During a few “leisure evenings in the Spring of 1812,” Samuel Woodworth wrote a poem decrying “griping landlords, despots of an hour” who growl “my money or your goods.” The poem’s climax features a pair of young newlyweds who are made destitute by the costs of illness, who have had to pawn their “few utensils of domestic use” to get by. With no money left to pay their rent, the landlord arrives to seize their last remaining possession, the couch upon which the young wife lay dying. “Your bed is mine!” the landlord shouts, calling a marshal into the room. They move her “ungently” onto the “cheerless floor,” secure the couch, and watch her die, as they carry the furniture off to a sheriff’s sale. Woodworth begged compassion for “the wretch unfortunate” who has been “by landlord stripp’d of all the goods domestic wants require.” The poem, “Quarter-Day – or the Horrors of the First of May,” lambasts a particular breed of wealthy, propertied landlord for whom an individual rent payment was a drop in the ocean, taking aim at the practice described above, distraint for rent.Footnote 1

Woodworth’s characters may be presented romantically, but they represent more than just a poet’s fancy. Reviews asserted that Woodworth’s depiction of poor tenants and rapacious landlords was “founded…in fact,” describing the poem as a “pill for landlords.” Another reviewer claimed that Woodworth’s poem was “a libelous attack upon landlords,” who merely “resort…of course, to this law” to claim “what is fairly due to [them].” “If the law be bad,” the writer argued, then the law “should be censured, and not the landlord.” It was necessary, however, they argued, because, “severe as it may seem, it is scarce sufficient to secure the punctuality of tenants, so averse are they to the payment of rents, and we should only be surprised at the lenity of landlords, and the few instances of their cruelty.”Footnote 2

In the early national period, if rent was not paid on time, a landlord was entitled to “distrain” or “distress” a tenant who was in arrears—to seize the tenants’ belongings and sell them to offset the unpaid rent, as Woodworth described in the poem above. The practice, which evolved from English common law, was instituted in the colonies, and remained a legal “remedy” used by property owners despite periodic opposition and limitations, including the 1846 abolition of the practice in New York State.Footnote 3 A 1788 law governing distress stipulated that “all distresses…shall be reasonable, and not too great.” But evidently many were, and the practice became a major target for reform in the 1810s.Footnote 4 Even the New York City Common Council seemed somewhat incredulous as to the extent of the privileges landlords were afforded. In August 1811, a tenant named John Downing asked the Common Council to remit and discharge his rent because he did not have “any property, except a little furniture.” The council’s Committee of Charity investigated his circumstances and found that there would be “no way to get the rent due from the petitioner but distress and sale of said furniture, which they think would be distressing the distressed.”Footnote 5 But landlords did distress the distressed, daily, calling on the labor of the marshals, constables, and sheriffs in their city to carry out the procedure. In instances such as this, poor tenants and council members alike seemed to be registering their sense that the law sometimes needed to be bent to the people’s own vision of justice.

Distress for rent was also practiced in Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey, and beyond during this period. But because New York landlords enjoyed unparalleled privileges and the state contained one of the largest populations of renters in the young United States, its evolution in New York affords unique perspectives on the practice’s legal history and how people experienced it.Footnote 6 While under common law and most state legislation, creditors’ officers were limited to seizing goods held in open, accessible spaces, New York landlords were authorized to “break open such house, or any enclosed place, and to seize…goods as a distress.” This applied not just to the property on which rent was owed, but to “any house, outhouse, or other place” where goods might be hidden “for the purpose of preventing their being seized as a distress for rent.” The US historiography of distraint has mostly presented the practice as an archaic holdover from outdated British common law which clashed with the realities of the nascent capitalist American society during the 1840s “anti-rent wars,” a tenant rebellion against landlord power and feudal style property management.Footnote 7 According to Reeve Huston, wealthier landlords were unlikely to distrain tenants for rent arrears unless they really needed the income, citing the example of “Isaac Hardenbergh, a Delaware County proprietor” who “conducted distress sales…against a few heavily indebted tenants,” while “great and middling landowners” generally “turned to such drastic measures only in the case of rebellion or outright refusal to pay.”Footnote 8

In the 1820s–40s, legal, rhetorical, and literal battles over the terms of rent, land ownership, leases, and distraint roiled in upstate New York. As Elizabeth Blackmar argued in Manhattan for Rent, “during the first third of 19th century, New York judges and legal commentators repeatedly defended landlords’ powers as ‘reasonable and necessary.’” But many rural and urban New Yorkers, viewed the “remedy of distress for rent [as] one of the most severe and may be the instrument of more oppression than any other proceeding,” as one state lawmaker wrote in 1828.Footnote 9 The legislature received petitions for relief from “landlords’ power to seize their property” from tenants in New York City and across the state “who stood in very different positions with respect to their control and use of real property.” By the 1840s, Blackmar argues, these tenants had formed a de facto “coalition that challenged landlords’ power to encroach on their livelihood” and “household necessities.” The forerunner of this coalition can be found a generation earlier, as New Yorkers used petitions, editorials, mutual aid, philanthropy, and policy proposals to challenge landlords’ privileges and protect the subsistence of tenants, especially of poor workers. This article explores the community organizing, resistance, and lobbying efforts in which New York City residents engaged in the 1810s, decades before the “rent wars” challenged landlord’s privileges directly.Footnote 10

As Woodworth’s poem and responses to it suggest, rent distraint was a practice and topic around which ideological and practical conceptions of class, the rights of property, the role of law, and welfare were contested in early Republic New York. In 1811, the year before “Quarter Day” was written, New York City officials began tracking tenants in arrears of rent, creating a deep archive of documents that reveal the nuances of landlord-tenant relations and subsistence in this period. This article follows that paper trail, exploring distraint in this context as a legal remedy, as an experience with major impacts on individuals’ lives, and of efforts to reform the law and the lived experience of law.Footnote 11

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, poor, middling, and wealthy New Yorkers were engaged in knowledge exchange around distraint and the social categories and experiences associated with it. Their stories document a materialist sensibility that crossed class lines and was attuned to the practical dimensions of working people’s living conditions. Poor women explained to the philanthropists who visited them regularly how they calculated strategically partial rent payments, the cooking utensils they could do without, furniture they could pawn or sell, or collaborated with neighbors to hide the goods a landlord might seize.Footnote 12 Workers shared information with philanthropists and local public officials about their experiences with landlords, and the hurdles they faced in trying to pay rent, remain independent, and keep their families afloat. Reformers shared information across the memberships of charitable societies and organized petitions to local officials and state legislators, lobbying for amendments to laws that would improve poor people’s ability to maintain themselves. Local government officials ranging from assistant justices of the peace to marshals and sheriffs were tasked with mediating tenants’ and landlords’ understandings of the law and their rights. Together, these actors tinkered with ways to codify and enshrine early national sociocultural expectations around property, poverty, and civic responsibility. In debating the role of the law in ensuring the subsistence of residents living within its purview, they constructed a vision of early American jurisprudence that mediated and checked the negative impacts of laws that helped some and hurt others, managing and mitigating the uglier angels of human nature. When individuals could not provide for themselves and private aid was insufficient, early Republic New Yorkers turned to the government and its officers to argue for systemic change—sometimes to improve what they saw as unjust laws and their unfeeling implementation, and sometimes in the hopes that it would protect what meager tools of subsistence were available to them.Footnote 13

Distraint in Practice

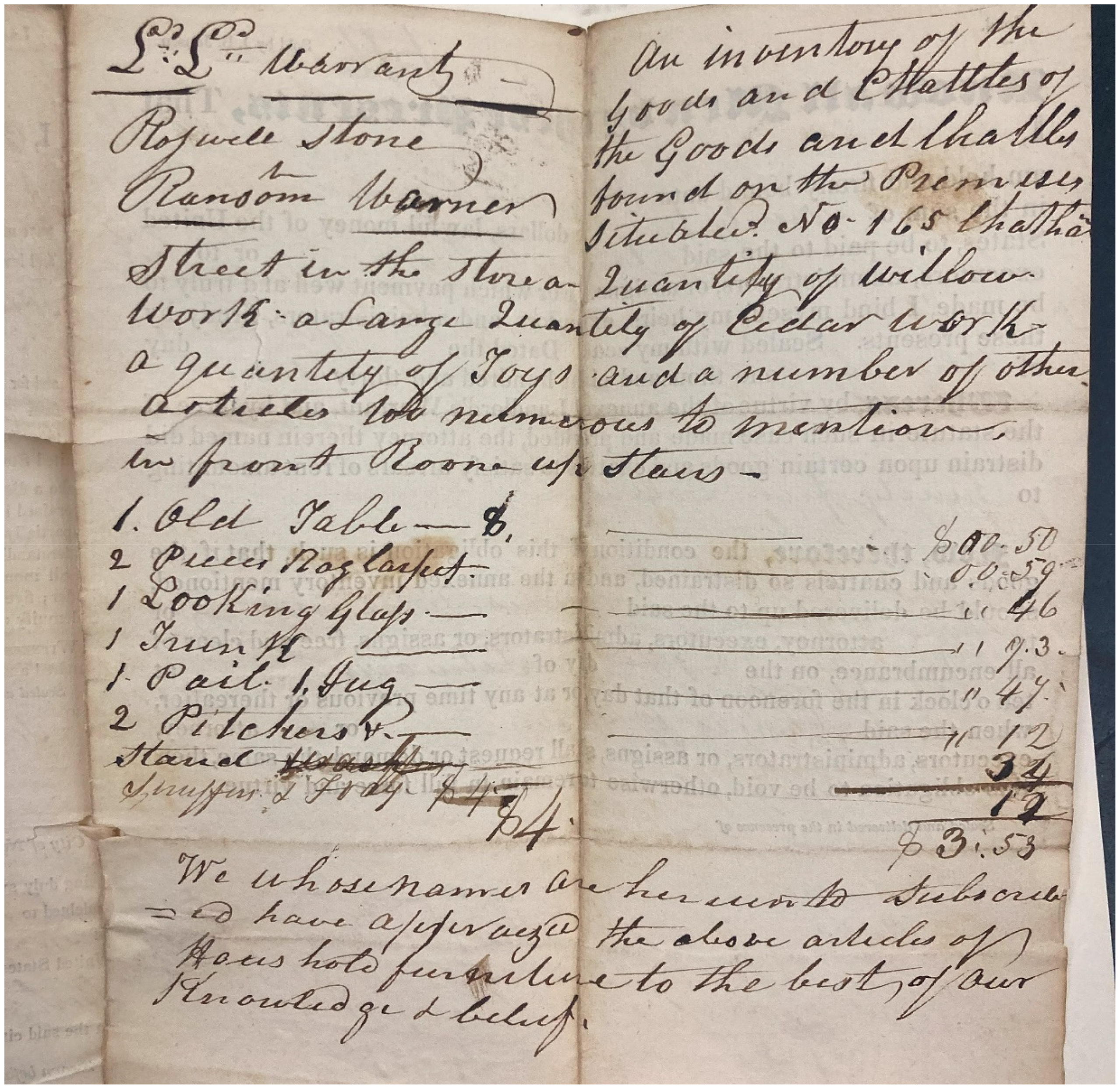

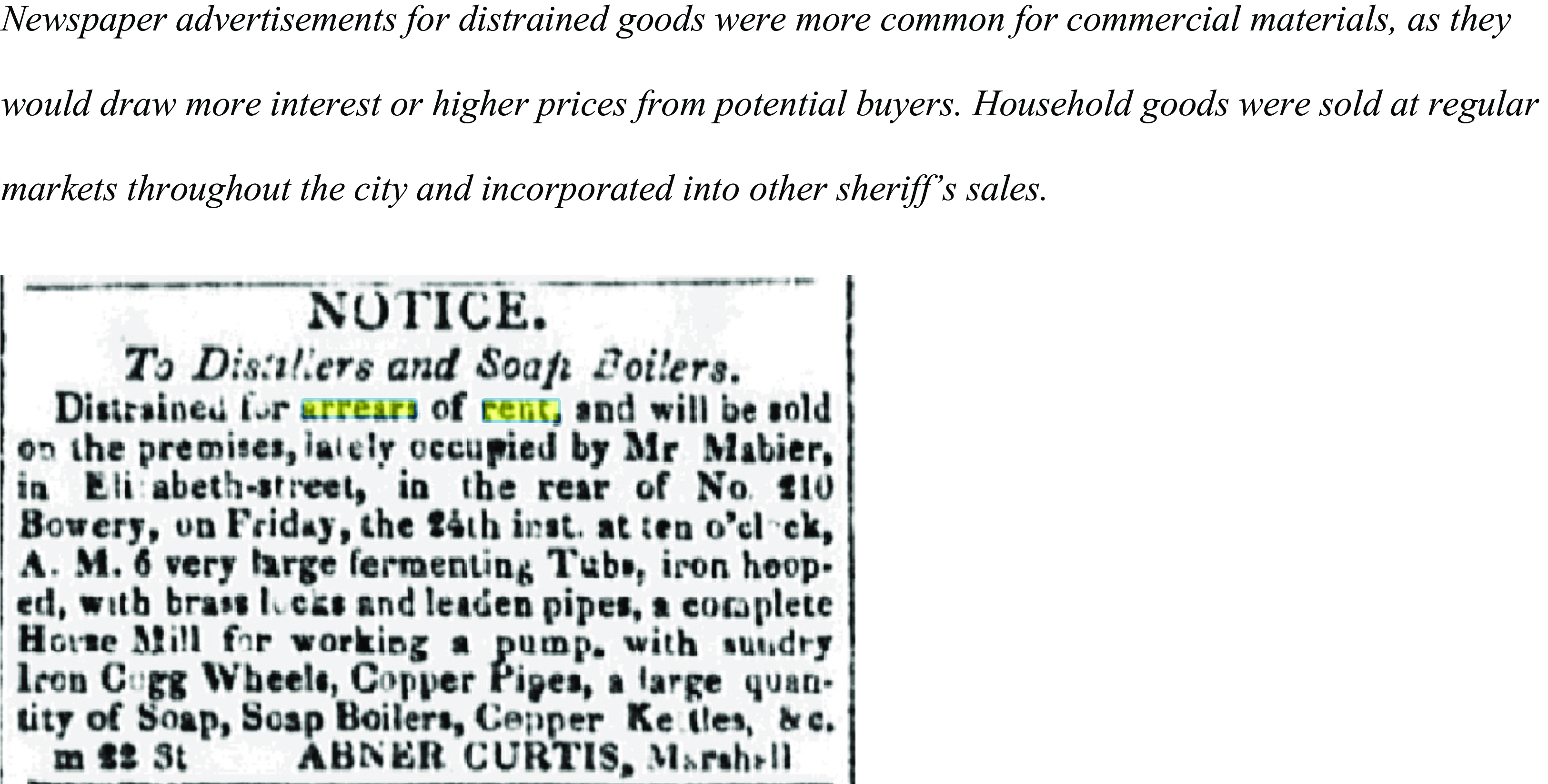

Landlord and tenant law laid out a clear procedure for distraint, which generally worked as follows. After a landlord filed an affidavit, in some cases, they would seek a warrant for distress from the justices of the peace, who would then issue a warrant to a sheriff or constable. In other cases, the affidavit itself was used as a warrant. Either a justice, sheriff, or constable would then, along with “two sworn appraisers,” assess the value of the goods liable for distraint, creative an inventory documenting them, and take them to be stored “off the premises” (Figure 1). They were expected to take only the approximate amount of possessions that they thought could fetch the value of the unpaid rent, plus the fees of the justice, constable, etc., not all movable goods. If, after a set number of days (commonly five), the rent remained unpaid, the goods would be sold at public auction, and the profits used to cover the arrears of rent, plus the officials’ fees for carrying out the distress procedure.Footnote 14 In at least a few cases, tenants with arrears tried to prevent this process from beginning by appealing directly to public or private agencies for assistance, such as the petition described above from John Downing. Auctions of distrained goods were advertised in newspapers (Figure 2) and in announcements pasted onto walls. After the distrained goods were sold, they were absorbed back into the market.Footnote 15

Figure 1. Example of an inventory of goods to be distrained for rent, circa 1832. Division of Old Records, Mayor’s Court of New York.

Figure 2. Example of a notice of sale of distrained goods, New York Gazette, May 22, 1811.

Of course, many tenants were aware that if their rent remained unpaid after it was due, the landlord may send someone to seize their goods. In anticipation, some tenants asked neighbors or friends to hold their goods for them to protect their property and livelihoods from landlord interference. Under New York’s 1788 distress law, if a tenant hid any of their property offsite “for the purpose of preventing [it from] being seized as a distress for rent,” the tenant and their accomplice would be legally indebted to the landlord for double the value of the hidden goods. On the other hand, the same was true for landlords who distrained for rent when the tenant was not actually in arrears; double the value distrained, plus fees, was required to be returned to the tenant.Footnote 16 New York landlords could forcibly enter the home of a tenant or one of their suspected collaborators to search for goods to distrain. Tenants had legal recourse to fight illegal or excessive distraint in court and to request replevin of the distrained goods. Generally, as the examples that will follow here illustrate, the legal history of distraint has been attuned to the concept of subsistence, while ensuring the law protected the individual rights of property owners while admitting some element of responsibility for preventing the destitution of renters and people experiencing poverty.

While the cast of characters caught up in distraint and arrears included people up and down the economic strata, public opinion tended toward viewing the landlord-tenant dynamic as one of oppression and exploitation.Footnote 17 One editorialist argued in 1810 that it was “well known to what extremity of wretchedness, whole families are often reduced at inclement seasons, by the indiscriminate seizure of clothes and bedding, to satisfy the landlord for arrears of rent.”Footnote 18 This was a time of dramatically increasing poverty and seasonal unemployment, in which an average journeyman might expect to only find work in his trade about six months in a year.Footnote 19 In the winter of 1808–1809, newspapers reported that the number of outdoor poor was “incalculable,” and they lacked “every necessary of life.” Poor people used the resources around them and within themselves and their communities to scrape by, while limited welfare was only available from municipalities and private organizations during these years. It was well known to be woefully insufficient, even though it was the largest expenditure in the municipal budget, totaling almost a quarter of the city’s total expenses. No matter the public provisions allocated to the poor, or private collections taken up for the needy, it was “not observed that cases of suffering become less frequent,” reformers noted; “on the contrary, new…objects of distress…continually [presented] themselves, which…the contributions of citizens are insufficient to relieve.”Footnote 20

Poverty begets poverty: when a household can barely afford rent, having the goods they scrimped to afford, such as cooking utensils, distrained when they were unable to pay rent could turn a seasonal financial slump into a dire situation from which it might be impossible to get back on track. According to Jeanne Boydston, the households of the working poor often possessed minimal “household furnishings,” perhaps only “a table, a chair, some blankets and rags for mattresses, a cooking pot, and a few utensils.”Footnote 21 When cash was needed, workers would pawn a few belongings for rent or a doctor’s bill. It is easy to see how distress for rent could have left a household with literally no belongings at all. One small mitigating factor that likely kept some households housed during the worst of the winter when they otherwise would have been unable to pay rent was that many rents in the city were paid quarterly, not monthly, so many tenants were only obligated to pay their landlords in February, May, September, and December. If a household could hold onto the autumn’s wages before winter set in, they might be able to keep a roof over their heads into the New Year.Footnote 22

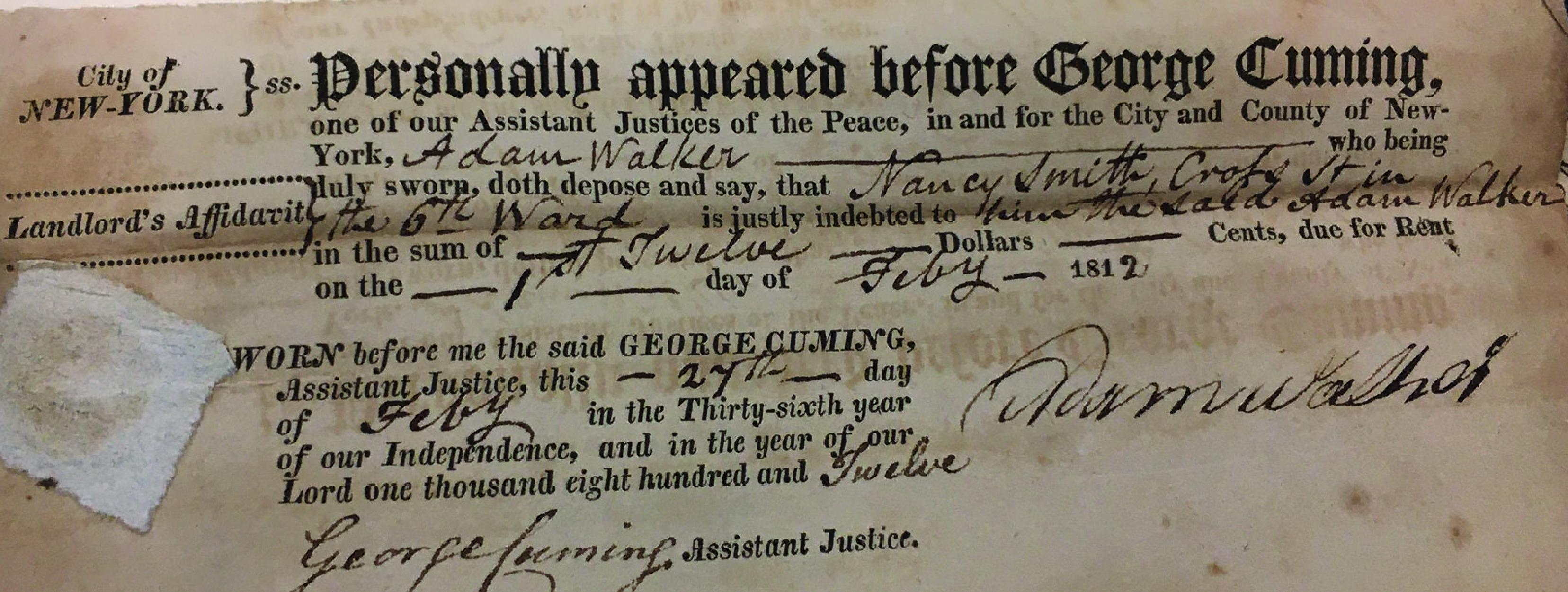

In 1811, for example, Nancy Smith was a twenty-six-year-old Black woman who worked as a “washer” and rented an apartment on Cross Street in New York City from a man named Adam Walker, a grocer in the sixth ward. She paid twelve dollars per quarter ($48 per year). When rent came due on February 1, 1812, she was unable to pay. She may have been injured or ill, falling behind on her work and thus the wages she could have used to pay Walker his rent. By November, she had been admitted to the almshouse, where she was described as “lame.” Not long after, on December 6, 1812, she died there.Footnote 23 Smith’s arrears of rent are documented because, after a few weeks without receiving payment, Walker filed an affidavit with a city Justice of the Peace attesting to Smith’s delinquency (Figure 3). The previous year, in April 1811, the state legislature had passed a law requiring landlords to file an affidavit attesting to the amount of rent a tenant owed prior to distraining a tenant. Several thousand affidavits were filed in the first few years after this legislation took effect.

Figure 3. Affidavits for Rent (1811–1812, 1814, 1816–1819), Division of Old Records, Mayor’s Court of New York, 1811–1812, 1814, 1816–1819.

These affidavits document who landlords and tenants were in NYC in the 1810s, how much people paid and charged for rent, and the parts of the city where people behind on their rent were living. They act as a street-level through-line to anchor the debates over reform and welfare that were occurring in newspapers, coffee houses, city hall, and the legislature. The law requiring the filing of these affidavits was passed because of philanthropists’ lobbying, which had relayed word of the impact that the laws favoring landlords had on tenants. Many of these reformers had been interviewing people experiencing poverty to better understand their needs, to proselytize about morality and abstention from alcohol, and to determine whether they were truly “worthy” of assistance or should instead be left to fend for themselves. The representatives of these charitable societies acted as conduits of information about the subsistence activities of the poor to the legislature and Common Council. These organizations were paternalistic, often racist, sexist, and certainly classist, but the severity of the economic situation in the first decades of the nineteenth century seems to have persuaded them to join philanthropic, moral, and religious goals with political ones, lobbying lawmakers to provide the laboring poor with the conditions in which to provide for themselves.

Philanthropists’ Petitions

In January 1810, the Humane Society of the City of New York convened a meeting of representatives from twenty-one different charitable societies in the city at the New York Free School. They had myriad diverse goals for improving the city’s moral compass and material conditions, discussing a wide range of social ills. Each group reported the information that its members had gathered about conditions within their community, and a few key action items rose to the surface as concerns shared across these organizations: the inhumanity of incarceration for small debts, and the deplorable conditions inside the Bridewell, and the vampiric exploitation of poor tenants by wealthy landlords.Footnote 24 The group drafted a letter addressed to the New York legislature and published it in the Commercial Advertiser, in which petitioners claimed that the “furniture” of “impoverished tenants…[was] often sold by a merciless landlord. Ought not,” the editorial’s anonymous author, “Civis” asked, “the legislature to enact a law…to protect the bed and bedding of those, whose poverty and not their crimes have brought them into misery?… Humanity demands your interposition – justice sanctions it – liberty requires it, that the prosperity of the rich should have bowels of compassion for the adversities of the poor.”Footnote 25

The letter was sent to the city’s Common Council, published in multiple newspapers, and read before the Assembly of the State of New York on February 12, 1810. The petitioners requested “legislative interference” to support the ability of the poor to sustain themselves by exempting “from seizure or detention the mechanic implements, bedding and wearing apparel, of poor and industrious persons.” The societies represented included several who had direct contact with people experiencing dire poverty, who made a project to ascertain the causes of their destitution. While they heaped blame on alcohol and idleness, they also decried the unrestrained greed of landlords. “Never did our city contain so many objects of misery - of hard, excruciating penury, as at this moment,” they wrote. Many were forced to “part […] with the means of their permanent support, to obtain a temporary supply for their family” to pay rent or buy food or firewood, like “the mechanic whose rent could not be paid without sacrificing the implements of his trade.”Footnote 26 The authors argued that “it is well known that the funds” of the city’s charitable institutions “do not bear a full proportion to the wants of their several objects in common seasons, much less in the emergencies…There are according to their statements multitudes who have heretofore subsisted by daily labor, ranging the streets in search of employment, destitute of clothing, food, and a lodging in these inclement nights.”Footnote 27 In their petition submitted to the Common Council and the state legislature in 1810, reformers argued that distraint, in particular, was a “grievance operating appreciatively upon the poorer classes,” because it allowed landlords to seize “implements and tools of trades and possessions, bedding and wearing apparel” that would otherwise have aided the poor in remaining independent. The petitioners asked whether “the humane provisions of the common law which exempted some of the articles from seizure ought not rather to be extended than restricted.”Footnote 28 The Common Council committee that considered the 1810 petition deemed their requests “of great importance and as such require[ing] the serious attention of the Common Council,” agreeing to “consider such measures as shall appear to be best calculated for effecting such of the objects of the said petition as shall be found practicable and proper.”Footnote 29

In response to the reformers’ petitions, the New York legislature passed a law in April 1811 requiring that landlords file affidavits prior to distraining tenants. The goal seems to have been to ensure that landlords were not extracting more than the law marked as their due, erecting a paper-thin barrier of protection for poor tenants. It also created a level of legal accountability that reformers and legislators seemed to hope would allow the working poor to keep themselves independent, not adding new names to the relief rolls but rather facilitating workers working to pay their own rent. The paperwork generated by the 1811 law led to the creation of a robust archive of landlords’ affidavits, preserved alongside other records generated within the Office of the Mayor’s Court and City and County Clerk’s Office. These affidavits, such as the one for Nancy Smith discussed above, document who was behind on their rent, where the property they rented was located, when their rent was due, and how much they owed, sometimes even their occupation, gender, or race. Each affidavit was filed before a justice of the peace “under penalty of perjury for wilfully swearing falsely.” They sometimes include descriptions of the amount of space the tenants rented—whether a full house, “part of a house,” a tenement and stable, or a “cellar kitchen.”Footnote 30

A Quarter of the Population Targeted for Distraint

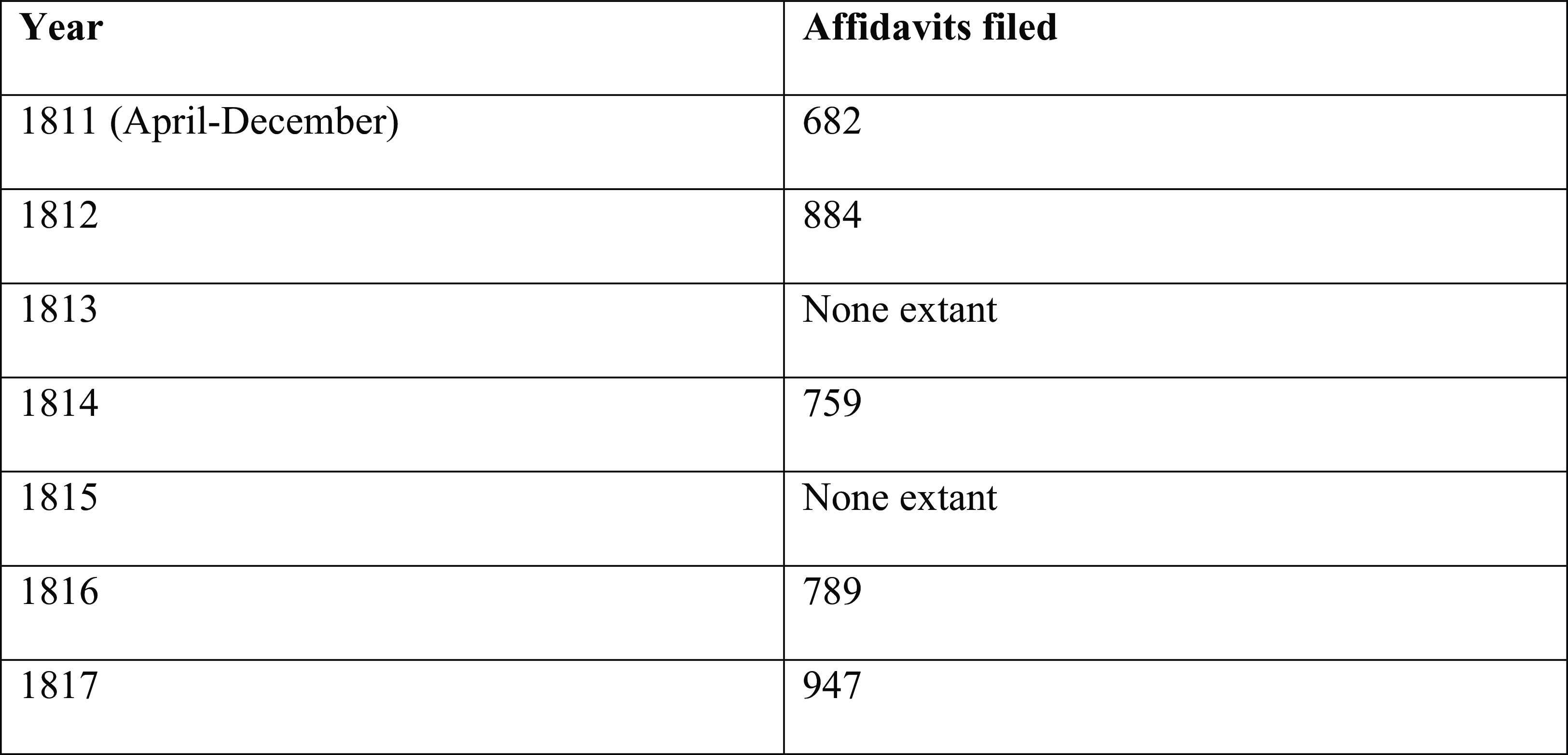

There are approximately 4,061 extant affidavits spanning 1811–1817 (no affidavits are recorded for 1813 or 1815; see Figure 4).Footnote 31 In 1816, the total population was around 100,233, the number of rent affidavits filed represents delinquency in rent payments for about 4% of the city’s population.Footnote 32 But the leaseholder or householder listed in the affidavit was merely the person responsible for paying the rent. The proportion of the city population represented in these affidavits rises substantially when the rest of the members of the household are counted, who would have been equally if not more impacted by distraint (notably spouses and children relying on breadwinning leaseholders for subsistence), whose beds and bowls would have been seized.Footnote 33 The average household size in New York City in this period was approximately 6.5 persons, meaning that possibly as many as 26,169 people, or twenty-four percent—almost a quarter of the city’s population—lived in households delinquent in rent payments between 1811 and 1817, as indicated on these affidavits. A large proportion of city residents are represented in these affidavits as tenants in arrears. In the first year after the passage of the law requiring landlords to file affidavits prior to distraint (between April 1811 and April 1812), at least 1200 were filed. While it is not feasible to determine the outcomes of each case of unpaid rent, these documents indicate how common an experience it was to be behind on one’s rent in early republic New York City, with the household goods of thousands of city residents liable to be seized at a moment’s notice. This number does not include every single person who was unable to pay their rent for at least a month or even those whose landlords intended to evict them for unpaid rent—simply those who filed an affidavit with the city so that they had the option to distrain their tenant legally.Footnote 34

Figure 4. Affidavits filed, by ward, which list the ward in which the tenant rented a residence) between April 1811 and May 1812 (Total: 447 out of 1200; percentages are rounded).

Did all these landlords go on to distrain? New York law allowed these affidavits themselves to stand as warrants, so it is difficult to estimate.Footnote 35 Perhaps landlords used the act of filing these affidavits as leverage to pressure tenants into payment. They did commit to it by paying a small fee; it appears that at least one Assistant Justice of the Peace who collected these affidavits charged landlords a fee of 6.6% of the total cost of the unpaid rent they were reporting for processing the affidavit.Footnote 36 If they did choose to distrain, they would also have to pay sheriff’s poundage and other constables’ fees for carrying out the actions, so it would make sense only to distrain for amounts from which they’d receive more than they’d spend on distraint.

There is much the affidavits can tell us about landlords and tenants in New York in the 1810s, and much that they cannot. The dollar amounts listed as arrears of rent on the landlords’ affidavits do not necessarily reflect any consistent amount of rent paid or unpaid since some tenants issued payments to landlords on a monthly, quarterly, or annual basis. So, one landlord affidavit for $20 could reflect a full quarter’s unpaid rent on a single room or just the proportion that remained unpaid on a house renting for $200 per quarter. The affidavits were filed by the ward, and different justices recorded different information about the landlords and tenants involved. Some affidavits noted individuals’ race (e.g. Cuffee, “a coloured man,” owed $8.50 in rent in April 1811), some noted occupation (e.g. Elizabeth Williams, mantuamaker, owed $37.17 in January 1814). Sometimes the street addresses of rental properties are listed, other times just a ward, or no location at all. Some justices wrote these documents out by hand, while others used preprinted “Landlord’s Affidavits” forms. Some landlords filed an affidavit immediately, the very day that the rent was due, while others waited days, weeks, or months to file. And the size of the property being rented is also not uniform, nor often indicated, so the thousands of affidavits include rents for large furnished houses for which tenants are paying hundreds of dollars quarterly, as well as single rooms for a few dollars per quarter, and even a few anomalous commercial storefronts of varying values.

The affidavits affirm historians’ assessments of tenants and landlords as heterogeneous groups in early Republic New York, spanning the breadth of the class spectrum.Footnote 37 Subletting and renting rooms to boarders was also a common practice, further complicating quantitative analysis of these affidavits. Of the affidavits filed in the first year they were required (from April 1811 to May 1812), 447 explicitly state the ward in which the tenant resided (just under half of the affidavits filed that year). Among these, half lived in Wards 6 and 10 (Figure 5), the wards in which working-class mechanics, recently arrived Irish immigrants, and African Americans resided. These documents encompass a range of economic situations, from the destitute renting a single room in a rundown tenement on Mulberry in the Five Points, to the middle and upper class with shifting fortunes unable to pay rent on an entire house on Broadway.Footnote 38 Some affidavits describe renters owing hundreds of dollars for expensive properties, such as William Neilson, who filed an affidavit on February 26, 1812, stating that his tenant Reay King owed him three hundred and fifty dollars for two quarters’ rent of a house at 46 Water Street, which had been due February 1. Some landlords who appear in these affidavits were themselves among the working poor, subletting rooms to boarders, or renting out properties they couldn’t afford to maintain on their own. Their class is sometimes intimated in a listed occupation, or by their lack of literacy, singing an affidavit with a mark. Aaron Lucas, for example, a shoemaker living at 45 Hester Street along with numerous other working-class tenants, filed an affidavit on May 7, 1817, stating that William Tate owed $8.75 for rent of a room due on May 1. He signed the affidavit with his mark.Footnote 39

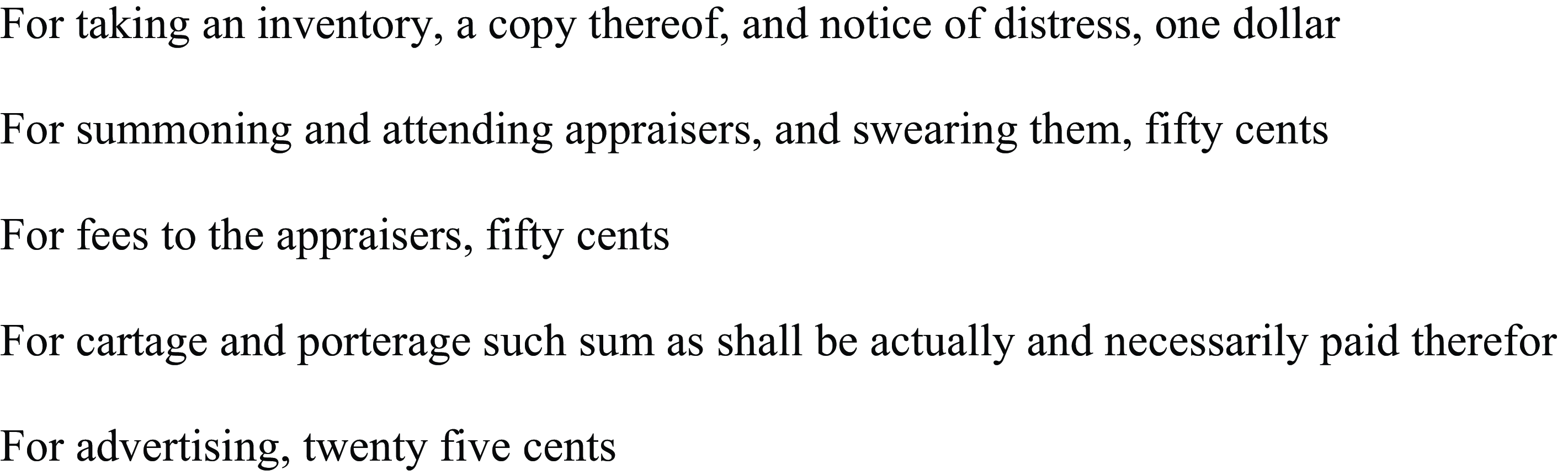

Figure 5. Excerpt of “Fees on making Distress for Rent,” set by New York City Common Council, 1817.

With seasonal gaps in income and a volatile economy shifting based on national and global affairs, many early republic Americans found themselves occupying different classes throughout their lives. Willet Warne worked for years around the turn of the century as an ironmonger who ran a shop in New Brunswick, NJ and sold ironmongery and assorted other household goods in Manhattan.Footnote 40 But by 1807, he was confined in a debtor’s prison in New York City. Within months of his release, he had reinvented himself as a housing broker and commission agent assisting landlords and tenants in facilitating property transactions and rental agreements. In May 1808, he advertised the location of his “house register office,” where “the books are open” to examine lists of houses, stores, farms, and lands “to let or for sale.” In late January 1809, he took out an advertisement in the New York Evening Post headed “Quarter day approaches - Look out.” He announced his plans to “open a book for each ward, to contain a list of all houses to rent with the street and number and terms. And he hereby offers to landlords to insert such houses gratis in his books. Thus, those wishing to let may avoid the unpleasant circumstance of plastering up bills on their houses, and those wishing to hire may for a trifling compensation save themselves the trouble of hunting round the city.” But Warne himself was a renter, who, in 1811, was accused by his landlord Theophilus Marcelis, of owing $62.50 for rent of a house in the third ward. In turn, Marcelis declared insolvency, followed not long after by Warne’s own declaration of insolvency in 1813. The dozens of advertisements Warne placed in newspapers warning tenants and landlords about Quarter Day must have had their own anxious connotations, given his personal situation.Footnote 41

Sometimes these affidavits reveal a strikingly clear stereotypical class division between landlords and tenants: Abijah Barber rented a room and bedroom in a house situated in Hudson Street near Budd Street, from Daniel Westervelt, a “gentleman.” In his affidavit, Westervelt describes Barber as a “labourer” who paid ten dollars per quarter in rent ($40 per year). In the 1812 City Directory, Barber is listed as a Cartman, residing on Essex Street in the 10th Ward, perhaps having relocated after facing distraint.Footnote 42 Many cases represented in these affidavits also blur social and economic categories: in September 1812, Cato Rainwood filed a landlord’s affidavit attesting that his tenant William Ward owed $102.50 for ground rent. Ward is listed in the City Directories around these years with no occupation; Rainwood is not listed in the Directory at all. Rainwood, born in Africa around 1728, was a Black man listed on the 1800 federal census as head of household in the fifth ward, residing with two other free people of color. The ground rent had been due to him back in June, and remained unpaid, perhaps because Ward had filed an insolvency petition the previous year. This may have had a cascading effect, or some other circumstances may have turned Rainwood’s fortunes, but nevertheless, by 1813, his real and personal property was being sold at a sheriff’s sale, and by January 1819, he was admitted to the New York City Almshouse. He died a few months later and was buried in one of the Almshouse potter’s fields. There were countless hurdles between Black New Yorkers and a fair wage, subsistence, and property ownership because of their race. Rainwood had likely lacked educational opportunities, as he, like many others, signed his landlord affidavit with an “x” for his mark. Other landlords represented here were among the most eminent early Americans: John Jacob Astor, for example, filed dozens of affidavits between 1811 and 1819.Footnote 43 His affidavits sit in the stack of trifolded papers directly next to those of washerwomen, cartmen, seamstresses, and cordwainers.Footnote 44 His wife, meanwhile, Sarah Cox Todd Astor, was a donating member of the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children (SRPWSC), one of the organizations lobbying for limitations on the rights of landlords like her husband to distrain their tenants.

Diverse Classes of Tenants and Landlords Turn to the Law

The diverse landlords represented in these affidavits have one important thing in common: they chose to turn to the law. Whether they were planning to distrain a tenant as punishment for withholding rent payments or to ensure they had enough cash to buy food for their children, they saw distraint as a tool which they may choose to use to wield the weight of their role as one deserving of payment. Did they trust the law to carry out their wishes and meet their needs? Was the decision to go before a justice one of the fruits of a still-young democratic vision, or a last resort option like knocking on a tenant’s door with a pair of fists? Distraint could have been seen as an option to use while trying to avoid evicting a tenant, giving them more time to pull themselves together before throwing them out. These affidavits may be evidence of a view by some poor landlords that the protection of law included them, too. Maybe we should read this similarly to the cases that came before the city police court in the 1810s–20s, which were populated by poor people, immigrants, and people of color, turning to the law for protection, compensation, or retribution, filing cases over small thefts or social provocations.Footnote 45 Whatever the motives of these landlords, they nevertheless trekked to the offices of assistant justices of the peace in every ward of the city, sometimes dozens in one day.Footnote 46

Some landlords may have filed for distraint because they intended to evict their tenant, at least after 1813, when state law stipulated that “to recover the premises on the ground of a forfeiture of lease by nonpayment of rent, the landlord is bound to show, either that no sufficient distress was to be found up on the premises, or a regular demand of the rent according to the rules of common law” did not yield payment.Footnote 47 But distraint did not always lead to eviction or removal. In October 1811, for example, Daniel Johnson, an oysterman, owed “widow Eve Bunce” $37.50 for several months’ rent at a house on Cherry Street; he was still listed at the same address in the 1812 City Directory.Footnote 48 Elsy Gordon, a widow who lived at 111 Lombardy Street, owed a woman named Elizabeth Lindsay eight dollars and fifty cents for rent due February 1, 1812. Three days later, her landlord filed an affidavit attesting her delinquency, signing it with a mark. Elsy was behind on her rent because she’d been admitted to the almshouse shortly after the last quarter’s rent was due in December of 1811. She was discharged by Spring and remained Lindsay’s tenant – whether because she found the means to pay her arrears or because Lindsay found a way to live without the eight dollars.

Most New Yorkers were renters during these years, “emphatically working for landlords,” as one commentator described residents’ subsistence efforts, organizing their lives around an ability to pay their rent and keep a roof over their heads. Only a narrow proportion of the city population was property owners: an 1813 city census counted 3, 212 freeholders against 13,804 leaseholders; in 1814, 22.7% of voters in the city-owned property, while 77.2% were renters.Footnote 49 More than half of New Yorkers lived in multiple-family homes, double that of the other large cities at this time.Footnote 50 Some tenants listed in the landlords’ affidavits owed weeks or months of rent arrears; in other cases, landlords filed affidavits the same day their tenants’ rent was due.Footnote 51 These affidavits paint a picture of the early New York domestic sphere as one governed by the Sisyphean task of remaining solvent and sheltered. During these years, as Sean Wilentz documented decades ago, the “distribution of wealth became increasingly unequal,” and “by the late 1820s, a mere 4 percent of the population owned half of the city’s noncorporate wealth.”Footnote 52

Approximately 743 affidavits were filed by landlords between May 1811 and February 1812. The majority, 52%, was for arrears of less than $20; about one-tenth were for less than $5. The scrimping and strategic planning of many people experiencing poverty shows up in these records with incremental payments to landlords: many tenants paid portions of their overall rent due when they had cash at hand. Abraham Herrington, for example, who was a “market man” and landlord, signed an affidavit on February 3, 1812, stating that his tenant Hanna Thompson owed him three dollars in rent for “part of this deponent’s house in the fifth ward.” A week later, on February 11, he filed a subsequent affidavit stating that she owed just one dollar and twenty-five cents for the balance of rent due that day for the part of the house at 54 Warren Street that she occupied. Thompson must have scraped together a week’s wages to pay her landlord a portion of what she owed, but he wanted to retain the option of distraining her for the remaining dollar and change, and so he filed a second affidavit.Footnote 53 On May 1, 1811, Littleton Elezy filed an affidavit stating that Mrs. Smith owed him three pounds, twelve shillings, and four pence. She was due to pay a full quarter’s rent of $10 but was “lacking one week.”Footnote 54

Some landlords, however, were unwilling or unable to accommodate tenants’ slow trickle of incremental payments. Despite the diversity of landlords and tenants as classes of New Yorkers, many if not most of the extant anecdotes about the impact of distraint upon tenants highlight the law’s use for “cruel” purposes. In March 1811, a “poor and friendless widow, named Burger” who had “previously paid her rent punctually” was not earning enough to pay in full. Catharine Burger was a “tailoress” living at 110 Reed Street when her offer to pay the landlord “a stated sum weekly out of the earnings of her manual labour until the amount due should have been paid” was denied. Her landlord was described in an editorial, Commercial Advertiser, as “wealthy, but cruel, rapacious, vindictive, inexorable, and unfeeling” who “brutally attempted to deprive” the widow and her “three children of the shelter afforded by a desolate house, during…[a] severe snowstorm.” The landlord had her “confined in the debtors prison of this city” for this “paltry…house rent,’ leaving “her three children…deprived of support and destitute of sustenance.”Footnote 55 The plight of the widow Burger caused quite a stir and was reported repeatedly across at least five different New York newspapers.Footnote 56

Public outcry against the landlord who had thrown Burger in debtor’s prison was swift and fierce. According to one editorial signed “An Enemy to Oppression,” the case excited a “sensation…in the public mind” which “alarmed the prudence, if it did not soften the heart, of her unfeeling landlord.” He visited her in debtor’s prison to negotiate the terms of her payment, hoping to “stifle the public clamour” while still ensuring he received his “settlement.” While he and Burger were conversing, a crowd of “sailors and other prisoners, who had been made acquainted with the circumstances of the case,” lined up to “pay their respects to him.” Their respects included “a cold bath” and “jokes, at his expence [sic], as hard as a brick bat.” They “sprinkled him pretty freely, with a mixture of saw-dust and ashes” until he attempted to “unceremoniously [take] his leave.” As he departed, the prisoners “dismissed” him with “three hearty cheers,” relishing the embarrassment of one they clearly viewed as an oppressive landlord. It worked: “in less than one hour, he sent the poor widow a complete discharge.” Distraint and debt imprisonment were viewed by many poor people, workers, reformers, and some officials, as evidence of the oppression of the poor by the wealthy. New Yorkers were clear on whose behalf reform was needed. The tone with which interactions between landlords and tenants reported in newspapers, especially those with a primary mechanic audience, and by some reformers, suggests many New Yorkers believed they were engaged in a form of class struggle, as they advocated for changes to assist the people of whom the law and their neighbors were taking advantage. The prisoners throwing sawdust on a wealthy landlord, Burger herself, members of the Humane Society, and the SRPWSC, were speaking the same language, even if not using the same words. Law, as well as the application and enforcement of the law, was up for debate among rich and poor alike.

On the other hand, when a widow named Blois, who owned a house in which she rented a room to a boarder to sustain herself, was “reduced…to want” as “consequence of a failure in the payment from her tenant.” She received a donation of $5 from the SRPWSC in 1814. As a property owner, she would have been categorically excluded from receiving aid from the organization, which tried to limit their assistance to the most needy and the most “deserving” recipients. But, the directors and members recognized that owning property was not an automatic indication of one’s class status or access to cash. With women’s wages so low, employment opportunities so limited, and the cost of housing and raising children so high, they made an exception when circumstances dictated.Footnote 57

May Day, in Many Senses of the Term

Rental turnover was high in nineteenth-century New York City, even when arrears or evictions were not factors. The city engaged in the notorious practice of observing “May Day” with all leases beginning and ending on the first day of May, each year. One commentator writing in the National Advocate reported that “the custom of commencing the year for renting tenements on May day” created a “scene of confusion, trouble, and difficulty” that “defies description.” It was not only the day that new leases began, but was also one of the days that quarterly rents were due, meaning that many tenants needed to raise “a large sum of money” to pay rent, often “at great sacrifices.” The high turnover each May enabled “landlords to get at least 15 percent more than they otherwise would, from the competition of tenants.” Furthermore, the editorialist argued, “when property is distrained for rent, the sales of furniture occurring at the same moment,” the market for used furniture becomes glutted and it takes far more goods to recoup the costs, encouraging landlords to distrain more goods than they might have if an inventory were assessed at a different time in the year. Landlords may have even seen it as more advantageous to distrain goods so that they could upsell them for a profit than to evict a tenant and then wait to find a new one who could pay. While “the necessity of a reduction in the nominal value of things, is generally admitted,” the editorialist wrote, that “there is nothing that requires reduction more than rents.”Footnote 58 Between 1790 and 1830, New York’s population grew six fold, meaning that landlords “received better offers from those seeking housing,” which compelled them to “squeeze every cent they could from resident tenants,” which in turn led many residents to move each May to try to outrun rising rents.Footnote 59

As with landlords, some officials used legal imprecision and opportunistic timing to exploit constituents, setting fees, and costs according to their own interests. In 1813, the constables and marshals responsible for carrying out distraint complained to the Common Council that their pay was insufficient for the duties involved in this work. They requested increased compensation for taking inventories of tenants’ goods, for working with appraisers to determine their value, for carting and porting the goods, advertising sales, et cetera. That March, the Common Council heard a report from a committee assigned to investigate precedent for the constables’ request found that “there is no law of this State, making any allowance…for distraining goods for arrears of rent, tho’ it would seem they are compelled to do the duty, which is always attended with more or less trouble and responsibility.” Customarily, the committee reported, the marshals and constables “have considered themselves at liberty to charge a reasonable compensation” for this work. It was found, however, that these officers “have from time to time encreased [sic]” their fees “until their extractions have become exorbitant and oppressive particularly in cases where the rent has been of small amount, their fees have exceeded double the rent distrained for, and as these impositions are generally practiced on the poorer part of our fellow citizens, who do not always understand their rights or if they do have not the means of obtaining redress by the ordinary course of law it would be very desirable to put a stop to such abuses and to regulate the fees of the officers.” Thereafter, the council set fees for the officers facilitating rent distraint for landlords to curb their “exorbitant…extractions” from the poor (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Example of a landlord affidavit, 1812.

A few months later, while the council was curbing the entrepreneurial tendencies of constables, a group of self-described “humane and benevolent persons” in New York City organized to protest the practice of distraining goods necessary for survival from “indigent widows and females, of various descriptions.” This group, the SRPWSC, asked the state legislature to exempt certain goods from seizure by landlords for unpaid rent “for the purpose of aiding them in supporting themselves and their families.”Footnote 60 The legislative committee to whom the memorial was referred viewed it as “highly commendable” and “free from objections”; when the bill based on the petition was introduced, it was unanimously approved.Footnote 61 This law, passed on April 15, 1814, exempted “all looms, spinning-wheels, and stoves, together with the appurtenances thereunto belonging, or in any other manner attached,” along with the necessary fibers for spinning and related work, from being distrained.Footnote 62 Charitable organizations sometimes loaned such tools to women to make it easier for them to work from their homes and support themselves, in part motivating this law. Conducting paid labor inside of the home was essential for women with childcare responsibilities as well as the need for income. There were almost no formal resources available for others to share in the care of children while mothers worked, though of course, some engaged in collaborative arrangements with family and neighbors. This 1814 law also protected employers, who sometimes sent manufacturing tools home with women as part of the “outwork” system.Footnote 63

In 1815, the legislature expanded the list of goods protected from distraint to include “all necessary wearing apparel and bedding, all cooking utensils, one table, six chairs, six knives and forks, six plates and six teacups and saucers owned by any person being a householder,” alongside “ten sheep, together with their fleece and cloth manufactured from the same, one cow, two swine, and the pork of the same.”Footnote 64 This list of objects adds texture to our understandings of the quotidian lives and material circumstances of workers in this period and also links the legal history of rent distraint and its reform to simultaneous efforts to reform and/or abolish debt imprisonment.”Footnote 65 In 1816, in New York, 57% of incarcerated debtors owed less than $50 and 38% owed less than $25. By 1817, it was illegal to incarcerate any debtor who owed less than $25 (just five years after the state banned the incarceration of women for debts below $50, in the same piece of legislation that introduced the affidavit requirement for distraint).Footnote 66 Similarly, nearly half of the landlords’ affidavits filed in New York City in 1811–1812 were for arrears of rent below $20.Footnote 67

Reformers concerned about distraint were attentive to acute crises as well as everyday needs. Fire, extreme weather, or disease could reduce even independent, middle-class New Yorkers’ to desperation.Footnote 68 When New York City endured a deadly yellow fever outbreak in 1822, it instigated grassroots tenant organizing against landlords’ power. Thousands died that year, and thousands more fled the city to protect themselves from infection. The neighborhood where it was concentrated, near the port and Wall Street, was all but abandoned. It was not just the rich who fled, with many workers and poor families aiming to preserve their lives above their livelihoods heading to the outskirts of the city.Footnote 69 On October 4, the Spectator published a report that hundreds of residents, particularly in the “infected district” have “denied themselves the necessaries of life, to enable them to pay the expense of removal.” As autumn progressed, “in addition to the former wants of a family, they will require to provide fuel and cloathing [sic] to protect them against the inclemency of the season.” Their circumstances were quickly becoming desperate. Many tenants who left their rentals to escape the fever returned to find that their goods had been distrained for rent. One editorialist argued that it was “the duty of the rich to deny themselves many of the comforts of life, that they may succor those who have not the means of averting the calamity.”Footnote 70

The tenants organized, calling a meeting at the Albany Coffee House in mid-November 1822 to draft “an address” to landlords and appoint a committee “to make up subscriptions for those whose property may be distrained for rent.” The tenants “who were obliged to leave their tenements on account of the late epidemic” published an address “to their landlords” soon after, in the National Advocate. The authors declined to condemn the landlord’s “right” to rental payment, acknowledging that not all landlords were, in fact, wealthy, but argued in favor of a fundraiser to “redeem the goods of those distrained for rent.” They asked that landlords “who can afford it” to be “accommodating and take their rent in such small sums as may be convenient to tenants.” They acknowledged that most tenants “are poor men.” During the epidemic, they were “driven from their homes by an arm which it was death to resist.” As a result, “their means of living, and of paying rent [were] entirely cut off.” The authors understood the socioeconomic diversity within the classes they occupied and that their landlords occupied: “Are you a rich landlord?” they wrote. “Shew, by your generosity, that wealth has not hardened your heart…. are you, as is sometimes the case, a poor landlord? then share with your tenants the difficulty of the times…that you can be magnanimous…. If your tenant be poor - throw off the rent.” Writing primarily from the perspective of economically stable tenants, they called for a rent freeze or temporary forgiveness, even though “many of us can pay our rents with ease, and some of us have already done it; but we act for a suffering portion of this community.” Knowing there would be many who disagreed with their approach to handling the aftermath of the epidemic, they were prepared to reach into their own pockets to soften the blow: “some landlords may rigidly enforce their claims for rent and even proceed to distrain the goods and chattels of tenants and thereby oppress many poor families who have been driven from their homes.” For those tenants, this group formed a committee “to raise subscriptions for the relief of such families.” The authors of this address also lauded landlords who they’d heard had agreed to forego a quarter’s rent to help tenants get back on their feet.Footnote 71 Meeting at the Albany Coffee House was likely a strategic decision, as it was the location of many public auctions and sheriff sales, where it was not unlikely these tenants’ goods might be sold.

Conclusion

By the 1840s, population growth and mobility had expanded so dramatically that it became easier for landlords to evict nonpaying tenants than to go through the ordeal of distraint, and lawmakers introduced summary process statutes to simplify these dynamics further. Distraint was abolished in New York in 1846, after the airing of grievances around landlords’ privileges during the “anti-rent war.”Footnote 72 The sociolegal history of distraint in early Republic New York documents the interests of a diverse cross section of city residents and legislators seeking to maintain economic equilibrium. Working-class New Yorkers were attuned to household economies, familiar with the rhythms of seasonal employment and the whims of property owners. They communicated their concerns and needs to middle- and upper-class reformers, who, when their interlocutors appeared to meet their criteria for industriousness and morality, saw an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone. Limiting the impact of rent distraint on workers’ ability to subsist would help the poor people most impacted by landlords’ extractions and would simultaneously forestall the likelihood they’d need to access public relief. This would keep workers independent and keep the municipal budget, and thus reformers’ taxes, in check. As a member of the New York City Society for the Prevention of Pauperism wrote in 1817, reformers were growing “tired of assisting [the poor] in their distress,” arguing that it appeared “more wise to fix on every possible plan to prevent their poverty and misery.”Footnote 73 These “benevolent” actions also led to policing, as reformers increasingly collaborated with authorities to engage in mass arrests and ejections of the “undeserving poor” as vagrants each autumn, before winter set in and they ended up costing the city money in either the almshouse the jail.

The needs of workers and the goals of reformers and officials converged around the issue of distraint. The story of these landlords’ affidavits, the reforms that led to their filing and that followed reformers’ acquaintance with the challenges workers faced, is one of the pursuit of systemic change. If the law allowed a “grievance operating appreciatively upon the poorer classes” like distraint, especially if public and private relief were insufficient to mitigate the impact, the law must be changed.Footnote 74 The story of these affidavits and the conditions surrounding them provide a new look at the realities of the early republic economy and the constraints the working poor faced. The affidavits add texture to our understanding of the lives of the housing insecure, documenting important moments in the experience of laws that brought poor, propertyless workers and landowning gentlemen elbow to elbow in the office of a justice of the peace, hoping to manifest some form of justice, or to at least keep a roof over their heads.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248025100941.

Acknowledgments

I first located a single, stray envelope of affidavits from May 1811 in the New York State Archives in Albany. Archivist Jim Foltz helped me track down the rest of the collection with which these were associated, with the help of Geof Huth in the New York Courts Archives in Manhattan. The staff members of the New York County Clerk’s Division of Old Records on Chambers Street, including Joseph Van Nostrand and Joshua Tavarez, were very generous with their time in tracking down the missing boxes of these affidavits in the records of the Mayor’s Court and Court of Common Pleas. This research was made possible by a Hackman Research Fellowship at the NYSA, and the drafting of this article was dramatically improved by discussions at the Columbia Early American Seminar, Rutgers Camden Lees Seminar, and a McNeil Center Brown Bag session. I am grateful for the support of the Rutgers University Department of History, and fellowships at the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Library Company of Philadelphia. Thank you to the many archivists and interlocutors who helped bring this story into print.