An extensive literature has associated military pressures (i.e., war and the threat of war) with the development of fiscal capacity (Besley and Persson, Reference Besley and Persson2009, Reference Besley and Persson2011; Dincecco, Reference Dincecco2009, Reference Dincecco2015; Gennaioli and Voth, Reference Gennaioli and Voth2015; Karaman and Pamuk, Reference Karaman and Pamuk2010; Tilly, Reference Tilly1990). Much of this literature is based on cross-national correlations between military pressures and fiscal outcomes (e.g., taxes as a share of GDP or taxes per capita), primarily in Early Modern Europe and during the 20th century.

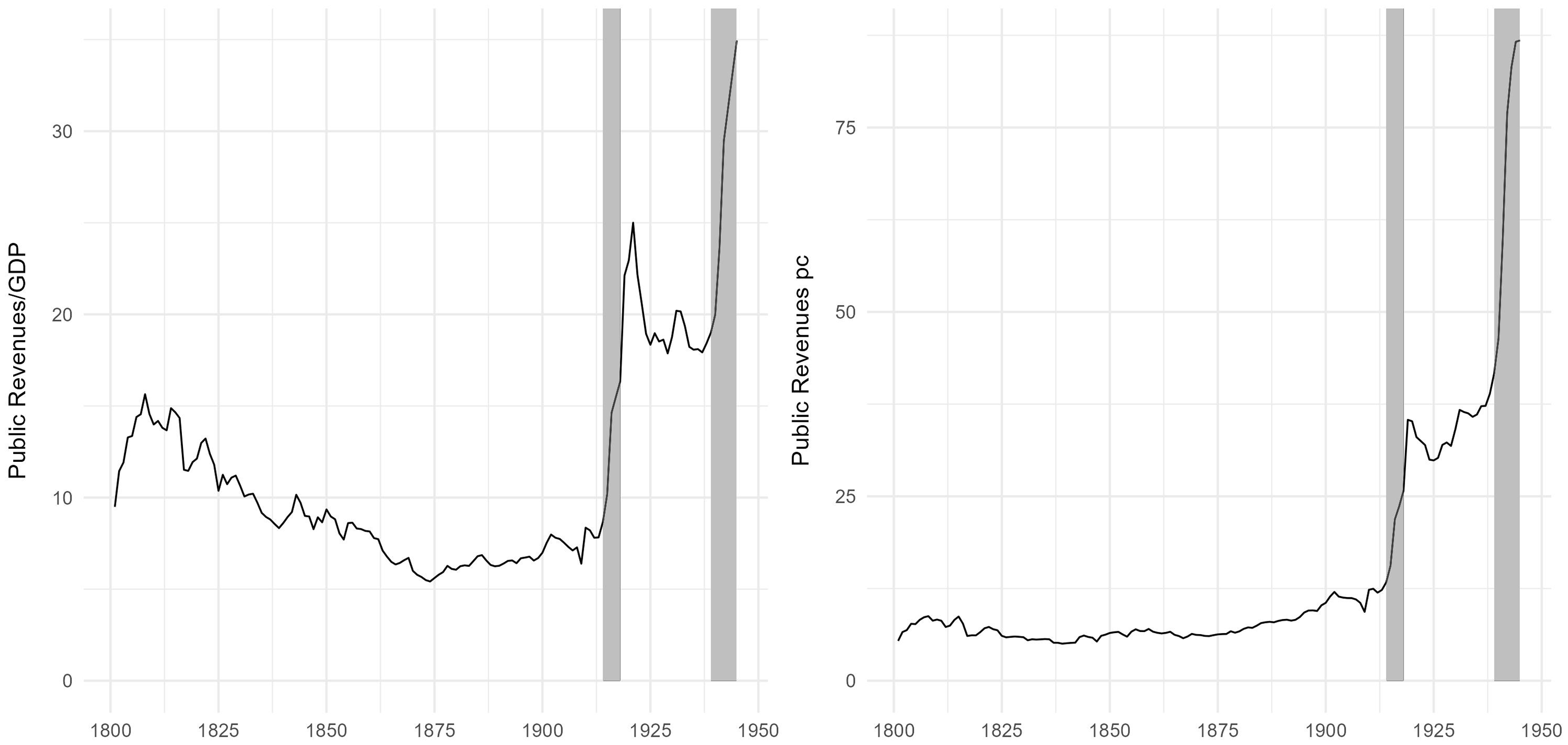

The relationship between war and fiscal development during the long 19th century, however, is not as clear. On the one hand, several studies show that countries that fought more wars between 1789 and 1913 are more likely to have higher levels of fiscal capacity today (Besley and Persson, Reference Besley and Persson2009: 1236; Dincecco and Prado, Reference Dincecco and Prado2012: 175; Queralt, Reference Queralt2019). On the other hand, public revenues grew very little during the 19th century, especially compared to their dramatic explosion after the World Wars (Lee and Paine, Reference Lee and Paine2023). In many countries that are today characterised by high levels of fiscal capacity, such as the United Kingdom, public revenues as a share of GDP actually declined from the 1800s to the 1870s (see Figure 1). Moreover, 19th-century conflicts were, with few exceptions, rather limited and rarely led to large increases in tax revenues (Centeno, Reference Centeno2003; Goenaga et al., Reference Goenaga, Sabaté and Teorell2023; Hoffman, Reference Hoffman2015). What explains this apparent contradiction in the literature between the short- and long-term effects of 19th-century military conflicts on the development of fiscal capacity?

Figure 1. Public revenues of central government in the UK as a share of GDP (left panel) and public revenues per capita at constant prices of 1939 (right panel), 1800–1945. Sources: Public revenues, revenue ratios and population data from Thomas and Dimsdale (Reference Thomas and Dimsdale2017); inflation data from Williamson (Reference Williamson2021).

In this article, we delve into the case of the UK to examine the micro-level mechanisms that, according to bellicist theory, link military pressures to the development of fiscal capacity. Using supervised and semi-supervised tools for computational text analysis to generate measures of issue salience and presence, as well as quantitative and qualitative methods of analysis, we examine the role that military pressures played in policy debates around tax reform in the British Parliament between 1803 and 1913. The UK represents a particularly interesting case due to its significant engagement in global military affairs and its pioneering role in introducing modern forms of taxation during this period.

Our analyses provide robust evidence that, during those years, military pressures were associated with greater salience of fiscal issues and lower levels of contestation in debates on taxation. Concerns about military pressures were especially prominent in discussions around income taxation prior to the People’s Budget of 1909. Even if most 19th-century wars were of limited scale and did not lead to immediate increases in public revenues, military pressures were constantly invoked to successfully oppose attempts to repeal the personal income tax from the 1840s to the 1880s.

These results suggest that military pressures were integral to the piecemeal construction and consolidation of a modern fiscal apparatus. The British fiscal system was able to swiftly respond to the financial stress that came with the World Wars partly because the legal instruments, administrative capabilities, and informational resources needed for income taxation were built and preserved during the second half of the 19th century, despite repeated attempts to dismantle them (Daunton, Reference Daunton2002:12). These findings join recent studies that analyse not only the factors that foster investments in fiscal capacity, but also the factors that are associated with the dismantling of fiscal capacity already in place (Suryanarayan and White, Reference Suryanarayan and White2021).

Bellicist theories of fiscal capacity

Warfare has long been associated with investments in fiscal capacity, particularly in the context of Early Modern Europe and the 20th century (Besley and Persson, Reference Besley and Persson2011, Reference Besley and Persson2009; Dincecco, Reference Dincecco2015, Reference Dincecco2009; Gennaioli and Voth, Reference Gennaioli and Voth2015; Karaman and Pamuk, Reference Karaman and Pamuk2010; Tilly, Reference Tilly1990). At the core of these studies is the claim that military pressures affect actors’ preferences and ability to coordinate around fiscal reforms.

First, military pressures strain public finances, pushing policymakers to increase tax revenues or secure current revenue streams (Thies, Reference Thies2005). Interstate wars and rivalries have been associated with the development of standing armies (Downing, Reference Downing1993; Tilly, Reference Tilly1990), higher military expenditures (Eloranta, Reference Eloranta2007), investments in technological development (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman2015), infrastructural projects (Gennaioli and Voth, Reference Gennaioli and Voth2015), spending in public education (Aghion et al., Reference Aghion, Jaravel, Persson and Rouzet2019; Paglayan, Reference Paglayan2022), and the expansion of social services (Obinger and Petersen, Reference Obinger and Petersen2017). These expenditures push policymakers to pursue reforms needed to raise public revenues, both in the short term to face the immediate costs of military mobilisation and in the long run to meet war-related debts (Queralt, Reference Queralt2022). Such reforms may involve changes in tax rates that may lead to immediate increases in tax revenues. However, they may also involve other types of efforts to strengthen fiscal capacity, such as the adoption of new forms of taxation (Frizell, Reference Frizell2024; Seelkopf et al., Reference Seelkopf, Bubek, Eihmanis, Ganderson, Limberg, Mnaili, Zuluaga and Genschel2021), the consolidation of emergency taxes introduced on a temporary basis (Peacock and Wiseman, Reference Peacock and Wiseman1961; Rasler and Thompson, Reference Rasler and Thompson2017, Reference Rasler and Thompson1985), or investments in the administrative (Teorell and Rothstein, Reference Teorell and Rothstein2015) and informational resources of the fiscal bureaucracy (Brambor et al., Reference Brambor, Goenaga, Lindvall and Teorell2020; Garfias and Sellars, Reference Garfias and Sellarsn.d.; Hau et al., Reference Hau, Peres-Cajías and Soifer2023; Nistotskaya and D’Arcy, Reference Nistotskaya and D’Arcy2023).

Second, military pressures facilitate the coordination of collective action necessary for such investments in fiscal capacity. Wars impose shared costs in the form of territory losses and the destruction of lives and property, and highlight common interests among state and societal actors (Besley and Persson, Reference Besley and Persson2011, Reference Besley and Persson2009). Consequently, military pressures can foster rally-around-the-flag dynamics (Baker and Oneal, Reference Baker and Oneal2001; Frizell, Reference Frizell2024; Lai and Reiter, Reference Lai and Reiter2005), which align the preferences of political elites and the citizenry on fiscal matters and open opportunities for tax reforms. In the face of foreign threats, both elites and citizens may be willing to accept higher taxes in exchange for greater investments in external defence (Bates and Donald Lien, Reference Bates and Donald Lien1985; Besley and Persson, Reference Besley and Persson2009; Peacock and Wiseman, Reference Peacock and Wiseman1961) or to compensate those most affected by the war effort (Scheve and Stasavage, Reference Scheve and Stasavage2016). Military pressures may also facilitate fiscal centralisation, weakening domestic competitors of the state (Dincecco, Reference Dincecco2009; Gibler, Reference Gibler2010). Finally, military pressures can facilitate consensus among political elites around the need to preserve existing fiscal instruments, even when they remain unpopular among constituents.

Most of the Bellicist literature has been framed in structural terms, linking macro-level factors related to international conflict to macro-level changes in the state. In contrast, micro-level claims about the preferences of policymakers have rarely been directly analysed (with notable exceptions including Scheve and Stasavage, Reference Scheve and Stasavage2016 and Queralt, Reference Queralt2022). This may be particularly relevant to explain why 19th-century wars have been associated with long-term effects on fiscal capacity (Besley and Persson, Reference Besley and Persson2009:1236; Dincecco and Prado, Reference Dincecco and Prado2012:175; Queralt, Reference Queralt2019), while studies using 19th-century data have not found evidence of substantial short-term effects (Cardoso and Lains, Reference Cardoso and Lains2010; Centeno, Reference Centeno2003; Goenaga et al., Reference Goenaga, Sabaté and Teorell2023). A detailed examination of these micro-level claims can yield valuable insights into the impact of military pressures on the policymaking process and how this may have contributed to incremental changes in fiscal capacity.

Hypotheses: using legislative debates to analyse the micro-foundations of bellicist theory

Legislative debates offer a rich source of empirical material to directly observe the relationship between military pressures and policymakers’ stated preferences about taxation. Legislative debates are institutionalised practices of public deliberation and negotiation between elected representatives aimed at reaching agreements, making policy decisions, and communicating policy positions to other policymakers and the general public (Ilie, Reference Ilie, Wodak and Forchtner2017). In most Western countries, legislatures have been the main institutional forum for the negotiation of public finances since the early 19th century.Footnote 1 In the UK, Parliament has controlled public finances since at least the Glorious Revolution (Cox, Reference Cox2016). If military pressures had an impact on the development of fiscal capacity, there should be evidence of the mechanisms outlined by bellicist theory in parliamentary debates.

Based on the Bellicist literature, we derive two theoretical expectations about how military concerns should relate to debates on taxation. First, if military pressures push policymakers to engage in fiscal reforms, we expect the presence of military concerns in parliamentary debates to be associated with greater salience of fiscal issues. Second, if military pressures create windows of opportunity for fiscal reforms, we expect the intensity of contestation in fiscal debates to be lower in the presence of military pressures. A reduction in rhetorical confrontation among MPs is likely indicative of broader agreements on fiscal policies.

In addition to these two hypotheses based on the previous literature, we propose a third exploratory hypothesis. If military pressures mattered for the long-term development of fiscal capacity, we should observe evidence in the parliamentary record that they were associated with at least one of the following outcomes: the consolidation of existing sources of tax revenue, the adoption of new fiscal instruments, or the preservation or expansion of the administrative or informational foundations of tax collection. The next section unpacks these hypotheses and presents our empirical strategy.

Data and method

To evaluate these theoretical expectations, we analysed the transcripts of parliamentary debates in the UK from the last years of the Napoleonic Wars to the outbreak of World War I (1803–1913). During those years, the UK adopted fiscal innovations that later spread to the rest of the world. As the preeminent global power, the UK also experienced various kinds of military pressures at the time, including major European conflicts (the Napoleonic Wars or the Crimean War), colonial wars (e.g. the Boer Wars), and changes in the geopolitical environment. Therefore, assessing the importance of military pressures for fiscal policymaking in the UK is crucial to understanding the development of fiscal capacity in a highly influential case.

Our data comes from a newly-collected corpus of parliamentary debates in the UK from 1803 to 2023, as they have been transcribed and digitalised by Hansard (Goenaga et al., Reference Goenaga, Pashley and Sabaté2024). Previous efforts by Eggers and Spirling (Reference Eggers and Spirling2014), Rheault et al. (Reference Rheault, Beelen, Cochrane and Hirst2016), and Goet (Reference Goet2019) created corpora of debates in the House of Commons for different periods. We build on these efforts to create a single corpus, segmented at the speech level, for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The corpus is then matched to MP data on partisanship (for the House of Commons), collected by Eggers and Spirling (Reference Eggers and Spirling2014) and complemented by us with data from the EveryPolitician Project (2024).

We rely on supervised and semi-supervised tools to produce measures for each debate of (1) the salience of taxation; (2) the presence and salience of military pressures; (3) the intensity of discursive contestation; and (4) the salience and intensity of contestation around specific forms of taxation.Footnote 2 We then structure our analyses in three stages corresponding to each of our main hypotheses. First, we evaluate the expectation that the presence of military issues in a debate is associated with higher fiscal salience. Second, we examine whether the presence of military issues is associated with lower contestation in debates on fiscal policy. The third part proceeds inductively to examine the content of debates on taxation. In a first step, we analyse the relationship between the presence of military issues and the salience of and contestation around specific taxes and how that changed over time. Having found a strong association between military pressures and debates on the personal income tax, which also tended to increase as the century progressed, we carry out qualitative analyses of those debates to assess whether they were related to the introduction of new fiscal instruments, the consolidation of existing ones, or the expansion of the fiscal bureaucracy.

Salience and presence of fiscal and military issues

We start by analysing the association between the presence of military issues and the salience of taxation. For our purposes, issue salience refers to the extent to which an issue represents the main focus of a debate. Mechanically, the more a debate focuses on a particular issue, the less we expect it to focus on other matters (there is simply no room for other topics to be equally salient). Consequently, measures of the salience of specific policy issues are associated with lower salience of other policy issues.

Conversely, issue presence refers to whether an issue recurrently comes up in the discussion, even if it is not the main matter under consideration. If military pressures moved fiscal issues to the top of the political agenda, references to military pressures should be very much present in debates about fiscal policy. In other words, we operationalise the importance of military pressures in debates about taxation as the presence of military matters in such debates.

The presence of military issues in debates about taxation may be attributed to several factors. During wartime, military concerns are likely to be present in everyone’s minds and thus influence the preferences of MPs with regard to other topics. In particular, military concerns may compel MPs to direct their attention towards the need to secure or expand public revenue streams to meet the costs of warfare. However, MPs may also be more likely to raise fiscal issues in the context of military pressures for strategic reasons, seeing them as windows of opportunity to advance their prior policy positions (for example, to increase military expenditure or to achieve fiscal centralisation). While in the first scenario, MPs would be largely reacting to perceived military pressures, in the latter, they would be evoking military concerns strategically to pursue their policy goals. In both cases, references to military pressures are used to justify fiscal policy positions. Therefore, any of these mechanisms would be consistent with the expectation that military pressures are associated with heightened salience of fiscal policy in legislative debates.

To measure issue salience, we assume that a higher proportion of keywords related to a policy realm signals greater attention to these matters relative to other issues. For instance, we expect the keywords ‘tax’, ‘taxable’ and ‘taxation’ to be mentioned more in debates about fiscal issues than in debates on other topics. We follow a dictionary approach to identify every time certain keywords related to either fiscal or military issues were mentioned in a debate, a common measurement strategy in text-as-data approaches (Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Roberts and Stewart2022:178–181), using the Quanteda package in R (Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Watanabe, Wang, Nulty, Obeng, Müller and Matsuo2018). We develop comprehensive lists of keywords and bi-grams for both policy realms to capture changes over time in linguistic conventions used to refer to military and fiscal issues (presented in Appendix A). We then divide the number of times our fiscal or military keywords were mentioned by the total number of words uttered in that debate. We reproduce our analyses with different versions of these dictionaries, where we exclude words that could also be used in discussions on unrelated issues, and the results hold.

To measure the presence of military issues in parliamentary debates, we code each speech in which at least one of our military keywords was mentioned by an MP. We then divide the number of such speeches by the total number of speeches in that debate. Unlike the indicator of military salience, this measure captures the extent to which MPs brought up military issues in their speeches, even if the discussion was primarily about other matters. In Appendix B, we provide a more detailed discussion of our measures of issue presence and salience, showing that they capture different properties of debates.

The correlation between military salience and presence is, of course, high (p = 0.78). Debates that focused on military issues (and thus, showed high levels of military salience) also featured high levels of military presence (most speeches mentioned military concerns). However, there were several debates with high levels of military presence but low levels of military salience. Table B1 in the Appendix illustrates this distinction by listing the titles (assigned by Hansard) of twenty debates with low military salience but high military presence. Most of those debates were not about military issues (e.g., they were not about war operations or army supplies), but rather focused on fiscal policy, agricultural subsidies, or foreign affairs. Nevertheless, at least half of the speeches in those debates referred to military concerns. We are particularly interested in this subset of parliamentary debates. If our theoretical expectation applies to the UK in the 19th century, we should be more likely to observe higher levels of fiscal salience in those sessions than in sessions with equally low levels of military salience but also low levels of military presence.

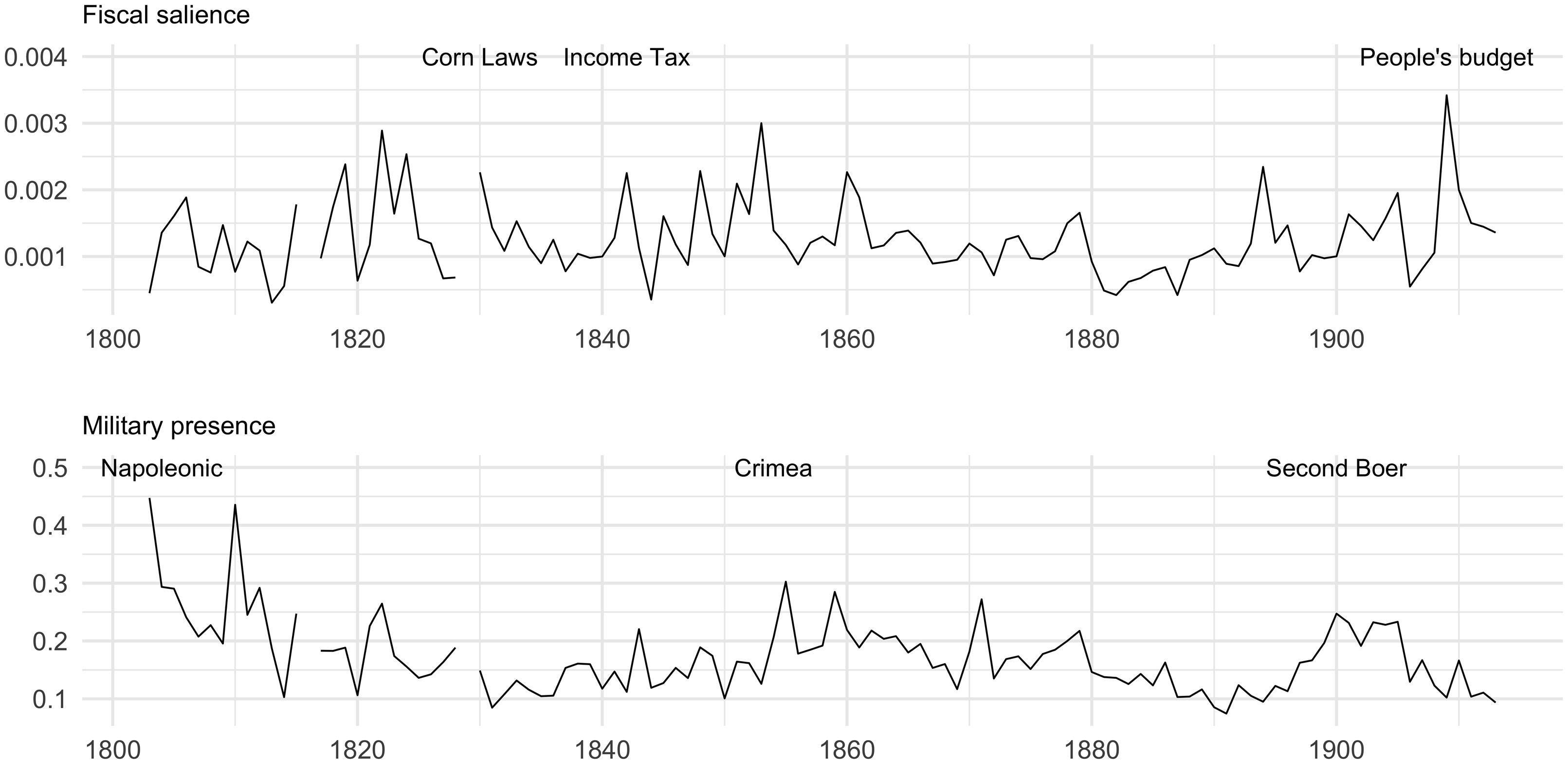

Figure 2 plots the average yearly value for fiscal salience (upper panel) and military presence (lower panel) from 1803 to 1913. Fiscal salience peaks in years when major tax reforms were enacted, such as the temporary reintroduction of the income tax in 1842 and the ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909. We also observe peaks in 1853 and 1860, in the context of heated discussions about the renewal of the income tax. Unfortunately, we do not capture the first introduction of the income tax in 1799 or its repeal in 1816, since there are no parliamentary transcripts available for those years.

Figure 2. Fiscal salience and military presence in the British Parliament, 1803–1913. Notes: yearly averages of fiscal salience (fiscal keywords as a share of total words, top panel) and military presence (speeches mentioning military keywords as a share of total speeches, lower panel).

The main peaks in military presence coincide with major wars, such as the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), the Crimean War (1853–1856), and the Second Boer War (1899–1902), as well as during discussions of major military reforms in the 1870s. This indicates that military issues were, as expected, mentioned frequently during wartime, but also during periods of relative peacetime but heightened geopolitical and colonial tensions, such as the late 1850s up until the 1880s. This is one of the main contributions of our measure, as it complements existing data on external rivalries and military competition (e.g., Klein et al., Reference Klein, Goertz and Diehl2006; Thompson, Reference Thompson2001), offering direct daily observations of policymakers’ concern with foreign threats, even when these conflicts did not escalate into outright war.

Contestation in fiscal debates

The second theoretical expectation asserts that the presence of military issues in parliamentary debates should be associated with lower contestation around fiscal policy among policymakers. To examine this claim, we use sentiment analysis. Specifically, we measure the intensity of contestation by calculating the dispersion of the sentiment score (more positive or more negative) across speeches in each debate. First, we use the package sentimentr in R (Rinker, Reference Rinker2019) to identify the tone of each intervention. The method tags all polarised words with +1 (positive words) or −1 (negative words) based on a pre-defined dictionary from the syuzhet package (Jockers, Reference Jockers2023). We manually trimmed the dictionary to ensure that words related to fiscal or military issues were not treated as polarised terms. For example, we removed ‘tax’ from the dictionary, since it was treated as a polarised word with a negative score. The algorithm then weights each polarised word using valence shifters (negations, amplifiers, and de-amplifiers). All the weighted context clusters are summed and divided by the square root of the word count at the sentence level, and each intervention is given the weighted average score of all sentences.

We then calculate the standard deviation of the sentiment score of all speeches in a debate. This indicator represents a reasonable proxy for the intensity of contestation in the discussion, as it is unlikely that a session with conflicting positions would yield a low level of sentiment dispersion. Similarly, we do not expect high levels of consensus to be associated with very different tones in the debate. Figure B3 in Appendix B illustrates our measure of contestation in one debate, plotting the values of the sentiment score for each speech and how the variation across speeches captures the intensity of contestation in that discussion.

Measuring rhetorical contestation poses an interesting methodological challenge, as contestation is likely to be closely related to the length of the debate. On the one hand, more contentious debates are likely to be longer and involve more speeches, while, on the other hand, longer debates also contain more words, which mechanically tends to produce smaller standard deviations in the sentiment score across speeches. We discuss this issue in more detail in Appendix E, where we explore how the structure and length of a debate relate to our measures of contestation, and we evaluate how sensitive our results are to different ways of accounting for debate structure.

In the supplementary materials, Appendix A details the construction of the corpus; Appendix B describes the construction of our variables; Appendix C presents descriptive statistics. Appendices D, E, and F provide robustness checks for all our analyses based on different model specifications, alternative samples, and placebo tests. Since during the 19th century, there were several institutional reforms that might have affected the structure and content of the debates, most notably the expansion of suffrage (Spirling, Reference Spirling2016) and changes in the party system (Cox, Reference Cox2024), we include additional analyses where we account for these institutional factors. In Appendix G, we reproduce our main analyses but using a semi-supervised machine-learning technique – Keyword Assisted Topic Models (KeyATM) – to measure military and fiscal salience (Eshima et al., Reference Eshima, Imai and Sasaki2024). The Pearson correlation coefficient between our dictionary-based measure of fiscal salience and the estimated proportion of the fiscal topic in our KeyATM is 0.70, with a standard error of 0.005, which shows that these two measures are tapping into the same underlying quantity of interest through very different data generation processes. Our results hold in all of these analyses. We also present additional analyses using KeyATMs to examine the prominence of military concerns relative to other policy goals, such as redistribution or trade policy, in fiscal debates, as well as the prominence of different kinds of external threats (e.g., colonial wars and geopolitical tensions among European powers). In Appendix H, we extend our analyses to the 1914–2023 period to explore how the role of military pressures in fiscal debates changed over time. Finally, Appendix I presents additional qualitative evidence in support of our main findings.

Results: military presence and fiscal salience

We begin by evaluating the first theoretical expectation, according to which the presence of military concerns should be associated with higher salience of taxation. The benchmark OLS model is given by equation (1):

![]() $ FS$

is our dictionary-based measure of fiscal salience,

$ FS$

is our dictionary-based measure of fiscal salience,

![]() $ MP$

is our dictionary-based measure of military presence,

$ MP$

is our dictionary-based measure of military presence,

![]() $ Z$

is a vector of controls for debate-varying observable characteristics, and

$ Z$

is a vector of controls for debate-varying observable characteristics, and

![]() $ \gamma $

are year fixed effects.

$ \gamma $

are year fixed effects.

All the statistical models use individual debates as the unit of analysis. The main analyses are based on debates with more than ten speeches with at least 20 words each. This is to ensure that there was a substantive discussion, but the results hold for longer and shorter debates. The continuous variables are standardised to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 to facilitate interpretation. We report robust standard errors to account for heteroscedasticity (the results hold if we instead cluster standard errors by year).

In order to examine the association between military presence and fiscal salience, we need to account for debates that were entirely devoted to military affairs. Such debates would show high levels of both military salience and presence, and, because they were primarily devoted to military issues, they would leave very little room for other issues (such as fiscal policy) to be also salient. Therefore, those debates would mechanically bias the results against the first theoretical expectation.

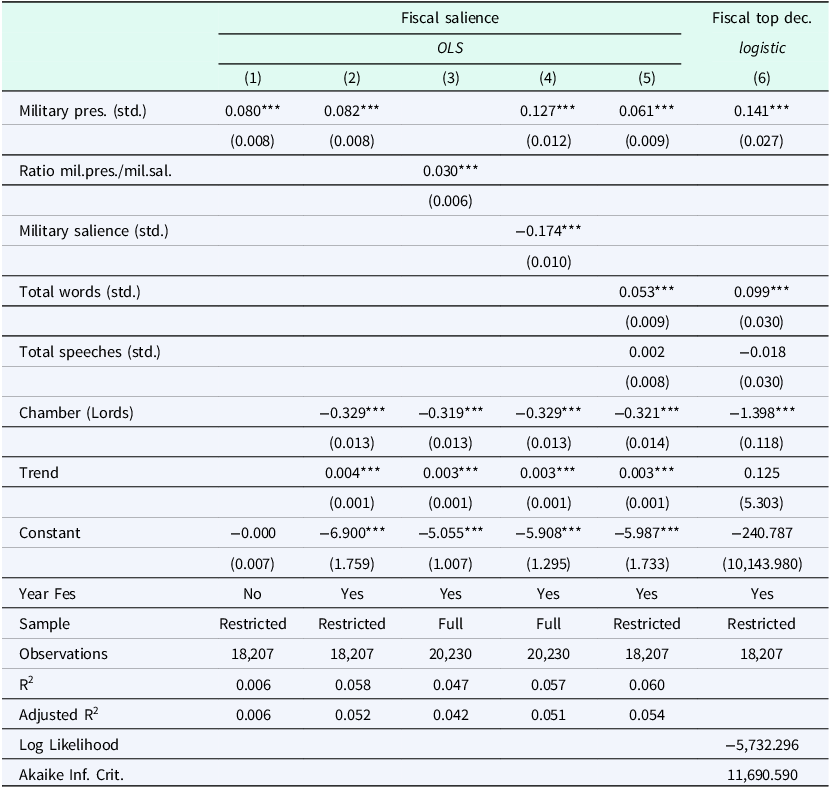

The models presented in Table 1 address this issue in three different ways. In Models 1 and 2, we drop from the sample debates in the top decile of military salience, which capture debates mainly devoted to military operations. Model 1 presents a simple bivariate regression without any controls or fixed effects, while Model 2 includes a set of controls: year fixed effects, a temporal trend, and a dummy variable for debates in the House of Lords. In both models, the presence of military concerns in a debate is associated with higher levels of fiscal salience. In Model 5, we include additional controls related to the length of the debate (total number of words and total number of speeches) and the coefficient for military presence remains positive and statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level.

Table 1. Military presence and fiscal salience

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01; Robust standard errors reported for Models 1–5.

Models 3 and 4 account for debates devoted to military operations through two alternative strategies. In model 3, we use the original sample of debates (we do not drop debates in the top decile of military salience), but our independent variable of interest is instead the ratio of military presence over military salience. This variable thus assigns higher values to debates in which military keywords came up in several speeches but overall represented a small fraction of the total words in the debate. Here again, we find a positive and statistically significant coefficient.

In model 4, we also keep the full sample of debates and return to our main independent variable of military presence, but now include military salience as a control. Again, the coefficient for military presence is positive and statistically significant. By contrast, military salience is negatively correlated with fiscal salience, indicating that, indeed, the more a debate focuses on military affairs, the less room it leaves to discuss other issues (such as taxation). Finally, model 6 explores a different modelling strategy in which we estimate the probability that a debate was in the top decile of the fiscal salience distribution through logistic regression. The positive and significant coefficient for military presence indicates that debates where military issues were repeatedly mentioned were more likely to be devoted to taxation. Based on this model, debates that did not mention any military terms had a 15% predicted probability to be primarily about taxation, whereas debates in which every intervention mentioned a military term had a 30% probability of being devoted to fiscal policy.

The results are in line with the claim that military concerns were associated with the greater salience of fiscal issues. According to Model 5, a change of one standard deviation in military presence is associated with a change of 0.061 standard deviations in fiscal salience. Going from debates where military concerns were not mentioned at all to debates in which military issues were mentioned in every speech is associated with over one-third of a standard deviation higher fiscal salience.

Robustness checks

We report robustness checks in Appendix D. Tables D1 and D2 restrict the analyses to debates with more than 5 and 20 speeches, respectively. The results hold.

Table D3 reproduces Models 1 and 5 of Table 1 with the following two placebo-dependent variables: the salience of education and criminal justice issues. In contrast to fiscal salience, both of these issues are negatively correlated with military presence. This indicates that military presence is specifically related to fiscal salience (but not to other policy realms) and that our results are not driven by some general discursive pattern.

Public debt may serve as a short-term strategy to deal with the financial pressures generated by military conflicts (Centeno, Reference Centeno2003; Queralt, Reference Queralt2019). If this were the case, our models would be underestimating the relationship between military presence and fiscal salience, since debt may substitute for tax reform in the short term (postponing tax debates to a later date). Alternatively, public debt could coexist with discussions on taxation, as MPs would recognise that raising new loans represents a means of deferring future tax reforms. Table D4 examines these possibilities. It shows that military presence is, in effect, positively correlated with the salience of public debt. However, the association between military presence and fiscal salience remains positive and significant even after controlling for the salience of public debt. When analysing the interaction between military presence and debt salience, we find that debates in which debt was discussed tended to amplify, rather than substitute, the relationship between military presence and fiscal salience.

Table D5 accounts for partisan dynamics, showing that the relationship between military presence and fiscal salience is not driven by the possibility that MPs from a specific party dominated debates on these issues.

To address the temporal structure of the data, we run separate analyses for each decade (Figure D1). We also present models with standard errors clustered by year, as well as multi-level models in which we nest debates either by year or by Parliament (Table D6). This allows us to explore whether broader institutional changes, such as suffrage expansions (which have been previously associated with increases in taxation), are driving our results (Spirling, Reference Spirling2016). In all those analyses, military presence is consistently associated with higher levels of fiscal salience.

Table D7 replicates Models 1, 2, 4, and 5 from Table 1, but this time, using military salience (instead of military presence) on the right-hand side of the equation. Results show that military salience is negatively correlated with fiscal salience when using the entire sample (given the mechanical effects discussed above), but it turns positive and significant once we exclude military debates. This reinforces our hypothesis that debates that feature military issues (but are not exclusively about military matters) are associated with higher fiscal salience. Nevertheless, we prefer our measure of military presence as it is closer to our conceptualisation of how military pressures may influence parliamentary debates.

Table D8 looks at the relationship between the average level of military presence in preceding debates and fiscal salience. The findings indicate that only the most recent debates yield positive and significant coefficients, albeit with smaller magnitudes than those observed in our primary models. This suggests that what matters in terms of fiscal salience is the extent to which MPs were concerned at that time by military matters (even if these concerns stem from past military events).

Finally, Table D9 looks at how our measures of military presence, military salience, and fiscal salience differed during years of intense wars compared to peacetime. Wartime was indeed associated with higher levels of military presence and salience in parliamentary debates. We do not find evidence that fiscal policy was more salient during wartime, but rather it was specifically the presence of military issues in debates that was associated with higher levels of fiscal salience. This suggests that military issues were often raised in discussions about taxation in anticipation of potential future conflicts or after a conflict had already ended.

In Appendix G, we present the results of regression models using the KeyATM estimates to identify military and fiscal debates. We consistently find evidence that military presence is associated with greater focus on fiscal issues. Other analyses using KeyATMs tell a similar story, showing that military concerns were prominent in fiscal debates during the second half of the 19th century, especially compared to other concerns associated with taxation, such as redistribution and trade. We also find that references to colonial wars largely drove mentions of military issues in those debates, with geopolitical pressures from other European powers becoming more prominent after the 1880s.

Appendix H reports similar analyses for the periods 1914–1945 and 1946–2023. As we would expect, results hold to a certain extent for the two World Wars (with some coefficients losing their significance, probably due to the importance of the Great Depression in shaping fiscal policy during the inter-war years). The post-WWII period displays mostly negative and significant coefficients, in line with the rise of civilian spending as the cornerstone of public finances.

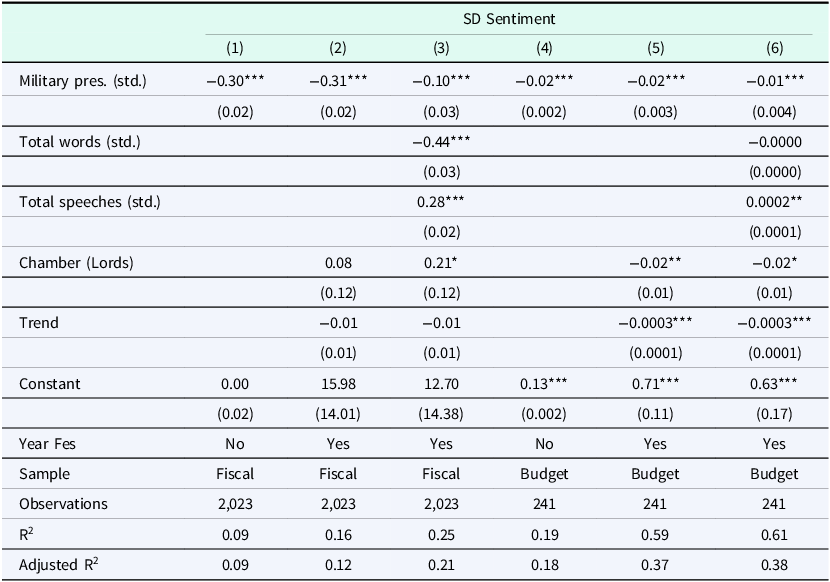

Results: military presence and contestation around taxation

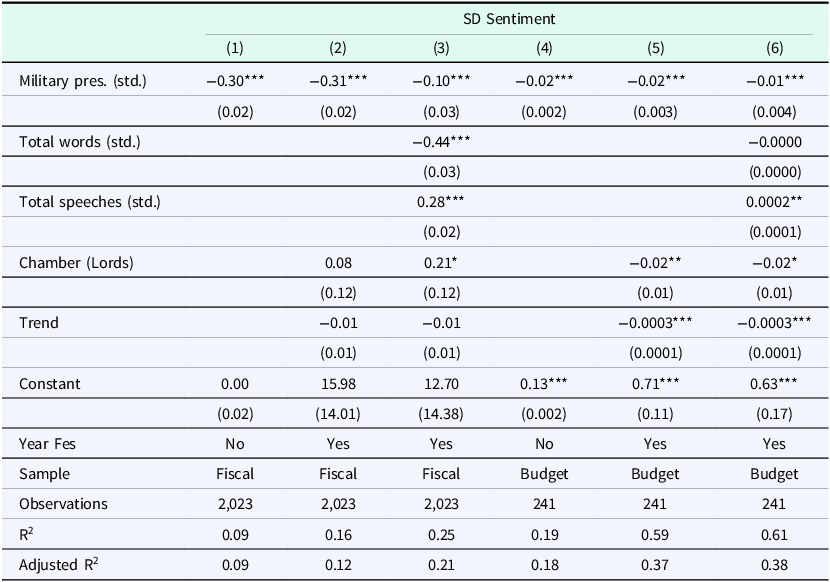

The second hypothesis asserts that military pressures should be associated with lower contestation around fiscal policymaking. In the models presented in Table 2, we follow a similar model specification as in Equation 1. This time, the dependent variable is a measure of contestation calculated as the standard deviation of the sentiment score among all speeches in a debate. The main independent variable is our measure of military presence. In order to identify parliamentary debates devoted to fiscal issues, Models 1 to 3 restrict the sample to debates in the top decile of the fiscal salience distribution. Models 4 to 6 focus instead on budget debates (i.e., debates that included the following expressions in the title: ‘Budget’, ‘Finance Bill’, or ‘Ways and Means’).

Table 2. Military presence and fiscal contestation

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01; Robust standard errors reported.

Models 1 and 4 display the bivariate correlations between military presence and contestation. Models 2 and 5 add year fixed effects and control for the chamber and a year trend. Models 3 and 6 include additional controls to account for the length of the debate based on the number of words and speeches. The continuous variables are standardised (except for the trend).

All models show that fiscal debates in which military issues were present tended to be less confrontational. According to Model 2, an increase of one standard deviation in military presence is associated with a decrease of almost a third of a standard deviation in contestation in fiscal debates. While these results do not necessarily imply that the presence of military pressures made collective action easier, a diminished level of rhetorical conflict likely reflected favourable conditions to coordinate efforts.

Robustness checks

In Appendix E, we reproduce Table 2 for shorter (at least 5 speeches) and longer (at least 20 speeches) debates (Table E1), as well as for debates using different thresholds (top 5% and top 25% in fiscal salience) to identify fiscal debates (Table E2). Our results hold. Table E3 presents different analyses of partisan dynamics. It shows that the relationship between military presence and lower fiscal contestation is not driven by a particular party dominating those debates. Those analyses also indicate that the presence of military issues is not associated with smaller differences between parties but rather with overall smaller differences among MPs, and especially smaller differences among Conservatives. Table E4 presents models with standard errors clustered by year and multi-level models, with debates nested by year or by Parliament and including time-varying controls related to suffrage expansions and war. Table E5 regresses our accumulated military presence variables on fiscal contestation, and results hold only when considering the previous 3 debates. Once again, this points towards short-term effects after MPs raise military issues. Table E6 turns to intense wars (wars with more than 10,000 battle-deaths) as the main independent variable. Again, we find that lower contestation was not associated with whether there was an active conflict at the time of the debate or not, but with actual references to military issues in the discussion. Tables E7 and E8 present placebo tests looking at contestation in debates about education and criminal justice. We find negative coefficients for military presence, but they tend to be much smaller than in the case of fiscal policy and are not robust to different model specifications. Tables E9 to E11 explore different strategies to account for debate length, since it may mechanically affect the results, as our measures of issue salience and presence include the number of words or speeches in the denominator. Most of the models yield results similar to those reported in Table 2, with the exception of a model where we control for debate length using the log of total words.

Appendix G reproduces our analyses using the KeyATM to identify fiscal debates, and the results hold. Appendix H extends the analysis for the post-1914 period.

Results: types of taxation

The previous sections showed that, during the long 19th century, the presence of military issues was associated with higher salience of fiscal issues and lower levels of contestation in debates about taxation. We now proceed inductively to identify what kinds of fiscal reform were discussed in the context of military pressures at the time.

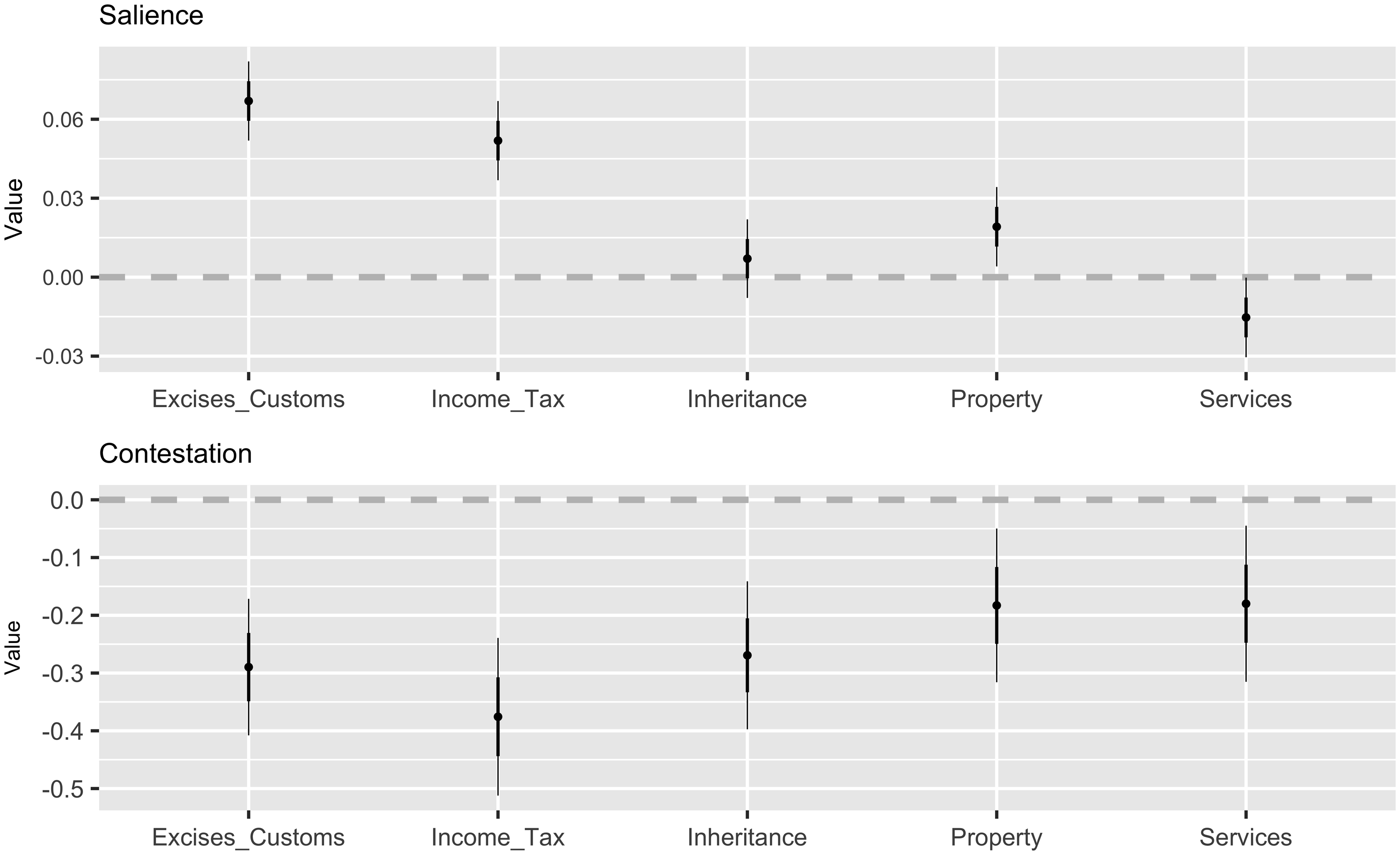

We begin by examining the relationship between military presence and the salience and contestation around specific taxes on income, inheritance, property, government services (e.g., stamp tax), and excises and customs duties. The top panel in Figure 3 presents the coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for military presence from separate analyses of the salience of each type of tax. These variables are defined as the share of keywords related to each form of taxation over the total number of words in a debate. Income taxes, excises and customs, and taxes on property show positive and statistically significant coefficients.

The lower panel does the same, but focusing on contestation around each type of taxation as the dependent variable. We limit the samples to debates in the top 2% of the salience distribution for each type of taxation to ensure that we focus on debates in which these types of taxes were discussed at length (but the results hold when using alternative thresholds as shown in Tables F3 and F4). Military presence is associated with lower contestation in discussions around all forms of taxation, and this relationship is particularly pronounced for the income tax.

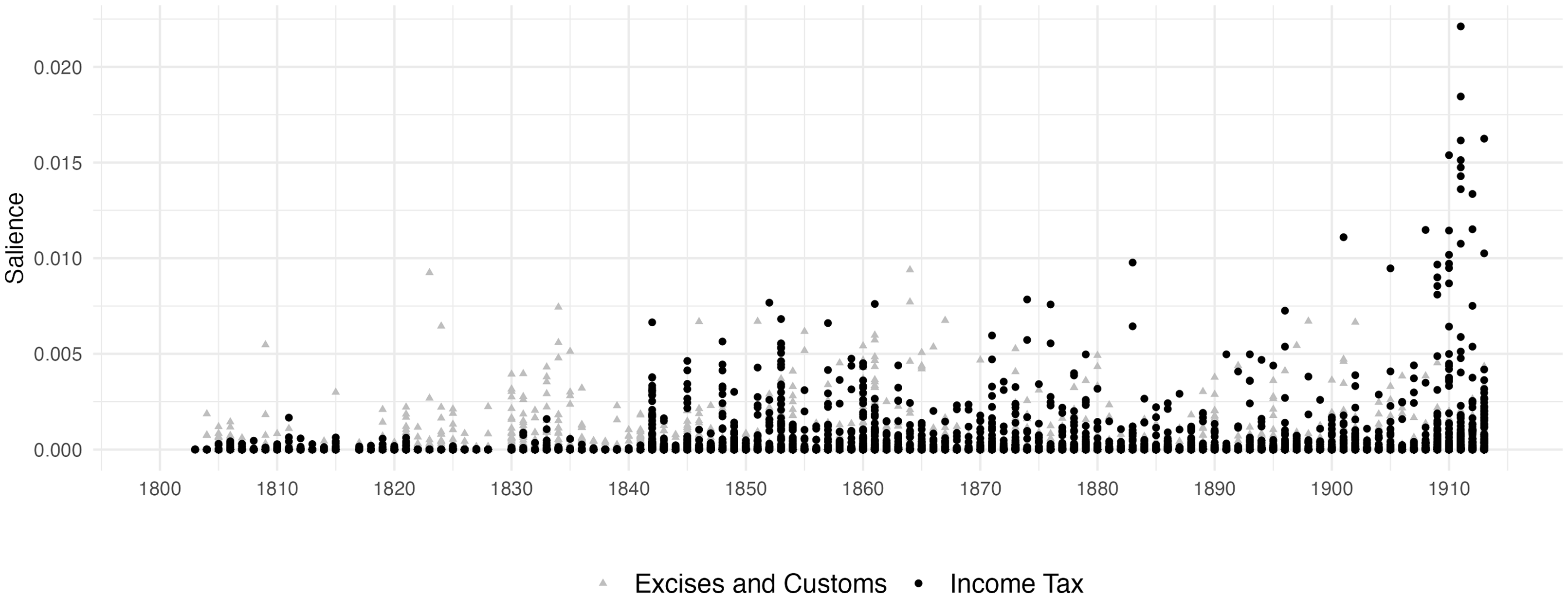

Whereas taxes on economic activities are older fiscal instruments that are commonly associated with lower levels of fiscal capacity, and taxes on property represented only a small share of total tax revenues throughout the century, taxes on income are generally seen as the paradigmatic modern tax. Taxing income requires extensive informational and administrative resources to keep track of the economic activities of a broad tax base, compared to excises and customs duties that can be more easily collected at key points (Hau et al., Reference Hau, Peres-Cajías and Soifer2023; Lieberman, Reference Lieberman2002; Rogers and Weller, Reference Rogers and Weller2014). As Figure 4 shows, income taxation became increasingly salient during this period, while the salience of excises and customs peaked only during the first half of the century. Hence, hereafter, we focus on the role that military pressures played specifically in debates about income taxation and, as a result, in the modernisation of the British tax system. We pay special attention to the extent to which military pressures were related by MPs to the adoption, preservation or expansion of income taxation, as defined in our third hypothesis.

Figure 4. Salience of income taxes (black dots) versus excises and customs (grey dots) (1803–1913).

Results: military pressures and income tax debates

First introduced in 1799, the personal income tax was repealed on March 18, 1816, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The tax commissioners were ordered that all the documents pertaining to the tax should ‘be cut into small pieces and conveyed to a paper manufactory, so that no trace of the hated tax would remain’ (Sabine, Reference Sabine1966:46).

The tax was reintroduced in 1842 during peacetime to redress the deficit caused by the reduction of trade duties (Daunton, Reference Daunton2002:168). It was established as a temporary measure for a three-year period, and it was renewed under similar conditions in 1845 and 1848. Military concerns were not dominant at the time of its introduction (although they entered the discussion around the renewal of the income tax in 1848). However, the outbreak of the Crimean War tied the fate of the income tax to the fiscal needs posed by military pressures. In 1853, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, William Gladstone, proposed to extend the income tax for seven years and to gradually reduce the tax rate over that period so that it could be seamlessly repealed in 1860 (Hansard, 1853:col.454). Even though the war in Crimea had not yet started, military issues were already very much present: 35% of speeches mentioned military issues, while the mean across all debates that year was 13%. And despite the Chancellor’s controversial proposal, the level of contestation was lower (0.09) than the average for that year (0.14). A year later, the mounting costs of the war forced Gladstone to double income tax rates and to further increase them in 1855 (Daunton, Reference Daunton2002:168), pushing income tax rates to their highest level until World War I (Comstock, Reference Comstock1920:489) and shattering his plans to abolish the tax at the end of the decade.

While it was widely expected that the income tax would be repealed in a matter of years, the parliamentary record shows that military pressures were a key argument voiced against attempts by both Liberals and Conservatives to repeal the tax. For instance, on February 23, 1857, Conservative MP Benjamin Disraeli introduced a motion to prepare the budget for the repeal of the tax by 1860. MPs from all parties argued against any extension of the income tax past that date, while, nonetheless, acknowledging the important role that it had played during the war (Hansard, 1857a:col. 1069). Two weeks later, on March 9, Disraeli back-pedalled on his proposal, as the military campaigns of the Second Opium War began to intensify. Disraeli opened the debate, stating that he would not oppose the Income Tax Bill: ‘We are now at war with China […] Under these circumstances I no longer feel justified in opposing this Bill, nor, indeed, in supporting any Motion which can have the effect of reducing the resources which are at the disposal of the Government’ (Hansard, 1857b:col. 2056). These were two of the most prominent discussions of the income tax in 1857. The presence of military issues in both debates was very high (over 70% of speeches mentioned military issues), whereas the average for all debates was 20% that year. And again, despite the striking shift in Disraeli’s policy position, the level of contestation (0.13) was slightly lower than the year’s average (0.14).

The military expenses from the Crimean War and the outbreak of the Second Opium War came up when attempts to abolish the income tax were once again pushed in Parliament in the 1860s, as it was proving crucial to reduce the fiscal deficit generated by the unexpected increases in military expenditures (Sabine, Reference Sabine1972:112).Footnote 3 On February 10, 1860, Gladstone, once more as Chancellor of the Exchequer, asked Parliament to renew the income tax for another year, with the purpose of putting the British purse back on a solid footing without having to increase trade duties (Hansard, 1860). The country had reached a small surplus of £65,000, but this was less than Gladstone had expected in 1853 – when he presented the plan to gradually eliminate the income tax – due to the unforeseen costs of the campaigns against Russia and China (Hansard, 1860). The debate resumed in four sessions the week after (from 20 to 24 February), in which a motion not to increase the income tax was discussed and voted against. The level of contestation was systematically lower than the annual average (as low as 0.05 on 23 February), while the presence of military issues soared (with a peak of 85% on that same day). Gladstone’s appeal gained strong support in Parliament. The income tax continued to be renewed every year during the 1860s (albeit at lower rates), even though it was still viewed by members of both parties –most prominently by Gladstone himself – as a temporary tax to be used only in exceptional circumstances (Seligman, Reference Seligman1911:166).

A crucial point about the income tax during this period was its usefulness to quickly raise revenues in the face of war. Often referring to the experiences of the Napoleonic Wars and the War of Crimea, MPs repeatedly described the income tax as a military asset. For example, in the debates around the Ways and Means Committee of 1871, Disraeli opposed increases in income tax rates while nonetheless acknowledging its military usefulness:

‘The income tax is the most important of our fiscal resources; it is imposed with the greatest ease; and it produces, when necessary, a sum which it is difficult, unless we are acquainted with the facts, to believe. It has been looked upon in old days as peculiarly a war tax, and wisely. (…) The fact that we can by a single tax, without distressing the community, on a great exigency produce 20 million or 25 million sterling —a sum which the most powerful states, were they engaged in war, would have to beg for at the different Exchanges and money markets of Europe— places this country at an immense advantage, gives us a position of power difficult to describe, and a line of defence scarcely less important than our Fleets and Armies’ (Hansard, 1871:col. 970).

The experiences of Crimea and the rise of Germany as a European power also led to major military reforms in the late 1860s and early 1870s. Notable amongst these reforms was the professionalisation of the army through the abolition of purchase of commissions and promotions in 1871 (Erickson, Reference Erickson1959:69). Debates on the Army Bill took place between March and June 1871 and thus occurred in parallel to the negotiation of the budget for that year. Consequently, the discussion of the budget repeatedly returned to the issue of how costly it would be to compensate the officers who would now be unable to sell upon retirement the positions they had purchased (see, for example, Hansard, 1871:cols. 1944–1950, when military pressures were present in most speeches and discursive contestation was as low as 0.09, compared to an annual average of 0.14). In the end, Parliament approved an increase in the income tax rate from 4d to 6d in the pound to support those expenditures.

The repeal of the income tax became a real possibility for one last time in the general election of 1874, when both Gladstone and Disraeli campaigned on the promise to finally get rid of it (Seligman, Reference Seligman1911:172). The British press even bullishly predicted that ‘whoever is Chancellor when the budget is produced, the income tax will be abolished’ (Sabine, Reference Sabine1973:182). However, as the Conservatives took power after the elections, the general view among MPs towards the tax had changed, and it was widely seen as both a fiscal and a military asset (Seligman, Reference Seligman1911:172–176). Echoing a common argument that had been raised in the past by both Gladstone and Disraeli, among others, Liberal MP Samuel Laing opposed his own party leader’s proposal, stating that:

‘It was impolitic to part with the Income Tax for another reason [besides its contribution to that year’s revenue] —it was important, with reference to our negotiations with foreign countries, that they should know that by raising that tax of 3d. or 4d. in the pound, without disturbing trade, without a sensible strain upon ourselves, we could raise a larger sum to carry on war in case of need than other countries could by straining their credit to the utmost with a succession of onerous loans. Well, to retain this important element, we must continue that machinery by which the tax was raised during the times of peace as well as war, for if we discontinued it, foreign nations knew that we could not go to war without a great effort or reviving an unpopular tax’ (Hansard, 1874:241).

In sum, from the late 1840s to the 1870s, external military pressures were repeatedly voiced to justify the renewal of the personal income tax. The reliance on income taxation to finance military expenditures gradually built a consensus, shared among Liberal and Conservative MPs, around the effectiveness of the income tax as both a powerful fiscal instrument and, especially, as a daunting military asset that enabled the British State to raise resources for war faster and more effectively than any of its rivals. Military concerns continued to be part of income tax debates during the following decades, particularly at the turn of the century, with the military campaigns in Africa, but by then, debates increasingly centred on other aspects of the tax, such as the level of progressivity and differentiation.

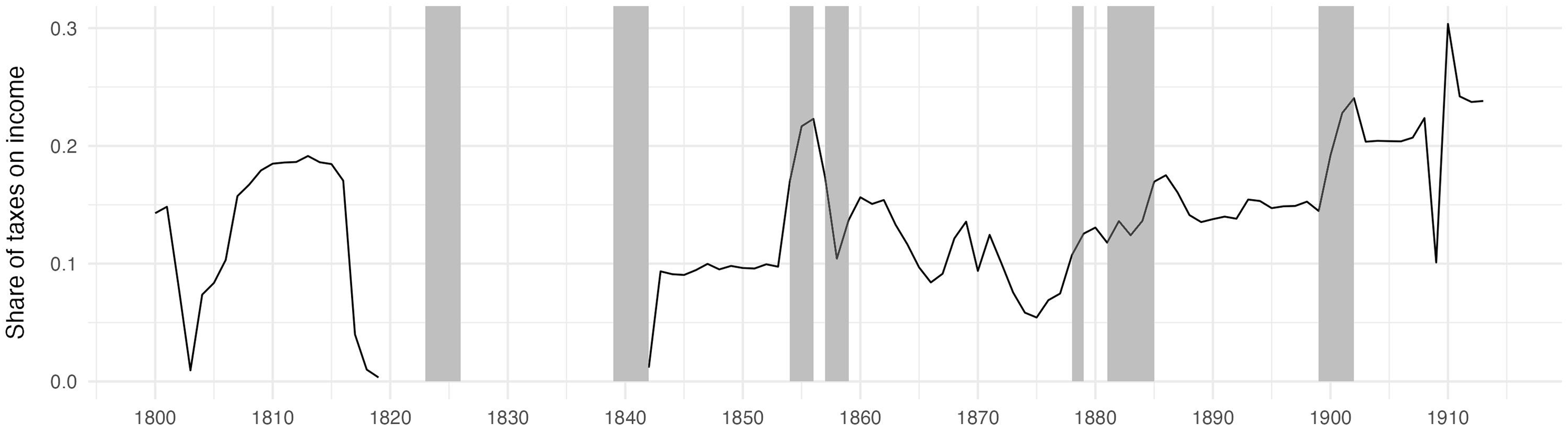

While we leave the analysis of the budgetary impact of specific parliamentary debates for further research, disaggregated tax revenue data presented in Figure 5 shows that the periods of sustained attention to income taxation in which military concerns were present (the early 1850s and 1860s, the 1870s, and the turn of the century, as discussed above and shown in Figures F1 and G3) correspond to periods of increasing income tax revenues. Indeed, a report presented to the Royal Statistical Society in 1887 showed that increases in income tax rates between 1857 and 1886 were driven in almost every instance by military concerns (e.g., in 1854, 1855, 1860, 1867, 1868, 1871, 1876, and 1878) (see Appendix I). During those years, successive attempts to dispense with the tax were unsuccessful, and the share of income taxation remained around 10–15% until the end of the century.

Figure 5. Share of income taxes over total public revenues, 1800–1913. Notes and sources: Shaded columns account for wartimes with more than 10,000 battle deaths. Public revenue data from Thomas and Dimsdale (Reference Thomas and Dimsdale2017); wartimes from Sarkees and Wayman (Reference Sarkees and Wayman2010).

Conclusion

During World War I, British public revenues jumped from representing 8.7% of GDP in 1914 to 22% of GDP in 1919. For this dramatic explosion in public revenues to occur, the fiscal capacity to raise them had to be already in place prior to the war (Cappella Zielinski, Reference Cappella Zielinski2016; Lee and Paine, Reference Lee and Paine2023). Indeed, in 1917, Oliver M. W. Sprague argued in an article for the American Economic Review that ‘a war policy based on taxation presupposes that a country must have established and in operation highly developed income-tax machinery in time of peace, so that it may have at its disposal full information regarding the income of its citizens’ (Sprague, Reference Sprague1917:211).

This article focuses on the policymaking process to study incremental investments in fiscal capacity, such as those needed to establish and maintain the fiscal machinery that Sprague talked about in the midst of World War I. By applying computational text analysis to British legislative debates from 1803 to 1913, we provide new evidence supporting bellicist theories of state capacity, as we show that military and fiscal issues were tightly woven together in British parliamentary debates during the long 19th century. We find, first, that the presence of military concerns was associated with higher salience of fiscal issues in Parliament. Second, fiscal debates in which military issues were present tended to be less contentious. Unfortunately, our textual analysis alone does not allow us to make causal claims about whether those levels of salience and contestation in fiscal debates were associated with actual policy changes. Therefore, we rely on qualitative analyses of key debates to identify how military issues may have contributed to concrete policy outcomes. Those analyses show that, between the 1850s and the 1880s, external military pressures were recurrently evoked to support the renewal of the personal income tax until it became a permanent part of the fiscal system.

These findings help explain the contradictory results in the literature regarding the short- and long-term effects of 19th-century military conflicts on British fiscal development. While war and geopolitical threats did not lead to higher levels of taxation in the 19th century, military pressures nonetheless were present when attempts to weaken the existing fiscal capacity of the British state were discussed. In this way, 19th-century military pressures were an important part of parliamentary debates that contributed to gear the fiscal system towards more stable and efficient forms of taxation, making possible the unprecedented expansion of public revenues during the 20th century.

Even though the UK is an exceptional case given its position as a global power, other states likely faced similar processes at the time. As efforts to digitalise historical legislative corpora continue to grow, future research may seek to explain under what conditions external military pressures lead to different kinds of investments in fiscal capacity, such as the adoption of modern taxes, the expansion of the fiscal bureaucracy, improvements in legibility, or, as in the British case, the consolidation of existing fiscal instruments. An important limitation of our study is that we only focus on legislators. A comprehensive explanation of the development of fiscal capacity will require to investigate how fiscal bureaucrats also reacted to external military pressures. Finally, future studies may also apply text-as-data techniques to elucidate when external military threats changed legislators revealed preferences regarding state-building reforms and when legislators instead referred to external military pressures as a rhetorical strategy to advocate for their prior policy positions. Rather than offering definitive answers to these questions, our hope with this article has been to offer some initial steps towards the study of the piecemeal processes of historical state-building.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137425100349

Funding

Authors listed in alphabetical order. This paper was made possible through funding from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, grant no. M14-0087:1, the Swedish Research Council, grant no. 2021-02907, and the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 752163. The authors thank Dylan Pashley for excellent research assistance. The authors also acknowledge the support of the Humanities Lab at Lund University.