Introduction

The past year (2024–25) has been a dynamic one for archaeology in Greece, with excavations and surveys producing important evidence for the study of sites, landscapes, and settlement patterns. New fieldwork campaigns across the country offered fresh insights, while long-standing projects added new dimensions to well-known sites. Rescue excavations also brought to light striking finds that highlight the richness of the archaeological record. The following summary highlights key developments of the past year, reflecting the breadth and vitality of current research in Greece (Map 3.1).

East Macedonia and Thrace

Excavations at Dikili Tash (ID 20629) continued in 2024. The project is a synergasia between the Archaeological Society at Athens and the École française d’Athènes (EFA). Led by Haïdo Koukouli-Chryssanthaki (Ephorate of Antiquities of Kavala), Dimitra Malamidou (Ephorate of Antiquities of Serres), Pascal Darcque (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), and Zoï Tsirtsoni (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), the focus this season was on the northern slope of the tell in Sector 9. Within this area, the team uncovered a greyish-brown sediment containing wood and charred plant remains. This was interpreted as part of a levelling layer, which extended across 75% of the southern portion of the sector. Beneath this, three layers of superimposed plaster were found (Fig. 3.1).

Fig. 3.1. Dikili Tash: Three layers of plaster were found superimposed below the levelling layer © ASA/EFA.

Map. 3.1. 1. Dikili Tash; 2. Molyvoti; 3. Samothrace; 4. Ancient Pergamos; 5. Abdera; 6. Doriskos; 7. Philippi; 8. Lake Plastira; 9. Magoula Plataniotiki; 10. Palamas Archaeological Project; 11. CAPS; 12. Agia Marina Pyrgos; 13. Mitrou; 14. Eleon; 15. Delphi Marmaria; 16. Melitaia; 17. Kephissos Valley; 18. Boeotia Project; 19. Artemision, Amarynthos; 20. Eretria-Amarynthos survey; 21. Ancient Port of Eretria; 22. Eretria; 23. Oreoi; 24. Hinterland of Medieval Chalkida; 25. Hellanion Oros; 26. Ambelaki, Salamis; 27. Kerameikos; 28. Vasilissis Olgas Avenue; 29. Erechtheion and N. Kallisperi streets; 30. Aegina Harbour City; 31. Athenian Agora; 32. Pylos; 33. Kleidi-Samiko; 34. Olympia; 35. Ancient Rypes; 36. Tenea; 37. Epidaurus; 38. Asine and Tolo; 39. Lechaion; 40. Isthmia (Michigan); 41. Isthmia (Chicago); 42. Corinth; 43. Heraion, Samos; 44. Despotiko; 45. Despotiko Tsimintiri; 46. Floga, Parikia; 47. Antikythera; 48. Kea; 49. Delos; 50. Rheneia; 51. Megalos Peristeres Cave; 52. Sissi; 53. Papoura Hill; 54. Gournia; 55. Archanes; 56. Azoria; 57. Itanos; 58. Dreros; 59. Kotroni, Lakithra; 60. Ancient Theatre, Lefkada.

To the north, a possible ditch was used as a Late Neolithic II (4800–4200 BC) dump, which was rich in fragmented materials, including ceramics, figurines, and tools. Evidence of Neolithic metalworking was also found, with raw materials, crucibles, production waste, and gold and copper artefacts. In addition, the pits that were filled in the Early Bronze Age (2800–2500 BC) showed traces of a wall construction technique unprecedented in northern Greece. This involved a framework comprising wood, earth plaster, and stones, with two pits also displaying wattle-and-daub construction (Fig. 3.2) and one possibly incorporating vault supports. Their precise construction dates, however, remain uncertain.

Fig. 3.2. Dikili Tash: Indentations in building earth suggest the presence of wattle and daub, part of a building strategy previously unknown in northern Greece © ASA/EFA.

In summer 2024, the Molyvoti, Thrace, Archaeological Project, which explores the Archaic to Classical trading port, continued its analysis of material recovered during previous excavation and survey campaigns. This is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Rhodope – led by Domna Terzopoulou and Marina Tasaklaki – and the American School of Classical Studies Athens (ASCSA) – represented by Nathan Arrington of Princeton University. As reported by Arrington, the focus this season was on the House of Hermes and the extra-mural sanctuary. Preliminary analysis of the material indicates that the House of Hermes dates to a similar period within the fourth century BC as the House of the Gorgon (ID 6182; see Arrington et al. Reference Arrington, Terzopoulou, Tasaklaki and Tartaron2025); however, due to different formation processes, fewer artefacts remain. The distinct architectural features suggest the finds will reveal different aspects of domestic and mercantile life, providing a valuable contrast to the House of the Gorgon.

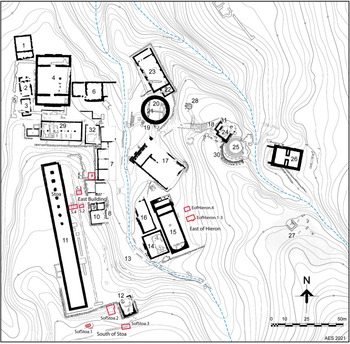

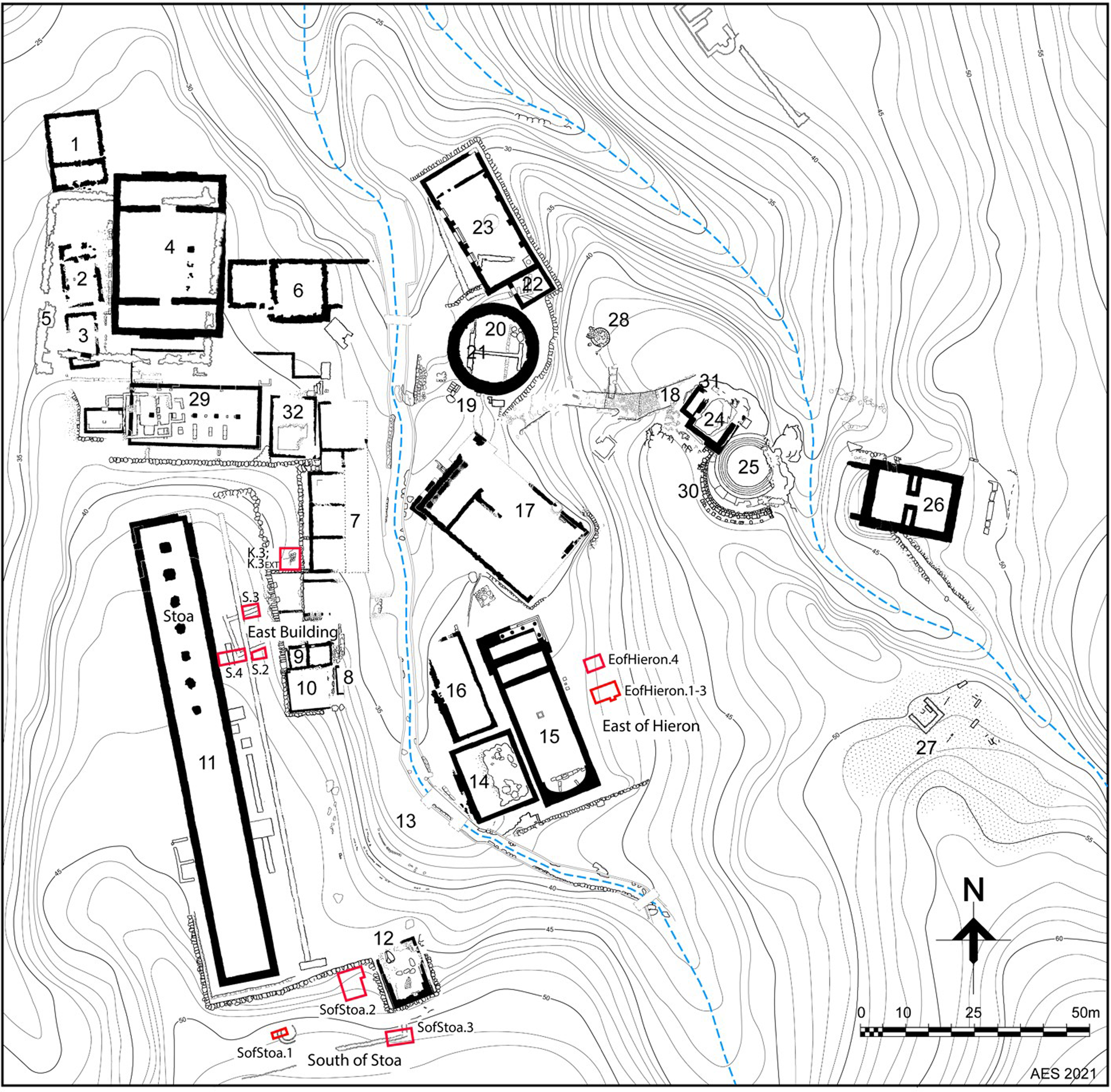

From June to August 2024, the American excavations on Samothrace (ID 20650) conducted their fifth field season, under the supervision of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Evros, and carried out under the auspices of the ASCSA. Directed by Bonna Westcoat (ASCSA/Emory University), the season included excavation, field survey, architectural research, and conservation in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, as well as work on the city wall between Tower A and the West Gate (Fig. 3.3).

Fig. 3.3. Plan of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods at Samothrace with the location of the 2024 trenches © American Excavations Samothrace.

In the Sanctuary, excavations east of the Hieron revealed different deposits: one, rich in marble chips, likely connected to the Hieron’s construction at the end of the fourth century BC; the other, containing architectural plaster mouldings, dated between the second century BC and the first century AD. In Room K, research confirmed an earlier hypothesis that the existing staircase was built on rubble dating to the Late Hellenistic or Early Imperial period; however, the presence of limestone ashlar blocks suggests an earlier function, meaning the space was not always intended a stairwell (Fig. 3.4).

Fig. 3.4. Samothrace: Photogrammetric model of Space K © American Excavations Samothrace.

On the Stoa Plateau, three trenches were opened near the East Building; in two of these, the foundations were found to rest directly on natural soil, with associated ceramics dating to the fourth century BC. A thick deposit of black earth inside the building yielded fineware ceramics, a carved ivory inlay, mosaic and bone fragments, and yellow plaster. To the south of the Stoa, Roman-period occupation was identified from ceramic evidence. While a reopened trench (SGG.SStoa.2) aimed to trace the ancient water system, no connecting pipes were found. The third trench (SGG.SStoa.3) helped date a structure near the Victory Monument to the late third century BC, with glass and Byzantine pottery indicating continued activity.

At the West Gate, collapsed masonry and over 48 stelai cuttings were uncovered, confirming the gate’s role as a major point of communication between the city and the Sanctuary. The geospatial survey continued to produce data using photogrammetry, unmanned aerial vehicle photography and video, and global navigation satellite system.

In June 2024, the first field season of the Ancient Pergamos Project (ID 20644) took place in modern Moustheni, near Kavala. This is a five-year synergasia between Stavroula Dadaki of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Kavala, alongside Georgia Galani from the Swedish Institute at Athens (SIA), and Patrik Klingborg from Uppsala University. The first season included survey, excavation, and documentation of the fortifications, designed to clarify the chronological phases (see Klingborg et al. Reference Klingborg, Galani, Blid, Dadaki and Malama2024).

The excavations focused on the inner side of the southern fortification wall, uncovering multiple occupation phases with architectural features identified from the Byzantine, Late Roman, and Archaic periods (Fig. 3.5). Additional fill layers were found, which require further study. Over 5,000 ceramic sherds, 11 loom weights, glass fragments, metallurgical slag, bones, and metal objects were recovered, indicating continuous occupation from the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1500–1050 BC) to Late Roman times (AD 400–600) and possibly the Byzantine period. Moreover, 57 sediment samples were collected for future pollen analysis to better understand the site’s ancient environment. Drone photography has also enhanced site mapping by revealing previously unseen features.

Fig. 3.5. Ancient Pergamos: Sections from new excavations, showing successive phases from Late Roman times onward; to the right, the inner face of the fortification wall. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Kavala / SIA.

For the survey, RTK-GPS (real-time kinematic GPS) was used, with finds recorded from 20 grid points. The ceramic finds were found to be sparse and heavily worn, casting doubt on earlier, non-systematic chronological assessment.

June also saw a survey campaign undertaken on the Insula of Houses in ancient Abdera (ID 20651) as part of the Abdera Urban Plan Project, a synergasia run by Maria Chrysafi (Ephorate of Antiquities of Xanthe), Maria Papaioannou (University of New Brunswick), and Peter Dare (University of New Brunswick). Using multiple geophysical methods – including ground-penetrating radar (GPR), magnetometry, electrical resistivity tomography, and laser scanning – surveys reached depths of up to 2m, with drone photography complementing the data collection. In total 7,200m2 were scanned using GPR, and 6,900m2 with magnetic gradiometry.

The results revealed well-defined remains of houses, streets, sewers, and neighbouring insulae, or housing blocks, to the west and south. A large house with a peristyle courtyard dominated the western section, surrounded by walls from adjacent houses, some uncovered in earlier excavations (Fig. 3.6). Hellenistic-era sewers, at a depth of about one metre, were detected beneath the streets on both the western and eastern sides of the insula, resembling those near the House of the Dolphins. The sudden disappearance of these drains (near the insula’s corners) suggests Roman-era architectural encroachments onto the roads – a phenomenon previously noted elsewhere in Abdera.

Fig. 3.6. Abdera: Ground Penetrating Radar undertaken in 2024 revealed the remains of a Roman peristyle house. Archaeological Site of Abdera © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Xanthi.

Geological research continued in 2024 at Doriskos and the lower Hebrus (ID 20680). This project is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Rhodope, with Chrysa Karadima, Kiel University, with Wolfgang Rabbel and Helmut Brückner, and the EFA, with Anca Dan from the National Centre for Scientific Research at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris (CNRS/ENS-PSL). With the agreement of the Greek army, the project conducted a survey between 26 September and 5 October. The campaign combined geomagnetic and seismic prospecting with sediment core sampling, designed to investigate the city’s relationship with the Hebrus delta, its harbour, and the Via Egnatia.

The magnetic survey around the Doriskos promontory revealed anomalies that confirmed the 2023 results (Fig. 3.7). These include a horseshoe-shaped structure east of the acropolis, possible pits or stone features, traces of an urban extension northwest of the acropolis, and the probable course of the Via Egnatia southwest of the acropolis. The seismic survey identified soft lagoon-type sediments over much of the area, interrupted by a high-velocity feature interpreted as a 1km–wide dam, confirmed through topographic mapping. C14 dating indicates the existence of the dam in Antiquity, suggesting it protected a harbour basin. Six sediment cores were also extracted to reconstruct the alluvial plain and delta’s evolution, linking natural processes with human activity.

Fig. 3.7. Doriskos: Map with the magnetic survey of the acropolis of Doriskos © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Rhodope / EFA.

Rescue work has been undertaken in Philippi, preparing for the installation of a fire safety network. The infrastructure project – which is due for completion in Autumn 2025 – has unearthed significant archaeological findings. Stavroula Dadaki (Ephorate of Antiquities of Kavala-Thasos) has described locating structures dating between the eleventh and ninth centuries BC. During the rescue process, a large public building with an in-built statue of a young male figure was discovered (Fig. 3.8), along with public baths with Roman and early Christian phases, as well as workshops and houses.

Fig. 3.8. Philippi: A sculpture of a young male was discovered within a wall of a public building during the ongoing works to install a fire safety and water distribution network © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Kavala.

Thessaly and Western Greece

2024 saw the third excavation campaign of the Neolithic settlement on the western shores of Lake Plastiras (Votanikos Kipos; ID 19678): a project undertaken by the Archaeological Museum of Karditsa, directed by Aikaterini Kyparissi-Apostolika and Orestis Apostolikas of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Karditsa. The site is situated at an altitude of 800m and continues to reveal important findings from the transitional phase between the end of the Early Neolithic and the beginning of the Middle Neolithic (5999–5845 BC, per C14 dating).

This year, the excavations reached the main occupation layer approximately 1m below the surface. Finds confirm that the settlement had abundant raw materials – such as local clay and several types of flint, along with psammite (sandstone) from nearby bedrock – which were used to produce artefacts such as polished stone tools and millstones. The ceramics are predominantly monochrome and appear to also be locally produced, as demonstrated by the discovery of two pottery kilns with spherical vessels preserved in their firing positions (Fig. 3.9), and more kilns are expected to be found in future excavations. Decorative knobs found on pottery might also indicate cultural links with contemporaneous Thessalian plain sites.

Fig. 3.9. Lake Plastira: Part of a kiln with whole vessels © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Karditsa.

During excavations, a reddish layer was identified over a large area bordered by a brick wall, in which hearths, postholes, and domestic debris were revealed. Among the movable finds was a rare intact model of a kiln (or house), along with anthropomorphic figurines. One of these is 10.5cm in length and might have been 17cm when complete (Fig. 3.10). This high-altitude Neolithic settlement displays characteristics distinct from lowland counterparts, offering new insights into early mountain habitation and ceramic production in prehistoric Greece.

Fig. 3.10. Lake Plastira: Neolithic figurine of 10.5 cm in height, with an estimated total height of 16-17 cm © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Karditsa.

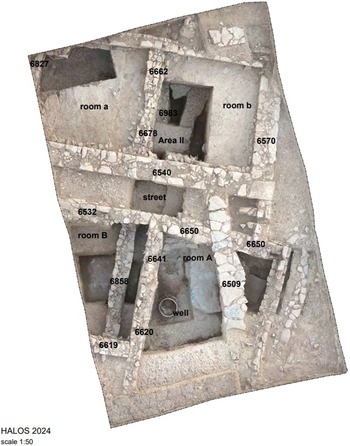

The Netherlands Institute at Athens (NIA) reports on the four-week excavation in 2024 at Magoula Plataniotiki (ID 20699). This project is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia (Vasso Rondiri) and the University of Amsterdam (Vladimir Stissi), with Yannis Lolos of the University of Thessaly as associate director. The focus this season was in Trench 6, on the eastern edge of Magoula – deemed of interest through earlier geophysical studies. Excavations revealed complex stratigraphy, including walls, roads, and floor levels, with evidence of successive use and rebuilding after possible seismic activity. Finds include Attic and Corinthian pottery, terracotta figurines, and spindle whorls, mostly dating from the sixth century BC with some from the fifth. A tortoise shell with iron nails, possibly forming a lyre, was found beneath Room A, which may have been from an earlier phase (Fig. 3.11).

Fig. 3.11. Magoula Plataniotiki, Magnesia: a tortoise shell was found in Room A, possibly part of a lyre © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia / NIA / University of Thessaly.

Room B revealed an earlier construction phase of Wall 6858, which was used as a foundation for the later phase. A previously unknown wall (6983), built of smaller stones and following a different orientation, also emerged in the northwestern part of the trench, which is understood to correspond to a different phase (Fig. 3.12). It was suggested that the presence of Archaic, cult-related material across the site indicates the site might be associated with a sanctuary or feasting area, akin to that of Demeter and Kore’s in Corinth. Zooarchaeological and archaeobotanical samples were collected, with analyses scheduled for 2025.

Fig. 3.12. Magoula Plataniotiki, Magnesia: overview of the excavations at the conclusion of the 2024 season © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia / NIA / University of Thessaly.

Excavations continued in late summer 2024 at Palamas, near Stroggylovouni Vlochou (ID 20643). This project is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Karditsa, under Maria Vaïopoulou and Fotini Tsiouka, and the SIA, with Robin Rönnlund (University of Gothenburg). Work continued in Trench 3 in the Patoma region, focusing on a stoa-like building with polygonal masonry and pottery from the third century BC, with the building showing traces of destruction in the second century BC. Trench 4 revealed architectural remains with ceramics dating to the Early Byzantine period, whereas the lower levels displayed substantial trapezoidal masonry, pottery, and coins from the third to fourth centuries AD. This forms the first stratified evidence for a Late Roman phase at Stroggylovouni. A drought in Thessaly exposed additional courses of the Classical–Hellenistic fortification wall, 2.5m below existing remains.

The project also undertook survey at the Titanio hilltop, 5km west of Vlochos. Finds confirmed Hellenistic activity, a possible Archaic shrine, and an Early Byzantine fortification wall, and a coin of Justinian I was also found in a test trench. At Makrya Magoula – traditionally identified with Homeric Arni – geophysics identified Late Bronze Age pottery, and the remains of Hellenistic architecture, including two large buildings with a courtyard. The project also surveyed nearby sites identified via satellite imagery, locating surface finds from the Middle Neolithic to Late Bronze Age, suggesting more extensive prehistoric habitation than previously known.

2024 also marked the fourth and final year of fieldwork for the Central Achaia Phthiotis Survey (CAPS; ID 20653). Run under the auspices of the Ephorate of Antiquities in Larissa, and co-directed by Sophia Karapanou (Ephorate of Antiquities in Larissa), the Canadian Institute in Greece (CIG), and Margriet Haagsma (University of Alberta), this year focused on the landscape around Kastro between the fourth and second centuries BC.

Between 8 July and 11 August, the pedestrian survey covered approximately 146 hectares across the regions around Paleochori and Platanos. Despite limited visibility – due to uneven terrain, overgrowth, and storm damage from Typhoon Daniel – the team recovered 10,881 pottery sherds (195kg) dating between the Classical and pre-Modern periods, with significant results from the Ottoman era found southeast of Platanos. There were also 10 metal items and two pieces of slag, but very few lithics. Architectural features were also identified: including tile graves of (probable) Hellenistic date; a possible Early Iron Age tholos tomb; an Ottoman ceramic water pipeline; a possible Hellenistic tile grave for a newborn (Fig. 3.13); and another Early Iron Age tholos near Kastro, adding to the 24 previously discovered.

Fig. 3.13. CAPS Feature 2024-F3: Possible Hellenistic tile grave, north of the Kastro at Kallithea © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa / CIG.

The team also confirmed nine new (probable) tholos tombs northeast of Platanos, with surrounding finds dating from the Early Iron Age. This raises the total number of tombs in the area to 12, with an additional five possible tombs recorded – suggesting this was an area of funerary significance within Thessaly (Fig. 3.14).

Fig. 3.14. CAPS: locations of probable (darker) and potential (lighter) tholos tombs on the south slope of the Narthakion range © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Larissa / CIG.

In addition, the CAPS project included geophysical surveys at Platanos Magoula and Kastraki, which entailed magnetic mapping on masonry and associated soil. At Kastraki, the investigations revealed numerous walls and rectangular structures, along with a large circular feature at a depth of 1.20m. This has been provisionally interpreted as a Mycenaean tholos tomb with a dromos and side chamber, but may have been in use into the Early Iron Age, based on surface findings. At Platanos Magoula, the magnetic mapping revealed curvilinear ditches suggesting complex water management in an Early Neolithic to Middle Neolithic settlement. Human remains from Tholos 14 – identified in 2023 (ID 19598) as possibly Mycenaean on the basis of the architecture – were also studied, identifying unburned adult remains and possibly cremated fragments, suggesting mixed burial practices, as found in Tholos 7.

Central Greece

Michael Lane (University of Maryland) reports on the 2024 KOCECOLA excavation at the Bronze Age settlement site of Aghia Marina Pyrgos in the Copais Basin (ID 20648). This is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia, with Alexandra Charami and Evi Tsota, and the ASCSA, represented by Lane. The project ran from 3 June to 14 July 2024, and focused on several new and pre-existing trenches across the site.

In the northern zone, Trenches 6 and 7 explored Middle to Late Bronze Age strata. In Trench 6, a Late Helladic (LH) IIIB stone channel, perhaps intended for drainage, was uncovered above an earlier infant necropolis, previously identified by the MYNEKO project in 2016–18 (Lane Reference Lane2023). A seated female figurine of a Cypriot type – possibly funerary – was found among layers containing obsidian blades, beads, and human and animal bones (Fig. 3.15).

Fig. 3.15. KOCECOLA, Agia Marina, Pyrgos: Seated figurine of a Cypriot style with pinched face. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia / ASCSA.

Trench 7, newly opened this season, confirmed the presence of a north–south wall separate to Wall A. In the south, Trench 8, also newly opened, uncovered sherds from storage vessels and monochrome skyphoi (drinking vessels), the latter tentatively dated to the Early Geometric period. Work continued in Trench 9, revealing a burnt destruction layer with sherds from the Early Geometric period. Excavation in the LH IIIB building also revealed an undecorated alabastron from the LH IIIA-B period and numerous mollusc shells (Hexaplex, Spondylus), indicating red and purple dye production and textile industry.

On the summit in Trench 11, excavation continued of a looted paved cist tomb with Early Helladic (EH) II material, including Urfirnis and ‘sauceboat’ sherds. A second, undisturbed burial was found below, with a skeleton neatly laid out and with fineware ceramics spanning Middle Helladic III to LH I (Fig. 3.16). Trench 13 was the first opened on the western slope; it contained a mass of smaller stones intersecting other architectural features. Finds including metal slag, a laterite hammerstone, and an LH IIIB2/C Early cup, suggest the presence of a workshop. Additionally, soil samples from Trenches 6, 9, and 11 were collected for radiocarbon and luminescence dating to clarify stratigraphic sequences.

Fig. 3.16. KOCECOLA, Agia Marina, Pyrgos: Fine grey burnished cups in Trench 11. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia / ASCSA.

Aleydis Van de Moortel (University of Tennessee) reported on the fifteenth study season of the Mitrou project (ID 20649). Running from 17 June to 27 July 2024, the team investigated Early Helladic pottery, metal jewellery, ceramic imports from Aegina (predominantly from Building H), and other categories of materials from the excavation seasons. Notably, fragments of textiles were discovered, and painted images on a jug (LP782-040-012), from a LH IIIB2 Late destruction dump over part of Building D, were identified as ships. These three ships have characteristics akin to those of the ‘Sea Peoples’, with one displaying a large emblem in the shape of a horned helmet.

The Eastern Boeotia Archaeological Project (ID 20652) conducted excavations at ancient Eleon from 13 May to 23 June 2024. This project is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia and the CIG, and is directed by Alexandra Charami (from the Ephorate), Brendan Burke, and Trevor Van Damme (University of Victoria), alongside Bryan Burns (Wellesley College).

Excavations in the lower town of Eleon continued from 2023 (ID 19599), focusing on an area 250m west of the acropolis (Fig. 3.17). The primary aim of the 2024 campaign was to date the construction of a lower town fortification system and to assess the quality of the geophysical survey data collected in 2022. The results of the season indicate that Eleon’s fortification wall was likely part of a unified circuit that included the monumental eastern polygonal wall. The fill between the 55–57cm-wide wall blocks in this section was mixed, with angular and rounded limestones and pebbles in clay packing differing from the more uniform fill seen in the southern trenches. This variation in construction styles aligns with Archaic-era practices (Fig. 3.18), where greater effort was taken on the acropolis.

Fig. 3.17. EBAP: Overview of the site showing the location of the trenches excavated east of the acropolis (2012-2018); west of the fenced area (2023); and in the Lower Town (2024) © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia / CIG.

Fig. 3.18. EBAP: Photogrammetric model of trenches LTE8d (at left) and E8b (right), showing changes in construction techniques © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia / CIG.

These findings suggest the fortification was a large-scale but quickly executed project. The construction appears to date to a period of Theban expansion in the late sixth century BC, possibly linked to regional power struggles, but it remains unclear whether the walls were built to resist or support Theban control. Continued excavation and ceramic analysis are needed to refine the dating and determine whether the wall’s destruction was due to warfare or natural causes.

Excavations were also undertaken in 2024 at Marmaria, Delphi (ID 20668), in the southeastern outskirts of the city. Directed by Sandrine Huber (University of Lille) and Didier Laroche (École Nationale Supérieure des Arts et Industries de Strasbourg), the project aimed to explore the terrace area of the site, advance understanding of the sanctuary’s topography and chronology, ascertain the earliest occupation, and gain clarity on the architectural development. On the terrace area, work focused on the Massalian Treasury, the Temple of Athena, and the Great Altar with nearby cult structures. Architectural studies also addressed Tholos SD 40 and the limestone building SD 43.

At the Massalian Treasury, excavation was undertaken in the western part of the pronaos (entrance hall) and inside the cella (chamber), revealing levelling fill above the foundations with sixth century BC ceramics. Below this was artefact-rich colluvium fill, understood to have accumulated from landslides. The foundation structure for the wall dividing the pronaos from the cella was also partially uncovered, with this layer yielding several metal objects dating to the second half of the sixth century BC. A retaining structure beneath the foundations, likely predating the monument, suggests early landscape management.

Work in the northern peristasis (colonnade) in the Temple of Athena continued, where the destruction layers from a probable landslide were investigated. Finds included architectural terracottas, charcoal, and metal artefacts. The mortar and pebble floor was cleaned and confirmed to date to the fifth/fourth century BC, with no artefacts earlier than the sixth century BC found below the temple. The ceramic material found in 2024 confirms the dating established in previous years: the destruction layer is from the Late Hellenistic/Imperial period with a chronological horizon ranging from the first century BC to the second century AD.

Excavation also clarified the sixth century BC origins of the Great Altar. Adjacent deposits, with ceramics and faunal remains, may relate to a possible altar of Ilithyia, near the altar of Hygieia. In addition, geomorphological study highlighted the terrace’s vulnerability to natural disasters such as landslides.

Excavations at the ancient city of Melitaia (ID 20640) were undertaken as a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Phthiotis and Eurytania (led by Konstantina Psarogianni) and the Finnish Institute in Athens (represented by Petra Pakkanen). Work continued from 2023 (ID 20639) in two trenches on the acropolis (A and C), where structural remains were uncovered (Fig. 3.19). In Trench A, the excavation of complex K2 unearthed some near-complete vases, including four goblets and a rounded unguentarium, along with a large (meat) fork and coins that dated the complex between the second century BC and the first half of the first century AD (Fig. 3.20).

Fig. 3.19. Melitaia: View of the two structures on the acropolis, excavated in 2024 © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Phthiotida and Evrytania / FIA.

Fig. 3.20. Melitaia: Ceramic vessels and a metal fork, which date the occupation of building K2 to between the 2nd and first half of the 1st centuries CE © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Phthiotida and Evrytania / FIA.

In Trench C, structure K1 (with inner dimensions 60 × 50cm) was found to date from the second century BC. While metal finds (iron and lead fragments), charred plant, and fossilized wood remains were found, very few diagnostic sherds were unearthed. Other finds from this trench included four pig jaws, deer antlers, and pyramidal and disc-shaped weights.

Katja Sporn reports on the 2024 season at the Kephissos Valley (ID 20646) for the Deutsche Archaeological Institute (DAI), which served as preparation for the forthcoming five-year plan for more extensive research. The goal of the project was to investigate anomalies in the landscape, identified via LIDAR and multispectral imagery, along with previously plotted archaeological sites. Using the recording system of QField and QGIS, the project’s database contains 245 sites. This year, eight possible Roman/Late Roman farmsteads were documented in the plain north of the river, with their linear alignment suggesting the presence of an ancient main road.

Another discovery this season was a possible rock sanctuary near Martini-Parasporistra on the slope of Kallidromo. This was defined by vertical cuts, niches, and other architectural features reminiscent of the Late Classical period.

The Boeotia Project continued in 2024 under the auspices of the NIA, with a restudy of the ceramic finds in the Thebes and Thespies Museum. John Bintliff (University of Leiden) and Lieve Donnellan (University of Melbourne) also undertook drone photography of 33 sites across the rural district of Palaeopanagia that had been discovered in the 1980s. This region has been noted for its agricultural fertility, with Greek and Roman estates situated near one another.

Euboea

The 2024 excavation at Artemision Amarynthos (ID 20657), led by Sylvian Fachard from the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece (ESAG) and Angeliki Simossi (Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea), marked the final season of fieldwork at the Temple of Artemis before the project shifts to study and publication. This season confirmed the complex architectural history of the sanctuary, which first dates from the Geometric and Archaic periods.

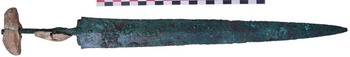

A significant find was the foundation of a rounded porch – which has yet to be precisely dated – located at the eastern entrance of the late eighth century BC apsidal temple (Fig. 3.21). Excavation in the apse of the temple revealed multiple construction phases and yielded rich finds from the eighth to seventh centuries BC, including drinking vessels, jewellery, figurines, and seals. Notably, Mycenaean-period artefacts were also discovered, such as a bronze dagger with a bone or ivory handle and a T-shaped figurine (Fig. 3.22). Beneath the Geometric–Archaic structure, remains of a LH IIIC (1200–1050 BC) rectangular building were uncovered, along with a large krater, and signs of an even earlier structure.

Fig. 3.21. Artemision Amarynthos: Rounded porch at the front of the late 8th century BC temple © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea / ESAG.

Fig. 3.22. Artemision Amarynthos: Mycenaean dagger with a handle from ivory or bone © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea / ESAG.

On the nearby hill of Paleoekklisies, three metres of sediment was also removed, reaching prehistoric layers and bedrock. This area produced a substantial quantity of EH I pottery (ca. 3000 BC), offering insight into early settlement activity long before the sanctuary’s formal establishment.

This year also saw Sylvian Fachard (ESAG) and Angeliki Simossi (Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea) lead the fourth campaign of the Eretria–Amarynthos Survey Project (ID 20658), alongside Chloé Chezeaux (ESAG/University of Lausanne). This project included an exploration of the banks of the Sarandapotamos River, continuing research into regional settlement patterns from the Bronze Age to the Byzantine period seen in recent seasons (ID 19601, ID 18580) Two groups investigated the area from the sanctuary and the upper valley of Vathia to Kallithea, and a third focused on the area around Gymnou.

Due to the accumulation of several metres of alluvial deposits, there were limited surface finds between Amarynthos and Kallithea. New data, however, suggest there was continuous occupation from the Classical to Byzantine periods in the area near the Church of Panaghia. In the nearby hamlet of Koukaki, previously known burials and a Macedonian tomb were noted, along with Hellenistic and Roman materials that attest to the presence of an ancient site. West of the Artemision sanctuary, surveys revealed that the ancient settlement was more extensive than previously thought and appears to have been connected to the upper Amarynthos valley by a probable communication route, suggested by a series of sites leading toward Kallithea. In the Gymnou area, intensive survey work uncovered dense concentrations of Late Byzantine and Ottoman ceramics northeast of the modern town, as well as Classical period materials in the southern sector – possibly indicating the location of the ancient site of Boudion. Carved blocks on nearby hills suggest ancient rural installations, possibly farms.

A new underwater research project began this past year at the ancient port of Eretria (ID 20659), which is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities (with Eleni Banou) and the ESAG (with Sylvian Fachard). The aim is to explore and document the ancient city’s harbour (Fig. 3.23). Beginning with bathymetric mapping of the seabed and extensive cleaning, key Hellenistic structures were identified, including sections of maritime fortification, the base of a round tower marking the southwestern corner of the city walls, and, just south of this, a newly discovered 20-metre-long wall, likely part of the city’s secondary enclosure. A second stretch of this wall was traced extending southwards.

Fig. 3.23. Ancient Port Eretria: Survey of the sunken sea fortification © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities / ESAG.

In addition, a 160m-long breakwater was found south of the fortifications, built from rubble and seemingly designed to prevent the basin from silting up. Amphora fragments from the western end and architectural blocks suggest this structure may have connected to a masonry quay. A massive 600m-long mole that was oriented north to south, now partly beneath a modern pier, was also documented. Its construction resembles the breakwater and includes a modern lighthouse at its southern end.

The Hellenic Ministry of Culture reported on a rescue excavation undertaken during water pipeline works in the Municipality of Eretria (ID 19679) where a well-preserved part of a late Classical (fourth century BC) house was uncovered near to the sanctuary of Apollo Daphniphoros, the Panathenaic Amphora Quarter, and the ‘House of the Mosaics’.

Excavation revealed a square room (3.50 × 3.55m) with a mosaic floor of small white pebbles, centred on a 1.13m medallion depicting two satyrs. The younger plays a double flute while the older, bearded figure appears to dance. Coloured pebbles (white, black, red, yellow) were used for detailed and realistic rendering. Raised mortar platforms (0.935m wide) along three walls suggest the room was an andron for – usually male centred – banquets and symposia, with the satyr imagery thematically linked to festivity. The building fits the Eretrian luxury house type with a central peristyle and elaborately decorated reception rooms, comparable to ca. 360–350 BC mosaics from the ‘House of Mosaics’. In the fifth to sixth centuries AD, the space appears to have been reused as a cemetery. The newly discovered mosaic has been cleaned, conserved, and reburied for protection, with the pipeline rerouted. Plans are in place for future display within the unified archaeological site of Eretria.

The Ministry of Culture reported on another rescue excavation undertaken during sewage works in the Municipality of Istiaia-Edipsos, Euboea, within the settlement of Oreoi, where part of an Early Byzantine basilica from the sixth century AD was uncovered (ID 20700). The building features brick-paved flooring and walls of rough and semi-finished stones comprising tiles, clay, and a thin layer of plaster on the external surface. Two massive pillars mark the start of the apse arch, each with interior steps. Finds include two iron crosses and a bronze candlestick wreath.

The basilica dates to the period when the diocese of Oreos was under the metropolis of Corinth, adding significantly to the sparse archaeological record for the fifth to sixth centuries AD in Euboea. The basilica is built within an older, extensive public building – possibly an earlier basilica – suggesting a complex construction history. Further excavation is planned to determine the earlier structure’s nature and the basilica’s wider context.

Joanita Vroom (Leiden University) reports on the most recent results from the Hinterland of Medieval Chalkida Project (HMC; ID 20701), which was undertaken between 24 August and 16 September 2024. This project is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea and NIA, and is directed by Alexandra Kostarelli from the Ephorate, with Vroom from the NIA (for recent results, see Vroom et al. Reference Vroom, Kostarelli, Kalantzis, Hoosbeek, Ferri, Gosker, Kane, Karagiannis, Nanetti, Caniato, Politis and Lamprakisforthcoming).

This season continued the work from previous seasons in Chalkida (ID 19674, ID 18602; see Vroom et al. Reference Vroom, Kostarelli, Blackler, Kalantzis-Papadopoulos and Kolvers2022), in which significant progress was made in mapping the Medieval landscape of central Euboea. During the season, the team identified 34 new sites from the Middle Byzantine to Ottoman periods – including churches, towers, domestic structures, water mills, wells, and fortified enclosures. Particularly notable were dense ceramic scatters indicating habitation or activity zones, and several undocumented ecclesiastical buildings in remote or agricultural settings.

In addition, intensive survey and trial excavations undertaken at the two towers of Mytikas in the Lileos Plain revealed a lime kiln, tile fragments, plaster and fresco fragments, Byzantine ceramics, and an iron buckle. Surface surveys at the Triada and Karaouli towers also produced rich ceramic assemblages dating from the Byzantine period, with finds extending into the Medieval period at Triada and as far back as the Neolithic at Karaouli. 41 soil samples were taken for analysis at the towers of Mytikas and the wetlands near Psachna and the Karaouli tower, and 11 Medieval towers and four churches were surveyed by an architect.

Athens and Attica

2024 marked the fourth season of the five-year collaborative project at Hellanion Oros, located on Aegina (ID 20703). The project is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Piraeus and the Islands and the ESAG, and is directed by Stella Chryssoulaki from the Ephorate and Tobias Krapf from the ESAG, alongside Leonidas Vokotopoulos and Sofia Michalopoulou. Work this year included excavations on the Bronze Age remains on the summit and survey in the island’s south, providing information on the diachronic use of the area, from the Neolithic period onwards.

Excavation focused on the Mycenaean settlement on the summit, where two buildings yielding large groups of storage and cooking vessels were unearthed (Fig. 3.24). A Mycenean tomb with the skeletons of an adult and a small child was also found in a pit underneath the floor of the building on the summit.

Fig. 3.24. Hellanion Oros, Aegina: Late Mycenaean vessels in one of the areas excavated in 2024 © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Piraeus and Islands / ESAG.

Survey identified two new sites: one on a rocky peak west of Mount Hellanion, with Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age pottery (fourth to third millennium BC), and another near Vlachides, where terrace walls and ceramics indicate occupation from at least the Mycenaean period onward (Fig. 3.25). Other discoveries included a large quarry with unfinished millstones, linked to Aegina’s long tradition of volcanic andesite exploitation. Five souváles (rock-cut cavities adapted for water storage) were also recorded, offering new insight into local resource management.

Fig. 3.25. Hellanion Oros: Survey to the west, featuring a site in the foreground dating from the end of the 4th to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Piraeus and Islands / ESAG.

A new five-year programme of underwater research began in Salamis in November 2023 (ID 20705), a site located along the northwestern side of Ambelaki Bay, where previous research has been carried out on the Classical city of Salamis and the Pounta Peninsula (ID18173, ID 11493; see Lolos Reference Lolos2022). The project is directed by Giannos G. Lolos (University of Ioannina) and Angeliki G. Simosi (head of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Piraeus and Islands) and operates under the auspices of the Institute of Underwater Archaeological Research and the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities.

In November 2023, work focused on the submerged Classical city on the bay’s northwestern side, where the fourth century BC sea wall – three to four metres thick and reinforced with towers – was fully mapped. Excavations were undertaken on a large, partially submerged public building (likely a stoa), measuring at least 32 × 6m and comprising six to seven rooms (Fig. 3.26).

Fig. 3.26. Salamis, Ambelaki: Part of a large public building, image from the southeast © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities / H.I.M.A.

Finds from the western edge of the building include a 4.15m-long stone drainage channel, a probable horseshoe-shaped column base, and a substantial assemblage of pottery – mostly from the Late Roman/Early Byzantine and Medieval to Modern periods. Numerous Athenian black-glazed sherds (fourth century BC), amphora fragments, red-glazed sherds, intact and fragmentary lamps (Late Roman, up to the sixth century AD), and a stamped Hellenistic amphora handle were also reported. Other finds include 95 clay objects (stoppers, weights), six bronze artefacts, marble vessel fragments, and bronze coins from the late fourth to early third centuries BC. Two inscribed column fragments (Roman and Classical/Hellenistic) were also found, as well as a statuette fragment of Asclepius from the late fourth century BC (Fig. 3.27), and a small stone anchor – the second such finding from the port. Evidence suggests the building marked the eastern edge of the Classical/Hellenistic agora, near the harbour described by Pausanias in the second century AD.

Fig. 3.27. Salamis, Ambelaki: Fragment of a marble statuette of Asclepius, dating from the late 4th century BC © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities / H.I.M.A.

In Athens, Jutta Stroszeck (DAI) reports on the continued excavations at the Kerameikos (ID 20706; see Stroszeck Reference Stroszeck2022 for recent scholarship on the site). This year, the focus was on the fourth century BC ‘banquet room’ that was discovered off the Sacred Way in 2023 (ID 19629), along with the area to the west. The excavations unveiled a 15m2 room featuring an oval mosaic of polished pebbles. To the north, a white limestone drainage channel was found connecting the rooms, suggesting a water-management system, while lime deposits suggest frequent water usage. The mosaic does not extend to the walls on the eastern or northern sides, which might suggest the presence there of bathtubs; however, it is pointed out that the oval mosaic design would be unusual in this context.

A second trench in the vicinity of Well B 37, in the southwestern part of the site, documented three construction phases of the well: first, an initial lining with large limestone monoliths; second, the well rim was covered with a compact layer of lime mortar (Fig. 3.28); and third, a rectangular casing made of limestone blocks was placed into the mortar. It remains unclear whether a bathing area existed in this area in the fourth century BC.

Fig. 3.28. Kerameikos: Well B 37, second phase of the well rim © DAI (Photo Jutta Stroszeck).

Rescue excavations in Athens have produced exciting and significant finds during 2024–25. On Vasilissis Olgas Avenue, a large Roman-era complex was uncovered near the statue of Lord Byron (ID 20707). This excavation commenced on 16 May 2025 and was led by the Ephorate of Antiquities in Athens (Fig. 3.29). While the site was first unearthed in the late 1880s by Stefanos Koumanoudis, the new rescue excavations – spanning an area 68m in length and 11m in width – have unveiled 60 rooms around a peristyle courtyard. This is understood to have been built during Hadrian’s eastern expansion in the second century AD and then rebuilt after the Heruli invasion in AD 267.

Fig. 3.29. Vasilissis Olgas Avenue: Monumental Roman complex built during Hadrian’s eastern expansion of Athens © Hellenic Ministry of Culture/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D).

Three building phases were identified across the site: the first in the second century AD, including a limestone block construction; the second, in approximately AD 267, utilizing reused stone and brick; and the third, in Late Antiquity, producing smaller and less durable structures. Key finds include a large square room (7.65m per side) with pale mortar flooring; a third to fourth century AD destruction layer with sherds from roof tiles, pottery, amphorae, and cooking vessels; coloured mortars; a courtyard with a rock-cut well; and remains of a fourth century BC defensive ditch along the Themistoclean Wall. Byzantine layers revealed 15 built cisterns and four large clay storage pits, indicating later residential or commercial use.

In addition, limited excavation at the Zappeion entrance uncovered further Late Antique building remains. Plans are in place to transform the area around Vasilissis Olgas Avenue into a pedestrian-way with viewing platforms.

The Ephorate of Antiquities of the City of Athens also reported a rescue excavation (ID 20708) carried out in 2024, after works for a natural gas network uncovered a statue of a naked male figure in the Ludovisi Hermes type (Fig. 3.30). The find was made within a structure built of rectangular blocks at the intersection of Erechtheion and N. Kallisperi streets, near the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. This area is known for its large, luxurious villas dating from the Imperial period (first to fifth centuries AD), and it is possible that the statue originated from one of these residences. The sculpture has now been transferred to conservation laboratories for further study and preservation.

Fig. 3.30. Erechtheion and N.Kallisperi streets: Part of an Ancient Greek statue was found in central Greece, close to the Herodion © Hellenic Ministry of Culture/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.).

The rectangular structure uncovered within these rescue excavations continued to yield new findings. As reported by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture on 11 December 2024, fragments of statues, including the torso of a second life-sized male figure, were found, along with figurine fragments and lamp sherds from the fifth century AD (Fig. 3.31). These finds have also been transferred to the conservation laboratories of the Ephorate of Antiquities of the City of Athens.

Fig. 3.31. Erechtheion and N. Kallisperi streets: New findings near the Herodion © Hellenic Ministry of Culture/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.).

The Aegina Harbour City Project (ID 20678) entered its fifth year in 2024. The project is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, represented by Despoina Koutsoumba, and the EFA, with Kalliopi Baika and Jean-Christophe Sourisseau (Aix-Marseille University/CCJ-CNRS), alongside Paraskevi Kalamara (Byzantine Museum). The focus this year was on Sectors 1 and 2 of the military harbour.

In Sector 1, excavation of a Byzantine settlement uncovered new elements of ‘Building E’, with two test trenches yielding ceramics and tiles that confirmed an Early Byzantine occupation. Evidence also showed that the harbour’s rampart had fallen out of use by the Roman era.

In Sector 2, excavation of the neosoikoi (ship-sheds) in the northeast advanced with test pits along stylobates SR11 and SR12, shedding light on construction methods and chronological phases. The southwest fortifications were also investigated, clarifying their foundation techniques and building history. At shallow depths near Avra Bay, long obscured walls and structures were identified again, offering a rare glimpse into architectural remains otherwise lost beneath modern development. Even more striking was the discovery of structure STR4: a monumental, submerged stone structure over 70m long and up to 30m wide, which has been preserved to an impressive height. Spanning phases from the Classical to the Late Roman periods, it extends the line of the acropolis cape, dramatically altering our understanding of Aegina’s maritime landscape.

Work was also carried out in Sectors 3 and 4. In the former, investigations pushed into the southern breakwater; while, in the latter, experimental port archaeology was implemented to reconstruct ancient engineering in practice.

The excavations at the Athenian Agora, conducted by the ASCSA (ID 20641), were reported on by John K. Papadopoulos (UCLA) and Debbie Snead (California State University). Results from the earlier 2013–19 excavations at the site can be seen in the publication of Camp and Martens (Reference Camp and Martens2020).

Excavations in 2024 ran from 10 June to 2 August. This was the second season focusing on the area beneath the building at Agiou Philippou 14 – labelled area Beta Kappa (BK) – with work in 2023 also centred on this area (ID 19631). In BK North, Middle Byzantine walls (mid-twelfth to mid-thirteenth century) forming Rooms P and M were uncovered, including reused marble and limestone door blocks that displayed multiple phases of use. Room M yielded evidence of industrial activities, including metallurgy and glass production (slag, hearth bottom, vitrified sherds). There was also an Ottoman period pit (Pit D), and a water channel, with other finds including a Roman female torso in marble, and a Kerch-style red-figure sherd from a closed vessel.

In BK South, features include a possible Middle Byzantine pillar or wall, beside which an extensive dump of murex shells was found, indicating large-scale purple dye production from a deep-water Saronic Gulf species. Moreover, a square, stone-lined structure (Pit A), which was first identified in 2023, was found to contain iron-working waste and modern materials, such as plastics. It is also reported that internal cavities can be seen in the centres of opposing walls, suggesting the presence of beams or climbing scaffolding. While excavation reached 1.80m, the bottom of the pit was not located. A Late Roman pit was also identified in the southeastern corner of the trench. In BK West, the removal of modern fill exposed a large circular pit (Pit B), which was 2.6m in diameter and partially stone lined. This feature had been integrated into the basement of the modern building that was removed in 2022 (ID 18538).

Other finds included: equine remains; a possible Ottoman wall; a Latin Bottony crucifix; a painted Roman terracotta figurine head; and a human skull with a Frankish-period coin found beneath it, which may or may not be associated. Ancient DNA sampling of 133 Mycenaean and Early Iron Age burials – taken from the crania, petrous bones, and long bones – continued from 2023. This sampling was a collaboration between the Wiener Laboratory, Harvard University, and the Max Planck Institute, with preliminary results appearing promising.

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese has continued to yield archaeological remains of great interest, with many sites and campaigns producing significant results. The 2024 season at Pylos focused on publication and study (see e.g. Davis and Stocker Reference Davis, Stocker, Aruz, Fabian, Kumar, Macdonald and Weingarten2023; Davis, Stocker and Aruz Reference Davis, Stocker and Aruz2024). According to ceramic analysis, it is reported that human activity on the northwestern side of the Demopoulos field in Area H began in LH IIIA2 Early and continued until LH IIIC Early 1. Extensive conservation work was also undertaken, which revealed, among other discoveries, that the incised decoration on the hilt of the sword of the Griffin Warrior shows lions preying on wild goats. The gold of the hilt was also analysed (Fig. 3.32).

Fig. 3.32. Pylos: ‘gold embroidery’ on the hilt of the sword of the Griffin Warrior © Palace of Nestor Excavations, The Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati.

Excavations continued at Kleidi-Samiko (ID 20709) for a third year, focusing on Zone A, south of the railway line. This is a five-year synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Ilia and the Austrian Archaeological Institute (OAI), co-directed by Erofili-Iris Kolia from the Ephorate and Birgitta Eder of the ÖAI.

The focus this season was the northwestern half of a large, elongated building (Fig. 3.33), previously identified by geophysical survey (ID 17886) and other fieldwork (ID 18544). Excavation also revealed a second major space (Northwest Hall, 8.5 × 7.44m) with two axial internal supports constructed from limestone, possibly reflecting temple architecture from the sixth century BC. Roof tile deposits were also identified, indicating that the building was abandoned around 300 BC. Significant finds include a large marble krater showing ancient repairs (which may have imitated a bronze basin used for ritual cleaning), and a bronze inscribed plaque (40.5 × 27.5cm) that documented the dedication of the sanctuary to Poseidon of Samikon (Fig. 3.34). The roof tile fragments provide evidence of a Laconian-style tiled gable roof.

Fig. 3.33. Kleidi-Samikon: Drone photo of the northwestern half of the building © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Ilia / ÖAW-ÖAI.

Fig. 3.34. Kleidi-Samikon: A bronze tablet was found close to a column base in the northwestern hall, possibly from the 4th century BC © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Ilia / ÖAW-ÖAI.

Additional geophysical and geoarchaeological surveys north of the railway revealed the continuation of Wall A and possible water-management structures, mapping the ancient lagoon and clarifying site stratigraphy (Fig. 3.35). Ongoing conservation and analysis of these finds, together with planned future excavations, aim to clarify the sanctuary’s extent, architecture, and role within the site’s ritual landscape.

Fig. 3.35. Kleidi-Samikon: View of Wall A, running from east to west © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Ilia / ÖAW-ÖAI.

Work also continued in Olympia (ID 20170) in 2024, with a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Elis and the DAI. Erofili-Iris Kolia represented the Ephorate, with Oliver Pilz (University of Mainz), Andreas Vött (University of Mainz), and Dennis Wilken (University of Kiel) from the DAI. During the season, a test trench was excavated along the north–south course of the Roman Altis Wall, aiming to date the wall more precisely. While no pottery was discovered to aid this task, the deep foundations of the wall were documented for the first time, suggesting it was of a considerable height (Fig. 3.36).

Fig. 3.36. Olympia: West profile of the deep foundations of the Roman Altis wall, suggesting it reached a considerable height. Orthophoto by Stefan Biernath © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Ilia / DAI.

In the south, an older trench on the Cladeos Wall was extended northward, revealing that the wall was composed of four courses of monumental stone blocks, reaching a preserved height of 2.80m (Fig. 3.37). A gravel layer adjacent to the lowest layer on the Cladeos side suggests it was a retaining embankment, perhaps part of early canalization. The geoarchaeological and geophysical work focused on the Cladeos Channel, west of this wall. Electrical resistivity survey revealed a ca. 25–30m-wide channel bounded by two walls and filled with sandy and gravelly sediments. As confirmed by core samples, this likely represents a later phase in the canalization process.

Fig. 3.37. Olympia: West side of the Kladeos wall showing four layers of monumental stone blocks, reaching a height of 2.80 m. Orthophoto by Stefan Biernath © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Ilia / DAI.

It is worth noting a new publication by Erofili-Iris Kolia (Kolia and Leventouri Reference Kolia and Leventouri2025), which provides a background to the sanctuary at Olympia and an overview of work at the site.

The 2024 research excavations at Trapeza, near Aigio – identified with the ancient city of Rypes (ID 20711) – were undertaken in October 2024. The project is directed by Andreas G. Vordos of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Achaia. This season’s focus was on Building C, a public building in the area southeast of the temple terrace. Excavation revealed a 16.8m long kerb with a stylobate, whose superstructural elements suggest a construction date prior to 300 BC. Fragments of Corinthian capitals were found, featuring Peloponnesian-type sigmoid bases and stylized acanthus leaves, comparable to the findings at the Temple of Apollo at Bassae. Remains of Ionic architectural members emerged within, suggesting that there was a nearby additional structure. Significant sculptural finds indicate at least three carved lions – two in a crouching position – and a marble funerary stele of a youthful male, all in Pentelic marble (Fig. 3.38).

Fig. 3.38. Ancient Rypes: Part of a funerary stele of a male youth was excavated © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Achaia.

In addition, intact burials were found inside the monument within cist graves and a sarcophagus, yielding high-status offerings from later periods, including gold earrings, a gold necklace, a gold ring, and iron buttons (Fig. 3.39). A nearby section also produced architectural fragments and pottery dating to the eighth century BC.

Fig. 3.39. Ancient Rypes: A pair of gold earrings with lion heads © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Achaia.

Fieldwork for the Ancient Tenea research programme (ID 20712), directed by Elena Korkas (Directorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities) and Paraskevi Evangeloglou (Archaeological Museum of Corinth), concluded in October 2024 (see Korka, Lefantzis and Corso Reference Korka, Lefantzis and Corso2019). During this recent season, the work revealed a monumental Hellenistic funerary structure of T-shaped plan, which appears to have been in use for centuries and was possibly linked to a healing cult. The burial chamber (2.75 × 7.4m), oriented north to south, contained a monolithic sarcophagus and five additional rectangular tombs. Only the sarcophagus preserved an in situ burial, with the remains identified as an adult woman in articulated form. This sarcophagus also contained bones of domesticated animals and a tortoise shell.

The tomb remained in use until the fourth century AD, after which it was looted and repurposed during the Late Roman period. Grave goods from the Hellenistic to Roman phases were numerous: a gold signet ring with an engraving of Apollo and a healing serpent; gold danakes (small silver coins, commonly used in Hellenistic and Roman burials), which imitate Sikyona coinage; silver tetrabolus (a coin common to the Hellenistic period) of Philip III Arrhidaeus; gold wreath leaves; a votive clay finger; small Hellenistic vases; and varied bronze, glass, and ceramic items – underscoring the association of the assemblage with funerary and healing cults.

Beyond the tomb, excavators uncovered a paved road on a north to south orientation, along with a rectangular enclosure to the north of the monument. In the areas surrounding this enclosure were found clay figurines of fingers and an arm, which might indicate healing-related worship, perhaps tied to the funerary cult. Architectural fragments point to a superstructure or associated buildings, warranting further investigation. It is hoped that further excavation will clarify the chronology of this feature. In the residential zone, Roman and Late Roman structures were recorded, including a well-preserved rectangular kiln with intact heating and firing chambers, which yielded abundant ceramic debris. These finds enrich current understandings of both Tenea’s ritual landscape and its domestic–industrial activity.

Excavations at the Sanctuary of Asclepius and in the city of Epidaurus (ID 20713) were reported in a press release by the Ministry of Culture in January 2024 (Fig. 3.40). The project is directed by Vasilis Lambrinoudakis (University of Athens), in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities of Argolis. At the Asklepion, the central square was cleared of accumulated stones and votive offerings found during the nineteenth to early twentieth century excavations, revealing its original function as a gathering space for pilgrims during sacrifices and processions. Approximately 450 stones were documented and relocated for study and storage.

Fig. 3.40. Sanctuary of Asclepius – Epidauros: Aerial photograph of the Asclepion © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Argolida / National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

In the western ‘Building K’ (second century AD), multiple building phases up to the late fourth century AD were identified, including a crypt suggesting use for mystical cult activities in the Late Roman period. Near the small theatre, the previously unknown ‘Mosque of Asclepius’, mentioned by Pausanias, was discovered. Dating back to the fourth century BC, its main phase aligns with second century AD renovations, likely connected to Hadrian’s visit to Epidaurus in AD 124. The sanctuary features an outdoor enclosure with monumental fountain and portico, Ionic-style water intake, and evidence for votive offerings, statues of Asclepius and Epione, and water-related cult use. Artefacts, including a shell engraved with the name of the god, clay discs, figurines, and lamps, confirm the identification of the site with the Temple of Asclepius (Fig. 3.41).

Fig. 3.41. Sanctuary of Asclepius – Epidauros: Fragments of a vase with an inscription of the name Asclepius and pieces of clay discs, and the bust of a deity © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Argolida / National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Progress has also been made this year in the area of underwater archaeology, for example in the work from the Asine and Tolo project (ID 20723), which is a synergasia between the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, the SIA, and Stockholm University – with additional participants from Gothenburg University and the Nordic Maritime Group.

The project ran from 7 to 11 October 2024, and is reported on by Niklas Eriksson and Ann-Louise Schallin (Stockholm University). This was the third year of a five-year project, continuing the pilot study undertaken in 2021. Since then, excavations have revealed the harbour to be more extensive and complex than previously understood.

In 2024, the aim was to find datable layers and artefacts (Fig. 3.42). Excavation was undertaken north of the harbour structure and the previous trenches, where they found the sediment around the structure to be disturbed. Work was undertaken by hand with a water dredge, with sediment below the uppermost 30cm collected and investigated. After removing layers of stones, the remains of two amphorae were identified (Fig. 3.43); however, it was challenging to find datable artefacts and contexts, with this work continuing.

Fig. 3.42. Asine and Tolo: Photogrammetric model of the underwater trench after excavation in 2024 (photo by Jens Lindström/NMG) © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities / SIA / Stockholm University.

Fig. 3.43. Asine and Tolo: Remains of amphora were discovered underneath a stone-built platform (photo by Jens Lindström/NMG) © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities / SIA / Stockholm University.

Another significant coastal excavation is the Lechaion Harbour and Settlement Land Project (ID 20656), which is a synergasia between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Corinth and the ASCSA. The excavations are under the direction of Georgios Spyropoulos from the Ephorate and Paul Scotton from California State University, with the project building on previous excavations that ran from 2016–18 (Scotton et al. Reference Scotton, Kissas, Ziskowski, Fallu, Ierardi, Radloff, Reynolds, Sarris and White2024).

This season yielded significant discoveries across multiple areas. In Area A (Fig. 3.44), the Room with the Tile Floor revealed ceramics dating to the late fifth century AD, along with a partially preserved female skeleton trapped beneath roof collapse, which included Laconian roof tiles. The skeleton was found incomplete, with displaced and crushed bones found nearby, leading to many soil samples being recovered from the collapse. Excavation also showed the tile floor to extend beyond the current walls, proving the room was once part of a much larger structure that predated the Augustan stoa. Investigation of a supposed drain revealed no outlet or water channel, leaving its purpose uncertain.

Fig. 3.44. The Lechaion Harbor and Settlement Land Project: Area A, where a collapsed roof and associated debris dated to the 5th century CE were found © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Corinth / ASCSA.

In Area B, excavation of Room 3 exposed collapsed square floor tiles in two distinct dimensions, corresponding to both Roman and Hellenistic foot measurements – the former used at Corinth and the latter at Isthmia. To the south, Room 4 was partly uncovered, yet had fewer tiles. Pottery indicates the collapse occurred around the late fifth century AD. In Area C, work exposed more of an Augustan-period floor beneath later Flavian construction in the basilica’s northwest; however, the fill was composed of gravel and sand, making it unstable and prone to collapse.

In the southwest, mortar floors were found along with a stone mortar-lined basin. In Area D, excavation continued from 2023 (ID 19642), with key finds this season including: a bronze, barbed arrowhead linked to the Battle of Lechaeum; a well-preserved tile grave of a 17-year-old female (first century BC to first century AD), with nails suggesting a wooden coffin (Fig. 3.45); a reused Gazan amphora, likely employed as an infant burial container; and a modern bullet casing (suggesting the fill was disturbed during bulldozing for beach access). Ceramics dated this area from the fourth century BC to the Late Roman period. Excavation also refined the mausoleum’s outer diameter to 90 Corinthian feet, suggesting a Greek or Hellenistic origin.

Fig. 3.45. The Lechaion Harbor and Settlement Land Project: A tile grave was uncovered in Da07 © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Corinth / ASCSA.

Additional specialist studies revealed evidence of Roman oyster cultivation and purple dye production, with environmental and geomorphological sampling and analyses continuing.

Work also continued at Isthmia. The Michigan State University Excavations (ID 20655), directed and reported by Jon M. Frey (Michigan State University), focused on survey, archival work, and site management under a permit from the Hellenic Ministry of Culture. Collaborative efforts with the University of Chicago, Notre Dame Excavations, and geophysicist Michael Arvanitis were partly limited by property access, but survey work identified key features across the site. Near the West Cemetery, five anomalies were recorded, likely representing graves. In the East Field, a cluster of right-angled architectural remains suggests previously unrecorded rooms at approximately 1.15m depth. South and east of the Roman bath, anomalies indicate the eastern continuation of the courtyard, while a dense cluster of unresolved features east of Rooms VII and XII is scheduled for limited excavation in 2025.

The University of Chicago Excavations at Isthmia (ID 20714), directed and reported by Elizabeth Gebhard (University of Illinois, Chicago) and Alessandro Pierattini (University of Notre Dame), were conducted under the guidance of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Corinth. At the Archaic Temple of Poseidon (for an overview of pottery from the site, see Hayes and Slane Reference Hayes and Slane2022), Pierattini analysed stone and stucco using non-destructive techniques, including: X-ray fluorescence; focused ion beam milling–assisted scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive spectroscopy; transmission electron microscopy; and electron energy loss spectroscopy, identifying two stucco types and carbon particles potentially useful for dating, while documenting previously unrecorded architectural blocks.

The study of the marble basins (perirrhanteria) demonstrated their role in ritual activity at the Sanctuary of Poseidon during the Late Archaic period, prior to their placement at shrine entrances. Overall, the season combined advanced material analysis, detailed documentation, and improved conservation systems, while preparing the site and its records for ongoing research and future study.

Chris A. Pfaff (Florida State University) reports on the excavations at Ancient Corinth (ID 20654), a long-standing undertaking of the ASCSA. The 2024 season focused on the area northeast of the theatre in the Marble Room (Fig. 3.46). This is a large space, possibly serving as a changing-room (apodyterium), which was first uncovered in 2020 (ID 13473; see Pfaff Reference Pfaff2023).

Fig. 3.46. Corinth: Northeast of the Theater area after the 2024 excavation season (drawing J. Herbst). © American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Corinth Excavations.

Between April and June 2024, excavations revealed more of the western wall, a 2.36m-wide doorway, and sections of the opus sectile floor showing original circular-within-square designs and Late Antique repairs, undertaken with reused marble revetment. Fill from the seventh century AD was found covering the floor, which yielded building debris, pottery, window-glass, animal bones, and shell, along with a silver buckle and fragments of marble sculpture and Latin inscriptions, overlaid by a deep Middle to Late Byzantine fill. In the southwest quadrant, a lime kiln was cut into the Late Antique fill, which was likely in use during the Middle Byzantine period and abandoned sometime in the twelfth century AD, based on ceramics found within (Fig. 3.47). Northwest of this feature, a hoard of 10 coins (anonymous folles Class G, AD 1065–1070) was found in the overlying deposits. At the north end of the Marble Room, two probable sixth-century walls were revealed, with one showing evidence of probable earthquake damage. Work also continued west of the Marble Room, uncovering a doorway, a semicircular niche, and a partial hypocaust system – but no evidence of an elevated floor remained.

Fig. 3.47. Corinth: Lime Kiln above the Marble Room (photo C. Pfaff). © American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Corinth Excavations.

The stratigraphy suggests these rooms were abandoned before collapse. Conservation work in 2024 focused on wall paintings excavated in the 1980s (Fig. 3.48) and on an opus sectile fountain floor (decorative technique) in the Panayia Field, southeast of the Roman Forum (Fig. 3.49).

Fig. 3.48. Corinth: Wall with birds depicted in yellow panels (photo R. Nardi). © American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Corinth Excavations.

Fig. 3.49. Corinth: Opus sectile floor and fountain of the domus of the Panayia Field, after cleaning (photo C. Pfaff). © American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Corinth Excavations.

North Aegean

The 2024 field campaign on Samos (ID 20647) formed the second season of the collaborative project on the history of land use and connectivity of the sanctuary, led by Pavlos Triandafyllidis (Ephorate of Antiquities of Samos and Ikaria) and Wolfgang Rabbel (Kiel University), and reported by Jan-Mark Henke from the DAI.

During the most recent season, a dense network of seismic surveys refined the location of the ancient lagoon in the Chora plain, which was outlined in previous seasons (ID 18574). The so-called ‘Holy Road’ was traced 750m further east using GPR and geomagnetic surveys. Among numerous anomalies on either side of the road, a rectangular structure and a circular feature with a diameter of 32m were particularly notable.

The seismic measurements undertaken at the Heraion confirmed that the early Dipteros I temple (ca. 575 BC), which quickly became unstable, was constructed on significantly softer ground than its successor temple (ca. 530 BC), located 50m to the west. These results highlight the continued refinement of the Chora landscape, revealing both previously unidentified architectural features and key insights into early temple construction, stability, and site planning in the sanctuary. The integration of geophysical methods has proven especially effective in detecting buried structures and environmental features without invasive excavation.

South Aegean

Excavations of the sanctuary of Apollo on Despotiko (ID 19675), directed by Yannos Kouragios of the Ephorate of Cycladic Antiquities, continued in 2024, concentrating on buildings outside the main sanctuary in the direction of the shore. Building MN was first uncovered in 2023 (ID 19672) and dated to the sixth century BC. Recent excavations revealed an orthogonal plan with eight rooms, distinctive thick ‘double’ walls, and a central drainage channel. Finds included numerous roof tiles and an antefix with a gorgon motif, with evidence of at least two construction phases.

In Building Ω (Fig. 3.50), previously associated with a propylon, exploration of the interior confirmed two construction/renovation stages, the earliest in the sixth century BC. The area also yielded earlier finds of kouros fragments and marble bases. Nearby, north of Building Z, an additional room of the underlying Archaic Building Za was uncovered, oriented differently and yielding abundant Archaic ceramics. At Building B, cleaning south of Room 11 revealed concentrations of shells and ceramics from the sixth and fifth centuries BC, indicating its domestic function and long occupation. Finally, work on the Archaic cistern system included clearing the central cistern (Cistern 1), thus advancing plans for the restoration and study of the site’s water-management infrastructure (Fig. 3.51).

Fig. 3.50. Despotiko: Excavation of Building Ω, identified as a propylon in 2023, continued in 2024 © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades.

Fig. 3.51. Despotiko: During 2024, a cleaning of the archaic cistern system was carried out, and the embankments at the Southwestern corner of the Central Cistern 1 were removed © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades.

North of Despotiko, Yannos Kouragios (Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades) continued excavations at the sanctuary of Mandra on the islet of Tsimintiri (ID 19677). This season’s work established that previously unearthed structures formed two large Archaic complexes (A and B), extending across the southern part of the islet. Complex A proved to be a substantial orthogonal structure, measuring 18 × 23m, composed of at least six rooms arranged around a courtyard, with a separate building nearby (Fig. 3.52).

Fig. 3.52. Despotiko Tsimintiri: Western part of Complex A, view from the southwest © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades.

Complex B, larger in scale at 45 × 18m, consisted of two rows of aligned rooms flanking a probable courtyard. Its monumental eastern wing included Room X2 (129m2) with a stone ramp providing access (Fig. 3.53). Finds from both complexes, ranging from the late seventh to the fourth centuries BC, included black-figure ceramics, amphorae, relief-decorated pithoi, and pyramidal weights (Fig. 3.54). The arrangement of the rooms and their orientation towards the shore suggests they functioned as port installations.

Fig. 3.53. Despotiko Tsimintiri: Aerial view of Early Bronze Age Complex B © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades.

Fig. 3.54. Despotiko Tsimintiri: Sherds from the 2024 excavation at Despotiko Tsimintiri, featuring archaic pithos, inscribed vases, figurines, krater, and a weight © Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades.