[T]he law is what the lawyers are. And the law and the lawyers are what the law schools make them. Footnote 1

United States Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter.

It took a very long time for law schools in the United States to become as liberal as they are right now. People just manned the trenches for years and worked hard because they were dedicated to a particular perspective…I think that's all we're doing here… ultimately it's one piece of a mosaic that is in God's hands to finish.

Professor Steven Mikochick, Ave Maria School of LawFootnote 2.

Reorienting the law is not as simple or as formulaic as American New Dealer and late-United States Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter suggests. That being said, in the United States, law schools, legal education, and legal training are widely recognized as an important constitutive “piece” of the greater “mosaic” of American law and legal culture. This is, in part, a result of the widely acknowledged supporting role law schools and legal education have played in a series of high-profile revolutionary legal movements in the United States over the last century. From the New Deal Revolution in the 1930s and 40s (Reference IronsIrons 1993; Reference KalmanKalman 1996; Reference TelesTeles 2008) to the “Rights Revolution” of the mid-twentieth century (Reference EppEpp 1998; Reference JohnsonJohnson 2010; Reference KlugerKluger 2004; Reference TushnetTushnet 1987) to the conservative counterrevolution currently underway on the Supreme Court (Reference Hollis-BruskyHollis-Brusky 2011, Reference Hollis-Brusky2013, Reference Hollis-Brusky2015; Reference SouthworthSouthworth 2008; Reference TelesTeles 2008), a robust body of scholarship has documented how these changes have been, in part, an outgrowth of changes in law schools, legal training, and education. Moreover, recent high-profile investments in higher education by conservative patrons and donors such as the Koch Brothers, the Olin Foundation, and the Scaife Foundation to establish conservative “beach heads” in the legal academy for conservatives who reject the liberal legal orthodoxy (Reference MayerMayer 2016; Reference MillerMiller 2006; Reference TelesTeles 2008) demonstrate the widely held belief that American law schools are a critical lynchpin in the battle for control over the law.

As we explain in this article, the “allure” (Reference Sarat and ScheingoldSarat and Scheingold 2006; Reference SilversteinSilverstein 2009) of law schools as potentially transformative institutions in the United States prompted a small group of movement patrons of the New Christian Right—a radical Christian political movement that burst onto the national electoral scene in 1980 and who believe, among other things, that America is “God's new chosen nation” (Wilcox and Robinson 2011: 24)—to invest heavily in legal education and training in the 1990s and early 2000s. But unlike the aforementioned legal movements, this new one—the U.S. Christian conservative legal movement (CCLM)—seeks to promote and reinforce a vision of law rooted in Christianity and biblical principles; a vision of law that at minimum challenges, and at times directly rejects, the widely-shared premises of “secular legalism” that both legal liberals and mainstream legal conservatives in American law and most of the Western world have embraced since the nineteenth century.Footnote 3

The term “secular legalism” is often deployed in contrast to the “natural law” tradition that understands law as “a rule of reason, promulgated by God in man's nature, whereby man can discern how he should act” (Reference RiceRice 1999: 51). The natural law, its adherents insist, is objective, grounded in biblical truths and principles, and knowable by man through reason (see, e.g., Reference BrauchBrauch 1999: 69–119; Reference SchuttSchutt 2007: 22–38). It is this latter tradition of the “natural law,” as rooted in and connected to Christian foundations and biblical principles, that the American New Christian Right in part seeks to institutionalize as the “missing foundation” in law and legal education (Reference SchuttSchutt 2007: 24). As former Regent Law Professor Michael Schutt wrote in his 2007 treatise, Redeeming Law: Christian Calling and the Legal Profession, “when it comes to current beliefs about the nature of law, the enlightened have come to realize that God is really dead and we are therefore on our own. This is the American legal academy” (Reference SchuttSchutt 2007: 24). The question is, then, how can a group of self-segregated legal and cultural outsiders, (Reference Den Dulk, Sarat and ScheingoldDen Dulk 2006: 198) hostile to the shared precepts of Western law and secular legalism, leverage the very institutions that have promoted and built this consensus to effectively support and serve their movement?

As we explain, because of the “radical” and “transformative” (Reference Scheingold and SaratScheingold and Sarat 2004: 101–03) nature of the New Christian Right's project and because of its history with building separate cultural and educational institutions (see, e.g., Reference Den Dulk, Sarat and ScheingoldDen Dulk 2006; Reference WilliamsWilliams 2010) these early patrons decided not to invest in existing law schools—an approach we refer to as infiltration throughout this article. Instead, as we show, these patrons largely pursued a parallel alternative approach to legal education by building new, separate law schools dedicated to promoting a “Christian Worldview” within the law. Given that, in this study, we examine three law schools founded within a decade and a half of one another by high-profile New Christian Right patrons; each of which is openly and intensely committed to promoting this radical, alternative understanding of law—Regent Law School, Liberty Law School, and Ave Maria School of Law.

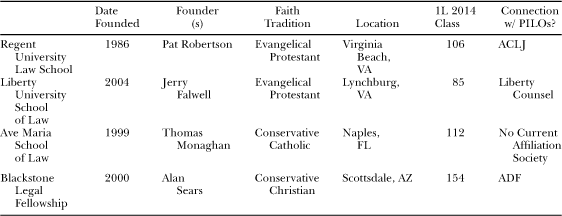

Additionally, we examine the Blackstone Legal Fellowship—a legal training program attached to Alliance Defending Freedom, the leading public interest law firm for what we identify as the Christian conservative legal movement. Blackstone is a competitive summer program that accepts students from law schools across the country, brings them to Scottsdale, AZ for a three-week, intense boot camp in the Christian foundations of the law, and then plugs them into internships and networking opportunities with like-minded legal professionals. As such, Blackstone represents a third approach to institution-building within our study: the supplemental approach.

In this study, we are primarily interested in how each of these institutions seeks to realize its radical mission of challenging secular legalism. We are also interested in how each institution is organizing itself to consciously produce the kinds of transformative capital (human, intellectual, social, cultural) that would serve the interests of the CCLM. Importantly, in this article we do not evaluate the actual quantitative or qualitative production of that capital for each institution—such an evaluation is the subject of our longer, in-progress book project. Instead, we focus our study on the following questions: How does each institution articulate its mission? How do they attempt to realize that mission? What are the constraints, internal and external, to that mission being realized? What do these findings begin to tell us about the parallel alternative and supplemental approaches to legal education and institution-building and, more broadly, about the “allure” of law schools as sites of investment for movement patrons?

To answer these questions, we mobilize data gathered from 42 semi-structured interviews and from participant observation at each of the four institutions. We also rely on interpretive data analysis of publicly available materials from each institution's website, marketing and other ethnographic artifacts collected at each site, and reports from the American Bar Association and US News and World Report. Footnote 4 For more on our data collection and methodology, see Appendix A.

We begin with an overview of scholarship on the value of law schools and legal education for movements looking to reshape or reform the law. Synthesizing this scholarship, we suggest three strategies movements can use to capitalize on law schools as movement institutions—infiltration, supplemental, and parallel alternative. We then situate the initial strategic decisions of patrons within the New Christian Right to reject the infiltration model in favor of the parallel alternative and later supplemental model, introduce the institutions as case studies of this broader attempt to transform law through the institutionalization of a competing vision of the foundations of law as Christian rather than secular, and present our data on how they are attempting to realize this mission and what the constraints and potentials of these approaches are for catalyzing the radical change this movements seeks. We conclude by drawing out some implications for the literature on the role of law schools in aiding movements in their transformative goals. Finally, while this is a study of an American movement and related legal training, as the institutions each make clear via concrete programs and efforts, their aspirations are not limited to their home country. America, for the New Christian Right, might be conceived of as “God's new chosen nation,” but as with the more general evangelical impulse, the larger driving mission is the establishment of the kingdom of God on earth as a whole.

Strategies for Leveraging Law Schools and Legal Training for Movement Goals: Infiltration, Supplemental, and Parallel Alternative

Why does American legal education hold such “allure” (Reference Sarat and ScheingoldSarat and Scheingold 2006; Reference SilversteinSilverstein 2009) for movement patrons seeking to transform the law? As “gatekeepers to the profession” (Reference TelesTeles 2008: 13), law schools are seen as key sites in the battle over who controls law, legal culture and legal meaning more broadly. As Steven Teles writes in his sweeping 2008 study of the libertarian and secular conservative infiltration of law schools:

These institutions not only produce legal ideas, but are also the dominant force in training successive generations of lawyers, influencing their notions of the proper function of law in society, of which legal claims are “off the wall.” And of how a career in law might be pursued (12–13).

Indeed, institutions of legal education are well-positioned to provide various forms of essential capital for movements interested in transforming law. They attract, socialize, and credential lawyers (human capital) (Reference TelesTeles 2008); establish or provide inroads to networks for group advancement (social capital) (Reference SouthworthSouthworth 2008); and create, spread, and legitimate ideas within the legal, political, and wider publics (intellectual and cultural capital) (Reference BalkinBalkin 2001; Reference Hollis-BruskyHollis-Brusky 2013, Reference Hollis-Brusky2015; Reference TelesTeles 2008). As such, one can begin to understand the “allure” of law schools and legal education for movement patrons looking to transform the law more broadly.

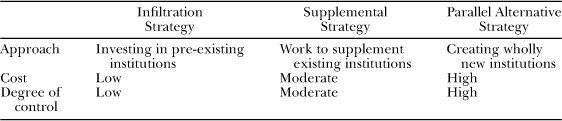

There are three general strategies available to movement patrons interested in investing in legal education and training, each of which carries distinct costs and benefits (see Table 1). While listed as distinct from one another, those looking to develop such “support structures” (Reference EppEpp 1998) for their movement goals can invest in one, two, or all three strategies if interested and able. We define each approach below and then discuss in more detail how these strategies bear out and interrelate in our case studies.

Table 1. Strategies for Movement Patrons Interested in Influencing Legal Education

The infiltration strategy involves investing in or attempting to infiltrate pre-existing institutions. Infiltration is a relatively lower cost approach to developing support structures, since the startup costs associated with building something from scratch are not present. That said, it also involves a lower degree of control for those seeking to create support structures. The infiltration strategy might involve, for example, endowing a chair or two in an academic department, providing money for a resident scholar or clinic, or working to place sympathetic academics or administrators on the faculty of institutions in order to change the political or intellectual character of that institution. Infiltrating and influencing hiring practices is also an option, but it is one that involves long-term calculations and an uncertain pay-off. In terms of the existing literature, Teles's discussion of the Olin Foundation's approach to spreading Law and Economics represents the infiltration approach (Reference TelesTeles 2008: 181–207), as does the Koch brothers investment in various colleges and universities (Reference LevinthalLevinthal 2015). For reasons explained in the next section, the infiltration strategy represents the road not taken for the CCLM.

The supplemental strategy is a true middling strategy in this typology—it involves more resources and a bigger investment than infiltration, but significantly less than the parallel alternative strategy. The supplemental strategy affords those creating institutions more control than the infiltration approach, but because this approach involves working alongside existing institutions, one lacks full control. The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies offers one way of thinking about the supplemental strategy.

The Federalist Society was founded in 1982 by a small group of conservative and libertarian-identifying law students at Yale Law School and the University of Chicago Law School to provide counter-programming and a counter-network to what its founders describe as the “liberal orthodoxy” dominant at their elite law schools (Reference Hollis-BruskyHollis-Brusky 2015; Reference SouthworthSouthworth 2008; Reference TelesTeles 2008). Since then, it has grown into a network of more than 40,000 conservative and libertarian law students, lawyers, judges, and legal academics dedicated to reforming the law and to bringing conservative and libertarian legal ideas and agendas into the mainstream of law and legal education. We categorize the Federalist Society as part of a supplemental strategy because it provides a supplemental education, training, and network for right-of-center law students and academics through its Student DivisionFootnote 5 and its Faculty DivisionFootnote 6 chapters situated at nearly every accredited law school (Reference Hollis-BruskyHollis-Brusky 2015). In this way, the Federalist Society provides a counter-education to the mainstream “liberal orthodoxy” of law school faculty and curricula while capitalizing on the credentials and established structures of mainstream law schools. Alliance Defending Freedom's Blackstone Legal Fellowship—a summer training program for Christian law students—represents the supplemental strategy in our fieldwork.

The parallel alternative strategy—creating brand new institutions—comes with the highest price of the three options, but it also affords the greatest amount of control over the shape, content, and culture of the institution. That, however, does not mean that these institutions are wholly unconstrained. Law schools, for example, still have to operate within the norms of the American Bar Association if they want to be accredited, and accreditation is presumably a significant factor in attracting respected faculty, quality students, and many patrons. Accreditation is also undoubtedly a significant factor in a school's ability to be taken seriously within the greater legal community.

Within the existing scholarship on contemporary law schools, Teles's detailing of Henry Manne's development of George Mason University School of Law as a law school infused with the law and economics approach to law arguably fits this strategy.Footnote 7 Manne focused his efforts to integrate law and economics into mainstream law school curricula on the parallel alternative approach after becoming frustrated with his efforts at infiltrating other mainstream law school curricula (Teles 207–19). Deeper roots to the parallel alternative strategy are also seen in Howard University School of Law's multiple connections to the Civil Rights Movement (Reference JohnsonJohnson 2010; Reference KlugerKluger 2004; Reference TushnetTushnet 1987). While created in response to segregation and the need for African Americans to be able to access the law, Howard Law came to see itself in the 1930s as explicitly working to get the “accepted devices of the law adapted to peculiar Negro problems” (Reference TushnetTushnet 1987: 31). As such, Howard Law came to possess an explicit orientation toward social change and thus functioned as a parallel alternative institution fueling legal change. In terms of our research, the parallel alternative strategy is represented in Regent University, Liberty University, and Ave Maria Schools of Law—all of which were created with explicitly religious missions in mind by leading activists within the New Christian Right.

Before moving to our case studies, we should also note that these strategies can reinforce one another. For example, the supplemental strategy can help train and credential lawyers and place them in a position to better-infiltrate existing institutions (infiltration strategy). The Federalist Society has effectively played this role within the secular conservative legal movement; that is, helping to socialize and train law students from elite law schools and working to place them on law faculties through the Olin Fellows program and/or through its more informal academic networks (Reference Hollis-BruskyHollis-Brusky 2015; Reference TelesTeles 2008).

On the other hand, these strategies can also work against one another. The decision to invest in parallel alternative institutions, for example, will have the consequence of redirecting resources and personnel from existing institutions. In other words, if we assume that human capital is a limited resource, then the decision to deploy that capital in service of building a parallel alternative institution necessarily works against and weakens the infiltration strategy. This modeling of strategies and options for patrons interested in investing in legal education for transformative purposes is thus meant to organize, but still account for complexity.

A Brief History of the CCLM and Its Decision to Reject the Infiltration Strategy

Christian conservatives faced multiple barriers on the road to law school and legal practice. Much like fundamentalists’ and early evangelicals’ aversions to public engagement and politics, conservative Christians had a long-standing mistrust of lawyers, and there was an established belief that it was difficult, if not impossible, to be both a good lawyer and a good Christian (Reference SouthworthSouthworth 2008; Reference Wilson and Hollis-BruskyWilson and Hollis-Brusky 2014). Exacerbating this was a persistent, parallel mistrust of the nation's colleges and universities (Reference RingenbergRingenberg 2006).

Leaders within the CCLM and the greater Christian Right have taken at least two identifiable steps to ameliorate these access problems. One was to address some of the cultural barriers to Christian conservatives entering the legal field by reframing the practice of law. The other was to create distinctly Christian conservative institutions of legal education and training.

Starting with the former, one can see a similarity to moves made in the 1970s to allow Christian conservatives to enter politics. In that earlier period, Francis Schaeffer, a Swiss-based American Evangelical theologian, helped bring Christian conservatives into the public square. Schaeffer's books, lecture tours, and films helped to give theological reasons—even a duty—for orthodox Christians to engage in politics (Reference HankinsHankins 2008). Decades later, institutions within the CCLM did the same for the practice of law, reframing law from a profession to a religious calling (Reference Wilson and Hollis-BruskyWilson and Hollis-Brusky 2014). Seen as a religious calling, legal practice, and by extension, law school were able to become more visible and realistic options for Christian conservatives.

Reframing the practice of law, however, is not enough on its own to rebuild and reorient the foundations of law. The reframing of legal practice may provide Christian conservatives with a new means of understanding lawyers and the possibilities of their work, but it was hard to see an avenue to becoming such a Christian attorney if law school still seemed unwelcoming and possibly posed a threat to their Christian identity. Existing law schools presented three years of being an outsider and/or keeping one's Christian identity private, something many of our interviewees spoke about. At worst, they stood as a means of leading the devout away from what they could now see as their calling. As Herb Titus, the founding Dean of Regent Law School, explained of his decision to leave a tenured position at the University of Oregon:

…there was a conflict between what I believed as a Christian and what I could teach in the class…When I tried to get [the biblical perspective] into the classroom I had people screaming at me. I had people say, “You can't bring the Bible into a law school classroom!” So I began to see that there was an irreconcilable conflict between what I believed was true and what I could teach.Footnote 8

Titus's sentiments are characteristic of vignettes we heard from other interviewees. Openly Christian, conservative faculty at these schools that had attended or previously taught at mainstream, secular or even Christian law schools described having felt shackled by a lack of academic freedom and expression. Some were openly discouraged from expressing their Christian views on the law and many described feeling generally isolated from their colleagues. These feelings even extended to prominent religious law schools—such as Notre Dame—that were frequently described as having become too secular and liberal.

Because of the perceived hostility of existing law schools to both their identity and their beliefs about the Christian and biblical foundations of law and because of the aforementioned history of the Christian Right building parallel institutions, the Christian Right's leaders opted to primarily pursue parallel alternative strategies to realize their ambitious, transformative goals, while also dedicating some resources to supplemental strategies. Representing the evangelical and fundamentalist Protestant traditions entries into legal training, Marion “Pat” Robertson established Regent University Law School in 1986, and Jerry Falwell created Liberty University School of Law in 2004. Between these two, Thomas Monaghan founded his conservative orthodox Catholic law school, Ave Maria School of Law, in 1999. Ave Maria was followed one year later by the Alliance Defending Freedom's Blackstone Legal Fellowship—a summer training and internship program for Christian conservative law students (see Table 2).

Table 2. CCLM Institutions: Facts, Founders, and Faith Traditions

What they avoided was investing in infiltration strategies targeting existing law schools. This was not, however, for a lack of options. Established law schools such as Baylor, Pepperdine, and Notre Dame all offered legitimate, and presumably highly attractive potential options for Christian conservative infiltration. As conservative, “critical mass” religious institutions with established histories, networks, faculty, and traditions, Baylor, Pepperdine, and Notre Dame stood to provide the CCLM with rich access to the capital that they needed.Footnote 9 The movement thus could have piggybacked on these or other schools’ reputations, networks, students, faculty, and religious commitments, all of which could immediately benefit the emergent CCLM, instead of making the larger moves to found multiple new law schools.

The decisions to create brand new institutions over investing in existing ones reflects a larger pattern repeated over the duration of the Christian Right's existence. As seen in the institutional histories of earlier Christian conservative educational institutions, “[m]ost of the schools were founded…by unusually aggressive and dynamic men who then continued to lead the schools they founded. Their followers often deferred to them more completely than they would to the leaders of a college that existed for a century or longer” (Reference RingenbergRingenberg 2006: 178). Thus, just as with these earlier institutions, big personalities with defined views of the world's problems and their solutions form the base for the CCLM movement and its support structures.Footnote 10 Institutional creation is therefore seen as not just being about some idea of efficiency in adding to existing institutions, or even advancing a collective vision for the world. It is also about maximizing control at every level in bringing one's specific vision to life.

In the sections that follow, we present our initial findings vis-à-vis each institution's founding mission and resources, how each attempts to realize that mission, and the constraints and contextual realities pushing back against these institutions realizing their transformative and radical goals of rebuilding the foundations of American law.

Parallel Alternative Strategy: Building New Law Schools

Mission Possible? Radical Transformative Visions

Each of these New Christian Right law schools share a “transformative” (Reference Sarat and ScheingoldSarat and Scheingold 2006) vision of law and legal education. Though our interview subjects were insistent that this vision is more accurately “restorative.” That is, the project of each of these schools is, in their view, to reject “secular humanism” and “secular legalism” and to return law to its Christian roots or foundations. A recent version of the Dean's message on Regent Law's web site illustrates how the school advertises itself as distinct and as distinctly Christian: “What makes Regent unique among law schools approved by the American Bar Association is that we thoroughly integrate a Christian perspective in the classroom. We are committed to the proposition that there are truths—eternal principles of justice—about the way we should practice law and about the law itself.” The school's former motto is more succinct, “Law is more than a profession. It's a calling.” These formal statements show that Regent views itself as catering to a specific population, and producing a type of lawyer that previously was not intentionally created.

The transformative mission of these institutions, and the perceived urgent need for them by their founding patrons, is perhaps most succinctly stated by Jerry Falwell, Sr. with regards to why he founded Liberty's Law School:

The 10 Commandments cannot be posted in public places. Children cannot say grace over their meals in public schools. No prayers at football games and on the list goes, virtually driving God from the public square. And then, of course, Roe vs. Wade in the middle of all that…Now, the redefining of the family or the attempt to. So, all of this reinforced our belief that we needed to produce a generation of Christian attorneys who could, in fact, infiltrate the legal profession with a strong commitment to the Judeo-Christian ethic (Reference AndersonAnderson 2007).

Indeed, when one visits the Liberty campus, the final painting in a series of murals lining the school's main corridor depicts Falwell, Sr. praying and receiving divine inspiration to found the law school, as well as an image of the first graduating class descending on the U.S. Supreme Court. The painting preceding this—with the Court encircled by ominous clouds, protestors, an overturned police car, and texts by Darwin, Kinsey, and others—not-so-subtly presents the perceived need for his school and its graduates. A leading administrator at Ave Maria School of Law (AMSL) was similarly unguarded about sharing the broad ambitious and movement-related goals of his law school, “[o]ur mission is to develop, instill, cultivate, produce lawyers that will go out into society and…bring to their practice natural law and the teachings of the Catholic Church.”Footnote 11

These institutions aim to realize their shared missions in similar ways. The primary shared instrument is to require classes in the curriculum that incorporate biblical themes; courses that make explicit the “Christian foundations” of law. At Regent, for example, all students take a course in the first year entitled “Christian Foundations of the Law.” Liberty requires two “Foundations of Law” courses which promote a “Christian Worldview” of the law and AMSL requires their students to take three core “mission” courses: “Moral Foundations of Law,” “Jurisprudence,” and “Law, Ethics and Public Policy.”

In addition to these required “mission” courses, faculty, students, and alumni spoke frequently about how biblical and Christian teachings are woven into non-mission classes on Property, Family Law, International Law, and many others. For example, in Liberty Law Professor Jeffrey Tuomala's “Con Law I” course, the “Holy Bible” is “Required” reading alongside more standard Constitutional Law casebooks.Footnote 12 At Ave Maria, we heard repeatedly that “faculty have some obligation to try when relevant to integrate the natural law perspective into their teaching.”Footnote 13 Corroborating this, the classes that we sat in on at all three institutions opened with class prayers, and it was common for the faculty to explicitly return to religious or biblical themes as the law was discussed. As one Liberty law student conveyed in an interview, the conversation is “very integrated… a lot of things that we talk around law, there are biblical examples of… we can have these conversations of how do we integrate our faith with this law.”Footnote 14 Similarly, a Regent administrator and faculty member noted in our conversation about their curriculum, “You are… free to disagree with biblical positions, but you have your bible open and your code book open and your case book open.”Footnote 15

Regent and Liberty also offer proximity to, and collaboration with, major CCLM Public Interest Law Organizations (PILOs) as a means of realizing their radical and transformative mission. Dean Titus cited Regent's close relationship with Pat Robertson's American Center for Law & Justice (ACLJ)—the PILO maintains an office in the law school's building—as an important recruiting and legitimating tool for the law school.Footnote 16 Following suit, Liberty's first online “News and Events” article, posted one year before it welcomed its first class, announced that it had “entered into a partnership” to create an on-campus training center with the Liberty Counsel (LC)—a PILO founded in 1989. It went on to note that “Uniting the academic resources of Liberty University School of Law with the real-life opportunities offered by Liberty Counsel in religious liberty litigation and pro-family policy will…result in a powerful force dedicated to the mission of renewing the American legal culture.”Footnote 17 Liberty Counsel's founder, Matthew Staver, also eventually became the Dean of Liberty Law from 2006 to 2014.

Collectively, this evidence illustrates how the New Christian Right patrons ideally envision these law schools serving to institutionalize a radical and transformative set of ideas about the foundations of law. True-believing faculty are recruited to train like-minded students who aspire to change the legal and political worlds. Students are then connected to networks, interest groups, and public interest law organizations where they will subsequently bring cases to court, and eventually staff those courts. While few students or graduates will make it into policymaking or judicial positions, this is a story these institutions tell about themselves. It motivates their actions, their investments, and their approach to legal education and training. For example, when asked what he thought the impact of AMSL would be, then-Associate Dean of Students and faculty member Ted Afield responded in the following way:

Some of our early alums are just starting into that mid- or early mid-career stage, but once we have more of those who become judges, who become legislators, who become leaders in law firms and organizations that lead throughout the country. My hope is that you'll start to see… a more transformative influence on the legal profession as a whole.Footnote 18

As noted earlier, though, this presents far too linear and instrumental a vision of support structure creation, maintenance, and production. One must also recognize that this hoped-for progression is embedded within wider contexts that affect its realization, and that while these connections between legal education and litigation can be productive and generative for movements, they can also be in tension with one another. What's more, this idealized vision fails to recognize the realities of how institutions meant to serve the same movement can also be in tension with each other. These connections thus stand to not only facilitate, but also to complicate and potentially impede the production, distribution, and value of movement capital.

Control versus Constraints in Realizing the Mission

While creating one's own law school allows for maximal control in designing a support structure institution, it is still subject to significant constraints that may not be initially realized. This section thus illustrates: (1) the significance of external, contextual factors; (2) the importance of a law school's relationships with patrons in order to effectively balance responding to external constraints, while preserving adherence to their stated mission; and (3) the need to recognize the limits of essential, nonfinancial resources consumed by support structures as a factor that can affect their efficacy.

According to Regent's founding Dean Herb Titus, as a lawyer himself, “Pat [Robertson] had always wanted to start a law school.”Footnote 19 When fellow Christian televangelist Oral Roberts, who had grown weary and cash-strapped from his own extended battle for law school accreditation with the American Bar Association, called Robertson and offered him the law library, Robertson jumped at the chance. While the accreditation fight fatally exhausted the school's resources and ended any previous efforts by others, ORU had overcome intense opposition from the ABA which, at that time, refused to accredit any law school that had “religion” as a criterion for faculty hiring and student admissions. ORU successfully got the ABA to change its rule regarding religious criteria in hiring decisions which, in turn, “changed the whole course of the effort” in favor of other potential Christian law schools.Footnote 20

This clearly eased the way for Regent, AMSL, and Liberty. That said, in 2016 Ave Maria came under ABA observation and was subject to required remedial action, showing that maintaining accreditation can remain a significant factor for law schools even after it has been awarded.Footnote 21 As will be seen, though, AMSL's more recent difficulties stem from different problems both directly and indirectly related to their mission.

While undergoing its ABA accreditation, a high-profile clash between Regent's Dean Titus and its primary patron Pat Robertson illustrates some of the related ongoing difficulties with maintaining strong control of the mission while trying to satisfy both an external body of accreditors who will determine whether the institution can exist in any meaningful and effective way, and a patron who recognizes the pragmatic effects of rejecting the outside world. It also illustrates the interconnected, but conflicting, nature of the factors that are necessary for both realizing an institution's specific mission and increasing institutional capital in the wider world.

Titus believed that in order to fully execute the mission of an integrated Christian legal education, Regent needed to maintain strict screening procedures for students and faculty. This meant rigorously enforcing the religious standard for students and faculty and, relatedly, refusing federal financial aid. In his words, financial aid amounted to an “economic trap” meant to undermine religious standards. Such strict control over the mission, however, comes with costs and thus raises significant questions for patrons and leaders.

A tight filter for screening students and faculty preserves institutional purity, but it is hard to foresee many students who would be willing to attend a school that did not offer financial aid, or that lacked accreditation, let alone employers and public officials who would take the school's graduates seriously. While Titus said that schools before ORU's fight with the ABA “either failed or they changed their mission,” it is clear that practical considerations still force conflict, sacrifice, and compromise within those schools that seek to survive in a competitive legal marketplace.Footnote 22

In this particular case, the conflict led to forcing Titus, and his call for strict purity, out in the name of meeting these mainstream requirements that bring financial security and popularly recognized legitimacy. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of the institution being able to send valued capital to the movement. The question remains, though, as to whether meeting these mainstream requirements detrimentally dilutes the mission. That is, while the ability to put increased amounts of more popularly valued capital into circulation may increase, its specific substantive value for the CCLM may decrease.

Even with a slight reduction in the absolute control Titus sought over student and faculty population, interviewed faculty and administrators were adamant that Regent Law still manages to attract a significant portion of devout law faculty and students who come for the school's mission. In terms of the former, Regent's secure economic base via Robertson's financial dedication to the program and its connection to the larger University, coupled with being the only ABA accredited new Christian law school for many years, gave it an advantage. Until the subsequent schools were established and earned accreditation, Regent was the only relatively safe, and thus attractive destination for disaffected Christian law faculty and accomplished Christian lawyers interested in transitioning to academia at a mission-driven institution.

Given that this faculty pool is limited, Regent's “first in” positioning enabled it to draw better-credentialed faculty than its later competitors, increasing its cultural capital. This is particularly true regarding evangelical Protestant faculty, and it can be seen as part of the problem with creating such schools beyond Regent and Liberty. Ave Maria, as a conservative Catholic institution, is less likely to be hampered by the existence of Regent and Liberty, but it is impeded by the multitude of existing Catholic law schools, as well as more newly created ones such as University of St. Thomas Law School established in 1999. Given this pool of existing Catholic institutions it has to differentiate itself via its pervasive conservatism, narrowing the pool of potential faculty even more.

The above introduces the importance of recognizing the scarcity of essential nonfinancial resources that like-minded institutions have to compete for in order to thrive. As evidence, 43 percent of Regent's lifetime faculty have come from top-20 schools, as have 42 percent of Ave Maria's. Liberty, however, trails far behind with only 10 percent of its faculty coming from such elite institutions. If you extend the count to include top-50 schools, the pattern remains the same—Regent at 59 percent, Ave Maria at 53 percent, and Liberty only improved to 20 percent of its lifetime faculty. For Liberty, their top-50 list percentage is lower than the 25 percent of faculty that come from schools that fail to earn a ranking in the US News lists.Footnote 23 What's more, of the Liberty faculty who hold JDs from unranked schools, half earned their degrees from either Regent or Liberty.

Regent and Liberty illustrate the importance of first-in positioning; the consequences of the timing of when the respective schools entered the academic marketplace, and how this timing affected their attractiveness and abilities to draw needed human resources with more broadly recognized signs of cultural capital. Regent's more widely recognized faculty pedigree can thus serve as a selling point for devout, well-qualified potential students. It is also far better positioned to increase the institution's credibility in the wider legal and political world.Footnote 24

What could otherwise be thought of as a similar selling point could also be viewed as a liability. Some interviewees cited Liberty's close affiliation with the Liberty Counsel as part of the problem with faculty composition, adherence to the school's mission, and more broadly perceived legitimacy. Instead of hiring with an eye toward traditional academic markers, some faulted Dean Staver as steering too far in the direction of culture warriors and culture war casualties in hiring and beyond: “[there was] such a focus on Liberty Counsel and that sort of thing that the law school was neglected.”Footnote 25 In the words of former Regent Dean Titus, this arrangement crossed the line and ended up with “the tail wagging the dog…it changed the mission of the law school.”Footnote 26

Moving from the scarcity of the “right” faculty to the scarcity of the “right” students, it is important to recall that students are both a means and an end for law schools. As such, they are simultaneously a resource and a product for these support structures. In order to meet their specific missions, they need a critical mass of students who are devout and by their mere presence, create a coherent and pervasive culture within the school. In order to elevate the institutions’ more broadly recognized capital, law schools also need these students to be high academic achievers as they enter and leave the institution. The former elevates the school's admissions criteria, the latter translates to Bar passage and job placement rates, all of which culminates in increasing the school's reputation. The pool of high-achieving devout students motivated by these schools’ specific missions is, again, limited. Since so much rides on attracting and maintaining the “right” students, the competition for them can be seen in existential terms.

We found anxiety around student body composition at all of our schools, and these worries were bound up with, and molded by, their relationships with their patron bases. In sum, the less secure the institution's financial base, the more they were concerned with both academic and religious credentials. The more secure their financial resources, the more they emphasized academic qualifications over religiosity as they were more able to effectively recruit from the limited pool of students that possessed both desired qualities.

Interviews at Regent and Liberty underscored the dedication of Robertson and Falwell Sr. and Jr. to their respective schools. Both schools are also connected to the larger Universities bearing the same names, providing some additional degree of financial security. For example, Falwell, Jr., who has taken over for his late father, has noted that the law school was his father's dream and that the university would float it for as long as it needed to become financially self-sufficient.Footnote 27

AMSL, however, is independent from the larger Ave Maria University. Faculty and administrators note that Monaghan is fairly visible on campus, but some fault him for providing the initial seed money and then leaving the school to “sink or swim,” as well as causing unnecessary harm to the institution. As described by one interviewee, “in the early years he gave us a huge amount of money and it was a declining amount. We had to be able to survive on our own and not be dependent on annual subsidies. That's been a big thing.”Footnote 28 Exacerbating the resource question, Monaghan came under fire for his controversial decision in 2009 to move the law school from Michigan to Florida. The move angered and alienated many faculty and alumni, damaging alumni involvement and support. It also resulted in a fairly extensive reconstitution of faculty.Footnote 29 In her interview, Associate Dean of Student Affairs Kaye Castro added that if the law school was “really in trouble” she could not say whether or not Monaghan would help out financially.Footnote 30

These different financial orientations produced distinct concerns about the ability to attract highly qualified students and subsequently produce valuable human capital in the form of graduates. While these concerns will exist for any newly created schools, their importance is all the more visible given the legal market's ongoing contraction. In the words of a prominent Regent administrator, this exogenous shock forced many law schools to make tough decisions about quality control versus revenue:

[E]verybody's been hit with the market contraction… [So] do you uphold standards of quality or do you just say we're going to have two hundred people in the door no matter what and if you can breathe and walk at the same time, we'll let you in. Some schools have gone in that [open admissions] direction.Footnote 31

Because these schools must fold religiosity into their calculations when responding to this market, shrinking the pool of desired students, the decision's difficulty and stakes are amplified. Examined against the background of institutional resources, a range of traditional markers and interview data provide a means to considering how well these support structures are functioning, and why. Regent, combining its first-in advantages with its financial resources, appears to be in the best position, while AMSL and Liberty trail behind, changing position depending on the exact marker used to evaluate them.

Considering entering student composition as a means to institutional ends, there is a differentiation between the schools that correlates with financial security and access to other nonfinancial resources. According to data collected in the US News & World Report (2015) comparing the 25th–75th percentiles for undergraduate GPA and LSAT scores, Regent has the strongest students (3.01–3.65, 150–157), Liberty is second (2.83–3.54, 148–155), and AMSL is third (2.76–3.41, 141–148). The school order shifts slightly with acceptance rates—50 percent at Liberty, 54 percent at Regent, and AMSL is the outlier with 71 percent. Examined as a whole, Regent and Liberty are comparable to regional law schools such as Quinnipiac University (CT), Campbell University (NC), and University of Wyoming, while AMSL fares worse. Tracking with other changes within Ave Maria, AMSL used to compare favorably to Liberty before it moved to Florida, before the legal market's prolonged slump, and during the time when their financial sources were more secure.

The importance of financial security is underscored when one looks at how Regent and Liberty have been able to weather the contraction in the legal market. As was noted several times in our interviews, Liberty offers the most attractive financial aid and scholarship packages of any school in Virginia, a statement that has some external support.Footnote 32 This can help them compete with Regent for academically solid devout students. Regent also aimed for top academic talent by creating its Honors program, which welcomed its first class in 2011. As a Regent administrator notes, the “honors program was set up….to say to someone who would want to go to a Christian law school, but has really high credentials, ‘you shouldn't have to feel like you're making some sacrifice to come here.’”Footnote 33

The schools’ responses have not, however, made them, or a subset within them, into top-ten or top-20 institutions—Regent's honors students, for example, have mean GPA and LSAT scores that place them among the ranks of schools such as Baylor (TX), Arizona State, and Ohio State.Footnote 34 That said, they do provide a means to some degree of quality control in an increasingly challenging market. Importantly, this is something that AMSL was not able to do given its unstable base and, arguably, an even more competitive market given the number of existing and better established Catholic law schools—even if they are not considered “truly Catholic” by Ave Maria's standards.

As has been noted, an essential means of realizing a school's mission comes via having a critical mass of students dedicated to that mission. While this was of great concern to Regent and Liberty in their early days, it did not seem as such any more. Interviewees at these institutions felt that they were among likeminded Christians. The same cannot be said for Ave Maria.

One of the more interesting findings at AMSL was the fairly prevalent and casual deployment of the terms “mission student” and “non-mission student.” Mission-students were identified as those students (mostly from out-of-state) that were drawn to the school by the mission, that could have gone elsewhere and perhaps to higher ranked law schools, and those who were involved in the leadership of pro-life club Lex Vitae or the student chapter of the Thomas More Society. Non-mission students were described as being almost all local, they might be Catholic, but they were not considered devout, and/or they chose AMSL because it was the best school they could get into or it allowed them to remain in the area. Everyone had different estimates about the percentage of mission students at AMSL—anywhere from 5 to 15 percent—but the consensus seemed to be that the school was attracting fewer since its move from Ann Arbor and its ensuing financial difficulties. There was also consensus that it had produced significant cleavages within the student body, hampering the realization of the mission.

Given the mixed quality of students entering these schools, more traditional measures of success—such as bar passage, job placement, and judge/lawyer reputation assessment—have been similarly mixed. Bar passage rates of the three schools studied were lackluster—Liberty at 72 percent, AMSL at 75 percent, and Regent at 81.8 percent. The same, or worse, can be said for their nine-month employment rates, with Liberty at 60 percent, Regent at 59 percent, and AMSL at 47.6 percent. Correspondingly, the US News & World Report 2015 Lawyer/Judge Assessment scores—which are out of 5—were 1.7 for Liberty, 1.8 for Ave Maria, and 1.9 for Regent.Footnote 35

This lack of traction in traditional measures of capital clearly hurts the schools’ abilities to send valued forms of human and related capital into circulation. Liberty has tried to address this by emphasizing, as many other schools have, practical lawyering skills.Footnote 36 Liberty students now take six lawyering skills classes and the school's “Law School Academics” page makes the “practical skills program” its centerpiece.Footnote 37 Both Regent and Liberty also emphasize their moot court teams as examples of their ability to produce good lawyers. For example, Regent's webpage recently touted that their program, “ranked fifth in the nation for Best Moot Court…above schools such as the University of Virginia, Baylor University Law School, Colombia University Law School, and Duke University Law School.”Footnote 38 Similarly, Liberty noted that it was ranked in the nation's top 10.Footnote 39

One can see a long-term strategy here. By emphasizing the practical, they can improve their reputations over time. For the less secure Ave Maria, though, their deficiencies in recognized capital are made far more urgent by their questionable ability to invest in the long-term. As one faculty member put it to us in confidence, “We've got a bar problem. It's affected our recruiting. It's affected our admissions. It's affected everything. It's affected our alumni network… we need to get that straightened out.” This is more than just an annoying distraction from the mission-focus of AMSL. It is, as one faculty member put it, an immediate matter of survival.

The lack of stable and sufficient funding can reasonably be seen to have set a dangerous deteriorating cycle into motion. As funding dropped, the quality of students dropped, as did the number of students invested in the mission. This led to AMSL's problem with bar passage and with mission maintenance. This, in turn, reinforces and accelerates the deteriorating cycle by deterring strong potential future students, faculty, and patrons. Thomas Monaghan, similar to the other patrons studied here, sought to create a law school as part of his mission to realize his conservative religious ideals, and as a means of pulling the wider world in his direction.Footnote 40 Years into the project, instead of molding the world, AMSL appears to be overwhelmed by factors its founders did not appear to foresee in that world. Its history, however, reveals the importance of solid patronage and the varied greater contexts that such institutions will be subject to.

Regent and Liberty's founders may have also been initially myopically focused on the desire to create movement institutions, but they more quickly came to terms with the wider contexts within which those institutions operate—even if the compromises that enabled them to adapt are not wholly uncontroversial and without tradeoffs. The stable base they provide, combined with an apparent understanding of the incremental nature of litigation-driven change, has enabled them to create a more realistic plan to effectively put movement capital into circulation.

The above has focused on both the importance of a dependable patron base as well as the wider contexts—as largely defined by the legal academic world—in which these institutions exist. Another important contextual factor to consider with regards to the efficacy of these institutions as producers of capital is the broader political opportunity structure. While these three schools may be lacking in traditional markers of prestige and capital, variously negatively affecting their value as capital producers, current events have shown that changes in politics can dramatically alter these support structures’ prospects. These schools’ graduates may lack broadly recognized capital, but they have a receptive audience in conservative administrations that need to demonstrate their valuing of the Christian Right to its elites and rank-and-file voters. The following news release by Liberty in 2014 illustrates how friendly state politics can allow such schools to function as effective support structures. In this single example, one can see the fruitful transmission of both human and intellectual capital between different movement institutions, and eventually to judicial decision makers. What's more, Liberty's publicity of this multi-layered success story shows how such attention cycles back down to the law school, allowing it to announce its effectiveness to elites and the public, as well as potential students, faculty, and donors.

Three graduates of Liberty University School of Law have the privilege of serving as law clerks for Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore, who issued a landmark ruling on April 18 that the word “child” in Alabama's chemical-endangerment statute applies both to the born and unborn… Clark, Wishnatsky, and Boyd became the first Liberty alumni to land full-time positions in a state supreme court in 2012 after completing internships with Liberty Counsel. “These grads love the law school and are making a huge impact,” said Mat Staver, dean of Liberty University School of Law. “As the law school ages, we will see more of this as our graduates move up in the ranks.” This is also the first case in which the Liberty University Law Review, published three times a year by Liberty Law students, has been cited in any court opinion. Alabama Justice Tom Parker referred to Wishnatsky's article, “The Supreme Court's Use of the Term 'Potential Life': Verbal Engineering and the Abortion Holocaust,” written when he was still in law school and published in the winter of 2012 after he had completed his internship with Liberty Counsel. ”Footnote 41

The above illustrates the idealized functioning of a law school as a producer of transformative legal and cultural change. The law school produces graduates and scholarship, sends those students first to a movement PILO, and then into the judiciary where they marshal the scholarship to significantly influence a central case's outcome. What's more, Staver's statements clearly illustrate how leaders within the law school and the greater movement hope that this type of success will accelerate, propelling a cycle of legal, and political change the Christian Right has long sought. Again, we do not claim that this is happening or that these connections to litigation are the most important part of the story of the rise of the CCLM. It is, however, a story this movement tells itself; one which animates their investments and structures their choices.

Supplemental Strategy: The Blackstone Legal Fellowship

The supplemental strategy, which we have argued involves a moderate degree of cost and offers a moderate degree of control for patrons, provides supplemental training and networks for law students enrolled in existing non-mission law schools. In this way, it piggy backs off of high-cost investments by law schools and provides a targeted way of training, socializing, and networking existing human capital. But its control over its student pool is more limited, and its ability to marshal all of the capital it targets is precarious.

The three-phase Blackstone summer program represents the supplemental strategy in our model. Established in 2000 by Alan Sears as the law student educational arm of Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), the largest and most well-funded Christian conservative PILO (Reference BennettBennett 2017), the Blackstone Legal Fellowship has grown from 24 interns in 2000 to 158 interns in 2015.Footnote 42 Phase I of Blackstone involves a two-week educational boot camp in the natural law with a rotating set of faculty who lead seminars and devotionals designed to address, “challenges facing Christians in the legal profession.” According to one of its administrators, the readings and topics of these seminars vary according to what is currently of interest to fellows and faculty. Phase II is a six-week internship and Phase III is a one-week end-of-the summer career development seminar designed to help interns “develop a deeper vision of their professional calling.”Footnote 43

The program came to be as a result of, “the negative experience that Alan Sears had when he was in law school, that he was alone, that the other side was not articulated, except to be perhaps ridiculed or caricatured.”Footnote 44 Similar to the law schools’ statements, Sears built the Blackstone Fellowship to create “intellectual balance” in the presentation of law and legal foundations and to make sure that conservative Christian law students across the country knew that they were not alone.Footnote 45 To wit, Blackstone's self-described purpose is, “to cultivate a new generation of leaders throughout the legal culture that is propelled by this vision of the law to foster legal systems that fully protect our God-given rights.”Footnote 46

As the above administrator explained to us in an interview, influencing the law and judicial outcomes needs to start from the bottom up: “Unless you're dealing with the law profession culture, you're not going to influence the Court, you're not going to have the right decisions, so to speak.”Footnote 47 While this echoes what we heard at the law schools, Blackstone's approach to changing legal culture and precedent is distinct in a few important ways that capture the primary virtues and limitations of the supplemental strategy.

Evidence from interviews suggest that Blackstone was explicitly designed to respond to and supplement perceived deficiencies both in mainstream legal education but also in distinctly Christian conservative education:

We weren't opposed to Christian Law Schools, heaven forbid, but … that's just not the only game in town nor should it be…I'm all for distinctively Christian education but we have to think that through when you're talking about a profession…I went to a top-10, top-15 law school because I knew that it provided the capital, the credentialing point to allow me to have many options versus no options or minimal options.Footnote 48

Here, we see how Blackstone identifies the limitations of the parallel alternative approach to producing human and social capital, and the virtues of a supplemental approach. Initially drawing more heavily from mission-oriented schools like Regent and Ave Maria for its students, Blackstone now primarily recruits from and attracts JD candidates from Ivy League and top 50 law schools.Footnote 49 Its faculty, while variable from year-to-year, typically includes those who graduated from and now teach at nationally prestigious institutions—Notre Dame most prominent among them.Footnote 50 The mix of elements potentially allows Blackstone fellows to benefit from accruing both the mainstream elite law school and CCLM capital, creating credibility and access in both domains. This is something that the parallel alternative strategy largely does not allow for since it draws students away from the legal mainstream.

Relatedly, Blackstone recognizes the importance of networking. According to its web site Blackstone has trained, “over 1,500 law students from more than 200 law schools” and has placed these students, “in internships with more than 200 different organizations and attorneys worldwide.”Footnote 51 Blackstone, through internships, has an intentional and explicit focus on networking or providing social capital for the CCLM. While the Christian law schools we visited aspire to do the same, the evidence of being well-positioned to do so was often unclear at best. Students at Liberty and Ave Maria, for example, were not readily able to identify such networks beyond a broader statement regarding the quality of their faculty. This problem is possibly indicative of features specific to these schools as opposed to an inherent limitation of the parallel alternative strategy. It is, however, also possible to see that supplemental strategies that are not eschewing established legal institutions are better positioned to create access to the traditionally important means of legal power (Reference Hollis-BruskyHollis-Brusky 2015; Reference TelesTeles 2008).

Blackstone's internship program thus illustrates how it both pulls from, and thus stands to affect, the broader legal establishment. That is, Blackstone's capital is increased by its connection to PILOs and judges. It uses its internship program to transfer this capital to the fellows, and the fellows are then positioned to use this capital—along with that from their mainstream law schools—in order to successfully pursue high-status careers from which they stand to change law, policy, and culture.Footnote 52

Given their positioning, Blackstone is far better able to take advantage of its relationship with a PILO. Unlike Regent and Liberty, Blackstone does not have to patrol this relationship in the same way. As a supplemental training program Blackstone is not concerned about satisfying ABA requirements, bar passage rates, rankings, or situations where “the tail can wag the dog.” This less complicated relationship allows Blackstone to have a more integrated bond with ADF. While beneficial, it can also, as discussed below, pose a threat to the fellows’ abilities to fully access their mainstream legal capital.

Blackstone, while free from many of the law schools’ constraints, is not wholly independent and unchecked. It relies on funding from ADF, faculty from elsewhere, and it accepts under 200 law students per year. What's more, while recognizing the value of working within the existing legal establishment, Blackstone is still an outsider seeking to challenge that system, placing its effectiveness in utilizing traditional capital in question. The first two features give ADF far more control over Blackstone than the law schools’ founders have over their schools. This, however, is not necessarily a bad thing since Blackstone and ADF's missions and functions are so related. This synergy, coupled with ADF's ample resources, also helps ensure sufficient and stable funding.

Clearer potential deficits reside in Blackstone's control over its fellows and the organization's outsider status. First, there is an assumption by those in Blackstone that fellows face conflicting lessons and pressures from their home law schools. These schools, where fellows spend far more time, have many means for influencing students—from grades and letters of recommendation, to wanting to fit in culturally. They are thus seen as simultaneously providing benefits and threats. That said, there is also the assumption that the networks Blackstone creates will allow fellows to deal with these home institution pressures. Not surprisingly, then, multiple interviewees cited the connections made with other likeminded students as the most important and lasting benefits of Blackstone.

Interviewees also said that numerous fellows had voiced concerns about other's negative views of ADF and Blackstone, and thus they left the fellowship off of their resumes. Seen in conjunction with the above, a fundamental weakness in the supplemental strategy is revealed. The supplemental strategy's greatest potential benefit is its accessing and redirecting traditional forms of capital in the service of those seeking to change the legal/political world. The assumption is that while supplemental institutions produce fewer graduates, those graduates are better resourced and positioned than the graduates from parallel alternative schools. If alumni are wary of noting their affiliation with a supplemental institution, though, it shows an inability to fully coopt traditional forms of capital.

This risk is not limited to, but is well illustrated by Blackstone. We were told multiple times that the group is wary of the “crazy Christian” image, and so it actively works to frame itself, its associates, and its issues in ways intended to maximize acceptance. Given this, Blackstone's ability to draw faculty and students from prestigious institutions, their connections to PILOs and likely judges, and the track record of earlier (though different) self-aware supplemental organizations like the Federalist Society all suggest that the supplemental strategy can be a highly effective one in producing and placing into circulation the kinds of capital that are valuable for transformative legal movements.

Conclusion

For movement patrons looking to radically reshape law and legal culture, the “allure” (Reference Sarat and ScheingoldSarat and Scheingold 2006; Reference SilversteinSilverstein 2009) of investing in legal education and training is understandable. To recall Teles's formulation, American law schools play an important “gatekeeping” function for the profession (Reference TelesTeles 2008: 13); training and credentialing the future lawyers and judges, legitimating ideas about the law through education and scholarly production, and connecting members of the legal profession to one another through networks. But as this article has detailed, not all movements are able to leverage existing institutions to produce the resources they need for the changes they seek.

For reasons we detailed earlier—namely, a history of parallel alternative institution-building combined with a radical project to reject the shared premises of secular legalism in favor of a vision of law grounded in a “Christian worldview”—the CCLM has opted to invest in building brand new legal training institutions: three law schools (Regent Law, Ave Maria School of Law, Liberty Law) and a training program (Blackstone Legal Fellowship). Each of these institutions, founded within a decade and a half of one another, is explicitly tied to and dedicated to the broad project and mission of the New Christian Right; a mission that, were it to succeed, would result in a radical transformation of American law and legal culture. Moreover, all four are explicitly tied to Public Interest Law Organizations, Christian conservative movement institutions dedicated to Christian Right litigation.

But this movement—even armed with its own distinctly Christian conservative legal institutions—faces an uphill battle. While each of the patrons of these CCLM institutions—Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, Thomas Monaghan, and Alan Sears—built these institutions in order to pull “the wider world” toward their own distinctly Christian worldviews, as our findings reveal, the “wider world” has also served as a check on their ability to accomplish their ambitious missions.

For the law schools, financial realities, legal profession rankings and politics, limited pools of needed nonfinancial resources, and the need to operate within a tightly controlled regulatory environment have compromised their ability to recruit and keep the “right” kinds of “mission” students and faculty. Focusing on the former, the need to stay afloat financially and fill seats in the entering class has meant that these institutions have had to admit students who have weaker academic credentials; may not be mission-focused; and/or who simply did not get into a better law school. This, as we have shown, creates a tension within the student body and compromises the attractiveness of the law school for serious, “mission” students. Furthermore, the struggle at these institutions to shepherd students successfully through the bar exam (especially at Ave Maria) means that the next “generation of Christian attorneys” might not be licensed to practice law.

Blackstone, representing the supplemental strategy, seems better equipped to “pull the wider world” toward them. Indeed, this is built into their institutional design. Blackstone pulls Christian conservative faculty and students from mainstream and elite law schools and brings them together for a limited amount of time, providing supplemental training and education infused with a natural law and Christian worldview. Blackstone also recognizes the value of social capital, plugging these students into networks of like-minded individuals and providing job opportunities with employers sympathetic to the natural law and Christian worldview approach to law. Like the Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies, Blackstone is able to reach students at mainstream and even elite law students, and to provide them with a supplemental legal education that challenges and provides a distinctly Christian conservative alternative to the “liberal legal orthodoxy” (Reference Hollis-BruskyHollis-Brusky 2015; Reference TelesTeles 2008) of American law schools.

That being said, Blackstone operates with significantly less control over their faculty, which rotates year-to-year, and they are only able to reach a small number of students (~150) with their training and programming every year. If the goal of the CCLM and its Christian Right patrons is to train and produce an army of Christian lawyers to infiltrate and radically transform the legal profession from the inside, Blackstone has opted to produce instead a small Special Operations unit.

While the CCLM seems like an idiosyncratic subject of study, as our article has demonstrated, the stories it tells itself about the transformative power of legal education and the strategies driving its investments in American law schools and training programs to produce movement resources are quite familiar.Footnote 53 The three strategies we present here for building “support structures” (Reference EppEpp 1998)—institutional support for a transformative vision of law—infiltration, supplemental, and parallel alternative—have parallels in earlier transformative legal movements.

The American New Deal Revolution in the 1930s and 40s and the birth of secular legal liberalism was the product of a group of lawyers committed to a distinct vision of law who moved back and forth from the legal academy to the Roosevelt administration (Reference IronsIrons 1993; Reference KalmanKalman 1996; Reference TelesTeles 2008). The Civil Rights Movement's activities in the courts during the mid-twentieth century was supported in large part by the parallel alternative strategy in Howard Law School and other Historically Black Law Schools (Reference EppEpp 1998; Reference JohnsonJohnson 2010; Reference KlugerKluger 2004; Reference TushnetTushnet 1987). The conservative counterrevolution began in earnest with the supplemental strategy of The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies which has, as scholarship has documented, served to train and credential a generation of conservative legal academics, litigators and judges who have been able to effectively infiltrate mainstream law school faculties and positions of power (Reference Hollis-BruskyHollis-Brusky 2011, Reference Hollis-Brusky2013, Reference Hollis-Brusky2015; Reference SouthworthSouthworth 2008; Reference TelesTeles 2008).

While distinct in their ideological and legal objectives, what each of these movements have in common is an embrace of secular legalism; the Western conception of positive law that is divorced from biblical or moral traditions, and grounded in secular rather than religious principles. As we have discussed, the New Christian Right's rejection of these widely shared precepts, its mistrust of existing religious law schools, and its attachment to and belief in the biblically grounded and informed natural law has meant that the infiltration option—the lowest cost option of the three—was not seen as the most realistic or effective for building the CCLM. This strategic reality combined with the desire for more control by founding patrons Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, and Thomas Monaghan, explains the decision to opt for the highest cost option—building parallel alternative law schools—rather than what we have found to be likely the most effective option in our study; that is, investing in a supplemental approach similar to Alliance Defending Freedom's Blackstone Legal Fellowship.

Finally, we should again state that the strategy of investing in law schools and legal education as a means of transforming law more broadly is a quintessentially American strategy. But that does not mean this story has no relevance outside the American context. The Christian Right and the CCLM more specifically aspire to a global reach and orientation and are hoping to use the platform of American legal education to accomplish these broader aims. These global ambitions, and the broader evangelical project these institutions understand themselves as participating in, can best be illustrated by a plaque that explains the “Eternal Gospel Flame” that burns on the Regent University campus,

[Our mission is] [t]o prepare the United States of America and the nations of the world for the return of Jesus Christ and the establishment of the kingdom of God on earth. Our ultimate goal is to achieve a time in history when “the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea” (Habakkuk 2: 14).

Additionally, one can look to Regent's Center for Global Justice,Footnote 54 Liberty's International Law Concentration,Footnote 55 Ave Maria's web resource for internships and student activities abroad,Footnote 56 and Blackstone Legal Fellowship's marketing efforts to recruit international students through Alliance Defending Freedom's “International” arm.Footnote 57 The constraints on and potential of these efforts will vary, of course, given the particular legal and political opportunity structures available in each of these countries. Because, however, the Christian Right is motivated by an ambitious, global project that is animated by their service to law as a higher “Christian calling” from God (Reference Wilson and Hollis-BruskyWilson and Hollis-Brusky 2014), we expect these efforts to continue undeterred as long as there are resources to fund them.

Appendix

Data and Methods

The initial findings presented here are the product of qualitative methodology and interpretive data analysis (Reference YanowYanow 2003). Our primary original data are semi-structured interviews and participant observation engaged in between April 2015 and September 2016 with faculty, staff, and students at Regent, Liberty, Ave Maria, and Notre Dame law schools, as well as ADF's Blackstone Legal Fellowship. We conducted 42 interviews in total, with 14 interviews at Ave Maria, six at Blackstone, eight at Liberty, four at Regent, and 10 at Notre Dame. The interviewee breakdown consisted of 20 faculty members, 14 Administrators (six of whom were also faculty members), 14 students, and six alumni (all of whom at the time of the interviews occupied roles as faculty and/or administrators).

Of these interviews, the shortest was 25 minutes, the longest was 137 minutes, and the average was 66 minutes. All but one interview was recorded and transcribed. The single unrecorded interview—done at the interviewee's request—was accompanied by copious note taking during and after the interview. These interviews were complemented by participant observation consisting of private tours of each primary institution, and attending representative law classes at Regent, Liberty, and Ave Maria.

As we explained in the article body, Regent, Liberty, Ave Maria, and Blackstone were selected because of their clear and identifiable ties with the CCLM and because their missions explicitly articulate a desire to train a different kind of lawyer and to reorient the law and legal culture. Furthermore, because each of the three primary law schools were founded within 18 years of one another, we have relatively comparable data to examine and variables to hold constant in terms of the broader political, economic, and professional context.