SARS-CoV-2 and the associated disease COVID-19 have radically changed the world since their first appearance in December 2019. Their impact has been felt across the globe and even within the academy. They have caused reflection on the roles of governments and markets in effectively allocating those goods most essential to fighting the spread of the virus and saving lives. One element of this relates to pricing. In times such as these, it is possible for individuals and firms to exploit fear, as well as genuine need, to gain huge profits by selling essential goods at prices that would have been inconceivable before the onset of the global pandemic. Hereinafter we refer to such price increases during a disaster as “price gouging.”Footnote 1

To take one example, Matt Colvin gained notoriety early on during the crisis in the United States because he purchased seventeen thousand bottles of hand sanitizer with the intention of reselling them online at a considerable upcharge (Nicas Reference Nicas2020). He received scorn and even death threats. He sold only three hundred bottles before online resellers like Amazon and eBay, in response to public pressure, began to restrict some sellers who were charging “unfair” prices (Ebay News Team 2020; Huseman Reference Huseman2020; Nicas Reference Nicas2020). The Tennessee attorney general’s office even opened an investigation into Colvin and his actions (Nicas Reference Nicas2020). In the aftermath of such activities across the United States, various state governments have created websites that allow citizens to report incidences of putative price gouging to the authorities.Footnote 2 To take another kind of example, sometimes whole industries can undergo putative price gouging. During April 2020, prices in the United States for personal protective equipment rose on average by 1,000 percent, gowns by 2,000 percent, and N95 masks by 6,000 percent (Diaz, Sands, and Alesci Reference Diaz, Sands and Alesci2020). This prompted prominent businessperson Mark Cuban to accuse key manufacturer 3M of enabling its distributors to price gouge (Cachero Reference Cachero2020). In September 2020, the US Public Interest Group Federation raised a concern about what it referred to as continued price gouging on Amazon in particular, calling on Amazon to “police themselves” and for “every state” to “pass anti–price gouging laws” (US Public Interest Research Groups 2020).

Although, intuitively, it may seem unconscionable to profit during a global pandemic that is shaking society to its core and in which hundreds of thousands are dying, there is considerable philosophical debate over the permissibility of price gouging in general. Some contend that the positive benefits that can arise from price gouging can justify permitting such behavior. For example, a petition to repeal state laws in the United States outlawing price gouging during the pandemic has been signed not only by numerous economists but also by prominent philosophical defenders of price gouging, such as Jason Brennan and Matt Zwolinski (Niles Reference Niles2020). Of course, this position is not universally held. Since the onset of the pandemic, philosophers at Harvard’s Safra Center for Ethics have noted that “scarcity creates motives for hoarding and profiteering … [and] this needs to be monitored and prevented ” (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Stanczyk, Cohen, Shachar, Sethi, Weyl, Brooks and Edmond2020, 29, italics added). These concerns reflect a vibrant debate in which many philosophers contend that government regulators ought to step in to restrict price gouging in times of emergency. It is not our intention here to settle this debate. Rather, we intend to further this debate by developing and updating existing accounts to incorporate the challenges posed by the coronavirus pandemic and subsequent global crises.

Crucially, we do not intend to provide definitive policy advice for regulators during the coronavirus pandemic. Part of our point is that the complexity of this particular crisis requires further empirical study. Instead, we present a conceptual analysis of crisis price gouging that develops policy-relevant distinctions. These distinctions can inform policy making that is sensitive to the particularities of market structure. Our analysis can enable policy makers to better differentiate permissible from impermissible price gouging and thereby bring about better regulations regarding price increases in what remains of the current crisis, and in future crises.

Given this relatively modest goal, we begin by presenting a curated review of the philosophical literature on price gouging. Within the relevant literature, we identify two potential justifications for regulators permitting price gouging: 1) informational efficiency and 2) allocative efficiency. We also identify one potential justification for regulators restricting price gouging: equity concerns. How to balance these competing justifications is a persistent challenge identified in the philosophical literature on price gouging. We will not attempt to settle it here. Rather, we will identify factors that can occur in particular emergencies that may weigh in favor of a permissivist or restrictivist approach to price gouging. However, we also show that the existing accounts we survey have not been suitably calibrated to the particularities of the global coronavirus pandemic.

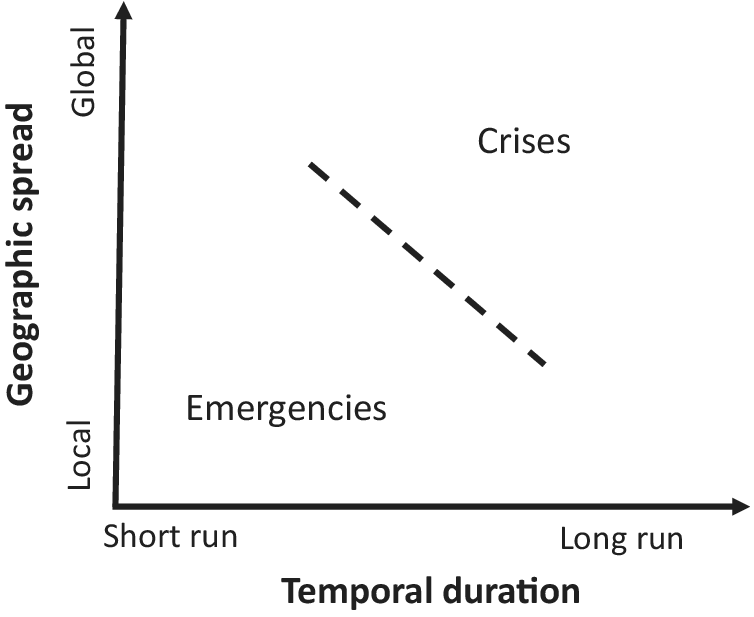

Moving beyond the existing literature, we distinguish between emergencies and crises. A paradigm emergency is a localized event, the initial shock of which ends relatively quickly. Classic examples include hurricanes and floods. They strike particular regions quickly, leaving devastation in their wake. However, beyond the scope of the emergency, other regions remain relatively unscathed and thus able to intervene to help those affected most by the emergency. The coronavirus pandemic is different. It has affected everywhere nearly simultaneously and has persisted for a full calendar year. This is a crisis. It is important to note that the differences between emergencies and crises operate along a continuum. While a typical emergency will be highly localized and dissipate quickly and a typical crisis will be global and persist for a long period of time, many if not most events will fall somewhere in between these two poles. That being said, as we will demonstrate, the distinction will prove a useful analytic resource when evaluating price gouging regulation, despite the fact that the distinction does admit some degree of vagueness.

Despite the inherent vagueness of this distinction, philosophical analysis of price gouging ought to incorporate the particular challenges raised by crises that do not arise in the traditional emergencies existing accounts address. Specifically, we argue that crises highlight an underanalyzed justification for permitting price gouging: production incentives. On the other hand, the concerns about equity that price gouging raises can be intensified in crises, especially if production cannot be increased or where the underlying inequities are spread across several polities. We conclude by considering the practical implications of our analysis and discuss concrete steps by which regulators can maximize the beneficial consequences of price gouging while minimizing its most deleterious effects.

JUST PRICES AND EXPLOITATION

There is an intuitive sense in which objectionable price gouging is merely a species of exploitation or unjust pricing. After all, what might be morally objectionable about price gouging is that sellers are exploiting individuals who are made desperate by a disaster, and they do so by charging an unjust price. Given this intuition, one way to start to think about the price gouging debate would be first to identify what makes a price fair under less unusual circumstances and only then to consider the particularities associated with disasters. We sketch here the rich philosophical literature on exploitation and just prices. Ultimately, we conclude that this literature is not an appropriate foundation for analyzing the regulation of price gouging.

Philosophers debate whether a just price is one set in an “open market” characterized only by a large number and variety of buyers (Elegido Reference Elegido2015), a “hypothetical market” characterized by idealized informational symmetry and competition but retaining other inequalities (Wertheimer Reference Wertheimer1999), or one brought about by sellers refraining from extracting more than excessive profits from those who cannot reasonably refuse an offer (Valdman Reference Valdman2009). More radical approaches see any price set by consensual, nonfraudulent bargaining as just (Michel Reference Michel1999) or take the price that the just person would offer as the standard of justice (Koehn and Wilbratte Reference Koehn and Wilbratte2012). Still others suggest there is no good theory of what makes a price just or unjust, only intuitions about particular cases (Arneson Reference Arneson2016).

A related way to think about objectionable price gouging is to consider it as a case of wrongful but mutually beneficial consensual exploitation. This controversial kind of exploitation is typically understood as one party taking wrongful advantage of another’s weakness, whether cashed out in terms of appropriate respect (Sample Reference Sample2003), nondomination (Vrousalis Reference Vrousalis2013), or the unfairness of the transaction (Wertheimer Reference Wertheimer1999).

However, as Alan Wertheimer (Reference Wertheimer1999) and Ruth Sample (Reference Sample2003, 86–87) have pointed out, discussions of exploitation should be especially sensitive to the purpose of the normative analysis.Footnote 3 On one hand is the question of what Wertheimer (Reference Wertheimer1999) calls the “moral weight” of exploitation, the investigation of the moral status of putatively exploitative exchanges between individuals. On other hand is the question of what Wertheimer calls the “moral force” of unjust exploitation: should consensual, mutually beneficial, yet unfair exchanges be permitted by the state and society, or prevented? Defending the separation of the moral force and moral weight of exploitation, Wertheimer makes a familiar “right to do wrong” argument, concluding that morally justified laws might permit morally unjust exchanges, just as they permit many kinds of morally bad actions. “We should be courteous, civil, sensitive, brave and generous, but we do not think that the state should necessarily punish rudeness, incivility, insensitivity, cowardice and stinginess” (280). The same holds for lessons from the just price literature. Knowing that a price is inherently unfair does not tell us whether governments should prevent goods being traded at that price. The converse applies as well. More gouging-friendly theories of just price, such as that of that of Christian Michel (Reference Michel1999) or Juan Elegido (Reference Elegido2015), seem to excuse many cases of price gouging in terms of moral weight but they still leave the question of justified interference in price gouged transactions up for debate.Footnote 4 As morally justified laws can permit some unjust acts, they can also prohibit some acts that are not inherently unjust but must be regulated nonetheless, such as laws about what side of the road to drive on.

Another way in which one might think the just price literature should inform price gouging regulations is in a definitional role. A theory of just prices could set a permissible level of increase, above which would count as impermissible price gouging, if gouging were to be prohibited. But if the preceding argument for the separability of the moral weight of price gouging and its moral force is correct, ascertaining the theoretical just price from first principles will not lead to clarity on the appropriate level of permissible price increases in practice either. This is because the state might have other legitimate reasons for setting a different price threshold, some of which we discuss in this article.

For these reasons, we set to one side the theoretical literature of just prices and exploitation, which typically has focused on the moral weight of exploitation or unjust prices.Footnote 5 Where the literature has focused on the moral force of potential unjust or exploitative prices, these explorations are typically highly general or different enough from disaster price gouging to provide little guidance to the current question.Footnote 6 Instead, let us turn to the philosophical discussion of price gouging in particular, which typically focuses on the moral force of price gouging and thus bears a much closer relation to the regulatory questions in which we are most interested.

PRICE GOUGING: PERMISSIVISM AND RESTRICTIVISM

Standard philosophical accounts of price gouging often begin with a particular type of behavior in mind. In fact, one particular case has become a touchstone in the literature (Brennan and Jaworski Reference Brennan and Jaworski2015; Munger Reference Munger2007, Reference Munger2011; Zwolinski Reference Zwolinski2008). To explicate existing accounts and differentiate ours, here is a condensed version of the case.

The Icemen

On September 5, 1996, Hurricane Fran hit Raleigh, North Carolina, devastating local infrastructure.Footnote 7 More than a million people in the immediate area lacked electricity the morning after the storm, while homes and roads were damaged by falling trees. In the chaos, food scarcity became an issue for thousands of people. Refrigerators and freezers went without power, and food began to spoil in the humid and hot North Carolinian weather. Without cooling, fresh food, expressed human milk, and insulin would also soon go off, leaving those who relied on those essential goods in a very precarious place.Footnote 8 The result was simple: millions of people needed ice. The demand for ice soared, but the supply of ice in the Raleigh region could not grow to match the surging demand. The price for ice increased.

In the wake of the storm, four young men in Goldsboro, North Carolina (a town an hour east of Raleigh largely unaffected by the storm), decided to buy ice locally and sell it in Raleigh. Given the huge unmet demand for ice in Raleigh, the men could expect to charge considerably more for the ice than they had paid for it. The young men rented two freezer trucks and paid $1.70 per bag. With one thousand bags of ice, the young men set out toward Raleigh. Upon arriving, they sold the ice, and although it is difficult to pin down precisely how much each bag of ice went for, it was for more than $8 per bag. Raleigh residents were reportedly angry at the substantial price increase, but they still paid it.

Prior to the storm, North Carolina had an “antigouging” statute on the books. General Statute 75-38 stated,

It shall be a violation of G.S. 75-1.1 for any person to sell or rent or offer to sell or rent at retail during a state of disaster, in the area for which the state of disaster has been declared, any merchandise or services which are consumed or used as a direct result of an emergency or which are consumed or used to preserve, protect, or sustain life, health, safety, or comfort of persons or their property with the knowledge and intent to charge a price that is unreasonably excessive under the circumstances.

In practice, “unreasonably excessive” has typically been interpreted to mean price increases of no more than 5 percent during a declared state of emergency (Munger Reference Munger2007). Under this regulation, the police in Raleigh confiscated the ice and fined the men.

Permissivism and Efficiency

Permissivist accounts hold that price gouging, like that of the Icemen, can lead to beneficial consequences and is to be permitted given that certain conditions are fulfilled.Footnote 9 The argument draws heavily from economic theory. While a seller raising prices on essential goods during times of emergency might seem unfair to the buyer, it plays an important role in the larger allocative system organized around market transactions. Rising prices are integral to informational efficiency, which in turn incentivizes several kinds of behaviors, all of which tend to increase allocative efficiency. Allocative efficiency in turn leads to better consequences in nonideal circumstances.

In the price gouging literature, allocative efficiency is generally taken to refer to Pareto efficiency: a formal concept from economic theory. A Pareto efficient allocation of goods is one in which there are no unexploited Pareto improvements. A Pareto improvement is an exchange in which one party is made better off without making any other party worse off. Therefore a Pareto efficient allocation is one in which no party can be made better off without making another party worse off. Consequently, situations that are higher in allocative efficiency have fewer unexploited Pareto improvements. Following the precedent set in the philosophical price gouging literature, and policy discussions more generally, we have chosen to similarly identify allocative efficiency with Pareto efficiency, but it is worth noting that doing so has certain important philosophical implications. Foremost, Pareto efficiency is conceptually separable from equity. An allocation in which one individual possesses all goods and all other individuals possess nothing is technically Pareto efficient, though clearly severely inequitable. We explore the ways in which Pareto efficiency comes apart from equity concerns later in this section.Footnote 10

Let us now consider these different types of Pareto improving behaviors in turn. First, price gouging incentivizes consumers to economize on scarce products by either limiting their consumption to the bare minimum or seeking nonperfect substitutes. This leaves more of the essential goods for those with the greatest need (Zwolinski Reference Zwolinski2008; Brennan and Jaworski Reference Brennan and Jaworski2015). Second, price gouging incentivizes new vendors to enter the affected market, thereby increasing the total quantity of available essential goods at the emergency site (Brennan and Jaworski Reference Brennan and Jaworski2015; Munger Reference Munger2011; Zwolinski Reference Zwolinski2008). Third, price gouging incentivizes existing vendors to remain in affected markets that have become increasingly risky due to the onset of an emergency. This, too, serves to maintain and often increase the total quantity of essential goods available in these areas (Zwolinski Reference Zwolinski2008). The result of all of these behaviors is to increase the allocative efficiency in emergency regions. This is because the emergency has induced a drastic increase in the demand for essential goods while simultaneously disrupting supply chains, thereby decreasing supply. When demand outstrips supply, there are shortages, and these often lead to price increases. However, as the quantity supplied increases, shortages decrease, and prices often move toward their preemergency level.

Let us consider this in light of the Goldsboro Icemen. Permissivists often point out that by selling ice at such high prices, buyers were encouraged to buy ice only if they truly needed it. Probably only certain uses for ice were deemed necessary. Plausible candidates for such necessary uses of ice likely included preserving insulin, expressed human milk, and fresh food. On the other hand, consumers were unlikely to consider cooling drinks to be necessary in light of the hurricane and the price of ice. Moreover, the increased price might have incentivized other entrepreneurs from surrounding areas with power to follow suit and increase the overall supply of ice in Raleigh. Overall permissivists argue that by allowing the Icemen to price gouge, the pain of the ice shortage in Raleigh would have been significantly lessened and life could have returned to normal more quickly than if the Icemen had been apprehended by the authorities.

Such arguments take the capacity of price gouging to promote allocative efficiency as justification for permitting the behavior. However, restrictivists can object to these arguments by conceding that while price gouging may be a way to achieve a more Pareto efficient allocation of essential goods, it is not necessarily the only way to do so. This restrictivist argument holds that alternative non–market based allocative systems, such as caps on purchasing and rationing, can encourage consumers to conserve goods without using increased prices. Moreover, under such circumstances, authorities and charities can intervene to produce, transport, and distribute essential goods based on their assessment of relative need or by way of a lottery system (Snyder Reference Snyder2009b).

Such arguments do not undermine the importance of allocative efficiency but do cast doubts on the need for permitting price gouging to achieve it. However, a typical permissivist response is rooted in the economic theory related to informational efficiency. Informational efficiency refers to the capacity of an allocative system to collect and convey information to decision makers. Non–market allocative systems like those endorsed by Snyder typically are less capable of effectively collecting, analyzing, and acting on information that is chaotically dispersed during a state of emergency. Adopting a Hayekian argument, permissivists often contend that decentralized systems of market exchange among self-interested actors are the best way to signal information about the supply and demand for goods (Hayek Reference Hayek1945; Zwolinski Reference Zwolinski2009; Brennan and Jaworski Reference Brennan and Jaworski2015; Munger Reference Munger2011).

The importance of informational efficiency is only heightened during a state of emergency, when the resources of central authorities and charities are stretched thin. As such, it makes sense to allow markets to simultaneously collect and spread information about the relative scarcity of essential goods and to provide incentives to individuals and firms to distribute those goods efficiently without the need for coercion or persuasion during emergencies. Therefore the informational efficiency benefits of price gouging bolster the allocative efficiency benefits of price gouging.

Price systems that exhibit informational and allocative efficiency can disperse information and incentivize necessary action as desired. Therefore price gouging can aid a return to relative normalcy in emergency-stricken areas. It is worth noting that these efficiency justifications for permitting price gouging are conditional. They are conditional on buyers and sellers being able to communicate with each other and on sellers being able to compete with one another. If these conditions are not met, then the market cannot play an effective allocative role, and price gouging will fail to deliver beneficial results. Zwolinski (Reference Zwolinski2008) acknowledges that in some emergencies, markets seem completely out of place. For example, if an individual is drowning, it seems inappropriate for a passing boat captain to offer to rescue this victim only if the victim pays $1 million. In this case, putting aside the broader concern about commodifying what might be a morally required rescue, markets are inappropriate as an allocative mechanism. This is because there is no competition for rescuing the drowning person, nor is any likely to emerge. If there were competition, then barring collusion among the boat captains, the individual drowning would be saved for a far more reasonable price than $1 million.

The conditional nature of these justifications for permitting price gouging is evident in the nonideal nature of the permissivist argument. For instance, Zwolinski (Reference Zwolinski2009) concedes that it would be best if price increases during states of emergency could be capped at levels that allow for their beneficial effects while simultaneously minimizing the number of vendors reaping windfall profits from the misery of buyers, all while not exacerbating existing inequities. However, given the complex dispersion of information in normal times, and especially during emergencies, he argues that it would be fiendishly difficult to establish such a price ceiling. As he notes, “what hope does a merchant or legislator have, even if she is lucky enough to have a PhD in econometrics, of predicting the [exact] level of price increase necessary to attract supply to where it is needed?” (301). Given this difficulty, Zwolinski urges that we err on the side of caution by promoting markets and tolerating price gouging even during emergencies.

The conditionality of the argument points to the limits of philosophical analysis. The two efficiency justifications for permitting price gouging will only operate in an actual state of emergency if the markets in question are capable of sustaining sufficient competition among sellers. This point can be further substantiated by considering economic theory. The impact of price controls, such as anti–price gouging regulations, is dependent on the composition of a market. Under conditions similar to perfect competition, price controls will disincentivize production due to the artificial decrease in price. However, under cases of imperfect competition, such as monopoly or oligopoly, where there is a high degree of market concentration, price controls can in fact incentivize production despite the artificial decrease in price (Bronfenbrenner Reference Bronfenbrenner1947).Footnote 11 This is another example of the conditionality of the efficiency justifications for permissivism. Clearly the implications for permitting or restricting price gouging are highly dependent on the particularities of a market. Thus, while efficiency considerations are usually taken as justifications for permitting price gouging, there are important instances in which they in fact justify restricting price gouging.

The applicability of these efficacy justifications to any particular emergency will depend on the specific composition of the markets in question. If a market exhibits relatively low degrees of market concentration and more closely resembles perfect competition, then there are strong reasons of efficiency to permit price gouging. On the other hand, if a market exhibits a high degree of market concentration, then efficiency considerations may justify restricting price gouging. Determining those specifics for any particular emergency remains an empirical issue and therefore beyond the immediate scope of this article. Philosophers can provide the conceptual tools to aid in empirical investigations, but to determine whether those conditions hold requires going out into the world to check (Favor and Lamont Reference Favor and Lamont2009; Jaworski and Singer Reference Jaworski and Singer2020).

Moreover, permissivism is not the only approach. Restrictivists typically accept the potential of price gouging to promote allocative and informational efficiency but suggest that prices of essential goods should not be permitted to soar during emergencies because this can further exacerbate existing inequities. We survey this restrictivist approach next.

Restrictivism and Equity

Restrictivist accounts hold that price gouging is bad and therefore ought to be restricted by government regulators. One argument in favor of authorities restricting price gouging focuses on equity concerns. The argument goes that price gouging undermines equitable access to essential goods. In other words, those who are most vulnerable during an emergency are priced out of a market by those with larger cash reserves. This entails that markets fail to serve the needy, and price increases that are only inconveniences for the wealthy become existential threats to the poor (Snyder Reference Snyder2009a, Reference Snyder2009b).

The restrictivists are right to point out that the permissivist account is compatible with inequity. Allocative efficiency, understood as Pareto efficiency, which is used to justify price gouging, is compatible with highly unequal distributions of goods because on this formulation, efficiency is separable from equity. Therefore the efficient markets praised by permissivists can lead to the inequity that concerns restrictivists. Permissivists counter that concerns over equity can be mitigated by both long-run and short-run policies. In the long run, government policy can act to redistribute wealth more equitably and thereby minimize the disadvantages price gouging places on the poor in emergencies. In the short run, governments can provide subsidies to the poor so that they are then able to afford essential goods even if price gouging occurs.

Restrictivists are typically unconvinced that these measures will succeed in leveling the playing field enough to justify price gouging. Instead, authors such as Ilan Noy (Reference Noy, O’Mathúna, Dranseika and Gordijn2018) and Jeremy Snyder (Reference Snyder2009a, Reference Snyder2009b) have proposed alternative allocative mechanisms. They recognize that if price constraints are introduced in isolation, then the most likely scenario is that goods will be distributed not on the basis of fairness but on the basis of potentially arbitrary factors, such as the ability to find and travel to a seller or having time to queue before a store opens (Snyder Reference Snyder2009b; Noy Reference Noy, O’Mathúna, Dranseika and Gordijn2018). One remedy for this is to combine price ceilings with quotas on the maximum amount of goods that can be purchased by an individual. Other solutions involve a central allocative authority that would distribute goods either on the basis of need or randomly, as well as supplier subsidies (Snyder Reference Snyder2009b; Noy Reference Noy, O’Mathúna, Dranseika and Gordijn2018).

Both Noy and Snyder accept that these alternative nonmarket allocative mechanisms will not be perfect. Random allocations will not track need, price caps can create black markets, and quotas can be circumvented by visiting different stores. Even supply-side subsidies might be hard to distribute to small businesses (Noy Reference Noy, O’Mathúna, Dranseika and Gordijn2018). But where the permissivists rest on Hayekian arguments for the informational efficiency of prices in a market system, the restrictivists combine confidence in the government’s ability to distribute goods equitably with tolerance of allocatively inefficient outcomes. While the proposed restrictivist emergency regulations stand in need of greater articulation and defense, equitable distributions do remain an important concern when evaluating the ethics of price gouging. Equity concerns potentially oppose the permissivist efficiency justifications discussed earlier.Footnote 12

Another line of argument that is sometimes thought to justify restrictivism focuses on the supposed threat that price gouging poses to prosocial values like cooperation and solidarity (Sandel Reference Sandel2010). This argument rests on the premise that the symbolic impact of charging one’s neighbor exorbitant prices during an emergency can cause resentment within society and erode public trust and cooperation. These effects might well be strengthened when such behavior is countenanced by state policy. We dub this the symbolic argument. Footnote 13

The worry that price gouging can undermine public virtue is of course legitimate. Market institutions can only operate with minimally stable social bonds. When there is pervasive distrust between buyers and sellers, markets can no longer ensure the efficient allocation of goods. Therefore there is a legitimate worry that the symbolism of price gouging can actually undermine any and all efficiency benefits. However, while we think that the symbolic argument might provide good reasons for individuals not to price gouge, it is far less potent when considering permissivism as a policy position. For one, states might plausibly want to keep symbolic considerations out of their design of business regulation. According to influential theories of business ethics, the ethics that guide behavior in the marketplace are rightly insulated from standard understandings of what constitutes prosocial behavior (Norman Reference Norman2011; Heath Reference Heath2014). The staged competition of the market for social benefit makes collaboration in some instances antisocial (as when companies form cartels). Likewise, it can render as prosocial at the societal level what appears to be ruthless behavior at the individual level.

Furthermore, even if price gouging does symbolize an erosion of public virtue and trust, it is not obvious that public trust would be improved by restricting price gouging. This is because when the state restricts a particular behavior, it becomes more difficult for citizens to practice truly virtuous action in the marketplace. There is, arguably, nothing morally commendable in an individual or firm refraining from price gouging during times of crisis simply to obey the law (Sample Reference Sample2003, 86–87).Footnote 14 On the other hand, if such behavior is permitted, then those who choose to refrain from price gouging (we give some examples later) can be better identified as publicly virtuous and trustworthy. To those concerned with the symbolic effect of price gouging, we suggest that the solution is not to restrict vicious behavior through state action but to promote virtuous action through individual choice. Those who maintain that laws should routinely mirror a society’s moral values, however, will hopefully still gain from our later discussion of the differences that crises make to arguments for price gouging. After all, even those concerned with the moral symbolism of price gouging regulation should also be interested in the pragmatic costs and benefits of such regulation.Footnote 15

Fundamentally, it is not our goal in this article to defend either permissivism or restrictivism. Rather, we intended to articulate the various justifications used to defend these positions. None of these justifications operates in a vacuum, and they must commingle and be evaluated empirically in particular cases (Favor and Lamont Reference Favor and Lamont2009). However, the justifications for a light or heavy hand on prices identified in the existing literature have thus far been centered on price gouging in localized emergencies, such as the aftermath of Hurricane Fran in Raleigh. It is time to consider the wrinkles that the global coronavirus pandemic introduces to these existing accounts of price gouging.

CRISIS AND PRODUCTION

Local Emergencies and Global Crises

Price gouging occurs during disasters. However, not all disasters are created equal. Hurricane Fran inspired the paradigmatic case of price gouging and serves as a paradigmatic case of an emergency. The hurricane hit specific regions, leaving other regions, such as Goldsboro, relatively unaffected. Moreover, the hurricane did not linger in any one place long. Within a single night, Hurricane Fran had come and gone from Raleigh, North Carolina. We take the localization of the hurricane and its relatively quick dissipation as paradigmatic of an emergency.

SARS-CoV-2 and the associated disease COVID-19 are nothing like a hurricane. The virus is not highly localized and has been slow to dissipate. This is a very different kind of event. We have opted to dub this kind of event a crisis. It is exemplified by its global spread and its temporal duration.Footnote 16 Of course, there is no hard line that distinguishes emergencies from crises. Both geographic spread and temporal duration operate along a continuum. This means we can construct a conceptual space, as represented in Figure 1, with the upper right typified by crises and the lower left typified by emergencies.

Figure 1: The Crisis/Emergency Continuum

We have primarily focused on crises and emergencies because these two types of disasters have been the primary focus of the existing price gouging literature and the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 has brought the impact of crises into sharp relief. Other areas in the conceptual space, long-run local disasters and short-run global disasters, are logical possibilities and might be instantiated by various cases, although we leave philosophical analysis of those areas for future work. Furthermore, some emergencies impact larger regions than others, and some crises impact smaller regions than others. Likewise, some emergencies last longer than other emergencies. Hurricane Fran moved on from Raleigh in a single night, but Hurricane Harvey lingered over Houston, Texas, for multiple days, causing massive damage and untold suffering. Even the coronavirus pandemic became less global, with islands like New Zealand and Taiwan largely free from SARS-CoV-2 (but not the flow-on effects of restricted travel and economic shocks). However, despite the vague boundary between emergencies and crises, we believe that it is a robust distinction that can illuminate cases for the purpose of understanding the regulation of price gouging. There may be difficult border cases, but we do not believe that their existence threatens the essence of our analysis.

Moreover, given that the word emergency is both a type of disaster and a part of a legal category that designates disaster areas, it is necessary to clarify that “state of emergency” (or “public health emergency”) can apply to what we designate as “nonemergency” disasters, such as the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In such cases, the regulatory state of emergency can be in effect for an extended time period (typically involving multiple renewals) and cover a wide geographical area. Every state in the United States, for example, is at time of writing under some emergency order because of the pandemic (National Governors Association 2020). Therefore, while there is a natural association between states of emergency and emergencies, the legal and regulatory designation of “emergency” is equally applicable to crises, including the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

The distinction between emergencies and crises is important to the ethical implications of price gouging because economic responses to emergencies and crises develop differently. Consider once again the Icemen of Goldsboro. Those young men were able to price gouge because Goldsboro was relatively unaffected by the hurricane that devastated Raleigh. The price gouging opportunity was available because of the localization of the emergency. If the ice had become scarce in Raleigh due to a crisis that affected all nearby regions, then it would not be possible for men in Goldsboro to engage in price gouging. Moreover, the localization of an emergency might entail that more public-minded actors can act to increase supply during the emergency. Even if the men from Goldsboro had not decided to charge as much as the market would bear, they could have supplied the ice only at the additional price necessary to cover their costs or for free. This less avaricious, or charitable, behavior would also be less likely in a crisis because everyone would be impacted and their resources stretched. Of course, within a crisis, not all regions are impacted equally. For example, during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States, New York City became a major hot spot for COVID-19, while regions of West Virginia did not report a single case. However, while the severity of a crisis may not be distributed evenly, its impact is felt everywhere simultaneously, directly or indirectly. In a crisis, nowhere is completely safe, and this reduces the ability for markets (or charity) simply to channel goods from places of plenty to places of scarcity.

Similarly, the difference in time spans between emergencies and crises has important implications. An emergency ends relatively quickly, but urgent need will require rapid mobilization of goods in the short run. Crises are also urgent, as demonstrated by the rapid spread of the coronavirus. However, as crises persist over longer time spans, it is necessary also to consider longer-run plans to provide constant and reliable streams of essential goods as the crisis unfolds. As such, crises highlight allocative challenges not discussed in the emergency-focused price gouging literature. This literature to date sees the paradigm case of price gouging as being like the Goldsboro Icemen, providing a short-term mobilization of resources over short distances. It has paid insufficient attention to the ethical and regulatory implications of those kinds of global disasters from which Matt Colvin tried to profit by becoming a hand sanitizer kingpin or that have caused the price of N95 masks to skyrocket. This focus on emergencies rather than crises is of course understandable. Prior to the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2, there had not been a global crisis on a similar scale in at least a generation, while emergencies occur many times a year. However, in the face of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19, it is necessary to enrich the philosophical accounts of price gouging.

Production Incentives

Price gouging in a crisis evokes similar reactions as price gouging in an emergency. Intuitively, many consider it morally abhorrent and condemnable, as evidenced by the reaction to the Matt Colvin, 3M, and Amazon cases in the introduction. Moreover, similar philosophical justifications can be deployed for the permissibility and restriction of price gouging in a crisis as in an emergency. Price gouging can, given the proper conditions, facilitate allocative and informational efficiency, and this can act to justify permitting price gouging. On the other hand, price gouging during a crisis can also cause inequitable distributions that disadvantage those most in need, and this can be used to justify restricting price gouging. But analysis of crises highlights an underanalyzed justification for permitting price gouging: production incentives. Production ought to be distinguished from supply. The supply of essential goods is simply the capacity and willingness of vendors to sell goods for given prices. Production relates to the technological means by which materials are transformed into goods and is usually conceived in economics as a combination of capital inputs and labor inputs. Crucially for our discussion of price gouging, production is a more important determinant of supply in crises than in emergencies.

As a global phenomenon, a crisis is likely to entail that there is a global shortage for essential goods. In the case of an emergency, there is a shortage only in the affected region, but in the case of a crisis, everywhere is affected. Therefore simply reallocating the existing stockpiles of goods will be insufficient. The solution to a global shortage is to increase production. If manufacturers were able to increase their productive capabilities and invest the necessary resources to increase actual production, then the global shortage could be mitigated and potentially eliminated. This eliminates the problematic trade-offs necessitated by reallocations during a crisis.

Price gouging incentivizes increased production by manufacturing firms. When prices increase dramatically during a crisis, it becomes more profitable for firms to increase their productive capabilities and to allocate more resources for the production of essential goods.Footnote 17 Consider the corporation 3M, which has been a major producer of N95 masks in the United States. Since the onset of the crisis, 3M has increased the production of N95 masks. The decision to increase production is based on information concerning the shortage of such masks. In the case of a major corporation and a highly publicized shortage, such as for N95 masks, this information may be conveyed by the media and internal studies conducted by 3M. For smaller firms that may not have access to such sources, or for global shortages of a more obscure product, such as a certain size of pipette or reagent needed for standardized coronavirus tests, this information might best be transmitted by the market (Weaver and Ballhaus Reference Weaver and Ballhaus2020). The market would signal through price gouging the need for increased production, and firms could act accordingly. This furthers our point that while price gouging can be justified by efficiency concerns or, in this case, production concerns, it only does so conditional on other factors, such as market structure. If the market were more dispersed among smaller producers and the essential good less reported on by the media, then price gouging might play a crucial role in conveying information to incentivize increased production.

Price gouging can also incentivize increased production by luring firms not currently engaged in the production of essential goods to change their productive capacities. During the coronavirus pandemic, distilleries across the United States shifted some of their productive facilities away from spirits and toward hand sanitizer. Under normal conditions, it likely would be unprofitable for distilleries to shift production in this way, but the increased price for hand sanitizer during the pandemic made it profitable. The result was increased supply of hand sanitizer, and this served to help combat the spread of the virus. Both increased production by existing manufacturers of essential goods and increased production by new manufacturers are likely a result of price gouging, and both serve to mitigate the severest consequences of a crisis.

When new firms enter a market in response to a disaster, this serves not only to increase gross production but also to dilute market concentration. This is highly salient to the regulation of price gouging because the impact of price controls is dependent on the degree of market concentration among sellers. When there is low market concentration, in something resembling perfect competition, price controls generally decrease allocative efficiency. However, in monopolistic or oligopolistic markets, price controls can actually increase allocative efficiency, as discussed earlier. Therefore, as more firms are lured into a market in response to a disaster and subsequent price hike, the market concentration of sellers is diluted. This entails that price gouging is likely to lead to an increase in allocative efficiency. Importantly, this dynamic process is more likely to reach an efficient equilibrium in response to a crisis rather than an emergency. This is because when a firm decides to enter a new market, it faces barriers to entry. One such barrier is time. In short-run emergencies, there is likely an insufficient amount of time for new firms to enter the market and thereby increase gross output and dilute market concentration. On the other hand, during a long-persisting crisis, the barrier to entry that time poses is likely to dissipate.Footnote 18

Of course, it is possible for firms to increase production without the incentive of increased prices. Some of the distilleries that have shifted to producing hand sanitizer have decided to give it away, either out of a sense of obligation and duty to aid in the fight against the virus or to accrue a good reputation among the public or regulators. These incentives should not be overlooked. Indeed, in emergencies, large retailers are often motivated to maintain their reputation by not price gouging, even where price gouging is legally permitted (Horwitz Reference Horwitz2009). But the argument for permissivism about price gouging in crises rests on the plausible assumption that there is additional production that could be stimulated beyond that which would be stimulated by reputational or ethical concerns. Even if these manufacturers were motivated by nothing but greed, production of essential goods would be increased due to the higher prices induced by price gouging. Furthermore, even altruistic firms primarily interested in helping those in need might require price increases to offset the additional costs of increased production. As such, allowing higher prices would result in increased production of essential goods (under favorable conditions, as discussed earlier and later). This in turn would lead to better overall outcomes.

The benefits of increased production would apply to emergencies, but increasing production is likely to be more feasible during crises. In an emergency, it would clearly be beneficial if there were simply more essential goods available. However, given the relatively short time span of an emergency, it is usually unprofitable for a firm to drastically change its production strategy. The investment in capital and labor would likely be too large given the relatively transient nature of an emergency. Furthermore, the emergency is likely to entail local losses of electricity and disruptions to labor markets, transport networks, and supply chains. This entails that it is likely more cost-effective to transport from nearby areas than to produce goods from inside the disaster area. Crises are different. There is no clear “disaster area” as such. And it is or can be made profitable for at least some firms to change their production schedules in light of the crisis. It is once again worth emphasizing that increased production is a justification for permitting price gouging during a crisis but that this does not entail that price gouging must necessarily be permitted during any crisis, let alone the coronavirus pandemic. Moreover, it does not entail that it is impossible to increase production during an emergency. As such, the efficacy of price gouging to spur increased production will depend on market structure and the technological constraints associated with particular essential goods. Therefore, at most, we can conclude that increased production is a conditional justification for permitting price gouging during a crisis. Furthermore, it is a justification that might apply to some emergencies. However, since increased production will typically be much more feasible during crises, this conditional justification for price gouging is likely more applicable to crises than those emergencies that have traditionally motivated the philosophical price gouging literature.

Restrictivism in Crisis

The shift in focus from emergencies to crises heightens the importance of production incentives, which can act as an additional justification for the permissibility of price gouging. However, this shift from emergencies to crises also has important implications for the restrictivist position that will affect any operational account of price gouging regulation during crises like the coronavirus pandemic.

Consider a crisis in which it is infeasible to significantly increase production of essential goods in a timely manner. This will entail that concerns about inequity will count as an even stronger justification for restricting price gouging. Consider an essential medical good whose overall stock cannot be significantly increased during a crisis and that is desperately needed in multiple regions simultaneously.Footnote 19 The result will be that multiple health care systems will attempt to outbid one another, thereby drastically increasing the price of the essential good. While the signals and incentives this generates may seem to lead to the efficient allocation desired by those who would permit price gouging, the price increase will serve to greatly exacerbate existing inequities. Well-financed and better-organized health care systems will likely be able to procure far greater quantities of the essential good than their less well financed peers. The result will be pain and suffering for the worst off in society. Moreover, inequality between health care systems may be more difficult to counterbalance and remedy than inequality among individuals because health care systems are often supported by local, regional, and national governmental agencies as well as charitable organizations. These varied funding sources may undermine the feasibility of subsidies intended to rectify systemic inequality and inequity.

This crisis scenario also differs from an emergency, where, because of the locality of the disaster, it is almost always possible to transport essential goods into the emergency region. This entails that while price gouging may exacerbate inequity, this is offset by overall gains in the supply of essential goods, which often serves to improve the livelihoods of the worst off, given the presence of a functioning allocative mechanism. But regardless, price gouging can, under the right conditions, improve the welfare of the worst off by increasing the supply of essential goods. By contrast, there is no offsetting increase in essential goods in a crisis unless there is an increase in production. Of course, during a crisis, production for many essential goods can be increased, and the beneficial effects of this can aid even the worst off. Our point is that concerns for equity may be more salient in times of crisis than during an emergency, but only if there is no offsetting increase in production. Therefore restrictivism is a highly compelling position in times of crisis, conditional on static production.

Thus far, we have introduced the distinction between temporary and local emergencies and persistent and global crises, albeit recognizing that this distinction admits of some vagueness when considering borderline cases. Moreover, we have examined a major difference between paradigm cases of crises and emergencies, the relative importance of production incentives. Finally, we sketched some of the considerations and implications of this distinction for the philosophical debate between permitting price gouging and restricting price gouging. We now make some tentative suggestions regarding how well existing and pending price gouging regulations might cope with crises.

REGULATORY IMPLICATIONS

Regulating price gouging is always a difficult proposition, and this difficulty is heightened in the midst of crises like the coronavirus pandemic. The preceding theoretical analysis demonstrates the importance of production incentives during disasters. Under those conditions in which production can be incentivized, permissive policies may be beneficial, and under those conditions where it cannot be incentivized, restrictive regulations may be preferable for both efficiency and equity reasons. However, our aim here is not to provide regulatory prescriptions or a one-size-fits-all analysis of price gouging in crises, as such prescriptions must be sensitive to the complexity of existing statutes. At present, there exist various kinds of anti–price gouging statutes, which form a rough-and-ready taxonomy: 1) no statutes, 2) antitrust statutes, 3) unconscionable cost statutes, and 4) percentage increase statutes.Footnote 20 We detail these in this section.

Some jurisdictions have no statutes that limit price gouging during times of emergency. For example, in the United States, Maryland, New Hampshire, Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Wyoming, Washington, and Alaska, at time of writing, have no existing anti–price gouging statutes.Footnote 21 Other governments outside the United States that similarly lack an explicit statute restricting price gouging have tried using existing antitrust regulations to restrict price increases.Footnote 22 A notable example is the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), which (unsuccessfully) pursued regulatory action against several pharmacies for large mark-ups on hand sanitizer during the coronavirus pandemic under the 1998 Competition Act (Competition and Markets Authority 2020a).Footnote 23

Many jurisdictions, particularly in the United States, have explicit anti–price gouging statutes, which are typically triggered by declarations of a state of emergency by the executive branch of government. Some of these declarations expire, but they can and have been renewed, in one case (South Carolina) fourteen times at time of writing (National Governors Association 2020).

For those jurisdictions with anti–price gouging statutes, it is possible to differentiate them in regard to how they limit price increases. Some, such as the North Carolina General Statute 75-38, restrict price increases that are considered “unconscionable” or “unreasonable.” Another example of such language is Bill HR6472, which was introduced in response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and is currently pending in the US House of Representatives. Other jurisdictions explicitly specify a permissible percentage increase in price. Examples of such statutes can be found in states such as Oklahoma (15 OK St. §777.1) and Pennsylvania (Title 73 §232.1). Moreover, in response to the pandemic, Senate Bill 3576 likewise would allow a maximum 20 percent increase in prices for essential goods or services. This is of course only a small sampling of the existing statutes across the world. For ease of exposition, we have focused primarily on Anglophone industrialized country jurisdictions.

Regardless of the kind of anti–price gouging statute, regulation faces different challenges in crises than in emergencies. For our analysis to provide some insights about statutes, it is necessary to consider the interrelationship between disasters and other factors. This is because the impacts of price gouging in emergencies and crises are conditional on the types of goods covered by the statute, market structure, and cost increase exceptions. Given this dependence, we examine the ethical implications and justifications for permitting price gouging and restricting it. To fill in the picture and aid in the regulatory project, we consider how the ethical status of price gouging is conditional on these factors to provide a fuller and more operational account of price gouging.

Goods Covered

The permissibility of price gouging is conditional on the type of good in question. Standard philosophical analyses of price gouging during emergencies concede that there is no need for price gouging restrictions for luxury goods. Even many restrictivists concede that price gouging restrictions only make sense for essential goods, such as food, fuel, and shelter (Snyder Reference Snyder2009a). This difference between essential and luxury goods is reflected in existing anti–price gouging statutes. Massachusetts state law only covers fuel, while others, including the New York state statute, include health and safety goods. Some statutes, such as those in Alabama and Pennsylvania, include all goods (Zwolinski Reference Zwolinski2008, 370).

In the midst of the coronavirus crisis, it has become clear that beyond essential and luxury goods, there is a third category of reserved goods. These are goods that are temporarily reserved for individuals inhabiting certain social roles. For example, a rough consensus developed during the early days of the coronavirus crisis that protective equipment, such as N95 masks, ought to be reserved for frontline health care workers.Footnote 24 It is worth noting that this third category of goods has not been reflected in US anti–price gouging bills proposed in the wake of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Specifically, HR6264 applies only to “goods or services identified by the Secretary of Health and Human Services as vital and necessary for the health, safety and welfare of consumers” and allows for an “increase in the cost of services or the cost of acquiring, producing, selling, transporting, and delivering goods.” Likewise, Senate Bill 3576 applies only to essential goods and services. Notably, HR6472 applies to any good or service. Thus, while there are differences between the existing proposals in terms of which goods they cover, the bills fail to incorporate the third category of reserved goods.

This is important because the status of reserved goods can impact certain justifications for the permissibility of price gouging that could be relevant for crisis-focused regulation. Recall that informational efficiency mediated through the price system was taken as a justification for price gouging. Underlying this was the idea that there would be a large number of independent buyers competing with each other. However, given that reserved goods are often purchased in bulk by particular organizations, such as hospital systems, the need for a dispersed information system becomes less necessary. Governments might be able to direct production and distribution of reserved goods in ways that might not be feasible for essential goods made available to all. The result is that there might be less justification for permitting price gouging for reserved goods, but crucially, this is still a conditional conclusion. If price gouging does incentivize increased production for reserved goods, then this consideration could outweigh the lessened need for informational efficiency.

Cost Increase Exceptions

Another consideration for the ethical implications and justifications for price gouging during crises is the status of cost-related exceptions. Many of the existing US statutes and proposed bills explicitly incorporate exceptions for price gouging only if those price increases reflect “justifiable” increases to costs. For example, all US jurisdictions with existing price gouging statutes, except Texas (Tex. Bus. & Com. 17.46.27) and Michigan (Mich. Comp. Laws § 445.903), explicitly make some exception for price increases that reflect increased costs faced by the firm.

Moreover, the recent bills proposed in the US Congress each incorporates similar, but distinct, clauses related to cost-related exceptions.Footnote 25 Clearly legislators are sensitive to the fact that disasters often cause significant increases to costs and that firms ought to be able to reflect those increases in costs by raising the prices of highly demanded goods. However, in assessing the ethical status of price gouging regulation, it is important to recognize that while these cost increase exceptions might seem perfectly justifiable and straightforward, practical implementation of them might founder (Zwolinski Reference Zwolinski2008). Even in emergencies where the impacts of disasters are generally more localized and persist for a shorter duration, it is often difficult to identify which costs are increased by the emergency and to what extent. This identifiability problem is likely to be exacerbated by the global spread and longer persistence of crises. How might one translate the costs, for instance, of rearranging one’s production line to incorporate social distancing, or a more lenient sick-leave policy, into a price increase per unit sold? Finally, many existing anti–price gouging statutes place the onus on the seller to “prove” that its price increases are justified (e.g., California’s). The risk of reputational damage of having to prove that firms’ prices legitimately reflected allowable cost increases adds an additional cost for firms operating during disasters and could be contributing to a chilling effect on manufacturing (Ondeck and Tarr Reference Ondeck and Tarr2020).

Indeed, those who would regulate price gouging in a crisis face an especially difficult task. Consider the difference between manufacturers and intermediaries. Manufacturers engage in the process by which raw materials, labor, and capital are combined, resulting in finished goods. Intermediaries serve to distribute produced goods to consumers, though in many cases a single firm can be both producer and intermediary. In emergencies, the most pressing problem is often redistributing goods from unaffected areas to affected areas. Therefore encouraging entrepreneurial behavior by intermediaries is often, though not always, most important in cases of emergencies, as evidenced by the Goldsboro Icemen. However, manufacturers are often more important in crises, as only they can increase production. Furthermore, if price gouging were permitted and all profits were directed toward intermediaries rather than manufacturers, then there would be no incentive to increase production, thereby severely undermining the justification for permitting price gouging during a crisis, while simultaneously increasing inequity.

Given the importance of increased production for minimizing the deleterious impacts of disasters, it is reasonable that cost increase exceptions in a crisis ought to be constructed so as to minimize disruptions to production and to eliminate any disincentives to produce in disaster-affected areas. Therefore it is important that the increased cost exception clauses target production costs in times of crisis while preventing mere mark-ups by intermediary actors.Footnote 26 This might require the incorporation of inflation-related costs into increased cost exceptions, which would not be particularly salient with emergencies (Ondeck and Tarr Reference Ondeck and Tarr2020). The geographic reach of crises also seems to bring out the familiar problem in federal systems of a patchwork of different cost increase exceptions that are less salient in more localized emergencies (Ondeck and Tarr Reference Ondeck and Tarr2020). Regardless, it is clear that given the increased importance of production incentives for crises, price gouging regulations ought to be sensitive to the distinction between crises and emergencies when crafting cost increase exceptions.

Market Structure

Finally, the prospects for price gouging to incentivize increased production of essential and reserved goods, as well as the potential efficacy of governmental regulations, will depend on the market structure for manufacturers. We identify three aspects of market structure that are relevant to the regulation of price gouging: 1) manufacturing concentration, 2) supply chain complexity, and 3) producer diversification.

Let us consider manufacturer concentration first. If only a few firms produce an essential good within a particular jurisdiction, then restricting price gouging does appear to be a potential alternative. Recall that one of the major arguments in favor of permitting price gouging was the lack of viable alternatives to a market-based allocative mechanism. However, if production is concentrated among only a few firms, then it becomes more feasible for a government to engage in command-and-control-based production and allocation. Moreover, if there is a high degree of concentration among manufacturers, it is in fact possible for price controls to increase allocative efficiency. On the other hand, if manufacturing for an essential good is dispersed among numerous small and medium-sized firms, then effective government control becomes less feasible and concerns of informational efficiency become more pronounced. Moreover, larger dominant firms are more likely to have the necessary cash reserves to sustain production even while operating at a loss (which is likely if price controls are enacted). Therefore, if manufacturing for an essential good is concentrated, then the larger firms will be more likely to successfully operate under price controls and reap the reputational rewards associated with civic-minded behavior in the midst of a crisis (Horwitz Reference Horwitz2009).

Second, let us consider supply chain complexity. Certain essential goods require highly complex supply chains in which certain component parts may be scarce and have few viable alternatives. In such circumstances, price gouging may be necessary on the part of manufacturers in order to meet increased costs. For example, the production of COVID-19 diagnosis tests is limited by the availability of key components, such as RNA reagents. Without this key component, it is impossible for manufacturers to produce the necessary testing kits (Satyanarayana Reference Satyanarayana2020; Weaver and Ballhaus Reference Weaver and Ballhaus2020). However, RNA reagents are now a highly sought-after resource. This increase in demand very well could have spurred a bidding war among diagnosis kit manufacturers, thereby increasing the price. The result is that the cost of manufacturing would have increased, justifying price increases. Moreover, the production of certain key components, such as RNA reagents, often lies outside of many governments’ jurisdiction. It is usually not feasible for a government to institute a command-and-control allocative system for a resource that lies outside of its jurisdiction, making the alternative, price-based incentives to stimulate production, more attractive. On the other hand, if supply chains are relatively simple and involve only domestically occurring resources, then it may well be feasible to command increased production and thus develop price controls to restrict price gouging.Footnote 27

Third, let us consider producer diversification. Certain manufacturers may produce several different essential and reserved goods simultaneously. If this is the case, a firm faces a difficult choice of how to allocate internal resources among its varying products. In the case of the coronavirus crisis, a firm may need to decide between allocating latex toward the production of gloves, or, say, toward seals for PCR test kits for SARS-CoV-2, or toward valves for ventilators. These internal production decisions are often driven by information relayed by the price system. The relative price of latex gloves and seals and valves gives managers information on global scarcity, substitutes, and the behavior of competing suppliers (Heath Reference Heath2014). Centralized allocative systems would be hard-pressed to gather, collate, and analyze the information conveyed by prices. Therefore, the greater producer diversification is, the stronger is the argument from informational efficiency for permitting price gouging.

A Nuanced Approach

Our analysis suggests several points regarding price gouging statutes, especially in respect to crises. First, statutes should identify the new category of reserved goods. Second, during crises, cost increase exceptions should be designed so as to benefit manufacturers rather than intermediaries to prevent chilling effects on production. Third, the overall governance approach should be flexible enough to take into account market structures, including manufacturer concentrations, supply chain complexity, and consumer diversification.

In this section, we have largely focused on statutes and bills. Plausibly, it is in the ways in which bureaucratic regulators interpret and implement laws and provide other guidance that these nuances can be, and often are, addressed (Norman and Ancell Reference Norman and Ancell2018).Footnote 28 By highlighting the heightened importance of production incentives during crises, we provide a possible justification and conceptual framework for both legislators and bureaucrats as they attempt to grapple with the justifiability of price increases during crises.

CONCLUSION

SARS-CoV-2 has changed our lives, and we have argued, it ought to change the way we evaluate price gouging. Those who argue that price gouging ought to be permitted have pointed toward its beneficial effects in promoting informational efficiency and allocative efficiency. Those who argue that price gouging ought to be restricted typically do so because they contend that such behavior can exacerbate existing inequity, thereby hurting the most vulnerable members of society. We have emphasized that all of these justifications are worth considering and that all of them are conditional on other factors. However, despite their merits, existing ethical accounts of price gouging were designed for a largely different world that existed before the onset of the global pandemic.

Elaborating on and updating those accounts, we introduced a distinction between localized emergencies and global crises and contend that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic constitutes a paradigm case of a crisis. With this distinction in hand, we introduce the additional justification for the permissibility of price gouging: incentivizing increased production. This justification only becomes salient during crises due to their duration and geographic spread. However, we noted that if production could not be increased, price gouging during a crisis could become especially problematic, as it would further exacerbate existing inequities without easy remedies.

We conclude the article by considering how our analysis could further regulatory efforts during times of crisis. Ideally, regulations ought to be nimble and nuanced to account for different types of goods and different market structures. Moreover, regulations ought to target price gouging undertaken by intermediaries, who play a vital role in emergencies but who are less important in crises because they cannot reinvest profits into increased production.

One final remaining question concerns the nature and prevalence of crises. Surely SARS-CoV-2 has induced a global crisis, but how common are crises? Regulatory institutions are rarely designed with a singular event in mind, and there must be diagnostic tools for identifying crises in the future if crisis-specific regulations are ever to be initiated. We recognize this lacuna and intend to expand upon it in future work. In the meantime, it is clear that we are in the midst of a global crisis and that our ethical analysis of price gouging regulation must adapt to the new world we all now inhabit.

Acknowledgments

The development of this article was aided by Abraham Singer and Peter Jaworski’s perceptive conversation about libertarianism and the pandemic, and we thank Abraham Singer for making that conversation available online as part of his COVID’s Metamorphoses podcast series. Moreover, we thank Valerie Soon, Brian Berkey, and Mark Wells for their insightful feedback on an earlier version of this work. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their generous and helpful feedback. Finally, we thank editor Bruce Barry for support and substantive feedback.

Kobi Finestone (kobi.finestone@duke.edu, corresponding author) is a doctoral candidate in philosophy at Duke University whose research lies at the intersection of philosophy and economics. His research is primarily centered on the epistemic capacities of scientific models and the role of expectation formation and uncertainty in economic thought. He also incorporates insights from economics into interdisciplinary normative projects concerning the obligations and rights of business leaders and regulators.

Ewan Kingston is a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton University in the University Center of Human Values and the High Meadows Environmental Institute. His work considers the political morality of nonstate actors. He concentrates on the division of epistemic labor between firms, consumers, nonprofit organizations, and the state in addressing collective action problems and moral issues. He holds a PhD in philosophy from Duke University.