Introduction

Over the past decade, public opposition to free trade agreements has grown in the Global North as well as in the Global South (Naoi and Urata, Reference Naoi and Urata2013; Urbatsch, Reference Urbatsch2013; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014; Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Milner and Tingley2014; Steiner, Reference Steiner2018). The case of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) is particularly interesting, with strong public resistance to the agreement especially in those countries that would have seemingly benefitted most from the agreement (e.g., the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany). This is in marked contrast to past bilateral trade agreements that mostly received only limited media coverage and were hardly contested in public. Researchers on public attitudes towards trade policy have struggled to explain this opposition relying on the so far predominant theories that assume that citizens rationally weigh the economic costs and benefits from such agreements (e.g., O’Rourke and Sinnott, Reference O’Rourke and Sinnott2001; Scheve and Slaughter, Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001; Baker, Reference Baker2003; Mayda and Rodrik, Reference Mayda and Rodrik2005; DiGiuseppe and Kleinberg, Reference DiGiuseppe and Kleinberg2019). What, then, explains individual attitudes towards trade agreements, and TTIP more specifically?

Our answer to this question rests on the assumption that the public is little informed about international politics and hence dependent on heuristics when forming attitudes towards such issues. From this perspective, citizens observe whether their trusted domestic elite is in favour of or against a trade agreement or free trade in general and then take that elite’s position as their own. There has already been some correlational and aggregate-level research on this elite-cueing mechanism for international-level attitudes (e.g., Dellmuth and Tallberg, Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2020) and for attitudes towards trade agreements (Naoi and Urata, Reference Naoi and Urata2013; Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Milner and Tingley2014). Nevertheless, research that tests the effects of this mechanism in a way that enables us to track the causal influence of elite cueing – and the conditions under which there is such an influence – on attitudes towards trade agreements is still scarce.

Building on the recent literature on international level and trade attitudes as well as elite cueing in general, we therefore derive a series of hypotheses on how elite cueing matters for individual-level attitudes towards trade agreements and test them in an experimental design. For this, we rely on a survey experiment on TTIP fielded in Germany and Spain. Doing so, we find some evidence of citizens taking the TTIP positions of political parties as cues for their own position towards the agreement, if citizens are little informed about TTIP and if they trust the parties whose positions they are confronted with. However, we only find weak source-opposing effects. Overall, our study reports some, but limited effects of elite cues when citizens are stimulated with them.

Studying the impact of elite communication on trade (agreement) attitudes is of broad relevance at a time when we see that international agreements (and international cooperation in general) have become a new battlefield on which different elites fight for public support. The growing elite contestation of trade agreements ensures that citizens have ever more elite cues available when forming their attitudes. Better understanding how and to which extent elite cueing on international matters works, hence, is of great importance for our understanding of international politics under the condition of politicization. In the conclusion, we further develop these implications of our research.

Public opinion towards trade and trade agreements

In the following, we first discuss research aiming to explain attitudes towards free trade in general and then studies that focus on attitudes towards trade agreements more specifically. In doing so, we pay particular attention to a few recent studies concentrating on the effects of elite communication.

Attempts at explaining citizens’ trade policy attitudes have mainly focused on either economic or ideational factors (Kuo and Naoi, Reference Kuo, Naoi and Martin2015). The economic (and chronologically older) line of argument states that citizens’ trade policy attitudes reflect their economic gains and losses from the international opening up of the domestic economy (O’Rourke and Sinnott, Reference O’Rourke and Sinnott2001; Scheve and Slaughter, Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001; Baker, Reference Baker2003; Mayda and Rodrik, Reference Mayda and Rodrik2005). In this view, in developed countries especially, high-skilled workers should favour trade liberalization, whereas low-skilled workers should oppose it.

The ideational line of research highlights variables, such as nationalism versus cosmopolitanism, and attitudes towards minorities and immigration as predictors for trade policy attitudes (Mansfield and Mutz, Reference Mansfield and Mutz2009; Margalit, Reference Margalit2012). Arguing from a similar direction, some studies have also focused on gender (Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Mutz and Silver2015), religiosity (Daniels and von der Ruhr, Reference Daniels and von der Ruhr2005), social trust (Spilker et al., Reference Spilker, Schaffer and Bernauer2012; Kaltenthaler and Miller, Reference Kaltenthaler and Miller2013), risk orientation (Ehrlich, and Maestas, Reference Ehrlich and Maestas2010), and dispositional sources (Johnston, Reference Johnston2013) as even more basic personal characteristics that influence the attitudes of respondents towards the opening of economic borders.

Going beyond these two lines of research, a few recent studies suggest that elite communication can also affect individual trade policy attitudes. This research builds on the assumption that few citizens have consistent and precise knowledge about international politics, let alone international trade policies. Because of this, citizens may be susceptible to the framing of the topic (Hiscox, Reference Hiscox2006; Guisinger, Reference Guisinger2017) and to elite cues.Footnote 1 Framing means that an issue is portrayed in a particular way, thus influencing people’s views of the issue (Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007). Cueing is the process in which an individual uses an information shortcut (heuristic or cue) to make a decision about, or evaluate, a subject without much in-depth knowledge (Eagly and Chaiken, Reference Eagly and Chaiken1993; for the difference between cueing and framing, see Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Hennesy, Charles and Webber2010). In many instances, the cue is an actor taking a position on a specific topic; these cues are generally referred to as source cues.

Some authors have also started to examine attitudes towards trade agreements, which may differ from attitudes towards trade more generally. A key observation of this literature is that citizens’ attitudes towards trade agreements reflect their specific contents and context factors, such as who the partner country is in the agreement (Jungherr et al., Reference Jungherr, Mader, Schoen and Wuttke2018; Steiner, Reference Steiner2018). This observation hints at a possible impact of elite communication on mass attitudes: elites highlight specific features of trade agreements to garner either support of or opposition to trade agreements. In the debate over TTIP, for example, elites opposing this agreement tried to frame it as an attack on democracy because of the provisions concerning foreign direct investments that the two parties to the negotiation wanted to include in it.

Two recent articles on free trade agreements have aimed to directly demonstrate that elite communication, including cueing, affects how respondents evaluate free trade agreements (Naoi and Urata, Reference Naoi and Urata2013; Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Milner and Tingley2014). Both argue that massive campaigning – in one case by the governing (Hicks et al.) and in another case by the main opposition party (Naoi and Urata) – led to mass approval (Hicks et al.) or refusal (Naoi and Urata) of the proposed agreement, namely the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) and the Transpacific Partnership (TPP), respectively. These two studies mainly rely on aggregate data to make their point. Turning to the individual level for the CAFTA case, Urbatsch (Reference Urbatsch2013: 210) shows that only the cueing of the anti-CAFTA party, the main opposition party, seems to have worked, as supporters of the opposition party were much more likely to be sceptical about the trade agreement.

With these few exceptions, so far the elite-campaigning argument to explain citizens’ attitudes towards trade agreements has only received limited attention. Moreover, the argument has mainly been tested using observational data, meaning that the results rely on correlations (but see Hiscox, Reference Hiscox2006 and Guisinger, Reference Guisinger2017 for experimental research on attitudes towards free trade in general). Our main innovation hence is to derive hypotheses from the rich general literature on elite cueing and to test them empirically relying on an experiment focusing on attitudes towards trade agreements that increasingly become the subject of elite contestation. This approach moves beyond correlations in establishing causality and thus promises to improve our understanding of the formation of trade (agreement) attitudes.

Elite campaigning and attitudes towards trade agreements

For citizens to have trade agreement attitudes in line with their economic interests, in most cases, they need to have a basic understanding of the economic consequences of trade policies in general. Research on public opinion, however, casts some doubt on this assumption (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992; Rankin, Reference Rankin2001; Rho and Tomz, Reference Rho and Tomz2017; but see Fordham and Kleinberg, Reference Fordham and Kleinberg2012 for a different take). Few citizens seem to have consistent and precise knowledge about international politics (Dellmuth, Reference Dellmuth2016), let alone international trade policies. This makes a direct impact of economic interests on trade agreement attitudes unlikely, and at the same time opens up the possibility of elite cueing effects. When referring to elite cueing, most authors assume domestic political parties to provide an evaluation of a policy or object (i.e. coming out in favour or in opposition to that policy or object) that citizens take as a cue to form their own opinions.

The literature on cueing in political communication research identifies two conditions that are needed to make elite or party cueing work: lack of information and trust. Starting with the lack of information condition, cue taking is likely only if the public is relatively uninformed about the topic or actor to be evaluated. Citizens that are fairly knowledgeable about a trade agreement do not need to take cues provided by political elites in the first place. Their attitude towards the agreement is likely to be fixed and they are hence unlikely to change their opinion in response to an elite cue. By contrast, citizens who have little knowledge of political life in general, and the topic of free trade agreements specifically, should be susceptible to elite cues. Several studies, focusing on a variety of different issues, have already found support for the expectation that cueing effects are smaller for more knowledgeable respondents compared to respondents with lower levels of knowledge (Kam, Reference Kam2005; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2011; Boudreau and MacKenzie, Reference Boudreau and MacKenzie2014; Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller, Hangartner and Helbling2015; Guisinger and Saunders, Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017; Pannico, Reference Pannico2017). Indeed, recent research indicates that less knowledgeable persons are still in need of simple heuristics such as elite cues even if they are provided with (hypothetical) information about the consequences of free trade for them or their country (Schaffer and Spilker, Reference Schaffer and Spilker2019).

Beside the absence of information, the second major condition of successful party cueing towards actors and policies at the international level is citizens trusting the source of the cue. That is, not all citizens will follow the cue of any domestic party. Instead, citizens should only follow the cues provided by the political party preferred by them – the ‘trusted cue-giver’ (Kertzer and Zeitzoff, Reference Kertzer and Zeitzoff2017: 544). Citizens thus should align their views with the positions taken by ‘likeable’ sources. By contrast, it makes little sense for a citizen to take a favourable stance towards a trade agreement only because they observe a political party that they do not trust adopt a position in favour of that agreement.

However, citizens might also be willing to update their attitudes based on cues from distrusted sources, but following a different logic (on the underlying concept of motivated reasoning, see Kunda, Reference Kunda1990; Taber and Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2006; Lodge and Taber, Reference Lodge and Taber2013). Concretely, they should shift their own position on the topic away from the cue, which is known as source-opposing or counter-cueing effect. That is, if an elite actor considered non-trustworthy by an individual cues a topic as positive (negative), the individual will turn to a more negative (positive) stance on the topic (Druckman, Reference Druckman2001; Aaroe, Reference Aaroe2012; see also Malhotra and Margalit, Reference Malhotra and Margalit2010; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012; Lauderdale, Reference Lauderdale2015). As put by Zaller (Reference Zaller1992: 121), ‘Perceiving the message as coming from a source with a different predisposition induces “partisan resistance”’. This discussion leads us to formulate the following three hypotheses:

H1: Little informed citizens that receive a positive (negative) cue become more favourable (more opposed) towards a trade agreement.

H2: Citizens that receive a positive (negative) cue from a trusted source become more favourable (more opposed) towards a trade agreement.

H3: Citizens that receive a positive (negative) cue from a distrusted source become more opposed (more favourable) towards a trade agreement.

Research design

To empirically analyse our expectations, we carried out a survey in Germany and Spain in June 2016 that included an experiment on TTIP. TTIP was a proposed trade agreement that aimed to liberalize trade between, and protect investments in, the EU and the United States. The negotiations for this trade agreement started in 2013 and were supposed to be concluded in late 2015. The negotiations ended without agreement with the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States, a few months after we fielded our survey. However, not only did the negotiations turn out to be more difficult than envisaged, but they also became highly politicized in some European countries (European Commission, 2015). In the face of a broad public debate, political elites, including political parties, have found it necessary to take a position on this planned agreement.

For several reasons, TTIP is an ideal case to test our hypotheses. For one, it is plausible for political parties to have adopted a position contrary to this potential agreement, whereas this is not the case for many of the trade agreements signed by the EU or the US with small trading partners that are largely uncontroversial. Moreover, contrary to most trade agreements signed by developed countries, on TTIP we find variation across respondents in terms of information about this agreement. Most trade agreements are known to only a small minority of the public, meaning that in a survey the information variable would be nearly constant.

In terms of country selection, we picked two countries where political parties play a major role in structuring public debate, which makes party cueing at least possible. This made us exclude countries such as France and Italy, where political parties are relatively weak. Selecting Germany and Spain also has the advantage that these countries differed with respect to the public salience and contestation of TTIP. While TTIP was hotly debated in German media and among politicians and citizens in Germany, its newsworthiness in Spain was more limited.

We fielded our survey to the online panels of respondi in Germany and of Netquest in Spain. The respondi panel includes some 100,000 people in Germany, whereas the Netquest panel encompasses some 120,000 people in Spain. Both panels are actively recruited, meaning that they reflect the underlying populations better than panels purely based on opt-ins. Quotas with respect to gender and age allowed us to arrive at samples that are representative on these two criteria for citizens (18 years or older and eligible to vote) in the two countries. Also with respect to education, our samples closely correspond to the adult populations in the two countries. The sample size was 2,001 respondents in Germany and 2,000 respondents in Spain.

In the survey experiment, we asked respondents about their views on TTIP. Prior to that, we introduced respondents to TTIP by asking them how informed they are about it (see below). After the experimental treatment that we outline in more detail below, we then asked respondents about their views towards this planned trade agreement. Respondents could select their answer on a 7-point scale from ‘strongly opposed’ (=1) to ‘strongly in favour’ (=7), with a ‘don’t know’ category (see the Online Appendix for the full question wording).

The experimental set-up then differentiates between a control group and eight treatment groups. The control group (N=400 in both countries) did not receive any elite cue. By contrast, the eight treatment groups (with one exception N=200 each) received either a positive or a negative cue with the source of the cue being a political party. We could only select four parties in each country, as we needed to ensure a sufficient number of respondents per experimental treatment. In Germany, the political parties that we used as cue sources were the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Greens, and the Alternative for Germany (AfD). In Spain, the respective political parties were the Popular Party (PP), the Socialist Workers Party (PSOE), United We Can (Unidos Podemos), and Citizens (Ciudadanos). At the national level, these are the parties with the greatest electoral support according to opinion polls at the time when fielding our survey.

Political parties are not the only elites that can serve as sources for cues. Citizens may also follow the cues of individual politicians, NGOs, labour unions, or churches (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991; Lupia and McCubbins, Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998; Zaller, Reference Zaller, Saris and Sniderman2004; Dür, Reference Dür2019). In the case of TTIP, especially the campaigns of civil society organizations such as Greenpeace, Campact, Attac, etc. were highly visible. We use political parties as sources for the cues because most of the recent studies that looked at elite influence on trade attitudes focused on parties.Footnote 2 This is even true for the larger literature on the impact of elites on public attitudes towards any aspect of international relations. By focusing on parties as well, we can directly respond to this literature. Moreover, political parties still strongly shape the German and Spanish political systems and tend to be the most important elites in political debates.

Respondents were told either that the party recently spoke out in favour of TTIP or that the party recently spoke out against TTIP. For example, for the CDU/CSU, the question wording for the pro cue was: ‘Currently there is a vivid political debate about this agreement. Recently, the CDU/CSU spoke out in favour of TTIP. How do you view this planned trade agreement?’ (for the full wording of the experiment, see the Online Appendix). The use of a pro and a con cue for each party was necessary to make sure that we can attribute any treatment effects to either the party or the position that we claimed the party to have adopted. In fact, we find that for the AfD even a pro-treatment has a negative effect on support for TTIP, which means that in this case the source completely dominates the content of the message. To ensure correct information for the respondents and in line with ethical standards, we debriefed participants at the end of the survey.

Of all respondents, 793 opted for the ‘don’t know’ response to this question. Since this is a significant number, we checked whether the respondents that chose this response option are different from the respondents with substantive answers. We find that prior information about TTIP, interest in politics, and gender are statistically significant predictors of a ‘don’t know’ response. The treatment itself, however, does not affect the likelihood of such a response (although the treatment itself worked, as shown below). We thus conclude that the ‘don’t know’ responses do not introduce bias in the experimental setting. The results of this analysis are available in the Online Appendix (see Table A1).

Manipulation check

We included a manipulation check after the experiment to make sure that the various treatments actually worked in the sense of changing respondents’ perceptions of the positions of political parties on TTIP. A treatment may not work because respondents simply do not read the question wording well, because the respondents discard the information contained in the treatment (for example, because they do not consider it credible) or because the information provided in the treatment already forms part of respondents’ attitudes. The last possibility is mainly relevant for the treatment groups where the treatment coincides with the positions that the political parties actually adopted with respect to TTIP. Our manipulation check is designed to capture all of these possibilities, and not only respondents’ lack of attention as is often done in similar studies. A failed manipulation check is particularly problematic if the experiment does not show an effect on the variable of interest. In that case, it is unclear whether this null effect is a result of a successful treatment not having an effect or the treatment simply not having been successful.

For this manipulation check, after the experiment we asked respondents to indicate the extent to which various actors support or oppose the planned trade agreement with the United States. The list of actors included the German/Spanish government, the European Commission, the European Parliament, and also the political parties included in the experiment. The response options ranged from strongly opposed (value of 1) to strongly in favour (value of 5), with a ‘don’t know’ option.

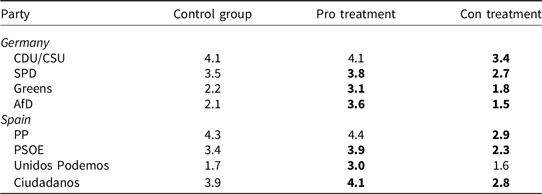

In Table 1, we present the mean values on this question for the various parties included in the experiment, separately for the control group and the respondents that received a pro or a con treatment for the respective party. A first observation is that in the control group, and hence among the respondents that did not receive the information included in the experimental treatments, the actual positioning of the parties is quite well reflected. In Germany, the CDU/CSU was in favour of TTIP, the SPD was split, and the Greens and the AfD were opposed. In Spain, both the PP and Ciudadanos were in favour, and Unidos Podemos was opposed. The PSOE was not fundamentally opposed, but asked for guarantees that the EU’s social, environmental, and labour standards would not be lowered as a result of the agreement. In line with the ‘true’ positions, the CDU/CSU and PP are perceived to be the parties most supportive of TTIP, whereas the AfD and Unidos Podemos are perceived to be the most opposed. Overall, therefore, citizens in Germany and Spain had a relatively good grasp of political parties’ positions on TTIP, either because they actually read or heard about these positions (see our discussion of pretreatment below) or because they could infer the positions from their general knowledge about politics in their country.

Table 1. Results of the manipulation check

Note: The response options ranged from 1 (strongly opposed) to 5 (strongly in favour). Bold numbers indicate values that differ in a statistically significant manner (95% level) from the control group.

Looking now at the results of the manipulation check, with only three exceptions (the CDU/CSU and PP pro treatments and the Unidos Podemos con treatment), all treatments changed respondents’ perceptions of party positions in the intended direction. In Germany, for the CDU/CSU and the SPD, especially the con treatments altered respondents’ views of these parties’ positions. This makes sense, as these treatments were more likely to contain novel information for the respondents. For the Greens and the AfD both treatments had a considerable impact. The AfD treatment is particularly strong, which suggests that the position of this party with respect to TTIP is least well known. In Spain, for all parties with the exception of PSOE, it is the surprising treatment (when our treatment differs from the actual position of the party) that mattered most for respondents’ perceptions of party positions. This is particularly strong for the PP (in the con direction) and Unidos Podemos (in the pro direction). Overall, therefore, the manipulation check confirms that our treatment was effective.

Operationalization

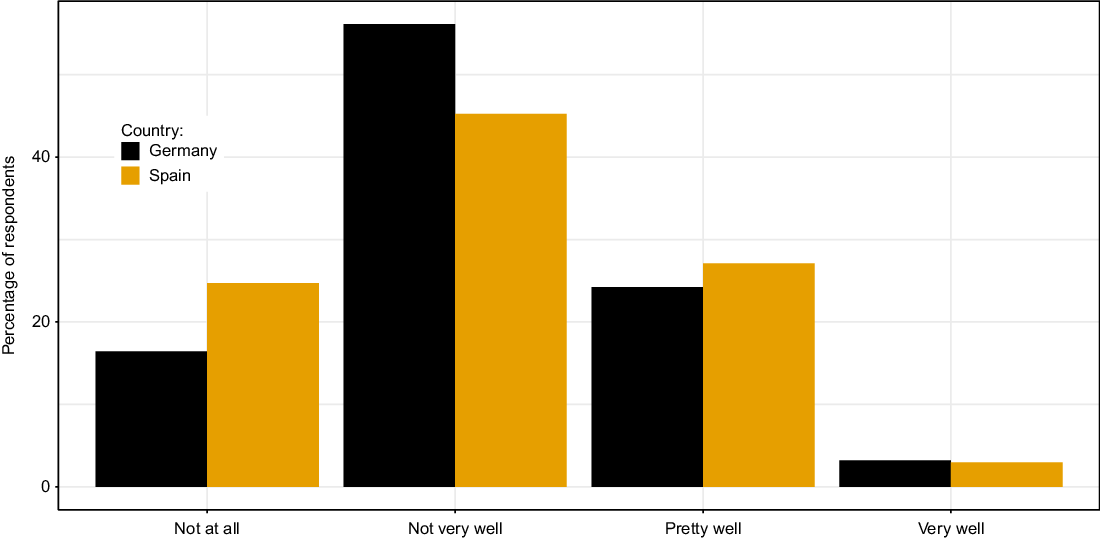

To test the hypotheses that we presented above, we need to operationalize several predictors. For one, in H1 we refer to citizens’ information about a trade agreement. Immediately before the experiment, we asked respondents: ‘The European Union and the United States of America currently negotiate a trade agreement, known as Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership or TTIP, which should facilitate trade between Europe and the USA. How well informed do you feel about this agreement?’ The response options were ‘very well’, ‘pretty well’, ‘not very well’, and ‘not at all’. Figure 1 shows the responses by country. The modal answer was ‘not very well’, with the key difference between Germany and Spain being that in the former country, fewer respondents indicated ‘not at all’ and more indicated ‘not very well’. This slightly higher level of information in Germany is in line with the greater politicization of the negotiations in that country.

Figure 1. How well informed are you about TTIP?

Our operationalization of the information variable may be criticized because it relies on a question about self-perception rather than a more direct assessment of respondents’ knowledge. To check whether our operationalization offers a valid measure of information, we used two questions that test respondents’ factual knowledge of TTIP. These questions asked respondents about their assessment of the positions of the European Commission and the European Parliament with respect to TTIP. The results of this cross check strongly support the validity of our information measure. Of those respondents that indicated that they were not at all informed about TTIP, 54% opted for the ‘don’t know’ response option in the question about the Commission and 53% in the question about the European Parliament. By contrast, the respective percentage is 8% for both the European Commission and the European Parliament among the respondents that in their self-assessment are the best informed. This indicates that respondents that consider themselves informed find it much easier to respond to a knowledge question on TTIP than respondents that consider themselves not informed. As self-reported levels of political interest generally go hand in hand with political knowledge (Delli Carpini & Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Gil de Zúñiga & Diehl, Reference Gil de Zúñiga and Diehl2019), we also checked the extent to which interest in European politics explains the TTIP information variable. Indeed, we find a positive association between the two variables (r=0.31). Overall, these checks confirm that our variable is a valid measure of TTIP information.

H2 and H3 stress the effects of trust towards political elites as being a precondition for cueing effects. We use a question on party preference that we asked before the experiment (with several other questions in between to avoid context effects) to measure this variable. Concretely, we asked: ‘Which party would you vote for if there were parliamentary elections next Sunday?’ In Germany, most respondents mentioned the CDU/CSU (20.6%), followed by the SPD (19.9%) and the AfD (16.8%). In Spain, Unidos Podemos was mentioned by 35.3% of respondents, PSOE by 19.0% and the PP by 16.9%. These values diverge from recent election results (in Spain) or other polls (in Germany), as they underestimate the vote share of the CDU/CSU and the PP. As we are interested in analysing a treatment effect rather than making inferences about the population at large, however, this should not affect the results that we report below. We assume that the party a respondent would vote for is a trusted elite, whereas all other parties are distrusted elites.

Empirical analysis

To give a first insight into the effects of our experimental treatments, Figure 2 shows the mean support for TTIP by treatment group and country.Footnote 3 What becomes immediately clear is that in general, support for TTIP is higher in Spain than in Germany, a finding that reflects the results from surveys such as the Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2014). More importantly, we can reject the null hypothesis of no effect for only a few treatments. For Germany, only the effects of the CDU con and the AfD pro treatments are statistically significant at the 95% level (when compared to the control group). Of interest, the AfD pro treatment has a negative effect on TTIP support; so the AfD coming out in favour of the agreement reduces public support for the agreement. In fact, in Germany, nearly all treatments tend to decrease support for TTIP, although only two of these effects are statistically significant. In the case of Spain, the PSOE con and Ciudadanos con effects are statistically significant at the 95% level.

Figure 2. Mean support for TTIP by treatment and country. Note: the vertical bars indicate the 90% confidence intervals.Footnote 4 The dashed lines show the upper and lower 90% confidence intervals for the control group (by country). Higher values indicate greater support for TTIP (on a scale from 1 to 7).

The fact that we find few statistically significant effects contrasts with the relatively large effects in the manipulation check that we presented above. The upshot hence is that the treatment worked in the sense of updating individuals’ views on the party positions (as shown in the manipulation check), but in most cases this is not reflected in mean support for TTIP.

These aggregate effects may hide important differences across different types of respondents, as expected in our hypotheses. Concretely, H1 predicts different effects depending on the amount of information that our respondents had about TTIP. Just looking at the direct effect of information on TTIP support (and without yet testing H1), in both countries better knowledge of TTIP is associated with more negative views of the agreement (see Table A2 in the Online Appendix). In Spain (in the control group), the mean value on TTIP support is 4.6 among those who are not informed at all and 1.6 for those who are very well informed. In Germany, the trend is similar, with the exception that those not at all informed are actually most sceptical about the agreement (mean value of 2.1). For the following analysis, we recoded this variable to take on only two values: not or not well informed and pretty well or very well informed. We do so because otherwise for some groups we have few observations.

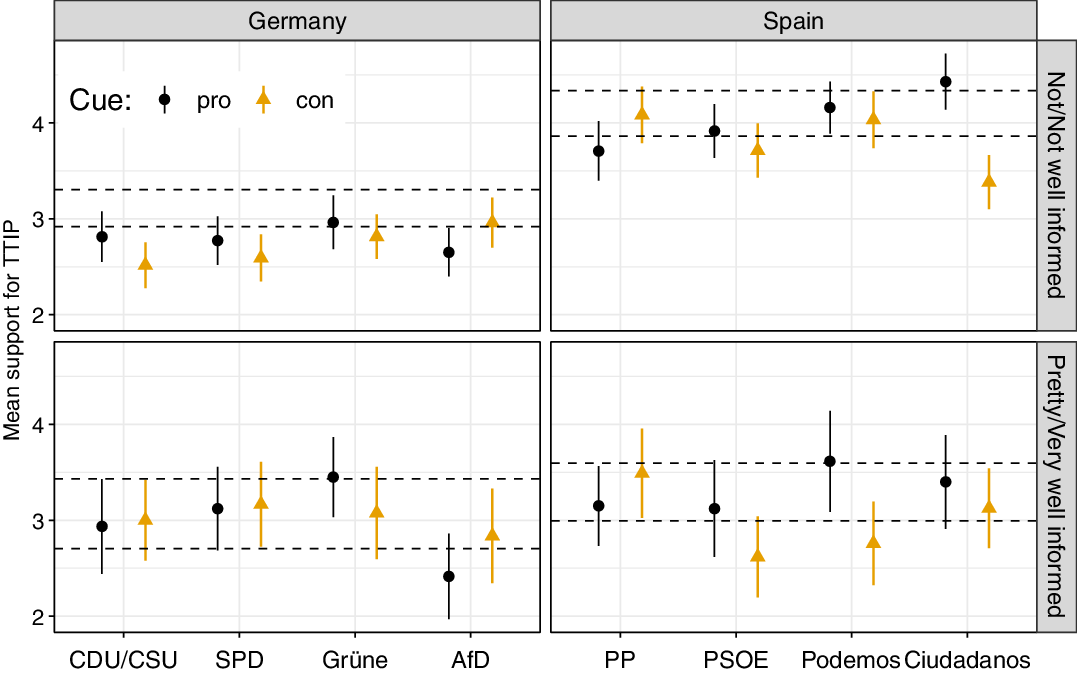

Figure 3 confirms the finding from Figure 2 that the treatments only rarely had an effect. When they did have an effect, however, this is only present for the group of not or not well informed respondents. In Germany, the CDU/CSU con, the SPD con, and the AfD pro treatments made little informed respondents more sceptical of TTIP than the control group (p < 0.05). Among the well informed, we find no statistically significant effects. In Spain, the only statistically significant effect is for little informed respondents that received the Ciudadanos con treatment. For the well-informed, again, the treatments did not matter. To the extent that they had any effect at all, therefore, the party cues mattered more for respondents with little information about TTIP. Nevertheless, overall this evidence only provides limited support for H1.

Figure 3. Information and TTIP support by treatment group. Note: the vertical bars indicate the 90% confidence intervals. The dashed horizontal lines show the upper and lower 90% confidence intervals for the control group (by country and information level). Higher values indicate greater support for TTIP (on a scale from 1 to 7).

These results with respect to information raise the question whether the treatment simply did not work for the better informed. Possibly, these respondents had a clear idea of party positions on TTIP and thus either received information they already knew (in the treatments that confronted respondents with the actual positions of the parties) or that they immediately discarded as wrong (in the treatments that confronted respondents with fictitious positions). However, the data from our manipulation check (see the above discussion) do not support this interpretation. In fact, the manipulation check indicates that the treatment worked equally well for the better and for the worse informed, largely independent of country and political party (see Table A3 in the Online Appendix). The interpretation that fits the evidence best, hence, is that the better informed had a clear-cut attitude with respect to TTIP, which they were less willing to change because of a party cue than the less informed.

In H2, we expected that the cueing effect – in the direction advocated by the parties – should only be observable for respondents trusting the respective party. In other words, this hypothesis envisages that only supporters of the CDU/CSU react to a pro statement attributed to those parties with higher support for TTIP. By contrast, for people not close to the CDU/CSU, the effect might be non-existent or even the opposite. The lack of effects found in Figure 2 then would be the result of mixing up respondents trusting and distrusting the respective party.

Given that for each treatment and country, we have at most 200 respondents, but several parties that respondents could feel close to, some cell sizes in the following analysis are small (see Table A4 in the Online Appendix). Some comparisons, therefore, come with considerable uncertainty. Before discussing the results of the experiment, it is interesting to check for differences in TTIP attitudes across people with different party preferences in the control group (see Table A5 in the Online Appendix). These differences are large: in Germany, support is highest among CDU/CSU supporters (mean of 4.0) and lowest among supporters of the Green party (mean of 2.6). In Spain, the differences are even more pronounced, with the means ranging from 5.4 for the PP to 2.5 for Unidos Podemos. Citizens thus took a position on TTIP that was relatively close to the position their preferred parties adopted on that agreement.

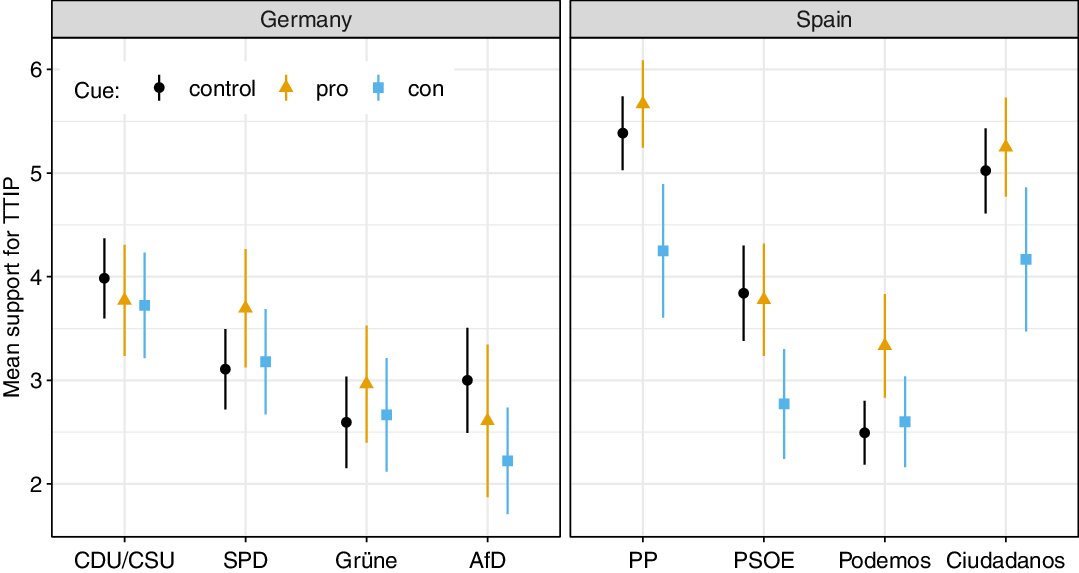

Figure 4 shows the results of the experiment. If there were cueing effects, respondents that prefer a party (e.g. the CDU/CSU) should become more supportive of TTIP when they get a positive cue from that party and less supportive of TTIP when they get a negative cue. In Germany, we find no statistically significant effect in that direction for any of the parties. Nevertheless, we see that respondents exposed to the con treatments indicated consistently lower support for TTIP than respondents exposed to the pro treatments. In Spain, we find considerable cueing effects for several parties. The PP con, the PSOE con, and the Podemos pro treatments all have a statistically significant impact on the TTIP attitudes of respondents that trust the respective party.

Figure 4. Mean support for TTIP by treatment (party supporters only). Note: the vertical bars indicate the 90% confidence intervals. Higher values indicate greater support for TTIP (on a scale from 1 to 7).

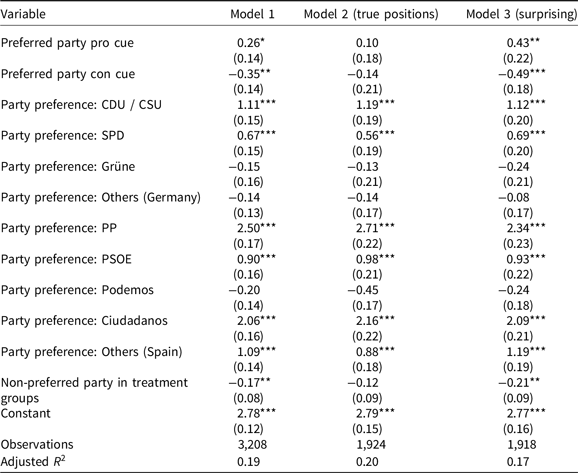

As the cell sizes in the previous analysis are small, and the results hence come with high uncertainty, we implemented a further test of this hypothesis. For this test, we created a dummy variable that is coded 1 for all respondents exposed to a pro treatment by their preferred party (Preferred party pro cue). A further dummy variable captures all respondents who received a con treatment from their preferred party (Preferred party con cue). We then ran a linear regression model with TTIP support as dependent variable, and these two dummies, a categorical variable capturing respondents’ preferred parties, and a further dummy controlling for all other respondents not in the control group (Non-preferred party in treatment groups) as predictors. We need to control for respondents’ preferred party as the control group contains voters of parties not included in the treatments (and respondents who did not answer the preferred party question), but Preferred party pro cue and Preferred party con cue do not. Doing so also controls for variation across countries, as the parties are perfectly nested in countries. In this set-up, the coefficients for Preferred party pro cue and Preferred party con cue can be interpreted as the average effects of the four pro (con) treatments relative to the control group.

The results of this model are shown in Table 2 (see Model 1). As expected in H2, the coefficient for Preferred party con cue is negative and statistically significant. This means that on average, a con treatment moved respondents that prefer the party that is the source of the cue towards less TTIP support (relative to respondents in the control group). Also in line with H2, the coefficient for Preferred party pro cue is positive – however, this coefficient is only statistically significant at the 0.1 level (the p-value is 0.07). Neither of the two coefficients is particularly large (−0.35 and 0.26, respectively), but together they indicate that whether a respondents’ preferred party comes out in favour of, or in opposition to, TTIP has a considerable impact on respondents’ position towards TTIP (a move of 0.61 on a 7-point scale). This evidence thus offers support for H2.

Table 2. Cueing, party preference, and TTIP support

Note: the table reports the coefficients from a linear regression model with TTIP support as dependent variable (with standard errors in parentheses). *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01.

The fact that the coefficients for Preferred party pro cue and Preferred party con cue are relatively small in Model 1 might be the result of pretreatment effects, namely that respondents were already aware of the stance of their preferred parties towards TTIP. If so, we should find no or only small effects especially for those respondents who received the ‘true’ TTIP positions of their preferred parties as cues, while we should observe more substantive effects for those respondents receiving ‘false’ or what we call surprising TTIP positions of parties. Testing this expectation in two separate models (see Models 2 and 3 in Table 2), we find this to be the case. For respondents receiving the true or non-surprising TTIP positions, the coefficients are 0.10 for the pro and −0.14 for the con cue, both non-significant. In contrast, for respondents receiving the surprising positions, the coefficients are 0.43 for the pro cue and −0.49 for the con cue, both of them statistically significant.

In H3, we expect that cues from non-trusted elites can have the exact opposite effect than cues from trusted elites. The expectation thus is that respondents distrusting a specific party would move their position more strongly away from the (communicated) position of that distrusted party. In Figure 5, however, we only find significant source-opposing effects for two parties, the German AfD and the Spanish PP. When told that these parties are in favour of TTIP, respondents not likely to vote for them moved their TTIP position towards more negative values. What we also see is that in most treatment groups (whether pro or con), there is slightly lower TTIP support among party non-supporters than in the control group.

Figure 5. Mean support for TTIP by treatment (party non-supporters only).

Although in this case the analysis does not suffer from the small-N problem that we confronted in our test of H2, we still also implemented a test in line with the one shown in Table 2. In this case, we ran the model with dummies for the cues from non-preferred parties and a dummy for the respondents who received a cue from their preferred parties. Here we do not need to control for party preference, as both the control group and the non-preferred parties dummies contain respondents independent of their party preference. In line with Figure 5, we find that both a pro cue and a con cue from a non-preferred party reduce TTIP support relative to the control group (see Table A6 in the Online Appendix for the full results). This backs the part of H3 that deals with pro cues, but not the part that deals with con cues.

Overall, therefore, the results offer some support for the existence of cueing effects that are conditional on information and trust. There is also some evidence for source-opposing effects. Nevertheless, most of the effects that we showed are not particularly large. As already indicated above, one explanation for these rather small cueing effects is that pretreatment affects our results (Slothuus, Reference Slothuus2016). This could explain the high correlation between our respondents’ position towards TTIP (in the control group, and hence unaffected by our experimental cues) and their preferred political parties’ positions towards that agreement (see Table A5 in the Online Appendix). It would also account for the difference in the results reported in models 2 and 3 in Table 2.

Differences in our findings between Germany and Spain offer further support for the pretreatment explanation. TTIP was more salient in the former than in the latter country. Indeed, the results of a LexisNexis research indicate that the amount of media coverage on TTIP was significantly greater in Germany than it was in Spain. Moreover, on a per-capita basis, there were many more German submissions to the EU’s public consultation on investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), one of the most contested topics in the TTIP negotiations (European Commission, 2015). The greater salience of TTIP in German public discourse implies that pretreatment effects should be more pronounced in Germany, making it more difficult to change attitudes in an experiment there.

In fact, we received more ‘don’t know’ responses to the TTIP question in Spain than in Germany. Moreover, when running the model reported in Table 2 with interaction terms for Preferred party pro cue times Spain and Preferred party con cue times Spain, we see that the pro cue effect is mainly driven by Spanish respondents (see Table A7 in the Appendix). In the absence of pretreatment, therefore, we should expect to find larger cueing effects than those reported in this paper.

Conclusion

Recent research has shifted attention to citizens’ use of heuristics in forming their attitudes on trade agreements and international cooperation more generally. In this paper, we have examined the effects of such a heuristic, namely the positions of trusted elites, for the case of TTIP. We have found some support for the expectation that citizens use source cues to form their attitude on trade agreements if they have little information about the topic and if they trust the sources of the cues. Moreover, we found partial evidence of a source-opposing effect, indicating that citizens do not just passively accept any cue they are provided with.

Cueing, of course, is not the only means that political elites have to influence citizens’ attitudes towards trade and trade agreements. Elite communication and the campaigning around trade agreements consist in more than the straightforward mechanism of party cueing that we tested in this paper. For one, by focusing on political parties, we might have overseen the effect of other political elites, such as non-governmental organizations. Moreover, and maybe more importantly, there is an alternative way of steering citizens’ thinking about trade agreements and free trade more generally, namely via framing (see also Dür, Reference Dür2019). By linking a trade agreement to specific points of reference, such as citizens’ worldviews or labels such as autonomy or sovereignty, elites might be able to make citizens think about the agreement in a specific way. In turn, this might affect whether citizens support or oppose the trade agreement. Future research on attitudes towards trade agreements, and free trade more generally, should hence explore in more detail how parties and other elites use frames to steer public opinion. Anecdotal evidence suggests that framing TTIP as a danger for a country’s sovereignty was a highly effective strategy. This would also explain why we find that the best informed respondents in our sample were those most opposed to TTIP: it is the well-informed that most likely had been recipients of elite frames prior to our experiment (with negative frames dominating the public debate).

Connecting these findings to the wider literature on public opinion towards international level policies and actors in times of constant contestation, our results suggest that there is an effect of elite cueing, but that pretreatment of citizens through framing or cueing is a relevant issue that needs to be taken into account in future research. Once citizens have formed an opinion towards an international-level actor or policy – even as complex as a trade agreement – they cannot be easily shifted away from that opinion just by their favourite party cueing them again in a different direction.Footnote 5 The resulting expectation – to be tested in future work – hence is that those who sets credible frames and cues first, win public opinion.

Future research should thus expand our study in several ways, including frames in addition to cues in the experimental treatments, analysing a greater range of countries and actors providing different forms of heuristics, and studying differences across trade agreements. Explaining what makes citizens think about trade agreements and trade policy as they do seems to be worth the effort in face of the globalization backlash that we currently experience. With international cooperation having become a battleground for different elites, some of them taking a cosmopolitan and some a nationalist position, elite communication on international matters has become omnipresent. How elite communication, comprising cues and frames, affects citizen attitudes then has relevance beyond the question of trade agreement attitudes tackled here.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577392000034X

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge comments on an earlier version of this paper from Lukas Linsi, Oliver Westerwinter, James Wilhelm and audiences at the annual convention of the International Studies Association (2017), the annual conference of the European Political Science Association (2017), and the Dreiländertagung (2019).

Funding

Austrian Science Foundation (FWF), Grant number I 576-G16.