Introduction

Constitutional and apex courts decide significant cases. The procedure through which judges resolve controversies is said to be defined by a formal institutional framework in constitutions and statutes. Nonetheless, legal scholarship has often overlooked the importance of another component of the ‘rules of the game’: informal institutions.

Although traditionally associated with negative connotations, particularly in civil law countries,Footnote 1 informal institutions may have a dual role, both undermining and bolsteringFootnote 2 formal legal frameworks. Whilst legal scholarship on informal institutions is at a nascent stage, political scientists have evidenced the manner in which informal institutions shape the behaviour of different critical actors within political systems.Footnote 3

In recent years, there has been a growing body of literature analysing informal institutions and their operation in courts in aspects such as judicial selection/informal networks/patronage,Footnote 4 judicial discipline,Footnote 5 the impact of informal institutions on gender equality within the judiciary,Footnote 6 and how informal institutions may enhance the authority of critical judicial playersFootnote 7 such as Chief JusticesFootnote 8 or impact de facto judicial independence.Footnote 9

Even though the study of informal institutions within the judiciary is increasing,Footnote 10 scholarship exploring informal institutions within judicial decision-making remains scarce.Footnote 11 Informal institutions have occasionally been touched on in studies pertaining to the internal functioning of courts,Footnote 12 and some case studies of informal institutions in the judiciary have also shed light on their impact on judicial decision-making.Footnote 13 Yet, there are inherent methodological difficulties in observing and studying unwritten rules, which often occur in secret deliberations behind closed doors,Footnote 14 between small groups of judges, who have an esprit de corps incentive not to break the secrecy.

This article centres on informal institutions in judicial decision-making by exploring the informal institutions prevalent in the Polish Constitutional Tribunal. The study identifies 14 recognised informal rules, highlighting five key institutions influencing the Tribunal’s decision-making process: indicative votes; tentative conference deliberations; informal supermajority rules for invalidating legislation; prohibitions on altering Panel membership; and negotiation rules for informal voting.

The contribution of this article to the literature is twofold. First, through a case study, it will show that constitutional courts, even when operating in civil law jurisdictions where informality is traditionally mistrusted, develop a vast array of informal institutions that often determine case outcomes. Said institutions perform a role similar to formal rules, such as statutory law or internal court-written regulations. They form a substantive framework for the procedural rules of the game, providing clarity and generating consistency and efficiency. This role is illuminated in times of polarisation, when the elected branches may attempt to amend the formal rules of the game or nominate loyal judges, which may erode informal institutions that conflict with achieving specific political outcomes. As a second contribution, the article will explore the effects of internal polarisation on informal institutions. We hypothesise that internal court polarisation negatively impacts compliance with preexisting informal institutions or may lead to their reshaping. Using a simplified typology of polarisation in constitutional courts, the case study suggests that judges appointed prior to internal polarisation saw informal institutions as less consistently applied after such polarisation occurred.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The second section introduces the Polish Constitutional Tribunal, explains the unique set of conditions that make it ideal for a case study, and describes the methodology followed by the study. The third section describes the results of the study: it first provides an overview of the formal procedure of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal. Then it outlines the informal institutions detected through the interviews. It presents a formulation of the specific rules, their category within a typology of informal institutions, the actors bound by the rule, and potential informal sanctions adduced. Finally, by distinguishing between internal and external polarisation regarding constitutional courts, the fourth section explores the effects of polarisation resulting from the Polish constitutional crisis on adherence to the informal institutions previously identified. Conclusions are presented in the final section.

Methodology

Why study informal institutions within the Polish Constitutional Tribunal?

The Polish jurisdiction in the selected period is an ideal model for an analysis of informal institutions. We will outline the Tribunal’s evolution and finish by providing three arguments for its comparative value.

Before World War II, Polish legal scholarship favoured the creation of a Constitutional Tribunal based on the Kelsenian model.Footnote 15 Subsequent to World War II, the establishment of a constitutional court was considered contrary to the basic principles of the communist state –the unity of state power and the leading role of the communist party.

Significant political events, social unrest, and strikes led by the Solidarność movement led to the imposition of martial law in 1981. Attempting to overcome the political difficulties, the regime made concessions. In 1985, the Constitution was amended to establish a Constitutional Tribunal. However, the Tribunal’s powers were severely limited, and the Sejm could reject a ruling declaring a law unconstitutional.

Despite the limitations in its institutional design, the Tribunal began playing an important role in 1989 after the fall of communism. From the principle of government, the Tribunal derived many principles of law and recognised them as binding constitutional principles.

The Tribunal would reemerge in the 1997 Constitution as a 15-member body with nine-year staggered terms. The Tribunal was granted guarantees of independence,Footnote 16 and the former power of the Sejm to revoke its decisions was eliminated.Footnote 17 In Kelsenian fashion, the Constitutional Tribunal was tasked with adjudicating the constitutionality of laws, international agreements, and other normative acts. The Tribunal was also vested with the power to decide on the compatibility of laws with international agreements and regulations with laws. In addition, the Tribunal resolves competence disputes between the central constitutional bodies of the state, adjudicates the compatibility of the goals or activities of political parties with the Constitution, and rules on the temporary incapacity of the President to discharge the duties of the office.

From 1997 to 2016, the Tribunal developed the foundations of a new constitutional axiology, constructing constitutional standards. It developed the content of constitutional principles, the scope of human rights, and a rich doctrine on the separation of powers. Through the years, the Tribunal underwent a systemic evolution from a restrained negative legislator to a more active adjudicator of the Constitution.Footnote 18 The Constitutional Tribunal became a constitutional court with an established prestige and rich jurisprudence.Footnote 19 Even on controversial and contentious issues such as the permissibility of abortion,Footnote 20 vetting (lustracja),Footnote 21 or ritual slaughter,Footnote 22 criticism of the Tribunal’s rulings did not undermine the constitutional consensus determined by those rulings.

That state of affairs would change drastically. In 2015, the terms of five judges were set to expire. The Sejm, still dominated by a majority from the incumbent Platforma Obywatelska party, was to appoint three of the new judges. The newly elected Sejm, holding a majority from Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (subsequently PiS), was to appoint the other two. Platforma Obywatelska, together with Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe (PSL), attempted to appoint all five judges prematurely.Footnote 23 PiS-nominated President Andrzej Duda refused to swear in the new judges. Once the new Sejm was installed, PiS retaliated by voiding the appointment of all judges and appointing five of its own. Although the Constitutional Tribunal intervened, upholding the validity of three judges rightfully appointed by Platforma Obywatelska and considering that the newly PiS-dominated Sejm could validly appoint two of its own,Footnote 24 the PiS-dominated presidency and Sejm refused to publish and implement the judgment.

Although the Constitutional Tribunal was able to function, excluding illegitimately appointed judges temporarily, PiS had begun a frontal assault on the Tribunal through legislation in 2015.Footnote 25 By December 2016, the expiring terms of several judges had led to the Tribunal formally starting to function with the illegitimately appointed judges. As many scholars pointed out, the Tribunal eventually lost its independent function, becoming an enabler of the ruling party.Footnote 26 The new Tribunal would cease to rule on the basis of well-established rules of interpretation of the Constitution,Footnote 27 and was accused of repeatedly failing to apply the rules of procedure that guarantee its independence.Footnote 28

Proceedings before the Tribunal ceased to be a place for the settlement of fundamental constitutional issues. Constitutional disputes were transferred to the international arena, as evidenced by dozens of rulings of the Court of Justice of the European Union and the European Court of Human Rights. The loss of independence of the Constitutional Tribunal was acknowledged by the European Court of Human Rights in Xeroflor v Poland.Footnote 29 Although the 2023 election gave rise to a coalition of parties ousting PiS from power and generated a debate on repairing the Constitutional Tribunal, that is an ongoing discussion.

The brief history of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal presented above suggests it would be an ideal jurisdiction for studying informal institutions within judicial decision-making. In the first place, although some recent studiesFootnote 30 have attempted to research informality and decision-making in jurisdictions with public deliberation modelsFootnote 31 that provide crystal-clear information on informal institutions, at least from conference deliberations, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal follows the standard model of closed deliberations. Hence, the study offers an opportunity to gain critical insights into the functioning of informal institutions in closed deliberation systems. It also allows for the diversification of research on informal judicial institutions that so far has centred on other jurisdictions, primarily the US.Footnote 32

Second, after it transitioned from a post-communist regime to a full democracy with the adoption of the 1997 Constitution and its 2004 accession to the European Union, Poland developed robust institutions.Footnote 33 Analysing this jurisdiction could offer valuable insights to other similar European constitutional courts in jurisdictions upholding Western liberal values. Finally, the Polish constitutional crisis, occurring at the end of the studied period, offers the opportunity to analyse a natural court subjected in its later years to the intense polarisation fostered by political players and internal factions, which may erode the informal institutions that courts have abided by to accommodate decisions favouring partisan policy preferences. Thus, it will allow preliminary testing of the impact of polarisation on compliance with said institutions.

Methods, period, and sample selection

This article relies on interviews to gather information on informal institutions. A methodology relying on interviews can provide accurate insights into internal non-disclosed institutions that structure judicial decision-making. Some have observed that interviews may help ‘report and track processes that remain invisible, incomprehensible, or poorly detailed in judicial decisions’.Footnote 34 However, scholars have noted that judicial elites may constitute a hermetic hierarchy, distrusting outsiders attempting to gain insight into their decision-making processes.Footnote 35 Apex and constitutional judges pose unique challenges in identifying, selecting, and gaining access to respondents.Footnote 36 Nonetheless, since Perry’s seminal work employing interviews with legal elites to assess agenda-setting in the US Supreme Court,Footnote 37 a growing list of scholars has begun employing interviews to delve into several internal featuresFootnote 38 of constitutional and apex courts, such as decision-making,Footnote 39 deliberation mechanics,Footnote 40 the publicity of discussions,Footnote 41 and the use of foreign and comparative law in judicial decision-making.Footnote 42

Regarding informal institutions, Dunoff and Pollack employed interviews to assess the internal functioning of international courts,Footnote 43 and Kranenpohl studied the internal functioning of the German Constitutional Court.Footnote 44 Partially relying on semi-structured interviews, Rivera studied the interplay of informal institutions surrounding voting mechanics in jurisdictions under supermajority rules.Footnote 45 The literature employing interviews to unveil unseen informal institutions in the judiciary is growing.Footnote 46

Period. Internal informal judicial institutions are based on interactions between reduced deliberative groups. Following earlier studies, we examine a natural court,Footnote 47 also referred to as a member-constant court, featuring prolonged interactions among the exact composition of judges.Footnote 48 While such an approach does not allow for accounting for evolutionary changes that occurred over time, it does allow a more precise mapping of the extant institutions in the analysed period.

The Polish Constitutional Tribunal is a 15-member body. Fewer than 15 judges are available to interview due to death, sickness, or unwillingness to participate in interviews for scholarly studies. Although functioning in its current configuration since the entry into force of the 1997 Constitution, earlier periods of the Tribunal present methodological challenges such as lessened availability of judges – death, sickness – and arguably less reliable information since the passage of time may not allow retired judges to recall informal institutions accurately. We deemed that studying contemporary compositions of the Tribunal could be more fruitful.

The 2012-2016 period was designed to avert the risk of joint treatment of informal institutions, which possibly may have eroded or changed after the 2016 changes to the Tribunal’s composition. Furthermore, covering periods subsequent to 2016 would generate a high probability of noncooperation, given the notably polarised environment and factional dynamics of judges appointed in the 2015-onwards period.

Sample selection and interview mechanics. We approached judges who exercised office in the natural court period mentioned above. Six judges agreed to the interview, and one non-interviewed judge conveyed and supervised information pertaining to the study; hence, there were seven independent sources of information. Thus, roughly half of the natural court for the selected period participated in the study.Footnote 49

Being aware of standard methodological concerns regarding the participants, such as confidentiality breaches, ethical conflicts, and other issues typically affecting the sincerity of answers,Footnote 50 we took several measures. Interviews were conducted by M.A. Rivera. Judges were assured that anonymity would be preserved.Footnote 51 Relying on similar studies,Footnote 52 judges were informed that verbatim quotes, if employed, would be attributed abstractly, identified by sequential letters, randomly varying in both gender and letter.Footnote 53 Interviews were only recorded if consent was provided and subsequently transcribed. The modal time for interviews was one hour, with a range of 50 minutes to 1.30 hours.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted according to the interview guide available in Appendix A. We included a brief explanation of the fact that previous researchers employing the interview methodology have faced the problem of judges’ lack of awareness of the nature of informal institutions, leading to unfruitful answers.Footnote 54 The dynamic consisted of a brief introduction and questions subdivided into four sections. Three sections pertain to the informal powers of critical judicial players, and one concerns the effects of polarisation on informal institutions. Questions were usually followed up with requests for examples, potential breaches, and reactions to said breaches.

The following sections will present an outline of the formal procedure at the Polish Constitutional Tribunal, provide a definition of informal institutions and their theoretical distinctions with border terminology, and reveal an in-depth mapping of informal institutions uncovered by the study. It will subsequently centre on five major informal institutions to explore their emergence and underlying functioning.

Informal institutions in the Polish Constitutional Tribunal

Understanding the formal procedure

Understanding the informal rules within the Polish Constitutional Tribunal requires knowledge of the formal regulations governing its procedures. We will briefly outline the formal procedure within the legal framework that was valid during the analysed period.Footnote 55

The Tribunal had competences similar to those of other formal Kelsenian constitutional courts. Most cases pertained to abstract judicial review (wniosek konstytucyjny), constitutional questions referred by the ordinary judiciary (pytanie konstytucyjne), and individual constitutional complaints on the infringement of rights (skarga konstytucyjna).Footnote 56

Once the Constitutional Tribunal received a complaint, it was classified as a motion, legal question, constitutional complaint, or other.Footnote 57 The applications of entities with unlimited legal standing (Articles 191.1 and 192 of the Constitution) and of the National Council of the Judiciary, as well as constitutional referrals from courts, were verified by the President regarding admissibility. If there were formal deficiencies, the President requested their correction or they would be returned. In the case of entities with limited legal standing (Article 191, paragraphs 1 and 3-5 of the Law) and constitutional complaints, the President appointed a judge to verify their admissibility. If deemed inadmissible, the judge dismissed the case. Such dismissals could be appealed to a three-judge Panel.Footnote 58

Admissible motions, legal questions, or constitutional complaints were referred by the President, in order of receipt (Article 25 of the Law), to a Panel of judges appointed by the President.Footnote 59 A three-member Panel analysed sub-statutory acts, while a five-member Panel dealt with challenges to statutes (Article 25 of the Law). The Tribunal functioned en banc when resolving ex ante normative control cases by request of the President of the Republic or in cases deemed as particularly complex – o szczególnej zawiłości – as provided by Article 35.1 of the Law.

The President of the Tribunal appointed the Judge-Rapporteur and determined the Panel composition (Article 25 of the Law).Footnote 60 The Tribunal was required by law to resolve cases through a hearing (Article 59 of the Law) in the presence of the parties.Footnote 61 The Tribunal’s President called hearings at the petition of the Panel’s President. Prior to the official deliberations, the Presiding Judge could call for preliminary deliberations to discuss specific issues (Article 24.2 of the Internal Regulations).Footnote 62

During the hearing, the applicant and the remaining participants presented their arguments and evidence (Article 61 of the Law). When the matter was sufficiently discussed, the Presiding Judge closed the hearing (Article 65 of the Law), stating the date and place at which a verdict would be announced (Article 27.1 of the Internal Regulations). Verdicts were announced after a secret conference deliberation immediately following the hearing (Article 31.1 of the Internal Regulations) of the respective deciding Panel (Article 67 of the Law), subject to a simple majority (Article 68 of the Law).Footnote 63 The Law provided that, while the Tribunal resolves the case after deliberation, the written decision with the specific legal justification could be issued up to a month after the official announcement occurred (Article 71.3).Footnote 64

Defining informal institutions

According to Helmke and Levitsky, informal institutions are rules ‘created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels’.Footnote 65 In turn, North considered that enforcement by legal institutions, such as courts, was an important distinction separating formal and informal institutions.Footnote 66 Some scholars have also posited that informal institutions are better defined as non-legally enforceable rules, not created through lawmaking institutions, regardless of their legality.Footnote 67 Since informal institutions are generally associated with unwritten rules lacking formal legal enforcement, some scholars employ the terms informal acts, practices, or rules, often using them interchangeably.Footnote 68

Analysing informal judicial institutions, Kosař and co-authors defined acts as single instances of performed actions, and practices as routinised types of behaviours,Footnote 69 devoid of the perception of bindingness that characterises institutions. Routinised practices could evolve into institutions accepted as binding social facts. This study focuses on institutions, while single occurrences such as acts, and even multiple non-binding occurrences such as practices – e.g. ‘judges conducted deliberation after lunch’ – are not considered.

As to distinguishing informal institutions from informal rules, the relative consensus is that institutions may be defined as systems of rules.Footnote 70 Furthermore, informal institutions are often described as part of the rules of the game.Footnote 71 Although a theoretical distinction could be attempted,Footnote 72 the lion’s share of the scholarship analysing informal judicial institutions uses both terms equivalently.Footnote 73 For the purposes of this study, we will employ informal institutions/rules interchangeably, while avoiding the terms act and practice unless referring to isolated or non-normative and non-institutionalised occurrences.Footnote 74

A final problem pertains to the usage of said terminology by judicial members. Civil law countries have a conflicting relationship with unwritten law, a category closely related to informal institutions.Footnote 75 Research has often conceptualised informality as an undesirable divergence from written law.Footnote 76 Recent scholarship centring on unwritten constitutionalism and constitutional conventions showed that actors in civil law countries, particularly in Hungary and Poland, mistrust the normative value of informal sources, hence seeing them at best as normatively irrelevant.Footnote 77 Often, to avoid the terminological implications, unwritten sources of law are given different terminological labels.Footnote 78 Those findings led to the expectation that judges of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal would not directly employ labels of informality.

During the semi-structured interviews, judges were unaware that several institutions were informal, describing them with language that was proper to normative binding rules. Some of the judges showed discomfort with categorising the behaviour of the Tribunal as ‘informal’. They were much more comfortable with classifying said behaviour with alternative expressions such as ‘practices’, ‘usages’, ‘traditions’, or ‘the way we used to do things’. The usage of said labels is consistent with the negative connotations of unwritten sources of law previously described.

A mapping of informal institutions

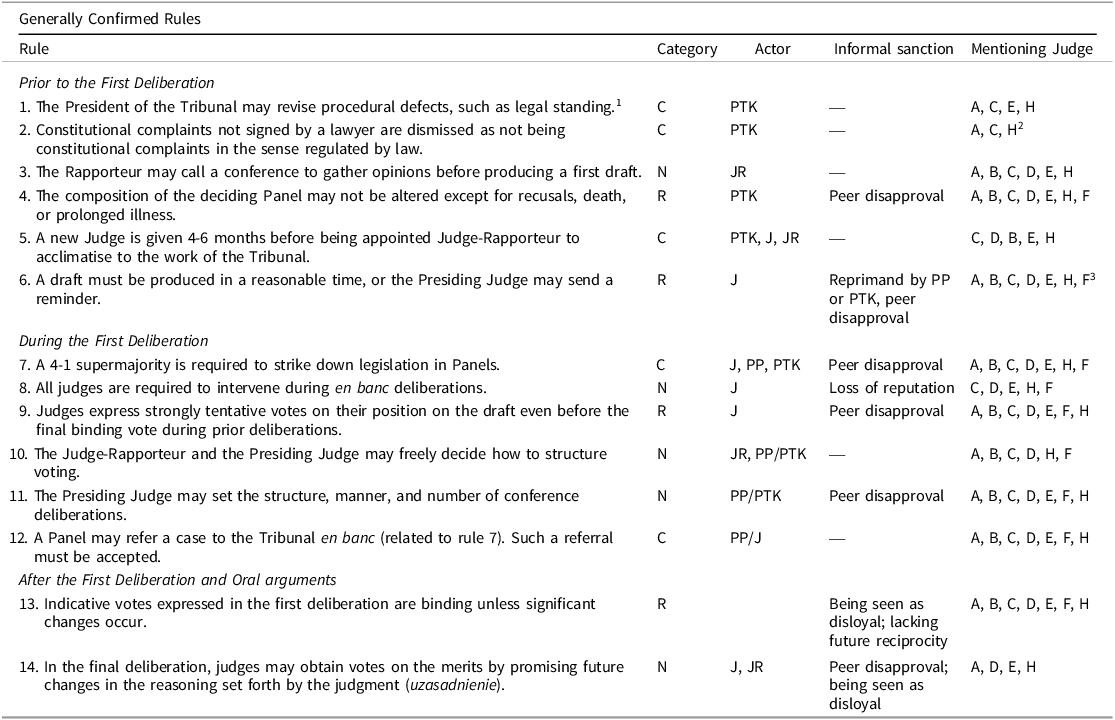

Table 1 presents an overview of all the informal institutions that judges ascertained based on the outline of the procedural stages. Rules in Table 1 were independently confirmed in their scope and binding nature by four or more judges.Footnote 79 The rules were subsequently divided by their allocation in the decision-making process. Finally, we classified the informal rules according to the category identified by Lauth for the relationship between formal and informal institutions, namely, competing, reinforcing, or neutral.Footnote 80

Table 1. Informal institutions in the decision-making process of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal 2012-2016

PTK: President of the Constitutional Tribunal; PP: President of the Panel; J: Judge; JR: Judge-Rapporteur; C: Competing; R: Reinforcing; N: Neutral. In cases of informal sanctions, we marked as ‘—’ when no instance of a breach was mentioned by judges or no possible sanction was mentioned. We do not mean breaches were then unsanctioned.

1 Judges knew about the existence of this rule, yet deeper information was limited since it was an attribution of the President without the intervention of other judges. ‘I did not know how many complaints were dismissed by this previous review of the President of the Constitutional Tribunal’: Judge A.

2 We included rule 2 in the confirmed rules, despite it being confirmed independently only three times. The nature of the rule, mainly pertaining to the office of the Tribunal’s President, meant that not all Judges were aware of it. Still, the authors managed to confirm it by inquiring with former employees of the Court’s Secretariat.

3 However, Judge F deemed that the rule may have only been applicable to major cases of substantive importance.

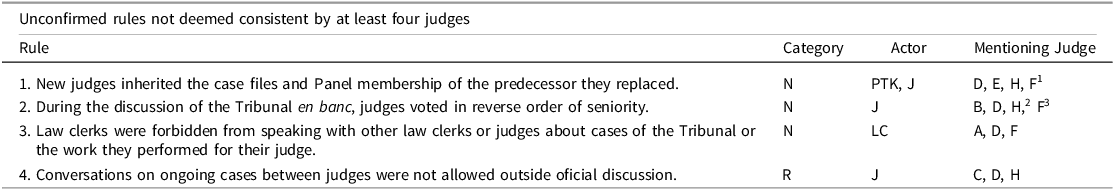

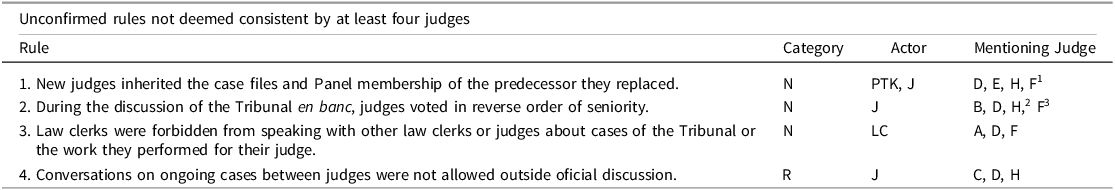

Table 2. Informal institutions in the decision-making procedure of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal 2012-2016

1 Judge F considered that the rule admitted many modulations.

2 Judge H considered that the rule was not strictly followed, since alphabetic voting also took place.

3 Judge F deemed that the rule was not consistently applied and may have fallen out of use during his tenure.

More informal institutions likely existed, which were not detected due to unawareness or the failure of the study to produce more relevant questions.

Given the nature of the semi-structured interviews, on some occasions, judges referred to other rules that we were unable to cross-verify with all judges, due to either a reluctance to answer, the order of interviews – with rules emerging in later stages not being cross-confirmed with prior interviews – or the lack of possible follow-ups in subsequent interviews. Below is a sample of said rules mentioned by more than one judge, but still not generally corroborated. The modulating circumstance is provided in footnotes in the case of those achieving four mentions.

In the following subsections, we will analyse five informal institutions offered by Table 1. We focus on those that have a profound impact on case resolution. We will proceed by first providing a crafted version of the rule, its origin or functioning, and normative justification, as well as reported breaches and associated informal sanctions when mentioned by judges.

Indicative votes

Rule formulation: Before oral arguments, judges gather in a conference to discuss a possible draft for resolving the case. A vote is undertaken. Votes shall be considered binding unless a significant circumstance arises.

As explained above, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal announces a decision immediately after oral arguments, often reading substantial parts of the opinion. For this to be possible, a draft must be prepared beforehand and substantially agreed on. Thus, at least two conference deliberations occur and, depending on the case, more deliberations may take place. One is prior to oral arguments, where the most substantive debate happens, and the second one, after oral arguments, is more of a formality.

All judges reported that during the first conference deliberation, a draft by the Judge-Rapporteur was discussed and voted on. Judges term these ‘indicative voting’ or ‘survey voting’ (sondażowe). Since the first deliberation is not official, votes are not legally binding. Nonetheless, all judges considered that votes were practically definitive.

Judges were expected to repeat the votes of the prior conference deliberations in the official one. Exceptions could occur when important supervening information was made available or new jurisprudential developments of the Tribunal en banc changed the possible outcome of the case. Judges considered that indicative voting was the only possibility that allowed the Tribunal to issue a decision and partially produce an opinion immediately after oral arguments.

All judges generally followed the rule.Footnote 81 Judges changing their opinion without prior notice or substantial reasons stemming from oral arguments were seen as disloyal or unreliable. Sanctions could take the form of commentaries from the Judge-Rapporteur and shared expectations that other judges will not feel bound by their indicative votes in future cases in which the breacher acts as a Judge-Rapporteur.Footnote 82

A tentative conference deliberation

Rule formulation: After a case has been assigned to a Judge-Rapporteur, the rapporteur has the right to call for a conference asking judges for guidelines on how to prepare the draft.

The Judge-Rapporteur is generally required to produce a draft of an opinion for the Presiding Judge to convene a conference deliberation. The Judge-Rapporteur had absolute discretion in crafting the draft. Judges reported that an informal rule allowed the Judge-Rapporteur, particularly in complex cases, to ask the Presiding Judge to convene a conference prior to the draft’s discussion, solely to discuss the first impressions of the Panel or the Tribunal on the case. It was the only instance of a conference without a formal indicative or binding vote, and the positions expressed by the judges were deemed to be only moderately binding.Footnote 83

Judges considered the rule to have a positive effect, particularly on the Judge-Rapporteur. In complicated cases, the Rapporteur’s obligation to produce a draft prior to collegial deliberation could have a substantial impact on his/her work. It helped to avoid investing considerable time on a draft that would fail to produce a consensus. Tentative guidelines facilitated effective working dynamics without forcing time-consuming efforts that could yield uncertain results.

Compliance with the rule was universal. All presiding judges held conference meetings when requested by the rapporteur, and all judges attended such meetings and discussed their impressions to facilitate draft preparation.

Supermajority requirement to invalidate legislation

Rule formulation: When the Tribunal functions in a five-member decisional Panel, a 4:1 supermajority is required to invalidate legislation. An inferior majority leads to referral of the case to the Tribunal en banc.

In the selected period, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal functioned under majority rule. A formal constitutional provision (Article 190.5) provided that ‘Judgments of the Constitutional Tribunal shall be made by a majority of votes.’ Parliament had understood the provision as establishing a simple majority rule.Footnote 84 Even if transitorily in 2015, a supermajority was introduced by the PiS-dominated Parliament for the Tribunal en banc to decide cases,Footnote 85 the Tribunal promptly declared said provision unconstitutional.Footnote 86

Despite the formal majority provision, all judges reported that Panels functioned under an informal supermajority rule. If a five-member Panel analysed the constitutionality of legislation, an informal institution provided that decisions could be taken ordinarily 5:0, 4:1, or 3:2 to validate the act, but had to be taken at least by a 4:1 supermajority to declare it unconstitutional. Self-imposed deviation from majority rule for specific decisions is not uncommon in constitutional courts. Other courts have been known to adopt informal supermajority rulesFootnote 87 or sub-majority rules to provide affirmative outcomes.Footnote 88

The mechanism functioned as follows. During the first conference deliberation, a vote was taken. If a 3:2 or 4:1 majority favoured declaring the statute constitutional or unconstitutional, respectively, the case proceeded along ordinary channels. If a 3:2 majority favoured the unconstitutionality of the law, the Presiding Judge of the Panel would write a formal petition to the President of the Tribunal to reclassify the case as ‘particularly complex’, and thus falling within the competence of the Tribunal en banc, not of a five-member Panel. The petition would invariably be granted.

Judges deemed that a supermajority rule was normatively justified insofar as it strengthened the legitimacy of the institution by not delivering disputed judgments by bare majorities and additionally protected the competences of the Tribunal en banc by precluding issuing decisions that, having a bare majority, may have led to a different resolution by the full Tribunal.

Judges posited that the rule was in place before 2012, though they were unsure whether it then had the nature of a rule out of non-consistent application.Footnote 89 Most of them remembered that the rule already existed when they joined the Tribunal. Instances of breaches were sporadic. However, a couple of judges mentioned remembering cases where the Panel’s Presiding Judge said the 3:2 vote was final, and the case was not further referred. The justification for said cases was that the questioned laws were neither controversial nor particularly complex, but said behaviour was perceived as questionable.Footnote 90

Prohibition on introducing changes in the Panel’s composition after the deciding Panel has been appointed

Rule formulation: Once the President has assigned a decisional Panel, its composition may not be altered except for recusals as provided by law.

The Tribunal functioned en banc on limited cases. Most cases were resolved by five or three-member Panels, with the former being the predominant formation. An algorithm determined the Panel composition. Nonetheless, no legal provision forbade the Tribunal’s President from referring the case subsequently to a larger composition, such as the Tribunal en banc, or even introducing nuanced modifications to the Panel composition.

Judges were of the impression that a joint consensus provided that once a Panel had been assigned, no changes could be introduced if they were not derived from validly filed recusals, death, or prolonged illness. The rule was understood to protect the independence of judges and limit the Tribunal President’s temptation to attempt to steer the Tribunal into his/her preferred outcome, either by replacing Panel members or by switching the decisional composition. The only accepted exception was the previously mentioned supermajority rule in five-member Panels.

The prohibition arguably limited some possible positive practices, such as appointing Panel members with expertise on the topic, but judges considered the rule’s advantages outweighed its shortcomings. Judges declared that they did not remember cases in which the President of the Tribunal introduced changes after the composition was definitively settled. Nonetheless, some declared having direct knowledge of such changes post-2016, following the appointment by PiS of a new President of the Constitutional Tribunal. Other judges said they had gained indirect knowledge of such changes from colleagues.

Negotiations during the final deliberation

Rule formulation: During the conference discussion following oral arguments, the Judge-Rapporteur is allowed to negotiate the vote of a reluctant Judge in exchange for amendments to the reasoning set forth in the final ruling (uzasadnienie). If agreed upon, the judge votes in favour, a decision is announced, a final vote tally is conveyed, and changes are made ex post.

After oral arguments, it was usual for a quick conference to be held to carry out the formal voting, usually confirming the indicative votes of the first conference deliberation prior to oral arguments. In some cases, indicative votes were unconfirmed because of the lack of clarity on certain procedural aspects or because the Judge-Rapporteur had made changes to the draft prior to oral arguments, particularly to the reasons set forth by the Tribunal to reach an outcome.

In such a case, an unwritten rule allowed the Judge-Rapporteur to obtain ‘votes in advance’ after oral arguments in exchange for changes in the final draft. Thus, the Judge-Rapporteur would offer to introduce the amendment described by the reluctant colleague, and immediately, the judge would vote in favour of the judgment without reading the final version of the opinion. The decision was immediately announced. The Judge-Rapporteur committed to introducing the changes before publishing the final version of the opinion. Most judges indicated familiarity with it, but some stated that its occurrence was relatively rare. Its application may occur only in cases where a judge deems that his/her vote on the disposition of the case (sentencja) entirely depends on the reasons explained in the opinion (uzasadnienie).

Judges considered this rule normatively justified as it helped the Tribunal announce a decision immediately after oral arguments. Compliance with the agreement was very high.Footnote 91 Nonetheless, judges stated that they knew that there were a few instances in which the Judge-Rapporteur did not introduce the promised changes.Footnote 92 Since the case was already voted on, the agreeing judge could not retrieve their vote.

The following section will explore the effects of polarisation on the upholding of informal institutions by analysing whether the Polish constitutional crisis, resulting in partisan membership alterations, impacted the existing informal institutions or led to the emergence of new ones.

Polarisation and the breach of informal institutions

From social and political polarisation to judicial polarisation

Polarisation may be defined as a societal division through ‘us versus them’ dynamics based on a single dimension that overshadows all others.Footnote 93 Political polarisation has been broadly studied,Footnote 94 with a growing body of literature arguing that it may first be reflected by the destruction of informal institutions. For instance, Levitsky and Ziblatt argued that polarisation in US politics led to the breach of the informal institutions of mutual toleration and institutional forbearance.Footnote 95

Although studies on the effects and causes of polarisation within the judiciary are growing,Footnote 96 the impact of polarisation on internal informal institutions is yet to be explored. Scholarship has generally not delved into how informal institutions foster or diminish the attempts of polarised judiciary members to achieve partisan outcomes, nor whether informal institutions face higher risks of modification or abandonment during periods of polarisation. Despite the above, some scholars have noted that informal judicial institutions, such as voting protocols, might be affected by polarisation.Footnote 97

Porat was the first to propose a typology outlining the relationship of polarisation to courts. He put forward three models: mirror polarisation (courts mirroring social polarisation); one-sided polarisation (in which the courts reflect views of a single political camp); and cracks in consensus-based nominations of the continental model.

For the purposes of this article, we propose understanding the effects of court polarisation in informal institutions through a dual typology centring on the court perspective: external and internal polarisation, resulting in four scenarios of varying degrees. From the standpoint of the court, we term external polarisation as the polarisation of society and/or the elected branches, while we refer to internal polarisation as polarisation occurring within courts. Categories may be cross-considered – i.e. there might be: (a) polarised courts in polarised societies; (b) polarised courts in non-polarised societies; (c) non-polarised courts in polarised societies; and (d) non-polarised courts in non-polarised societies. Being an ideal type, the distinction is not of absolutes but of degree.

It is well known that the Polish constitutional crisis had a polarising effect not only on Polish political branches but also on the Constitutional Tribunal.Footnote 98 While at the beginning of the constitutional crisis, the Tribunal was likely experiencing the effects of external polarisation (concretely, it was a non-polarised court in a polarised society), after the appointment of dublerzy, the situation quickly evolved to an internally polarised tribunal. Judges, as confirmed by the interviews, formed ‘camps’. The overlap of the analysed period offers the rare opportunity to explore the effects of internal polarisation, fostered and sustained by external polarisation, on informal institutions in judicial decision-making.

The effects of internal polarisation on informal institutions in the Polish Constitutional Tribunal

It is undisputed that in periods of democratic backsliding, often associated with polarisation, many regimes directly attempt to alter the legal regulations governing courts, hoping to gain control of them.Footnote 99 In the case of Poland, the PiS-controlled Sejm issued a new law on the Constitutional Tribunal, attempting to block the court.Footnote 100

While informal institutions are different in nature from formal ones, political scientists have analysed their joint impact, for example, in strategic accounts of judicial behaviour that consider that formal and informal institutions together form the ‘rules of the game’.Footnote 101 Polarisation may lead political and judicial actors to attempt to change the rules of the game during periods of polarisation, whether formal or informal. If formal rules, promulgated and enforced through official channels subjected to broad public scrutiny, are often changed, amended, and subverted during periods of political polarisation to favour one camp over another one, it might be expected that similar instances may occur with informal judicial institutions. Opportunities to change or abandon informal institutions are enhanced by their unwritten nature and reduced visibility, making them prone to erosion with less accountability. It also provides actors willing to ignore said rules with opportunities to argue that they constitute mere instances of repeated non-binding behaviour.

The fact that the political majority managed to elect the President of the Tribunal and several judges deemed as partisan enables us to hypothesise that, in addition to changes to formal law by the PiS-dominated Sejm, the newly-elected judicial actors might have resorted to undermining the existing informal institutions or attempted to replace them when they constituted barriers to reaching outcomes consistent with their partisan policy preferences.

Even though some of the informal institutions in the Polish Constitutional Tribunal were very technical in nature, two factors could endanger their survival. First, informal judicial institutions might have constituted constraints – especially at the early stages of the crisis – preventing strategic actors from steering the cases in a specific direction. Initially, judges favouring the new ruling majority were a minority, even accounting for control of the Tribunal’s presidency. Under those conditions, incentives might exist for the new judges to abandon or breach preexisting informal institutions. For example, the informal rule granting new judges an accommodating period before being appointed Judge-Rapporteur, informal rules dictating the immobility of the deciding Panel or the 4:1 supermajority to invalidate legislation would constitute significant obstacles to rallying the minority of judges into maximising their effect – e.g. strategically concentrating the minority of judges in ad hoc five-member decisional Panels to obtain 3-2 bare majorities upholding legislation or invalidating that of the previous government. Second, the survival of said norms is anchored in social convention, reciprocal expectations of compliance, and deterrence of breaches by informal sanctions relying on peer disapproval, all of which were likely to be affected by the crisis.

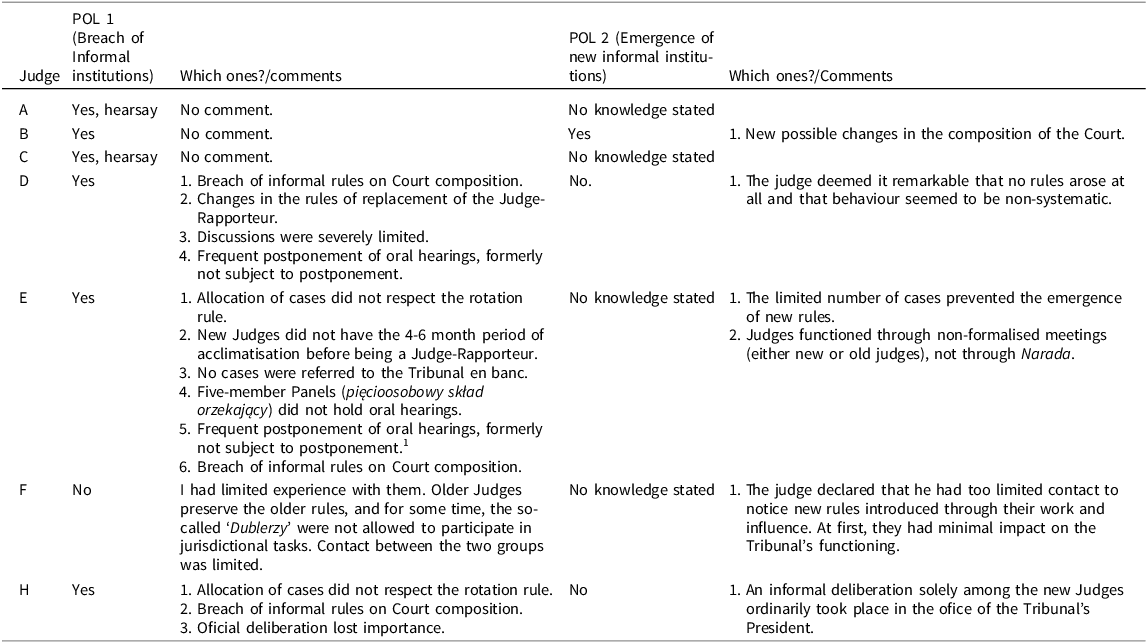

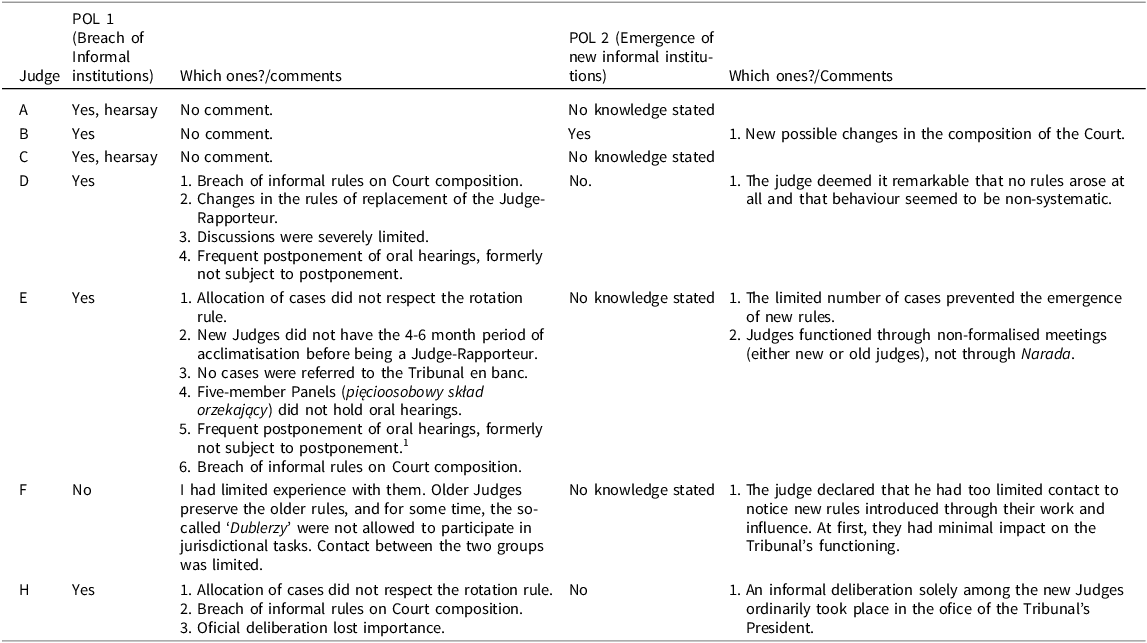

To inquire into such effects, the interview guide included Section D, intended to obtain information pertaining to breaches or abandonment of informal institutions after the incorporation of the new judges (POL1) or the emergence of new informal institutions (POL2). Unsurprisingly, research pertaining to this section was more challenging to conduct. Even some outspoken judges understandably refrained from providing more specific information, arguing that such disclosures constitute administrative liability, or chose to disclose breaches that have also been documented in the media and are public knowledge. Judges B, C, and E, for example, declared that they did not know of the emergence of new informal rules but simultaneously emphasised that they refused to take part in new behaviours, clarifying that they strictly upheld the standards they considered proper prior to the crisis.

Of the seven obtained inputs, six declared that they had perceived a breach of informal institutions. Only Judge F stated that they had no knowledge, given the limited contact between both groups and the initial lack of participation of Dublerzy in jurisdictional tasks.Footnote 102

The case study shows that the members of the interviewed natural court generally perceived a breach of informal institutions. However, information was more limited as to the specific rules breached or the new ones that emerged. In the first case, three judges stated no knowledge, arguing unmatching periods, lack of contact, or personal isolation. The four remaining judges declared that informal rules pertaining to Panel membershipFootnote 103 were breached, followed by less universal perceptions that informal rules regulating case allocation were violated. Information is limited on the new informal institutions that arose, probably due to the period of the sample and the lack of contact between prior and new judges.Footnote 104 That is, in some cases, the formal terms of several interviewed judges did not allow some of them to gain greater insights into the operation of the new court composition, which may have overlapped only with terms ending in late 2016 and best in 2017 and onwards. Table 3 provides a summary of the answers given.Footnote 105

Table 3. Informal institutions of the 2012-2016 natural court period after the active incorporation of dublerzy to the Constitutional Tribunal

1 In answering PRE4, Judge E stated, ‘We never used to move an oral hearing. This later on became a tradition, a rule …’. In POL1, the same Judge declared, ‘another thing [exemplifying the abandonment of institutions] is that now oral hearings are annulled very frequently’.

Despite the lack of a broader consensus on the specific new informal institutions that emerged, alternative sources exist. Several journalists and scholars denounced the emergence of new informal behaviour under the newly PiS-appointed President of the Tribunal. Instances included consultations over the election of the presiding judges of other judicial bodies,Footnote 106 the expansion of the President’s power to form and change the deciding Panels,Footnote 107 tampering with the composition of decisional Panels,Footnote 108 and consultations with the Prime Minister’s office to discuss sensitive cases.Footnote 109 However, the available sources lack sufficient data on the frequency or perceived binding nature of said instances of informality – which information is required to classify them as informal institutions, informal practices, or single instances of informal acts.

The Polish case study seems to conform to the pattern of other jurisdictions, such as the United StatesFootnote 110 and Mexico,Footnote 111 in which scholars have claimed that political polarisation, politically charged appointments, and drastic changes in political preferences reflected in courts have led to the erosion of informal judicial institutions.

One way to expand our knowledge in this area may be to gain access to the judicial elites appointed as a result of court-packing. Documenting the perceptions of the contested judges would provide a solid input to assess the changes better. However, interviewing said group would exceed the natural court analysed in this study, and present additional methodological challenges in gaining access to respondents.

Conclusions

This article provided a mapping of informal institutions governing the Polish Constitutional Tribunal (2012-2016). In doing so, it uncovered a vast net of rules. It then focused in-depth on five informal institutions that significantly impacted the Tribunal’s procedures: indicative votes; the informal supermajority rule to strike down legislation; a pre-conference deliberation aiding the Judge-Rapporteur; the prohibition on modifying Panel composition; and the informal rule allowing exchanges of votes for changes in the redaction of opinions during conference deliberations following oral arguments.

The analysis demonstrated that, coupled with formal institutions provided by law and the internal regulations, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal, a court in a classic civil law jurisdiction, mistrustful of allegedly unwritten sources of law, co-governed its decision-making through a set of informal rules that complemented, aided, or substituted formal normative provisions.Footnote 112

The weight of said rules cannot be underestimated, as in many cases they directly dictated case outcomes – such as the informal supermajority rule – or underlying aspects that may have steered the case into a different judicial outcome – such as informal rules on Panel composition, and prior conference deliberations. The strength of said rules may be reinforced by the perception of the interviewed natural court that even if a legislative majority had effective control of the law governing the Tribunal’s functioning, the nomination of dublerzy and allegedly partisan new judges nominated by the majority was a factor associated with the breach of informal rules, presumably because they were an obstacle to the new judicial elite’s intention to achieve specific politically-charged judicial outcomes.

On a second note, the article explored the effects of internal polarisation on the consistency of the application of informal institutions. Internal court polarisation was perceived to play a significant role in the abandonment, breach, and inconsistent application of informal institutions. Explanatory factors may be the diminished collegiality in polarised courts, the lack of strategic expectations of future cooperation, and the potential diminished effectiveness of informal sanctions associated with breaches.Footnote 113

Unfortunately, the information obtained is insufficient to definitively identify which informal institutions were regularly breached and which new informal institutions arose. That information is necessary to theorise whether there is a common characteristic of the breached informal institutions, and the reasons for their modification or abandonment by the new elites. Future research may be expanded by directly interviewing natural courts in fully polarised periods, and attempting to gain access to all contraposed judicial camps.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1574019625100874

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that they have contributed equally to this research article. This article was presented at the conference ‘European Law Abound’ (Prague, 2025). The authors are grateful for the insightful comments received from the participants of the Panel ‘Judicial Dialogue and National Constitutional Courts’. The authors also wish to thank the reviewers and editors for their very detailed and constructive comments, which significantly improved the manuscript.

Funding information

These research activities were co-financed by the funds granted under the Research Excellence Initiative of the University of Silesia in Katowice (2024). Regarding M.A. Rivera, this article was written during a research stay at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law in Heidelberg (July-August 2025), financed by the University of Silesia in Katowice under the program ‘Mobilność | Nauka - III edycja’.