Introduction

Information technology has enabled illegal markets to flourish in the computer- and mobile-mediated environment. Mobile- and computer-mediated communication encompasses the ways in which computers or mobile phones are used to communicate over the Internet, both asynchronously (e.g. posts, emails, and comments on posts) and synchronously (e.g. instant messages) [Thomson Reference Thomson, Davidson and Barrett2007]. This environment has created new opportunities for illegal entrepreneurs. Participants in illegal markets can use anonymity to their advantage in order to “hide their identities” and “use remote locations to create and participate in illicit markets” [Higgins and Wolfe Reference Higgins, Wolfe and Miller2009: 466]; escape moral disapproval; and avoid the risk of criminal prosecution. At the same time, the digital environment creates increased transaction risks. Participants find it difficult to verify the identities and intentions of others, and this anonymity leads to distrust [Gambetta Reference Gambetta2009; Lusthaus Reference Lusthaus2012]. Participants in illegal online markets rely heavily on text-based communication, which hinders trust-building among exchange partners [Riegelsberger, Sasse, and McCarthy Reference Riegelsberger Jens, Mccarthy and Joinson2007: 64]. Worse, text-based communication lacks social cues, such as verbal signals and physical presence, which undermines participants’ ability to “detect risk and uncertainty” and verify the trustworthiness of others [Cheshire Reference Cheshire2011: 49; see also Tian and Menchik Reference Tian and Menchik2016].

Using first-hand data collected through online observation and in-depth interviews, this article aims to understand why and how illegal online markets flourish under the veil of anonymity, with a particular focus on sellers who rely on the display of trustworthiness signals to attract potential buyers and who also develop innovative strategies to resolve disputes. The article applies signalling theory to China’s illegal online fiction market and investigates the signals author-sellers send to establish themselves as trustworthy and capable. Multiple signals, especially costly ones, create a separating equilibrium, allowing reputable author-sellers to set themselves apart from less reputable ones. The term “costly signals” refers to signals that require a considerable investment of resources (e.g. time, effort, and money) to produce. The article also examines the strategies author-sellers use to resolve disputes and protect their trustworthy image. This case study of China’s illegal online erotic fiction market enriches the literature on signalling theory and contributes to Varese’s production–trade–governance framework. Specifically, it enriches the understanding of trade in the absence of a third-party enforcer.

This article is structured as follows. After the introduction, it investigates the social organisation of China’s illegal online erotic fiction market. It then discusses both signalling theory and Varese’s production–trade–governance framework, the theoretical foundations on which this article is based and to which it aims to contribute. The methods and data section explains how we gained access to market participants and how our interview data was complemented by data collected through online observation. The empirical data is then presented in three sections. The first data section shows how information asymmetry affects the operation of the illegal online erotic fiction market. The second section discusses in detail the multiple signals author-sellers use to establish an honest and competent image online. The third section focuses on the dispute-resolution strategies author-sellers use to address buyers’ complaints and prevent dissatisfied buyers from posting negative comments and giving low ratings. The conclusion summarises our original contribution.

The Social Organisation of China’s Illegal Online Erotic Fiction Market

In the illegal online erotic fiction market, buyers create their own erotic fantasies by commissioning author-sellers to write erotic fiction (sexual fiction) according to the buyers’ specifications regarding plots, characters, settings, style, tone, and structure. These stories are customised commodities that the author-seller cannot resell to other clients. Although erotic fiction is legal in many countries, it is illegal and considered socially unacceptable in China. The exchange of such material accounts for over 50% of cybercrime [Wong and Wong Reference Wong, Wong, Rod and Grabosky2005]. Due to limited human and financial resources, local police in China focus on more serious crimes, such as organised crime and drug-dealing. As a result, participants in the illegal online erotic fiction market rarely face criminal punishment. The primary risks market participants have to handle are threefold. First, they must avoid attracting unnecessary attention when operating through those social media and e-commerce platforms that actively prohibit the buying and selling of pornographic material. Second, they must prevent public disclosure of participants’ personal information, which could lead to serious social condemnation. Third, they must deal with transaction disputes without the assistance of a third-party enforcer.

In this market, most participants are female and aged between 15 and 25. The illegal online erotic fiction market emerged to satisfy young women’s sexual desires, because erotic fiction is a source of inspiration for sexual fantasy for this audience [Evelyn and Wang Reference Evelyn and Wang2025]. Erotic fiction, however, is less appealing to men, who find pornographic videos more attractive. Participants can be categorised into four roles: author-sellers, buyers, agents, and informal promoters. They sometimes occupy multiple roles simultaneously, for example as author-sellers and agents. Author-sellers are individuals who write and sell customised erotic fiction in exchange for money, operating either alone or through an agent. Buyers purchase erotic fiction from author-sellers or agents. Agents market goods, receive orders, negotiate details, offer customer services, and make business decisions on behalf of the author-sellers they represent. Informal promoters help author-sellers or agents promote their products and attract buyers by following and commenting on author-sellers’ online profiles and posts and helping these author-sellers and agents defend themselves against criticism.

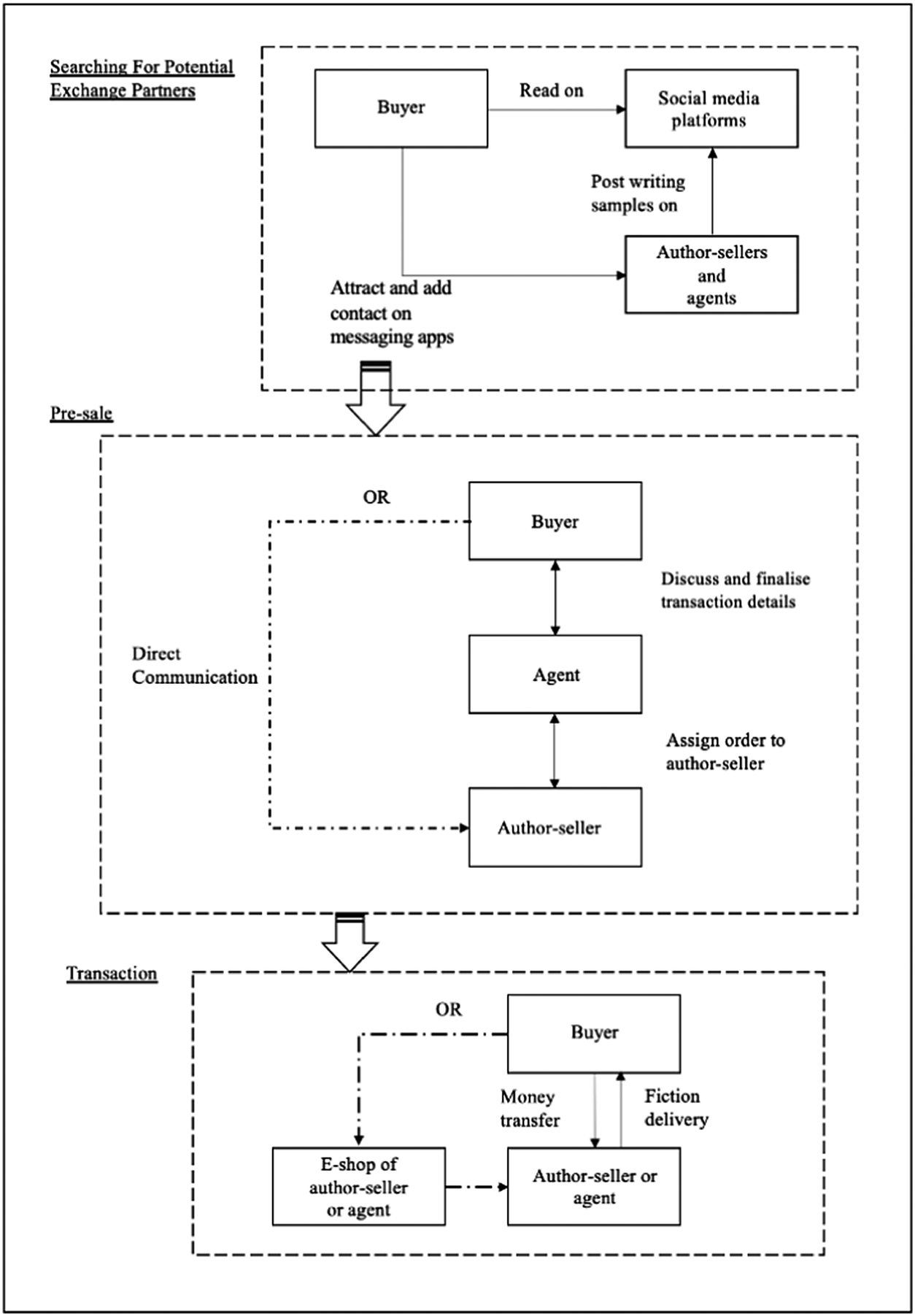

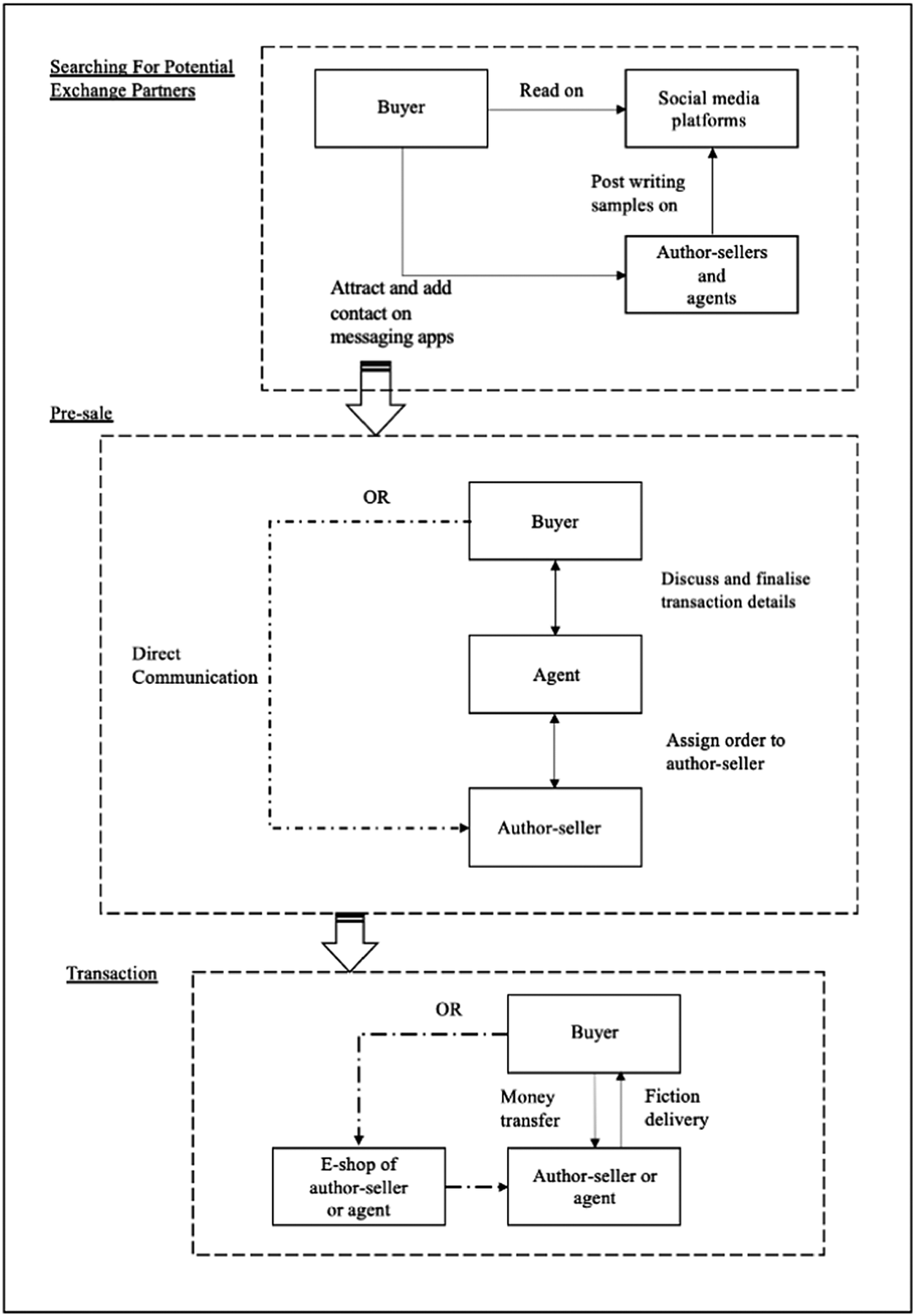

Participants coordinate their market activities and embed sale, transaction, post-sale, and marketing activities into legitimate social media platforms (see Figure 1). These online platforms allow participants to use nicknames rather than real names, which prevents their being identified. To avoid attracting attention from platform administrators, participants use insider language to refer to pornographic content and erotic organs; for example, “XP” means sexual preference, and “sandwich cookie” (jia xin bing) means threesome. To attract buyers, author-sellers and agents post writing samples on their social media platforms. When a buyer indicates interest, they follow online instructions provided by the author-sellers or agents to add the latter as friends on messaging apps. Potential buyers can request additional writing samples from author-sellers or agents and negotiate order details, such as content, price, and delivery date.

Figure 1 Key Stages of an Online Transaction

After reaching an agreement, participants can conduct transactions either on e-commerce apps or through private channels, such as a bank transfer. Author-sellers or agents can use e-commerce apps to generate payment links for buyers and instruct them to fill out the information, such as product description and quantity, agreed by both parties. As each payment is associated with a different price and a specific quantity, it is easy for participants to differentiate their orders from those of others. For orders placed through private channels, author-sellers or agents will give buyers details of an e-payment account, such as Alipay; buyers then pay through direct deposit. In the final stage of the transaction, author-sellers or agents deliver the product via email. The price can range from approximately 10 RMB (€1.30) to 600 RMB (€78) per 1,000 words, depending on the popularity of the author-seller.

Although illegal transactions are carried out on legitimate online platforms, participants in illegal transactions face much higher uncertainty levels than those involved in legal ones. This is because information asymmetry is a significant issue, and buyers lack information about pricing, product quality, and the trustworthiness of author-sellers or agents. Compared with other illicit markets, such as those for drugs and counterfeit goods, which have advanced technologies for mass production, the illegal online erotic fiction market requires author-sellers to produce customised works rather than works that can be sold to many consumers. Furthermore, there is no set of standards for assessing quality in this genre. In this market, the quality of fiction can be evaluated in two ways. First, buyers use quantifiable and objective criteria such as word count, genre consistency, and character settings to evaluate the quality of stories. Second, buyers assess the extent to which the author-seller satisfies their personal taste. Writing fiction is a creative endeavour, but an author-seller’s productivity and innovative ability can fluctuate over time, leading to varying levels of quality in terms of their output. Therefore, buyers cannot accurately predict the quality of the fiction they will receive. Nevertheless, those buyers are required to pay a deposit when placing an order, so agents and author-sellers must convey trustworthiness in order to seem reliable and competent. Since disputes frequently occur, author-sellers and agents have strategies which they use to safeguard their online image and settle disputes amicably. Our first-hand data reveals the trustworthiness signals and dispute-resolution strategies used by author-sellers, thus enhancing our understanding of signalling and trade in illegal online markets.

Theoretical Issues

This section begins by defining market signals and reviewing signalling theory, which predicts three different types of equilibrium. Signalling theory offers us an insightful perspective for the study of communication, trustworthiness signals, and cooperation in illegal markets, both offline and online. This section then discusses Varese’s production–trade–governance framework, which establishes a theoretical foundation for the study of organised crime and illegal markets. By focusing on multiple signals and dispute-resolution strategies in China’s illegal online erotic fiction market, this article aims to contribute to Varese’s framework by focusing on its second aspect: trade.

Signalling theory

Market signals, according to Spence [Reference Spence1974: 1], are “activities or attributes of individuals in a market which, by design or accident, alter the beliefs of, or convey information to, other individuals in the market” [see also Spence Reference Spence1973]. In a market where sellers have an information advantage over buyers, sellers commonly engage in a signalling game: they send signals to potential customers to “create a favourable impression or, more precisely, to affect the consumers’ subjective beliefs about the quality of their products” [Spence Reference Spence1974: 1]. In such situations, the incentive compatibility principle plays an essential role in ensuring honesty and cooperation. This principle ensures that participants’ actions and strategies in strategic interactions align with their own interests, which in turn gives rise to the provision of credible signals and the achievement of mutually beneficial outcomes [Mailath Reference Mailath1987]. By aligning with their exchange partners’ incentives, sellers are motivated to send signals that convey reliable information about their services and products, while buyers are motivated to trust sellers and engage in transactions, all of which addresses the problem of information asymmetry in the market.

Gambetta [Reference Gambetta2009] was one of the first sociologists to apply signalling theory to organised crime and the criminal underworld. Gambetta made a distinction between signs and signalling. Signs can be any observable aspect in the environment that, once perceived, shape or modify someone’s beliefs or understanding of something or someone, while signals are “any observable features of an agent that are intentionally displayed for the purpose of altering the probability the receiver assigns to a certain state of affairs or ‘event’” [emphasis in the original; Gambetta Reference Gambetta2009: xv]. In the criminal underworld, there is broad information asymmetry regarding the price and quality of goods and services and the identity and trustworthiness of potential exchange partners. Criminals, therefore, send carefully crafted signals to persuade other criminals not only that they are trustworthy exchange partners, but also that they are fearsome and will be certain to retaliate in the event of deception or betrayal [Gambetta Reference Gambetta2009]. Compared to legitimate entrepreneurs who conduct business in legal markets, criminals face a higher risk of being deceived, for two reasons. First, signals can be forged, stolen, and manipulated [Gambetta Reference Gambetta2009: xvii]. Second, formal legal institutions, such as the police and courts, are not only inaccessible to criminals but also actively suppress their activities [Varese, Wang, and Wong Reference Varese, Wang and Wong2019; Wang, Su, and Wang Reference Wang, SU and Wang2021].

In Codes of the Underworld: How Criminals Communicate, Gambetta [Reference Gambetta2009: xvii–xviii] asked: “under what conditions can a signal be rationally believed by the receiver when the signaller has an interest in merely pretending that something is true, which in the underworld is of course often?” The ideal scenario is that imposters and mimicsFootnote 1 find it very costly to fake signals, while honest participants are able to send signals with limited costs compared to the benefits gained from successful exchanges. Effective signals create a separating equilibrium, where the receiver is perfectly informed. This is an ideal solution to the problem of asymmetric information in the criminal underworld [Gambetta Reference Gambetta2009; Lin Reference Lin2022; Lin and Wang Reference Lin and Wang2024; Skarbek and Wang Reference Skarbek and Wang2015]. In contrast, when both high-quality and low-quality suppliers can send signals to potential buyers without incurring significant expenses, a pooling equilibrium is created. In this scenario, the receiver cannot distinguish between high- and low-quality suppliers, leading to market failures, such as difficulties in finding trustworthy exchange partners and the prevalence of opportunism. The situation is often complicated in practice; as Gambetta [Reference Gambetta2009: xviii] pointed out, “most signals are neither clearly pooling nor clearly sorting [i.e. separating]”; rather, they are semi-pooling. In a semi-pooling equilibrium, the signal emitted by the supplier is not clear enough for the receiver to fully distinguish whether it is a high-quality supplier or a low-quality one. One of the key takeaways from Gambetta’s Codes of the Underworld, as Dixit argues, is the significance of using multiple signals. Because “a single signal is rarely definitive” and “some signals are harder for an imposter to mimic and therefore more reliable”, the service provider needs to send “multiple mutually consistent and reinforcing signals” in order for the receiver to be sufficiently well informed [Dixit Reference Dixit2011: 140].

Although Gambetta primarily used signalling theory to explain offline interpersonal interactions in the criminal underworld, his theory has increasingly been applied to the examination of trust in cyberspace and of communication among illegal entrepreneurs on online and digital platforms. For example, in an analysis of 173 Facebook profiles of social media drug dealers, Bakken [Reference Bakken2021: 55] explored how these dealers “communicate[d] their prospective trustworthy nature through signals in their profiles and forums”. Online drug dealers establish trustworthiness by creating three types of profile: professional (using pictures and profile names to display the drugs they are selling), personal (using information about their daily lives and drug-dealing activities), and cultural [“using symbols well known to people interested in illegal drugs”, Bakken Reference Bakken2021: 60]. Laferrière and Décary-Hétu examined the trust-signalling strategies developed by reputable crypto market vendors, who establish single-vendor shops in order to minimise the uncertainties associated with police crackdowns on the crypto market and avoid the high commission fees charged by that market. Trust signals conveyed by single-vendor shops were grouped into four categories: “signals related to identity, marketing, security, and signals that directly express trust” [Laferrière and Décary-Hétu Reference Laferrière and Décary-Hétu2023: 37].

Décary-Hétu and Leppänen [Reference Décary-Hétu and Leppänen2016] also used signalling theory to investigate the signs and signals that illegal entrepreneurs used to enhance their performance in an online forum that facilitated illicit trading in credit and banking information. They discovered that the illegal entrepreneurs, who made a great deal of money in the cardingFootnote 2 underworld, possessed exceptional skills in sending and decoding signals. In parallel, Holt, Smirnova, and Hutchings [Reference Holt, Smirnova and Hutchings2016: 144] used signalling theory to analyse an online market that served as a platform for buying and selling stolen credit-card data. They argued that signals such as the quality of customer feedback, a “user status indicating the importance of long-term participation in a market” (a signal that is very expensive for fraudsters to fake), and the linguistic structure of the forum were all valuable for users seeking to demonstrate their trustworthiness.

To sum up, signalling theory offers valuable insights for the study of organised crime and illegal markets. The theory suggests three different equilibria (i.e. separating, semi-pooling, and pooling) and highlights the importance of using multiple signals in the criminal underworld. Reviewing the existing literature that applies signalling theory to various illegal online markets offers us insights into the wide range of signals and signalling strategies that have been developed by illegal entrepreneurs. This, in turn, assists our investigation of the illegal online erotic fiction market. We assume that author-sellers with the right attributes, such as honesty, competence, and trustworthiness, are more likely to send multiple signals in order to generate a separating equilibrium and make themselves distinguishable from dishonest and untrustworthy author-sellers.

The production–trade–governance analytical framework

Leading sociologist Federico Varese and his colleagues recently developed the production–trade–governance analytical framework to study the criminal activities of organised crime groups [Breuer and Varese Reference Breuer and Varese2023; Varese (Reference Vareseforthcoming)]. The framework examines three aspects of organised criminal activity: production, trade, and governance. Governance-type organised crime groups attempt to control territories and govern the underworld by controlling and regulating the production and distribution of goods and services [see also Breuer and Varese Reference Breuer and Varese2023; Varese Reference Varese and Varese2010]. Governance-type organised crime groups wield authority in local communities, the underworld, and illegal markets due to their use of violence to punish betrayers and fend off challengers, along with their exceptional ability to use social networks to gather information about the market and underworld [Campana and Varese Reference Campana and Varese2013; Gambetta Reference Gambetta2009].

Trade in the criminal underworld, on the other hand, does not require participants to control specific territories [Varese (Reference Vareseforthcoming)]. Market participants are motivated to develop stable trade relations with reliable exchange partners to obtain the commodities they need or to make money. One of the key incentives for participants to behave honestly is the desire to avoid social condemnation [Breuer and Varese Reference Breuer and Varese2023]. When governance-type organised-crime groups or other third-party enforcers are absent from the market, participants can use the bilateral-punishment strategy and the multiple-punishment mechanism to deter opportunism [Dixit Reference Dixit2004; Greif Reference Greif1993]. The former refers to the exclusion of the cheater from future exchanges with the person they cheated, while the latter refers to the exclusion of the cheater from future exchanges not only with the cheated person but also with other market participants, who become aware of the cheater’s dishonest acts due to information transmitted in social networks. These two forms of punishment are often effective in preventing uncooperative behaviour when violence is not used in the trade. Production is another essential activity in which organised crime groups are involved [Varese Reference Varese and Varese2010, Reference Varese, Carnevale, Forlati and Giolo2017, (Reference Vareseforthcoming)]. For example, organised crime groups produce and refine drugs in specific areas (e.g. the Golden Triangle and Afghanistan) or create counterfeit medicines. To resolve disputes that arise in production due to cheating, theft, competition, and betrayal, violence is commonly used. Governance-type organised crime groups emerge to regulate production of illegal commodities, settle disputes, and protect informal property rights in specific territories [Campana and Varese Reference Campana and Varese2018; Shortland and Varese Reference Shortland and Varese2016; Varese Reference Varese1994, Reference Varese2001, Reference Varese2011, Reference Varese, Carnevale, Forlati and Giolo2017].

Varese’s framework is particularly useful for researchers examining transactions in illegal markets, especially online, where violence is not an available or effective method of enforcing agreements and punishing betrayals [Wang, Su, and Wang Reference Wang, SU and Wang2021]. Varese’s theoretical discussions are useful for researchers investigating how social punishment (i.e. exclusion from future exchanges) encourages cooperation in the absence of third-party enforcers. In illegal markets, participants who want to attract transaction partners must convey signals that establish their trustworthiness and competence; they must also work to enhance their reputation and avoid negative comments from previous partners. The trade aspect of the production–trade–governance framework therefore provides insights that are particularly valuable for this study of China’s illegal online erotic fiction market. We assume that reputable author-sellers strive to maintain a trustworthy image and to settle disputes swiftly to avoid social punishment.

Methods and Data

To understand the strategies sellers use to attract customers, secure transactions, and avoid blame, we collected empirical data through in-depth interviews and online observations on various online platforms. Participants in the illegal online erotic fiction market utilise various legitimate online platforms created for lawful communications and interactions, with servers located within the Chinese jurisdiction. They must master insider language and use specific keywords to search for relevant links or information on these platforms in order to gain access to the market. The use of insider language and the embeddedness of the illegal market in legitimate online platforms enable the market to operate in a state of “open secrecy” and avoid police attention.

We gained access to a number of market participants through our active membership of a few online chat groups. These groups were created by agents or author-sellers to anonymously facilitate the marketing and promotion of erotic fiction. We gained access to the market through an invitation from a gatekeeper of a chat group in 2017. The gatekeeper and all interviewees were informed that we were researchers and were provided with details about our research objectives. Despite the fact that other chat group members and online platform users were unaware of our identities as researchers and that we were observing their online profiles and interactions, our method of online observation can be justified because (1) the participants interacted anonymously with each other; (2) there were a large number of participants active in the market, so the researchers’ presence was not significant to the situation; (3) the participants under our observation experienced no additional risk because of this research; and (4) the police have shown little interest in repressing the online erotic fiction market, and there have been very few cases of author-sellers or agents of erotic fiction being interrogated by the police.

To socialise and nurture trusting relationships with our respondents, most of whom were pursuing their bachelor’s degrees, we shared our course notes and readings as well as useful information regarding job opportunities and applications for overseas master’s programmes in the chat groups. Through daily interactions with other group members and following their discussions and messages in chat groups, we gradually learned the norms within the group, its insider language and its meanings, and appropriate ways to interact with other members, especially author-sellers. To gain a detailed and comprehensive understanding of how the market operated, we developed different interview guides based on the roles played by the research participants.

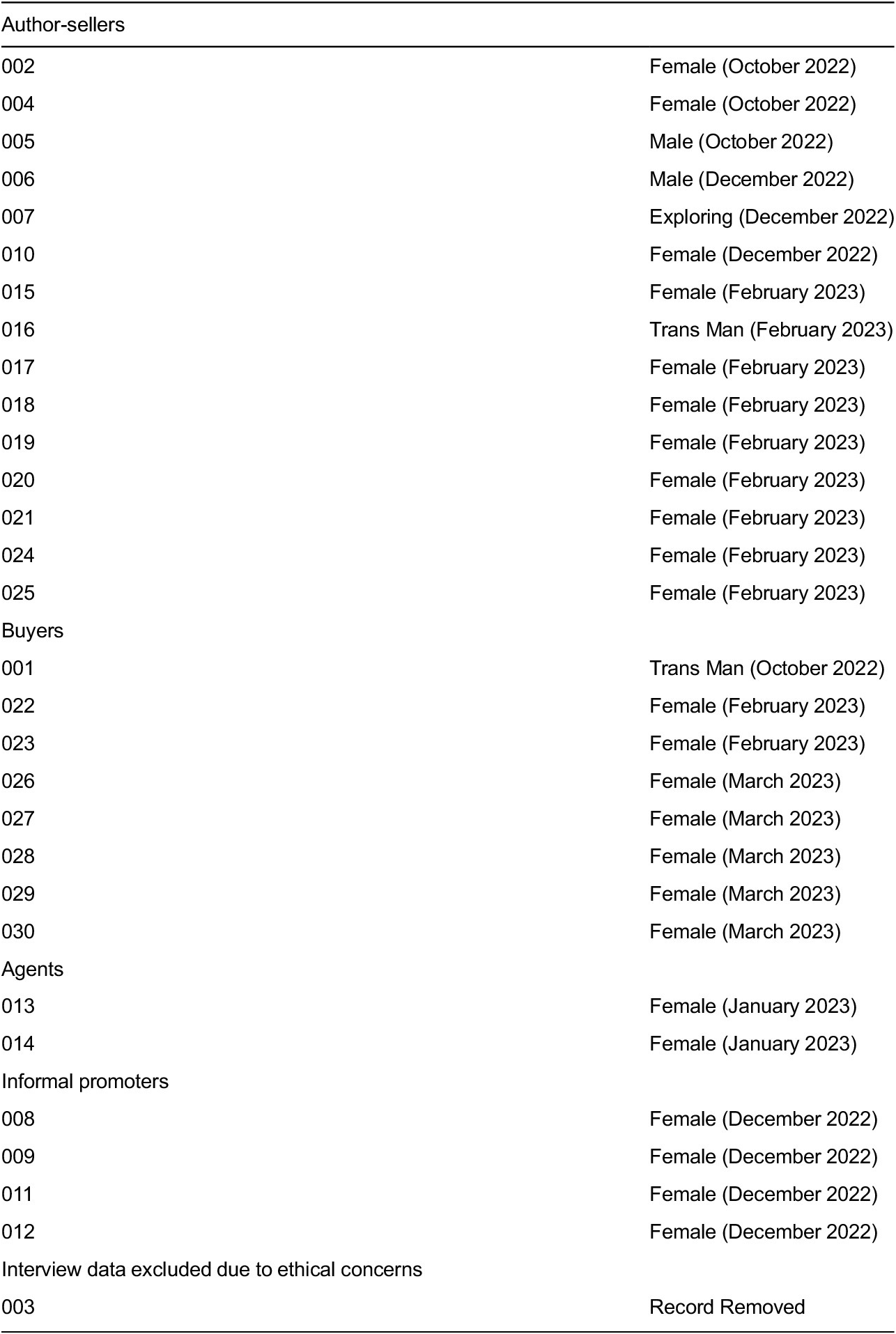

We used the snowball sampling method and conducted interviews with 30 respondents from various platforms, including eight buyers, 16 author-sellers, two agents and four informal promoters (see Table 1). For ethical reasons, we exclusively recruited adult respondents (i.e. individuals above 18 years old), all of whom provided informed consent. The interviews were conducted synchronously (e.g. face to face) and asynchronously (e.g. via private messages). Each face-to-face interview lasted approximately two hours, while each asynchronous interview took two to five days. All interviews were transcribed within 48 hours of completion, and the recordings and private messages were permanently deleted. The names of the participants were anonymised, but information regarding their age, gender, sexuality, and educational level was collected for research purposes. Although we conducted 30 interviews, only the interview data from 29 of the interviewees was eventually used for this article. This is because one interviewee (i.e., author-seller) requested that we pretend to be her customers and leave positive comments on her profile. We declined her request and decided not to use the data we had collected from her due to conflicts of interest and ethical concerns. The interview materials generated 261,096 words in Chinese, serving as a primary source of data for this research. Interview data is particularly helpful when it comes to understanding participants’ motivations for getting involved in the market, their personal experiences of trading with others, the daily operations of the market, and their use of different strategies to coordinate exchanges, negotiate informal contracts, and settle disputes.

Table 1 List of Interviewees (Gender and Date of Interview)

To ensure the validity and reliability of the collected data, the interview material was triangulated with and complemented by data collected through online observation. We utilised screen-capturing application-programming interfaces (APIs) to capture publicly accessible content on different platforms. These APIs scraped users’ profiles, online gossip, the user interfaces of the platforms, online interactions between users, and relevant news and government documents. By reviewing the screen captures, we gained insights into users’ “natural habitat as they go about their ordinary activities” [Becker, Reference Becker1963: 57]. The observation data facilitated a vivid understanding of the roles of different actors and the functions of interfaces in the online market. Additionally, an analysis of relevant news stories and government documents provided us with essential knowledge about the market that we could not have gained through interviews. Combining and triangulating the data obtained through these different channels allowed us to gain a comprehensive understanding of the social order of the market, and especially of how author-sellers and agents establish a trustworthy image, mitigate disputes, and avoid social disapproval.

How Does Information Asymmetry Affect the Illegal Online Erotic Fiction Market?

The Chinese government prohibits the production, publication, and distribution of pornographic materials, including erotic fiction. On the one hand, the criminalisation of sexual content creates moral constraints on individuals and shapes their perception of such content; on the other hand, it drives author-sellers, buyers, and agents of erotic fiction into the criminal underworld, giving rise to a booming illegal market. In response to the government’s prohibition of pornographic materials, participants demonstrate their resistance to government policy by defying the law, engaging in the illegal market, and asserting their right and freedom to write, sell, and read erotic fiction.Footnote 3 In order to facilitate exchanges, participants use legitimate platforms to market their products, coordinate transactions, and communicate with others. Although buyers, author-sellers, and agents fear detection and punishment, we did not discover any cases in which participants had been punished by the criminal justice system. The most essential task for participants in the online erotic fiction market is to address the risks and challenges caused by information asymmetry, such as concerns about the pricing and quality of the product and the trustworthiness of the participants in the exchange.

As the illegal market relies on various platforms to function, the transaction process is rather complicated. Participants utilise different platforms for different purposes. They employ social media platforms such as Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, to post and read writing samples and search for potential exchange partners. They then utilise messaging apps such as QQ, an instant messaging tool, for communication and the dissemination of reputation information. Some may conduct transactions on e-commerce apps, such as Taobao, the Chinese version of eBay. The embeddedness of the different stages of the transaction process into different platforms can sometimes impede the efficient dissemination of information among market participants. It further increases the participants’ workload in terms of verifying the identities of others because each participant is required to register on different platforms, often under different usernames.

Information asymmetry between sellers and buyers is significant in the online erotic fiction market. In each transaction, the author-seller possesses more information than the buyer about the quality of the product offering. The author-seller has strong incentives to use this information advantage to earn more profits than they would have earned in a more open market, while buyers are unable to access the same level of information as sellers, putting them at a disadvantage in negotiations around price and exchange conditions. Dishonest sellers promote their businesses by using high-quality samples to convince buyers to place orders and pay a deposit (e.g. 80% of the total price). However, upon receiving the final product, buyers may find that the quality is lower than that demonstrated in the writing samples.Footnote 4 Rampant dishonest behaviour can drive consumers out of the market and eventually lead to market failure. To gain the trust and confidence of buyers, author-sellers strive to signal trustworthiness (see Table 2). Such signals can be divided into those that are costless and those that are costly for mimics to reproduce. In the illegal online erotic fiction market, the use of multiple and consistent signals helps high-quality suppliers stand out from the rest (i.e. in a separating equilibrium), an observation which we discuss later in this article.

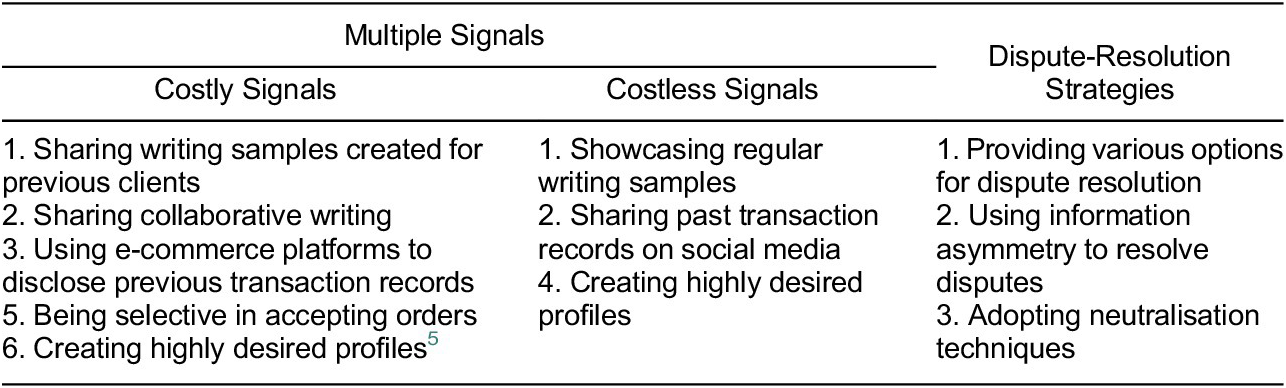

Table 2. Author-Sellers’ Multiple Signals and Dispute-Resolution Strategies

Information asymmetry is significantly influenced by anonymity. Anonymity prevents market participants from identifying and verifying the intentions and identities of others online. It also ensures that participants’ online activities remain unknown to others in their networks, which helps them avoid potential legal repercussions and reduces the risk of social condemnation. At the same time, it also reduces participants’ sense of personal accountability for their activities. Dishonest participants can continue their fraudulent behaviours without being held accountable for previous misconduct, by switching to alternative accounts and using different online nicknames. For instance, some dishonest sellers pretend to be “sincere” buyers and use new accounts to place orders with other sellers. Once they receive the erotic fiction, they plagiarise it and resell it at a premium.Footnote 6 Thus, sellers have to be cautious when selecting buyers. They not only require a deposit, which usually amounts to around 80% of the total price, but also demand that new buyers submit identifiable information (e.g. a screen capture of their Alipay account number), or request an additional fee as collateral.Footnote 7

Moreover, fiction writing requires authors to use their imagination and creativity to weave a story and construct characters. Legitimate fiction is written for any reader who is interested in buying and reading it, but erotic fiction is written for specific buyers who request the author to create certain characters and plots. In other words, authors of erotic fiction are not permitted to resell or reuse what they have written for previous clients. To maximise their profits, author-sellers are inclined to accept more orders than they are able to manage. The pressure of dealing with these orders often compels them to plagiarise their previous works or those of others, extend delivery deadlines, or supply low-quality fiction.Footnote 8 This gives rise to a significant number of disputes between author-sellers and buyers. Because customised fiction is written based on the individual requirements — regarding plots, characters, and settings — of the person who commissions the work, the unique story cannot easily be reused if the buyer withdraws from the deal. To address transaction disputes, author-sellers have to develop a range of strategies to appease dissatisfied clients and complete transactions, and also to prevent negative reviews, as these could have a significant impact on their reputation and future business (see Table 2). The following sections discuss the multiple signals and dispute-resolution strategies outlined in Table 2.

Multiple Signals

Our empirical data shows that author-sellers often send multiple signals that effectively create a separating equilibrium and solve the problem of asymmetric information. Among these signals, some are costly for mimics to reproduce, while others are not. When buyers choose author-sellers, they gather evidence to evaluate the trustworthiness of author-sellers based on factors such as reputation, writing ability, and style, as well as their commitment to the business.Footnote 9 To showcase the quality of their writing, author-sellers often choose to share writing samples created for previous clients on their online profiles, which is an essential signal conveyed by reputable author-sellers. It is common for author-sellers to include a statement such as “Thank you sugar daddy @ [buyer’s username]” before presenting the writing samples, which clearly distinguishes these from regular writing samples,Footnote 10 which are not expensive for author-sellers to produce. Buyers often find regular writing samples less helpful because their quality can differ significantly from the quality of the work they ultimately receive in their own orders.Footnote 11 However, they find writing samples from previous orders to be very helpful because these serve as evidence showcasing the writing abilities of the author-sellers and provide a clear idea of what they can expect when they receive their customised fiction.Footnote 12 Furthermore, where author-sellers exhibit writing samples created for previous clients on their online profiles, this sends a strong signal to potential buyers that those author-sellers are both popular and reputable. This signal is expensive for author-sellers to send because obtaining consent from previous clients to share such samples can be challenging; clients own the rights to the work and may be reluctant to share it with others.Footnote 13 Given that author-sellers who are new or less popular in the market can only present regular writing samples instead of samples from previous orders, showcasing writing samples created for previous clients becomes an essential strategy which reputable author-sellers can use to signal their trustworthiness and attract clients.

Another strategy that is only available to popular author-sellers is the sharing of collaborative writing, created through working with other popular author-sellers, on their online profiles. When people are uncertain in their decision-making, they often rely on the opinions of others as a form of social proof in order to make their final decision [Wooten and Reed Reference Wooten and Reed1998]. In the online erotic fiction market, involvement in collaborative writing is considered a form of social proof granted by influential others, such as chatroom group administrators and popular author-sellers. These administrators often organise collaborative writing projects that only allow recognised author-sellers to participate.Footnote 14 In order to be eligible to join collaborative writing projects, author-sellers need to establish their own reputation and submit a short erotic fiction piece for quality review. By posting collaborative writing on their profiles, author-sellers can showcase endorsements from other well-known author-sellers as well as their affiliation to elite writing groups. The incentive here lies in the idea that only reputable and capable author-sellers are willing to obtain third-party endorsements, while less capable and less reputable author-sellers do not seek endorsements from popular authors because it would expose them to rejection.Footnote 15 The sharing of collaborative writing is therefore a credible signal of trustworthiness, peer recognition, and competence.

In addition, author-sellers display their professionalism and competence by disclosing detailed records of past transactions. Author-sellers who rely on e-commerce platforms – such as Taobao – to facilitate transactions can use e-commerce architectures to provide potential clients with valuable information, including ratings, clients’ comments, and past transaction records. This is a strong signal that demonstrates author-sellers’ popularity and writing ability, as e-commerce platforms do not allow users to change their ratings, comments, or transaction records. By exhibiting successful transactions, high ratings, and positive comments from previous clients, author-sellers can demonstrate their competence at delivering high-quality fiction in a timely manner.Footnote 16 In fact, author-sellers’ ratings, comments, and past transaction records have become essential information for potential clients in their efforts to choose the most suitable exchange partners.Footnote 17

Author-sellers who operate their businesses outside of e-commerce platforms often provide the records of previous transactions on their social media profiles (e.g. Weibo) or other forums. According to Holt, Smirnova and Hutchings [Reference Holt, Smirnova and Hutchings2016: 139], “risk-averse buyers may seek out vendors who have been on a forum for some time because they can identify the seller’s past history and determine their reputation”. In order to increase their credibility, author-sellers upload screen captures of Excel spreadsheets containing information such as buyers’ nicknames, transaction dates, and fiction genres. Some author-sellers even disclose detailed records of transactions from the previous four years, which can bolster buyers’ confidence in making orders because “experienced author-sellers are more trustworthy [than less experienced ones], as they are less likely to run away [and delete their accounts]”.Footnote 18 These records may make potential buyers eager to purchase their services from experienced author-sellers, since getting to work with an experienced author-seller is a “rare opportunity”.Footnote 19 But these records of previous transactions could have been fabricated by the author-sellers. Creating such records is not costly for author-sellers. When interviewees were asked to make a comparison between author-sellers who shared their transaction records on social media and those who used e-commerce platforms to share their records, most respondents reported that the records shared on e-commerce platforms were more reliable; this made the services of these e-commerce platform users more attractive to potential buyers.

Author-sellers also create highly desired profiles by showcasing their current limited availability to handle new orders as a result of large number of buyers having already placed orders with them. This generates a sense of urgency in potential buyers as regards purchasing these author-sellers’ services. As Cialdini and Trost [Reference Cialdini, Trost, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindezey1998] have argued, creating a sense of scarcity is a powerful persuasive tactic that is commonly employed to increase sales. Based on our observations, author-sellers often disclose their order delivery schedules on their profiles. Some top-rated author-sellers display messages such as “If you order this month, the earliest delivery date is six months later”, “My schedule is full, and I am no longer able to take new orders this month”, and “The service is closed now; please come back later.”Footnote 20 These messages are strong signals because they exclude or discourage potential buyers from approaching that author-seller. This type of message is usually reliable because only popular author-sellers, who do not lack clients, can afford to send such a signal. These author-sellers create sought-after profiles to show their popularity, and buyers appreciate the opportunity to purchase their services; they are often willing to pay above market price.

However, less popular author-sellers utilise other strategic messages to attract potential clients. For example, an informal promoter reported that she saw a profile of a less popular author-seller which stated that she would only accept orders this month and would not be taking new orders for the following six months.Footnote 21 Here, the author-seller not only created scarcity but also set a false deadline, which did not prevent her from taking new orders in the following months. As Cialdini [Reference Cialdini2009] argued, making a product available for only a limited period can put intense pressure on potential buyers who are fearful of “missing the opportunity”.Footnote 22 However, the signal (setting a false deadline) sent by the less popular author-seller is not costly for them to send, and the consequence of being socially punished if detected by other participants is not significant, because the author-seller does not possess much social capital (e.g. reputation).

To increase their appeal to buyers, some author-sellers are highly selective in accepting orders. They exhibit this in two ways: first, by only accepting orders from previous buyers, and second, by only accepting orders for fiction in specific genres. Being selective in accepting orders is an expensive signal that only reputable author-sellers can afford to send, because it excludes many, if not most, potential buyers. In the first scenario, the authors will include the statement “previous buyers only” on their profiles. They explain that they do this because they cannot ensure the trustworthiness of new buyers; therefore, once they have established a reputation and created a large customer base, they decline orders from new buyers.Footnote 23 By selecting which buyers to work with, author-sellers give those customers a sense of privilege, which creates an additional incentive for them to make repeat purchases. A buyer mentioned in an interview that due to the need to maintain her prestige, which allowed her to place orders with her favourite author-sellers, she could not change her account and nickname.Footnote 24 Some author-sellers even establish a hierarchy of buyers, where those positioned in different ranks are required to pay varying prices, with new buyers paying premium prices.Footnote 25

In the second scenario, some author-sellers provide details about their preferences for writing fiction in specific genres; thus, they only accept orders that align with their interests.Footnote 26 In their online profiles, they include statements such as “I do not take fiction orders related to child pornography”, and “I decline orders involving social taboos.”Footnote 27 One author-seller justified her selectivity in accepting orders by arguing: “my time is so valuable; therefore, I take each order seriously”.Footnote 28 Buyers appreciate the selectivity of author-sellers because this indicates that they are highly responsible and that they are committed to each order. Author-sellers’ selectivity in fiction writing within specific genres often results in the delivery of high-quality content.Footnote 29 As one buyer emphasised, “When an author-seller’s preferences align with mine, I find great enjoyment in reading the erotic fiction they have written for me.”Footnote 30

The ideal scenario in this market is the existence of a separating equilibrium, where clients are well-informed and able to distinguish top-rated author-sellers from incompetent or dishonest ones. However, the reality is often less than ideal. The market is rather complicated: the ratio of top-rated suppliers to all suppliers in the market is low, and the majority of suppliers fall between the two extremes of top-rated suppliers and completely dishonest or incompetent suppliers. This constitutes a semi-pooling equilibrium, where most suppliers can afford to send some signals, but these signals are not enough to make a supplier stand out from the crowd. Even though top-rated suppliers can stand out by showcasing multiple expensive signals, they can only meet a fraction of the market demand. Middle-rated suppliers are the main service suppliers in the market. Due to the increasing demand for erotic fiction and the fact that, if cheated, buyers only face monetary loss and not criminal prosecution, buyers are still willing to hire these mid-rated suppliers. Consequently, the market is rife with transaction disputes.

Dispute-Resolution Strategies

Disputes are not uncommon in the online erotic fiction market.Footnote 31 In addition to the reasons discussed above, the rise in disputes is caused by three additional factors. First, buyers may struggle to clearly illustrate their requirements for the work of fiction they are ordering in terms of its plot and characters; second, there are no universal standards buyers can use to assess the fiction’s quality, which means they must evaluate it based on their personal preferences and individual criteria; and third, author-sellers’ creativity and productivity fluctuate over time, which means buyers may receive inferior products or encounter significant delays. An agent complained that “some buyers state that they have no quality requirements [when placing orders], but we frequently encounter transaction disputes due to their dissatisfaction with the final product’s quality”.Footnote 32 Even when buyers provide clear and detailed instructions regarding the end result, author-sellers may fail to meet their expectations due to fluctuations in their creativity and productivity. One author-seller acknowledged their own inconsistency in fiction quality, stating: “For some orders, I take them seriously; however, for others, I lose motivation halfway through.”Footnote 33

Moreover, to maximise their profits, author-sellers often accept more orders than they can manage, resulting in issues such as plagiarism, low-quality work, and extended delays. Since buyers who trust author-sellers are required to pay a deposit, they are highly selective in choosing them. As a result, author-sellers with negative feedback and records of dishonest behaviour are excluded from consideration by potential buyers. Thus, author-sellers and agents must develop strategies to signal their commitment to the buyer’s interests and goodwill in order to prevent complaints, resolve transaction disputes, and avoid negative comments from clients.

Author-sellers and agents adopt different dispute-resolution strategies at different stages of the transaction process. If disputes arise during the sales process, author-sellers persuade buyers to settle peacefully by providing various options for dispute resolution. For instance, in one case a buyer wanted to request a refund from an author-seller due to her dissatisfaction with the sales support provided (i.e. the author-seller and agent did not adequately address questions raised by the buyer concerning the plot and character settings). The agent and author-seller presented the buyer with three options: (1) a refund from the author-seller, (2) a refund from the agent, or (3) to have the order transferred to another author-seller, who would take it over at a price discount (e.g. a 10% discount). By providing the buyer with a number of choices to select from, the agent and author-seller signalled their commitment to the buyer’s interests, which turned out to be an effective way of addressing the buyer’s dissatisfaction and avoid negative comments from them.

Furthermore, agents and author-sellers prefer to manipulate the transaction process by utilising the low-ball technique to attract customers and exploiting information asymmetry to resolve any disputes caused by delays in delivering the final product. Unlike those salespeople who initially offer a lower-than-market price and favourable terms to attract a buyer and then increase that price or reveal less favourable terms after the buyer has purchased the service [Cialdini et al. Reference Cialdini, Cacioppo, Bassett and Miller1978], agents and author-sellers usually promise an early delivery date in order to entice a potential buyer into committing to a purchase and then extend that delivery date. Extending delivery dates enables agents and author-sellers to accept more orders and earn higher profits. However, this gives rise to buyer dissatisfaction. Being unpunctual is perceived by buyers as a signal of incompetence and untrustworthiness.Footnote 34 One agent argued that “delivering erotic fiction on time is even more important than the quality of the erotic fiction”.Footnote 35 In order to avoid blame, agents and author-sellers attribute delays to unforeseen challenges. Because buyers have already waited for a few months and are unable to obtain information regarding exactly what has happened, they often have no choice but to accept the new delivery dates. As a buyer noted, “if they cannot submit the draft on time, as long as they explain the reasons for the delay to me and give me a new delivery date, I still consider them responsible and trustworthy”.Footnote 36 However, dishonest author-sellers abuse the low-ball technique and informational asymmetry to scam buyers. One buyer accused an author-seller of repeatedly delaying the delivery date while continuing to raise the price and requesting additional payments. As a result, the buyer exposed the author-seller’s fraudulent behaviour on a forum, causing significant damage to the author-seller’s reputation.Footnote 37

Techniques of neutralisation are oftenFootnote 38 employed by author-sellers to address transaction disputes caused by issues of plagiarism. Plagiarism can have serious consequences for an author-seller’s reputation because many victims can compare the plagiarised work with the original and disclose the evidence on different platforms.Footnote 39 Despite the significant harm caused by plagiarism to the reputation of author-sellers, it occurs frequently because it is an essential strategy by means of which an author can take on more orders than they could otherwise manage and obtain higher profits. Therefore, dealing with disputes caused by plagiarism is a highly skilled task for many author-sellers. Some attributed their plagiarism to an absence of rules on how to quote or excerpt from other people’s work, the lack of intellectual property rights protection in the market, or their own experiences of victimisation (i.e. their works had also been plagiarised by others).Footnote 40 For example, they argued that there were no guidelines (e.g. concerning quotations and citations) in the market to help them avoid plagiarism and that they did not present the works of others as their own, but merely quote them.Footnote 41 Maintaining calm when addressing accusations of plagiarism from buyers and providing reasonable explanations are helpful strategies for solving disputes. Buyers who have been persuaded to accept the justifications provided by author-sellers will continue to place orders with these author-sellers.Footnote 42

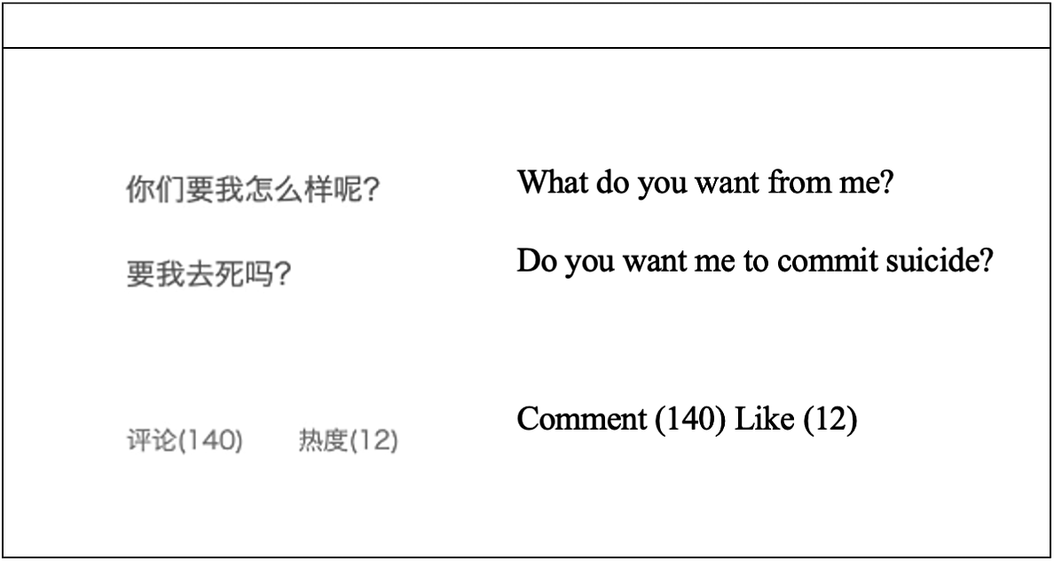

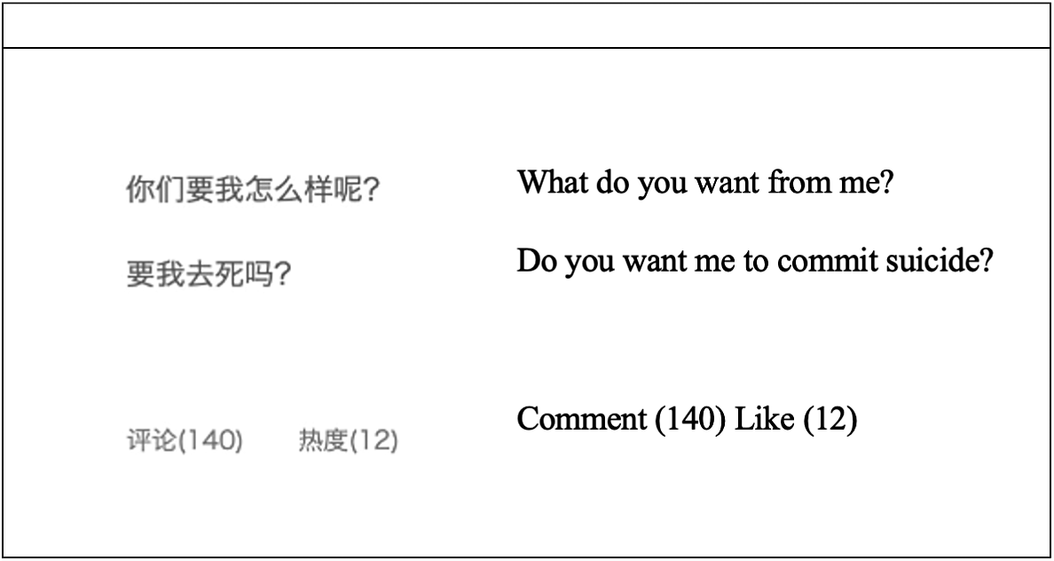

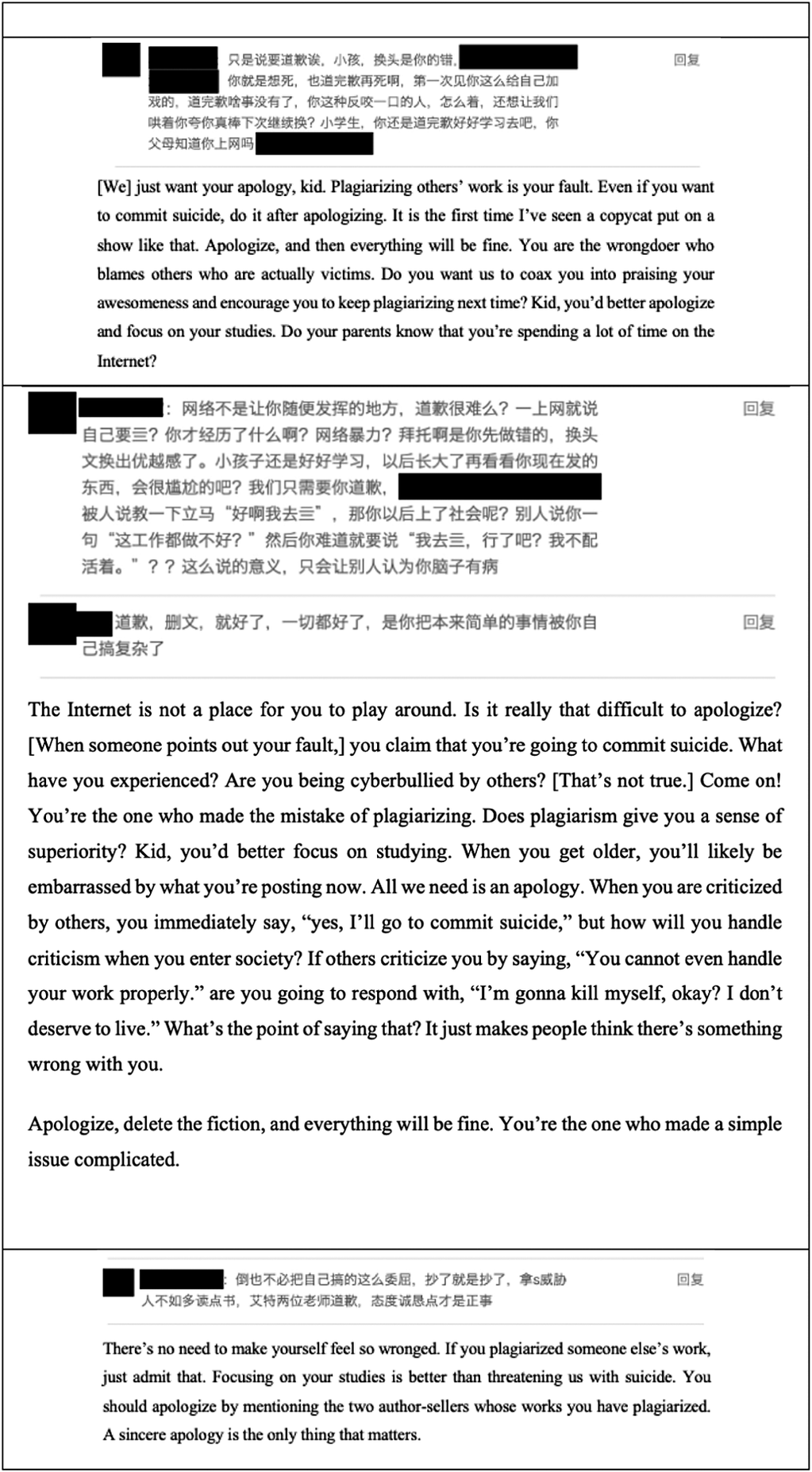

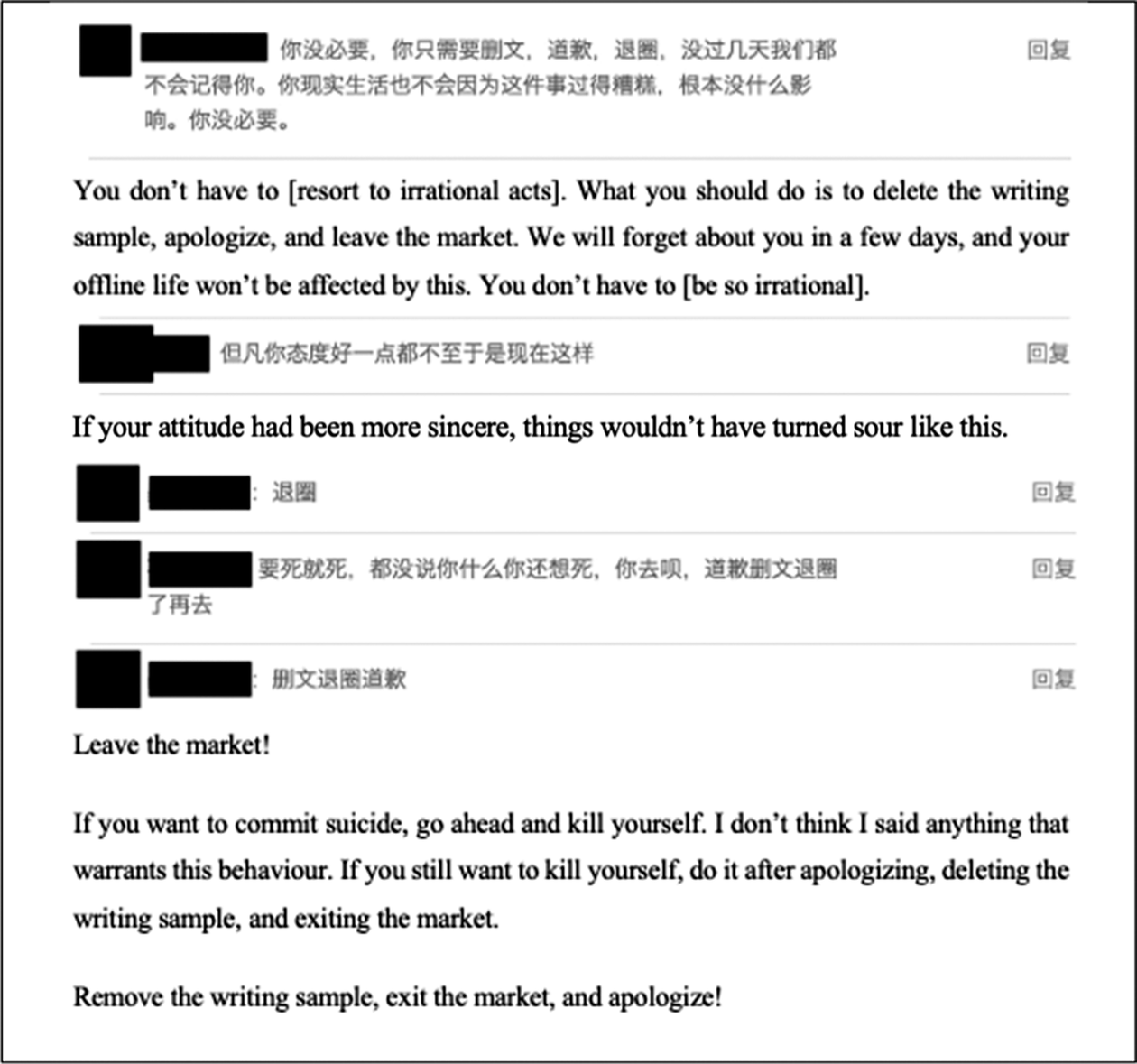

In contrast, author-sellers who fail to develop appropriate strategies to safeguard their standing risk reputational ruin and eventual expulsion from the market. Figure 2 depicts a post from an author-seller who was accused of plagiarism and deployed the emotional blackmail tactic [Forward Reference Forward1998] rather than neutralisation techniques to avoid blame. The author-seller posted on her profile that she would commit suicide if the buyer continued to accuse her of plagiarism. The threat of suicide did not constrain the buyer’s behaviour, instead resulting in strong resistance from the buyer, who persistently requested an apology from the author-seller. The author-seller’s transgressive action was soon questioned and criticised by other norm-abiding market participants (see Figure 3). Although the apology did not change the fact of her plagiarism, it was a signal that the norm violator had to convey in order to admit her fault and acknowledge the harm caused to the market by her actions. Being able to apologise also signals a norm violator’s accountability for damages and willingness to remedy damages and accept punishment [see Tavuchis Reference Tavuchis1991; Schneider Reference Schneider2007]. In contrast, as shown in Figure 2, the author-seller’s attempt to manipulate the buyer and avoid apologising signalled immaturity and insincerity to buyers. In an interview, one experienced buyer emphasised: “it is useless to threaten us [buyers]. [Because] we don’t even care.”Footnote 43 When buyers perceive that their freedom to criticise an author-seller’s norm-breaking behaviour is being challenged, they often react in dramatic ways: not only do they leave negative comments on the author-sellers’ profiles, but they also share information about the author-sellers’ dishonest behaviour on different forums and various social media platforms, which may ultimately expel these author-sellers from the market [see Figure 4; Brehm and Brehm Reference Brehm and Brehm1981].

Figure 2 Using the Threat of Suicide to Handle a Plagiarism Accusation

Figure 3 Buyers’ Resistance to the Author-Seller’s Threat of Suicide

Figure 4 Buyers’ Criticisms and Demands that the Author-Seller Leaves the Market

To conclude, author-sellers and agents must develop a range of effective strategies in an illegal market, where there are no accepted criteria on which to evaluate product quality, services are customised, and the issue of plagiarism is prevalent. Based on our observations and interview data, author-sellers and agents resolve disputes and avoid blame by utilising a number of strategies, which include providing various possible solution options, exploiting information asymmetry, and using their neutralisation skills.

Conclusion

Drawing on insights from signalling theory and Varese’s production–trade–governance framework, this article focuses on the multiple signals and dispute-resolution strategies of author-sellers in the illegal online erotic fiction market in China. Based on empirical data collected through online observation and in-depth interviews, the study investigates the risks caused by information asymmetry, including a lack of transparency in terms of pricing and product quality and the limited amount of information that is available to assess the trustworthiness of market participants. Since buyers are required to pay a deposit to place orders, author-sellers are incentivised to convey multiple signals to potential customers. These signals can be divided into two categories: costly signals, such as sharing writing samples created for previous clients, sharing collaborative writing, using e-commerce platforms to disclose detailed records of past transactions, and being selective in accepting orders; and costless signals, such as sharing regular writing samples and revealing past transaction records on social media. Reputable and competent author-sellers are better at sending multiple signals, especially costly ones, in order to stand out in the market. These signals create a separating equilibrium.

Although the separating equilibrium is an effective solution to asymmetric information problems, our empirical data shows that disputes are still prevalent in the online erotic fiction market. This discrepancy arises for two reasons. First, top-rated author-sellers who can send multiple costly signals account for only a small proportion of suppliers. As a result, buyers often have to hire mid-rated author-sellers. Mid-rated author-sellers can send some signals, but these signals are not completely credible. This creates a semi-pooling equilibrium, where buyers are not fully informed, leading to various types of transaction dispute. Other reasons for this discrepancy include the fact that the writing needs to be customised, universal criteria for evaluating product quality are absent, and author-sellers are financially motivated to accept more orders than they can fulfil. As a result, resolving disputes and avoiding social disapproval have become essential tasks for most author-sellers. They have thus developed a range of dispute-resolution strategies, including offering various solution options during the sales process, exploiting information asymmetry to resolve disputes caused by delivery delays, and using neutralisation techniques to address disputes arising from plagiarism. These strategies effectively resolve transaction disputes.

This empirical study of China’s illegal online erotic fiction market enriches the existing literature by applying insights from signalling theory and Varese’s production–trade-governance–framework to a previously unexplored illegal online marketplace. This market is unique because the goods and services being exchanged differ significantly from those in other illegal markets, such as illicit drugs and counterfeit goods. Participants face considerable transaction-based risks and uncertainties due to the market’s core features, including the absence of widely accepted criteria for evaluating product quality, the customisation of services, and the pervasive issue of plagiarism. The use of empirical data enabled us not only to investigate the unique online market context that both facilitates and constrains transactions but also to obtain an in-depth understanding of the techniques and strategies developed by market participants, particularly author-sellers, to secure clients, mitigate risks, and resolve disputes. This research offers valuable insights and fresh knowledge that could provide beneficial insights for future studies of other illegal online markets.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Federico Varese, Heather Hamill, Martina Baradel, Emilia Ziosi, Niles Breuer, Zora Hauser, Elena Racheva, Alae Baha, Qiaoyu Luo, Fanqi Zeng, Wanlin Lin, and Jingyi Wang for their valuable comments on this manuscript. All errors remain our own.

Ethics approval

This research obtained ethics approval from Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Hong Kong (Reference Number: EA210466).

Funding

This work was supported by two grants from the Research Grants Council (RGC) in Hong Kong: first, General Research Fund (Project No. 17608821); second, Early Career Scheme (Project No: 27615017).