1. Introduction

The Cambrian Period (ca. 538–487 Ma) and its primarily Early Cambrian ‘Cambrian evolutionary radiation’ (CER) was a very significant interval with the origin and diversification of eumetazoan protists, fungae, animals and plants. A precise Ediacaran–Cambrian geochronology devised over the last three decades now helps determine the timing and rates of Ediacaran–Cambrian biotic diversification and replacements; ecologic turnovers; marine chemostratigraphic and atmospheric composition changes; sedimentary accumulation and cyclicity/alternations, including astrochronologic successions; and eustatic/epeirogenic-driven sea level changes. This work has included analysis of volcanic zircons from the Avalonia palaeocontinent (Fig. 1) and detrital zircon work in southwestern Laurentia (review in Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a and references cited).

Figure 1. Terminal Ediacaran–Lower Ordovician depositional sequence stratigraphy and geochronology on marginal and inner platforms of Avalonian southern New Brunswick and SE Newfoundland. Avalonian dates are in red; asterisks mark horizon and location of U-Pb dates on right. West–east cross-section of terminal Ediacaran–Lower Ordovician trans-Avalonian depositional sequences from Burin Peninsula (marginal platform) and east–west through Trinity–Conception bays (inner platform) and north–south across southern New Brunswick (marginal platform) to Cradle Brook inlier (inner platform; Fig. 2). Stratigraphy from Landing (Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996; also Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022). Lowest occurrence (LO) of trilobites in Avalonia (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Brasier and Bowring2013) and Siberia and Morocco (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Schmitz, Wotte and Kouchinsky2021); early origin of trilobites (Paterson et al. Reference Paterson, Edgecombe and Lee2019) preferred over c. 521 Ma date of Holmes & Budd (Reference Holmes and Budd2023; e.g., Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Schmitz2024). U-Pb zircon dates: 483 Ma (Cape Breton Island, Landing et al. Reference Landing, Bowring, Fortey and Davdek1997); 486.8 Ma (North Wales, Landing et al. Reference Landing, Bowring, Davidek, Rushton, Fortey and Wimbledon2000); 488.7 Ma (North Wales, Davidek et al. Reference Davidek, Landing, Bowring, Westrop, Rushton and Adrain1998); 494.36 Ma (Arizona, U. S., Cothren et al. Reference Cothren, Farrell, Sundberg, Dehler and Schmitz2022 revises Peng et al. Reference Peng, Babcock, Ahlberg, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020 of 497 Ma estimate); 503 (Germany, Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Buchwaldt and Bowring2015); 507.91, 507.67, 506.25 Ma (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b); 508 Ma (New Brunswick, Landing et al. Reference Landing, Davidek, Westrop, Geyer and Heldmaier1998, recalculated by Schmitz Reference Schmitz, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012); 507.91, 514.45 Ma (England, Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Williams, Condon, Wilby, Siveter, Rushton, Leng and Gabbot2011); 517.2 Ma (England, Williams et al. Reference Williams, Rushton, Cook, Zalasiewicz, Martin, Condon and Winrow2013); 526.43 (South China, Yang et al. Reference Yang, Bowyer, Condon, Li and Zhu2023); 520 Ma and 531 Ma (New Brunswick, Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton, Álvaro, Barr, Jensen, Johnson, Palacios, Van Rooten, White, Nance, Strachan, Quesada and Lin2023); 528 Ma (New Brunswick, Isachsen et al. Reference Isachsen, Bowring, Landing and Samson1994, recalculated by Schmitz Reference Schmitz, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012); 538 Ma (Namibia, Linnemann et al. Reference Linnemann, Ovtcharova, Schaltegger, Gärtner, Hautmann, Geyer, Vickers-Rich, Rich, Plessen, Hofmann, Ziegler, Krause, Kriesfeld and Smith2019, reevaluated by Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Schmitz, Wotte and Kouchinsky2021). Abbreviations: Bk., Brook; Cham., Chamberlain’s; D., depositional; Dap. St., Dapingian Stage; Formation, Formation; Group, Group; LI, Long Island Member; *LO, lowest occurrences of trilobites; M, Middle; Mbr., Member; O., Ordovician; seq., sequence; W.C.C., West Centre Cove. Stratigraphy: Ratcliffe Brook Group of Landing (Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996); designations ‘Glen Falls,’ ‘Handren Hill,’ ‘King Square,’ ‘Reversing Falls,’ ‘Silver Falls’ formations of Tanoli & Pickerill (1987) and Álvaro et al. (Reference Álvaro, Johnson, Barr, Jensen, Palacios, Van Rooyen and White2023) follow usage of Landing (Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996) and Landing et al. (Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022, Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b); ‘Forest Hills Formation’ (Tanoli & Pickerill 1987) is Fossil Brook Member and Manuels River Formation (Landing Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996; Landing & Westrop Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998a, b; Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b; Westrop & Landing Reference Westrop and Landing2025; this report); ‘Miaoling.,’ is ‘Miaolingian,’ see evaluation of diachroneity of this series I Landing et al. (Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b). Diamictite detailed by Landing & MacGabhann (Reference Landing and Macgabhann2010) and Landing et al. (Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b).

The Cambrian is divided globally into four series and ten stages, with a number of these units now formally defined (e.g., Peng & Babcock Reference Peng and Babcock2011; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Babcock, Ahlberg, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020). The Middle Cambrian Subsystem and ‘Miaoliningian’ Series (see ‘Miaolingian’ evaluation in Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a) featured the end of the CER and is bracketed by the subsequent extinction and replacement of Lower Cambrian olenelloid and redlichioid trilobites and a later overturn of polymeroid trilobites at the onset of the SPICE carbon isotope chemozone (e.g., Sundberg et al. Reference Sundberg, Zhao, Yuan and Lin2011, Reference Sundberg, Karlstrom, Geyer, Foster, Hagadorn, Mohr, Schmitz, Dehler and Crossey2020; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Brasier and Bowring2013; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Babcock, Ahlberg, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020).

This uncertainty in ages of these intervals is shown by dates that once bracketed the ‘Miaolingian’ at 509 Ma and 497 Ma (e.g., Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Finney, Gibbard and Fan2013, revised 2018; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Babcock, Ahlberg, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020), but have proven to be significantly ‘too old.’ Refined U-Pb analyses and biostratigraphic and chemostratigraphic correlations now show a base of the Middle Cambrian at ca. 507.67–506.34 Ma in Avalonian SE Newfoundland and a top at 494.5 +0.67/-0.58 Ma by Bayesian analysis of Avalonian volcanic and Laurentian detrital zircons (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b; Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Cothren, Schmitz, Sundberg, Dehler and Landing2023, 2025; Fig. 1). However, few uncontested dates are known within the Middle Cambrian despite important sea-level changes and development of the DICE carbon excursion (i.e., DrumIan Carbon Excursion) with its potential for interregional correlation. [As used herein, Lower/Early, Middle/Middle, Upper/Late Cambrian are precisely defined subsystems/subperiods proposed to replace the undefined, subsystem-level terms ‘lower’/‘early,’ ‘middle’/‘middle,’ and ‘upper’/’late’ of many reports (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Schmitz, Wotte and Kouchinsky2021).]

This report continues a synthesis of terminal Ediacaran–Ordovician geochronology of Avalonia from sites in SE Newfoundland, southern New Brunswick and North and South Wales in the context of sequence stratigraphy and biostratigraphy (e.g., Landing Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022, Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a, Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotteb). We document a new high precision chemical abrasion isotope dilution thermal ionization mass spectrometry (CA-IDTIMS) U-Pb zircon age on a Middle Cambrian bentonite now correlated into the Avalonian biostratigraphic zonation (Westrop & Landing, Reference Westrop and Landing2025). This bentonite is regionally extensive in southern New Brunswick. It lies a short stratigraphic distance above an interformational unconformity marking the abrupt, long-term (ca. 26 Ma) change from oxic to strongly dysoxic/anoxic deposition and the green–black mudstone transition in Avalonia and Baltica (Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023; Fig. 1).

2. Avalonian New Brunswick field area

2. a. Avalonia as a terrane

The Avalonian terrane forms the SE margin of the Appalachian–Variscan mountain belt in coastal NE North America, southern Britain (Wales–southern England) and central Belgium–northern Germany. Avalonia was a terminal Ediacaran–Middle Paleozoic ribbon continent that collided with Laurentia and Baltica in the formation of Laurussia in the Devonian Acadian–Caledonian orogeny. Avalonian successions are exposed in fault-bounded inliers, incorrectly termed ‘terranes’ in many reports (e.g., Woodcock Reference Woodcock, Rushton, Brück, Molyneux and Woodcock2011; Rees et al. Reference Rees, Thomas, Hughes, Hughes and Turner2014; Álvaro et al. Reference Álvaro, Johnson, Barr, Jensen, Palacios, Van Rooyen and White2023), in northeastern North America and southern Britain (discussed in Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022; Landing & Geyer Reference Landing and Geyer2023, Reference Landing and Geyer2025)

Avalonia is defined by uppermost Ediacaran–Ordovician successions dominated by marine siliciclastics with minor bedded carbonates and thin volcanic ashes with local volcanic edifices (e.g., Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022, review with references). These cover sequence successions have a distinctive sequence stratigraphic architecture (Fig. 1) and are unconformable on Neoproterozoic and older basement (Keppie Reference Keppie, Gee and Sturt1985; Landing Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a, Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotteb; Fig. 1). The terrane is structurally bounded by fault-juxtaposed, coeval marine successions. To the SE, the Meguma zone is brought to Avalonia. What is regarded herein as a problematical ‘Gander Zone’ to the NW corresponds to the traditional Appalachian ‘central mobile belt’ (Williams Reference Williams1979) and consists of a number of terranes with the SE margin of “Ganderia” comprised of areas referable stratigraphically to Avalonia (e.g. review and references in Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022; Fig. 2). The origin of Avalonia is controversial. The ‘Perigondwana model’ emphasizes the Precambrian basement and regards Avalonia as a fragment detached from Gondwana by the Early Ordovician (e.g. Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Nance, Keppie, Dostal, Wilson, Houseman, McCaffrey, Doré and Buiter2018, Reference Murphy, Nance, Wu, Hynes and Murphy2023, and references therein). The ‘Peribaltic model’ emphasizes the cover sequence, which is the fundamental basis for definition of any terrane (e.g., Jones et al. Reference Jones, Howell, Coney, Moniger, Hashimoto and Uyeda1983; Howell & Howell Reference Howell and Howell1995). The cover sequence unconformably overlies a basement collage of Proterozoic blocks (Keppie Reference Keppie, Gee and Sturt1985; Landing Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022). This basement may have formed close to Baltica (e.g., Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Collins, Murphy, Gutierrez-Alonso and Handa2016; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022; Beranek et al., Reference Beranek, Hutter, Pearcey, James, Calum, Lagor, Pike, Goudie and Oldham2023) by accumulation of crustal and oceanic fragments along the Avalonian transform fault (Atf). By this model, a modern analog of Avalonia is the North Scotia Ridge (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022).

Figure 2. Avalonian successions, includes Meguma zone, (in black) in Maritime Canada showing marginal platform (including Little River belt) and inner platform inliers. Abbreviations: all., allochthon; au., autochthon; BHr, Beaver Harbour; CaI, Caton’s Island; CBr, Cradle Brook; DBA, Doctor’s Brook allochchon; Is., Island; MCA, Malignant Cove authochthon; ME, Maine.

2. b. Avalonian marginal platform and “Caledonian terrane” in southern New Brunswick

The central part of the Avalonian belt features relatively shallow marine shelf facies termed the ‘Avalon platform’ (Rast, O’Brien & Wardle Reference Rast, O’Brien and Wardle1976). However, this part of the terrane was not a stable ‘platform’ during cover sequence deposition because of persistent terminal Ediacaran–Ordovician strike-slip activity. The assertion that Avalonia during this time interval featured a rift regime in SE Newfoundland and southern New Brunswick, with remarkably small half-grabens aligned in a linear arrangement, has no modern analogue (see Álvaro Reference Álvaro2021; Álvaro et al. Reference Álvaro, Johnson, Barr, Jensen, Palacios, Van Rooyen and White2023; Álvaro & Mills Reference Álvaro and Mills2024). Indeed, the wedge-shaped lithosomes expected in a rift/half graben regime (Álvaro et al. Reference Álvaro, Johnson, Barr, Jensen, Palacios, Van Rooyen and White2023) are absent in southern New Brunswick and all other Avalonian cover successions. In southern New Brunswick by comparison, every successive terminal Ediacaran–Cambrian stratigraphic unit has long been known to blanket the region from the Saint John area, NW across the Long Reach (Fig. 2, locality CIs) and SE to Beaver Harbour (Hayes & Howell Reference Hayes and Howell1937; Alcock Reference Alcock1938; Landing & Westrop Reference Landing and Westrop1996, 1988a, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westropb; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Johnson and Geyer2008; Figs. 1, 2).

The rift/half graben model is also countered by well documented evidence of a strike-slip regime shown by successive NNE-trending, fault bounded depocentres in SE Newfoundland (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson1962; Landing & Benus Reference Landing and Benus1988a, Reference Landing, Benus, Landing, Narbonne and Myrowb; Landing Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996). These depocentres progressively migrated120 km across SE Newfoundland in the terminal Ediacaran–middle Early Cambrian (Smith & Hiscott Reference Smith and Hiscott1984; Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson1962; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022). Such depocentre migration is consistent with strike-slip in a transtensional regime along a transform fault (Steele & Gloppen Reference Steel, Gloppen, Balance and Riding1980; Noda Reference Noda and Itoh2013).

This SE depocenter migration followed transpressional uplift of the oldest depocenter, or marginal platform, that forms the NW margin of North American and British Avalonia (in modern coordinates). The marginal platform has the oldest cover sequence units, which extend across southern New Brunswick (i.e., Rencontre red beds, Chapel Island shallow marine sandstones, and Random tidalite/wave dominated quartz arenites; Figs. 1, 2). This terminal Ediacaran–middle Lower Cambrian cumulative deepening–shoaling vertical succession compises the Avalonian marginal platform in New Brunswick (Saint John, Brookville, Little River areas; Fig. 2); SE Cape Breton Island; Burin Peninsula, SE Newfoundland and North Wales (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022). Thus, there is no need as in many reports need to assign SE New Brunswick to a ‘Caledonian terrane’ (e.g., Álvaro et al. 2022), SE New Brunswick is simply part of the marginal platform of the Avalonia terrane (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022; Fig. 2).

The white quartzites (Random and synonyms) transgress out of the marginal platform and comprise the oldest cover sequence unit to the SE on the Avalonian inner platform (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Westrop and Bowring2014). The Avalonian inner platform, which comprises Rhode Island; SE Massachusetts; the Bonavista–Bonavista peninsulas, SE Newfoundland; South Wales; and England, comprises a tiny coastal outcrop in southern New Brunswick (e.g., Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022; Figs. 1, 2, locality CBr).

2. c. Manuels river formation in southern New Brunswick

The field area of this report (Fig. 2, red arrow) NE of Saint John is a (likely fault-bounded) Cambrian inlier on the Proterozoic with isolated Middle Cambrian exposures (Hayes & Howell Reference Hayes and Howell1937; Alcock Reference Alcock1938; Landing & Westrop, Reference Landing and Westrop1996, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998a; Landing et al., Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022, Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b; Landing, Westrop & Geyer, Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023; Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Field localities in southern New Brunswick with Rte. 111 ash: Airport Access Road North (AARN), 45° 20’ 43.68” N, 65° 54’ 41.17” W, long road cut on east side of Rte. 111, 1467–1640 m north along road from intersection Rte. 111 and Loch Lomond Road; Loch Lomond (LoL) road cut, 45° 22’ 2.01” N, 65° 51’ 32.27”, on south side Barnesville Road (Rte. 820), immediately west of driveway into No. 306 Barnesville Road; Porter Road (PoR), 45° 25’ 52.44” N, 63° 37’ 29.76” W, in drainage ditch on south side of Porter Road 2 km west of intersection Porter Road and Rte. 111 (St. Martins Road). Abbreviations: ME, Maine; N.S., Nova Scotia’ Que, Quebec; P. E. I., Prince Edward Island.

The trilobite-bearing Middle Cambrian of southern New Brunswick has long been known to consist of two parts (Fig. 4). The lower is a thin (to 12 m) greenish mudstone with bedded and nodular limestones and upper greenish mudstone. This interval was early referred to the ‘Fossil Brook formation.’ The upper part is a poorly exposed and biostratigraphically subdivided black mudstone (i.e., ‘Porter Road formation’ with a ‘Paradoxides abenacus shale’ and overlying ‘Goniagnostus confluens shale’ and a ‘Hastings Cove formation,’ which in a confusing description, includes a successive ‘Gonioagnostus nathorsti shale’ and ‘Triplagnostus lomondensis shale’) (Hayes & Howell Reference Hayes and Howell1937; Alcock Reference Alcock1938).

Figure 4. Successions with Manuels River Formation at localities AARN, LoL, and PoR. Key: 1) mudstone, dark grey to black; 2) interbedded dark grey to black mudstones and thin (decimetre) quartz arenites; 3) quartz arenites, to several cm-thick; 4) siltstone and silty mudstone, green grey; 5) silty mudstone and fine-grained sandstone, dark green grey; 6) phosphorite, black; 7) phosphatic nodules and clasts (top) and phosphatic (p); 8) limestone (upper), calcareous nodule (lower); 9) trilobites (upper left), echinoderm sclerites (upper right), hyoliths (lower); 10) Teichichnus (upper), calcareous (middle), neptunian dike (lower); 11) volcanic ash; 12) unconformity; 13 covered interval). Abbreviations: Ads, Avalonian depositional sequence; Bk., Brook; HB, Hanford Brook Formation; Mbr., Member; seq., sequence, (SS), Somerset Street Member.

These readily distinguishable greenish and black mudstone intervals are confused and miscorrelated in recent publications. They have been united into a ‘Forest Hills Formation’ and claimed to be conformable on the upper Lower Cambrian Hanford Brook Formation (Tanoli & Pickerill 1987; New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources 2008; Fyffe et al. Reference Fyffe, Johnson and van Staal2012; Álvaro et al. Reference Álvaro, Johnson, Barr, Jensen, Palacios, Van Rooyen and White2023; Álvaro & Mills Reference Álvaro and Mills2024, fig. 9). A reevaluation of these two units and their comparison with the SE Newfoundland succession has led to recognition of the greenish Fossil Brook as the upper member of the Chamberlain’s Brook Formation with an overlying black Manuels River Formation (Landing Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996; Figs. 1, 4, 5). The greenish Fossil Brook Member with fossiliferous limestones and overlying black Manuels River Formation occur at the southwesternmost Avalonian locality in New Brunswick at Beaver Harbour (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Johnson and Geyer2008; Fig. 2, locality BHr). However, these readily distinguished units were disregarded by Barr et al. (Reference Barr, Bartsch, Miller and White2014b; see Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b for discussion), who united every Avalonian Cambrian unit at Beaver Harbour into a Buckman (sic, read Buckman’s) Creek Formation which they assigned to their purportedly non-Avalonian and ‘Ganderian’ Little River ‘terrane.’

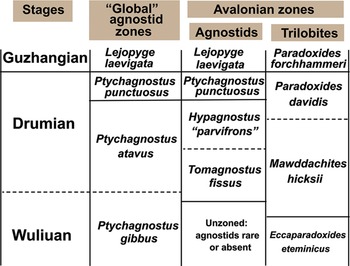

Figure 5. Middle Cambrian agnostid and trilobite biostratigraphy (upper Wuliuan–lower Guzhangian stages). See Landing et al. (Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b, fig. 12) for correlation into Avalonian North American lithostratigraphy and Avalonian depositional sequence succession.

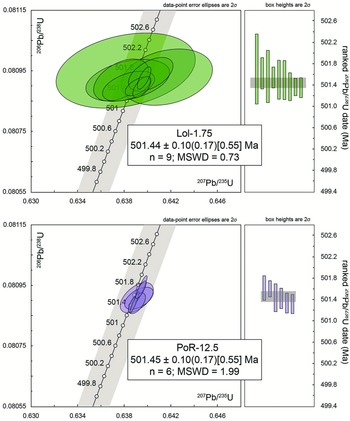

Figure 6. U-Pb concordia diagrams and ranked 206Pb/238U date plots for single zircon crystal analyses from the LoL-1.75 and PoR-12.5 volcanic ash horizon. Grey band on the concordia curve (labeled in millions of years) represents decay constant uncertainties. Grey bands on the ranked date plots indicate the standard errors of the weighted mean ages.

Our detailed field work and trilobite biostratigraphy shows a major diachronous unconformity exists with 40 m of relief between the middle Middle Cambrian ‘Forest Hills’ and upper Lower Cambrian Hanford Brook Formation (Landing & Westrop, Reference Landing and Westrop1996; Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023). This unconformity is exposed in the field area of this report northeast of Saint John and includes the unconformity on the Waites Lane Formation well to the SW at Beaver Harbour (Figs. 1, 2, locality BHr). The upper member of the Hanford Brook Formation (Long Island Member) on Long Island and at Hanford Brook is eroded away to the SE at the field localities of this study and in the Saint John and Beaver Harbour (BHr) areas (Landing & Westrop Reference Landing and Westrop1996, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998a; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b; Landing & Geyer Reference Landing and Geyer2025; Figs. 1, 3, field localities AARN, BHr, LoL, PoR).

The overlying Fossil Brook not only has trilobites identical with the uppermost Chamberlain’s Brook Formation in SE Newfoundland (e.g., Kim et al. Reference Kim, Westrop and Landing2002), but its succession of lower bedded limestone, typically thin trilobite fragment grainstones, and higher green mudstone are also lithologically identical (Landing & Westrop Reference Landing and Westrop1996, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998a, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westropb). In addition, an unconformity lies at the contact of the Fossil Brook with the overlying black mudstone across Avalonian southern New Brunswick (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b). As noted above, this black mudstone is also lithologically identical with the Manuels River Formation in its SE Newfoundland type region and in Rhode Island (Landing Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996; Landing & Westrop Reference Landing and Westrop1996; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Westrop and Landing2002; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022, Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a–c; Landing & Geyer Reference Landing and Geyer2025; Figs. 1, 2, 5) and has a dated volcanic ash horizon in New Brunswick (Figs. 5, 6).

2. d. Epeirogeny, sequence stratigraphy and hiatus at Avalonian green–black break

Terminal Ediacaran–Ordovician epeirogenic activity defined a uniform trans-Avalonian, depositional sequence architecture in Avalonian North America (including the Meguma zone), southern Britain and Belgium–northern Germany (Landing Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996; Rees et al. Reference Rees, Thomas, Hughes, Hughes and Turner2014; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022). By this synthesis, the unconformity-bounded Fossil Brook Member comprises Avalonian depositional sequence (Ads) 7 and the Manuels River Formation is Ads 8 (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Westrop and Wotte2023b) (Figs. 1, 5). This abrupt stratigraphic break is one of the most important depositional changes in Avalonia. It records a regional green–black colour change within the Middle Cambrian from oxic to strongly dysoxic/anoxic deposition that extended to the shoreline, lasted for 26 Ma into the Tremadocian, and was coeval with the onset and persistence of black mudstone deposition in Baltica (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a).

As in other marginal platform areas, the Fossil Brook Member of the Chamberlain’s Brook Formation in southern New Brunswick overlies significantly older units, where the uppermost Long Island Member (ca. 40 m) of the upper Lower Cambrian Hanford Brook Formation is absent in this report’s field area (Figs. 1, 4). In summary, the Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary interval features a major hiatus and does not record continuous deposition as claimed by Álvaro et al. (Reference Álvaro, Johnson, Barr, Jensen, Palacios, Van Rooyen and White2023; also Álvaro Reference Álvaro2021; see Landing & Westrop Reference Landing and Westrop1996; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Davidek, Westrop, Geyer and Heldmaier1998a, b, Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a; Landing & Geyer Reference Landing and Geyer2025). Lower parts of the Chamberlain’s Brook (i.e., Easter Cove and Braintree members in the Avalon Peninsula, SE Newfoundland) are absent in southern New Brunswick (Fig. 1) but are present in inner platform areas as in Cape Breton Island, SE Newfoundland, and also include the upper Purley Shale Formation in Warwickshire, England (Landing et al., Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022). Stratigraphically higher in all of these marginal and inner platform areas, the Fossil Brook Member (and an equivalent 1.5 m-thick cap of the Purley Shales) is unconformable with the overlying Manuels River Formation (i.e., Abbey Shale Formation in Warwickshire) (review in Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a).

2. e. Relative duration of Ads 7–8 green–black hiatus in Avalonia

The duration of the Ads 7–8 hiatus between dominantly oxic greenish and younger, persistent dysoxic/anoxic black mudstone deposition was likely relatively brief in SE Newfoundland where it features relatively minor erosion (ca. 2 m) of the Fossil Brook Member (Landing & Westrop Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998a, b). In addition, the unconformity in SE Newfoundland is bracketed within one trilobite zone – the lower Mawddachites hicksii Zone as defined in Avalonian North America and southern Britain and questionably into the the Ptychagnostus gibbus Zone, discussed below, as defined in Baltica (Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023; Figs. 3, 5).

The Fossil Brook Member in SE Newfoundland, as in New Brunswick, has trilobites of the Eccaparadoxides eteminicus Zone (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Westrop and Landing2002), which are succeeded by black shales generally assigned to the Mawddachites hicksii Zone (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson1962; Hildenbrand et al. Reference Hilndenbrand, Austermann, Ifrim and Bengtson2021; Unger et al. Reference Unger, Hildenbrand, Stinnesbeck and Austerman2022; Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023). However, Fletcher (Reference Fletcher2006) reported, but did not illustrate, M. hicksii at the very top of the Fossil Brook Member at St. Mary’s Bay, Newfoundland (his ‘Cape Shore Member’ in Fletcher [Reference Fletcher1972, Reference Fletcher2006] is the Fossil Brook Member, see Landing and Westrop, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998b), which suggests a brief hiatus at the Ads 7–8 unconformity (Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023; Fig. 5).

A comparable green–black, Ads 7–8 hiatus exists on another Avalonian marginal platform succession on St. David’s Peninsula, South Wales (Rees et al. Reference Rees, Thomas, Hughes, Hughes and Turner2014). Purple and grey siltstones of the upper Porth Clais Formation yield only the trilobite Ctenocephalus solvensis (Hicks Reference Hicks1875) (Rees et al. Reference Rees, Thomas, Hughes, Hughes and Turner2014, fig. 1.3). Rees et al.’s (2014, p. 13) assertion that this species is indistinguishable from Ctenocephalus matthewi (Hartt, in Dawson Reference Dawson1868) from the Fossil Brook Member (see Kim et al., Reference Kim, Westrop and Landing2002, fig. 5) is undermined by the deformed nature of sclerites of the former (e.g., Rees et al., fig. 1.5a–c). However, the two species are certainly very similar (see also Kim et al. Reference Kim, Westrop and Landing2002, p. 834), which suggests that the upper Porth Clais may lie in the E. eteminicus Zone.

This tentative correlation more tightly constrains the green–black boundary in South Wales. The Porth Clais is capped by a massive pebbly conglomerate and is likely unconformable with overlying dark grey sandstones and mudstones of the Whitesands Bay Formation with Mawddachites hicksii Zone trilobites and agnostids (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Thomas, Hughes, Hughes and Turner2014, fig. 1.3).

A similar green–black hiatus also seems to be present in Avalonian off-platform facies on St. Tudwal’s Peninsula, North Wales, where red, brown and green siltstones likely referable to Ads 7 are separated by an unconformity capped by a thin (to 4 cm), coarse-grained sandstone from overlying gray siltstones of the Nant-y-Big Formation with M. hicksii Zone trilobites (Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023). Further east, as noted above, the Avalonian inner platform in Warwickshire shows an unconformity between the greenish upper Purley Shale Formation and the dark grey Abbey Shales Formation with M. hicksii Zone trilobites (see reviews of British successions in Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023).

2. f. Relation to Drumian Stage and geochronology of Ads 7–8, green–black hiatus

The base of the ‘global’ middle Middle Cambrian Drumian Stage, defined by the lowest occurrence (LO) of the agnostid Ptychagnostus atavus (Babcock et al. Reference Babcock, Robison, Rees, Peng and Saltzman2007), is poorly resolved in Avalonia. Indeed, P. atavus is, at best, very rare in Avalonia and also has a diachronous LO either in the successive Mawddachites hicksii and Paradoxides davidis trilobite zones that bracket the North American Manuels River and Warwickshire Abbey Shale formations (Fig. 5). The lowest occurrence (unfortunately unillustrated) of P. atavus is 1.5 m above the base of the Manuels River Formation at Highland Cove, SE Newfoundland (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson1962; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a, p. 37). This means that the lowest part of the formation and the underlying Fossil Brook Member, as well as the trans-Avalonian green–black boundary would be sub-Drumian (Wuliuan Stage) (review in Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023).

A precise U-Pb zircon age of the green–black boundary and base of the Drumian Stage is not determinable based on available data from Avalonia. These horizons are certainly younger than depositional ages in SE Newfoundland on the Lower–Middle Cambrian boundary (ca. 507.67–506.34 Ma) and on an ash in the lower Braintree Member of the Chamberlain’s Brook Formation (ca. 506.25 Ma) (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a). Although numerous U-Pb zircon dates have been determined through the Avalonian Lower–lower Middle Cambrian (Fig. 1), ashes from the black mudstones of Ads 8 have not yielded datable zircons. These include multiple ashes from the Nant-y-big Formation in North Wales (Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023) and from the Manuels River Formation in SE Newfoundland (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a).

The stratigraphically episodic occurrence of datable Middle Cambrian ashes seems to reflect temporal and lateral differences in the relatively minor terminal Ediacaran–Ordovician volcanism that developed with activity along the Avalonian transform fault (Atf). The Atf generated coeval Na-alkalic tholeiitic volcanics and intrusives with an extensional signature vs a silicic to mafic calc-alkaline suite with a collisional signature along Avalonia (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022). These contrasting compositions to not reflect different terranes (i.e., ‘Ganderia’ vs Avalonia) as concluded by some reports (e.g., Barr & White Reference Barr, White, Nance and Thompson1996; Barr, White & Miller Reference Barr, White and Miller2003; Barr et al. Reference Barr, White, Davis, Mcclelland and Van Staal2014a, b; Van Rooyen et al. Reference VAN ROOYEN, BARR, WHITE and HAMILTON2019). The result of the development of two different source magma types is that datable zircons may or may not be present in successive ashes through an Avalonian depositional sequence. This artefact of magma types that changed laterally and through time makes ash sampling something of a ‘gamble.’ This ‘gamble’ is demonstrated by our failure to find datable, syndepositional zircons in the Manuels River and Nant-y-Big formations in SE Newfoundland and South Wales (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a), while an ash in the lower Manuels River in SE New Brunswick yielded readily dated zircons (this report).

3. Rte. 111 ash (new) in southern New Brunswick

Cambrian trilobite and agnostid biostratigraphy of Avalonia is hampered as B.F. Howell illustrated very few of the taxa he reported in extensive lists from SE Newfoundland and New Brunswick (Howell Reference Howell1925; Hayes & Howell Reference Hayes and Howell1937). In addition, his collections apparently did not survive a transfer from Princeton University and cannot be located for restudy (Hildenbrand et al. 2021). In the course of field work in southern New Brunswick (e.g., Landing & Westrop Reference Landing and Westrop1996, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998a, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westropb; Landing Reference Landing2004), we relocated several of Hayes & Howell’s (1937) fossiliferous Manuels River localities and put these isolated sections into a modern stratigraphic context. In addition, our newly collected material and type specimens in the Royal Ontario Museum have been described and used for a new biostratigraphic correlation (Westrop & Landing Reference Westrop and Landing2025).

A key development of this work is recognition of a thin (to 5 cm) grey bentonite in the lower Manuels River at three isolated localities along the formation’s 25 km outcrop belt northeast of Saint John (Fig. 3, localities AARP, LoL, PoR; see figure caption for details on the locations). This ash is variably located 6–12 m above the base of the Manuels River likely as a result of bedding-plane parallel shear. It is called the Rte. 111 ash (new) for its occurrence at section AARP in the Rte. 111 road cut north of the city airport (Figs. 3, 4).

3. a. Porter road (PoR)

The longest section in the Manuels River Formation in southern New Brunswick is on Porter Road (PoR), a locality earlier documented by Landing & Westrop (Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998a, p. 65, 66; precise location in Fig. 3 caption). Porter Road is not maintained and road signs term it ‘The Grand Trail’/‘Le Grand Trail.’ The PoR section, a black mudstone-dominated succession (strike 50°, dip 32°N), is exposed in a drainage ditch on the south side of the road. The base of the Manuels River is located at the lowest black mudstones above abundant fragments of green mudstone from the upper part of the type section of the Fossil Brook Member. Much of the roughly 13 m section is poorly exposed (Fig. 4) and is followed by a covered interval. Unfossiliferous black mudstone again appears at the foot of the gently sloping hill at 25.2–28.2 m. About 200 m further west is Porter’s Brook, which yielded the type specimens of a number of trilobites described by Matthew (Reference Matthew1896), including Paradoxides abenacus Matthew, although we did not find any outcrops in the stream.

Four metres of dark grey to black shale in the middle of the 28.2 m-thick succession have large, elliptical (to 50 cm wide, 10 cm thick), fossiliferous carbonate nodules. A thin bentonite (3 cm) occurs at 12.8 m and provided a precise U-Pb date (discussed below). Just below the ash, two discoidal calcareous nodules with trilobites were collected at 10.75 m and 11.0 m above the base of the section, along with three loose nodules from the same interval.

Hayes & Howell (Reference Hayes and Howell1937) named the Paradoxides abenacus Zone, without listing any taxa except for P. abenacus, for the lower part of the Porter Road section. They also assigned a higher, less diverse fauna from the P. abenacus Zone to the ‘Goniagnostus confluens shale,’ while again listing only the eponymous species. As detailed by Westrop & Landing (Reference Westrop and Landing2025, tab. 1), we recovered a well preserved, low diversity fauna with G. cf. confluens from the bedded and loose nodules and referred it to the ‘upper P. abenacus Zone.’ This fauna is dominated by endemic species of trilobites (such as P. abenacus) and agnostids. Species of the agnostids ‘Tomagnostus’ Howell and ‘Onymagnostus’ Öpik point to a number of interregional correlations (Fig. 5): with 1) the Hypagnostus parvifrons Zone in Avalonian Wales, which is referred to the Drumian Stage (e.g., Rees et al. Reference Rees, Thomas, Hughes, Hughes and Turner2014), 2) upper ‘Acidusus’ atavus Zone of Baltica and 3) likely the upper Mawddachites hicksii to lower Paradoxides davidis zones of Avalonian Newfoundland and Britain. This important new fauna provides a lower bracket on the Rte. 111 bentonite in southern New Brunswick, an upper bracket on the Avalonian green–black boundary and a correlation into the Drumian Stage.

3. b. Loch Lomond (LoL)

Hayes & Howell (Reference Hayes and Howell1937) reported a small, fossiliferous road cut opposite the narrowest part of Loch Lomond. As detailed by Westrop & Landing (Reference Westrop and Landing2025), their map location corresponds to our section LoL (Fig. 3 caption has precise location of LoL). The E–W striking, 45° south-dipping section (Fig. 4) shows the characteristic southern New Brunswick Middle Cambrian succession with green fragments of Fossil Brook Member present in the colluvium about 7 m stratigraphically below the road cut. The road cut is a short exposure of black Manuels River mudstone with a 6 cm bentonite cap in the lower part of the formation (sample LoL-1.75). After a covered interval of ca. 25 metres stratigraphically, 15 m of interbedded dark grey shale and thin quartz sandstone crop out in the forest. The shale and sandstones are represent the upper Middle–lower Upper Cambrian, MacLean Brook Group of the Avalonian coastal United States and Maritime Canada (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a; Fig. 5) and are equivalent to the Agnostus Cove Formation of Hayes & Howell (Reference Hayes and Howell1937) and Tanoli & Pickerill’s (1987) King Square Formation.

Hayes and Howell (Reference Hayes and Howell1937, p. 75) recorded their ‘Triplagnostus lomondensis shale’ fauna of their ‘Hastings Cove Formation’ from this locality. However, as discussed by Westrop & Landing (Reference Westrop and Landing2025), all aspects of the ‘Hastings Cove Formation’ are problematical. These include a type section we found to be referrable to the upper Lower Cambrian Somerset Street Member of the Hanford Brook Formation. Similarly, the unillustrated ‘Hastings Cove’ fauna (Hayes & Howell 1837, p. 89) with Paradoxides matthewi, Ptychagnostus punctuosus and Goniagnostus nathorsti does not occur at LoL.

Instead, sample LoL-0.65–0.95 has compacted internal moulds of a solenopleurid, either ‘Jincella’ acadica or a new species of ‘Jincella’ also known at Porter Road (Westrop & Landing Reference Westrop and Landing2025). In short, LoL-0.65–0.95 is correlative with the upper Paradoxides abenacus Zone at Porter Road. The location of the PoR and LoL ashes in the lower Manuels River Formation is at about the same distance above the base of the formation and indicates these are apparently exposures of the same ash horizon.

3. c. AARP section

A thin (0–5 cm) bentonite occurs in the lower Manuels River Formation in the Airport Access Road (Rte. 111) cut through the north limb of an E–W-trending anticline (see Fig. 3 caption for precise location of section AARN, Fig. 4). The exposure features an upper Lower–middle Cambrian sequence of middle Hanford Brook Formation (Somerset Street Member), with unconformably overlying Fossil Brook Member, and upper Manuels River Formation. A 5.0 cm bentonite in the uppermost Somerset Street Member is likely the same ash in the uppermost Somerset Street Member in Saint John (reported as 511 Ma by Isachsen et al. Reference Isachsen, Bowring, Landing and Samson1994; recalculated to 508 Ma by Schmitz Reference Schmitz, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012). AARN-19.15 lies 4.5–7.5 m above the covered base of the Manuels River Formation (Fig. 4) and is the type horizon and locality for the Rte. 111 ash.

Although abundant, fossil remains (trilobites, agnostids, hyoliths and echinoderm plates) are rendered unidentifiable by a pervasive cleavage at locality AARN that produced a pencil slate. A 0–5 cm bentonite (sample AARN-19.15) 4.5–7.5 m above the covered base of the Manuels River was sampled for U-Pb geochronology. This ash is almost certainly the lateral equivalent of the lower Manuels River Formation ash at the LoL and PoR sections.

4. U-Pb zircon geochronology of southern New Brunswick tuff

4. a. Analytical methods

4. a.1. Sample preparation

Abundant populations of relatively small (approximately 100–200 µm in long dimension), equant to elongate prismatic zircon crystals were separated from bulk bentonite samples with an ultrasonic clay separator (Hoke et al. Reference Hoke, Schmitz and Bowring2014), followed by conventional density and magnetic methods. The entire zircon separate was placed in a muffle furnace at 900°C for 60 hours in quartz beakers to anneal minor radiation damage. Annealing enhances cathodoluminescence (CL) emission (Nasdala et al. Reference Nasdala, Lengauer, Hanchar, Kronz, Wirth, Blanc, Kennedy and Seydoux-Guillaume2002) and prepares the crystals for subsequent chemical abrasion (Mattinson Reference Mattinson2005). Following annealing, individual grains were hand-picked and mounted, polished and imaged on a JEOL T300 scanning electron microscope outfitted with a GATAN MiniCL CL photomultiplier detector. From these compiled images, the location of spot analyses for LA-ICPMS were selected (Supp. Fig. 1).

4. a.2. LA-ICPMS analysis

LA-ICPMS analysis utilized an X-Series II quadrupole ICPMS and New Wave Research UP-213 Nd:YAG UV (213 nm) laser ablation system. In-house analytical protocols, standard materials and data reduction software were used for acquisition and calibration of U-Pb dates and a suite of high field strength elements (HFSE) and rare earth elements (REE). Zircon was ablated with a laser spot of 30 (first experiment) or 40 (second experiment) µm wide using fluence and pulse rates of ∼3 J/cm2 and 5 (first experiment) or 10 (second experiment) Hz, during a 35 second analysis (15 sec gas blank, 20 sec ablation) that excavated a pit ∼25 µm deep. Ablated material was carried by a 1.2 L/min He gas stream to the nebulizer flow of the plasma. Quadrupole dwell times were 5 ms for Si and Zr; 200 ms for 49Ti and 207Pb; 80 ms for 206Pb; 40 ms for 202Hg, 204Pb, 208Pb, 232Th and 238U and 10 ms for all other HFSE and REE; total sweep duration was 895 ms. Background count rates for each analyte were obtained prior to each spot analysis and subtracted from the raw count rate for each analyte. For concentration calculations, background-subtracted count rates for each analyte were internally normalized to 29Si and calibrated with respect to NIST SRM-610 and -612 glasses as the primary standards. Ablation pits that appear to have intersected glass or mineral inclusions were identified based on Ti and P signal excursions, and associated sweeps were generally discarded. U-Pb dates from these analyses are considered valid if the U-Pb ratios appear to have been unaffected by the inclusions. Signals at mass 204 were normally indistinguishable from zero following subtraction of mercury backgrounds measured during the gas blank (<100 cps 202Hg), and, thus, dates are reported without common Pb correction. Rare analyses that appear contaminated by common Pb were rejected.

For U-Pb and 207Pb/206Pb dates, instrumental fractionation of the background-subtracted ratios was corrected and dates were calibrated with respect to interspersed measurements of zircon standards and reference materials (Supp. Tab. 1). The primary standard Plešovice zircon (Sláma et al. Reference Sláma, Košler, Condon, Crowley, Gerdes, Hanchar, Msa, Morris, Nasdala, Norberg, Schaltegger, Schoene, Turbrett and Whitehouse2008) was used to monitor time-dependent instrumental fractionation based on two analyses for every 10 analyses of unknown zircon. A polynomial fit to the primary standard analyses versus time yields each sample-specific fractionation factor. A secondary bias correction is subsequently applied to unknowns on the basis of the residual age bias as a function of radiogenic Pb count rate in standard materials, including Seiland, Zirconia and Plesovice zircon, or similar materials of known age and variable Pb content. A polynomial fit to the secondary standard analyses with Pb count rate yields each sample-specific bias correction. Radiogenic isotope ratio and age error propagation for all analyses include uncertainty contributions from counting statistics and background subtraction. Ages are reported with and without uncertainties from the standard calibrations and are propagated into the errors on each date. These uncertainties are the local standard deviations of the polynomial fits to the interspersed primary standard measurements versus time for the time-dependent, relatively larger U/Pb fractionation factor, and the standard errors of the means of the consistently time-invariant and smaller 207Pb/206Pb fractionation factor. Method metadata and sample data are reported using the community standards of Horstwood et al. (Reference Horstwood, Košler, Gehrels, Jackson, Mclean, Paton, Pearson, Sircombe, Sylvester, Vermeesch, Bowring, Condon and Schoene2016), and additional details of methodology and reproducibility are reported in Macdonald et al. (Reference Macdonald, Schmitz, Strauss, Halverson, Gibson, Eyster, Cox, Mamrol and Crowley2018).

4. a.3. CA-IDTIMS analysis

U-Pb geochronology methods for chemical abrasion isotope dilution thermal ionization mass spectrometry (CA-IDTIMS) follow those previously published by Macdonald et al. (Reference Macdonald, Schmitz, Strauss, Halverson, Gibson, Eyster, Cox, Mamrol and Crowley2018). Zircon crystals were subjected to a modified version of the chemical abrasion method of Mattinson (Reference Mattinson2005), whereby single crystals were individually abraded in a single step with concentrated HF at 190°C for 12 hours. The remaining residual crystals were thoroughly rinsed before spiking with the ET535 or ET2535 tracer, complete dissolution at 220°C for 48 hours, followed by ion chromatographic purification of U and Pb and isotope ratio analysis by thermal ionization mass spectrometry. U-Pb dates and uncertainties for each analysis were calculated using the algorithms of Schmitz & Schoene (Reference Schmitz and Schoene2007) and the U decay constants of Jaffey et al. (Reference Jaffey, Flynn, Glendenin, Bentley and Essling1971). Some analyses exhibit amounts of common Pb significantly elevated over total procedural blank estimates of <0.5 pg, in which case the excess was assigned to initial Pb with an isotopic composition estimated from the two-stage terrestrial Pb isotope evolution model of Stacey & Kramers (Reference Stacey and Kramers1975) at the nominal sample age of 500 Ma.

Uncertainties are based upon non-systematic analytical errors, including counting statistics, instrumental fractionation, tracer subtraction and blank subtraction. These error estimates should be considered when comparing our 206Pb/238U dates with those from other laboratories that used tracer solutions calibrated against the EARTHTIME gravimetric standards. When comparing our dates with those derived from other decay schemes (e.g., 40Ar/39Ar, 187Re-187Os), the uncertainties in tracer calibration (0.03%; Condon et al. Reference Condon, Schoene, Mclean, Bowring and Parrish2015; McLean et al. Reference Mclean, Condon, Schoene and Bowring2015) and U decay constants (0.108%; Jaffey et al. Reference Jaffey, Flynn, Glendenin, Bentley and Essling1971) should be added to the internal error in quadrature. Quoted errors for calculated weighted means are thus of the form ±X(Y)[Z], where X is solely analytical uncertainty, Y is the combined analytical and tracer uncertainty, and Z is the combined analytical, tracer and 238U decay constant uncertainty.

4. b. Results

4. b.1. LoL-1.75

The heavy mineral separate for this sample comprised abundant, relatively small, but sharply facetted, equant to elongate prismatic crystals (Supplementary Fig. 1). CL imagery revealed a consistent pattern of oscillatory zonation in most crystals. A total of twelve grains were subjected to CA-IDTIMS analysis on the basis of sharply faceted morphology and CL response Supplementary Tab. 1). Three of those crystals produced older Ediacaran ages interpreted as due to crystal inheritance. Nine crystals produced concordant and equivalent isotope ratios, with a weighted mean 206Pb/238U date of 501.44 ± 0.10 (0.18) [0.57] Ma (95% confidence interval; MSWD = 0.73). Given the reproducibility of these zircon crystals of consistent internal and external morphology, this date is interpreted as closely approximating the volcanic eruption and depositional age (Fig. 5, Supplementary Tab. 2).

4. b.2. PoR-12.5

The heavy mineral separate for this sample also comprised abundant, relatively small, but sharply facetted, equant to elongate prismatic crystals (Supplementary Fig. 1). CL imagery revealed a consistent pattern of oscillatory zonation in most crystals. A total of six grains selected on the basis on CL response and geochemical similarity to the zircon from LoL-1.75 were subjected to CA-IDTIMS analysis on the basis of sharply faceted morphology and CL response (Supplementary Tab. 1). All six crystals produced concordant and equivalent isotope ratios, with a weighted mean 206Pb/238U date of 501.45 ± 0.08 (0.18) [0.57] Ma (95% confidence interval; MSWD = 1.99). Given the reproducibility of these zircon crystals of consistent internal and external morphology, this date is interpreted as closely approximating the volcanic eruption and depositional age (Fig. 5, Supplementary Tab. 3).

4. b.3. AARN-19.15

The heavy mineral separate for this sample has relatively sparse and small zircon crystals. These crystals were not considered adequate to determine a consistent and reproducible volcanic eruption and depositional age.

5. Discussion

5. a. Biostratigraphy and geochronology of Avalonian Middle Cambrian sequence stratigraphy and green–black, oxic–dysoxic transition

Because of epeirogenic activity related to the Avalonian transform fault, a continuous Lower–Middle Cambrian succession has never been documented in any Avalonian cover succession. Indeed, a particularly substantial hiatus exists in all Avalonian marginal platform successions, such as that which comprises almost all of southern New Brunswick, with exception of the tiny Cradle Brook area (Landing Reference Landing, Nance and Thompson1996; Landing, Westrop & Geyer Reference Landing, Westrop and Geyer2023; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022, Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a, b; Figs. 1, 2). Despite claims of stratigraphic continuity (Álvaro et al. Reference Álvaro, Johnson, Barr, Jensen, Palacios, Van Rooyen and White2023), a lengthy hiatus can be shown to separate the upper Lower Cambrian Somerset Street Member of the Hanford Brook Formation (Ads 4b) from the much younger Fossil Brook Member of the Chamberlain’s Brook Formation both in the Saint John and Beaver Harbour regions (Landing & Westrop Reference Landing and Westrop1996, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998a, b; Landing et al. Reference Landing, Johnson and Geyer2008). Part of this hiatus is filled in along the Long Reach area (Fig. 2), where the 40 m-thick Long Island Member (Ads 4b), which is the upper member of the Hanford Brook, has not been eroded away as a result of probable epeirogenic uplift (Landing & Westrop Reference Landing and Westrop1996, Reference Landing, Westrop, Landing and Westrop1998a).

The Somerset Street Member with ashes in its upper part (Isachsen et al. Reference Isachsen, Bowring, Landing and Samson1994; and at 9.5 m at this report’s locality AARN; Fig. 4) and the laterally equivalent volcanic edifice of the Waites Lane Formation at Beaver Harbour in southwesternmost New Brunswick (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Johnson and Geyer2008) show the characteristically increased volcanism associated with the upper part of Avalonian depositional sequences (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Keppie, Keppie, Geyer and Westrop2022). The Somerset Street ash has a late, but not latest, Early Cambrian age of 508 ± 1.0 Ma (Isachsen et al. Reference Isachsen, Bowring, Landing and Samson1994; recalculated by Schmitz Reference Schmitz, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012). Younger dates are associated with higher Avalonian depositional sequences, with the Early–Middle Cambrian boundary and Ads 4a–5 unconformity bracketed on the inner platform in Avalonian SE Newfoundland at 507.67–506.34 Ma. A slightly younger ash occurs in the lower Braintree Member (Ads 6, lower Wuliuan Stage) of the Chamberlain’s Brook Formation on the inner platform and is dated at ca. 506.25 Ma (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a).

However, the timing and rate of Avalonian epeirogenic activity and production of depositional sequences is unknown higher in the Middle Cambrian. Volcanics are unknown in Ads 7 (the Fossil Brook Member and equivalents). Lower Ads 8, the lower Manuels River Formation in Avalonian North America and lower Nant-y-big Formation in South Wales have abundant ashes, but relatively thorough sampling has not yielded an ash with anything other than detrital Ediacaran zircons (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a). However, coeval magmas produced along the Avalonian transform fault can be isotopically extensional or collisional (discussed above). This seems to be illustrated by the Rte. 111 ash, which although in the lower Manuels River Formation in southern New Brunswick, yielded datable volcanic zircons.

The almost identical ca. 501.44 and 501.45 Ma dates on the Rte. 111 ash can be cautiously used as an age for the upper Mawddachites hicksii to lower Paradoxides davidis zones as known in the middle Manuels River Formation in SE Newfoundland (Hilndenbrand et al. Reference Hilndenbrand, Austermann, Ifrim and Bengtson2021; Westrop & Landing, Reference Westrop and Landing2025). Whether or not these dates provide a rough estimate for the base of the Manuels River Formation and to the green–black boundary at the Ads 7–8 unconformity is obviously uncertain. However, if a date of somewhat older than ca. 501.45 is appropriate to the basal Manuels River Formation, it would also be appropriate to the underlying thin Fossil Brook Member (Ads 7), which shares the trilobite M. hicksii with the Manuels River Formation (discussed above).

The consequence of this series of admitted estimates suggests that a considerable hiatus (508 ±1.0 – >501.45 Ma) separates the upper Lower and middle Middle Cambrian on the Avalonian marginal platform in southern New Brunswick (Somerset Street Member, Ads 4b, and Fossil Brook Member, Ads 7). Thus, biostratigraphic information and geochronological data show that stratigraphic continuity cannot be maintained between the Hanford Brook Formation and Chamberlain’s Brook Formation (Fossil Brook Member) as claimed in some reports (e.g., Álvaro et al. Reference Álvaro, Johnson, Barr, Jensen, Palacios, Van Rooyen and White2023) as emphasized by Landing & Geyer (Reference Landing and Geyer2023). A somewhat longer hiatus exists on the Burin Peninsula where the lower Brigus Formation (St. Mary’s Member, Ads 4a) is unconformably overlain by the Fossil Brook Member (e.g., Landing et al. Reference Landing, Schmitz, Westrop and Geyer2023a, b).

5. b. Revised U-Pb zircon date on the Drumian Stage

Although precise U-Pb dates now exist for the lower and upper boundaries of the Middle Cambrian (respectively ca. 507.67–506.34 Ma and 494.5 +0.67/-0.58 Ma), few reliable dates exist through the Middle Cambrian (discussed above). The ca. 503 Ma date repeatedly assigned to the base of the middle Middle Cambrian Drumian Stage (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Finney, Gibbard and Fan2013, updated 2018; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Babcock, Ahlberg, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020) does not incorporate an earlier evaluation that little data support a 503 Ma date (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Buchwaldt and Bowring2015, p. 30). Briefly summarised (see Landing et al., Reference Landing, Geyer, Buchwaldt and Bowring2015), a number of early reports led to a focus on a 503 Ma date. Perkins & Walshe’s (1993) 502.6 ± 3.5 Ma SHRIMP 206Pb–238U and 40Ar–39Ar zircon date from the Tasmanian Mount Read Volcanics was termed ‘upper Middle Cambrian,’ but the date is a composite of a number of samples without exact biostratigraphic or geographic provenance (Jago & McNeil Reference Jago and Mcneil1997, p. 87). Perkins & Walshe (Reference Perkins and Walshe1993) also reported a mean 494.4 ± 3.5 Ma date on the Comstock Tuff above Jago et al.’s (Reference Jago, Reid, Quilty, Green and Daily1972; also Shergold Reference Shergold1995) upper Middle Cambrian Lejopyge laevigata Zone. This date is actually a reasonable bracket for the lower Upper Cambrian/Furongian (Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Cothren, Sundberg, Schmitz, Dehler, Landing, Karlstrom, Crossley and Hagadorn2025). A ca. 503 Ma date was reported on Tyndall Group and Anthony Road andesite zircon samples (Perkins & Walshe Reference Perkins and Walshe1993; 502.5 ± 3.8 Ma and 502 ± 3.5 Ma), but these lack biostratigraphic control and should simply be regarded as ‘Middle Cambrian’ (Shergold Reference Shergold1995). Yet another U–Pb SHRIMP date of 503 ± 3.8 Ma (Perkins & Walshe Reference Perkins and Walshe1993, p. 1184) comes from a debris flow with pumice clasts at the base of the Southwell Group (Jago & McNeil 1997, fig. 2), but this is a weighted mean of 21 206Pb–238U dates ranging from 519 ± 14 Ma to 483 ± 17 Ma. The debris flow overlies a middle Middle Cambrian (Drumian Stage) Ptychagnostus punctuosus Zone fauna. This 503 ± 3.8 Ma date overlaps the age of the Rte. 111 ash, although the New Brunswick upper Paradoxides abenacus Zone is most likely correlative with the older H. parvifrons Zone of Avalonia (Westrop and Landing, Reference Westrop and Landing2025). However, the Southwell Group date is simply an arithmetic mean of numerous, temporally divergent samples not appropriate to bracketing the Drumian Stage. The lower Southwell Group composite age overlaps a biostratigraphically better constrained, 207Pb–206Pb, weighted mean zircon date of 505.1 ± 1.3 Ma (ID-TIMS) from volcanic ashes that under- and overlie a fossiliferous carbonate horizon in west Antarctica (Encarnación, Rowell & Grunow Reference Encarnación, Rowell and Grunow1999). The sparse trilobites include two East Gondwanan genera that suggest a correlation with the Floran and Undillan stages of Australia and the global Drumian Stage. However, the west Antarctica age does not overlap the Rte. 111 ash date and seems too old (and likely reworked) to be Drumian.

Landing et al. (Reference Landing, Geyer, Buchwaldt and Bowring2015) also reported a ca. 503.14 Ma weighted 206PB-238U average age (ID-TIMS) on volcanic zircons from a pebbly tuff within the Treubenreuth Formation in the Tiefenbach valley within the Franconian Forest, southern Germany. The ash underlies a fossiliferous interval correlated by the trilobite genera Skrejaspis and Solenopleura into the middle Celtiberian Stage of Iberia and the Jince Formation of the Czech Republic. This genus-based correlation of the ash was interpreted to show a Drumian correlation (Landing et al. Reference Landing, Geyer, Buchwaldt and Bowring2015; Geyer Reference Geyer2019) that seems to show a significantly older age than the ca. 501.44–501.45 date on the Rte. 111 ash.

However, strata of the Triebenreuth Formation from another locality in the Franconian Forest at Wustuben include older trilobites of middle to upper Wuliuan age (Geyer et al. Reference Geyer, Landing, Höhn, Linnemann, Meier, Servais, Wotte and Herbig2019; G. Geyer, unpub. data). Quartz keratophyres associated with the Triebenreuth strata at Wustuben (dated at 536.7 ± 3.2 Ma and as Tremadocian, respectively; Höhn et al. 2017) are poorly constrained and probably not in stratigraphic succession. Thus, the Triebenreuth Formation brackets a lengthy interval, with the ca. 503.14 Ma Tiefenbach age situated within the formation.

6. Conclusions

Long-term study of the Avalonian Ediacaran–Lower Ordovician cover sequence on the Avalonian marginal platform of southern New Brunswick has included affirmation of the trans-Avalonian depositional sequence (Ads) succession with sequence boundaries recognizable between most named lithostratigraphic units. In particular, the Fossil Brook Member and Manuels River Formation (= ‘Forest Hills Formation’ [abandoned] of many reports) bracket the middle Middle Cambrian green-black boundary (i.e., oxic–dysoxic/anoxic transition) known across Avalonia. When combined with biostratigraphy, sequence stratigraphy, and other U-Pb dates from Avalonian North America and Britain, the following determinations can be made:

1) Volcanism accompanied by black mudstone deposition is recorded by the lower Manuels River Formation and equivalent units (Ads 8) in Maritime Canada, North Wales and elsewhere in Avalonia; this distinct Drumian pulse of volcanism emphasizes the Cambrian unity of east and west Avalonia which are now separated with opening of the Atlantic Ocean;

2) The accuracy of the U-Pb analyses of this report is supported by the fact that ages for two ash samples, LoL-1.75 and PoR-12.5, are identical within their uncertainties, affirming the litho- and biostratigraphic correlation of the Rte. 111 ash for at least 25 km across southern New Brunswick;

3) The ca. 501.44/501.45 Ma age is the first precise date on a biostratigraphically well-defined Drumian fauna and suggests that widely circulated dates of 503 Ma on the base of the Drumian must be reevaluated;

4) The underlying Fossil Brook Member is separated by a hiatus of relatively short duration from the Manuels River Formation, and a ca. 501.4 Ma age may also be appropriate to the Fossil Brook

5) A recalculated 508 Ma date on the underlying Somerset Street Member of the Hanford Brook Formation suggests that a ca. 7 Ma hiatus separates Lower and Middle Cambrian units on the Avalonian marginal platform in southern New Brunswick and elsewhere (i.e., Burin Peninsula, SE Newfoundland) on the Avalonian marginal platform.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756825100137

Acknowledgements

Funding for the analytical infrastructure of the Boise State Isotope Geology Laboratory was provided by NSF grants EAR-0521221 EAR1337887 and EAR-0824974 to MS. Support for Cambrian chronostratigraphy was provided by the New York State Museum and by NSF grant EAR-1954583 to M.S. Much of E.L.’s field and laboratory work was done under National Science Foundation grant support while at the New York State Museum. G.G.’s field work was supported by research grant GE 549/13-1 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; the preparation of the manuscript was made possible by research grant GE 549/22-1. Reviewers XXXXX and XXXXX are thanked for their comments.