Introduction

In times of economic hardship, even guests can become adversaries. This is echoed in the widespread welfare chauvinistic sentiment that full access to welfare benefits should be restricted to natives (Andersen & Bjørklund, Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990; Bay et al., Reference Bay, Finseraas and Pedersen2013; Cappelen & Midtbø, Reference Cappelen and Midtbø2016; Carmel & Sojka, Reference Carmel and Sojka2021; Crepaz, Reference Crepaz2008; Reeskens & Van Oorschot, Reference Reeskens and Oorschot2012; Van der Waal et al., Reference Van der Waal, Achterberg, Houtman, De Koster and Manevska2010). At the core of welfare chauvinism is thus a preference for relegating immigrants to lower benefit levels and adopting high barriers to inclusion (Mewes & Mau, Reference Mewes and Mau2013).

This research note explores welfare chauvinistic sentiments in Germany, Sweden and the UK, using vignette experiments manipulating citizenship status and pre‐unemployment income. Our findings contribute to the growing literature on welfare chauvinism in several ways. First, by identifying a strong economic component in chauvinistic attitudes across Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, we extend prior work that has established the existence of these sentiments (Eick & Larsen, Reference Eick and Larsen2022; Magni, Reference Magni2024; Reeskens & Van der Meer, Reference Reeskens and Van der Meer2019). Notably, we find that citizenship status and income interact to create a particularly high level of welfare discrimination. This finding demonstrates how multiple disadvantaged statuses can compound to intensify welfare chauvinism and underscores the need for an intersectional approach in understanding and addressing welfare chauvinistic attitudes. Our study focuses on the role of economic factors in shaping welfare chauvinism, even though other factors are also important, such as cultural or identity‐based concerns (e.g., Van der Waal et al., Reference Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot2013).

Second, our approach quantifies welfare chauvinistic sentiments by assigning definite numerical values to essential aspects of social security, including benefit generosity, maximum benefits duration and eligibility criteria, culminating in a more exact and exhaustive evaluation of welfare chauvinism relative to previous research. We numerically articulate the degree to which respondents believe immigrants should have restricted access to the welfare state in comparison to native citizens.

Third, our nuanced measurement allows for an investigation into the degree of alignment or divergence of welfare chauvinistic sentiments from the actual governing regulations of welfare programs. Our results indicate that the survey respondents are more generous than their respective governments, even for immigrants, which introduces a level of welfare inclusivity alongside chauvinistic attitudes, adding nuance to the existing literature.

Lastly, our research distinctly identifies what we term ‘strict’ welfare chauvinism – the conviction that immigrants ought to be granted reduced access to the welfare state solely because of their immigrant status, independent of traits that might also apply to citizens, such as lack of initiative or proficiency. We thus differentiate welfare chauvinism from general welfare scepticism, isolating the unique impact of immigrant status from other potential influences on welfare state attitudes.

We employ a vignette experiment with a two‐by‐two factorial design where we manipulate citizenship status (native/Polish labour immigrant) as well as the pre‐unemployment income of a person who has lost his job (modest/high income). Our focus is on discriminatory attitudes regarding unemployment compensation.

Whether intra‐EU labour immigrants should be granted full access to the welfare state remains controversial. The freedom of movement of workers – a founding principle of the European Union (EU) – entails the abolition of any discrimination based on nationality regarding employment, remuneration, and other conditions of work and employment. Importantly, intra‐EU labour immigrants enjoy full and equal access to the host country's welfare state. This principle of equal access has turned out to be divisive, and it has been considered a driving force behind Brexit (D'Angelo, Reference D'Angelo2023). At the same time, several EU member states have asked for policy discretion to restrict immigrants’ welfare benefits (Hjorth, Reference Hjorth2016; Ruhs & Palme, Reference Ruhs and Palme2018), and we do not find much British exceptionalism in our data.

Background and expectations

Do native citizens prefer to give immigrants restricted access to the welfare state simply because they are immigrants? A large body of studies finds that people hold discriminatory sentiments towards disadvantaged groups in comparable contexts, for example when it comes to hiring‐procedures in firms, and in relation to other group‐based characteristics, such as being female or elderly (e.g., Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Ferreira and Ross2018; Blau & Kahn, Reference Blau and Kahn2017; Gorman, Reference Gorman2005). Relatedly, we explore whether natives believe that immigrants should have reduced access to the welfare system because they are immigrants – i.e., strict discrimination – and not because of some characteristic that could also be attributed to natives, such as beliefs about work ethics.

We also explore whether welfare chauvinism is more indirect and institutional, in the sense that discrimination is reinforced when disparities in one domain leads to disparities in others (Darity & Mason, Reference Darity and Mason1998; Darity, Reference Darity2005, Bohren et al., Reference Bohren, Hull and Imas2022). To exemplify from another context, if promotion decisions in a firm are based on salary histories within that firm, and job recruiters discriminate against women by giving them lower initial salaries than male colleagues, then a seemingly non‐biased promotion rule in subsequent periods still worsens the outcome for women (Bohren et al., Reference Bohren, Hull and Imas2022). Although the promotion rule is itself non‐discriminatory, female workers will be disadvantaged because they have systematically lower salaries than men, instigated by the initial discrimination.

We draw on this literature and investigate whether such institutional discrimination can be identified also in a welfare state context. According to the most recent ILO estimates by the International Labour Organisation (Amo‐Agyei, Reference Amo‐Agyei2020), immigrants in high‐income countries earn on average nearly 13 per cent less than national workers, and in some countries the gap exceeds 40 per cent. Despite similar levels of education, migrant workers tend to earn less than their national counterparts within the same occupational category. Migrant workers are more likely to work in lower‐skilled and low‐paid jobs that do not reflect their education and skills. Higher‐educated migrant workers are also less likely to attain jobs in higher occupational categories relative to nationals. Thus, following the logic of institutional discrimination, we expect natives to hold welfare discriminatory sentiments toward labour immigrants, partly because the latter have lower salaries. As previous research indicates, how much a welfare claimant has paid into the welfare system affects how deserving they are deemed to be (Van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2006; Aarøe & Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014; Kootstra, Reference Kootstra2016).

We argue that immigrants are likely to face welfare discrimination that are both strict – stemming from just being an immigrant – as well as indirect – due to having lower income than natives. However, we also expect that these two types of discrimination interact to foster a particularly strong degree of welfare chauvinism. The idea of a ‘double’ discrimination is well‐known from gender studies, often coined ‘intersectionality’, a concept that grew out of efforts to specify how race and gender relations together shape social life (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013; Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1990). According to this perspective, black women face challenges that are more complex and comprehensive than simply adding discrimination from being black and discrimination due to being a woman. Identity is not like pop‐beads: people cannot discern the ‘woman’ part from the ‘African American’ part (Spelman, Reference Spelman1988). By the same logic, we expect migrant workers to be doubly discriminated against. As far as discrimination goes, the whole may be greater than the sum of its parts. Migrant workers with low salaries could be punished more than native workers with low salaries.

We expect welfare chauvinism not only to be affected by the economic situation of the immigrants, but also by the economic situation of the natives. Low‐income natives are more exposed to labour market competition from immigration than high‐income natives (Scheepers et al., Reference Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders2002), and they are also more dependent on services from the welfare state. They may therefore consider immigrants as competitors for scarce welfare benefits, which in turn may encourage welfare chauvinistic attitudes (Van der Waal et al., Reference Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot2013; Magni, Reference Magni2021). Beyond self‐centred economic concerns, previous research suggests that sociotropic economic concerns can affect welfare chauvinism (Dancygier & Donnelly, Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2013). Focus has been on the fiscal impacts of immigration, especially how low skill immigration reduces the income of natives through its impact on tax rates and transfers (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014; Gidron, Reference Gidron2022). We expect that welfare chauvinism hinges on how people evaluate both their private as well as the national economy.

Data and design

We study welfare chauvinistic sentiments toward Polish labour immigrants in three countries: Germany representing the conservative welfare regime, Sweden the social democratic regime, and the UK the liberal regime (Esping‐Andersen, Reference Esping‐Andersen1990). We focus on Polish immigrants since they constitute a sizable labour immigrant group in all three countries. We look at unemployment compensation. Comparative data suggest that the Swedish scheme is the most generous in terms of the level of income compensation, with the UK being the least generous, with the German scheme being closer to that in Sweden.Footnote 1 The Swedish scheme can also be considered the most generous in terms of eligibility criteria and maximum duration of benefits (for details see Supporting Information Appendix A).

The survey was fielded by NORSTAT in 2022.Footnote 2 Each national sample includes around a thousand nationally representative respondents of the adult population (18+ years old).Footnote 3 The survey consists of two parts: a survey experiment where the respondents are randomly divided into four treatments, followed by a set of survey questions given to all respondents independent of treatments.

The experiment

The two treatments are defined by the nationality of the worker (native versus Polish labour immigrant) and previous income in the respective countries (median monthly income versus one and a half time the average monthly income). These incomes are expressed as specific monetary values expressed in national currencies. In all four treatments, the respondents are given the following vignette:

‘Imagine a (native / Polish labour immigrant) who involuntarily lost his job and is applying for unemployment benefits. He worked continuously for five years in (Germany/Sweden/UK) before becoming unemployed and is actively looking for a new job in (Germany/Sweden/UK). His gross monthly labour income was (median income/one and a half time the average income in Euro, Pounds, and Kronor)’.

After reading the vignette, the respondents in all treatments received the following questions:

Q1. In your opinion, what percentage of this income should he receive in unemployment compensation? Answer: Enter as percentage

Q2. In your opinion, how many months do you think he should be entitled to receive unemployment benefits? Answer: Enter number of months

Q3. In your opinion, how many months should a Polish labour immigrant/ (German/Swedish/UK) citizen have worked in (Germany/Sweden/UK) before being eligible for unemployment compensation? Answer: Enter number of months

Note that the third question only has one treatment (citizenship), while the other two have two treatments (citizenship and income). Note also that immigrants typically are viewed as deviant with negative characteristics, such as welfare scrounging (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981). Thus, if respondents are simply asked about whether they think immigrants should be denied or have reduced access to the welfare state, welfare chauvinism may simply reflect differences in beliefs about natives and immigrants (Careja & Harris, Reference Careja and Harris2022). We do not know if it is immigration status alone that instils discriminatory sentiments: natives may believe that immigrants should have reduced access to the welfare state because they are viewed as for example, lazy or undisciplined. This can be seen as ‘indirect’ welfare chauvinism, meaning that discriminatory sentiments correlate with beliefs about individual level characteristics that could pertain to natives as well. Welfare chauvinism in the ‘strict’ sense implies that immigrant status alone fosters discrimination. Immigrants should have reduced access because they are immigrants. To capture welfare chauvinism in the strict sense, we seek to hold beliefs about relevant characteristics constant in the vignette by specifying that both the native and the immigrant have involuntarily lost their job, are active jobseekers, received the same salary prior to job loss, and have worked the same number of years.Footnote 4

To explore the mechanisms behind welfare chauvinism further, we have specified a set of interaction models. The following item measures sociotropic economic concerns: ‘On a scale from 0 (much worse) to 10 (much better) how would you describe the economic situation in your country compared to five years ago?’ Economic self‐interest (egotropic) is measured as follows: ‘On a scale from 0 (much worse) to 10 (much better) how would you describe your private economy compared to five years ago?’ These moderators are expected to condition the effect of chauvinism on welfare generosity in the sense that respondents who are dissatisfied with their private or national economy are also more chauvinistic.

While our study focuses on Polish immigrants due to their strong presence in the labour markets in our three countries, this specific focus might introduce biases.Footnote 5 A few similar studies (e.g., Hjorth, Reference Hjorth2016; Kootstra, Reference Kootstra2016) have randomized the country of origin. Kootstra (Reference Kootstra2016) finds that the effects of ethnic background on welfare chauvinism diminished considerably or even disappeared after accounting for interactions with other factors like effort to find work and work history. If immigrants have a long work history and are actively looking for a new job (as in our vignettes), ethnic background is of minor importance.Footnote 6

Our study tests for the ‘costs’ of migration (unemployment compensation), not for the potential positive reactions to the economic benefits of migration. Previous research suggests that public opinion can be influenced by highlighting the economic contributions of immigrants. Hainmueller and Hopkins (Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014) found that emphasizing the economic benefits of immigration, such as the skills and contributions of high‐skilled immigrants, can lead to more positive attitudes.

Empirical analysis

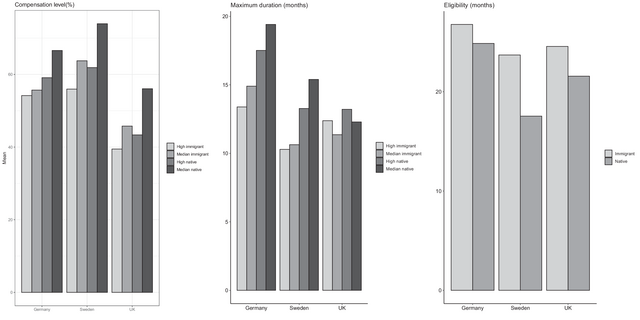

Figure 1 provides a first overview of the results. It shows the mean level of preferred level of unemployment compensation (left figure), the number of months a person should be entitled to receive benefits (the middle figure), and the number of months a person should have been working to be eligible for compensation (right figure) for all three countries. For the first two treatments (compensation level and duration), we distinguish between previous incomes that are high (‘high’) and moderate (‘median’). The figures suggest that welfare generosity varies between the three countries. Unsurprisingly, given Sweden's status as a social democratic welfare state regime, the average replacement rate preferred by Swedish respondents (mean 64 per cent) is somewhat higher than in Germany (59 per cent), which in turn clearly exceeds the level in the UK (46 per cent). The two other indicators, maximum duration, and eligibility, reveal only marginal cross‐national differences.

Figure 1. Attitudes toward unemployment compensation in Sweden, Germany and the UK given varying information about citizenship and prior income.

Note: The figure depicts attitudes toward three aspects of unemployment compensation in three countries conditional on information about citizenship and income: Unemployment compensation (left panel), the preferred length of that compensation in months (middle panel), and the length of time in months a person should have been working to receive benefits (right panel). Notice that the right panel does not contain information about the income treatment. See footnote 3 for more information about the samples.

In the early literature on welfare chauvinism, exclusion of immigrants from the welfare state tended to be a question of either‐or. Chauvinism was considered a question of preventing immigrant access to the welfare state, and just that (Andersen & Bjørklund, Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990; Kitschelt & McGann, Reference Kitschelt and McGann1997). Most current studies of welfare chauvinism specify degrees of exclusion from redistribution rather than the binary full inclusion versus full exclusion (see Careja & Harris, Reference Careja and Harris2022). By allowing the respondents to define their preferences with respect to specific monetary values, the maximum duration of benefits, and the eligibility criteria, as we have done here, we find that welfare chauvinism is indeed a matter of degree: respondents do want to include the immigrants in the welfare state, although not to the same extent as natives. But equally important, by comparing the responses from respondents with the actual welfare systems in the three countries, we observe that the respondents in most cases prefer higher levels of welfare generosity (higher replacement rate, longer duration) not only for natives, but for immigrants as well. Only when it comes to eligibility rules are the respondents more restrictive than the actual polices. For details, see Supporting Information Appendix A, where we compare the actual systems in the three countries with the respondents’ preferences, and Supporting Information Appendix C, where we have converted the respondents’ average replacement rates to monetary values. To summarize, even if the respondents show clear signs of welfare chauvinism when comparing immigrants to natives, they display a high degree of welfare inclusiveness when their preferred level of welfare generosity for immigrants is contrasted with the actual level of welfare provided by the government.

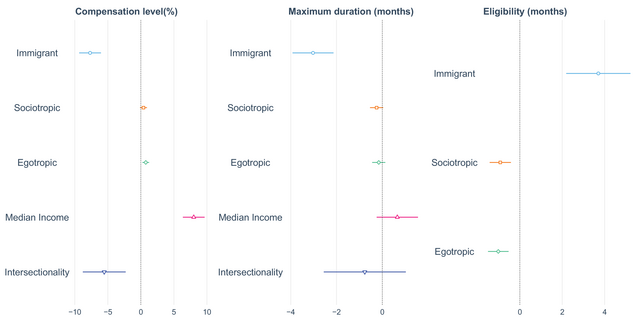

Figure 2 provides statistical tests of our theoretical expectations for the three countries pooled together with country fixed effects. In all models the F‐tests for cross‐national differences in the outcome variables were highly significant. This confirms the impression from Figure 1 that the level of preferred unemployment benefits varies markedly across the three countries (Supporting information Appendix B1‐B3 presents the effects for each country separately). We first analyze whether citizens prefer to give immigrants restricted access to the welfare state simply because they are immigrants, that is, chauvinism in the strict sense. We use a single dummy variable for citizenship to test this expectation. As indicated by the coefficient labelled ‘Immigrant’ in Figure 2, the treatment effects of citizenship status on revealed policy preferences are substantial in all countries. The signs of the effects are thus consistent with strict welfare chauvinism. All effects are significant at conventional levels (as indicated by the location of the 95 per cent confidence intervals) for all three indicators in all three countries (see Figure 2 and Supporting information Appendix B1‐B3).Footnote 7 The analysis shows that respondents who were treated with the scenario of a Polish labour immigrant as input on average prefer eight percentage points lower compensation levels, about a 3‐month shorter maximum duration, and a higher barrier – on average 4 months – for obtaining benefits compared to respondents being primed with natives as input. The effects are thus strong and consistent across the three different indicators and across the three welfare regimes.

Figure 2. The effect of citizenship and income on attitudes toward three aspects of unemployment benefits. OLS regressions for a three‐country panel.

Note: The figure presents the effects of citizenship and different economic factors on attitudes toward unemployment benefits for all three countries pooled together (N = 3041). The OLS‐models include country‐fixed effects. The lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. Immigrant is a dummy variable equal to 1(0) if the recipient is described as Polish (native). Median income is 1(0) if the recipient is presented as having a median income (1.5*median income). Intersectionality is the interaction term Immigrant*Median Income. Sociotropic (egotropic) is the effect of respondents’ perception of the country's (personal) economy during the last 5 years on a scale from 0 (much worse) to 10 (much better).

We now turn to the more indirect form of discrimination and the idea that a non‐group characteristic, pre‐unemployment income, subsequently gives rise to welfare chauvinism (see the effect of ‘Median Income’ for compensation and maximum duration in Figure 2). We see that the income levels significantly affect only the replacement rate (the effect on maximum duration not being quite significant according to conventional levels). The respondents in the three countries indicate that claimants who previously had a median income should receive an eight percentage points higher replacement rate than claimants who previously had one and a half times the average income.

Thus, in terms of replacement rates, less paid (‘median income’) claimants are not being discriminated against, quite the contrary: the positive and significant coefficient suggests that the respondents prefer the less paid claimants to be compensated by a larger share of their prior income than the highly paid (‘one and a half the average income’) claimants, irrespective of their ethnic background. As can be gleaned from Figure 1, the preferred compensation level is consistently higher for less paid claimants – a tendency that is found among both immigrants and natives. However, the same figure also suggests that the relative gap in preferred compensation between the less and the highly paid is larger for natives than for immigrants. Thus, although respondents want to treat the less paid more generously than the highly paid, the generosity is more sensitive to income among natives than among immigrants.

Building on the approach suggested by Block et al. (Reference Block, Golder and Golder2023) for assessing claims of intersectionality, we note that the interaction model presented in Figure 2 implies two hypotheses, one about immigration and another about prior income. Referring to the coefficients in Figure 2, in a model with moderated effects (t‐values in parenthesis), the coefficients for Immigrant equals ‐ 4.9 (‐4.20), Median Income 10.8 (9.22) and Intersectionality ‐5.5 (‐3.35). As indicated by the significant interaction term, intersectionality is supported by the data. The negative coefficients for both immigrants and the interaction term square well with the immigration hypothesis: respondents want to give immigrants less compensation than natives, but the negative effect is more than twice as large for the less paid group (‐4.9) than the highly paid group (‐4.9 – 5.5 = ‐10.4). Turning to the income hypothesis, the effect of being less versus highly paid is 10.8 for the natives but only half of that for immigrants (10.8‐5.5 = 5.3): income matters, but less so for immigrants than natives. It seems that the less paid immigrants can expect less generosity than the less paid natives – but only provided that the comparison is with the more well‐paid compatriots. In this relative sense, less paid immigrants do not get the same ‘welfare bonus’ as the less paid natives do.

So far, our results suggest that the economic characteristics of the immigrants reinforce already strong welfare chauvinistic sentiments. Does the effect of the respondents’ own economic concerns have a similar effect? Specifically, is welfare chauvinism associated with the respondents’ self‐centred and sociotropic economic concerns? As mentioned, the first variable (egotropic) measures the respondent's perception of their own private economy, while the second variable (sociotropic) measures the respondents’ perception of the national economic development. As shown in Figure 2, both variables have similar and expected effects across the three countries on two of the three defining characteristics of social security (see Appendix B1–B3 for the countries separately), compensation level and eligibility criteria (with the effects on maximum duration being insignificant). The signs of the estimated coefficients are thus largely compatible with the expectation that those who are satisfied with the economy, be that national or private, are less prone to welfare chauvinism. Conversely, the economically dissatisfied are more likely to discriminate against immigrants. This finding goes in the same direction as the previous ones: economic hardship – whether it afflicts migrants or natives – fuels welfare chauvinism.Footnote 8

Concluding remarks

Our findings reveal a complex picture of welfare attitudes. On the one hand, we find clear evidence of strict welfare chauvinism, The respondents believe that immigrants should have less access to the welfare state than natives simply because they are immigrants. However, on the other hand, we also find surprising elements of welfare inclusiveness. Respondents generally favoured more generous benefits for immigrants than current welfare systems provide.Footnote 9

We identify important economic components in welfare attitudes. Being less paid interacts with immigrant status, resulting in a disadvantage for the less paid immigrants in the sense that they do not get the same ‘welfare bonus’ compared to less paid natives. Additionally, respondents' own economic satisfaction tends to be negatively associated with discriminatory attitudes. While we do not discount the potential influence of other considerations, such as cultural or identity‐based concerns (e.g., Van der Waal et al., Reference Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot2013; Kootstra, Reference Kootstra2016; Ennser‐Jedenastik, Reference Ennser‐Jedenastik2018), we conclude that the economy shapes welfare chauvinistic attitudes.

Contrary to findings elsewhere, which indicate that welfare chauvinism is weaker in the social democratic countries (Crepaz & Damron, Reference Crepaz and Damron2009; Van der Waal et al., Reference Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot2013),Footnote 10 we find that welfare chauvinistic sentiments are equally widespread across the three welfare regimes. Even though the countries represent three distinct worlds of welfare capitalism, they only represent one world of welfare chauvinism.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments. This research was made possible by a grant from the Research Council of Norway (grant number 275308).

Data Availability Statement

Replication material for this study is available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/chauvinism

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: