Introduction

During adolescence, a period between the ages of 10 and 19 years, young people go through several physical, psychosocial, and sexual maturation changes, including the development of gender identity and sexual orientation (World Health Organization, 2017; World Health Organization, 2018a). Here, we use the term sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth to refer to adolescents whose sexual orientation is non-heterosexual and/or their gender identity is outside the female/male binary (Smalley et al., Reference Smalley, Warren and Barefoot2018). In adolescence, SGM youth may face challenges that are related to their identity (The Lancet, 2011; Bregman et al., Reference Bregman, Malik, Page, Makynen and Lindahl2013). They may face victimisation and bullying (Espelage et al. Reference Espelage, Aragon, Birkett and Koenig2008; Huebner et al., Reference Huebner, Thoma and Neilands2015; Kosciw et al., Reference Kosciw, Giga, Villenas and Danischewski2015), as well as negative attitudes from peers and family (Bregman et al., Reference Bregman, Malik, Page, Makynen and Lindahl2013; Kosciw et al., Reference Kosciw, Giga, Villenas and Danischewski2015; Katz-wise et al., Reference Katz-Wise, Rosario and Tsappis2016; Puckett et al., Reference Puckett, Horne, Surace, Carter, Noffsinger-Frazier, Shulman, Detrie, Ervin and Mosher2017). To be able to face these challenges, SGM youth may benefit from the support of various professionals including health professionals (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2011). Appropriate support requires, for example, professionals’ competency, respectful attitude, and ability to fulfil SGM youths’ rights to information, privacy, confidentiality, and non-discrimination in healthcare (World Health Organization, 2015).

In healthcare, SGM people are often an invisible patient group (Fish and Bewley, Reference Fish and Bewley2010; McIntyre and McDonald, Reference McIntyre and McDonald2012). One reason for this is heteronormativity, defined as a general assumption that everyone is heterosexual and everything else is exceptional (Fish and Bewley, Reference Fish and Bewley2010; McIntyre and McDonald, Reference McIntyre and McDonald2012; Katz, Reference Katz2014). Norms, including heteronormative ones, are factors that are generally thought to guide human actions (values, beliefs, assumptions). They operate within social dimensions such as cultural, institutional, sexual, and/or interpersonal. Heteronormativity defines normative ways of life as well as normative ways of sexuality. It can be examined from three aspects: gender, sexuality, and heterosexualness (Jackson, Reference Jackson2006). First, gender is a state of being female/male in social and cultural levels, and sex refers to biological levels of being female/male (Smalley et al., Reference Smalley, Warren and Barefoot2018). In heteronormativity, gender is usually seen through a binary, where man and woman are opposites completing each other. Gender includes acts that are assumed to cohere with biological sex normatively, such as women being feminine and men being masculine. Second, sexuality is supposed to cohere with gender, as in women and men sexually desiring each other as complementary genders. Finally, heterosexualness is both sexual acts that are ‘natural and normal’ and non-sexual acts, such as a heterosexual woman/man having a biological need to reproduce (Jackson, Reference Jackson2006). Thus, young people who have a sexual orientation and/or gender identity that cannot be understood through heteronormativity, may experience invisibility in different fields of society, including healthcare. There are no earlier literature reviews that have summarised the encounters with SGM youth in healthcare. Thus, the aim of this study was to describe the encounters with SGM youth in healthcare based on the existing research. Furthermore, this study focuses for the first time on the role of heteronormativity and its relation to encountering SGM youth in healthcare.

Methods

An integrative review is a well-suited method for combining research with diverse methods (Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). It can give a new, comprehensive understanding of a specific phenomenon (Torraco, Reference Torraco2005; Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). An integrative review was conducted following Whittemore and Knafl’s (Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005) five-stage process: (1) problem identification, (2) literature search, (3) data evaluation, (4) data analysis, and (5) presentation of results (Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005).

Problem identification

In the problem identification stage, a clear aim for the review was defined to support the following stages (Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). The aim was to describe the encounters with SGM youth in healthcare based on existing research, and, to make a comprehensive review, no time limit regarding publication date was set.

Literature search

The literature search stage includes precise planning and description of the search strategy a priori to maintain the rigour in the review (Torraco, Reference Torraco2005; Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). A systematic search was undertaken between the 24th of November, 2017, and the 1st of January, 2018, in six electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, Eric, and Academic Search Premier. Search phrases included combinations of key terms and free-text terms for the following concepts: sexual and gender minorities (e.g. homosexual, transgender persons), adolescents (e.g. youth, teen), and healthcare practices (e.g. school healthcare, adolescent health services). The detailed search strategy is in Table 1.

Table 1 Search phrases in the literature search

The inclusion criteria for the literature were as follows: (1) a scientific, peer-reviewed research article, (2) the publication language was English, (3) a focus on the perspectives of SGM youth in healthcare practices, or (4) a focus on the perspectives of health professionals working with SGM youth. In this review, health professionals were defined as graduated professionals who are working in the field of healthcare. The article was excluded if (1) more than 50% of SGM youth participants were younger than 10 years or older than 19 years, (2) the study focussed on a medical condition (e.g. HIV), or (3) the study focussed on a health problem (e.g. tobacco or substance use). The latter two exclusion criteria based on the perception that studies focussing solely on a medical condition or a health problem do not include the perspectives of SGM youth or health professionals.

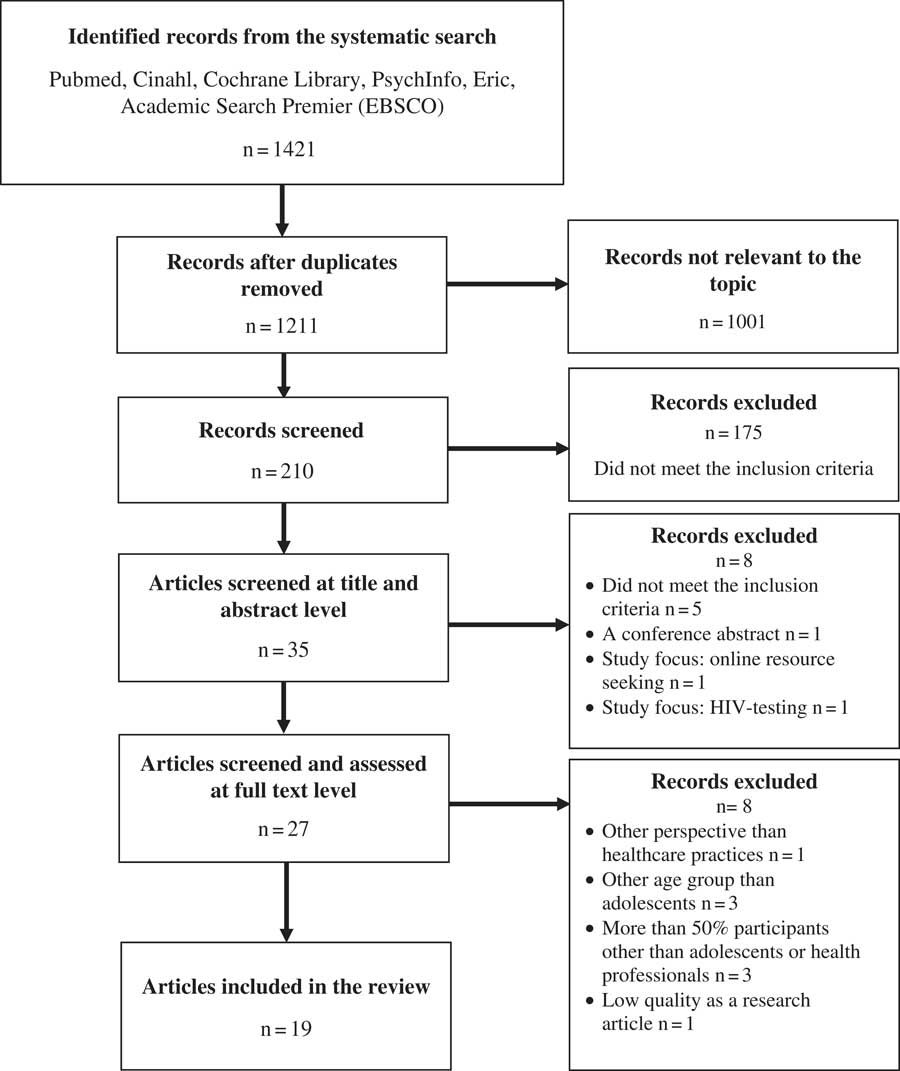

The total results of the systematic search included 1421 scientific, peer-reviewed research articles that were published in 1978–2017. Screening of the articles was done first at the title and the abstract level, and second at the full text level (Figure 1). Two authors screened the articles independently. During the screening process, the authors discussed the eligibility of the remaining articles. Some articles were excluded because the abstract was not available, or an exclusion criterion was fulfilled. One article was considered as ‘a borderline case’ because it was uncertain if 50% of the participants were 10–19 years old due to age group categories. However, because 40% of the participants were certainly 10–19 years old and the article was congruent with other inclusion criteria and the aim of the study, the article was included. Finally, 18 scientific research articles were included in the analysis.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of the article screening and selection

Data evaluation

The chosen articles were extracted, and the quality of studies was appraised (Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). The articles were extracted into two tables with key information about the studies. Table 2 describes studies conducted from SGM youth’s perspectives, and Table 3 includes studies conducted from health professionals’ perspectives (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2 The studies viewing healthcare from the perspective of SGM youth

Table 3 The studies examining health professionals working with SGM youth

To appraise the quality of the studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Checklist (MMAT) tool was used. Pluye et al. (Reference Pluye, Robert, Cargo, Bartlett, O’Cathain, Griffiths, Boardman, Gagnon and Rousseau2011) designed the MMAT tool to appraise the quality of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies in literature reviews (Pluye et al., Reference Pluye, Robert, Cargo, Bartlett, O’Cathain, Griffiths, Boardman, Gagnon and Rousseau2011; Souto et al., Reference Souto, Khanassov, Hong, Bush, Vedel and Pluye2015). A mixed methods study is a study that uses both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods, based on the definition in the MMAT tool. Quality appraisal started with evaluating criteria that were common to all studies (research questions) and specific to research design (data collection and findings). For each criterion, response options were ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘can’t tell’. Next, to score the quality, all ‘yes’ answers were summed, and then divided by the total number of criteria. Finally, the number was multiplied by 100, giving the total percentage score of quality. Two authors (ML, AP) did the quality appraisal independently and, through discussion, achieved consensus about the quality. These final scores were summed into Tables 2 and 3.

Data analysis

A deductive descriptive data analysis was performed (Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005; Whittemore, Reference Whittemore2007). Jackson’s (Reference Jackson2006) theoretical article was used as a theoretical framework to understand the role of heteronormativity in the healthcare of SGM youth. Based on this understanding, the elements addressing heteronormativity and breaking heteronormativity were identified from the studies, listed, and compared together. Finally, two themes with five elements related to heteronormativity and the encounters with SGM youth were identified.

Results

Study characteristics

The studies used a variety of research methods: qualitative interview (Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Lefkowitz and Mannell, Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2017) and qualitative questionnaire (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998) studies, mixed methods studies (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Rasberry et al., Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016), quantitative survey studies (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Porter, Lehman, Anderson and Anderson2006; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Mahdi et al., Reference Mahdi, Jevertson, Schrader, Nelson and Ramos2014; Vance et al, Reference Vance, Halpern-Felsher and Rosenthal2015; Shires et al., Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017), and a literature review (Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2013). More than half of the studies were done from the perspective of health professionals (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998; Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Porter, Lehman, Anderson and Anderson2006; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2013; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Mahdi et al., Reference Mahdi, Jevertson, Schrader, Nelson and Ramos2014; Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Vance et al., Reference Vance, Halpern-Felsher and Rosenthal2015; Lefkowitz and Mannell, Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017; Shires et al., Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017), four of which focussed on the healthcare of transgender youth (Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Vance et al, Reference Vance, Halpern-Felsher and Rosenthal2015; Lefkowitz and Mannell, Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017; Shires et al., Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017). One study was conducted before the 2000s (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998). Studies were done in the United States (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998; Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Porter, Lehman, Anderson and Anderson2006; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2013; Mahdi et al., Reference Mahdi, Jevertson, Schrader, Nelson and Ramos2014; Rasberry et al., Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015; Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Vance et al., Reference Vance, Halpern-Felsher and Rosenthal2015; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2017; Shires et al., Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017), in Canada (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016), and in the United Kingdom (Lefkowitz and Mannell, Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017).

Most studies considered SGM youth as a uniform adolescent minority group, and defined them as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Porter, Lehman, Anderson and Anderson2006; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Mahdi et al., Reference Mahdi, Jevertson, Schrader, Nelson and Ramos2014; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016), or queer (Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016). Several studies identified diversity in sexuality and sexual orientation; the youth were able to describe their identity through attraction, identity, experience, or behaviour (Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016) and could specifically describe their identity with the terms dyke, pansexual (Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016), or just other (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016). Some studies did not categorise identities at all (Rasberry et al., Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2017). East and El Rayess (Reference East and El Rayess1998) and Rose and Friedman (Reference Rose and Friedman2013) focussed solely on sexual minority youth which they defined as gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Ginsburg et al. (Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002) and Snyder et al. (Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016) defined transgender as a sexual orientation. Related to gender identity, the term cisgender was identified in the studies of Arbeit et al. (Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016) and Shires et al. (Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017).

Quality assessment

The quality scores ranged from 25% to 100% according to the MMAT tool. This range indicated that the quality of the studies was low to excellent. The most frequent score was 75% (n=7), and the quality of Scherzer’s (Reference Scherzer2000) and Lefkowitz and Mannell (Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017) studies was assessed as excellent with a score of 100%. The quality appraisal did not exclude any articles, but it gave an overview of the quality in studies in contrast with the results (Pluye et al., Reference Pluye, Robert, Cargo, Bartlett, O’Cathain, Griffiths, Boardman, Gagnon and Rousseau2011).

The themes of encountering SGM youth in healthcare

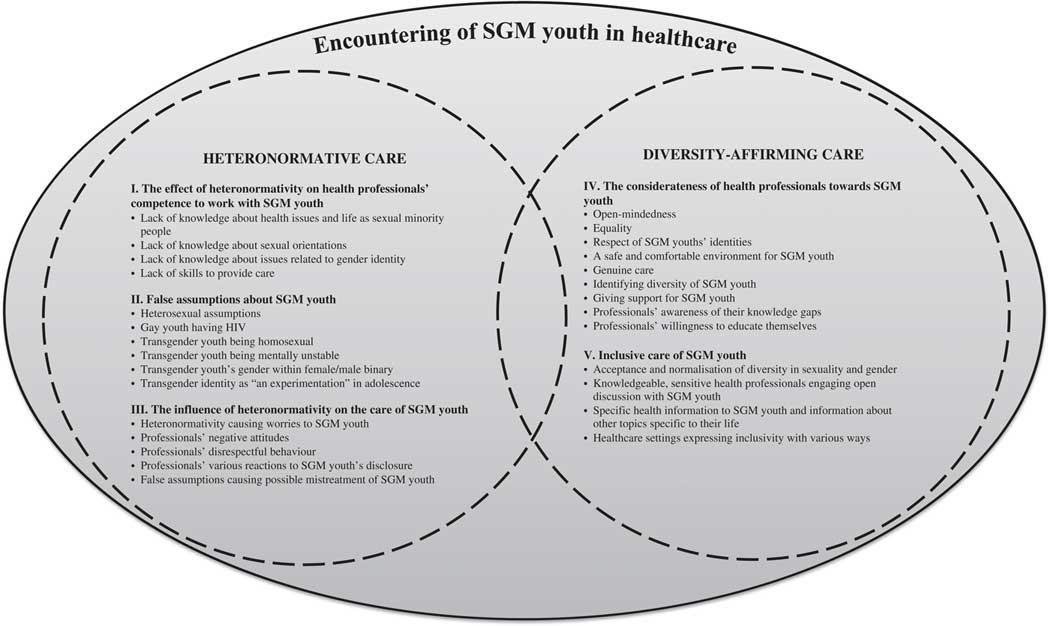

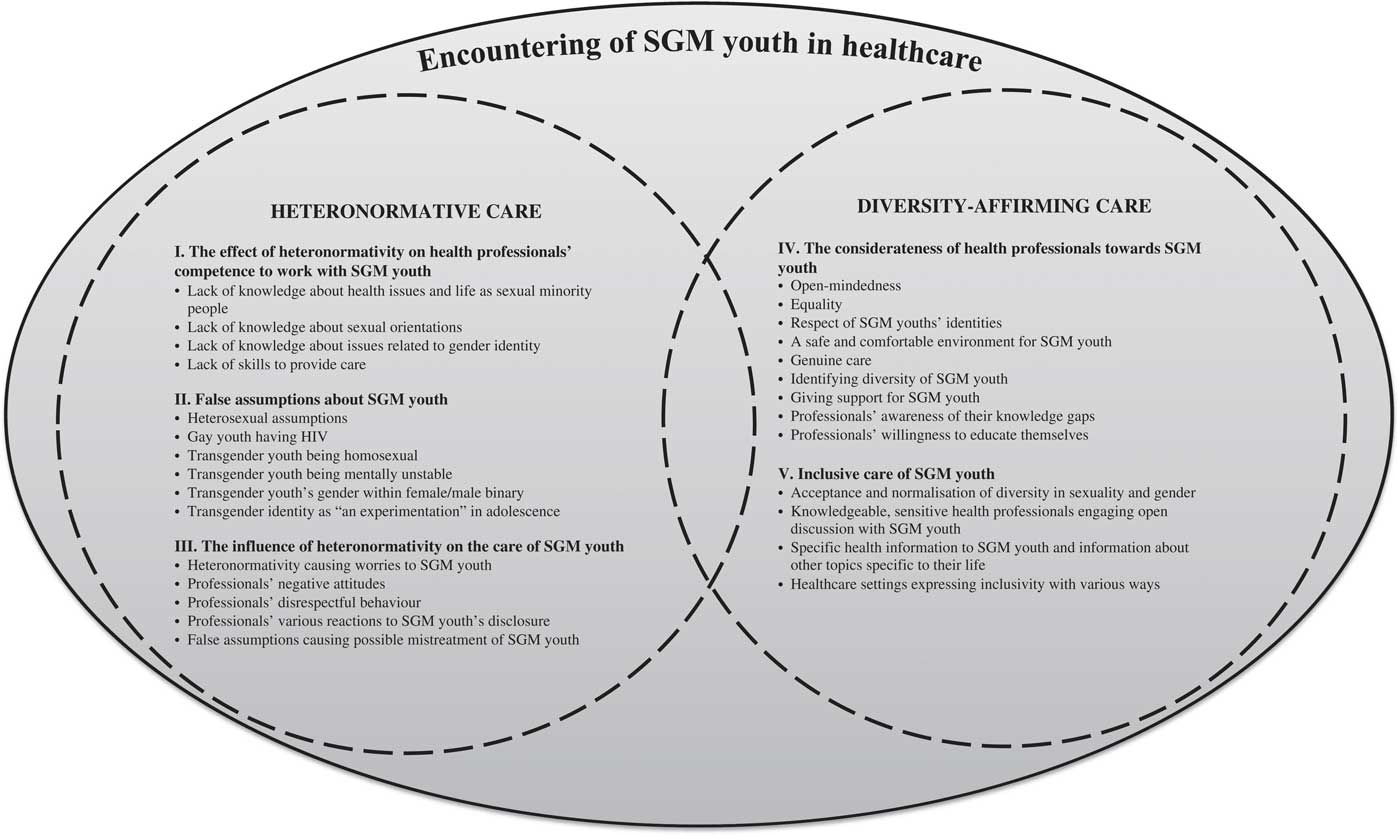

Based on the data analysis, the encounters with SGM youth in healthcare consisted of two themes heteronormative care and diversity-affirming care . This shows how the healthcare of SGM youth does not only include either heteronormative or heteronormativity-breaking elements. Both heteronormative care and diversity-affirming care have their own specific elements. These five elements include (1) the effect of heteronormativity on health professionals’ competence to work with SGM youth, (2) false assumptions about SGM youth, (3) the influence of heteronormativity on encounters with SGM youth, (4) the considerateness of health professionals towards SGM youth, and (5) inclusive care of SGM youth. The first three elements describe the heteronormative care, and the last two describe the diversity-affirming care. The encounters with SGM youth in healthcare can include elements from both themes (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The themes of encountering SGM youth in healthcare

Heteronormative care

Element 1. The effect of heteronormativity on health professionals’ competence to work with SGM youth

Most studies identified problems in health professionals’ competence to work with SGM youth. These problems can be related to heteronormativity. Scherzer (Reference Scherzer2000), Rasberry et al. (Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015), and Rose and Friedman (Reference Rose and Friedman2017) reported that SGM youth experienced health professionals lacking knowledge about SGM-relevant health issues and living as sexual minority people. Fuzzell et al. (Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016) found that health professionals did not acknowledge diverse sexual orientations or gender identity issues, such as the gender-affirming process was unfamiliar to professionals. In several studies, health professionals reported their lack of knowledge and skills to provide care for SGM youth (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998; Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Porter, Lehman, Anderson and Anderson2006; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2013; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Mahdi et al., Reference Mahdi, Jevertson, Schrader, Nelson and Ramos2014; Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Vance et al., Reference Vance, Halpern-Felsher and Rosenthal2015; Shires et al., Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017). For example, Torres et al. (Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015) and Shires et al. (Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017) found that health professionals were not familiar with gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth and did not know how and when to proceed with this.

Element 2. False assumptions about SGM youth

Health professionals may have several false assumptions about SGM youth. The most frequently reported assumption in the studies was a heterosexual assumption (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998; Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016). Scherzer (Reference Scherzer2000) and Arbeit et al. (Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016) identified that heterosexual assumption led to a situation where SGM youth did not receive information that was relevant to them. Assumptions were also linked to certain SGM youths’ identities. In two studies, being gay was linked to having HIV (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998; Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002), and Lefkowitz and Mannell (Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017) found that some health professionals connected transgender youth with homosexuality, unstable mental health, placement of gender identity within female/male binary, and the presumption that transgender identity was an experimentation or stage of confusion in adolescence.

Element 3. The influence of heteronormativity on encounters with SGM youth

Heteronormativity had a negative impact on SGM youth’s experiences of care. Sawyer et al. (Reference Sawyer, Porter, Lehman, Anderson and Anderson2006), Rasberry et al. (Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015), and Arbeit et al. (Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016) indicated that without health professionals’ open acceptance of SGM people, SGM youth worried about the judgement and intolerance of health professionals, and this negatively affected an SGM youth’s disclosure to health professionals.

The influences of heteronormativity were described not only as negative attitudes and disrespectful behaviour from health professionals but also as mistreatment of SGM youth. Negative attitudes appeared as patronising (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Rasberry et al., Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016), stigmatising, or marginalising SGM youth (Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2017). Disrespectful behaviour appeared in various ways. Sometimes, health professionals underestimated SGM youths’ identities and abilities to define themselves because of their young age (Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Mahdi et al., Reference Mahdi, Jevertson, Schrader, Nelson and Ramos2014; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016). Some studies reported that when SGM youth disclosed their identity, health professionals reacted to this disclosure with varying, even intense, ways. The reports included professionals being confused (Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016), reserved (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998), or unable to interact with the SGM youth (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Mahdi et al., Reference Mahdi, Jevertson, Schrader, Nelson and Ramos2014). In Snyder et al.’s (Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016) study, SGM youth described that some health professionals ignored their disclosure, suggested the youth changing sexual orientation to heterosexual (Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016), or gave health information based on their heteronormative attitudes. Scherzer (Reference Scherzer2000) also found the latter reaction in her study. Ginsburg et al. (Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002), Scherzer (Reference Scherzer2000), and Arbeit et al. (Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016) discovered that a SGM youth’s disclosure to a health professional had, in some cases, resulted in an intense reaction from a health professional, such as leaving from the appointment room.

Heteronormativity also influenced the results of SGM youths’ healthcare. False assumptions about SGM youth led to situations that can be described as mistreatment. In seven studies, information and care to SGM youth were given only from a heterosexual aspect, and health professionals did not ask nor discuss the youth’s sexual orientation (Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2013; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016; Lefkowitz and Mannell, Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2017). Health professionals in Lefkowitz and Mannell’s (Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017) study had taken STD test samples incorrectly from transgender youth because of their confusion about the youth’s sexual organs.

Diversity-affirming care

Element 4. The considerateness of health professionals towards SGM youth

Health professionals can also work beyond the influence of heteronormativity. Their encounters with SGM youth can be described as considerate. Considerateness included both mentions from health professionals and SGM youth in the studies. Several studies found that open-mindedness was important for SGM youth (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Rasberry et al., Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Lefkowitz and Mannell, Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017), as well as equality and respect from health professionals (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016). Both professionals and SGM youth indicated that considerate health professionals can create a comfortable and safe environment for SGM youth (Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016; Lefkowitz and Mannell, Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017). Considerateness came out as health professionals’ genuine care about SGM youth and their health in Torres et al. (Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015) results. Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014) and Lefkowitz and Mannell (Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017) found that health professionals were able to identify diversity in sexuality and gender, and that health professionals supported the youth in decision-making and reaching sexual health information. In four studies, health professionals who indicated having knowledge gaps about SGM youth and their health, considered training and education about these topics to be significant (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Vance et al, Reference Vance, Halpern-Felsher and Rosenthal2015; Shires et al., Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017).

Element 5. Inclusive care of SGM youth

Torres et al. (Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015), Arbeit et al. (Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016), and Fuzzell et al. (Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016) highlighted the importance of acceptance and normalisation of diversity in sexuality and gender when organising inclusive care for SGM youth. In other studies, inclusive care was considered from three aspects: health professionals, information, and healthcare setting.

Inclusive health professionals were described as users of inclusive language (e.g. the neutral partner than the assumed heterosexual opposite) (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016), who asked which pronouns gender minority youth preferred (Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016). Several studies indicated that inclusive health professionals had knowledge about issues related to SGM youths’ health and well-being (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Rasberry et al., Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015; Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2017) and diversity in sexuality and gender (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016). Related to interpersonal skills, inclusive health professionals were described as having an ability to meet the youth sensitively (Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016). Some studies stated that health professionals needed an ability to promote open discussion with SGM youth (Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2013; Rasberry et al., Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016).

Inclusive information consisted of topics that were specific to SGM youths’ health, as well as information related to other perspectives in life. Many studies mentioned the sexual health of SGM youth as an important health information topic (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2017), as well as information about sexual orientations (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016), gender identities (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002), and mental health (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016). Ginsburg et al. (Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002), Hoffman et al. (Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009), and Arbeit et al. (Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016) reported SGM youth were willing to get information about how to talk with parents about their identities, and in the studies of Ginsburg et al. (Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002) and Arbeit et al. (Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016), SGM youth were interested about human rights issues related to them.

Inclusive healthcare settings were described in six studies. First, Ginsburg et al. (Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002), Hoffman et al. (Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009), Torres et al. (Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015), and Fuzzell et al. (Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016) mentioned that an inclusive healthcare setting needed to have a sign of inclusivity for SGM youth, such as stickers (rainbow or pink triangle), informational leaflets and posters, or SGM-oriented magazines. Second, three studies recommended that medical forms should use inclusive language (Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016) and an option for gender minority youth to define their gender identity outside of the female/male binary (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016). Third, SGM youth who participated in the study of Ginsburg et al. (Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002), Hoffman et al. (Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009), or Snyder et al. (Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016), indicated an interest in health clinics that specialised in SGM youth. However, Ginsburg et al. (Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002) and Hoffman et al. (Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009) also described how some SGM youth thought these clinics were isolating and labelling from other young people.

Discussion

This integrative review was the first describing the encounters with SGM youth in healthcare based on the existing research. This review revealed insights about the role of heteronormativity in the encounters between SGM youth and health professionals. It also identified elements of diversity-affirming care. Thus, this review discovered that the diversity of SGM youth is not always recognised, but elements supporting diversity in healthcare also exist. We suggest that further research could study how diversity-affirming care elements could be applied to the healthcare of SGM youth. The review focused on heteronormativity, which is based on feminist research (Jackson, Reference Jackson2006). Future research could focus on another feminist research approach, intersectionality. Intersectionality identifies how different identities such as race, class, gender and sexuality intersect each other, and how social power related to these identities affect to person’s status for example oppressively (Van Herk et al., Reference Van Herk, Smith and Andrew2011). Intersectionality could raise up new issues in the healthcare of SGM youth, since they can be a diverse group from other aspects besides gender and sexuality (Jackson, Reference Jackson2006).

One of the most commonly reported element of heteronormativity was a heterosexual assumption about SGM youth in healthcare (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998; Scherzer, Reference Scherzer2000; Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016). This issue has been recognised in previous literature (O’Neill and Wakefield, Reference O’neill and Wakefield2017; Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Llewellyn, Nadarzynski, Pelloso, De Souza Guilherme, Pollard and Jones2018), and its influences for SGM youth were identified in this review. One example of the influence of the heterosexual assumption in healthcare is lack of information that is relevant to SGM youth. This was reported often—a total of 11 studies in this review. Earlier literature has also found the same issue in the healthcare of SGM youth (Garbers et al., Reference Garbers, Heck, Gold, Santelli and Bersamin2017; Steinke et al., Reference Steinke, Root-Bowman, Estabrook, Levine and Kantor2017). This aspect reflects how heteronormativity still affects different fields in life including healthcare. SGM youth often have limited protective support resources (Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Carlson and Crowl2010), and if they cannot access relevant information in healthcare, they may look for it elsewhere, such as from online resources (Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network et al., 2013; Steinke et al., Reference Steinke, Root-Bowman, Estabrook, Levine and Kantor2017). The results of this review showed that SGM youth desired to have access to information related to their health and well-being from open-minded, youth-respecting health professionals (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Rasberry et al., Reference Rasberry, Morris, Lesesne, Kroupa, Topete, Carver and Robin2015; Arbeit et al., Reference Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal and Mustanski2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016). Thus, SGM youth need interactions with adults about their development, health, and well-being. Online resources can support, enable, or even enhance this interaction.

An integrative review has the potential to describe the complexity of a phenomenon from various perspectives (Whittemore and Knafl, Reference Whittemore and Knafl2005). In this integrative review, over half of the studies were conducted from health professionals’ perspectives (East and El Rayess, Reference East and El Rayess1998; Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Porter, Lehman, Anderson and Anderson2006; Kitts, Reference Kitts2010; Rose and Friedman, Reference Rose and Friedman2013; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Shoveller, Carson and Contreras-Whitney2014; Mahdi et al., Reference Mahdi, Jevertson, Schrader, Nelson and Ramos2014; Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Vance et al., Reference Vance, Halpern-Felsher and Rosenthal2015; Lefkowitz and Mannell, Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017). This shows how SGM youth were often studied from an external view, and the description of the role of heteronormativity might be, at some point, biased in this review. However, the review is the first to focus on a specific aspect in the healthcare of SGM youth, and the results give a new understanding about heteronormativity that evidently affects this youth minority group. Achieving this understanding is significant, when health professionals want to understand diversity in young people, improve their awareness of SGM youth and their challenges in life, and provide care ensuring healthy transitions to adulthood (Moon et al., Reference Moon, O’Briant and Friedland2002). The transferability of the results may be limited to other healthcare systems and settings besides American, Canadian, or United Kingdom (Polit and Beck, Reference Polit and Beck2010), since healthcare policies and economic factors related to healthcare can vary between countries. However, the results show that more attention is needed regarding how SGM youth are encountered in different healthcare systems globally, and how heteronormativity affects the equality in adolescents’ healthcare. Neither can we forget that even if the recognition of same sex relationships has advanced globally within past years (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 2017; Smalley et al., Reference Smalley, Warren and Barefoot2018), equality in healthcare for all SGM youth groups has still not achieved; for example, the healthcare of transgender youth is still missing evidence-base (World Medical Association 2015; de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Klink and Cohen-Kettenis2016). Recently, World Health Organization removed transgender identity from the category of ‘mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders’ to ‘conditions related to sexual health’ in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD11) list (World Health Organization 2018b). This shows an improvement in understanding gender diversity. However, significant work is still needed to ensure that healthcare and medical guidelines take a step to pro-trans direction in practice, and this promotes recognising the needs of transgender youth in particular.

This review showed significant issues related to transgender youth care. First, two studies defined transgender as a sexual orientation (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016), thus differing from the definition of trans as a gender identity in the literature (Smalley et al., Reference Smalley, Warren and Barefoot2018). This indicates that the understanding of gender identities may not be congruent in research yet. Second, although Vance et al. (Reference Vance, Halpern-Felsher and Rosenthal2015), Torres et al. (Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015), Lefkowitz and Mannell (Reference Lefkowitz and Mannell2017), and Shires et al. (Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017) studied transgender youth healthcare from health professionals’ perspectives, no studies focussed on transgender youths’ perceptions about healthcare. Third, several studies on SGM youths’ perspectives included transgender youth in their study (Ginsburg et al., Reference Ginsburg, Winn, Rudy, Crawford, Zhao and Schwarz2002; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Freeman and Swann2009; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Burack and Petrova2016) by grouping them together with sexual minority youth. However, grouping transgender youth and sexual minority youth together may cause prioritising sexuality over gender issues in studies (Steinke et al., Reference Steinke, Root-Bowman, Estabrook, Levine and Kantor2017). Transgender youth have some unique aspects in healthcare such as hormone treatments, gender dysphoria, right to define their gender to their medical files (World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2011); therefore, the results in this review cannot be generalised to transgender youths’ healthcare. Other gender minority youth were rarely included in the studies, and this showed a significant research gap about gender diversity among young people. There is a need for research focussing on the perspectives of transgender and other gender minority youth in healthcare and how gender norms are affected in healthcare (Steinke et al., Reference Steinke, Root-Bowman, Estabrook, Levine and Kantor2017). Furthermore, the results showed health professionals lacked knowledge about the health issues of transgender youth (Torres et al., Reference Torres, Renfrew, Kenst, Tan-McGrory, Betancourt and López2015; Fuzzell et al., Reference Fuzzell, Fedesco, Alexander, Fortenberry and Shields2016; Shires et al., Reference Shires, Schnaar, Connolly and Stroumsa2017). More attention in research should consider how health professionals’ knowledge gaps can be diminished.

The review has several practical implications. First, the results show health professionals need education about SGM youth, and the results can be used as a theoretical framework for education about diversity-affirming care. Second, health professionals can use the results in their practice when they want to be inclusive for SGM youth, for example through neutral language and not making assumptions from their patients’ gender and sexuality. Third, when healthcare policies and practices are developed into diversity-affirming, the results give examples of elements for creating inclusive healthcare settings and information for SGM youth.

Limitations

Some limitations are worth noting in this review. First, the literature search used six databases, but only 18 research articles were found to be eligible for this review. However, the literature search was planned and performed carefully. Two authors did the search systematically by following the same search strategy, and they screened and selected research articles in cooperation. Second, the wide range of research methods used in the studies may affect the analysis and results of this review. This review aimed to describe the role of heteronormativity with a broad approach and not be limited by studies with a specific research method. Furthermore, the quality appraisal of the studies was done by two authors to get an overview of the differences between studies in their quality. Third, the quality appraisal showed that several studies in this review were low in quality, thus we recommend the results are considered with a carefulness. This review was, however, describing heteronormativity for the first time with a broad approach, and the exclusion of studies with low quality was considered incongruent with this. Finally, as one inclusion criterion was English language, the review may have missed eligible studies published in other languages.

Summary

The results of this review provide a new understanding about the encounters between SGM youth and health professionals in healthcare. This understanding addresses how heteronormativity is related to these encounters and how an open-minded encounter is possible for SGM youth by giving them enough space to be diverse and support for their needs. Further research is needed about the role of heteronormativity in healthcare and the application of diversity-affirming care into healthcare practices. In addition, transgender and other gender minority youths’ voices need to be heard in research. With further research, health professionals may be able to develop their skills when encountering SGM youth without the influence of heteronormativity, give information and support that are relevant to them, and adequately understand how diversity in sexuality and gender is encountered with young patients.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Conflicts of interest

None.