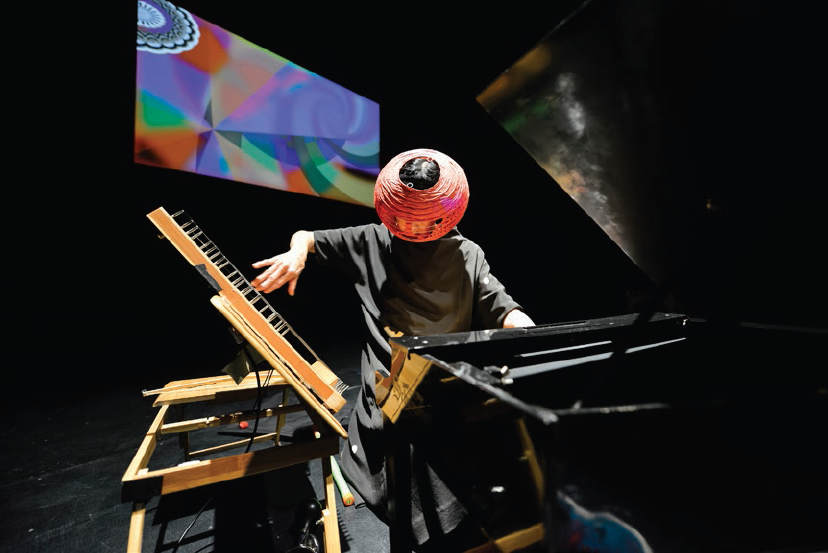

Figure 1. Margaret Leng Tan, wearing a monkey mask, cranks the wind-up toys in the movement “March.” Curios, 2015. School of the Arts Studio Theatre, Singapore. (Photo courtesy of Singapore International Festival of Arts)

Theatricality, Musicality, Theatrimusicality

In the first movement of Curios (2015), professional toy pianist Margaret Leng Tan steps onto the stage wearing a monkey mask and gestures to the audience acknowledging their presence.Footnote 1 The audience seems surprised; the applause is delayed and muted. Such a gesture is usually given at the end of a performance, not its start. Tan, flanked by two toy pianos, sits on an undersized stool between them. She picks up a beribboned box, unties it, lifts its lid, and places the contents on the stage floor, one at a time. They are children’s wind-up toys, including the iconic cymbal-clapping monkey. She cranks the toys and they wobble across the stage. The recorded ticking of hands from a grandfather clock increases in volume. Layered with the cranking of the toys, now amplified across the auditorium’s speakers, it evokes an ominous curiosity.

In yet another movement, “Phantasmagoria,” Tan expertly plays on the toy piano with the gestures and finger play of a highly trained classical pianist. Tan disrupts and sabotages the effect of her formal, classical playing by wearing what resembles a Chinese red lantern over her head. In another segment, Tan interrupts her piano playing with sudden pauses when she strikes her head with a squeaky toy hammer. While seemingly humorous, these actions affect the segment’s musicality, performativity, and reception. It communicates Curios’s dramaturgical intention: to perform the upside-down world of the carnival.

These are examples of Tan’s musicality as it is shaped by theatricality. One of the world’s leading virtuosos of experimental piano music, Tan is famous for turning a child’s toy into an instrument of serious music. What is most distinctive about Tan is not the novelty of playing the toy piano, but her theatrimusicality — how she actively incorporates theatrical actions in her performances. In an interview, Tan describes her theatricality as a “logistics of movement” in which gesture becomes a choreography determined by the music (Tan Reference Tan2020).

Theatrimusicality is a portmanteau of “theatricality” and “musicality,” implying an interaction where the adjectival “theatri” not simply modifies the emergent “musicality” but also asserts how the sonic, musical, and acoustical are determined by theatricality. Theatricality articulates the music. It is inherent in musicality, such that “musical utterances are transformed in a way that they become open for additional meanings other than the musical” (Hübner Reference Hübner2013:3). Theatrimusicality comprises not only the work’s formal properties such as melody, volume, and rhythm, but also its extramusical qualities including the emotional, ethereal, theoretical, and ideological aspects of the composition. Theatrimusicality “produces music, is encoded in music” but also is “made in response to music” (Jensenius et al. Reference Jensenius, Wanderley, Inge Godøy and Leman2010:19). It conveys affective meanings through sounds and gestures working together. In the world of classical music, any choreography added by the performer is disregarded and disparaged: sound is the basis for evaluating the performance (Tsay Reference Tsay2013:14580). A corollary to this is that theatricality — “non-serious,” extraneous, and excessive gesturing, body movement, and facial expressions — ruins the performance; inappropriate stage deportment indicates a poor understanding of musicality and is an attempt to obscure the musician’s lack of expertise or deep knowledge of the work. In avantgarde pianism — a term Tan uses to describe her musical style and performance mode — theatricality is imperative. It is not simply about the theatricality but is also about the spectator’s “awareness of a theatrical intention addressed to him.” It is a process of:

looking at or being looked at […], an act initiated in one of two possible spaces: either that of the actor or that of the spectator. In both cases, this act creates a cleft in the quotidian that becomes the space of the other, the space in which the other has a place. (Féral and Bermingham Reference Féral and Bermingham2002:98)

In an interview for a show at Singapore’s National Gallery, Minimalism Redux: Minimalist Music from Its Antecedents to Its Offshoots (2019), Tan describes herself as a “pianist, toy pianist, toy instrumentalist, performance artist, sometimes a vocalist” (in NGS 2019). The sequence of descriptors reflects her evolution as a musician and performer. Tan was trained as a classical pianist from a young age and was the first woman to receive a doctorate in Musical Arts from the Juilliard School in 1971. Her contemporary performance identity took shape after her encounter and collaborations with John Cage beginning in 1981. It was then that she began to explore the limits of the piano, including Cage’s prepared piano, and consequently grew to develop an inimitable style of piano playing. Cage had great influence on Tan as a musician, and she is considered to be among the world’s foremost interpreters of his music (Chew Reference Chew2006:48). With her plucking, strumming, and sliding objects along the strings, and in her performances of the prepared piano, for which objects such as bolts, wires, and strings are inserted between or under the strings, Tan cultivated movement sequences: a choreography and theatricality that would subsequently define her contemporary theatrimusicality. As Tan describes it, standing, sitting, and needing to bend over (to play on and with the piano strings) are gestures demanded by the music — they are not simply for effect (Tan Reference Tan2020). Such a logistics of movement was further developed in Tan’s toy piano playing. Best known as a professional toy pianist and the world’s first professional musician to take the toy piano as a “real” instrument of concert music (Tan Reference Tan2018), Tan’s debut as a toy piano virtuoso occurred in 1993 when she played Cage’s 1948 Suite for Toy Piano at his memorial tribute. Apart from Cage, Tan has worked with other composers such as Tan Dun, Ge Gan-ru, Erik Griswold, and George Crumb, all of whom have composed works to expand her choreography and theatrimusicality (Tan Reference Tan2020). Having released over 14 albums of Cage’s music, Crumb’s and Ge’s works, and the notable recording The Art of the Toy Piano (1997), in live performance, Tan is remembered for playing Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata on the toy piano at the Beethoven House in 2000 and performing Ode to Schroeder: The Art of the Toy Piano (1999) as a tribute to the comic strip Peanuts character Schroeder.

Tan’s contemporary theatrimusical identity synthesized what, in the classical music world, are fundamentally antithetical elements: serious piano music and a frivolous child’s toy; the sonicities of the toy piano and the grand piano — the instrument of classical music — reverberate with social difference. Carving a unique identity as a professional toy pianist allowed Tan to explore a new vocabulary and a new voice. Additionally, performing with a child’s toy allowed Tan to experiment with gestures and cadenzas that would be considered extraneous and objectionable in serious classical music performance. The marriage of Tan’s classical training and the toy piano gave rise to Tan’s theatrimusical approach to musicking,Footnote 2 where the logistics of movement, the theatricality, is born from the music (Tan Reference Tan2020).

Curios as Theatrimusical Carnival

Apart from exploiting movement and gesture as part of her performative identity, in the mature stages of her career, Tan began exploring other aspects of theatricality such as a careful crafting of the mise-en-scène with costume, props, and masks, and adding singing to her performance vocabulary. The performance of Ge Gan-ru’s Wrong, Wrong, Wrong! (2007), for example, saw Tan wearing a qipao, the iconic Chinese blouse of the early 20th century, while using her voice to parody Chinese jingju singing. Wrong, Wrong, Wrong! (2007) is a melodrama for voice and toy orchestra written for Tan by Ge, based on The Phoenix Hairpin, a poem by Song dynasty poet Lu You (1125–1210). In Hatta (2015), a piece based on the iconic character The Mad Hatter from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Hatta in Through the Looking-Glass), Tan played two toy pianos at opposing ends of the stage while moving pieces on a chess board located between; she also boiled water in a kettle and made tea. The sounds and actions were part of the musical composition.

Curios (2015) is an important work to evaluate Tan’s theatrimusicality. While her most recent performance, Dragon Ladies Don’t Weep (2020), is in Tan’s own words, a “full foray into theatre,” she believes Curios was the performance that led up to the maturation of her theatrimusical performance mode (Tan Reference Tan2020). Composed by Chinese American composer Phyllis Chen and commissioned by the Singapore International Festival of Arts for a 2015 premiere, Curios was part of a longer show titled Cabinet of Curiosities, which included Tan performing other experimental piano works such as David M. Gordon’s Diclavis Enorma (2007), James Joslin’s Hatta (2015), and Alvin Lucier’s renowned composition Nothing is Real (1990), in which Tan uses a teapot to amplify the music.Footnote 3

Tan’s collaboration with Chen is no surprise given that the latter composes for the toy piano and is herself a toy pianist; she is also Tan’s personal friend. Tan had discovered an old black-and-white photograph of three Kassino clowns. Enraptured by the image — its allure and bizarreness — Tan invited Chen to compose a work that exploits the reaction and sensations provoked by the image. Additionally, Tan wanted to convey the emotional depths of Nino Rota’s haunting theme from Federico Fellini’s La Strada (1954). Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962) was also a key source of thematic inspiration for Curios given that the dark fantasy novel revolves around two boys’ bizarre experiences of a traveling carnival (Tan Reference Tan2020).

These elements of the enchanting, phantasmagoric world of the carnival are evident in Chen’s description of Curios:

[Curios is] a multimedia work that draws the audience into a musical and theatrical Cabinet of Curiosities (a “Wunderkammer”), revolving around the bizarre, bewitching world of the carnival. Whether it be a roomful of carousels or a magic lantern, the “Wunderkammer” beckons to us to enter a novel visual and sound world with Margaret as our guide. Using toy pianos, toy instruments and other oddities, Curios is inspired by an intriguing 1920s photograph Margaret gave me of three Kassino clowns. This rather grotesque, haunting image embodies our shared fascination with the carnival and is entirely in-synch with Margaret’s natural ability to convey both humor and poignancy through her artistry. (in CultureLink Singapore n.d.)

Though not consciously or intentionally incorporated, Chen’s description alludes to Mikhail Bakhtin’s ideas of the medieval carnival, explored in Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (1963) and Rabelais and His World (1965). Bakhtin saw the carnival as a site of subversion, contradiction, and cohabiting dualisms: fascinating yet grotesque, humorous yet poignant. The carnival was a space and time of political possibility when assumptions of dominant discourses and hierarchies could be inverted. Curios is a performance of obversions, inversions, and opposites — in form, inspiration, and reception. Curios’s theatrimusicality captures Bakhtin’s spirit of the carnival, transposing his literary concept into a performative, embodied experience and opening up space to challenge our understandings of what music is and how it can or should be performed.

Performed in Singapore’s School of the Arts Studio Theatre and not a concert hall or recital studio, Curios begins with the proscenium stage strewn with wind-up toys, toy pianos, a toy bowed psaltery, a cuckoo organ, Japanese temple bells, singing bowls, and music boxes — all emphasizing aural attention. This is not to say that theatre performances do not involve aurality but, rather, that on Western stages musicality has often been regarded as secondary, except for postdramatic forms such as “composed theatre” (see Rebstock and Roesner 2012). In an opera house or concert hall, the sonic is primary. These dichotomies have been persistently interrogated and discarded in avantgarde and postmodern performances, as they have been in Curios, which in a theatre space appositely features the theatrimusical carnivalesque, a subversion of norms.

Explicit theatricality, replete with extra-musical elements, is most evident in the first movement described above. The audience is prompted to applaud as they would at the end of a show — an inversion of norms. The applause is followed by a sideshow of triviality and infantilism as Tan plays with wind-up toys as instruments. The absurdity is, however, juxtaposed with a portentous soundscape composed of ticking clocks. With the buzz from the moving wind-up toys, the rhythmic amplified pulse of the clocks signifies mortality and introduces a foreboding undertone. But far from being threatening, the experience is of a carnivalesque mesalliance. The opening segment retunes the audience’s ears to pay attention to incidental sound, rhythm, and time; to look not only at the performer but at the other nonanimate actors producing music as they “perform.”

Almost as if to further underscore this mesalliance, one of the wind-up toys collapses. Tan picks up the fallen toy and tries to keep it upright as it journeys along but such attempts fail, and she waves her hand at the toy in surrender. This is a moment of disrupted yet doubled theatricality, when Tan’s theatrical action is foiled by the “actor’s” (the toy’s) collapse. The toy’s failure to perform (both to “act” and to fulfill its task) adds to spectacle. Soft sniggers from spectators greet the toy’s “refusal” to perform — in reflexive recognition of the shattered theatrical frame. Laughter is, as Bakhtin observes, the basis of the carnival spirit; a laughter that is not individual but a “social consciousness of all the people” ([1965] 1984:92). It is regenerative, creating a carnival sociality and communality. As the opening movement, the performing toys (and one’s failure to perform) amuse and entertain, binding together the audience. This theatrical moment is also antitheatrical because Tan’s attempts to make the toy perform, and her eventual capitulation, is metonymic of the carnival as an inverted world — where the unstructured, unanticipated, and random occupy the same time and space as the sanctioned, structured, and intentional.

Even as this highly theatrical sequence of Tan playing with toys is perceived as nonserious, perhaps superfluous, by many among the more conservative musicians and musicologists, the resultant soundscape produced from the cranking motors of the wind-up toys harmonizing with a recorded soundtrack of other wind-up toys and interposed with the strident, regular rhythms of a ticking clock create the affective conditions of the carnival as a space of paradox and enigma. The soundscape not only attunes one acutely to how any sound is (and can be) regarded as music but sonically signifies an “other” time of an “other” place, a theatrimusical unreal dilated time experienced aurally.

Theatricality as/and Gesturality

Avantgarde music disrupts the conventional positions and conformations of the musician’s performing body, as John Cage’s prepared piano series did, requiring the pianist to stand, pluck, strum, or hit the piano strings while moving around the piano and gesturing. This contrasts with how classical concert pianists are expected to perform onstage. Chinese concert pianist Lang Lang, for example, is known to irk music critics for confounding these expectations with his physically theatrical playing (see Johnson Reference Johnson2016; Sharp Reference Sharp2011). Rudolf Laban described these normative expectations as imaginary boxes, which he named “kinespheres,” surrounding and limiting the performer and his range of motion ([1948] 1963:10). Such kinespheres are mental constructs that the musical performer is aware of before, during, and after performing. In a piano performance, kinespheres include the “home position” of the pianist: sitting upright in front of the piano, bent arms on the lap; or the “start position” with the elbows bent, wrists at the edge of the keyboard, and fingers touching lightly on the keys. In the “performance position” the pianist moves her hands and fingers left to right, forward and backward, up and down, in or off contact with the keyboard (Jensenius et al. Reference Jensenius, Wanderley, Inge Godøy and Leman2010:20–21). One can further subdivide kinespheres into different performance and gestural spaces — boxes for various types of musical gestures. These are gestural spaces that include the sound-producing kinesphere (hitting the keys), sound-modifying kinesphere (using the pedals), and the ancillary kinesphere (limited to the upper body and the head, where any action is deemed supplemental or extraneous to the music) (20–25). These kinespheres address the expectations of audiences; breaking any of the kinespheres causes surprise, or even disapproval.

Such kinespheric transgressions are evident in Tan’s performance of Curios not only as a feature of avantgarde music but as a way to evoke the carnivalesque world. Tan performs two identities and brings together two worlds: the classical music world as a professional pianist and Steinway performer and the carnivalesque world of her toy piano playing. In the fourth movement, the “Kassino Interlude,” Tan sits at a toy grand piano. Her posture accommodates the expected kinespheres of a classical pianist. Even though she is about to play on a toy grand, the movement within each kinesphere remains identical to that of a concert pianist playing on a full-sized piano: sound-producing gestures, sound facilitating gestures (phrasing and entrained gestures), and sound-accompanying or communicative gestures (such as raising the arms and wrists after an emphatic sequence is played) (24–25). Yet these expected kinespheres are punctuated by comical and idiosyncratic movements and actions that subvert the seriousness of play(ing): Tan wears the red nose of a clown during this segment; at intended rest marks, she picks up a yellow plastic toy hammer and hits her head with it to produce the characteristic “squeak,” which disrupts the reverberating sonicities from the toy piano. These sequences end as abruptly as they begin, and Tan reverts to “serious” piano playing. At a particular juncture, as the music crescendos and increases in tempo, she pauses, puts her hands on her ears, gasps, and shakes her head from left to right in a theatrimusical sequence that references common conceptions of avantgarde piano music as “noise.” As the music continues, Tan interjects serious play with strident sonicities. At one interval, she picks up two clown horns and squeezes them; at another, she blows into a shrill-sounding whistle as she places her flattened right hand to her brow, looking back and forth as if searching for something in the distance. “Kassino Interlude” ends with Tan, still seated in front of the toy grand, picking up a soft toy dog and hugging it closely while humming a melancholy tune. Tan explains that this sequence was inspired by a real-life incident when she lost her dog, Oscar, for three days (Tan Reference Tan2020).

The perforation of kinespheres by theatrical actions, and the intensification of sound-accompanying or communicative gestures can be seen as extraneous and simply comic. Yet, the active, intentional incorporation and arrangement of these gestures (and extra-musical sound effects) are vital to the compositional spirit and phenomenological reception of the work and as indicators of the dualisms characteristic of the carnivalesque. It is not simply the juxtaposition of “nonserious” theatrical (and sonic) actions — blowing a whistle, whacking a squeaky toy hammer, humming to a huggable toy dog — with the appropriate gestures and kinespheres of “serious” piano playing; the carnivalesque dualism of “Kassino Interlude” is evoked because of the sonic quality of the toy grand piano as well, and because the common regard for it as a child’s toy (and therefore played as a toy) contrasts with Tan’s kinespheric movements of a professional concert pianist. Seeing Tan move as a concert pianist while listening to the “imperfect” frequencies and distinctive sounds of the toy piano generates an alienating visual-aural disjuncture characteristic of the carnivalesque.

The Phantasmagoric and the Grotesque

Masks, Movement, Music

Among Bahktin’s key ideas about the carnival is the grotesque body. The grotesque body is one that is hideous, deformed, and full of apertures or convexities, but it signifies “a body in the act of becoming” ([1963] 1984:317), the corporeal site for regeneration and restitution. Such “grotesqueness” is also found in the use of masks that underscore the strangeness of the body, and where such bodies become a “stage for eccentricity” (Lachmann et al. Reference Lachmann, Eshelman and Davis1988–1989:146). While understandings of “grotesqueness” differ then and now, what remains unchanged is the reception of these bodies and their possibilities of “becoming.” In Curios, grotesque bodies are presented as images of the Kassino Clowns enlarged, screened, then altered and distorted; the clowns’ alluring strangeness is amplified for close examination; another “deformed” body sits below this projection: Tan is seen playing on a toy piano and toy psaltery with an oversized orange mask over her head. While neither is as hideous, deformed, or macabre as Bakhtin’s carnivalesque body, both the videated and live bodies are abnormal, aberrant, and “malformed.” They allude to grotesque bodies as sites of eccentricity but also of “becoming.” Tan, in fact, described the photograph of the clowns as “lurid” and “grotesque” (Tan Reference Tan2020). More importantly, this performance of grotesqueness can be read both as an inversion of the established order of a piano recital, a becoming of avantgarde piano music, and a regeneration of our expectations of music (and music performance).

The image of the three Kassino clowns, which is so central to the spirit of this composition, is taken from a postcard of unknown origin, circa 1920. It features three clowns with dwarfism standing in front of a tent, their short stature further exaggerated by oversized clothing, made grotesque in appearance by white-painted faces and clown collars. Apart from their characteristic clown noses, the clown in the center, the only one looking at the camera with a neutral, deadpan expression, has exaggeratedly large fake ears. His costume has a large open pocket that houses a sad dog. The clown on the left is pointing a revolver at the clown on the right, all while presenting a broad smirk; the clown on the right, holding a clarinet in his left hand, points to the left clown and wears an expression of comic disbelief. The incongruence of the clowns’ expressions in relation to the ludicrousness of the photographic narrative underscores the carnivalesque that is amplified by their grotesque appearance. The image stirs conflicting reactions of attraction and repulsion, wonder and alarm. It becomes the basis of the musical undertones of Curios in which one listens to enigmatic sonicities of strangeness. In the movement titled “Phantasmagoria,” the screened image of the three clowns becomes divided, distorted, disassembled, and at times reassembled to form psychedelic shapes and patterns resembling a kaleidoscope. This further engenders the distorted and the grotesque. In this imag(in)ing of the grotesque body, body parts are juxtaposed and con-/re-joined to amplify deformation and exaggeration in the same way that Bakhtin describes the bodily processes of eating, defecating, and copulating as aspects of the grotesque body ([1963] 1984:26).

Figure 2. “Kassino Clowns with Dog” (c. 1920) featured in “Phantasmagoria.” Photographer unknown. (Photo courtesy of Singapore International Festival of Arts)

The music in Curios is accompanied by video images that are interwoven to interact with the musical narrative. In a video projected above Tan during “Phantasmagoria,” the theatricalized grotesque clown bodies inter-play with the music that Tan plays on a toy grand piano and a toy psaltery, at times simultaneously with her left hand on the grand, her right on the psaltery. These grotesque bodies are “played” with and against the musicality as a means of evoking the phantasmagoric undercurrents and dark tonalities of the carnivalesque.

The strident frequencies from the sharp “twangs” of the psaltery when picked, heard alongside the harsh, metallic sounds of the toy piano, sustain the carnivalesque that has been established in the first movement. Early in “Phantasmagoria,” Tan taps alternately what are heard as the notes C and B-flat rapidly, in evolving tempos — from a slow strum and pluck of the psaltery to the quick taps of the keyboard. As the piece progresses, the notes B, F, and E-flat are plucked on the psaltery repeatedly; the psaltery’s tones clash with the toy piano’s and the distinct timbres of both instruments reify the collocation of difference and duality, creating an acoustic other space. “Phantasmagoria” is distinctly composed of the darker, ambiguous tonalities of the minor key.

The grotesque image of the clowns floating above comprises a colluding curiosity with the music, given the photograph’s aged, black-and-white façade. The peculiarity of the clowns’ costumes, makeup, and the dramatic contrasts of expressions and actions delight yet induce an accompanying abjection. The clowns metamorphose to the changing rhythms of the musical movement (even as these geometric transformations of the projected image do not always move synchronously with the evolving tempo). The movement is characterized by thematic circularity in which the melodic structures are repeated even as the notes vary. In the early segments of “Phantasmagoria,” Tan plays the toy piano with her left hand repeating the tonal pattern of B, F-flat, and E, with B as the tonic, established in a steady, broad, and slow tempo; her right hand plays variations of A, B, and D on the psaltery, at times moving to A, B, D, and E with the notes held approximately twice as long as the harmony on the toy piano. At this juncture, the black-and-white image of the three clowns fragments to resemble circular petal patterns that revolve in ways that correspond to the rhythm of the music. As the tempo increases, and the tonal pattern changes, the kaleidoscope of the clowns becomes further disassembled to form new circular patterns that revolve faster to parallel the increasing musical tension. In the subsequent section, as Tan picks on the strings of the psaltery in a repeated pattern of B, F, and E, followed by a strum across, the images, still those of the metamorphosed clowns, spin and “blossom” into new circular, revolving patterns.

Figure 3. Margaret Leng Tan playing the toy bowed psaltery and toy grand piano in “Phantasmagoria.” Curios, 2015. School of the Arts Studio Theatre, Singapore. (Photo courtesy of Singapore International Festival of Arts)

Distinctly, the artistic play of the grotesque clown images evidences how the theatricality of the visual image is impacted by the music. Furthermore, the sonic quality of the piece conjures its own sense of theatricality as the sounds of the toy piano here resemble those heard when a jack-in-the-box or music box is cranked. Like the forward spinning lever that produces the mechanical melody of a jack-in-the-box, the melodic structure of “Phantasmagoria” inspires images of revolution and circularity, and this is further adumbrated by the gyrating kaleidoscope of dismembered clowns orbiting above Tan. More significantly, the bodies of the clowns, disassembled and reassembled in new ways, advent a defamiliarization of the now familiar made (more) strange. This experience of ostranenie Footnote 4 is essential to the carnivalesque. In identifying yet distancing — of recognizing the bodies as clowns yet as “comic” figures estranged from the event depicted — the audience is led to reexamine everything seen and heard.

Figure 4. Margaret Leng Tan, wearing a mask inspired by the harlequin of the commedia dell’arte tradition, blows on a bird whistle, in the movement “Arlecchino.” Curios, 2015. School of the Arts Studio Theatre, Singapore. (Photo courtesy of Singapore International Festival of Arts)

The carnival grotesque is also evoked with the extensive use of masks. According to Bakhtin, masks in carnivals were a means of exaggerating the grotesque body by presenting asymmetrical and distorted faces. Masks are ancient instruments that are integral to carnival, suggesting the joys of disguise, mockery, change, death, and reincarnation. Highly theatrical, masks adumbrate the grotesque body’s duality of renewal and decay, birth and death. Masks reject conformity to oneself and to one’s nation or other affinities (Bakhtin [1965] 1984:39–40).

In Curios, masks reinscribe the music-performer as a theatrical character (or character type) in an obvious or implied dramatic narrative; they promote an ocular attention to reinforce (or contradict) aural attention. Masks shape the mode(s) of performance in the same way that masks transmogrify actors in Asian traditional dance-drama genres such as Japanese noh or Balinese topeng.

Tan wears three masks in Curios. In the first two movements, “March” and “Wunderkammer,” Tan wears an abstract angular monkey mask painted with straight vertical lines, and an enlarged nose. Next, in “Phantasmagoria,” Tan wears a large, orange paper lantern over her head. Apart from two eye holes, Tan’s head is completely ensconced in the lantern. The body of the performer here, like the Kassino clowns, appears strange and surreal, inspiring curiosity and dissociation. In the final movement, “Arlecchino,” Tan puts on a rubber yellow face mask, an adaptation of the commedia dell’arte harlequin with an exaggerated wide upper lip, a broad nose, and large cut-out eyes. The mask’s strangeness is augmented by a customized miniature cymbal (identical to a Tibetan hand cymbal or tingsha) fixed on its forehead, which Tan intermittently strikes.

“Arlecchino” is also, arguably, the most theatrimusical movement of the performance. It begins with Tan blowing into a bird whistle and playing custom-made instruments such as a cuckoo organ and a miniature toy pneumatic organ that produces a sound similar to that of a circus calliope. The organ is played along with the toy piano and the cymbal. Tan plays spiritedly on the cuckoo organ, toy piano, and bird whistle bringing harlequin’s comic character into the show. Sometimes she plays two instruments simultaneously, her left hand on the piano and her right on the organ. While the music is mostly in a fast lively tempo, Tan breaks the rhythm abruptly with an emphatic final chord. She raises her hands above the keyboards, makes a sound-tracing gesture following the contour of the sound (Jensenius et al. Reference Jensenius, Wanderley, Inge Godøy and Leman2010:24), blows on the whistle and pulls on the stick that releases the chirping sounds of the bird whistle, and taps the cymbal on her head with a stick that has the other half of the cymbal fastened to it.

The cymbal attached to the mask and the ways Tan exploits its theatrimusical potential illustrates how the mask, integral to the grotesque body, becomes metonymic of the work’s musical principles and artistic intent. Masks are inherently semiotic, inviting viewers to actively decode the meaning, regardless if the masks are abstract, representational, or iconic. They dislocate expectations; seemingly extraneous, mere playful interventions, they are actually integral to the piece.

The Cleft in the Quotidian

Curios’s cogent theatrimusical dramaturgy allows the performance to effectively exemplify and embody Bakhtin’s carnivalesque, opening a “cleft in the quotidian.” Theatrimusicality’s ability to create this cleft is most evident in the final scene, “Arlecchino.” Tan, with bird whistle in mouth and wearing the harlequin mask, ends “Arlecchino” sharply by lifting her hands and suspending them momentarily mid-air, in the kinespheric movement with which pianists end their performance, expecting applause. Such a gesture is regularly encountered in piano recitals. But here Tan herself, still in character, claps precipitously at the audience. The audience-performer role is reversed. The audience remains hesitant in their applause because they are uncertain if Tan’s clapping is meant to lead them to clap along or if this gesture is part of the performance. Shortly after applauding, Tan rises from her seated position, walks to center stage, blows on the bird whistle, then takes a bow. Despite the bow evidently signifying the end of the performance, there is only a tentative, delayed applause from the audience.

This incident exemplifies how Tan’s theatrimusicality conjures a cleft in the quotidian and subverts audience expectations of a concert performance. For Bakhtin, the carnival also permitted political possibilities among the common folk, a “utopian world in which anti-hierarchism, relativity of values, questioning of authority, openness, joyous anarchy, and the ridiculing of all dogmas hold sway, a world in which syncretism and a myriad of differing perspectives are permitted” (Lachmann et al. Reference Lachmann, Eshelman and Davis1988–1989:118). Like the medieval carnival, Curios was a space where artificial restrictions within the conventional concert experience were inverted and disrupted, where alternative and “unconventional” possibilities of performing and listening prevailed. While it can be said that Tan’s theatrimusicality is simply a continuation of the spirit of the avantgarde in the ways that audiences, as listeners, are challenged to reconceive their own aurality and understanding of music and sound, the spirit of Curios as carnival was only possible because of Tan’s theatrimusicality.

Tan refers to her theatrimusical technique as an art where “sound, choreography and drama [hold] equal significance” (Tan Reference Tan1988); she claims, “the composers love it when I add a dramatic dimension to what they originally envisioned as concert music” (Bakchormeeboy 2020). Theatrimusicality is so definitively her trademark that it is unsurprising the New Yorker magazine called her the “diva of avant-garde pianism” (1992:22). A mature example of Tan’s theatrimusicality is found in Dragon Ladies Don’t Weep (2020, 2021).Footnote 5 Her most recent work, Dragon Ladies, tells the poignant, intimate story of her own life as “Queen of the Toy Piano” (Tan Reference Tan2021). The show opens with Tan enthralling the audience on a Steinway with a piece by Erik Griswold (who composed the music for Dragon Ladies). The composition involves repeating musical structures, patterns, and notations. Near the end of the opening movement, Tan begins counting aloud. She stops playing the piano when she reaches 10 but continues counting. She then rises from the stool, moves to the right edge of the grand piano’s keyboard, and begins rotating the piano in a counterclockwise direction. The steady quiet grinding of the piano’s wheels on the stage floor creates a synchronous rhythm alongside Tan’s counting punctuated by her deep breaths. Tan finally stops spinning the Steinway when she reaches 75; she then tells the audience she is 75 years old this year (2021). This dramatic opening heralds her aural-biography, a “sonic theatrical equivalent of a written memoir” (in Esplanade 2021). In Dragon Ladies we learn how Tan has struggled with obsessive-compulsive disorder all her life, this condition manifesting as a need to count. In a later sequence, after Tan tells the audience that how she pronounced “one” as a child — dragging out “onnnneee” — became an early manifestation of the disorder in retrospect; she then plays a single chord on the toy piano as she chants “one.” The chord becomes a single note played repeatedly until the piece progresses as variations on this note and chord. Even when Tan stops playing, the music is repeated over the auditorium’s speakers — the live piano-playing was recorded and looped. In Dragon Ladies, the theatricality of Tan’s vocalized counting, the rotation of the grand piano, and the chord on the toy piano are metaphors and metonyms of Tan’s fixation on numbers and patterns. Like many other performances of Tan’s, Dragon Ladies exemplifies how theatricality and musicality are inseparable; from her professional playing on the grand piano to her performing in “unmusical” and unexpected ways on apparently nonmusical instruments.

Theatrimusicality engages the audience as both spectator and listener. One cannot just listen to Tan’s works; one needs to experience them in performance. Theatrimusicality invites a seeing inspired by listening and a listening motivated by seeing. Significantly, Tan’s approach to music-making expands and redefines approaches to theatre-making and facilitates a condition where the audience inhabits the cleft in the quotidian, the space of the clivage and breach within the everyday.