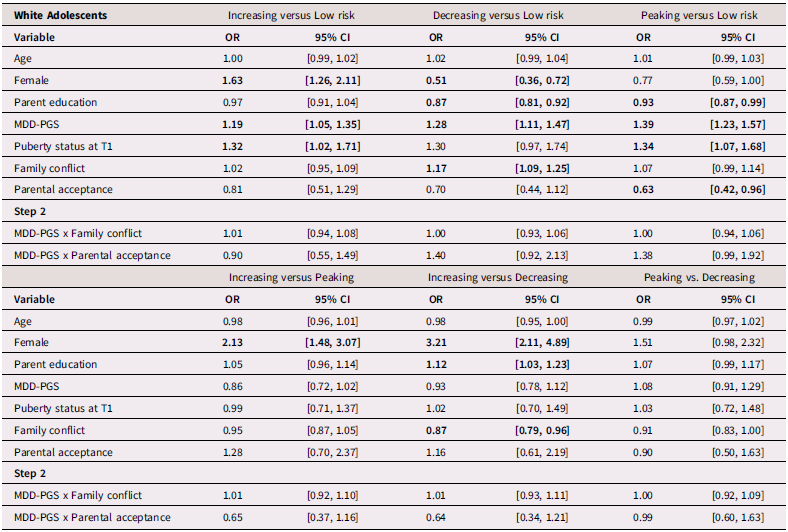

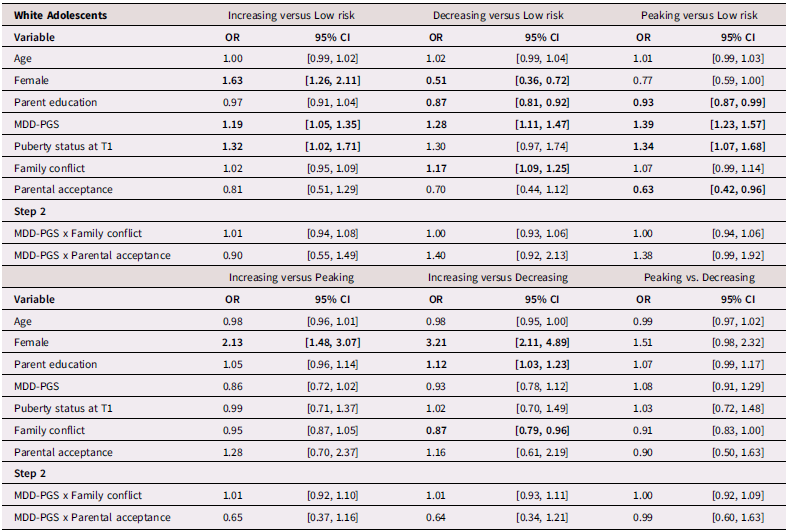

White adolescents

Table 5 presents results from multinomial logistic regressions for White adolescents. Among White adolescents, higher MDD-PGS was associated with greater odds of being in the increasing versus the low-risk trajectory, greater odds of being in the decreasing trajectory versus the low-risk trajectory, and greater odds of being in the peaking vs low-risk trajectory. Higher family conflict was associated with greater odds of being in the decreasing versus the low-risk trajectory and greater odds of being in the decreasing trajectory versus the increasing trajectory. Higher adolescent-perceived parental acceptance was associated with lower odds of being in the peaking versus the low-risk trajectory.

Table 5. Multinominal logistic regression for White Adolescent depressive trajectories

Note. OR = Odds ratio, CI = 95% Confidence Interval, MDD-PGS = Major Depressive Disorder Polygenic Risk Score. Bolded values represent statistically significant findings.

GxE interaction effects between MDD-PGS and family processes

There was no evidence of interaction effect between family conflict and MDD-PGS, or between parental acceptance and MDD-PGS in predicting trajectories of depressive symptoms, across Black, Latinx, and White youth.

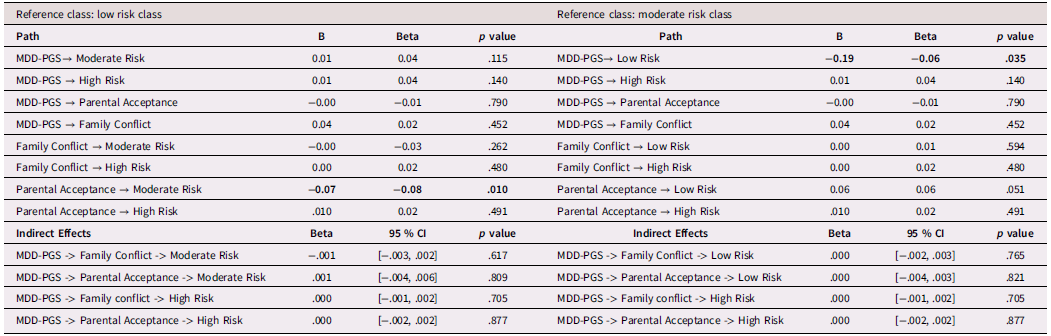

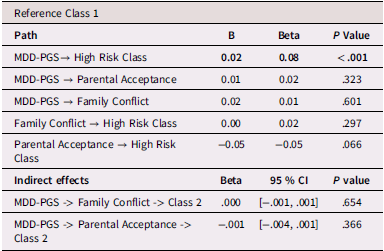

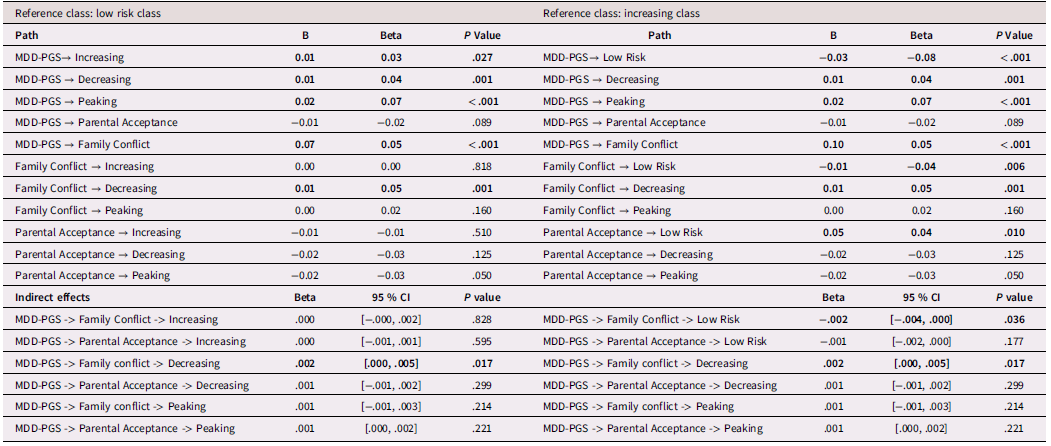

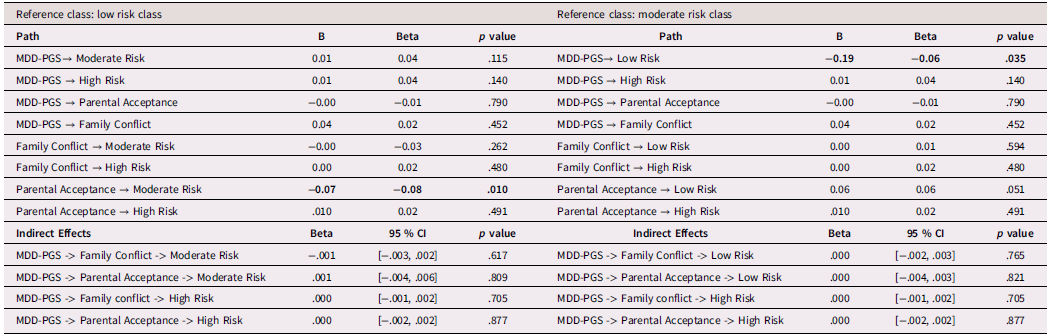

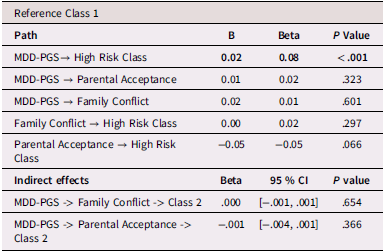

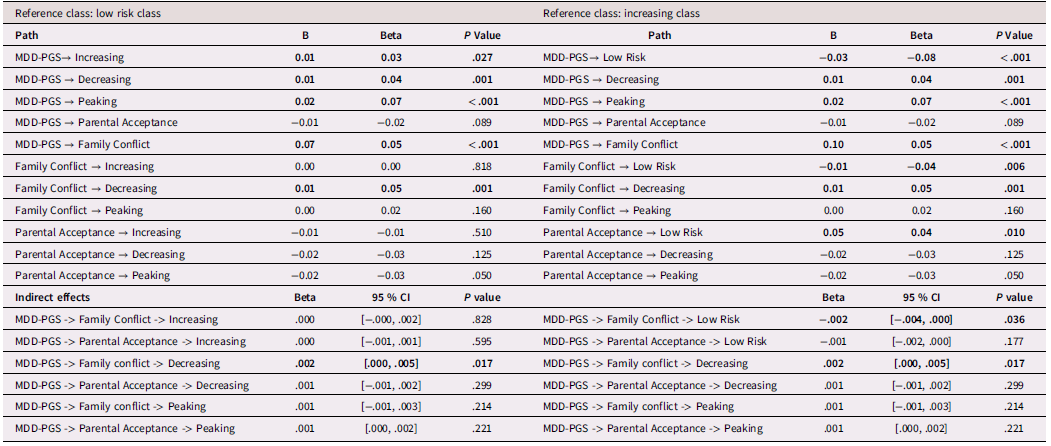

Family processes as mediating mechanisms linking MDD-PGS and trajectories of depressive symptoms (rGE)

Results for mediation models are presented Tables 6, 7, and 8 for Black, Latinx, and White youth, respectively. Among Black and Latinx/a adolescents, MDD-PGS was not associated with adolescent perceived parental acceptance nor family conflict. No significant indirect effects emerged between MDD-PGS and trajectories of depressive symptoms through parental acceptance or family conflict. Among White adolescents, MDD-PGS was associated with greater family conflict at Time 1, but MDD-PGS was not associated with adolescent perceived parental acceptance. Indirect effects reveled that higher family conflict partially mediated the associations between MDD-PGS and the decreasing trajectory, when compared to the low-risk trajectory. Specifically, higher MDD-PGS was associated with greater family conflict, which in turn was associated with greater odds of being in the decreasing trajectory. Family conflict also mediated the association between MDD-PGS and the increasing trajectory compared to the low-risk trajectory, such that MDD-PGS predicted greater family conflict, which in turn predicted greater odds of being in the low-risk trajectory. There was no significant indirect effect of MDD-PGS on trajectories of depressive symptoms through parental acceptance.

Table 6. Black Adolescents, rGE interplay in multinomial logistic regression for MDD-PGS and family variables

Note. OR = Odds ratio, CI = 95% Confidence Interval, MDD-PGS = Major Depressive Disorder Polygenic Risk Score. Parental education, Adolescent sex, Adolescent age, Adolescent puberty status at T1 controlled for in analyses. Bolded values represent statistically significant findings.

Table 7. Latinx Adolescents, rGE interplay in multinomial logistic regression for MDD-PGS and family variables

Note. MDD-PGS = Major Depressive Disorder Polygenic Risk Score. Parental education, Adolescent sex, Adolescent age, Adolescent puberty status at T1 controlled for in analyses. Bolded values represent statistically significant findings.

Table 8. White Adolescents, rGE interplay in multinomial logistic regression for MDD-PGS and family variables

Note. MDD-PGS = Major Depressive Disorder Polygenic Risk Score, Parental education, Adolescent sex, Adolescent age, Adolescent puberty status at T1 controlled for in analyses. Bolded values represent statistically significant findings.

Discussion

Past research demonstrates that depressive trajectories among adolescents are heterogeneous across Black, Latinx, and White youth and that these trajectories may be genetically influenced (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024; Grimes et al., Reference Grimes, Adams, Thng, Edmonson-Stait, Lu, McIntosh, Cullen, Larsson, Whalley and Kwong2024). In the current study, greater MDD-PGS were associated with greater intercept-levels and higher-risk depressive symptom trajectories across Black, Latinx, and White youth. Variations emerged in the effects of family conflict and parental acceptance on depressive trajectories between racial/ethnic groups. These differences warrant further investigation, as these variations may be attributed to differences in power between racial/ethnic groups and/or differing pathways of risk. Lower levels of adolescent-perceived parental acceptance were associated with higher-intercept levels and higher-risk depressive trajectories compared to the low-risk trajectory among Latinx and White adolescents. Among Black youth, higher levels of adolescent-perceived parental acceptance were associated with greater likelihood of being in the high-risk versus moderate-risk group and the low-risk versus moderate-risk group. Higher levels of family conflict predicted greater intercept-levels of depressive symptoms across youth, but only predicted higher-risk trajectories among White youth. Evidence for gene–environment mediation emerged between MDD-PGS and family conflict among White youth, through small, but significant, indirect effects. Our findings revealed utility of MDD-PGS calculated from a large and ancestrally diverse GWAS in predicting intercept-levels of depressive symptoms across Black, Latinx, and White youth.

Depressive symptom trajectories

Overall, our findings revealed varying patterns of trajectories across Black, Latinx, and White adolescents. Across these groups, there were classes characterized by high-risk and low-risk trajectories. Similar to findings from Elam and colleagues (Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024), a majority of youth in each racial/ethnic group were in low-risk trajectories (> 80%) with low-intercept levels of depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with past research on depressive trajectories among adolescents, which demonstrates significant heterogeneity in trajectories across youth with a majority belonging to low-risk trajectories (Kwong et al., Reference Kwong, López-López, Hammerton, Manley, Timpson, Leckie and Pearson2019; Musliner et al., Reference Musliner, Munk-Olsen, Eaton and Zandi2016; Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Clark, Van, Collinson and Baune2017). Some differences in class prevalences emerged between trajectories uncovered in the current study and those identified by Elam and colleagues (Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024), but overall, the same class patterns emerged. These differences may have been attributed to our use of ABCD data release 5.0, which contains more data for T4. Differences between Black, Latinx, and White youth in patterns and prevalences of latent class trajectories may be attributed to the smaller sample sizes of the Black and Latinx subsamples which may lead to a lower representation of heterogeneity in trajectories.

Polygenic risk for MDD as a predictor of adolescent depressive trajectories

Consistent with our hypotheses, our findings revealed that greater MDD-PGS increased odds of membership in higher-risk trajectories across Black, Latinx, and White youth. MDD-PGS did not predict differences between higher-risk groups across Black and White youth. Across youth, MDD-PGS predicted greater intercept levels of depressive symptoms. Consistent with past research, we did not find MDD-PGS to predict slope-level changes in depressive symptoms among Black and Latinx youth (Bakken et al., Reference Bakken, Parker, Hannigan, Hagen, Parekh, Shadrin, Jaholkowski, Frei, Birkenæs, Hindley, Hegemann, Corfield, Tesli, Havdahl and Andreassen2025; Nelemans et al., Reference Nelemans, Boks, Lin, Oldehinkel, van Lier, Branje and Meeus2021). However, we found MDD-PGS to predict increases in depressive symptoms and acceleration in these increases among White youth. This may be attributed to the larger sample of White youth in our study compared to Nelemans and colleagues (Reference Nelemans, Boks, Lin, Oldehinkel, van Lier, Branje and Meeus2021) and the older age of participants compared to the Nelemans and colleagues (Reference Nelemans, Boks, Lin, Oldehinkel, van Lier, Branje and Meeus2021) and Bakken and colleagues (Reference Bakken, Parker, Hannigan, Hagen, Parekh, Shadrin, Jaholkowski, Frei, Birkenæs, Hindley, Hegemann, Corfield, Tesli, Havdahl and Andreassen2025) study. Our findings demonstrate that MDD-PGS may have utility in identifying youth potentially facing more adverse depressive trajectories for early prevention and intervention efforts (Halldorsdottir et al., Reference Halldorsdottir, Piechaczek, Soares de Matos, Czamara, Pehl, Wagenbuechler, Feldmann, Quickenstedt-Reinhardt, Allgaier, Freisleder, Greimel, Kvist, Lahti, Räikkönen, Rex-Haffner, Arnarson, Craighead, Schulte-Körne and Binder2019). The use of large multi-ancestral GWAS allows for better predictive utility of MDD-PGS among Black/African and Latinx ancestry participants (Docherty et al., Reference Docherty, Moscati, Dick, Savage, Salvatore, Cooke, Aliev, Moore, Edwards, Riley, Adkins, Peterson, Webb, Bacanu and Kendler2018; Kanjira et al., Reference Kanjira, Adams, Jiang, Tian, Lewis, Kuchenbaecker and McIntosh2025; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019; Miao et al., Reference Miao, Guo, Song, Zhao, Hou and Lu2023; Tsuo et al., Reference Tsuo, Shi, Ge, Mandla, Hou, Ding, Pasaniuc, Wang and Martin2025; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kanai, Tan, Kamariza, Tsuo, Yuan, Zhou, Okada, Huang, Turley, Atkinson and Martin2023). Compared to findings from Elam and colleagues (Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024) and Grimes and colleagues (Reference Grimes, Adams, Thng, Edmonson-Stait, Lu, McIntosh, Cullen, Larsson, Whalley and Kwong2024) which found insignificant results for MDD-PGS on depressive trajectories among Black and Latinx youth in the ABCD study, our significant effects demonstrate the importance of utilizing PRS-CSx and larger and more diverse GWAS to improve the utility of MDD-PGS in diverse-ancestry youth. Our findings expand upon past research which found MDD-PGS to predict higher-risk trajectories in European-ancestry adolescents by demonstrating polygenic utility in predicting higher-risk trajectories among Black and Latinx adolescents (Bakken et al., Reference Bakken, Parker, Hannigan, Hagen, Parekh, Shadrin, Jaholkowski, Frei, Birkenæs, Hindley, Hegemann, Corfield, Tesli, Havdahl and Andreassen2025; Kwong et al., Reference Kwong, López-López, Hammerton, Manley, Timpson, Leckie and Pearson2019; Nelemans et al., Reference Nelemans, Boks, Lin, Oldehinkel, van Lier, Branje and Meeus2021).

Family processes and adolescent depressive trajectories

In Black, Latinx, and White youth, lower adolescent perceived parental acceptance was associated with increased odds of being in higher-risk depressive trajectories when compared to low-risk trajectories. Parental acceptance predicted greater likelihood of being in the low-risk versus high-risk class for Latinx youth, greater likelihood of being in the low-risk versus moderate-risk class for Black youth, and greater likelihood of being in the peaking class versus low-risk class for White youth. Parental acceptance also predicted lower intercept-levels of depressive symptoms among Latinx and White youth. These findings are consistent with past literature, and suggest that for Black, Latinx, and White youth, promoting adolescent-perceived parental acceptance and positive parenting behaviors may prevent the development of depressive symptoms (García et al., Reference García, Manongdo and Ozechowski2014; Li & Meier, Reference Li and Meier2017; Washington et al., Reference Washington, Rose, Coard, Patton, Young, Giles and Nolen2017). Interestingly, higher adolescent-perceived parental acceptance predicted greater likelihood of being in the high-risk class versus moderate-risk class for Black adolescents. It may be that Black youth with heightened depressive symptoms may elicit more parentally accepting behaviors from their caregivers, as prior research has found parents to display more positive and fewer aggressive parenting behaviors after youth experiences of negative emotionality (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Sheeber, Dudgeon and Allen2012). Alternatively, given the smaller samples of Black youth in higher-risk classes, these findings should be interpreted with some caution. Among Black adolescents, less-involved vigilant parenting, racial discrimination experiences, and internalized racism have been associated with higher-risk depressive trajectories (Reck et al., Reference Reck, Seaton, Oshri and Kogan2024). In addition to parental support, past research demonstrates that uplifting schools (e.g., psychosocial and behavioral skills training), community resources (e.g., extra-curricular involvement), and culturally salient factors (e.g., racial/ethnic identity) could reduce depressive symptoms among youth in Black and Latinx communities (Hull et al., Reference Hull, Kilbourne, Reece and Husaini2008; Malone et al., Reference Malone, Wycoff and Turner2022; Wantchekon & Umaña-Taylor, Reference Wantchekon and Umaña-Taylor2021). Broadly, these findings suggest that improving adolescent-perceptions of parental acceptance may be a meaningful way to reduce depressive symptoms among adolescents. However, unique experiences of racial/ethnic minority adolescents warrant further investigation into culturally-salient sources of stress and support which underlie depressive trajectories. Promotion of positive parenting behaviors that improve the parent–child relationship in addition to improving adolescent perceptions of their caregiver could reduce depressive symptoms across Black, Latinx, and White youth.

Consistent with our hypotheses, greater family conflict was associated with increased odds of being in higher-risk versus low-risk classes among White youth. Across youth, family conflict at T1 was associated with greater intercept-levels of depressive symptoms. However, family conflict was not associated with depressive trajectories in growth mixture models among Black and Latinx youth. White youth with greater family conflict at T1 were more likely to be part of the decreasing class, with heightened baseline levels of depressive symptoms and a negative slope, versus the low-risk or increasing class. These findings are consistent with past research on family systems models and demonstrate that family conflict within the home is associated with greater depressive symptoms across youth (Bowen, Reference Bowen1993; Fosco & Lydon-Staley, Reference Fosco and Lydon-Staley2020). Family conflict may predict increased odds of membership in the decreasing versus increasing class due to measurement of family conflict at T1 and the decreasing class being characterized by the highest levels depressive symptoms at T1, indicating that family conflict is most highly correlated with concurrent levels of adolescent depressive symptoms. Family conflict has been found to be dynamic in adolescence, and has bidirectional associations with adolescent depressive symptoms, highlighting how longitudinal estimates of family-level variables may better predict changes in adolescent depressive symptoms (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Mason, Chmelka, Herrenkohl, Kim, Patton, Hemphill, Toumbourou and Catalano2016; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Liu, Li, Hu, Hong, Li, Teng, Huang and Wang2025). Prior longitudinal research has found family conflict to predict faster rates of increases for adolescents’ depressive symptoms of anhedonia, weight change, and fatigue, indicating subclusters of depressive symptoms may follow differing patterns of development (Kourous & Garber, Reference Kouros and Garber2014). Moreover, the smaller samples of higher-risk Latinx and Black classes may have limited ability to detect significant effects in the growth mixture models. Past research has found family conflict to be influential in Black youths’ development of depressive symptoms, but particularly in terms of inter-parental conflict and exposure to violence within the family (Washington et al., Reference Washington, Rose, Coard, Patton, Young, Giles and Nolen2017). Similarly, family conflict, which may stem from intergenerational acculturative differences between Latinx youth and parents, has been found to predict increases in depressive symptoms among Latinx adolescents (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Gerdes and Kapke2018; Lorenzo-Blanco & Unger, Reference Lorenzo-Blanco and Unger2015). Other stressors may be more pertinent to the development of depressive symptoms for Black and Latinx youth in the United States including racial/ethnic discrimination, neighborhood safety, structural racism, bicultural stressors, and financial-related stressors (Benner et al., Reference Benner, Wang, Shen, Boyle, Polk and Cheng2018; Martínez-Vega et al., Reference Martínez-Vega, Maduforo, Renzaho, Alaazi, Dordunoo, Tunde-Byass, Unachukwu, Atilola, Boatswain-Kyte, Maina, Hamilton-Hinch, Massaquoi, Salami and Salami2024; Mendoza et al., Reference Mendoza, Woo Baidal, Fernández and Flores2024).

Gene–environment interaction in adolescent depressive trajectories

No significant interactions were found for Black, Latinx, and White youth between MDD-PGS and family-level variables (i.e., parental acceptance, family conflict) on depressive symptoms. Past GxE findings for depressive symptoms is mixed, as much of the prior significant GxE interactions for depressive symptoms found via candidate gene studies have failed to replicate (Border et al., Reference Border, Johnson, Evans, Smolen, Berley, Sullivan and Keller2019; Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Assche, Andlauer, Choi, Luykx, Schulte and Lu2021). PGS, in their current state, may not be optimal to investigate gene–environment interactions (Domingue et al., Reference Domingue, Trejo, Armstrong-Carter and Tucker-Drob2020). Construction of PGS pools data across diverse samples with varying environments and birth cohorts. This can lead to a preferential inclusion of genetic variants that display consistent effects across varying environment contexts (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Davies, Hemani and Smith2020). Similarly, studies with greater power may be necessary to detect significant GxE effects (Plomin et al., Reference Plomin, Gidziela, Malanchini and Stumm2022). Nelemans and colleagues (Reference Nelemans, Boks, Lin, Oldehinkel, van Lier, Branje and Meeus2021) found parental criticism to exacerbate the effect of MDD-PGS on depressive outcomes among Dutch adolescents (Nelemans et al., Reference Nelemans, Boks, Lin, Oldehinkel, van Lier, Branje and Meeus2021). Although parental acceptance and parental criticism are related to each other, parental criticism and rejection have been found to predict emotional instability in adolescence above and beyond the effects of parental acceptance (Mendo-Lázaro et al., Reference Mendo-Lázaro, León-del-Barco, Polo-del-Río, Yuste-Tosina and López-Ramos2019). Similarly, MDD-PGS has been found to exacerbate the effects of childhood abuse on depressive outcomes among older European-ancestry adult males (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Zadrozny, Seifer and Belger2024). However, past studies in European-ancestry adults did not find interactive effects between MDD-PGS and childhood trauma or stressful life events on depressive outcomes (Mullins et al., Reference Mullins, Power, Fisher, Hanscombe, Euesden, Iniesta, Levinson, Weissman, Potash, Shi, Uher, Cohen-Woods, Rivera, Jones, Jones, Craddock, Owen, Korszun, Craig and Lewis2016; Peyrot et al., Reference Peyrot, Van der Auwera, Milaneschi, Dolan, Madden, Sullivan, Strohmaier, Ripke, Rietschel, Nivard, Mullins, Montgomery, Henders, Heat, Fisher, Dunn, Byrne, Air, Wray and Penninx2018). Past research has found evidence of interactions between polygenic risk for epigenetic aging and adverse life events on higher-risk depressive trajectories that are consistent with the diathesis stress model (Monroe & Simons, Reference Monroe and Simons1991) among Black and White, but not Latinx youth in the ABCD Sample (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Su, Kutzner and Trevino2024). Future research should broaden conceptualizations of family processes that may influence adolescent depressive outcomes to better capture gene–environment interplay.

Gene–environment correlation and mediation in adolescent depressive trajectories

Our findings revealed that MDD-PGS was associated with greater family conflict among White youth, and family conflict partially mediated effects between genetic risk and higher-risk depressive trajectories, albeit small indirect effects. Parental genetic risk was not controlled for in models, thus these findings may be confounded by unmeasured parental genetic effects and environmental variables. This association may be explained by various mechanisms of rGE such that we may be capturing parental genetic risk on family conflict outcomes (Passive rGE) or that adolescents with greater MDD-PGS may be evoking more family conflict within the home (where parents may be already genetically predisposed to depressive symptoms) (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Lemery-Chalfant and Chassin2023). Our findings replicate those of Su and colleagues (Reference Su, Kuo, Bucholz, Edenberg, Kramer, Schuckit and Dick2018) which found a significant gene–environment mediation between MDD-PGS and lower parental knowledge. These findings are consistent with past research findings on associations between depression-based polygenic risk scores and experiences of stressful life events among European-ancestry participants (Feurer et al., Reference Feurer, McGeary, Brick, Knopik, Carper, Palmer and Gibb2022). Improving family communication and functioning may be a meaningful way to reduce depressive symptoms in White youth with greater genetic risk for MDD. However, genetic risk was not associated with family conflict nor parental acceptance among Black and Latinx youth. These findings are likely partially attributed to limitations in power due to the smaller sample sizes of Black and Latinx youth and measurement of genetic risk in Black and Latinx youth, highlighting the need for more robust and racially/ethnically diverse GWAS studies and longitudinal studies to better capture genetic risk for depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority populations (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019). Moreover, Black and Latinx families may face other stressors including minority-related stress (e.g., racial/ethnic discrimination, bicultural stress) and financial-related stressors which may impact the family environment and parenting behaviors more so than genetic risk (Kazmierski et al., Reference Kazmierski, Borelli and Rao2023; Piña-Watson et al., Reference Piña-Watson, Llamas and Stevens2015; Smith & Mazure, Reference Smith and Mazure2021). Further research is necessary to explore whether these racial/ethnic differences are meaningful or due to limitations in measurement.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several notable strengths. First, we utilized data from the ABCD study, a large, longitudinal, and racially/ethnically diverse sample of adolescents, to better understand how MDD-PGS, family conflict, and parental acceptance predict trajectories of depressive symptoms for Black, Latinx, and White youth. Examining how genetic risk for mental health disorders may influence adolescent depressive symptoms highlights the potential to integrate PGS into prevention science, once more accurate PGS across racial/ethnic groups are developed. The creation of PGS with a large multi-ancestral GWAS and state-of-the-science methods (PRS-CSx), leverages ancestral information from multiple populations to create more effective PGS across populations. Moreover, by examining gene–environment interplay, our work contributes to the literature by exploring how family-level factors moderate genetic risk or serve as mechanisms through which genetic risk manifests. Additionally, our use of growth mixture modeling capitalizes on the strengths of the large ABCD dataset to understand heterogeneity in trajectories of depressive symptoms.

However, this project also has limitations that should be considered when interpreting findings. PGS are imperfect estimates of genetic risk, as MDD-PGS estimation is confounded by variables such as familial genetic predisposition (Wray et al., Reference Wray, Lin, Austin, McGrath, Hickie, Murray and Visscher2021). While the discovery GWAS for MDD-PGS included participants from diverse ancestral backgrounds, individuals of non-EA still represented a smaller proportion of the overall sample. As a result, the SNP effect estimates remain disproportionately influenced by European-ancestry data, which may limit the accuracy and validity of the PGS in Black and Latinx youth. Additionally, even when ancestry-matched LD reference panels are used, PRS-CSx does not fully correct for structural biases in the discovery data, such as uncorrected population stratification, confounding of familial, genetic, and environmental effects, and assortative mating, which may further contribute to reduced predictive validity across youth (Young, Reference Young2024). While this is an ongoing problem among studies utilizing PGS, the predictive validity of these scores have been improving with the presence of larger and more diverse GWAS (Ma & Zhou, Reference Ma and Zhou2021). Moreover, while growth mixture modeling allows for the detection of distinct trajectories, it is a data-driven approach that can limit the sample sizes of subsequent classes. This, in turn, may hinder our ability to detect statistically significant genetic or family-level effects on depressive trajectories, particularly among Black and Latinx youth in higher-risk trajectories with smaller class sizes. Furthermore, the reliability estimates for adolescent depressive symptoms and family conflict variables were in the acceptable, rather than high reliability range, necessitating better assessment of family conflict and parental acceptance across Black, Latinx and White adolescents. Finally, we relied on caregiver reports to assess adolescent depressive symptoms across time points, which may be subject to reporter bias and caregivers’ limited knowledge of their adolescent’s socioemotional status.

Future directions

Our findings highlight the need for more expansive GWAS efforts and additional consideration of how to estimate genetic risk in racially and ethnically heterogeneous minoritized populations. In order to better parse youth genetic effects on depressive trajectories, utilizing familial genetic data (i.e., sibling and parental genotypes) would allow for better estimation of direct genetic effects from environmentally confounded associations. Future research should utilize sibling- or parent-data and tools such as snppar to estimate parental genetic effects and control for parental genetic effects to examine main genetic effects and gene–environment interplay (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Duchene, Pope and Holt2021). Future research would benefit from incorporating multi-informant reports to assess adolescent depressive symptoms more comprehensively. Given the dynamic nature of family processes, future studies should utilize longitudinal estimates of family conflict and parental acceptance to better understand the dynamic nature between adolescent depressive trajectories and family processes. Finally, future studies should replicate these findings using larger samples, particularly among racially/ethnically minoritized groups, and follow participants further into later adolescence to better understand depressive trajectories across adolescence.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings demonstrated varying trajectories of depressive symptoms across Black, Latinx, and White youth. Our findings revealed heterogeneous patterns in the associations between family conflict and parental acceptance and depressive trajectories across racial/ethnic groups. Generally, greater family conflict and lower adolescent-perceived parental acceptance were associated with greater intercept-levels of depressive symptoms and higher-risk depressive trajectories, indicating that reducing family conflict and improving parental acceptance may be important targets of intervention for at-risk youth in Black, Latinx, and White families. Differences in findings emerged across Black, Latinx, and White youth, demonstrating the need for examination of salient sources of support and stress within-racial/ethnic groups. PGS for adult-MDD show utility in predicting depressive trajectories among Black, Latinx, and White youth and could be helpful in prevention and intervention efforts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579425101028.

Data availability statement

The data used in this study are publicly available through the NIMH Data Archive (NDA) as part of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. The ABCD data used in this report came from ABCD Release 5.1.

Acknowledgements

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children age 9-10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD Study® is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041048, U01DA050989, U01DA051016, U01DA041022, U01DA051018, U01DA051037, U01DA050987, U01DA041174, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041028, U01DA041134, U01DA050988, U01DA051039, U01DA041156, U01DA041025, U01DA041120, U01DA051038, U01DA041148, U01DA041093, U01DA041089, U24DA041123, U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in the analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators. The ABCD data repository grows and changes over time. The ABCD data used in this report came from NIMH Data Archive Release 5.1.

Pre-registration statement

Pre-registered: Yes.

Active link: https://osf.io/2xye3.

Date stamped: March 28, 2025. updated Analytic code added on November 20th, 2025.

Deviation: No major deviations reported in the manuscript. All methods and analyses followed the preregistered plan.

Funding statement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5R01AA031281-03 (PI: Su). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Availability of data

All data are available through the NIH Brain Development Cohorts Archive (NDA) upon NIH approval: https://www.nbdc-datahub.org/

Availability of code

Analytical code used in this manuscript are available in the OSF preregistration, output files available from the corresponding author upon request.

Availability of methods/materials

Methods and materials are detailed within the manuscript. Preregistration materials are available on OSF.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

AI statement

No generative AI tools were used for manuscript writing, data analysis, or interpretation. All text. analytic decisions, interpretations, and conclusions were made solely by the authors.