1. Introduction

Health care reforms in recent decades have often included elements of market-orientation, such as provider competition, enhanced incentives for economic gain, and an increase in the share of private providers. Marketization reforms have been expected to lead to improvements such as higher efficiency and more innovation (Van de Ven, Reference Van de Ven1996; Domberger and Jensen, Reference Domberger and Jensen1997; Kruse et al., Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018), but have also generated a critical discussion regarding the potential for negative side effects such as increased tendencies of risk-selective behaviour. Risk selection in health care refers to a tendency of health insurers and providers, driven by economic incentives, to try to attract patient groups that are more likely to be profitable in that they are healthier or have lesser medical needs (Luft and Miller, Reference Luft and Miller1988; Van de Ven et al., Reference Van de Ven, van Kleef and van Vliet2015). Risk selection of patients is a threat both to efficiency in health care provision, as it reduces incentives for rationalization, and to equity in that it weakens access to health care for patient groups with greater health care needs. In tax-based health care systems, risk-selective behaviour is a problem foremost in the provision of services, since the state automatically provides health insurance. As provision of health services in tax-based systems, as found in, for example, the UK and the Nordic countries, is predominantly public, incentives for risk-selective behaviour can be seen as weaker in such systems than in systems where the majority of providers are private. However, as the share of private providers has increased in tax-based health care systems in recent decades, while economic incentives have become stronger in the public sector, risk-selective behaviour has come to be viewed as a potential problem. Risk selection of patients in publicly financed and regulated health care systems, where outright patient selection is typically prohibited, tends to take more indirect forms, such as establishing in more affluent areas, or orienting services towards certain select groups that are expected to be healthier, such as the young or physically active (Dixon and Le Grand, Reference Dixon and Le Grand2006; Goddard et al., Reference Goddard, Gravelle, Hole and Marini2010; Ellis and Fernandez, Reference Ellis and Fernandez2013). So far, however, there has been less research on risk-selective behaviour in tax-based health care systems than in insurance-based systems.

One case where market-oriented health care reforms have been introduced, including both privatization of provision and enhanced competition, is Sweden. Starting in the early 1990s, the share of private providers has gradually increased while patients have been offered more choice between different providers (Anell, Reference Anell2015). In 2010, the system's market-orientation was further accentuated by the introduction of a patient choice system, here called the primary care choice reform, where all approved providers compete on equal terms for public funding based on patient listings (Anell, Reference Anell2011; Fredriksson et al., Reference Fredriksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2013). Fears were voiced, particularly in national media, that new private providers would engage in risk selection of patients by locating themselves primarily in affluent areas (Dahlgren, Reference Dahlgren2008; Burström, Reference Burström2010). Proponents of the primary care choice reform argued that local health authorities could combat this form of risk selection through the regulation of local patient listing systems and risk-adjusting financial reimbursements (Fredriksson et al., Reference Fredriksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2013). Due to the decentralized nature of the Swedish health care system, the 21 locally elected county councils (landsting) enjoy a relatively high degree of autonomy in organizing health services provision within their respective territories (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Glenngård and Merkur2012a). This led to the primary care choice reform being implemented in practice as 21 local systems with slightly different characteristics, depending on the regulatory choices of individual county councils. The long-standing tradition of local autonomy in organizing health care provision in Sweden entails that the county councils have considerable freedom regarding the implementation of national policies including the design of reimbursement and listing systems. The policies developed at the local level also reflect the shifting political majorities in the county councils, which are elected every fourth year. Thus, party politics play an important role in local health care governance in Sweden. Left-wing parties such as the Social Democrats and the Left party have historically placed a stronger emphasis on equity as a goal in health policy, a concern which can also be expected to result in a greater concern with combatting patient selection.

The aim of the paper is to investigate empirically how Swedish local governments, the county councils, have acted in order to combat risk selection in primary care following the introduction of the primary care choice reform. The specific research questions addressed in the paper are what strategies have been employed by the counties to combat risk selection and whether there are any differences between local governments with left- or right-wing political majorities in this regard. Furthermore, the paper investigates whether there has been any development over time with regard to measures aimed at preventing risk selection.

In order to conduct the investigation, we draw on a framework of analysis identifying three main types of strategies to combat risk selection in primary care. By examining which, if any, of these strategies the Swedish county councils have used to combat risk selection in different time periods and whether political ideology played a role in their choices in this regard, the paper contributes to a fuller understanding of how local governments can act to combat social inequitites in primary care when marketization reforms such as privatization and patient choice are introduced.

2. Marketization of universal health care systems: a threat to social equity?

A frequently asked question in previous research is how patient choice reforms and privatization of provision in universalistic, tax-based health care systems affect social equity and the distribution of care resources (Dixon and Le Grand, Reference Dixon and Le Grand2006; Burström, Reference Burström2010; Fotaki, Reference Fotaki2010; Fredriksson et al., Reference Fredriksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2013; Isaksson et al., Reference Isaksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2016; Burström et al., Reference Burström, Burström, Nilsson, Tomson, Whitehead and Winblad2017). In tax-based health care systems, which have a single payer in the form of a public body, the impact of market mechanisms such as privatization and patient choice on social equity is somewhat unclear. Some researchers maintain that marketization policies in health care might not undermine equity as long as tax-based funding is maintained, the reimbursement is properly risk adjusted, and all patients have equal opportunities to choose a health care provider (Dixon and Le Grand, Reference Dixon and Le Grand2006; Le Grand, Reference Le Grand2009). Others have argued that even within tax-based systems, there may be mechanisms that can lead to increased social inequitites if market principles like privatization, competition, and choice are introduced (Fotaki, Reference Fotaki2010; Fredriksson et al., Reference Fredriksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2013; Burström et al., Reference Burström, Burström, Nilsson, Tomson, Whitehead and Winblad2017). Patient choice, for instance, has been considered a threat to equity since it mainly benefits resourceful groups that have better knowledge of their rights to choose and also make better choices (Burström et al., Reference Burström, Burström, Nilsson, Tomson, Whitehead and Winblad2017). Similarly, previous research has demonstrated a clear correlation between level of education and the degree to which patients make active choices of health care providers (Berendsen et al., Reference Berendsen, de Jong, Schuling, Bosveld, de Waal, Mitchell, van der Meer and Meyboom-de Jong2010; Rademakers et al., Reference Rademakers, Nijman, Brabers, de Jong and Hendriks2014). This indicates that the introduction of patient choice systems might undermine social equity due to the behaviour and differing capacities of patients themselves. Another form of threat to equity in health care systems due to marketization policies is the behaviour of health care providers. When providers are exposed to increased incentives to maximize economic gain, they might try to do so by selecting patients that are more ‘profitable’ in the sense of being cheaper to treat (Ellis, Reference Ellis1998; Barros, Reference Barros2003; Berta et al., Reference Berta, Callea, Martini and Vittadini2010). Such patients are generally younger, more highly educated, living in more prosperous areas, and, at an aggregate level, have better health status than average (Winkleby et al., Reference Winkleby, Jatulis, Frank and Fortmann1992; Martinson et al., Reference Martinson, Teitler, Plaza and Reichman2016). If providers are driven by profit motives, economic incentives to select profitable patients naturally become stronger, which is why privatization of health care provision is usually seen as increasing the probability for risk selection, or ‘cream-skimming’ (Ellis, Reference Ellis1998; Ellis and Fernandez, Reference Ellis and Fernandez2013; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Haisken-DeNew and Yong2015).

In publicly funded and universalistic health care systems, public regulators typically prohibit outright risk selection. However, in such cases, risk selection might occur through more indirect measures like the decision of where to locate medical practices (Isaksson et al., Reference Isaksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2016; Anell et al., Reference Anell, Dackehag and Dietrichson2018). If providers want to attract patients with low risk, they can locate in areas where citizens are less likely to have high health care needs. Since proximity is one of the most important factors when choosing a provider (Victoor et al., Reference Victoor, Delnoij, Friele and Rademakers2012), it is likely that providers located in more affluent areas attract patients with higher socio-economic status and lower health needs (Dahlgren and Whitehead, Reference Dahlgren and Whitehead2006). In this fashion, risk selection through location can undermine equal access to health care since there will be fewer health care providers in less affluent areas (Isaksson et al., Reference Isaksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2016). Indirect risk selection can also occur through other means, such as advertising foremost to certain groups, like the young and prosperous. Another type of risk selection is to design facilities and specialize in certain medical areas to attract specific patient groups (Wynand et al., Reference Wynand, De Ven, Ellis, Culyer and Newhouse2000; Le Grand, Reference Le Grand2009; Ellis and Fernandez, Reference Ellis and Fernandez2013).

Whereas it is often argued in the literature that risk selection is a problem in competition-oriented health care systems (Eggleston, Reference Eggleston2000; Greß et al., Reference Greß, Delnoi, Groenewegen and Saltman2006; Ellis and Fernandez, Reference Ellis and Fernandez2013), it remains an open question to what extent health care providers act in this way, and, if they do, whether such behaviour can be counteracted by regulatory measures. This question is particularly pertinent in relation to tax-funded health care systems, where policy goals such as solidarity and equitable access to care have been given a central role and where direct political control over the resource distribution through local health authorities has been seen as a way to promote these goals.

3. What can be done to combat risk selection?

Previous research identifies primarily two main methods to combat risk selection. The first is through regulation, which implies that public regulators create rules for how to list new patients, for instance by making it illegal to refuse a patient who wants to list herself with a given provider (Wynand et al., Reference Wynand, De Ven, Ellis, Culyer and Newhouse2000; Ellis and Fernandez, Reference Ellis and Fernandez2013). A second method of combating risk selection discussed in the literature is financial risk adjustment of compensation to provider based on socio-economic and medical information about the patients (Barros, Reference Barros2003; Rosen, Reference Rosen2003; Iezzoni, Reference Iezzoni2013). The risk-based adjustment implies that the size of the payment to the provider is better adapted to the expected costs of treating different types of patients, such as older patients, who can be expected to be unhealthier and develop more complications after procedures. Risk-adjusting the financial compensation to providers can be done in a variety of ways. In primary care, where a patient listing procedure is typically used and providers assume a long-term responsibility for the health of their patients during which a variety of health problems can occur, it is most common that the care provider receives a fixed payment per listed patient and year (a capitation fee). With risk adjustment, the capitation fee is adjusted to the patient's characteristics and medical ‘risks’, related to, for instance, age, socio-economic status, education, and employment. The weighting of the compensation is based on the expected link between health status and estimated future costs of care among different populations (Sundquist et al., Reference Sundquist, Malmström, Johansson and Sundquist2003; Ellis and Fernandez, Reference Ellis and Fernandez2013).

A central question asked in the literature is whether risk adjustment works as a way to prevent risk selection. So far, most research on this issue has been carried out in relation to risk selection on the part of health care insurers (Rice and Smith, Reference Rice and Smith2001; Kreisz and Gericke, Reference Kreisz and Gericke2010; van Kleef et al., Reference van Kleef, van de Ven and van Vliet2013). In tax-based health care systems, where risk-selective behaviour can occur only among publicly financed care providers, previous studies are more scarce. One exception is a Canadian study that examined the effect of a new, risk-adjusted payment system introduced to alter a heavily uneven distribution of primary care physicians in different areas in Quebec. The study found a significant effect of the new risk-adjusted payment system, as the ratio of doctors in the disadvantaged areas rose markedly after it was introduced (Bolduc et al., Reference Bolduc, Fortin and Fournier1996). Similarly, a Swedish study examining the effects of risk adjustment in primary care found that the inclusion of socio-economically based risk adjustment correlated with an increase in the supply of private primary health care centres in areas with unfavourable socio-economic and demographic characteristics (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Dackehag and Dietrichson2018). We are, however, not aware of any studies systematically investigating what strategies have been employed by local governments to combat patient selection, and whether ideology can explain differences in the use of such strategies.

4. Case study context: the primary care choice reform in Sweden

As noted in the Introduction, the Swedish health care system is heavily decentralized; it is governed foremost at the local level by 21 autonomous bodies, the county councils. These bodies are in charge of the organization and production of care, as well as the financing of health services for all citizens through local income taxes. The autonomy of county governments and the principle that their leaders should be directly elected by local populations has long historical roots in Sweden (Gustafsson, Reference Gustafsson, Batley and Stoker1991). The main argument in support of these principles in contemporary health governance is that directly elected leaders with a mandate to adjust national policies to specific local circumstances will be better suited to making policy adjustments based on the unique conditions in different parts of the country. The national government plays an important role in monitoring and evaluating the health services provided by the counties so that they are of equal quality and accessible on equal terms by the population (Fredriksson, Reference Fredriksson2012). Until the 1990s, primary care centres in Sweden were almost exclusively public and operated directly by the county councils, which also decided if and where any new providers could establish themselves within the region. The new primary care choice reform in 2010 changed this drastically; while leaving the basic funding structure of the tax-based system intact, the reform aimed at providing better opportunities for private providers to establish themselves within the publicly regulated and funded system in order to increase its efficiency and quality (Prop. 2008/09:74). The reform made it mandatory for all county councils to create a patient choice system, whereby all private health care providers who met certain basic requirements were allowed to open medical practices anywhere within a county. Furthermore, citizens should be free to choose a primary care provider by listing themselves with any provider of their choice, public or private. Provider funding was not to be guaranteed, but dependent on how well the providers managed to attract patients (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Nylinder and Glenngård2012b; Fredriksson et al., Reference Fredriksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2013). The reform, even though nationally binding, did leave the county councils a certain leeway in how to implement it at the local level. All county councils can formulate their own specific requirements on new primary care providers wanting to establish themselves in the region and design local reimbursement systems according to their own will (Fredriksson et al., Reference Fredriksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2013).

So far, the primary care choice reform has resulted in over 270 new private primary health care centres, in different parts of the country. This means an increase from 30 to 43% private health care centres in the country (Isaksson et al., Reference Isaksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2016). A great majority of these are for-profit, and roughly a third of the for-profit practices are owned by international private equity firms (Carlsson, Reference Carlsson2018). There has also been a clear tendency for private providers to open new practices in urban areas (Isaksson et al., Reference Isaksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2016). Evaluations of the primary care choice reform indicate, however, that the county councils have made active use of their right to develop their own local regulations in order to implement the reform, particularly with regard to the requirements placed on providers. Lundvall (Reference Lundvall2010) notes that several county councils have introduced local rules about patient listing that serve as a hindrance for new private providers in opening practices. Anell (Reference Anell2011) shows that the counties used different measures to steer the new providers, both in relation to reimbursement systems and requirements regarding the scope of services. These early evaluations thus identify several ways of preventing risk selection behaviour among the counties. They are also reflective of the fact that concerns regarding risk selection and a resulting decrease in equity was one of the most discussed issues when the primary care choice reform was introduced, particularly by the left (Fredriksson, Reference Fredriksson2012).

5. Methods and material

5.1 Selection of case: Sweden

Sweden is an appropriate case to study strategies for combating risk selection because of the country's long-standing political commitment to socio-economic equity in access to health services as well as health outcomes. Furthermore, increasing opportunities for patients to choose their care provider has been a central political trend in recent decades within Swedish health care (Winblad, Reference Winblad2008; Fredriksson et al., Reference Fredriksson, Blomqvist and Winblad2013). This has also led to the inherent conflicts between choice, privatization, and social equity receiving a great deal of attention from both scholars and policy makers. Sweden also presents an interesting case for the study of combating risk selection because of its far-reaching decentralization of health care governance, which implies that there are in effect 21 local regulating bodies which can choose different strategies towards this end.

5.2 Material

The data sources are foremost contracts between the county councils and private care providers in 2013 and 2016, i.e. the written documents that outline the prerequisites for each county council's patient choice system. Each county uses a standard contract template stipulating quality requirements and reimbursement formula for all providers. As such, we analyse the standard contracts developed separately by each of the 21 county councils. The contracts, typically 75–100 pages, contain information on quality requirements, scope and content of the services, reimbursement methods, and information regarding on what grounds a contract can be renegotiated or terminated.

The contracts were complemented with survey data on capitation rates and risk adjustment rates retrieved from the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR, 2016). These data were complemented with public data on political majorities in the county councils that were obtained from the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR, 2018).

5.3 Methods of analysis

To answer the first research question regarding the use of strategies to combat risk selection, the main method used to analyse the contracts was qualitative directed content analysis (Potter and Levine-Donnerstein, Reference Potter and Levine-Donnerstein1999; Hsieh and Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005; Elo and Kyngäs, Reference Elo and Kyngäs2008). This implies a deductive analytical approach, where previous studies guide the formulation of research questions, and the analysis of the empirical materials draws on pre-established concepts.

In order to conduct the directed content analysis, a framework of analysis was constructed, see below. With the help of the framework, the 21 contracts (one from each of the counties) were analysed and categorized deductively in order to determine to what extent the three strategies were used. Through the analysis, the framework itself was validated in terms of its relevance to the material. The research team was open to detection of strategies and explanations not included in the framework, which could otherwise be missed in a deductive analysis. No further strategies were, however, identified in the analysis. An advantage with a deductive analysis, on the other hand, is that it makes it possible to explain causal relationships between theoretical concepts and variables and thereby generalize research findings.

Descriptive statistics were produced to examine tendencies and variations among the counties. In order to capture developments over time, contracts were analysed at two different time points, 2013 and 2016. In 2013, the county councils had had three years to develop strategies to combat risk selection. In 2016, two years had passed since the most recent election in 2014, giving the newly elected county councils enough time to adjust their risk selection strategies if they decided to.

To answer the second research question as to whether there were any differences between strategies used by local governments with left- and right-wing majorities, we divided the counties based on political majority. In 2013, nine of the 21 Swedish counties were governed by right-wing majorities and 11 by left-wing majorities, and one county by a coalition of left- and right-wing parties. In 2016, this changed to five counties governed by right-wing majorities, 12 counties governed by left-wing majorities, and four counties governed by mixed majorities composed by both right-wing and left-wing parties. Coding of the contracts was done deductively by two members of the research team through the use of the analytical framework (described below). Once the analysis was finished, the research team met on several occasions to discuss and reconcile the interpretations.

Since the sample size was small, descriptive statistics such as mean values were used to present differences between counties, rather than to test the differences with more advanced statistical tests.

6. Framework of analysis

Drawing on previous research and empirical observations from Sweden (Lundvall, Reference Lundvall2010; Anell, Reference Anell2011; Anell et al., Reference Anell, Nylinder and Glenngård2012b), the framework of analysis used in the study identifies three strategies, or measures, through which the county councils may try to prevent risk selection of patients among private primary care providers: (1) risk adjustment through the financial reimbursement systems, (2) design of patient listing systems, and (3) requirements with regard to the scope and content of the services which have to be offered by the providers. The three strategies include both funding and production strategies.

The first strategy, risk adjustment through the reimbursement system, refers to the ways in which providers within the county council in question are reimbursed. The reimbursement system may consist of different risk adjustment measures, such as extra payment for weaker socio-economic groups and for establishments in more remote areas that could mitigate the impact of risk selection. Reimbursement systems in health care often consist of one or more of the following types: (1) a fixed payment (capitation) per patient and year, (2) variable compensation for specific activities, e.g. patient visits, and (3) pay for performance, i.e. a goal-related compensation for reaching a specific quality target, such as registrations of different diagnoses. Risk adjustment measures, in order to prevent situations where providers avoid sick and unhealthy patients, are most often connected to the first type, i.e. fixed payment (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Nylinder and Glenngård2012b). Thus, the higher the degree of fixed payment, the higher the ability to risk adjust.

The second strategy is referred to as the design of patient listing systems. This strategy refers to the creation of local systems for distributing patients who have not made an active choice of primary care provider. Previous studies indicate that this group can be relatively large and hence important for providers. It has been shown that some county councils have chosen to distribute unlisted patients to public providers only, which can be seen as a way to create barriers for private providers to enter local systems (Lundvall, Reference Lundvall2010). In other cases, county councils have been known to distribute unlisted patients evenly between providers in the region. In either way, publicly controlled systems for distribution of unlisted patients can be seen as a way to reduce opportunities for risk selection.

The third strategy is formulating requirements with regard to the scope and content of the services that all providers must offer in order to be allowed to establish themselves in a county. Requiring a broader range of services on the part of local authorities, including rehabilitation services, home-based care, or paramedical services, prevents providers from choosing a specific ‘orientation’ for their services and thereby targeting (or excluding) certain patient groups.

It should be noted that the strategies relate to both the provision and funding of health services. Provision structures are affected by the regulation of what services primary care providers must offer, and how patients can enlist with providers. Funding structures are affected in that the strategies also include systems for the allocation of funds to providers.

7. Results

7.1 Risk adjustment through the reimbursement system

The analysis of the data for risk adjustment through local reimbursement systems is presented in two steps. First, the extent to which fixed payments for listed patients (capitation) is used in the counties was investigated; second, the extent to which different kinds of risk adjustment measures were used was investigated.

The analysis of the contracts set up by the Swedish counties in 2013 and 2016 with regard to financial reimbursements shows that most counties used a combination of fixed (i.e. capitation) and variable payments where variable payments consist of payment per visit and/or pay for performance. Most of the counties had a high degree of fixed payment in both 2013 and 2016, see Table 1. In Blekinge and Jämtland, the capitation was close to 100%, and in most counties, the fixed capitation payment was between 80 and 90% in both periods. Stockholm is the county that stands out in that only 40% in 2013 and 60% in 2016 of the total payment consisted of a fixed payment and the rest was payment per visit and target-related payment.

Table 1. The degree of fixed payment (capitation) in the Swedish counties for the years 2013 and 2016, ordered by political majority in 2013

Interestingly, the fixed payment (i.e. capitation) rates have changed in almost all counties between 2013 and 2016, and on average, there has been a clear tendency for increased fixed payments. The average rate of fixed payments in the counties in 2013 was 80.4% and the corresponding figure for 2016 was 83.7%.

There are interesting political differences between the counties. The data presented in Table 1 show that in 2013, counties run by a left majority tended to have a higher degree of fixed compensation, whereas right-wing counties had a higher degree of variable payment. On average, capitation in right-wing counties was 76.7% at this time compared to 85.4% in left-wing counties. Uppsala, a right-wing county, had 70% fixed capitation and Jämtland, a left-wing county, had 100% capitation in 2013. Skåne, a right-wing county with high capitation, was an exception in this respect.

In 2016, the patterns changed. Counties governed by right-wing majorities increased their capitation payment, and there was hardly any difference between right-wing counties (84% capitation) and left-wing counties (83% capitation). Some of this can be connected to an increase of counties with a left-wing majority, but there were also increased capitation payments in counties with a retained right-wing majority. For instance, both Stockholm and Värmland increased their capitation, despite retaining their right-wing majorities.

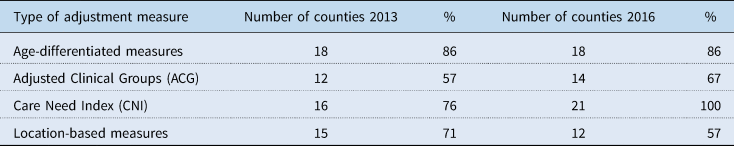

Table 2 below shows how the counties have chosen to risk adjust their fixed capitation. In most of the counties, 18 in 2013, the fixed payment was adjusted for age. Compensation adjusted by age means that providers receive a higher reimbursement for children and older patients. However, increased age is not synonymous with illness, which is why some caregivers may try to attract older, healthy individuals. To avoid this problem, several counties have chosen to adjust compensation based on how healthy patients are by risk adjusting using Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG). In 2013, 12 counties (out of 21) based their compensation on patients' health situation. Besides age and ACG, the fixed compensation was often adjusted based on socio-economic conditions, expressed as Care Need Index (CNI), as well as payment for geographic location. In 15 of the counties, the providers received extra payment if they located in remote areas. In 2016, the number of counties that used ACG and CNI to risk adjust had increased to 14 and 21, respectively, while the number that used location-based measures had decreased.

Table 2. Different kinds of risk adjustment measures in Swedish counties in 2013 and 2016

Furthermore, it was investigated if there were any political differences that could explain counties' use of risk adjustment measures. Figure 1 illustrates that in 2013, left-wing counties tended to use a slightly higher number of measures to adjust the payment for illness, age, etc., whereas right-wing counties tended to use a lower number of measures. In 2016 however, it had become more common for right-wing majorities and mixed majorities to use a high number of risk adjustments. It is also evident that there is an increase in the number of risk adjustments used in total; in 2016, all counties used more than one risk adjustment measure whereas this was the case for four counties in 2013.

Figure 1. Number of risk adjustment measures in the Swedish counties, separated by the political majority in 2013 and 2016. The y-axis shows the number of counties that used the corresponding number of risk adjustment measures.

To summarize, risk adjustment through the design of the financial reimbursement systems seems to be an important strategy in most of the counties. However, the variation is large between the counties regarding which combinations of measures are used. The result also suggests that left-wing counties were more prone to risk adjust in 2013 – nine of 11 left-wing counties used three or more measures. This changed in 2016, where counties run by right-wing majorities and mixed majorities used a higher number of risk adjustment measures compared to earlier.

7.2 Design of the patient listing system

The second strategy identified was the design of the local listing systems. When introducing the patient choice systems, some county councils actively chose to distribute unlisted patients only to public providers, which can be considered a way to create barriers for private providers to enter the market. However, when a patient choice system is in place, the most important question with regard to listing is how to handle people that just moved into the county. In 2013, 18 out of 21 county councils used the so-called passive listing for these individuals, meaning that they were automatically registered with a provider. The principle of passive listing was mostly based on proximity or previous distribution of registered individuals. Compared to 2013, no change had taken place regarding the listing patterns in 2016; 18 county councils still used passive listing. The remaining three counties used only active listing meaning that an individual needed to actively choose a primary health care provider to be registered; otherwise, the individual would be unlisted. In terms of creating a market, active listing can be seen as a barrier to entry, meaning that new providers will have difficulty attracting patients. On the other hand, use of passive listing can be seen as a strategy to reduce risk selection since patients will be distributed according to principles set up by the county councils.

7.3 Requirements of scope and content of services

The third strategy identified was the requirements regarding the scope and content of the services. This refers to what type of services primary care practices are required to provide in order to be allowed to locate in a county. The overall picture seems to be that the number of services demanded has increased slightly over time, as in 2013, the county councils required that providers should offer an average of 3.95 services, compared to 4.1 in 2016 (see Appendix 1).

Table 3 shows that in 2013, most of the counties required providers to provide child health care (71%) and rehabilitation services (81%) as well as visits to nursing homes (71%), see Table 3. Less common requirements included maternity care (38%) and podiatry (62%). In 2016, the scope of services required looked similar but there was a slight increase in the services required by the counties. For instance, more counties demanded that providers offered physician internships, 86% compared to 71% in 2013.

Table 3. Number and proportion of county councils that require a set of services to be included in their regular patient choice system for primary care, separated by political majority and years

Even though the differences are relatively small, it is possible to discern ideological differences between the counties in Table 3. In 2013, left-wing counties demanded to a higher extent than right-wing counties that providers should offer a broader range of services. For example, 64% of the left-wing counties demanded that health care centres should provide maternity care services, whereas this was only the case for about 11% of the right-wing counties. Furthermore, it was more common for left-wing counties to require primary care services to nursing homes (91%) compared to right-wing majorities (56%).

In 2016, left-wing counties were still more prone to require a broader range of services. For example, left-wing counties were more likely to require rehabilitation and primary care services to nursing homes compared to right-wing majorities. However, the ideological differences had decreased since 2013. For example, right-wing counties were in 2016 even more inclined than left-wing counties to require podiatric services and child health care services. Thus, it seems as if the counties have converged in their required scope of services over time.

A more detailed analysis of changes in total requirements of services across the counties from 2013 to 2016 revealed that changes in political majority did not, in most cases, lead to any substantive changes in the number and scope of services required (see Appendix 1). Hence, it seems like policies in this regard were more path dependent over time, following the initial decisions, than ideologically charged. There were also examples of counties, such as Stockholm, Värmland, and Västerbotten, where the alterations in the scope of services required seemed to go against ideological considerations, as the right-wing county governments in Stockholm and Värmland expanded their required scope of services after 2014 while the left-wing county of Västerbotten reduced it (see Appendix 1).

8. Discussion

Market reforms in health care such as patient choice systems may have positive effects in terms of efficiency and rationalization but could also lead to undesirable consequences, such as unwanted risk selection of patients. The main research question asked in this paper was what strategies were used by Swedish county councils to combat risk selection when new private providers established within the health care system after the 2010 primary care choice reform. The existence in Sweden of 21 local governing units in health care, which have created their own local systems of health regulation, presents a unique opportunity to investigate and compare different strategies to combat the threat of risk selection within the framework of a tax-based health care system.

The findings in the paper show that all three strategies to reduce risk selectionidentified through the analytical framework were used by the county councils, but to various extents. First, the counties used different forms of risk adjustments, such as extra financial compensation, to ensure that providers would also choose to list high-risk patient groups, such as the elderly and sicker patients. The analysis showed that all 21 counties used some form of financial risk adjustment to combat risk selection, and that the use of risk adjustment increased in 2016 compared to 2013, regardless of political majority in the counties. It should be noted that a large part of the difference in capitation levels was due to one outlier county – Stockholm. It can be argued, however, that this is natural since Stockholm is the far largest county with 22% of the population (2.3 million people). Stockholm county was governed in 2013 by a right-wing majority with an explicit agenda to attract more private primary care providers. The fact that this county together with Uppsala, the only other county at the time governed by a right-wing coalition, stands out as having the lowest level of capitation thus reinforces our conclusion that political ideology matters in the choice of strategies used to combat risk selection.

Second, the findings show that most of the counties used passive listing as a strategy but that the use of this particular strategy did not increase over time. Passive listing of patients who have not made active choices of providers can be seen as a strategy to combat risk selection in that patients then will be distributed according to principles established by the county councils, rather than pure market principles. A third finding was that a relatively large share of the county councils chose to impose requirements regarding the scope of services offered by private providers.. Many of the counties required what we labelled a ‘wide’ scope of services, which included services like maternity and child care, rehabilitation, and home-based care. Taken together, these findings indicate that most counties used a combination of measures to combat risk selection and that the use of such measures had increased over time.

The findings in the paper also indicate that political orientation played a role in decisions by local governments regarding the use of strategies to prevent risk selection – particularly early in the implementation of the reform. The empirical analysis indicates that left-wing counties were more active in trying to combat risk selection and used partly different strategies than right-wing counties to do so. Left-wing county councils also generally had a higher share of fixed payments, or capitation, in their reimbursement systems, which offer more opportunity to use risk adjustment to compensate for the risks carried by providers. Also, left-wing counties tended to require that providers delivered a slightly broader range of services than right-wing ones.

Interestingly, the findings in the paper also show that some of the differences regarding risk adjustment strategy choices between left- and right-wing counties diminished over time, regarding both financial risk adjustment and scope of services. This points to ideology being a more important factor in 2013 when the reform was recently implemented and the county councils had little experience and scarce empirical data to base their decisions on. Right-wing county governments, naturally more inclined towards supporting free market dynamics, may have been more sceptical towards risk adjusting and thus interfering with markets at that point. Left-wing majorities, on the other hand, may have been more concerned with the negative effects of the reform on risk-selective behaviour at the outset of the reform. A possible interpretation of the findings is that such ideological concerns were moderated over time by learning and the exchange of experiences between counties, leading to reduced differences in strategies over time (Grossback et al., Reference Grossback, Nicholson-Crotty and Peterson2004). If so, this could be an example of a ‘policy learning’ effect (Howlett and Ramesh, Reference Howlett and Ramesh1993; Stolt and Winblad, Reference Stolt and Winblad2009). This interpretation is in line with previous research showing that marketization policies in local governments are guided primarily by pragmatic concerns while ideology and politics are less important factors guiding local political decision making (Warner and Hebdon, Reference Warner and Hebdon2001; Bel and Fageda, Reference Bel and Fageda2007).

Other factors besides political ideology could also influence the strategic choices to combat risk selection made by the counties, for instance their geographical location or degree of urbanization. It may be particularly important for rural counties, regardless of political ideology, to prevent risk selection behaviour in order to secure access to care in remote areas (Kullberg et al., Reference Kullberg, Blomqvist and Winblad2018). Furthermore, as households in rural areas tend to have lower income levels than those in cities, it may also be hard in practice to separate strategies to prevent risk selection on socio-economic grounds from those used to secure access to care for remote households. A previous study carried out in Sweden indicates, however, that ideology played a strong role in how the primary care choice reform was implemented in rural Swedish counties, in that counties with left-wing majorities were more inclined to use risk adjustment strategies (Kullberg et al., Reference Kullberg, Blomqvist and Winblad2018). Furthermore, it is important to interpret all of the results with great care. Since the number of cases in the analyses is small, a change of the values in only a few counties could alter the results.

Finally, the findings in the paper also illustrate how several different strategies can be combined by local authorities trying to counteract risk selection in a marketized primary care system, characterized by competition and a mixture of providers. In this sense, we believe that the findings add to the literature in showing that strategies to counteract risk selection develop over time and are often copied between different local governments (Stolt and Winblad, Reference Stolt and Winblad2009).

In the literature, one of the most discussed risk selection mechanisms is the localization of providers. By establishing health care facilities in prosperous areas, providers are more likely to attract patients with lower health care needs. Even if it is not investigated here, it is reasonable to believe that most of the strategies used by the county councils have been developed to counteract this form of risk selection. Anell et al. (Reference Anell, Dackehag and Dietrichson2018) show in a study that risk-adjusting measures used in connection to the Swedish primary care choice reform have been successful in the sense of inducing providers to establish in areas with higher expected health care needs. What is less known is how risk-adjusting measures can be used to combat other forms of risk selection mechanisms, such as providers specializing services to attract certain patient groups – or designing facilities to avoid unwanted patient groups. In this sense, further studies are needed that investigate what kind and/or what combination of risk adjustment strategies are most effective in combating unwanted patient selection by providers.

9. Conclusion

Governments tend to use a wide variety of measures to combat risk selection in health care. Even if there is yet little systematic knowledge about the effects of such efforts, the findings in this paper indicate that local governments in Sweden actively used their regulatory powers to try to protect the egalitarian values of the health care system through such measures. These findings apply particularly to left-wing counties – but over time also to several counties governed by right-wing majorities. The results imply that local governments try to moderate the effects of national marketization reforms at the local level if they have the regulatory autonomy and political willingness to do so. More generally, the use of public strategies to combat risk selection provides an example of how the value of social equity can be upheld and protected within a tax-based health care system even as it undergoes a general transition towards marketization and privatization.

Appendix 1

Table A1. Number of services required to be included in each county council's patient choice system in 2013 and 2016