To put it plainly and broadly, the question is, whose property is the underground coal?

———Asutosh Mukherjee, Bengal High Court, 1912Footnote 1INTRODUCTION

In February 1972 in the Bokaro collieries of the National Coal Development Corporation of India, fire ripped through the opencast Kargali seam, lighting up nearby scrub brush and grasses in flames visible from miles away. The fire had been known for at least four years, smoldering beneath the abandoned workings of the quarry's surface, but its arrival into daylight coincided with the first phase of the Government of India's nationalization of the country's coal mines.Footnote 2 India's program of coal nationalization, led by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, was spurred by different interests within the fractured coalitional politics of Gandhi's government. It was legitimated, however, as a final repudiation of the contentious property claims and destructive working methods that had characterized the domination of India's coal resources by European capital since the late nineteenth century.Footnote 3 But despite appeals to a new age of Indian energy production unencumbered by the colonial past, many of the mining complexes the state inherited were to be much like Kargali—landscapes of fire and rubble.

Coal fires, underground flooding, and land subsidence were a persistent problem across the coal region of eastern India's upper Damodar river valley and the Chotanagpur plateau for nearly all of the twentieth century. Many of these ecological crises originated in the 1890s, when the coal resources of this region were incorporated into an expanding world market for fossil fuels. Between 1894 and 1908, a commercial boom in coal production transformed the upland plateau from a remote agrarian frontier on the edge of British imperial power in South Asia into a nodal site of an emergent global energy economy.Footnote 4 In this brief period, coal extraction displaced agricultural land and deciduous forests, clearing settlements of adivasi (Indigenous) and lower-caste cultivating groups in a wake of railway lines, company towns, and coal pits. This transformation brought with it new struggles over land that pitted mining companies against these cultivating communities and established the lineaments of legal conflicts over property rights that followed every further advance of the mining frontier in the twentieth century.Footnote 5

The pace of expanded investments in coal land after 1894 combined conflicts over land with ecological ruin. Frenzied speculation on the region's subterranean resources created a structure of mining production predicated on quick profits, land hoarding, and the over-accumulation of coal stocks, resulting in the collapse of coal prices after 1908.Footnote 6 The rising value of Indian coal during the boom inscribed itself onto the landscape by generating a recurring and cumulative logic of disaster, what the early twentieth-century Bengali author Sarayubala Sen described as patala bhoomi, a hell on earth.Footnote 7 Companies dug haphazard vertical shafts and shallow pits into the earth, oxidizing and then igniting underground coal seams that broke cracks into the surface and sent reams of smoke into the air. Underground support pillars and dividing walls were robbed of every available inch of coal. During the monsoon, rain flowed into open mining shafts, which often put out the fires but also inundated the underground caverns, which companies subsequently abandoned. In Jharia, the main anthracite coalfield in India, damage from fires and subsidence was particularly spectacular and in 1931 led to a temporary evacuation of the entire town that had grown up around the coalfield.Footnote 8 A World Bank Report from 1998 described Jharia's continuing fires as of an “unprecedented, world-wide” scale and warned that they, along with noxious gases and subsiding land, threatened to displace over a million people.Footnote 9

This article explores the origins of these social and ecological displacements through the formation of the colonial property regime governing land acquisitions for coal. Drawing from what the political ecologist Michael Watts, describing contemporary sites of oil production, called “frontiers of accumulation and dispossession,” I will show how capital investment transformed the agrarian environment of India's coal region under the contractual assemblage of the subterranean property claim.Footnote 10 Property is a central analytic for the study of global mining environments since it represents the contingent legal basis by which extractive enterprises seek to secure their claims on subsoil resources. In historical accounts of fossil fuel economies, property claims have been framed in relation to the political economic category of ground rent, which is the monetary value landowners and states charge firms to access coal or petroleum reserves.Footnote 11 Ground rent is a curious political economic category, not only because it has functioned as a determining aspect of asset pricing for fossil fuel commodities, but, more fundamentally, because it represents the sedimentation of historical struggles over who is permitted to monopolize finite reserves of land and nature.Footnote 12 In the context of resource frontiers where mining activity had previously not been part of land use regimes, the arrival of capitalist firms claiming to own subterranean property rights therefore presents an important question for historical interpretation: how do preexisting forms of landed property and ground rent come to interact with new social and ecological pressures generated by the land-intensive logic of extractive industries?

Extractive firms do not enter resource frontiers of their own making, but necessarily rely on the heterogenous conditions of land ownership, regional ecologies, and norms of contract-making that precede their arrival.Footnote 13 In the area that would become colonial and postcolonial India's most important site of energy extraction, mining firms in the nineteenth century encountered an agrarian property regime centered on the rule of a large landowning class known as zamindars, literally owners/holders (dārs) of the soil/land (zamīn). Zamindari control over the land stemmed from the colonial property system created by the East India Company in the eighteenth century, in which the Company delegated the rights of land revenue collection to regional elites under a legal framework intended to recognize preexisting hierarchies of agrarian custom.Footnote 14 During the mining boom of the 1890s, the rush of subterranean property claims undercut the apparent juridical stability of these customary norms, as contradictory legal claims over the land revealed that the zamindari settlement lacked any recognition of coal as a formal property right. In reassembling the hitherto neglected archives of colonial mining firms and civil court judgements from before and after the boom, I document how this absence of legal certainty nevertheless allowed for the commodification of the geological wealth of the mining region. This process, as subsequently recognized by the civil courts, proceeded through the trading of agrarian land deeds as if they implied rights to subterranean property. The primary contractual forms governing these agrarian titles used a capacious definition of “land” that had been formerly understood to denote agricultural property, and which lacked any statutory referent to three-dimensional claims over mineral resources.Footnote 15

Landed property remains an intractable site of debate in the colonial history of South Asia. Because land represented the primary store of social wealth in the colonial economy, the significance of legal codes governing access to it, as well as proprietary rights to sell, mortgage, or borrow against its value, cannot be overstated. The nineteenth-century colonial state was deeply concerned with the enumeration of property as the basis for expanding state revenues and encouraging capital investment in agriculture. But, as scholars of agrarian South Asia have long observed, colonial property systems also adhered to a countervailing logic of paternalistic governance, characterized by policies intended to preserve what colonial officials believed were customary landed entitlements from the dispossessive effects of increased marketization.Footnote 16 With few exceptions, existing scholarship has viewed customary landed property, such as the zamindari settlement, as a static or residual category of landownership representing a barrier to the deepening of capitalist social relations in the countryside.Footnote 17 This perspective, which tends to follow nineteenth-century agrarian critiques of zamindars as feudal remnants, overlooks the jurisprudential mutations of custom in the context of capital investment in land. It relies instead on an idealized conception of the legal-institutional environments of modern markets, and thereby neglects the historical repurposing of nominally “pre-capitalist” social forms and status-based entitlements within the uneven geographies of global capital.Footnote 18

In what follows, I present an alternative account of law and capital in India's coal region. I argue that the expansion of the mining economy during the coal boom depended on maintaining the ambiguities of zamindari custom, a process that deepened inequalities of landholding and shaped agrarian dispossession into the twentieth century. My focus on the legal ambiguity of custom reveals how capital, not merely the legal institutions of states, produces property regimes.Footnote 19 In the resource frontier of the coal region, the legal codification of coal as property did not precede the expansion of mining capital, but was, rather, recursively assembled within Indian civil courts during and after the commodity boom. Mining firms, landowners, company lawyers, and Indian jurists pushed at the limits of customary jurisprudence in order to legitimate new financial and extractive claims. Although the courts acknowledged the difficulty of identifying precedents for coal property, their legal method insisted on an expansion of zamindari custom as a way of accommodating the rights of mining capital within the existing jurisprudence of agrarian land. This recursive conception of law embedded histories of dispossession and illegitimate acquisition within the discursive sanctity of what would only later come to be understood as the zamindari right to subterranean property.

The argument is carried forward in three sections. The first section reconstructs the history of zamindari custom in the context of the formation of the mining region as a political frontier within colonial South Asia. The second section shifts from this account of agrarian law to the land acquisition strategies pursued by the mining region's largest coal firm, the Bengal Coal Company. Using records from the company's Zamindari Department, I track how colonial mining firms used the contested proprietary status of coal to claim entitlements over agrarian land, as well as the labor of adivasi and lower-caste cultivating communities. The third section retreats into the civil courts and colonial legislative bodies that deliberated on the possible definitions of coal property during the mining boom. The reframing of the statutory meaning of “land” as a three-dimensional object juridically split the mining landscape into topsoil and subsoil rights. This new spatial form of property, I show, proved incapable of maintaining the alleged equality between cultivation and mining rights. I conclude by briefly considering how the history of law-making outlined here suggests a method of rethinking the study of extractive economies in South Asia more broadly.

FRONTIERS OF LAW AND CAPITAL IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

To the hagiographers of business enterprise in South Asia, the expansion of coal mining into the Bengal uplands and the Chotoanagpur plateau during the nineteenth century evoked the image of a frontier space comprised of forests, uncultivated wastelands, and uncivilized lower-caste and adivasi communities coming within the embrace of modern commerce, law, and infrastructure. The subtle transformation of the region by coal mining could hardly be remarked upon at mid-century. Then, by the 1860s, official reports and geological surveyors began noting with greater frequency the growth of collieries and coal wharves, abandoned mine shafts and quarries, and coal barges and coal-laden bullock carts throughout the valleys of the upper Damodar and the Barakar rivers.Footnote 20 Traveling to the region in 1868, the merchant Bholanauth Chunder remarked in amazement at his arrival in Raniganj, the company town controlled by the Bengal Coal Company, describing how “as one stands with his head projected out of the train, the infant town bursts on the sight from out an open and extensive plain, with its white sheening edifices, the towering chimneys of its collieries, and the clustering huts of its bazaar—looking like a garden in a wilderness, and throwing a luster over the lonely valley of the Damooder [sic].”Footnote 21 By the 1890s, these Faustian outposts of progress extended westward in a long arc from the Raniganj coalfields, the terminus of the original 1853 East India Railway line, to the coal seams of Manbhum and Hazaribagh, the valleys and lower escarpments of the Chotanagpur plateau.

The “transformation of [this] rural area into an industrial area,”Footnote 22 in the words of one colonial official, was produced through the westward shift of the mining frontier from the “old’ collieries of the lower Raniganj coalfield to the “new” coalfields of upper Raniganj, Barakar, and Jharia with the connection of a new railway line in 1894.Footnote 23 Coal production soared thereafter, witnessing sustained growth until 1908, when overproduction and a subsequent devaluation of coal stocks temporarily slowed the rate of new investment.Footnote 24 Indian railway consumption and new export markets for Indian coal drove the boom, sending eastern Indian coal westward across the subcontinent and out into steamships and coaling depots in the Straits Settlement, Dutch Batavia, Malaya, Borneo, British Burma, Galle, and Aden.Footnote 25 During the coal boom, the small market town of Dhanbad and the nearby collieries of the Jharia coalfield rapidly emerged as the central core of India's new energy economy. The East India Railway Company's early monopoly in the Jharia coalfields created a network of branch and feeder lines connecting private coal properties with one of British India's largest railway networks, described by one public works adviser as “lines radiating in all directions from a common center, like the tentacles of an octopus.”Footnote 26 By the time that Indian coal prices collapsed in 1907–1908, this extractive infrastructure had made India into one of Asia's leading suppliers of export coals and the largest colonized producer of coal within the British Empire.Footnote 27

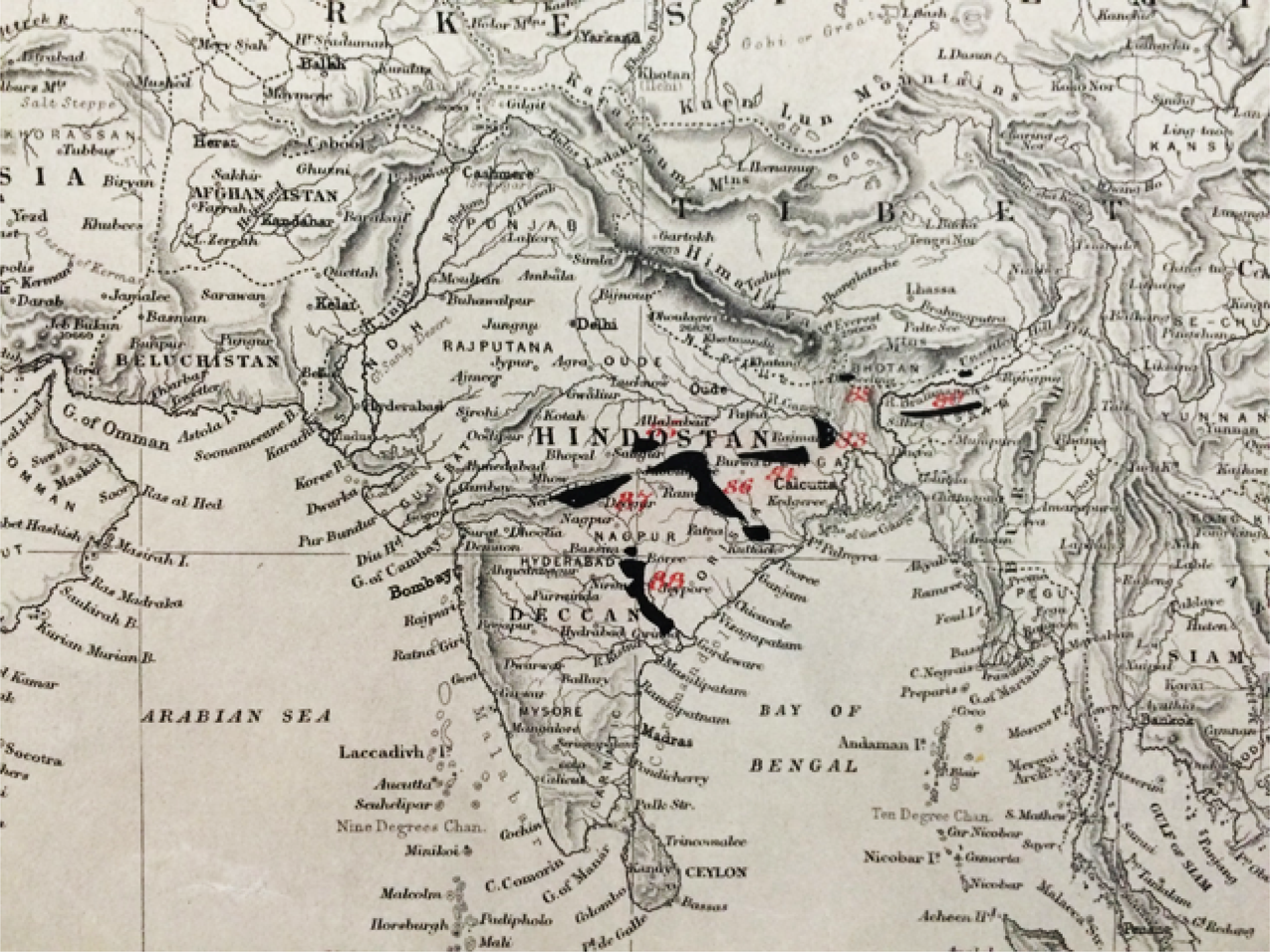

Image 1. “Track Chart of the World, Shewing Coalfields,” Admiralty Chart, R. C. Carrington, Hydrographic Office. 1874–1883. National Archives of the United Kingdom (NA), WO 78/2375. The region discussed here is the shaded area nearly parallel with “Calcutta.”

The entirety of this emergent global trade in Indian energy commodities depended on a complex juridical architecture of agrarian property rights. In contrast to the Indian railway companies, which acquired land under the legal mandate of eminent domain, mining firms operated in the agrarian land market by seeking to capture land titles, revenue collecting rights, and legal writs and appurtenances over coal-bearing properties.Footnote 28 The overarching legal system governing the capitalization and exchange of such deeds was the Permanent Settlement of Bengal of 1793, the founding document of colonial land policy in eastern India. The Permanent Settlement established a system of landholding centered on a class of large landowners known as zamindars who were responsible for discharging fixed revenues to the colonial state. Drawn from the administrative hierarchy of the Mughal Empire, zamindari had previously represented an administrative category of revenue office holding, not a permanent owner of agrarian property.Footnote 29 The colonial theory of zamindari, however, converted this office into a type of feudal estate-holding, concentrating agrarian property and the collection of ground rent from subordinate tenants under the zamindars. In reality, the areas that became zamindari estates contained a multitude of preexisting landowning and rent-receiving relationships that superseded claims by zamindars to control the agricultural surplus. But the Permanent Settlement did not address these distinctions and instead insisted that an evolving common law framework would adjudicate relations between zamindars and their tenants according to local customs.Footnote 30

The legal theory of the Permanent Settlement was shaped, fundamentally, by the contingencies of colonial state-formation. The law's recognition of a large landowning class reflected the early colonial state's limited administrative power and the necessity of delegating the responsibility of revenue collection to regional elites. Unlike in settler colonial states where rights to private property were constructed against the alleged absence of the property frameworks of the colonized, colonial Indian officials based their own claims to sovereign legitimacy on the alleged preservation of the “residual sovereignty” and customary legal orders of the agrarian property systems preceding European conquest.Footnote 31 The imagined coherence of colonial law-making, however, ultimately required a translation of these customary categories of proprietorship into generalizable principles that could be enforceable under uniform procedures of law.Footnote 32 In the territories of Bengal and Bihar, the resulting mode of agrarian governance was a kind of universalization of the zamindari system across heterogeneous agrarian contexts, which subsumed diverse agroecologies and histories of land use under the normative “property principle” of the Permanent Settlement.Footnote 33

The tensions inherent in the application of zamindari property were especially apparent in the frontier areas of the upland plateau, which gradually became incorporated into the jurisdiction of the colonial state after 1760. These territories had never served as a significant source of agricultural revenue under the Mughals or their successor states, and were settled primarily by adivasi communities of Bhumij, Kols, Kurmis, Mundas, and Santals, as well as the bonded laboring caste of Bauris.Footnote 34 The agrarian system in the plateau was characterized by what the adivasi community of Santals called chitra phutau, the breaking up and clearing of forests for small-scale farming. The plateau districts that would become the fulcrum of the colonial coal economy, Manbhum and Hazaribagh, lay at the border between the upland forests and the agrarian settlements of the plains. The familial clans whom the colonial state identified as revenue-paying zamindars in these districts were largely military chiefs claiming warrior-caste (Rajput) lineages. Most of these families lacked strong claims to agrarian territory or any preexisting authority to extract revenues from subordinate landowners. Their authority derived in large measure from their role in commanding the military service-tenures (ghatwals, digwars) that guarded the mountain passes of their border territories. In the late eighteenth century these mountain passes connected the forest economy to lowland markets through the circulation of timber, tussar silk, lac resin, and iron, among other types of forest produce. These goods moved through the edges of Manbhum and Hazaribagh on routes following Jain and Vaishnava pilgrims, field laborers, hunters, and chuars (thieves), the pejorative name applied to adivasi groups used by jungle chieftains to forcibly recruit laboring castes to work land in the forest.Footnote 35

The Permanent Settlement attempted to reorder these networks of mobility by tying local political power to the collection of agricultural revenue. In Manbhum and Hazaribagh, prominent households identified as zamindars styled themselves as rajas, or kings, referencing mytho-genealogies of a ritual authority that connected their lineages to other Rajput-claiming families across the central plateau.Footnote 36 At the time of the settlement, these zamindars presided over loosely-identifiable agrarian estates without systematic revenue-extracting institutions or written records of land rights. The goal of settlement officers was to convert the array of adivasi villages, service and military tenures, rent-free land grants, and vast expanses of uncultivated land that comprised these agrarian estates into systematized, revenue-paying areas. The state's revenue demand in this early period incentivized many zamindars to sell off portions of their estates, while others became highly indebted to local mahajans, or moneylenders, seeking to take control of new agricultural territories opened up by the colonial administration.Footnote 37

Many zamindari estates quickly fell into arrears after the settlement and were auctioned off at mortgage markets, which generated political instability unanticipated by the colonial state.Footnote 38 In 1798, for instance, the largest zamindari in Manbhum, belonging to the Raja of Panchet, was sold at auction, leading to a sustained outbreak of violence against the English- and Bengali-speaking buyers.Footnote 39 Zamindari insolvency deepened the mismanagement of their agrarian estates as landlords continued to sell off their proprietary titles in exchange for short-term influxes of cash.Footnote 40 Simultaneous efforts by zamindars to take control of rent-free land grants, collect regularized cash payments, and encourage land sales to non-adivasi settlers in the districts led to successive waves of insurrection against the zamindari system, notably in the Bhumij revolt of 1832.Footnote 41 In the aftermath of this and other “disturbances” by adivasi communities, the colonial state reconstituted the plateau region under the exceptional administrative framework of the Southwest Frontier Agency (SWFA) in 1833. The SWFA provided an institutional framework for surveying the “anomalous” conditions of zamindari property in the territory, which led many officials to conclude that the plateau's zamindars required the intervention of the colonial state to protect their properties from dissolution by creditors.Footnote 42

This prescription would come to be revised and institutionalized under the Encumbered Estates Act of 1876, which provided a formal debt shelter for the plateau's zamindars unable to discharge their revenues to the state. The Act was widely applied across the plateau coinciding with the rapid growth of coal tenancies in Manbhum and Hazaribagh after 1870.Footnote 43 It provided zamindars state-appointed debt managers who helped to consolidate the estates by deepening mechanisms of revenue collection and exerting legal authority over contested property claims. The proliferation of coal properties, however, presented a unique area of legal disputation for these debt managers, since much of the legal guidance pertaining to the resumption of zamindari revenues addressed the problem of agricultural tenancies. Because the Permanent Settlement lacked any formal recognition of subterranean wealth as forming the undivided property of zamindari households, both zamindars and debt managers were left to assert dubious legal claims over areas of their estates in which coal had already been discovered and subsequently rented out by subordinate tenants.Footnote 44

Before the extent of coal deposits were known in the plateau, early mining companies had extracted small concessions from local landowners using a land deed that would become known as the coal patta. Coal pattas were modeled on an 1815 coal concession by William Jones, a speculator and cotton screw mechanic who provided the colonial state in Calcutta the first detailed plan for coal extraction in western and northeastern Bengal. Jones's pilot property was a five-year sanad granted to him by one of Bengal's largest zamindars, the Raja of Burdwan, for “all the coal” in what would come to be known as the Dishergarh coal seam.Footnote 45 Even in this early context, Jones and his investors doubted whether the zamindar actually held rights to sell subterranean property deeds, especially in areas of extensive cultivation where smaller landowners controlled both revenue and occupancy rights. This uncertainty led Jones to purchase coal pattas from a range of different types of landowners in order to secure his investment.Footnote 46 Competition to extend coal production in the region after Jones's early venture led to a generalization of these overlapping and contradictory coal concessions. The first geological surveyor dispatched to India, D. H. Williams, noted in 1848 the ubiquity of what he called the “jobbing of coal lands.”Footnote 47 Williams observed that none of the zamindars or their nominal tenants actually knew who held rights to grant coal property, but that “every dependent holder of land” seemed to claim the “mineral wealth of the Empire” as their own.Footnote 48

It was the unresolved status of these subterranean property claims that confronted zamindars and their debt managers in their efforts to reclaim the fiscal value of zamindari estates in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The growing significance of coal to Britain's imperial economy induced various legislative attempts to clarify its proprietary meaning under the Permanent Settlement, but often these produced contradictory justifications for and against the zamindari system as a whole. For instance, Arthur Phillips, a former standing counsel for the Government of India, argued in his Tagore Law Lectures of 1874 that the proprietary right of minerals was separable from permanent grants to land revenue.Footnote 49 This restricted understanding of zamindari property was not shared by those in the colonial state who viewed the Permanent Settlement as a peculiar delegation of landed sovereignty. Such a perspective insisted land and mineral rights were to adhere to zamindars as if they embodied the kingship entitlements of precolonial Hindu or Muslim sovereigns.Footnote 50 These straining interpretations of the common law framework were reflected even in what was considered an authoritative account of the issue in the Indian delegation's presentation to the Royal Commission on Mining Royalties in 1891. The Secretary of State for India Charles Bernard here insisted that the Permanent Settlement assigned coal property rights to “the owner of the surface” land. These rights, Bernard admitted, were not raised during the framing of the law, but that “it has been held since that such was the intention of the Permanent Settlement.”Footnote 51

These deliberations over the ownership of coal property reflected not only the ambiguous position of the law, but the very indeterminant status of zamindari as a legal institution. As I have suggested, zamindari custom in the plateau represented an evolving set of proprietary claims that came to encompass subterranean property, not a preexisting or uniform set of land ownership norms progressively realized by a long-established class of estate holders. Colonial institutions like the Encumbered Estates Act uniquely directed a process of zamindari rationalization precisely at a moment when coal claims emerged as an asset to build zamindari wealth. But the ambiguity of zamindari custom was not only produced within the discursive logic of colonial land policy; it was central to the conflicting legal justifications given by coal companies and subordinate tenure holders as well. In what follows I demonstrate how mining companies were at the forefront in reproducing the zamindari system as the basis for acquiring both coal properties and agrarian labor. The mutability of customary property norms proved valuable under expansive extractive investment, generating new struggles between mining capital, landowners, and cultivators that further heightened the conflictual status of coal within the legal regime intended to govern it.

THE FUEL ESTATE

Like all commodities, Indian coal had to be assembled for the marketplace, requiring both its legal categorization as a form of property and the standardization of measures to translate its natural qualities into economic value. Geological surveying in the early nineteenth century provided one important mode by which the coal resources of the Indian subcontinent became legible to investors in Calcutta and London.Footnote 52 Geological surveys formally emerged as a global imperial technology in the 1830s with the establishment of the “Committee for the Investigation of the Coal and Mineral Resources of India” and the subsequent Calcutta Museum of Economic Geology. These institutions served as the antecedents for the Geological Survey of India, established in 1851 as a permanent scientific body for the mapping, measurement, and publication of all geological knowledge pertaining to the British Empire in the Indian Ocean.Footnote 53

The Museum of Economic Geology and the Geological Survey represented what Bruno Latour has called “centers of calculation,” or sites in which, through replicable practices of translation and transcription, objects fixed in space are rendered into mobile abstractions.Footnote 54 Coal deposits in Bengal, once they were converted into maps and numerical quantities, circulated as objects of both scientific and financial speculation across imperial networks. But the role that such forms of knowledge play in shaping patterns of investment can be misleading. Extraction does not take place in the frictionless space of scientific circulation, but much closer down to earth. Even as geological institutions began systematizing knowledge of Indian coal deposits in the 1830s, coal companies continued to rely on their own agents for the identification of new coal properties in the agrarian estates of the plateau. Much of this had to do with the necessity of finding coal deposits that were relatively close to the surface in order to avoid costly expenditures associated with sinking mine shafts and tunnels.Footnote 55 Beyond this instrumental constraint, however, markets for subterranean knowledge were also spaces of competition between firms. Companies jealously guarded information pertaining to new, so-called “virgin” coal deposits in order to thwart potential mining rivals and to drive down the value of land deeds extracted from unwitting proprietors.Footnote 56

After the period of initial growth in coal production following Jones's 1815 coal concession, the most influential firm to shape the industry prior to the 1890s boom was Dwarkanath Tagore's Bengal Coal Company (BCC). Tagore, an indigo and opium trader, founded the BCC in 1843 out of a partnership that had purchased the sanad and coal pattas of Jones's earlier venture.Footnote 57 In the 1840s, Tagore's firm forged the price of coal by generalizing the procedures through which firms purchased coal pattas, controlled labor, and distributed coal within integrated systems of river steamers, coaling ghats (river frontages), and measures of coal quantity in terms of bucket weights and maunds.Footnote 58 The price of coal, which was forced to compete with the price of bideshi coal (British and Welsh coal imports), remained dependent on bringing down miners’ wages and the costs associated with purchasing property deeds from local landowners.Footnote 59

The BCC created a system of land acquisition based on the purchase of occupancy land for mining infrastructure and the preexisting villages of cultivators living near to its mines. The pursuit of cultivating villages was effectively a strategy of purchasing laborers. As a landlord, the company could coerce ryots (peasants) to work underground in the mines in return for negotiable allowances on rents and their continuing occupancy of agricultural land.Footnote 60 The BCC's conflicts with other firms and landowners in the region, which occasionally spilled over into open violence and sabotage, was most often the result of competition over laboring villages. Because village labor remained tied to the seasonality of the agrarian economy, the short window in which workers could be coerced to leave their fields for coal work generated panicked efforts by foremen to drive as many laborers as possible from the villages into the mines.Footnote 61 These practices of labor and land control, much like coal pattas themselves, functioned on the edge of legality. The BCC was often forced to defend its practices from allegations of terrorizing recalcitrant laborers, destroying rivals’ property, cutting coal it did not own, and forcibly confining landowners who did not submit to its authority.Footnote 62

Controlling land markets remained a central strategy of colonial mining companies following the construction of the first railway connection in the coal region after 1850. As more coal was brought into the market than ever before, new coal concerns were founded by zamindars, Bengali merchants, and European companies along an economic geography produced by railway branch and feeder lines. By the 1890s, however, much of India's richest coal wealth was held by European managing agencies: large, diversified firms that managed multiple joint-stock companies moving capital between Britain and British India.Footnote 63 During the commodity boom, the largest of these coal managing agents, Andrew Yule and Company, purchased the remaining properties of Dwarkanath Tagore's BCC and consolidated them to become the largest private producer of coal in India. By this time, there were 271 coal mines operating in the coalfields of Bengal and the plateau region alone.Footnote 64 Of these, European managing agencies accounted for nearly 86 percent of all invested capital in coal production by 1911.Footnote 65

The growth of Andrew Yule's BCC during the boom was driven by the company's “Zamindari Department.” It was through the lawyers, assessors, accountants, and land surveyors associated with this department that the company negotiated its rights to conduct land surveys, acquire land and revenue-paying villages, and sell off areas of its properties under new types of tenancy agreements. The zamindari logic undergirding the company's business strategies leveraged the capital of its parent firm to buy both coal-bearing and non-coal-bearing land, including forest, agricultural, and pasture land. Early on, the department was also responsible for procuring rice and shifting grain harvests across the company's properties in order to feed laborers working underground. By 1911, the Zamindari Department owned a total of 83,000 acres of land, including 30,000 acres of non-coal bearing land; a figure that by 1920 expanded to 130,000 total acres of land across the coal region.Footnote 66

Image 2. “Miners,” Borea Coal Company Limited. F. W. Heilgers and Co., Diary, 1906. Author's Collection.

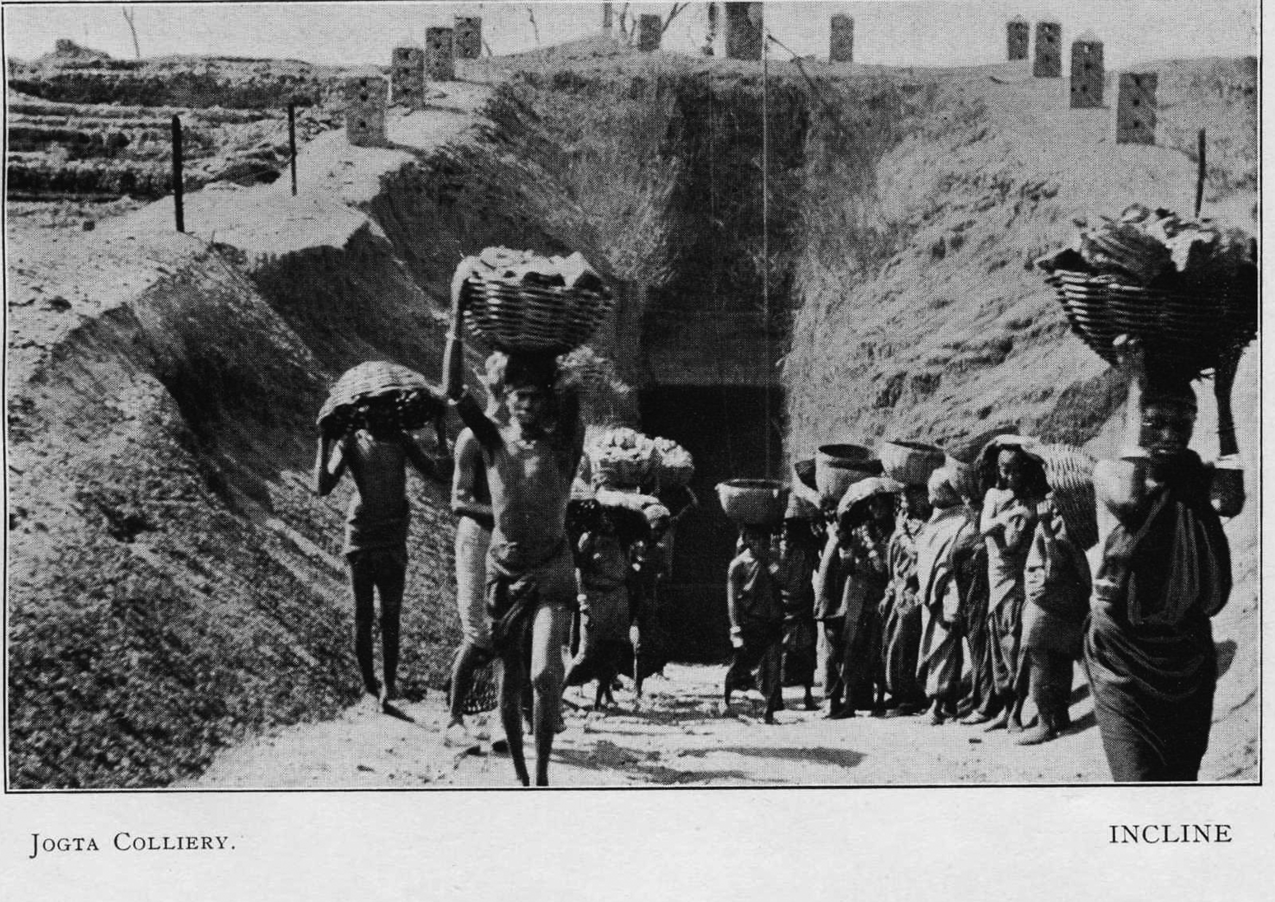

Image 3. “Incline,” Jogta Colliery, Jharia Coalfield. F. W. Heilgers and Co., Diary, 1906. Author's Collection.

The Zamindari Department was fully alive to the legal ambiguity of its expanded coal claims. As such, the lawyers and assessors associated with the company internalized the practices of zamindari landownership, insisting that the company-as-zamindar obtained all of the privileges associated with landowners like the rajas with whom they contracted. The company's land acquisition strategies after 1890 drew from the precedents of the BCC under Tagore. Company documents from that earlier period refer to their practices of acquiring villages for laborers as extending “influence” over these workers, citing what was perceived to be the long-standing customary privileges of agrarian estate holders to command their tenants to work the landlord's demesne. This founding era of the BCC had also witnessed the widespread use of gifts and bribes to obtain privileged consideration of prospective land deeds and monopoly rights to control unsurveyed coal resources over the entirety of an estate. In 1842, for instance, the company had given the Raja of Panchet a watch and a music box for such a consideration.Footnote 67

After 1890, the entire system of negotiating new tenancies in order to keep out competitors was underwritten by what were referred to as salami payments. These informal consideration fees were paid to both zamindars and intermediate tenure holders for accessing agrarian land.Footnote 68 Salami payments could be minimal cash bribes or extensive financial transactions involving the purchasing of company shares or even extravagant gifts like automobiles.Footnote 69 In the coalfields of Raniganj and Giridih, BCC surveyors used these types of payments to acquire customary forms of nokrani, service tenures that resembled forms of bonded labor. Nokrani tenures were traditionally held by cultivators in exchange for periods of unremunerated labor on the zamindar's personal estate, or as tenures that required cultivators to give portions of their own harvest directly to the zamindar. When coal companies acquired these tenures, they converted the service work of nokrani into mine work. In other cases, coal companies would contract with sirdars (labor recruiters/foremen) who would in turn pay advance fees to adivasi village heads who were then tasked with compelling cultivators to migrate to the coalmines.

Coal companies, sirdars, village heads, and zamindars fiercely competed against one another to acquire labor and land for the coal mines. The BCC discovered a singularly effective strategy after embarking on what the Zamindari Department named their New Labour Recruiting Scheme in 1908. The zamindari manager of the BCC, A. Chalmers Hills, realized that the company could purchase forest and pasture land that was shared as common land among several villages, thereby conditioning access to these resources categorized as wastelands in the revenue code, through commitments by cultivators to work in the mines.Footnote 70 By purchasing these commons rights, companies could command flows of labor from adjacent villages that shared use-rights in the commons but which the company did not need to own outright. The quantity of laborers Hills anticipated he could acquire from this procedure led him after one successful venture to declare to his superiors in Calcutta that he had “struck oil.”Footnote 71 Describing the acquisition, Hills wrote: “The mouzah [revenue-paying area] lies in the middle of several labour villages close to our bungalow at Sodepur and the surrounding villages are used to grazing their cattle on the waste lands of said village. If we hold the rights to the lands of this village we shall be in a position to coerce the neighbouring villages to work for us as well as the Porhadiah miners themselves.”Footnote 72

Coal mining in this way aspired to resemble the labor-intensive plantation economies of Indian tea production, and indeed coal companies actively competed against tea recruiters to settle large populations of adivasi and other laborers in the minefields. By 1908, the coal economy employed 112,219 workers.Footnote 73 But unlike tea plants, minework would come to undermine these agricultural origins of the fuel plantation. Coal mining destroyed the landscape of production through its own frenzied logic of accumulation. In the mines, underground coal production was organized by groups of coal cutters under labor sirdars who were responsible for driving the laborers to fill anywhere between two to five coal tubs per day. The profits that sirdars made from the companies depended on the quantity of coal extracted during short work seasons, incentivizing reckless work methods involving the hacking away of underground support pillars, haphazard coal cutting, and working days that lasted between twelve and sixteen hours.Footnote 74

The effects of these new methods of extraction were exacerbated after 1894. Land subsidence became commonplace throughout the coalfields, burying workers and their sirdars in underground workings that collapsed as pillars and support walls were robbed of every last scrap of coal. Subsiding land also destroyed the topsoil and cultivators found their farmlands upended and irrigation catchments destroyed. In areas where companies housed migrant laborers, subsiding land collapsed their makeshift homes and communal gardens, often killing entire migrant families in unexpected ruptures that split the earth into pieces.Footnote 75 Coal companies became purveyors of a broken landscape. In one case from 1907, for instance, the BCC attempted to sell one of its mines even as the landscape around the mine was subsiding. “Send a representative as soon as possible … this is very urgent, as certain parts of the district being worked are coming down fast,” the Company's assessor wrote while making a final accounting of the mine's sale value.Footnote 76 In other cases, companies closed down mines afflicted by subsidence, fires, or monsoon flooding, only to reopen them when the value of coal was such that profit outweighed risks to laborers or the landscape.Footnote 77

It is difficult to assess with any accuracy how much land came to be destroyed by coal mining during this period, but company and government records are filled with cases describing such events. Indeed, during the interwar period the British Indian government was forced to take up the matter of coal conservation due to the industry's destructive methods of working the landscape and adopted the label “slaughter mining” to describe the Indian coal sector.Footnote 78 The problem was especially acute in the anthracite coalfield that formed the ancestral estate of the Raja of Jharia. Mining firms had produced a patchwork of abutting coal claims amidst railway feeder lines that moved Jharia's anthracite into the larger railway distribution network. Intense competition for underground seams led to the outbreak of fires across the coalfield. Land owners cut away at their own and their neighbors’ coal properties, thereby reducing underground support for the heavy shale topsoil and the railways carrying coal above.Footnote 79 The result was a subsiding and burning landscape that periodically shut down railway traffic, collapsed coal stations and feeder lines, and sent flames and smoke streaming throughout Jharia's many underground caverns.Footnote 80 By the mid-1930s, more than a third of Jharia's collieries were in flames.Footnote 81

Image 4. “Bombay Coaling Depot,” F. W. Heilgers and Co., Diary, 1906. Author's Collection.

This destruction of the land, as much as the extension of geological surveys, made visible that the mining landscape was composed of three-dimensional property claims that compromised agrarian territory. Rights of cultivation and rights to mine coal intersected at the point of the landscape's collapse. The clear inability of existing revenue laws to govern the acquisition of coal property threatened the increasing capitalization of the landscape after the 1890s, even as companies continued to shift the costs of extraction onto the laboring and cultivating communities making their lives above the mines. But the newfound profitability of British India's coal resources led to renewed efforts to clarify property rights, while a wave of litigation over preexisting mining claims entered colonial civil courts. At stake in these court cases was not simply the clarification of existing market transactions in land, but also deciphering who, under the law, held rights to monopolize the future value of the subterranean wealth of the plateau.

MAKING PROPERTY AFTER THE COAL BOOM

The commodity boom thus occurred within a context of changing agrarian social relations, as zamindars, intermediate tenants, and coal firms competed against one another to control agrarian land and labor. When coal entered colonial courts in new litigation after 1894, colonial jurists were confronted with a reality that had long been clear to coal companies and land speculators: the law lacked any explicit definition of coal's status as property. This is not to say that coal lacked a definition of proprietary right once it was, as a commodity, excavated from the earth and distributed to various merchants and companies to be consumed as fuel. Such transactions could be governed quite easily by commercial law. What was missing in the law was a clear understanding of to whom coal belonged before it was transformed by human labor and rendered up to the market.

Zamindari attempts to reclaim the subterranean wealth of their agrarian estates were supported by the legal infrastructure of the Encumbered Estates Act. But the claims of zamindars and their debt managers represented something of a jurisprudential anachronism. Colonial lawmakers were increasingly predisposed to the decentralization of zamindari property in favor of tenant protections, a viewpoint grounded in what was known as the Punjab or historical school of agrarian reform.Footnote 82 The most substantive articulation of this perspective was the 1885 Bengal Tenancy Act, which established wider protections for intermediate tenants by limiting zamindari authority.Footnote 83 This legal trend towards tenant protection impacted the coal region at the very moment of the commodity boom. At the turn of the twentieth century, a mass uprising of Munda and Oraon adivasi groups in the central plateau led to the most radical breakthrough of tenancy reform yet, the Chotanagpur Tenancy Act of 1908 (CNTA). The CNTA provided expansive customary rights to adivasi groups while restricting the sale of adivasi land to non-adivasi communities. The retrospective application of the CNTA would have had significant implications for both coal companies and zamindars, calling into question the very land acquisition practices that had attended the industry's rise.

The civil court discussions regarding coal property during the boom, however, largely began with debates focused on zamindari entitlements first raised in the 1860s.Footnote 84 Commercial groups in Calcutta at that time were worried that the growing importance of Indian coal to Britain's imperial economy would result in the state declaring coal a government monopoly, thus depriving them of a profitable source of investment. Indeed, these groups recognized the peculiarity of an arrangement that ceded absolute mineral property to agrarian landholders in the zamindari tracts, whereas in other areas of British India these rights were vested as the sovereign property of the colonial state. In 1875, some clarity in the law was granted by a ruling from the Advocate General of Bengal, Sir G. C. Paul, who had argued that in cases where zamindars had sub-leased their land to intermediaries, property-in-coal would revert to the zamindar unless the sub-lease deed expressly conveyed the granting of coal rights to the intermediary.Footnote 85 Paul's ruling was recognized by subsequent civil court decisions as upholding the belief that the Permanent Settlement implied zamindari rights in coal. In 1880, the Secretary of State for India further issued a declaration that the unstated property right of coal under the zamindari system did not prevent a future appropriation of coal resources by the state, but that the government deemed such an action impolitic, and thus temporarily ceded subterranean property to the zamindars.Footnote 86

Barring any statutory intervention, the allegedly customary status of coal largely meant a reversion to this zamindari prerogative, a position frequently upheld in civil litigation by cautious judges. This tendency was challenged, however, following a civil case in 1906 involving a zamindar who had attempted to prevent an intermediate tenant from selling their coal rights to a mining company. In the appeals cases that followed from the original verdict, Calcutta High Court Judge Sir Asutosh Mukherjee analyzed the language used in an original 1865 sub-lease which invoked a common Persian contractual refrain, mai haqq-huqūq, translated as “with all rights and privileges thereunto pertaining.” Mukherjee argued that haqq-huqūq was not to be interpreted as merely a revenue collecting right, but indeed as a right to physical property.Footnote 87 By arguing that the sub-lease deed conveyed physical property to the intermediate tenant, Mukherjee was staging an intervention within existing debates in the civil courts over the definitional status of both minerals and land.Footnote 88

The existing legal terminology for grappling with such terms had often been limited by legal efforts to identify the meaning of minerals. The 1885 Land Acquisition (Mines) Act, which provided the legal framework for the valuation and purchasing of coal properties by railway companies, deferred any pronouncement on the statutory definition of minerals. The Act stated there could be “no fixed principle upon which the courts will interpret” the meaning of the word because it varied so widely in individual circumstances.Footnote 89 An 1894 ruling from outside the Jharia coalfields struggled to define even a minimal definition for minerals, arguing interchangeably that minerals formed a common category insofar as they required manual labor for their excavation, as well as the possibility that minerals might be understood as “every substance which can be got from underneath the surface of the earth for the purpose of profit.”Footnote 90 In a later case, from 1906, one of the most prominent Bengali zamindars, the Maharajah of Cossimbazar, argued in a case on the taxation of his coal royalties that, under the law, unworked coal should be understood as a form of latent capital which is only converted into taxable money through the production process.Footnote 91

However, rather than seeking a precise terminology of minerals, Mukherjee's analysis of the language of the 1865 sub-lease agreement pushed the court to clarify the intended definition of land. Mukherjee argued that if the court was to regard the sub-lease agreement as a conveyance of land then the category ought to be understood in terms of the solum. Arguing from William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, Mukherjee wrote, “It is well established that a contract to sell or grant a lease of land will generally include the entire solum from the surface down to the centre of the earth, and will, therefore, include the mines, quarries, and minerals beneath it.”Footnote 92 Mukherjee's invocation of the solum appropriated a legal theory of dominium, the basis for instance of the Roman-Dutch mining laws of colonial South Africa, but applied it to a category of intermediate land holding not typically recognized to have such extensive rights.Footnote 93 Indeed, dominium typically referenced the type of quasi-sovereignty over physical space that defenders of the Permanent Settlement ascribed to zamindars.

This expansive, transhistorical conception of propertied space represented an attempt to overcome a major problematic of the sub-lease system, namely, that the majority of sub-lease agreements were executed before the presence of coal in the landscape was fully known. Thus, without a categorical definition of land accepted by the courts, the categories of land named in such sub-lease agreements could not be said to imply a right in a resource neither the deed-granting party nor the grantee knew existed. Mukherjee's turn towards the solum as a reasoned definition of land stemmed out of an inability to adjudicate an array of sub-lease agreements whose invocation of “land” seemed entirely derived through conflictual interpretations of local context. If the zamindar could agree that their own landholding was served by a definition of the solum—which they most certainly did—then perhaps such a uniform definition of land was generalizable to sub-lessees.

Mukherjee's interpretation built on previous attempts to define the meaning of land under the Permanent Settlement. In one 1892 compensation case the Calcutta High Court failed to decide what definition of land should be used to interpret a mining title. The court thought to use the definition of land included in the Rent Law of 1859, which understood land as “the surface of the earth in a condition such that, by the aid of natural agencies, it may be made use of for the purposes of vegetable or animal reproduction.”Footnote 94 But because the property in question fell under the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885, in which the court maintained there was no clear definition of land, the court felt compelled to take “land” as a broader category, possibly including mineral subsoils. This type of definitional ambiguity extended to the category of “wastelands,” which, under the Permanent Settlement, allowed zamindars to declare vast areas of forest and pasture land used by cultivators as common property the individual property of the estate.Footnote 95 Zamindars also came to use the wasteland category to assert their coal property claims, a prerogative with well-documented precedent in English common law for ascribing subsoil property rights to superior landholders even in the case of preexisting informal sub-tenancies.Footnote 96

Ultimately, however, Mukherjee's attempt to legislate coal claims through a uniform definition of land was not to hold. Returning to Mukherjee's ruling in a 1911 case between the Raja of Panchet and the Lachipur Coal Company, the presiding civil court judge ruled against Mukherjee's earlier invocation of the solum. The 1911 case exhibited many of the troubling facets of coal tenures that had led Mukherjee to his earlier decision. The Raja of Panchet had sub-leased an extensive tract of land to intermediate tenants who in turn sub-leased the land's coal resources to a private company in 1858. In analyzing deed documents from the case to decide whether the Raja ever held preexisting underground rights, the judge discovered two contradictory events. It appeared that in 1877 the Raja had in fact purchased underground coal rights from his own intermediate tenant in order to lease them to a coal company himself. At the same time, the judge was given documents from the Bengal Coal Company dating to the 1850s which showed that the company had taken coal rights directly from the Raja.Footnote 97

Read together these events expressed the inconsistencies of legal practice that grew out of the absence of any explicit legal right to coal property. The Raja was, through the admissible evidence stated above, both recognizing his right to coal property and affirming the same recognition of right in his intermediate tenant. The resulting inability of the court to adjudicate on precedent led, once again, towards a discussion of definitions. The judge here eschewed Mukherjee's insistence on the category of land as the primary legal optic by instead invoking statutory definitions outlined under the Transfer of Property Act of 1882, which provided a fundamental distinction between mines and minerals. Minerals, the court reasoned under the Act, belonged to the soil, and thus represented the indissoluble property of the zamindar. Mines, on the other hand, represented changes made to the land by labor and could thus pass as a form of assessable property from one owner to another.Footnote 98

Image 5. Three-Dimensional Property. “Coal Seam Burnt to Ground-Water Level,” Photograph by C. S. Fox for the Geological Survey of India, Bhowra Quarry, Jharia Coalfield. C. S. Fox, Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India, vol. LVI (Calcutta: Government of India Central Publication Branch, 1930).

The judge further reasoned that to understand a sub-lease of land in terms of the solum marked an overly modern interpretation of tenant right that was inapplicable to Indian custom.Footnote 99 Implying as it did a conception of property in land that united topsoil and subsoil under the principle of exjure naturae, or the unity of possession, such a right would effectively dissolve zamindars as meaningful property owners. Instead, by vesting the unworked resources of coal subsoils in the permanent property of the zamindar, the law could effectively recognize both the rights of zamindars to the coal and the rights of other tenants and cultivators to the land. This was the legal innovation of invoking the Transfer of Property Statute, particularly at a moment when new cultivators were being awarded land titles under reforming laws like the CNTA. Subsequent cases continued to debate the full implications of this legal distinction between topsoil and subsoil as discrete spaces of property holding, but the case served a vital function of precedent. Rather than discussing coal as a subject of agrarian law, and thus through idioms of land, the invocation of the Transfer of Property Act helped to shift coal from discussions of landed entitlement to a law governing the commercial exchange of property rights.Footnote 100

The image of discrete spheres of property holding may have suggested a neat classificatory schema, but in reality, coal remained intermixed in a landscape of topsoils and subsoils, a sedimentary bed integrally part of the region's agroecologies. Coal mining, as we have seen, abetted the increasing destruction of this landscape, denying the long-term possibility of agrarian cultivation to subsist alongside expanded fossil fuel production. The reality of this violent political ecology of coal, and the law's inability to protect agrarian property, came out in the land surveys of the eastern plateau region at the same moment that the courts were deliberating the property question. These surveys were spurred by the passage of the CNTA in 1908 and intended to provide the first surveys of agrarian property-holding regions. Because tenants lacked recourse to revenue surveys, officials realized that any tenancy protections, no matter how expansive, were easily obscured or manipulated by both zamindars and coal companies. As B. K. Gokhale wrote in his final report from surveys undertaken between 1918 and 1925,

It was almost a daily occurrence during attestation to find land which had been surveyed as cultivated rice land or upland in possession of raiyats (cultivators) to have become waste land in possession of mine owners or unculturable land due to the dropping of the surface on account of the extraction of coal below. It was rare in such cases for the raiyats to get compensation expeditiously and at anything like fair and equitable rates. Generally, the raiyats had to submit and see even their best lands taken possession of by mine owners, at very short notice or in some cases, even without previous notice. The mine owners generally arrived at some sort of agreement with the landlords and either ignored the tenants altogether or placated them by giving a small sum as advance.Footnote 101

The law of property for coal thus encoded these histories of dispossession within its apparent affirmation of juridically equal property rights. Settlement operations, Gokhale would later note, came to the coal region “twenty years too late.”Footnote 102 When the CNTA was set to be amended in 1927, colonial officials noted that regardless of tenant protections it was “inevitable” that coal companies would get access to the land “whether transfer is permitted or not.” The needs of the industry “must in any case be satisfied,” one Revenue Department official opined, in spite of the “grave injustices” that attended its expansion.Footnote 103 As coal and agrarian land were split within the categories of the law, the land itself was no longer viewed by many in the colonial state as a patchwork of agrarian cultivation and forest land; it had become an abstract space governed by the value of the minerals beneath it. Indeed, officials revising laws like the CNTA became increasingly unsure whether the purview of tenancy law could even apply to the acquisition of coal. In the words of one official commenting on the futility of legislating coal through tenancy laws: “The mine-owner has no use for cultivating rights: he wants the land.”Footnote 104

CONCLUSION

In this article I have argued that India's coal economy emerged through contestations over agrarian property rights in the context of the underdetermined legal status of coal. Agrarian political economy, coded in terms of the customary legal framework of the Permanent Settlement, fundamentally shaped the practices of land and labor acquisition employed by coal companies and powerful landholders. In the absence of any clear definition of coal property rights, these groups traded agrarian land as if coal property inhered in such titles. The transformation of the agrarian landscape into a space of extractive industry thus occurred within the interstices of colonial law. Colonial civil courts subsequently responded to this absence in the law by embedding informal practices of agrarian dispossession and ecological degradation within a legal framework that recognized the permanence of zamindari rights in subterranean properties.

The implications of this argument are twofold. First, the unresolved contradiction between an agrarian topsoil vested in cultivators, and a mineral subsoil vested in zamindars and coal companies, points ahead to twentieth-century struggles over land in the mining region. The law-making observed in this article defined coal property until the postcolonial state enacted policies to abolish the institution of zamindari during the 1950s. This decision was guided by the recommendations of the industrialist K. C. Mahindra's Coalfields Commission of 1946. Drawing on the authority of the ancient Indian treatises of the Manusmriti and Kautilya's Arthasastra, the report concluded that Indian legal traditions assigned subsoil wealth to the sovereignty of states, not private property holders.Footnote 105 This mode of legal reasoning did not, however, represent the overcoming of zamindari property as a social form embedded in the histories narrated here. Rather, it reapplied the juridical method formerly grounding the Permanent Settlement as a legal justification for the postcolonial state to become, effectively, a coal zamindar. Neither in the nominal turn to zamindari abolition in the 1950s, nor in the subsequent nationalization of the coalfields after 1970, did the postcolonial state address the issues of tenant rights and agrarian displacement raised during the coal boom. In fact, the urbanizing and industrial projects of the postcolonial era accelerated the expansion of coal mining across wholly new agrarian and forest regions under the presumption that the status of coal was a settled juridical field. It is not surprising, then, that even in the present moment, adivasi movements contesting land acquisitions enacted by the postcolonial state mobilize claims to land and territory that remain tied to the pro-tenancy legal conceptions like those embodied in the Chotanagpur Tenancy Act of the early twentieth century.Footnote 106

Second, by documenting how categories of property holding were created within the historical contingencies of coal extraction, this account complicates our understanding of the role of property within the legal history of capitalism. We see here how property rights can emerge from, and subsequently justify, processes of capital accumulation. This attention to the temporality of law-making is not merely to observe the belatedness of law in relation to social practice, but to challenge formalist accounts of the structuring of economic life by law. Rather than viewing the law as either an autonomous epistemic space that produces markets, or as the functionalist result of interventionist efforts to modernize inefficient forms of custom, this article situates the law in terms of its persistent attachments to customary and legally ambiguous conventions extending beyond the boundaries of positive law.Footnote 107 This perspective draws from what Ritu Birla has identified as the performative role of law in appearing to disembed “the economy” from broader webs of social relations.Footnote 108 Stable signifiers like “property rights” seem to generate the frictionless space of market transactions, while framing custom and informality as the vestigial barriers to the rule of capital. As I have suggested here, custom and capital were produced together in the mining frontier.

Using property, and its absence, as a method of assembling the history of India's fossil fuel economy allows for a more opportunistic understanding of colonial capital. My intention is not to suggest the counterfactual that if some type of positive law had been more evenly applied, or if zamindari custom had not been substantiated by the colonial courts, a less socially and ecologically destructive version of coal mining might have emerged. I have instead endeavored to point out how property regimes are constructed under capitalism, and yet appeal to normative principles that appear outside of it.Footnote 109 Understanding this duality is especially important in confronting the legal claims of extractive industries that seek to substantiate their subterranean rights as continuations of settled legal norms. The global proliferation of such claims during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries comprise what Gabrielle Hecht has recently called a history of “verticality” that challenges the way we think about property and the forms of equivalence property discourses produce.Footnote 110 Extending analyses of property rights downward to fossil fuels reveals how a multi-scalar energy system entered into the legal vocabularies and lived realities of diverse material environments. These histories of property-making reflect ongoing struggles over land and natural resources, and the contingent formation of a legal order that has sought to manage and mitigate, rather than fundamentally challenge, the still unfolding ecological crisis of extractive capitalism.