Introduction

Socio-legal research has enriched our understanding of how climate litigation frames norms, knowledge and relationships (Fisher Reference Fisher2013; Marshall and Sterett Reference Marshall and Sterett2019; Walker-Crawford Reference Walker-Crawford2022) and influences law, policy, and governance (Peel and Osofsky Reference Peel and Osofsky2020; Setzer and Vanhala Reference Setzer and Vanhala2019). The factors that influence the willingness and ability of NGOs and communities to turn to litigation as a way of responding to climate change or climate action have received less attention, however (Setzer and Vanhala Reference Setzer and Vanhala2019, 6).

Our article addresses this gap in the literature by offering an in-depth account of the role of transnational practices in fostering and shaping the diffusion of rights-based climate litigation (RBCL). RBCL is a distinct type of public interest climate case brought by lawyers, NGOs, or affected communities that relies on human rights law to hold governments and corporations accountable for their contributions to climate change and its impacts on individuals and communities (Iyengar Reference Iyengar2023; Peel and Osofsky Reference Peel and Osofsky2018; Savaresi and Setzer Reference Savaresi and Setzer2022).Footnote 1 By our count, as of December 2023, over 174 such cases have been initiated across 47 countries’ domestic courts and 13 international and regional courts and treaty bodies (see Annex 1 for our data collection protocol and list of cases). We view RBCL as a “critical” or “most-likely” case (Flyvbjerg Reference Flyvbjerg, Norman and Lincoln2011, 307) of the role played by transnational practices in the diffusion of climate litigation. While RBCL provides a rich empirical context for understanding how transnational practices influence legal mobilization in the field of climate change, it does not, however, enable us to speak to the prevalence of these practices in other subfields of climate litigation.

Like other socio-legal studies of climate litigation, our analysis extends beyond the substance of legal cases and decisions to encompass the broader social and political context that influences the decision of lawyers and activists to mobilize law to address climate change (Vanhala Reference Vanhala and Rodríguez-Garavito2022b). We also conceive of climate litigation as a transnational legal process that emerges from, interacts with and influences legal norms, institutions and discourses at the local, regional and international levels (Affolder and Dzah Reference Affolder, Dzah and Sindico2024; Osofsky Reference Osofsky2009; Paiement Reference Paiement2024; Peel and Lin Reference Peel and Lin2019). Finally, we draw inspiration from the practice turn in international relations and law (Adler and Pouliot Reference Adler and Pouliot2011a; Mason-Case Reference Mason-Case2019; Meierhenrich Reference Meierhenrich2013) and examine how the practices of civil society actors have facilitated and influenced the diffusion of RBCL around the world.

We make three claims about the nature and influence of transnational practices in the field of RBCL. First, we show that the practices of collaboration, storytelling and learning have played an influential role in the emergence and evolution of RBCL. Through these practices, the actors involved in initiating or supporting RBCL – lawyers, litigants, communities, scholars and NGOs – have fostered and sustained the transnational generation, exchange and flow of resources, relationships, narratives and knowledge underlying the field of RBCL.

Second, we argue that all three practices have fostered the diffusion of RBCL by influencing the local determinants of legal mobilization through enabling, discursive and relational pathways. The enabling pathway involves the production, pooling, distribution and use of material and ideational resources that make the initiation of a lawsuit possible. The discursive pathway encompasses the generation, diffusion and internalization of shared understandings that define the legal nature of social problems and how they should be addressed inside the courtroom. The relational pathway focuses on the social influence of peers and communities on the beliefs and identities of lawyers and activists and their understanding of the appropriateness and meaning of litigation as a tactic for advancing social change.

Third, we show that these practices have had structural effects that have shaped the ideas and identities of the practitioners in the field of RBCL. Over time, the discursive and relational dimensions of practices have given rise to and have been strengthened by the formation of multiple communities of practice. The emergence of distinct communities provides the possibility for deeper forms of socialization and acculturation among their members, but they also make conflict and competition between different communities more likely. Overall, our article emphasizes the importance of understanding legal mobilization for climate justice as a set of practices that are shaped by the transnational social-legal context in which they are performed.

Existing knowledge in the field of RBCL

RBCL has attracted significant scholarly attention due to the prominence of “holy-grail cases” that advance novel legal arguments and seek potentially transformative legal remedies (Bouwer Reference Bouwer2018; Peel and Osofsky Reference Peel and Osofsky2018). Notable examples include the Inuit Petition (Watt-Cloutier Reference Watt-Cloutier2005), Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan (2015), Demanda Generaciones Futuras v. Minambiente (2018), Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands (2020), Juliana v. United States (2020), and KlimaSeniorinnen v Switzerland (2024). There is a large literature examining the legal arguments, decisions and outcomes of key cases in the field RBCL (Beauregard et al. Reference Beauregard, Carlson, Ann Robinson, Cobb and Patton2021; Rodríguez-Garavito Reference Rodríguez-Garavito and Rodríguez-Garavito2022; Savaresi and Setzer Reference Savaresi and Setzer2022). Scholars have also explored their impacts on climate policymaking and justice (Wonneberger and Vliegenthart Reference Wonneberger and Vliegenthart2021; Auz Reference Auz and Rodríguez-Garavito2022), the finances and operations of fossil-fuel firms (Setzer Reference Setzer and Rodríguez-Garavito2022) or the evolution of transnational climate law and discourses (Jodoin et al. Reference Jodoin, Snow and Corobow2020; Paiement Reference Paiement2020; Piedrahíta and Gloppen Reference Piedrahíta, Gloppen and Rodríguez-Garavito2022; Setzer et al. Reference Setzer, Silbert and Vanhala2024). There is comparatively less research aiming to explain the socio-legal processes and factors that have shaped the emergence of rights-based climate cases in the first place (Iyengar Reference Iyengar2023, 2) and even less that has relied on empirical methods to do so (Vanhala Reference Vanhala and Rodríguez-Garavito2022b).

Many legal scholars have pointed to the roles that the domestic legal context, trends in case-law and advances in climate science play in enabling or constraining climate litigation across jurisdictions and regions (Marjanac and Patton Reference Marjanac and Patton2018; Peel and Lin Reference Peel and Lin2019; Peel et al. Reference Peel, Osofsky and Foerster2019; Setzer and Benjamin Reference Setzer and Benjamin2019; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2013). Garofalo’s account of the proliferation of Urgenda-like cases in Europe emphasizes the complementary role played by legal opportunity structures and the preferences and values of litigants (Garofalo Reference Garofalo2023). She argues that climate litigators have tailored their legal strategies in response to the domestic rules on standing and the availability of judicial review as well as to align with their mission and previous experience with litigation. Lin and Peel’s explanation of the emergence of climate litigation in the global south emphasizes the key features of the legal system and the wider support structure for civil society advocacy and public interest lawyering in a country (Lin and Peel Reference Lin and Peel2024, 93–145). In addition, Lin and Peel set out five “modes of climate litigation” that focus on the role played by different actors in initiating and leading a climate case, namely: grassroots activists and communities; activist heroic litigators; philanthropic foundations and global NGOs; norm entrepreneurs that promote particular cases; and government lawyers and authorities (Lin and Peel Reference Lin and Peel2024, 195–201). Finally, Iyengar (Reference Iyengar2023) provides a comparable overview of the actors involved in RBCL and draws on interview data to describe their motivations and strategic thinking.

While these authors refer to the role of emerging transnational networks and flows of knowledge, ideas and financial support (Iyengar Reference Iyengar2023, 4; Lin and Peel Reference Lin and Peel2024, 202), these play a marginal role in their analysis. More broadly, the agent-centered approach that is implicit in this existing literature understates the role that social networks, structures and norms play in shaping how lawyers and activists understand the world and decide to engage with the legal system (Faulconbridge Reference Faulconbridge2007; Marshall Reference Marshall, Sarat and Scheingold2006; Marshall and Hale Reference Marshall and Crocker Hale2014; Mason-Case Reference Mason-Case2019; Wang and Soule Reference Wang and Soule2012). As Vanhala has pointed out, additional empirical research is needed to understand the socio-legal processes that influence why and how groups decide to file climate cases, including those related to the resources available to them and the ideas and identities that shape their propensity to use litigation as a vehicle for change (Vanhala Reference Vanhala2022a). Given the transnational nature of climate litigation (Affolder and Dzah Reference Affolder, Dzah and Sindico2024; Osofsky Reference Osofsky2009; Paiement Reference Paiement2024), a complete explanation of the factors that make this type of legal mobilization more or less likely must encompass processes and drivers at the local and global levels.

Analytical framework: understanding legal mobilization in a global context

The transnational diffusion of legal norms and practices across jurisdictions and organizations has been a central concern in contemporary law and society scholarship (Engel and Weinshall Reference Engel and Weinshall2022; Twining Reference Twining2005; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2015). This research has focused on understanding the transnational processes whereby legal ideas, doctrines and rules are articulated, promoted, adopted, translated and contested by government officials and legislators (Halliday and Carruthers Reference Halliday and Carruthers2009; Lloyd and Simmons Reference Lloyd, Simmons, Halliday and Shaffer2015), judges and arbitrators (Claes and Visser Reference Claes and de Visser2012; Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth1996; Slaughter Reference Slaughter2003), legal experts (Brake and Katzenstein Reference Brake and Katzenstein2013; Langer Reference Langer2007) and civil society organizations and activists (Barnes and Burke Reference Barnes and Burke2006; Sikkink Reference Sikkink, Dezalay and Garth2002; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2015).

Despite increasing recognition of the globalization of public interest law and the transnational context that shapes cause-lawyering (Cummings and Trubek Reference Cummings and Trubek2008; Hajjar Reference Hajjar1997; Hoffman and Vahlsing Reference Hoffman and Vahlsing2014; Silva Reference Silva2015), scholars have paid little attention to the transnational diffusion of legal cases or arguments among public interest litigators and litigants (Engel and Weinshall Reference Engel and Weinshall2022, 148). A few studies explore the formation, activities and functions of transnational litigation networks that have emerged in areas of law (Novak Reference Novak2020) or regions of the world (Meili Reference Meili, Sarat and Scheingold2001; Silva Reference Silva2018). Another line of scholarship has examined the transnational processes whereby foreign concepts and vehicles of public interest litigation are adopted and appropriated by domestic lawyers in a particular country (Assis Reference Assis2021; Engel et al. Reference Engel, Klement and Weinshall2018). While this scholarship provides helpful descriptions of the role of transnational networks and actors in supporting forms of lawyering through funding, training and cross-citation, they are more interested in unpacking the ethical implications of diffusion than in explaining how it works (Assis Reference Assis2021; Canfield et al. Reference Canfield, Dehm and Fassi2021; Silva Reference Silva2018).

To understand the processes that shape whether and how legal cases and arguments are diffused across multiple legal systems, we draw on existing research that has explained how transnational networks influence the tactical decision-making and advocacy frames of domestic activists through the generation, dissemination and exchange of resources and knowledge, the development of shared norms and discourses, and the formation of relationships (Hadden Reference Hadden2014; Hadden and Jasny Reference Hadden and Jasny2017; Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Rowen Reference Rowen2012). Our analytical framework emphasizes the role played by the practices of collaboration, storytelling and learning in the emergence and evolution of a transnational field of public interest litigation.

The practice of collaboration refers to the multiple informal and formal ways through which civil society actors work with one another to foster and support public interest litigation across multiple jurisdictions (Meili Reference Meili, Sarat and Scheingold2001; Novak Reference Novak2020). This ranges from providing funding, capacity-building, legal information and strategic advice (Assis Reference Assis2021; Haddad and Sundstrom Reference Haddad and McIntosh Sundstrom2023; Novak Reference Novak2020; Silva Reference Silva2015) to deeper forms of cooperation, such as joint advocacy, including the submission of an amicus brief in cases filed in other jurisdictions (Cichowski Reference Cichowski2016) or establishing formal partnerships to advance a specific case (Hoffman and Vahlsing Reference Hoffman and Vahlsing2014; Duffy Reference Duffy2018, 28–31). Collaboration in a transnational legal context is not just about the exchange of resources and expertise – the symbols, social norms and relationships it generates can shape the strategic preferences and behaviors of lawyers, activists and litigants (Lutz and Sikkink Reference Lutz and Sikkink2001; Sikkink Reference Sikkink, Dezalay and Garth2002). At the same time, tensions may exist: grassroots organizations and affected communities may have very different priorities, strategies and narratives compared to international NGOs or legal professionals (Cole Reference Cole1995; Marshall Reference Marshall2010).

The practice of story-telling encompasses the ways in which civil society actors generate and disseminate narratives in the context of legal cases and trials (Nosek Reference Nosek2018; Paiement Reference Paiement2020). We use the term story-telling, rather than framing, since the former is used by actors in the field of RBCL. It is also more inclusive of how many Indigenous communities understand the nature and practice of law (Napoleon and Friedland Reference Napoleon and Friedland2016). Story-telling involves the strategic arrangement of characters, settings, plots and morals into resonant tales that are articulated and shared through litigation and related communications strategies (Gyte et al. Reference Gyte, Barrera, Singer and Rodríguez-Garavito2022, 291). While actors may engage in storytelling as a strategy of persuasion (Payne Reference Payne2001) or as part of their legal tradition and culture (Napoleon and Friedland Reference Napoleon and Friedland2016; Watt-Cloutier Reference Watt-Cloutier2015), storytelling is an intersubjective practice that involves multiple agents and rests on the cogeneration and internalization of shared norms and discourses (Allan and Hadden Reference Allan and Hadden2017). Litigation has long been shown to be a powerful vehicle for disseminating frames that articulate certain ideas concerning the nature of legal problems, the solutions they require, and their salience to society and particular communities (Jodoin et al. Reference Jodoin, Snow and Corobow2020; Pedriana Reference Pedriana2006; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2015). Lawsuits have accordingly been used by social movements to develop and promote resonant frames that have attracted media and public attention, influenced policy debates and assisted with grassroots mobilization (Marshall Reference Marshall, Sarat and Scheingold2006; McCann Reference McCann1994; Polletta Reference Polletta2000).

Finally, the practice of learning refers to the generation, dissemination and adoption of ideas about the strategic and normative value of legal cases, arguments and tactics as a tool to engender legal, political, economic and social change (Cummings and Trubek Reference Cummings and Trubek2008; Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth2002; Lopucki and Weyrauch Reference Lopucki and Weyrauch2010). Lawyers and affected communities often draw lessons from lawsuits about the best ways of raising awareness of an issue, mobilizing social movements, developing and framing new arguments and norms and making use of legal tools and processes (McCammon et al. Reference McCammon, Hearne, McGrath and Moon2017; McCann Reference McCann2006; Meyer and Boutcher Reference Meyer and Boutcher2007). These lessons may manifest as “copycat” cases that draw on substantially similar legal arguments (Mather Reference Mather1998). Learning about/from litigation is not a purely rational form of strategic decision-making, however. It is embedded in and shaped by the discourses and relationships that emerge in a field of legal practice (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth2002; Marshall Reference Marshall, Sarat and Scheingold2006; Meyer and Boutcher Reference Meyer and Boutcher2007). Learning, especially in the context of a cause or community, typically occurs through “peer scaffolding,” understood as a “mode of engagement in which individuals are supported in their capacity to hope” (McGeer Reference McGeer2004, 118). This type of learning involves identifying and using pathways through which collective hope can be realized “under real-world constraints and collective limitations” (Ibid., 125). For activists and lawyers, the knowledge of another case’s existence or success may matter less as pure informational inputs than for the feelings of collective hope and the sense of possibility and solidarity that it may inspire (Kleres and Wettergren Reference Kleres and Wettergren2017; Nairn Reference Nairn2019).

We combine this focus on the role of transnational practices with two main accounts drawn from the scholarship on the local determinants of legal mobilization (Vanhala Reference Vanhala2022a).Footnote 2 Some scholars posit that an organization’s decision to mobilize law hinges on its ability to generate and access the material and ideational resources needed to initiate strategic litigation, including funding, legal knowledge and strategic acumen (Aspinwall Reference Aspinwall2021; Epps Reference Epps1998; Marshall Reference Marshall, Sarat and Scheingold2006). Others argue that an organization’s decision to initiate litigation is influenced by ideas and beliefs concerning the law and its potential as a tool for social justice (Barclay et al. Reference Barclay, Jones and Marshall2011; Marshall Reference Marshall, Sarat and Scheingold2006). This includes how activists and lawyers understand the meaning and value of different types of legal arguments and strategies (Meyer and Boutcher Reference Meyer and Boutcher2007; Pedriana Reference Pedriana2006; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2009).

We posit that the transnational practices of collaboration, storytelling and learning can influence the local determinants of legal mobilization through three pathways. An enabling pathway involves the production, pooling, distribution and use of the resources needed to initiate a lawsuit (Iyengar Reference Iyengar2023; Novak Reference Novak2020). This pathway encompasses both material and ideational resources – funding, staff, legal information and expertise – that make it possible for cause lawyers, NGOs and communities to file a lawsuit (Aspinwall Reference Aspinwall2021). A discursive pathway encompasses the generation, diffusion and internalization of intersubjective beliefs that define the legal nature of problems and how they should be addressed inside the courtroom (Allan and Hadden Reference Allan and Hadden2017; Gillespie Reference Gillespie2008; McCammon et al. Reference McCammon, Hearne, McGrath and Moon2017). Shared understandings of legal problems and how they should be addressed can spread within a social movement over time and reach a point where they are taken for granted by organizations and lawyers (Coglianese Reference Coglianese2001; Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998). Finally, a relational pathway consists of the social influence of peers and communities on the beliefs and identities of lawyers and activists and their understanding of the appropriateness and meaning of litigation as a tactic for advancing social change (Vanhala Reference Vanhala2018). When actors identify strongly with a transnational community of practice that is defined by a shared set of norms, this may give rise to a process of acculturation whereby an organization’s decision-making is influenced by the behaviors and beliefs of its peers (Wang and Soule Reference Wang and Soule2012).

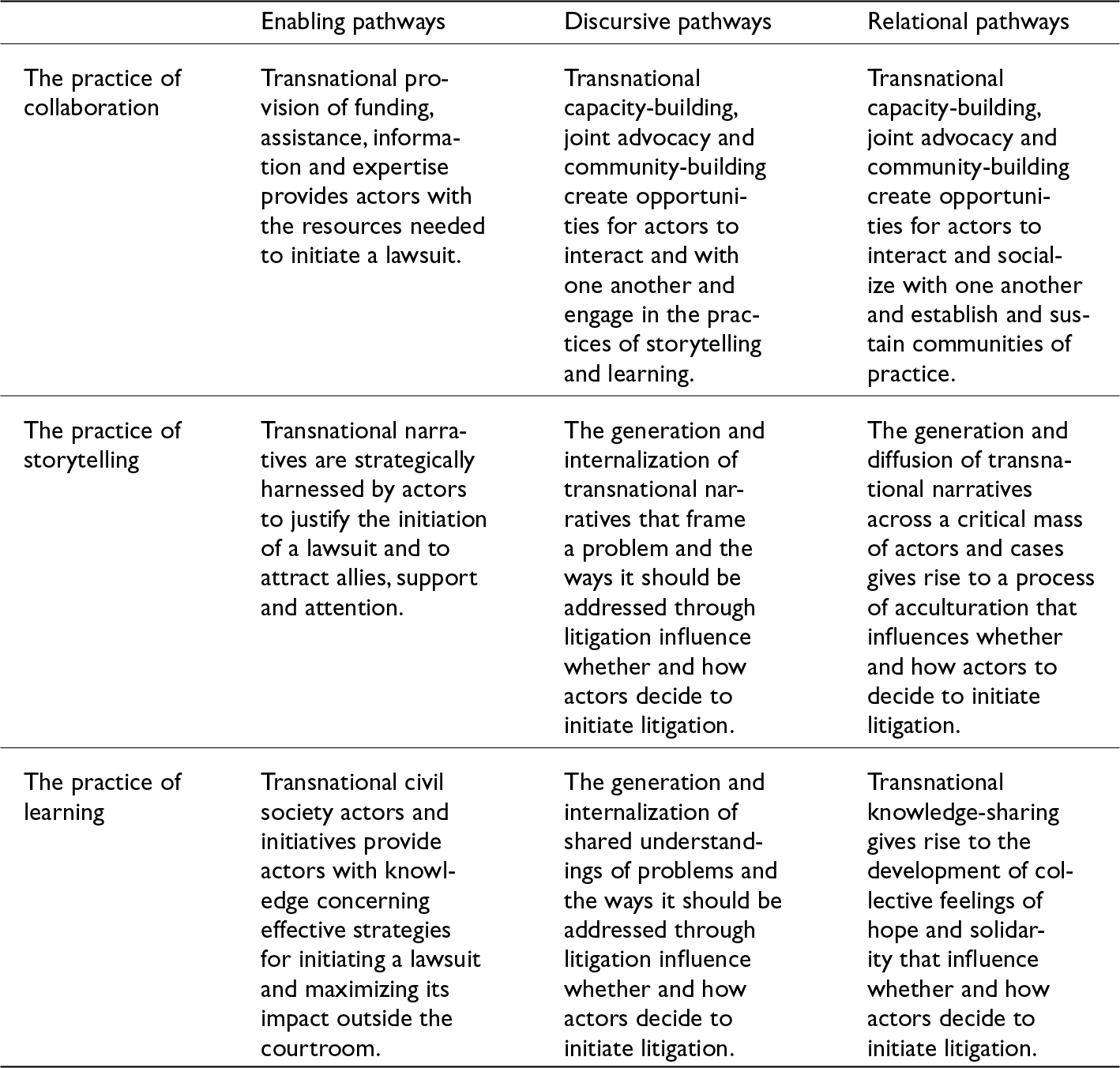

Although we have presented each practice and pathway as distinct phenomena, the truth is that they intersect with one another (Table 1 below). Each of the practices can affect the enabling, discursive and relational pathways that influence whether and how lawyers, activists and litigants decide to file a public interest lawsuit. Moreover, these practices are typically performed in an iterative manner that fosters and sustains their performance. Collaboration is not simply about the production, pooling, distribution and use of resources. It also facilitates the practices of storytelling and learning by generating opportunities for ongoing interaction and socialization between lawyers, activists and communities. Although storytelling is primarily about the generation, diffusion and internalization of transnational narratives that frame a problem and how it should be addressed, it can also be performed in a strategic manner to attract support and allies for cases and can also exert relational influence through acculturation over time. Finally, the practice of learning entails the generation and diffusion of knowledge concerning the most effective strategies for building and promoting different types of lawsuits, shared understandings that shape why and how a case should be filed and the development of collective feelings of hope and solidarity between lawyers, activists and communities across borders.

Table 1. Transnational practices and the local determinants of legal mobilization

Data and methods

Our article relies on practice-tracing (Pouliot Reference Pouliot, Bennett and Checkel2015), an inductive method that entails developing thick explanations of how actors perform practices – “the socially meaningful patterns of action which, in being performed more or less competently, simultaneously embody, act out, and possibly reify background knowledge and discourse in and on the material world.” (Adler and Pouliot Reference Adler2011b, 3). Practice-tracing emphasizes the role of communities of practice in generating and sustaining the tacit norms and shared knowledge that gives practices their meaning, thereby shaping how these practices are performed and the ways in which they are evaluated by their practitioners (Adler Reference Adler2011b, 17). It is also sensitive to the tensions and contestations that can emerge between actors over the performance and assessment of practices (Adler Reference Adler2011b, 21).

We draw on and combine multiple streams of evidence in our practice-tracing analysis of the transnational legal process associated with the emergence and spread of RBCL. First, we draw on our long-term immersion and ongoing participation in the field of RBCL, which has provided us with unique insights and access to key actors and events.Footnote 3 This deep involvement has allowed us to develop a rich understanding of the practices, dynamics and challenges within this field, enabling us to conduct a nuanced and contextualized analysis of the transnational practices of RBCL. Our insider knowledge has facilitated the identification of relevant cases, helped us establish trust and rapport with those involved, including interviewees, and provided us with opportunities to observe and participate in critical events and discussions. However, we acknowledge that our involvement in this field may also influence our perspective and interpretation of the data. To mitigate potential biases, we have employed several strategies, such as triangulating our findings across multiple data sources, seeking feedback from colleagues and experts in the field and critically reflecting on our positionality throughout the research process. Furthermore, we have chosen to interview each other to critically capture our observations as participants in the day-to-day processes of RBCL. This approach allows us to maintain a degree of critical distance and avoid disclosing information that could be detrimental to the collaborators involved in the diverse cases and meetings in which we have participated.

Second, we draw on 135 semi-structured interviews conducted with lawyers, activists, litigants, members of affected communities, NGO representatives and scholars (see Annex 2 for a list of interviewees). These actors operate at different levels (local, national, regional and international) and engage with RBCL in various capacities, such as providing legal representation, organizing advocacy campaigns, sharing expertise or conducting research. While some individuals may have overlapping roles, we have categorized them based on their primary function in the context of RBCL. We used a non-probabilistic sampling strategy to select our interviewees (Tansey Reference Tansey2007) and focused on interviewing individuals who were directly involved with key cases and networks in the field of RBCL. We combined this purposive approach with snowball sampling and sought to recruit individuals that our interviewees identified as key informants willing and able to share knowledge concerning the transnational spread of various types of rights-based climate cases across different regions (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Scott and Geddes2019). In these interviews, we asked open-ended questions to capture the experiences, perspectives and insights of individuals directly involved in RBCL and advocacy (Aderbach and Rockman Reference Aderbach and Rockman2002). The questions covered topics such as the motivations behind filing a case, the conditions that shaped their decision and ability to initiate litigation, the role of transnational support and ideas in their cases, their relationships and collaborations with other actors in this field, the influence of other cases on their litigation strategies and the perceived impact of their activities on other cases. We conducted these interviews in a conversational manner, allowing the interviewees to elaborate on their experiences and share anecdotes that provided rich context for understanding the practices and dynamics at play in this field. This inductive approach, in which the focus of our interviews was open and malleable, was aimed at capturing “the stock of inter-subjective and largely tacit know-how that crystallizes the social meaning(s) of a pattern of action” in our field of study (Pouliot Reference Pouliot, Bennett and Checkel2015, 250).

Third, we analyze formal legal sources, including judicial decisions, dissenting and concurring opinions, legal petitions, related documents such as witness statements and expert reports, and amicus curiae briefs. To this end, we developed an original dataset based on a three-pronged approach to document collection. First, we extracted cases meeting our RBCL definition from the leading climate litigation databases, namely those maintained by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, and cross-checked results against cases discussed in the literature. Second, we conducted online searches of court websites, legal repositories, and other public sources to locate additional documents. Finally, we contacted individuals and organizations directly involved in the cases to fill the remaining gaps. The resulting dataset comprises briefs and judgements from 142 domestic and 32 international rights-based climate cases. In total, we collected 155 briefs from 116 different cases and 122 decisions from 87 cases, representing 76% and 57%, respectively, of the 153 cases analyzed. This means that we successfully retrieved 82% of relevant submissions and 97% of judgements, with gaps primarily due to confidentiality concerns in cases still pending judgment. We then performed a systematic analysis of this entire dataset, coding for key elements such as types of legal arguments advanced by plaintiffs and the inclusion of claims filed on behalf of equity-seeking groups such as women, children and youth, older persons, Indigenous Peoples and persons with disabilities. Throughout our article, we use descriptive statistics to identify trends and relationships across cases.

Finally, we draw on other primary sources and secondary sources, including NGO reports and websites, academic literature and media (newspapers, podcasts and documentaries). Reflecting the complementary role that quantitative data plays in uncovering the patterns that underlie and reflect the performance and effects of practices, we rely on the search results of a media database and Google Trends data in parts of our analysis (see Annex 3 for full details of our search protocol).

Tracing the transnational practices and diffusion of RBCL

In this section, we trace the role played by the transnational practices of collaboration, storytelling and learning in the diffusion of rights-based climate cases across legal systems. This analysis explains how these practices have been performed by lawyers, activists, communities, NGOs and scholars, the shared and changing standards through which they acquire meaning and are assessed, and how they have influenced the local determinants of legal mobilization in the field of RBCL.

The practice of collaboration

Since 2005, lawyers, activists, plaintiffs, communities, NGOs and scholars have engaged in sustained and growing efforts to support, promote and enhance the use of human rights litigation to tackle climate change across legal systems. Over time, these formal and informal behaviors and interactions have given rise to a practice of collaboration. This consists of the performance of actions such as providing funding or organizing meetings and the development of intersubjective standards that shape how practitioners understand the meaning and ethics of transnational collaboration. There are three main ways in which collaboration has been practiced, specifically capacity-building, joint advocacy and community-building.

Actors in the field of RBCL have provided different forms of capacity-building that have addressed the gaps in material and ideational resources that can hinder the initiation of cases. Several NGOs and philanthropic foundations have provided funding that has enabled affected communities and lawyers operating with limited resources to build, file and promote rights-based cases in numerous jurisdictions (Interviews 10, 24, 25, 33, 34, 42 & 91). Many lawyers and campaigners we interviewed told us about their efforts to assist others in fundraising for a new or ongoing case or about having received such assistance from others in this field who had more fundraising experience or contacts (Interviews 12, 43, 51, 55, 56 & 80). In addition to funding, NGOs and practitioners in this field have provided training and other forms of technical assistance to support the filing of rights-based climate cases in other jurisdictions. This assistance ranges from the dissemination of knowledge and resources to advising on legal strategy, the selection of expert witnesses, the presentation of climate science and the design of public and grassroots communications campaigns (Interviews 28, 31, 34, 120, 131 & 133). For instance, a lawyer working for an international NGO shared with us how her organization facilitated knowledge-sharing and strategy development:

My organization started hosting climate litigation trainings, and … there were some lawyers thinking about this strategy [of litigation targeting fossil fuel companies]. … My organization’s a little complicated because we work internationally, but we work behind the scenes with lawyers working domestically. So there was a moment in time where lawyers in the Philippines were bringing together “international experts” to help devise a strategy to address climate change. (Interview 71)

This collaborative approach to capacity-building has been crucial in enabling cases to be brought forward, particularly in resource-constrained contexts (Interviews 12, 31, 120 & 131). As one campaigner who benefited from the technical assistance offered by the Climate Litigation Network (CLN) testifies, “[their] help was enormously valuable both in tactics and in the legal issues” (Interview 30), with another declaring that “we would never have been able to bring this case had it not been for Urgenda in the Netherlands” (Interview 35). In addition, NGOs and affected communities have participated in collaborative communications campaigns aimed at promoting certain cases, disseminating their legal arguments or shaming states for opposing rights-based climate lawsuits (Interviews 15, 34 & 38). Lawyers and NGOs engaged in these cases have frequently submitted an amicus brief in support of cases initiated in another jurisdiction (Interviews 119, 120, 131 & 133). Given the limited resources and word counts at the disposal of the plaintiffs, the submission of amicus briefs can play a key role in bolstering the legal arguments brought by the plaintiffs in a case (Cichowski Reference Cichowski2016). In RBCL, human rights experts and NGOs have filed amicus briefs specifically to “make the human rights case for [plaintiffs] stronger” (Interview 67).

Lawyers and activists based in different jurisdictions have regularly collaborated with one another to develop and file new rights-based climate cases (Interviews 6, 25, 132 & 133). The first rights-based climate case, the Inuit petition, is the product of a collaborative effort between two American NGOs, a prominent Inuit activist, Sheila Watt-Cloutier and a lawyer based in Nunavut (Watt-Cloutier Reference Watt-Cloutier2015). Joint advocacy can also take place within a larger NGO, whereby a team of lawyers specializing in RBCL will cooperate with the members of their local branch (Interviews 120 & 127). As a youth campaigner points out, the resulting partnership often benefits both parties: “I don’t think the lawsuit would have been as successful if they would have done it alone because [we] have something that [they] don’t have and that is that it is a grassroots membership-based organization with people under the age of 25 [who served as plaintiffs in the case]” (Interviews 10, 15, 29 & 30).

Finally, actors in this field have developed community-building initiatives dedicated to supporting and advancing rights-based climate lawsuits. Initiated by the Urgenda Foundation in 2015, the CLN aims “to support climate cases worldwide” following the Foundation’s own historic victory before the Dutch courts (Urgenda Foundation 2024). On the other side of the Atlantic, Our Children’s Trust (OCT) is a public interest law firm that has filed youth-led climate litigation in the United States and supported “locally-led partner efforts by providing legal, outreach, and communications assistance and expertise” at a global level (Our Children’s Trust (Youth v. Gov) 2024b). Further, environmental NGOs have created teams and networks dedicated to rights-based climate justice, including Greenpeace International (Interviews 18 & 120), Client Earth (Interviews 13, 27, 34 and 38) and De Justicia (Interview 119). The most prominent rights-based climate cases have all been developed and filed in collaboration with at least one global organization or network (Interviews 15, 18 & 32). The importance of these networks is underscored by many of our interviewees, such as a lawyer reflecting on the success of a landmark case in which they were involved as an independent expert:

Even though it was a case brought before a national human rights commission, of course, there was Greenpeace International and Amnesty International, you know, and their respective support networks. That is number one. Number two, it was the local people’s organization … When these two come together … you can create the momentum (Interview 67).

Even if the initial case itself is not developed in collaboration with key actors, the filing of a case often serves as an opportunity for lawyers and activists involved in local cases to build ties with the people and organizations at the heart of these transnational communities of practice (Interviews 21, 41 & 120).

In addition to these established networks and programs, community-building is practiced through routine, informal relational processes that occur across organizations and cases. Lawyers, activists and scholars have regularly interacted with one another through cooperation on specific lawsuits (Interviews 14 & 15) and meetings held with the express purpose of bringing people together to brainstorm, build capacity and foster collaboration (Interviews 40, 119, 132 & 133). These get-togethers are usually closed-door to allow for sharing of confidential or otherwise sensitive information about ongoing or potential litigation, to allow participants to know “who is doing what” and “ensure everyone is aligned” (Interviews 33 & 132). One of our interviewees, who works for an organization that filed a major international climate case, provides an example of such community-building efforts:

We facilitated a convening on climate force displacement for indigenous peoples, and First Nations peoples in 2018. And brought the tribes from Louisiana to Alaska along with community-based organizations and clans from the South Pacific, and have continued to build those connections outside of Alaska since that time (Interview 66).

The practice of collaboration has contributed significantly to the spread of RBCL. Our findings suggest that resource and knowledge flows between the Global North and the Global South, as well as within and across regions, have facilitated the rapid transnational diffusion of this litigation (Interviews 18, 27, 31 & 106). Capacity-building initiatives, such as funding, technical assistance and training provided by NGOs and networks, have played a crucial role in enabling activists and lawyers globally to develop and file rights-based climate cases. This aligns with the broader literature on climate litigation in the Global South, which has emphasized the significance of transnational support and expertise in overcoming resource constraints and legal barriers in the Global South (Urgenda Foundation, n.d.). At the same time, our findings confirm Peel and Lin’s (Reference Peel and Lin2019) suggestion that these cases also benefit from partnerships with local NGOs, academics and lawyers (Interviews 59, 71, 72 and 75).

Yet the practice of collaboration does not only operate through an enabling pathway of influence. In fact, for many of the actors in this field, collaboration is explicitly about cultivating a shared sense of community. Capacity-building and joint advocacy initiatives can create transnational bonds between lawyers, activists and communities across cases – as one NGO lawyer explains: “there might be a law clinic in the US thinking about what is happening in Norway or a law clinic in Canada thinking about what is happening in the Philippines” (Interviews 34, 33 & 41). Some NGOs have convened meetings specifically aimed at fostering solidarity and a common purpose amongst activists and lawyers involved in RBCL in different jurisdictions (Interviews 15 & 34). The importance of such solidarity is highlighted by one of the petitioners in a landmark climate case:

We’re … in constant communication with other lawyers from the other cases around the world … and it was an amazing thing, that it’s like … a global movement. … It’s like, cross operation altogether … not just for the technicalities of the case, but also the solidarity, knowing that we’re not alone, and there are other people who are taking the same path, like us. And that’s strength building, you know, for me, at least, personally, I can say, yeah, so that’s the value and the beauty of the process (Interview 73).

Collaboration like this has created and deepened ties between lawyers, activists and experts in the fields of environmental law and human rights. This represents a significant change as human rights organizations had long been reluctant to work on climate change, while environmental organizations were initially cautious about the explicit use of human rights in their advocacy (Allan Reference Allan2020, 121–45; Interviews 33, 43 & 102). Environmental lawyers have thus sought out advice from key human rights lawyers to ensure that their cases don’t entail “something that could be adverse or set a bad precedent or get a finding that wouldn’t work” (Interview 120, 33 & 43).

At the level of ethics, several international lawyers and activists we spoke with highlighted the challenges of transnational litigation partnerships involving participants with differing resources, priorities and worldviews. An international lawyer supporting dozens of climate cases conveyed that “what we want is authentic litigation that is brought in the country that represents what the communities want, what is best for the society there” (Interviews 33 & 34). This emphasis on local leadership is increasingly shaping how collaboration is performed by lawyers, activists and communities and may eventually define not only what counts as ethical or unethical forms of collaboration but also transform the very meaning of collaboration as a practice, distinguishing it from what actors might define as exploitative relationships or arrangements.

The practice of storytelling

Lawyers, activists and plaintiffs have used RBCL as a vehicle to articulate and share stories about the climate crisis, its injustices and the role that human rights should play in response. In what follows, we analyze the four main narratives that have been articulated and reiterated through RBCL and explain how they have inspired lawyers and activists to bring different types of cases across multiple jurisdictions. The first narrative to emerge through rights-based climate lawsuits emphasized the adverse impacts of climate change on human rights and the disproportionate and uneven nature of the burdens borne by certain groups in the climate crisis. This narrative was first articulated in the petition filed by Inuit communities before the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) in 2005 (Jodoin et al. Reference Jodoin, Snow and Corobow2020). Drawing on the lived experience of Inuit communities on how global warming was disrupting their rights to life, safety, lands, and traditional cultures and livelihoods, the Petition argued that global warming threatened the “right to be cold” of Inuit communities in the Arctic (Watt-Cloutier Reference Watt-Cloutier2015). As one human rights activist explained to us, the petition “brought the human face to climate change to the forefront of peoples’ discourse” (Interviews 106 & 117).

This narrative has been reflected and reiterated in many of the rights-based climate cases launched during the past 17 years. A prominent example is from the Philippines, as shared by a lawyer representing affected communities:

We had people from an island in Quezon, Allabat Island, they were always suffering from typhoons. And they talked about the, you know, that how they were subjected annually to heavy rains, floods, you know, and, and the intensifying hurricanes. They told their stories. … And you can even see how important it was because the commissioners were interested, you know, on the sufferings that they’ve gone through (Interview 70).

As participants in the field, we have witnessed firsthand the power of this narrative in mobilizing affected communities and inspiring new rights-based climate cases. To bolster the storyline regarding the uneven impacts of climate change, these lawsuits typically include evidence that refers to climate science as well as testimonials of the concrete ways in which the climate crisis undermines the rights of the plaintiffs (Mathur et al. v. Ontario, 2020; Torres Strait Islanders Petition, Reference Billy2022). Emphasizing the disparate impacts of climate change on certain segments of the population, many of these cases argue that states must address climate change to respect and fulfill the right to equality protected under human rights law. Our systematic analysis reveals that approximately 44% of the cases in our dataset claim explicitly that climate change has disproportionately affected the rights of a particular group within society.

A second influential narrative stresses the disproportionate impacts of the climate crisis on children and youth and emphasizes their role and agency as activists fighting for intergenerational climate justice. This storyline was first articulated in a series of cases launched by OCT and is most closely associated with Juliana v. United States. In Juliana, 21 youth plaintiffs argue that the US government’s fossil fuel policies and inaction in the field of climate change infringe on their due process rights to life, liberty and property and are contrary to the government’s fiduciary duties under the public trust doctrine (Juliana v. United States 2020). Building on the first narrative, the Juliana case helped, in the words of a lawyer from the United States who was not involved in the case,

tell the story that climate change was happening in the United States in a moment where people thought of climate change as this really far off thing that was happening to other countries, to people in other countries who were having to get on boats and cross oceans, that had nothing to do with us (Interview 71).

The story told in this case specifically emphasizes that young people have a fundamental right to a stable climate that is capable of sustaining life and highlights the intergenerational injustices associated with the climate crisis. The Juliana storyline of youth vulnerability and agency has been reflected in the extensive media coverage that it has generated in newspapers, radio, television and social media (Our Children’s Trust (Youth v. Gov) 2024a). Of the 1,008 articles referencing the Juliana case found in the Nexus Uni database of newspaper articles (Lexis Nexis Reference Nexis2024) from 2005 to 2022, 74% use the term “youth,” while only 11% refer to “climate science,” 14% use the words “human right” and 20% use the term “public trust.”

Coinciding with a period in which young people became increasingly active and visible in the climate movement, the narrative articulated in Juliana captured the imagination of many climate lawyers and has been recast in dozens of climate cases launched to protect the rights of children and young people from the current and future impacts of climate change around the world (Donger Reference Donger2022; Parker et al. Reference Parker, Jodoin and Wewerinke-Singh2022). Several interviewees shared with us that the story told in the Juliana case and the media coverage that it attracted inspired them to develop a climate case focused on the rights of young people (Interviews 5, 100, 119, 127 & 134). Our analysis reveals that 34% of rights-based climate cases have included youth and children as plaintiffs and conveyed in different ways the generational threats posed by the climate crisis. Youth-led lawsuits have not simply reproduced the narrative of intergenerational climate injustice first introduced by OCT; they have enriched it by recasting it in light of the lived realities of climate change for young people around the world and domestic legal norms and discourses.

In cases such as Ridhima Pandey v. Union of India (2019) and Mbabazi v. Uganda (2012), youth plaintiffs from the Global South have played a pivotal role in reshaping the discourse around climate change litigation. These cases are distinct not only for their emphasis on the experiences of young people but also for their focus on the unique vulnerabilities faced by youth in developing countries. What sets these cases apart is their explicit invocation of intergenerational equity, which underscores the ethical and legal responsibility to preserve the planet for future generations. While not directly targeting historical polluters, these cases may indirectly contribute to a more inclusive form of climate justice by highlighting how socioeconomic disparities exacerbate the vulnerability of youth in the Global South.

In the landmark case of Demanda Generaciones Futuras v. Minambiente (2018) the Colombian Supreme Court confronted the issue of deforestation in the Amazon, a matter with profound implications for Colombia and the global climate. The plaintiffs, a group comprising 25 young people, argued that the Colombian government’s failure to adequately address deforestation constitutes a direct threat to their fundamental rights to life, health and a healthy environment, as well as those of future generations. The Court’s ruling was groundbreaking in its express recognition of the rights of future generations in connection with climate change. By ordering the government to formulate and implement an “intergenerational pact for the life of the Colombian Amazon,” the Court not only emphasized the intrinsic value of environmental stewardship but also acknowledged the deep interconnections between human rights and environmental health (Demanda Generaciones Futuras v. Minambiente 2018). At the same time, this ruling sets an important precedent for incorporating the voices and rights of youth and future generations within the judicial processes addressing climate change.

In Neubauer, et al. v. Germany (2021), a group of teenagers and young adults argued that the inadequate emissions reduction target included in Germany’s 2018 Federal Climate Protection Act violated the principle of human dignity, the right to life and physical integrity and the constitutional duty to protect the natural foundations of life for future generations. The Federal Constitutional Court struck down parts of the German Federal Climate Change Act as incompatible with the youth plaintiffs’ constitutional rights and ordered the German government to adopt more ambitious emissions reduction targets for 2030. In its judgement, the Court recognized that Germany had a duty to protect life and health against the risks posed by climate change and was also obliged to preserve the freedom of future generations by not “unilaterally offloading” the burdens of reducing carbon emissions to future generations (Neubauer, et al. v. Germany 2021, 6). In doing so, the Court has extended the narrative of intergenerational justice to encompass not only the unequal burdens caused by climate impacts, but also those associated with having to adopt drastic measures to reduce carbon emissions in a shorter time-frame due to delayed and ineffective climate action.

A third transnational narrative to emerge from the field of RBCL stresses the legal obligation of governments to take action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) GHG emissions in accordance with the recommendations of climate scientists. First launched in 2013, the Urgenda case argued that the failure of the Netherlands to reduce national GHG emissions to 25–40% below the 1990 level by 2020 violated its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) as well as the duty of care it owed to its citizens under extra-contractual law (Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands 2020). While previous cases used science to establish that climate change threatened human rights and could be attributed to the conduct of states, the Urgenda case claimed that states were obliged to align their emissions reductions targets with the recommendations of climate scientists, as expressed in the reports issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (Paiement Reference Paiement2020, 140). In 2019, the Dutch Supreme Court determined that the Netherlands had indeed violated the rights to life and to private and family life, under Articles 2 and 8 respectively of the ECHR, by failing to take the necessary measures to reduce its GHG emissions and protect its population from the risks of climate change (Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands 2020).

The Urgenda narrative that states are obliged to reduce their GHG emissions in line with the dictates of climate science to fulfill their human rights obligations has been clearly reflected in this case’s media coverage. Of the 976 articles that refer to the Urgenda case in the Nexus Uni database of newspapers (Lexis Nexis 2024) from 2013 to 2022, we found that 100% of articles included the words “climate science,” 39% included the words “human right,” 26% included the word “accountable,” 30% included the word “duty,” 31% included the word “obligation” and 17% included the word “constitutional.” The Urgenda narrative has also been reproduced and strengthened through a wave of “systemic climate mitigation” lawsuits that “challenge the overall effort of a State or its organs (…) to mitigate dangerous climate change, as measured by the pace and extent of its GHG emissions reduction.” (Maxwell, Mead, and Berkel Reference Maxwell, Mead and van Berkel2022, 36) Our systematic analysis of RBCL shows that close to 40% of cases fall within this broad category and that 16% of cases focus specifically on the inadequacy of emissions reduction targets. Many of the interviewees involved with these Urgenda-like cases confirmed the role that this case played in promoting the story of state accountability for climate inaction and their intention to promote this narrative in their jurisdiction (Interviews 1, 123, 133 & 134). This narrative has been especially bolstered by the successful outcomes in Neubauer, et al. v. Germany (2021), Notre Affaire à Tous and Others v. France (2021) and Klimaatzaak v. Kingdom of Belgium (2023). Each lawsuit that advances a similar argument and each judgement that sides with the plaintiffs helps disseminate and translate the Urgenda narrative to a different political and legal environment and bolsters its credibility at a transnational level (Interviews 6, 7 & 134).

A more recent narrative to emerge from RBCL focuses on the responsibility of corporations in the climate crisis. In 2015, Greenpeace Southeast Asia, the Philippine Rural Reconstruction Movement, and a coalition of 12 NGOs and around 1,300 individuals petitioned the Philippines Human Rights Commission to open an investigation on the human rights impacts of climate change and the related responsibilities of global companies involved in the production of oil, natural gas, coal and cement (known as the “carbon majors”). The Commission accepted the petition in 2017 and released a final report in 2022 in which it found, among other things, that the carbon majors had contributed to 21.4% of global emissions had obfuscated climate science and delayed and hindered the transition away from fossil fuels and could be held accountable under Philippine law for having done so (Carbon Majors Decision 2022). Another prominent major rights-based corporate climate case was filed in the Netherlands in April 2019. Milieudefensie/Friends of the Earth Netherlands, seven other NGOs, and 1,700 citizens initiated a class action against Royal Dutch Shell for violating its duty of care to Dutch citizens by failing to reduce its GHG emissions and promoting climate disinformation (Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell 2021). In a judgement rendered in May 2021 and that has been appealed, the Hague District Court held that Shell had a duty to prevent dangerous climate change under Dutch civil law and ordered the company to reduce its carbon emissions by 45% by 2030, relative to 2019 (Ibid., 44).

These two cases and the global attention that they have attracted from activists and journalists around the world have generated a transnational narrative that emphasizes that carbon majors can be held responsible for the human rights impacts of their contributions to the climate crisis (Interviews 3 & 6). This narrative has legitimized the notion of initiating human rights litigation against corporations for their role in causing the climate crisis. One lawyer we interviewed opined that the inquiry demonstrated that “a systemic shift should be in the play” (Interview 9) instead of, as another lawyer put it, “put[ting] the guilt on the individual” (Interview 3) as per the narrative that Shell and other fossil fuel companies had been promoting. Another lawyer highlighted the role of the Hague District Court’s ruling against Shell in helping “the public opinion understand [sic] that fossil fuel companies aren’t normal companies [because] they have a more severe impact and they have a more threatening product than any other company” (Interviews 1 & 56). For those directly affected by the adverse effects of climate change, the story told through the petition and the inquiry is empowering: as one of the petitioners explains, it “shows that even if you’re just a grassroots community … you can actually … challenge the big corporations for their business practices” (Interview 74). This makes the inquiry “very powerful, and not just for the Philippines, but for other vulnerable communities, because as we feel helpless, there is power in our vulnerability, there is power in our experience, there is power in our stories” (Interview 74).

We found that these four narratives have resonated with lawyers, activists and affected communities and have played a key role in inspiring them to launch new rights-based climate cases (Interviews 117, 119, 120, 123, 130, 131, 132, 133 & 134). As we discussed above, a broad array of lawyers, activists and affected communities have generated and internalized the storylines of human rights vulnerability, agency and accountability told through these cases. Discouraged by the failures and injustices associated with international and domestic policy processes in the field of climate change and in line with a broader discursive turn to climate justice (Beauregard et al. Reference Beauregard, Carlson, Ann Robinson, Cobb and Patton2021; Hadden Reference Hadden2015), many climate lawyers and activists have become persuaded of the appropriateness of mobilizing human rights law to address the impacts of the climate crisis, share and amplify the stories of those most affected by it and secure legal remedies to hold governments and corporations accountable (Interviews 102, 103, 105, 106, 107, 110, 111, 114, 116, 119, 120, 131, 132, 133 & 134). Each time a rights-based climate case has been filed, it has bolstered the credibility, legitimacy and salience of this transnational narrative and thus enhanced its appeal to lawyers, activists, policymakers, journalists and citizens. In addition to the number of cases, the breadth of jurisdictions to which this type of litigation has spread is also a key to bolstering the credibility of this narrative both in specific regions and as a global phenomenon (Interviews 7, 35 & 41).

The practice of storytelling also has an important enabling dimension. The stories told through these cases have provided a key resource that lawyers, activists and NGOs have used to promote rights-based climate cases, convince others of their feasibility and importance and attract support for their cases (Interviews 9, 35 & 41). Indeed, the potency of the narratives associated with human rights has led many climate activists to realize “that it is also a powerful tool, not only a legal tool but a powerful political and moral tool to gather a social movement around the case” (Interviews 4, 9, 10 & 25). By focusing on the human impacts of climate change, rights-based climate narratives have help bring human rights lawyers, activists and NGOs to the climate justice movement (Allan Reference Allan2020; Interviews 102, 103, 105, 106, 107, 110, 111, 114, 116, 119, 120, 131, 132, 133 & 134). This expansion has increased the transnational pool of potential allies, funding, information and expertise that are known to make legal mobilization more likely (Andersen Reference Andersen2006; Aspinwall Reference Aspinwall2021; McCammon et al. Reference McCammon, Hearne, McGrath and Moon2017).

Finally, storytelling has increasingly supported the diffusion of rights-based climate cases through relational processes of mutual influence. As additional cases have been filed, positive judgements have accumulated and related campaigns and media coverage have flourished, the decision to mobilize human rights to address the climate crisis has increasingly been driven by acculturation (Hadden and Jasny Reference Hadden and Jasny2017; Wang and Soule Reference Wang and Soule2012). As a Norwegian campaigner puts it, there are now “lots of cases which I think have all been inspiring us and telling us that we are not alone in doing this” (Interviews 14, 35 & 38). While it is difficult to distinguish processes of persuasion from those of acculturation in a single case, the increased frequency of cases of RBCL over time (see Figure 1 above) and the patterns through which certain types of cases are proliferating are consistent with the hypothesis that relational pressures are beginning to play a role in the diffusion of lawsuits and arguments at the intersections of human rights and climate justice.

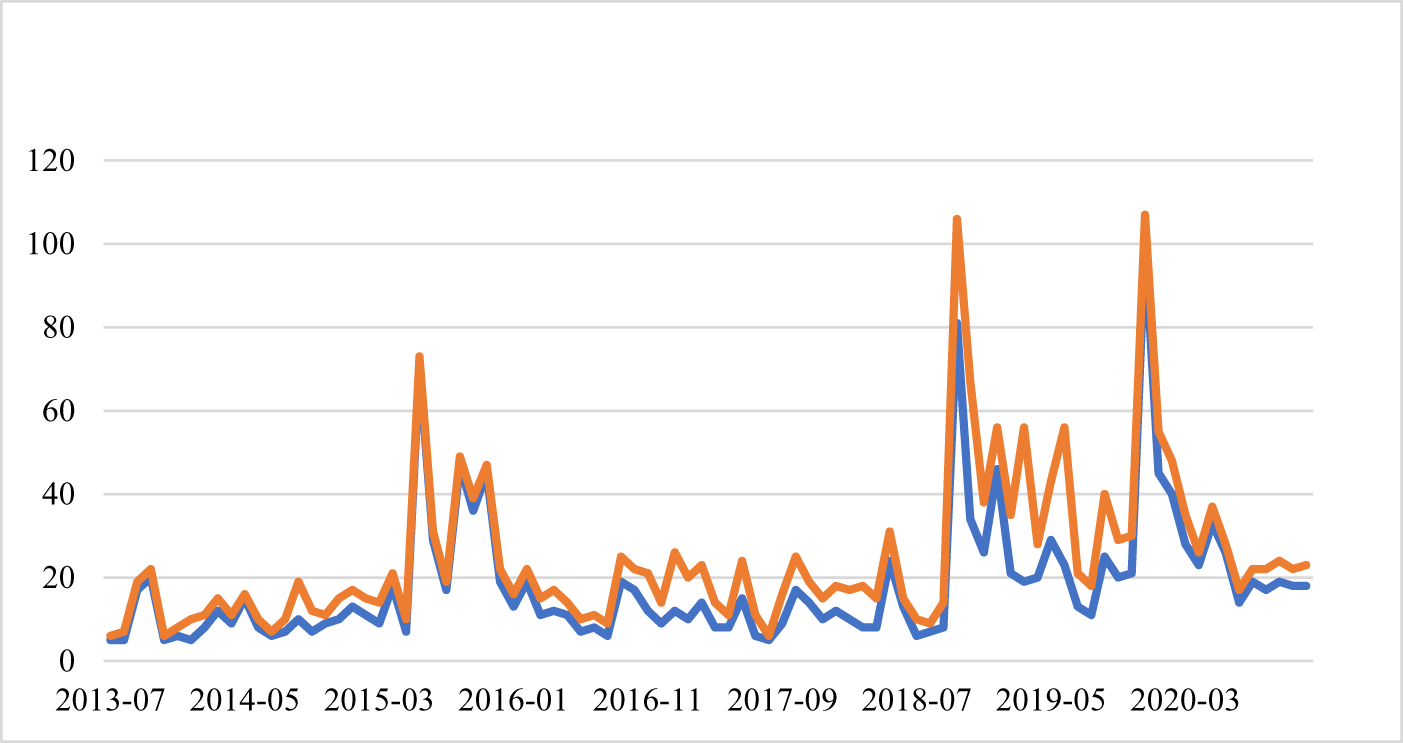

Figure 1. Worldwide Google Trends data for Urgenda and Juliana v. United States, 2013–2020.

The practice of learning

Lawyers, activists, communities and scholars have facilitated and engaged in learning processes of different kinds in the field of RBCL. They have regularly exchanged, coproduced and disseminated information on the status of cases and ideas regarding legal arguments, the significance and use of climate science and strategies inside and outside the courtroom (Interviews 18, 132 & 133). In particular, numerous in-person and online meetings have brought together lawyers, activists and scholars to discuss, share and generate best practices for putting together different types of rights-based climate cases (Interviews 34, 132 & 133). In addition, the litigators and scholars working in this area have also produced a growing body of applied scholarship that explicitly aims to draw lessons from different cases and offers practical recommendations for effectively launching rights-based climate cases (Bähr et al. Reference Bähr, Brunner, Casper and Lustig2018; Maxwell et al. Reference Maxwell, Mead and van Berkel2022).

The media coverage of these cases, social media content and existing relationships and networks active in the fields of human rights or climate change have also fostered opportunities for spontaneous learning. For instance, some of our interviewees shared that they first learned of the success of the Urgenda case by reading media coverage (Interviews 20, 123, 130 & 134). To maximize opportunities for this sort of transnational learning, lawyers and activists have actively promoted their cases by soliciting traditional media coverage, writing books, participating in documentaries, presenting their cases at conferences and meetings organized by civil society, academic institutions and multilateral institutions, sharing their legal documents, often with unofficial versions translated in English, through electronic communications and websites; and generating social media on multiple platforms (Interviews 1, 100, 118, 120, 131, 132 & 133).

Figure 1 below illustrates the online impact and effectiveness of these strategies for two key climate cases over time. Using Google Trends data,Footnote 4 we were able to capture worldwide online search interest in Urgenda (represented by the orange line) and Juliana v. United States (represented by the blue line) from 2013 (the year the Urgenda case was filed) to the end of 2020 (the year that courts in both cases rendered key decisions). This figure evinces the growing interest in these cases during this period as well as the key moments where their search popularity spiked, which coincide with the dates when these cases were filed and when courts rendered decisions. Although levels of interest in Urgenda and Juliana declined between key legal milestones, they nonetheless attracted a sustained level of interest among journalists, climate lawyers and activists and the public at large.

The practice of learning has played a key role in supporting the diffusion of RBCL around the world. A clear marker of the influence of learning is the evidence of the dissemination of specific arguments advanced in pivotal cases. In our systematic analysis of cases, we found that 16% of cases explicitly focus on insufficient emissions targets, a type of argument that first originated in the Urgenda case, and 10% of cases specifically invoke the public trust doctrine, an approach that has been popularized through the Juliana case and promoted by OCT. In fact, the influence of these two cases is greater than these numbers suggest. Urgenda has inspired cases that advance a broader argument relating to state accountability for human rights violations caused by climate change. Juliana has stimulated the development of cases involving youth plaintiffs. Beyond these two pivotal cases, we also found evidence that lawyers and climate activists have derived and applied lessons from the cases of Leghari (Interviews 13, 25, 35 & 41), Demanda Generaciones Futuras (Interviews 119, 25, 39 & 42), and Neubauer (Interview 134).

Transnational earning in the context of transnational processes litigation exerts influence through a complex combination of enabling, discursive and relational pathways. In purely rational terms, the practice of learning refers to the acquisition and strategic application of knowledge concerning the advantages and disadvantages of a particular legal strategy (Lopucki and Weyrauch Reference Lopucki and Weyrauch2010). Lawyers and activists will decide to launch a new case or adopt a particular legal argument based on the lessons they have construed about the success of legal cases and arguments brought elsewhere and their potential benefits for the pursuit of climate justice in their jurisdiction as they have been known to do across causes in the United States (Meyer and Boutcher Reference Meyer and Boutcher2007). With the exceptions of those who were involved in the pioneering cases of the Inuit petition, Juliana and Urgenda, all of the climate lawyers and activists we interviewed confirmed that other cases had played a key role in shaping whether and how to bring a rights-based climate case in their jurisdiction (Interviews 5, 7, 18, 20, 25, 119, 120, 123, 130, 132, 133 & 134). Learning consists here of an interpretive practice that can yield different results based on the context and purposes of the inquiry. For instance, climate lawyers have drawn different lessons from the legal arguments advanced in Urgenda, focusing on how to: link human rights and climate inaction (Interviews 18, 28 & 33), invoke the duty of care in the context of climate inaction (Interviews 1, 3, 4, 20, 29 & 41), challenge the insufficiency of emissions reductions targets (Interviews 19, 31 & 32) or plead climate science and address issues of causation (Interviews 4, 7, 27 & 134). The significant influence of the Urgenda and Juliana cases on the development of subsequent cases is confirmed by our own observations and experiences in the field, with many litigants and activists with whom we have worked explicitly citing these cases as sources of inspiration and learning.

The proliferation of rights-based cases over time has provided opportunities for lawyers and activists to draw and combine lessons from multiple cases. The practice of learning from the Urgenda and Juliana cases has even translated into different types of lawsuits in the same jurisdiction. In Canada, two groups of lawyers and activists were inspired by Urgenda to launch similar challenges to emissions reduction targets (Environnement Jeunesse c. Canada 2019; Mathur v. Ontario 2020), while another group launched a Juliana-style youth-led lawsuit specifically invoking the public trust doctrine (La Rose c. Canada 2023). Meanwhile, many climate lawyers have cited both Urgenda and Juliana as sources of inspiration for developing climate lawsuits (Interviews 119 & 134), and there are many cases that draw on elements of what was understood to be successful about both cases (Environnement Jeunesse c. Canada 2019; Mathur v. Ontario 2020).

While some lawyers appear to believe that lessons about law and litigation are easily transferable across legal systems (Interviews 2, 22 & 31), we found that learning has generally been practiced in a careful manner that has resulted in the translation of legal arguments, rather than their transplantation, across jurisdictions. Aware of the risks and downsides of the mechanical replication of cases, lawyers have generally adjusted legal arguments inspired by other cases to fit with the local legal and political realities of their jurisdictions (Interviews 133, 134 & 135). As one interviewee put it, “internationalization is very important but also context-specific; there is no one-size-fits-all approach” (Interviews 27, 31 & 33). Several interviewees thus stressed the importance of assessing and adapting legal strategies in light of prevailing legal norms (Interview 31), explaining, for example, that the legal arguments invoked in cases such as Urgenda were less likely to convince judges within their own legal system (Interviews 15, 20 & 44). Unsurprisingly, we have found that similarities between different legal systems have indeed facilitated learning-driven diffusion. For instance, the Urgenda case has exerted greater influence in jurisdictions with civil law systems and in states that are parties to the ECHR (Interviews 119 & 133). The Juliana-style public trust cases, meanwhile, have largely been launched in countries that use the common law (Interviews 119 & 133). For a lawyer involved in a rights-based climate case before the courts in India, Ali v. Pakistan was particularly inspiring, in part because the case was seen as most relevant to the Indian context and because of similarities between the Indian and Pakistani legal systems (Interviews 20, 23, 39 & 41).

The discursive pathway in learning in the context of RBCL is apparent when we compare the different “lessons” that have been learned from the Juliana and Urgenda cases and the divisions they reflect in the broader field of transnational climate advocacy (Allan Reference Allan2020; Hadden Reference Hadden2015). Three key questions that have emerged in the field of RBCL concern the ways in which human rights should be plead, the selection of an acceptable target for average increases in global temperature and the means for pleading climate science. The Juliana and Urgenda cases take a different approach to these three questions, and their differing positions are reflected in the waves of cases that they have inspired. The Urgenda case and other similar cases generally argue that governments have violated their human rights obligations, their duty of care or an existing public law by adopting emissions reduction targets that are insufficient to ensure that global average increases in temperature remain well below 2°C and, if possible, 1.5°C, an objective that is enshrined in the Paris Agreement (Maxwell et al. Reference Maxwell, Mead and van Berkel2022). Moreover, Urgenda-like cases typically rely on the authoritative recommendations of the IPCC to establish this temperature increase as the acceptable level of climate change and to determine the emissions reduction targets that states must meet in order to prevent harm to the plaintiffs (Paiement Reference Paiement2020, 131–33).

By contrast, in Juliana-like cases, the plaintiffs argue that governments are infringing fundamental rights and breaching their fiduciary duties to preserve the atmosphere for current and future generations by not only failing to reduce carbon emissions but also because they are subsidizing the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels (Wood Reference Wood, Coghill, Smith and Sampford2013). These cases also argue that governments have an obligation to keep CO2 concentrations below 350 ppm and limit global warming to 1°C. This approach specifically rejects the 1.5°C limit adopted by the IPCC as a “safe target” for global temperature rise (Our Children’s Trust (Youth v. Gov) 2024c) (Our Children’s Trust (Youth v. Gov) 2024c) and thus relies on the scientific research of internationally renowned climatologist James Hansen rather than the reports of the IPCC (Hansen Reference Hansen and James2015).

The different approaches adopted in Urgenda and Juliana and the cases they have inspired are not mundane. They have significant implications for the cost and complexity of bringing a rights-based climate case, for their odds of being successful in court and ultimately for the type of climate justice they seek to advance. The practice of learning in RBCL is ultimately tied to the classic conundrum at the heart of public interest litigation. Is it better to adopt a strategy that has a greater likelihood of success but that may have fewer transformative outcomes (Interview 133)? Or is the pursuit of an incremental case simply a hollow hope that only legitimizes the existing system and the injustices that it reflects (Interview 131)? Although Urgenda is generally perceived as a success story that should be emulated, some climate lawyers are indeed critical of the approach taken by the plaintiffs and the outcomes reached in court (Interviews, 9, 20 & 32). Another climate lawyer shared with us that the targets adopted in the Urgenda case “baffles” them, explaining that “it just really hard for me to think about the duty to do no harm and duty to fully inform our plaintiffs about the difference between 1.5 degrees and 350 PPM” (Interview 131). In justifying their preference for more ambitious types of rights-based climate cases, this lawyer imparted that “all of these principles that are just embedded in my DNA, that’s what I deeply, deeply struggle with. Like I can’t go with practical if practical is going to result in people dying” (Interview 131). On the other hand, the cases that aim for transformative change also attract harsh criticism from other lawyers and activists. For these critics, a more strategic approach takes greater account of the risk of setting a negative precedent and involves closer alignment with existing litigation efforts at the domestic level (Interviews 7, 33 & 44).

A final important finding of our fieldwork is that the relational aspects of learning have been just as critical to the diffusion of RBCL as its strategic and discursive dimensions. Over and over, the climate lawyers and activists we interviewed emphasized that climate lawsuits and judgements had made them hopeful and inspired (Interviews 43, 100, 102, 119, 120, 123, 131, 132 & 134). As one climate lawyer explains, the decision to launch or support a climate case ultimately “stems from the fact that they can be part of a solution that just might work” (Interview 131). For petitioners, filing a case can be about having “grown tired of just being the victims” and “doing something [so that] we’re not just victims, we are getting the justice that we deserve” (Interview 74). Another lawyer described the take-away lessons from Juliana and Urgenda as “exciting, interesting ideas … because they were innovating and because they had shown that courts would be potentially willing to entertain some of those arguments and that, for example, representing young people sends a key communication or message that we wanted to convey” (Interview 119).

To be sure, the credibility of the lessons that can be gleaned from a case is enhanced whenever the plaintiffs are successful (or perceived to be so). There is no doubt that Urgenda’s success in the Dutch courts has played a key role as a source of learning about whether and how to bring a rights-based climate case (Interviews 19 & 20). As one climate lawyer summed up: “if you are starting your own case, you want to look at what worked elsewhere and immediately you bump into Urgenda” (Interviews 27 & 29). Likewise, a campaigner observed that “once it starts and is successful, which was the case with Urgenda … others will follow because we see it can be very effective” (Interview 29). Yet lessons can also be derived from unsuccessful cases and arguments too – climate litigators have, for instance, learned about the best way of demonstrating justiciability from lawsuits where this proved to be a stumbling block (Interview 134).

Moreover, even if they are unsuccessful in court, climate lawsuits can nonetheless serve as a source of inspiration and knowledge. Climate lawyers and activists have drawn lessons from other climate lawsuits about the best ways of generating media coverage and galvanizing public opinion (Interviews 25 & 131). Despite underwhelming results in the legal system, the Juliana case has exerted global influence, in part because of its success in attracting media and public attention (Interviews 119, 131 & 34), its resonance for a climate justice movement in which children and young people have played increasingly important roles and its commitment to an ambitious conception of climate justice.

The cumulative effects of practices on the diffusion of RBCL