The resolution of The Kurdish Question, which is considered to date back to Ottoman times regarding its historical and cultural roots, has constantly been postponed by the governments of the Turkish Republic through means like denial, intolerance, marginalization, and assimilation (Yıldız Reference Yıldız2012, 151–152). Turkey’s EU membership application has provided the Kurdish movement with ‘new sets of opportunity structures’ (Watts Reference Watts2006, 131). In the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the EU Commission required countries to meet the Copenhagen criteria for EU membership, the rights of the Kurdish people gained more importance – in other words, the EU accession negotiations led to discussions about human and minority rights, including discussions concerning the democratization of Turkey and the rights of the Kurdish people. The Kurds viewed the EU project as significant because it acted as an external and transformative power with which Turkey could implement reforms that would lead to democratization and the acknowledgment of Kurdish identity, as well as their cultural and political rights. The Justice and Development Party (AKP) government, which had continued unabated with the previous coalition government’s democratization package, placed great importance on EU negotiations to change its political Islamist image when it came to power in 2002. However, after 2007, when it was elected for the second time, it began the process of de-Europeanization and did not prioritize EU relations.

It would not be wrong to claim that issues such as the democratization of Turkey and the protection of human and minority rights issues in line with the Copenhagen criteria have been replaced by a more topical agenda since 2015 that used to occupy an important place in Turkey-EU relations – that agenda being Turkey’s prevention of Syrian refugees’ entry into Europe. The ‘differentiated integration’ model has been revisited in the EU as the Union has struggled with emerging disintegration dynamics resulting from recent problems such as Brexit, the Eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis, and terrorist attacks (Özer Reference Özer2020, 436). In place of full EU membership, this ‘differentiated integration’ model has also been proposed for Turkey, whose accession negotiations are technically frozen. During the accession talks, and especially in the EU’s progress reports, improving the rights of the Kurds was always on the agenda. Under the influence and pressure of the EU Commission, the Kurdish issue was considered an important part of the rights and freedoms in relations between Turkey and the EU. However, after the freezing of negotiations (not a single negotiation chapter has been opened since 2016) and the end of the peace process, the Kurdish issue was linked to terror (the PKK and PYD) and was considered a serious national security issue in Turkey.

During the 1990s it was expected that a supranational project like European integration would weaken the sovereignty of nation-states while minimalizing independentist demands. Especially ‘positive developments in supranational integration’ like ‘Europe of the Regions’ raised hopes that the self-determination demands of sub-national and regionalist parties could also be realized in unity (Hepburn and Elias Reference Hepburn and Elias2011, 859). Nonetheless, this optimistic approach to European integration has been heavily undermined with the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, then the 2017 Catalan independence referendum. The economic crisis in 2008, its subsequent austerity policies, and the wave of populism present in many countries provoked self-determination demands of some sub-national movements in Europe, from Spain to Britain, as can be seen with the dramatic shift in the demands of political actors in Catalonia and Scotland from regionalism to independentism (Barrio, Barberá, and Rodríguez-Teruel Reference Barrio, Barberá and Rodríguez-Teruel2018, 996). Sub-national parties and their constituencies in Europe possess the capacity to alter their perspectives and preferences towards the EU over time, contingent upon evolving dynamics within the Union. While initially opposed to the EU, these sub-nationalists may transition to a pro-EU stance, or, conversely, adopt a more adversarial position in response to subsequent political and institutional developments. This study seeks to investigate whether a comparable shift in the approaches of certain sub-national movements towards the EU, along with their evolving demands for independence and autonomy, can also be observed in the Kurdish context.

The subject of this study comprises how Turkey’s EU membership is seen by HDP-supporter Kurdish voters in Turkey, as a non-EU country that has on-hold negotiations but still an ostensible vision for membership. There is a substantial body of literature on Kurds; however, there is a notable gap in research focusing specifically on the perspectives of Kurds in Turkey regarding the EU and Turkey-EU relations. On the one hand, the EU provides platforms for expressing and pursuing independentist goals; however, it simultaneously impedes the secession process. In essence, the EU continues to serve as a significant discursive reference point for both pro-independence and pro-unity factions (Wagner, Marin, and Kroqi Reference Wagner, Marin and Kroqi2019, 2).

This article, which employs a focus group methodology, examines whether the rising independence demands observed among sub-national movements in the EU are also applicable to the Kurds, as well as how Kurds who vote for the pro-Kurdish HDP perceive the EU in terms of their political and cultural rights. Demonstrating how the gains achieved by Kurds in Syria and Iraq with respect to political and cultural rights have influenced the attitudes of Kurds who vote for the HDP toward the EU is also among the aims of the study. In the first part of the study, the change over time in the approaches of sub-national parties such as Bloque Nacionalista Galego (BNG), Convergència i Unió (CiU), Plaid Cymru, and the Scottish National Party (SNP) toward the European Union will be discussed, as well as how some sub-national parties that had previously only demanded autonomy shifted toward independence due to the EU’s failure to meet their expectations. The second part will briefly address the history of the Kurdish Question, outlining the shift in the demands of the Kurdish political movement, which until the 1990s had aimed to establish a separate nation-state, and describing how both the PKK and the HDP came to adopt the discourse of democratic autonomy. Adopting a Marxist-Leninist ideology, the Kurdish national liberation movement initially aimed at establishing an independent and unified Kurdish state. However, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the movement shifted its focus, separating the concept of self-determination from statehood and reorienting it toward the idea of self-government (Fadaee and Brancolini Reference Fadaee and Brancolini2019, 860). The third part will address the changes in the world order and the impact of the New International Order on Turkey’s foreign policy and the Kurdish movement, explaining how political developments in Syria and Iraq have contributed to the internationalization of the Kurdish Question in Turkey. The fourth part will present both the theoretical framework and the methodology of the article, while the final section will provide an extensive discussion of the findings from the focus group interviews.

The European Union and Sub-National Movements

European integration became tempting for sub-national movements and parties due to the economic and political ‘opportunity structure’ it offered in the 1990s (Keating Reference Keating2004). The creation of a ‘Europe of the Regions’ in the EU prompted these parties to adopt a more positive approach to the EU, since it provided a significant opportunity structure for sub-national parties to realize their territorial goals (Elias Reference Elias2008b; Reference Elias2009). Exhausting the monopoly of nation-states in the domestic market, the EU’s ‘single market without a border’ strategy brought about new economic opportunities for regions (Tatham Reference Tatham2008), while the creation of a ‘Europe of the Regions’ led to the emergence of new possibilities for regional political interests to be pursued (Hepburn Reference Hepburn2009).

Parties such as Plaid Cymru and the SNP have long favored ‘independence in Europe’ over secession, as European institutions like the European Commission and the European Parliament provide opportunities to enhance the bargaining power of sub-nationalists in relation to the states in which they reside (Wyn Jones Reference Wyn Jones2009, 142). The existing opportunities within the EU, including regionalism, minority rights regimes, and European constitutional reform, alongside the vision of a Europe of the Peoples, have generated considerable interest among numerous sub-national movements, fostering their alignment with the concept of self-determination within the EU (Keating Reference Keating2004, 373). However, in recent decades, the EU’s failure to offer the same opportunities to sub-national and regional movements, the decline of the Europe of Regions concept, and the centralization prompted by the 2008 economic crisis in nation-states have strengthened the idea of independence for parties such as Catalan CiU and the British SNP. As Barrio et al. point out, ‘ethnic, exclusivist, or even violent forms of Catalan regionalism have been marginal’ until 2010, but since then, Catalan nationalism has shifted toward independence (Barrio et al. Reference Barrio, Barberá and Rodríguez-Teruel2018, 996). The positions of sub-national parties toward the EU are not static; shifts in constitutional and political developments within the EU can lead to changes in these parties’ stances, with parties initially opposed to the EU adopting a pro-European position, or conversely, the opposite occurring. For example, the Marxist-Leninist BNG, which initially condemned the EU by labeling it as a capitalist organization, has altered both its view of the EU and its demand for self-determination in response to the opportunities and prospects the EU provides to regions. As Hepburn also notes, it would be erroneous to claim that these parties focus solely on local or ethnic issues. Particularly as they adopt pro-European discourse, these parties become ‘Europeanized’ or ‘internationalized’, incorporating issues that are increasingly prominent in elections, such as gender, race, sexual orientation, and ecology, into their political rhetoric (Hepburn Reference Hepburn2009, 486).

The rise of populism in many parts of the world has gripped both national and sub-national parties. In recent years, regionalist parties have again begun to adopt Eurosceptic positions (Elias Reference Elias2008a). The global financial crisis (2008) and great recession delivered new opportunities for several left-wing sub-national and regionalist parties, such as the SNP, Plaid Cymru, CiU with regionalist parties voicing their demands for autonomy, even for independence more, as well as starting to embrace more populist rhetoric (Massetti Reference Massetti2018). As in the example of Spain, some EU member states tried to turn the economic crisis into an opportunity for recentralization, using arguments such as ‘efficiency, cost cutting, and rationalization’ (Muro Reference Muro2015, 35). Youngs argues that the EU’s silence in the face of the Spanish government’s harsh response to the EU referendum in Catalonia has caused great disappointment among Catalans, while the EU’s mismanagement of the eurozone crisis and disputes over austerity measures have added fuel to the independentist fire (Youngs Reference Youngs2017). According to Van Hauwert et al., the growing demands for self-determination in EU countries are related to the increasing regional populist demands and cannot only be explained by decentralization and the resulting institutional autonomy of the regions (Van Hauwaert, Schimpf, and Dandoy Reference Van Hauwaert, Schimpf and Dandoy2019, 309).

Populism’s rise in popularity has resulted in an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ dichotomy, with ‘them’ referring to minority groups such as immigrants, asylum-seekers, ethnic, and cultural groups among others. EU values and ideals such as human and minority rights, democracy, gender equality, and unity in diversity and plurality are under heavy attack from the populist right-wing turn. In the context of Turkey, the ‘others’ of populism are predominantly the Kurdish community and the HDP until 2024.Footnote 1 At the time this article was written, certain political developments of significant relevance to the Kurdish populations in both Turkey and Syria were underway. The year 2024 marked a critical juncture for the Kurdish Question in both Turkey and Syria, initiating a transitional period fraught with uncertainties regarding the future of the Kurds in both countries.

In order to challenge and dismantle the hegemony of Kemalism, Erdoğan, upon assuming power in 2002, embraced a populist rhetoric that garnered support from a diverse range of individuals and groups, including liberals, religious people, Kurds, secular and Islamist bourgeoisie, and even the European Union and countries like the US.Footnote 2 ‘In order to construct his Islamist dominance, Erdoğan has created a bourgeois class and bureaucratic cadres loyal to him while breaking up resistance to his project coming from the media and the judiciary through suppressive and punishing measures’ (Kalaycı Reference Kalaycı2021, 521). ‘During the AKP era, cronyism has lost its instrumental feature and obtained a relational character; that is to say, it is long-term in its orientation and has relationship, affection and loyalty at its core’ (Kalaycı Reference Kalaycı2022, 580). Following this dismantling of Kemalism’s hegemony in the judiciary, bureaucracy, and media, Erdoğan and his party’s discourse shifted to encompass a stance that opposes the West, the European Union, and Christianity. After the establishment of the People’s Alliance, Erdoğan extended his populism to the extent of categorizing anybody who did not endorse him and the People’s Alliance – particularly Kurds, secular citizens, Alevis, and even certain Islamists – as terrorists (Kalaycı Reference Kalaycı2023a, 738). The HDP and its voters, who were explicitly associated with the PKK by the People’s Alliance, were criminalized and portrayed as the primary ‘others’ in the government’s growing authoritarian populism.

HDP and the Kurdish Question

The roots of Kurdish nationalism date back to the 19th century. It emerged in an ethno-religious form and, in the 20th century, led to several uprisings against the new Republic aimed at establishing a homogeneous nation-state. It can be argued that after the organization’s founding in 1978, the dominant power of the Kurdish nationalism was the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), although different currents existed.

Founded on Marxist–Leninist principles, the PKK initially defined its objective as the establishment of an independent Kurdish state, and, in pursuit of this nationalist goal, incorporated into its political struggle Marxist concepts such as class struggle and revolutionary consciousness. By the late 1990s, the PKK had shifted from a Kurdish nationalist agenda toward promoting a discourse of Mesopotamian multiculturalism, partly as a response to accusations of atheism from Turkish state actors, and partly to engage and mobilize various ethnic and sectarian communities in the region, such as Kurdish Alevis and Christians (Leezenberg Reference Leezenberg2016, 673–674). Thus, the leftist and secular Kurdish movement, which had previously been driven by Marxist ideology, abandoned the goal of an independent state and embraced the concept of Turkey’s decentralization and democratic autonomy (Tekdemir Reference Tekdemir2018, 593). As Tekdemir has noted, the Kurdish movement, which underwent a strategic shift, prioritized civil claims over ethnic claims, leading to an adoption of radical democracy. In doing so, the Kurdish movement gained a more legitimate foundation by incorporating not only the legal political movement but also the labor, women, and cultural movements (Jongerden Reference Jongerden2019, 268). Similarly, the BDP/HDP transitioned from an ethnic-focused and exclusive identity approach in 2011 to a more inclusive, liberal, and outward-oriented agenda, grounded in a civic conception of Turkish national identity in 2015 (Grigoriadis and Dilek Reference Grigoriadis and Dilek2018, 289).

In pursuit of self-determination, PKK leader Öcalan rejects the nation-state model and advances democratic confederalism as an alternative (Dirik Reference Dirik2021, 31). The Kurdish political movement has made a radical shift from Marxist-Leninism, nationalism, and statism to communalism and confederalism (Gerber and Brincat, Reference Gerber and Brincat2018, 973). Cemgil has defined democratic confederalism as a ‘self-styled stateless, gender-egalitarian, ecological, direct-democratic social experiment’ (Cemgil Reference Cemgil2019, 1046).

Denying the Kurdish existence as a distinct ethnical group and suppressing their demands through oppression, violence, and assimilation, the Turkish Republic did execute some cultural reforms and abandoned some policies against Kurdish identity so as to start and sustain EU membership negotiations. According to Watts, EU norms and institutions provided new sets of opportunity structures to Kurdish nationalists ‘with a valuable set of resources with which to exercise material and moral leverage against Turkish state’ (Watts Reference Watts2006, 131). However, even during the EU accession negotiations, the Turkish Constitutional Court did not refrain from shutting down four successive pro-Kurdish parties. Similarly, at the time this article was written, following the initiation of a closure case, the HDP changed its name to DEM.

AKP’s ‘Democratic Opening’ or ‘Kurdish Opening’ in 2009 was seen as a historical step towards a resolution of the Kurdish Question and recognition of the Kurdish identity. It raised hopes about the abandonment of policy of denial of any Kurdish Question. However, when in the June 2015 Turkish general elections, the HDP surpassed the electoral threshold of 10%, denying the AKP a parliamentary majority, Erdoğan canceled the Democratic Opening and once again chose to violently suppress the Kurdish Question. With the AKP’s ideology taking a far-right shift upon starting an alliance (People’s Alliance) with two ultra-nationalist parties – Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and Great Unity Party (BBP) – the optimism for a peaceful resolution for the Kurdish Question was cut short (Grigoriadis and Dilek Reference Grigoriadis and Dilek2018, 292). Following the 2016 coup attempt, HDP co-leaders Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ, as well as many Kurdish MPs and democratically elected mayoralties were imprisoned through emergency powers on charges of supporting terrorism. Almost all Kurdish mayors were replaced with state-appointed trustees and some of them were later arrested.

However, in October 2024, following MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli’s historic and shocking call to PKK leader Öcalan – and Öcalan’s subsequent positive response – a new phase was once again entered in the Kurdish Question. Öcalan’s public appeal to end armed struggle (27 February 2025), followed by the PKK leadership’s declaration of a ceasefire and formal dissolution at its 12th congress (May 2025), and the Turkish parliament’s formation of a supervisory commission in the summer of 2025 to oversee disarmament and recommend legal reforms, marked the beginning of a new phase in Turkey’s reconciliation process. On 5 August 2025, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey established a commission called the ‘National Solidarity, Brotherhood, and Democracy Commission’ under the slogan of a ‘Turkey without terrorism’, which began holding various meetings aimed at resolving the Kurdish issue (Solmaz Reference Solmaz2025). From the beginning, it has remained unclear whether any negotiations occurred between Abdullah Öcalan, imprisoned on İmralı Island, and the AKP government, and no information has been disclosed to the public regarding prospective measures on the political and cultural rights of Kurds beyond the question of the PKK’s disarmament. What is particularly striking, however, is that during this process – when discussions were underway regarding granting Öcalan the hope of release – neither of the former imprisoned co-chairs of the HDP, Selahattin Demirtaş nor Figen Yüksekdağ, were released, and the detention of HDP mayors appointed under trusteeship also continued.

New International Order and Internationalization of the Kurdish Question

The EU is experiencing a decline in its stature as an important transformative power, diminishing its ability to shape the political preferences in member states such as Poland and Hungary, as well as candidate states such as Turkey (Kutlay Reference Kutlay2018, 8). Indeed, it is noteworthy that in these countries, the sense of opposition towards the EU has manifested itself as a phenomenon capable of garnering electoral support for certain political parties, as well as an indication of the diminishing reputation and appeal that the EU has experienced. Moreover, Turkey’s emergence as a growing regional power with expanding economic prospects appears to have diminished the significance it assigns to EU accession (Bürgin and Aşıkoğlu Reference Bürgin and Aşıkoğlu2017, 125).

The handling of the eurozone crisis and subsequent migration flows profoundly undermined the EU’s ethos of solidarity (Kutlay Reference Kutlay2018, 8). The discrediting of the Western-created liberal international order because of the recent financial crisis, coupled with the growing influence of emerging nations such as China and Russia in global affairs (particularly evident in Russia’s significant involvement in the Syrian crisis), has inevitably impacted Turkey’s foreign policy choices (Kubicek Reference Kubicek2022, 649).

According to Kutlay and Öniş, who argue that due to major shifts in the US-led liberal international order, Turkey has transitioned from a soft-power-oriented regional actor to a more assertive military power, this unusual middle-power activism has contributed to the success of an authoritarian populist government by strengthening nationalist sentiments and exploiting immediate populist gains, although the long-term implications of this shift are contrary to the desired outcomes (Kutlay and Öniş Reference Kutlay and Öniş2021, 3052-53). ‘Charismatic populist-nationalist-authoritarian leaders seem to be a central feature of the emerging post-liberal international order’ (Öniş Reference Öniş2023, 701).

According to Ercan, who argues that neither the EU nor NATO has made a significant contribution to the peaceful resolution of the Kurdish question, the country’s geostrategic importance and, in particular, its NATO membership ‘has provided a priceless political shield for Turkey and ensured persistent military support despite the gross human right violations the Turkish state has committed to contain the Kurdish insurgency’ (Ercan Reference Ercan2019, 113). The EU authorities, who initially regarded the Kurdish Question as a democratization problem of Turkey, had to admit that after the recent developments in Iraq and Syria, the Kurdish issue wouldn’t be resolved solely in the context of Turkey. In the 1990s, the first Gulf War and the establishment of an autonomous Kurdish zone in Iraq led to an internationalization of the Kurdish question, which was no longer merely a domestic Turkish issue. As a result of these developments, Kurdish(ness) no longer referred to only ethnic identity but to ‘an increasingly politically relevant community both in Turkey and in the region’ (Boyraz and Turan Reference Boyraz and Turan2016, 412). For Kurdish nationalists in Turkey, ‘stronger ties beyond the borders of the nation-state, namely Rojava and Iraqi Kurdistan’ have become increasingly important (Boyraz and Turan Reference Boyraz and Turan2016, 416). The AKP government not only viewed the pro-Kurdish developments in Syria as a threat to the Turkish state but also reduced the Kurdish issue to a purely national security one (Whiting and Kaya Reference Whiting and Kaya2021, 825–826).

On the other hand, the unexpected developments and sudden change of government in Syria over the past year have compelled Turkish foreign policy to refocus on Syria, and particularly on the Kurds within Syria. A coalition spearheaded by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and bolstered by Turkish-backed factions initiated a significant military operation, dubbed ‘Deterrence of Aggression’, which culminated in the downfall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Following the war in Syria that has persisted since 2011, the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad brought an end both to his decades-long dynasty and to the Assad family’s rule, which had lasted less than 54 years. With the collapse of the Assad regime, Syria has swiftly transitioned from authoritarian Baathist rule to a transitional period led by former HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa (VOA 2024). On 10 March 2025, Mazlum Abdi, commander of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which largely control the eastern and northeastern provinces of Syria, and Ahmed al-Sharaa, President of the interim Syrian government, signed a landmark integration agreement envisioning the incorporation of the SDF into the new administration. Under this accord, both the civil and military institutions under SDF control in northeastern Syria would be integrated into the Syrian state, and in return, Kurdish citizens would be recognized as a foundational part of the country, enjoying full rights (BBC Türkçe 2025).

Despite the interim constitution, calls for dialogue, and agreements such as those reached with the Kurds, it would not be inaccurate to argue that Syria faces a period of continued uncertainty and even instability due to the largely provisional nature of its legal and institutional frameworks, with timelines yet to be defined. For example, the concentration of power in the presidency under the interim constitution has led Kurds, Druze, Alevis, and other minority groups to feel marginalized and excluded from the decision-making process, prompting attempts to challenge the interim Syrian government. On the other hand, the Turkish government, closely monitoring these political developments in Syria, continues to oppose the empowerment of the SDF within Syria’s administration and the establishment of a federal Syria, as it regards the People’s Protection Units (YPG) – the backbone of the SDF – and the Democratic Union Party (PYD), which governs a large area in northern Syria, as extensions of the PKK and designates them as a ‘terrorist organization’.

Social Constructivist Approach

To analyze the shift in Kurdish perceptions of the EU and the impact of political developments in Northern Iraq and Syria on these perceptions, this study adopts a social constructivist approach. Social constructivist theory asserts that identities, meanings, perceptions, values, and realities are not fixed or inherent, but are instead constructed through ongoing social and human interactions. In this context, the transformation in Kurdish attitudes toward the EU is not viewed as a static political position, but rather as a dynamic reflection of evolving social processes and relational contexts.

According to Berger and Luckmann, reality and social systems are constructed through human interactions, institutions and, in the process, gain legitimacy (Berger and Luckmann Reference Berger and Luckmann1966). While constructivist literature highlights the role of institutions in shaping and defining ethnic and national boundaries, these institutions also serve as spaces for social interaction where their meanings and significance are elaborated, challenged, or transformed (Goode and Stroup Reference Goode and Stroup2015, 730).

According to Alexander Wendt, one of the pioneering figures of social constructivism in International Relations, international politics is not predetermined, as national interests and identities are not fixed but are constructed through intersubjective practices (Wendt Reference Wendt1999, 71-72). He claims that constructivism is a structural theory of international relations that emphasizes the following key points: (1) states are the central focus of analysis in international political theory; (2) the primary structures within the international system are shaped intersubjectively, rather than by material factors; and (3) the identities and interests of states are largely formed through these social structures, rather than being determined by human nature or internal political dynamics (Wendt Reference Wendt1994, 385). Constructivists argue that communication and interactions between states are pivotal in shaping the formation of their identities and interests. The international system is not static but is continually constituted and redefined through dynamic communicative processes. A key point here is that the identities of actors are not predetermined or fixed; rather, they are inherently fluid, developing and transforming within these ongoing communication processes (Coban-Ozturk Reference Coban-Ozturk2015, 66).

Focus Group Methodology

For this study, which adopts a social constructivist approach, focus group discussions with small groups were chosen. As a qualitative method that allows for in-depth exploration of participants’ shared perspectives, experiences, attitudes, habits, encounters, and perceptions on a specific topic, the focus group method is particularly well-suited to the social constructivist framework. Indeed, the focus group method fosters a type of group interaction that enables participants to refine and explore both shared and individual perspectives (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007, 351). Focus group meetings, valued for their efficiency in gathering information, typically involve semi-structured, unstructured interviews between the group and a moderator. This methodology is widely regarded in the social sciences for its ability to capture the impact of group dynamics during discussions, facilitating the acquisition of in-depth information and the generation of ideas (Bowling Reference Bowling2002).

In qualitative research, data collection and analysis focus on words, expressions, and discourse rather than figures (Bryman Reference Bryman2012, 380). Therefore, the aim is not to generalize the information obtained and for the researcher, revealing evaluations, views, and feelings of the participants is essential. As a qualitative data collection method, focus group meetings are an interview technique for gathering rich, in-depth and detailed information (Plummer Reference Plummer2008, 123). Aiming to identify interviewee views, feelings, expectations, and experiences, focus group meetings prioritize participant subjectivity and strive to better grasp their positions on a certain subject.

This article does not aim to make generalizations about the Kurdish population voting for the HDP. Moreover, Kurdish individuals living in Istanbul or in some southeast Anatolian cities (where the Kurdish population is predominant) may have different opinions, experiences, and feelings. The interviewees in this study are only residents of Istanbul, although many of them moved there from other parts of Turkey, were forced to migrate, or have relations, ties, and relatives in the provinces from which they came.

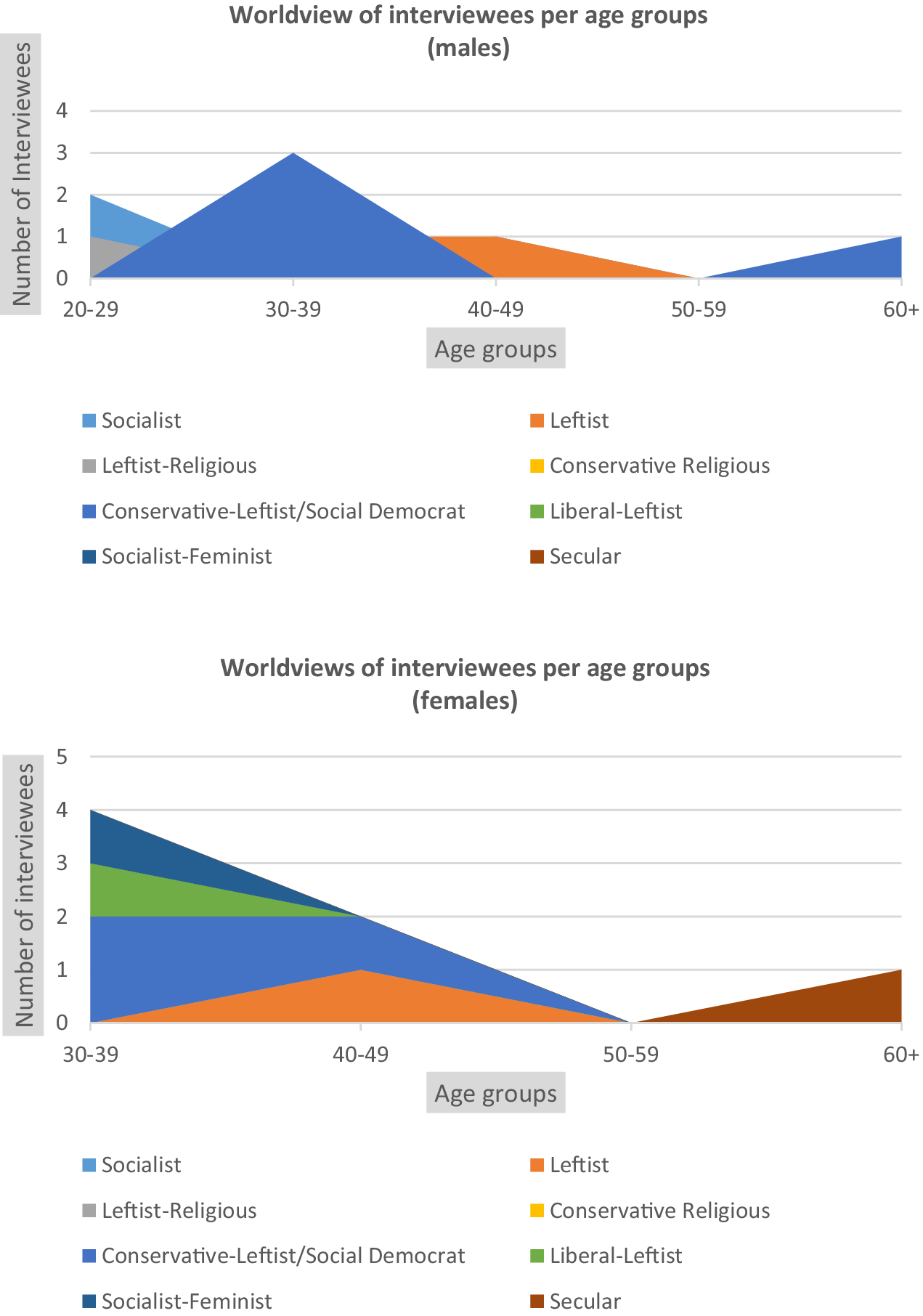

As part of this study, 4-day face-to-face meetings were conducted with 24 HDP-supporting Kurdish voters – 12 male and 12 female from different age groups, socio-economical and educational backgrounds, all living in Istanbul (Figure 1). In four separate sessions held over four consecutive days from November 2 to 5, 2021, interviewees were initially asked how long they have lived in Istanbul, their hometowns, and whether they know Kurdish or not. Although all interviewees were living in Istanbul, only two of them were born there. Some had immigrated to Istanbul only a few months before the interviews took place, while others had immigrated years previously from Kurdish-majority cities such as Batman, Bitlis, Şırnak, Mardin, and Dersim, either of their own volition or of necessity. The interviewees were sourced by the survey company Artıbir Araştırma through social media announcements, calls, and the company’s database.

Figure 1. Profile of focus group interviewees

The corpus of data derived from the four iterative focus group discussions underwent systematic qualitative evaluation. Utilizing the ‘scissor and sort’ technique, the analytic process entailed the identification, juxtaposition, and categorization of congruent and discrepant statements in relation to the social experiences elicited from participants (Stewart and Shamdasani Reference Stewart and Shamdasani2014, 123f.). This manual content analytic strategy facilitated the delineation of recurrent thematic regularities, which were subsequently subjected to successive phases of interpretive and comparative analysis. The scissor-and-sort technique, also known as the cut-and-paste method, offers a relatively efficient and economical strategy for the analysis of focus group transcripts. The process involves identifying salient portions of the transcript, constructing a categorical framework to organize the topics raised during discussion, selecting illustrative statements for each category, and synthesizing these into an interpretive understanding of their overall significance.

All participants, 12 of whom were women, resided in Istanbul and confirmed that they either voted for or planned to vote for the HDP. To select the interviewees who met the study’s criteria, five field staff members from the survey company conducted a field scan, involving 300 face-to-face interviews with potential candidates. During the field scan, candidates were asked about various factors, including their age, gender, educational background, marital status, employment and income levels, worldview, the party they had voted for in previous elections, the party they intended to vote for, their proficiency in Kurdish, and their membership in any political party, NGO, or association. Special care was taken during the interviewee selection process to ensure the inclusion of both HDP members (with strong ties to the party) and HDP voters (without strong affiliations to the party). The focus group meetings, conducted over four days, were organized in groups of six, as larger gatherings were deemed too risky due to the pandemic.

In these meetings, consisting of groups of 6, interviewees were asked about their expectations regarding the European Union and their perception of Europe. Although these interviewees all voted for HDP in the previous elections and will vote for HDP in the upcoming ones, they demonstrate different ideological inclinations as some of them identify themselves as socialists, feminists, or religious conservatives.

Concerns have arisen in recent years regarding the future of the European Union due to several crises, including issues with the Eurozone, Brexit, and the Catalan referendum. Furthermore, the current state of Turkey-EU relations (which has reached a state of stagnation) and the EU’s diminished ability to support Turkey’s democratization process have prompted inquiries into whether the Kurds still hold expectations from the EU regarding matters such as human and minority rights, as well as whether the EU continues to generate the same level of enthusiasm among the Kurds. The primary objective of this focus group methodology study is to obtain answers regarding the aforementioned inquiries.

Focus Group Questions

-

1. What are your thoughts on the European Union? How would you describe the EU in a few words?

-

2. In your opinion, how has the EU impacted Turkey’s democratization process? Has it brought about any changes or improvements in the lives of the Kurdish people?

-

3. Do you believe the EU can provide autonomy and freedom to nations or peoples without a state, such as the Kurds?

-

4. Are you aware of the EU’s stance regarding the arrest of Selahattin Demirtaş and the dismissal and arrest of HDP-affiliated mayors? What are your thoughts on this matter?

-

5. If Turkey were to become a member of the EU, would you prefer to live in an EU-member Turkey or in an independent Kurdish state that is not a member of the EU?

-

6. Do you think Kurds could enjoy greater freedom and autonomy in an EU-member state? Why?

Although the questions were prepared in advance, different topics of discussion arose in each session, and some of these questions were not directed at the interviewees.

Findings

A large number of interviewees who were either born in Istanbul or had moved there a long time ago stated that they either did not speak Kurdish or could speak only a little Kurdish, while some mentioned that they had started learning Kurdish in Kurdish associations. On the other hand, interviewees who had recently migrated to Istanbul from southeastern provinces indicated that they spoke Kurdish more fluently. Although there was no such prerequisite for the interviewee selections, the overwhelming majority of interviewees consist of individuals who believe they have been discriminated against in Turkey due to their Kurdish identities. These HDP-supporter Kurdish interviewees state they are on bad terms with their neighbors because of the parties they support. Interviewees claimed that they were stigmatized not only because they were Kurdish, but also because they voted for the HDP, revealing that they faced double discrimination. They also add that they have been excluded and insulted by not only Turks who do not vote for HDP but also AKP-supporter Kurds, explaining AKP’s populist rhetoric based on polarization causes division among Kurds too.

Interviewees’ Perceptions of the EU

When asked ‘What does the European Union evoke in you, and how would you describe that?’ the interviewees responded with mostly negative expressions. Although HDP does not exhibit an anti-European or anti-Western stance in its politics or its rhetoric, the interviewees use negative terms like ‘imperialist’, ‘colonialist’, ‘occupier’, ‘racist’, ‘coward’, ‘concerned’, ‘egoist’ in response to the question ‘Could you describe the European Union with a few words?’

For instance, interviewee number 7 thinks the Europe and the European Union were able to establish justice and freedom within; however they make life hell in countries they consider colonies. Echoing interviewee number 7, interviewee number 12 says: ‘From my perspective (the Europe) it reminds me of hypocrisy and violent racism’. Even among the interviewees who identify the Europe with freedom, human and economic development, welfare, and human rights, there is a majority who blame the Europe with hypocrisy and practicing double standards.

Interviewee number 5, HDP member, criticizes the European Union: ‘European Union means living in democracy themselves, seeking own interest. We especially observed this with refugees crisis’. Interviewee number 3, another HDP member, claims that EU and NATO have brought the most damage to Kurds. He also criticizes the European approach to Kurds: ‘At the slightest resistance by Kurds the so-called democratic European countries immediately unveil the big stick they carry. I don’t find the West and Turkey much different from each other. Europe, Turkey, the US are all imperialists’.

The interviewees from the Kurdish movement, who may be described as Kurdish nationalists, were more aware of certain institutions such as the EU and NATO, as well as of the EU’s silence towards Turkey’s cross-border operations in northern Iraq and Syria. They were also more aware of issues within the EU such as the Catalan referendum and Brexit. In particular, these interviewees expressed extreme disappointment that the EU does not strongly oppose cross-border operations. They complained that the EU turns a blind eye to Erdoğan’s authoritarianism, remains silent on the oppression of the Kurds and cross-border operations, and, moreover, indirectly supports this very oppression through its actions.

The diminished level of enthusiasm surrounding the EU can be attributed to various crises, including but not limited to Brexit, migration, and financial challenges that the EU is currently grappling with, as well as the absence of a clear prospect for Turkey’s membership.Footnote 3 Although EU countries are not inclined to completely sever negotiations with Turkey, it is clear that Turkey’s prospective EU membership is no longer tenable, as its state acts more as a strategic ally and trading partner (Saatçioğlu Reference Saatçioğlu2020, 170). After Turkey gained candidate status in 1999 and began accession negotiations in 2005, relations with the EU have almost come to a standstill. ‘In the late 2010s, the AKP government has distanced itself from the traditional Kemalist Western-oriented foreign policy, which focused on Europe and prioritized the EU membership’ (Atay Reference Atay2021, 568).

On the other hand, it is sure that the interviewees expressing positive opinions about the EU were more likely to have been influenced by the economic prosperity and good living conditions provided there than by the idea that their cultural and political rights would be secured within the EU. The interviewees anticipated little contribution from the EU towards the political and cultural rights of Kurds, as it focuses solely on individual rights. A significant portion of those in favor of EU membership were more interested in settling in Europe (and benefiting from the employment opportunities and economic prosperity there) than in the democratization of Turkey that could be achieved through the EU. The interviewees’ general views on the European Union align closely with those commonly held by citizens of many Third World countries: it is seen as economically more prosperous, wealthier, and more advanced in terms of freedoms and democracy.

Do the Kurds demand independence?

Keating believes the EU’s imposition of ‘the idea of limited sovereignty, territorial accommodation, and subsidiarity’ presents a new framework for sub-national movements and regions, enabling opportunities to transcend independentist demands (Keating Reference Keating2000, 39). In recent years, independentist demands of some sub-national movements within the EU have increased, and independence referendums have even been held in Scotland and Catalonia. This following question aimed to determine whether Turkey’s possible accession to the EU could have a dampening effect on the Kurdish desire for independence.

For some, the idea of an independent Kurdish state is greatly appealing, while some found the idea of a fair and free EU member Turkey better. For instance, while interviewee number 6 states ‘I would rather prefer a fully independent, fully local Kurdistan that respects human rights and is not a base for foreign state soldiers’ interviewee number 10 indicates ‘I would like to live in an EU member country, a world where living conditions and people live fairly’. As for interviewee number 12, he says ‘I would like to live in an EU member Turkey. Although the idea of an independent Kurdish state is tempting, EU member would be better’ pointing out that both ideas can be appealing for Kurds.

Criticizing the EU’s stance towards the refugee crisis and blaming them for hypocrisy, interviewee number 1 is indifferent to the EU membership due to their silence against massacres of Kurds by AKP. He expressed frustration with the EU’s inadequate response to human rights violations in Turkey, particularly the June-November 2015 massacre of civilians in cities with high Kurdish populations such as Cizre, Silopi and Sur. Interviewee number 3, who had his home raided several times for being a member of the HDP, states that he certainly would like to reside in an independent Kurdish state.

It could be understood that the expectation for women’s rights and better quality education plays a part in female interviewees’ more positive approach to the EU membership. Interviewee number 20, an ‘Armenian Kurd’ by her own definition, explains why she would prefer the EU membership as the following: ‘At least women’s rights etc. would be better. I am a mother, I want to leave safer things for my child now, that’s what I dream of’. In addition to the female interviewees number 14 and 18 who demand EU membership for the hope of a dignified life, interviewee number 20 underlines that women live more freely in Europe: ‘What appeals to me is that the European society is open to difference. That’s why my identity as a Kurdish woman wouldn’t be an issue or a problem in Turkey as an EU member. Because it won’t be a problem to wear my hair exposed or covered, or to dye it blue, I would like to live in an EU member country’.

Only female interviewees number 17 and 18 indicate that they would like to reside in an independent Kurdish state, although their main motive is based more on the fact that they do not want to inhabit the Turkish borders, more than their reluctance to live in Europe. Interviewee number 17 states: ‘I would also definitely want to live in places where Kurds reside. I want to get away from the pressure of Istanbul under the AKP domination’.

A journalist from the Kurdish political movement, interviewee number 16 adopts a different approach than the others:

I don’t want to live anywhere under the name of a Kurdish state. A democratic Turkey appeals to me more. Since I’m against the notion of the nation-state itself, I believe if a Kurdish state happens today same things will repeat. In any case, I will be facing the oppression any state practices on its citizens, based on the excuse of an external threat aiming at the Kurdish unity, the same old national unity excuses. Because for example there is a Barzani-dominated federation in southern Kurdistan today and it’s almost heading to autonomy but there’s poverty, oppression, violence, whatever you can imagine.

The HDP and the PKK, which emerged with a Marxist-Leninist ideology, maintain a secular discourse, while interviewees who are members of the HDP or hold secular and feminist views tend to idealize the Rojava model, which is more multi-ethnic and multicultural, as a political governance model, whereas they perceive the Barzani administration in Northern Iraq as authoritarian and Islamist, akin to Erdoğan’s government in Turkey. Rojava has shown a commitment to gender equality through its system of rotating co-chairs, in which leadership positions are shared equally between men and women with equal authority (Ahmad, MacTavishand, and Christie Reference Ahmad, MacTavishand and Christie2024, 108). Female interviewees, including those who identify with conservative religious beliefs, exhibited a heightened sensitivity for individual rights, particularly women’s rights, in comparison to their male counterparts.

The responses regarding the potential impact of the European Union on the rights of the Kurdish population reflect a prevailing sense of pessimism among the Kurds regarding EU membership. Nearly all interviewees expressed their belief that Turkey’s accession to the EU is highly unlikely, particularly as long as the AKP maintains its position of power. Interviewees affiliated with the Kurdish political movement, specifically members of the HDP, seem to be influenced by the EU’s negative stance regarding the Catalan referendum, thus believing their self-determination demands will not come true within the EU context. They expressed a lack of optimism concerning fulfillment of the Kurds’ aspirations for self-determination, especially in the event of Turkey’s accession to the EU. The imprisonment of certain Catalan lawmakers following the independence referendum, combined with the European Union’s support for Spain, undeniably influenced the situation.

Pointing out the EU’s negative approach to the Catalan autonomy referendum, interviewee number 5, HDP member, thinks Kurds will suffer the same oppression Catalans faced in Spain. He believes there should not be too much optimism although the rights of Kurds in Turkey would improve in an EU member Turkey, and expresses his hopelessness about Kurdish autonomy and rights, claiming the Catalan experience stands as an important example for the Kurds too.

Multiculturalist Rojava: ‘Democratic Confederalism’

Following the revolution in Northeastern Syria in 2012, a new political organization emerged in Rojava in 2014, premised upon the principles of ‘democratic autonomy’ and confederalism, and these developments in Syria created new opportunities for the Kurds. It would not be inaccurate to argue that the revolution in Rojava and the subsequent formation of The Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES) were grounded in Öcalan’s ideas of ‘democratic autonomy’ and ‘confederalism’ (Cetinkaya Reference Çetinkaya2025, 1-2). Rojava is sanctified as a ‘holy place’ not only by some Kurds in Turkey but also by segments of the Kurdish diaspora in Europe and is admired or idealized as a source of ‘huge hope’ (Cetinkaya 2025, 15). Rojava is portrayed as a unique achievement that has ensured stability, security, multiculturalism, and sustainable peace in a chaotic and conflict-ridden region (Ahmad, MacTavishand and Christie Reference Ahmad, MacTavishand and Christie2024, 92). The Kurdish-led project of democratic confederalism in Rojava (northern and northeastern Syria) has gained renown as an extraordinary experiment in eco-feminist and anti-capitalist direct democracy, scarcely paralleled anywhere else in the world (Matin Reference Matin2019, 1075).

Cemgil and Hoffmann have described the Cantons of Rojava as local, anti-authoritarian, anti-hierarchical, and communitarian. The impact of regional models, including developments in Northern Iraq and Syria, on the reconstruction of Kurdish identity and their evolving demands highlights the intricate relationship between this process and the broader social context. The governance model known as ‘democratic confederalism’ or ‘libertarian municipalism’ in Rojava encompasses elements such as community-based cooperative production and trade, social ecology, radical gender equality, and localized forms of direct democratic political governance (Cemgil and Hoffmann Reference Cemgil and Hoffmann2016, 54). Interviewee number 6 spoke with admiration and praise about the new form of governance emerging in Rojava, emphasizing in particular that Kurds, Arabs, Yazidis, Alevis, Armenians, Druze, and many other ethnic, religious, and cultural identities coexist there in peace and harmony. Interviewee 17 argued that in Rojava, Druze, Alevis, Armenians, and Kurds coexist peacefully, and therefore claimed that the place where multiculturalism is actually realized is not the EU, but Rojava. Another interviewee (number 1) argued that nation-states prevail in the EU, and therefore, multiculturalism and radical democracy cannot be realized within the EU as long as nation-states maintain their dominance.

One may argue that the desired outcome for Kurds is no longer EU multiculturalism but rather a multiculturalist lifestyle in Rojava, a location romanticized for its harmonious coexisting ethnic and religious identities. The majority of the HDP member interviewees expressed a preference for residing in a location such as Rojava rather than in an EU member nation. Consequently, when compared to the potential advancements of the Kurds in Turkey upon its accession to the EU, they placed greater significance on the political advancements made in recent years by the Kurds in Syria, aspiring for a comparable achievement.

Interviewees who did not come from the Kurdish political movement and whose association with the HDP was limited to their role as voters demonstrated a notably limited understanding of the Kurds in Iraq and Syria, as well as Rojava, whereas interviewees who were members of the HDP tended to idealize Rojava as a success story of multiculturalism and confederalism. A significant portion of these interviewees attributed considerable value to the political and cultural achievements of the Kurds in Rojava, while they did not exhibit the same optimistic outlook toward the Kurdish administration in Northern Iraq. Feminist women interviewees, particularly those aligned with the Kurdish political movement criticized Iraq’s Barzani government, describing it as an Islamist authoritarian regime, akin to Erdoğan’s Turkey, where cronyism, bribery, and nepotism thrive.

When the names of Northern Iraq, Syria, Rojava, PKK, Kandil, and Öcalan were mentioned, it was observed that the less politically engaged interviewees refrained from participating in the discussions and instead occupied themselves with other matters, revealing a sense of alienation between those from the Kurdish political movement and the others. It has been noted that those whose relationship with the HDP was limited to voting occasionally expressed their dissatisfaction with the discussion of such topics. Considering that video recordings were made of each session, it is likely that the presence of these recordings caused discomfort during the discussion of topics that could be considered ‘sensitive’ in Turkish politics. ‘Political parties and elites play cue-giving roles; their discourses and attitude towards autonomy and secession constitute a focal point for the members of that ethnic community’ (Sarigil and Karakoc Reference Sarigil and Karakoc2016, 336). This focus group study revealed that individuals who identified as members of the HDP exhibited a discourse aligning more closely with the principles of democratic autonomy advocated by the PKK and its leader, Öcalan. When compared to the interviewees who were not party members, they displayed a greater divergence from the discourse of Turkeyfication, which the HDP has sought to endorse over a sustained period. Therefore, the conclusions derived from the focus group studies cannot be generalized, and it is not tenable to assert that all members of the HDP share identical perspectives. However, it was observed that the interviewees, particularly those who emphasized their affiliation with the Kurdish movement, exhibited a greater inclination towards embracing the views espoused by the PKK rather than those put forth by the HDP. The HDP-affiliated interviewees’ attention appears to have shifted away from the EU (which played a significant role in acknowledging the Kurdish identity and promoting the fundamental rights and freedoms of the Kurdish population until the 2000s), now focusing more on countries like Syria and Iraq, where Kurdish identity has begun to be recognized and has gained autonomy.

The issue of Syrian refugees

Although no questions were explicitly directed on this matter, the issue of Syrian migrants nonetheless emerged in all sessions. The EU looks at migration through a securitization lens and has externalized migration governance to third countries (Thevenin Reference Thevenin2021, 464-66). It may be claimed that the refugee deal between the EU and Turkey was the event that most damaged the image of the EU for the Kurdish interviewees. The German chancellor’s visit to Erdoğan, who was recovering from the loss of his parliamentary majority before the November 2015 elections, was viewed as election support, drawing widespread criticism (Reiners and Tekin Reference Reiners and Tekin2020, 119). Most of the interviewees did not approve of the HDP’s lenient attitude toward refugees. In fact, they blamed refugees for the astronomical increase in rents in Istanbul, as well as for the fact that both Kurds and Turks are losing their jobs because refugees are being used as cheap labor.

The Turkish state’s ‘ad hoc leniency towards the use of refugee labor in the informal sector’ has allowed Turkish business and capital owners to exploit the labor of Syrian refugees (Bélanger and Saracoglu Reference Bélanger and Saracoglu2020, 414), causing the Turkish and Kurdish working class to suffer from job losses and deteriorating working conditions. ‘Syrian refugees in Turkey continue to be part of the multiple pathways to precarity, differential inclusion, and negotiated citizenship rights’ (Baban, Ilcan, and Rygiel Reference Baban, Ilcan and Rygiel2017, 41).

As for the question of Syrian refugees, it is found that almost none of the interviewees adopt the HDP politicians’ approach to embracing refugees.Footnote 4 In all sessions, the Syrian question had been brought up although it was not specifically asked, and extremely negative opinions like they have to be sent back to their home country and/or they steal Kurds’ jobs were voiced. It is no exaggeration to say that the EU’s firm attitude against Syrian refugees that they should stay in Turkey and not be sent to Europe is the greatest factor spoiling the interviewees’ perception of the EU. The poorer Kurdish interviewees in particular feel that Syrian refugees working uninsured as low-cost labor are a major threat. Despite hearing criticism from some interviewees that Syrian and other foreign refugees work in terrible conditions for extremely low wages, other interviewees had little interest in the refugees’ working conditions and solely focused on these refugees’ stealing jobs from Kurds and Turks in a complaining tone. Most interviewees think Syrians should be sent back to their country immediately, blaming the EU as much as they blame Erdoğan’s government. Most interviewees agree that Erdoğan does not wish to be part of the EU but ensures that his anti-democratic deeds are being tolerated when he plays his Syrian refugee card against the EU and that the EU keeps silent and continues the negotiations for the sake of having Syrians stay in Turkey.

Only one of the interviewees, a member of the HDP, expressed a view consistent with the party’s position on Syrian refugees, emphasizing that they should be hosted in the best possible manner, but none of the interviewees pointed out that there are Kurds among the Syrians. Economic concerns may have taken precedence over the recognition of Kurds among the Syrians; or for Kurds living in İstanbul, the kinship ties with Syrians may have been of secondary importance.

Conclusion

These focus group discussions were conducted in late 2021, during a period when Erdoğan’s authoritarian regime had intensified its pressures not only on the Kurds and the HDP but also on all groups opposed to the AKP, including Alevis, secularists, liberals, and even dissenting religious conservatives. During this period, Turkey-EU relations had nearly reached a breaking point and the EU’s contribution to Turkey’s democratization process – in other words, the EU’s transformative power over Turkey – had diminished to a virtually negligible level. On the other hand, developments in neighboring Syria have sparked hope among the Kurds, leading many Kurds in Turkey to shift their focus from the EU to this region – specifically to Rojava. The presence of separatist relatives within a group also enhances the probability of that group adopting independentist tendencies, implying that secessionism could potentially be contagious, at least among ethnic kin (Ayres and Saideman Reference Ayres and Saideman2000, 1135). This focus group study demonstrated that those with stronger Kurdish nationalist sentiments were influenced by the attainment of autonomy by Kurdish factions in Iraq and Syria, as well as that the advancements in Rojava had a growing impact on their inclination towards advocating for independence. Particularly, Kurds affiliated with or sympathetic to the Kurdish political movement have argued that they prefer the political model of Rojava over the EU, asserting that the ultimate solution for the Kurdish issue lies in the Rojava model. According to these interviewees, the model of democratic confederalism in Rojava is the most ideal solution not only for Syrian Kurds but also for Kurds in Turkey.

The findings from the focus group study suggest that a significant segment of the Kurdish population in Istanbul no longer attributes substantial importance to the EU’s historical contributions to the advancement of Kurdish cultural and political rights. Moreover, the EU’s rights-based discourse, which predominantly emphasizes individual rights, is increasingly perceived as inadequate in addressing the broader social and cultural challenges faced by Kurds.

‘The liberal democratic ethos’ in member states has eroded in the wake of the dramatic rise of ‘Euroseptic nationalist populist parties’ (Öniş and Kutlay Reference Öniş and Kutlay2019, 227). The perception that the EU does not speak out much against Erdoğan’s authoritarianism and imprisonment of Kurdish politicians except in exchange for keeping Syrian refugees in Turkey, coupled with the democracy crises and authoritarianism emerging in most Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, especially Hungary and Poland among the countries that became EU members the latest, seems to have ruined the reputation of the EU for this study’s participants.

While all interviewees asserted that they faced prejudice and discrimination in Turkey as a result of their Kurdish identity and support for the HDP, it is important to note that not all of them expressed a desire for autonomy and independence. Party members primarily prioritize Kurdish identity and the collective rights of Kurds, whereas those not affiliated with the party and who have limited involvement in the Kurdish movement tend to address their concerns within the framework of human rights and democracy. Interviewees expressing a desire for independence and/or autonomy held the view that the European Union’s democracy and human rights approach does not sufficiently address the Kurdish problem. In other words, the Kurdish issue encompasses not only concerns related to democracy and human rights but also to the acknowledgment of Kurdish identity, the recognition of their right to self-determination, and the attainment of self-governance rights, as exemplified in Northern Iraq and Rojava. According to the interviewees, the EU has declined to support the Catalan independence vote and has remained silent on Turkey’s cross-border operations that undermine the autonomy of the Kurds in Syria, leading them to believe that the EU is unlikely to provide assistance in the Kurds’ pursuit of democratic autonomy.

Due to the political and cultural advancements made by the Kurds in Iraq and Syria in terms of gaining autonomy, the Kurds in Turkey have redirected their attention towards neighboring Middle Eastern countries, motivating the AKP government to take military actions in Northern Iraq and Syria out of concern for serious threats to national unity that would impact Kurds in Turkey (Ozkahraman Reference Ozkahraman2017, 59). These developments prompted the Kurds in Turkey to closely monitor and support favorable developments for their counterparts in neighboring countries. In contrast to advancements for the Kurds in the Middle East, the EU has witnessed several setbacks regarding sub-national movements such as that involving the incarceration of certain Catalan politicians advocating for independence, as well as the failure to achieve anticipated progress and enhancements in Europe of Regions. Therefore, the developments in the Middle East have generated significantly more enthusiasm and intrigue than those in the EU.

Disclosure

None.