Populism bears a strained relationship with democracy. It is democratic in its emphasis on popular sovereignty, but at odds with the constraints liberal democracy imposes on the exercise of that sovereignty (Taggart Reference Taggart2000). For the first time since the end of authoritarian rule, there has been a marked deterioration in the quality of democracy in a number of Central and East European countries. Some have attributed this to the ascent to power of populist strongmen (Pappas Reference Pappas2019) and have drawn attention to its contagious quality (Cianetti, Dawson, and Hanley Reference Cianetti, Dawson and Hanley2018; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2020). The erosion of liberal-democratic standards is all the more disquieting for its emergence among countries of the European Union (EU), an institution whose core values and key criteria for joining incorporate the guaranteeing of “democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities” (European Commission n.d.). The eastward enlargement of the EU was carried out with the explicit goal of completing and consolidating the transition to liberal democracy in these countries (Müller Reference Müller2013). Yet current developments within the EU indicate that while these principles might still furnish member states with a common code of conduct, the institutions of the EU lack the will to counteract decisively the contravention of these standards (Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2016; Kelemen Reference Kelemen2017). In contrast with the anti-democratic ruptures of the Cold War years (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016), these recent “illiberal turns” were pursued in the name of the people and justified on the basis of legitimate parliamentary majorities.

The actions of illiberals in power have affected the quality of democracy in several ways (Taggart and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Taggart and Kaltwasser2016). Yet while populism has played a central role in the appeal and strategy of these actors—and is almost omnipresent in the accounts concerning them—the current prominence of populism should not overshadow the importance of nativism when deciphering illiberal phenomena (Art Reference Art2020). In Hungary and Poland, two particularly egregious examples of autocratisation within the ostensibly democracy-preserving structures of the EU, both populism and nativism should be deemed the cardinal principles guiding the enactment of the “illiberal playbook”.Footnote 1

We examine the nature, scope, and consequences of the illiberal turns enacted by Fidesz in Hungary since 2010 and Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland since 2015. Focusing on their policy output, we distinguish between specific populist and nativist policy objectives and between different gradations of illiberal policy change. In doing so, we provide a nuanced understanding of what the illiberal playbook entails in practice and how non-compliance with liberal-democratic standards unfolds.

We thus seek to further the debate on autocratisation in two ways. First, we identify ways in which both populism and nativism figure in the policymaking of illiberals in power. The adherence to a semblance of constitutionalism and democratic legitimation has brought together the likes of Orbán in Hungary, Kaczyński in Poland, Erdoğan in Turkey, and Chávez in Venezuela (Weyland Reference Weyland2020). Yet each of these illiberal executives preserves ideological specificities which can be singled out and interpreted. Second, by disaggregating the illiberal playbook into distinct gradations, we elaborate on the notion that illiberal governments are using legalism to kill liberalism (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018; Castillo-Ortiz Reference Castillo-Ortiz2019). While the legalistic façade of some illiberal changes might obscure declines in the quality of democracy, other changes can be classified as outright illicit by the standards of liberal constitutional democracy. We therefore question the notion of “perfect legality” attributed to the machinations of illiberal governments (Weyland Reference Weyland2020). In this regard, shared principles such as those agreed at the EU level provide readily available benchmarks for the evaluation of autocratisation, as they both normatively and legally bind their signatories.

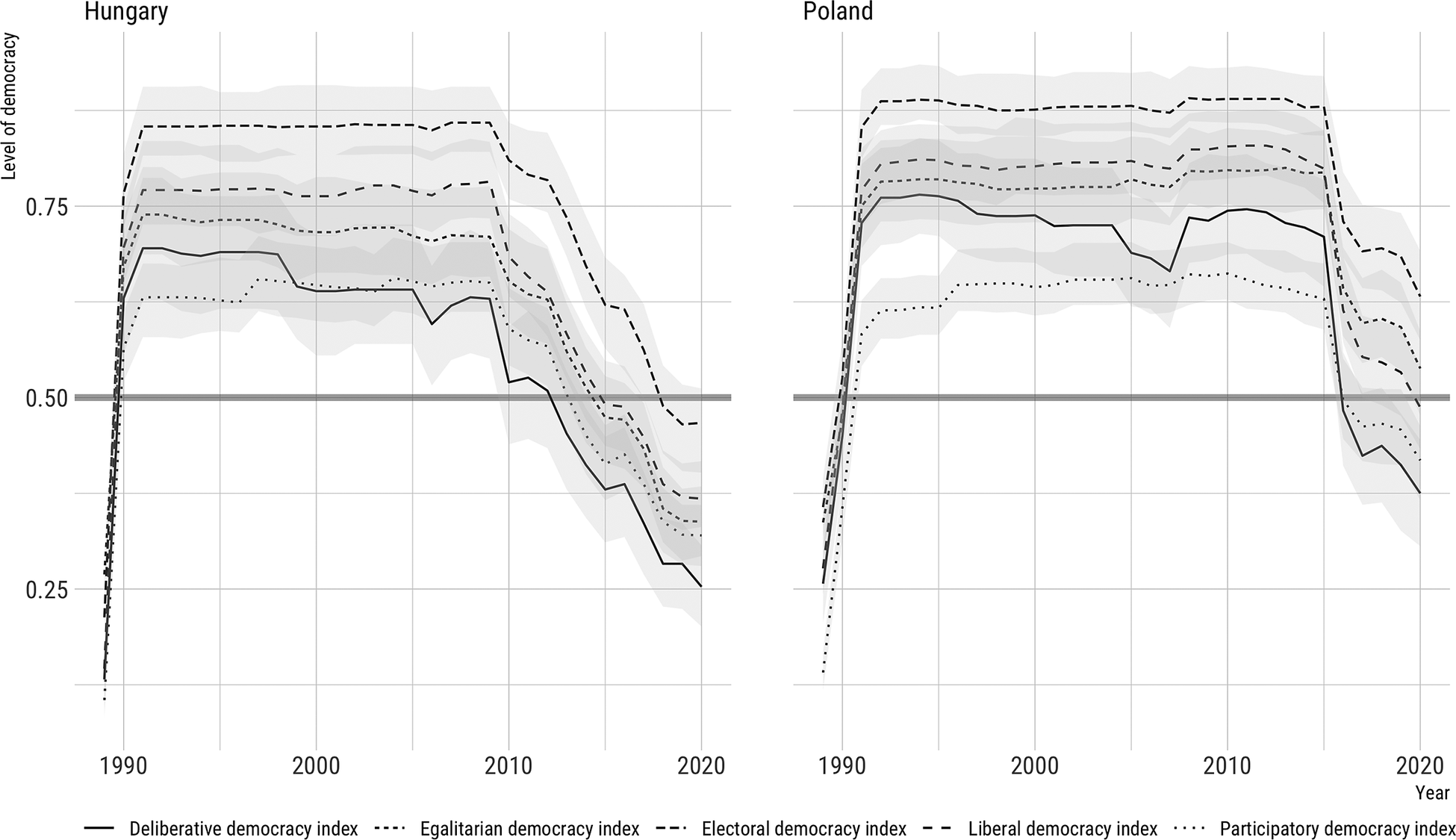

Hungary and Poland offer two illustrations of what populist radical right parties—specifically, a radicalised populist right-wing mainstream—can do when, having acquired outright power, they set their countries on an illiberal trajectory.Footnote 2 Since 2010, Viktor Orbán has imposed a programme of institutional change on Hungary, facilitated by Fidesz’s two-thirds supermajority in parliament (Herman Reference Herman2015).Footnote 3 After losing a second successive election in 2011, Jarosław Kaczyński, leader of PiS, looked to Hungary for political inspiration. After regaining power in 2015, PiS engaged in an “accelerated and condensed” (Puddington and Roylance Reference Puddington and Roylance2017) version of Fidesz’s illiberal playbook: dismantling the rule of law, subordinating the separation of powers to executive decisionism, and curbing the civil liberties of minorities in the interests of a national majority. These changes have led to a marked decline in the quality of democracy—gradual in Hungary and precipitous in Poland (figure 1). This process has also laid bare the institutional and political problems the EU experiences in responding to the subversion of democracy in its midst (Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2016; Batory Reference Batory2016). The EU has become trapped in an “authoritarian equilibrium,” in which internal political competition and inadequate conditionality relating to the provision of funding serves to entrench illiberal enclaves established within it (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2020).

Figure 1 Decline in the quality of democracy, Hungary and Poland

Source: Coppedge et al. 2021

The article proceeds as follows. First, we relate illiberal governance to the broader literature on democratic backsliding and autocratisation, and explain how populism and nativism fit into this picture. Second, we introduce our schema of illiberal policy change, defining the parameters of the illiberal playbook in the form of three concepts: forging, bending, and breaking. Third, we apply our conceptual schema to the cases of autocratisation in Hungary and Poland, and assess the nature and implications of illiberal policymaking in the two countries. We conclude by summarising illiberal changes and highlighting the utility of our framework in broader perspective.

This yields two key findings. First, a parliamentary supermajority is not a necessary condition for the implementation of illiberal policies. Both cases demonstrate that, where some checks and balances are still in place, illiberals in power may proceed by bending liberal principles rather than breaking them outright. Through acts undertaken to disable or bypass the scrutiny of judicial institutions prior to the promulgation of illiberal policies, those policies could often be presented as de facto legitimate. Second, illiberal policymaking is ideologically founded. Populism’s contempt for pluralism, minority rights, and procedural complexity informs the focus of illiberals on subverting, bypassing, or simply removing legal hurdles to executive decisionism, while nativism provides them with a policy-oriented rationale and set of discursive resources for identifying and sanctioning those “enemies of the (native) people” whose minority interests are to be excluded. We conclude that the cases of Hungary and Poland demonstrate the complex and differentiated character of the illiberal turn: while there is an illiberal playbook, there is more than one way to deploy it.

The Illiberal Turn

To explain what we mean by an illiberal turn, we must first characterise what it is a turning away from. Magyar and Madlovics (Reference Magyar and Madlovics2020, 9) have argued against the uncritical application of Western-derived measures of democratisation—and its reverse-teleological counterpart, autocratisation (Cassani and Tomini Reference Cassani and Tomini2018)—to the post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. They contend that these political systems are dominated by “informal and personal relations”—such as the dismantling of the separation of branches of power—are in reality simply “a logical adjustment of formal institutions to patronalism.” Their call for an alternative framework for analysis also carries a set of implicit hypotheses about the greater vulnerability of post-communist systems to what, from the perspective of Western liberal democratic benchmarks, constitutes democratic erosion.

Three decades after the transition from democracy, it remains unclear to what extent other post-communist countries are succumbing to this “logical adjustment” and indeed to what extent the “predominant framing” (Dawson and Hanley Reference Dawson2019, 6) of democratic backsliding is applicable at all. Furthermore, the emergence of populist parties and concomitant challenges to the integrity of democratic Western European democracies challenges the stark distinction Magyar and Madlovics (Reference Magyar and Madlovics2020, 8) draw between “Western” and “Eastern” civilisations with respect to the regulation and operation of political systems. Accordingly, our conceptual point of departure is the common set of liberal-democratic principles—the “obligatory syntax of political thought” (Crăiuţu cited in Trencsényi et al. Reference Trencsényi, Kopeček, Lisjak Gabrijelčič, Falina, Baár and Janowski2018, 209)—on which the post-1989 political order was founded, and whose normative superiority was, at least at the time, accepted by the majority of political actors. This consensus was based on three pillars: first, an economy in which rational individuals were free to pursue their interests, with minimal intervention on the part of the state; second, the creation of a pluralistic public sphere guaranteeing individuals free and active participation in civil society and in the political process; third, cultural pluralism, with minority interests and values protected from the tyranny of the majority. Countries undergoing transition to democracy were expected to transpose these principles into domestic constitutional arrangements, creating the impersonal institutions necessary to protect against autocratisation. Accession to key international institutions—in particular the EU, with its demanding and legally-binding list of criteria for joining—would be both the capstone and guarantor of democratic consolidation.

As Bill and Stanley (Reference Bill and Stanley2020, 390) have argued with reference to the Polish case, the practical application of this consensus “[constricted] the scope of government … within a narrow set of bounds permitted by a particular conception of good governance.” Insofar as they challenge an overly technocratic politics of administration, illiberal actors like populist radical right parties have been seen as a possible corrective for democracy as well as a threat (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde, Kaltwasser, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012). While they disrupt the foundations of constitutional liberalism, they also prompt mainstream parties to respond to the challenges they pose.

The maintenance of this dynamic relies on the assumption that liberal-democratic systems exert sufficient constraints on populist radicalism to prevent it undermining the integrity of the system as a whole. These constraints include internal actors such as mainstream parties, civil society and social movements, constitutional courts and the media, and external actors such as international organisations (Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Reference Cristóbal and Taggart2016). But what happens when illiberal actors can count on absolute majorities in parliament? Until recently, populist radical right parties in consolidated European democracies were only part of governing coalitions and often lacked sufficient leverage to realise the full potential of illiberal government (Akkerman and de Lange Reference Akkerman and de Lange2012; Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015; Pirro Reference Pirro2015; Fallend Reference Fallend, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012). In recent years, this has changed.

Contemporary cases of departure from the liberal-democratic consensus are commonly subsumed under the rubric of “democratic backsliding.” While some see this as an “involuntary reversal” (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019), others regard it as a strategic and agent-led process (Bakke and Sitter Reference Bakke and Sitter2020). In the post-communist case, it also tends to suggest a reversal of the smoothly teleological “transition paradigm” (Carothers Reference Carothers2002) by which these countries are assumed to have democratised in the first place. Yet the quality of democracy in these countries is more variegated than the broad notion of consolidation would suggest (Stanley Reference Stanley2019); and democratic consolidation across the region remains beset by structural flaws: corruption and the weakness of the judiciary (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2015); the concentration of economic and media power (Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018); and the weak entrenchment of liberal values as robust social norms (Dawson and Hanley Reference Dawson and Hanley2016). Rather than inadvertent democratic decline, in Hungary and Poland we see the strong hand of agency. Illiberal governments explicitly rejected the ideological predicates of liberal democracy (Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány and Varga2019; Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020) and learned the art of finding the cracks in this political system from emulation of other cases (Hall and Ambrosio Reference Hall and Ambrosio2017; Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018) and from obstacles identified during their own previous stints in government (Stanley Reference Stanley2016). We characterise the ongoing process of autocratisation in Hungary and Poland as a deliberate attempt on the part of the populist radical right to establish an illiberal political regime.

At this point, a clarification of the relationships between illiberalism, populism, and nativism is required. As Art (Reference Art2020) has argued, the popularity of the term “populism” has led in recent years to a considerable obfuscation of this phenomenon. This has had two consequences. Empirically, it has led to an overemphasis of the populist attributes of certain political parties, movements, and leaders at the expense of other core aspects of their ideology, such as nativism. Normatively, it has enabled nativists to evade responsibility for illiberal actions by attributing their motives to the populist goal of realising the majoritarian promise of democracy. This critique matters in two respects. First, it requires us to maintain good definitional hygiene at the borders of our concepts so that we might better understand their interactions. Second, it enjoins us to pay more attention to what populists do, and less attention merely to what they say. The latter of these goals is achieved through our focus on policy actions—the substance of illiberal governance—rather than campaign rhetoric. Our analysis is therefore motivated by the purpose of disaggregating and evaluating the importance of populist and nativist elements in the governance of illiberal actors.

In line with the ideational current in the literature, we adopt a minimal understanding of populism (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Stanley Reference Stanley2008) that posits a moral antagonism between a pure, authentic, legitimate people and a corrupt, illegitimate, inauthentic elite. Populism, thus understood, is highly context-dependent, and produces a range of dissimilar leaders, movements, and parties across those contexts (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde, Kaltwasser, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012). As such, populism, as an ideology or set of ideas, directly informs the political practice of its advocates, but not necessarily in the same way. Nativism, on the other hand, is less ambiguous in its manifestations: it is inherently a radical exclusionary form of nationalism placing the native people at the heart of an organic ethnocultural project, whereby elements identified as part of the “outgroup” are perceived as a fundamental threat to the nation state (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). While both compatible and coexisting within the illiberal ideology of the populist radical right, the elements of populism and nativism are distinct both conceptually and in practice, and deserve separate attention in their own right.

Parties which were populist in opposition may simply discard populism following electoral success, satisfying themselves with the spoils of office. Yet to fully realise populism’s promise of restoring the majoritarian aspect to democracy, it is not enough simply to win power. Liberal democracy, understood as “a democratic electoral regime, political rights of participation, civil rights, horizontal accountability, and the guarantee that the effective power to govern lies in the hands of democratically elected representatives” (Merkel Reference Merkel2004), erects a daunting set of barriers to the pursuit of majoritarian executive decisionism. Pluralistic media pose a threat to the populist’s monopoly on legitimate truth. The legitimacy of political opposition is inimical to the populist’s conception of political order.

This is where illiberalism comes in. The clash between the monist, majoritarian predicates of populism and the experience of having to govern amid such constraints means that sooner or later a reckoning with the system is inevitable. To persist in power without simply discarding the populist ideological premises they employed to gain that power in the first place, the populist radical right must capture, dismantle, or hollow out instruments of scrutiny and control such as legislatures, courts, electoral agencies, central banks, and ombudsmen; establish control over the media outlets they can colonise; and alter electoral rules to their own advantage (Bugarič Reference Bugarič2019). It must, in other words, engage in deliberate practices of illiberal governance. In the case of EU member states, the subversion of these standards involves the undermining not only of the domestic legal order but also the overarching legal architecture of the EU, whose laws and norms should in principle provide a set of safeguards against democratic breakdown and autocratic consolidation (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Taggart and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Taggart and Kaltwasser2016). While illiberals in power may attempt to preserve the vestiges of constitutionalism for the sake of appearances, by bypassing the structural constraints imposed by liberal democracy they deeply alter the nature and functions of its institutions (Castillo-Ortiz Reference Castillo-Ortiz2019).

Populist actors that come to power in a liberal democracy on the basis of the valorisation and pursuit of a singular popular will (Weale Reference Weale2018) must eventually enter into conflict with a political system designed to thwart that objective. Those who combine populism’s concern for the popular will with a nativist ideology have additional incentives to challenge anti-majoritarian political systems. As Mudde (Reference Mudde2007) observes, the ideology of the populist radical right also incorporates authoritarianism and nativism. A populist radical right party will, on entering power in a liberal democracy, encounter not only a system of checks and balances designed to constrain the executive, but also a broad range of protections for minorities that cannot easily be reconciled either with the authoritarian’s understanding of social order or with the nativist’s limited and exclusionary definition of the people. In order to attain this, nativists will reduce the freedoms enjoyed by those they cannot control, attack the dissenting parts of civil society, and curb their rights and liberties.

In essence, nativism in power seeks to fulfil political goals and exclude foes and “the other” from the body politic. If removing the pluralism from politics is the ultimate goal of illiberals in power, the process of autocratisation by which this proceeds is strongly facilitated by populism and nativism. In turn, illiberals in power become more dependent on this ideological toolkit, as the concentration of political power—on which autocratisation depends—requires justification through the constant identification of enemies of the people or enemies of the nation both within and without the polity. Populism and nativism are not simply elements of these parties’ political appeals, but intrinsic to the logic of their illiberal governance.

Subverting Liberal Democracy: A Playbook

To remove the liberalism from liberal democracy, illiberals in power nullify the rule of law by ensuring that the judiciary has limited control over the executive and the legislative branches, resulting in the weakening of its power to constrain government action and protect individual rights and freedoms. To preserve their democratic mandate, illiberals in power tilt the playing field in favour of the incumbent across election cycles through the capture and politicisation of state institutions and the exploitation of an unequal share of resources, such as access to and control over public media (Dresden and Howard Reference Dresden and Howard2015). How, though, does this happen?

We propose a tripartite typology that distinguishes between three gradations of illiberal policy change with respect to the rule of law. The first of these types we term forging. Here, change occurs in accordance both with the letter and with the spirit of the law. The purpose is to enact change in areas of policy that have largely or wholly been de-contested by liberal mainstream parties. The concept of forging reflects the fact that illiberal actors often seek to make changes that break substantially with a mainstream consensus without necessarily challenging the rule of law. These areas of change will vary by context. In the case of populist radical right parties, there is likely to be an emphasis on morality (e.g., gender identity, protection of the foetus, LGBTQI+ rights) and memory politics (e.g., historical revisionism, lustration) where they can exploit the majoritarian appeal of illiberal alternatives to a politically mainstream but socially unpopular consensus. In the cases we examine, there is significantly greater scope for change within the rule of law, as these are policy areas over which higher-order institutions such as the EU have little direct influence.

At the other end of the scale is breaking, in which legislative actions are contrary to both domestic and international law, constituting a direct breach of the constitutional order and of liberal-democratic principles. Taking actions that are unambiguously illegal is a risky strategy for illiberals. Pragmatically, illiberal actors need to ensure that their hold on power cannot be undermined by the actions of those capable of holding them to account for unlawful activity. Ideologically, they must take care to stay on the right side of the divide that separates them from anti-democratic actors.

The illiberals’ desire for change often leads them to operate at the limits of what the law permits. We distinguish here a third type of policy change, which we term bending. This type of change connects the ideological radicalism of forging with the procedural radicalism of breaking. Under bending, policy change is consistent with the letter of the law, but in contradiction to its spirit. It involves the reinterpretation or disabling of existing legislative constraints in ways that are not procedurally illegal but that defy or subvert liberal-democratic norms. Bending the law allows populists to maintain a link between their call for a break with “politics as usual” and their claim to operate within the constraints imposed by legalism.

By unpacking the different aspects of the liberal playbook, we differentiate between forms of change that do not breach the law and those that do, rather than treating all changes implemented by illiberals as a single package of illegal moves. Amid situations of radical reconfiguration of the liberal-constitutional design, legal changes create “an aspect of normalcy in an otherwise constitutionally abnormal situation” (Castillo-Ortiz Reference Castillo-Ortiz2019). We argue that, as long as illiberal policymaking does not contravene the letter of the law, illiberals in power will be able to portray their actions as fully legitimate. However, forms of “constitutional malice” or “intolerant majoritarianism” (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018) are themselves also in violation of the liberal-democratic credo and deserve to be recognised as such.

The consequences of these strategies are twofold. On the one hand, illiberals in power seek innovative ways to circumvent the constraints imposed by their systems. On the other, their tactics limit the scope of action of supervising actors (Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Reference Cristóbal and Taggart2016; Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2016; Kelemen Reference Kelemen2017) whose attempts to exercise control of illiberal executives are routinely challenged by those executives as politically motivated. As a result, illiberals in power are often able to implement illiberal policies through processes that are superficially reminiscent of legalism (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018). We contend that closer attention should be paid to these seemingly less egregious forms of illiberal change in order to pre-empt further moves away from democracy. In our study, these changes are indeed part of the illiberal playbook and fall under the rubric of forging and bending.

The forging, bending, and breaking schema offers a comprehensive way to conceptualise the processes by which the illiberal playbook is enacted, but it does not entail any specific logical order, nor the eventual attainment of the same illiberal goals. As a matter of fact, none of these types of illiberal policy change presupposes foregoing autocratic attempts or breakthroughs. The ways in which the playbook is implemented are indeed conditioned by context-specific resources and constraints, but these are not necessarily dependent upon prior deterioration of democratic quality. Illiberal changes can occur within a liberal-democratic framework; the logic of autocratisation is not so much concerned with the point of departure, but with the several processes leading to autocracy (Cassani and Tomini Reference Cassani and Tomini2018). In the Hungarian and Polish cases, a significant rupture with the previous system was a necessary prelude to the implementation of other aspects of illiberal change. Accordingly, we move in each case from breaking, to bending, to forging. Due to space constraints, our analysis does not set out to be exhaustive but rather to capture the most illustrative and representative instances of illiberal policymaking in greater detail than offered by the existing literature on autocratisation.

Despite arguments on the lack of a single template for European democracy, there are not only historically shared understandings of how liberal democracy should work within this context, but also a variety of fundamental civil, political, economic, and social rights attached to EU citizenship, which supranational institutions are called on to protect (Müller Reference Müller2013). For our purpose, autocratisation is therefore assessed against binding supranational sources like EU treaties upon which all member states have voluntarily agreed. The Treaty on European Union (TEU) provides one such example of a cardinal document encapsulating the liberal-democratic credo:

The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail. (Article 2 TEU)

While national constitutions also routinely enshrine these standards, their subversion by illiberals in power undermines the extent to which they may be used as reliable measures of accepted democratic standards, hence our use of a benchmark that defines shared democratic standards at the supranational level. In the following sections, we present the background of illiberal governance in Hungary and Poland, the scope and consequences of the illiberal playbook, and the populist or nativist nature of the policies implemented.

Illiberal Rule in Hungary and Poland

Fidesz returned to power amid a series of political and economic crises that left the Hungarian socialist and liberal parties in ruins. The party gained 52.7% of votes in the 2010 elections, which translated into a two-thirds majority in parliament. The Orbán government used this supermajority to implement a far-reaching legislative overhaul. At the heart of this project was the introduction of the 2011 Fundamental Law, which entered into force in 2012 and formally replaced the 1949 Constitution—a text already heavily amended in 1989. As a result of these changes, most domains can now only be regulated through cardinal acts and two-thirds majority votes. Decisions taken by the Orbán government will therefore be very difficult to alter or repeal in the future in the absence of a very broad consensus. Fidesz has tailored these changes not only to cement its hold over the country, but also to outlast any potential defeat (Bánkuti, Halmai, and Scheppele Reference Bánkuti, Halmai, Scheppele and Tóth2012). The party consolidated its grip over Hungary through the 2014 and 2018 elections. Fidesz again secured supermajorities in parliament following electoral processes that were deemed free but not entirely fair (OSCE 2018).

With the prospect of enacting the new constitution in mind, Fidesz suspended a series of checks ensuring independent oversight over its activity, which might have prevented straightforward approval of the text. These pre-emptive changes had a significant impact on the functioning of the constitutional and electoral system, and substantially undermined the independence of the judiciary.

The Fundamental Law was eventually approved on April 18 and promulgated on April 25, 2011. Freed from previous constraints surrounding constitutional drafting, in particular the need to engage in meaningful debate with opposition parties, Fidesz hastily adopted a text imbued with national and social conservatism. In declaring the 1949 Constitution null and void, Fidesz founded the 2011 constitution on “a theoretical mess” (Bánkuti, Halmai, and Scheppele Reference Bánkuti, Halmai, Scheppele and Tóth2012) as the new document was itself adopted on the procedural standards set by the previous text and amendments.

After a short stint in coalition government (2005–2007), PiS won 37.6% of votes in the 2015 Polish elections and embarked on a route explicitly inspired by the Hungarian example. The 2015–2019 PiS government enacted a deliberate and painstakingly sequenced assault on the constitutional structure, the power and autonomy of discrete institutions of state, and the rights and freedoms of individuals and social groups. While it lacked the legislative supermajority enjoyed by Fidesz, PiS had no compunctions about taking action that breached both the letter and the spirit of the law. Unable to promulgate a new constitution, PiS worked to undermine the existing one through the political capture of the Constitutional Tribunal, and then the attempted purging and repopulating of the judiciary. The colonisation of the institutions of judicial review and control facilitated further cases of bending and breaking the law, but also made it possible to legitimise further departures from liberal-democratic norms by giving them the stamp of constitutional propriety. The effect of these changes was to erode the fragile but functional pluralism that had emerged over the previous three decades (Bill and Stanley Reference Bill and Stanley2020). PiS’s capture of public media undoubtedly abetted its electoral success in 2019, in which it increased its share of the vote to 43.6%.Footnote 4

Enacting the Illiberal Playbook

Breaking

The implementation of a media package by the Orbán government in 2010 was motivated by the need to impose control over the public debate. While the passage of this package was procedurally legitimate given Fidesz’s two-thirds majority in parliament, it nevertheless breached Hungary’s treaty commitments to freedom of expression and pluralism as enshrined in Article 2 TEU, and the protection of media freedom and pluralism afforded by Article 11 of the EU Charter of Basic Rights.Footnote 5 First, the government established a Media Council to oversee all media content and police an opaque notion of “balanced” information. The four members of the Media Council and its president are elected by a two-thirds majority for a renewable nine-year term, an arrangement that fails to guard against the concentration of power and is thus inimical to political neutrality. The Media Council has the power to impose major sanctions, an instrument that creates a significant incentive for self-censorship by media outlets unaligned with those in power, thereby infringing the obligation of liberal-democratic media environments to offer balanced coverage. Finally, the Media Act stipulates that the Hungarian News Agency is the exclusive news provider for public media outlets.Footnote 6 These changes have taken place within a context of poor media pluralism and partisan ownership of commercial broadcasters (Bátorfy and Urbán Reference Bátorfy and Urbán2020), which leaves the internet as the only platform for independent information.

During its second consecutive mandate (2014–2018), and especially after the peak of the “migrant crisis” in 2015, Fidesz adopted a number of measures with discriminatory implications. At least two sources bind Hungary to the protection of human rights: the 2011 constitution (through Article Q on obligations under international law and Article XIV on non-Hungarian asylum seekers) and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU (right to asylum). The Orbán government has repeatedly breached these obligations. First, it amended the Asylum Act and the Act on State Borders (2016) to enable the Hungarian police force to push back asylum-seekers within eight kilometres of the Serbian-Hungarian and Croatian-Hungarian borders.Footnote 7 Second, the government amended its Criminal Code to introduce the criminalisation of border crossing. Third, the already restrictive criteria providing the grounds for detention of non-citizens (Third-Country Nationals Act and Asylum Act) were tightened further in 2017 by a law introducing mandatory detention for all asylum-seekers (including children) for the entire length of the asylum procedure.Footnote 8 Fourth, in June 2018, the government swiftly adopted a bill, aptly dubbed “Stop Soros,” in reference to a presumed plan by the Hungarian-American financier and philanthropist to transplant migrants from Africa and the Middle East. The bill targeted people and organisations “facilitating illegal immigration” (punishable with one year of imprisonment)—the ulterior motive of which was to criminalise humanitarian NGOs and curb migrants’ access to aid. All these changes should be considered in breach of both the letter and spirit of international law, as testified by the pronouncements of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the European Court of Human Rights.

As of 2018, habitual residence in a public space has been made constitutionally illegal. The resulting criminalisation of homelessness and poverty raises questions not only at the moral level, but also in relation to human rights and liberal-democratic principles, as enshrined in constitutional protections for human dignity (Article II) and the provision of adequate housing for all (Article XXIII). Unsuccessful attempts by the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court to block this legislation support our contention that this is a fundamental breach of Hungarian law.

The last instance of breaking for the Hungarian case relates to the discrepancy between the letter of the Fundamental Law and governmental policymaking in the sphere of higher education. The amendments introduced by Act XXV/2017 (also known as Lex CEU for the conditions specifically imposed on Budapest’s Central European University) were introduced as part of a broader war on liberalism, and a specific crackdown on groups and institutions supported by Open Society Foundations (OSF), the international network founded by George Soros. Lex CEU requires that any foreign-funded university in Hungary may only operate once the Hungarian government and the government of the source country sign an intergovernmental agreement, requiring that such institutions conduct academic activities in the source country. While the conditions and deadlines proved taxing, CEU managed to abide by all requirements in a timely fashion. However, the Orbán government postponed a decision on meeting criteria, projecting CEU into a state of legal uncertainty (Enyedi Reference Enyedi2018), and ultimately forcing it to relocate activities to Vienna. The very provisions of this law are an evident and deliberate breach of the liberal order.Footnote 9

In the Polish case, the capture of the Constitutional Tribunal was of paramount strategic importance. Judicial review played a crucial role in repelling PiS’s previous attempts at illiberal reform during the short-lived government of 2005–2007. Having learned from that experience, PiS set about ensuring that its plans would not be stymied by resistance from the Tribunal—Kaczyński explaining that it was necessary to eliminate “legal blocks on government policies aimed at creating a fairer economy” (Sobczak and Pawlak Reference Sobczak and Pawlak2016). Even if PiS continued to insist that these actions were constitutional, they contravened the principle that the Tribunal controls the constitutionality of legislation. PiS enacted their capture of the Tribunal first by paralysing it as an effective body of judicial scrutiny, then by colonising it and using it as an instrument of executive “validation” of PiS’s further actions.

The first step in the paralysing of the Tribunal was the refusal by PiS-aligned President Andrzej DudaFootnote 10 to administer the oaths of office to three lawfully elected Tribunal judges. Anticipating an electoral defeat, the outgoing coalition government of the conservative-liberal Civic Platform and the agrarian-conservative Polish People’s Party had appointed five new judges to the Constitutional Tribunal. This attempt at court-packing was rebuffed by the Tribunal, which ruled that the outgoing parliament only had the right to appoint three new judges to the Tribunal, as the other two vacancies fell during the term of the new parliament. However, in anticipation of an adverse ruling, the new PiS-dominated parliament passed a resolution ostensibly invalidating the election of all five newly elected judges, on the basis of which President Duda refused to administer the oaths of office to the three legally appointed judges, instead swearing in five new judges elected by the new parliament.

Subsequent judgments of the Constitutional Tribunal found that the newly elected parliament was not empowered to invalidate the elections of the three judges properly appointed by the outgoing parliament, nor to appoint new judges in their place. However, neither the government nor President Duda recognised the legitimacy of these judgments, and the three “judge-doubles” would ultimately be assigned to panels of the Tribunal after the replacement of outgoing Tribunal president Andrzej Rzepliński—in a process that itself breached the law—with PiS appointee Julia Przyłębska. At this point, PiS’s capture of the institution was complete (Sadurski Reference Sadurski2019).

The consequences of the capture of the Constitutional Tribunal are explored below. However, before its capture of the Tribunal, PiS issued several amendments to the law governing its composition and operations. Aspects of these amendments were subsequently adjudged unconstitutional. In three cases the government, which controls the publication of the Journal of Laws (Dziennik Ustaw, the official record of legal acts, publication in which is necessary for these acts to be considered a source of law), refused to publish adverse judgments, declaring them to have been issued improperly. This is in direct defiance of Article 190.2 of the Polish Constitution, according to which judgments of the Tribunal are to be published “immediately.”

A further breach occurred in the case of PiS’s attempts to purge and replace members of the Supreme Court by lowering the retirement age for judges. One of the judges thus affected was First President of the Supreme Court, Małgorzata Gersdorf, to whom the government and president insisted the law must apply despite the fact that the six-year tenure of the First President is protected by Article 183.3 of the Constitution. PiS was ultimately forced to backtrack on this following an adverse ruling by the European Court of Justice.

Looking at the Hungarian and Polish cases, we note that Fidesz and PiS made differential use of instances of breaking. While the Orbán government resorted to this modality of illiberal policymaking to establish control over the media, and to confront and subdue “aliens” and political enemies during its second consecutive term in power, PiS concentrated its efforts on the dismantling of constitutional checks and balances. As far as our distinction between populist and nativist policymaking is concerned, we can thus assert that Fidesz has made predominant use of breaking to attain nativist goals; the enemies targeted while in power are political foes (i.e., Soros and progressive NGOs) and other “aliens” by nativist standards (i.e., immigrants and homeless people).Footnote 11 Conversely, PiS has broken the letter of the law to pursue populist goals and cement its power over the Polish system.

Bending

One of the very first steps taken by the Orbán government was to change the terms for constitutional drafting. Before 2010, any constitutional change was subject to a process of debate in which all parties represented in parliament participated. This provision was first introduced in 1995 to safeguard minority interests at a time when the prospect of replacing the 1989 Constitution had become more concrete. Using its two-thirds majority, Fidesz amended this rule to circumvent potential opposition from other parties (Bánkuti, Halmai, and Scheppele Reference Bánkuti, Halmai, Scheppele and Tóth2012). Although in procedural terms no law was violated here, the removal of this rule clashes with the principle that a constitution should be founded in a pluralistic consensus. Instead, the new Hungarian constitution was hastily passed without cross-party debate.

Other examples of bending involved the disabling of the Constitutional Court. While attained on contentious but lawful grounds in light of Fidesz’s supermajority, these changes defy the independent functioning of the judiciary. First, the government altered the procedure for the appointment of judges of the Constitutional Court, repealing nominations by the majority of parliamentary parties and simply leaving appointments to a two-thirds vote in parliament. Second, the parliament heavily restricted the scope of judicial review in the crucial area of fiscal policy, allowing the Constitutional Court to raise issues on budgetary matters only under very exceptional circumstances (Halmai Reference Halmai2012). Third, a constitutional amendment increased the number of judges of the Constitutional Court from eleven to fifteen, enabling the Orbán government to pack the Court with seven loyalist judges between 2010 and 2011. This allowed the government to establish political control over it.Footnote 12

The National Election Commission, the key institution for administering elections and ruling on the admissibility of referendums, was subjected to similar treatment. Two laws determined that its members were to be elected by a majority vote in parliament following each general election (Act LXI/2010) and that seven core members were to be elected for a term of nine years by a two-thirds parliamentary vote (Act XXXVI/2013). This made it possible for the Orbán government to alter its composition and capture it politically.Footnote 13

Fidesz also used its majority to circumscribe religious freedoms, passing Act CCVI/2011 on the Right to Freedom of Conscience and Religion and the Legal Status of Churches, Denominations and Religious Communities of Hungary. Act CCVI/2011 defined strict criteria for the legal recognition of churches and their financial support, originally requiring a twenty-year presence in Hungary and one hundred years of religious activity internationally. These criteria arbitrarily reduced the number of recognised churches from more than three hundred to fourteen, eventually including thirty-two by 2012. In its adoption of discretional requirements, the government bent the principle of religious freedom, as enshrined in Article VII of the new constitution, offering privileged status to some communities while excluding others.

Within the remit of constitutional freedoms, Article XVII of the Fundamental Law also states that “Employees, employers and their organisations shall have the right … to take collective action to defend their interests, including the right of workers to discontinue work.” Yet in practice the 2010 amendment to the law on strikes determined minimum levels of service to be guaranteed by public service providers (public transport, communication, electricity, and water supply). As minimum levels of provision are regulated by law only in the case of public transport and postal services, contending parties must agree on a definition or resort to court decisions. By passing this amendment, the Orbán government did not ban the right to strike but imposed onerous hurdles to its fulfilment.Footnote 14

As part of its crackdown on progressive and opposition forces, moreover, the Orbán government put forward a package on the Transparency of Organisations Receiving Support from Abroad, which was eventually adopted in June 2017 (Act LXXVI/2017). The bill was presented as a legal means to prevent money laundering and terrorism, imposing certain categories of NGOs to register as “foreign-funded organisations” when receiving annual foreign funding above HUF 7.2 million (approximately €20,000). In practice, however, it was seen to target humanitarian NGOs in receipt of financial support from OSF.Footnote 15 In a later provision, included in Act XLI/2018, a 25% tax was imposed on those NGOs “supporting immigration,” putting progressive civil society organisations under disproportionate pressure. These moves do not alter freedom of association and expression in a technical sense but pose strenuous conditions for the activities of non-aligned NGOs.

Finally, the Orbán government introduced a decree in 2018 banning courses in gender studies. Though this decision was rationalised as a cost-cutting measure on the basis of low enrolment figures, it affected only two institutions—the aforementioned CEU and Eötvös Loránd University—and reflected Fidesz’s aversion to “genderist ideology.” The functional effect of the ban on gender studies degrees is in tension with the provisions of Article X of the constitution, which guarantees scientific and artistic freedom, and freedom of teaching.

In the absence of a supermajority, PiS were unable to alter the competences of constitutional bodies through changes to the constitution. Instead, they sought to exploit constitutional provisions that give the legislature the responsibility of organising the functioning of constitutional bodies through ordinary statute. Some of these changes were arguably in breach of the constitution, but at the moment of their promulgation were not unambiguous enough to be classified as examples of breaking, although in some cases were retrospectively found to be so.

The most prominent example was the succession of amendments used to paralyse the Constitutional Tribunal. Article 197 of the Constitution states that “the organization of the Constitutional Tribunal, as well as the mode of proceedings before it, shall be specified by statute.” PiS exploited this clause with alacrity. Amendments to the law on the Constitutional Tribunal passed in December 2015 required it to achieve a two-thirds majority for judgments when sitting in full panel (Article 10.1), making it more difficult for the Tribunal to strike down legislation subsequently passed by a PiS-controlled parliament. In the same bill, PiS introduced a new rule specifying that, in issuing its judgments, the Tribunal must strictly adhere to the order in which submissions to the Tribunal were received. If new cases were to be examined in the order of their submission, PiS would be able to establish further legislative faits accomplis before the Tribunal could rule on the constitutionality of the legislation that enacted those changes.

The strategy of using ordinary legislation to bend the Constitution was also evident in the case of changes to the law on the National Council for the Judiciary (KRS), the body that appoints and disciplines judges. Article 187.1 of the Constitution sets out the composition and mode of appointment of the KRS, among which there are fifteen judges. The Constitution does not specify who chooses the KRS judges, but in accordance with a settled norm they had previously been chosen by the judiciary. Amending the law on the KRS in December 2017, PiS instead granted parliament the right to appoint them, meaning that of the twenty-five members of the institution, twenty-three were now to be appointed by the legislature, increasing legislative (and by extension, executive) power over the judiciary.

In one case, the need to gain control of a key constitutional body was circumvented by setting up a parallel institution by statute. The new Council of National Media (RMN) was endowed with the competence to appoint or dismiss presidents of public media and members of supervisory or management boards (Article 2.1). This was previously the prerogative of the National Council of Broadcasting and Television (KRRiT), a constitutional organ charged with “safeguard[ing] the public interest regarding radio broadcasting and television” (Article 213.2, Constitution of 1997). Since the Constitution does not reserve powers of appointment to KRRiT, the transfer of these prerogatives to the RMN does not constitute a breach of the law. However, the use of a parallel institution to usurp functions previously exercised by a constitutional body is indubitably an example of bending the law away from previously observed and respected norms.

The setting up of the RMN was a clear case of change to the laws governing the operation of institutions to achieve a discrete goal. This ad hoc approach was also evident during reforms to the Supreme Court. When PiS realised that the nomination of a new chief justice of the Supreme Court was going to be delayed by the blocking tactics of “recalcitrant” judges on the court, they swiftly passed an amendment to the statute on the Supreme Court that decreased the number of judges needed to propose the five candidates from which the president would choose a new chief justice.

Amendments to the Law on the Organisation of Common Courts served a similar function. Among other prerogatives, these changes granted the Prosecutor General (who is also the Minister of Justice) the power to appoint and dismiss the presidents of all courts within six months of the passage of the amendment, after which he would retain the power to dismiss court presidents for “serious or persistent failure to comply with official duties” (Świętochowska Reference Świętochowska2017). What is striking about this is not just the clear scope afforded for creative and arbitrary interpretation of “serious or persistent failure,” but the one-off character of the six-month transitional period. This provision effectively granted Minister of Justice Zbigniew Ziobro temporary discretionary powers to purge the presidents of common courts without being bound by the law. Again, this is a clear case of bending to achieve a specific goal under the pretence of conducting a systematic reform.

Some overlaps can be ascertained between the Hungarian and Polish cases, particularly with respect to disabling the constitutional courts and the politicisation of other organs of control. However, the Orbán governments benefited from the greater scope afforded by a supermajority and used it to serve populist aims (i.e., tilting the Hungarian system in their favour) as well as nativist goals (i.e., waging war against non-aligned NGOs, religious minorities, and other dissenting parties). Given standing constraints, PiS was forced to be more creative in its attacks on independent institutions, but overall used bending to promulgate policies predominantly responding to a populist rather than nativist logic.

Forging

There are few unambiguous instances of illiberal change that do not contradict either the spirit or letter of the law. In the Hungarian case, we focus on two specific provisions of the new constitution pertaining to the framing of the family and the foetus.

In Article L, the Fundamental Law elaborates on the family “as the basis of the survival of the nation” and defines marriage “as the union of a man and a woman”’; moreover, it states that “Hungary shall encourage the commitment to have children.” The formulation of marriage in terms of “traditional” heteronormative family should be interpreted as an instance of forging. While clearly restrictive and conservative in spirit, the indirect ban on same-sex marriage is not in contrast with the EU legislation. Indeed, provisions for registered partnerships for same-sex couples, attained in 2009, are still in place in Hungary.

A similar reasoning applies to Article II, which envisages protection of the foetus “from the moment of conception.” Although this elaboration might negatively affect the right of, and access to, abortion (especially in the form of conscientious objection by health professionals), the 1992 Law on the Protection of the Foetus is still in place and allows women to terminate their pregnancy up to twelve weeks and, in certain circumstances, up to twenty-four weeks.

PiS was able to pursue an illiberal path without bending or breaking the law at the intersection of state and civil society. PiS has consistently evinced a mistrust for organisations that operate outside the state’s sphere of influence, seeing an independent and pluralistic civil society as a Trojan horse for foreign interests. Accordingly, the government used instruments of funding and oversight to enact a shift away from liberal initiatives. To achieve this, it created two institutions, the Public Benefit Committee and the National Institute of Freedom–Centre for the Development of Civil Society, to centralise the coordination and monitoring of the cooperation between the state administration and civil society organisations.

The structure of these bodies gives the government significant scope for influencing the disbursement of state grants to civil society organisations, with the Public Benefit Committee led by a member of the government and possessing significant powers to control the actions of the National Institute of Freedom, which is the body responsible for administering grants. The extent of government oversight, and the fact that the statute of the National Institute of Freedom explicitly singles out the need to maintain and disseminate “local and national traditions rooted in [Poland’s] Christian heritage” (Article 24.3[4]), led to concerns about the narrowing of the scope of government support for civil society organisations. As Sadurski (Reference Sadurski2019) notes, even prior to the creation of these two institutions, there were already clear signs of a shift away from organisations with agendas contrary to the government’s ideological preferences: bodies concerned with protecting the rights of women, asylum seekers, and refugees have been denied funds, and the Council for Counteracting Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Intolerance was liquidated.

Amid this broader shift towards entrenching conservative values, there were significant shifts away from liberal pluralism in certain areas. While PiS rebuffed one civic initiative that sought to delegalise and criminalise abortion entirely, they encouraged and gave initial parliamentary support to a bill that sought to ban so-called “eugenic” abortions: those carried out in cases where the foetus is irretrievably malformed or terminally ill. PiS parliamentarians also applied to the Constitutional Tribunal for a ruling on whether the current abortion law was compatible with the Constitution. The deliberately vague protection of the “right to life” in the Polish Constitution (Article 38) does not provide a clear point of orientation, and with powers in this area reserved for member states, Poland is not bound to a liberal interpretation of reproductive rights. The resolution of this issue in January 2021 with the issuing of a ruling upholding the essence of the complaint demonstrated how bending and breaking may pave the way for forging. The political capture of the Constitutional Tribunal made it into an instrument that PiS could use to achieve an outcome it was not able to achieve in the legislature.

For Fidesz and PiS, instances of forging evinced a common emphasis on traditional moral values and opposition to the prevailing forces of cosmopolitan liberalism, reflecting these parties’ conservative and nativist ideological predicates. The absence of direct EU regulation over certain domains of policy by the EU makes it easier to pursue nativist objectives in those areas, but the relatively few cases of forging point to the existence of significant formal constraints on the scope for illiberal policymaking, helping to explain why these governments predominantly opted for bending and breaking.

Conclusions

Autocratisation, like democratisation, is a process. To study autocratisation is to study process as well as outcome; to understand not only where these countries are going and why, but how. This is a research field that encompasses numerous points of focus and requires a substantial methodological toolkit, including policy studies, legal analysis, content analysis of political appeals, and causal analysis of the relationship between illiberal supply and demand. The chief contribution of this article is the development of a typology that captures the different types of actions that illiberals in power take in their subversion of liberal democracy, and does so in a manner conducive to further comparative work.

In our study, we have shown that illiberals in power, like the democratising elites before them, do not proceed from the same starting point, nor do they face the same sets of constraints and opportunities. These circumstances have a significant impact on their capacity to implement illiberal policy changes, but not necessarily a decisive one. In Hungary, the chief constraint to action was lifted at the outset through Fidesz’s achievement of a supermajority in the 2010 election. Possessing the capacity to rewrite the country’s constitution is perhaps the most powerful instrument at an illiberal’s disposal; it makes it possible to exploit the majoritarian energies of a founding moment while imposing a set of asymmetrical constraints on your opponents. However, as the Polish case illustrates, the absence of a constitutional majority is not necessarily a decisive constraint. The ease with which Poland’s institutions were subverted and colonised by the forces of illiberalism bears out Dawson and Hanley’s points about the hollowness and weak embeddedness of both liberal-democratic institutions and the norms that sustain them (Dawson and Hanley Reference Dawson and Hanley2016). Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic further attest to the fragility of legal constraints. Fidesz exploited the opportunity afforded by the declaration of a state of emergency to confer open-ended powers of decree on the executive. These powers were exploited with alacrity for “non-emergency” purposes (e.g., outlawing changing gender on documents after birth) and later rescinded—mostly following public and international outcry—to vindicate the “democratic” profile of the Orbán government. Rather than declare a state of natural disaster and push back the May 2020 presidential election, PiS instead pushed through changes to the electoral law to facilitate postal voting in spite of previous Constitutional Tribunal rulings that major changes to the electoral law could not be undertaken less than six months prior to the relevant election. Illiberals in power can then introduce, remove, amend, or extend emergency powers at the sole whim of the majority.

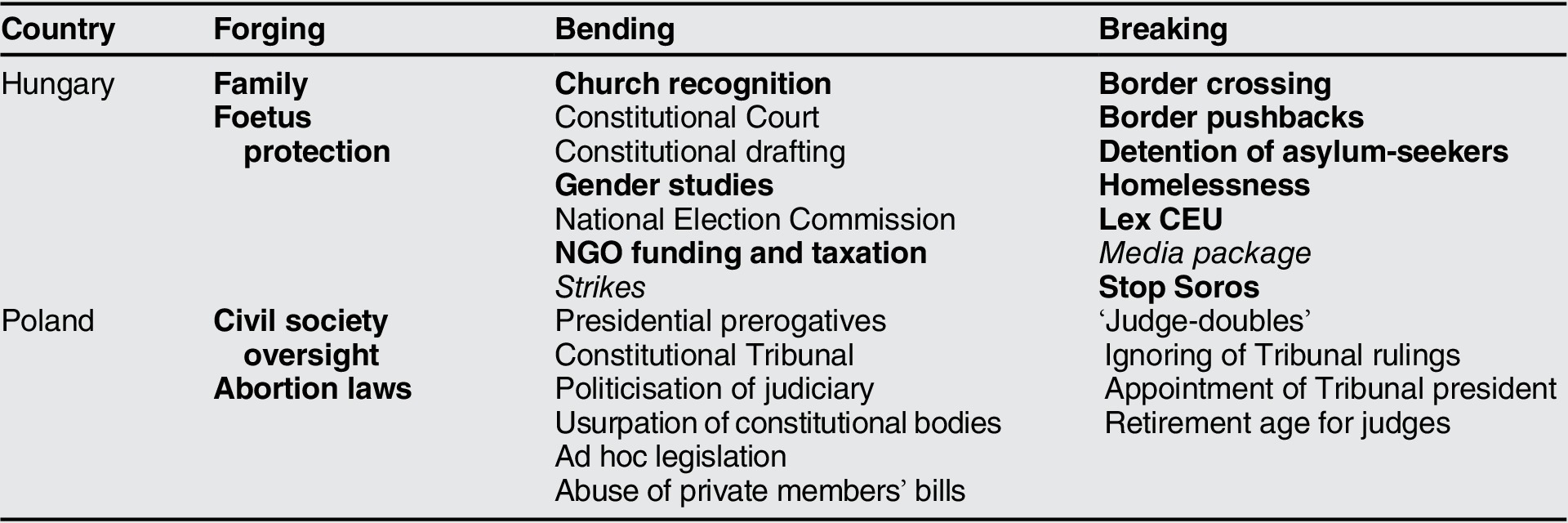

While the examples we have provided in this article are not exhaustive, they are representative of the scope of forging, bending, and breaking in each case (table 1). Where forging is concerned, illiberal change was relatively thin on the ground due to the rather narrow scope of policy areas in which liberal rights are not given unambiguous protection by existing constitutional articles or European legislation. In Hungary, there was somewhat greater scope for illiberal forging due to the national-conservative character of the 2011 constitution. Notably, however, Fidesz and PiS both resorted to forging to pursue nativist objectives. Fidesz also made more extensive use of breaking to achieve a variety of (predominantly) nativist policy goals, while in the case of PiS this was largely an expedient to break institutional deadlocks that could not be overcome by constitutional change. By comparison, PiS’s approach to illiberal policy change was dominated to a greater extent by bending the law. This condition was imposed by its lack of a constitutional majority, although PiS made—and continues to make—increasingly bold use of ordinary legislation to subvert constitutional controls.

Table 1 Summary of illiberal changes, per country

Note: Populist changes in regular font; nativist changes in bold. Changes in the law on strikes and regarding the media landscape (in italics) are seen to respond to both populist and nativist goals.

With the sole exception of nativist policies implemented within the framework of forging, PiS’s illiberal policymaking has been concerned with accomplishing procedural and structural changes that resonate with our notion of populist objectives. Fidesz’s illiberal playbook made greater and more frequent use of nativist policymaking compared to PiS. In any case, it is clearly not possible to understate the relevance of the populist ideological component of the governance of illiberal actors in the two countries.

Two main conclusions can be drawn from our comparison of Hungary and Poland. First, there is no single path to illiberal democracy. Illiberals in power have a common set of goals with respect to the ways in which they seek to change the political system and its institutions from the inside, but objective conditions such as the size of their majorities, the strength of the opposition, and the capacity of institutions to resist colonisation and subversion mandate varying strategies. Once illiberal policies are successfully enacted in ways which exploit the imprecise or ambiguous wording of legislation, this enables illiberal governments to vindicate subsequent illiberal changes as procedurally lawful (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018). This then complicates responses to processes of autocratisation, since what were once assumed to be inadmissible actions are no longer unambiguously sanctionable. At the same time, there is no evidence of perfect legitimacy in the policymaking of illiberal governments, since their playbook frequently indulges in cases of breaking. It is to these occurrences that the democratic publics and overseeing actors must train their eye and start looking for dangerous signs. Second, despite the existence of different paths to autocratisation, illiberals in power nevertheless rely on a common playbook; a set of strategies to attain policy results that are rooted in ideological goals. Our distinctions between types of illiberal policy change therefore nuance the notion of a common pathway to autocratisation in Hungary and Poland, and in Central and Eastern Europe more broadly, showing that even parties that are often likened to each other may follow distinct paths of their own.

The successes of Fidesz and PiS not only in governing, but in governing on their own terms, refute two common wisdoms about populists: that they invariably fail once confronted with the responsibility of governing, and that they can only succeed by moderating their most controversial ideological stances. Both parties achieved re-election without backtracking on their implementation of the illiberal playbook, their core nativist agenda, or the ancillary populist worldview in which they couch that agenda, and both have fundamentally altered the nature of the political systems in which they and other political forces operate. As such, Hungary and Poland are at the vanguard of a new type of political system; one which preserves the procedural vestiges of democracy while hollowing out its liberal content. If subversion of democracy used to take place via coups or electoral fraud, protagonists of the “third wave of autocratisation” (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019) are more likely to assert a licence for executive aggrandisement on the basis of a strong democratic mandate, exploiting legal and procedural ambiguities (Landau Reference Landau2013), engaging in strategic manipulation of the electoral process (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016), and deploying subtle but cumulatively powerful repressive measures against civil society and the media (Huq and Ginsburg Reference Huq and Ginsburg2018). Moreover, in the face of persistent violations of European values and rules, supranational institutions have failed to act as “guardians of the treaties” and to enforce their predicates (Müller Reference Müller2013; Kelemen Reference Kelemen2017), in effect depriving the EU of its external constraining power on illiberal governments hijacking democracy (cf. Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Reference Cristóbal and Taggart2016).

The tripartite schema of forging, bending, and breaking that we have applied to the cases of Hungary and Poland may also fruitfully be extended to other cases. Indeed, it is plausible to assume that other illiberal political forces may follow suit. At the time of writing, both Fidesz and PiS are discussing the creation of a pan-European political structure explicitly aimed at countering the hegemony of the liberal consensus. If such a structure were created, it would provide resources for policy learning, facilitating forging; intellectual support for the establishment of counter-hegemonic norms in the interpretation of legislation, facilitating bending; and mechanisms of mutual insulation from legal consequences at the EU level, facilitating breaking. Both the goal and the means of this form of autocratisation are attractive to illiberal actors, who seek to preserve the majoritarian legitimacy in democracy while jettisoning the liberal constraints on majoritarianism. The damage wreaked on the democracies of Hungary and Poland in recent years is testament to just how easily and variably this form of autocratisation can be achieved.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Duncan McDonnell and Annika Werner for their invaluable feedback on a very first draft of this manuscript. They also wish to extend their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of their work and to Michael Bernhard for his exceptional editorship.