Anxiety and mood disorders are highly prevalent around the world, and there is a general concern that their prevalence is on the rise. Trends in prevalences of mental disorders, however, are difficult to establish as only a few large-scale epidemiological studies in representative population samples have been conducted across time.

Until the beginning of the 21st century, a few studies suggested increased trends in disorders, with the prevalence of depression showing a steady increase from 1989 to 2016,Reference Andersen, Thielen, Bech, Nygaard and Diderichsen1–Reference Moreno-Agostino, Wu, Daskalopoulou, Hasan, Huisman and Prina4 but numerous studies reported stable prevalence rates of mental disorders or symptoms over time.Reference Cebrino and de la Cruz5–Reference de Graaf, ten Have, van Gool and van Dorsselaer7 More recently, however, various studies examining trends over the past decade confirmed an increase in mental disorders or problems.Reference Yu, Zhang, Wang, Sun, Jin and Liu8–Reference Twenge, Cooper, Joiner, Duffy and Binau10 The most recent study in England indicates a steady increase in common mental health conditions across 2007, 2014 and 2023/24, based on screening rather than clinical instruments, with younger adults being at higher risk.Reference Morris, Hill, Brugha and McManus11 The recently reported rise in mental health care useReference Ruths, Haukenes, Hetlevik, Smith-Sivertsen, Hjorleifsson and Hansen12–Reference Momen, Beck, Lousdal, Agerbo, McGrath and Pedersen15 might also suggest that the prevalence of mental disorders has increased, but this may also be explained by improved accessibility, efficiency and capacity of care.

Additionally, in the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Studies (NEMESIS), we recently demonstrated an increase in the 12-month prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders between 2007 and 2022, from 6.0 to 10.8% and from 10.1 to 15.6%, respectively.Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten, Luik and de Graaf16 These increased prevalences seemed slightly larger in younger adults aged between 18 and 35 years. Increases were unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic, as trends were already rising before the pandemic – an observation now supported by multiple studies,Reference Penninx, Benros, Klein and Vinkers17 including our own NEMESIS results.Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten, Luik and de Graaf16 This raises the question as to how to explain this increase in anxiety and mood disorders. It also remains unclear whether the increase in the prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders reflects a broader rise across all severity levels or is mainly driven by reporting of less severe cases. Alternatively, the increase could be explained by shifts in the distribution or impact of key sociodemographic, vulnerability or health-lifestyle risk factors over time. Investigating these possibilities is critical to better understanding the nature of the rising burden of these disorders and informing future prevention and intervention efforts.

Aim of the study

This study aims to assess whether the prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders was higher in 2019–2022 compared to 2007–2009. In comparison of disorder prevalences at two time-points, we focus also on potential differences in the specific clinical characteristics of these disorders – such as severity, age at onset, and psychotropic medication use – as well as trend differences between younger (18–34 years) and older (35–64 years) age groups. In addition, we will examine whether changes in the prevalence and impact of established risk factors contributed to the higher rates of anxiety and mood disorders observed in 2019–2022. Specifically, we will assess whether the prevalence of certain risk factors – such as an increase in the proportion of people living alone – has changed over time (absolute risk), and whether the strength of their association with mental disorders (relative risk) has shifted between the two study periods.

Method

Study design

NEMESIS used a stratified, multi-stage random sampling process. Initially, municipalities were randomly selected, with the four largest cities (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht) included in advance. In NEMESIS-2, private household addresses were randomly drawn from postal registers, and a household member aged 18–64 was selected based on their most recent birthday.Reference de Graaf, Ten Have and van Dorsselaer18 In NEMESIS-3, a random sample of individuals aged 18–75 was taken from the Dutch population record.Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten and de Graaf19 Individuals not fluent in Dutch or institutionalised were excluded, except for those temporarily institutionalised.Reference de Graaf, Ten Have and van Dorsselaer18,Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten and de Graaf19 Ethical approval was granted for NEMESIS-2 because of the saliva collection, while NEMESIS-3 did not require approval under the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). Detailed descriptions have been provided elsewhere.Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten, Luik and de Graaf16,Reference de Graaf, Ten Have and van Dorsselaer18,Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten and de Graaf19 Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents in both studies.

Fieldwork and response rate

The baseline wave of NEMESIS-2 (November 2007 to July 2009) and NEMESIS-3 (November 2019 to March 2022) consisted of three phases. In NEMESIS-3, the re-contact period was extended due to COVID-19, and 500 interviews (8.1%) were conducted via video call. Most interviews in both studies were face-to-face at respondents’ homes using laptop-assisted methods. Interviews at baseline lasted 95 min on average in NEMESIS-2 and 91 min in NEMESIS-3. The response rate was 65.1% (6646 responders) in NEMESIS-2 and 54.6% (6194 responders) in NEMESIS-3. For comparability, participants over 64 years were excluded, leaving a final sample size of 4969 in NEMESIS-3.

Generalisation to the Dutch population

In both studies, participants accurately reflected the Dutch population, though younger people, those with lower or higher secondary education and those without partners were underrepresented. To generalise the data, a weighting factor was constructed for each study through post-stratification, correcting for response rates across groups and in NEMESIS-2 additionally for selection probability within households. This factor accounted for sex, age, partner status, urbanicity and education level, using data from Statistics Netherlands (2008 for NEMESIS-2, 2020 for NEMESIS-3).Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten, Luik and de Graaf16 After weighting, the sociodemographic characteristics closely matched those of the Dutch population.

Diagnostic assessment

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) developed for the World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative was used to diagnose 12-month prevalence of mental disorders, providing DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses. NEMESIS-2 used CIDI version 3.0, while a slightly modified version 3.0 was used in NEMESIS-3 to be able to improve interview flow and incorporate DSM-5 criteria, with no meaningful effect on DSM-IV prevalence estimates.Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten and de Graaf19 This study examined and analysed consistently defined DSM-IV mood disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymia and bipolar disorder) and anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder).

Risk factors

Based on existing literature and data availability, we selected a range of risk factors that are known to be related to the prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders. These factors are explained in further detail below.

Demographic characteristics (sex, age, living situation, education, employment and income) were collected through self-constructed interview questions. Living situation was based on partner status, employment on having a paid job (or not) and education was categorised into three levels: primary/lower secondary, higher secondary and higher vocational/university. Income was based on household income, divided into three categories: lowest 25%, middle 50% and highest 25%.

Vulnerability characteristics include recent negative life events and childhood trauma. Recent life events measured the occurrence of ten negative events in the past 12 months based on the Brugha Life Events section (e.g. death of a relative or divorce), while childhood trauma assessed emotional neglect, and psychological, physical or sexual abuse before age 16.Reference Brugha, Bebbington, Tennant and Hurry20

Health and lifestyle factors included alcohol and drug use disorders, smoking, physical inactivity, chronic physical conditions and being overweight/obesity. DSM-IV alcohol and drug disorders were assessed with CIDI 3.0, smoking was based on use in the past four weeks and physical inactivity was by adherence to the Dutch healthy exercise norm, defined as being physically active for at least 30 min per day, at moderate intensity, on most days of the week.Reference Craig, Marshall, Sjöström, Bauman, Booth and Ainsworth21 Chronic conditions were defined using a comprehensive approach that evaluates their presence, treatment in the past 12 months, doctor visits or medication used and age at onset, focusing on 17 chronic somatic disorders.Reference de Graaf, Ten Have and van Dorsselaer18 The body mass index (BMI) was categorised as normal/underweight (BMI: <25) or overweight/obese (BMI: ≥25).

The same questions and assessment methods were used in both NEMESIS-2 and NEMESIS-3 to ensure comparability.Reference de Graaf, Ten Have and van Dorsselaer18,Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten and de Graaf19

Statistical analyses

The general characteristics of the samples at baseline, 12-month prevalence rates of anxiety and mood disorders and their clinical characteristics in both NEMESIS-2 and NEMESIS-3 were described using frequency tables. Weighted percentages ensured accurate population representation. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables to compare differences between both studies. The difference in prevalence rates between NEMESIS-2 and NEMESIS-3 was calculated, and analyses were stratified by age groups to assess potential age-related differences.

To evaluate whether changes in the prevalence (i.e. percentage of the sample) of risk factors may explain the observed increase in anxiety or mood disorders between NEMESIS-2 and NEMESIS-3, we compared the distributions of demographic, vulnerability and health-related lifestyle variables across the two studies. For each variable, we calculated the absolute percentage point difference in the prevalence of a risk factor between the two samples. Logistic regression was used to examine the relative impact of risk factors on any anxiety or mood disorders, with separate models run for each variable and stratified by age for each study. Results were reported as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. To test whether the relative impact of risk factors on any anxiety or mood disorders was different in NEMESIS-2 versus NEMESIS-3, we tested multiplicative interactions using logistic regression and additive interactions using generalised linear models with a binomial family and an identity link function. We examined both multiplicative and additive interactions to capture distinct aspects of how risk factors could relate to anxiety or mood disorders. While multiplicative interactions assess whether effects exceed expectations on a relative scale, additive interactions test for excess risk on an absolute scale, which is important for public health interpretation.Reference VanderWeele and Knol22 Prior studies have shown that findings can differ depending on the interaction scale,Reference Coleman, Peyrot, Purves, Davis, Rayner and SW23,Reference Peyrot, Milaneschi, Abdellaoui, Sullivan, Hottenga and Boomsma24 supporting the value of including both interaction approaches.

There were no missing values for the main disorder variables; for a few demographic and clinical characteristics with low missingness (1–2%), no imputation was performed due to the minimal impact on results.Reference Dong and Peng25 Importantly, although NEMESIS-3 data collection overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic, we did not adjust for pandemic timing, as only 25.4% of data were collected pre-pandemic, earlier analyses did not find prevalence differences in the year before (2019) or during (2020–2022) the COVID-19 pandemic within the baseline of NEMESIS-3 and existing evidence suggests that observed increases during the pandemic largely reflect symptom-level changes rather than diagnosed disorder prevalence.Reference Penninx, Benros, Klein and Vinkers17

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA; https://www.stata.com) on Windows, with post-stratification weights applied to ensure population representativeness. Figure 1 was generated using RStudio 4.3.2 (RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA; https://www.rstudio.com) on Windows.

Results

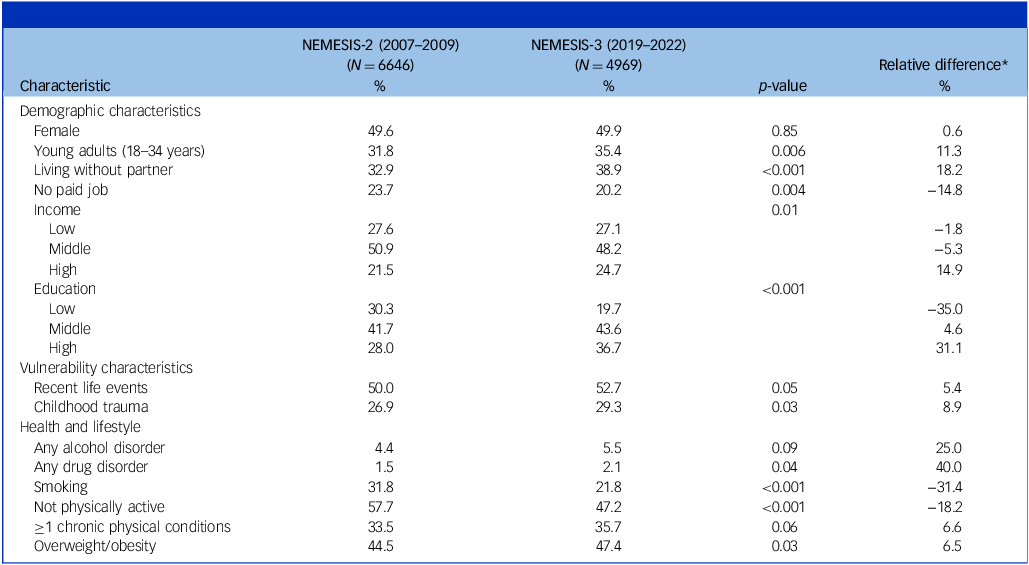

Sex distribution was similar across studies (49.6% female in NEMESIS-2 and 49.9% in NEMESIS-3), with minor age-stratified differences. There was a slight difference in age with fewer young adults (18–34) in NEMESIS-2 than in NEMESIS-3 (31.8 v. 35.4%) (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10454).

Table 1 Sample characteristics in NEMESIS-2 (2007–2009) and NEMESIS-3 (2019–2022)

*Relative difference in prevalence of NEMESIS-2 compared to NEMESIS-3 expressed as percentage.

Data were weighted using post-stratification to ensure generalisation to Dutch population.

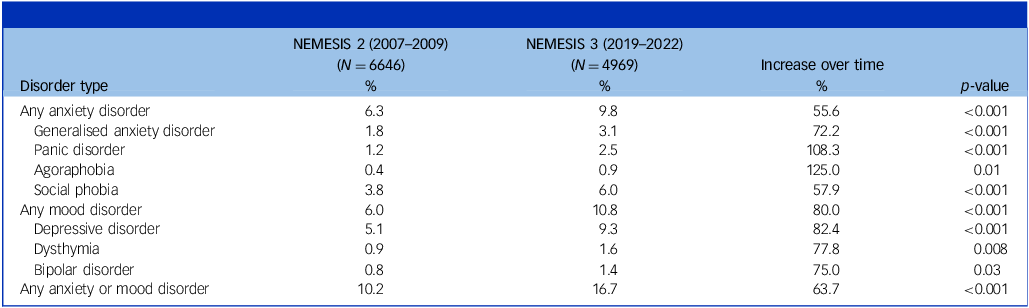

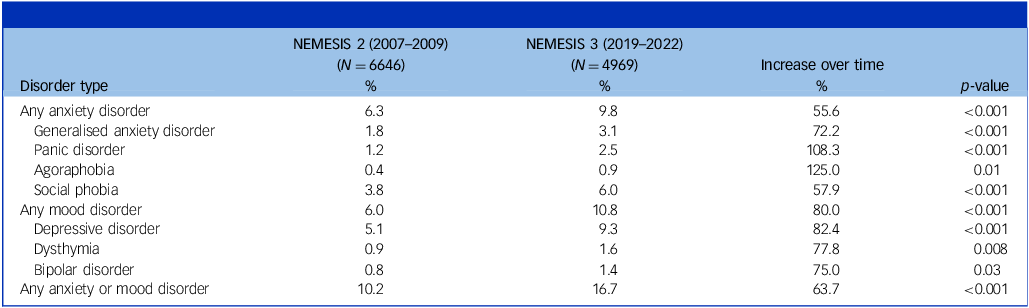

Trends in prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders

All types of anxiety and mood disorders showed a significant increase from 2007–2009 to 2019–2022, with a range between +55.6 and +125.0% (Table 2). The 12-month prevalence of any anxiety disorder increased by 55.6% (from 6.3 to 9.8%) over 12 years, and this was 80.0% (from 6.0 to 10.8%) for any mood disorder. Overall, the 12-month prevalence of any anxiety or mood disorder increased by 63.7% (from 10.2 to 16.7%).

Table 2 12-month prevalence rates of anxiety and mood disorders in NEMESIS-2 (2007–2009) and NEMESIS-3 (2019–2022)

Data were weighted using post-stratification to ensure generalisation to Dutch population.

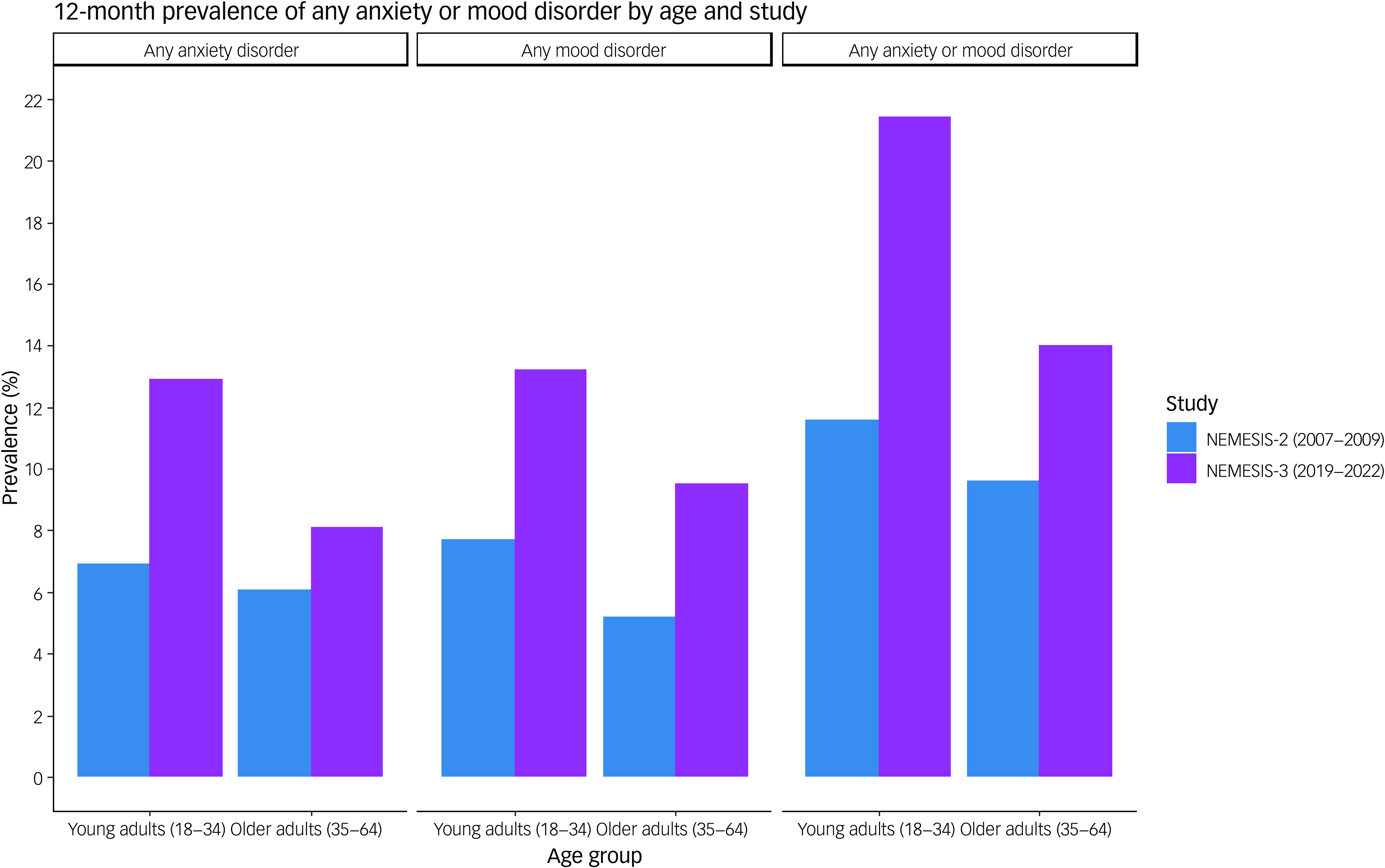

Both young and older adults experienced a significant increase (p-value <0.001) in any anxiety or mood disorder over time, with an increase in younger adults of 84.5% (from 11.6 to 21.4%) and in older adults of 45.8% (from 9.6 to 14.0%, Fig. 1). Especially for anxiety disorder, the increase seemed more pronounced in younger adults (87% increase) than in older adults (32.8%). For mood disorder, the increase was rather similar with 71.4% in younger adults and 82.7% in older adults.

Fig. 1 12-month prevalence rates of any anxiety and/or mood disorder in NEMESIS-2 (2007–2009) and NEMESIS-3 (2019–2022) by age. Data were weighted using post-stratification to ensure generalisation to Dutch population.

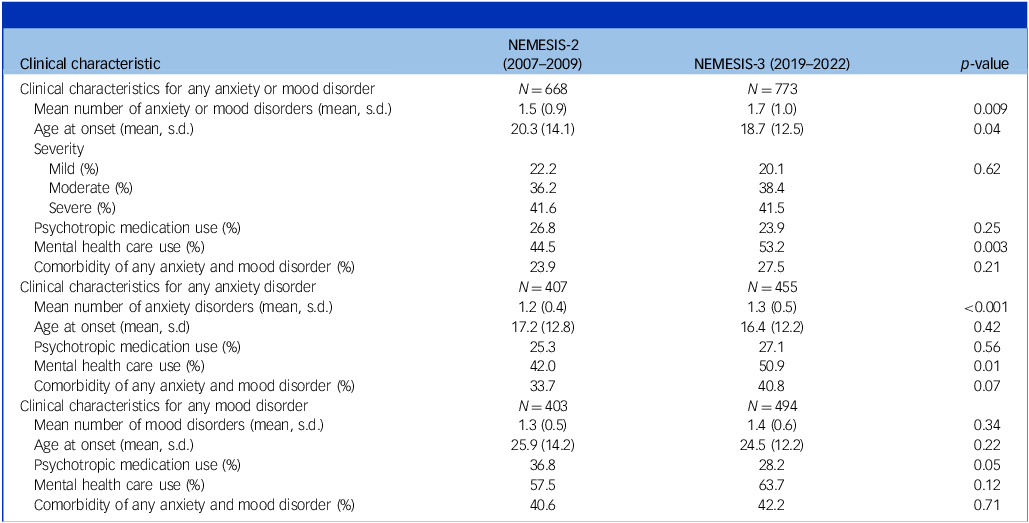

While severity and comorbidity patterns remained stable between NEMESIS-2 and -3 (Table 3), there was an increase in the mean number of anxiety or mood disorders (1.5 to 1.7) and in mental health care use (44.5 to 53.2%). Also, a mean younger age at onset was observed, from 20.3 in NEMESIS-2 to 18.7 years in NEMESIS-3. Only in individuals with a mood disorder did psychotropic medication use decline (36.8 to 28.2%). In NEMESIS-2, 407 participants (weighted data) had any anxiety disorder, of whom 270 (66.3%) had a comorbid mood disorder and a total of 403 participants had any mood disorder, of whom 164 (40.7%) had a comorbid anxiety disorder. In NEMESIS-3, 455 participants (weighted data) had any anxiety disorder, of whom 186 (40.9%) had a comorbid mood disorder and a total of 494 participants had any mood disorder, of whom 208 (42.1%) had a comorbid anxiety disorder. Clinical characteristics patterns over time were generally comparable in young and older adults, with the increase in the mean number of disorders, mental health care use and comorbidity over time being most clear in older adults (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3 Clinical characteristics in NEMESIS-2 (2007–2009) and NEMESIS-3 (2019–2022) among people with psychopathology

Data were weighted using post-stratification to ensure they are representative of the Dutch population.

The role of risk factors in the increase of anxiety and mood disorders

To determine whether certain risk factors were more common in NEMESIS-3 than NEMESIS-2, and thus could have a larger absolute impact, we compared their prevalence (see Table 1). The largest changes were a reduction in persons with low education (−35.0%) and smoking (−31.4%) and an increase in persons with alcohol use disorder (+25.0%) and drug use disorder (+40.0%) in NEMESIS-3 as compared to NEMESIS-2. For all other risk factors, there were smaller differences (<20%) in alternating directions (positive or negative). Consequently, it seems that consistent shifts in risk-factor prevalence are unlikely to account for the increased prevalence of any anxiety or mood disorder.

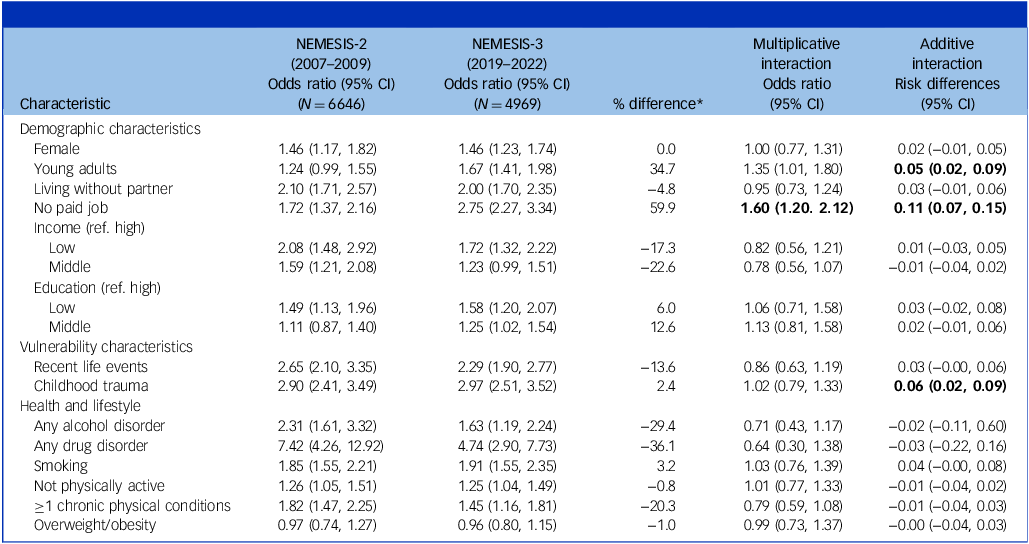

To examine whether risk factors may have had a different relative impact over time, we examined whether known risk factors showed a different relative risk in NEMESIS-2 versus NEMESIS-3. As expected, all risk factors were significantly positively associated with the presence of any anxiety or mood disorder in both studies, except for overweight/obesity (Table 4). Relative risks (as determined by odds ratios) appeared consistent between NEMESIS-2 and NEMESIS-3, with largely overlapping confidence intervals. Notably, not having a paid job was more strongly associated with any anxiety or mood disorder in NEMESIS-3, as confirmed in multiplicative as well as additive interaction. Only four out of 28 tested multiplicative and additive interaction terms were significant, which is close to what could be expected based on statistical chance. Also, when examining younger and older adults separately, trends in the absolute and relative impact of risk factors over time did not show large differences between groups. Higher education increased most over time in young adults (+54.6%) whereas drug use disorder increased (+33.3%) and smoking decreased (−31.3%) more in older adults, but the vast majority of risk factors did not change in both age groups (Supplementary Table 1). Relative risks (as determined by odds ratios) remained stable over time across age groups, confirmed by non-significant interaction terms (Supplementary Table 3a, 3b).

Table 4 Association of any anxiety or mood disorder and risk factors in NEMESIS-2 (2007–2009) and NEMESIS-3 (2019–2022)

ref., reference.

*The difference in odds ratio of NEMESIS-2 compared to NEMESIS-3 expressed as percentage.

Statistically significant (p-value <0.05) differences in odds ratios for multiplicative interactions and risk differences for additive interactions are indicated in bold.

Data were weighted using post-stratification to ensure generalisation to Dutch population.

Discussion

Key findings

This study extended in more detail the recent Dutch observations from the large-scale NEMESIS study describing a marked increase in the prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders between 2007–2009 and 2019–2022.Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten, Luik and de Graaf16 Results confirmed a significant and consistent increase in the 12-month prevalence of all types of anxiety and mood disorders during this period. In 2019–2022, 16.7% of the population reported any anxiety or mood disorder in the past 12 months, which was 63.7% higher than in 2007–2009. The increase in anxiety and mood disorders was consistently observed in younger and older adults, but younger adults had a slightly higher increase, especially in anxiety disorders. The clinical profiles of persons with anxiety or mood disorders were generally consistent in severity over the two periods, although slightly more people had used mental health care in the most recent time-period and the mean number of anxiety and/or mood disorders also increased. Furthermore, an increased absolute or relative impact of the sociodemographic, vulnerability and health-lifestyle risk factors examined did not provide a solid explanation for the increase in any anxiety or mood disorder, suggesting that other, potentially unexplored factors may be contributing to the growing burden of these mental health conditions.

Trends in the prevalence of types of anxiety and mood disorders

Our results clearly indicate that the increase in anxiety and mood disorders in the last decade is not driven by only one disorder type, but is seen consistently for all anxiety and mood disorders. The increase is true for the least common disorders, such as agoraphobia, bipolar disorder and dysthymia, as well as for the most common disorders, such as social phobia and major depressive disorder. The increase in anxiety and mood disorders over the last decade is in line with observations from other studiesReference Yu, Zhang, Wang, Sun, Jin and Liu8–Reference Twenge, Cooper, Joiner, Duffy and Binau10 but these studies were not able to differentiate and evaluate different types of anxiety and mood disorders. The most comparable study is the Australian National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing,Reference Slade, Vescovi, Chapman, Teesson, Arya and Pirkis26 which, like NEMESIS, used the WMH-CIDI diagnostic interview in both 2007 and 2020–2022 waves. They also reported a significant increase in the 12-month prevalence of both anxiety (odds ratio 1.40) and mood disorders (odds ratio 1.30), particularly among young adults aged 16–25 years. These findings mirror our own, where we also observed a somewhat stronger increase in prevalence among younger adults (18–34 years). Together, these results point to a broader international trend of rising common mental disorders, especially in younger people. Recent Danish health register data also showed higher incidence rates for mood and anxiety disorders in more recent birth cohorts and higher calendar periods, especially in the younger ages.Reference Momen, Beck, Lousdal, Agerbo, McGrath and Pedersen15

Clinical characteristics of disorders over time

From our findings, it becomes clear that the increase in 12-month prevalence of anxiety or mood disorders does not seem to be due to an increase in reporting of less severe cases. The overall severity of these disorders remained stable, and there was even a slight increase in the mean number of disorders and in mental health care utilisation per affected individual with anxiety or mood disorders from 2007–2009 to 2019–2022. The latter could partially reflect that seeking mental health care has become more normative over time, with greater capacity and accessibility in primary care now available for those with mental health problems.Reference Ruths, Haukenes, Hetlevik, Smith-Sivertsen, Hjorleifsson and Hansen12,Reference Forslund, Kosidou, Wicks and Dalman14 However, as our assessment of mental disorders is based on standardised psychiatric interviewing in a random, generalisable Dutch cohort, prevalence estimates are not dependent of or biased by medical care needs or services or clinician availability. Additionally, the reported age at onset was lower in the most recent period than 12 years earlier, which indicates that anxiety and/or mood disorders may emerge earlier in life or be recognised sooner than in earlier decades. Of note, there was a decrease in psychotropic medication use among persons with mood disorders and young people with anxiety or mood disorder, which could reflect a more prevailing tendency in Dutch healthcare to avoid prescribing medication too early during the disease course, and the preference in many Dutch people to treat mental disorders with psychotherapy instead of medication.Reference McHugh, Whitton, Peckham, Welge and Otto27,Reference Piek, van der Meer, Hoogendijk, Penninx and Nolen28 This approach may differ from that in some other Western countries, where medication use for mental health has generally increased. However, in the Netherlands mental health care use has been increasing in the last two decades through non-medication routes like psychotherapy.Reference Dros, van Dijk, Böcker, Bruins Slot, Verheij and Meijboom29 While this shift may have offset for reduced antidepressant prescribing, we cannot rule out the possibility that it played some role in the observed prevalence increase – though it is unlikely to fully account for the substantial rise.

Risk factors: changes in prevalence and impact over time

When investigating the absolute risk of sociodemographic, vulnerability and health-lifestyle risk factors, we did not observe a consistent and relevant change over the time period from 2007–2009 to 2019–2022. Some risk factors were slightly more prevalent (drug and alcohol use disorders, high education), whereas other risk factors were less prevalent (low education, smoking). The decline in low education may be attributed to increased public spending on education between 2006 and 2016 and the reduction in smoking, which was equally notable among both young and older adults, could be attributed to the introduction of stricter anti-smoking policies over the last decade which have led to a steady decline in smoking rates since 2003.30,Reference Willemsen and Been31 Of note, alcohol and drug use disorders saw a substantial increase, especially in younger adults. This illustrates that the increase in mental disorders is not restricted to anxiety and mood disorders but may be general across common mental disorders. The increase in alcohol and drug use disorders is despite stricter legislation and policy developments targeting alcohol and drug use in the Netherlands, although adherence to these measures was found to be limited.32 While there has been a shift towards higher education levels in the population, this is unlikely to explain the observed increase in disorder prevalence, as higher education is generally associated with a lower risk of anxiety and mood disorders.Reference Li, Allebeck, Burstöm, Danielsson, Degenhardt and TA33 This interpretation is supported by our results. Additionally, increased awareness and a willingness to acknowledge mental health problems may play a role, but the use of structured clinical interviews focused on symptom criteria reduces the influence of social desirability or stigma. The vast majority of the risk factors we examined – 10 out of 14 – showed minimal change in prevalence (<20%). Consequently, we suggest it is unlikely that change in the absolute impact of our measured risk factors contributed to the observed increase in anxiety or mood disorder prevalence.

When examining the same risk factors to assess any changes in relative risk over the years (NEMESIS-2 versus NEMESIS-3), we did not find substantial differences either. Most risk factors were consistently positively associated with the presence of any anxiety or mood disorder, with overweight/obesity being the only exception in both studies. Interaction analyses, testing whether risk factors were differentially linked to anxiety or mood disorder risk across the two NEMESIS studies, revealed that age, childhood trauma and absence of a paid job were significantly different in their association, with absence of a paid job consistently showing a larger relative risk in NEMESIS-3 than in NEMESIS-2, according to both multiplicative and additive interaction. This could indicate that unemployment in the past years – with unemployment rates being at a historical low34 – may have been less the norm in recent years than a decade earlier, which could explain why the impact on mental health was found to be stronger in NEMESIS-3. However, out of the 14 additive and 14 multiplicative interactions tested, only four were significant, which could very well represent a chance finding. Overall, the very limited and small changes we observed in both the relative impact as well as the absolute impact of the examined risk factors, cannot have contributed much to the large increase in anxiety and mood disorder prevalence that was observed from 2007–2009 to 2019–2022.

It is also important to note that although part of NEMESIS-3 was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, many interviews (N = 1576) occurred beforehand which yielded similar prevalence estimates. This aligns with recent diagnostic studiesReference Penninx, Benros, Klein and Vinkers17 that found no consistent increase in mental disorders during the pandemic, making it unlikely that our findings are due to COVID-19.

Strengths and limitations

This study enhances the existing literature by using the clinically validated CIDI 3.0, based on DSM-IV criteria,Reference Haro, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Brugha, De Girolamo, Guyer and Jin35 to assess trends in anxiety and mood disorders over time. A strength of our study is the use of both additive and multiplicative interaction analyses, providing a more comprehensive assessment of whether and how risk factors differentially relate to disorder prevalence over time. A broad range of risk factors was analysed, offering a comprehensive examination of their contributions to trends; however, the scope was limited by the available variables, excluding factors such as social media use, pressure to succeed and resilience, which may significantly influence mental health.Reference Haidt36 The relatively small sample size for young individuals with psychopathology may have reduced the power of age-stratified analyses, potentially causing us to miss associations. Due to the observational nature of this study, the findings reflect associations rather than causal relationships, and causality cannot be directly determined. Moreover, while this study focused on anxiety and/or mood disorders, further research should investigate other mental disorders in greater depth.

Although our findings suggest higher prevalence in 2019–2022 compared to 2007–2009, we cannot confirm a continuous trend over the 12-year period due to the absence of data between the two cross-sectional assessments. We therefore acknowledge that only two time-points are available, and we can only draw general conclusions about trends across this period, rather than changes that may have occurred in the intervening years. However, evidence from a prior study based on intermediate NEMESIS-2 follow-up waves within the same initial cohort suggests a steady increase in anxiety and mood disorders during those years.Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten, Luik and de Graaf16 Additionally, we acknowledge that a small proportion of participants in NEMESIS-3 (approximately 8.1%) were interviewed online via video calls due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, prior research suggests that video-based interviews yield data comparable to face-to-face interviews,Reference Davies, LeClair, Bagley, Blunt, Hinton and Ryan37 and no significant differences in 12-month and lifetime prevalence rates were observed between participants interviewed via video call and those interviewed in person, even after adjusting for sociodemographic differences.Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten, Luik and de Graaf16,Reference ten Have, Tuithof, van Dorsselaer, Schouten and de Graaf19 Finally, although the response rate in NEMESIS-3 was lower than in NEMESIS-2, this decline seems to reflect a broader trend of decreasing participation in survey research over time, and weighting procedures were applied to minimise potential bias.Reference Eggleston38

In conclusion, this study confirmed that the 12-month prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders – across all their subtypes – has significantly increased between 2007–2009 and 2019–2022. Differential clinical characteristics, or a different absolute or relative impact of sociodemographic, vulnerability and health-lifestyle risk factors could not explain this increase. This suggests that the increase in anxiety or mood disorders represents a valid trend. This is an alarming signal, given the societal impact of these disorders. Close monitoring and robust population-based studies are necessary to determine whether the increasing prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders is consistent across countries and cultures. Meanwhile, our findings highlight the importance of effective mental health prevention programmes and strategies to prevent chronicity by ensuring timely treatment or specifically addressing risk factors contributing to this concerning rise.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10454

Data availability

The data on which this manuscript is based are not publicly available. However, data from NEMESIS are available upon request. The Dutch Ministry of Health financed the data and the agreement is that these data can be used freely under certain restrictions and always under supervision of the principal investigator of the study. Thus, some access restrictions do apply to the data. The principal investigator of the study is the second author of this paper and can at all times be contacted to request data. At any time, researchers can contact the principal investigator of NEMESIS and submit a research plan, describing its background, research questions, variables to be used in the analyses and an outline of the analyses. If a request for data sharing is approved, a written agreement will be signed stating that the data will only be used for addressing the agreed research questions described and not for other purposes.

Author contributions

M.T.H. and B.W.J.H.P. obtained funding for studying this particular research topic. All authors contributed to the conception, design and interpretation of analysis for this manuscript. A.G. and M.T.H. undertook the analyses for this manuscript and A.G. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.G., M.T.H., N.M.B., A.I.L. and B.W.J.H.P. discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages. All authors contributed extensively to and have approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The NEMESIS study is conducted by the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos Institute) in Utrecht. Financial support for both studies (NEMESIS-2 and NEMESIS-3) has been received from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. The funding source had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. This study was conducted within the framework of the EU-funded projects EarlyCause and To-aition. B.W.J.H.P. is supported by the research project ‘Stress in Action’ (www.stress-in-action.nl) which is financially supported by the Dutch Research Council and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (NWO gravitation grant number 024.005.010). Open access funding provided by Amsterdam UMC Location VUmc.

Declaration of interest

None.

Transparency declaration

The lead and second author confirm that this manuscript provides an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study. No important aspects of the study have been omitted.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.