In her long durée history of vital needs, Dana Simmons recently showed how the struggle for labor reform and decent pay in fin de siècle France was tied to a discourse about vicious and superfluous needs that were supposed to corrupt the nation. While socialists fought for structural reform of the workplace, conservatives argued for the rationalization of the spending habits of women who were either immoral, ignorant, or both.Footnote 1 The discourse examined by Simmons was not unique to France. As we will argue in our contribution to this special issue, the same discourse can be found in the early Progressive Era in the United States, where one group of reformers aimed to solve the social question by institutional reform of working and living conditions of the urban poor, while others concentrated on educational programs to rationalize their needs. We will take socialist and labor reformer Florence Kelley and MIT’s first woman chemist Ellen Richards as exemplars of women reformers whose reform strategies related to these different sides of the social question: While Kelley canvassed for the reform of working conditions, Richards concentrated on the reform of the vital needs of the household into a homogenized American mold that celebrated individual over institutional change.

Kelley and Richards’s reform strategies briefly met in 1893, the year of the Chicago World Fair, at Hull House, one of the prominent sites of the American settlement movement (see figure 1). Located at the crossroads of South Halsted and West Polk Street in today’s Chicago West Loop, at the time one of the poorest Chicago slums, Hull House attracted many women social reformers interested in new forms of education and social support for the largely immigrant class of working poor. On its rapidly expanding premises, Hull House first introduced a kindergarten, a library, a variety of cultural clubs, and then also a public kitchen, which had been developed by Richards in Boston as a site of experiment on dietary habits. At the time, Kelley was living and working in Hull House, conducting social surveys in its surrounding slums to collect evidence on the evils of the sweatshop system that was all-present in Chicago’s garment industry.

Figure 1. Hull House at the crossroads of South Halsted and West Polk Street, around 1900. The library building is on the left, the public restaurant and cafeteria, with take-away meals cooked in a New England Kitchen, are on the right.

Source: Hull House photographic collection, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago, call mark JAMC_0000_0132_0150.

In her history of poverty research in the United States, Alice O’Connor makes the useful distinction between structural and cultural reform programs, which overlaps with Simmons’s distinction between the reform of labor conditions and the reform of an individual’s needs. Structural reform programs aim at institutional change and cultural reform programs at the change of individual behavior. O’Connor discusses Kelley’s social surveys and their impact as part of a structural reform program, but she misses the importance of dietary research as a strategy of cultural reform (O’Connor Reference O’Connor2009). As Harvey Levenstein (Reference Levenstein1980) reminds us in his history of the New England Kitchen, no cultural habits are more persistent than food habits. While Florence Kelley used the social survey to provide lawmakers with evidence in support of legal reform of labor conditions, Ellen Richards’s food research focused on the improvement of the socio-economic position of the poor by changing their food habits. O’Connor’s distinction between structural and cultural reform thus captures the contrast between social reformers who used the social survey to enforce structural change in working conditions and liberal reformers and scientists who brought nutrition research from the laboratory to the public to change its behavior, while leaving working conditions to the whims of the market.

In what follows, we contrast the reform strategies of Kelley and Richards to see how they entailed different diagnoses about the root causes of social harm and its remedies. This is not just a matter of ideas, but of research practices at specific sites of social reform. We will concentrate our discussion on their preferred methods of research and on the propagation of the results of their investigations into the public sphere. Hull House, Kelley’s “walks” through the Chicago slums, and the New England Kitchen at the 1893 Chicago World Fair will play an important role in our story.

Florence Kelley, Hull House, and the anti-sweatshop system legislation

Let us start with Florence Kelley and the social surveys she conducted, first for the Illinois Congress and then as Factory Inspector for the Illinois and Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. Florence Kelley Wischnewetsky (1859-1932) moved from New York to Chicago, seeking refuge with her three children from an abusive husband. When she first crossed the doorsteps of Hull House “on a snowy morning between Christmas 1891 and New Year’s 1892,” she felt “welcomed as though we had been invited” by the women who lived in this social settlement in one of the poorest slums of Chicago (Sklar Reference Sklar1985, 660). Hull House was an important center of the American Settlement movement, situated in the nineteenth ward at the west end of Chicago.Footnote 2 The founders of Hull House, Jane Adams and Ellen Gates Starr, arranged with their friends Jesse Bross Lloyd and the famous muckraker journalist Henry Demarest Lloyd to take care of Kelley’s children at their home in Winnetka, where they stayed on and off for the six years that Kelley lived and worked at Hull House.Footnote 3

With Hull House as her unconventional home base, Kelley quickly became one of the main spokespersons of the working-class movement in Chicago. She conducted social surveys, first as employee of the Illinois Bureau of Labor Statistics for the Illinois Congress and then as factory inspector for the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, on the so-called sweatshop system that dominated the surrounding immigrant neighborhoods. For these surveys, Kelley and her collaborators made door-to-door visits to inspect labor and living conditions of the Chicago working poor. These surveys are commonly considered as one of the starting points of the social survey movement of the American Progressive Era (Bulmer, Bales, and Sklar Reference Bulmer, Bales and Sklar1991; Greenwald and Anderson Reference Greenwald and Anderson1996). They led to important changes in labor regulations for women and child labor, most notably through the famous Brandeis brief for the American Supreme Court in 1907 in Muller v. Oregon, in which social science data on women’s health collected by Florence Kelley and Josephine Goldmark, Kelley’s first biographer, were for the first time accepted as court evidence (Vose Reference Vose1957, Bernstein Reference Bernstein2011, Morag-Levine Reference Morag-Levine2013). Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter considered that Florence Kelley “had probably the largest single share in shaping the social history of the United States during the first thirty years of this century” (Goldmark Reference Goldmark1953, v).

Florence Kelley was born on September 12, 1859, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the daughter of Caroline Bartram Bonsall (1828-1906) and U.S. congressman and strict abolitionist William Darrah Kelley (1814-1890). William Kelley was one of the founders of the Republican Party, and a close friend of Abraham Lincoln. As a congressman, he became known as pig-iron Kelley, because of his unwavering support for the tariff to protect the Pennsylvania steel industry. At the age of sixteen, Florence Kelley began studying at Cornell, where she became a Phi Beta Kappa member. She did not graduate until 1882, partly due to illness, but also because a lack of reliable statistical data made it difficult for her to complete her bachelor’s thesis on the changing legal status of the child.

As a woman, Kelley was denied advanced studies for a law degree at the University of Pennsylvania. She therefore went to Zurich, where she attended courses in political economy and the social sciences. At the time, Zurich was a hotbed of socialists, and one of the few places where women could obtain a master’s degree. She became a socialist who believed in the central importance of Marx’s theory of surplus value and its concomitant analysis of the class conflict between labor and capital. She met Friedrich Engels, with whom she kept in correspondence, and translated his Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, a book that in many ways colored her later path in life (Blumberg Reference Blumberg1964).Footnote 4 This translation, on which she worked from 1884-1887, was the only one in English until 1948.

Very much against the wish of her parents, she married the Russian medical student and socialist Lazare Wischnewetzky in 1883, which led to a rift that would only heal shortly before her father’s death. The couple perceived the Hay Market riots in May 1886 in Chicago as the moment capitalist class struggle had reached America, and decided to return to be part of this revolutionary moment. They settled in New York, where Kelley became involved in the (German speaking) socialist party. Her husband failed to secure a stable position as a physician, which forced them to turn to Florence’s family, despite the rift, for financial support. Wischnewetzky became increasingly abusive, especially after Kelley began using English for daily conversation with their three children. It would take another eight years after her escape to Hull House in late 1891 before they divorced and the specter of losing her children to her husband vanished.

The American settlement movement was inspired by the philosophy of William Ruskin and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain, and by London’s Toynbee Hall, which aimed to disrupt class barriers and improve the lot of the poor by bringing education and culture to the slums—not through charity, but by living among and with the poor. Most American settlement houses were managed by women of the (upper) middle class. Hull House, established by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr at the crossroads of South Halsted and West Polk Street, was no exception. Addams and Starr founded Hull House in 1889, after a tour through Europe, during which they had visited Oxford and Toynbee Hall in London. Beginning with a child nursery, the house quickly expanded its functions and became a center that offered education and other services to the local, mostly immigrant community.Footnote 5

The settlement movement in the United States was closely related to the Social Gospel, but Hull House was special in that Jane Addams invested a substantial part of her personal fortune in its development. Addams conceived of Hull House as a social experiment that should adapt itself, in line with its Ruskinian moral philosophy, to new initiatives and changing circumstances. Within a few years, the place provided a base and space for a multitude of (women’s) clubs, educational initiatives, and music and theatre performances. Hull House thus came to function as a family home for the neighborhood. Run by women and largely for women, Hull House was a settlement that, as Kelley’s biographer Kathryn Sklar notes, “conveyed the feeling of a home,” but which, in contrast with settlement houses depending on Christian charity, could afford itself an activist profile for social change (Sklar Reference Sklar1995, 191). This profile was enhanced by the arrival of Florence Kelley in 1891, which “galvanized” Hull House, as Addams remembered, “into more intelligent interest in the industrial conditions all around us” (Addams Reference Addams1935, 82).

Kelley’s involvement with the socialist party in New York meant that she was already well-acquainted with the labor movement in Chicago when she arrived at Hull House. In the aftermath of the Hay Market riots, labor activists, such as Mary Kenney, Elizabeth and Thomas Morgan, and Abram Bisno, had concentrated their activism on the evils of the sweatshop system that permeated the Chicago garment industry, mobilizing the press and gathering statistical evidence to expose its evils. Garment factories outsourced their work to sweatshops, that is to workplaces in private dwellings and family homes where men, women, and children were contracted by their owners—the sweaters—at race-to-the-bottom contract prices that followed a strict division of labor between immigrant communities. In 1888, the Chicago Tribune published a series of investigative articles called “Slave Girls of Chicago,” and in 1891 Elizabeth and Thomas Morgan published a pamphlet for the Chicago Trade and Labor Assembly entitled “The New Slavery: Investigation into the Sweating System as applied to the Manufacture of Wearing Apparel.” The combination of political and social pressure, and the evidence presented in these and other publications, enlarged the base of resistance to the sweatshop system among the Illinois middle and upper classes and prompted the State of Illinois to start an investigation into the Chicago sweatshop system.

Kelley had thus arrived in Chicago at the right moment. In need of work to pay the (modest) rent for Hull House, and at the suggestion of Jane Addams, Kelley took up a job with the Illinois Bureau of Labor Statistics, to which this investigation was promulgated. She visited between 900 and 1000 tenements, of which she retained 666 for her report.Footnote 6 Residents of Hull House remembered her swollen feet from her walks through the neighborhood. This survey was subsequently enlarged for the 1894 report of the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) on the slums of America’s east coast cities, which was commissioned by the House of Congress and supervised by the director of the BLS Carroll D. Wright (Wright Reference Wright1894).Footnote 7 Under Kelley’s guidance, four men in the service of the Bureau of Labor Statistics devoted their entire time for the week of April 6, 1893 to an examination of “each house, tenement, and room in the district, and filling out tenement and family schedules” (Holbrook Reference Holbrook1895, 7).

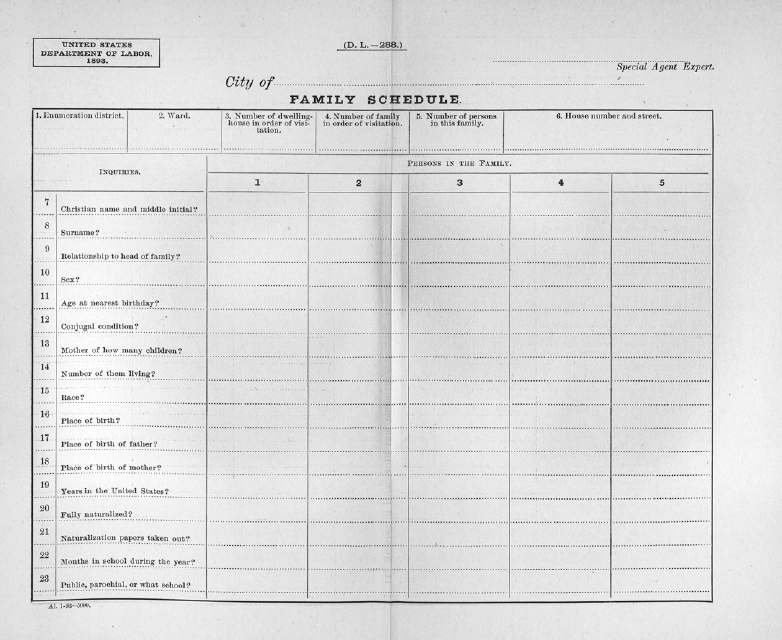

Wright designed the questionnaires for these surveys, which he based on the American census forms (see figure 2).Footnote 8 They included more than sixty questions about the state and the status of the tenement (sanitary conditions, ventilation, number of tenements in the building etc.), the use and dimensions of the rooms, the composition and working conditions of the families living in these tenements. The fact that the local population was acquainted with the community service work of Hull House and approved of its activities helped Kelley gain access to the tenements in the neighborhood, but it also increased her trust in the answers. And in those cases where sweaters refused her entry, the fact that the survey was commissioned by the Illinois Congress guaranteed her access. Her first report was published in 1892 and led to the State’s anti-sweatshop regulation of 1893 (see also Waugh Reference Waugh1982).

Family and tenement schedules used for Kelley’s surveys on the sweatshop system.

Source: Hull House Maps and Papers. 1895. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co. The schedules appear appended to p. 4. We would like to thank Dan Bouk for sending us high resolution scans of these schedules.

Both Elizabeth Morgan and Florence Kelley drafted a version of the bill, but Kelley’s more radical version, which recommended an “ambitious expansion of state authority” and the establishment of an office of factory inspection, became the blueprint of the final bill (Sklar Reference Sklar1995, 234). To get this law through, Kelley had to maneuver between the conflicting interests of the different labor unions and political parties, which she did in close collaboration with Labor Union front man Abram Bisno, a Jewish immigrant from Ukraine whose family had fled to the United States after the Kyiv pogrom of 1881.Footnote 9 The resulting law proposed to curb the sweating system by prohibiting children’s work below the age of sixteen and restricting working hours for women to eight hours. It was unanimously approved by the Illinois Congress and Governor John Peter Altgeld subsequently appointed Kelley to the new post of Chief Factory Inspector for the State of Illinois.Footnote 10 However, the success of the sweatshop campaign proved short-lived. Challenged by the Illinois Manufacturers’ Association in Ritchie v. People, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in 1895 that restricting working hours to eight hours only for women violated the fourteenth amendment’s guarantee of freedom of contract.Footnote 11

The social survey as a book of grievances

Historians of social science and statistics have commonly focused on Kelley’s spectacular visualization of her social survey, with the colored wage and immigrant maps that accompanied the Hull House Papers and Maps, and on the scientific soundness of her methods of surveying (Bulmer, Bales, and Sklar Reference Bulmer, Bales and Sklar1991; Greenwald and Anderson Reference Greenwald and Anderson1996). Published in 1895, the book collected essays from the Hull House community, offering a vivid impression of the social conditions of the neighborhood and of the activities undertaken for their improvement. The book was published as the fifth volume of Wisconsin economist Richard T. Ely’s Library of Economics and Politics, but only after Ely capitulated to Kelley’s threat to withdraw her cooperation in response to his suggestion to suppress the maps. Kelley insisted that “the charts are mine to the extent that I not only furnished the data for them but hold the sole permission from the U.S. Department of Labor to publish them. I have never contemplated, and do not now contemplate, any form of publication except as two linen-backed maps or charts, folding in pockets in the cover of the book, similar to Mr. Booth’s charts” (Sklar Reference Sklar1995, 278).

In her introduction to the Hull House book, Agnes Sinclair Holbrook wrote that the maps of Charles Booth’s London poverty project had served “as a warm encouragement” for Kelley’s visualizations (Holbrook Reference Holbrook1895, 11).Footnote 12 But instead of being the start of an investigation into the causes of poverty, as in Booth’s case, Kelley’s maps served as public exhibits to show what her survey had confirmed: the exploitative nature of the sweatshop system. The keys to the maps show these differences in purpose. Instead of Booth’s moral classification of poverty, Kelley’s color codes referred to different wage levels, without reference to poverty, in one set of maps, and to different immigrant populations in the other. Combined, the maps displayed the geographical correlation between wage-levels and immigrant groups, which Kelley had explained in her report for the Illinois Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Hull House Maps and Papers was published in 1895, after the sweatshop campaign that led to the Illinois Factory Act of 1893. This campaign gained steam with the State of Illinois gubernatorial election in Fall 1892, which was won by John Peter Altgeld on a Democratic ticket. In fact, in the run-up to the Chicago World Fair, none of the candidates proved willing to defend the sweatshop system. Public meetings were organized that made the wealthy part of Chicago aware of the conditions under which their garments were produced, sometimes for audiences as large as 2,500 people. One of the arguments was that these labor conditions made the garments unfit for consumption because they were a health threat. Joanna Waugh noted how, on a meeting of February 19, 1893, at Chicago’s Central Music Hall, with Demarest Lloyd, Florence Kelley, and Mary Kenney as its speakers, a “grim display of ‘infected’ cloaks and shirts taken from various sweatshops reminded the listeners of the ever-present dangers of unregulated sweating labor” (Waugh Reference Waugh1982, 31). Thus, when Kelley started working on her social survey, her report did not just serve to chart the facts, but rather to show the evidence and advocate for social change (Furner Reference Furner2011). It functioned as a cahier des doléances, as Simmons acutely observes of similar statistical work in the French case—as a book of statistics that served as “accusatory evidence against capitalist exploiters” (Simmons Reference Simmons2015, 96).Footnote 13

Garnering momentum for social change

While working on her report for the Illinois Bureau of Labor Statistics in 1893, Kelley invited Congress committee members and journalists to join her on her visits of the tenement dwellings, thus garnering support for its findings. These tours started with Hull House as beginning and endpoint and were covered by the press. The February 12, 1893 issue of the Chicago Tribune reported on one such tour in terms of the survey’s questionnaire:

In the rear of a fine brownstone … the committee found a typical “sweat shop.” Amid the whir and din of a gas engine and twenty sewing machines twenty girls and four men were found at work in a room 20 x 36 feet. Several of the girls were apparently not 13 years old, but when asked their ages they replied that they were much older …. The sanitary arrangements were poor and the odor of the place was foul. (Quoted in Waugh Reference Waugh1982, 30)

These tours quickly became an obligatory rite de passage for politicians and government officials. When the State of Illinois installed a committee of its own to investigate the sweatshop system, Kelley was invited as expert witness. Asked by the committee’s chairman for advice on how to investigate the “evil” of the sweatshops, Kelley invited the committee members for a walk through the ward around Hull House, thus re-enacting her visits for the Illinois Bureau of Labor Statistics (Stromquist Reference Stromquist2010, 46-48). Abram Bisno, also present, suggested they begin taking testimony “at once,” because the Jewish shops were about to close for the Shabbat.

The tour with the committee members was prepared in advance, but the facts already known to the committee members from Kelley’s report became real once they crossed the sweatshop’s doorsteps. The transcript of the joint committee (which consistently misspelled Kelley’s name as Kelly) reads:

The committee then started out, accompanied by the representatives of the press, and the first place visited was the sweat shop of K. A. Garbulsky, in the rear of a frame tenement house at No. 257 West Polk street. The place consisted of three rooms, one of which was used for a work-shop, the other for a kitchen, which opened into the work-shop, and the third room as a sort of store-room for coal, which also opened into the work-shop. The work-shop and kitchen were small rooms, about 12x7, the ventilation was bad, and the smell from decayed matter and dirty clothing, which were strewn around the rooms, was almost unbearable. In the kitchen was a door which opened into a water-closet, which was in a most unsanitary condition, and was used by the family and employés in common. There were seven in the family, including four small children, one of whom was in a dying condition with the measles, and three others of whom were just recovering.

The proprietor, Garbulsky, was examined by Senator Noonan as follows:

Q. What is your business? A. Manufacturing knee pants.

Q. How many employés do you have here? A. That is a question of how much l have to do; sometimes two, three, and five.

Q. How old is this girl working on this machine? A. Fourteen years old.

Q. What is her name? A. Lizzie Champ.

Q. How many hours a day do you work your employés?

A. About ten.

Lizzie Champ examined:

Q. How many hours a day do you work? A. I come here at 7 o’clock and go home at 6 o’clock.

Q. How much do you make a week when you work? A. Let him tell. (Referring to the proprietor).

Q. I want you to tell. A. Well, he gives me $1.50 a week.

Q. How long do you have for dinner? A. A half hour.

Q. Do you work Sundays? A. No.

Q. How old are you? A. Fourteen.

Garbulsky re-examined:

Q. How many children have you got? A. Seven in family altogether; I have four children.

Q. How many rooms do you occupy? A. Three.

Q. You say you don’t work on Sunday? A. No.

Q. Do you mean to-morrow by that? A. No, I work Saturday.

Q. And Sunday, the following day, do you work? A. No, sir.

Q. What is your nationality? A. Russian Jew.

Q. Are those girls Italians? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, this child here is sick? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Have you had a doctor for it? A. No, sir, the child has the measles.

Q. Who do you work for? A. For Rothchild & Co.

Q. What is the size of this room? A. 12 by 7.

One of the other employés, a boy apparently about 12 years old who was working on a machine was questioned as to his age, and stated he was 15. He said he made $3.00 a week, and worked from seven o’clock in the morning until six at night.

By Senator Noonan:

Q. Do you ever do any work after supper in the busy times?

A. No, I don’t work more than ten hours.Footnote 14

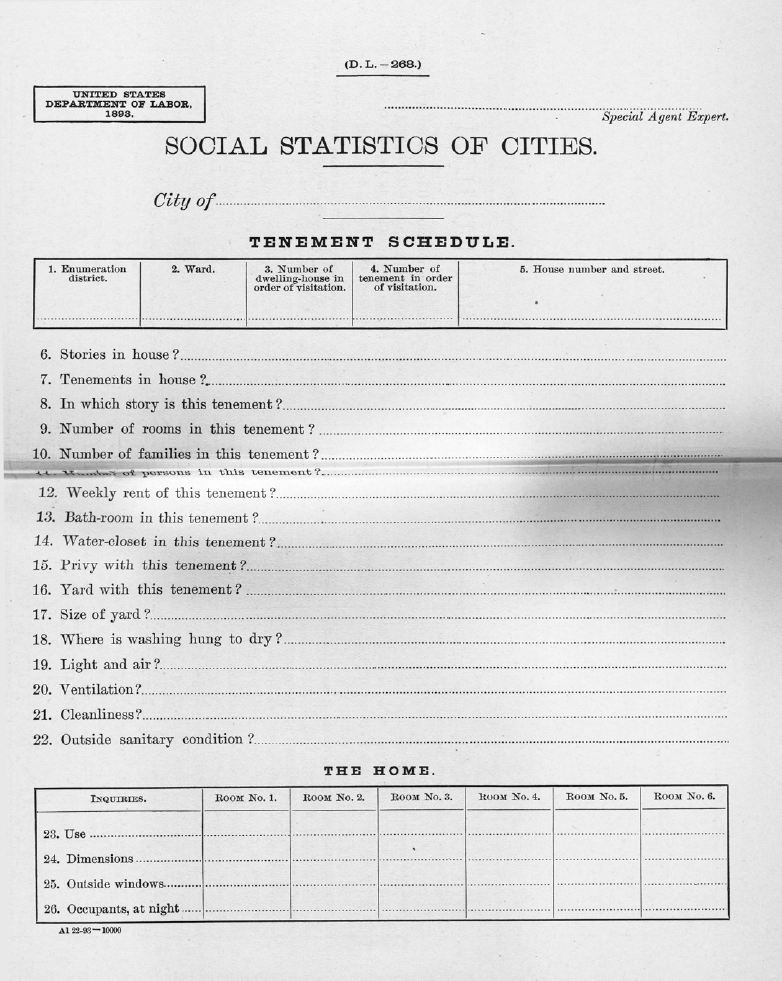

Kelley had collected her data with door-to-door visits to the tenements surrounding Hull House and diligently transformed them into the tables and cursory descriptions in her report. The descriptions in the press and tours with lawmakers through the sweatshop district turned these abstract tables and numbers back into public political experiences. It is one thing to see a table in a report, as in figure 3 that we took from Kelley’s report. It is another to sense and smell their meaning.

Figure 3. Fragment of table 1 of Kelley’s report (which runs over several pages) on the sweatshop system for the Illinois Bureau of Labor Statistics of 1892. The table shows the kind of garment made (here coats), the number of men, women, and children working, the size of the dwelling, and its sanitary conditions.

Source: Seventh Biennial Report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics of Illinois, 1892. 1893. Springfield, Ill.: State Printer, p. 419.

Thus, by re-enacting the steps for her survey, Florence Kelley mobilized political support for her draft legislation. Just as the spectacular maps of the Hull House Maps and Papers served as illustrations for a larger educated public of the dire living conditions of the immigrant urban poor, so did the visits of the joint committee and its coverage by the press convince lawmakers of the need to regulate labor working conditions. They transformed statistical evidence into the need for regulatory action.

Ellen Swallow Richards, experiment stations, and the iron law of wages

Let us now turn to the work of Ellen Swallow Richards and her reliance on laboratory experiments as the preferred method for social change. Ellen Swallow Richards opened the doors of the New England Kitchen on January 24, 1890. The Kitchen, located at 142 Pleasant Street, a “respectable part” of Boston, in a quarter with small shops and businesses, was designed for the sale of healthy, nutritious take-away food to its working population. These meals had been developed by Richards in her laboratory at MIT and were to be tested and perfected by confronting them with the tastes and appetites of the public that could buy these meals at low cost. Richards, who has been described as the single “most influential scientist you probably never heard of” (Robinson Reference Robinson2014, 15), was the first woman to be allowed advanced studies at MIT (without a degree). During the 1880s, she conducted laboratory research to improve sanitary conditions and nutrition of the working urban poor. At the turn of the century, she was a key founder of the Home Economics movement, which became an integral part of women’s academic and vocational training at Land Grant Colleges in the interwar period. Her combined field and laboratory work with MIT chemist Thomas Brown set the first standards for water quality in Massachusetts and led to the so-called Richards maps, which indicated the level of water pollution in different parts of Massachusetts. Working with food journalist Mary Hinman Abel, she gained the financial and scientific support to open the New England Kitchen from Willard Ogburn Atwater, professor of chemistry at Wellesley College and director of the national network of agricultural experiment stations, and from Edward Atkinson, a prolific Boston businessman and free trade publicist who served on the MIT board of trustees. This New England Kitchen was not intended as a community center, but as an experiment station that would give a “cosmopolitan” flavor to Richards’s laboratory meals and teach its clients the newest scientific knowledge about how to cook healthy, nutritious, and affordable meals.Footnote 15

Richards was born 1842 in Dunstable, Massachusetts, the only child of a shopkeeper’s family of modest means. She died in 1911 while deeply involved in the institutionalization of the Home Economics movement. Richards received her bachelor’s education at Vassar College, a women’s college established in 1861, just at the start of the Civil War. As noted above, much of her early research was in sanitary and food science, but her interest in what was to become home economics began at the Philadelphia World Fair of 1876. The exhibits of European countries like Sweden and Russia convinced Richards of the underdeveloped state and lack of knowledge in America—not only about food, but about all matters related to the management of the household. Richards thus became interested in Catharine Beecher’s system of teaching the American housewife how to clean the house (Beecher Reference Beecher1848).Footnote 16 In contrast with Beecher’s religiously inspired program of family visits (ibid., 179-180), however, Richards put faith in modern scientific insights gained by experiments to improve women’s habits. Instead of visiting the family home, she created public spaces in which to show and teach these insights, leaving it to the public to implement these findings in the private sphere. Richards’s program of home economics gained speed with the annual conferences she organized from 1899–1908 with Annie and Melvil Dewey at their resort in Lake Placid.Footnote 17 In the 1920s, educational programs in home economics covered the whole spectrum of household and consumption activities, but in the 1880s and 1890s, Richards’s main focus was on the improvement of the dietary habits of the American working population.

Richards’ concerns with the dietary habits of Americans fell squarely into contemporary debates about the standards of living of the urban poor, controversies about the unionization of the American work force, and the minimum wage (see e.g. Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985). For her dietary research, Richards joined forces with the Wesleyan professor of chemistry Wilbur Olin Atwater, the Boston laissez faire businessman and inventor Edward Atkinson, and food publicist Mary Hinman Abel. Atwater was a well-known chemist in nutrition research, who imported the caloric measurement system into the US (Finlay Reference Finlay1992; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1971). He studied at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, to which he returned as a professor after his chemistry degree from Yale in 1869 and his travels through Europe. Atwater participated in Carl von Voit’s laboratory work on nutrition in Munich and became an ardent promotor of the German system of agricultural experiment stations (Williams Reference Williams2019). He became the director of Connecticut’s agricultural experiment station and, after the Hatch Act passed Congress in 1887, of the Federal system of agricultural experiment stations (Finlay Reference Finlay1988).

Atkinson was a successful Boston businessman, inventor, and publicist on political economy. He was a Democrat and a vocal defender of free trade, in the Manchester tradition of the Cobden Club. He frequently intervened in public debates about the workers’ struggle for higher wages and unionization, both of which he considered a very bad idea, because of his political economic convictions and because he considered freedom of contract essential for the American concept of liberty.Footnote 18 He embraced the classical political economists’ theory of the wages fund, which implied that the “immutable laws of supply and demand” in the short run did not allow for wage increases, but disputed that this boiled down to the Lasalle’s “Iron Law of Wages,” because statistical evidence showed the substantial improvements of the standard of living of the American working class in the period following the Civil War. Instead of cultivating the class-antagonism between labor and capital, working class families would do better to scrutinize their spending behavior and especially, as he did not fail to repeat, should consider the tremendous gains they could make by saving on their most important category of expenses: food (Atkinson 1886; Reference Atkinson1887).

In his presentations to unionists, Atkinson backed up his arguments with diagrams that pictured the division of revenues between labor and capital. However inevitable the difficult contemporary working conditions might be—which he fully admitted—they would improve in the long run because of the many innovations that lowered cost-of-production (see Atkinson 1886; Reference Atkinson1887). Railways were his recurring example, and time and again he challenged his public by arguing that Vanderbilt’s wealth was dwarfed by the huge wage increases, in real terms, of American workers. Instead of organizing in Unions to increase their wages to the detriment of the incentives for businessmen like Vanderbilt to innovate, American workers should embrace the spirit of liberty of the American Constitution, as inscribed in the fourteenth amendment’s guarantee of an individual’s freedom of contract.

In a concerted effort to bring their arguments to a larger public, Atwater and Atkinson published a series of articles in the Century that linked Atwater’s research on the calorie to the savings that could be made by spending on a more nutritious and cheaper diet. In this series, Atkinson also explained the working of the energy efficient oven he had invented, the Aladdin oven, a slow-cooking oven that was particularly fit for the cooking of stews and broths (Atkinson Reference Atkinson1892; Levenstein Reference Levenstein1980; Williams Reference Williams2019). Atwater’s research and Atkinson’s liberal economic position provide the context for the dietary experiments of Richards and Abel, to which we now turn.

The New England Kitchen experiments

During the 1880s, Richards investigated optimal dietary composition in terms of carbohydrates, fat, and proteins, for which she relied on Atwater’s research. Atwater had developed norms for calorie-intake for men and women, and for different kinds of work. His research was based, in turn, on Voit’s research on the calorie, which he adjusted upwards because he considered American workers more productive than Germans, and therefore consuming more energy. Initially, Richards composed her meals without consideration of their taste but merely with regard to their nutritious value. Her next step was to improve the dietary habits of the American working population by testing these meals on their palates.

In 1890, Richards was on the jury of the Lomb Prize from the American Health Association, which awarded Mary Hinman Abel the first and second prize for her essay Practical Sanitary and Economic Cooking (Abel Reference Abel1890). During her travels with her husband John Abel, a professor of pharmacology at Johns Hopkins, Mary Abel had been impressed by the German and French public kitchens. Richards and Abel joined forces to develop a similar initiative but adjusted to the American situation and to the exigencies of Richards’s research agenda. This meant that their kitchen should not function as a community center, but as a take-away. They argued that Americans preferred to consume their meals with their families, and more generally take-away food was better adjusted to modern working conditions. Richards and Abel argued that “what we call the working classes” suffered from a “lack of planning” in the preparation of food which made that last-minute cooking mostly consisted of low quality-high price meals. For Richards, the suppression of the community function underlined that they were concerned with an “experiment to determine the successful conditions of preparing, by scientific methods, from the cheaper food materials, nutritious and palatable dishes, which should find a ready demand at paying prices” (Abel and Richards Reference Richards1893, 3, emphasis in original).

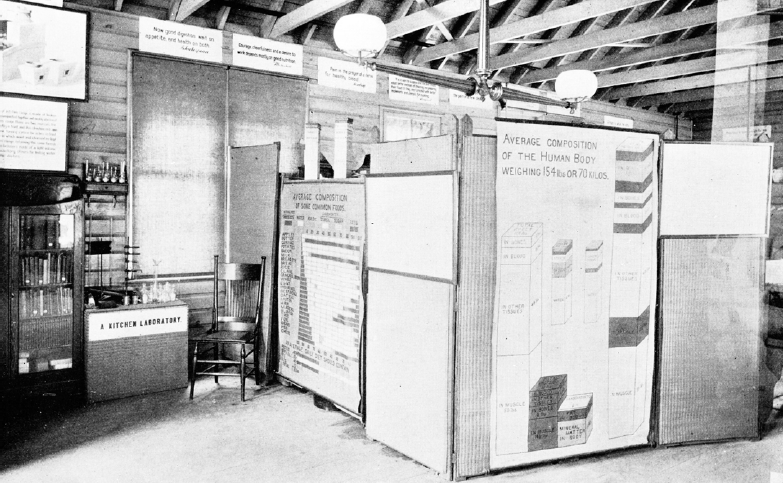

With financial support from Atkinson and his network, and a grant from the Elizabeth Thompson fund, Richards and Abel opened the New England Kitchen in Boston on January 24, 1890. The kitchen was equipped with three Aladdin ovens for slow cooking, and a gas pit for fast cooking. Richards had intended to name the kitchen the Rumford Kitchen, the name that was used for their model kitchen at the Columbia World Fair of 1893, because of the American scientific credentials of Count Rumford (on whom more below). It was an open kitchen with large windows that “flooded the space with sunlight and ventilation” (Williams Reference Williams2019, 441). There were a few tables, where customers could be seated while their meals were being prepared. This also gave them the opportunity to inspect the ingredients and utensils used (see figure 4).

Figure 4. “The New England Kitchen, Pleasant Street, Boston.”

Source: Mary Hinman Abel. “The Story of the New England Kitchen, Part II (The Rumford Kitchen Leaflets No. 17)—A Study in Social Economics.” In Ellen Richards. 1899. Plain Words About Food: The Rumford Kitchen Leaflets. Boston: The Home Science Publishing Company, between pp.132-133. Source: https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:2936825$149i

In his very interesting analysis of the New England Kitchen, Nicolas Williams argues that the dietary program of Richards and her collaborators turned the human body into a “site of social reform” by trying to change the food habits of the American population (Williams Reference Williams2019). It is precisely an example of what O’Connor considered a program of cultural change of the behavior of the poor. But Richards and Abel also conceived of the New England Kitchen itself as a site of social reform. Instead of entering the household to change its conditions, the New England Kitchen created an alternative space, which they “sometimes called a household experiment station” (Abel and Richards Reference Richards1893, 23). It sought to bring the latest scientific results to its clients by using them in experiments designed to determine the optimal composition of meals, not only in terms of nutritious value, but also in terms of taste and costs. This space belonged to “no school, no sect” and antagonized “neither class nor individuals” as it was designed as a site of improvement for all Americans (ibid., 16). It taught lessons about the “root of many evils” and sought to direct “public efforts and private household life” to “better methods of living” (ibid., 23). The New England Kitchen counter served as a “rallying point” that gave them access to “many classes of people” in ways not available to “the agent of the census or of the labor bureau” by opening conversations about food and kitchen utensils “far beyond our own experience” (ibid., 16).

Testing the meals on the public’s palate was a two-way process. On one hand, the meals had to be adjusted so that they fit the taste of the customers. On the other hand, the taste of the customers had to be adjusted to the optimal nutritious composition Richards had calculated in her laboratory at MIT. For example, Richards and Abel initially refused to add “dumplings” to their soup, “whose sodden name was enough to condemn it” and which “scientific authority” forbade them to include. But they soon realized that they were “bracing” themselves “against a very popular dish” and that they therefore had to invent an acceptable replacement (Abel Reference Abel1890, 10–11). In spring, “tomato soup was called for,” but the acidity of the dish posed a substantial problem because it demanded substantial research to make this soup sufficiently nutritious, in which they succeeded by adding meat broth and sugar (Abel Reference Abel1890, 10). These adjustments were negotiated at the kitchen counter of the New England Kitchen and fine-tuned in Richards’s laboratory at MIT, to which she returned to adjust and check the composition of meals against her optimal nutrition standards. On average, this adjustment process took them a month per dish. The final result should be a “cosmopolitan” dish, that is a dish that would suit the taste of as many different consumers as possible, without compromising on nutritious value.

The Rumford Kitchen at the Chicago World Fair

Initially, the New England Kitchen proved very successful. Abel and Richards soon opened two additional branches in districts of Boston with larger immigrant and African-American populations. In 1891 they began serving school luncheons at a Boston high school and women’s college, and in 1894 they were granted a contract to cook luncheons for all nine high schools in Boston. Atkinson’s lectures on the New England Kitchen inspired Columbia’s chemistry professor Thomas Egleston to promote the New England Kitchen in the Settlement movement, and Settlement houses in New York, Philadelphia, and at Hull House in Chicago all bought a New England Kitchen (on which more in the next section). But their largest exposure no doubt came from their presence at the Chicago World Fair, as part of the scientific submission of the State of Massachusetts. This gave them the opportunity to follow through on their “call to educate the public in general” (Abel and Richards Reference Richards1893, 17).

The Columbia World Fair, visited by a stunning twenty million visitors from a population of sixty million, turned the New England Kitchen from an experimental site into an experimental theater. Richards had already played with the name of Count Rumford to stress the historical links of the New England Kitchen with American science, and Rumford seemed an excellent choice for this purpose.Footnote 19 Count Rumford, born in 1753 as Benjamin Thompson some fifteen miles from Benjamin Franklin’s place of birth, was a colorful Anglo-American scientist and inventor whom historians of science remember for his experiments on heat. He invented a chimney opening with a restricted and more efficient updraft, creating a smoke-free and more energy efficient kitchen. During his extensive travels, he became an advisor to the prince of Bavaria, where he started a food kitchen for the poor. The prince was so impressed with his work that he awarded Thompson with the title of count. He was sent to Britain to take up the post of ambassador of Bavaria, but this proved impossible because of his English descent. He stayed, however, in Britain, and set up the Royal Institution of England in 1799 with the help of Joseph Banks, and with Humphrey Davy as its first lecturer. He married Lavoisier’s widow in 1804 in an unhappy marriage and died in Paris in 1814.

The association with this colorful American scientist and inventor, whose work had served the public good, clearly served to emphasize that food and nutrition were not just a women’s business, but a matter of national interest. This was also the reason that Richards had lobbied successfully to have the Kitchen included as scientific exhibit of the Bureau of Hygiene and Sanitation of Massachusetts and not as part of the Women’s exhibits, which also showed a model kitchen. When he opened the Rumford Kitchen at the Columbia Fair, economist and MIT president Francis Amasa Walker emphasized its scientific status. The Rumford Kitchen, he argued, applied “the principles of chemistry to the science of cooking” (Walker, In Richards Reference Richards1899a, 11). It was financially supported “with pecuniary assistance from certain public-spirited citizens of Boston,” but it was not a “money-making exhibit” (ibid.). The Rumford Kitchen was to be regarded as “as absolutely a scientific and educational one” (ibid.). But it was also an effort to standardize American tastes, based on the best findings of American science.

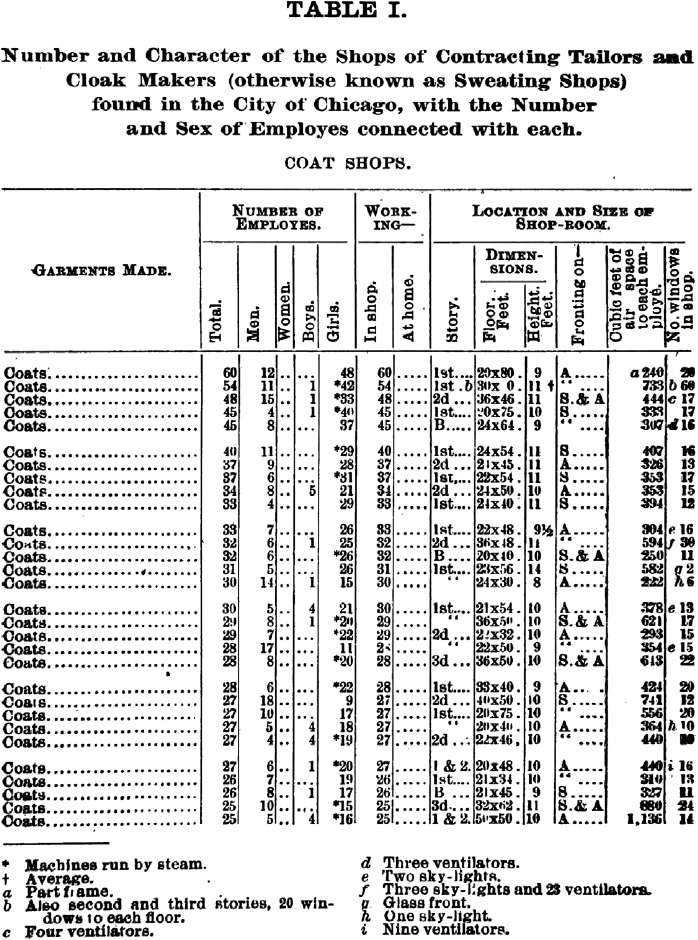

The exhibition building, which looked like an American homestead (see figure 5), was divided into two separate rooms. One room was dedicated to the work of Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford. Its walls were decorated with his many wisecracks on food, and it included a library of his publications, which was open to the public. In the main room were seating tables and a New England Kitchen. The Kitchen served ten representative dishes to its visitors to give them a taste of what a healthy American way of life should look like. Over the months, some 10,000 meals were sold.Footnote 20

Figure 5. Photograph of the Rumford Kitchen building at the Chicago Fair.

Source: Ellen Richards. 1899. Plain Words About Food. Boston: Rockwell and Churchill Press, pp. 10–11. Source: https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:2936825$18i

The main room contained billboards and posters with the latest scientific findings on food and nutrition, which were also included in a series of pamphlets, the Rumford Kitchen Leaflets, which could be taken home (see figure 6). They contained historical information on Count Rumford and his scientific work on heat and nutrition, on the history of the New England Kitchen, on its scientific basis, its results, and its future.Footnote 21 There were also hand-outs that compared the nutritious values and costs of the dishes against the food standards of Voit and Atwater for a man’s day’s ration of calories.

Figure 6. Interior of the Rumford Kitchen, which was equipped as a New England Kitchen. The large poster on the cupboard in front shows the average composition of a 70 kg human body. The label on the sink was designed to strengthen the link between scientifically informed cooking and the laboratory. In Ellen Richards. 1899. Plain Words About Food. Boston: Rockwell and Churchill Press, pp. 18–19.

Source: https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:2936825$30i

In her history of the New England Kitchen, published as Rumford Kitchen Leaflet 17, Mary Hinman Abel explained its meaning for the American workman. As Americans increasingly moved away from their traditional New England slow cooking dishes by replacing them with quick and expensive low-nutrition food, American workmen came to nourish themselves at the expense of other vital needs:

The wage earner is illy [sic] nourished on money that is all-sufficient, if rightly expended, to buy him proper food. This is a serious question, because here there is the chance of more saving than in any other item of living; and what can so easily be saved here can be applied to better shelter, which is a more evident, if not more vital, need. (Abel, In Richards Reference Richards1899a, 150)

Abel evoked statistical evidence “carefully compiled” by the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics on the lower costs of food in America compared with Europe, and observed that this difference had not led immigrant Americans to lower their food expenses (ibid., 151). She cited a German workman for whom “American freedom and prosperity” had the “very limited meaning” of “meat on the table three times a day” (ibid.). But the meals Abel and Richards had developed with their experiments at the New England Kitchen showed that “a Lowell factory operative” who spent $200 “out of his $360 total income” on food, “could have secured better nutrition for $100, and have $100 to put into better shelter and a dress for his wife, who had had none since her marriage seven years before” (ibid.). Thus, the information and meals presented and served at the Rumford Kitchen not only aimed to inform the audience of the recent findings of science, but also tried to convince them, as Richards wrote in Euthenics, to accept and apply “the knowledge that investigators are gaining in the laboratory” to change their spending habits (Richards Reference Richards1910, 15).

“If a man eats not, he shall not work”

Richards’ focus on the export of laboratory research to the domestic sphere did not exclude the use of social surveys. Indeed, in the early 1890s Kelley and Richards’ reform programs briefly met when Richards supervised a survey on the dietary habits of “wage-earners and their families” in Philadelphia and Chicago (Richards Reference Richards1893). The opening phrase of Richards’s report, published by the State Board of Health of New Jersey, inverted the biblical relation between work and food, by putting food first and work second. “If a man eats not, he shall not work” emphasized that the health of the American work force was primarily seated in its dietary habits. When these habits could be improved, the health of the nation would improve as well. Just as had been the case with her research into the water quality of Massachusetts, Richards combined laboratory and field work to measure her laboratory norms against the actual state of affairs (ibid.).

For Chicago, the survey was conducted in Spring 1892, with Hull House as its base and with the help of Hull House resident Caroline Hunt, Richards’s later biographer (Southard et al. Reference Southard, Richards, Usher, Terrill and Shapleigh1903). In Philadelphia, her co-author Amelia Shapleigh (a resident of Philadelphia’s settlement house), conducted the survey. Robert Dirks notes that working-class families were warned not to participate in such surveys because “rumors circulated that investigators wanted to see how cheaply people could eat so that employers could cut wages accordingly” (Dirks Reference Dirks2016, 12). But the familiarity of both surveyors with the neighborhood helped to secure their residents’ collaboration. In her report, Richards noted that she experienced no difficulty in securing the cooperation of families with this study, as “the work of Hull House was well known to them and appreciated” (Southard et al. Reference Southard, Richards, Usher, Terrill and Shapleigh1903, 68).

Kelley’s survey, following the method of the census, had aimed at completeness. In contrast, Richards randomly selected a limited number of households, which can be seen as a precursor of random sampling, which she then checked for their typicality of different immigrant groups—including, in the case of Philadelphia, its African-American population.Footnote 22 According to Richards, this procedure did not make the data collected less trustworthy. Other problems did, such as the tendency of women to overstate their food expenses when interviewed, or, when self-reporting, to note food expenses inaccurately. Overall, Richards considered the survey nevertheless of substantial worth, because it provided at least some empirical evidence on the diets actually consumed by the different indigenous and immigrant communities in urban centers of the United States.

Somewhat to her surprise, Richards found that the survey showed that families had better food habits than she had expected, but this did not mean further improvement was impossible. Richards saw that an increase of income led to an increase in food-consumption, whereas her laboratory results, and the meals she had composed in the New England Kitchen, had shown that a higher nutritious value could be reached with fewer expenses, for example with cheaper cuts of meat or cheaper, more nutritious vegetables. As a result, there were immigrant families who, just like the German immigrant quoted by Abel, now had meat on the table three times a day, instead of diversifying their expenses to other necessities of life.

The difficulties of changing dietary habits became manifest at the New England Kitchen Hull House had bought for its public restaurant and cafeteria in Spring 1893. In her personal recollections, Jane Addams remembered how Hull House had tried to use the kitchen to change food habits in the neighborhood, which “so sadly needed better feeding” (Addams Reference Addams1906, 12). Families suffered from exactly the kind of problems signaled by Richards and Abel in their History of the New England Kitchen. Children were asked to buy something just before the closing time of shops because their mothers had not found the time for shopping or to prepare a decent meal. But instead of shortening the working day, as Kelley proposed, Richards proposed adjusting dietary habits to market conditions. Addams followed Richards in her judgement that the improvement of food habits “could be best accomplished in public kitchens where the advantage of scientific training and careful supervision could be secured” (ibid.). Thus, Ellen Richards’ former student Julia Lathrop, who had recently moved to Hull House, was trained in the use of the New England Kitchen. Edward Atkinson himself inspected the Aladdin oven used at Hull House.

It soon became evident that it was easier to reverse a biblical phrase than to change food habits. Hull House’s cafeteria managed to sell some of its “carefully-prepared soups and stews in the neighboring factories,” but realized that it was unable to change the “wide diversity in nationality and inherited tastes” (ibid.). In contrast, Addams noted, the public kitchen’s function as a community center, which had been suppressed by Richards and Abel, was a success, as the Hull House cafeteria was one of the few places in the neighborhood were social gatherings and meetings could be held. Addams recounted how the “neighborhood’s estimate” of the food cooked in the New England Kitchen was “best summed up by the woman who frankly confessed that the food was certainly nutritious, but that she didn’t like to eat what was nutritious, that she liked to eat ‘what she’d ruther [sic]’” (ibid.).

Richards’ biographer Caroline Hunt considered that this pronouncement, which can also be found in Richards’ Rumford Kitchen Leaflets, sounded the “death knell” of the New England Kitchen (Hunt Reference Hunt1912, 220). Richards became increasingly impatient with women of different immigrant groups who were unwilling to follow the precepts of science, either out of prejudice or because they lacked the time and knowledge to take care of the family home. According to Levenstein, the failure of the New England Kitchen to change the food habits of the poor made her shift gears to a program that was directed at the education of middle-class women, a program which she developed with the Home Economics Movement and its institutionalization at Land Grant Colleges in the Progressive Period (Levenstein Reference Levenstein1980, 382-383). One can see this shift in the many brochures Richards wrote at the turn of the century about the costs of food and the cost of living, which no longer addressed the lower incomes but were directed at the wise spending of the middle-class (see Richards Reference Richards1899b; Reference Richards1901; Reference Richards1905).

Strategies of social reform

Like many other social scientists and reformers of the late Gilded Age and Progressive Era, Florence Kelley and Ellen Richards were concerned about the improvement of the living conditions of the urban working poor, but they followed different strategies to enact a change. Starting from O’Connor’s distinction between structural and cultural reform programs, we have seen how Kelley immersed herself in a social survey on the working conditions of the poorest population in Chicago, while Richards concentrated on the optimization of its dietary habits. Canvassing tenement dwellings door-to-door, Kelley charted the living conditions of the poor and turned her statistical and local knowledge into a weapon for social reform. Kelley’s socialist convictions made her situate the problem in the opposition between labor and capital, but she did not seek for a solution in revolutionary reform, but in legal change. Her object of study was the urban poor, but her audience consisted of local elites and lawmakers who had to be convinced of the need for action. Her social surveys provided the evidence that would induce legal change.

Kelley’s strategy was not limited to socialists but can also be found in the Men and Religion Forward Movement, the survey movement initiated and supported by Paul U. Kellogg, editor of The Survey and director of the famous Pittsburgh Survey, and in the work of Wisconsin institutionalists. Critics have denounced the early survey movement for its lack of technical statistical refinement and lack of theoretical grounding (Greenwald and Anderson Reference Greenwald and Anderson1996; Bulmer Reference Bulmer, David and Maris2001; Bateman Reference Bateman2001). But as Mary Furner pointed out, such criticism takes the first Chicago school of sociology of Parks and Burgess as its frame of reference, and fails to see that these early surveys fit in much better with the social scientific model of Wisconsin institutionalists like Richard T. Ely and John R. Commons (Furner Reference Furner2000).Footnote 23 For them, social knowledge consisted in knowledge useful for legal reform. Marianne Johnson recently exemplified how one of the strongholds of the Wisconsin model, the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, a forerunner of the Congressional Research Service, helped draft legislation in a “partnership between the bureau’s chief, Charles McCarthy, Commons, and the Progressive Governor, Robert LaFollette,” producing such laws as Wisconsin’s Civil Service Law (1906) and the Public Utilities Act (1907) (Johnson Reference Johnson2019, 275).

Florence Kelley fits into this model. Her social survey showed the scope of the social evils of a specific mode of production which was in need of legal regulation. But her case also makes clear that such knowledge was most effective when it was “grounded” knowledge, rooted in a local community with which the researcher was well acquainted. Her social survey, re-enacted by lawmakers and the press, provided the evidence that moved her target audience to action. This enabled Kelley to convince lawmakers that the regulatory state, not free markets, was needed for social improvement. But Kelley’s success depended substantially on the support and trust of the local population around Hull House as allies in her crusade for social change.

Chemist and propagator of the Home Economics Movement Ellen Richards situated the problem, and hence its solution, not in exploitative working conditions, but in the inefficient and wasteful usage of available resources by the working poor. As Richards wrote in Euthenics, the Science of Controllable Environment, “no state can thrive while its citizens waste their resources of health, bodily energy, time, and brain power, any more than a nation may prosper which wastes its natural resources” (Richards Reference Richards1910, 84). Laboratory work would enable the development of optimal standards, and educational programs should bring these standards to the public my means of models and exhibits. As she wrote programmatically, “the Force of example, the power of suggestion should be used fully before coercion is applied. Exhibits and Models come before law” (ibid., 118).

With this aim, she constructed public spaces that she ran as laboratories for food and sanitary experiments. Richards thus flipped the household inside out. Instead of the researcher entering the home, women should be taken out to learn by experiment and instruction in hybrid laboratory spaces such as the Rumford Kitchen. While Florence Kelley aimed to change the living and working conditions by entering the household with questionnaires, Richards aimed to change the behavior of the manager of the household—the housewife. Seeing the example, she argued, should incite the public to modify their behavior into a homogenized American mold. The New England Kitchen, and later the Rumford Kitchen at the Columbia World Fair, were examples of such public theatres of experiment. Such model homes and model kitchens, some of them mobile, became stock-in-trade at world fairs, and extremely popular from the 1920s onwards with the work of Christine Frederick and Lillian Gilbreth. The Mary Lowell Stone Home Economics Exhibit, for example, toured from Boston, via Baltimore, Philadelphia, Trenton, New York and Chicago, to the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in St. Louis in 1904, and aimed to show the meaning of home economics in relation to shelter, food, and clothing (Weigley Reference Weigley1974, 94). As Antoinette LaFarge explains, there was an “innate theatricality” to these model homes, “an intersection of private space and public spectacle” which performed Anglo-Saxon versions of domesticity “in the spotlight” (LaFarge Reference LaFarge2019, 62).Footnote 24

Richards considered that the great challenge of her program was to “make efficient, self-sustaining citizens who do not feel the pull of the law or the bond of outside care” (Richards Reference Richards1910, 67). Solving the “conflict between the ideals of individualism and those of the community need, subordinating the individual preference” was the way forward (ibid.). This could only be attained when social reformers relied on the findings of science as a lever for social progress. “Knowledge” that was gained by researchers in their laboratories should be taught to the public and “accepted and applied by the individual” (ibid., 15).

Richards’ reform strategy thus entailed a completely different attitude toward the public. The public was not perceived as an ally in a crusade for social change, but as a collection of experimental subjects who needed to follow the science and change their suboptimal nutrition and sanitation habits. When it became apparent that experimental subjects prefer their own way of life, Richards voiced her exasperation about women who were unwilling to follow a “scientific understanding” of the household’s organization and asked them to no longer “stand in the way as [they are] surely doing today” (Richards Reference Richards1899a, 118).

In an address to the American Public Health Association in Richmond, published as chapter X of her Euthenics, the Science of Controllable Environment (1910), Richards wrote that “nearly every investigation of sanitary evils leads back to the family home (or the lack of one) and a great deal of the health authorities’ work is saving at the spigot while there is a hundred times the waste at the bunghole” (Richards Reference Richards1910, 165). She continued that it was finally “beginning to be thrown in the faces of sanitary authorities that the Laboratory wisdom does not reach the street; that there is not enough, or rapid enough, improvement in general conditions” (ibid. 169). She concluded that sanitary authorities should see to it that their inspection efforts of the family homes were “not wasted on an inert, partially hostile clientele” (ibid., 175). But with her emphasis on the hierarchical transfer of knowledge from the laboratory to the public, Richards forgot one of the important lessons learned from the New England Kitchen; behavioral change is never just a matter of control, but also of voluntary collaboration. When Abel and Richards added an Indian pudding to their standard dishes, an Irish boy exclaimed: “Oh! You can’t make a Yankee of me that way!” (Richards Reference Richards1899a, 139). Changing the food preferences of a diverse immigrant population to fit a homogenized American mold was never just a technical, but always a deeply cultural affair.

Gabrielle Soudan is a doctoral student at the Institute of Political Studies of the University of Lausanne and a member of the Walras Pareto Center for Interdisciplinary Studies of Economic and Political Thought. In the framework of the SNSF project Moral Accounting Matters led by Professor Harro Maas, she is working on her doctoral dissertation on the moral and patriotic management of American housewives’ household accounts in the Progressive Era (1890-1942).

David Philippy is a historian of economics and currently a postdoc fellow researcher at CY Cergy Paris University (AGORA center). He holds a PhD in economics from the University of Lausanne (“The World Behind the Demand Curve: A History of the Economics of Consumption in the US, 1885-1934”). His current research focuses on the history the economics of consumption in the early Twentieth-century US, with an emphasis on the crucial role played by the American home economics movement and female institutionalist economists such as Hazel Kyrk. His article “Ellen Richards’s Home Economics Movement and the Birth of the Economics of Consumption” has been published in 2021 in the Journal of the History of Economic Thought (https://doi.org/10.1017/S1053837220000115).

Harro Maas is a professor in History and Philosophy of Economics at the Walras-Pareto Center for the History of Economic and Political Thought at the University of Lausanne. He has published widely on the history of economics from the Victorian period to the present, with an emphasis on the transformation of the economist’s methods of thinking and acting with ‘data’. As principal investigator of the SNSF project “Moral Accounting Matters: A history of behavioral governance, 1800-1940,” he is currently interested in how ordinary accounting tools, such as daily planners, have co-produced and rationalized consumer behavior.