1. Introduction

In the last two decades, the research field of formal argumentation has gained an important role in Artificial Intelligence and especially in Knowledge Representation Atkinson et al. (Reference Atkinson, Baroni, Giacomin, Hunter, Prakken, Reed, Simari, Thimm and Villata2017). There are several reasons for this success story, in particular its wide range of applications such as non-monotonic reasoning, multi-agent systems and as an analysis tool for debates or dialogues (cf. Bench-Capon & Dunne Reference Bench-Capon and Dunne2007; Baroni et al. Reference Baroni, Gabbay, Giacomin and van der Torre2018b for more information). One can distinguish two major lines of research in the field, namely logic-based and abstract approaches. The former takes the underlying structure of arguments into account and defines notions like attack, undercut or defensibility in terms of logical properties of the chosen argument structures (Besnard et al. Reference Besnard, Garcia, Hunter, Modgil, Prakken, Simari and Toni2014). In contrast, abstract approaches abstract away from the internal structure of arguments and focus entirely on the relations between them. In the latter field, there is one leading formalism, namely abstract argumentation frameworks (AFs) introduced by Phan Minh Dung in 1995 (Dung Reference Dung1995). Dung-style AFs represent arguments as nodes and attacks as directed arcs. They are thus just directed graphs. The major focus is on resolving conflicts, or more precisely, on the question of how to determine acceptable positions. To this end a variety of semantics have been introduced, each of them specifying different criteria for being acceptable. One can distinguish three different families, namely semantics based on naivety, admissibility as well as weak admissibility (van der Torre & Vesic Reference van der Torre and Vesic2017; Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Brewka and Ulbricht2022).

From the 2010s onward dynamic aspects of abstract argumentation have become an important focus of research—which is hardly surprising, given that argumentation is an inherently dynamic process. One extensively studied problem in this context is the so-called enforcing problem. Enforcement is concerned with (minimal) syntactic manipulations of argumentation frameworks in such a way that a desired set of arguments becomes an extension (Baumann & Brewka Reference Baumann and Brewka2010; Baumann Reference Baumann2012; Wallner et al. Reference Wallner, Niskanen and Järvisalo2017; Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Doutre, Mailly and Wallner2021). Another important issue regarding dynamics is the topic of forgetting. Roughly speaking, forgetting deals with removing irrelevant arguments or hiding sensitive ones, while preserving as much as possible of the initial semantics. Several syntactical and semantical criteria have been proposed and analysed with respect to their combined satisfiability and possible implementations (Bisquert et al. Reference Bisquert, Cayrol, de Saint-Cyr and Lagasquie-Schiex2011; Eiter & Kern-Isberner Reference Eiter and Kern-Isberner2019; Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Gabbay and Rodrigues2020; Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Berthold, Gabbay and Rodrigues2025). In general, much of this work has been influenced by the famous AGM theory (Alchourrón et al. Reference Alchourrón, Gärdenfors and Makinson1985), the leading formal account of revision in the context of propositional logic. In general, belief revision deals with the problem of integrating new pieces of information to a current knowledge base. To this end—given a certain logical formalism

![]() ${{\mathcal{L}}}$

together with its semantics

${{\mathcal{L}}}$

together with its semantics

![]() $\sigma_{{{\mathcal{L}}}}$

—one is typically faced with the problem of modifying an

$\sigma_{{{\mathcal{L}}}}$

—one is typically faced with the problem of modifying an

![]() ${{\mathcal{L}}}$

-theory T in such a way that the revised version S satisfies

${{\mathcal{L}}}$

-theory T in such a way that the revised version S satisfies

![]() $\sigma_{{{\mathcal{L}}}}(S) = M$

for some model set M. Now, before trying to do this revision in a certain minimal way it is essential to know whether M is realizable at all.

$\sigma_{{{\mathcal{L}}}}(S) = M$

for some model set M. Now, before trying to do this revision in a certain minimal way it is essential to know whether M is realizable at all.

Realizability is a central task in knowledge representation and has been studied for many different formalisms. For instance, in case of propositional logic any finite set of two-valued interpretations is realizable. This means, for any finite set of interpretations

![]() $\mathcal{I}$

, we find a formula

$\mathcal{I}$

, we find a formula

![]() $\phi$

, s.t.

$\phi$

, s.t.

![]() $Mod(\phi) = {{\mathcal{I}}}$

. Differently, in case of normal logic programs under stable model semantics (Gelfond & Lifschitz Reference Gelfond and Lifschitz1988) we have that any finite candidate set is realizable if and only if it forms a

$Mod(\phi) = {{\mathcal{I}}}$

. Differently, in case of normal logic programs under stable model semantics (Gelfond & Lifschitz Reference Gelfond and Lifschitz1988) we have that any finite candidate set is realizable if and only if it forms a

![]() $\subseteq$

-antichain, that is any two sets of the candidate set have to be incomparable w.r.t. subset relation (Eiter et al. Reference Eiter, Fink, Pührer, Tompits and Woltran2013; Strass Reference Strass2015). Such characterizing properties may rule out a logic/semantics or make it perfectly appropriate for a certain application. The first formal treatment of realizability in abstract argumentation was given by Dunne et al. (Reference Dunne, Dvorák, Linsbichler, Woltran, Baral, Giacomo and Eiter2014, Reference Dunne, Dvorák, Linsbichler and Woltran2015). They coined the term signature for the set of all realizable sets of extensions. The authors provided simple criteria for several mature semantics deciding whether a set of extensions is contained in the corresponding signature. For instance, forming a

$\subseteq$

-antichain, that is any two sets of the candidate set have to be incomparable w.r.t. subset relation (Eiter et al. Reference Eiter, Fink, Pührer, Tompits and Woltran2013; Strass Reference Strass2015). Such characterizing properties may rule out a logic/semantics or make it perfectly appropriate for a certain application. The first formal treatment of realizability in abstract argumentation was given by Dunne et al. (Reference Dunne, Dvorák, Linsbichler, Woltran, Baral, Giacomo and Eiter2014, Reference Dunne, Dvorák, Linsbichler and Woltran2015). They coined the term signature for the set of all realizable sets of extensions. The authors provided simple criteria for several mature semantics deciding whether a set of extensions is contained in the corresponding signature. For instance, forming a

![]() $\subseteq$

-antichain is necessary for many mature semantics but not sufficient as in case of logic programming.

$\subseteq$

-antichain is necessary for many mature semantics but not sufficient as in case of logic programming.

In this article we convey the topic of realizability to the more informative labelling-based versions of argumenation semantics. It is important to note that existing characterization theorems for extension-based semantics are of little help in characterizing the corresponding labelling-based versions. This is due to the fact that the latter are more restrictive as they assign a status to any argument implying that the possible number of realizing frameworks is limited from the start. Moreover, they are more fine-grained as they explicitly distinguish two non-acceptance cases, namely rejected and undecided.

We mention that the presented article summarizes and combines recent results on the expressivness of conflict-free labellings (Baumann & Heine Reference Baumann and Heine2023) and naive labellings (Baumann & Heine Reference Baumann and Heine2024). In addition we provide full proofs and some first reflections on the realizability of stable labellings.

The article is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant background in argumentation theory. In Section 3, we present our results regarding conflict-free realizability. To that end, we introduce three new criteria, namely L-tightness, reject-witnessing and reject-compositionality. Moreover, we present a witnessing construction as well as our findings on equivalence and redundancy. Section 4 introduces the corresponding results for the naive labelling semantics. By establishing the construction of a labellings-downward-closure we attain a characterization through the connection to the conflict-free labellings. Section 5 provides an outlook on the realizability of stable labellings. Lastly, Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future work.

2. Formal preliminaries

2.1. Argumentation frameworks and semantics

We start with the necessary background on abstract argumentation. An argumentation framework (AF) is a pair

![]() ${F} = (A,R)$

where A, the set of arguments, is a finite subset of a fixed infinite background set

${F} = (A,R)$

where A, the set of arguments, is a finite subset of a fixed infinite background set

![]() ${{\mathcal{U}}}$

, and

${{\mathcal{U}}}$

, and

![]() $R \subseteq A \times A$

. The set of all finite AFs is denoted by

$R \subseteq A \times A$

. The set of all finite AFs is denoted by

![]() ${{\mathcal{F}}}$

(cf. Baumann & Spanring Reference Baumann and Spanring2015, Reference Baumann and Spanring2017 for a treatment of infinite AFs). We say a attacks b, or b is defeated by a in

${{\mathcal{F}}}$

(cf. Baumann & Spanring Reference Baumann and Spanring2015, Reference Baumann and Spanring2017 for a treatment of infinite AFs). We say a attacks b, or b is defeated by a in

![]() ${F}$

whenever

${F}$

whenever

![]() $(a,b)\in R$

. For a set

$(a,b)\in R$

. For a set

![]() ${E}\subseteq A$

we use

${E}\subseteq A$

we use

![]() $R^+_{{F}}({E})$

or simply,

$R^+_{{F}}({E})$

or simply,

![]() ${E}^+$

for

${E}^+$

for

![]() $\{b\mid (a,b)\in R, a\in {E}\}$

. Moreover,

$\{b\mid (a,b)\in R, a\in {E}\}$

. Moreover,

![]() $E^\oplus_{F}$

or just

$E^\oplus_{F}$

or just

![]() $E^\oplus$

, is called the range of E and stands for

$E^\oplus$

, is called the range of E and stands for

![]() $E\cup E^+$

. If

$E\cup E^+$

. If

![]() ${G} = (B,S)$

, we use

${G} = (B,S)$

, we use

![]() $A({G})$

as well as

$A({G})$

as well as

![]() $R({G})$

to refer to the first or second component of

$R({G})$

to refer to the first or second component of

![]() ${G}$

, that is B or S, respectively.

${G}$

, that is B or S, respectively.

An extension-based semantics

![]() ${{\mathcal{E}}}_{\sigma}\;:\;{{\mathcal{F}}}\rightarrow 2^{2^{{\mathcal{U}}}}$

is a function which assigns to any AF

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{\sigma}\;:\;{{\mathcal{F}}}\rightarrow 2^{2^{{\mathcal{U}}}}$

is a function which assigns to any AF

![]() ${F}=(A,R)$

a set of sets of arguments denoted by

${F}=(A,R)$

a set of sets of arguments denoted by

![]() ${{\mathcal{E}}}_{\sigma}({F})\subseteq 2^A$

. Each one of them, a so-called

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{\sigma}({F})\subseteq 2^A$

. Each one of them, a so-called

![]() $\sigma$

-extension, is considered to be acceptable with respect to

$\sigma$

-extension, is considered to be acceptable with respect to

![]() ${F}$

. The most basic criteria is conflict-freeness (

${F}$

. The most basic criteria is conflict-freeness (

![]() ${cf}$

) which guarantees no internal conflicts. Furthermore, we consider a

${cf}$

) which guarantees no internal conflicts. Furthermore, we consider a

![]() $\subseteq$

-maximal version of conflict-freeness, so-called naive semantics (

$\subseteq$

-maximal version of conflict-freeness, so-called naive semantics (

![]() ${na}$

) which can be seen as an upper bound for the widely known stable semantics (

${na}$

) which can be seen as an upper bound for the widely known stable semantics (

![]() ${{stb}}$

).

${{stb}}$

).

Definition 1 Let

![]() ${F} = (A,R)$

be an AF and

${F} = (A,R)$

be an AF and

![]() ${E}\subseteq A$

.

${E}\subseteq A$

.

-

1.

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

iff there are no

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

iff there are no

$a,b\in A$

, s.t.

$a,b\in A$

, s.t.

$(a,b)\in R$

,

$(a,b)\in R$

, -

2.

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{na}}({F})$

iff E is

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{na}}({F})$

iff E is

$\subseteq$

-maximal in

$\subseteq$

-maximal in

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

,

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

, -

3.

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})$

iff

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})$

iff

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

and

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

and

$E^+ = A\setminus E$

.

$E^+ = A\setminus E$

.

A labelling-based semantics

![]() ${{\mathcal{L}}}_{\sigma}\;:\;{{\mathcal{F}}}\rightarrow 2^{\left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^3}$

is a function which assigns to any AF

${{\mathcal{L}}}_{\sigma}\;:\;{{\mathcal{F}}}\rightarrow 2^{\left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^3}$

is a function which assigns to any AF

![]() ${F}=(A,R)$

a set of triples of sets of arguments denoted by

${F}=(A,R)$

a set of triples of sets of arguments denoted by

![]() ${{\mathcal{L}}}_{\sigma}({F})\subseteq \left(2^A\right)^3$

. Each one of them, a so-called

${{\mathcal{L}}}_{\sigma}({F})\subseteq \left(2^A\right)^3$

. Each one of them, a so-called

![]() $\sigma$

-labelling of

$\sigma$

-labelling of

![]() ${F}$

, is a triple

${F}$

, is a triple

![]() ${L} = (I,O,U)$

indicating that arguments in I, O or U are considered to be accepted (in), rejected (out) or undecided with respect to

${L} = (I,O,U)$

indicating that arguments in I, O or U are considered to be accepted (in), rejected (out) or undecided with respect to

![]() ${F}$

. We further assume pairwise disjointness and covering, that is

${F}$

. We further assume pairwise disjointness and covering, that is

![]() $I\cap O = I\cap U = O \cap U = \emptyset$

and

$I\cap O = I\cap U = O \cap U = \emptyset$

and

![]() $I \cup O \cup U = A$

. We use

$I \cup O \cup U = A$

. We use

![]() ${L}^{\text{I}}$

(or

${L}^{\text{I}}$

(or

![]() ${L}^{\text{I}}(a)$

) to refer to (a is an element of) the first component of the labelling

${L}^{\text{I}}(a)$

) to refer to (a is an element of) the first component of the labelling

![]() ${L}$

. Analogously for

${L}$

. Analogously for

![]() ${L}^{\text{O}}$

and

${L}^{\text{O}}$

and

![]() ${L}^{\text{U}}$

. We proceed with the central notions of conflict-free labellings (Caminada Reference Caminada2011; Arieli Reference Arieli2012).

${L}^{\text{U}}$

. We proceed with the central notions of conflict-free labellings (Caminada Reference Caminada2011; Arieli Reference Arieli2012).

Definition 2 A labelling

![]() ${L}$

of

${L}$

of

![]() ${F}=(A,R)$

is called conflict-free if we have:

${F}=(A,R)$

is called conflict-free if we have:

-

1. If

$a,b\in {L}^{\text{I}}$

, then

$a,b\in {L}^{\text{I}}$

, then

$(a,b)\notin R$

, and (no internal conflicts)

$(a,b)\notin R$

, and (no internal conflicts) -

2. If

$a\in {L}^{\text{O}}$

, then there is a

$a\in {L}^{\text{O}}$

, then there is a

$b\in{L}^{\text{I}}$

with

$b\in{L}^{\text{I}}$

with

$(b,a)\in R$

. (reason for rejecting)

$(b,a)\in R$

. (reason for rejecting)

We now introduce the labelling-based counterparts to the extension-based semantics.

Definition 3 Let

![]() ${F} = (A,R)$

be an AF and

${F} = (A,R)$

be an AF and

![]() ${L}\in\left(2^A\right)^3$

a labelling of

${L}\in\left(2^A\right)^3$

a labelling of

![]() ${F}$

.

${F}$

.

-

1.

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

iff

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

iff

${L}$

is a conflict-free labelling of

${L}$

is a conflict-free labelling of

${F}$

,

${F}$

, -

2.

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{na}}({F})$

iff

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{na}}({F})$

iff

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

and

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

and

${L}^{\text{I}}$

is

${L}^{\text{I}}$

is

$\subseteq$

-maximal in

$\subseteq$

-maximal in

$\{{M}^{\text{I}}\mid M\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})\}$

,

$\{{M}^{\text{I}}\mid M\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})\}$

, -

3.

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})$

iff

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})$

iff

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

and

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

and

${L}^{\text{U}} = \emptyset$

.

${L}^{\text{U}} = \emptyset$

.

We mention that conflict-free sets and naive semantics are universally defined, that is they always provide one with acceptable sets or labellings, respectively. This assertion does not hold for stable semantics.

Let us proceed with an illustrating example.

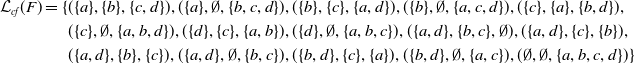

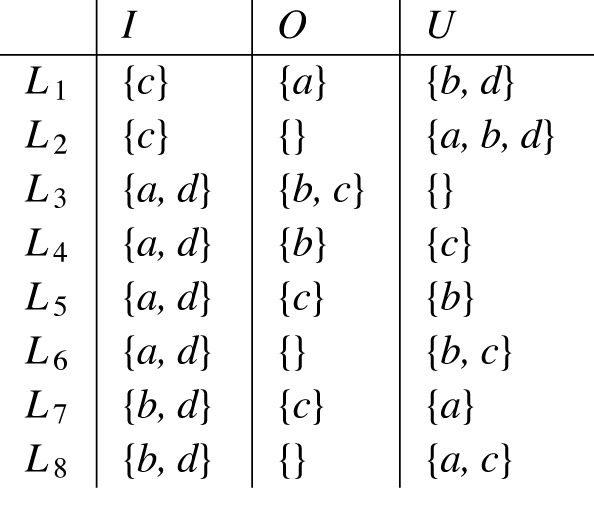

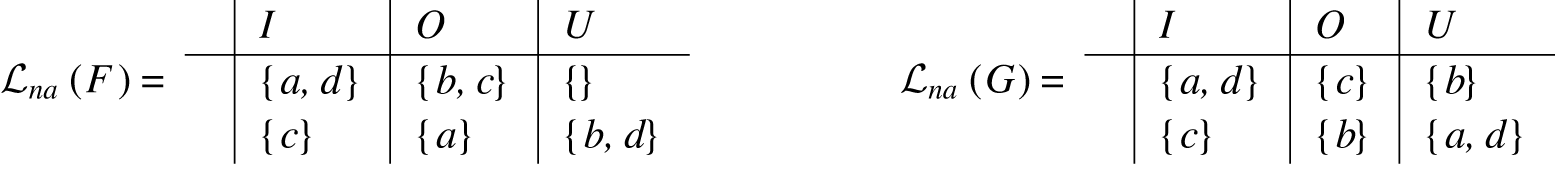

Example 1 Consider the following AF

![]() ${F}$

. The introduced extension-based semantics together with its labelling-based counterparts are given below.

${F}$

. The introduced extension-based semantics together with its labelling-based counterparts are given below.

-

•

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F}) =\{\{ a\}, \{b\}, \{c\}, \{d\},\{a,d\}, \{b,d\}, \emptyset \} $

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F}) =\{\{ a\}, \{b\}, \{c\}, \{d\},\{a,d\}, \{b,d\}, \emptyset \} $

-

•

$\begin{aligned}[t] {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F}) = \{ &(\{ a\}, \{b \}, \{ c,d\}), (\{ a\}, \emptyset, \{ b,c,d\}), (\{ b\}, \{c \}, \{ a,d\}), (\{ b\}, \emptyset, \{a,c,d\}), ( \{c\} , \{a\}, \{b,d\}), \\ &( \{c\} ,\emptyset , \{a,b,d\}), ( \{d\} , \{c\}, \{a,b\}),( \{d\} , \emptyset, \{a,b,c\}), ( \{a,d\} , \{b,c\}, \emptyset) , ( \{a,d\} , \{c\}, \{b\}), \\ &( \{a,d\} , \{b\}, \{c\}), ( \{a,d\} , \emptyset, \{b,c\}), ( \{b,d\} , \{c\},\{a\}), ( \{b,d\} , \emptyset, \{a,c\}) , ( \emptyset , \emptyset, \{a,b,c,d\})\} \end{aligned}$

$\begin{aligned}[t] {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F}) = \{ &(\{ a\}, \{b \}, \{ c,d\}), (\{ a\}, \emptyset, \{ b,c,d\}), (\{ b\}, \{c \}, \{ a,d\}), (\{ b\}, \emptyset, \{a,c,d\}), ( \{c\} , \{a\}, \{b,d\}), \\ &( \{c\} ,\emptyset , \{a,b,d\}), ( \{d\} , \{c\}, \{a,b\}),( \{d\} , \emptyset, \{a,b,c\}), ( \{a,d\} , \{b,c\}, \emptyset) , ( \{a,d\} , \{c\}, \{b\}), \\ &( \{a,d\} , \{b\}, \{c\}), ( \{a,d\} , \emptyset, \{b,c\}), ( \{b,d\} , \{c\},\{a\}), ( \{b,d\} , \emptyset, \{a,c\}) , ( \emptyset , \emptyset, \{a,b,c,d\})\} \end{aligned}$

-

•

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{na}}({F}) =\{\{c\},\{a,d\}, \{b,d\} \} $

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{na}}({F}) =\{\{c\},\{a,d\}, \{b,d\} \} $

-

•

$\begin{aligned}[t] {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{na}}({F}) = \{ &( \{c\} , \{a\}, \{b,d\}),(\{c\} ,\emptyset , \{a,b,d\}), ( \{a,d\} , \{b,c\}, \emptyset) , ( \{a,d\} , \{c\}, \{b\}), ( \{a,d\} , \{b\}, \{c\}),\\ &( \{a,d\} , \emptyset, \{b,c\}), ( \{b,d\} , \{c\},\{a\}), ( \{b,d\} , \emptyset, \{a,c\}) \} \end{aligned}$

$\begin{aligned}[t] {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{na}}({F}) = \{ &( \{c\} , \{a\}, \{b,d\}),(\{c\} ,\emptyset , \{a,b,d\}), ( \{a,d\} , \{b,c\}, \emptyset) , ( \{a,d\} , \{c\}, \{b\}), ( \{a,d\} , \{b\}, \{c\}),\\ &( \{a,d\} , \emptyset, \{b,c\}), ( \{b,d\} , \{c\},\{a\}), ( \{b,d\} , \emptyset, \{a,c\}) \} \end{aligned}$

-

•

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}({F}) = \{\{a,d\}\}$

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}({F}) = \{\{a,d\}\}$

-

•

${{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F}) = \{(\{a,d\},\{b,c\},\emptyset)\}$

${{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F}) = \{(\{a,d\},\{b,c\},\emptyset)\}$

Please observe that apart from stable semantics we do not have a match between the numbers of conflict-free/naive extensions and conflict-free/naive labellings. This observation is essential and one reason why realizability results for extension-based semantics do not directly carry over to their labelling-based counterparts.

In the following we list some well-known properties and relations between semantics which will be frequently used throughout the whole paper. For more details and explanations please confer (Baumann Reference Baumann2016; Baroni et al. Reference Baroni, Caminada, Giacomin, Baroni, Gabbay, Giacomin and van der Torre2018a).

Proposition 1 Given an AF

![]() ${F} = (A,R)$

, a set

${F} = (A,R)$

, a set

![]() $E\subseteq A$

and a semantics

$E\subseteq A$

and a semantics

![]() $\sigma\in\{{cf},{na},{{stb}}\}$

. In the following we use

$\sigma\in\{{cf},{na},{{stb}}\}$

. In the following we use

![]() $E^{{{\mathcal{L}}}}$

as shorthand for

$E^{{{\mathcal{L}}}}$

as shorthand for

![]() $(E,E^+,A\setminus(E\cup E^+))$

.

$(E,E^+,A\setminus(E\cup E^+))$

.

-

1.

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})\subseteq{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{na}}({F})\subseteq{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

,

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})\subseteq{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{na}}({F})\subseteq{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

, -

2.

${{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})\subseteq{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{na}}({F})\subseteq{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

,

${{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})\subseteq{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{na}}({F})\subseteq{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

, -

3. If

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{\sigma}({F})$

, then

${E}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{\sigma}({F})$

, then

${E}^{{{\mathcal{L}}}}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{\sigma}({F})$

,

${E}^{{{\mathcal{L}}}}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{\sigma}({F})$

, -

4. If

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{\sigma}({F})$

, then

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{\sigma}({F})$

, then

${L}^{\text{I}}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{\sigma}({F})$

, and

${L}^{\text{I}}\in{{\mathcal{E}}}_{\sigma}({F})$

, and -

5. Obviously,

$(E^{{{\mathcal{L}}}})^I = E$

.

$(E^{{{\mathcal{L}}}})^I = E$

.

In case of stable semantics we even have the following additional relations:

-

1. For any

${L},{M}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F}), {L}^{\text{I}} = {M}^{\text{I}}$

iff

${L},{M}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F}), {L}^{\text{I}} = {M}^{\text{I}}$

iff

${L} = {M}$

,

${L} = {M}$

, -

2. Given

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})$

, then

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})$

, then

$({L}^{\text{I}})^{{{\mathcal{L}}}} = {L}$

, and

$({L}^{\text{I}})^{{{\mathcal{L}}}} = {L}$

, and -

3.

$\left\lvert{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})\right\rvert = \left\lvert{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})\right\rvert$

.

$\left\lvert{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})\right\rvert = \left\lvert{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}({F})\right\rvert$

.

We encourage the reader to verify the presented relations using Example 1.

2.2. Equivalence notions

Representational freedom is highly connected with patterns of redundancy. In particular, we want to study whether and to which extent it is possible to syntactically change a given AF without changing its current semantics, so-called ordinary equivalence as well as changes which do not affect any future expansion, so-called strong equivalence (Oikarinen & Woltran Reference Oikarinen and Woltran2011; Baumann Reference Baumann2016, Reference Baumann2018).

Consider the following formal definition of the weaker version of equivalence.

Definition 4 Given a semantics

![]() $X\in\{{{\mathcal{E}}}_\sigma,{{\mathcal{L}}}_\sigma\}$

and two AFs

$X\in\{{{\mathcal{E}}}_\sigma,{{\mathcal{L}}}_\sigma\}$

and two AFs

![]() ${F}$

and

${F}$

and

![]() ${G}$

.

${G}$

.

![]() ${F}$

and

${F}$

and

![]() ${G}$

are called ordinarily equivalent if

${G}$

are called ordinarily equivalent if

![]() $X({F}) = X({G})$

. We use

$X({F}) = X({G})$

. We use

![]() ${F}\equiv^X\!{G}$

to indicate this relation.

${F}\equiv^X\!{G}$

to indicate this relation.

We mention one decisive difference between the two versions of semantics. In contrast to extension-based semantics, being ordinarily equivalent in the realm of labellings requires to share the same arguments. This is due to the fact that each labelling assigns a label to any argument of the considered AF implying that labellings are necessarily different if the frameworks in question possess different arguments. The following example illustrate this observation.

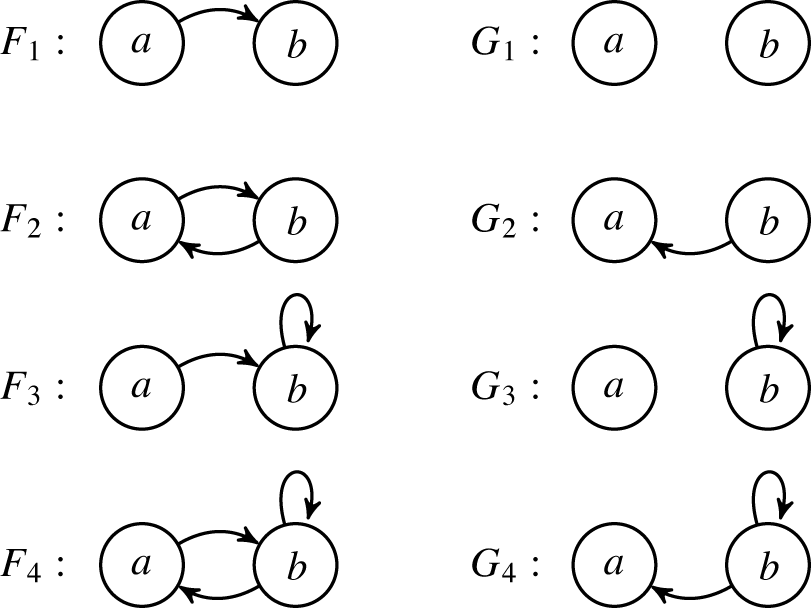

Example 2 Compare the following basic AFs F, G and H:

For all three frameworks we get the same conflict-free extension, namely the set

![]() $\{a\}$

. However the conflict-free labelling differs for each AF. While the in-sets still concide, they comverge in terms of the out-, and undec-set:

$\{a\}$

. However the conflict-free labelling differs for each AF. While the in-sets still concide, they comverge in terms of the out-, and undec-set:

![]() $\mathcal L(cf)(F)=\{(\{a\}, \{\}, \{\})\}$

,

$\mathcal L(cf)(F)=\{(\{a\}, \{\}, \{\})\}$

,

![]() $\mathcal L(cf)(G)=\{(\{a\}, \{\}, \{b\})\}$

,

$\mathcal L(cf)(G)=\{(\{a\}, \{\}, \{b\})\}$

,

![]() $\mathcal L(cf)(H)=\{(\{a\}, \{b\}, \{\})\}$

.

$\mathcal L(cf)(H)=\{(\{a\}, \{b\}, \{\})\}$

.

We now introduce the formal definition of strong equivalence. To this end we use the notation

![]() $F\sqcup G$

to represent the union AF

$F\sqcup G$

to represent the union AF

![]() $(A_1 \cup A_2 , R_1\cup R_2)$

of the AFs

$(A_1 \cup A_2 , R_1\cup R_2)$

of the AFs

![]() $F=(A_1, R_1)$

and

$F=(A_1, R_1)$

and

![]() $G=(A_2, R_2)$

.

$G=(A_2, R_2)$

.

Definition 5 Given a semantics

![]() $X\in\{{{\mathcal{E}}}_\sigma,{{\mathcal{L}}}_\sigma\}$

and two AFs

$X\in\{{{\mathcal{E}}}_\sigma,{{\mathcal{L}}}_\sigma\}$

and two AFs

![]() ${F}$

and

${F}$

and

![]() ${G}$

.

${G}$

.

![]() ${F}$

and

${F}$

and

![]() ${G}$

are called strongly equivalent if for each AF

${G}$

are called strongly equivalent if for each AF

![]() ${H}$

,

${H}$

,

![]() $X({F}\sqcup{H}) = X({G}\sqcup{H})$

. We use

$X({F}\sqcup{H}) = X({G}\sqcup{H})$

. We use

![]() ${F}\equiv^X_s\!{G}$

to indicate this relation.

${F}\equiv^X_s\!{G}$

to indicate this relation.

It was shown that in order to decide strong equivalence for extension-based semantics one may use a syntactical concept called kernels (Oikarinen & Woltran Reference Oikarinen and Woltran2011). A kernel is again a directed graph obtained from the initial AF via adding or deleting attacks. It represents a distinguished object in the associated strong equivalence class (cf. Baumann Reference Baumann2018 for more details) In the following we introduce two well-known versions of kernels, namely the stable kernel as well as naive kernel.

Definition 6 Let

![]() $F = (A,R)$

be an AF. The stable and naive kernels of F are defined as:

$F = (A,R)$

be an AF. The stable and naive kernels of F are defined as:

-

1.

${F}^{sk} = (A^{sk},R^{sk}) = (A,R\setminus \{(a,b)\in R\mid a\neq b, (a,a)\in R\})$

and

${F}^{sk} = (A^{sk},R^{sk}) = (A,R\setminus \{(a,b)\in R\mid a\neq b, (a,a)\in R\})$

and -

2.

${F}^{nk} = (A^{nk},R^{nk}) = (A,R\cup \{(a,b)\in R\mid a\neq b, \{(a,a), (b,a), (b,b)\} \cap R \neq \emptyset\})$

${F}^{nk} = (A^{nk},R^{nk}) = (A,R\cup \{(a,b)\in R\mid a\neq b, \{(a,a), (b,a), (b,b)\} \cap R \neq \emptyset\})$

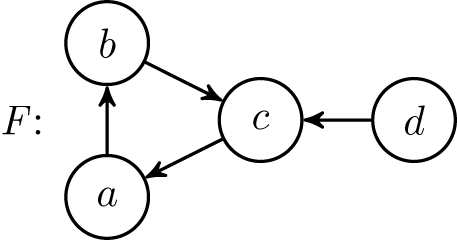

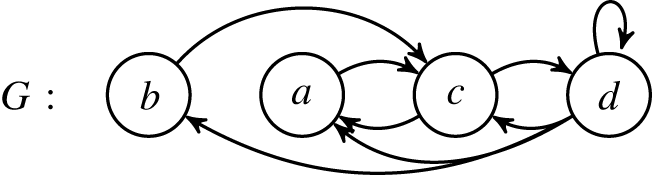

Example 3 Consider a slight modification of the AF from Example 1.

Using Definition 6 we built the stable and naive kernel of F.

The following properties are well-known and will be used to simplify proofs.

Proposition 2 Given an AF

![]() $F = (A,R)$

, we have

$F = (A,R)$

, we have

-

1.

$A = A^{sk} = A^{nk}$

$A = A^{sk} = A^{nk}$

-

2.

$R^{sk} \subseteq R \subseteq R^{nk}$

$R^{sk} \subseteq R \subseteq R^{nk}$

-

3.

$R, R^{sk}, R^{nk}$

share the same self-loops

$R, R^{sk}, R^{nk}$

share the same self-loops -

4. If F is selfloop-free, then

$F = {F}^{sk}$

.

$F = {F}^{sk}$

. -

5.

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{stb}}({F}) = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{stb}}({F}^{sk})$

and

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{{stb}}({F}) = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{stb}}({F}^{sk})$

and

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{na}({F}) = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{stb}}({F}^{nk})$

${{\mathcal{E}}}_{na}({F}) = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{stb}}({F}^{nk})$

Finally, for two AFs

![]() ${F}$

and

${F}$

and

![]() ${G}$

and kernel

${G}$

and kernel

![]() ${k}\in\{sk,nk\}$

we have:

${k}\in\{sk,nk\}$

we have:

6. If

![]() ${F}^{{k}} = {G}^{{k}}$

, then

${F}^{{k}} = {G}^{{k}}$

, then

![]() $\left({F}\sqcup {H}\right)^{{k}} = \left({G}\sqcup {H}\right)^{{k}}$

for any AF H.

$\left({F}\sqcup {H}\right)^{{k}} = \left({G}\sqcup {H}\right)^{{k}}$

for any AF H.

Now the central characterization theorems for the extension-based versions.

Proposition 3 Given two AFs F and G we have:

-

1.

$F\equiv^{\mathcal E_{stb}}_s G$

$F\equiv^{\mathcal E_{stb}}_s G$

$\Leftrightarrow$

$\Leftrightarrow$

$F^{sk}=G^{sk}$

$F^{sk}=G^{sk}$

-

2.

$F\equiv^{\mathcal E_{na}}_s G$

$F\equiv^{\mathcal E_{na}}_s G$

$\Leftrightarrow$

$\Leftrightarrow$

$F^{nk}=G^{nk}$

$F^{nk}=G^{nk}$

Please remember that we deal with finite AFs. A consideration of unrestricted AFs can be found in Baumann and Spanring (Reference Baumann and Spanring2017).

2.3. Realizability in abstract argumentation

The first formal treatment of expressibility issues in abstract argumentation was given by Dunne et al. (Reference Dunne, Dvorák, Linsbichler, Woltran, Baral, Giacomo and Eiter2014, Reference Dunne, Dvorák, Linsbichler and Woltran2015). They considered extension-based semantics and provided simple criteria for several mature semantics deciding whether a certain set of sets of arguments can be the semantical outcome of a framework.

Let us start with the two central concepts, namely realizability as well as signature. In a nutshell, we say that a certain set

![]() $\mathbb{S}$

is realizable under the semantics

$\mathbb{S}$

is realizable under the semantics

![]() $\sigma$

, if there is an AF

$\sigma$

, if there is an AF

![]() ${F}$

such that its set of

${F}$

such that its set of

![]() $\sigma$

-extensions/

$\sigma$

-extensions/

![]() $\sigma$

-labellings coincides with

$\sigma$

-labellings coincides with

![]() $\mathbb{S}$

. Collecting all realizable sets defines the concept of a signature. Consider the following formal definition of realizability in the context of abstract argumentation. Note that only

$\mathbb{S}$

. Collecting all realizable sets defines the concept of a signature. Consider the following formal definition of realizability in the context of abstract argumentation. Note that only

![]() $n=1$

(extension-case) and

$n=1$

(extension-case) and

![]() $n=3$

(labelling-case) will be relevant for this paper.

$n=3$

(labelling-case) will be relevant for this paper.

Definition 7 Given a semantics

![]() $\sigma\;:\; {{\mathcal{F}}}\rightarrow 2^{\left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^n}$

. A set

$\sigma\;:\; {{\mathcal{F}}}\rightarrow 2^{\left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^n}$

. A set

![]() $\mathbb{S}\subseteq \left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^n$

is

$\mathbb{S}\subseteq \left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^n$

is

![]() $\sigma$

-realizable if there is an AF

$\sigma$

-realizable if there is an AF

![]() ${F}\in{{\mathcal{F}}}$

, s.t.

${F}\in{{\mathcal{F}}}$

, s.t.

![]() $\sigma({F})=\mathbb{S}$

. Moreover, the

$\sigma({F})=\mathbb{S}$

. Moreover, the

![]() $\sigma$

-signature is defined as

$\sigma$

-signature is defined as

![]() $\Sigma_{\sigma} = \left\{\sigma({F}) \mid {F}\in{{\mathcal{F}}} \right\}$

.

$\Sigma_{\sigma} = \left\{\sigma({F}) \mid {F}\in{{\mathcal{F}}} \right\}$

.

2.3.1. Extension-based semantics

We proceed with further notation as well as the central notions of downward-closedness and tightness (Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Dvorák, Linsbichler and Woltran2015).

Definition 8 A finite

![]() $\mathbb{S} \subseteq 2^{{\mathcal{U}}}$

is called extension-set. We use

$\mathbb{S} \subseteq 2^{{\mathcal{U}}}$

is called extension-set. We use

-

•

${Args}_\mathbb{S}$

to denote

${Args}_\mathbb{S}$

to denote

$\bigcup_{S\in\mathbb{S}} S$

and

$\bigcup_{S\in\mathbb{S}} S$

and

$\left\lvert\mathbb{S}\right\rvert$

for

$\left\lvert\mathbb{S}\right\rvert$

for

$\left\lvert{Args}_\mathbb{S}\right\rvert$

,

$\left\lvert{Args}_\mathbb{S}\right\rvert$

, -

•

$\textit{Pairs}_\mathbb{S}$

to denote

$\textit{Pairs}_\mathbb{S}$

to denote

$\{ (a,b) \mid \exists S\in \mathbb{S}\;:\; \{a,b\}\subseteq S\}$

and

$\{ (a,b) \mid \exists S\in \mathbb{S}\;:\; \{a,b\}\subseteq S\}$

and -

•

$\textit{dcl}(\mathbb{S})$

to denote (the so-called downward-closure)

$\textit{dcl}(\mathbb{S})$

to denote (the so-called downward-closure)

$\{S' \subseteq S \mid S \in \mathbb{S}\}$

$\{S' \subseteq S \mid S \in \mathbb{S}\}$

In order to familiarize the reader with the introduced definitions we give the following example.

Example 4 Let

![]() $\mathbb{S} = \{\{a,d\},\{b,d\},\{c\}\}$

. Then

$\mathbb{S} = \{\{a,d\},\{b,d\},\{c\}\}$

. Then

-

•

${Args}_\mathbb{S} = \{a,b,c,d\}$

and

${Args}_\mathbb{S} = \{a,b,c,d\}$

and

$\left\lvert\mathbb{S}\right\rvert = 4$

,

$\left\lvert\mathbb{S}\right\rvert = 4$

, -

•

$\textit{Pairs}_\mathbb{S} = \{(a,a),(b,b),(c,c),(d,d),(a,d),(b,d)\} \cup \{(d,a),(d,b)\}$

, and

$\textit{Pairs}_\mathbb{S} = \{(a,a),(b,b),(c,c),(d,d),(a,d),(b,d)\} \cup \{(d,a),(d,b)\}$

, and -

•

$\textit{dcl}(\mathbb{S}) = \{\emptyset,\{a\},\{b\},\{c\},\{d\},\{a,d\},\{b,d\}\}$

.

$\textit{dcl}(\mathbb{S}) = \{\emptyset,\{a\},\{b\},\{c\},\{d\},\{a,d\},\{b,d\}\}$

.

Definition 9 Given an extension-set

![]() $\mathbb{S} \subseteq 2^{{\mathcal{U}}}$

. We call

$\mathbb{S} \subseteq 2^{{\mathcal{U}}}$

. We call

![]() $\mathbb{S}$

$\mathbb{S}$

-

• downward-closed if

$\mathbb{S}=\textit{dcl}(\mathbb{S})$

,

$\mathbb{S}=\textit{dcl}(\mathbb{S})$

, -

• incomparable if

$\mathbb{S}$

is a

$\mathbb{S}$

is a

$\subseteq$

-antichain that is for any

$\subseteq$

-antichain that is for any

$E_1,E_2\in \mathbb{S}$

we have: If

$E_1,E_2\in \mathbb{S}$

we have: If

$E_1\subseteq E_2$

, then

$E_1\subseteq E_2$

, then

$E_1 = E_2$

,

$E_1 = E_2$

, -

• tight if for all

$S \in \mathbb{S}$

and

$S \in \mathbb{S}$

and

$a \in {Args}_\mathbb{S}$

it holds that if

$a \in {Args}_\mathbb{S}$

it holds that if

$S \cup \{a\} \notin \mathbb{S}$

then there exists an

$S \cup \{a\} \notin \mathbb{S}$

then there exists an

$s \in S$

such that

$s \in S$

such that

$(a,s) \notin \textit{Pairs}_\mathbb{S}$

.

$(a,s) \notin \textit{Pairs}_\mathbb{S}$

.

Example 5 Consider again the extension-set

![]() $\mathbb{S}$

given in Example 4.

$\mathbb{S}$

given in Example 4.

-

• Obviously,

$\textit{dcl}(\mathbb{S})\neq \mathbb{S}$

. Hence,

$\textit{dcl}(\mathbb{S})\neq \mathbb{S}$

. Hence,

$\mathbb{S}$

is not downward-closed,

$\mathbb{S}$

is not downward-closed, -

•

$\mathbb{S}$

is incomparable as there are no proper subset relations.

$\mathbb{S}$

is incomparable as there are no proper subset relations. -

•

$\mathbb{S}$

is tight. To exemplify we consider

$\mathbb{S}$

is tight. To exemplify we consider

$S = \{b,d\}$

and

$S = \{b,d\}$

and

$S\cup\{a\}$

. We have

$S\cup\{a\}$

. We have

$S\cup\{a\}\notin\mathbb{S}$

and moreover, for the argument

$S\cup\{a\}\notin\mathbb{S}$

and moreover, for the argument

$b\in\mathbb{S}$

we deduce

$b\in\mathbb{S}$

we deduce

$(a,b)\notin \textit{Pairs}_\mathbb{S}$

.

$(a,b)\notin \textit{Pairs}_\mathbb{S}$

.

Now, we present the central characterization theorems in case of extension-based semantics (Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Dvorák, Linsbichler and Woltran2015).

Theorem 1 Given a finite extension-set

![]() $\mathbb{S} \subseteq 2^{{\mathcal{U}}}$

, then

$\mathbb{S} \subseteq 2^{{\mathcal{U}}}$

, then

-

1.

$\mathbb{S}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}} \Leftrightarrow \mathbb{S} \text{ is a non-empty, downward-closed, and tight extension-set,}$

$\mathbb{S}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}} \Leftrightarrow \mathbb{S} \text{ is a non-empty, downward-closed, and tight extension-set,}$

-

2.

$\mathbb{S}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{na}}} \Leftrightarrow \mathbb{S} \text{ is a non-empty, incomparable extension-set and } \textit{dcl}{(\mathbb{S})} \text{ is tight},$

$\mathbb{S}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{na}}} \Leftrightarrow \mathbb{S} \text{ is a non-empty, incomparable extension-set and } \textit{dcl}{(\mathbb{S})} \text{ is tight},$

-

3.

$\mathbb{S}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}} \Leftrightarrow \mathbb{S} \text{ is an incomparable and tight extension-set.}$

$\mathbb{S}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{{stb}}}} \Leftrightarrow \mathbb{S} \text{ is an incomparable and tight extension-set.}$

2.3.2. Labelling-based semantics

Now let us turn to labelling-based semantics. Again, we start with some relevant notations and shorthands. Moreover, we introduce the central concept of a labelling-set.

Definition 10 Given a finite set

![]() $\mathbb{L} \subseteq \left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^3$

. We use

$\mathbb{L} \subseteq \left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^3$

. We use

-

•

$\mathbb{L}^I$

,

$\mathbb{L}^I$

,

$\mathbb{L}^O$

and

$\mathbb{L}^O$

and

$\mathbb{L}^U$

to denote

$\mathbb{L}^U$

to denote

$\{L^{I} \mid L\in\mathbb{L}\}$

,

$\{L^{I} \mid L\in\mathbb{L}\}$

,

$\{L^{O} \mid L\in\mathbb{L}\}$

or

$\{L^{O} \mid L\in\mathbb{L}\}$

or

$\{L^{U} \mid L\in\mathbb{L}\}$

, respectively.

$\{L^{U} \mid L\in\mathbb{L}\}$

, respectively.

Moreover, we say that

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is a labelling-set if

$\mathbb{L}$

is a labelling-set if

-

1.

$ L_1^{I}\cup L_1^{O} \cup L_1^{U}=L_2^{I}\cup L_2^{O} \cup L_2^{U}$

for any

$ L_1^{I}\cup L_1^{O} \cup L_1^{U}=L_2^{I}\cup L_2^{O} \cup L_2^{U}$

for any

$L_1,L_2\in \mathbb{L}$

and, (same arguments)

$L_1,L_2\in \mathbb{L}$

and, (same arguments) -

2.

$L_1^{I}\cap L_1^{O} = L_1^{I}\cap L_1^{U} = L_1^{O}\cap L_1^{U} = \emptyset$

for each

$L_1^{I}\cap L_1^{O} = L_1^{I}\cap L_1^{U} = L_1^{O}\cap L_1^{U} = \emptyset$

for each

$L_1\in\mathbb{L}$

. (disjointness)

$L_1\in\mathbb{L}$

. (disjointness)

Finally, for a fixed set of arguments

![]() $E\subseteq{{\mathcal{U}}}$

we use

$E\subseteq{{\mathcal{U}}}$

we use

-

•

$\mathbb{L}_{I=E} = \{L \mid L\in \mathbb{L} , L^{I} = E\}$

, and (corresponding labellings)

$\mathbb{L}_{I=E} = \{L \mid L\in \mathbb{L} , L^{I} = E\}$

, and (corresponding labellings) -

•

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E} = \{L^{O} \mid L\in \mathbb{L} , L^{I}=E\}$

. (corresponding out-labels)

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E} = \{L^{O} \mid L\in \mathbb{L} , L^{I}=E\}$

. (corresponding out-labels)

Let us illustrate the introduced concepts with the following example.

Example 6 Consider

![]() $\mathbb{L} = \{ (\{a,d\}, \{b\}, \{c\}),(\{b,d\}, \{a,c\}, \emptyset ), (\{b,d\}, \{a\}, \{c\} ) \}$

. First of all, we observe that

$\mathbb{L} = \{ (\{a,d\}, \{b\}, \{c\}),(\{b,d\}, \{a,c\}, \emptyset ), (\{b,d\}, \{a\}, \{c\} ) \}$

. First of all, we observe that

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is indeed a labelling-set as all triples refer to the same arguments, namely a,b,c,d and moreover, for any triple we have that each argument occurs in one of the three sets only. We obtain the following sets:

$\mathbb{L}$

is indeed a labelling-set as all triples refer to the same arguments, namely a,b,c,d and moreover, for any triple we have that each argument occurs in one of the three sets only. We obtain the following sets:

-

•

$\mathbb{L}^I= \{ \{a,d\}, \{b,d\} \}$

,

$\mathbb{L}^I= \{ \{a,d\}, \{b,d\} \}$

,

$\mathbb{L}^O=\{ \{b\}, \{a,c\}, \{a\} \}$

and

$\mathbb{L}^O=\{ \{b\}, \{a,c\}, \{a\} \}$

and

$\mathbb{L}^U=\{\{c\}, \emptyset \} $

,

$\mathbb{L}^U=\{\{c\}, \emptyset \} $

, -

•

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=\{a,d\}}= \{ \{b\}\}$

and

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=\{a,d\}}= \{ \{b\}\}$

and

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=\{b,d\}}= \{ \{a,c\}, \{a\}\}$

, and

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=\{b,d\}}= \{ \{a,c\}, \{a\}\}$

, and -

•

$\mathbb{L}_{I=\{a,d\}}=\{(\{a,d\}, \{b\}, \{c\})\}$

and

$\mathbb{L}_{I=\{a,d\}}=\{(\{a,d\}, \{b\}, \{c\})\}$

and

$\mathbb{L}_{I=\{b,d\}}=\{ (\{b,d\}, \{a,c\}, \emptyset ), (\{b,d\}, \{a\}, \{c\}) \}$

.

$\mathbb{L}_{I=\{b,d\}}=\{ (\{b,d\}, \{a,c\}, \emptyset ), (\{b,d\}, \{a\}, \{c\}) \}$

.

3. Conflict-free labellings

3.1. L-tightness and rejection properties

The presence of characterization theorems for extension-based semantics is of little help in characterizing the corresponding labelling-based version. This is due to the fact that the latter provides one with strictly more information. First of all, they are more restrictive as they assign a status to any argument. Consequently, the possible number of realizing frameworks is limited from the start. Secondly, they are more fine-grained as they explicitly distinguish two non-acceptance cases, namely rejected and undecided (compare Example 2).

In this section we introduce three new properties relevant for characterizing conflict-free labellings. We start with so-called L-tightness. A labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight if: First, greatest out-labels exist and secondly, the union of two in-labels

$\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight if: First, greatest out-labels exist and secondly, the union of two in-labels

![]() $I_1, I_2$

is an in-label too if and only if the greatest out-label regarding

$I_1, I_2$

is an in-label too if and only if the greatest out-label regarding

![]() $I_1$

does not share elements with

$I_1$

does not share elements with

![]() $I_2$

and vice versa. Intuitively, L-tightness fulfills a similar purpose for labelling-sets as tightness for extensions since it gives a reason why certain sets are not in-labels.

$I_2$

and vice versa. Intuitively, L-tightness fulfills a similar purpose for labelling-sets as tightness for extensions since it gives a reason why certain sets are not in-labels.

Definition 11 A labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is called L-tight, if

$\mathbb{L}$

is called L-tight, if

-

1. for each

$E \in\mathbb{L}^I$

we have:

$E \in\mathbb{L}^I$

we have:

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

possesses a

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

possesses a

$\subseteq$

-greatest element.

$\subseteq$

-greatest element.(Notation: We use

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E}$

for the

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E}$

for the

$\subseteq$

-greatest element and

$\subseteq$

-greatest element and

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}_{I=E}$

for the associated labelling.)

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}_{I=E}$

for the associated labelling.) -

2. for all

$I_1,I_2 \in\mathbb{L}^I$

we have:

$I_1,I_2 \in\mathbb{L}^I$

we have:

$ I_1 \cup I_2 \in \mathbb{L}^I \Leftrightarrow (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2) \cup (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} \cap I_1) = \emptyset.$

$ I_1 \cup I_2 \in \mathbb{L}^I \Leftrightarrow (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2) \cup (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} \cap I_1) = \emptyset.$

Example 7 First note, that

![]() $\subseteq$

-greatest elements do not exist in general as witnessed by the two-element set

$\subseteq$

-greatest elements do not exist in general as witnessed by the two-element set

![]() $\{(\{a\},\{b\},\{c\}),(\{a\},\{c\},\{b\})\}$

. Let us verify that the labelling-set

$\{(\{a\},\{b\},\{c\}),(\{a\},\{c\},\{b\})\}$

. Let us verify that the labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L} = {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

from the running AF

$\mathbb{L} = {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

from the running AF

![]() ${F}$

presented in Example 1 satisfy L-tightness. We have:

${F}$

presented in Example 1 satisfy L-tightness. We have:

-

•

$\mathbb{L}^I = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F}) =\{\{ a\}, \{b\}, \{c\}, \{d\},\{a,d\}, \{b,d\}, \emptyset \}$

.

$\mathbb{L}^I = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F}) =\{\{ a\}, \{b\}, \{c\}, \{d\},\{a,d\}, \{b,d\}, \emptyset \}$

. -

• For each

$E \in\mathbb{L}^I$

we have a

$E \in\mathbb{L}^I$

we have a

$\subseteq$

-greatest element in

$\subseteq$

-greatest element in

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

. More precisely,

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

. More precisely,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}} = \{b\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}} = \{b\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{b\}} = \{c\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{b\}} = \{c\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{c\}} = \{a\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{c\}} = \{a\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{d\}} = \{c\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{d\}} = \{c\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a,d\}} = \{b,c\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a,d\}} = \{b,c\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{b,d\}} = \{c\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{b,d\}} = \{c\}$

,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\emptyset} = \emptyset$

.

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\emptyset} = \emptyset$

. -

• Now, for the second item of L-tightness we have to consider each possible pairing of in-labels. For space reasons we will consider only two pairings and left the remaining combinations for the reader.

-

1. Consider

$I_1 = \{a\}$

and

$I_1 = \{a\}$

and

$I_2 = \{d\}$

. We have

$I_2 = \{d\}$

. We have

$I_1 \cup I_2 = \{a,d\} \in \mathbb{L}^I$

and moreover,

$I_1 \cup I_2 = \{a,d\} \in \mathbb{L}^I$

and moreover,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2 = \{b\} \cap \{d\} = \emptyset = \{c\}\cap \{a\} = \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} \cap I_1$

.

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2 = \{b\} \cap \{d\} = \emptyset = \{c\}\cap \{a\} = \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} \cap I_1$

. -

2. Consider

$I_1 = \{a\}$

and

$I_1 = \{a\}$

and

$I_2 = \{b\}$

.

$I_2 = \{b\}$

.We have

$I_1 \cup I_2 = \{a,b\} \notin \mathbb{L}^I$

and the corresponding non-emptiness of the union witnessed by

$I_1 \cup I_2 = \{a,b\} \notin \mathbb{L}^I$

and the corresponding non-emptiness of the union witnessed by

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2 = \{b\} \cap \{b\} = \{b\}\neq \emptyset.$

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2 = \{b\} \cap \{b\} = \{b\}\neq \emptyset.$

The second newly introduced property is called reject-compositionality. In a nutshell, a labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional, if the out-labelled arguments for a given in-labelled set E can be found in the union of out-labels of single arguments in E.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional, if the out-labelled arguments for a given in-labelled set E can be found in the union of out-labels of single arguments in E.

Definition 12 A labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is called reject-compositional, if for each

$\mathbb{L}$

is called reject-compositional, if for each

![]() $E\in\mathbb{L}^I$

, we have:

$E\in\mathbb{L}^I$

, we have:

We mention that in case of L-tight labelling-sets the equation transforms to

![]() $\displaystyle{\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E} = \bigcup_{a\in E} \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}}$

.

$\displaystyle{\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E} = \bigcup_{a\in E} \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}}$

.

Before turning to an example we introduce the third new concept. A labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing if each out-labelled argument o for a fixed in-labelled set E possesses a witnessing ‘basic’ labelling. That is, we find an element

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing if each out-labelled argument o for a fixed in-labelled set E possesses a witnessing ‘basic’ labelling. That is, we find an element

![]() $i\in E$

with

$i\in E$

with

![]() $\left(\{i\},\{o\},Args_{\mathbb{L}}\setminus\{i,o\}\right)\in \mathbb{L}$

.

$\left(\{i\},\{o\},Args_{\mathbb{L}}\setminus\{i,o\}\right)\in \mathbb{L}$

.

Definition 13 A labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is called reject-witnessing, if for each

$\mathbb{L}$

is called reject-witnessing, if for each

![]() $L \in\mathbb{L}$

we have:

$L \in\mathbb{L}$

we have:

Example 8 (Example 1 cont.) Consider again the labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L} = {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

from the running AF

$\mathbb{L} = {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

from the running AF

![]() ${F}$

presented in Example 1. We will show that

${F}$

presented in Example 1. We will show that

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing as well as reject-compositional.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing as well as reject-compositional.

For reject-witnessing it suffices to consider

![]() ${L}_1 = ( \{a,d\} , \{b,c\}, \emptyset)\in {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

as well as

${L}_1 = ( \{a,d\} , \{b,c\}, \emptyset)\in {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

as well as

![]() ${L}_2 = (\{b,d\} , \{c\},\{a\}))\in {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

. For the first labelling the rejections are witnessed by

${L}_2 = (\{b,d\} , \{c\},\{a\}))\in {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

. For the first labelling the rejections are witnessed by

![]() $(\{ a\}, \{b \}, \{ c,d\})\in {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

and

$(\{ a\}, \{b \}, \{ c,d\})\in {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

and

![]() $( \{d\} , \{c\}, \{a,b\})\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

. The latter basic labelling also serves as a witness for

$( \{d\} , \{c\}, \{a,b\})\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

. The latter basic labelling also serves as a witness for

![]() ${L}_2$

.

${L}_2$

.

Now, for reject-compositionality. We have already seen that

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight (Example 7). This means, it suffices to show

$\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight (Example 7). This means, it suffices to show

![]() $\displaystyle{\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E} = \bigcup_{a\in E} \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}}$

. We only have to consider both two-element sets. Let us start with

$\displaystyle{\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E} = \bigcup_{a\in E} \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}}$

. We only have to consider both two-element sets. Let us start with

![]() $E = \{a,d\}$

. We have,

$E = \{a,d\}$

. We have,

![]() $\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a,d\}}= \{b,c\}$

and the matching sets,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a,d\}}= \{b,c\}$

and the matching sets,

![]() $\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}= \{b\}$

and

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}= \{b\}$

and

![]() $\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{d\}} = \{c\}$

. Finally, for

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{d\}} = \{c\}$

. Finally, for

![]() $E = \{b,d\}$

we get

$E = \{b,d\}$

we get

![]() $\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{b,d\}} = \{c\}$

and,

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{b,d\}} = \{c\}$

and,

![]() $\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{b\}}= \{c\}$

and

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{b\}}= \{c\}$

and

![]() $\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{d\}} = \{c\}$

as required.

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{d\}} = \{c\}$

as required.

Finally, we mention that none of the properties can be derived from the remaining two. This means, for example, that there are labelling-sets satisfying both rejection properties without being L-tight.

3.2. Standard construction

As a matter of fact, knowing that a certain set is realizable or not is a valuable feature. However, for many applications it is not only of interest whether a certain set is realizable, but also how to realize it. In the following we introduce a standard construction witnessing the realizability of a considered labelling-set. This construction is not only generally of interest but is a vital step towards a characterization of conflict-free realizability.

First, with respect to arguments, we simply collect any that occur in a labelling. Secondly, for the attack relation, a self-loop is added to an argument a if

![]() $\{a\}$

is not present as an in-labelled set. Moreover, a attacks an other argument b, if

$\{a\}$

is not present as an in-labelled set. Moreover, a attacks an other argument b, if

![]() $\{a\}$

can be found as an in-labelled set and b is contained in at least one corresponding out-labelled set.

$\{a\}$

can be found as an in-labelled set and b is contained in at least one corresponding out-labelled set.

Definition 14 Given a labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

. We define

$\mathbb{L}$

. We define

![]() ${F}_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}} = (A_{\mathbb{L}},R_{\mathbb{L}})$

with

${F}_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}} = (A_{\mathbb{L}},R_{\mathbb{L}})$

with

![]() $A_{\mathbb{L}}={Args}(\mathbb{L})$

and

$A_{\mathbb{L}}={Args}(\mathbb{L})$

and

-

1.

$\forall a\in A_{\mathbb{L}}$

:

$\forall a\in A_{\mathbb{L}}$

:

$(a,a)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

if and only if

$(a,a)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

if and only if

$\{a\}\notin\mathbb{L}^I$

, and

$\{a\}\notin\mathbb{L}^I$

, and -

2.

$\forall a,b\in A_{\mathbb{L}}$

: If

$\forall a,b\in A_{\mathbb{L}}$

: If

$a\neq b$

, then

$a\neq b$

, then

$(a,b)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

iff

$(a,b)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

iff

$\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

and

$\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

and

$b\in \bigcup\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

.

$b\in \bigcup\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

.

First we want to emphasize an important point: the construction is well-defined. This means, the AF

![]() ${F}_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}}$

can be built for any labelling-set

${F}_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}}$

can be built for any labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

, even if the considered set is not

$\mathbb{L}$

, even if the considered set is not

![]() ${cf}$

-realizable. We proceed with an illustrating example.

${cf}$

-realizable. We proceed with an illustrating example.

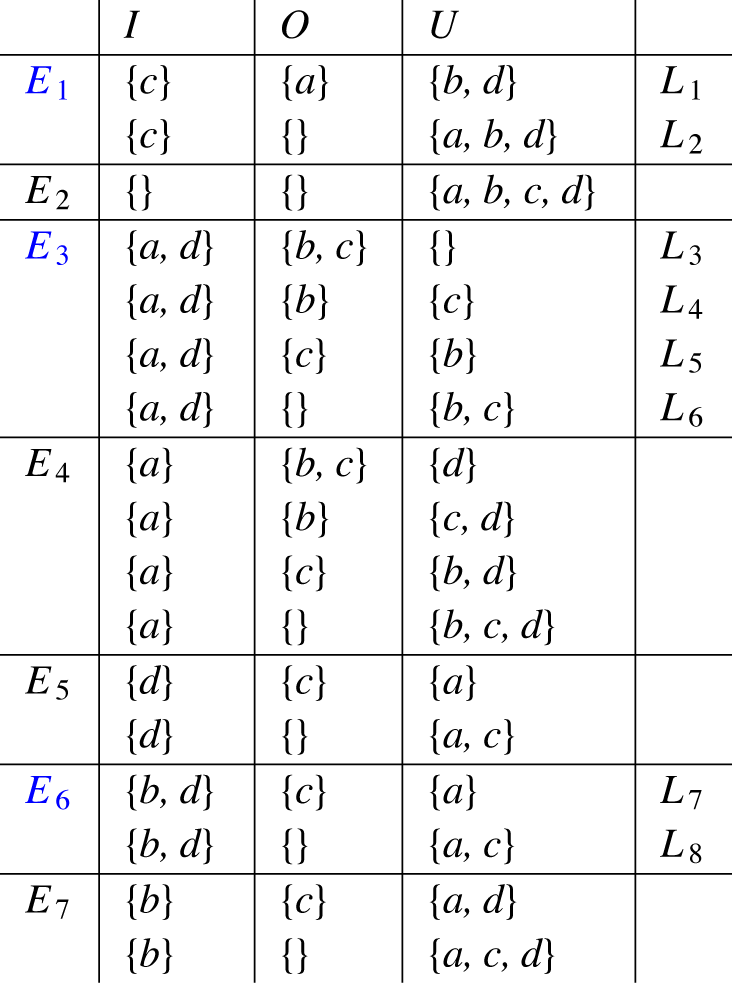

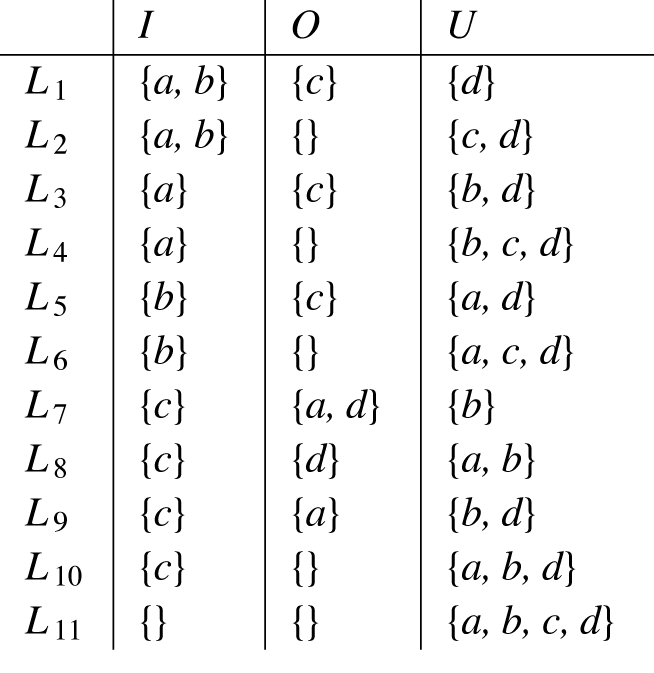

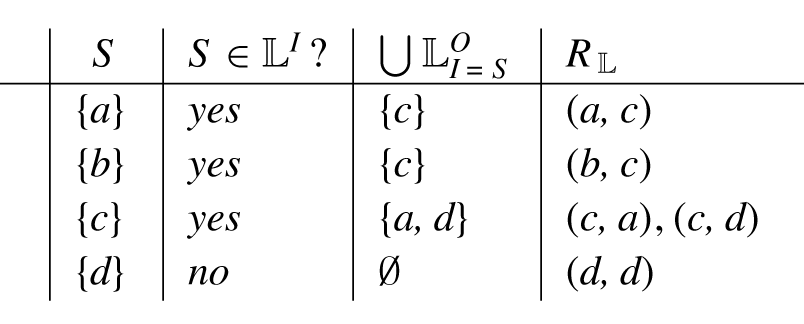

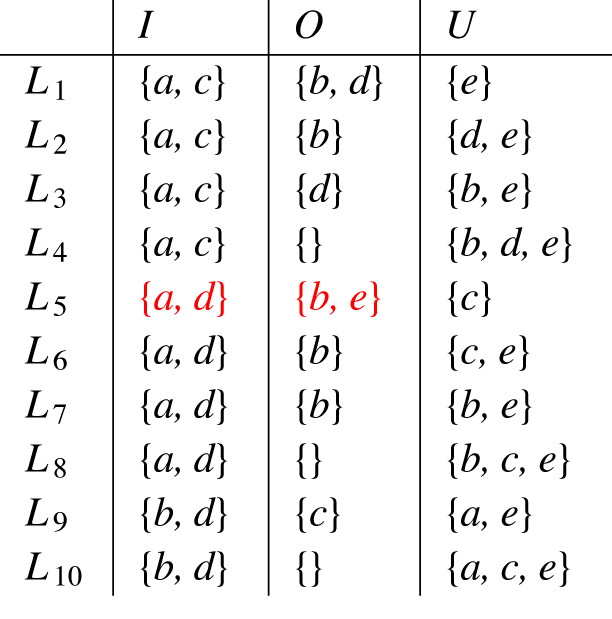

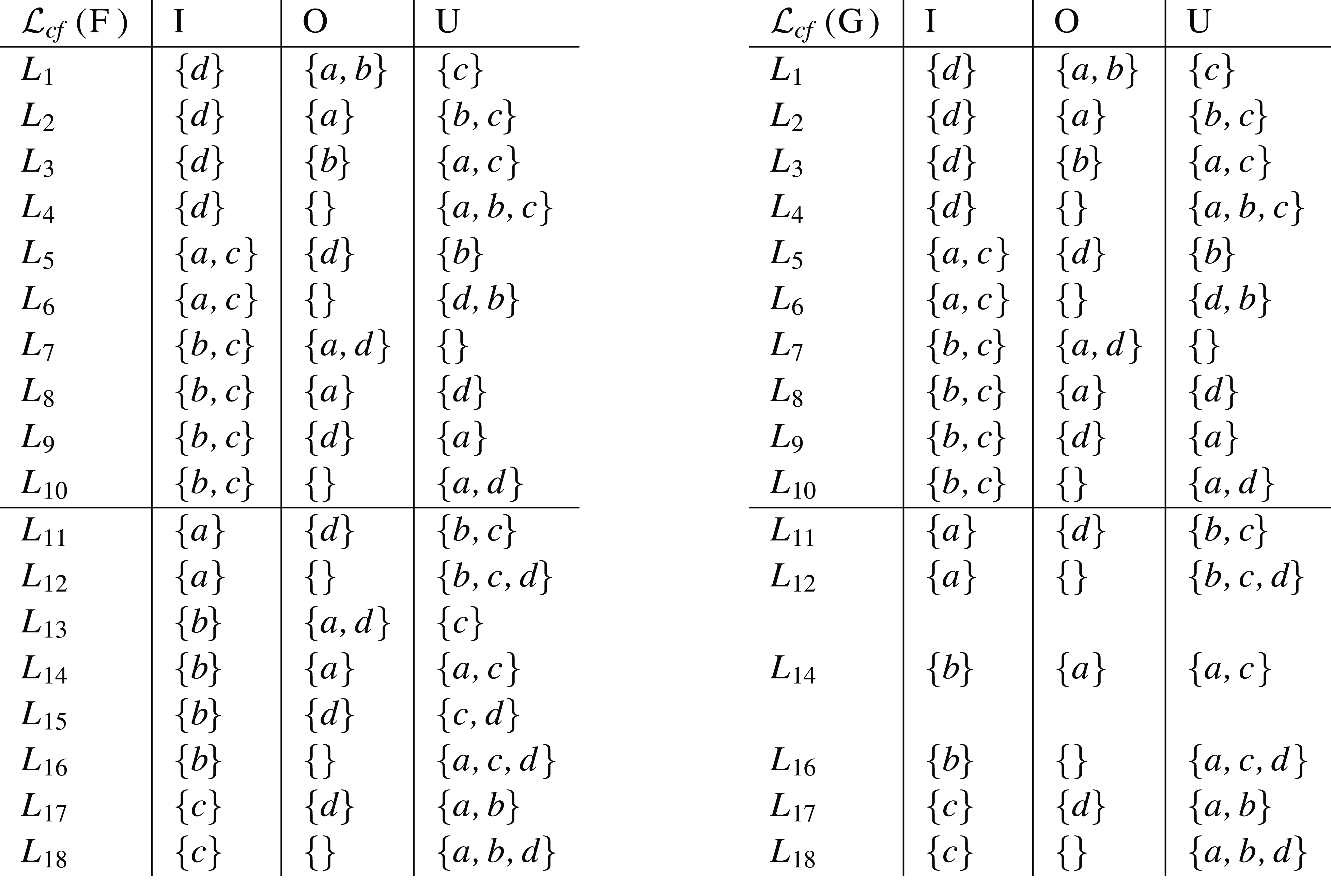

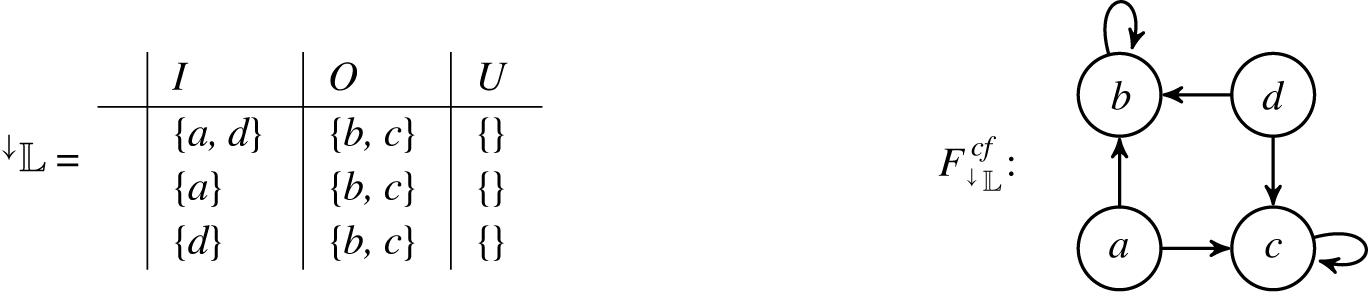

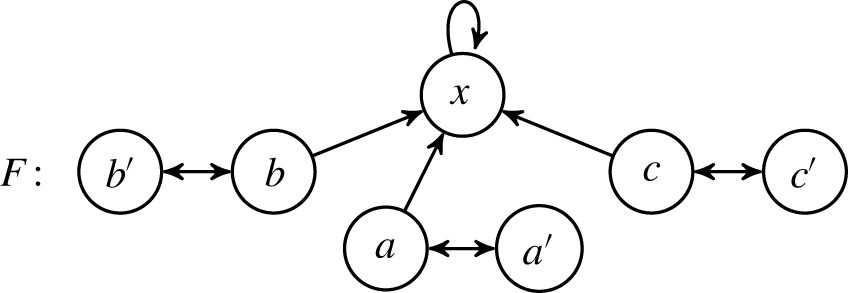

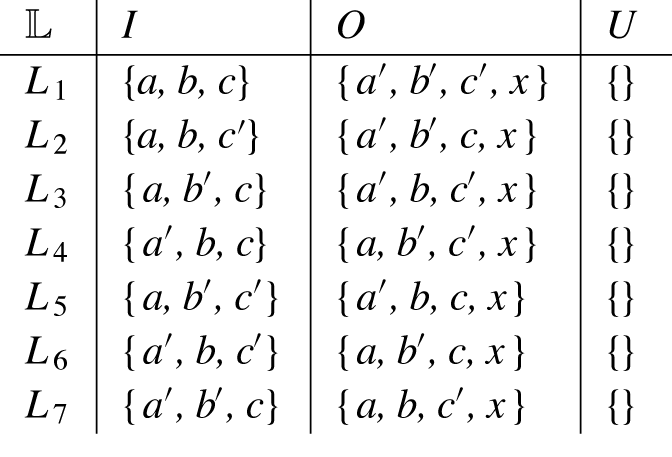

Example 9 Consider the following labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

presented in form of a table.

$\mathbb{L}$

presented in form of a table.

We obtain

![]() $A_{\mathbb{L}} = {Args}(\mathbb{L}) = \{a, b, c, d\}$

. Regarding

$A_{\mathbb{L}} = {Args}(\mathbb{L}) = \{a, b, c, d\}$

. Regarding

![]() $R_{\mathbb{L}}$

we have to consider the singletons

$R_{\mathbb{L}}$

we have to consider the singletons

![]() $\{a\},\{b\},\{c\}$

and

$\{a\},\{b\},\{c\}$

and

![]() $\{d\}$

.

$\{d\}$

.

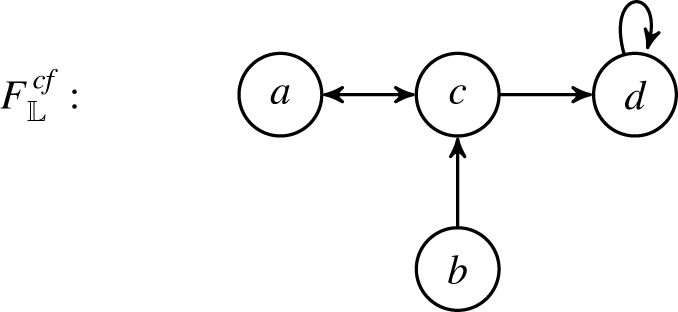

The obtained construction is depicted below.

3.3. Characterization theorem

In the following we present the central characterization theorem for conflict-free labellings. It can be seen that the newly introduced properties play a central role here. Please note that any of the five properties can be decided by looking at the labelling-set in question only.

Theorem 2 Given a labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L} \subseteq \left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^3$

we have

$\mathbb{L} \subseteq \left(2^{{\mathcal{U}}}\right)^3$

we have

![]() $\mathbb{L}\in\Sigma_{\mathcal{L}_{cf}}\; \Leftrightarrow$

$\mathbb{L}\in\Sigma_{\mathcal{L}_{cf}}\; \Leftrightarrow$

-

1.

$\mathbb{L}^I$

is downward-closed and non-empty,

$\mathbb{L}^I$

is downward-closed and non-empty, -

2.

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

is downward-closed for all

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

is downward-closed for all

$E\in \mathbb{L}^I$

,

$E\in \mathbb{L}^I$

, -

3.

$\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight, and

$\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight, and -

4.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing, and

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing, and -

5.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional.

Proof. If-direction. This means:

Given a labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

.If

$\mathbb{L}$

.If

![]() $\mathbb{L}\in\Sigma_{{{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}}}$

, then:

$\mathbb{L}\in\Sigma_{{{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}}}$

, then:

-

1.

$\mathbb{L}^I$

is downward-closed and non-empty,

$\mathbb{L}^I$

is downward-closed and non-empty, -

2.

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

is downward-closed for all

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

is downward-closed for all

$E\in \mathbb{L}^I$

,

$E\in \mathbb{L}^I$

, -

3.

$\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight, and

$\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight, and -

4.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing, and

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing, and -

5.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional.

Given

![]() $\mathbb{L}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}}$

. Hence, there is an AF

$\mathbb{L}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}}$

. Hence, there is an AF

![]() ${F} = (A,R)$

with

${F} = (A,R)$

with

![]() ${{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F}) = \mathbb{L}$

and

${{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}({F}) = \mathbb{L}$

and

![]() ${Args}_{\mathbb{L}} = A$

. We further deduce

${Args}_{\mathbb{L}} = A$

. We further deduce

![]() $\mathbb{L}^{I} = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

(Items 1,2 of Proposition 1). According to Theorem 1 we obtain

$\mathbb{L}^{I} = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

(Items 1,2 of Proposition 1). According to Theorem 1 we obtain

![]() $\mathbb{L}^{I}$

is downward-closed and non-empty.

$\mathbb{L}^{I}$

is downward-closed and non-empty.

Consider now

![]() $\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

for a certain

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

for a certain

![]() $E\in \mathbb{L}^I$

. Due to Item 1 of Definition 2 we deduce

$E\in \mathbb{L}^I$

. Due to Item 1 of Definition 2 we deduce

![]() $\left(E\times E\right) \cap R = \emptyset$

. Let us consider now the associated range given as

$\left(E\times E\right) \cap R = \emptyset$

. Let us consider now the associated range given as

![]() ${E}^+ =\{b\mid (a,b)\in R, a\in {E}\}$

. In light of Item 2 of Definition 2 we obtain

${E}^+ =\{b\mid (a,b)\in R, a\in {E}\}$

. In light of Item 2 of Definition 2 we obtain

![]() $\mathbb{L}_{I=E}=\{(E,E', A\setminus (E\cup E') ) | E'\subseteq E^+\}$

. Consequently,

$\mathbb{L}_{I=E}=\{(E,E', A\setminus (E\cup E') ) | E'\subseteq E^+\}$

. Consequently,

![]() $\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E} = \left\{E'\mid E'\subseteq E^+\right\}$

which is obviously downward-closed. (Item 2)

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E} = \left\{E'\mid E'\subseteq E^+\right\}$

which is obviously downward-closed. (Item 2)

We now turn to L-tightness. According to Definition 11 we have to show two properties. First, the existence of a greatest element. Consider therefore a fixed set

![]() $E \in\mathbb{L}^I$

. The associated range

$E \in\mathbb{L}^I$

. The associated range

![]() ${E}^+ =\{b\mid (a,b)\in R, a\in {E}\}$

together with Item 2 of Definition 2 yields

${E}^+ =\{b\mid (a,b)\in R, a\in {E}\}$

together with Item 2 of Definition 2 yields

![]() $\mathbb{L}_{I=E}=\{(E,E', A\setminus (E\cup E') ) | E'\subseteq E^+\}$

. Consequently,

$\mathbb{L}_{I=E}=\{(E,E', A\setminus (E\cup E') ) | E'\subseteq E^+\}$

. Consequently,

![]() $\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

possesses a

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

possesses a

![]() $\subseteq$

-greatest element, namely

$\subseteq$

-greatest element, namely

![]() $E^+ = \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E}$

.

$E^+ = \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E}$

.

Secondly, the compatibility criteria. Let

![]() $I_1,I_2 \in\mathbb{L}^I$

and assume

$I_1,I_2 \in\mathbb{L}^I$

and assume

![]() $I_1 \cup I_2 \in \mathbb{L}^I$

. Note that

$I_1 \cup I_2 \in \mathbb{L}^I$

. Note that

![]() $\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} = I_1^+$

and

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} = I_1^+$

and

![]() $\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} = I_2^+$

. The assumption

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} = I_2^+$

. The assumption

![]() $I_1 \cup I_2 \in \mathbb{L}^I$

yields

$I_1 \cup I_2 \in \mathbb{L}^I$

yields

![]() $\left((I_1 \cup I_2)\times(I_1 \cup I_2)\right) \cap R = \emptyset$

as Item 1 of Definition 2 holds true. Thus,

$\left((I_1 \cup I_2)\times(I_1 \cup I_2)\right) \cap R = \emptyset$

as Item 1 of Definition 2 holds true. Thus,

![]() $(I_1^+ \cap I_2) = (I_2^+ \cap I_1) = \emptyset.$

Consequently,

$(I_1^+ \cap I_2) = (I_2^+ \cap I_1) = \emptyset.$

Consequently,

![]() $(\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2) \cup (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} \cap I_1) = \emptyset.$

$(\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2) \cup (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} \cap I_1) = \emptyset.$

Now, for the reverse direction. We assume

![]() $(\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2) \cup (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} \cap I_1)=\emptyset.$

This means,

$(\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_1} \cap I_2) \cup (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=I_2} \cap I_1)=\emptyset.$

This means,

![]() $(I_1^+ \cap I_2) = (I_2^+ \cap I_1) = \emptyset.$

Moreover, since

$(I_1^+ \cap I_2) = (I_2^+ \cap I_1) = \emptyset.$

Moreover, since

![]() $I_1,I_2 \in\mathbb{L}^I$

is assumed we further have

$I_1,I_2 \in\mathbb{L}^I$

is assumed we further have

![]() $(I_1^+ \cap I_1) = (I_2^+ \cap I_2) = \emptyset.$

From these two equations we deduce

$(I_1^+ \cap I_1) = (I_2^+ \cap I_2) = \emptyset.$

From these two equations we deduce

![]() $\left((I_1 \cup I_2)\times(I_1 \cup I_2)\right) \cap R = \emptyset$

justifying

$\left((I_1 \cup I_2)\times(I_1 \cup I_2)\right) \cap R = \emptyset$

justifying

![]() $L = \left(I_1 \cup I_2,(I_1 \cup I_2)^+,{Args}(\mathbb{L})\setminus \left((I_1 \cup I_2) \cup (I_1 \cup I_2)^+\right)\right) \in\mathbb{L}$

. Hence,

$L = \left(I_1 \cup I_2,(I_1 \cup I_2)^+,{Args}(\mathbb{L})\setminus \left((I_1 \cup I_2) \cup (I_1 \cup I_2)^+\right)\right) \in\mathbb{L}$

. Hence,

![]() $I_1 \cup I_2 \in \mathbb{L}^I$

is shown concluding L-tightness. (Item 3)

$I_1 \cup I_2 \in \mathbb{L}^I$

is shown concluding L-tightness. (Item 3)

We further have to show that

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing. This can be seen as follows: Consider a labelling

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing. This can be seen as follows: Consider a labelling

![]() $L = \left(L^I,L^O,L^U\right)\in\mathbb{L}$

. Due to Item 1 of Definition 2 we deduce

$L = \left(L^I,L^O,L^U\right)\in\mathbb{L}$

. Due to Item 1 of Definition 2 we deduce

![]() $\left(L^I\times L^I\right) \cap R = \emptyset$

. Hence, each singleton

$\left(L^I\times L^I\right) \cap R = \emptyset$

. Hence, each singleton

![]() $\{i\}\subseteq L^I$

is conflict-free too. Moreover, due to Item 2 of Definition 2 we infer

$\{i\}\subseteq L^I$

is conflict-free too. Moreover, due to Item 2 of Definition 2 we infer

![]() $L^O \subseteq \left(L^I\right)^+ =\left\{o\mid (i,o)\in R, i\in L^I\right\}$

. Consequently, for each

$L^O \subseteq \left(L^I\right)^+ =\left\{o\mid (i,o)\in R, i\in L^I\right\}$

. Consequently, for each

![]() $o\in L^O\ \exists i\in L^I$

with

$o\in L^O\ \exists i\in L^I$

with

![]() $(i,o)\in R$

. Hence,

$(i,o)\in R$

. Hence,

![]() $\left(\{i\},\{o\},A\setminus\{i,o\}\right)\in \mathbb{L}$

as there are no conditions for undec-labels. (Item 4)

$\left(\{i\},\{o\},A\setminus\{i,o\}\right)\in \mathbb{L}$

as there are no conditions for undec-labels. (Item 4)

Finally, we show that

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional. Let us fix a set

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional. Let us fix a set

![]() $E\in \mathbb{L}^{I}$

. Since

$E\in \mathbb{L}^{I}$

. Since

![]() $\mathbb{L}^{I} = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

we deduce

$\mathbb{L}^{I} = {{\mathcal{E}}}_{{cf}}({F})$

we deduce

![]() $\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^{I}$

for all

$\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^{I}$

for all

![]() $a\in E$

. Let now

$a\in E$

. Let now

![]() $b\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}$

for a fixed

$b\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}$

for a fixed

![]() $a\in E$

. Due to Definition 2, Item 2 we obtain

$a\in E$

. Due to Definition 2, Item 2 we obtain

![]() $(a,b)\in R({F})$

. Hence,

$(a,b)\in R({F})$

. Hence,

![]() $b\in E^+ = \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{E\}}$

showing

$b\in E^+ = \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{E\}}$

showing

![]() $\displaystyle{\bigcup_{a\in E} \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}\subseteq \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{E\}}}$

. Consider now

$\displaystyle{\bigcup_{a\in E} \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}\subseteq \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{E\}}}$

. Consider now

![]() $b\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E} = E^+$

. Consequently, there is an

$b\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E} = E^+$

. Consequently, there is an

![]() $a\in E$

with

$a\in E$

with

![]() $(a,b)\in R({F})$

. We already know that

$(a,b)\in R({F})$

. We already know that

![]() $\{a\}\in \mathbb{L}^{I}$

yielding

$\{a\}\in \mathbb{L}^{I}$

yielding

![]() $b\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}$

. Thus,

$b\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}$

. Thus,

![]() $\displaystyle{\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E} \subseteq \bigcup_{a\in E} \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}}$

concluding the proof. (Item 5)

$\displaystyle{\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=E} \subseteq \bigcup_{a\in E} \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}}}$

concluding the proof. (Item 5)

Only-if-direction. This means:

Given a labelling-set

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

, we have:

$\mathbb{L}$

, we have:

![]() $\mathbb{L} = {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}\left(F_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}}\right)$

(and thus,

$\mathbb{L} = {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}\left(F_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}}\right)$

(and thus,

![]() $\mathbb{L}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}}$

), if

$\mathbb{L}\in \Sigma_{{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}}$

), if

-

1.

$\mathbb{L}^I$

is downward-closed and non-empty,

$\mathbb{L}^I$

is downward-closed and non-empty, -

2.

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

is downward-closed for all

$\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I=E}$

is downward-closed for all

$E\in \mathbb{L}^I$

,

$E\in \mathbb{L}^I$

, -

3.

$\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight,

$\mathbb{L}$

is L-tight, -

4.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing, and

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing, and -

5.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional.

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-compositional.

We split the proof into two subset relations.

-

• We start with

$\mathbb{L} \subseteq {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}\left(F_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}}\right)$

. Consider

$\mathbb{L} \subseteq {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}\left(F_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}}\right)$

. Consider

${L}\in\mathbb{L}$

. We have to show

${L}\in\mathbb{L}$

. We have to show

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}\left(F_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}}\right)$

.

${L}\in{{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}\left(F_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}}\right)$

.-

1. No internal conflicts. This means, for each two

$a,b\in {L}^{\text{I}}$

, we have

$a,b\in {L}^{\text{I}}$

, we have

$(a,b)\notin R_{\mathbb{L}}$

.

$(a,b)\notin R_{\mathbb{L}}$

.Let

$a = b$

. According to Definition 14, Item 2 we have:

$a = b$

. According to Definition 14, Item 2 we have:

$(a,a)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

iff

$(a,a)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

iff

$\{a\}\notin\mathbb{L}^I$

. Since downward-closedness of

$\{a\}\notin\mathbb{L}^I$

. Since downward-closedness of

$\mathbb{L}^I$

is assumed, we deduce for any

$\mathbb{L}^I$

is assumed, we deduce for any

$E \subseteq {L}^{\text{I}}$

,

$E \subseteq {L}^{\text{I}}$

,

$E\in\mathbb{L}^I$

. Hence,

$E\in\mathbb{L}^I$

. Hence,

$\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

and thus

$\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

and thus

$(a,a)\notin R_{\mathbb{L}}$

.

$(a,a)\notin R_{\mathbb{L}}$

.Let

$a\neq b$

. According to Definition 14, Item 3 we have:

$a\neq b$

. According to Definition 14, Item 3 we have:

$(a,b)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

iff

$(a,b)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

iff

$\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

and

$\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

and

$b\in \bigcup\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

. The latter union can be replaced with

$b\in \bigcup\mathbb{L}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

. The latter union can be replaced with

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

as L-tightness of

$\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

as L-tightness of

$\mathbb{L}$

is given. Since

$\mathbb{L}$

is given. Since

$a,b\in {L}^{\text{I}}$

is assumed, we obtain

$a,b\in {L}^{\text{I}}$

is assumed, we obtain

$\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

due to the downward-closedness of

$\{a\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

due to the downward-closedness of

$\mathbb{L}^I$

. Thus, we have to show

$\mathbb{L}^I$

. Thus, we have to show

$b\notin \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

. Suppose, towards a contradiction that

$b\notin \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

. Suppose, towards a contradiction that

$b\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

. This means, there is label

$b\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

. This means, there is label

${M}\in\mathbb{L}$

with

${M}\in\mathbb{L}$

with

${M}^I = \{a\}$

and

${M}^I = \{a\}$

and

$b\in {M}^O$

. Since

$b\in {M}^O$

. Since

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing we deduce the existence of

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing we deduce the existence of

$N=(\{a\},\{b\},A_{\mathbb{L}}\setminus\{a,b\})\in\mathbb{L}$

. Moreover, since

$N=(\{a\},\{b\},A_{\mathbb{L}}\setminus\{a,b\})\in\mathbb{L}$

. Moreover, since

$\mathbb{L}$

is assumed to be L-tight and

$\mathbb{L}$

is assumed to be L-tight and

$ {L}^{\text{I}} \cup N^I = {L}^{\text{I}} \cup \{a\} = {L}^{\text{I}} \in \mathbb{L}^I$

we deduce:

$ {L}^{\text{I}} \cup N^I = {L}^{\text{I}} \cup \{a\} = {L}^{\text{I}} \in \mathbb{L}^I$

we deduce:

$(\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I={L}^{\text{I}}} \cap \{a\}) \cup (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}} \cap {L}^{\text{I}}) = \emptyset.$

However, the second set is non-empty as

$(\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I={L}^{\text{I}}} \cap \{a\}) \cup (\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}} \cap {L}^{\text{I}}) = \emptyset.$

However, the second set is non-empty as

$b\in(\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}} \cap {L}^{\text{I}}) \neq \emptyset$

. Thus,

$b\in(\overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{a\}} \cap {L}^{\text{I}}) \neq \emptyset$

. Thus,

$b\notin \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

and finally,

$b\notin \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I = \{a\}}$

and finally,

$(a,b)\notin R_{\mathbb{L}}$

.

$(a,b)\notin R_{\mathbb{L}}$

. -

2. Reason for rejecting. This means, if

$a\in {L}^{\text{O}}$

, then there is a

$a\in {L}^{\text{O}}$

, then there is a

$b\in{L}^{\text{I}}$

with

$b\in{L}^{\text{I}}$

with

$(b,a)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

.

$(b,a)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

.Let

$a\in {L}^{\text{O}}$

. As

$a\in {L}^{\text{O}}$

. As

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing, we deduce for some

$\mathbb{L}$

is reject-witnessing, we deduce for some

$b\in{L}^{\text{I}}$

the existence of a labelling

$b\in{L}^{\text{I}}$

the existence of a labelling

$N = \left(\{b\},\{a\},{Args}_{\mathbb{L}}\setminus\{a,b\}\right)\in \mathbb{L}$

. This means,

$N = \left(\{b\},\{a\},{Args}_{\mathbb{L}}\setminus\{a,b\}\right)\in \mathbb{L}$

. This means,

$\{b\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

and

$\{b\}\in\mathbb{L}^I$

and

$a\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{b\}}$

. Thus, according to Definition 14, Item 3 we obtain

$a\in \overline{\mathbb{L}}^{O}_{I=\{b\}}$

. Thus, according to Definition 14, Item 3 we obtain

$(b,a)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

.

$(b,a)\in R_{\mathbb{L}}$

.

-

-

• It remains to show

$\mathbb{L} \supseteq {{\mathcal{L}}}_{{cf}}\left(F_{\mathbb{L}}^{{cf}}\right)$

. Let