1. INTRODUCTION

Early in the morning of 7 September 2012, nine drivers were arrested in Indonesia’s Pacitan District, on the southern coast of East Java (see Figure 1), for their role in attempting to smuggle 60 Middle-Eastern asylum seekers out of Indonesia and into Australia. A tenth driver was later apprehended in another province after almost two months on the run. The Indonesian National Police charged the drivers with attempted migrant smuggling and the Attorney-General’s Office recommended the statutory minimum sentence of five years in prison.

Figure 1 Map with smuggling operation sites

The trial court then convicted the men but, much to the frustration of the Attorney-General’s Office, the drivers were sentenced to two years in prison, contrasting with the experience of drivers in other smuggling operations tried in other courts, who had received the much more severe minimum sentence. The Attorney-General’s Office appealed on the basis that the judges had not fully applied the law in their verdicts. The reviewing judges increased the sentences, which were still below the minimum sentence. Subsequently, the Supreme Court rejected the Attorney-General Office’s second and final appeal, arguing that the new sentences were severe enough already. Judges have also ignored statutory minimum sentences for other crimes, such as corruption and possession of illicit drugs, so these below-minimum sentences for migrant smuggling are a further resource for examining the extent of judicial discretion in the Indonesian judiciary.

The fact that Indonesian judges ignore statutory sentences undermines an institutional objective of the legal system to achieve legal certainty in terms of the range of punishments, including those for migrant smuggling.Footnote 1 In civil-law jurisdictions, such as Indonesia, law is the primary reference for determining sentences. As a secondary source, judges may also use case-law as a “persuasive force” in their verdicts,Footnote 2 although they seldom do in Indonesia for reasons discussed below.Footnote 3 But, unlike the normative precedent of case-law, embedding sentences in legislation externally imposes rules in areas where judges previously exercised discretionFootnote 4 and, in so doing, draws attention to the systemic tension between the legislature and judiciary, which arises when judges do not agree with the severity of legislated sentences. Such disagreement has long been at the heart of academic and policy debates about the appropriateness of the legislature determining sentences rather than the judiciary.Footnote 5 In Indonesia, the debate has current relevance as the legislature at the time of writing is deliberating a Bill to replace the century-old Penal Code with a new law that, amongst other objectives, seeks to rein in the discretion of judges when handing down sentences.

This article examines the discretionary practice whereby judges sentence people convicted of migrant smuggling to prison terms shorter than the minimum length proscribed by the law. In 2011, the legislature criminalized migrant smuggling, so offenders risk between five and 15 years in prison and a fine of between IDR 500 million (USD 38,000) and IDR 1.5 billion (USD 114,000) even for attempting to commit the crime.Footnote 6 Since then, Indonesian judges have mostly sentenced offenders within the range, but some have resisted, choosing instead to hand down lesser punishments.Footnote 7 Obvious candidates for these sentences are defendants who were children (aged below 18) when they committed the crime, as the children’s criminal justice system does not recognize minimum statutory sentences.Footnote 8 More controversially, other candidates are offenders with limited roles in smuggling operations, such as the transporters who drove to-be-smuggled migrants to their point of departure from Indonesia in the case-study below. Legislators intended judges to apply the minimum sentence in this case, but the judges chose instead to hand down punishments they argued to be more commensurate to the offenders’ role in the crime.

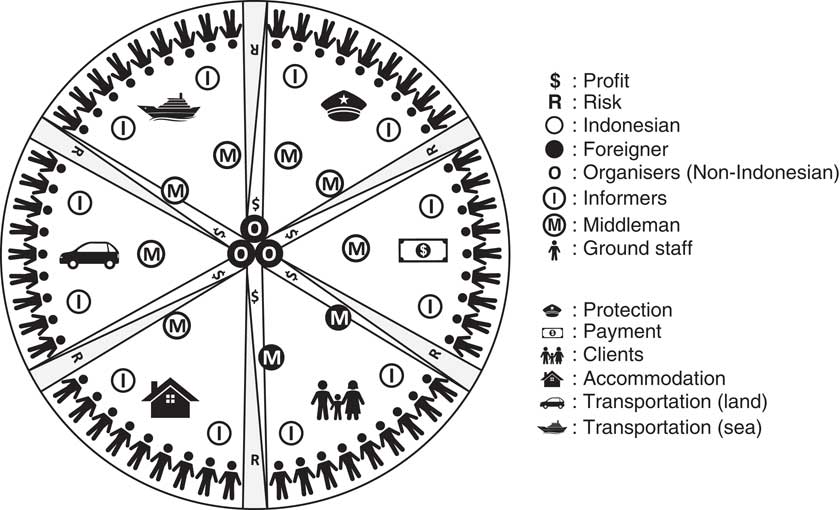

The need for even more differentiated sentencing for migrant smuggling is due to the wide variety of tasks and responsibilities of different actors within the operations. As in other regions in the world, smuggling operations in Indonesia rely on broad networks of foreign organizers and local intermediaries, including money movers, recruiters, facilitators, and transporters (see Figures 2 and 3), who “combine and coordinate their efforts at various stages” of the crime.Footnote 9

Figure 2 Smuggling operation organization chart

Figure 3 Smuggling operation process

However, law-enforcement agencies do not always proceed against all actors.Footnote 10 In Indonesia, it is more common for transporters and their crew to be arrested largely because they are on the crime scene when law enforcers arrive.Footnote 11 Organizers are also known to pay bribes to protectors to encourage law-enforcement agencies to turn a blind eye to the organizers’ involvement. Transporters, then, face greater risk of getting caught and punished. They also stand to make a paltry income, despite these risks, which is not surprising given that the transporters tend to be poor, indebted, and frequently underage.Footnote 12 Organizers exploit the transporters’ precarious state as a core element of their business model to smuggle migrant-clients into another country.

Existing legal studies of migrant smuggling through Indonesia argue the case for more lenient treatment of the often vulnerable transporters well. In a policy report, Melissa Crouch and Antje Missbach have analyzed how the Indonesian legal system handled migrant-smuggling cases in the first 19 months after the activity was criminalized in May 2011.Footnote 13 They have also examined justice officials’ responses to the crime, identifying various forms of discretion used at all stages of criminal proceedings,Footnote 14 including in relation to the Pacitan cases, which are presented as a more detailed case-study below. The Pacitan cases involved ten below-minimum sentences but, in the previous report, only five were examined for the purpose of uncovering the motivations of judges in trial courts in imposing prison terms less than the minimum proscribed by law. In the cases that Crouch and Missbach analyzed, those sentences did not take effect, because they were appealed in the high court and again in the Supreme Court. Consequently, there are now 30 legal decisions, which document how judges at all levels of the judiciary rationalized the wide use of discretion in their sentencing. An examination of 99 convictions for migrant smuggling in the first three and a half years after May 2011 found that this discretionary practice remained prevalent, as judges used discretion in more than one-fifth of cases.Footnote 15

This article builds on these earlier studies by examining in depth how and why judges at all levels of the judiciary applied below-minimum sentences in the Pacitan cases. In doing so, it offers a fuller analysis of judicial discretion in sentencing migrant smuggling more generally and also in other crimes, such as corruption and possession of illicit drugs, which are also controversially known to be punished with below-minimum sentences and fines. At this stage, it is not possible to determine the full extent to which the legislature considered the purpose and potential implications of the statutory sentence range for the migrant-smuggling legislation because public record of how legislators discussed the offence is incomplete, as not all relevant documents were stored in the legislature’s archives once the law was passed. Notably, the academic study (naskah akademik), which ought to be produced for each Bill under discussion, is missing. As a result, it is difficult to know how, or even whether, the legislature prioritized criminalization of migrant smuggling when the Bill was tabled, which could help to explain why the judges in the following case-study resisted handing down the severe minimum sentence for the crime.

In this article, we explain how and why the judges in the Pacitan cases reconciled the relatively severe statutory minimum sentence for migrant smuggling with the lesser role played by transporters in the overall operation. To support our argument, we first outline the theoretical case for statutory minimum sentencing and its implications for judicial discretion to sentence criminals. Second, to situate the sentencing regime in a national context, we focus on statutory sentences in Indonesia by discussing their history, system, implementation, and role in sentencing criminals. We then consider the application of the statutory sentence for migrant smuggling to show that the minimum sentence is not commensurate with the limited role that transporters play in the crime. Third, we use the Pacitan cases to show how and why the judiciary ultimately upheld sentences below the statutory minimum. We then discuss the implications of the Pacitan cases’ sentences for judicial discretion in the Indonesian legal system and what they say about the relationship between the judiciary and the national legislature, and we compare the scope of discretion to that available to judges in the legal system of Indonesia’s neighbour, Australia. In conclusion, we argue that such discretion does not just enable more lenient sentences for transporters in smuggling operations, but also shows how the Supreme Court plays a de facto judicial review function in Indonesia’s legal system.

2. MINIMUM STATUTORY SENTENCES AND JUDICIAL DISCRETION

Modern legislatures frequently specify statutory minimum sentences to limit judicial discretion in relation to particular crimes. By legislating sentences, a legislature limits the discretion of judges and thus introduces more “certainty and completeness in the law.”Footnote 16 There are also other reasons for legislatures to set minimum sentences. Law-makers in democratic countries may introduce minimum prison terms and fines for crimes such as rape or murder in their attempts to shore up political support for re-election. They have also introduced minimum sentences to meet international legal obligations requiring criminalization of an activity and punishment of crime. Regardless of the reason for setting sentences in law, the legislature’s expectation is that the judiciary will adhere to the statutory regime when determining them.

The legislative process may involve the judiciary to ascertain judges’ views about sentencing practice and, in so doing, take into account their values and norms when deciding whether and how to legislate the punishment of certain crimes. Law-makers can also refer to the theory of penology—the branch of criminology that deals with the philosophy of punishment—to find a sentence commensurate to the crime that achieves criminal justice objectives in terms of deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and retribution. In practice, however, statutory sentences may lack this theoretical underpinning, as law-makers opt instead for a model of crime control that seeks to reduce crime by increasing the investigative and prosecutorial powers of the state. This model assumes that deterrence is more efficient if convicted criminals are punished with the maximum possible penalty. Among other assumptions are that law-makers have enough knowledge to determine the probability of conviction and sentencing, and that it will be more costly to find and convict another offender to punish if the case against one offender fails. The logic of this model encourages legislation of severe minimum sentences, in spite of evidence that “getting tough on crime” is not always the most effective deterrent of future crime.Footnote 17

Legislatures have also enacted a uniform methodology for judges to determine sentences. In 1984, for example, the US Congress passed a Bill establishing an independent agency within the judiciary to rationalize sentencing for crimes with maximum punishments of between six months and life in prison.Footnote 18 In large part, it was passed by the law-makers in response to criticism that judges exercised too much discretion. There were sometimes sentencing disparities among different judges for the same crime in similar conditions and an examination of the decision-making process revealed that judges had different starting points for determining sentence severity. While some judges started at the minimum sentence and worked their way upwards as aggravating circumstances emerged, others started at the maximum sentence and reduced it after finding mitigating factors, and others started in the middle and adjusted the sentence upwards and downwards as the facts of a case came to light. Each legal system may or may not have a preferred method for determining sentences but, as with statutory sentences, statutory guidelines impose legal structures in areas otherwise governed by judicial discretion and stipulate when and how judges should sentence criminals.

In common-law systems, judges often look for legal precedent in case-law when determining sentences for criminals. This practice is not as frequent in civil-law contexts, although its judges do use case-law as normative precedents with “persuasive power” to justify their sentences.Footnote 19 There are also practical reasons for judges not referring to case-law more frequently in sentence determination. The judges may not be supported by the necessary infrastructure to easily search and get access to case-law and, consequently, be unaware of developments elsewhere in the judiciary.Footnote 20 They may also be under pressure from large caseloads and lack the time to check what other judges are doing. This article examines a situation in which offenders were charged, prosecuted, and convicted of attempted migrant smuggling in Indonesia but, for reasons discussed below, then received punishments below the statutory minimum without reference to a precent. Before this case is presented, the following section considers the minimum statutory sentence in Indonesia, elaborating on tensions between the legislature and judiciary that have intensified since the end of the authoritarian New Order regime (1967–98), partly because regime change has further enabled the judiciary to act as an independent check on the government’s legislative and executive power.Footnote 21

3. THE MINIMUM STATUTORY SENTENCE IN INDONESIA

Severe minimum sentences are relatively new in Indonesia. The Penal Code, enacted under the Dutch colonial administration, stipulates that the statutory minimum prison sentence is one day only and the maximum punishment, other than the death penalty, is 15 years.Footnote 22 The Code gives judges wide discretion to punish an offender with prison sentences they deem commensurate to the role the offender played in the crime. Indonesia’s national legislature (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR) has progressively curtailed the discretion by replacing parts of the Code covering often general and less serious offences with more specialist laws known as lex spesialis that may proscribe more severe minimum and maximum punishments. Law-makers claim the legal authority to do so by pointing to an article in the Code stipulating that its sentences apply “except if set by another law.”Footnote 23 The provision allows the DPR to update criminal law without amending the Code, which has proved remarkably difficult to do and remained high on the national legislative agenda in 2017. The legislative additions bring Indonesian law into line with contemporary developments, such as adhering to international legal obligations arising from ratification of international conventions such as the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime and its protocols, which have made it necessary to criminalize migrant smuggling and human trafficking,Footnote 24 and for which the DPR has legislated severe minimum sentences.

Every time the DPR enacts statutory sentences, it limits the judiciary’s discretion. Some judges in the general courts have resisted by ignoring statutory minimum sentences when punishing criminals. Their decisions may be appealed but, because courts of appeal have approved sentences below the statutory minimum, the DPR has distributed jurisdiction to adjudicate cases to specialist courts intended to adhere to the law in their sentencing. In 2005, an anti-corruption court with Indonesia-wide jurisdiction began trying corruption cases in Jakarta referred for prosecution by the Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, KPK).Footnote 25 The general courts continued to hear corruption cases handled by the Attorney-General’s Office, but the specialist court’s relatively high conviction rate and sentence severity quickly earned it and the KPK a strong anti-corruption reputation. By contrast, the general courts continued acquitting defendants and handing down sentences below the statutory minimum. In 2006, the Constitutional Court ruled that the general-specialist court system was unconstitutional, on grounds that all defendants should be entitled to equal treatment, and gave the government three years to work out another arrangement. In 2009, the DPR legislated for specialist courts to hear all corruption cases in an extraordinary move that completely removed legal proceedings in corruption cases from the jurisdiction of general courtsFootnote 26 but has, nevertheless, led to more acquittals and has arguably weakened the specialist court system’s anti-corruption reputation.Footnote 27

The law does not always provide sufficient instruction for judges to sentence defendants in line with objectives that law-makers had in mind when they legislated the sentences. The judiciary has partly overcome this challenge through internal policy. To illustrate, on the one hand, law-makers opted to send users of illicit substances to rehabilitation centres rather than punish them onlyFootnote 28 but, on the other, they increased the punishment for possession of illegal substances without acknowledging that drug users often carry drugs both for personal use and for sale. Consequently, judges handed down sentences ranging from referral to rehabilitation services, as required by the decriminalization measure, to the minimum statutory punishment of four years in prison for possession. Controversially, judges also sentenced convicts to less than the minimum punishment.Footnote 29 Six months after Law No. 35 of 2009 on Narcotics came into force, the Supreme Court addressed the situation by issuing a memorandum that called on judges to sentence drug users in possession of illicit substances below a maximum quantity to rehabilitation services, especially if they were not involved in the drug trade.Footnote 30 In effect, the policy provided judges with the necessary guidance to make more consistent, institutional use of the law in their sentencing and thus reduce the wide discrepancies in sentencing decisions.

Judges may also hand down sentences outside the statutory range, especially when prosecutors pursue the wrong offence. Judges may sentence defendants in such cases in line with the punishments of other offences with which it would have been more appropriate to charge them. For example, police and prosecutors do not always establish that defendants in drug-possession cases are also drug users, and thus entitled to special treatment, before referring their cases for trial.Footnote 31 The fact often comes to light during cross-examination in court, so the Supreme Court issued a memorandum instructing judges to correct the technical error in the legal proceedings by re-categorizing such defendants as drug users for sentencing purposes.Footnote 32 This policy was issued in January 2015, one month after the president of Indonesia declared drug-related deaths a state emergency,Footnote 33 which had resulted in more law-enforcement activity and increased legal proceedings against vulnerable people who were legally entitled to special treatment. Having outlined discretionary praxes in other spheres, the following section examines the statutory minimum sentence for migrant smuggling—a crime that has not received as much public attention in Indonesia, largely because of the false perception that Indonesian people are not victims of the crime.

3.1 The Migrant-Smuggling Offence

Along with 124 governments, Indonesia signed the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime in 2000, which included provisions for mutual legal assistance, extradition of offenders, law-enforcement co-operation, and technical assistance and training to suppress transnational organized crime. Associated with the Convention was the Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air (hereafter Smuggling Protocol), which targeted migrant smuggling—a form of irregular migration that had increased substantially in Indonesia as more asylum seekers passed through the country on their journey to their desired final destination in neighbouring Australia.Footnote 34

The Indonesian government did not ratify the Convention until 2009.Footnote 35 Earlier, it was concerned about the loss of power to decide whether bilateral disputes over interpretation of the Convention could be registered with the International Court of Justice.Footnote 36 By 2008, the government of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono wanted the Bill passed as soon as possible, but a law-maker outside the ruling party argued that ratification should only follow the incorporation of all legal obligations into national law. At the time, there was no specific law that criminalized migrant smuggling, so the criminal justice system had been using related offences under Law No. 9 of 1992 on Immigration and Law No. 17 of 2008 on Shipping.Footnote 37 The maximum possible sentences were five years in prison (used to punish migrants without immigration permission to be in the country)Footnote 38 and a fine of up to IDR 600 million (USD 58,000) (used to punish boat captains without clearance to sail),Footnote 39 which are comparable to the minimum statutory sentence that the DPR later set for migrant smuggling two years after it ratified the Convention. The newly established offence under Law No. 6 of 2011 on Immigration meant that anyone involved in smuggling operations could spend between five and 15 years in prison and pay a fine of between IDR 500 million (USD 38,000) and IDR 1.5 billion (USD 114,000).Footnote 40

By introducing a severe minimum sentence for migrant smuggling, the DPR went beyond the international legal obligation to criminalize and punish the activity. Indeed, the Smuggling Protocol requires ratifying states to introduce commensurate punishments and the United Nations Model Law against Smuggling of Migrants promotes the relatively harsh New Zealand approach, which threatens a maximum sentence of 20 years in prison and/or a NZD 500,000 (USD 350,000) fine as an international standard for punishment of the crime.Footnote 41 Ultimately, the Indonesian maximum sentence ended up being less severe, with a financial penalty less than one-third of the recommendation and the prison term only three-quarters. These lower maximum sentences do not necessarily mean that Indonesian law is soft on migrant smuggling. To ensure tough treatment of all criminals, especially those who play relatively small roles in smuggling operations, the DPR introduced a severe minimum punishment, as outlined in the preceding paragraph. This legislative act ought to have removed judicial discretion to sentence anyone involved in a smuggling operation to a prison term of less than five years. Although this was certainly the intention, as the following case-study shows, not all judges apply minimum statutory punishments in their sentences.

The severity of the statutory sentences was, in part, also a response to the increasing professionalization of smuggling operations in the late 2000s. Until the late 1990s, smuggling operations through Indonesia were amateurish,Footnote 42 but this began to change as the number of migrants arriving in Indonesia on their journey towards Australia grew and law enforcement there increased pressure on smugglers to avoid detection. Foreign nationals from the migrants’ home countries co-ordinated the smuggling operations.Footnote 43 Disgruntled asylum seekers who remained in Indonesia after their claims for international protection had been rejected by the local representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees became involved in certain capacities.Footnote 44 While foreigners perform the roles of organizers and client recruiters, Indonesians facilitate the operations by providing protection, payment, accommodation, and transportation services during the movement phase of the operation.Footnote 45 In other words, most, if not all, of the Indonesians involved play practical and other operational roles in what is a sophisticated crime, with different levels of risk and remuneration for all those involved.

The minimum sentence is not always commensurate with the role played by transporters in smuggling operations. Consistency and fairness in sentencing are missing across the wide spectrum of people who are deemed to be smuggling offenders. The discrepancies are most apparent when transporters are investigated, prosecuted, and punished under Article 120 of Law No. 6 of 2011 on Immigration, which stipulates the same sentence range for migrant smuggling and intent to commit the crime. In other words, those who commit migrant smuggling and those who intend to commit the crime risk the same severe minimum punishment of five years in prison and a IDR 500 million (USD 38,000) fine, even though the crimes are qualitatively different. Offenders punished for attempted migrant smuggling may have shown intent to commit the crime and taken significant steps towards doing so but, for reasons usually outside the control of these offenders, such as the disruption of the operation by police, crime is not actually committed. Offenders in such operations receive the same punishment as those involved in successful operations. The transporters involved in disrupted operations also face the fact that they receive no payment for their services, which is often their primary motivation for becoming involved in such operations in the first place.

The Attorney-General’s Office determines the range of offences for judges to consider during the trials. The offences are outlined in the indictment (surat dakwaan), which is finalized before cases are referred for trial and normally read in the first hearing. Prosecutors can accuse defendants of standalone or alternative offences. Both forms of indictment may be for primary and subsidiary offences, which judges should consider in that order when deciding criminal liability. In migrant-smuggling cases, the primary offence is Article 120 of Law No. 6 of 2011 on Immigration.Footnote 46 Subsidiary offences are known as lesser offences and typically have less severe sentences, including Article 114 in the same law, which criminalizes the transportation of people outside immigration checkpoints. Officially, the Attorney-General’s Office uses this tiered approach to indictment if there is insufficient evidence to prove criminal liability for the primary offence. A motivation here is to ensure that the defendant is at least convicted of the lesser offence, even though the sentence is not as severe as for the primary one. However, the Attorney-General’s Office is also widely known to be notoriously corrupt, as prosecutors privately admit to taking bribes in return for including lesser offences in the indictment, which ensures that the less severe sentences are an option for judges.Footnote 47

The recommended sentence for the crime ought to be within the statutory range of punishments stipulated in the law. The Attorney-General’s Office requires prosecutors to recommend sentences that are within the range as part of a commitment to legal certaintyFootnote 48 —a practice that is an example of “rule by law” in the Indonesian legal system.Footnote 49 In large part, the Attorney-General’s Office also requires such a commitment because it is an executive government agency tasked by the president to implement and enforce the laws enacted by the legislature as a matter of routine. Therefore, all legal proceedings that designate migrant smuggling as an offence recommend a sentence within the statutory range. The Attorney-General’s Office presents this recommendation in the penultimate session of the trial in what is known as surat tuntutan. It is normally approved by the Junior Attorney-General for General Crimes in Jakarta through the rentut process, whereby higher-level prosecution offices sign off on the sentencing recommendations of lower-level offices. This system ensures that the Attorney-General’s Office can maintain internal consistency in the sentences recommended through over 400 prosecution offices in the country. In so doing, it enables the Attorney-General’s Office to effectively enforce institutional policies, including the policy that requires sentencing recommendations to fall within the range of statutory punishments, so that defendants have some legal certainty about how long they might spend in prison.

For this reason, it is also Supreme Court policy that judges should only consider offences included in the indictment. The Criminal Procedure Code stipulates this requirement but, at the same time, it gives judges significant discretion to determine a sentence. In theory, then, judges must consider criminal liability for migrant smuggling if the offence is included in the indictment. In theory, there is also an expectation that judges sentence offenders within the statutory range of punishments for those crimes. In practice, however, not all judges do so, ignoring minimum statutory punishments, which are not only determined by the legislature, but often demanded as a matter of routine by the Attorney-General’s Office. The following case-study examines one such situation, in which the Attorney-General’s Office demanded sentences just above the statutory minimum punishment for migrant smuggling, but judges then applied sentences well below that minimum.

4. THE PACITAN CASES

We return now to the 2012 cases of the nine drivers arrested in the Pacitan District and another arrested elsewhere for attempting to smuggle 60 asylum seekers,Footnote 50 summarized in the opening paragraph of this article. The men were convicted of migrant smuggling for driving the asylum seekers from Jakarta to Tamperan Port on the south coast of Java, where they were to be shuttled out to the boat waiting out at sea to make the 640-kilometre journey to Australia’s Christmas Island. The police were ready because they had received intelligence from an undocumented source the day before. They arrested five drivers in the port, four in a nearby area as the drivers attempted to escape, and one in the faraway Riau Islands months later.

The organizers and boat crew waiting offshore on the boat were not arrested then because they were not at any of the crime scenes. It took only four weeks for the police to complete their investigation and for prosecutors to then refer the cases for trial. Ultimately, the judges agreed with the prosecutors’ claim that the drivers were guilty of attempted migrant smuggling, but they disagreed with the recommended sentence of six years in prison and IDR 500 million (USD 38,000) fine, so handed down less severe punishments that were below the statutory minimum sentence of five years.Footnote 51

The judges sentenced nine drivers to two years in prison and a IDR 500 million (USD 38,000) fine, allowing the convicts to substitute the fine for an additional month in prison if they lacked the means to pay. Poor Indonesians often serve the extra time because fines of such amounts equate to what they might earn over 15 years or longer.Footnote 52 The runaway driver got an additional four months and was required to spend an extra two months in prison as a substitute for the fine.Footnote 53 The criminal justice system proceeded against the men in separate cases, and each of the drivers had assigned lawyers (who are generally of little help). Judges held between four and five hearings in each trial, at which the charges were laid, the witness statements read, other evidence produced, and the defendants cross-examined. The cases were split between two senior judges who were later appointed as heads of trial courts in Kotabumi, Lampung province and Takalar in South Sulawesi. Despite the division of labour, the legal reasoning in the written decisions is identical, suggesting that the judges communicated with each other about how to sentence the defendants whose legal proceedings were connected. Consequently, the judges and the courts they represented at the time adopted a consistent institutional approach in punishing Indonesian drivers in smuggling operations.

Prosecutors recommended a punishment above the minimum sentence for attempted migrant smuggling after hearing all the facts of the cases. Rather than the minimum sentence, they sought six years’ imprisonment and four additional months for those who failed to pay the IDR 500 million (USD 38,000) fine. The prosecutors sought the severe sentence because the drivers had undermined government efforts to crack down on migrant smuggling and other transnational crimes. Furthermore, the Attorney-General’s Office has, at least since 2006, categorized migrant smuggling as an important crime (perkara penting).Footnote 54 These crimes deserve special attention from the most senior level in the Attorney-General’s Office, as the modus operandi of their perpetrators can be sophisticated; they may have implications for national security and there may be a tendency of law-enforcement agencies to deviate from the law in legal proceedings against offenders.Footnote 55 As a result, the prosecutors in the drivers’ cases had to obtain approval from the district prosecution office in Pacitan first, then from the East Java High Prosecution Office in Surabaya, and finally from the Attorney-General’s Office in Jakarta in deciding on what sentence to recommend. In this multi-actor process, higher-level prosecution offices have the opportunity to correct the sentencing recommendations of lower-level offices if those sentences are below the statutory minimum.

In the Pacitan cases, the judges disagreed with the prosecutors’ recommended sentence. They also disagreed that the less harsh minimum sentence was commensurate with the crime, taking exception to the fact that the severity was out of sync with sentences for similar immigration offences, such as transporting passengers outside immigration checkpoints, for which the minimum punishment is two years in prison and/or a IDR 200 million (USD 15,000) fine.Footnote 56 The judges also noted that the minimum sentences for other crimes were less severe, citing in particular corruption and trade in illicit substances,Footnote 57 for each of which the sentence is four years’ imprisonment. In their minds, the relatively severe punishment for migrant smuggling was in conflict with Law No. 39 of 1999 on Human Rights, which proscribes discrimination.Footnote 58 On the one hand, immigration law criminalizes migrant smuggling and punishes Indonesian citizens yet, on the other, it prevents legal proceedings against migrants who use the criminalized services of migrant smugglers. In practice, only those migrants who have a claim to asylum are entitled to the exemption from prosecution. The judges remarked that this is unfair, because Indonesian citizens are punished when they would not have become involved in the crime if the international protection system for refugees resettled migrants more quickly. In effect, they viewed the defendants as victims of a systemic failure that makes the migrant-smuggling business possible.

The judges claimed legal authority to apply sentences below the statutory minimum and explained that judges do not only apply the law just for the sake of legal certainty, but also think about whether doing so goes against the principle of justice in law enforcement, which they argue to be more important. They pointed to the Constitution in their legal reasoning, which enshrines the legal responsibility to uphold law and justiceFootnote 59 and which is reiterated in the Law on Judicial Power, to justify their legal authority.Footnote 60 The judges then argued that they could only uphold justice if they used other sources of law to determine an alternative but just sentence. In these cases, they referred to Article 114 in Law No. 6 of 2011 on Immigration, which criminalizes transporting passengers without immigration clearance. Like migrant smuggling, a purpose of this offence is to criminalize unauthorized movement of people but, as discussed above, no minimum sentence is stipulated in the law. There is, however, a maximum sentence of two years in prison for this offence, which the judges in the Pacitan cases used as the basis for determining an alternative minimum punishment for migrant smuggling. In other words, the judges convicted the transporters of migrant smuggling, but handed down sentences for another offence, as the Supreme Court recommends judges should do in the cases of some drug users charged with possession.

The judges considered two other factors in their deliberation of a commensurate sentence for the offenders. First, they examined the role that the drivers played in the crime, deeming it relatively minor compared to that played by organizers of the smuggling operation. In these cases, the police did not arrest the organizers, who played a much larger role in co-ordinating the entire operation, but placed them on the Daftar Pencarian Orang (Most Wanted Persons List). The organizers recruited the drivers and ensured that they picked up the migrants and moved them to where they should have boarded a boat to Australia. According to the witness statements, the organizer did not accompany the drivers and migrants all the way to the coast, but travelled in a separate vehicle that left the convoy as it turned towards the beach. The reason for this is unknown but, by leaving the convoy, the organizer distanced himself from the drivers who were later arrested. The drivers reported that they were unable to contact the organizer after their arrest, which the judges used as evidence to argue that the offenders worked in a disconnected part of the network (jaringan terputus) and were not ultimately responsible for the overall execution of the criminal operation.

Second, the judges said that the punishment should take into account the offender’s motivation for committing the crime. The organizers promised each transporter IDR 5 million (USD 375) if the migrants arrived in Tamperan Port and boarded the boat to Australia’s Christmas Island. Their promised recompense was small compared with the substantially higher profit the organizers would reap. For example, each transporter in a 2012 operation collected only USD 170, while the total paid by the more than 50 migrants they transported was at least USD 325,000 for the smuggling service.Footnote 61 The judges noted that the transporters did not actually receive their payment because the police disrupted the smuggling operation before the migrants could be transferred to the boat. The drivers had only received a per diem payment of IDR 1.5 million (USD 113) to cover the cost of transporting the migrants from Jakarta to Pacitan. The judges also noted that the drivers’ involvement in the crime was incidental and that at least one of them had previously transported migrants on one other occasion.Footnote 62 The repeat offender received the same sentence as the first-time offenders. Furthermore, the judges argued that the drivers may have agreed to the illegal work because they did not have ongoing employment and so needed the additional income to make ends meet.Footnote 63

The prosecutors appealed the sentences, arguing that the judges applied punishments below the statutory minimum and thus undermined the national government’s commitment to deter others from committing the crime. Separately, the Surabaya High Court judges accepted the appeals and increased the sentence severity in each case, raising the prison sentences to three years because they agreed that the sentences handed down in the trial courts were not severe enough to deter future offenders. The high court judges’ sentences still fell short of the minimum sentence of five years, as they agreed with the trial court judges that the punishment was too severe and not commensurate to the drivers’ role in and motivation for committing the crime. The prosecutors made a further appeal to the Supreme Court, as did the drivers who felt their new below-minimum sentences were too severe. The Supreme Court rejected the appeals, arguing that the lower court judges had legal authority to hand down sentences below the statutory minimum, that they had justified their decision to do so, and that the punishments were sufficiently severe.

5. JUDICIAL DISCRETION, STATUTORY MINIMUM SENTENCES, AND INDONESIAN COURTS

The judiciary’s handling of the Pacitan cases raises a key question concerning justice for transporters in migrant-smuggling operations through Indonesia: given that the Supreme Court allows judges to sentence transporters below the statutory minimum, why do all judges not do it more often? On a technical level, the answer is relatively simple. The Supreme Court has not issued a policy that requires all judges to adopt this institutional approach, as it has done for narcotics cases involving drug users. Furthermore, Indonesian judges are not in the habit of researching precedents.Footnote 64 It is unlikely that these judges will learn of the Supreme Court’s approval to hand down below-minimum sentences to transporters in migrant-smuggling operations. Consequently, judges are likely to continue to apply divergent sentences in similar and sometimes closely related cases. Awareness of the option to apply below-minimum sentences also has implications for career advancement of judges. Most judges perceive handing down below-minimum sentences as an extreme use of their discretion that ought to be avoided as a rule. However, handing down such sentences does not necessarily negatively affect judges’ chances for promotion, as demonstrated by two of the trial court judges in the Pacitan cases who were later promoted to the most senior management position in other trial courts.

Their exercising of judicial discretion highlights a point of tension within government about how migrant smuggling should be punished in Indonesia. All three levels of the Attorney-General’s Office, which is part of the executive branch of government, recommended to the judges in the Pacitan cases the legislature’s minimum sentence for migrant smuggling. The judges then ignored it when determining actual sentences for the offenders. This is not in itself exceptional, because it is a judge’s right to do so. What is noteworthy here is that the judges ignored a sentence that was not only recommended by the executive branch of government, but also determined by the stipulation of a statutory minimum in legislation. In part, this disagreement about minimum severity may be due to different understandings of how best to achieve the criminal justice objectives of deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and retribution. After all, even the Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts that the statutory punishment was too severe and not commensurate to the offenders’ roles in the crime. Elsewhere, the executive branch of government has acknowledged the need to prevent the employment of poor and otherwise vulnerable Indonesians in smuggling operations through Indonesia.Footnote 65 However, these vulnerable people still risk severe punishment for even attempting to commit the crime, as suggested by the outcome of the Pacitan cases. Interpreted in this context, we find that the below-minimum sentences seem to assert that the government should differentiate in its responses to the multitude of criminal roles that make migrant-smuggling operations possible.

Indonesian judges, with such wide discretionary powers in sentencing, are in a very different situation to their counterparts in Australia, who have no choice but to apply the statutory sentence for migrant smuggling. In the last decade or so, they have worked through a very heavy case-load of smuggling cases, many of which have involved Indonesian transporters. The Judicial Conference of Australia, the representative association of judges in the Australian court system, has criticized the mandatory sentences as “manifestly unjust” when sentencing transporters in smuggling operations, who are mostly poor and illiterate fishermen from East Indonesia.Footnote 66 Under Australian law, offenders who smuggle at least five migrants risk a mandatory sentence of at least five years in prison. Repeat offenders and those whose involvement leads to the abuse and/or exploitation of smuggled migrants risk sentences of at least eight years.Footnote 67 A just punishment for transporters and others with practical and operational roles in migrant-smuggling operations would be less than these minimum sentences.Footnote 68 By contrast, judges in Indonesia can and do hand down more lenient sentences, as they did in their handling of the Pacitan cases. In other words, the discretion available to Indonesian judges (but not to Australian judges) enables them to avoid the traps of statutory sentencing regimes that are not commensurate to the actual roles offenders play in the crime they have been prosecuted for.

This judicial interpretation role assumed by judges at all levels of the general court system shows that judges of the Constitutional Court, which is understood to be the authority to assess whether laws enacted by the legislature comply with the Constitution, are not alone in having a judicial review function. In theory, judicial review is one of the Constitutional Court’s exclusive mandates but, in practice, judges in the general court system also perform a judicial review function as demonstrated in the Pacitan cases, in which the Supreme Court allowed lower courts to ignore statutory punishments in their sentences. Thus, the Supreme Court has effectively assumed a judicial review function that assesses whether statutory sentences are just. By assuming such a function, the Supreme Court undermines the application of legal and policy frameworks that are to a certain extent flawed, for example in mandating severe punishments that are not commensurate to the crime, as in the Pacitan cases, and fail to deter future crime. In effect, the Supreme Court reviewed the statutory sentencing regime for migrant smuggling by adding that judges may ignore statutory minimum prison terms if convicted migrant smugglers are transporters in failed attempts to commit the crime.

6. CONCLUSION

If the Supreme Court has overreached its authority by reviewing the statutory minimum sentence for migrant smuggling in the Pacitan cases, then it has negative implications for the rule of law in Indonesia. Legally, only the Constitutional Court has exclusive authority to review such “high-level” matters.Footnote 69 The fact that the Supreme Court does so, despite that it is beyond its legal responsibility, may be seen as an inadequacy in the government’s overall capacity to enforce law. Yet, the Supreme Court’s actions are a further indication of how that court has come to claim greater judicial independence in the post-authoritarian period (from 1998 on) in Indonesia.Footnote 70 Previously, presidents successfully subjugated (Soekarno, 1945–66) and co-opted (Soeharto, 1967–98) the Supreme Court so that its judges invariably supported government activities, which would have then meant that the judges would have obediently applied the statutory minimum sentence in the Pacitan cases. The Supreme Court’s assertion of the right to act contrary to the expectations of other branches of government (legislative and executive), which should constrain rather than yield to the Supreme Court’s power, shows that the Supreme Court is prepared to judicially review laws, despite expectations that it would not do so in the post-authoritarian period.Footnote 71 As the Supreme Court’s handling of the Pacitan cases shows, it is prepared to allow judges to assess whether some punishments are really just. Nevertheless, because judges in Indonesia’s trial courts rarely find out about such persuasive precedents and use them in their sentences, there is no systemic and long-term effect to prevent the harsh consequences for attempted migrant smuggling, as some or most judges will continue to apply the legislated punishments, which will put offenders behind bars for at least five years.