Attend any workshop, conference, or panel that includes early career researchers and the conversation will be steered inexorably toward the academic job market: who is hiring, who has attained a tenure-track position, and who is out of luck this season. Tenure-track positions are a type of academic job that typically involve a probationary period (e.g., five to seven years) culminating in an evaluation of research, teaching, and service, that—if successful—results in permanent employment, job security, and academic freedom. This obsessive focus on career trajectories is warranted. As of 2019, 53.5% of colleges and universities had replaced tenure-eligible lines with contingent positions (Tiede 2022); today, 71% of faculty in the United States are not tenure track (Culver and Kezar Reference Culver and Kezar2020). The erosion of permanent jobs in American higher education is linked to a complex intersection of political and economic factors, including decreasing federal support for higher education, concomitant increases in student debt (Gusterson Reference Gusterson2017), a pronounced shift in university investment from faculty to administration (Graeber Reference Graeber2018:162–163), and the growing privatization and market orientation of scientific research (Mirowski Reference Mirowski2011).

These cultural and economic shifts are also well encapsulated by anecdata; any conversation with a junior scholar will reveal the impact of these larger professional transformations on personal and career trajectories. The first author on this article has applied to five academic positions over the course of his career, whereas the last author has applied to 100. A 20-fold increase in the number of applications required to obtain a workable long-term academic position may seem preposterous, but these changing requirements for applicants are familiar to anyone who has obtained a PhD since the Great Recession of 2008. This competitive landscape has deeper roots than the last economic crisis; writing more than three decades ago, Rabinow (Reference Rabinow and Richard1991:66) pinpointed “an awareness . . . that standards have changed during the last thirty years, and the quantitative and qualitative demands for entry into the system are immeasurably higher now.”

These higher demands include increased overall productivity, higher national and international mobility, more time spent in precarious short-term contracts, and the investment of a greater amount of time and energy in applying for long-term positions. In their survey of early career researchers in European archaeology, for example, Brami et alia (Reference Brami, Emra, Muller, Preda-Bălănică, Irvine, Milić, Malagó, Meheux and Fernández-Götz2023:5) found that 52% of respondents who had obtained their PhD at least two years before the survey were on fixed-term contracts, whereas only 9% were in permanent positions. In their words, “the queue of eager post-docs hoping for a long-term appointment is getting longer, as is the average time spent in the ‘queue’” (Brami et al. Reference Brami, Emra, Muller, Preda-Bălănică, Irvine, Milić, Malagó, Meheux and Fernández-Götz2023:239). Ribeiro and Giamakis (Reference Ribeiro and Giamakis2023:10) emphasize that this demographic comprises an academic precariat that is essential to the functioning of universities but consists of a workforce perpetually “stranded between employment and unemployment.”

Junior scholars with faculty ambitions are therefore stuck in a double-bind, forced to funnel their energy into seemingly endless applications, for which they receive little to no feedback and which remain invisible on their CVs. As Dennis and colleagues (Reference Dennis, Docot, Gendron and Gershon2022:1) underscore, early career researchers are “supplicants”—“There is no way for applicants to point out that the job ads are taking too much time out of the scholarly community’s collective time bank.” Acknowledging the new reality that applying for academic positions is in and of itself a full-time job, a growing number of anthropology graduate programs are offering professionalization courses that cover the ins and outs of everything from crafting strong cover letters and CVs to performing well in long-list interviews and preparing teaching demonstrations. These courses can provide valuable training in the hidden curriculum of the academy, but the fact that job applications are so complicated that they require training to navigate suggests that more disciplinary attention should be paid to the “market” as a historically contingent set of cultural practices. As Rabinow (Reference Rabinow and Richard1991:71) maintains, “If we want ethical considerations to play a central role in the articulation of truth and power—and I think we do—then bringing such considerations into view is the necessary first step towards recognizing who we are today and setting out on the road to a better place.”

We argue that to understand the dynamics of hiring in academic archaeology, we must start at the beginning, with the job ad itself. Despite an abundance of recent work on who does and does not get hired into tenure-track positions in anthropology and archaeology, there is less scholarship on how those hires unfold. Research on hiring dynamics has amply demonstrated that where you get your PhD has an enormous impact on whether and where you get a tenure-track position (Kawa et al. Reference Kawa, Clavijo Michelangeli, Clark, Ginsberg and McCarty2019; Mackie and Rockwell Reference Mackie and Rockwell2023). But how about what you study? Are there topical, methodological, or regional specialties that are in consistent demand, or is there continual flux generated by intellectual fads, economic incentives, and political attention? Are job applications more demanding now than they were in the past, or is this a specious perception generated by the sheer volume of applications necessary to obtain a long-term academic position?

To answer these questions, this article explores the demand-side of the academic job market for archaeologists in the United States. Our study had two aims: (1) to determine if disciplinary trends could be discerned in the topical, geographic, and methodological foci of the positions advertised over a 10-year period; and (2) to investigate how requirements for applicants have changed over time.

Background

The academic job market is a source of uncertainty, for both job seekers and hiring committees. Job seekers must search for ads that are well matched to the skill sets and professional experiences that they have taken years to cultivate. Hiring committees must sift through tens to hundreds of applicants in the hope of finding a candidate that meets all of their needs and helps to realize their visions for their program and for the discipline. Finding the right candidate for the position—or the right position for the candidate—is akin to finding a needle in a haystack.

Among many scholars, there is also a perception that the academic job market has become increasingly competitive over the last three decades. Across the social sciences and humanities, there are fewer jobs available relative to the number of PhD graduates, and there are higher numbers of short-term positions relative to permanent positions (Bessner et al. Reference Bessner, Brenes, Susan, Emily, Michael, Henry D. and Chris2021; Brami et al. Reference Brami, Emra, Muller, Preda-Bălănică, Irvine, Milić, Malagó, Meheux and Fernández-Götz2023; Kawa et al. Reference Kawa, Clavijo Michelangeli, Clark, Ginsberg and McCarty2019; Kelsky Reference Kelsky2015; Mackie and Rockwell Reference Mackie and Rockwell2023). This market saturation has arisen in tandem with increasingly complex application requirements. Many job ads now solicit specific documents in addition to the cover letter and CV, such as teaching, research, and diversity statements. These additional documents must be tailored to each application, making the process of applying for jobs a full-time job of its own.

In American anthropology, the number of doctoral anthropology graduates has increased by about 70% over the past 30 years, but the number of new faculty positions has not increased proportionally (Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Cramb, Jones, Jones, Kling et al. Reference Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Justin Cramb, Jones and Kling2018). New faculty positions have dwindled, in part due to the removal of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) exemption in 1994, which prohibited mandatory retirement ages in higher education (Earle and DelPo Kulow Reference Earle and Kulow2015). When combined with the institution of tenure, the ADEA exemption allowed faculty to stay in their posts for as long as they liked. The median age for faculty in the United States now ranks among the highest for all professions (Kaskie Reference Kaskie2016). In tandem with the gradual de-investment in American higher education since the 1980s (Mirowski Reference Mirowski2011) and the aftershocks of the 2008 recession, the ADEA exemption has cultivated an environment where new lines are few and far between. Among biological anthropologists, for example, Passalacqua (Reference Passalacqua2018) found ratios ranging from 1.21 to 0.82 PhDs to job academic advertisements per year, concluding that academic positions in biological anthropology are barely at sustainable levels. This echoes findings from other fields. In biomedical sciences, there is one tenure-track position in the United States for approximately every 6.3 PhD graduates (Ghaffarzadegan et al. Reference Ghaffarzadegan, Hawley, Larson and Xue2015). In engineering, Larson et alia (Reference Larson, Ghaffarzadegan and Xue2014:747) have calculated that providing jobs for even 50% of PhD graduates would require the field to expand at an “improbable” rate of 14% per year. As they emphasize, “The system in many places is saturated, far beyond capacity to absorb new PhDs in academia at the rates they are being produced” (Larson et al. Reference Larson, Ghaffarzadegan and Xue2014:749).

PhD graduates who do not go directly into a tenure-track faculty position after graduation often go into a series of short-term appointments as part-time or limited-contract instructors, also known as “adjunct” or “contingent” faculty. The rising number of contingent faculty has long been a concern in US higher education (Trevithick Reference Trevithick2010). Data from the American Association of University Professors’ 2021–2022 faculty survey indicate that more than 60% of faculty positions in US universities were held by non-tenure-track full-time or part-time contingent faculty members (Colby 2022). Contingent faculty positions are precarious because they provide low or no health and retirement benefits, limited opportunities for professional development, and lower salaries relative to tenure-track positions. PhD graduates who have a sequence of short-term academic positions are often (1) disadvantaged financially due to low compensation combined with expensive and frequent relocation, (2) restricted socially due to isolation from family and community, and (3) limited professionally due to being ineligible for many decision-making roles at the universities at which they work (Platzer and Allison Reference Platzer and Allison2018).

Success in tenure-track job applications in archaeology is strongly determined by where applicants get their PhDs. Data from the 2014–2015 AnthroGuide publication of the American Anthropological Association shows that just 10 out of more than 100 US graduate programs produced more than 30% of the graduates hired into tenure-track faculty positions (Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Cramb, Jones, Jones, Kling et al. Reference Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Justin Cramb, Jones and Kling2018). Top-ranking programs are placing fewer than one in three graduates in tenure-track jobs (Mackie and Rockwell Reference Mackie and Rockwell2023). Similarly, a network analysis of 1,918 faculty holding tenured or tenure-track positions at PhD-granting anthropology programs in the United States in 2015 (including 506 archaeologists) found that just 15 graduate programs produced 53% of tenured and tenure-track positions (Kawa et al. Reference Kawa, Clavijo Michelangeli, Clark, Ginsberg and McCarty2019). This network analysis showed that programs with large endowments and widely cited faculty who hold prestigious awards produce the majority of tenured and tenure-track faculty.

Hiring bias predicated on the prestige of specific institutions and programs is not unique to anthropology. Targeted studies of sociology, communication, operations research, and industrial systems engineering show similar dynamics (Barnett et al. Reference Barnett, Danowski, Feeley and Stalker2010; Castillo et al. Reference Castillo, Meyers and Chen2018; Feeley and Tutzauer Reference Feeley and Tutzauer2021; Nevin Reference Nevin2019). Broader analyses comparing computer science, business, and history identify comparable patterns among disparate disciplines across the humanities, social sciences, and STEM fields. According to Clauset et alia (Reference Clauset, Arbesman and Larremore2015:4), “across disciplines, prestige hierarchies make the most accurate predictions of faculty placement.” The most recent comprehensive meta-analysis of faculty placement dynamics in the United States, which examined employment and doctoral education of all tenure-track faculty at PhD-granting universities, underscored the outsized impact of institutional prestige: 80% of faculty trained in the United States came from just 20% of institutions (Wapman et al. Reference Wapman, Zhang, Clauset and Daniel2022). Within anthropology, such studies draw attention to a central paradox: a discipline purportedly committed to fighting social inequalities continues to reproduce its own systemic inequalities through hiring practices that favor an elite minority of candidates with prestigious affiliations.

One way that some hiring committees are tackling prestige biases is by providing detailed instructions to applicants on how to prepare their application materials. In theory, detailed applications will allow the hiring committee to focus on evaluating the accomplishments of candidates across common categories rather than ranking based on prestige signals in a CV, such as a name of the applicant’s graduate program. This push for equity has resulted in job ads that are often highly prescriptive in the types of documents that applicants should submit. For example, in addition to a cover letter and CV, job ads in many fields now require applicants to submit short statements detailing their previous and future contributions to teaching, research, and diversity. In a comparison of job ads published in Anthropology News from 1999 to 2000 and 2019 to 2020, Gershon and Rachok (Reference Gershon and Rachok2021) noticed an increase in the number of materials requested from applicants. For example, there were twice as many job ads that requested writing samples in 2019–2020 than there were in 1999–2000, and there were nearly four times as many requested statements of teaching philosophy. In their review of the “worst job ads of 2021” Dennis and colleagues (Reference Dennis, Docot, Gendron and Gershon2022) reported job ads from Oberlin College and Grinnell College with particularly extreme requirements, which, respectively, requested nine and 13 documents from applicants. This high burden on applicants disproportionately favors people with more time and financial resources to prepare the required materials.

A notable requirement that has emerged in recent years is a diversity statement, in which the applicant describes their knowledge of, prior contributions to, and future goals for advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion. This requirement has been much debated largely due to an experiment between 2016 and 2022 at several University of California (UC) campuses that used diversity statements as the first cut for selecting candidates for tenure-track faculty positions (Soucek Reference Soucek2022). Only candidates with high-scoring diversity statements would have the rest of their application evaluated. This experiment generated intense and widespread public debate about the merits and risks of requiring and using diversity statements. These debates drew attention to the challenges of hiring faculty from underrepresented minorities and resulted in a variety of approaches to evaluating diversity, even leading some universities to omit requirements for diversity statements in job applications entirely (Guiden Reference Guiden2024). Although some time has passed since the UC experiment, institutional attitudes to diversity are likely to remain in flux for the foreseeable future. The 2023 Supreme Court decision in Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U.S. 181 (2023), which effectively ended affirmative action at American colleges and universities, along with the Trump administration’s 2025 targeting of DEI initiatives (Knox and Alonso Reference Knox and Alonso2025) foreshadow a shift in judicial and political currents that is reshaping institutional approaches to—and even definitions of—diversity. The 180-degree pivot over the past five years—from requiring carefully crafted diversity statements as a matter of course to abrupt and sweeping policy shifts rendering such documents obsolete—indicates that national and institutional commitments to diversity may be only as deep as the latest strategic plan.

Materials and Methods

Contextualizing the Archaeology Academic Jobs Wiki as a Data Source

Our primary data source is the Archaeology Academic Jobs Wiki. Originating in 2007, the wiki is a set of freely accessible web pages that anyone can edit anonymously or with a free user account. The site is hosted by Fandom, a for-profit company. The Archaeology pages are part of the Academic Jobs Wiki, which coordinates similar collaboratively edited resources for around 40 academic disciplines. The coordinators and contributors are nearly all anonymous or pseudonymous. Typically, contributors copy and paste all or some of the text of job ads into the wiki, from a variety of sources such as the Chronicle of Higher Education, Higher Ed Jobs, and university websites. Other contributors then edit the web page to add comments below an ad to share relevant information based on their experience in applying for that position. These edits result in annotations, such as a tally of how many people have applied, and the dates of events, such as requests for more materials, interviews, offers made, and rejection notices. Contributors also edit the page to ask and answer questions about the positions and the application process. These comments make the Academic Jobs Wiki not only a unique resource for timely and specific information for job seekers about positions they are interested in but also one of the most important internet resources for the academic job market. Because of its reputation for aggregating ads from diverse sources and rapidly updated information that is not available elsewhere, the Academic Jobs Wiki has become an authoritative data source for studies of hiring trends in academia (Musial and Holmes Reference Musial and Holmes2018; e.g., Passalacqua Reference Passalacqua2018) and a widely recommended resource for applicants (e.g., Lightfoot et al. Reference Lightfoot, Franklin and Beltran2021).

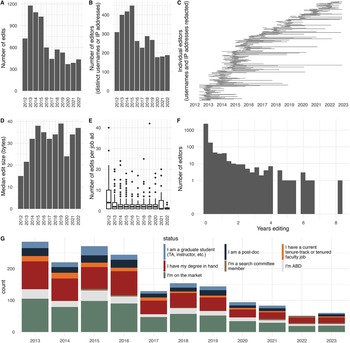

Collaboratively edited resources such as the Academic Jobs Wiki can be highly variable in the amount and type of editorial activity over time. It is important to characterize this activity to assess the reliability of the content as a source of information about the job market. The MediaWiki technology used by Academic Jobs Wiki creates a public record of every act of adding or removing text to any page in the Wiki (Barrett Reference Barrett2008). This technology allows us to measure the dynamics of editing activity over the 10 years of our study period (Figure 1). Every edit includes the author’s identity, recorded as either an IP address (a numerical address that includes information about the location of the user’s computer) or a username. Of the 2,824 unique editors in our sample, 91% used IP addresses rather than usernames, and geolocation analysis shows that 81% of IP addresses were based in the United States, indicating the Archaeology Jobs Wiki is primarily edited and visited by users in the United States. The number of edits and active editors roughly halved from 2013 to 2017, and then continued to gradually decline. Despite this downward trend, the size of individual edits slightly increased over time, and the number of edits per job ad remained relatively constant across our study period. The majority of editors were active on the site for a single day (n = 2241, 81%). There were 412 (15%) editors who were active for between one day and one year. Only 113 (4%) editors were active for more than one year, with eight years as the longest period any single editor was active on the Wiki. For those active for more than one day, the average duration of editorial activity was 4.6 years. This suggests that most of the editing activity on the Wiki reflects a single season of job searching. Editors with a longer history likely come from two groups: (1) job seekers participating in multiple seasons of job applications and (2) faculty on search committees posting multiple job ads. That said, inferring the number of editors from the number of IP addresses is complicated by the high mobility of job seekers. For example, one person could be represented by several IP addresses as they relocate from one city to another while working in a series of short-term appointments such as postdoctoral fellowships and adjunct teaching positions. This might result in an overestimation of the number of editors on the Wiki and underestimation of the duration of their editorial activity.

Figure 1. Visualizations of editing activity on the Archaeology pages of the Academic Jobs Wiki during 2013–2023: (A) total number of edits to each page (additions and deletions) per year; (B) number of unique editors, as represented by distinct usernames or IP addresses (recorded for editors without usernames), active per year; (C) active periods of individual editors: the black lines connect the date of the first and last edit of all editors that were active for three months or more; (D) typical size of each edit per year, either addition or removal of text; one word is roughly 4–6 bytes; (E) distribution of the numbers of edits per job ad for each year; (F) histogram showing that the majority of editors are only active on the site for less than one year; (G) breakdown of self-reported Wiki user categories for each year. (Color online)

Longer-term editors who represent job seekers active for multiple seasons reflect one of the underdiscussed realities of the academic job market in archaeology—time spent on that market. Previous research on professional trajectories in academic archaeology suggests that early career researchers have a limited shelf life. Mackie and Rockwell (Reference Mackie and Rockwell2023:5), for example, identify a hiring plateau that occurs around seven years after candidates defend their PhDs. However, too little time on the market also seems to have a negative effect on placement rates. According to Mackie and Rockwell (Reference Mackie and Rockwell2023:5), “Very few graduates obtain TT employment when they are all but dissertation (ABD) or even immediately after graduation.” These patterns are not restricted to the United States. In Brami et alia’s (Reference Brami, Emra, Muller, Preda-Bălănică, Irvine, Milić, Malagó, Meheux and Fernández-Götz2023) survey of 419 early career researchers in European archaeology, the likelihood of holding a permanent position shifted relative to time since PhD. Of the respondents who were one year or fewer than four years post-PhD, only 3% (3/116) held permanent positions. These numbers increased slightly for participants who had been on the market for five to seven years, with 14% (7/49) holding permanent positions; similarly, 18% (6/34) of respondents who were on the market for eight years or more held permanent positions.

This trajectory in archaeology—where there appears to be a temporal “sweet spot” post-PhD for obtaining permanent academic positions—dovetails with a larger meta-analysis of the career trajectories of PhDs from the humanities and humanistic social sciences. Main et alia (Reference Main, Prenovitz and Ehrenberg2019) used longitudinal Graduate Education Survey (GES) data from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to analyze the career trajectories of over 5,000 PhDs from disciplines in the humanities and humanistic social sciences at three time points: six months post-PhD, three years post-PhD, and eight years post-PhD. The proportion of surveyed doctorates in tenure-track or tenured faculty positions increased with time since PhD: 41% of the sample held a tenure-track position six months after defending, 64% held a tenure-track position three years after defending, and 68% held a tenure-track or tenured position eight years after defending. In keeping with broader patterns observed across the humanities and social sciences, the variable tenures of editors on the Archaeology Jobs Wiki may partially reflect the temporal patterns in hiring relative to job seekers’ time since PhD.

There seems to be a shift over time in the balance of editors who identify as job seekers versus search committee members, as indicated by the number of self-reporting users over time. Panel G of Figure 1 shows the data found on each page in a section labeled “current users,” where users can volunteer to update a table tracking the status of users. These data indicate that the total number of self-reporting users, from the values recorded at “How many people use the wiki?,” declined by 82% during the study period. At the same time, the proportion of users self-identifying as “search committee members” increased, from under 5% in 2014–2018 to over 14% from 2020 onward. This suggests that, over time, fewer job applicants have been contributing job postings and sharing information about their experiences, and search committee members have increasingly been posting job advertisements themselves. Overall, the Archaeology Academic Jobs Wiki is best understood not as a comprehensive and neutral archive of all jobs posted during the study period, but as a biased sample of the the jobs that early career applicants were most focused on applying for and sharing information about.

Methods of Data Collection and Classification

For each tenure-track job advertised on the Archaeology Academic Jobs Wiki between 2013 and 2023, we read the text and recorded the name of the hiring institution, the title of the position, and exact words and phrases from the ad about the topical, geographic, and methodological foci of the position into a Google form. The topical focus is what we understood as the intellectual core of the position. Examples of topical foci included environmental archaeology, public archaeology, and North American archaeology. The geographic focus is the region of the world about which the ideal candidate has scholarly expertise—for example, Southwest US, Mediterranean, or Asia and India. The methods focus is the data-generating subfield of archaeology mentioned in the ad. Examples of methods used in this study include archaeobotany, lithic analysis, and zooarchaeology. We also recorded the type and number of documents requested in each ad (e.g., cover letter; CV; statements on research, teaching, and diversity; syllabi; course descriptions; writing samples; transcripts) and how many names/letters of recommenders were requested in the ad.

After completing primary data collection, we studied the topical, geographic, and methods text of each ad. Following the approach of Ryan and Bernard (Reference Ryan and Bernard2003), we collaboratively and manually reduced the variation in the raw data into 10–15 categories appearing in at least 20 (for topics and geography) or 10 (for methods) job ads to simplify analysis and visualization. This means that some topics, such as gender (mentioned in six ads), do not appear in our results because of their rarity in the job ads. Full details of the category reduction, showing the mapping between exact phrases found in the job ads and the categories we used for our analysis, can be found in Marwick (Reference Marwick2025). Our final topic categories were American archaeology, Ancient Europe and Mediterranean, Archaeological science, Archaeological theory, Bioarchaeology, Complex societies, Digital archaeology, Environmental archaeology, Evolutionary anthropology, Indigenous and historical archaeology, North Mesoamerican archaeology, Pleistocene archaeology, and Public archaeology. Our geographic categories were Africa, Americas, Asia & India, Canada & Arctic, Europe, Mediterranean, Meso- & South America, Near East, Oceania, Midwest US, Northeastern US, Southeast US, Southwest US, and Western US. Our methods categories were Archaeobotany, Archaeometry, Bioarchaeology, Ceramic Analysis, Computational and Digital Archaeology, Geoarchaeology, Landscape Analysis, Lithic Analysis, Material Culture Analysis, and Zooarchaeology.

Individual ads could be recorded to have multiple or none of these topical, geographic, and methods foci, and some of the foci overlap. Some topics include geographic regions because this is how they are typically understood by archaeologists. For example, Mesoamerican archaeology is understood to refer to a specific time period and a specific geographic region. Similarly, we recorded digital archaeology as both a method (when a job ad also had a clearly distinct topical focus, such as historic archaeology) and a topic (when there were no other topics mentioned in the job ad). Although this polythetic approach results in categorical overlaps that can make the data challenging to interpret (Kuckartz Reference Kuckartz2014), in our view, this reflects the complex realities of how search committees express their needs when searching for new faculty. Acknowledgment of overlaps also produces new insights into hiring dynamics through revealing intersections between different foci.

The entire R code (R Core Team 2024) and data files used for all the analyses and visualizations contained in this article are openly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14798941 to enable reuse of materials and improve reproducibility and transparency (Marwick Reference Marwick2017). All of the figures, tables, and statistical test results presented here can be independently reproduced with the code and data in this repository. The code is released under the MIT license, the data as CC-0, and the figures as CC-BY, to enable maximum reuse.

Results

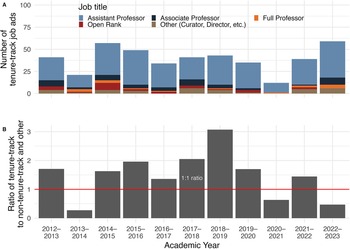

We collected data from 547 ads for tenure-track jobs in archaeology posted between 2013 and 2023. We focus our analysis here on the 431 ads for positions at US universities. Figure 2 shows the count of ads for each year; year refers to the year the job ad was posted. Table 1 shows the breakdown by different job types, ranks, and tenure status. Assistant professor jobs are consistently the most common title and rank of positions advertised, whereas open rank or full professor positions are the least frequent. The ratio of tenure-track to non-tenure-track positions is generally well above one; in other words, this dataset is dominated by tenure-track positions. Only academic year 2013–2014 had more non-tenure-track positions than tenure-track positions, which was followed by an upward trend peaking in 2018–2019 and then declining again into the present.

Figure 2. Visualizations of job ad numbers and ratios from the Archaeology pages of the Academic Jobs Wiki: (A) total number of job ads from US institutions posted to the Wiki for archaeology in each year, with colored sections showing the proportion of jobs by title and rank; (B) ratio of tenure-track to non-tenure-track positions over time; the red line indicates a 1:1 ratio of tenure-track to non-tenure-track positions; bars taller than that line indicate more tenure-track than non-tenure-track positions in that year. (Color online)

Table 1. Breakdown of Counts of Job Ads by Rank and Tenure Status.

Notes: Values in parentheses are for the United States only. Not all ads include unambiguous information about tenure status, so the sum of TT and NTT does not equal the sum of all jobs in all ranks.

a TT = tenure-track, United States only.

b NTT = non-tenure-track, United States and elsewhere.

Characteristics of the Hiring Institutions

Figure 3A shows the frequencies of hiring institutions in our data according to their Carnegie Classification, a framework for classifying US colleges and universities based on the types of degrees they award, the level of research activity, and their institutional focus (Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching 2001). Doctoral universities with high and very high research activity are by far the most active institutions hiring archaeology faculty. Associate’s colleges, also known as community colleges, rarely post job ads for archaeology faculty.

Figure 3. Visualization of the distributions of hiring institutions in the Archaeology pages of the Academic Jobs Wiki by type and geographic location: (A) frequency of hiring institution by Carnegie classification; (B) inset shows map of the United States, with the count of tenure-track job ads posted by all institutions in each state during the period 2013–2023. (Color online)

The geographic distribution of hiring institutions is shown in Figure 3B. California posted almost twice as many job ads as the next most active states. After California, the states that posted the most ads from 2013 to 2023 include New York, Texas, Pennsylvania, and Florida. These top five states correspond to the top five most populous US states, suggesting that rates of hiring are approximately proportional to population density. The top five states for job ads are also the five states with highest number of degrees awarded in anthropology (National Center for Education Statistics 2025). Similarly, the lowest counts of job ads were observed in states with the lowest populations: North Dakota, South Dakota, Alaska, and Nebraska. No institutions in Montana posted a job ad during this period. The implication here is that job seekers who are able to relocate to populous areas will have more employment options.

Geographic Trends in Job Ads Over Time

For each job advertisement, we identified and recorded the geographic regions in which applicants were required to have research expertise. Our analysis focuses on those locations mentioned in 20 or more ads. Overall, American locations dominate. Figure 4A shows that a single region of the United States—the Southwest—occurs in more job ads than every other part of the world except for the Mediterranean. The Southwest includes Arizona and New Mexico, with portions of California, Colorado, Nevada, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah. It is archaeologically significant as the home of the Ancestral Pueblo, Hohokam, and Mogollon peoples, who practiced irrigation agriculture and lived in relatively large settlements compared to other regions of the United States. The area was later occupied by the Navajo, Ute, Southern Paiute, Hopi, and Zuni—groups that had similarly high population densities (Griffin-Pierce Reference Griffin-Pierce2000). The Mediterranean is prominent because it is the region that is often mentioned in job ads focused on classical archaeology (i.e., archaeology of Bronze Age and Iron Age Italy and Greece).

Figure 4. Visualization of locations mentioned in job ads on the Archaeology pages of the Academic Jobs Wiki: (A) frequency of locations mentioned in the text of the job ads; (B) popularity of locations in job ads over time for locations that appear in 20 or more ads. Individual data points are shown, overlain by a locally weighted regression line for each location to indicate temporal trends. (Color online)

Demand for jobs focusing on the Americas has been generally high over the past decade, with a peak in 2019–2020 and a subsequent decrease. Demand for jobs focusing on Africa was very low until 2019–2020, peaking in 2020–2021. The proportion of ads with a geographic focus on the Mediterranean has varied substantially, peaking in 2016 and experiencing a nadir in 2019, showing an inverse pattern to the Americas. Asia and India, the Near East, and Europe rarely occur as a geographical focus in job ads at US institutions. Asia and India, Africa, and the Americas appear to be correlated with each other, whereas the Near East and Mediterranean are inversely correlated in an opposite trend.

Method Trends in Job Ads Over Time

Landscape archaeology, encompassing GIS and remote sensing, has remained prominent compared to other methods (Figure 5). The popularity of this suite of skills may reflect its demand by employers in the cultural research management (CRM) sector. Morgan (Reference Morgan2023) found that almost one-third of 599 jobs ads posted by CRM employers sought candidates with experience in GIS. Methods focused on a specific element of the archaeological record—such as lithic analysis, zooarchaeology, and ceramics—are among the least frequently mentioned in job ads. Instead, more popular methods are those that are relevant to multiple elements of the archaeological record (e.g., archaeobotany encompasses macroscopic and microscopic plant remains; bioarchaeology often includes skeletal analysis, isotopes, proteins, etc.).

Figure 5. Visualization of methods mentioned in job ads on the Archaeology pages of the Academic Jobs Wiki: (A) frequency of methods mentioned in the text of the job ads; (B) popularity of methods in job ads over time for methods that appear in 10 or more ads. Individual data points are shown, overlain by a locally weighted regression line for each location to indicate temporal trends. (Color online)

Landscape archaeology, although dominant, has fluctuated over the years and has been on a downtrend since 2018–2019. Computational and digital archaeology is the second most represented method, showing an overall increasing trend, particularly since 2020–2021. Archaeobotany shows a strong cyclical trend, rising, falling, and then rising again over our study period. Archaeometry and geoarchaeology have maintained a relatively low but steady presence in job ads, peaking in 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 and declining thereafter. Lithic analysis and zooarchaeology are also mentioned relatively infrequently in job ads and show an inverse correlation with each other after 2018–2019.

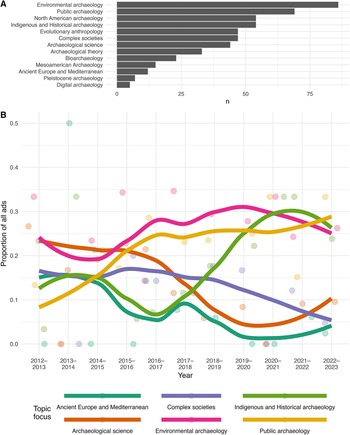

Topic Trends in Job Ads Over Time

The most frequently mentioned topic in this sample of job ads is environmental archaeology (Figure 6). This category encompasses such phrases as human-environmental dynamics, interaction between humans and their environments, environmental change, climate change, historical ecology, ecological knowledge, human ecology, and ecological systems. Public archaeology is the second most frequent topic overall; this category included phrases such as cultural resource management, cultural heritage, heritage studies, museum studies, human rights, community engaged, historic preservation, social justice, community-based, repatriation, and community-engaged archaeology. The least common topics in our sample are Pleistocene archaeology (e.g., human origins, hunter-gatherer archaeology) and digital archaeology.

Figure 6. Visualization of topics mentioned in job ads on the Archaeology pages of the Academic Jobs Wiki: (A) frequency of topics mentioned in the text of the job ads; (B) popularity of topics in job ads over time for topics that appear in 20 or more ads. Individual data points are shown, overlain by a locally weighted regression line for each location to indicate temporal trends. (Color online)

The years 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 show striking changes in the popularity of topics in job ads. Indigenous and historical archaeology (which includes archaeology of the African diaspora and enslaved people) became the most popular topic at this time, rising from being one of the least popular topics in the period 2012–2017. Conversely, archaeological science, which was popular from 2012 to 2017, was rarely mentioned in job ads during the years 2019–2021. Ancient Europe and the Mediterranean, an infrequently mentioned topic for the entire study period, virtually disappeared from job ads during the years 2019–2021. Mentions of complex societies in ads decreased at a steady rate after 2015–2016, whereas mentions of public archaeology rapidly increased during 2012–2013 to 2016-2017, then gradually increased up to the end of our study period. The topic of environmental archaeology remains high over time.

In our sample, job ads were more topically than geographically or methodologically rich—that is, ads were more likely to mention multiple topics than they were to mention multiple methods or geographic locations. A Kruskal-Wallis test indicated significantly higher richness in topics compared to richness of geographic locations or methods in job ads (χ2 (df = 1, N = 836) = 160.42, p = 9x10-37). Figure 7 shows topic co-occurrences in our sample. Indigenous and historical archaeology often occur in job ads with public archaeology and North American archaeology. Complex societies and environmental archaeology are frequently found in the same ads. Bioarchaeology, archaeological science, and evolutionary archaeology are another cluster of topics that frequently co-occur. Other topics are relatively isolated. For example, Pleistocene archaeology and digital archaeology rarely occur with other topics.

Figure 7. Heatmap of topic co-occurrence in job ads. (Color online)

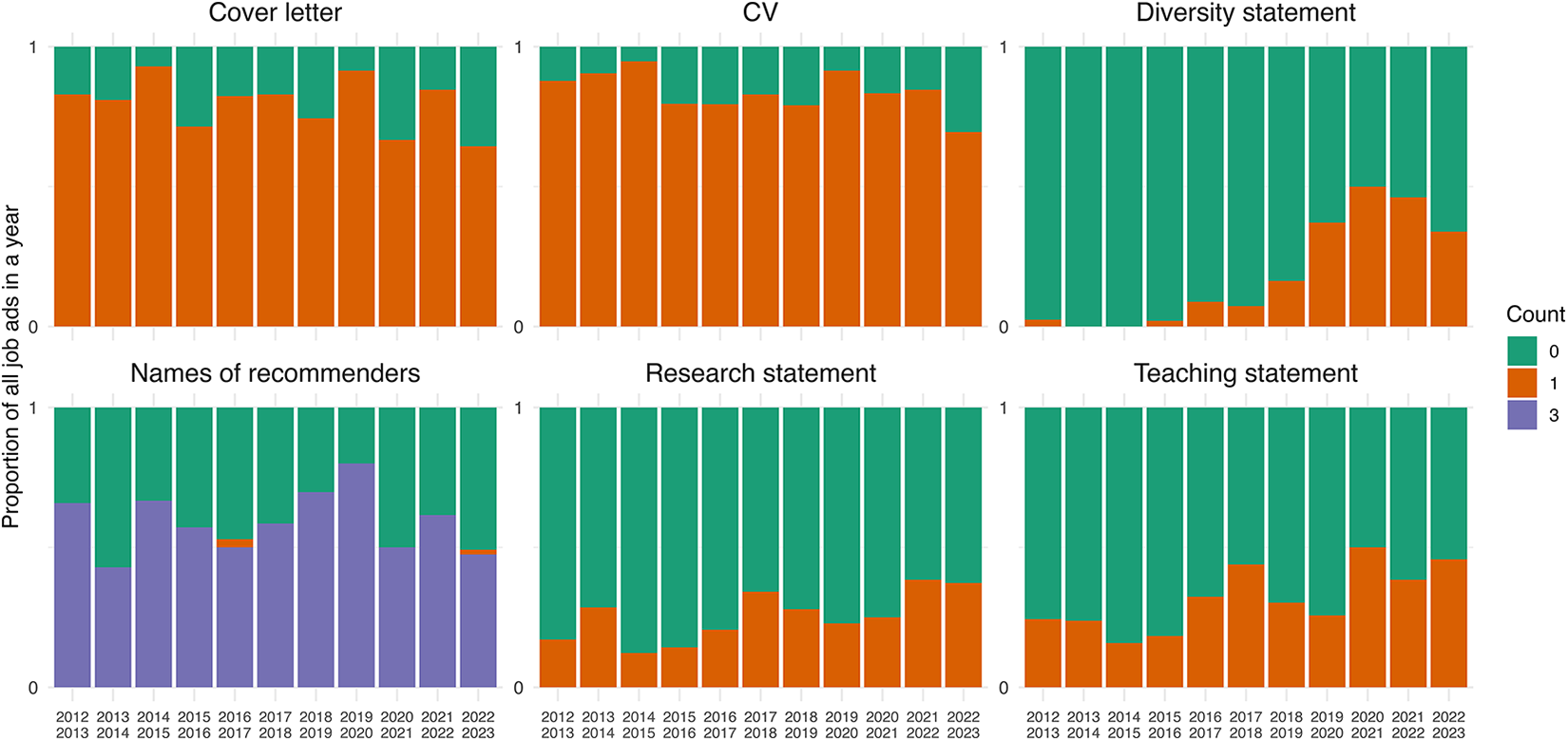

Instructions to Applicants Over Time

Over our 10-year study period, there have been substantial changes in the instructions to applicants in terms of the type and number of documents that are requested by the search committees (Figure 8). Requests for cover letter and CV decline slightly in more recent years, perhaps reflecting their status as a generic and expected component to submit without needing to be specifically requested. The requirement for a diversity statement is rare until 2019–2020, then it peaks around 2020–2021 and decreases up to the present. Requests for names of recommenders (either zero or three names, rarely only two names) reach a maximum in 2019–2020, then also decline for the remainder of the study period. The requirement for a research statement and teaching statement increases after 2015–2016 and becomes more frequent in job ads in more recent years. Requests for course descriptions, syllabus samples, teaching evaluations, transcripts, and writing samples are consistently low over time (not shown here).

Figure 8. Changing requirements in job ads over time. “Count” refers to the number of each item required. (Color online)

Discussion

Our study of a decade of tenure-track job ads in archaeology in the United States reveals diverse dynamics in the demand for specializations in topics, methods, and geographic focus and in the instructions to applicants. Although these dynamics are familiar to scholars actively seeking faculty positions, we believe this is the first time they have been quantified at such a large scale within archaeology. Trends in job ads reflect broader shifts in intellectual and practical priorities concerning archaeology, undergraduate education, and the process of hiring professors. The demand for archaeology faculty, indicated by the total number of tenure-track jobs, may be affected by a variety of factors.

Overall, we found more tenure-track jobs advertised each year than non-tenure-track jobs, with the exception of 2013–2014. The Wiki’s emphasis on tenure-track jobs runs counter to well-established patterns in the academic job market, which reflect that short-term and contingent positions are fast outpacing “the last good job[s] in America” (Aronowitz Reference Aronowitz2001). Research across anthropological subfields has shown that the number of tenure-track positions advertised within the discipline has also declined. Analyzing the job ads posted in Anthropology News in 1999–2000 versus 2019–2020, for example, Gershon and Rachok (Reference Gershon and Rachok2021) found that the number of tenure-track positions decreased by 25% between their two periods. Similarly, in his examination of jobs ads posted on the Biological Anthropology Academic Jobs Wiki between 2010 and 2017, Passalacqua (Reference Passalacqua2018:773) noted that 25% of the 474 ads posted were for adjunct or visiting staff. Though Passalacqua did not examine how the proportion of job types changed over time, he did underscore “a current diverging trend of decreasing academic job advertisements and increasing doctoral degrees in biological anthropology which could result in serious consequences for the discipline” (Reference Passalacqua2018:773). Such observations have a surprising longevity. Rogge (Reference Rogge1976:839) raised the alarm nearly half a century ago, warning of the “maladaptive” consequences of the exponential rate of disciplinary growth and the impending consequences for job seekers. The dwindling number of permanent academic positions is not a trend unique to anthropology—as of 2019, the American Association of University Professors documented a 36% increase in contingent positions over the preceding 15 years (Colby 2022), and as of 2020, contingent positions make up 61.5% of faculty positions in the United States (Colby 2022).

This discrepancy in our dataset—that advertisements for tenure-track positions dominate the Academic Jobs Wiki despite their increasing rarity in larger market—may be due to several factors. The first involves the more limited circulation of advertising for short-term positions relative to advertising for tenure-track jobs. Many of these short-term positions are not advertised nationally; instead, they are disseminated through local email lists and are filled by people close to the hiring department, such as recently graduated students. A second factor is bias in our data: given that most users likely are seeking a tenure-track job, non-tenure-track jobs may have been less frequently added to the Academic Jobs Wiki because they were peripheral to the goal of most users. This bias limits the reliability of our results on the ratio of tenure-track to non-tenure-track positions. Tellingly, Passalacqua’s (Reference Passalacqua2018:Table 2) examination of a similar wiki over a seven-year span showed a similar dominance of permanent positions—291 of 474 (63%) were for tenure-track hires at various levels. This congruence between subfields suggests that these patterns are a reflection of the Wiki, rather than of the market itself.

It is no secret that tenure-track jobs have traditionally been considered the “gold standard” of career outcomes for PhD students in the social sciences and humanities. As Kelsky (Reference Kelsky2015:11) outlines in The Professor Is In—her influential and best-selling guide for PhD students pursuing faculty careers—“Most ranking graduate programs still consider any PhD who doesn’t land a tenure-track job a failure or an aberration. . . . Graduate students absorb this value system and judge themselves harshly.” These rubrics of success have been common across the humanities and social sciences for over half a century. Evaluating the demise of the National Endowment for Humanities–funded “Program to ready PhDs for Careers in Business” (CIB), which aimed to facilitate humanities PhDs’ transition to the corporate world in the late 1970s, Franczak points to the dissonance between participants’ incentives and outcomes:

The biggest lesson we can take from CIB is also the most obvious. PhDs, especially in the humanities, want to be academics. The deep reservoir of adjunct or contingent faculty that elite and non-elite universities alike depend on for their courses is testament to this fact—as is the excellent scholarship so many adjuncts produce without department support. To pretend otherwise is disingenuous, and, as CIB shows, possibly dangerous, too [Bessner et al. Reference Bessner, Brenes, Susan, Emily, Michael, Henry D. and Chris2021:36].

The desire to pursue an academic career also characterizes more recent PhD cohorts, including those within archaeology. Brami et alia’s (Reference Brami, Emra, Muller, Preda-Bălănică, Irvine, Milić, Malagó, Meheux and Fernández-Götz2023:242) survey found that despite the long odds and professional precarity, 71% of their early career respondents wished to remain in academia. Overall, the obsessive valorization of permanent faculty positions in the face of a precipitous decline in available jobs is indicative of the potent combination of denial and delusion across academia. As Cefkin and Schwegler (Reference Cefkin and Schwegler2024) argue, “This asymmetry between the ‘ideal’ career path and the experiences of most graduates highlights the deep and growing chasm between the future that higher education institutions envision—and strongly incentivize—and what is actually happening.”

Returning to our results, the downward trend in tenure-track positions between 2013 and 2019 may be related to declining undergraduate enrollment in anthropology since 2013 (Cramb et al. Reference Cramb, Ritchison, Hadden, Zhang, Alarcón-Tinajero and Xianyan Chen2022). The big dip in 2020–2021 is explained by the hiring freezes at many institutions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused extreme disruption and uncertainty as universities focused on adapting to online instruction and assessment in an effort to minimize the spread of the virus (Woolston Reference Woolston2020). A survey of early career researchers in archaeology captures the impact of this dip, with 72.5% of respondents experiencing negative consequences on their careers due to the pandemic (Brami et al. Reference Brami, Emra, Muller, Preda-Bălănică, Irvine, Milić, Malagó, Meheux and Fernández-Götz2023).

The 2019–2021 period was also a major inflection point in the popularity of specific topics and regions in job ads. Calls for positions incorporating Indigenous and historical archaeology—and archaeology of the Americas—became far more frequent at this time, whereas archaeological science, complex societies, and the Mediterranean and Near East showed declines in popularity. Similarly, the number of job ads with a geographic focus on the Americas and Africa peaks from 2019 to 2021. These shifts in the topical and geographic foci of job ads were likely influenced by broader cultural movements, such as Black Lives Matter, protests about racial injustice, and efforts to amplify Indigenous voices (Dunivin et al. Reference Dunivin, Yan, Ince and Rojas2022; Flewellen et al. Reference Flewellen, Dunnavant, Odewale, Jones, Wolde-Michael, Crossland and Franklin2021; Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Odewale2020; Laluk et al. Reference Laluk, Montgomery, Tsosie, McCleave, Miron, Carroll and Aguilar2022). COVID-19 also negatively impacted Black, Indigenous American, and Hispanic communities, which had significantly higher infection and morbidity rates, drawing attention to racial and socioeconomic inequality in the United States (Mackey et al. Reference Mackey, Ayers, Kondo, Saha, Advani, Young and Spencer2021; Tai et al. Reference Tai, Shah, Doubeni, Sia and Wieland2021). The Black Lives Matter movement, dating back to 2013, intersected profoundly with the pandemic and the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis by a police officer in May 2020, three months after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic. Mass protests objecting to Floyd’s murder generated widespread concern about racial inequities and stimulated a broad interest in addressing systemic racial injustice.

Our data suggest that archaeology faculty at US universities participated in this movement by adjusting their hiring plans to prioritize recruiting archaeologists working on topics relevant to Black and Indigenous communities. Many universities may have hoped to hire Black and Indigenous archaeologists as part of their effort to tackle systemic racism. Due to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits hiring based solely on race or ethnicity, however, it is illegal for US universities use race or ethnicity as a primary factor in hiring. As a result, universities appear to have tailored the content of their job ads to focus on topics in which they expected Black and Indigenous researchers to be most numerous, in an effort to increase the likelihood that these researchers would be well represented in the pool of applicants.

This striking change in the topics and geographic foci of 2019–2021 occurred against a backdrop of several longer-term trends. Over the course of the study period, we documented a gradual decline in (1) topics such as complex societies and archaeological science, (2) the geographic foci of Mesoamerica and South America, and (3) methods relating to landscape archaeology. These trends are harder to explain given that we cannot link their origins to a historical event such as the COVID-19 pandemic. We might speculate that a growing preference for archaeological approaches that privilege agency-driven, subjective, and relational perspectives is one enduring legacy of debates in the 1980s and 1990s about processualism versus post-processualism (Fogelin Reference Fogelin2019; Hodder Reference Hodder1999; Johnson Reference Johnson2019). This trend might explain why archaeological science is showing a decline, with demand for methods for analyzing artifact materiality, ontology, and power displacing physical laboratory methods for technological, functional, and compositional analyses. Other factors relevant to this decline may include the increasing difficulty of obtaining research funding to support archaeological science research, such as laboratory facilities and instrumentation. A decline in interest in the archaeology of complex societies may reflect several themes that intersect with broader social changes—such as growing interest in Indigenous and nonstate actors in the past and an increased concern with climate change, environmental sustainability, and resilience—shifting attention away from the study of monumental architecture, elite societies, political hierarchies, and state systems.

Our data on the requirements for applicants support prior findings that the complexity of applications—and concomitantly, the labor required to apply for tenure-track jobs—has gradually increased over time. This trend is especially pronounced for assistant-professor positions, which make more demands on applicants than associate- and full-professor positions. Consistent with results from other studies (Gershon and Rachok Reference Gershon and Rachok2021), our project documented a growing demand for research and teaching statements. Demand for diversity statements shows a unique trajectory, peaking in 2020–2021 and declining up to the present. This may relate to the intersecting concerns about race, identity, and class inequalities emerging during the COVID-19 pandemic, which seem to have reached a peak in 2020–2021 and then declined over time, resulting in jettisoning requests for diversity statements as the most urgent period of the pandemic moves into the past. Another factor here may be the debates surrounding the experiment with diversity statements in hiring at some UC campuses from 2016 to 2022. Some universities that previously required a diversity statement dropped that requirement after 2022 (Guiden Reference Guiden2024). In our data, we observed a reversal of the diversity statement requirement at four universities. Those schools posted job ads prior to 2022 that did require a diversity statement, and they also posted an ad in 2022 that did not require one.

In recent years, one bright spot for applicants is the decline in requests for names of recommenders in the initial application. This may be a response to recent criticisms of the burden on the applicant of preparing numerous complex job applications (e.g., Dennis et al. Reference Dennis, Docot, Gendron and Gershon2022). In recognition of this burden—not only on applicants but also on colleagues writing letters of recommendation repeatedly to support applicants—many hiring committees now follow the recommendations of Dennis et alia (Reference Dennis, Docot, Gendron and Gershon2022) in only requesting names and letters of recommendation at later stages of the hiring process, if at all. Showing sensitivity to this burden, in 2020, the American Anthropological Association issued guidance to academic departments that letters of recommendation should not be requested in the initial application, but should only be required from short-listed candidates (American Anthropological Association 2020; Youngling and Gershon Reference Youngling and Gershon2020).

A key limitation of our research is that it does not include an analysis of the academic profiles of those who were eventually hired based on this sample of job ads. Our results reveal collective aspirations for the future of the field but only from those writing the job ads—typically, faculty who are securely employed as tenured professors serving on hiring committees at US colleges and universities. Our results do not show how these aspirations worked out in the topical and geographic foci of the people who were actually hired for these positions. Future work should consider interviewing faculty hired during our study period to match up scholars with the ads to which they applied. If the successful applicants can be identified, then we could analyze the fit between the details of the job ad and the applicant’s research. Such an analysis would allow us to assess how effective job ads are for driving change in the discipline by setting not only the topics of courses that will be taught in undergraduate and graduate curricula but also research that will be supported by universities. We also recognize the possibility that the Academic Jobs Wiki does not capture all available positions and likely overrepresents certain types of institutions. Future work should evaluate these biases by comparing entries on the Wiki to other sources of information about the academic job market, such as the American Anthropological Association’s AnthroGuide or data collected directly from universities.

Conclusion

The data introduced in this article were initially collected and analyzed in the spring and summer of 2024, and the manuscript was drafted in the autumn of 2024. Between submitting the manuscript and receiving our initial round of revisions in April 2025, the landscape of US higher education has shifted dramatically. The first hundred days of the new federal administration focused on instilling a climate of “economic precarity and legal uncertainty” across the sector through a cthuluesque strategy that included withholding federal funding for colleges and universities, decimating the Department of Education, revoking international student visas, and attacking Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives as “unconstitutional” (Knox and Alonso Reference Knox and Alonso2025). This deliberately destabilizing “flood the zone” approach (Broadwater Reference Broadwater2025) shows no signs of abating. In April 2025, the US president signed an executive order to overhaul the higher-education accreditation system (White House 2025), signifying the administration’s continued commitment to align higher-education institutions with its ideological agenda.

Such challenges to the autonomy and self-governance of higher education are particularly remarkable given that many architects of the current administration hold degrees from the very institutions they are attempting to dismantle. These include Donald Trump (Wharton School of Business), J. D. Vance (Yale Law School), Chris Rufo (Georgetown), Stephen Miller (Duke University), and Peter Hegseth (Harvard Kennedy School). Reviewing the profiles of the board of trustees for the Heritage Foundation—the conservative think tank that generated Project 2025 (Dans and Groves Reference Dans and Steven2023), the report that has been used as a blueprint for feeding US higher education “into a woodchipper” (Kunder Reference Kunder2025)—is also illustrative. Two-thirds of the trustees on the Heritage Foundation board have advanced degrees, and one-third have doctoral degrees from institutions such as Harvard, Oxford, the University of Colorado, and the University of Texas. Lindsey Burke, who authored the Project 2025 chapter on the Department of Education, holds a PhD from George Mason University. Such career trajectories are a testament to the elite chiasmus that decries the merits and value of higher education while leveraging the credentials granted by elite institutions for professional gain. As Ho (Reference Ho2009:41) notes regarding the parallel systems of credentialing that undergird the ideology of “smartness” among Wall Street investment banks, playing the role of “master of the universe” requires both “especially strong doses of self-confidence and institutional legitimation.” Even archaeology is susceptible to the power and pull of such prestige hierarchies, which influence everything from hiring networks (Kawa et al. Reference Kawa, Clavijo Michelangeli, Clark, Ginsberg and McCarty2019; Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Cramb, Jones, Jones, Lulewicz et al. Reference Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Justin Cramb, Jones and Lulewicz2018) to publishing decisions (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Gjesfjeld and Chrisomalis2021) to research design (Wobst and Keene Reference Wobst, Arthur, Gero, Lacy and Michael1983).

To echo Paul Farmer (Reference Farmer2004:316), “All this is both interesting and horrible.” Contextualizing our job-ad findings in this sociopolitical tumult provokes a suite of new questions about academic futures. Many archaeologists now have urgent concerns about what topics are likely to be “safe” and to lead to secure ongoing employment, considering the current political and funding landscape. Will states with stronger cultural and environmental regulations offer more stability in employment, and if so, which states are likely to be the safest? These are legitimate and crucial questions, but predicting the future goes beyond the scope of our examination of the past decade of hiring dynamics in academic archaeology. Extrapolating future trends is inherently uncertain, especially in a mercurial political and economic landscape that is experiencing tectonic shifts in bureaucracy, organization, and funding on a near-weekly basis. Our study does, however, point to at least four findings that have implications for the next 10 years of hiring, despite the turbulent political climate of 2024–2025.

First, the macroeconomic uncertainty induced by the increased tariffs introduced in early 2025 is likely to have both short-term and long-term implications that slow economic growth (Schneider Reference Schneider2025), with effects that will seep into the higher-education sector. The last two periods of major economic upheaval in the United States—the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic—had pronounced and negative consequences for colleges and universities. These consequences were visible even within academic archaeology. Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Cramb, Jones, Jones, Lulewicz et alia (Reference Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Justin Cramb, Jones and Lulewicz2018), for example, show the precipitous decline in the proportion of PhDs hired into tenure-track anthropology departments after the last recession (see the steep decline between 2007 and 2009 in Figure 5), resulting in the “increased use of [non-tenure-track faculty] by higher-education institutions, and more anthropology doctorates entering the workforce” (Reference Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Justin Cramb, Jones and Lulewicz2018:12). As our results demonstrate, during academic year 2020–2021, only 12 tenure-track jobs in archaeology were posted on the Academic Jobs Wiki, a 70% decrease relative to the mean of 39 per year posted during our survey period (Table 1). Knox and Alonso (Reference Knox and Alonso2025) highlight the hiring freezes and program cuts that came into effect just four months into the new administration. Given past patterns, it is likely that increased tariffs will result in tenure-track positions in academic archaeology becoming even more scarce, and faculty and students should prepare for this. Whether this signals a death knell for the discipline or an opportunity for reenvisioning and reconfiguring the field (Cefkin and Schwegler Reference Cefkin and Schwegler2024) is up for debate.

Second, our results show that hiring in academic archaeology is responsive to larger cultural and political shifts. The increased popularity of Indigenous and historical archaeology from 2019 to 2021 reflects the prominence and impact of movements such as Black Lives Matter and an increased interest in conversations about race and national history. The continual responsiveness to current events revealed by our analysis of archaeology job ads demonstrates that our narratives of the past are entangled in the social and political milieu in which we work. This finding is consistent with previous work: Trigger (Reference Trigger1984) outlined how archaeological research programs are shaped by national histories, whereas Soffer (Reference Soffer, Gero, Lacy and Michael1983), Blakey (Reference Blakey, Gero, Lacy and Blakey1983), Meltzer (Reference Meltzer, Gero, Lacy and Blakey1983), and Wilk (Reference Wilk1985) have interrogated the entanglement of identity, ideology, national history, politics, and archaeology across space and time. Our study of job ads shows an active effort by archaeologists to take control of interpreting the past, offering an example of how disciplinary choices can shape archaeological research programs. That said, in early 2025, many researchers had their work disrupted by cancellations of funding from the National Science Foundation if their projects contained certain keywords (Mervis Reference Mervis2025), and others were told to cease activities if their projects contain keywords such as “cultural relevance,” “institutional,” “historically,” “socioeconomic,” and “systemic” (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Dance and Achenbach2025). This unprecedented keyword vetting suggests that future topical shifts in archaeological research may be as much an individual response to top-down funding pressures (Wobst and Keene Reference Wobst, Arthur, Gero, Lacy and Michael1983) as a disciplinary response to the current historical moment.

Third, the high chronological resolution of our analysis relative to previous studies of disciplinary trends (e.g., Lyman Reference Lyman2010) shows that the rise and fall of some of the foci we observed span relatively short periods of time. This limits the predictive power of our results and has implications for prospective graduate students and their mentors. A topic that is growing in popularity as students begin their PhD may have peaked and be in decline before they graduate. Methods seem to have a much lower frequency of change in popularity relative to topical and geographic foci. One implication of this finding is that a graduate student who has invested in developing technical expertise in a method during their studies—in addition to a topic and region—might be less vulnerable to the vagaries of the job market than a student without a distinct area of technical expertise in generating data from material records of past human behavior.

Finally, our work also reveals the market forces that shaped the early careers of the next generation of academic mentors. Assistant and associate professors who experienced the academic market as job seekers themselves between 2012 and 2023 probably anticipate that their students will need publications, external grants, teaching experience, interview preparation, extensive and tailored portfolios of job markets, and the ability to spend many years on the market before obtaining a permanent position—if they obtain one at all. This raises the questions of (1) whether mentors’ experiences with a market defined by a recession and a pandemic will be enough to guide their students through the volatility of the next decade, and (2) how they should update their programs to prepare their graduates for success.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the anonymous contributors to the Academic Jobs Wiki, without whose efforts to collect and organize hundreds of job ads this article would not exist. To those of you who contributed to the Wiki but did not obtain a tenure-track job and/or decided to pivot to another industry, we hope this article shows that your time on the Wiki was not wasted. Your efforts have helped contribute to more accurate expectation setting for future generations of archaeologists.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant funding from any funding agency or from commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14798941.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.