1. Introduction

Time-based and technology-based installation art has long been questioned in terms of conservation (see Real Reference Real2001 for a summary), but the documentation and conservation of sound art installation has, however, received much less research attention. A handful of studies on sound art installation include Bressan and Canazza (Reference Bressan and Canazza2014), Lacey (Reference Lacey2016), Stokowy (Reference Stokowy2017), Nakagawa and Kaneko (Reference Nakagawa and Kaneko2017), Vasquez (Reference Vasquez2019), and Fraisse et al. (Reference Fraisse, Giannini, Guastavino and Boutard2022) from historical, sociological and technical perspectives, respectively. In terms of actual documentation practice, Brost (Reference Brost2018) published an extensive framework from a museum studies perspective for sound in time-based media installations, ‘from the artist’s vision for the listener experience of the artwork to its realization in the exhibition space’. She builds notably upon Phillips’s (Reference Phillips2015) distinction between the documentation of the artwork (the identity report) and of a single installation (the iteration report), reminding us that ‘documentation is a primary conservation strategy for time-based media artworks. … Unlike artworks in traditional media, time-based media works only exist when they are installed’ (Brost Reference Brost2018). A telling example is provided by Eppley (Reference Eppley2017), discussing outdoor reinstallation and impact of neighborhood’s modifications for Max Neuhaus’s famous Times Square (1977) piece: ‘one might assess how the new seating arrangement affects acoustic perception, or if its tones need to be “retuned” to a new material density’ (Eppley Reference Eppley2017: 25). Both reports are critical but also intertwined: ‘as the work continues to be installed and installation instructions evolve, the specifics of each installation are recorded in a separate Iteration Report. These in turn inform updates to the Identity Report’ (Brost Reference Brost2018). In Brost’s framework though, the listener experience is scantly described, limited to broad documentation categories, namely ideal listener experience, additional listener experiences and subjective listener experience.

During the project Sound Art Documentation: Spatial Audio and Significant Knowledge (SAD – SASK), we investigated the relation between sound art installations, documentation practice and the sensory experience of a sound artwork. In the first part of the project, we developed a technical description framework for sound art installation in Quebec based on the literature and a review of the artistic practices (Fraisse et al. Reference Fraisse, Giannini, Guastavino and Boutard2022). Based on this framework, we selected two sound art installations (Boutard et al. Reference Boutard, Guastavino, Bernier, Gauthier, Fraisse, Giannini and Champagne2022) for the second part of the project, which focuses on the sensory experience in relation to documentation. The present article discusses the outcomes of this second part, which started with spatial audio recordings of two sound art installations: Estelle Schorpp’s Écosystème(s) (Schorpp Reference Schorpp2019); and Jean-Pierre Gauthier’s Générateur Stochastique (OBORO 2020). McConchie (Reference McConchie2018) proposed to use virtual reality tools for documentation purposes but little has been done for sound art. Virtualisation of sound art has attracted far more interest in dissemination rather that documentation; for example, Sporobole’s (2023) Déjà-Vu platform. The distinction is important as the project consciously does not include a visual immersive rendition but concentrates on spatial audio rendering to investigate sound art installation documentation. As such, the project focuses on the auditory experience as a critical part of the sensory experience while acknowledging its codependency to the other dimensions of the sensory experience in its holistic nature. Bandt (Reference Bandt2006), for example, defined sound installations as ‘a sonic intermedia practice, which blurs the boundaries of the visual and aural and includes the spatial, the temporal and the haptic’. There is thus a strong reduction of the idea of sensory experience proposed in this project for the sake of the research and its positioning within the context of broader documentation frameworks that have focused on other dimensions of the global sensory experience; for example, the classic new media art documentation projects of the 2000s such as V2_’s Capturing Unstable Media (Fauconnier and Frommé Reference Fauconnier and Frommé2004) or DOCAM (Ippolito Reference Ippolito, Depocas, Ippolito and Jones2003). Furthermore, this study aims at questioning the relation between documentation and the sensory experience from a multi-expertise perspective, including sound artists (SA), sound engineers (SE), new media and sound art curators (CU), and new media and sound art conservators (CO).

By confronting various fields of expertise to spatial audio documentation we propose to discuss strategies guiding the sensory experience and its relation to documentation and the literature in these fields. Building on Boutard and Guastavino’s (Reference Boutard and Guastavino2012) notion of significant knowledge – based on the inclusion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge-driven documentation frameworks – we will further discuss the role of spatial audio documentation tools for documentation frameworks.

2. Methodology

2.1. Spatial audio recordings

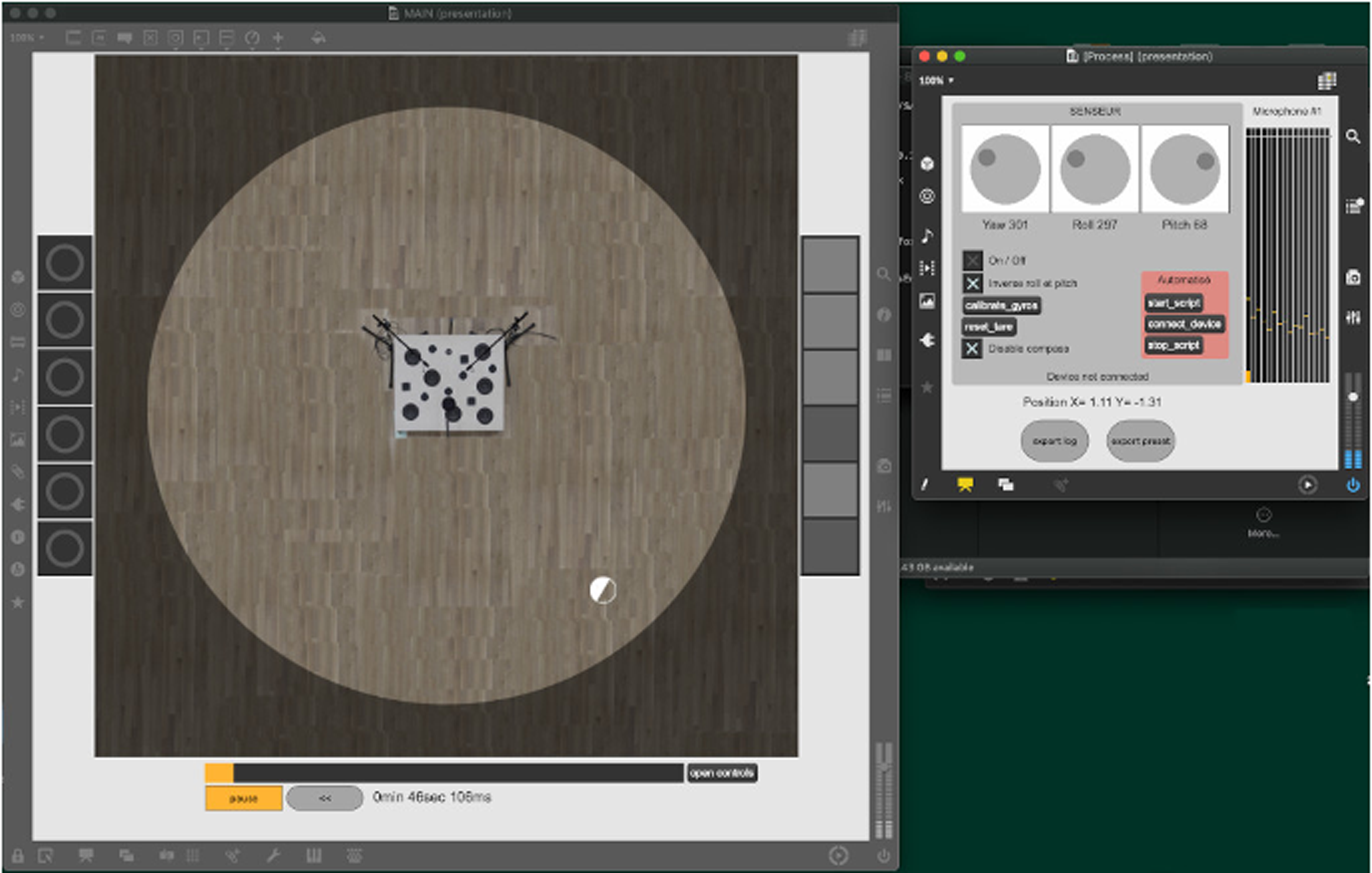

Estelle Schorpp’s (ES) Écosystème(s) was recorded on 12 March 2021 in the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology’s (CIRMMT) MultiMedia Room (MMR) at McGill University in Montréal, where it was installed by the artist for the purpose of this research. Jean-Pierre Gauthier’s (JPG) Générateur stochastique was recorded on 14 June 2021, at gallery Ellephant in Montréal, where it was on exhibition, but outside visiting hours. The spatial audio recordings were conducted using a setup consisting of seven Zylia third-order ambisonics microphones, namely one central microphones (in relation to the installation) surrounded by six microphones equally spaced around a circle with a 2 m radius, all at ear level (1.5 m from the floor) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Recording setup for Estelle Schorpp’s Écosystème(s) in the MMR–McGill University.

The same spatial audio recording setup was used for both installations to evaluate a practical and simple method for documentation (as opposed to tailoring the setup to each installation).

Several recordings were made for each installation with different conditions. For JPG’s work, we recorded several sessions of JPG interacting with the work and one session with a sound artist familiar with the work and also a collaborator of the project. For ES’s work we recorded eight sessions with different room acoustics conditions (the MultiMedia Room has variable acoustics) and in the presence or absence of visitors. These recordings were submitted for review to one project collaborator familiar with the artwork as well as an expert in sound art creation (a different expert for each artwork). They selected a 10-minute recording slice they considered to be the best to represent the work.

2.2. Interactive listening sessions

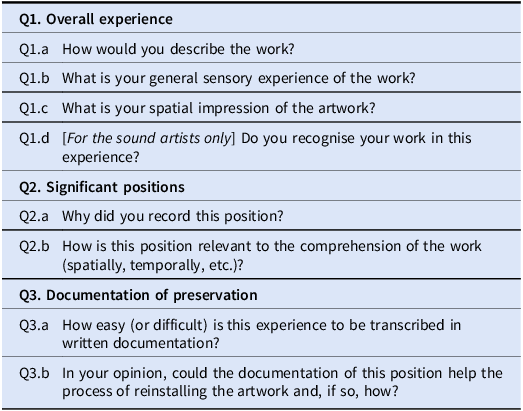

These spatial audio recordings were subsequently used for the next phase of the project, which involved interactive listening sessions and interviews with participants in the Audio-editing Laboratory of CIRMMT. We designed a graphical user interface in Max-MSP allowing participants to interact with the spatial audio recording (Figure 2). It consisted in an aerial view of the installation (based on a picture for ES and a diagram for JPG) though which participants could freely move in space (x and y coordinates) as well as in time. They could record and recall up to six positions (in space and time for each installation). The GUI did not display the position of microphones to participants to avoid influencing their experience of the recording. Although the GUI provided a very limited visual experience, it allowed participants to discuss their position choices during the interviewing phase. Furthermore, it relates to the standard experience of a documentation report that would articulate relations between spatial audio recordings, maps and diagrams.

Figure 2. Graphical user interface used by participants to control their interaction with the 6DoF recording. In this example, it displays and uses the recording of ES’s work.

The interpolation of spatial audio between microphone positions was processed using Zylia MaxMSP objet, 6DoF Higher Order Ambisonics (HOA) Renderer v2.1.0. The output was rendered in binaural using SPARTA’s library v1.5.0. The version of MaxMSP was v8.1.11.

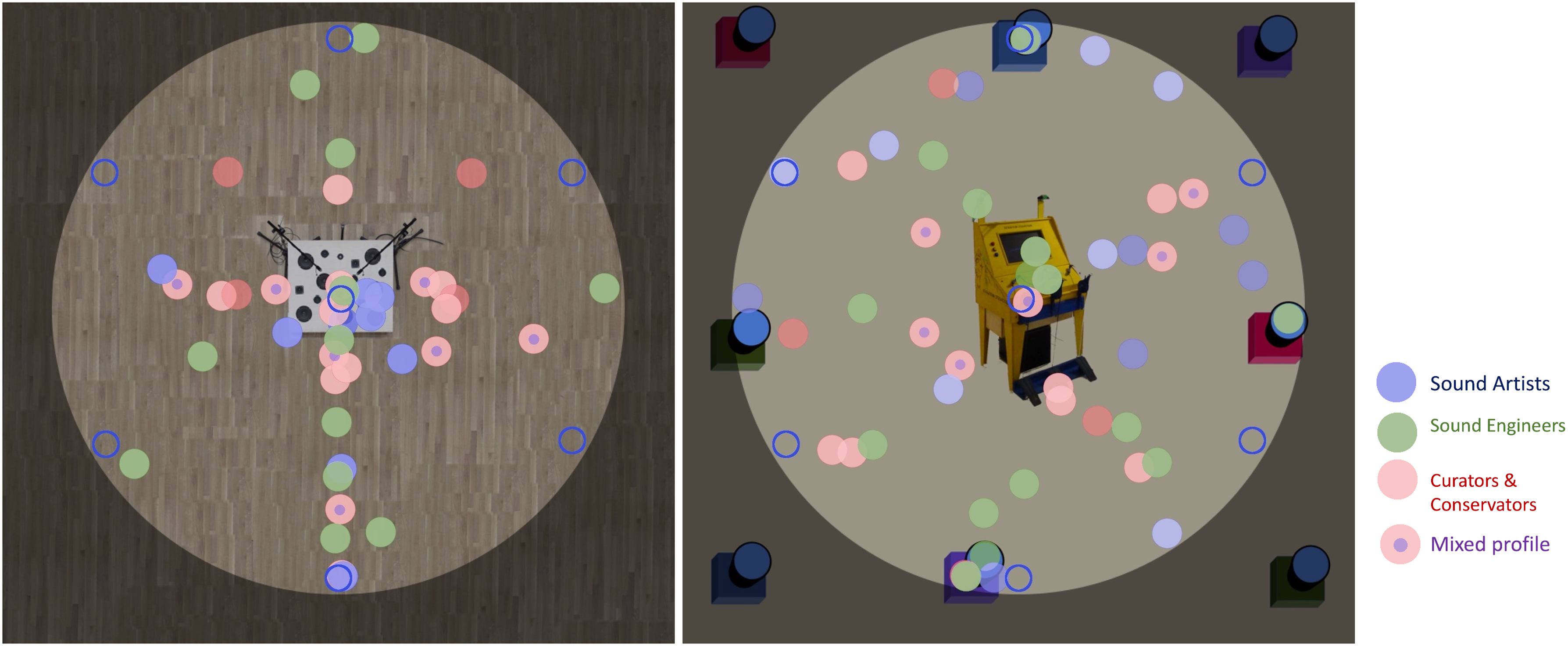

Participants used headphones (Sennheiser HD-280) equipped with an IMU sensor (Yost USB IMU) to feed yaw, roll and pitch values into the HOA renderer. They had control over the general level, which was not calibrated to match the real-life conditions. The virtual position in the sound installation was controlled either with a joystick or a trackpad (Figure 3) while standing up or sitting up, based on the participant’s preference. Interpolation parameters for the HOA renderer were adjusted and validated by ear and according to the geometry of the recording setup by collaborators of the projects, with an expertise in acoustics and sound art creation, to produce a smooth transition between positions for JPG’s work. However, with the limited documentation available for the different parameters (volume threshold, volume range, HOA threshold and HOA range), we were unable to achieve a perfectly smooth transition for ES’s work. We consulted Zylia and relied on their recommended parameters, which led to audible artefacts (discussed in section 4).

Figure 3. Technological setup for participants’ interactive listening session.

2.3. Participants and protocol

Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, we had limited access to museums and galleries, and thus had difficulty in recruiting participants for an in-person study. Sixteen participants, including the two artists, ES and JPG, took part in the study between February and April 2022. They were recruited through convenience and snowball sampling based on the main expertise (Table 1). However, most participants reported expertise in more than one field with varying levels of experience (0 to 5 years; 5 to 10 years; 10 to 20 years; more than 20 years). Two participants are considered as having dual expertise as they reported their highest level of experience in two fields (one SA+SE and one CO+CU). We first piloted the experiment with one sound artist, whose results were included in the study as no changes were made after pilot testing.

Table 1. Distribution of expertise for the participants of the study

Participants started by filling out a screening questionnaire about their expertise and familiarity with the artists and each specific work. We provided a brief description of the work in case they were not familiar with it.

We then introduced the graphical interface and the functionalities for recording significant positions and encouraged them to spend as much time as needed to experience the spatial audio rendition in space and time. They could move freely in space, within a circle centred on the installation represented by the spotlight (Figure 2), as well as navigate in time, within the 10 minutes of the recording. During this exploration, they were asked to select a minimum of three significant positions in space and in time which they considered to be interesting or important for the comprehension of the artwork.

This exploration was followed by a semi-structured interview. The interview guide was structured into three sections corresponding to 1) overall experience, 2) description of the significant positions, and 3) implications for documentation and preservation. Section 3 focused on the distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge, and, more specifically, the notion of significant knowledge proposed by Boutard and Guastavino (Reference Boutard and Guastavino2012), an extension of the notion of significant properties in the domain of digital preservation aimed at modelling the tacit–explicit dimension in documentation methods. A fourth section asked participants to categorise the work using elements of the conceptual framework developed in a previous study (Fraisse et al. Reference Fraisse, Giannini, Guastavino and Boutard2022). However, most participants were not familiar with the terms used and we subsequently decided to exclude this section from the analysis.

The full interview guide is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Interview guide

All participants repeated the process for both works, starting with ES’s work and finishing with JPG’s work.

The free-format descriptions of overall experience (Q1) and significant positions (Q3) were coded by the first two authors using a combination of inductive thematic analysis (to identify themes emerging from the qualitative data) and deductive content analysis (using themes derived from the literature). The significant positions coordinates were analysed in relation to the main expertise of the participants and used for descriptive analysis. The questions on documentation and preservation (Q3) were coded into three ordinal categories, namely: 0-imposible, 1-to some extent, 2-easily for Q3.a; and 0-no, 1-to some extent, 2-yes for Q3.b. We decided to use an open question in Q3.a and Q3.b to be able to check for emerging questions regarding these topics, and while some elements were also included in the inductive part of the analysis, it made the coding into ordinal categories complex and based on the interpretation of the coder, especially for the intermediary level.

3. Results

3.1. Overall experience

Questions on overall experience were used as an introduction to the other parts of the interview and to identify general issues about the sensory experience of the art installation work in a mediated virtual environment that would have importance for documentation methodologies. When relevant, the answers were coded along with the responses of the other sections. The creators of the works recognised their works in the reproduced environment (Q1.d), which served as a validation of the methodology, but also commented on limitations of the spatial rendering and the fixed media rendition of interactive installations. This is inherent to the partial presentation of the work with a document which does not intend to provide a virtual rendition as was done, for example, by Zouhar et al. (Reference Zouhar, Lorenz, Musil, Zmölnig and Höldrich2005) and Lombardo et al. (Reference Lombardo, Valle, Fitch, Tazelaar, Weinzierl and Borczyk2009) for the Philips Pavilion at the Brussels World Fair in 1958, or Cluett and Manzione (The Museum of Modern Art 2020) for David Tudor’s Rainforest V (variation 1).

3.2. Signification positions

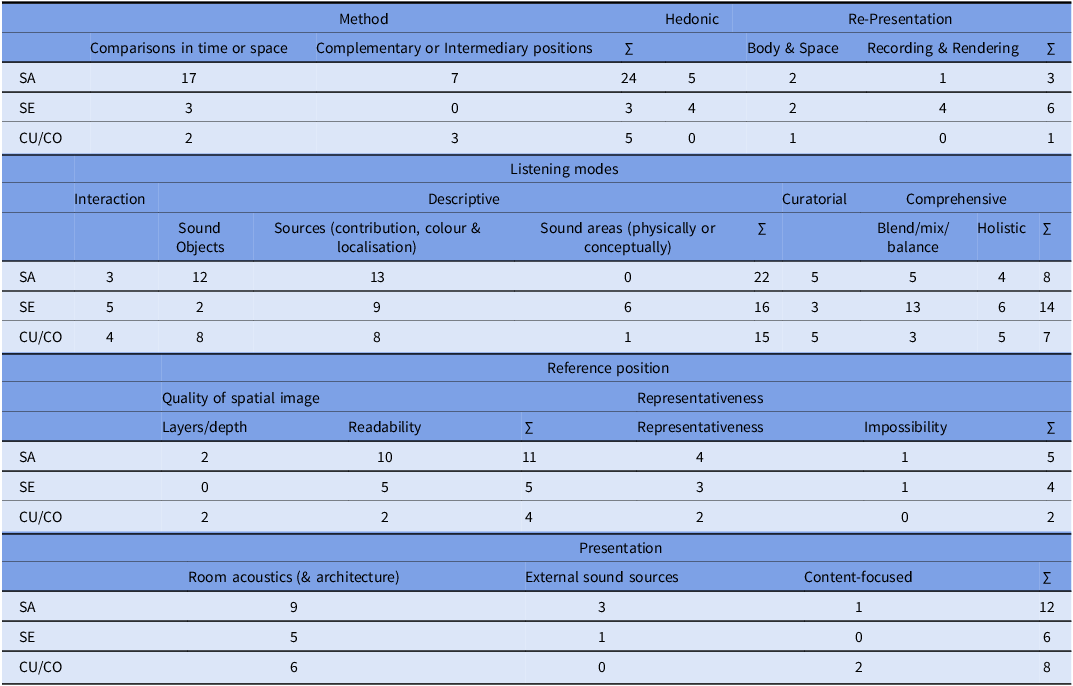

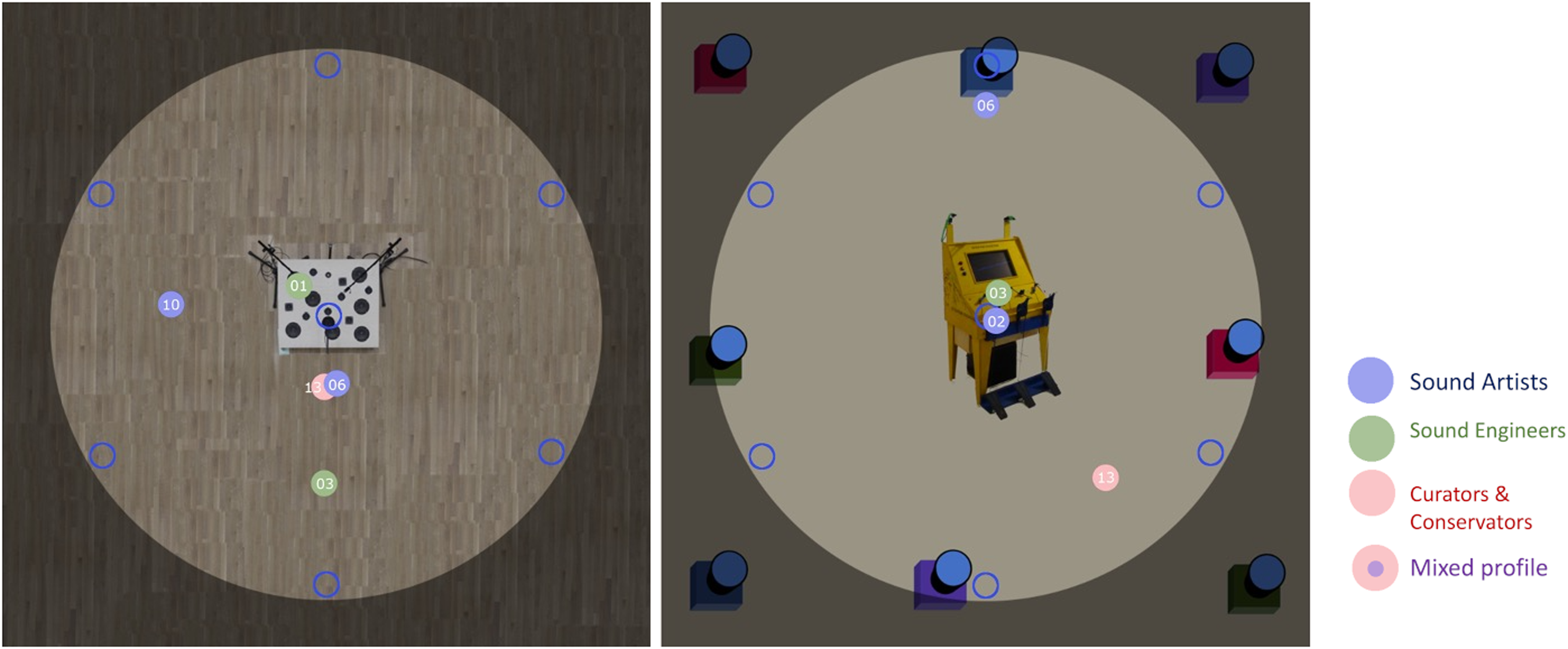

Figure 4 displays all selected significant positions that were described as interesting for reinstallation purposes to some level (Q3.b value of 1 or 2). Bright colours represent the coding of high values (interesting for reinstallation) and darker colours represent the coding of lower values (to a certain extent). Each field of expertise is coded in a separate colour, but we combined conservators and curators as the only conservator was also a curator. The blue circles with no filling represent the microphone positions (not displayed to the participants).

Figure 4. Positions selected by participants that they considered relevant for reinstallation for ES’s work (on the left) and JPG’s work (on the right).

Looking at the whole range of selected positions for both works, the data seem difficult to read. There is a higher readability in the study case of ES’s work than was expected as the installation is centralised in one complex object in the middle of the room.

For ES, we have a clear distinction between, on the one hand, SAs and SEs and, on the other hand, the CUs+COs in terms of geographical spread: CUs+CO selected positions clustered around the central element while SAs and SEs selected positions throughout the listening area, including some further away from the centre. This is consistent with a higher focus on the spatial image within the room, which converges with the analysis of QS1.a and QS1.b (see following section). We also can identify more frontal positions from SAs as compared with SEs. Lastly in terms of tacit and explicit knowledge (not represented in Figure 4), SEs tend to characterise off-centre positions as more complex (tacit) as opposed to the other groups. This last statement is to be taken with extreme caution as the data are scarce and rely on two mappings to ordinal scales.

For JPG, the selected positions are spread across the listening areas, which is consistent with the spread of sound sources (represented in coloured square boxes with a dark blue circle on top). The control interface with the sub is located in the middle. One element that appears is a cluster around sound sources for SE profiles. In addition, the influence of the graphical interface seems to appear more clearly (the selected positions are aligned with the direction of the representation of the control console), which was also acknowledged by some participants (e.g., P08 states: ‘Je pense que j’ai été … influencé par ce que je voyais. … je suis convaincu de tout ça’Footnote 1 ).

3.3. Listening strategies

The qualitative analysis of the reasons for the selection of significant positions was particularly rich and revealed a wide range of listening strategies. Included in this analysis are responses from QS1.a and QS1.b, primarily, but also elements related to these questions but discussed during previous or subsequent questions. The selection contained positions that were deemed interesting for reinstallation as well as not interesting, according to the participants. The coding of the free-format responses was made as a continuous process by two researchers with different fields of expertise relevant to the study: soundscape research, sensory experience, preservation and conservation for art and technology, and documentation of creative processes.

The outcome presented in Table 3 is coded by positions rather than by participants, each case showcasing the number of positions coded in this category, but the coding was not mutually exclusive. One selected position may be coded under several categories and the sum of leaf categories can be less than its actual sum if the same position is coded in several leaf categories pertaining to the same root category. There is no weighting by the number of participants in each category.

Table 3. Summary of the qualitative analysis of listening strategies: number of positions coded in each leaf category according to the expertise and sum for the root category

The top categories are: A-Method; B-Hedonic; C-Re-Presentation; D-Listening modes; E-Reference position; and F-Presentation.

A-Method corresponds to analytical processes developed by participants to make sense of the global soundscape. For example, a comparison of the same position at different times or different positions at the same time (not possible for the actual installation). Interestingly these strategies were primarily discussed by SA profiles and few SE profiles referred to such ideas explicitly.

B-Hedonic corresponds to positions selected for their aesthetic value and the pleasure they give to the participant. P11, a SE profile, states: ‘This is the position that I found to be the most pleasing and could be listened to for twelve minutes.’ P09, also a SE, verbalises it differently: ‘you know, like in a theater when you want to choose a particular space, a particular seat. That was my favorite seat.’ As such it represents a subjective statement that may or may not be related to the selection of a position for its representativeness (as presented here later) and relates to the Subjective listener experiences category in Brost’s framework who adds that ‘whether a sound is pleasant or not can depend on the listener’s cultural background and personal experience’.

C-Re-presentation relates to the technological setup for the study. The artwork is less important in this category and participants reflect on their involvement with the virtual rendering but also with critics of the spatial audio rendering which is further discussed here later. It relates to the document itself and how it relates to the sensory experience of the artwork. In terms of questioning of the spatial audio recording and rendering, it came mostly from SE profiles; for example, P12 who selected a position at equal distance from three microphones states for JPG’s work recording: ‘j’ai choisi cette position d’écoute-là parce qu’il y a comme une transition … Je ne sais pas si c’est la captation ou si c’est la position des colonnes.’Footnote 2 The second perspective in this category, Body & Space, describes the ability to relate to the actual experience of the work. P14, a CU profile, justifies a position described as ‘rather bizarre’ as: ‘j’essayais après d’avoir une expérience de mon corps dans l’espace’.Footnote 3 P14’s statement brings this subcategory closer to Rumsey’s notion of presence: ’defined as the sense of being inside an [enclosed] space’ (Rumsey Reference Rumsey2002: 662).

D-Listening modes is a complex category containing four subcategories. D1-Interaction describes the relation to the actual work considering that both installations could be triggered by the visitors when acting with the interface in the case of JPG or by producing environmental sounds in the case of ES. Several participants noticed sound elements giving an insight into the interactive nature of the work or selected a position that would be the position of a visitor interacting with the sound installation with the intention to relate to the sensory experience in this context.

D2-Descriptive presents strategies focusing on elements of the soundscape, either physically (with sound sources) or acoustically (with sound objects) or geographically (with sound areas). For the latter, one reason for the selection, for example, was the characterisation of the external limit for the sound installation, defining where the visitor is entering its space sonically. SEs tended to focus on sources and areas, whereas SAs and COs+CUs provided a more mixed perspective. Most elements in this general category have been described in previous frameworks and with greater details, namely Fraisse et al. (Reference Fraisse, Giannini, Guastavino and Boutard2022) within their category Sound design approaches, from a sound studies perspective, or Brost (Reference Brost2018) within the category Sonic parameters, from a museum studies perspective. Both are constructed over the design of sound art installation and acknowledge the sensory experience but are limited to a theoretical, top-down perspective rather than an empirical, sensory-based one.

D3-Curatorial relates to trajectories curated by participants. In this paradigm the succession of positions is critical. As such, it relates to Brost’s category Additional listener experiences which ‘describe the key listener positions and the desired listener experience’, but with a narrative. This perspective was indeed proposed by a CO+CU profile, P13 who concludes that the selected position: ‘me semble faire partie d’un parcours naturel chez le visiteur’.Footnote 4 P13 used the same strategy for both works. This category reflects also the idea of an analysis in the form of a ‘signed listening’ as described, notably, by Donin (Reference Donin2004). For example, P05, a SA profile, mentions that ‘tous les points sont une progression du simple vers le complexe’.Footnote 5

D4-Comprehensive proposes the counterpoint to D2-Descriptive with a focus on emergence from the combination of sources and environment rather than specific elements. This includes questions of blend where we find positions giving a balance between the direct sound and the contribution of the room. The contribution of SE profiles is this category is noticeable, as expected. The other part of this category presents strategies that relates directly to the notion of holistic listening, in the sense of analysing the soundscape as a whole rather than individual sound sources or events. Raimbault opposed descriptive listening to holistic hearing which ‘processes the soundscape to as a whole, without specific semantic processing of any sources’ (Raimbault Reference Raimbault2006: 935). P-06 describes such a holistic listening strategy to the overall work thoughout space and time, while relating it to the next category that we will detail: ‘c’est un moment assez représentatif de l’oeuvre et de l’espace. Oui, mais dans son ensemble’.Footnote 6

E-Reference position describes positions that are considered specifically relevant for the understanding of the work in terms of spatial audio, whether for quality of the spatial image, or its representativeness of the work as a whole.

The notion of Quality of the spatial image has received significant research attention in relation to the evaluation of spatial audio reproduction. Guastavino and Katz (Reference Guastavino and Katz2004) identified readability as an important criteria related to the definition of the spatial image and ability to the comprehend a complex auditory scene. While the task of participants was not to evaluate the reproduction, the analysis of their verbalisations points to these concepts. Here, the quality of the spatial image category relates to readability and to the ability to hear depth or different layers. Both are exemplified in P-00’s statement: ‘but here there’s more of a layer involved, or layers, and the atmosphere that it creates is more spatial somehow, there’s more things going on, all around, which are very interesting, it’s interesting to be there and try to focus on all the different details’.

Representativeness is a category that showcases the idea of the work and may be compared with Brost’s (Reference Brost2018) somehow converging category labelled ideal listener experience which ‘describe the artist’s ideal listener experience of the work (orientation and movement of the listener; location, direction, sound intensity/levels, presence or absence of low-frequency vibration, etc.)’. Brost, echoing our research objectives, mentions also that ‘if the artist works closely with a sound professional, ask that person to describe this as well’. This category includes both the representative positions themselves – ‘I think that’s how the composer wanted people to experience this piece’ says SE profile P01 – and references to impossible positions which may or may not be representative. Artist ES exemplified this by selecting an ‘impossible’ position for her own work (on top of the installation, which is not accessible in the physical space) and describing it as ‘almost perfect’. Representativeness is discussed in relation to both space and time. P13 a CO+CU profile, as well as P02, a SA profile with a familiarity with the work, associate the significance of their selection to the distinction between a passive position (for the former) and an active position (for the latter).

F-Presentation refers to everything that is dependent on the exhibition context and the sound art installation as an instance. It relates to the idea of identity versus iteration discussed by Brost (Reference Brost2018) based on the definition of the terms by Phillips (Reference Phillips2015). While the distinction between identity and iteration was of particular importance in JPG’s case – the artist redesigned the control mechanisms because of the pandemic context so that only feet were used – participants could relate to this distinction mainly in relation to a few factors that they identified in their strategies. The first one is room acoustics and its relevance or relation to the work. In this category the focus is on the spatial attributes of the room itself rather than the spatial attributes of the auditory scene within the room (as described by Rumsey Reference Rumsey2002). As Kelly reminds us, ‘a continuing concern to curators of sound in contemporary art is the space of the gallery itself’ (Kelly Reference Kelly2011: 17). P14, a CU profile, for example, questioned the acoustics of the exhibition room for JPG’s work: ‘jusqu’où peut aller cette réverbération-là dans l’oeuvre, jusqu’où on se permet d’aller, parce que des fois ça peut être un choix de l’artiste aussi’Footnote 7 , a statement that resonates with the limitations expressed by JPG in his own interview for this specific exhibition context. This subcategory is indeed well represented in all fields of expertise in Table 3. The top category relates also to external sounds sources emerging from the recording that participants considered as significant and contextualise the artwork, such as traffic noise. P06, a SA profile, mentions traffic noise as: ‘C’est comme un élément parasitaire qui est là, mais qui nous met en contexte plus; on a plus l’impression d’être dans un espace’Footnote 8 , which also relates to the re-presentation category. The last categorial element pertaining to this main category is the complementary choice, in relation to room acoustics, of positions selected for minimising this context (typically, close to the sound sources) and as such relates more to the identity of the artwork, as least in sensory experience terms. Relation between categories and positionBecause of the relatively small amount of data and the large number of categories emerging from the qualitative analysis, it is difficult to extract information from the conflation between the quantitative and the qualitative data. We will show here an example of triangulation to emphasise the tool methodologically and its potential for targeting in future specific categories to extend the research. Figure 5 displays the positions selected for the category Representativeness for both works according to the field of expertise.

Figure 5. Positions selected by participants (with ID) for the category Representativeness.

4. Discussion

This first outcome of the analysis is the impressive variety of listening strategies that participants used during the data collection, which touches on the conceptual frameworks from the different fields of expertise discussed in this study. While there are tendencies in terms of strategies, the crossover established in Table 3 is clear (we take into account the limitations discussed here below), with some interesting takeaways, such as the preference for the global panel of comprehensive strategies for SE profiles as opposed to analytic methods for SA profiles, and the expected focus on sources and sound object by CU+CO profiles (which is consistent with Brost’s framework). The development of narratives in what we have labelled curatorial strategies for all fields of expertise is also interesting in terms of the many ways to create them and could certainly be developed further in terms of research. While a statement to take with caution (see section 3.2), in terms of significant knowledge, the tendency by participants to characterise differently what they consider easier to verbalise in relation to their sensory experience, according to their field of expertise, motivates us to push further this part of the research with an operationalisation of the tacit–explicit dimension that fits a more descriptive inquiry and a focus on several categories. But the diversity of responses to this question from respondents is already an insight into the noteworthiness of this dimension.

Several limitations are part of this study. First, we chose to focus on the auditory immersive experience using a fixed media rendition, thus failing to account for the interactive dimension of the installations. This allowed us to focus on our object of study, namely the document rather than the sound art installation, and to confront our findings to Brost’s framework which is primarily defining sound elements and sound-related elements in the documentation. In the same vein, we chose to use a generic recording protocol, along a predefined array of equally spaced microphones, instead of tailoring the process to fit each work. The rationale was to rely on a pragmatic position to investigate the extent to which we can use simple tools to discuss long-term documentation for sound art installations. By doing so, we also consider that 6DoF spatial audio recordings in the context of documentation would be more of a methodological tool rather than a direct documentation tool, which is consistent with the volume of data to preserve if it were to be the latter, especially at a time were digital archiving community are more and more discussing the environmental impact of digital preservation.

While we intended to enrich the data collection with a third sound art installation with a focus on a site-specific work, which would provide a better range of works, the context of the pandemic did not allow for this extension. Still, the rich data collection and the broad range of categories stemming from the analysis provides a solid ground for further investigations. Furthermore, while a qualitative analysis does not entail generalisability, the analysis with multiple levels of abstraction in the coding allows for further research to be considered at different levels of transferability according to their paradigmatic divergence (evaluated according to Fraisse et al.’s Reference Fraisse, Giannini, Guastavino and Boutard2022 conceptual framework).

The interpolation between recording positions, especially in the case of Estelle’s work, had an impact on the spatial audio features of the rendering, which was acknowledged by several participants and had an impact on the selection of significant positions. The unexpected outcome of this situation is the ability to relate this shortcoming to the documentation principles, especially if we discuss in terms of identity and iteration, or in Brost’s terms Sonic Identity and Installation documentation, by emphasising what is not a part of the work rather than what is, in the same vein as discussed for room acoustics.

Furthermore, in terms of expertise, it should be noted that most participants at least some level of expertise outside of their primary field, so the analysis by expertise should be interpreted with caution. These limitations arose in the context of an exploratory research project trying to carve new research directions in the documentation of sound installation works.

We have made several references to Brost’s framework during the analysis, whether in relation to her inclusion of broad categories relating to listener experience or the specification of sound sources and events. Taking a sensory experience perspective on documentation, we still observe converging categories from our analysis, making clear the potential articulation between both frameworks and the possibility to better specify and define more systematically the elements of listener experience that she proposes. In our opinion, this would require relating the sensory experience and the constituent listening strategies to the elements of documentation themselves rather than defining them as independent categories.

Further research could be conducted by focusing on specific categories and investigating the relevant strategies for each field of expertise. In this study we have used spatial audio recording as a data collection instrument, but this research has now the potential to be extended to multi-expertise collaborative work and to investigate such tools in the context of more ecologically valid tasks relating to the specification of documentation for sound art installation.

5. Conclusion

Documentation of sound art installations is an interdisciplinary endeavor. Brost (Reference Brost2018) made it explicit by stating that ‘for time-based media works that foreground sound, conservators must be conversant with sound physics, acoustics, audio engineering and sound design so that they can have productive conversations with artists and sound professionals in order to create meaningful documentation of the significant aural properties of an artwork for the future’. From our study, the potential for operationalising the interdisciplinary framework discussed by Brost started to emerge with the goal to make documentation procedures better formalised in relation to each field of expertise regarding the sensory experience.

As mentioned earlier, we do not advocate for the use of 6DoF spatial audio recordings as a primary document about the work but rather as a mediation for the specification of documentation methods with all stakeholders. While on the one hand sound artists have their own documentation methods, and in some cases dedicated professionals, and on the other hand museums have their documentation frameworks, this study is positioned within a broader perspective which promotes the design of comprehensive frameworks bridging practices and expertise. In this context, we have proposed to use spatial audio recording as a mediation for discussing, improving and converging on the topic of sound art installation documentation between stakeholders. The fact that we have a broad range of shared strategies to document the sensory experience across fields of expertise with different focuses outlines the potential to use minimal spatial audio recordings tools, such as the those used in this study, for this purpose. We believe that such spatial audio recording could act as a boundary object (Star and Griesemer Reference Star and Griesemer1989) – that is, a tool that allows for several fields of expertise to project their understanding of documentation and discuss specifications and requirements.

Furthermore, the outcome of the qualitative analysis should be confronted with more case studies to assess its dependability. Such a tool has the potential to function as a conceptual framework to review and enrich established documentation procedures.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for funding the SAD-SASK project, Gabriel Lavoie Viau for developing the interface, Jack Kelly and Florian Grond for the recordings, Julien Boissinot and Yves Methot at CIRMMT for their support in the laboratory. We would also like to thank our collaborators for the discussions and guidance: Nicolas Bernier, Seth Cluett, Patricia Falcão, Philippe-Aubert Gauthier and Jack McConchie.