Introduction

Conspiracy theories, or “beliefs that a group of actors are colluding in secret to reach a malevolent goal,” have a long and storied history in the United States (Imhoff et al., Reference Imhoff, Zimmer, Klein, António, Babinska, Bangerter, Bilewicz, Blanuša, Bovan, Bužarovska, Cichocka, Delouvée, Douglas, Dyrendal, Gjoneska, Graf, Gualda, Hirschberger, Kende, Kutiyski and van Prooijen2022, p. 392). In recent years, new conspiracy theories have emerged surrounding events like the 2020 presidential election, school shootings, and coronavirus disease 2019, but conspiracy theories have always been a ubiquitous part of American life, with some even dating back to the colonial era (Olmstead, Reference Olmstead and Uscinski2018). Despite the longstanding role of conspiracy theories in American society, the creation and spread of conspiracy theories have changed in important ways over time.Footnote 1 With the advent of social media platforms, for instance, it is now possible for people to develop and spread conspiracy theories much more rapidly and easily than in the past. There has also been growth in the extent to which political elites have been willing to share misinformation and conspiracy theories (Macdonald & Brown, Reference Macdonald and Brown2022). Former President Donald Trump and numerous members of Congress, for example, espouse and disseminate conspiracy theories, with social media platforms often being a key way that they engage in conspiratorial dialogue.

The development and distribution of conspiracy theories has generated significant uneasiness among many scholars, policymakers, civic groups, the media, and the general public. According to recent survey data, 73% of Americans feel that conspiracy theories have spiraled “out of control,” with 59% perceiving that such beliefs are more prevalent today than 25 years ago.Footnote 2 As conspiracy theories become more widespread in public discussions and media coverage, concern has mounted about the potential consequences of support for conspiracy theories. According to Uscinski et al. (Reference Uscinski, Enders, Diekman, Funchion, Klofstad, Kuebler, Murthi, Premaratne, Seelig, Verdear and Wuchty2022), “Conspiracy theory beliefs are associated with numerous societal harms, including vaccine refusal, prejudice against vulnerable groups, and political violence” (p. 1). It is therefore important to understand why some people are supportive of conspiracy theories and why others are not. While researchers have been increasingly interested in the underpinnings of support for conspiracy theories, Uscinski et al. (Reference Uscinski, Enders, Diekman, Funchion, Klofstad, Kuebler, Murthi, Premaratne, Seelig, Verdear and Wuchty2022) have noted that “Scholars still have much to discover about the psychology of conspiracy theory beliefs” (p. 17).

In this research note, we add to the growing literature on the individual-level factors that are related to support for conspiracy theories. Using data from a university-sponsored survey (university name omitted for peer review) fielded in October 2023, we examine the role of two different dimensions of anxiety in shaping support for conspiracy theories. More specifically, we examine whether general anxiety and/or political anxiety influence conspiracy theory support. Our interest in general versus political anxiety is motivated by research on the impact of generalized trust and political trust on conspiracy theory support. While early research, such as the work by Goertzel (Reference Goertzel1994), found that belief in conspiracy theories was associated with a lack of interpersonal trust (also called generalized trust), scholars have also explored whether measures of trust related to politics predict support for conspiracy theories (e.g., Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Waite, Rosebrock, Petit, Causier, East, Jenner, Teale, Carr, Mulhall, Bold and Lambe2022; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Saunders and Farhart2016). Numerous previous studies (e.g., Green & Douglas, Reference Green and Douglas2018; Krüppel et al., Reference Krüppel, Yoon and Mokros2023), including a recent meta-analysis (Bowes, Costello, & Tasimi, Reference Bowes, Costello and Tasimi2023), have found a link between general anxiety and support for conspiracy theories, but we are not aware of research that has examined whether feelings of anxiety about politics are related to conspiracy theory support. In the next section, we provide an overview of previous research and our expectations. We then discuss our data and measures before turning to our results. We end with a discussion of the implications of our findings and several ideas for future research.

Previous research and expectations

Generalized anxiety and conspiracy theory support

Several studies have examined the connection between feelings of general anxiety and support for conspiracy theories. As a brief overview, anxiety is typically defined as an emotional state where “individuals appraise a situation as being unpleasant, highly threatening, and uncertain” (Gadarian & Albertson, Reference Gadarian and Albertson2014, p. 134). Scholars have generally hypothesized that there will be a positive association between anxiety and conspiracy theory support. The basic idea is that “conspiracy theories provide simplified, causal explanations for distressing events” and “by reinstalling a sense of order, control, and predictability…conspiracy theories help individuals to regulate their own negative emotions” (Swami et al., Reference Swami, Furnham, Smyth, Weis, Lay and Clow2016, p. 72). To date, numerous studies have found evidence of a statistically significant relationship between anxiety and belief in conspiracy theories (e.g., Green & Douglas, Reference Green and Douglas2018; Grzesiak-Feldman, Reference Grzesiak-Feldman2013; Krüppel et al., Reference Krüppel, Yoon and Mokros2023; Leibovitz et al., Reference Leibovitz, Shamblaw, Rumas and Best2021). Importantly, a recent meta-analysis by Bowes, Costello, and Tasimi (Reference Bowes, Costello and Tasimi2023) found that across 17 different studies, the average correlation between anxiety and support for conspiracy theories was statistically significant r(26,348) = 0.19, p < .001. Put simply, there is evidence of a small, positive relationship between general measures of anxiety and the endorsement of conspiracy theories.

Political anxiety and support for conspiracy theories

While research on the underpinnings of support for conspiracy theories has explored the role of both generalized trust and political trust, scholars have yet to explore whether both generalized and political anxiety are related to support for conspiracy theories. The anxiety measures highlighted in the previous section tend to focus on how much anxiety people are feeling in general and do not focus specifically on how much anxiety they feel about politics. Recently, Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Weinschenk and Panagopoulos2024) developed a measure that is designed to capture the extent to which features and situations associated with the contemporary political environment make people feel anxious. Given that “a high proportion of conspiracy theories are political in nature” (van der Linden et al., Reference van der Linden, Panagopoulos, Azevedo and Jost2021, p. 24), we expect that political anxiety will be related to support for conspiracy theories. Previous research suggests two possible ways that anxiety about politics might be related to conspiracy theory endorsement.

On one hand, people who are anxious about politics may be more inclined to support conspiracy theories than their counterparts. As we noted above in the discussion about general anxiety, one idea about why anxiety is related to conspiracy theories is that such theories provide comfort in the face of distressing events. Politics may be a source of distress, and people who are more politically anxious may be more inclined to support conspiracy theories than their counterparts. Indeed, political anxiety likely occurs due to uncertainty or perceived threats in the political environment, and conspiracy theories may be appealing because they seem to provide a coherent explanation for complex or chaotic political situations. On the other hand, people with high levels of political anxiety could be less inclined to support conspiracy theories because their anxiety about the political environment pushes them to seek out evidence-based information and reliable sources—as a way to reduce uncertainty and apprehension. This is consistent with MacKuen et al. (Reference MacKuen, Wolak, Keele and Marcus2010), who argue that anxiety can increase reflection and learning and lead to more systematic information processing.

Given the previous research outlined above regarding generalized anxiety, we are particularly interested in understanding whether both political and general anxiety are correlated with conspiracy theory support or whether one dimension seems to be more important than the other as a predictor of support for conspiracy theories.

Control variables

Although we are primarily interested in understanding the relationship between general anxiety, political anxiety, and conspiracy theory support, we include a variety of control variables in the empirical models that follow to make sure that our findings are robust to potential confounding variables. Since this is a research note and we want to focus on the key ideas discussed above, we provide an overview of expectations and previous findings for the control variables in the Supplementary Material. As a quick overview, we include the following controls in our empirical models: conspiracy mindset (designed to capture the general predisposition to see the world through a conspiratorial lens), left-right ideology, ideological extremism, interpersonal trust, trust in Donald Trump, trust in Joe Biden, political knowledge, educational attainment, age, income, sex, and media habits (frequency of social media, television, radio, and newspaper usage).Footnote 3

Data and measures

Participants

To study support for conspiracy theories, we make use of original data that we collected as part of a university-sponsored survey that was in the field between October 16 and 21, 2023.Footnote 4 The sample is based on 451 Wisconsin residents who completed the survey online.Footnote 5 For this study, we used Dynata, a commonly used online survey panel. We compared various demographic measures in our dataset to US Census estimates for Wisconsin as a check on the sample representativeness.Footnote 6 Overall, we found that the demographic composition of our sample was fairly similar to the state, although our sample was a bit more educated and a bit older. Following informed consent, we had respondents complete a CAPTCHA (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart). This is designed to stop bots from completing the survey. Additionally, very early in the survey, we asked an attention check question (respondents were asked to choose a particular response to demonstrate attentiveness).Footnote 7 Incorrect responses to the question led to survey termination (and the data from these respondents was not used). The survey was relatively short with an average completion time of 9.16 min.

Measures

Below, we provide an overview of how each of the key concepts of interest is measured. Again, to save space, detailed descriptions of how each control variable was measured (along with descriptive statistics) are provided in the Supplementary Material for interested readers. The Supplementary Material also includes a correlation matrix showing the interrelationships among all of the study variables.

Support for conspiracy theories

To measure our dependent variable, we created an index based on support for seven different conspiracy theories. We selected questions that have previously been used in the conspiracy theory literature (with the goal of choosing a range of different topics that also span different periods of time). More specifically, we asked respondents whether they agreed with the following statements: (1) Jeffrey Epstein, the billionaire accused of running an elite sex trafficking ring, was murdered to cover-up the activities of his criminal network (from Enders et al., Reference Enders, Uscinski, Seelig, Klofstad, Wuchty, Funchion and Stoler2023b); (2) Groups of scientists manipulate, fabricate, or suppress evidence in order to deceive the public (from Brotherton et al., Reference Brotherton, French and Pickering2013); (3) Humans have made contact with aliens and this fact has been deliberately hidden from the public (from Enders et al., Reference Enders, Farhart, Miller, Uscinski, Saunders and Drochon2023a); (4) School shootings, like those at Sandy Hook, CT, and Parkland, FL, are perpetrated by the government (from Enders et al., Reference Enders, Uscinski, Seelig, Klofstad, Wuchty, Funchion and Stoler2023b); (5) People in the federal government either assisted in the 9/11 attacks or took no action to prevent the attacks (from Stempel et al., Reference Stempel, Hargrove and Stempel2007); (6) The results of the 2020 presidential election were illegitimate (from Sances, Reference Sances2023); and (7) The dangers of 5G cellphone technology are being covered up (from Enders et al., Reference Enders, Uscinski, Seelig, Klofstad, Wuchty, Funchion and Stoler2023b). For each respondent, we counted the number of conspiracy theories that they supported and then divided that number by the total so that we would have a measure capturing the proportion of theories supported. The measure ranges from 0 to 1 (M = 0.37, standard deviation [SD] = 0.30) and has a reliability score of α = 0.71. In short, the measures do tend to “hang together” reasonably well despite the fact that they cover a broad set of topics and time periods. Consistent with previous research, the distribution of the measure of support for conspiracy theories exhibits a positive skewness.

Generalized anxiety

To capture generalized anxiety, we asked survey respondents the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 item (GAD-2) battery, which was created by Spitzer et al. (Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2007).Footnote 8 The GAD-2 asks respondents, “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? (1) Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge; (2) Not being able to stop or control worrying.” For each item, the response categories were as follows: not at all, several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day. We combined responses from the two items into an index that ranges from 0 to 1, where higher numbers indicate greater anxiety (M = 0.32, SD = 0.30). The two items correlate at r(450) = 0.79 (p < .001). As noted by Sapra et al. (Reference Sapra, Bhandari, Sharma, Chanpura and Lopp2020), “The GAD-2 questionnaire has been validated in multiple studies and shown to retain the excellent psychometric properties of the GAD-7 [Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item battery]” (p. 5).

Political anxiety

To measure political anxiety, we used Smith et al.’ (Reference Smith, Weinschenk and Panagopoulos2024) political anxiety battery. Respondents were asked: “How much anxiety does each of the following give you: (1) The election of a disliked candidate or political party, (2) The level of polarization and conflict in the current political climate, (3) That the American public is insufficiently informed about politics, (4) That you care too much about politics, (5) That you are insufficiently informed about politics, (6) The poor quality of political leaders/candidates, (7) The uncivil nature of modern politics, (8) The extent to which ordinary people are disinterested in politics.” Responses to each item were recorded on a 1–10 scale, where 1 corresponded to “no anxiety at all” and 10 corresponded to “a great deal of anxiety.” We combined the 10 items into an index and scaled it from 0 to 1 where higher values indicate more anxiety toward politics (M = 0.58, SD = 0.22). The reliability score for the measure was α = 0.89.

Results

Given that our dependent variable ranges from 0 to 1, we use Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models. Before turning to our main results, though, it is worth briefly noting that the correlation between our general anxiety measure and our measure of political anxiety is fairly modest at r(450) = 0.21 (p < .001). Thus, although there is a positive association between the two measures of anxiety, it is also clear that they are not capturing the same concept.

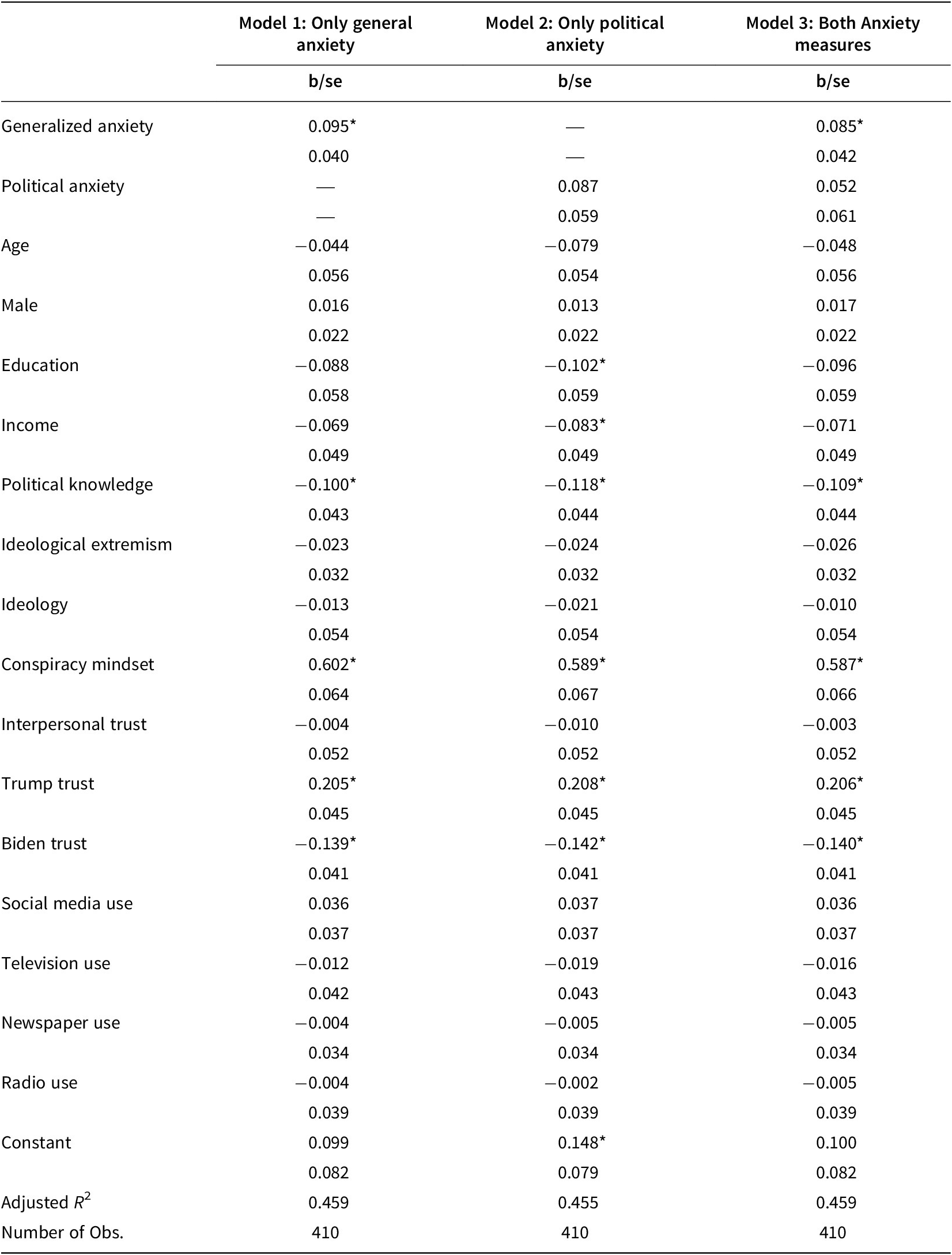

In Table 1, we present the results of three regression models. In model 1, we use the general anxiety measure and the controls. In model 2, we use the political anxiety measure and the controls. Additionally, in model 3, we use both anxiety measures and the controls.Footnote 9 The results in model 1 indicate that generalized anxiety has a positive and statistically significant effect (p < .05, one-tailed) on support for conspiracy theories. This is consistent with the meta-analysis results reported by Bowes, Costello, and Tasimi (Reference Bowes, Costello and Tasimi2023), who found that the average correlation between anxiety and support for conspiracy theories was statistically significant but “smaller than expected given the hypothesized theoretical import” (p. 281). Overall, the substantive effect of general anxiety on conspiracy theory support is quite modest in our dataset. When anxiety takes on its lowest value, the predicted proportion of conspiracy theories supported is 0.32, and when it shifts to its highest value, the predicted proportion is 0.42.

Table 1. Impact of general anxiety and political anxiety on support for conspiracy theories

Note: * indicates statistically significant at p < .05 (one-tailed).

Model 2 provides a look at the association between political anxiety and support for conspiracy theories (in the absence of general anxiety). While political anxiety is positively related to conspiracy theory support, the coefficient is not statistically significant. In contrast to our expectations, political anxiety does not appear to exert an important impact on conspiracy theory support. Even when the political anxiety measure is used as the sole predictor of conspiracy theory support, the coefficient is tiny (b = 0.007, standard error = 0.065) and not statistically significant (p = 0.917). Model 3 includes both measures of anxiety and confirms the story told by the first two models. Support for conspiracy theories is influenced by generalized anxiety but not political anxiety. Indeed, the coefficient for the general anxiety measure is statistically significant (p = 0.021), while the coefficient for the political anxiety measure is not (p = 0.40). As a robustness check, we estimated models (presented in the Supplementary Material) where each of the seven conspiracy theory measures is used as a separate dependent variable. Overall, the results of those models indicate that political anxiety is never a statistically significant predictor of conspiracy theory support. It is worth noting that while generalized anxiety is always positively signed across the models, it is not always statistically significant. In fact, in the models where each conspiracy theory is used as a separate dependent variable, two of the conspiracy theories appear to be driving the generalized anxiety finding in Table 1. In short, the impact of generalized anxiety is driven primarily by the questions about alien contact and the 2020 election being illegitimate. While the meta-analysis by Bowes, Costello, and Tasimi (Reference Bowes, Costello and Tasimi2023) found that the impact of anxiety on conspiracy theory endorsement was similar when looking across different types of dependent variables (i.e., when comparing the impact of general anxiety on general conspiracy ideation measures versus indices that tap support for specific conspiracy theories), it may be worth measuring a wider range of conspiracy theories within the confines of a single study to see whether and how the effects of different independent variables vary across many different conspiracy theories.Footnote 10 It is not immediately clear to us why people who are more anxious would be particularly inclined to support conspiracies related to aliens or elections, but examining a wider array of conspiracy theories (or asking numerous questions about similar topics within the same survey) might provide some interesting insights in future studies. We note that Bowes, Costello, and Tasimi (Reference Bowes, Costello and Tasimi2023) found that the effects of some variables differ depending on whether general conspiracy theory ideation measures (e.g., “Government agencies secretly keep certain outspoken celebrities and citizens under constant surveillance”) were used as dependent variables or whether indices focusing on specific theories were employed (although their study did not disaggregate either type of measures to examine each component of the measures). For instance, they found that the effect of extraversion was significantly larger when using measures based on specific conspiracy theories compared to measures that capture the general tendency to support conspiracy theories. Although we believe that indices capturing conspiracy theory support are valuable (e.g., due to increased reliability), we would encourage future researchers to examine each item within indices separately, as such analyses could reveal interesting patterns about the predictors of conspiracy theory support.

Discussion and future research

In this article, we examined how two different measures of anxiety—generalized and political anxiety—were related to support for conspiracy theories. We found that political anxiety was not an important predictor of conspiracy theory support and that generalized anxiety was weakly (and somewhat inconsistently) related to conspiracy theory support. While there are good reasons to be concerned about the ill effects of political anxiety—Smith (Reference Smith2022) has shown that about half of US adults say politics is a significant source of stress and can lead to lost sleep, shortened tempers, and obsessive thoughts—political anxiety does not appear to be strongly related to conspiracy theory endorsement. Still, it is important to note that our results underscore the point that general feelings of anxiety in everyday life can influence support for at least some conspiracy theories.

We believe that there are a number of avenues for future research on conspiracy theory support. First, since some of the variables examined here (e.g., political anxiety) have not been explored in previous studies, we encourage replication studies. It will be important to examine whether similar findings emerge in other samples and contexts. Until our findings are replicated in larger samples, they should be viewed as preliminary. Second, we would encourage additional research on the timing of when people start believing (or abandoning) conspiracy theories. Since our data are cross-sectional in nature, we were only able to study why people exhibit different levels of support for conspiracy theories. By collecting panel data, it may be possible to learn about what prompts people to start believing conspiracy theories and what leads people to stop supporting conspiracy theories. It would be particularly interesting to better understand whether changes in psychological factors (e.g., increased or decreased anxiety) correspond to changes in support for conspiracy theories. Given the important effects that conspiracy beliefs can have (e.g., Uscinski et al., Reference Uscinski, Enders, Diekman, Funchion, Klofstad, Kuebler, Murthi, Premaratne, Seelig, Verdear and Wuchty2022), additional research in these areas would be worthwhile.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/pls.2025.10011.