Policy Significance Statement

Whistleblower protection systems vary accross countries based on traditions, scope, and national legislation. Due to the sensitive nature of whistleblowing, the standards for evaluating whistleblower policy effectiveness often remain vague. By examining institutional history, legislative content, and the institutions responsible for protecting whistleblowers in two case studies-South Korea and the Republic of Kosovo- this article proposes a new index to assess the effectiveness of whistleblower protection in the public sector. As a composite measure, the index facilitates cross-country comparison and can compare whistleblower protection levels in a specific country over time. The index provides methods for creating, locating, and sharing standardized data that are that are either missing or not easily accessible in different countries.

1. Introduction

Corruption presents a complex challenge for public sector organisations as it damages policy objectives and diminishes trust, especially when institutional corruption undermines the organisations themselves (Graycar, Reference Graycar2020; Thompson, Reference Thompson2017). Globally, many anti-corruption actors have failed to combat corruption effectively in recent decades. Current policy typologies mainly focus on dimensions such as types of tools, mechanisms of prevention, and intervention (Villeneuve et al., Reference Villeneuve, Mugellini, Marlen and Graycar2020). Renewed progress is possible, but it requires new strategies stressing justice, fairness, and genuine reform (Johnston & Fritzen, Reference Johnston and Fritzen2020).

To that end, international organisations like the World Bank, the United Nations, the European Commission, and the Council of Europe, among others, have reaffirmed the significance of whistleblowing as a tool, mechanism, system, and activity for preventing wrongdoing in the public sector. According to the International Organization for Standardisation (ISO) 37002:2021, whistleblowing is defined as reporting suspected or actual wrongdoing. In the last decade, many cases have showcased the tremendous impact that whistleblowing may yield on international issues (Di Salvo, Reference Di Salvo2020). Yet so far, whistleblowing has been mainly considered as a reporting procedure (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki and Graycar2020).

The United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) encourages state parties to consider incorporating into national legislation appropriate measures to protect any person who reports in good faith, any facts concerning offenses (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2004). In June 2021, the United Nations held its first special session of the General Assembly against corruption, UNGASS, which approved the Political Declaration by the UN General Assembly, a document emphasizing the link between whistleblowing and anti-corruption efforts (United Nations General Assembly, 2021). The adoption of the Political Declaration followed a joint statement issued by the G7 UK (2021) countries condemning recent attacks on whistleblowers, media, and civil society for standing up against corruption.

As documented by Thüsing and Gerrit (Reference Thüsing and Gerrit2016) in the European Union, laws of Member States vary in their definitions of whistleblowers. The European Commission’s adoption of the EU Directive 2019/1937 on the Protection of Persons Who Report Breaches of Union Law (henceforth, the EU Directive) constituted a new opportunity to harmonize whistleblower legislation among member states. More momentum emerged when the Council of Europe and the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities adopted Resolution 444 on Protection of Whistleblowers: Challenges and Opportunities for Local and Regional Governments, calling upon local and regional authorities in the EU to establish whistleblowing policies aligned with the EU Directive. This Directive was scheduled for transposition into the national legislation of the EU member states by 17th December 2021, but it was delayed (Whistleblowing International Network, 2023). Soon afterwards, the European Commission issued formal notices to 24 Member States for their lack of transposition.

The UNCAC Coalition of civil society organizations has proposed several measures for implementing the Directive more effectively. Specifically, they have called upon State Parties to establish whistleblower protection systems that go beyond the standards introduced by the EU Directive: States should establish a fund to grant whistleblowers legal, financial, and psychological support. Further, they recommend monitoring and constant improvement of whistleblower protection mechanisms, particularly by tracking and transparently reporting the number of whistleblower reports filed and their respective follow-up actions (UNCAC Civil Society Coalition, 2022). In December 2022, the United States Congress passed the Anti-Money Laundering Whistleblower Improvement Act, a bill reforming the management of the financial rewards for whistleblowers, by establishing the minimum award “not less than 10%” whistleblowers may obtain of the collections by enforcement actions (US Congress, 2022).

Measuring the effectiveness of whistleblower protection is a complex task, as it depends on factors like the country’s legal framework, cultural context, and level of support for whistleblowing from the government and broader society. To better understand these factors, this paper conducts a comparative study of two cases: South Korea and Kosovo. Specifically, the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission of South Korea produces datasets that provide valuable information on the legal framework, the number of complaints, and the outcomes of the cases. By analysing these datasets, we can gain insights into the strengths and weaknesses of the South Korean system and how it compares to other countries. To complement the South Korean data, we also examine survey data from 400 public officials in Kosovo about whistleblower protection. This survey provides a unique perspective on the attitudes and perceptions of public officials towards whistleblowing, as well as their experiences with the system. By combining this information with data on Kosovo’s legal framework and the outcomes of whistleblowing cases, we can get a more comprehensive view of the situation in Kosovo.

Based on the analysis of both datasets, this paper creates a new index, called the Index for Evaluation of Whistleblower Protection (IEWP), to compare the present levels of whistleblower protection across countries, as well as to compare those levels over time in the same country. Because enacting whistleblower protection laws is not enough to protect whistleblowers, utilizing the IEWP can help governments build and maintain more effective whistleblower protection systems.

2. Literature Review on Whistleblower Protection

The nature and mechanisms of whistleblower protection vary in different countries, often based on jurisdictional differences regarding the provision of options, channels for reporting, and the scope of protection for parties and family members (Vinciguerra, Reference Vinciguerra2018). Overall, whistleblower protection supports employees who wish to report corruption, fraud, or wrongdoing (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2016). Such protection must be meaningful and incorporated into organizational structures and policies (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki and Graycar2020). In line with international principles for whistleblower legislation developed by Transparency International (2013), reporting channels must be clearly defined to facilitate disclosure, and to promote confidence in the system (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2016).

Up to 2015, scholarship on whistleblowing in organizations mainly drew on power and motivation theories. Later Later work has covered the impact of digitalization, particularly on the regulation of data protection and the privacy of whistleblowers. Because whistleblowers are often perceived as spies (Near and Miceli, Reference Near and Miceli1985), leakers, and informers (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2019), they may not be supported by the public. As a result, individuals tend to show reluctance to report corruption because of adherence to the loyalty-betrayal paradox (Gottschalk, Reference Gottschalk2018). The need to dissociate whistleblowing from organizational disloyalty constitutes an increasing emphasis on developing effective mechanisms (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki and Graycar2020).

Developing protocols to ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of whistleblowers has been a top priority for mitigating the risk factors associated with retaliation (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, n.d.). As recommended by the OECD (2016), laws should provide comprehensive protection against discriminatory or retaliatory personnel action, including harassment at the workplace, job demotion, reprisals, and reduction of job benefits. The Global Business Ethics Survey of 2020 found that globally, a median of 61% of employees experienced retaliation after reporting misconduct in their organizations—whether in government, for-profit, or not-for-profit sectors (ECI, 2021).

To assess effective whistleblowing, five factors are especially relevant: 1) the types of whistleblowing, 2) the role of mass media, 3) evidence, 4) retaliation, and 5) legal protection (Apaza and Chang, Reference Apaza, Chang, Apaza and Chang2020). Roberts (Reference Roberts2014) similarly identified six categories of motivations that influence perceptions of the effectiveness of disclosures: personal, public, private, ethical, contextual factors, and psychological factors. In examining the role of societal culture in whistleblowing, scholars have highlighted the need to distinguish between disclosures of perceived wrongdoing that are in the interests of the powerful and those that serve to curb the abuse of power. (Vandekerckhove et al., Reference Vandekerckhove, Uys, Rehg and Brown2014a,Reference Vandekerckhove, Brown and Tsahuridub). However, insufficient attention has been paid to managerial responses to whistleblowing (Vandekerckhove et al., Reference Vandekerckhove, Uys, Rehg and Brown2014a,Reference Vandekerckhove, Brown and Tsahuridub).

2.1 Evaluating whistleblower protection effectiveness

A recent study by The Government Accountability Project and the International Bar Association analysed legislation on whistleblower protection and its enforcement in 37 countries (Feinstein et al., Reference Feinstein, Devine, Pender, Allen, Nawa and Shepard2021). This study systematically examined publicly available decisions on cases brought by whistleblowers, in terms of retaliation claims, channels of reporting, and the documented remedies. The authors concluded that the development of the legal framework regulating whistleblower protection does not guarantee the protection of whistleblowers’ rights: “A duly functioning judicial and enforcement ecosystem is equally important as the existence and enforcement of legislation”. Moreover, limited access to information remains a key challenge for assessing the effectiveness of whistleblower protection and the importance of transparency about case outcomes. One option is to publish case decisions online in searchable databases (Feinstein et al., Reference Feinstein, Devine, Pender, Allen, Nawa and Shepard2021). Other scholars compared various whistleblower protection laws to evaluate their effectiveness in protecting whistleblowers. For example, Bowden (Reference Bowden2006) analysed the legislation and implementation of whistleblower protection in Australia, the UK, and the US, and found significant variations among Australian states. He argued that more protections should be implemented. In addition, his paper compared the rationale for whistleblower legislation in the three countries and found that they have different approaches, such as the UK using public funds to help whistleblowers and the US granting whistleblowers the right to sue. Bowden (Reference Bowden2006) concluded that, although more whistleblower protection should be implemented in Australia, overall Australian laws worked better than those in the UK and the US.

Chordiya, Sabharwal, Relly, and Berman (Reference Chordiya, Sabharwal, Relly and Berman2020) also conducted a cross-national study including Mainland China, Malaysia, Taiwan, and the US. They examined the factors that impact employees’ perceived levels of protection within an organization after whistleblowing, based on survey data from senior employees, supervisors, and lower managers in all four countries. Specifically, they considered the role of ethics-oriented climates, ethical leadership behaviours, structural provisions for ethics management, and awareness of whistleblower protection laws in enhancing employees’ perceived protection. They found that awareness of whistleblower protection laws positively impacted perceived organizational protection for whistleblowers in all four countries. An ethics-oriented climate was effective in improving perceived protection in Mainland China, Malaysia, and the United States, while ethical leadership had a positive impact in Mainland China, Taiwan, and the United States. Structural provisions such as mandatory ethics training and codes of ethics or standards of conduct positively impacted perceived protection in the United States but negatively impacted it in Taiwan. Personal and situational factors, including the perceived likelihood of retaliation and the perceived ability to effectively report wrongdoing, also significantly influenced employees’ decisions to whistleblow.

Some scholars believe that whistleblower protection law cannot be truly effective. For example, Martin (Reference Martin2003) argued that whistleblower legislation is often ineffective and can even create an illusion of protection that is dangerous for whistleblowers. He suggested whistleblowers should develop practical skills like understanding organizational dynamics, collecting data, writing coherent accounts, building alliances, and interacting with the media instead of relying on official procedures, laws or ombudspersons. He argued that the value of such skills constitutes the focus of official procedures. Promoting the development of these skills can be a more effective way to empower and protect whistleblowers (Martin, Reference Martin2003).

Providing comprehensive guidance for whistleblower legislation, 30 principles developed by Transparency International (2018) seek the goal of robust protection of whistleblowers against all forms of retaliation. To date, no law on whistleblowing aligns fully with the 30 Transparency International principles (Transparency International, 2018).

Relevant gaps in this literature include what differentiates actual whistleblowers from those who observe wrongdoing but do not report it (Vadera et al., Reference Vadera, Aguilera and Caza2009). The Whistleblower Index (Vinciguerra, Reference Vinciguerra2018) sought to explore the correlation between whistleblower protection legislation and national levels of corruption and bribery. Constraints to researching whistleblowing in organizations often include access to relevant data (Chiu, Reference Chiu2003; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran, Reference Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran2005). In Poland, for example, it is not known how many cases of whistleblowing are filed each year (Blueprint for Speech, 2018a,b). Blueprint for Free Speech has published EU country briefing papers on whistleblowing laws (2018). Briefing papers on individual countries contain introductory information on the following: legislation, institutions, and procedures, ongoing developments related to whistleblowing, available data and statistics on cases, public perceptions’ trends, national capacities, and knowledge centres.

Noting the lack of a measure for the efficacy of whistleblowing across jurisdictions, Goel and Nelson (Reference Goel and Nelson2014) developed an internet-based measurement of whistleblower awareness. They found that awareness of whistleblowing was relatively more effective for disclosing corruption compared to the quality of the legislation itself. However, any assessment of the effectiveness, impact, and sustainability of anti-corruption interventions should consider whether that intervention aligns with the latest and local thinking on corruption (Wathne, Reference Wathne2022). According to a research brief by the IBM Centre for the Business of Government and the IBM Institute for Business Value (2022), agile methods like user-driven design, evidence-based solutions, and iterative workflows can help many agencies and departments improve the outcomes of their policies, regulations, and programs.

3. Case Studies

As described above, this study investigates two countries: South Korea and the Republic of Kosovo. There are several reasons for selecting these two countries. First, it is relatively easy for the authors––due to their professional backgrounds––to access relevant datasets on whistleblower protection. Second, these two countries contrast in significant ways. While South Korea is now a developed country, Kosovo is still a new country: it declared its independence in 2008. In the Corruption Perceptions Index 2022, South Korea was ranked 31st with a 63 score, but Kosovo was ranked 84th with a 41 score (Transparency International, 2023). Since these two countries also have different governance capacities, we can explore the different levels of whistleblower protection in different situations. Finally, this comparison enables us to find ways to effectively improve whistleblower protection. We can understand what we should do to protect whistleblowers effectively. Although the datasets are different enough to prevent a direct comparison, we can make a rough comparison that indicates what is missing from whistleblower protection in each country.

To that end, this paper explores the following research questions: Q1) Can we measure the effectiveness of whistleblower protection in different countries? Q2) What conditions do we need to make a whistleblower protection system work effectively in the public sector?

Assumptions for analysing the South Korea data:

-

• Data are either lacking or not available on the following: IEWP qualitative sub-indices such as perceptions of public officials, experts, citizens, and whistleblowers, as well as experiences of whistleblowers.

Assumptions for analysing the Republic of Kosovo data:

-

• Data are either lacking or not available on the following: IEWP quantitative sub-indices such as rates (of requests and acceptances) for protecting whistleblowers, and 2) qualitative sub-indices, such as perceptions of experts and citizens, as well as experiences of whistleblowers.

3.1 South Korea

In this section, we evaluate the effectiveness of whistleblower protection in South Korea. We will then delve into the Act on the Prevention of Corruption and the Protection of Public Interest Whistleblowers, and conclude the section by illustrating the state of whistleblower protection in South Korea by using relevant datasets.

The ACRC is not the first anti-corruption agency in South Korea: its forerunner, the Korea Independent Commission Against Corruption (KICAC), was established in 2002. President Kim Dae-jung, who led South Korea from 1998 to 2002, wanted to differentiate himself from former political leaders and demonstrate his commitment to fighting corruption by vigorously adopting and implementing anti-corruption policies (Ko & Cho, Reference Ko, Cho, Zhang and Lavena2015). As part of these efforts, he promoted the Anti-Corruption Act, established in 2001, which provided the legal basis for the KICAC (Göbel, Reference Göbel, Sousa, Larmour and Hindess2008). Kim Dae-jung’s successor, President Roh Moo-hyun (2003–2007), was also interested in fighting corruption (Min, Reference Min, Han, Pardo and Cho2022). In 2004, he launched the Consultative Council of Anti-Corruption Affiliated Agencies and held council meetings to decide how to curb corruption (ACRC, 2020). The KICAC organized and operated the council (Min, Reference Min, Han, Pardo and Cho2022). Therefore, the KICAC played a crucial and leading role in the fight against corruption in South Korea.

In 2008, President Lee Myoung-bak (2008–2012) abolished the Consultative Council of Anti-Corruption Affiliated Agencies and established the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (ACRC) as the successor to the KICAC. The ACRC integrated the KICAC, the Ombudsman of Korea, and the Administrative Appeals Commission (ACRC, 2021). The ACRC is responsible for dealing with corruption cases, complaints, and administrative appeals.

In this role the ACRC has prepared several bills related to fighting corruption, including the Protection of Public Interest Whistleblowers (2011) and the Improper Solicitation and Graft Act (2015) (Min, Reference Min, Han, Pardo and Cho2022). The ACRC has also implemented various anti-corruption entities, such as the Anti-Corruption Policy Consultative Council, established in 2017 as the successor to the Consultative Council of Anti-Corruption Affiliated Agencies (ACRC, 2020). In 2017, the ACRC also developed the Integrity Assessment tool, which estimated the level of corruption in more than 500 public agencies (ACRC, 2017). It has also adopted and implemented various anti-corruption policies, mainly under the Act on the Prevention of Corruption. This Act outlines the structure and function of the ACRC. According to the Act, the ACRC can handle complaints and corruption cases and implement anti-corruption policies. Additionally, the ACRC can recommend that public organizations consider improving their institutional weaknesses against corruption.

The Act includes several articles related to whistleblower protection measures, including guarantees for the whistleblower’s position, physical safety, confidentiality, prevention of disadvantages, and rewards. According to Article 62-2 of the Act, whistleblowers can ask the ACRC to take action to maintain their status in their organizations. Article 64-2 allows whistleblowers to request safety from the ACRC, which can then ask the police to provide protection. Article 64 prohibits the disclosure of whistleblowers’ personal information, while Article 62 prohibits any disadvantageous actions against whistleblowers. Finally, according to Article 68, if whistleblowers help public agencies achieve property gains or prevent damage, the ACRC can recommend that they be granted monetary rewards.

The Protection of Public Interest Whistleblowers Act also has similar provisions for protecting whistleblowers in cases related to the public interest. According to Article 17 of the Act, whistleblowers can ask the ACRC to take action to maintain their status in their organizations. Like the Act on the Prevention of Corruption, Article 13 allows whistleblowers to request safety from the ACRC, which can then ask the police to provide protection. Article 12 prohibits the disclosure of whistleblowers’ personal information, and Article 15 prohibits any disadvantageous actions against whistleblowers. Finally, according to Article 26-2, if whistleblowers help to achieve property gains or prevent damage, the ACRC can recommend that they be granted rewards.

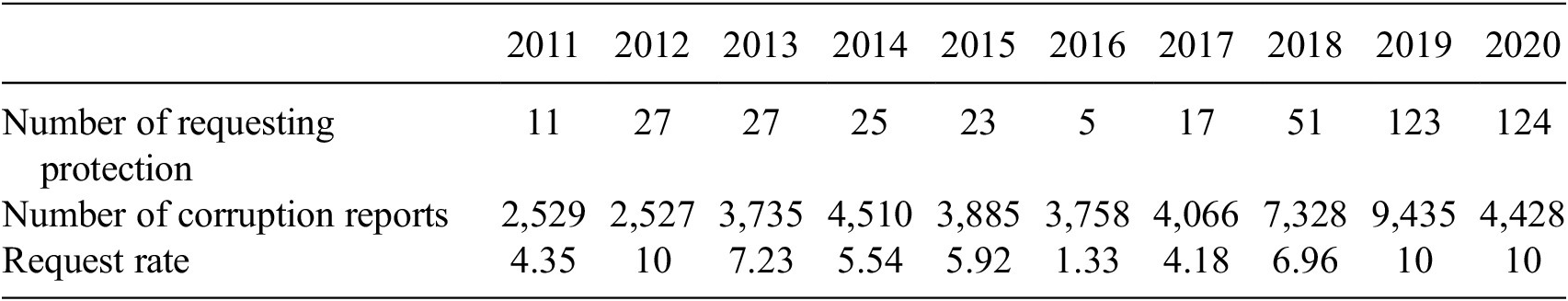

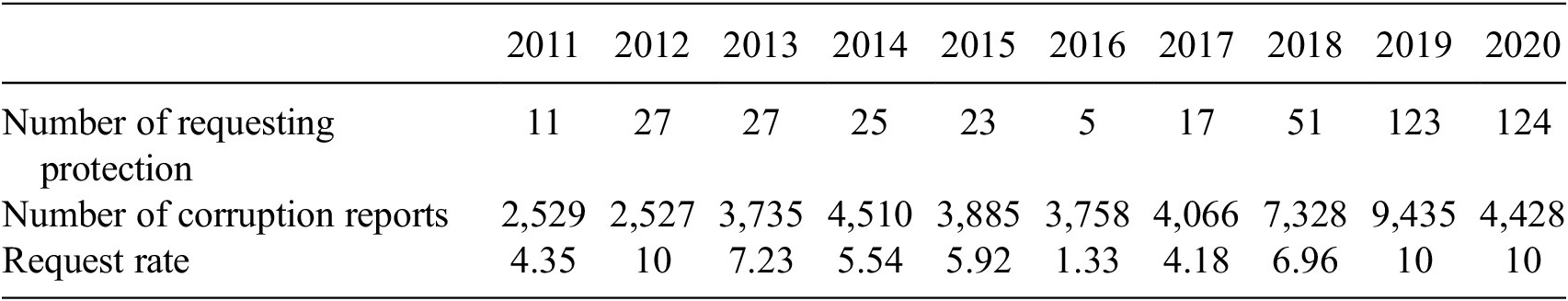

The ACRC has used both Acts to protect whistleblowers. The protection request rate, calculated by dividing the total number of protection requests by the total number of corruption reports, is shown in Table 1 as an overall trend from 2011 to 2020. Although it decreased in 2016 and 2017, the number of petitions for protection has usually climbed over this time. In 2011, there were 11 requests for protection; in 2020, there were 124. From 2,529 in 2011 to 4,428 in 2020, the number of reports of corruption also grew. However, it varied between 2016 and 2017. Since 2016, the total number of requests for protection has often increased faster than the total number of reports of corruption.

Table 1. Request rate of South Korea from 2011 to 2020

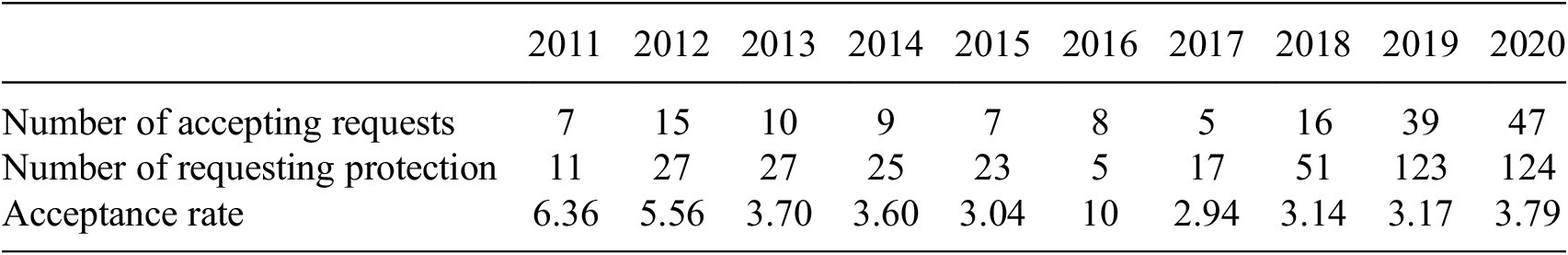

Table 2 shows the trend of the protection acceptance rate, i.e., the number of accepted protection requests divided by the number of total protection requests from 2011 to 2020. The number of accepted requests decreased from 2012 to 2015 and then increased from 2016 to 2020. In 2016, the acceptance rate was 10, while in 2011 and 2012, it was higher than 5. However, it was below 4 in the other years.

Tables 1–3 and Figure 1 show the acceptance rate, request rate, and rates for protecting whistleblowers, respectively, from 2011 to 2020. In 2012, the rate for protecting whistleblowers was 10.71. It decreased from 2012 to 2015, but in 2016, it increased slightly due to the peak acceptance rate. From 2017 to 2020, the rate for protecting whistleblowers increased mainly due to the increasing request rate.

Table 2. Acceptance rate of South Korea from 2011 to 2020

Figure 1. Rates for protecting whistleblowers trends in South Korea from 2011 to 2020.

Table 3. Rates for protecting whistleblowers in South Korea from 2011 to 2020

The results of this analysis provide some meaningful insights:

-

1. South Korea should increase the number of requests for protection. A low number of requests could be due to a few reasons: reporters of corruption may not feel that they need protection, they may not be aware that the Act can protect them, or they may not believe that the Act can adequately protect them. If the low number of requests for protection is related to the second or third reasons, increasing the number of requests for protection could increase the number of reports of corruption. The increasing number of requests for protection positively correlates with the high request rate when the number of corruption reports remains constant. Since the number of these reports has increased, the number of requests for protection should increase faster than the number of reports of corruption.

-

2. The number of accepted requests should increase faster than the number of requests for protection. If this happens, both the acceptance and request rates can increase simultaneously. In 2016, for example, the acceptance rate was high, but the request rate was low. This trend is not ideal for effectively protecting whistleblowers. Therefore, both the number of accepted requests and the number of requests for protection should increase simultaneously, but the former should grow faster than the latter.

-

3. South Korea has already implemented various institutions for protecting whistleblowers, but it is still being determined whether these measures are working properly. Whistleblowers may not feel that these measures are sufficient to protect them adequately. To measure the effectiveness of whistleblower protection, we need a survey that helps us measure the perceptions and experiences of whistleblowers over a certain period.

3.2 Republic of Kosovo

As the youngest country in the Western Balkans, the adoption of anti-corruption policies was linked with Kosovo’s progress toward membership in the European Union. The first law aiming to regulate whistleblowing in the public sector, the Law on the Protection of Informers in Kosovo, was enacted in 2011 but it lacked clarity on many aspects related to its implementation (Fol, Reference Fol2017). Seven years later, in 2018, the Kosovo Parliament approved a new Law on the Protection of Whistleblowers No. 06/L-085 (henceforth, LPW). The LPW regulates the whistleblower protection system for the public and private sectors in the country. In line with the research objectives of this article, our analyses focuses on the public sector domain.

Article 3 of the LPW defines a whistleblower as any person who reports or discloses information on a threat or damage of public interest within the context of their employment relationship in the public or private sector. Adopted in 2018, one year before the approval of the EU Directive on Protection of Persons Reporting Breaches of the European Union Laws, the LPW is in line with the principles for whistleblower legislation by Transparency International (2018). Like the EU Directive, the LPW provides three channels for reporting wrongdoing in the public sector: internal, external, and the public.

Under Article 5, the LPW scope protects reporting and disclosures on the following forms of wrongdoing: offences, failure to comply with legal obligations, miscarriage of justice, endangered health and safety, damage to the environment, misuse of official duty/authority/public resources, discriminatory/oppressive/negligent acts or omissions constituting mismanagement, and information concealed or destroyed concerning the abovementioned disclosures.

Article 13 of the LPW stipulates that (a) internal whistleblowing is disclosing wrongdoing information to the official responsible for receiving such reports inside the organization, (b) the Kosovo Anti-Corruption Agency is responsible for receiving external whistleblowing cases, (c) public whistleblowing is disclosing information to the media, to civil society or to any public meeting. In the context of this research, it is relevant to note that in July 2022, with the entry into force of the new Law 08/L-017, the Kosovo Anti-Corruption Agency mandate was altered into the Kosovo Agency for Prevention of Corruption.

According to an analysis published by the Regional Anti-corruption Initiative (2021) the LPW stands in substantial compliance with the EU Directive standards concerning the rights of whistleblowers, with some minor exceptions. Like South Korea’s legislation, Article 7 of the LPW grants the whistleblowers the right to protection of their identity. Additionally, whistleblowers are guaranteed the right to the confidentiality of reported information sources.

The LPW similarly grants protection to whistleblowers against any form of damaging action. It guarantees these rights during and after the procedures of the administrative investigation. Whistleblowers may not be subject to any civil/criminal responsibility or disciplinary procedures, as guaranteed under Article 9 of the LPW. Article 8 of the LPW provides for the protection of persons related to whistleblowers: they are entitled to the same rights as whistleblowers, including judicial protection. As per Article 24 of the LPW, for cases related to civil servants, the lawsuits shall be filed within the Department for Administrative Issues at the Basic Court in Prishtina.

Some of the most notable differences between the Kosovo whistleblower protection system and its counterpart in South Korea is the physical safety apparatus provided for whistleblowers. While in South Korea, the institutional framework provides for whistleblower protection by police upon request from the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission, in Kosovo, the LPW does not explicitly refer to any police protection. The LPW does reference protection for whistleblowers in terms of the following institutions: the employer (Articles 17 and 22), judicial protection (Articles 24 and 26), and security measures and statements of claim. Another notable difference between Kosovo and South Korea is that the LPW does not provide any form of financial reward for whistleblowers.

The adoption of the LPW was a significant milestone for strengthening the public sector in Kosovo. Yet so far, its implementation has been associated with some challenges. As noted in a report by the Kosovo Law Institute (2020), 23 public institutions have failed to meet legal deadlines to appoint officials responsible for receiving internal disclosures. In March 2020, local media reported allegations that some of the officials were appointed based on political affiliations, questioning their impartiality and independence (Sopi, Reference Sopi2020).Footnote 1

Promulgated in 2018 by the President of the Republic of Kosovo, the LPW’s Article 30, on sub-legal acts, established a deadline of six (6) months for issuing sub-legal acts for the implementation of the LPW, starting from the day of entry into force of the LPW (2018). In 2020, the European Commission emphasized the need for Kosovan authorities to adopt secondary legislation for handling whistleblowing cases, as per the legal deadlines set by the LPW (European Commission, 2020). In 2021, the Government of the Republic of Kosovo approved Regulation No.03/2021 on Procedures for Receiving and Handling the Cases of Whistleblowing.

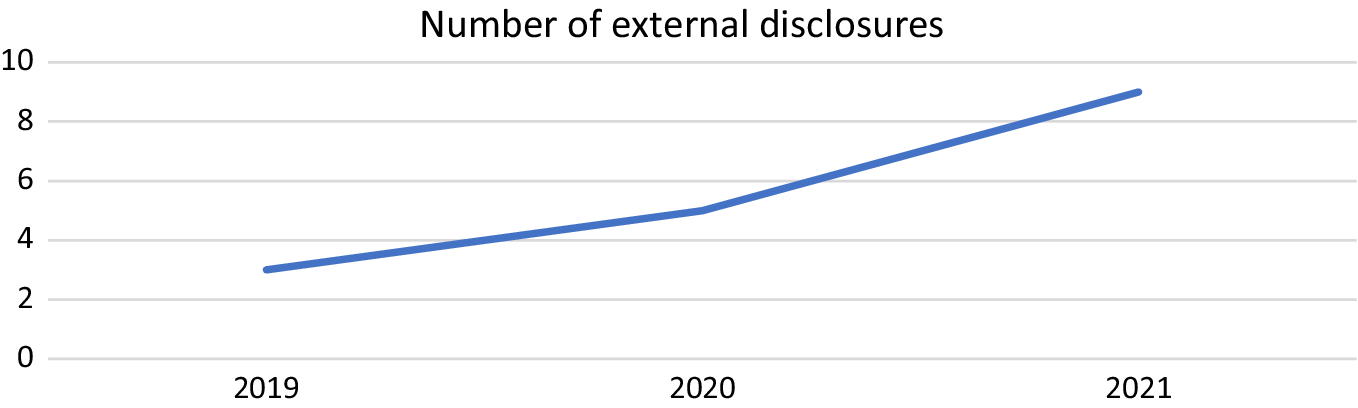

Figures 2 and 3 contain data on external and internal whistleblowing cases in the public sector of the Republic of Kosovo, obtained from the annual reports of the Kosovo Anti-Corruption Agency (KACA) for the years 2019, 2020, and 2021. The data indicate a rising trend of external disclosures and a declining number of internal disclosures for the year 2021. KACA’s data for the year 2022 for both internal and external whistleblowing cases are scheduled for release in March 2023.

A survey conducted from September to November 2019 sought to measure the perceptions of individual members of the civil service of Kosovo on several indicators related to whistleblowing procedures. A sample of 400 respondents was determined to represent all categories of civil service at the local and central levels of public administration, reflecting the scope of Kosovan legislation on civil service. The survey is an output of the doctoral research of one of the authors of this article (Kaciku Baljija, Reference Kaçiku Baljija2020). The data were originally gathered as part of Kaçiku Baljija (Reference Kaçiku Baljija2020)’s doctoral research, then later published in a journal article (Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi, Reference Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi2021).

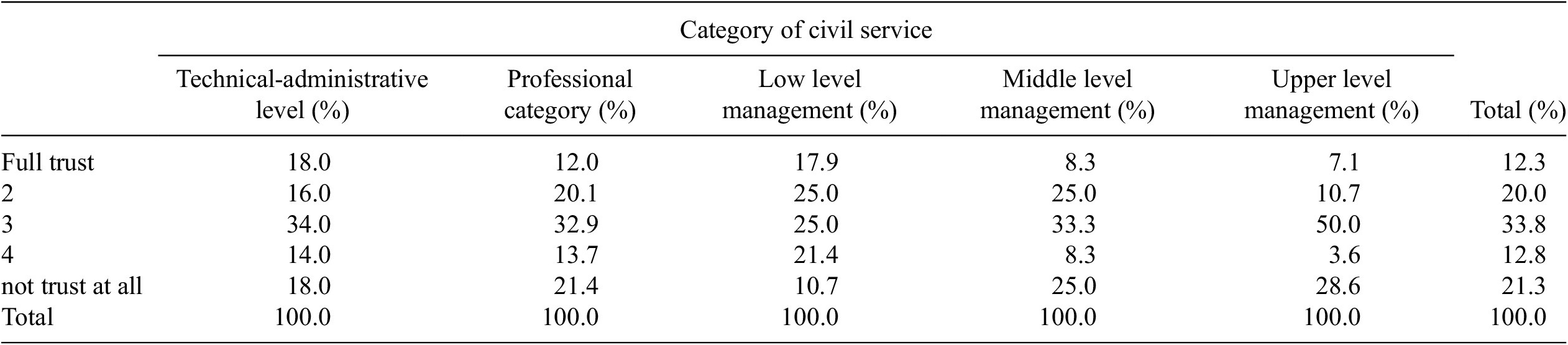

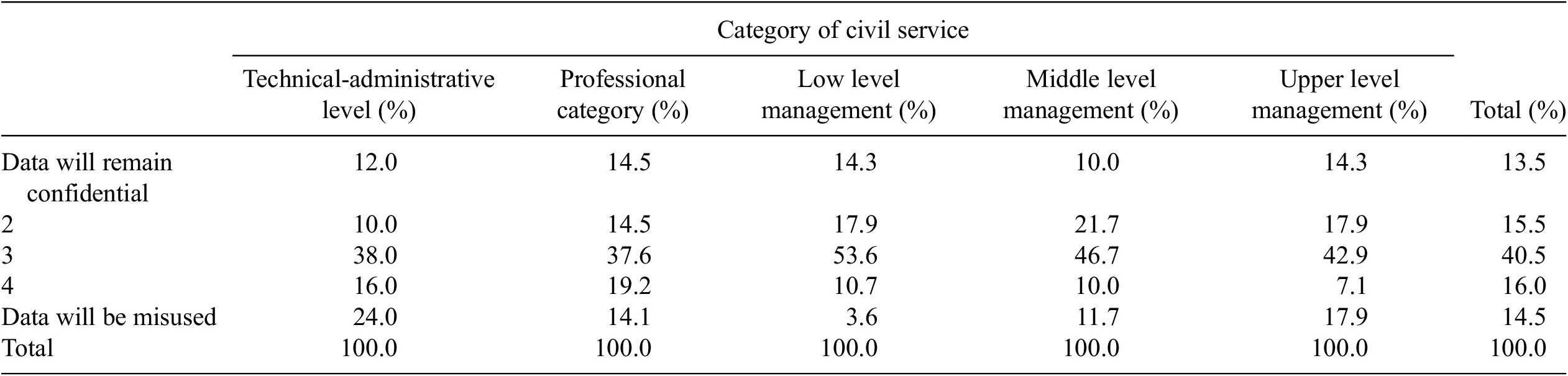

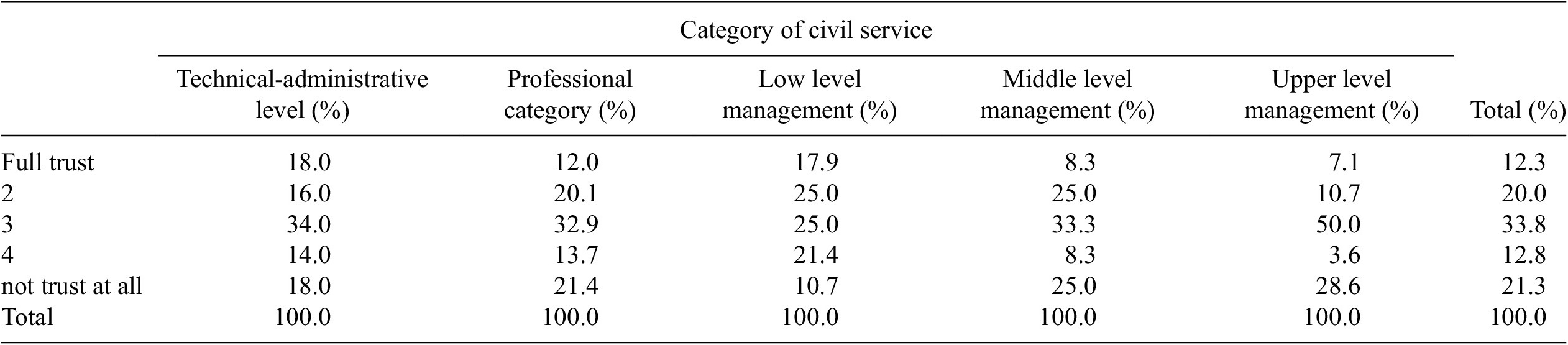

Data presented in Table 4 reveal a considerable lack of trust among respondents in the protection offered by the LPW. “Respondents express a considerable degree of uncertainty about the trust in the responsible official, and above 40% of respondents are not sure how the data confidentiality and anonymity will be ensured, while 30% of respondents believe that such data will be misused” (Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi, Reference Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi2021, p.152).

Table 4. Measuring levels of trust in the protection offered by the LPW

Source: Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi (Reference Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi2021).

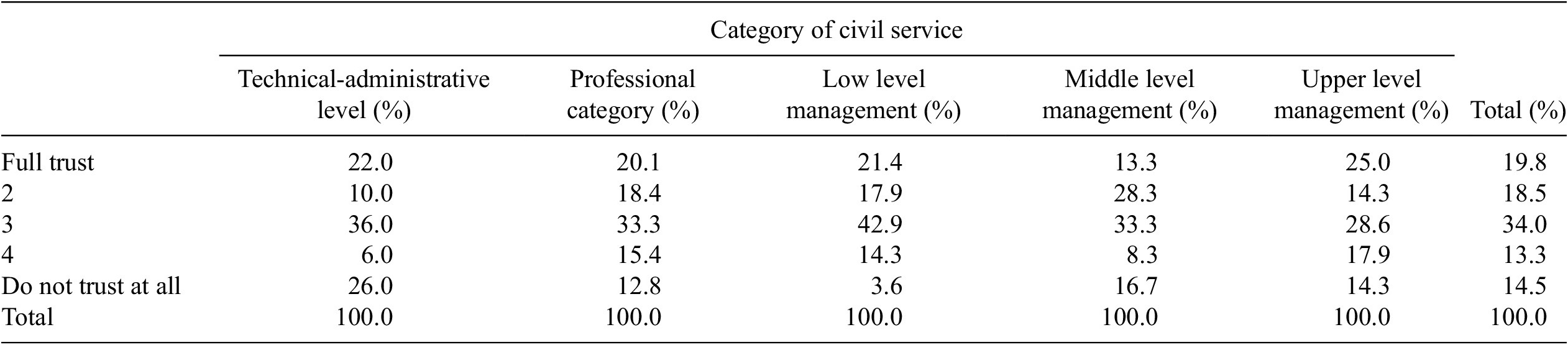

Survey findings reveal that even though the LPW substantially complies with the EU Directive, civil service members do not express satisfactory trust in whistleblowing organizational indicators. Moreover, data from the Kosovo Anti-Corruption Agency shows that since the adoption of the LPW in 2018, there were only a few cases of internal and external whistleblowing disclosures in the public sector (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5. Measuring levels of trust in the officials responsible for receiving whistleblowing reports

Source: Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi (Reference Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi2021).

Table 6. Measuring levels of trust in whistleblowers’ anonymity and confidentiality

Source: Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi (Reference Kaçiku Baljija and Rustemi2021).

Analyzing the establishment of the whistleblower protection system in Kosovo and the implementation of the legislation, the following inferences follow:

-

1. Adoption of legislation aligned with best practices of whistleblower protection is a significant accomplishment for any country. Yet, effective protection requires timely implementation of all inherent components of the relevant laws, including the timely adoption of accompanying secondary legislation and establishing the required mechanisms promptly, e.g., recruitment of the officials responsible for receiving internal whistleblowing disclosures.

-

2. Ensuring the principle of impartiality when recruiting or appointing internal mechanisms for receiving disclosures must go beyond the affirmative spirit envisioned in legislation, and an empowered civil society and media fill in the gaps for democratic requisites.

-

3. Given the sensitive nature of whistleblowing as an activity, maintaining an ongoing dialogue with various actors like public officials, citizens, media, experts, academia, businesses, etc., will clarify weaknesses and opportunities concerning the functioning of whistleblower protection systems. Surveys present a relevant tool for maintaining such communication. Conducting standardized surveys across countries would stregthen our collective knowledge about advancing and optimizing whistleblower protection laws and institutions, particularly by exchanging experiences, practices, and lessons learned.

-

4. Institutional capacities of the public sector,across countries,need to be strengthened for establishing, storing, maintaining, and sharing administrative data related to the functioning of whistleblower protection systems. In many countries, data are either scarce or missing about the rates of the protection provided to whistleblowers via various institutional structures, be they courts, employers, agencies, or police forces.

4. New Index for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Whistleblower Protection

This paper sought to evaluate public sector whistleblowing policies in two countries: South Korea and the Republic of Kosovo. First, the case study about Korea reviewed the effectiveness of whistleblower protection. We discussed the history of institutions established to protect whistleblowers, including the ACRC, which was established in 2008 as the successor to the KICAC. The ACRC has implemented various anti-corruption policies and measures, including the Protection of Public Interest Whistleblowers Act, legislated in 2011, and the Improper Solicitation and Graft Act, established in 2015. The ACRC is responsible for handling complaints and corruption cases and implementing anti-corruption policies, and it has the authority to recommend that public organizations improve their institutional weaknesses against corruption. The case study also covered the provisions of the Act on the Prevention of Corruption and the Protection of Public Interest Whistleblowers Act, which outline the protections and rewards available to whistleblowers in South Korea. The case study concluded by discussing the challenges and limitations of whistleblower protection in South Korea, including the lack of awareness of the protection measures among the public, the low number of successful cases, and the need for stronger institutional support and enforcement mechanisms.

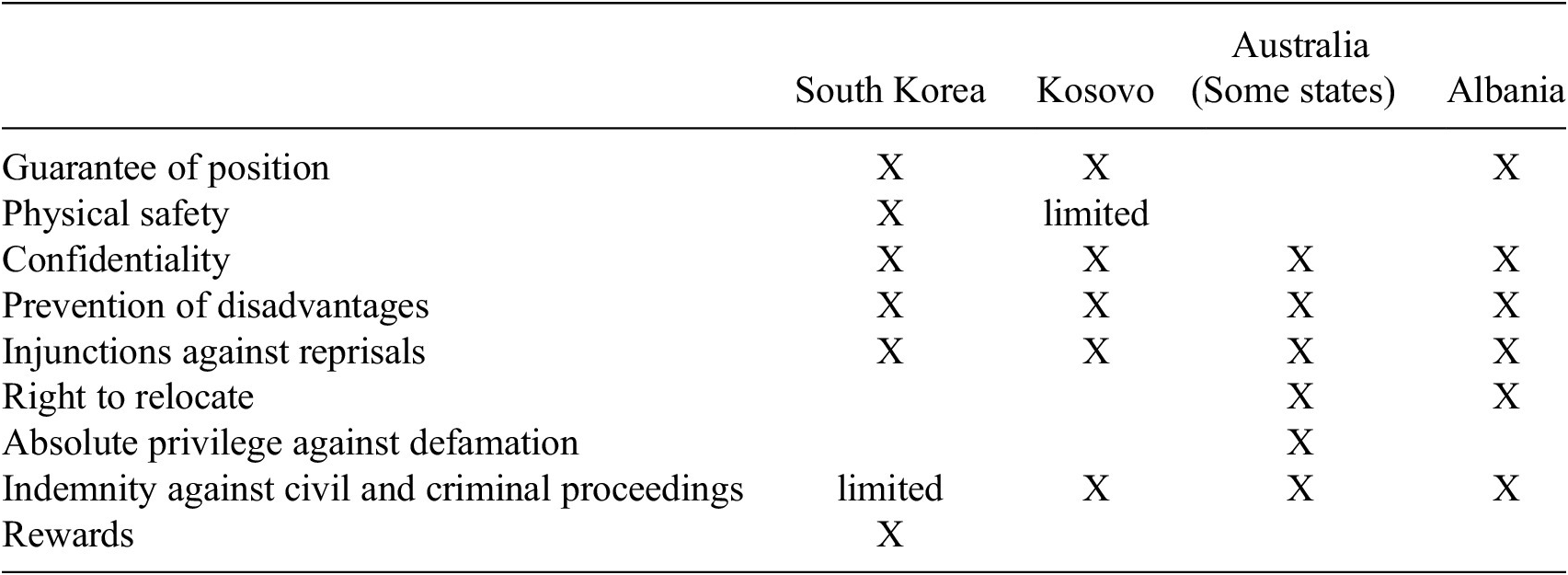

Second, this paper assessed the whistleblower protection systems in place in the Republic of Kosovo. The analysis looked at the history of institutions, relevant policies, and current institutions responsible for providing protection. Survey data showed how public officials perceive various organizational factors like the protection guaranteed by legislation, confidentiality, and trust in the officials responsible for receiving disclosures. Conclusions suggested that, aside from the importance of enacting high-quality laws, additional measures count for strengthening the whistleblower protection system in the public sector. Timely implementation of legislation, impartiality when appointing institutional mechanisms and officials for protecting whistleblowers, and greater transparency through providing data from institutions in different parts of the system, among other factors, determine the quality of and public trust in the Kosovan whistleblower protection system. Table 7 summarizes measures for protecting whistleblowers in several countries. The benefits of whistleblower-related institutions include the guarantee of position, physical safety, and other measures. Some of these measures have already been adopted in South Korea, while others are already implemented in other developed countries, e.g., Australia. In developing countries like Kosovo and Albania, some of these measures are not yet enshrined in legislation, particularly financial rewards for whistleblowers.

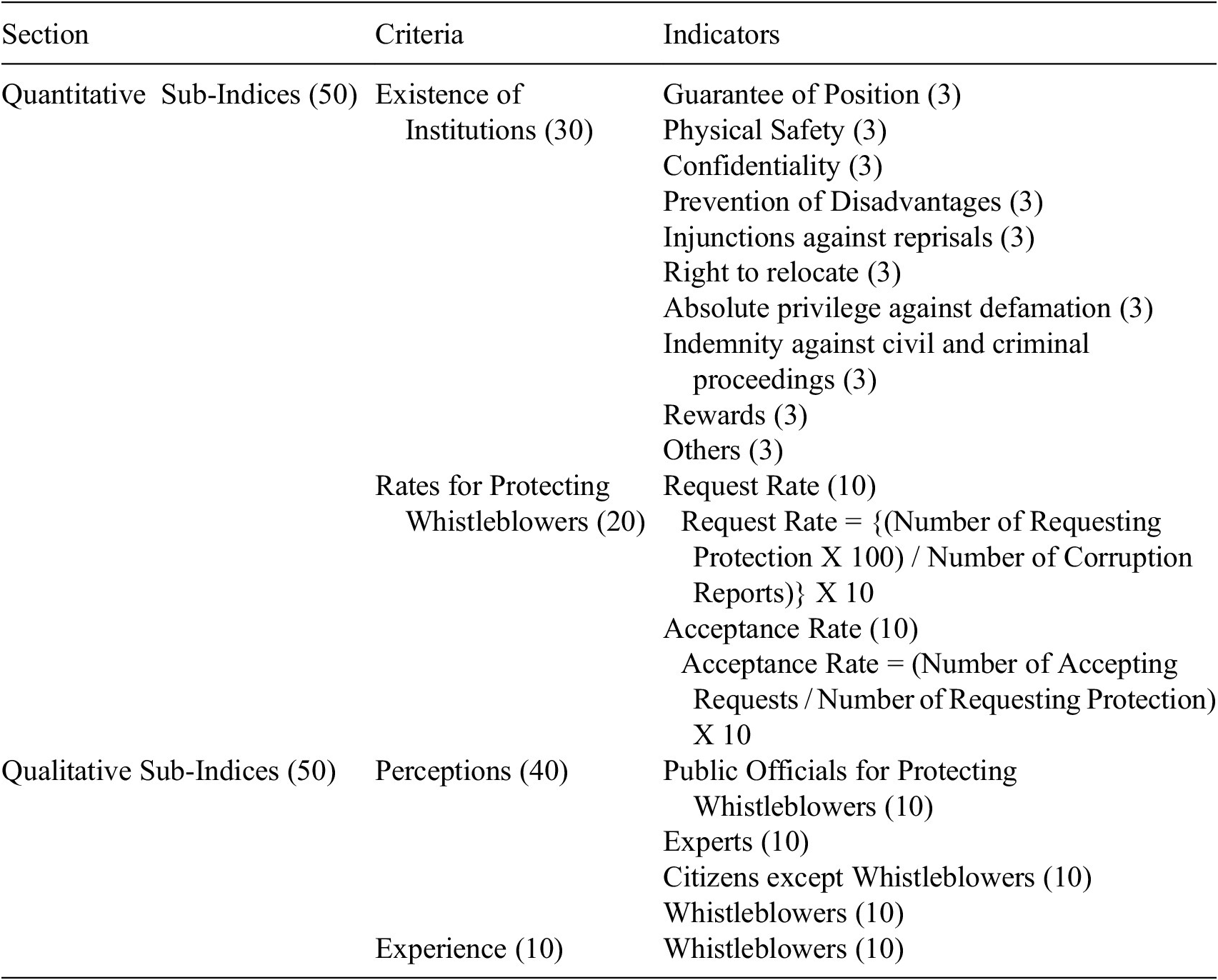

Based on the case studies, we now present an index for evaluating the effectiveness of whistleblower protection in the public sector. As noted earlier, we call this tool the Index for Evaluation of Whistleblower Protection, or IEWP. The IEWP has quantitative and qualitative sub-indices. The quantitative sub-indices can be divided into two types: the existence of institutions and the rate for protecting whistleblowers. The qualitative indices include the perceptions and experiences of respondents. Table 8 summarizes the composition of the IEWP.

Table 8. Composition of the Index for Measuring the Effectiveness of Whistleblower Protection in the Public Sector (IEWP)

Note. The points in parenthesis are weights.

The existence of institutions has ten indicators: the guarantee of position, physical safety, confidentiality, the prevention of disadvantages, injunctions against reprisals, the right to relocate, the absolute privilege against defamation, indemnity against civil and criminal proceedings, rewards, and miscellaneous measures.

A guarantee of position means that whistleblowers should be guaranteed to keep their position in their workplace after whistleblowing. Physical safety indicates that whistleblowers should be protected from physical retaliation. Confidentiality ensures whistleblowers’ personal information is not disclosed without their consent. The prevention of disadvantages protects whistleblowers from personal and professional disadvantages resulting from their actions. This category includes not only job security but also protection against harassment and discrimination. An injunction against reprisal is a court order that requires an employer or other individuals to stop any legal actions that could harm the whistleblowers. The right to relocate allows whistleblowers to move to a safe place without worrying about the costs of relocation, if they justifiably fear for their safety. Absolute privilege against defamation means whistleblowers cannot be sued for defamation, even if the information that the whistleblowers provide is not true, as long as they believed the information was true and provided the information in good faith. Indemnity against civil and criminal proceeding ensures that whistleblowers are not held liable for legal actions resulting from their whistleblowing. Rewards are monetary incentives provided to whistleblowers. Remaining measures that do not fit into any of these categories are placed in the miscellaneous category.

Each indicator is worth three points; the value can be zero or one. For example, if the government provides physical safety for whistleblowers, then the value of the indicator for physical safety will be one, and the index score will increase by three points. If the government does not provide whistleblowers with rewards, then the indicator value for rewards will be zero, and the points will also be zero. If a whistleblower protection law has three measures on the list, then it will earn nine points.

The rate for protecting whistleblowers has two indicators: protection request rate and protection acceptance rate. The request rate can be calculated using the number of protection requests and the number of corruption reports. First, we multiply the number of protection requests by 100. Second, we divide it by the number of corruption reports. Finally, we multiply the value by 10. We multiply the number of requests by 100 for several reasons. First, it is natural that all corruption cases need protection. Thus, some reporters do not want to request protection. Second, it is plausible that some corruption cases are false reports. Accordingly, it is not a good idea to protect all corruption reporters by default. Finally, we want to balance the impacts of the request rate and acceptance rate. Multiplying the number of requests by 100 helps us mitigate the large impact of the request rate.

The maximum point value is ten. If the request rate is high, then the number of whistleblowers requesting protection is relatively larger, and the number of corruption reports is relatively smaller. If the request rate is high, we can assume that many reporters have requested protection. This might mean that the reporters highly evaluate the effectiveness of measures for protecting whistleblowers.

The request rate as an indicator, however, has a pitfall. If the number of corruption reports is relatively small because of a lack of trust in the government, then the request rate can be high. In other words, the number of corruption reports might be relatively small when people do not trust their government. In this case, although corruption is rampant in the government, people do not report corruption. Thus, the request rate might fail to reflect the effectiveness of measures for protecting whistleblowers.

For this reason, the index includes the acceptance rate. The acceptance rate can be calculated based on the number of accepted protection requests and the number of issued protection requests. First, we divide the number of accepted requests by the number of overall requests. Second, we multiply the value by ten. The maximum point value is ten. If all the protection requests are accepted, then the number will be one. In this case, the acceptance rate will be ten because the figure will be multiplied by ten. If the acceptance rate is high, then the number of accepted requests is relatively larger, and the number of requests is relatively smaller. If the acceptance rate is high, we can assume that a large number of requests were accepted. This might mean that measures for protecting whistleblowers are widely used.

The acceptance rate as an indicator, however, also has a pitfall. If the number of protection requests is relatively small because of a lack of government trust, then the acceptance rate can be high. In other words, the number of requests might be relatively small when whistleblowers do not trust their government. In this case, whistleblowers will not request protection. Thus, the acceptance rate might fail to reflect the effectiveness of measures for protecting whistleblowers. For this reason, the index adopts both the request rate and acceptance rate.

Quantitative sub-indices are not enough to evaluate the effectiveness of measures for protecting whistleblowers. For example, enacting a whistleblower protection law, including various protection measures, does not guarantee the effectiveness of the measures because the law might not properly work. The request rate and acceptance rates might fail to capture the level of effectiveness of the measures when the level of trust in the government is low. Although request and acceptance rates may be high, whistleblowers might not be properly protected due to the government’s inability to protect them. To overcome these pitfalls, this study suggests qualitative subindices that include the perceptions and experiences of respondents.

To measure perceptions, this index asks questions to four types of respondents: public officials, experts, citizens who have no experience in whistleblowing, and whistleblowers. It is plausible that different types of respondents might have different perceptions of the effectiveness of their present whistleblowing protection institutions. For example, while public officials may think that the present system is good enough to protect whistleblowers, whistleblowers may feel that the system fails to protect them. While experts, such as scholars and lawyers, may deeply understand the advantages and disadvantages of the present system, non-whistleblower citizens may not be interested in the system. Thus, it is important to survey different types of respondents. Ten points are allocated to each respondent cohort. Likert-type scales could be used with questions like “How effective do you think the whistleblower protection law is?” The survey should include various questions that measure respondents’ perceptions related to whistleblower protection measures. In each cohort, the summation of the results can be rescaled from zero to ten.

Since perception might be different from experience, this index also measures experience. Since perception might be different from experience, this index also measures experience. In this case, only whistleblowers are surveyed, again with ten points allocated to the cohort. A sample question might be, “Have you been properly protected when you request protection for whistleblowing?” Other questions should measure the experience of respondents related to specific whistleblower protection measures. The summation of the results can be rescaled from zero to ten.

Assumptions:

-

1. Establishing the IEWP as a universal measure relies on the availability of data. This paper calls for the development of new data sources based on standard methodologies across countries.

-

2. Some countries lack publicly available data on protection request and acceptance rates for courts and other relevant authorities.

-

3. Some countries lack data on public officials’ perceptions.

-

4. The survey components will generate new findings on trends in perceptions, as well as on the functioning of a given system.

4.1 Toward operationalization: Methods, data sources, and tools

As a cross-national benchmarking platform, the IEWP provides a measurement framework to support and inform anticorruption objectives at national level in different countries. As a composite measure, the IEWP embraces a methodology consisting of two pillars of research: combining existing administrative data from the public sector with survey data. As such, it requires producing and locating data that are not extant, standardized, or accessible.

The IEWP is designed as a long-term digital research tool serving a wide range of policymakers and stakeholders. Administrative data and surveys at the national level should capture the state of indicators on an annual basis.

4.2 Data collection strategies

Sub-indices and indicators draw on internationally agreed definitions of principles and legislation for whistleblower protection. The IEWP draws on some of the Transparency International (2013) principles like confidentiality, reward systems and protection, among others, to combine with survey data tracking relevant respondents’ perceptions.

Data collection strategies for the compilation of the index will entail extracting existing administrative data from public sector institutions in the country of interest, as well as the creation of new data sources for surveys. Surveys will measure perceptions of actors like actual and potential whistleblowers, public officials, citizens, civil society, and experts.

Besides ensuring representative sampling, the survey should account for multilingual populations in a given country. Research for compiling the IEWP’s annual report, including drafting the questionnaire and data analyses/interpretation, should be conducted by field professionals and scholars.

Outsourcing data collection, storage, and visualization may be an option. Data management should follow existing best practices of research, such as the FAIR principles—findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable—and take into consideration the highest respect for human rights, equity, and gender criteria. Data collection processes must adhere to data privacy and protection legal framework in the host country.

4.3 Hosting platform

The IEWP may be hosted on an open-format internet platform, enabling data visualization on a cluster, national, and regional basis, by embracing big data and data-driven approaches. Data-driven approaches have been evaluated as relevant to support the prediction of policy outcomes for improved decision-making (The United Nations Development Programme, 2021). As the IEWP implementation may commence gradually from country to country, findings from monitoring and evaluation shall inform later insights for change, adaptation, and experimentation.

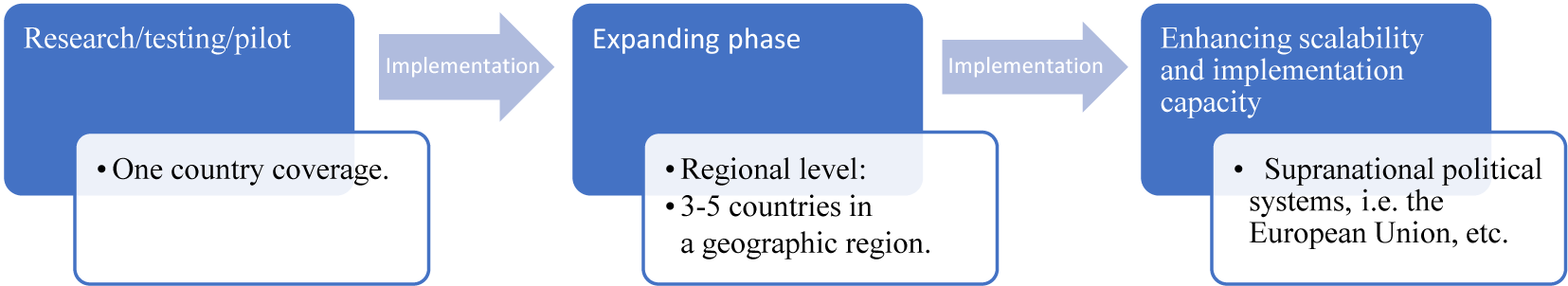

4.4 From country to global coverage

A standardized methodology should follow the compilation of the IEWP indexes in each country. Extending the IEWP from single-country to global coverage will require a three-step approach: 1) starting small-scale in one country, 2) extending gradually to two or three other countries in the region, and 3) extending further based on supra-national political systems. For instance, the implementation may commence in the Republic of Kosovo, with further expansion via horizontal scalability into the Republic of Albania, the Republic of North Macedonia, the Republic of Montenegro, and the Republic of Serbia, thus ensuring complete coverage of the region of the Western Balkans. The index can also be implemented at the level of the European Union member states, and so on in other regions, eventually getting as close to global coverage as possible.

4.5 Partnerships and outputs

IEWP implementation will require stakeholder engagement, public engagement to track perceived value, monitoring and evaluation, resource mobilization, communication/dissemination of findings, follow-up, and workshops, among other tasks. Consequently, research and data collection may produce and locate big data analytics, standardized scientific data pools, container technology, etc.

4.6 Justification of the index

The IEWP adds value to prior research on whistleblowing by providing a body of knowledge based on a standardized methodology and outputs for measuring protection effectiveness offered by legislation. Given the proposed mixed methods research methodology and the subjects it encompasses, the IEWP will ensure a dialogue with public officials, civil society, citizens, academia, business, etc., to generate insights and data that may be otherwise limited or even unavailable to the public. The benefits of findings generated by the IEWP are multi-faceted: knowledge obtained from countries with long experience in implementing whistleblowing laws, for example, may serve to help countries less experienced in implementing whistleblower protection laws.

The IEWP lays the ground for further development of the line of research on whistleblower protection in three main directions:

-

1. Exploring and advancing the legalities of whistleblower protections concerning the development and expansion of digital rights.

-

2. Nurturing information around the regulation of privacy approaches, depending on the country and legislation.

-

3. Examining gendered perspectives of whistleblowing and providing directions for inclusive frameworks.

4.7 Ownership and funding

Certain requirements for an organization eligible to implement the IEWP may include the following: 1) operating in a specific country (or transnationally) or region, 2) possessing know-how and expertise for implementing such projects, 3) possessing resources for outsourcing data collection or fundraising capacities and 4) possessing the capacity for public engagement.

(Figure 4).

Figure 4. From inception to increased scalability.

4.8 Avenues for future research

The IEWP lays the groundwork for further development of research on whistleblower protection in three main directions:

-

1) Exploring and advancing the legalities of whistleblower protections concerning the development and expansion of digital rights.

-

2) Nurturing information around the regulation of privacy approaches, depending on the country and legislation.

-

3) Examining gendered perspectives on whistleblowing and providing direction for inclusive frameworks.

-

4) Bringing to light variations in whistleblowing experience from different perspectives: public vs. private sectors, big tech vs. users, etc.

5. Conclusions

This paper clarified the relevance of a whistleblower protection system for the public sector. It first summarized recent milestones related to the development of policies for whistleblower protection in the public sector in the EU and some other countries. Next, drawing on two case studies, South Korea and the Republic of Kosovo, this paper sought to examine whistleblowing policies in the public sector. We highlighted some of the differences in whistleblower protection systems in these two countries. South Korea established anti-corruption institutions and policies a long time before the Republic of Kosovo, which only recently enacted a law protecting whistleblowers in the public sector standing in satisfactory compliance with the best principles of whistleblower protection. Next, we used findings from these two case studies to construct a new index for measuring the effectiveness of whistleblower protection systems in the public sector. The index is composed of quantitative and qualitative sub-indices that assess the existence of institutions, rates for protecting whistleblowers, perceptions of public officials and citizens, as well as experiences and perceptions of whistleblowers on several whistleblowing indicators.

Considering the research questions guiding this study, the findings demonstrate that besides the importance of enacting high-quality legislation on whistleblower protection, effective additional measures include timely implementation of legislation, impartiality when appointing institutional mechanisms and officials for protecting whistleblowers, and greater transparency in the form of providing data from different institutions. These factors, among others, determine the quality of public trust in a whistleblower protection system in the public sector.In closing, we propose that the IEWP, as a composite measure, effectively embraces a methodology consisting of two pillars of research, combining existing administrative data (or creating that data) from the public sector with survey data on perceptions of whistleblowing. To implement the IEWP, we suggest improving data that are not existent, standardized, or accessible to identify potential improvements in whistleblower protection systems in different countries. Although we have constructed the IEWP building based on public sector research, with minor adjustments, the IEWP may also track and evaluate whistleblowing in private and not-for-profit sectors, effectively covering all forms of corruption and institutional wrongdoing.

Funding statement

The authors declare not having acquired any source of funding for this article.

Competing interest

S.K.B. declares none. K-s.M. was a senior deputy director at the Anti-Corruption & Civil Rights Commission of South Korea that generated datasets that deal with whistleblower protection in South Korea.

Author contribution

The authors have provided equal contributions in conceptualization, data curation, formal analyses, methodology, and writing of this manuscript.

Data availability statement

For the South Korea case study, the authors have used a dataset produced by the Anti-Corruption & Civil Rights Commission of South Korea. This dataset is not publicly accessible. For the Republic of Kosovo, the authors use a survey dataset, accessible in the following article https://doi.org/10.2478/nispa-2021-0018. Additional demographics of this dataset are accessible at the repository https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Survey__demographic_details_of_respondents/13139054.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.