Introduction

Cognitive bias toward negative information has been linked to the development and exacerbation of mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression (Beck & Clark, Reference Beck and Clark1997; Mathews & MacLeod, Reference Mathews and MacLeod2005). This led to the development of cognitive bias modification (CBM), aimed at reducing cognitive bias to alleviate these conditions. Meta-analyses have shown the effectiveness of CBMs for attention and interpretation (ABM and CBM-I, respectively) (e.g. Fodor et al., Reference Fodor, Georgescu, Cuijpers, Szamoskozi, David, Furukawa and Cristea2020; Gober, Lazarov, & Bar-Haim, Reference Gober, Lazarov and Bar-Haim2021; Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Lissek, Bar-Haim, Britton, Fox, Leibenluft and Pine2010; Mogoaşe, David, & Koster, Reference Mogoaşe, David and Koster2014, but see Gober et al., Reference Gober, Lazarov and Bar-Haim2021, for a review). However, CBM for memory bias (CBM-M), targeting the encoding and retrieval of negative information, remains underexplored despite its clinical importance (Gotlib & Joormann, Reference Gotlib and Joormann2010).

Several pioneering studies have examined the effectiveness of CBM-M to enhance positive memories. Vrijsen, Hertel, and Becker (Reference Vrijsen, Hertel and Becker2016) showed that a single-session CBM-M, which facilitates the recall of positive words after a negative one, maintained a higher positive mood 1 week later compared to control groups (non-training and sham training) in unselected participants. CBM-M also resulted in mood improvement in ruminative individuals (Hertel, Maydon, Cottle, & Vrijsen, Reference Hertel, Maydon, Cottle and Vrijsen2017). A follow-up study found that CBM-M increased training-congruent positive word recall in depressive individuals; however, both groups showed mood improvement and reduced depressive symptoms with no transfer to positive autobiographical memory (AM) (Vrijsen et al., Reference Vrijsen, Dainer-Best, Witcraft, Papini, Hertel, Beevers and Smits2019). Following the protocol proposed by Vrijsen et al. (Reference Vrijsen, Dainer-Best, Witcraft, Papini, Hertel, Beevers and Smits2019), another study found an increase in positive word recall but no changes in depressive symptoms or emotional AM in individuals with mild depression (Atashipour, Momeni, Dolatshahi, & Mirnaseri, Reference Atashipour, Momeni, Dolatshahi and Mirnaseri2023).

Focusing on AM recall, Bovy et al. (Reference Bovy, Ikani, van de Kraats, Dresler, Tendolkar and Vrijsen2022) examined the effectiveness of 6-day CBM-M training to enhance positive memory in dysphoric individuals, compared with sham training for neutral memory and non-training. No group differences were observed, but CBM-M and sham training enhanced positive mood, increased positive-valence memory recall (including AM specificity), and reduced depressive symptoms. They suggested that sham training may have an unspecific effect, and the intervention duration may have been insufficient to reveal differences. Another study without a control group also showed that CBM-M induced positive AM specificity and improved mood repair in patients with major depressive disorder despite no change in depressive symptoms (Arditte Hall, De Raedt, Timpano, & Joormann, Reference Arditte Hall, De Raedt, Timpano and Joormann2018). Previous studies showing CBM-M-induced mood improvement facilitated negative word recall in controls (Hertel et al., Reference Hertel, Maydon, Cottle and Vrijsen2017; Vrijsen et al., Reference Vrijsen, Hertel and Becker2016), while those showing no effect did neutral word recall (Atashipour et al., Reference Atashipour, Momeni, Dolatshahi and Mirnaseri2023; Vrijsen et al., Reference Vrijsen, Dainer-Best, Witcraft, Papini, Hertel, Beevers and Smits2019). These findings highlight the need for longer CBM-M interventions to enhance positive AM using a control group focused on negative word recall to assess its impact in a more diverse sample.

Previous research has focused primarily on depression, where individuals with depression recall more negative than neutral/positive stimuli, especially when self-relevant (Duyser et al., Reference Duyser, Vrijsen, van Oort, Collard, Schene, Tendolkar and van Eijndhoven2022; Gerritsen et al., Reference Gerritsen, Rijpkema, van Oostrom, Buitelaar, Franke, Fernández and Tendolkar2012; Gotlib & Joormann, Reference Gotlib and Joormann2010; Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022). Depression is also linked to reduced AM specificity, particularly for positive memories (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Li, Xiao, Yang and Jiang2013; Ono, Devilly, & Shum, Reference Ono, Devilly and Shum2016; Van Vreeswijk & De Wilde, Reference Van Vreeswijk and De Wilde2004). Additionally, both depression and anxiety are associated with negative implicit memory bias (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022; Phillips, Hine, & Thorsteinsson, Reference Phillips, Hine and Thorsteinsson2010; Teachman et al., Reference Teachman, Clerkin, Cunningham, Dreyer-Oren and Werntz2019), which can occur transdiagnostically (Duyser et al., Reference Duyser, van Eijndhoven, Bergman, Collard, Schene, Tendolkar and Vrijsen2020) and is linked to amygdala function (Duyser et al., Reference Duyser, Vrijsen, van Oort, Collard, Schene, Tendolkar and van Eijndhoven2022). Consistently, we found that negative memory bias correlates with anxious and depressive traits, explained by amygdala functional connectivity (FC) with the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), including the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC), and the interaction between cortisol and norepinephrine metabolites (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022). We have also observed links between negative memory biases, amygdala FC with vmPFC/sgACC, and cortisol in independent samples (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Moriguchi, Hori, Kim and Tagaya2020, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Hori, Matsui, Moriguchi and Tagaya2025). Given the stress-reducing effects of CBM (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Lissek, Bar-Haim, Britton, Fox, Leibenluft and Pine2010; Hallion & Ruscio, Reference Hallion and Ruscio2011; Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Pile, Grant, Degli Esposti, Montgomery and Lau2018; Mogoaşe et al., Reference Mogoaşe, David and Koster2014), it may alter amygdala–vmPFC/sgACC FC and cortisol. Furthermore, examining the effects of anxiety and depression separately could reveal individual characteristics sensitive to CBM-M effects. However, no previous study has comprehensively explored the neurobiological actions and effectiveness of CBM-M.

This study thus investigated the effectiveness of CBM-M in enhancing positive AM recall through negative and positive word memorization over eight sessions in 1 month through a double-blind, randomized controlled trial (RCT) in vulnerable individuals exhibiting high (>1 SD) anxious/depressive personality traits, compared with sham training without the positive AM enhancement module. Individuals not on psychiatric treatment were included to avoid confounding effects from pharmacotherapy and neurocognitive deficits (Semkovska et al., Reference Semkovska, Quinlivan, O’Grady, Johnson, Collins, O’Connor and Gload2019). Outcome measures included anxiety and depressive traits and symptoms, explicit and implicit memory biases, AM specificity, and cortisol levels. Additionally, we explored the neurobiological effects of CBM-M with pre- and post-intervention functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans, focusing on amygdala FC. We also preliminarily explored individual personality trait profiles regarding anxiety and depression sensitive to CBM-M effects.

Methods

Participants

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and national ethical guidelines and was approved by the Kitasato University Medical Ethics Organization (C17-126). The protocol was preregistered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network database (No. 000029031) and was reported according to CONSORT guidelines. Using G*Power 3.1 software (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007), the sample size was calculated as n = 58 to detect a time×group interaction effect at α = 0.05 (f = 0.22, 1-β = 0.90, correlation among repeated measures 0.5), based on our previous RCT with the same design (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Komi, Sato, Moriguchi, Motomura, Maruo, Izawa, Kim, Hanakawa, Inoue and Tagaya2018). The effect size (f = 0.22) was determined from our previous study on anxiety/depressive traits and memory bias (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022) (see the Supplementary Material for additional details).

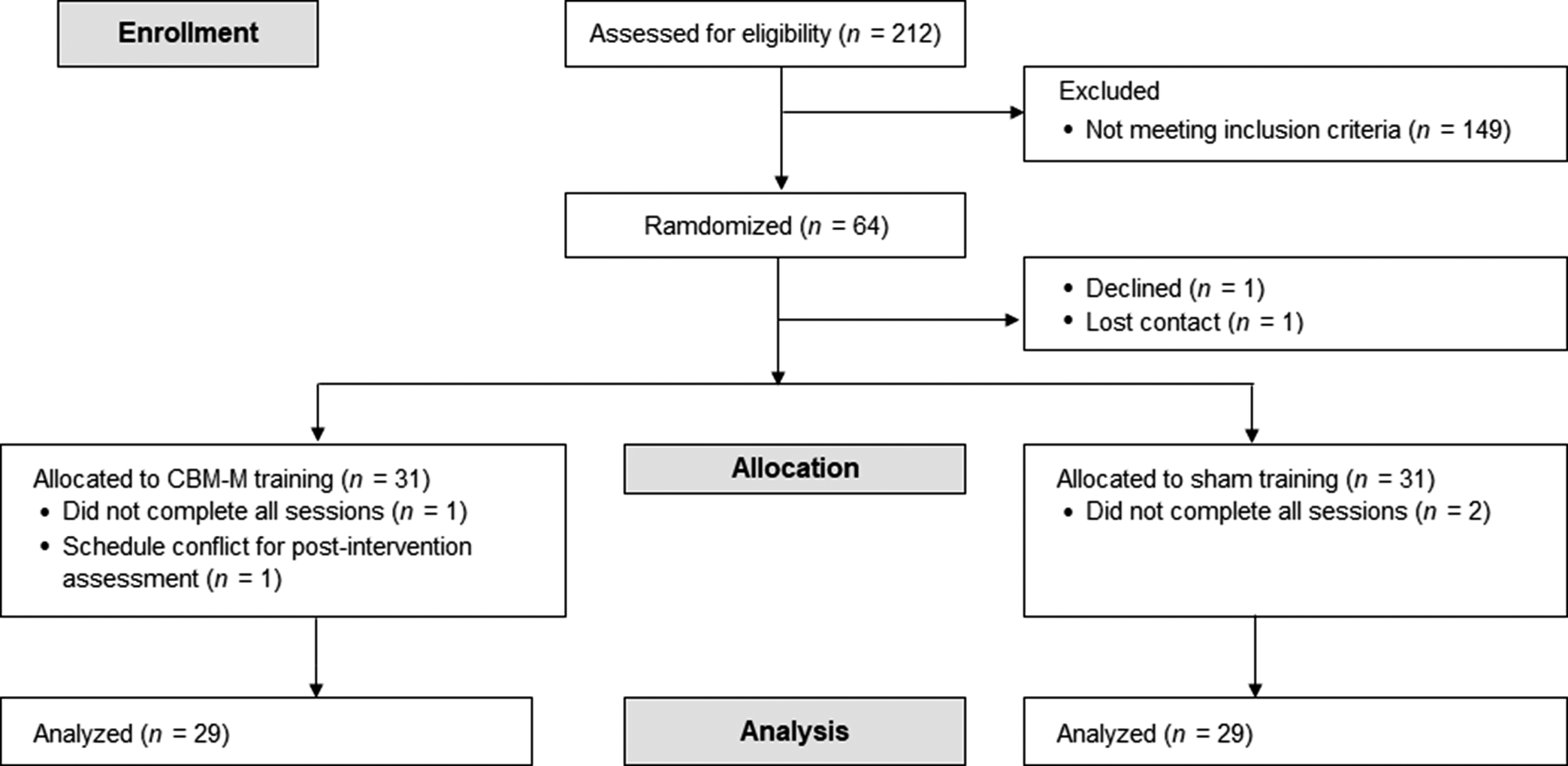

Inclusion criteria were: [1] Participants with ≥1 SD score on anxious/depressive personality traits of Neuroticism, assessed by the NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (Costa & McCrae, Reference Costa and McCrae1992), a major risk factor for depressive and anxiety disorders (Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010; Struijs et al., Reference Struijs, de Jong, Jeronimus, van der Does, Riese and Spinhoven2021); [2] Age 18–59 years; [3] No current Axis-I psychiatric disorders or substance abuse history, as defined by DSM-IV; [4] No major medical illnesses; [5] No regular intake of psychotropics, steroids, or opioids; [6] No metal or medical implants; [7] No history of brain injury or trauma with loss of consciousness >10 min; and [8] No excessive caffeine intake (>400 mg/day) (Temple et al., Reference Temple, Bernard, Lipshultz, Czachor, Westphal and Mestre2017). Japanese participants from Tokyo and surrounding areas were recruited via local magazines and websites between July 2020 and October 2022. Recruitment was ceased upon reaching the required sample size. Of 212 initially recruited, 64 met the inclusion criteria and provided written informed consent. Of these, one participant declined participation and another lost contact after the first visit. A total of 62 participants were randomly assigned (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram. One participant in CBM-M could not participate in the post-intervention assessment because of the funeral of a first-degree relative. Note: CBM-M, cognitive bias modification for memory.

The current sample was independent of our previous studies (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Moriguchi, Hori, Kim and Tagaya2020, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Moriguchi, Hori, Matsumoto and Tagaya2021, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022), except for one that shared 42.5% of the baseline sample (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Hori, Matsui, Moriguchi and Tagaya2025). No longitudinal data following the intervention have been reported.

Study procedures

This parallel-group trial used a 1:1 allocation ratio with a double-blind design. Participants were randomly assigned to either the CBM-M (n = 31) or Sham-training (n = 31) program within 2 weeks of the baseline visit (Figure 1). Randomization was stratified by age, sex, NEO anxiety, depressive trait scores, and baseline explicit and implicit memory bias scores. H.T. adaptively finalized the assignment to ensure a balance between both groups in terms of these baseline variables (see the Supplementary Material for additional details).

The programs were web-based. Participants completed the assigned program twice a week for 1 month (eight sessions) in a quiet space at home and at a time when they could concentrate. Completion was not recorded until each participant submitted the final response to ensure their engagement with the program. Participants received an email with the program’s URL, ID, and password from an email account accessible only to an administrator who was not involved in the study. The administrator monitored progress regularly. Two weeks after completing the sessions, participants underwent post-assessment, including MRI scans and saliva collection.

Primary outcomes were NEO anxiety and depressive personality traits. Secondary outcomes included Harm Avoidance (HA) subscales from the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) (Cloninger, Svrakic, & Przybeck, Reference Cloninger, Svrakic and Przybeck1993), psychological distress (including anxiety/depressive symptoms), explicit and implicit memory bias scores, AM specificity (including emotional valence), and cortisol levels. fMRI scans were conducted pre- and post-intervention to explore the action mechanisms of CBM-M.

CBM-M and sham-training programs

The CBM-M program was based on a word recall task for explicit memory bias (Friedman, Thayer, & Borkovec, Reference Friedman, Thayer and Borkovec2000) and a word completion task for implicit memory bias (Warrington & Weiskrantz, Reference Warrington and Weiskrantz1970). It was developed online using JavaScript (https://www.ecma-international.org/) and PHP Hypertext Preprocessor (https://www.php.net/).

As in previous CBM-M programs (Arditte Hall et al., Reference Arditte Hall, De Raedt, Timpano and Joormann2018; Hertel et al., Reference Hertel, Maydon, Cottle and Vrijsen2017; Vrijsen et al., Reference Vrijsen, Hertel and Becker2016), participants memorized a word list with 11 negative, 11 positive, and six neutral filler words. The same word list was used across all eight sessions, but the words were arranged randomly. Only the CBM-M group completed a module to vividly recall an event in response to a presented positive cue word (see Figure 2). Memory bias scores and mood ratings from each session were analyzed to track changes across the eight sessions, with results reported in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 2. CBM-M and sham-training programs. The CBM-M group was instructed to vividly recall a personal event that made them feel the positive word presented just before (e.g. recalling a time when they felt “competent”) with no such instruction for negative words. Sham training did not include this personal recall module. A total of 28 words were randomly presented in each session, with the first and last three words being neutral fillers to minimize primacy and recency effects. In each trial, participants first identified the color of a fixation (green or orange) to ensure focus. Subsequently, a word appeared on the screen for 8 s. Upon the disappearance of the word, participants rated its relevance to themselves on a 3-point scale (1: relevant, 2: not relevant, 3: neither). After the word presentation, participants recalled as many words as they could in a free-recall task. No time limit or prompts were provided for the recall. Participants then completed 11-word stems (one at a time) by entering the first word that came to mind. After the task, mood was rated using the Self-Assessment Manikin, on a 9-point scale from 1 (unhappy/uncomfortable) to 9 (happy/comfortable) (Bradley & Lang, Reference Bradley and Lang1994). Note: CBM-M, cognitive bias modification for memory.

Psychological assessment

Participants’ demographic information and neurocognitive functions were assessed using the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (Matsui, Kasai, & Nagasaki, Reference Matsui, Kasai and Nagasaki2010; Randolph, Reference Randolph1998). All outcome measures demonstrated sufficient reliability and validity. Detailed descriptions of each measure are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Anxiety and depressive personality traits

Anxiety and depressive traits were assessed using the full version of the NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, Reference Costa and McCrae1992; Shimonaka, Gondo, & Takayama, Reference Shimonaka, Gondo and Takayama1998). These traits were included in primary and secondary outcome analyses, with the latter examining the effects of baseline personality profiles. As mentioned earlier, the analysis of personality profiles was exploratory, as the study was not designed to specifically test a group×profile interaction. Participants were classified into three profiles: 1) anxiety-predominant (>1 SD on the anxiety trait), 2) depression-predominant (>1 SD on the depressive trait), and mixed (>1 SD on both traits). Additionally, the HA subscales of the TCI short version (Cloninger et al., Reference Cloninger, Svrakic and Przybeck1993; Kijima et al., Reference Kijima, Sato, Takeuchi, Ono, Genichiro and Kitamura1996) were assessed, which include anticipatory worry, fear of uncertainty, shyness with strangers, and fatigability and asthenia (Cloninger, Reference Cloninger2000; Cloninger et al., Reference Cloninger, Svrakic and Przybeck1993).

Psychological distress, including anxiety and depressive symptoms

The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL) (Derogatis et al., Reference Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth and Covi1974; Nakano, Reference Nakano2016) was used to assess five symptom dimensions experienced in the past week: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, and depression.

Psychosocial stressor

Stressful life events were assessed using the Life Experiences Survey (Iwamitsu et al., Reference Iwamitsu, Yasuda, Kamiya, Wada, Nakajima, Ando and Takemura2008; Sarason, Johnson, & Siegel, Reference Sarason, Johnson and Siegel1978). The presence or absence of significant stressor-related negative life changes during the intervention period was considered in cortisol analyses sensitive to these effects.

Behavioral assessment

Experimental tasks were constructed using E-prime version 2.0 for Professionals (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). As the explicit and implicit memory bias tasks followed the same procedures as the training, further details are provided in the Supplementary Material and in our previous study (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022). Different word lists were used in the pre- and post-intervention assessments for the explicit memory bias task and the AM test; however, 27.3% of the words (four negative and two positive) used in the training were included in the memory bias task post-intervention.

Explicit memory bias

Explicit memory bias scores were calculated as follows: negative recall ratio (number of self-relevant negative words recalled/ total number of recalled words [22 at maximum] × 100) - positive recall ratio (number of self-relevant positive words recalled/ total number of recalled words×100) (Duyser et al., Reference Duyser, Vrijsen, van Oort, Collard, Schene, Tendolkar and van Eijndhoven2022; Gerritsen et al., Reference Gerritsen, Rijpkema, van Oostrom, Buitelaar, Franke, Fernández and Tendolkar2012; Gotlib et al., Reference Gotlib, Kasch, Traill, Joormann, Arnow and Johnson2004; Vrijsen et al., Reference Vrijsen, van Amen, Koekkoek, van Oostrom, Schene and Tendolkar2017). Positive values indicate greater negative memory bias.

Implicit memory bias

Implicit memory bias was calculated as below: (number of negative words/total number of completed words×100) - the positive word ratio (the number of positive words/total number of completed words×100) (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022). Positive values indicate greater negative memory bias.

AM

The AM test (Williams & Broadbent, Reference Williams and Broadbent1986) was administered in a self-written format with minimal instructions (Debeer, Hermans, & Raes, Reference Debeer, Hermans and Raes2009). The administration and scoring procedures are detailed in the Supplementary Material and in our previous study (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Moriguchi, Hori, Matsumoto and Tagaya2021). The specificity of recalled memories, defined as an event that occurred in a specific place and concluded within 1 day, was evaluated by two independent raters and calculated as: (number of specific memories/total valid responses [12 at maximum] × 100) (Williams & Broadbent, Reference Williams and Broadbent1986). Valence scores were similarly calculated using the number of specific memories for each valence. We analyzed each valence score separately, as the AMT does not determine specificity scores by subtracting across valence types (Williams & Broadbent, Reference Williams and Broadbent1986), unlike other memory bias measures (Everaert et al., Reference Everaert, Vrijsen, Martin-Willett, van de Kraats and Joormann2022). A higher score indicates greater AM specificity.

Physiological assay of cortisol

Given the relevance of cortisol to stress (Wesarg-Menzel, Marheinecke, Staaks, & Engert, Reference Wesarg-Menzel, Marheinecke, Staaks and Engert2024), we measured cortisol levels from saliva collected at five time points across two consecutive weekdays: upon awakening (T1), 30 min after awakening (T2), around noon (11:30–12:30 h) (T3), late afternoon (17:30–18:30 h) (T4), and at bedtime (T5). Saliva collection occurred during the week following the pre- and post-intervention assessments. The procedures are detailed in our previous studies (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Hori, Matsui, Moriguchi and Tagaya2025). Participants collected saliva in microtubes with passive drool at home. They recorded the exact collection time, sleep duration, and perceived stress on a customized web-entry form. Female participants were asked to report their menstrual cycle (see Supplementary Material for scoring details). Participants were instructed to avoid alcohol on the collection days and the night prior and to refrain from eating or drinking (except water), exercising, brushing their teeth, showering, or bathing 1 hour before each collection time point.

For the cortisol assay, slowly thawed samples were centrifuged (3000 rpm, G-force = 1710) for 10 min. Cortisol concentration was measured using an enzyme immunoassay (EIA Kit, Salimetrics LLC, USA). Inter- and intra-assay variations were below 11% and 7%, respectively.

Cortisol levels were indexed at each time point, and the area under the curve with respect to ground was calculated for total cortisol output (Pruessner, Kirschbaum, Meinlschmid, & Hellhammer, Reference Pruessner, Kirschbaum, Meinlschmid and Hellhammer2003). Cortisol levels were averaged across the two collection days. Indices that did not follow a normal distribution were square-root transformed.

Acquisition and preprocessing of fMRI data

As in previous studies (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Moriguchi, Hori, Kim and Tagaya2020, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Moriguchi, Hori, Matsumoto and Tagaya2021, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022), resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) was acquired using a 32-channel phased-array head coil on a 3.0 T scanner (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare, USA). Preprocessing and FC analysis were performed using the CONN Functional Connectivity Toolbox version 21a (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/conn) with SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12) operated on MATLAB 2022b (https://mathworks.com/products/matlab.html). The default band-pass filter for rs-fMRI data was applied, with a frequency range of 0.008–0.09 Hz. Scanning parameters and preprocessing details are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Data analyses

Primary outcome

As a planned analysis, we examined changes in NEO anxiety and depressive traits using a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (rANOVA), with the intervention group (CBM-M vs. Sham training) as the between-subject factor and time (pre- vs. post-intervention) as the within-subject factor.

Secondary outcome

HA subscales, psychological distress, memory bias, and AM specificity

We conducted a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) for the post-intervention HA subscales, HSCL symptoms, explicit and implicit memory bias scores, and AM specificity scores (including valence) as dependent variables, with group and baseline personality profiles as between-subject factors, controlling for baseline scores (O’Connell et al., Reference O’Connell, Dai, Jiang, Speiser, Ward, Wei and Gebregziabher2017). We performed MANCOVA to assess the effectiveness of intercorrelated outcomes instead of the repeated measures model, which can show decreased detection power due to increased error variances by including time and interactions with multiple outcomes on different scales (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2017). As mentioned above, we analyzed baseline personality profiles to explore individual characteristics that were sensitive to CBM-M effects. Considering the small sample size in the analyzed groups, we used Pillai’s Trace, which is robust to the heteroscedasticity in covariance matrices (Olson, Reference Olson1974; Tabachnick & Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell2019).

Cortisol levels

In participants without hormonal disease or hormonal therapy, MANCOVA was conducted for total cortisol output and cortisol levels at each time point as dependent variables, with the group and the stressor (i.e. the presence/absence of negative life changes during the intervention period) as between-subject factors, controlling for pre-intervention values.

CBM-M-related changes in amygdala FC

The amygdala was anatomically defined using the FSL Harvard-Oxford atlas (http://www.cma.mgh.harvard.edu/fslatlas.html) as the seed region. While our primary focus was on the right amygdala, which has consistently been implicated in memory bias (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Moriguchi, Hori, Kim and Tagaya2020, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Hori, Matsui, Moriguchi and Tagaya2025), CBM effects were explored bilaterally. As the FSL atlas does not dissect the prefrontal cortex (PFC), we used the sgACC, vmPFC, rectus, and medial and anterior orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) from the Automated Anatomical Labeling brain atlas version 3.0 (Rolls et al., Reference Rolls, Huang, Lin, Feng and Joliot2020) (Figure 3d). We combined the bilateral anatomical masks of these regions into a single mask and used for small-volume correction (SVC) analysis.

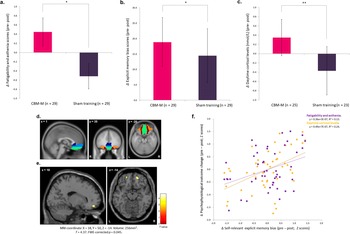

Figure 3. CBM-M effects on fatigability, explicit memory bias, and daytime cortisol levels, and amygdala connectivity. (a) Fatigability and asthenia score. (b) Explicit memory bias score. (c) Daytime cortisol levels (Time 3). *p < .05, **p < .01. (d) The volumes of interest: subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (dark blue), ventromedial prefrontal cortex (light blue), rectus (light green), and medial and anterior orbitofrontal cortex (brown and orange, respectively). (e) Increased amygdala functional connectivity with amOFC from pre- to post-intervention in the CBM-M group compared with the sham-training group. (f) Scatterplot showing correlations of explicit memory bias with fatigability scores and daytime cortisol levels. Z scores of pre-post changes are displayed (larger values indicate a greater decrease from pre- to post-intervention). The sample size of cortisol-related analyses in (c) and (f) was 48. The effects of baseline scores, age, sex, RBANS total index score, handedness, LES balanced impact scores during the intervention period, invalid word-recall cases, sleep duration, perceived stress, and menstrual status during saliva collection were controlled for. Note: CBM-M, cognitive bias modification for memory; amOFC, anteromedial orbitofrontal cortex; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; LES, Life Experiences Survey.

We performed a two-way rANOVA for amygdala FC, with group as the between-subject factor and time as the within-subject factor. Given that relatively small effect sizes have been observed in social and affective neuroscience (Lieberman & Cunningham, Reference Lieberman and Cunningham2009), we employed SVC analysis for the combined mask, applying a family-wise error (FWE)-corrected threshold of p < .05 at the peak level. For other regions, the threshold was set at an FWE-corrected p < .05 throughout the brain. For reference, the Supplementary Material reports the results of amygdala FC with the hippocampus.

Correlations between outcome changes

For the outcomes that showed a significant CBM-related change from the pre- to post-intervention time points, their correlations were explored using the difference (i.e. pre-post) scores, controlling for baseline scores. We did not use multiple testing corrections given the exploratory nature of the analysis; however, we reported the results with the corrections applied as well. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 27.0J (IBM, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), with a statistical threshold p < .05 (two-sided) unless otherwise stated. Additional details of the data analyses are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Results

Participant characteristics

Two participants dropped out from each group, resulting in data analysis for 58 participants: CBM-M (n = 29) and sham training (n = 29) (Figure 1). The color-identification ratio during the encoding phase was 98.7 ± 0.4%, indicating that the participants maintained proper focus on the program. No participants reported potential harm from the programs. Table 1 describes the participants’ characteristics. There were no significant baseline differences in demographics or outcome measures between groups (all p ≥ .20) (Table 2).

Table 1. Participant baseline characteristics in CBM-M and sham-training groups

Note: χ2 test was applied to sex and personality trait profiles. All other test statistics were derived from t-tests with 56 degrees of freedom. Absolute t values are shown.

CBM-M, cognitive bias modification for memory; SD, standard deviation; EHI, Edinburgh Handedness Inventory; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status.

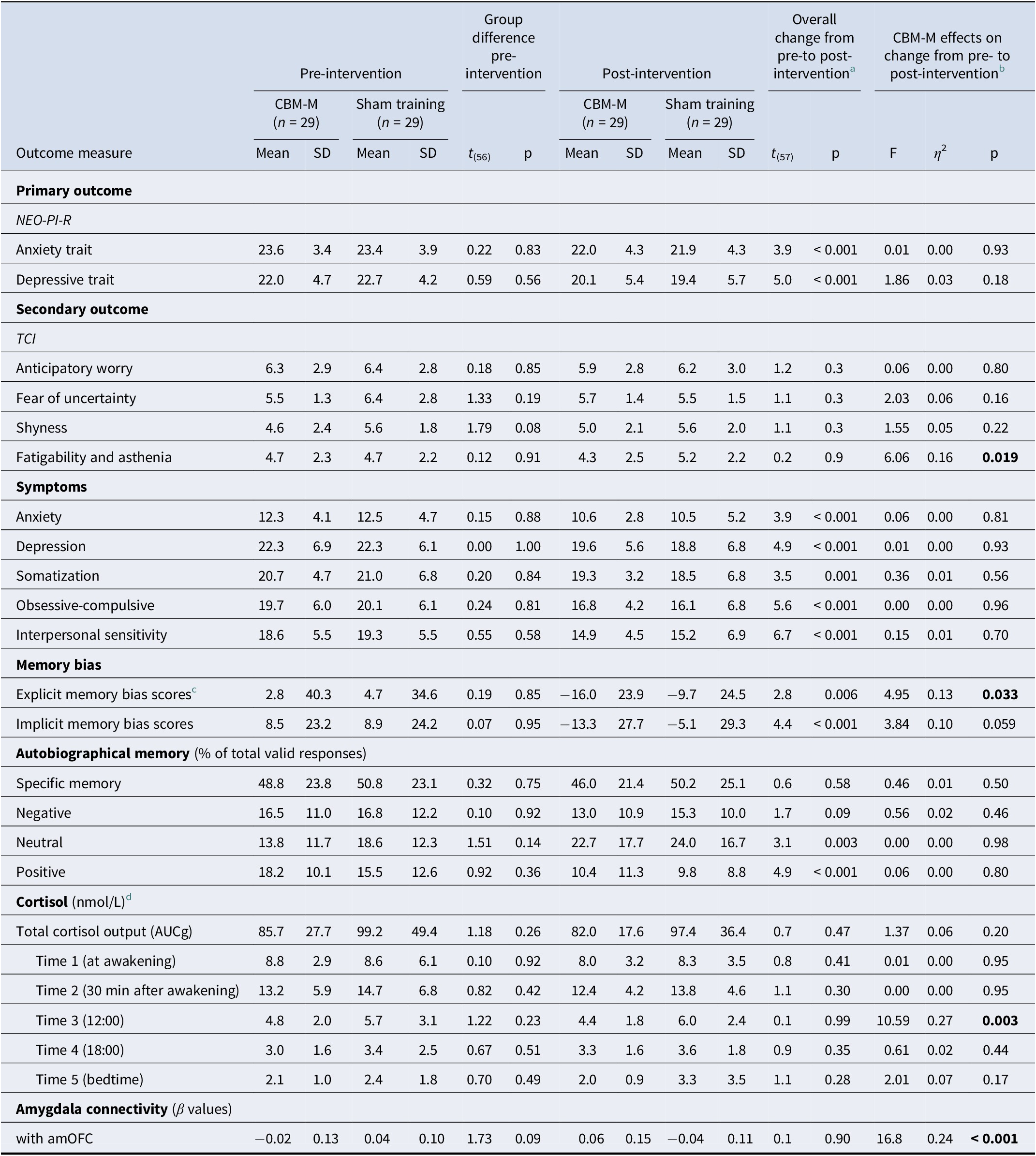

Table 2. Pre- and post-intervention outcome measures in CBM-M and sham-training groups

Note: Effect size: η 2 ≥ 0.01 (small), ≥ 0.06 (medium), ≥ 0.14 (large).

CBM-memory, cognitive bias modification for memory; SD, standard deviation; NEO-PI-R, Revised NEO Personality Inventory; HSCL, Hopkins Symptoms Checklist; AUCg, area under the curve with respect to ground; TCI, Temperament, and Character Inventory; HA, Harm Avoidance; amOFC, anteromedial orbitofrontal cortex.

a The overall changes from pre- to post-intervention across groups were based on the results of the paired t-test. For cortisol indices, the degrees of freedom were 47.

b Results of rANOVA and MANCOVA are reported for primary and secondary outcomes.

c Based on self-relevant words from previous studies (e.g. Duyser et al., 2022; Gerritsen et al., Reference Gerritsen, Rijpkema, van Oostrom, Buitelaar, Franke, Fernández and Tendolkar2012; Gotlib et al., Reference Gotlib, Kasch, Traill, Joormann, Arnow and Johnson2004; Vrijsen et al., Reference Vrijsen, van Amen, Koekkoek, van Oostrom, Schene and Tendolkar2017). Self-relevance rating scores did not differ significantly between the CBM-M group (0.13 ± 0.30) and the sham-training group (0.18 ± 0.27) at baseline: t(56) = −0.66, p = 0.51. Note: for this statistical comparison and interpretation, the original coding values for self-relevance (1: relevant, 2: not relevant, 3: neither) were recoded as follows: 1: relevant; 0: neither; and −1: not relevant.

d A total of 48 participants were included in the cortisol analysis (25 in the CBM-M group and 23 in the sham-training group). Ten participants were excluded due to the following reasons: Graves’ disease (n = 1), menopause (n = 4), cessation of menstruation due to hormone intake (n = 1), pre-intervention cortisol levels below the detection limit on both saliva collection days (n = 2), delivery at room temperature (n = 1), and non-submission of post-intervention saliva samples (n = 1). None of the 48 participants were using contraceptives or working shift hours. The degree of freedom for the independent t-test for baseline differences was 46. Absolute t values are shown.

Regarding behavioral data, invalid cases (see Supplementary Table S1) were controlled for as a binary variable in related analyses to prevent sample attrition. For cortisol measures, 10 participants were excluded due to conditions affecting cortisol secretion or invalid saliva samples (see notes in Table 2), leaving 48 participants. The CBM-M (n = 25) and sham-training (n = 23) groups did not differ in demographics or any outcome measures (Supplementary Table S2). Cortisol measures were square-root transformed to address non-normality (Supplementary Material).

Changes in mood and bias across sessions are reported in the Supplementary Material and in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

CBM-M effect on primary outcome

Two-way rANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time for anxiety and depressive traits: F 1,56 = 14.97, p < .001 and F 1,56 = 25.22, p < .001, respectively (Table 2; Supplementary Figure S1a,b). However, the time×group interaction was not significant: F 1,56 = 0.01, p = .93 and F 1,56 = 1.86, p = .18, indicating that both groups showed a reduction in anxiety and depressive traits from pre- to post-intervention.

CBM-M effect on secondary outcomes

HA subscales, psychological distress, memory bias, and AM specificity

MANCOVA showed significant effects for the intervention group (F 15,19 = 2.91, η 2 = 0.70, p = .015) and the group×personality profile interaction (F 30,40 = 2.39, η 2 = 0.64, p = .005) (Supplementary Figure S2a), despite the nonsignificant main effect of profile (F 30,40 = 1.02, η 2 = 0.29, p = .48). Follow-up tests revealed reductions in fatigability (F 1,57 = 6.06, η 2 = 0.16, p = .019; Figure 3a) and explicit memory bias (F 1,57 = 4.95, η 2 = 0.13, p = .033; Figure 3b) in the CBM-M group. The implicit memory bias also decreased, but this difference was not significant (F 1,57 = 3.84, η 2 = 0.10, p = .059) (Table 2).

Regarding the group×profile interaction, which was parsed into a single main effect, a significant group difference was found in positive specific memory scores: F 1,57 = 8.05, η 2 = 0.33, p = .001. Post hoc analysis revealed that anxiety-predominant individuals in the CBM-M group maintained higher positive specific memory scores compared to the sham-training group (Mean ± SD: 18.6 ± 10.8 > 3.66 ± 5.1, p = .007, respectively), while depression-predominant individuals showed a reduction (Mean ± SD: 5.0 ± 7.5 < 13.2 ± 7.8, p = .017). No differences were observed in mixed-type individuals (p = .99) (Supplementary Figure S2b), implying the beneficial effects of CBM-M on anxiety-predominant, but not depression-predominant, individuals in positive AM specificity.

Cortisol levels

MANCOVA for cortisol levels revealed a significant main effect of the intervention group (F 6,23 = 2.81, η 2 = 0.42, p = .033), despite the nonsignificant effects for the stressor (F 6,23 = 1.11, p = .39) and group×stressor interaction (F 6,23 = 0.58, p = .74). A follow-up univariate test showed reduced daytime cortisol levels at noon (T3) (F 1,28 = 10.59, η 2 = 0.27, p = .003; Table 2; Figure 3c) in the CBM-M group compared to the sham-training group. No significant differences were found for total cortisol output or cortisol levels at other time points (all p > .17).

CBM-M-related changes in amygdala FC

A two-way rANOVA revealed significantly increased right amygdala FC with the anteromedial OFC (amOFC) in the CBM-M group compared to the sham-training group from pre- to post-intervention (MNI coordinate: 18, 50, −14, T = 4.37, FWE-corrected p = .045, 256 mm3; Figure 3e). The right amygdala FC with the left amOFC also showed an increasing trend (MNI: −20, 52, −14, FWE-corrected p = .094, T = 4.10, 56 mm3). No significant interaction effects were found in other brain regions, including the hippocampus, with either side of the amygdala (Supplementary Table S5).

Relationships between changed outcome variables

Exploratory correlation analysis of the pre-post difference scores for fatigability, explicit memory bias, daytime (T3) cortisol levels, and amygdala–amOFC FC revealed significant correlations between explicit memory bias and fatigability (r = 0.37, p = .011) and between explicit memory bias and daytime cortisol levels (r = 0.49, p < .001). These scores still passed the threshold for significance after Bonferroni correction (i.e. p < .013; Figure 3f and Supplementary Table S6). No significant correlations were observed between the amygdala–amOFC FC and fatigability (r = −0.03, p = 0.85); memory bias (r = 0.10, p = 0.49); or cortisol levels (r = 0.19, p = 0.21) (Supplementary Table S6).

Discussion

This study found a reduction in anxiety and depressive traits from pre- to post-intervention in both groups. However, CBM-M specifically reduced fatigability, explicit memory bias, and daytime cortisol levels compared with sham training. Baseline personality profiles predicted differential responses to CBM-M in positive AM specificity. CBM-M also increased amygdala–amOFC connectivity compared with sham training. The improvement in explicit memory bias was correlated with fatigability and cortisol levels.

Contrary to expectations, anxiety and depressive traits decreased in both CBM-M and sham-training groups. A similar decrease was observed in most secondary outcomes, except for the HA subscales and cortisol levels, regardless of group (Table 2). As shown in the Supplementary Material and Supplementary Table S3, both groups shifted from negative to positive mood by the final session. Positive words were generally recalled more than negative words across groups, although the CBM-M group recalled more positive words than the sham-training group. These results align with previous studies showing increased positive mood and reduced depressive symptoms in CBM-M and sham-training groups (Bovy et al., Reference Bovy, Ikani, van de Kraats, Dresler, Tendolkar and Vrijsen2022; Vrijsen et al., Reference Vrijsen, Dainer-Best, Witcraft, Papini, Hertel, Beevers and Smits2019), suggesting a potential effect of the sham training. Both groups memorized negative and positive words. Given the increase in positive, but not negative, word recall across groups, repetitive exposure to positive words may have helped the sham-training group develop a preference for them, leading to a general reduction in outcome variables.

In contrast, CBM-M significantly decreased fatigability scores, explicit negative memory bias, and daytime cortisol levels compared with sham training, with generally large effect sizes. Specifically, in the CBM-M group but not in the sham-training group, negative memory bias scores decreased with successive sessions, and this reduction correlated significantly with decreased explicit memory bias scores after the intervention (Supplementary Table S4), indicating that CBM-M ameliorated self-relevant negative memory bias. Consistent with these findings, our previous RCT observed improvements in fatigability after ABM (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Komi, Sato, Moriguchi, Motomura, Maruo, Izawa, Kim, Hanakawa, Inoue and Tagaya2018), highlighting the sensitivity of this scale to CBM effects. Fatigability scores reflect a tendency to tire easily, requiring additional rest or slower recovery from stress, fatigue, or illness (Cloninger, Reference Cloninger2000; Cloninger et al., Reference Cloninger, Svrakic and Przybeck1993), thus potentially indicating high stress vulnerability. Importantly, the reduction in memory bias was associated with decreases in both daytime cortisol levels and fatigability scores. Elevated daytime cortisol levels have been linked to a family history of mood disorders (Ellenbogen et al., Reference Ellenbogen, Hodgins, Walker, Couture and Adam2006; Ostiguy, Ellenbogen, Walker, Walker, & Hodgins, Ostiguy et al., Reference Ostiguy, Ellenbogen, Walker, Walker and Hodgins2011) and adverse childhood experiences (Franz et al., Reference Franz, O–Brien, Hauger, Mendoza, Panizzon, Prom-Wormley and Kremen2011), both of which increase the risk of developing mood disorders (Scott, Smith, & Ellis, Reference Scott, Smith and Ellis2010). Higher daytime cortisol levels also predict the onset of mood disorders in vulnerable individuals (Ellenbogen, Hodgins, Linnen, & Ostiguy, Reference Ellenbogen, Hodgins, Linnen and Ostiguy2011). These findings suggest that CBM-M may have a preventive effect on stress-related disorders by mitigating stress vulnerability.

We expected an increase in positive AM specificity, given that the current CBM-M was designed to enhance the vivid recall of positive AM. However, positive AM specificity generally decreased, while neutral AM specificity increased from pre- to post-intervention across the groups despite no change in the overall specific memory score (Table 2). Previous studies have shown that elevated cortisol levels specifically impair neutral AM specificity, both following hydrocortisone administration (Wingenfeld et al., Reference Wingenfeld, Driessen, Schlosser, Terfehr, Carvalho Fernando and Wolf2013) and psychosocial stress (Tollenaar, Elzinga, Spinhoven, & Everaerd, Reference Tollenaar, Elzinga, Spinhoven and Everaerd2009). A general reduction in psychological stress (i.e. distress) might have facilitated AM recall from a more objective, neutral perspective. However, this possibility warrants further investigation.

Further, CBM-M, compared with sham training, maintained positive AM specificity in the anxiety-predominant type while decreasing it in the depression-predominant type. The mixed type generally maintained positive AM specificity, with no significant group difference observed. These profile-related findings should be interpreted cautiously given their preliminary nature; however, it should be noted that low positive AM specificity is commonly associated with depression (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Li, Xiao, Yang and Jiang2013; Ono et al., Reference Ono, Devilly and Shum2016). Depressive individuals may fail to recall positive memories in response to positive cues. This does not contradict clinical observations that depressive individuals tend to remember negative, but not positive, aspects of experienced events. Indeed, similar interventional techniques, such as using positive data logs to record positive evidence against negative self-schemas, are the most challenging to implement and require carefully guided support by clinicians because depressive individuals can easily discount and distort positive aspects of experienced events (Padesky, Reference Padesky1994). In addition, as the encoding of positive information is disrupted in depression (Dillon & Pizzagalli, Reference Dillon and Pizzagalli2018), individuals with depression may struggle to construct positive memories during retrieval (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Hori, Matsui, Moriguchi and Tagaya2025). Therefore, although these findings require further investigation, CBM-M, which enhances positive AM recall, should be applied cautiously in depressive individuals without professional support, particularly in those who have persistent negative self-schemas not rooted in anxiety. For such individuals, enhanced encoding of positive stimuli without deep self-engagement might be beneficial; however, this possibility requires thorough investigation with larger samples.

The amygdala plays a critical role in emotional memory formation (Dillon & Pizzagalli, Reference Dillon and Pizzagalli2018; LaBar & Cabeza, Reference LaBar and Cabeza2006) and negative memory bias (Duyser et al., Reference Duyser, Vrijsen, van Oort, Collard, Schene, Tendolkar and van Eijndhoven2022). Compared with sham training, CBM-M increased right amygdala FC with the amPFC from pre- to post-intervention. This is consistent with previous findings in which we observed right amygdala FC with the vmPFC and sgACC in different memory bias types (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Moriguchi, Hori, Kim and Tagaya2020, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022, Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Hori, Matsui, Moriguchi and Tagaya2025). The vmPFC is involved in reward processing, decision-making, emotion regulation, and social cognition (Hiser & Koenigs, Reference Hiser and Koenigs2018). The OFC generally processes rewards; however, its medial part specifically processes social reward receipt rather than its reward anticipation (Diekhof, Kaps, Falkai, & Gruber, Reference Diekhof, Kaps, Falkai and Gruber2012; Martins et al., Reference Martins, Rademacher, Gabay, Taylor, Richey, Smith and Paloyelis2021; Solomonov et al., Reference Solomonov, Victoria, Lyons, Phan, Alexopoulos, Gunning and Flückiger2023). Additionally, AM retrieval activates the medial PFC along with the hippocampus (Shepardson, Dahlgren, & Hamann, Reference Shepardson, Dahlgren and Hamann2023) but engages the OFC and amygdala for the successful encoding and retrieval of emotional episodic memory (Dahlgren, Ferris, & Hamann, Reference Dahlgren, Ferris and Hamann2020). Patients with depression and lower positive AM specificity show stronger amygdala FC with the amPFC during positive AM retrieval, suggesting greater effortful engagement of these regions (Young, Siegle, Bodurka, & Drevets, Reference Young, Siegle, Bodurka and Drevets2016). These findings emphasize the importance of neural interactions between the amygdala and medial PFC, including the amOFC, in positive AM recall, potentially related to social reward receipt. However, the observed FC changes did not correlate with changes in outcome variables. Although the enhanced amygdala–amOFC FC presumably reflected a positive AM increase, several other pathways might have contributed to reductions in these stress-related markers. The neurobiological mechanisms underlying the CBM-M’s stress-reducing effect require further comprehensive investigation in future large-scale research.

This study had limitations that merit consideration. First, the sample size was small. We calculated the sample size based on the ‘as in GPower 3.0’ option in the G*Power software, assuming the correlation among repeated measures (i.e. pre- and post-outcome scores) to be 0.5, following our previous RCT (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Komi, Sato, Moriguchi, Motomura, Maruo, Izawa, Kim, Hanakawa, Inoue and Tagaya2018). Although practical and usable in RCTs (Arad et al., Reference Arad, Azriel, Pine, Lazarov, Sol, Weiser and Bar-Haim2023), this method was not as standard as Cohen’s recommended method, which robustly detects an effect of any designated magnitude with no assumption of correlation among repeated measures. In light of this, the current sample size was not sufficient for detecting small or medium effect sizes in the analyses of this study. Additionally, the effect size for sample size calculation (f = 0.22) was obtained from the correlation between memory bias (i.e. measured using the word recall and completion tasks employed in the current CBM-M) and anxiety/depressive traits (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Izawa, Okamura, Mihara, Marusak and Tagaya2022), due to the limited research on CBM-M. Despite the comparability between the effect sizes of cognitive bias and its modification on anxiety-/depression-related measures (e.g. Bar-Haim et al., Reference Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2007; Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Lissek, Bar-Haim, Britton, Fox, Leibenluft and Pine2010; Linetzky, Pergamin-Hight, Pine, & Bar-Haim, Reference Linetzky, Pergamin-Hight, Pine and Bar-Haim2015; Mogoaşe et al., Reference Mogoaşe, David and Koster2014), applying this effect size to the assumed effect size for a repeated measures design was not a straightforward approach. These points require consideration, and the results of this study should thus be interpreted carefully. Second, the hypothesis on changes in the amygdala FC with the vmPFC/sgACC was not pre-registered. We previously observed that FC between the brain regions associated with attentional bias was altered by ABM (Hakamata et al., Reference Hakamata, Sato, Komi, Moriguchi, Izawa, Murayama, Hanakawa, Inoue and Tagaya2016; Reference Hakamata, Mizukami, Komi, Sato, Moriguchi, Motomura, Maruo, Izawa, Kim, Hanakawa, Inoue and Tagaya2018), and this observation led us to expect that the amygdala–vmPFC/sgACC FC associated with memory bias could be altered by CBM-M. However, the hypothesis setting and SVC application of the vmPFC/sgACC should have been pre-registered, and the obtained results should be interpreted with great caution. Third, 27% of the words used in the training overlapped with those in the post-intervention experiment, including four negative and two positive words. Repetitive exposure to these words could influence word recall performance post-intervention. However, this effect is likely negligible, as negative memory bias decreased following training despite the larger number of negative words, which could have otherwise increased negative bias. Additionally, this study did not include a waiting list control group. Both groups showed reduced anxiety and depressive traits, and participants’ expectations may have influenced the results. However, CBM-M specifically improved several outcomes, including cortisol, an objective marker. Even with participants’ expectations, a key component of placebo effects (Huneke et al., Reference Huneke, Fusetto Veronesi, Garner, Baldwin and Cortese2025), it was unlikely to specifically affect the outcome differences observed in this study. Finally, although we used Pillai’s Trace, which is robust to the heteroscedasticity of covariance matrices (Olson, Reference Olson1974; Tabachnick & Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell2019), examining personality profile effects was preliminary and would have required a larger sample, as mentioned above. Future research with a larger sample should clearly identify individuals who benefit most from CBM-M.

Conclusion

CBM-M, which enhances positive AM recall through negative and positive word memorization, and sham training, which involves memorizing negative and neutral words without the positive AM recall module, both reduced anxiety and depressive traits from pre- to post-intervention. However, compared with sham training, CBM-M specifically mitigated stress vulnerability, reduced explicit memory bias (i.e. the tendency to preferentially recall self-relevant negative information), and lowered daytime cortisol levels. The magnitude of improvement in memory bias correlated with stress vulnerability and cortisol levels. Additionally, CBM-M increased amygdala FC with the amOFC, a region involved in social reward-associated AM retrieval. These findings provide the first evidence of its effectiveness in reducing stress and its underlying neurobiological mechanisms. CBM-M may help prevent the future development of anxiety and depressive symptoms in individuals at high risk through its stress-reducing effects. Future research should explore the specific individuals who benefit most from CBM-M and the mechanisms involved.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725102535.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the study participants; Ms. Yasuko Omura for her assistance with project office administration; Ms. Fuyuko Yoshida and Ms. Noriko Fukuzato for cortisol level assays; and Mr. Masato Suzuki, Mr. Takahiro Mizoguchi, Mr. Kanta Okuzumi, Ms. Ayaka Ichikawa, Ms. Miyu Onoue, Ms. Yuri Nohara, Ms. Momoka Haginoya, and Ms. Sakura Wada for their data entry and research assistance.

Funding statement

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. 18H01094 to Y.H.) from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science, a research grant from the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to Y.H.), and research grants from the Multilayered Stress Diseases (JPMXP1323015483), Science Tokyo (to H.H.). The funding sources did not influence any aspect of the work, including design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing, or submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.