Entrapment – ‘being dragged into a conflict over an ally’s interest that one does not share or shares only partially’ – is part of an unescapable alliance dilemma.Footnote 1 States distance themselves from their allies, risking abandonment, or draw too close, exposing themselves to entrapment.Footnote 2 However, over the last decade, the view that entrapment represents an over-inflated danger has gained increasing traction. Scholars argue that it is ‘difficult to point out … clear cases’; that, when it comes to whether entrapment causes war, the likely conclusion is ‘no, or at very least not very often’; and that its logic is ‘unconvincing’.Footnote 3 These are hard times for entrapment.

Nevertheless, entrapment’s demise is exaggerated. Entrapment comes in different types. The scarcity of one kind does not mean others are not present. This paper examines one such type, labelled classic entrapment. Classic entrapment is a strategy involving a weaker party (‘the protégé’) confronting an existential security threat. In order to elicit intervention by a stronger state (‘the protector’), the protégé deliberately places itself in a position of likely defeat and manipulates domestic audience costs. Basically, the protégé needs to make a stand but realises that it cannot afford to do so. Unable to rely on its own resources to resist a stronger enemy, it seeks to muster those of other powerful states. By playing off protector and challenger against each other, it achieves better results than its own capabilities allow. Hence, entrapment represents a strategy of division, similar to divide and conquer, except being pursued from a position of weakness.Footnote 4 As the saying went, whenever Imperial China was facing superior strength, it would ‘use barbarians to check barbarians’.Footnote 5

Two questions drive this paper. Why and how do protégés pursue classic entrapment? And what are the conditions for classic entrapment to succeed? Hypotheses are provided by the 1853 prelude to the Crimean War. Russia presented the Ottoman Empire with a diktat: agree to de facto protectorate or face dismemberment.Footnote 6 Instead of accepting its fate, the Porte drew in Great Britain.Footnote 7 The result was the largest great-power war in the century between the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War, resulting in 750,000 battle deaths. Russia was defeated and kept in check for a generation.Footnote 8 The Porte went on to survive until 1918.Footnote 9

This endeavour adds value to alliance theorising in several ways. First, it provides a novel entrapment typology and outlines the strategy of classic entrapment. Existing entrapment scholarship focuses exclusively on the protector, leaving understudied the entrapper’s perspective. Accordingly, it privileges the ways protectors seek to escape entrapment over the ways in which protégés seek to overcome their resistance to intervention. Second, the paper reclaims entrapment for theorising. If sceptics are right in pronouncing entrapment a boogeyman, alliances and partnerships come risk-free: nearly always assets, hardly ever liabilities. A state can/should conclude as many as possible. But if entrapment is a realistic concern, then undertaking foreign commitments poses a non-negligible danger to would-be protectors. Consequently, this research carries far-reaching implications for ongoing debates on the usefulness of alliances; the merits of restraint versus deep-engagement grand strategies; and the risk of imperial overstretch.Footnote 10 Third, although scholars imply Great Britain’s entrapment in the Crimean War, no rigorous test of whether entrapment took place has ever been conducted.Footnote 11 Current research considers the Ottoman perspective only fleetingly, relies solely on secondary sources, or fails to specify why and how entrapment came about. Conversely, this paper examines meticulously the Porte’s position; it benefits from untapped primary sources, namely the first-ever translation from Ottoman of Turkgeldi’s chronicle of Grand Council debates throughout the crisis and explains the case through a fleshed-out discussion of the classic entrapment strategy in terms of goals and tactics.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. The first section outlines classic entrapment’s strategic logic: who practises it, under what circumstances, in what manner, and for what reasons. The second section examines the objections raised against entrapment and rebuts them. The third section addresses classic entrapment tactics. The fourth section showcases how the Porte translated classic entrapment into practice in 1853.Footnote 12 The conclusion evaluates the findings’ implications and the present relevance of classic entrapment.

Strategic logic

Definition and typology

Entrapment designates any process through which an alliance or partnership member leads another member to intervene militarily over issues that it would not be fighting over otherwise. Although scholars regard entrapment as a unitary phenomenon, it is useful to distinguish three types, labelled here reverse entrapment, ‘entanglement/emboldenment’, and classic entrapment.

In reverse entrapment, the protector drags the protégé into conflict. Reverse entrapment occurs because the protégé seeks to curry favour with its protector, gaining or increasing territorial, economic, or military rewards; or because, should it stay out, it fears the protector’s retribution through sanctions, attack, or abandonment. Meanwhile, the protector seeks logistical support, to enhance its legitimacy, or to test the protégé’s loyalty, without being vitally dependent on its contribution for fighting. Examples are the Warsaw Pact’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 or NATO’s Kosovo intervention.Footnote 13

The type that, for want of a better word, one may call entanglement/emboldenment concerns alliance logic. On the one hand, the protector must intervene because abandoning the protégé hurts its own credibility as a guarantor, or because alliances create common interests, institutions, and identities that it cannot walk away from.Footnote 14 On the other hand, the belief that the protector has to rescue it to preserve the alliance emboldens the protégé. Consequently, the protégé treats the alliance as a blank cheque: if in trouble, the protector will bail it out. This is moral hazard, since there is no penalty for the protégé taking risks and passing along the costs to the protector. With moral hazard, ‘the causal-core of the concept [consists] in the presence of incentives to take risk where there is protection (or the expectation of protection) against its consequences’.Footnote 15

Classic entrapment is a protégé strategy aiming to drag the protector into a conflict serving primarily the protégé’s interests. This makes classic entrapment distinct from the other types. In classic entrapment, unlike in reverse entrapment, the protégé drags the protector into conflict. In classic entrapment, without the protector’s intervention, the protégé is condemned to defeat; while, in reverse entrapment, the protector can do without the protégé’s support. Moreover, in classic entrapment, the protégé does not seek the protector’s good graces but instead to manipulateit to adopt the protégé’s interests as its own, even at the risk of upsetting it.Footnote 16

Distinguishing entanglement/emboldenment from classic entrapment comes down to purposefulness. Entanglement/emboldenment is the result of misperception and moral hazard. Under the mistaken impression that the protector intends to support it, the protégé engages in risky action, which creates, in a self-fulfilling prophecy, the very situation requiring the protector’s intervention. Hence, the protégé has no elaborate strategy to drag the protector into the fray beyond getting itself in trouble, since it assumes that the latter will intervene of its own accord anyway. Alternatively, classic entrapment is purposeful, and hence strategic: the protégé knows the protector is unwilling to intervene and deliberately coaxes it into doing so. There is no misperception or moral hazard at work. Accordingly, in order to tell the two types apart, the question to ask is whether the protégé assumes that the protector will automatically defend it. If it does, this points to entanglement/emboldenment; if, however, the protégé anticipates the absence or the refusal of protection and seeks to overcome it, this indicates classic entrapment.Footnote 17

Identification

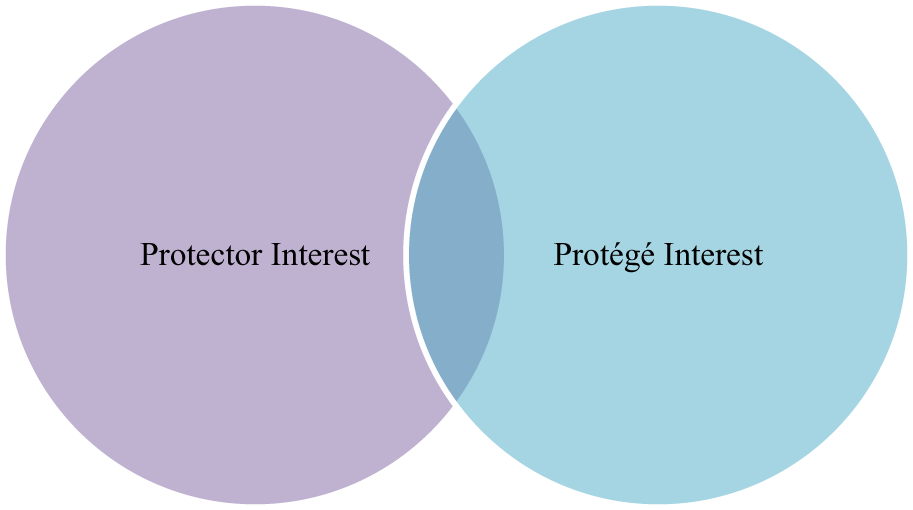

Classic entrapment has a high bar to clear to be properly identified. If the protector does not back the protégé, it is not entrapped. But even if it backs the protégé, this may not be entrapment, provided the intervention serves its own interest from the get-go. Instead, this is regular intervention. So, under which circumstances does classic entrapment occur? The way out is to ask whether the protector would have fought but for the efforts of the protégé to drag it in. The protector may have an interest in the preservation of certain assets the protégé controls but would baulk at crossing this threshold. Classic entrapment occurs whenever the protégé drags the protector past this red line, by manoeuvring it to fight on behalf of other interests that the protégé considers existential, such as the preservation or recovery of territory or status, but which the protector deems secondary. This means that, at the beginning of the crisis, the protector would not have intervened for the stakes on the table, although it might have provided diplomatic aid, economic assistance, or weapons. This situation is captured in Figure 1. The protector would have fought to defend the protégé’s interests captured by the overlap area, but not the rest.

Figure 1. Protector and protege interests before the crisis.

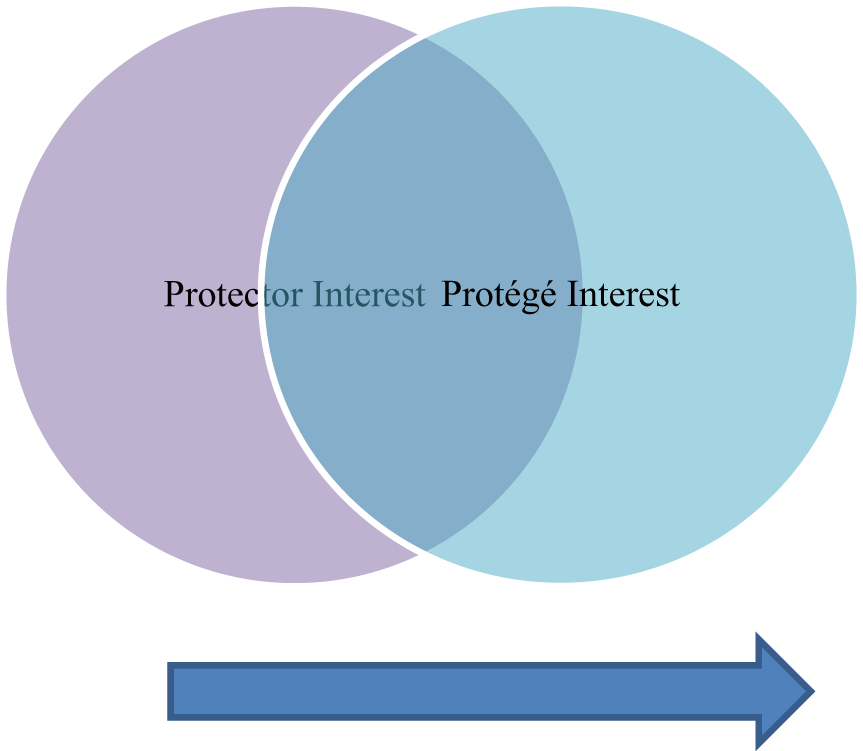

Nevertheless, over the duration of the crisis, the protector is brought by the protégé to the point of defending interests it would have not championed beforehand. The overlap area, justifying intervention, expands to encompass more of the protégé’s interests, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Protector and protege interests during the crisis.

Therefore, classic entrapment works because the protégé manoeuvres the protector into a position where the latter’s interests, whether security, reputation, or/and domestic politics, are endangered. So, they become tied to protecting the protégé’s interests, which were previously not viewed as priorities. Thus, classic entrapment is not about considering separately the ultimate decision to intervene, since there is no such thing as a purely selfless intervention. Given that the protector cannot have zero interests in the final decision, classic entrapment refers to a commitment process developing over time, through which the protector, who originally wanted to sit the conflict out, is gradually coaxed to intervene. This decision is not made in one go but comes as the last move in a sequence, as the consequence of previous decisions to increase support to the protégé gradually.

Entrapment and its critics

The case against entrapment comes down to three charges: historical record scarcity; wary protectors acting to prevent entrapment; and disincentives for protégés to entrap protectors. A brief discussion follows of each objection, including a rebuttal.

Objection 1

First, critics point out a damning empirical flaw: the dearth of convincing cases. As Brooks, Ikenberry, and Wohlforth write, it is ‘nearly impossible to find a clear case of entrapment actually occurring’. Meanwhile, Kim thanks Schweller for ‘pointing out the difficulty in finding cases of entrapment’.Footnote 18 The observation concerning scarcity has become so commonplace that even scholars supporting entrapment advocate lowering the bar, since ‘rational states are not expected to fight wars against their national interests’, and any such instances would be ‘relatively rare’. Insisting on such impossibly high standards would ‘define away the phenomenon of interest’.Footnote 19 Much of this scepticism comes from the fact that discussions of entrapment rely exclusively on Austria-Hungary’s alleged entrapment of Germany at the outbreak of the First World War. Heatedly debated for 80 years, this case has been subjected to a number of reinterpretations over time. Recent research challenges the long-held belief that Germany expected a rapid, offence-dominant war and casts into significant doubt whether Berlin was entrapped by its ally’s apparent recklessness.Footnote 20 However, with the First World War taken off the table, there are hardly any empirical referents of entrapment left.

Rebuttal

At least one genuine classic entrapment example other than World War I is necessary to meet the empirical objection. This paper proposes the 1853 crisis.

Relying on a single case study limits generalising ability. However, the format compensates through a trade-off with causality. In an in-depth single case study, the reader knows ‘almost everything’ about the outcome’s causes, getting a nearly ‘complete’ explanation of the causal mechanism involved.Footnote 21 Given the formidable challenges of identifying entrapment and of confirming actual instances, it is preferable to conduct a fine-grained examination before any further testing.

Provided it is deviant, i.e. highlighting ‘a new variable demanding to be heard’ and/or a previously ignored hypothesis or causal mechanism, a single case may lead to reassessing currently dominant theoretical views.Footnote 22 Recent scholarship expects entrapment to be highly unlikely. But it has looked for entrapment exclusively in formal alliances and in contexts where the protector enjoys a determinant bargaining advantage, neglecting the question of whether it shows up in informal arrangements and in conditions of indirect dependence, as the case under scrutiny indicates. Accordingly, the hypothesis that entrapment is unlikely/improbable is considerably weakened, given that its scope condition is much larger than previously thought.

Objection 2

Critics believe classic entrapment unlikely because, in a formal alliance, protectors should be highly sensitive to it. Therefore, they are likely to take steps to prevent it by insisting on escape clauses. These are restrictive provisions of the casus foederis, i.e. the treaty conditions under which a party goes to war to defend its ally. By carefully writing provisions, protectors enable themselves to sit out military confrontations in which they have no desire to intervene, on the grounds that the circumstances faced are not covered by the treaty.Footnote 23 A recent example is Russia declining to intervene in autumn 2020 to help Armenia against Azerbaijan, on the grounds that the Collective Security Treaty only applied to Armenian territory, which was not under attack, and not to Nagorno-Karabakh, where fighting was taking place.Footnote 24 Doubtless, the protector has to fight if the treaty’s terms are breached, for instance, by an enemy’s unprovoked attack on the protégé’s recognised territory.Footnote 25 But if the protégé acts recklessly, or initiates hostilities, the protector has no such legal obligation. Knowing this, the protégé hesitates to resort to entrapment.

Rebuttal

For argument’s sake, one may assume critics right in that protectors are able to restrict the casus foederis in formal alliances, written down in a treaty, made public, and subject to legislature ratification.Footnote 26 But, by the same token, protectors do not enjoy a similar degree of control in security partnerships, which are tacit, off the record, low-profile, and identifiable by the protector providing military assistance in terms of equipment, funding, and training.Footnote 27 With no written treaty, there is no explicit casus foederis. Therefore, it is impossible to establish with any certainty where the casus foederis applies, and where it does not. At first glance, the ambiguity in how to meet commitments in informal arrangements benefits the protector. Partnerships bypass ratification, help the protector claim plausible deniability for supporting disreputable protégés (the Contras; the Khmer Rouge), and, most importantly, do not require the protector to defend the protégé should it come under attack. The protector finds it easier to disavow promises not spelled outright.Footnote 28 Nevertheless, the overlooked downside of the partnerships is that there is also no identifiable cut-off point where the protector’s support must end. The protector may have a red line separating its interests from those of the protégé where it means to stop its support. But this demarcation line is blurry. Hence, the protégé finds it easier in an informal arrangement to trick the protector into crossing this threshold. At the same time, it is harder for the protector to go back once it has stepped beyond.

The protégé relies on gradualism to entice the protector to expand its initial commitment, resulting in a creeping commitment that becomes stronger over time. In informal settings, the protector is more likely to fail to notice this process is taking place, becoming aware of classic entrapment only at the point where it is already so far engaged that it is too late for it to back out. The Crimean War may represent the ‘most eloquent example’ of such developing commitment.Footnote 29 Britain intervened in January 1854 with no treaty compelling it to support militarily the Porte. A formal alliance was concluded only after fighting started in March 1854, and a security guarantee treaty had to wait the end of hostilities in April 1856.Footnote 30

Objection 3

In classic entrapment, the weaker party constrains the stronger. However, as Bismarck observed, every successful alliance must have a horse and a rider – a stronger party stirring the weaker.Footnote 31 In setting up alliance terms, and in subsequent bargaining, the protector is the rider. Without its help, the protégé may collapse. The reverse is not true: the protégé’s contribution to the protector’s security is not of life-or-death importance. Consequently, the protégé has the greater interest in maintaining the alliance in order to survive and, to do so, must defer to the protector. Meanwhile, the protector is able to keep the protégé guessing whether it would extend support, because it can afford to cut the protégé loose without damaging its own chances of survival. Fear of abandonment keeps the protégé in line. This is all the more likely in tight alliances, in which there is wide divergence of interests, institutions, and values between rivals, and which should be otherwise-ideal scenarios for entrapment. Yet, in such contexts, the protégé has minimal incentives to dealign or realign because the opposing faction would welcome it with blows, not open arms. Therefore, protégé’s moves to entrap the protector represent a bluff.Footnote 32

Rebuttal

The rider also depends on the horse. In certain circumstances, the protégé enjoys a bargaining advantage over the protector. Snyder distinguishes between direct dependence, which is about how much one side needs the other’s military support, and indirect dependence, which is about the ‘degree of strategic interest that the parties have in defending each other’. Direct and indirect dependence can reinforce each other, as in the case of a great power’s peer ally, which provides vital military support and whose survival is as important as one’s own. An illustration is the USA, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union in the Second World War. However, direct and indirect dependence also can work at cross-purposes. The protector provides essential help, allowing the protégé to survive; but the latter holds sufficient strategic weight to affect the power equation between the protector and its enemies.Footnote 33 In such instances, the protégé’s realignment is welcomed by the other side. Therefore, indirect dependence may help address the objection that alliances have a restraining effect as pacta de contrahendo (constraining pacts). The assumption is that the protector tethers the loose-cannon protégé, because the latter knows that it cannot escape defeat without the protector’s intervention.Footnote 34 Nevertheless, if the protégé is too important to abandon, tethering becomes problematic.

The protégé’s allegiance has a substantial impact on the outcome of the strategic contest between powerful states under two scenarios. First, the protégé controls sizable latent capabilities, comprising raw materials, energy resources, wealth, technology, or population, which if added to the capabilities of one side confers it the upper hand.Footnote 35 Second, the protégé’s location or its territory’s layout is strategically valuable. Controlling geopolitical ‘chokepoints’ – straits, capes, islands, mountain ranges, passes, or rivers enabling access, allowing a limited number of defenders to resist a larger number of attackers or removing obstacles on the attacker’s path – confers decisive military advantage.Footnote 36

Indirect dependence is possible even under unipolarity or bipolarity, although, under these configurations, the protégé’s defection should not affect the overall distribution of power.Footnote 37 Nevertheless, while others need the pole more than it needs them, this does not mean that even a superpower is self-sufficient and does not need anyone.Footnote 38 Needing a protégé is particularly likely in cases in which it controls unique geopolitical, economic, demographic, or technological assets.Footnote 39 Present US primacy does not depend just on the resources Washington owns relative to Beijing and Moscow but also on its ability to withhold from them the combined resources of Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East. This is dependent on the USA preserving key protégés in each region. While losing a unique assets protégé may not bring the USA down, it may leave it substantially worse off. Therefore, the protector may come to have a disproportionate interest in particular protégés, because preserving them is the only way to prevent adversaries from gaining advantages. Since the protégé knows this, it enjoys leverage: ‘differences in strategic interest help to explain why the most powerful state in an alliance often has little leverage over its partners: when the stronger state’s strategic interest is well known, it cannot credibly threaten defection or realignment’.Footnote 40

Tactics

The classic entrapment strategy may be attempted when only one of the informal arrangement and indirect dependence elements are present, but it is less likely to work. If the protégé does not enjoy indirect dependence relative to the protector, the latter can repudiate the informal arrangement with few adverse costs. Meanwhile, in a formal alliance, indirect dependence constrains the protector to succour the protégé under the alliance terms, but these rule out saving a reckless ally. Provided the treaty’s letter is not breached, there is no compulsion for the protector to intervene in a conflict caused by the protégé, which confirms the previous finding that formal alliances seldom entrap.Footnote 41 That is why classic entrapment works best in contexts in which both conditions are present. The protector cannot afford to abandon a protégé controlling valuable assets; and its commitment is so ill-defined that it has no clear cut-off point. Accordingly, the protégé carries out the strategy of classic entrapment through a combination of two tactics: (a) chain-ganging; and (b) audience costs manipulation.

Chain-ganging

Chain-ganging involves the protégé purposefully engaging in actions carrying a high risk of military defeat.Footnote 42 The reasoning is that if the protector does not send help, the protégé has to defect or be annihilated. The protégé has to get to the edge of defeat, because victory or a draw is an excuse for the protector to decline intervention, on the grounds that the protégé can handle things on its own. Just resorting to verbal threats or provocations is likely to be dismissed as a bluff. As Schelling illustrates: ‘if two climbers are tied together, and one wants to intimidate the other by falling over the edge, there has to be some uncertainty or unanticipated irrationality or it will not work … Any attempt to intimidate or to deter the other climber depends on the threat of slipping or stumbling … one can credibly threaten to fall off accidentally by standing near the brink.’Footnote 43 If defeat looms, the protégé may have lost control already, and the only way to avoid its fall is the protector’s intervention. When ‘one member of the chain gang stumbles off the precipice, the other must follow’.Footnote 44 Pressure on the protector increases continually, because if it waits too long, the opportunity window for rescuing the protégé may close.

Nonetheless, chain-ganging cannot account fully for classic entrapment. Scholars thought it did, because in contexts of relative equality between rival alliances or between parties in an alliance, any defection hands victory to the other side. Therefore, states cannot allow strong allies to fall.Footnote 45 However, this logic becomes problematic if there is wide strength disparity, as between protector and protégé, because the protégé’s dealignment fails to affect decisively the power distribution between blocs. Hence, there is no reason why the protector should not be able to abandon the protégé. The weaker the protégé is relative to the protector, the more it should expect the latter to hesitate to rescue it; and the more it should seek to overcome the protector’s resistance to intervene.

Audience costs manipulation

States expand their commitments when, due to initial underestimation or unforeseen developments, they discover that more resources are needed to salvage them, out of domestic politics calculations, or due to prestige/ reputation.Footnote 46 Being aware of these mechanisms, protégés steer protectors towards positions where the need arises to do more to shore up their commitment or lose it, and where it becomes unfeasible for them to back off. While chain-ganging generates the need for the protector to step up the commitment to preserve it, manipulating its domestic audience costs cuts off its retreat. Basically, the protector does not change its mind of its own volition from non-intervention to intervention. Instead, it is the protégé’s actions that force its hand.

Leaders are concerned about punishment by relevant domestic audiences for issuing a foreign threat and then backing down. Audience costs can lock governments into supporting commitments they would not otherwise fight for. Since promises and threats are two sides of the same coin, whenever the protector promises the protégé support, it simultaneously issues a threat against actors that might harm it. Therefore, audience costs may form without the protector being aware of incurring them. When a promise/threat is implied, expectations of support may emerge, and, if not honoured, provide grounds for punishment.Footnote 47 This is not concept stretching, since definitions of audience costs do not actually mention whether the commitment made by the state in a crisis should be explicit or implicit, stipulating only that the state should back down or be perceived to by domestic audiences.Footnote 48

Audience costs work because conceding after committing ‘gives domestic political opponents the opportunity to deplore the international loss of credibility, face, and honor’.Footnote 49 Accordingly, the protégé’s trap depends on having the protector’s reputation/prestige placed on the line. The protector can either back up the protégé against its original intentions or disown it, sacrificing its reputation and suffering domestic penalties.Footnote 50

Scholars assume that audience costs advantage democracies in international crises, because accountability to voters helps democratic leaders tie their own hands – it is harder for them to back off without repercussions. Furthermore, this process is transparent to the opponent in the crisis, constraining it to offer concessions.Footnote 51 However, other actors may also be responsible for tying the protector’s hands. The protégé may lobby rival ministers or the political opposition. It may also influence the protector’s media by planting/framing news presenting the government’s decision not to intervene as failure to follow through.Footnote 52 Lastly, the protégé may escalate the dispute gradually.

Audience costs increase over time during a crisis. They are lowest at the outbreak and mount as it progresses.Footnote 53 In this case, it does not make sense for the protégé to plunge into risky action with audience costs at their minimum. Instead of being swept along in one homogeneous growth curve, the protégé escalates gradually, allowing audience costs to pile up. With each further step, the protégé asks the protector to provide increased support, daring it to abandon it or suffer domestic punishment. The more steps are taken, the harder it becomes for the protector to cut off support without being severely punished, because it has assented already to providing support in previous instances.

Thus, decision-makers do not just blunder into incurring unwanted commitments. They may also do so piecemeal: ‘one typical way in which people find themselves stuck with unwanted decisions is through a gradual, stepwise increase in commitment such that the final action, which would have been rejected if faced head-on, becomes a matter of “now it’s too late to get out of it”’. Blackmail and ‘foot-in-the-door’ sales techniques rely on the same principle. This gradual manipulation involves initial seemingly easy and cheap steps, but which accumulate, are difficult to reverse without losing face, and lead to progressively bigger demands.Footnote 54 Gradual escalation is not unlike salami tactics – eroding steadily an opponent’s commitment through successive minor infractions. Here, the protégé induces the protector to cross its own threshold, by breaking the big issue into smaller ones pressed independently of each other. The goal is not to induce the other side to do what one wants them to do (intervene) in one go, but to get them to do what one wants them to do next (expand the commitment), while bringing them closer to the desired outcome.Footnote 55

These points are important to meet the objection that the protector may intervene due to regular domestic pressure: the protector made a commitment, and now it has either to honour it or suffer punishment. Nonetheless, if this were the case, there is no reason why the protector could not escape audience costs by decoupling. The protector could claim it had been ‘misunderstood’ and had not actually promised to help the protégé, given the commitment’s ambiguity. Hence, its non-intervention would not constitute infringement.Footnote 56 However, the protégé’s manipulative efforts complicate decoupling by restricting the protector’s ability to back down.

The onset of the Crimean War illustrates the protégé’s use of classic entrapment and demonstrates how the strategy is logical and effective under the theorised conditions.

Classic entrapment in practice

The case study begins by surveying the British commitment to the Porte before the crisis. It then examines the Ottoman strategic calculations and tactics. Lastly, it considers alternative explanations.

The crisis

In February 1853, a Russian envoy, Alexander Menshikov, arrived in Istanbul. Under French threats, the Porte had conceded advantages to Catholics in managing the Christian holy places in Jerusalem. Russia insisted on similar privileges for its Orthodox brethren. But Menshikov had a hidden agenda – he demanded a sened (convention) affirming Russia’s right to act as protector of the Orthodox religion in the empire, whose practitioners stood at 12 million people, a third of the population. Essentially, Russia was claiming an intervention right similar to the Roosevelt corollary to the Monroe doctrine. If the Porte refused, Menshikov was to terminate diplomatic relations, signalling future attack.Footnote 57

The Porte offered concessions over the holy places, but not the sened. In May, a frustrated Menshikov left in a huff. In June, Russia occupied the Principalities (Moldova and Wallachia, present-day Romania), holding them hostage for as long as the Porte did not accept the sened. Britain advised waiting on great power mediation, while bringing up a naval squadron to Besika Bay at the entrance to the Dardanelles. Great power negotiations produced in July a compromise – the Vienna Note. The Note mentioned the sultan remaining faithful to ‘previous treaties relative to the protection of the Christian religion’. The Porte correctly interpreted this as confirmation of a Russian right of intervention to protect the Orthodox, who, moreover, were not referred to as the sultan’s subjects. Since accepting the Note would have been the equivalent of ‘drinking poison and dying’, the Porte demanded modifications.Footnote 58 Britain’s leaders were unhappy, but, once the Russian interpretation of the Note as a renewed claim for a protectorate leaked, they discovered they could not cut off support because of domestic public outcry. After Russia predictably rejected the modifications, Britain announced it could no longer endorse the Note.Footnote 59 In September, the Porte declared war to recover the Principalities and requested that the British navy advance to Istanbul to protect the city. One day after the British squadron passed the Dardanelles, the Porte initiated fighting on the Danube.

With its navy in the Bosphorus, Britain’s foremost concern became avoiding accidental confrontation. Accordingly, it warned Russia not to use the Black Sea navy to attack Ottoman territory.Footnote 60 The Porte then opened a second front in the Caucasus. The easiest way to supply the Ottoman forces there was by ship, yet the risks for an escorted transport flotilla were considerable. Britain advised against the plan, and when the Ottomans insisted, lobbied that the Porte withhold the best part of its navy, the line-of-battle ships, hoping a weaker force would not be as threatening. However, this made the Ottoman frigates and corvettes an easy target for Russia’s superior firepower. At Sinope, in November, Russia sank the entire flotilla save for one vessel, with 4,000 Ottoman sailors out of 4,200 tasting ‘the sherbet of martyrdom’.Footnote 61 Meanwhile, in the Caucasus, the Ottoman armies were routed by a Russian force three times smaller.Footnote 62 The Porte lost no time in asking Britain for military aid. In January, Britain sailed into the Black Sea, which Russia interpreted as an act of war.Footnote 63

Observable implications

Is Britain’s intervention classic entrapment? Britain could have intervened because of intrinsic interests/concerns – regular intervention. Another possibility is the Porte took British support for granted and acted recklessly, banking on being rescued. Hence, British intervention represents entanglement/emboldenment. Lastly, the Porte might have being willing to fight to the bitter end for its independence and territorial integrity; British intervention is an unintentional by-product of nationalism. Table 1 sums up the implications for classic entrapment versus those of alternative explanations.

Table 1. Observable implications for competing explanations of Britain’s intervention.

For classic entrapment, the evidence should show that Britain’s commitment to the Porte was informal; and that the Porte held indirect dependence over London. Left to its own devices, Britain should have sat the conflict out. The Porte should not have relied on automatic British support, instead anticipating and seeking to overcome British resistance to intervention. Lastly, there should be evidence of classic entrapment tactics. The Porte should have purposefully placed itself in a position of likely defeat and sought to manipulate British public opinion. Conversely, regular intervention should show that Britain’s decision to intervene was taken independently of Ottoman actions. Entanglement/emboldenment would stand confirmed if the evidence shows the Porte being subject to misperception and moral hazard. The nationalist outburst thesis requires evidence the Porte ignored great-power support in deciding to fight.

Britain’s commitment

If the Ottoman Empire were to collapse, great-power war over its remains was likely. Although it was preferable to allow the Porte to go on, the continental great powers did nothing to prop it up. Expecting it would eventually crumble, they wanted to seize whatever they could before anyone else. Whenever they could get away with it, Russia, Austria, and France bullied the Porte into granting concessions over various provinces they coveted. Initially, Britain too prognosticated impending collapse.Footnote 64 But this stance changed in the 1830s to one in which London thought the Porte could reform and resume being ‘a respectable power’.Footnote 65

This was the result of the Great Game, Britain’s competition against Russia for mastery of Asia. Russia expanded in Central Asia and Persia, reaching Afghanistan’s borders and threatening British India. Accordingly, Britain’s key objective became containing the Russian advance, which led to a global contest from Canada/Alaska to China, and from Afghanistan to the Middle East.Footnote 66 In the Great Game, the Porte emerged as the owner of ‘the first strategic position in the world’, the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, controlling the only exit from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. The Black Sea, which enjoys warm-water harbours in winter, was essential as the only area allowing the use of Russian warships year-round.Footnote 67 Consequently, the Straits, and, implicitly, the Ottoman capital Istanbul controlling the Bosphorus, represented a ‘chokepoint’ that Britain could not afford to lose. In turn, this conferred the Porte indirect dependence vis-à-vis London.

Britain was alarmed when, after failing to rescue the Porte in a disastrous war against Egypt in 1832, the sultan appealed to Russia, arguing that ‘a drowning man in his despair clings to a snake’. Russia’s price was the Unkiar-Skellesi treaty, which mentioned the exclusion of warships from the Straits during war. Britain suspected this was the first step towards allowing Russia right of passage while denying it to its own navy.Footnote 68 Lord Palmerston, multiple times foreign minister, lamented Britain not having helped the Porte as ‘the most tremendous blunder of the English government’.Footnote 69 To undermine Unkiar-Skellesi, he stated that ‘it was … of the utmost importance to the interests of this country … that the Turkish Empire should be maintained in its integrity and independence’.Footnote 70

It was this move that set mischief afoot.Footnote 71 The British informal commitment never spelled outright where support for the Porte was supposed to end, yet implied that such a threshold was present. Hence, there was no identifiable moment of decision before which there was no British commitment to intervene on the Porte’s behalf, and after which such a commitment existed: ‘the worst of all possible kinds of commitments was created – a commitment that was felt to be real to … deterring parties (Britain …) and the protected client (Turkey) but that was nonspecific and inexplicit’.Footnote 72 This created both the expectation among the British public that support had been promised, in line with the argument on decision-makers inadvertently contracting audience costs; and the opportunity for the Porte to lure Britain into expanding this commitment.Footnote 73

The formulation ‘integrity and independence’ presumably meant a commitment to preserving the Porte’s control over all its provinces, implying that if a great power attempted to seize one, or interfered with Ottoman independence, Britain would have taken the field. However, Britain meant something far more circumscribed: the maintenance of Ottoman control over the Straits. From the mid-1830s on, defending the Straits was proclaimed in parliament, affirmed by the monarch in public speeches, and implied in communications to Ottoman officials. The British ambassador was authorised to call in the navy if the Porte requested it, and a squadron was stationed in Malta for fast deployment. On several occasions, it was dispatched to Besika Bay.Footnote 74

This might suggest regular intervention, because by aiding the Porte, Britain sought to protect its own interests. As Palmerston remarked: ‘we maintain the integrity and independence of Turkey not for the love & affection of the Turks, but because we prefer the existing state of things there to any other state of things … and because the interest political and commercial of England & Europe would be dangerously injured by the destruction of that integrity and independence’.Footnote 75

However, with the exception of the Straits, Britain ‘was not ready to fight for a part of the Ottoman Empire’.Footnote 76 Lord Clarendon, Britain’s foreign minister in 1853, explained: ‘We wish to maintain the “integrity” of Turkey, but the word is somewhat vague, and the interpretation given to it not very easy.’ In truth, ‘call it by what name we may … integrity, independence … fear of Russia and desire to keep her out of Constantinople is at the bottom of all’.Footnote 77 When the Porte lost control successively over Serbia, Greece, Egypt, Syria, and Algeria, London did not intervene to help it regain or retain them. Likewise, Ottoman independence was interfered with regularly, most recently by France over the holy places, without Britain stepping in. The British prime minister in 1853, Lord Aberdeen, thought Palmerston’s ‘integrity and independence’ formula was ‘absurd’.Footnote 78 Accordingly, there was no obligation whatsoever for Britain to help once Menshikov’s terms were rejected.Footnote 79 Britain intervening to prevent a Russian advance to Istanbul would have constituted regular intervention. However, British intervention to help the Porte get rid of Russia’s sened demand and/or to recover the Principalities represented textbook classic entrapment. Britain would have been made to fight for interests it did not share.

This danger was evident to Aberdeen: ‘the Turks … see clearly the advantages of their situation. Step by step they have drawn us into a position in which we are more or less committed to their support. It would be absurd to suppose that, with the hopes of active assistance from England … they should not be desirous of engaging in a conflict with their formidable neighbor.’ Queen Victoria agreed: ‘we have taken on ourselves … all the risks of a European war without having bound Turkey to any conditions in respect to provoking it … [the Ottomans] exhibit clearly … a desire for war and to drag us into it’.Footnote 80

Ottoman strategic calculations

Three main Ottoman factions emerged around the time of the crisis. All agreed that a sened could ‘not be allowed’, since ‘in case we met these demands, may Allah forbid it, it will gradually hand over the protection of Greek [Orthodox] subjects to the Russians’.Footnote 81 However, significant differences emerged on how to respond.

The first faction comprised the ulemas (clerics). It supported chancing war, come what may, since Allah would have ensured victory irrespective of material considerations. The Porte should have fought alone or concluded an alliance with a proper Muslim state, such as Persia. The goals of the war should have been extensive: recovering lost Ottoman provinces and advancing to Moscow.Footnote 82

The second faction consisted of ‘nationalists’, led by the minister of defence (Seraskier), Mehmed Ali. They accepted Western-style reforms as necessary but wanted to borrow only military technology and tactics, without a wholesale shake-up of the Empire. Mehmed Ali was for the Porte pursuing war alone, which made the ulemas natural allies. This way, the Porte would have avoided British demands to implement comprehensive reforms and would have maintained Ottoman traditions. The Seraskier’s intention was for the Porte to ‘settle alone’ with Russia after having shown the flag. As Grand Vizier, he pursued private talks with Menshikov without informing the great powers of Russia’s demands. He also indicated that if Russia rolled back the sened, the Porte would bargain. He certainly did not want the war he got, in which the Porte was allied to Britain and had to concede to its requests.Footnote 83 Neither the ulemas nor the nationalists had any interest in entrapping Britain.

Classic entrapment is attributable to a third faction: the realists. They comprised the reformists, led by the foreign minister Mustafa Reshid Pasha, who served six times as Grand Vizier.Footnote 84 Having built his career on advocating the overhaul of Ottoman society on the Western model, and relying heavily on British political backing with the sultan, Reshid believed that the Porte’s only chance was to secure great-power support, foremost Britain’s.Footnote 85 Suggestively, his solution – which, short of a smoking gun, is as clear an admission of classic entrapment as one is likely to get – was to ‘lure in’ the great powers and to ‘take them to war’.Footnote 86

After intense factional debate, two options emerged. The Porte could go to war and then negotiate with Russia separately, as the nationalists wanted. This would have been more honourable, because the Porte would not have had to rely on great-power help, but, instead, on its own might ‘out of loyalty and patriotism’. Conversely, the Porte could follow Reshid’s advice and call Britain to the rescue. This meant accepting that if ‘our strength is not enough, there is no other choice but to allow the intermediation and assistance of the great powers and follow a path accordingly’.Footnote 87 The decision came down to military estimates. The Porte could field only 82,000 troops on the Danube, plus around 100,000 irregulars. But Russia could have easily deployed an army of around 300–400,000 men. The Porte simply did not have the numbers. The Grand Council concluded unanimously in July that even if the Porte were ‘strong enough … it could be dangerous to deal with a powerful state like Russia without the assistance of the great powers. Assuming the Russian military only enters the Principalities and does not advance further, expelling it without outside support would be fairly dangerous.’ Therefore, the Grand Council rallied to Reshid’s position: ‘the only way for the Porte to weather out [the crisis] was to gain over the great powers’.Footnote 88

Chain-ganging

At 160,000 regular troops, the Ottoman army was smaller than any of the great powers’, save Prussia’s, and, although surprisingly well equipped – Ottoman French-supplied Minié rifles surpassed the Russian muskets – the soldiers were poorly trained and officered. Training was worse for irregular troops, which made up the bulk of the Caucasus force. The Ottoman officer corps was selected and promoted based on nepotism and bribery, resulting in the infantry and the cavalry having trouble executing even basic manoeuvres. Meanwhile, the navy was half the size of the Russian battlefleet and not as advanced. The Porte had suffered defeat in every single war fought in the century.Footnote 89 These facts were not lost on the Ottoman leaders. Neither the Seraskier nor the chief admiral would commit themselves as to whether the Porte could fight Russia unaided. The latter assessed that the navy could resist Russia in the Black Sea, but, in the same breath, added that he should not be held to these words. The realists pointed out that the Porte was weak militarily and economically, that it depended on great-power support, and that fighting alone put a 600-year-old state’s existence at risk. As they observed, ‘[the Porte] cannot deal with the Russians alone. In this respect, we need these states [Britain and France].’ If fighting alone, ‘in the end, defeat is inevitable’.Footnote 90 This makes the decision to fight Russia a purposeful exercise in inviting defeat: the Porte knew it was going to lose but counted on provoking British intervention to turn things around. Hence, declaring war was chain-ganging, not an act of desperation – choosing between defeat and surrender.

The flotilla’s movements raise suspicions that it had been deliberately set up to fail. The warships were under express orders not to open fire, even if military advantageous. Furthermore, they did not exploit an opportunity to leave Sinope and return to safety in Istanbul.Footnote 91 With the Porte’s navy eviscerated, Britain faced a situation in which only intervention could prevent its defeat. The British had anticipated this scenario. Aberdeen deemed it ‘inevitable’ that ‘the Turks will take good care … to undoubtedly engage the Russians in the presence of the British fleet’. Queen Victoria believed the only reason for the Ottoman expedition was ‘to beard the Russian fleet and to tempt it to come out … which would thus constitute the desired contingency for our combined fleet to check it’.Footnote 92

The Porte’s risky course of action was also not caused by optimistic gambling on the war’s probable outcome. British intervention was far from guaranteed. Since the Porte knew about London’s inclination to sit the conflict out, it could not passively wait to be rescued. Instead, it had to manipulate Britain into intervening.

Audience costs manipulation

The Ottoman ambassador to London, Musurus Bey, regularly lobbied Palmerston throughout the crisis. Palmerston may have been kept away from foreign affairs, but he was still the most popular figure in the shaky Aberdeen coalition.Footnote 93 Palmerston promised support – he never endorsed war but advocated coercing Russia into concessions in his allied newspapers.Footnote 94 Besides, from the 1840s on, the Porte had dedicated an annual subvention to planting favourable articles in European newspapers, including in Britain.Footnote 95 While little scholarship exists on these efforts, there is evidence that the Porte realised Britain’s audience costs: Musurus sent Reshid a large number of British newspaper clippings criticising Russia and supporting the Porte. Historians conject that the perception of a supportive British public opinion emboldened the Porte into adopting an uncompromising stance.Footnote 96

However, Reshid was aware that Britain would have preferred compromise with Russia. If the Porte rejected great-power intercession, and went straight to war, as the ulemas and nationalists wanted, Britain would not have helped beyond protecting the Straits. As Reshid stated, ‘if [the Porte] asks to protect its rights, the great powers will fight together with us. If we demand more than that, they will not intervene.’Footnote 97 He also informed the Grand Council that Britain and France had threatened to withdraw their navies if the Porte pushed too aggressively for war.Footnote 98 Put differently, classic entrapment would not have worked if it was obvious to London that the Porte meant to entrap it.

Gradual escalation proved the best tactic in the Ottoman arsenal. The Porte started by demonstrating its willingness to reach compromise, but without giving away anything substantial. Once Russia rejected the proposed settlement, the Porte escalated while appearing fully justified. At that point, Britain had a choice: either abandon its protégé or underwrite the bellicose move and expand its commitment. Since British public opinion was consistently against abandonment, the Porte got away with escalation and could then further up the ante.

The Porte repeated this tactic no fewer than four times, which pleads against a fortuitous combination of circumstances. It refrained from going to war once the Principalities were occupied; abstained from rejecting outright the Vienna Note; delayed initiating hostilities after declaring war; and scaled down plans for its naval expedition. These apparent conciliatory moves were followed by escalatory steps: demanding modifications to the Note; the war declaration; starting hostilities; opening a second front; and the self-defeating Black Sea expedition. Basically, ‘if the Ottomans had promptly counter-attacked [at the start of the crisis] this action would have tended to define the situation as another in the series of Russo-Turkish wars. Britain … would … have had little reason to intervene. By not attacking and also not agreeing to a solution, the Turks … gave the Western powers an extended opportunity to become more deeply involved in the problem.’Footnote 99

A good example of gradual escalation is the Ottoman response to the Vienna Note. Britain thought the Note was a plausible compromise it could live with, and which Russia would have been willing to take. Russia got a veiled protectorate and the Principalities, while Britain prevented an advance on the Straits. Thus, the Note safeguarded Britain’s interests while sidestepping a clash, which is why it was imperative to secure its acceptance. Clarendon was explicit: ‘I shall write in strong terms to [the British Ambassador in Istanbul] that the Vienna Note must be accepted.’ When warned that the Ottomans would refuse, Clarendon was dismissive: ‘oh, we are to decide for them, you know.’ Britain’s position was clear: the Ottomans should have gone along with the great powers settling the outcome of the crisis over their heads – or face abandonment.Footnote 100

Had the Porte declared straight away the Vienna Note inadmissible and started fighting, relying solely on chain-ganging, London would have washed its hands of the outcome. Reshid, however, accepted the Note, while requesting modifications of the bits that interested Russia the most, without which the whole agreement would have collapsed. This was rejection by another name, an escalatory move.Footnote 101 The British thought so, showing considerable frustration at the Porte torpedoing their painstaking compromise. Clarendon complained of Turkish ‘stupidity’ and ‘obstinacy’, while Aberdeen surmised that the Porte’s ‘suicidal’ conduct ‘can only be explained by a desire that the affair should end in war’.Footnote 102

However, the British decision-makers found out at that point that they could not abandon the Porte. After the Russian ‘violent’ interpretation of the Note leaked, they were caught in a media storm involving even the initially moderate or pro-government outlets such as The Times, The Manchester Guardian, and The Morning Chronicle. The newspapers’ position was that leaving the Porte at the mercy of an aggressive and despotic Russia would have hurt significantly British honour. They assessed the government could not survive. To quote The Morning Herald: ‘[since] the Cabinet are avowedly ready to prostrate British honour and British faith before the ambition of Russia, we venture to promise that the British people will make short work of the Ministers’. One prominent coalition member observed that Britain’s honour was at the stake, and ‘to have held out such encouragement to the Turks … and afterwards to desert them, would be felt as deep disgrace and humiliation by the whole country’.Footnote 103 Consequently, Clarendon begrudgingly admitted: ‘we cannot press the Turks too hard about the Note because public opinion would be against it’.Footnote 104 Hence, instead of abandoning the Porte for seeking modifications, Britain was now going to endorse them.Footnote 105 On cue, the Porte escalated by declaring war, causing Britain to issue the deterrent threat, and eliciting Clarendon to comment that: ‘with reference to public feeling in England, we could not well do less’.Footnote 106 Meanwhile, Aberdeen stated that ‘public opinion will not allow [abandonment of Turkey].’Footnote 107

The Sinope incident also suggests that the Porte sought to provoke Russia to trigger Britain’s deterrent.Footnote 108 Had the clash occurred on the high seas, the flotilla could have been seen as a legitimate target. But, as it purposefully laid anchor in the Sinope harbour, presenting an inviting target, it caused the town, hence Ottoman territory, to come under Russian attack. For Britain, backing down would have been fatal to its reputation. To quote Clarendon, Britain found itself in a ‘ridiculous position’, having advanced to protect Turkey and then having Sinope happen ‘almost within earshot of our sailors’. The government could no longer shirk from intervention because the press erupted into a vitriolic denunciation of the ‘Sinope massacre’. To quote Martin: ‘the tsar, already the incarnate soul of evil, had once more put forth his hand to torture and destroy; the Sultan … was hard pressed in the fight with darkness; England, pledged to his assistance, had stood idly by and watched the massacre of his sailors. Our national honour was trailed in the dust and our Ministers proved treacherous agents of the Tsar.’ Only Palmerston was spared the opprobrium, and his resignation on an unrelated matter sent the public into frenzy. ‘Seldom has public sentiment run so high or menacingly than it did in the month to follow.’Footnote 109 When even the conciliatory The Times remarked that ‘war has begun in earnest … the Emperor of Russia has thrown down the gauntlet to the Maritime Powers’, Britain was trapped into intervention, the very course of action deemed undesirable at the onset of the crisis.Footnote 110

Alternative explanations

The explanation of regular intervention is not on strong ground. Control of the Straits, the one condition that would have triggered British intervention, was never in danger. Russia knew that threatening Istanbul meant war and abstained from any hint of such action. One might argue that potential Ottoman defeat threatened British security interests anyway, but the British decision-makers would not have intervened for the existing stakes, meaning the Principalities and eliminating the sened demand. The Aberdeen cabinet considered war ‘the greatest of all calamities’ and stated in parliament that it did not regard the Principalities’ occupation as a casus belli. After the Ottoman modifications to the Vienna Note, Britain seriously contemplated letting the Porte fend for itself. Clarendon warned Reshid that Turkey would collapse under the weight of war if the Note was not accepted. The cabinet assented: ‘we cannot abet [the Turks] in their obstinacy’.Footnote 111 This signalled Britain’s willingness to allow the Porte’s defeat, something that should have been anathema if any kind of Russo-Turkish war endangered British security.

Invoking British nationalism – hence domestic politics outside of audience costs manipulation – as the reason behind Britain’s intervention is also unwarranted. British sympathy for the Porte was not enough to determine London to offer an alliance before 1854. Meanwhile, Russophobia cannot account for why Britain, had it been spoiling for a fight with Russia, did not take advantage of the perfect pretext of the Principalities’ occupation to start hostilities.

A better case for regular intervention can be built over Sinope and reputation. However, Britain’s reputation being in jeopardy was the result of Ottoman actions. The British navy did not teleport into the Bosphorus. In all previous crises with Russia, Britain had only deployed at the entrance to the Dardanelles, determinedly not going any further so as not to violate existing treaties. The decision to go to Istanbul represented crossing a Rubicon, and this move was necessitated by the Porte’s war declaration. Accordingly, Britain’s decision to intervene was the outcome of a prolonged process of being dragged in gradually by the Porte, as depicted by Figures 1 and 2 above. As far as London was concerned, ‘rarely was war approached more slowly or more hesitantly’.Footnote 112

Entanglement/emboldenment is also problematic. ‘Entanglement occurs only when a state fights to uphold a formal alliance commitment.’Footnote 113 This rules out Britain’s informal commitment to the Porte. Furthermore, had entanglement/emboldenment been present, the Porte should not have expressed any reservations whatsoever on whether Britain was going to rescue it. This would leave unexplained the need for Ottoman gradual escalation, because in entanglement/ emboldenment there is no need for the protégé to sit around and wait, being convinced the protector will automatically intervene. Thus, the protégé should escalate swiftly. However, if the protégé delays the risky action and escalates gradually, this indicates its awareness of the protector’s resistance to intervention and the need to overcome it. Hence, why should have the Porte waited on great-power mediation for months, when it could have declared war in June, counting on automatic British support?

Lastly, evidence supporting an Ottoman nationalist outburst is lacking. The Grand Council ignored routinely the ulemas. One realist even told them to their faces that they did not know any rationale in state affairs other than the Sharia, and that they should not speak about what they did not know.Footnote 114 Meanwhile, the nationalists took advantage of an inebriated sultan to orchestrate Reshid’s dismissal in July and incited in September and December the religious students in Istanbul to riot for unilateral war. But these attempts failed miserably. In July, the British ambassador went ‘bang down to the Padishah and put [Reshid] back in’. In September, the chief rioters were rounded up and exiled to the countryside. In December, Reshid again appealed to Britain, which, through the sultan, coerced the Seraskier to crack down on his own supporters.Footnote 115 This explains why in the war debate the nationalists were self-effacing: their influence after the failed September coup was ebbing. Paradoxically, it was the realists who decided to fight unilaterally. Once Reshid pronounced himself in favour, the Council unanimously voted for war.Footnote 116 It is unlikely that Reshid, who had insisted all throughout the crisis that British support was crucial, was abruptly rallying to the defeated nationalists’ views.Footnote 117 Actually, the war declaration made express mention of the Porte gaining further advantages and solving problems with great-power help.Footnote 118

Conclusion

Scholars discount entrapment wholesale, but several types exist. Entanglement/emboldenment may be rare, but this does not imply that reverse or classic entrapment is scarce. Reverse entrapment, so far understudied, represents the norm in unipolarity.Footnote 119

When it comes to classic entrapment, scholars may not have found it because, to paraphrase Indiana Jones, they have been ‘digging in the wrong place’, neglecting informal arrangements and indirect dependence. Hence, including these factors opens up a universe of potential cases. Classic entrapment may have affected nearly every US major military involvement since 1945. The USA intervened without any prior-sanctioned commitment to defend South Korea (1950), Taiwan (1954), South Vietnam (1965), Kuwait (1990), Bosnia (1995), and Kosovo (1999) and fought decade-long wars to keep weak partners from collapse in Afghanistan (2001 onwards) and Iraq (2003 and 2014 onwards.) Meanwhile, Victorian Britain, which famously had no formal allies, undertook no fewer than 59 wars on behalf of state and non-state protégés in Asia, Africa, Oceania, and the Middle East.Footnote 120 However, currently, these are only potential entrapment instances, and they should be further tested through in-depth case analysis.

Classic entrapment remains highly relevant to present world politics, in which partnerships are pervasive. The USA has informal arrangements with around 30 states from the Middle East to sub-Saharan Africa, and from Eastern Europe to South and Central Asia.Footnote 121 China has a single ally, North Korea, but a multitude of partnerships, including Pakistan, Iran, Cambodia, and African Union countries. Xi Jinping has signalled a preference for security based around ‘partnerships, not alliances’.Footnote 122 Meanwhile, Russia has informal arrangements with Syria, India, Iran, Indonesia, Venezuela, Serbia, and several African countries.Footnote 123 While not all these protégés enjoy indirect dependence relative their protector, some do, because of latent capabilities and/or geopolitical position. The USA may not be obligated to intervene to rescue Taiwan, Singapore, India, Israel, Saudi Arabia, or Ukraine. But abandoning them would confer advantage to competitors such as China, Russia, or Iran. Therefore, the protector’s vulnerability relative to these protégés confers on them the opportunity to manipulate Washington into intervention.

Taiwan is a case in point. Scholars assume that the main danger concerns entanglement/emboldenment: Taipei’s belief in automatic US support would embolden it to take risks.Footnote 124 However, classic entrapment may be the real threat. Currently, there is no cut-off point where the ill-defined US support for Taiwan must end. Presumably, the American red line consists of defending Taiwan and Penghu, but does not extend to the two other islands Taipei claims, Kinmen and Mazu, which have already caused crises in 1954 and 1958. Furthermore, the USA opposes Taiwan proclaiming its independence. Therefore, if Taiwan insists on independence, or defends Kinmen and Mazu, it should find itself on its own. But is the USA realistically able to abandon Taiwan?

As the world’s leading producer of semiconductor chips, essential for computers, smartphones, cars, planes, and weapon systems, Taipei enjoys indirect dependence relative to the USA. Of the chips used by US semiconductor producers, 92 per cent originate in Taiwan, as do 50 per cent of the world’s most advanced chips.Footnote 125 The USA cannot afford to lose Taiwan to China without jeopardising its technological edge. Additionally, East Taiwan’s deep-water harbours confer significant advantage in detecting enemy submarines and keeping one’s own on station. A recent study estimates that controlling Taiwan would increase China’s attack ability against American sea lines of communication ‘by roughly 50%’.Footnote 126 Moreover, abandoning Taipei would confront the USA with audience costs fuelled by the powerful Taiwan lobby. US leaders would stand accused of harming America’s reputation by refusing to stand up to China and being an unreliable protector in the Indo-Pacific. Since the USA is a democratic protector, any threat of abandonment is likely to be undermined by American public opinion, with punishment dealt to decision-makers supporting it. Therefore, Taiwan could borrow a page out of the Porte’s playbook, and combine chain-ganging and audience costs manipulation to drag the US gradually into fighting on its behalf.

In light of these findings, the two sides’ positions in the ongoing debate concerning whether alliances and partnerships are assets or liabilities, and whether the USA should undertake them, appear overstated. Instead, with entrapment an enduring risk, commitments present a state with unavoidable trade-offs between advantages and disadvantages. There is no such thing as a cost-free commitment.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210524000731.

Video Abstract

To view the online video abstract, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210524000731.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to extend his profound gratitude to William Wohlforth, Benjamin Valentino, Richard Ned Lebow, Jon DiCicco, Jack Levy, Joseph Parent, and the participants in the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding invited talk in September 2022, as well as the peer reviewers. This review has also benefited from the able research assistance of Yasemin Altintas and Ece Kartal, and from the amazing expertise of PhD candidate in History Anil Karzek, who translated the original document from Ottoman into English.