Introduction

During the early post-war period, socialist Yugoslavia initiated several projects to promote its national image to make the country more visible in the international community. It aimed to create an image of a newly established communist country that was striving to develop and modernise in many ways. Propagating Yugoslavia culturally was predicated on showing its efforts in building socialism and its socialist achievements. Among these early post-war cultural diplomatic efforts, the Youth Labour Action (ORA) played a crucial role. It was used to attract leftist young people and sympathisers in Britain and other countries in the West to promote Yugoslavia.

The ORA mobilised both domestic and foreign youth. Although the latter comprised only a relatively small number of participants, their symbolic meaning was significant as it served to ‘propagate communist ideas among youths from the West, as well as to strengthen ties with “friendly” countries’.Footnote 1 While similar initiatives took place in other People’s Democracies, Yugoslavia’s use of the ORAs was distinctive. Promoting the ORAs abroad as well as inviting the foreign youth to participate enabled the Yugoslav government to develop its soft power by transforming an economic project into a cultural vision for the country, while also establishing a national cultural brand in Britain and the West.Footnote 2 Viewing foreign brigadists as potential promoters of the country, the Yugoslav government invited foreign youth to participate in construction work and experience the building of socialism first hand. The propagandistic effect – through press coverage, celebration events and related publications – made the participation of foreign youth ideal for Yugoslavia’s cultural offensive. In addition, film screenings, exhibitions with books and other materials related to the ORAs, particularly the 1947 Šamac–Sarajevo railway, were organised in Britain.Footnote 3

Using the case study of the Šamac–Sarajevo railway in 1947, this article highlights the cultural dimension of the ORAs within early post-war Yugoslav cultural diplomacy (1946–51). The time frame centres on the 1947 construction of the Šamac–Sarajevo railway and its continuing influence following the return of the British brigades to Britain in 1948. The article aims to demonstrate how Yugoslavia employed its ORAs to promote the image and secure recognition of its socialism. It argues that Yugoslavia’s aim to ideologically cultivate British youth to enhance its prestige through the ORAs was only partially successful. Although the project served as a symbolic calling card for socialist Yugoslavia, it also revealed discrepancies between official ideals and the realities experienced on the ground. In addition to the usual top-down perspective of the state in cultural diplomacy, this article approaches Yugoslav cultural diplomacy from a bottom-up perspective, looking into its implementation through individual agency. By inviting British youth to participate in the construction project, Yugoslav authorities sought to promote the country from a grassroots perspective, fostering international friendship. Like many international communist initiatives of the time, the youth railway was designed to demonstrate that ideological and political divisions could be overcome through goodwill and internationalism. In this sense, the ORAs were not merely about physical labour or economic development; their ideological and political significance was central. As Selinić has argued, the presence of the foreign youth primarily served political purposes, supported by varied educational programmes and organised tours showcasing Yugoslavia’s natural beauty and political system.Footnote 4

The Yugoslav government was aware of the propagandistic effect of both the construction projects and the role played by the foreign youth. As stated in the 1947 meeting of the Ideological Commission of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, the building of the youth railway in Bosnia-Herzegovina was counted as the ‘greatest merit’ of that year, and similar ‘big and beautiful object and action’ should be made to attract attention from abroad.Footnote 5 In the same year, the Information Directorate at the Federal Government provided the materials on the Šamac–Sarajevo youth railway for the quarterly bulletin Yugoslavia Today and Tomorrow published by the British–Yugoslav Association (BYA) in London.Footnote 6

The BYA played a significant role in bilateral cultural relations at that time, as much of Yugoslavia’s cultural work in Britain was implemented and organised with the BYA. It also maintained close contact with the Yugoslav Embassy in London. The BYA aimed to facilitate friendship between the two countries and served as the primary channel for Yugoslavia’s cultural contact with Britain. Similar to other friendship societies with communist countries, most BYA members were either members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) or left-wing fellow travellers. Because of this, the Foreign Office regarded it as an affiliate of the CPGB. The BYA was one of the main organisations in Britain responsible for enrolling and organising brigades to go to Yugoslavia. Many young members of the BYA were also brigadists who travelled to Yugoslavia for reconstruction work. This included a member of the CPGB, future historian E.P. Thompson. As commander of a British brigade at the Šamac–Sarajevo railway, Thompson was keen on introducing socialist Yugoslavia and edited the pamphlet The Railway, introducing life on the railway construction site after, he came back to Britain in 1948.Footnote 7

The ORAs were closely linked with Yugoslavia’s communist ideology and served as a cultural symbol of the communist value system. For instance, the ideal of being a Stakhanovite, disciplined shock worker (udarnik), was integral to the ORAs. Its educational and ideological importance was emphasised as a character that a socialist ‘new man’ should possess.Footnote 8 Andrea Matošević has argued that those ‘shock workers’ became the ‘embodiment of the dignity of the labour movement of the entire country’, with the ‘shock worker movement’ being ‘imbued with political significance’ that had a lasting influence long after its popularity in the early post-war years faded.Footnote 9

Since the state identified Yugoslav culture very broadly, a wide range of activities that could raise the country’s cultural profile were promoted. These included documentary film screenings on youth life, the country’s natural beauty, social and agricultural development, cultural and artistic life, as well as feature films centred on partisan themes.Footnote 10 The Yugoslav government also organised concerts and arranged guest visits as part of its broader cultural offensive. These events usually had a propagandistic character and revolved around themes of socialist construction, often highlighting the ORAs. The limited diversity of these initiatives suggests that Yugoslav authorities arguably lacked a clearly articulated vision for the scope and objectives of cultural diplomacy in the late 1940s. The engagement of British youth in the ORA projects represented an initial attempt by Yugoslavia to explore how to promote its image. Thus the ORAs became a key testing ground for Yugoslavia’s cultural diplomacy.

There is a rich historiography on the topic of international youth gatherings during the Cold War. Studying cross-border youth activities can help us better understand post-war politics, society and culture. For many, youth represented an idealistic life stage; as historians Mischa Honeck and Gabriel Rosenberg write, ‘young people were found to be politically and culturally impressionable and unburdened by the past’.Footnote 11 Young people were specially targeted as potential cultural messengers during the Cold War, making their experiences of cultural exchange an important part of Cold War cultural history.

The majority of the literature on international youth activities from a cultural perspective focuses on the role of international youth organisations, conferences and youth festivals in facilitating national governments’ cultural diplomacy in Cold War politics. In particular, this literature has emphasised how international youth festivals became a kind of cultural battlefield for countries with differing ideological and political systems.Footnote 12 In general, these works approach the topic through the lens of the cultural Cold War, understood as a competition between the East and the West to promote their culture or lifestyle to surpass ‘the other’ and win the hearts and minds of the public from the other side of the Iron Curtain.

For instance, Pia Koivunen uses the 1957 Moscow World Festival of Youth as a case study to document how the Soviet Union took the opportunity to propagate a new post-Stalin image.Footnote 13 Margaret Peacock highlights how the Soviet Union attempted to generate a brand-new vision of communism after Stalin for both domestic and international audiences at the 1957 Festival.Footnote 14 Similar research includes the study of the American cultural offensive at the World Youth Festival in Helsinki in 1962 and the evolution of West German cultural diplomacy at the World Youth Festivals during the 1960s to attract Third World youth.Footnote 15 Andrea Chiriu tracks the Italian government’s concerns about communist propaganda at the 1953 World Youth Festival in Bucharest.Footnote 16

In addition to exploring the high politics of governments during this period, Pia Koivunen studies Finnish youth at the World Festival of Youth. She contends that the majority of the Festival attendees were motivated by the idea of ‘peace and friendship’.Footnote 17 Young people could have different agendas compared to the top organisers of these events. The competitive dimensions of propaganda were usually initiated from the perspective of high politics. Similar to this non-state actors’ perspective, Richard Jobs studies how independent youth mobility contributed to the process of European social and cultural integration from post-war reconstruction to Cold War confrontation.Footnote 18

As part of Yugoslavia’s early post-war cultural offensive, the ORAs were highly ideologically driven and had a strong propagandistic character. However, Yugoslavia’s ORAs differed from international youth festivals in several ways. The arrangement of foreign youth participation in Yugoslavia’s ORAs had a less festive dimension and focused more on daily labour work and the life of individual youth, which had a less ‘performative’ character compared to international festivals. Although sports events, dances and campfires were routinely held at the ORAs, the primary method for familiarising British and foreign brigadists with the country was through educational programmes and outings to factories, cooperatives and other sites.

The role of the ORAs in Yugoslavia’s domestic policy is well established in scholarship. The majority of the literature on this topic adopts a domestic perspective, emphasising the significance of the ORAs in the ideological cultivation and mobilisation of Yugoslav socialist youth as well as their political and economic functions.Footnote 19 This was a crucial part of Yugoslavia’s ORAs and the main goal to be achieved. In some studies, the ORAs have been considered ritualised to the extent that they were believed to be a form of returning ‘to the sacrifice of the Partisans and the “gift of freedom” of the Communists . . . [and] in direct continuity with the People’s Liberation Movements’.Footnote 20 Lyubomir Pozharliev expresses a similar view, interpreting the ORAs as ‘a new ritual supporting the ideology’. According to him, the socialist identity was imposed on youth by ritualising and mystifying collective action, enabling young people to ‘see and touch the ideological norm through the objectivation of the norms labour’. He also argues that the Brotherhood and Unity Highway functioned as ‘a tangible symbol of the peaceful coexistence of the various Yugoslav peoples and of their new common Yugoslav identity’.Footnote 21 The concept of ‘ritualisation’ is also discussed by Nikola Baković, who introduces the idea of ‘ritualised mobilities’, which refers to the mobility of people in socialist Yugoslavia along the precisely established routes that were symbolically charged and ideologically significant. These routes connected places associated with symbolic meaning for Yugoslav socialist patriotism such as the People’s Liberation Struggle and espoused the ideological principles of brotherhood and unity.Footnote 22

However, little has been done on the role of the ORAs in Yugoslavia’s cultural diplomacy, especially with Britain. For the studies of the international volunteers, Tea Sindbæk Andersen argues that the movement was a ‘relatively successful instance of cultural diplomacy at the individual level’, as evidenced by the positive feedback from her interviewees.Footnote 23 Similar positive feedback was also shown in official reports from Yugoslavia. The use of working construction projects to foster international friendship was not unique to Yugoslavia. Richard Jobs observes that, in post-war West Europe, transnational youth travel was encouraged through the proliferation of international work camps, as the internationalism of European youth was seen as essential to Europe’s future peace and reconciliation.Footnote 24

Recent scholarship on British youth participation in Yugoslavia’s ORAs includes the publication of the Serbo-Croatian translation of E.P. Thompson’s booklet The Railway and the accompanying volume The Spirit of the Railway (Duh pruge), which brings together several studies related to Thompson’s booklet, aiming to interpret their experience of socialism from a post-socialist perspective. Martin Pogačar highlights how the construction of the railway embodied Yugoslavia’s technopolitical ambitions, giving rise to ideologies of progress (a better future) and brotherhood and unity.Footnote 25 Ivan Rajković approaches The Railway as an ethnographic work, describing it as a ‘documentary description created after thorough participation in the processes’.Footnote 26 Reana Senjković notes the potential shift in tone between testimonies given by members of the British brigades immediately after the ORA and those given decades later. The latter tend to be more critical, which may reflect the changing social and political contexts in which these memories were later recalled.Footnote 27

The materials used in this article are mainly official reports of the People’s Youth of Yugoslavia (PYY) in the Archives of Yugoslavia in Belgrade. While it is necessary to approach these materials with some scepticism due to the ideological conditions under which they were written, they should not be dismissed as mere propaganda without value for researchers. These texts reflect the temporal situation of the Cold War and the texture of cultural issues at that time. The comments and evaluations of the British brigades by the PYY delegates reveal a discrepancy between Yugoslavia’s communist ideology and the intended ideological education of the British youth. For instance, British youth thought it was unnecessary to arrive and leave work in formation, while the Yugoslav delegate believed it was related to the basic work discipline of the brigade. British youth insisted on arranging the brigade’s issues in a democratic way (such as holding meetings and voting), which the PYY delegate viewed as excessive and bourgeois. These documents do not simply present an idealistic story but also show the tensions and conflicts that arose during the encounters between Yugoslav and British youth.

This article is divided into the following three sections: the background of the ORA; the case study of the Šamac–Sarajevo railway in 1947; and the stories of the brigades back to Britain and E.P. Thompson’s booklet.

Background of the Omladinska Radna Akcija

The organisation of the post-war ORAs in the form of work brigades was not unique to socialist Yugoslavia. In the Eastern Bloc, where communist parties held power, this approach was commonly used to engage youth in national construction projects. Some projects were completed solely by domestic voluntary youth, but it was also common to invite foreign youth to participate. For instance, young delegates from various countries helped rebuild the devastated Czech village of Lidice and construct the new town of Litvinov in 1947 while attending the World Youth Festival in Prague. Similarly, young people travelled to Bulgaria, Poland and Yugoslavia to take part in these efforts.Footnote 28 Participating in construction work became a trend in post-war socialist countries.

The ORAs in Yugoslavia lasted from the end of the Second World War until the 1980s, though their character evolved. The heyday of youth voluntary work was during the early years after the war. Key projects included the construction of the Brčko–Banovići railway (1946), the Šamac–Sarajevo railway (1947), the Doboj–Banja Luka railway (1951), the ‘Brotherhood–Unity’ highway between Belgrade and Zagreb (1948–1949) and the construction of New Belgrade and the university town in Zagreb. Yugoslavia’s Youth Labour Actions evolved into a symbol of the country and its socialist ethos, playing a significant role in both its domestic policy and cultural diplomacy, especially in the early years after the war.

Early youth construction projects (from the late 1940s to early 1960s) mainly focused on the construction of railways, motorways and industrial complexes.Footnote 29 Youth Labour Actions during the late 1940s were part of the broader developmental process of the entire country under the leadership of the communist party.Footnote 30 Yugoslavia initiated its first Five-Year Plan (also the first one outside the Soviet Union) in 1947, focusing on developing industry.Footnote 31 This period also marked the heyday of the ORAs in Yugoslavia. The Brčko–Banovići railway in 1946 was the first major voluntary ORA, and the construction of the ‘Brotherhood–Unity’ highway between Belgrade and Zagreb (1948–1949) was the largest project at that time in terms of the number of participants and the scope of construction.Footnote 32 These infrastructure projects were mainly undertaken by local students, rural youngsters and workers due to the need for a large workforce.Footnote 33 Foreign brigades also contributed to these projects.

The ORAs were carried out by volunteers aged between 16 and 25, who formed youth brigades and worked at construction sites to build ‘socialism’. The use of the slogan ‘we are building the railway, the railway is building us’ as the major part of the propaganda for the 1947 youth railway project Šamac–Sarajevo reflected the ideological goal of the project – to cultivate the new socialist man. The government attached great importance to these actions not only for their economic benefits but also for their political, educational and propagandistic functions.Footnote 34 This was especially the case during the early post-war period. Practically, a great deal of labour was needed for reconstruction, as the whole country had been devastated by the war. Politically, the construction sites and the organised brigades provided a perfect venue for the youth to become disciplined, dedicated and supportive of socialist ideals and ideology, such as the spirit of the collective and brotherhood and unity. The educational courses and programmes of the youth actions contributed to general education and combatting illiteracy.Footnote 35 For Yugoslav youth, participating in these labour actions was a point of pride and was seen as contributing to the building of their country and its socialism. The ORAs were also seen as a useful tool in ‘erasing disparities between social milieus – rich and poor, urban and rural, and diminishing cultural differences between Yugoslav ethnicities’.Footnote 36 In general, these projects were pivotal in popularising communist ideology and consolidating the party’s rule.

The youth work actions also became a symbol of Yugoslav socialism. As part of Yugoslavia’s cultural diplomacy, they were extensively promoted abroad. The ORA projects attracted many foreigners, including governmental officials, cultural workers and celebrities, who came to visit the construction site. Yugoslav authorities also took the opportunity to invite interested foreign youth to participate in the construction projects, allowing them to experience Yugoslav socialism first hand. Such initiatives were popular under the banner of early post-war international peace and friendship and were closely related to the rise and popularity of communism and left-wing ideas in Europe.

Yugoslavia’s connection with the European Left can be traced back to the inter-war period. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia had a lively left-wing intellectual culture in the cities of Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana. Despite the government repression of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in 1921, publications promoting European ‘radical political and aesthetic ideas and intellectual networks that reached from Paris to Prague to Petrograd’ continued to circulate.Footnote 37 Leftist literature and left-wing intelligentsia were directly inspired by ideals in Soviet and German literature, searching for cultural paradigms in art and science in Western society.Footnote 38 The left-wing magazine New Literature ‘systematically tried to introduce the domestic public to writers who raised social issues and advocated internationalism’.Footnote 39 Members of the intelligentsia under the influence of modernism were also left-leaning and participated in the Yugoslav liberation movement during the war, later becoming party elites active in the cultural field, especially after 1950.Footnote 40 In addition, the Spanish Civil War strengthened Leftist Internationalism, as ‘Tito...and many other leading political, military and diplomatic figures in communist Yugoslavia, had either fought on the republican side in Spain or had been involved in organising the participation, showing the internationalist position of the Yugoslav volunteers’.Footnote 41

These leftist connections were deepened during the Second World War and continued after the Communist government of Yugoslavia was established. For instance, with help and financial support from Swedish leftists, the Association of Yugoslavs in Sweden, ‘Free Yugoslavia’, with headquarters in Stockholm, was formed in January 1944. The Swedish communist paper Ny Dag reported on its founding meeting. Members were mainly Yugoslav fugitives (the majority of them partisans who fled from the Nazi concentration camp in Norway) in Sweden. In cooperation with the Norwegian Association and the Danish Association, the task of ‘Free Yugoslavia’ was to ‘connect with ideologically programmatically related organisations in Sweden’. Several publications, including Informacioni list, Aktivista and a journal for cultural issues, Novi Svet, were printed.Footnote 42 The relations made between ‘Free Yugoslavia’ and Swedish left-wing parties ‘laid the foundations of Yugoslav–Swedish relations after 1945’.Footnote 43 Such relations with the Left were also reflected in ORAs when many Scandinavian youth volunteers came to participate in railway construction.Footnote 44 There were other forms of cultural cooperation with Western European leftists such as French communists, which were conducted through communist organisations similar to the BYA and other channels.

With the leftist influence, the ORAs became popular among European youth, leading many British youngsters to volunteer in Yugoslavia. The People’s Youth of Yugoslavia (PYY), the youth organisation in Yugoslavia, arranged the work of the brigades.Footnote 45 They sent invitations to youth organisations in Britain, asking them to help with the organisation of the brigades. The youth committee of the British–Yugoslav Association (BYA) and the National Union of Students (NUS) were the main organisations responsible for recruiting the brigadists in Britain. The NUS, a national student organisation dedicated to domestic student issues, also maintained communication with foreign student organisations. Compared to the BYA, the NUS was more neutral because its members came from diverse backgrounds, although left-wing ideas were strong within the organisation after the war.Footnote 46The British brigadists were usually registered through the joint committee of these two organisations. In addition, the Youth Communist League (YCL) sometimes participated in the organisational work.Footnote 47

Many young Britons formed brigades and came to help with the building of Yugoslavia during the late 1940s and early 1950s.Footnote 48 In addition to the British brigades, there were also brigades from neighbouring countries and the West, including Albania, Hungary, Greece, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, the Scandinavian countries, Belgium and France. According to the report in the Times Weekly Edition, more than 400 British students and workers participated in the building of the youth railway in 1947.Footnote 49 Nevertheless, it should be kept in mind that Yugoslav ORAs were primarily undertaken and completed by domestic youth volunteers. The participation of foreign youth in these projects was more symbolic and propagandistic than their actual contribution.

During the construction of the Šamac–Sarajevo railway in 1947, foreign volunteers were invited to work for three weeks in Yugoslavia, followed by a one-week holiday, as described in an article in the Times Educational Supplement. The author praised this initiative as it ‘render[ed] the full fruition of the idea of the United Nations and the establishment of conditions for lasting peace’.Footnote 50

The motivations of foreign youth coming to Yugoslavia were usually a mix of idealistic pursuit, political concerns and curiosity about the country. However, for many young Britons, the prospect of a free holiday in Yugoslavia was also a significant factor. When the Yugoslav delegate to the First British Brigade at the Belgrade–Zagreb highway asked several brigadists why they came to Yugoslavia, he found their answers generally overlapped:

First, this was an extraordinary opportunity to visit Yugoslavia cheaply (trip, summer holiday). Then, people in England are interested in what life behind ‘the Iron Curtain’ looks like. They come to see how communist social and economic system looks like in practice, with the emphasis on planned economy. Besides, the British communist youth considered it their duty to come to Yugoslavia.Footnote 51

Nevertheless, he was convinced that the first reason was the major motivation. According to the Yugoslav report of the Third British Brigade in 1951 on the Doboj–Banja Luka railway working site, ‘whoever wanted to go to Yugoslavia paid 18 pounds and went’.Footnote 52 Furthermore, Yugoslavia was a place that many Britons knew little about. Interest in the country consisted of both tourist curiosity and a desire to understand its society, politics, economics and culture.

Meanwhile, the political concerns of the British brigadists shifted over time in response to changes in international politics. This was particularly evident in the 1948 and 1949 brigades, when the feeling of solidarity among the young communists gave way to growing suspicion toward Yugoslav socialism following the expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Cominform in June 1948.Footnote 53 The legitimacy of the Yugoslav communist party was challenged after its rupture with the Soviet Union. The Cominform Resolution also created a tense political atmosphere throughout the country, prompting the PYY to intensify its political work towards the British brigades. In this context, the ORAs became a platform for ‘changing the mind of the [British] brigadists’ regarding the Cominform Resolution.Footnote 54 By 1951, the majority of the youth who came to Yugoslavia were Labourites. They were mostly interested in the reforms initiated by the Yugoslav government and local culture, such as folk art. Political enthusiasm and idealism waned afterwards due to changes in international politics as relations with the British communists cooled down due to the Yugoslav–Soviet split. When the PYY resumed the ORA in 1958, only two young English workers went to Yugoslavia to work in the international brigade. British youngsters were unwilling to spend their holidays doing labour in Yugoslavia once the ideological attractiveness disappeared.Footnote 55

In addition to labour, the daily life of the British brigades consisted of lectures, discussions and conferences as part of the educational programmes. Topics covered Yugoslavia’s socialism, such as social and economic systems, the Five-Year Plan, the Peasant Work Cooperatives and so on. These events were intended to introduce Yugoslav socialism to British youth and cultivate a friendly feeling towards the country. The opinions of the British brigadists about Yugoslavia were influenced by their respective political affiliations. Despite the apparent political character of the projects, the voluntary labour actions still provided young Britons with an opportunity to satisfy their curiosity about the newly established socialist country.Footnote 56

The Šamac–Sarajevo Railway

The Šamac–Sarajevo railway was inaugurated on 16 November 1947 by Tito. It was 240 kilometres in length and completed within seven months, thanks to the effort of voluntary youth groups from Yugoslavia and other countries.Footnote 57 Young people from Britain, France, Canada and Australia helped build the youth railway.Footnote 58 International brigades arrived in Yugoslavia during the summer, working for several weeks before travelling to the Dalmatian coast for a break as a reward.Footnote 59 By inviting the foreign brigade, the Yugoslav government regarded the railway construction as a valuable tool for propaganda.Footnote 60 This is evidenced in a letter from the Central Committee of the People’s Youth of Croatia to all district committees, dated 24 April 1947: ‘this year, many countries will come to the construction of the youth railway brigades, delegations and groups of foreign youth. Their visits and stay in our country are of great importance not only for our youth organisation but for our homeland in general’.Footnote 61 Tito also confirmed that the participation of foreign youth raised ‘the reputation of [their] country in the eyes of the whole world’.Footnote 62

Britain sent a total of ten brigades.Footnote 63 According to an internal report of the PYY, between 1 April and 15 November 1947, 471 English individuals came to work on the Šamac–Sarajevo railway, accounting for 8 per cent of the total participants. England also sent the largest number of youth to work in Yugoslavia compared to other Western countries. Among the 471 young people, 112 were workers, two were peasants, and 357 were intellectuals and others.Footnote 64 This demonstrates the strong momentum of internationalism among young British students, who were the major participants in such international projects. This also marked the heyday of post-war youth internationalism between the British Left and Yugoslavia, particularly in 1947 and 1948, when the Yugoslav communist party attached great importance to cultivating friendship and building cultural relations with the potential ‘propagandists’ of the country.Footnote 65

The majority of the British brigadists in 1947 were either young communists or leftists. Enthusiastic about the post-war peace, friendship and internationalism propagated by the Soviets, they were idealistic and believed they could contribute to building a better world. Therefore, many participated in events such as the World Youth Festival and the volunteer brigades to strengthen international friendship and communication.Footnote 66 Communists and leftists believed these large-scale gatherings could serve as a useful platform for youth around the world to ‘learn from each other’. For instance, thirteen hundred Britons came to participate in the World Youth Festival in Prague in 1947.Footnote 67

Curiosity about the country and the idea of having some fun motivated many British youth to come to Yugoslavia. As one member of a British brigade later wrote in the Times, ‘What most I had looked for, I suppose, and certainly my husband and I, was the chance to satisfy a natural curiosity about Yugoslavia’.Footnote 68 The organising secretary of the British Brigade at the Šamac–Sarajevo railway, Dorothy Sale, also described the intentions of the young British people who worked in Yugoslavia. According to Sale,

Some people had come out of curiosity, some with a vague idea of doing some kind of social work, some to study the politics of the new Yugoslavia, some wanted a holiday with hard physical work, some just wanted a holiday, some came with all sorts of odd reasons ‘to study the Yugoslav at home’, or ‘to observe the impact of the West on the East’.Footnote 69

From these accounts, it is clear that most British participants gave little thought to the labour work they were about to undertake in Yugoslavia. Their curiosity about the country likely stemmed from a mix of interest in its natural beauty (particularly the Dalmatian coast) and a desire to see the construction site as a scenic symbol of socialism. The Yugoslav government welcomed these British visitors for their potential role as informal propagandists. Echoing its ideological goals for domestic youth, the railway construction site served as a place where young people, who might otherwise never meet, could interact and, in doing so, cultivate a sense of brotherhood and unity.

The British brigadists were struck by many aspects of their experience in Yugoslavia. Upon arrival, they were immediately taken aback by the enthusiasm of the local youth for their reconstruction efforts. The dedication of the local brigades, who worked diligently to become shock workers and shock brigades, was surprising. Political slogans, banners featuring the hammer and sickle and portraits of communist leaders were all new to the Britons. In this sense, political messages were sent through slogans, and the competitive spirit embedded in the shock worker/brigade system served to demonstrate the prestige: ‘being a shock brigade meant being a hero’.Footnote 70 These scenes of Yugoslav socialist reality naturally became propaganda tools used to present the country’s socialist identity to British youth, as an experience they rarely encountered at home. As such, the ORA became a platform for convincing foreign visitors of the authenticity of building socialism.Footnote 71

Work on the railway proved challenging for the British youth, as it often involved heavy labour. While technically intensive work was undertaken by more skilled workers, most international brigadists were assigned to physical work, such as ‘digging or moving soil in wheelbarrows’.Footnote 72 The brigadists were unfamiliar with the norms and tasks, finding it difficult to undertake the work efficiently. The constant changes in the composition of the brigade worsened the situation.Footnote 73 In addition to the demanding work, they had to endure the summer heat in Bosnia, to which the majority of the British were not accustomed. As one brigadist noted,

they lived in wooden huts and slept on straw palliasses. Getting up at 5 A.M., they worked for 8 hours until 1 pm with a break at 9 A.M. The food supplied was basic, with coffee or tea and a hunk of maize bread and a sticky sweet preserve for breakfast. Lunch might be a bowl of stew or some raw cabbage and a slice of Spam or similar tinned meat.Footnote 74

The poor conditions of accommodation and food did little to improve the situation, even though they were arguably the best that could be expected in post-war Yugoslavia.Footnote 75 Moreover, it was also difficult for the brigadists to adapt to the collective way of life at the working site. As one brigadist wrote:

As most of the brigade was ex-service and heartily tired of acting in a group, this meant at first that there was little organisation in evidence. People tended to be determinedly individual and drift off on their own private concerns. For a week or two, there was a distinct lack of cohesion and a general unhappy feeling of ‘muddling through’ in the good old British fashion.Footnote 76

The Yugoslav side apparently did not hold a favourable view of the British brigadists’ work performance. According to a PYY report, their work was considered poor, and they ‘constantly insisted on occasionally leaving the Railway and travelling around the country’.Footnote 77 The brigadists were also criticised for failing to adapt to collective life and for their unwillingness to live a common life. There was little control over individual personalities, and their independence and discipline were described as very weak.Footnote 78 The PYY also complained about the careless enrolment of brigadists from Britain: ‘there were many hostile elements, provocateurs and agents in it’.Footnote 79 Although the PYY delegate admitted in the report that the vast majority of brigadists came to the railway with a ‘sincere intention to work and help’, the outcome of the brigade’s work was not that good.Footnote 80

The comment by the PYY reveals a discrepancy between its goal of ideologically cultivating and engaging British youth with socialist ideas through labour, and the actual outcomes. The effort to build the identity of the ‘new socialist man’ – as was attempted with Yugoslav youth – through the strictly regulated daily life of the brigades and the merging of personal and collective identities through shared work experience did not realise as expected. The symbolic gesture of British youth participation could not compensate for the fact that their practical contribution was minimal.

In addition to the hard physical work and discipline, educational programmes and various recreational activities were organised for the British brigades. The organised lectures and discussions constituted a significant part of the political-ideological promotion of socialist Yugoslavia towards the British youth. Lecture topics included the youth railway and its significance, the Five-Year Plan, the People’s Youth of Yugoslavia and Yugoslav cultural and educational policy.Footnote 81 The PYY delegate considered the lecture on ‘The New Type of Democracy’ to be a great success and satisfied that the brigadists ‘tried to get as many favourable arguments as possible in terms of Yugoslavia and its democracy’.Footnote 82 The brigadists were reported to show great interest in the topics ‘new democracy’, ‘constitution’ and ‘people’s government’. Discussions following the lectures and general discussions about Yugoslavia were regularly held in the brigade.Footnote 83 The educational programmes were one of the most crucial non-labour programmes in promoting Yugoslavia and its socialist vision through the most explicit means of ‘influencing youth by exposing them to and indoctrinating them in the official ideology’.Footnote 84

The diverse recreational activities, including film shows, chess competitions, sports events and physical training, tended to create an atmosphere of communication and understanding among the young people from various countries. Orchestras and dramatic companies from the cities visited the line, and volunteers produced their own concerts, sketches and plays.Footnote 85 As one British brigadist remarked:

We grew to like and appreciate the different nationalities for their differing and particular characteristics. The Yugoslav students were as earnest about their play as about their work. You had to be careful when inviting a Yugoslav to a friendly game of chess or you would find yourself engaged in an international tournament, but when they relaxed they sang and danced with the cheerful abandon of the rest.Footnote 86

Another brigadist, Martin Eve, who was a communist as well as the choirmaster at the railway, recollected such experience: ‘there were more things than work on the Youth Railway’.Footnote 87 In his eyes, the railway also provided an opportunity to cultivate friendship and informal cross-cultural communication among young people of different nations.

These cultural activities represented another important aspect of promoting Yugoslavia among British youth. By involving brigades from diverse cultural backgrounds and various parts of the world, they embodied the ideological emphasis on brotherhood and unity, an ideal that extended to the fostering of international friendship and ‘international anti-fascist identification’.Footnote 88 At the same time, they highlighted the diversity of participants in the ORAs. Through film screenings and gathered dance, brigadists were introduced to Yugoslav folk culture as a living tradition, reinforcing both national sentiment and the value of Yugoslav traditional culture.

Back in Britain And Thompson’s The Railway

When brigadists returned from the railway, they often gave lectures on their impressions of Yugoslavia, spoke at press conferences and wrote articles about their experiences for newspapers.Footnote 89 Many of these articles appeared in the CPGB daily newspaper, the Daily Worker, which effusively praised the Youth Labour Actions and socialist Yugoslavia.Footnote 90 For instance, a short note written by a returned brigadist emphasised that they ‘had never seen such liberty and democracy as they had seen there [in Yugoslavia]’.Footnote 91 The painter Paul Hogarth, a CPGB member, published an illustrated article in the National Coal Board trade union magazine Coal (see Figure 1), introducing the Šamac–Sarajevo railway to miners in Britain. In the article, he introduced the general situation in Yugoslavia and how Bosnian miners and students from mining colleges contributed to the construction of the railway.Footnote 92

Figure 1. The article ‘Miners Help to Build a Railway’, written by Paul Hogarth in the magazine Coal Magazine (NCB), Apr. 1948, 20. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence V3.0; https://www.ncm.org.uk/collections/research/digitised-coal-magazine.

Interest in the country among some brigadists, especially communists, did not ebb afterwards. B. Champeney, a member of the CPGB at Bristol University, sent a letter in February 1948 to the Central Council of the PYY, requesting a regular subscription to the Information Bulletin, a PYY brochure circulated in England.Footnote 93 The PYY, keen to promote both itself and the country, accepted Champney’s request and even offered to send more copies to his friends who were also interested in Yugoslavia.Footnote 94 Similarly, brigadist P.G. Myers asked for the booklet ‘The Five-Year Plan of FNRJ’ and other literature about industrial and agricultural issues.Footnote 95

The BYA also organised social events after the brigadists returned from Yugoslavia. A reunion party in December 1947 was held for the brigadists who had worked on the Šamac–Sarajevo railway. Celebrities from Britain and staff from the Yugoslav Embassy in London were invited. The event featured selected performances from British concerts given on the railway, mass singing of Yugoslav songs and an exhibition of drawings and photos of the youth railway.Footnote 96

Despite these efforts by enthusiastic youth and the BYA to promote Yugoslavia in Britain, some Britons remained sceptical. Using Youth Labour Actions to promote Yugoslavia’s image sometimes had the opposite effect. This scepticism was reflected in an article published in the Scottish newspaper the Scotsman:

The minimum result on any healthy young folk who elect to spend a holiday this way must be to infuse in them the idea that the democratic Federal Republics of Yugoslavia are doing a great job. It is also a fair guess that, intermingled with the discussion groups and the lecture, goes a fair mixture of political indoctrination.Footnote 97

The author of the article, Patrick Maitland, was suspicious of the project. He compared the construction work to paramilitary training of an international brigade intended to fight in Greece and reiterated that it was merely indoctrination.Footnote 98 His attitude may have been influenced by his political views as a conservative and his previous working experience. Maitland had been a special correspondent in the Balkans and Danubian area for the Times during 1939 and 1941. Later, he joined the Political Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office, where he ran the Yugoslav Department from 1943 to 1945.Footnote 99

Similar distrust of the Yugoslav government was common. The Scotsman published letters from both supporters and opponents of such labour actions. Among these letters, Violet M. Henderson, a brigadist, held an opposite view:

The suggestion that we were subjected to Communist indoctrination during our stay is quite false. We had lectures – arranged entirely by one of our own brigade – on Yugoslav literature, education, the Five-Year plan, the Partisan war against the Germans; we attended classes in Serbo-Croat, and we had many opportunities of becoming acquainted with Yugoslav culture through the concerts at which young Yugoslavs revealed to us the wealth of their folk songs and dances.Footnote 100

However, another brigadist, C.M. Coles, disagreed and explicitly expressed strong distaste. He compared Yugoslav youth to the Hitlerjugend and likened the work in Yugoslavia to brainwashing. He condemned the forced labour camps and religious persecution in Yugoslavia and was suspicious of the freedom of speech and press as well as the non-democratic political system.Footnote 101

Among the supporters of Youth Labour Actions in Yugoslavia, E.P. Thompson, the returning brigadist and the future historian, was enthusiastic about promoting socialist Yugoslavia in Britain and fostering mutual understanding and a sense of community between the people of Britain and Yugoslavia. As a CPGB member and the commander of a British brigade, he was keen on building communist internationalism and friendship through the Šamac–Sarajevo railway project and attempted to improve the working performance of the brigade during their stay in Yugoslavia.

According to a Yugoslav report in September 1947, the group spirit and work performance of the British brigadists gradually improved as Thompson became the newly elected commander and had ‘a clear line of work’.Footnote 102 Thompson took the brigade work seriously and regarded it as a valuable opportunity to ‘seek inspiration and hope’ from the socialist East.Footnote 103 On the occasion of his departure from the youth railway, he sent a letter to all the builders:

Be assured that when we leave your country we shall not betray the friendship we have made here…. It is therefore of very great importance that we should have come here, and that you should have greeted and received us as comrades. Every one of us is going home to tell his friends the truth about your country. We shall strive to change the foreign policy of the British Government, to pull down the flag of imperialism and to hoist the flag of friendship. We shall succeed in our struggle. Perhaps we shall not succeed this year, perhaps we shall not succeed next year either; but we shall succeed.Footnote 104

Thompson’s letter was not merely an expression of goodwill as a communist internationalist. It fulfilled precisely the role the Yugoslav state expected from a foreign participant: that of a cultural diplomat. His letter was published in Politika, one of Yugoslavia’s most prominent newspapers.

As promised in his farewell speech, Thompson made considerable efforts to promote summer work projects after returning to the United Kingdom. His experiences in Yugoslavia and other People’s Democracies made him think about the development of communism in Britain. In a letter to a Yugoslav friend, he believed ‘it was important to help the British people understand in human terms the problems of the new democracies and how they were being solved’.Footnote 105 He edited and published a booklet named The Railway: An Adventure in Construction through the CBGP-sponsored BYA (see Figure 2).Footnote 106

Figure 2. The front cover of The Railway; ‘Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [1948]’, 2057 E. 10.

Thompson described the booklet as ‘one of the first detailed (as opposed to general and theoretical) descriptions of an aspect of life in Yugoslavia prepared by British eye-witnesses’.Footnote 107 He emphasised the journalistic method adopted in the book and even tried to pre-empt the possible ill-intentioned interpretations by stating that ‘This book is not propaganda’.Footnote 108 Nevertheless, reflecting Thompson’s own membership in the CPGB, the narratives in the book were almost all provided by communist youth. The BYA, which published the book, was sponsored by the CPGB and had a close relationship with the Yugoslav Embassy. Even though he insisted that the booklet’s main purpose was to inform more people about Yugoslavia, it still aroused suspicion from MI5, which had been monitoring the activities of the CPGB throughout the war, viewing it as communist propaganda.Footnote 109 MI5 was not the only one in the country suspicious of the book. A Sunday Times correspondent described it as ‘undisguised and almost undiluted Communist propaganda’. This article, with its obvious anti-communist tone, warned that the BYA’s sponsorship included members of Parliament.Footnote 110

In a report from MI5, it was noted that Thompson’s speech in Yugoslavia ‘spoke completely in Communist style’. He promised that ‘in England he would defend Yugoslavia of today against British reactionaries. It is therefore quite clear that all this delegation [youth brigades] will be very useful to the Yugoslav Embassy in London for their propaganda in Britain’.Footnote 111 At that time, as the Cold War was on the horizon, anti-communist sentiment was on the rise in British political circles in the decade following the war.Footnote 112 It is not surprising that The Railway was suspected of the propaganda from the ‘red menace’.Footnote 113

However, The Railway neither became a landmark work in Thompson’s oeuvre nor was it actively promoted by the Yugoslav state, either domestically or internationally.Footnote 114 The booklet faded along with the post-war ‘labour action fever’. It remains unclear how such a representative account of the ORA fell into obscurity. One can only speculate that this may have been a consequence of the 1948 Yugoslav–Soviet split, during which the CPGB sided with the Soviet Union and the BYA distanced itself from Yugoslavia. Another possible reason is Thompson’s growing disillusionment with communism, which culminated in his withdrawal from the CPGB in 1956. Nevertheless, his attitude toward the youth railway experience remained unchanged over the years.Footnote 115 Despite its inherently propagandistic character, The Railway offered a comprehensive depiction of life and work in the camp, as seen through the eyes of left-wing eyewitnesses. It also played a role – albeit a limited one – in advancing Yugoslav cultural diplomacy in Britain.

Photos from the Times Weekly Edition and the Times Educational Supplement (see Figures 3–6) captured the spirit of the youth railway construction that the Yugoslav government intended to convey: the unceasing developmental momentum of the people and the country and the international friendship with enthusiastic young Britons.

Figure 3. British students (of both sexes) participating in the work on the railway, on their way to attend a meeting of the foreign brigades; The Times Weekly Edition [London], 8 Oct. 1947, 11, ‘Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [1947]’, N. 22,893 B. 3.

Figure 4. Building a bridge over the river Bosna; The Times Weekly Edition [London], 8 Oct. 1947, 11, ‘Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [1947]’, N. 22,893 B. 3.

Figure 5. Students at work in a cutting; The Times Weekly Edition [London], 8 Oct. 1947, 11, ‘Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [1947]’, N. 22,893 B. 3.

Figure 6. The construction of the youth railway; The Times Educational Supplement [London], 11 Oct. 1947, 537, ‘Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [1947]’, N. 26,011 B. 2.

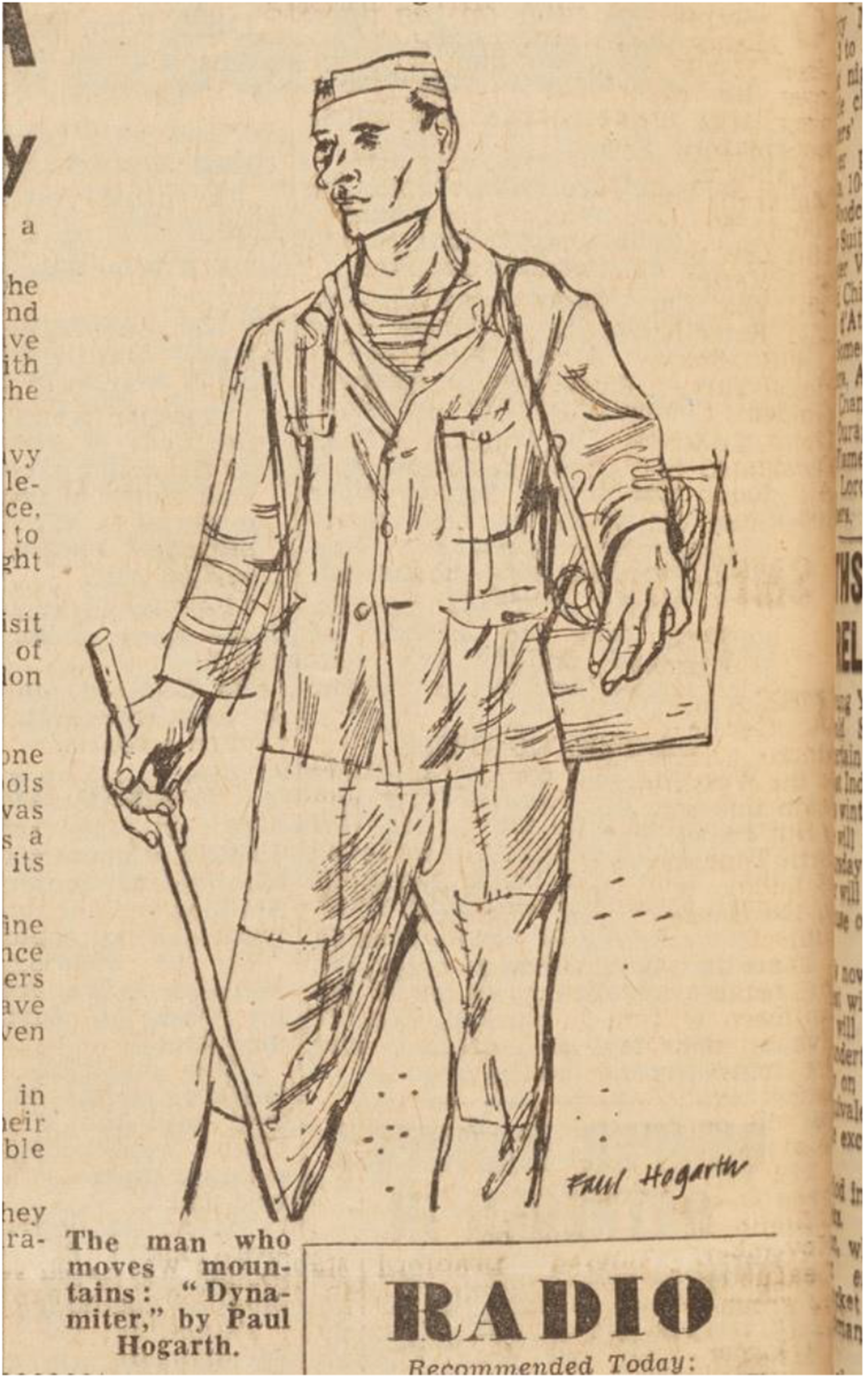

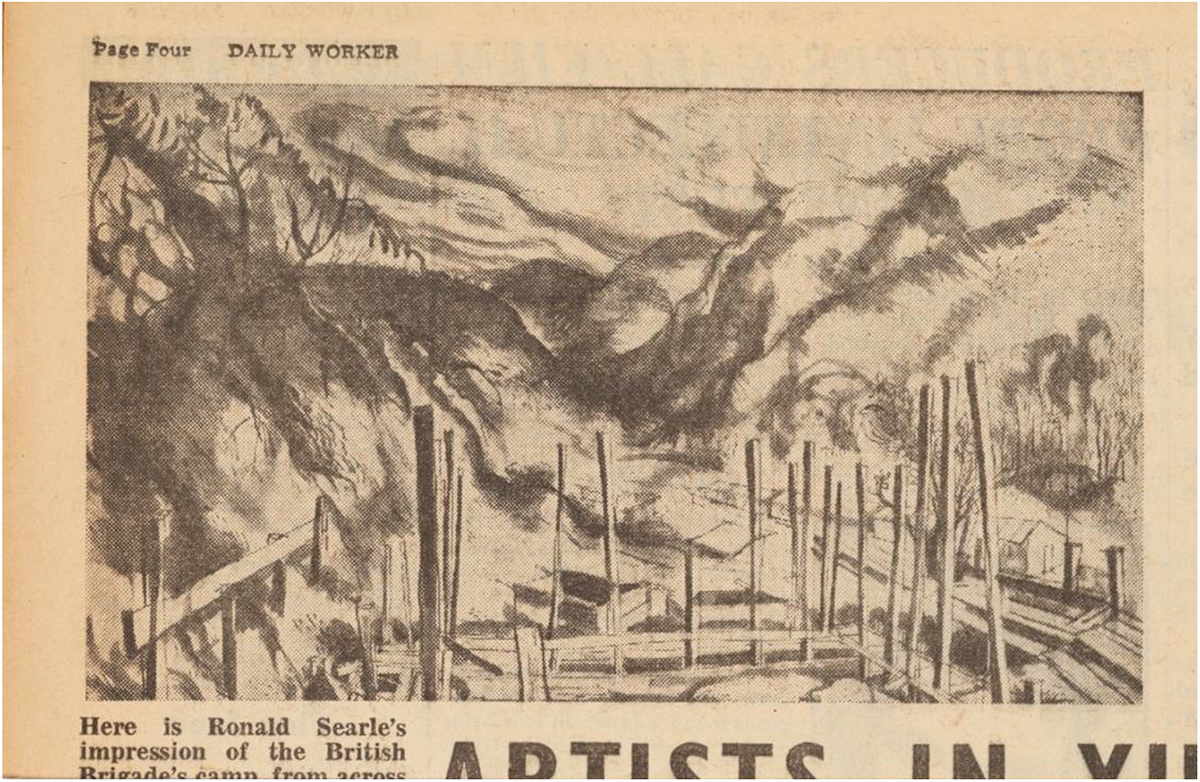

Like these photos, illustrations created by British artists complemented the narratives of the young brigadists (see Figures 7–10). These illustrations are typically charcoal sketches depicting the harsh conditions of the railway construction site with dirt-stained and patched clothing worn by the volunteers, and the simple, makeshift campsite where the youth were housed. They served as first hand depictions of the post-war youth labour actions in socialist Yugoslavia. Some British artists, including the communist painter Percy Horton and three others (Paul Hogarth,Footnote 116 Laurence Scarfe and Ronald Searle), visited the railway.Footnote 117 The major themes of the artwork typically depicted the large-scale construction site and the figures of the young brigadists from diverse working backgrounds. They later held an exhibition of their art depicting the railway and Yugoslavia at the Leicester Gallery in London in February 1948. There were sixty pieces exhibited, and the exhibition was opened by the Yugoslav ambassador. According to the report from the Yugoslav Embassy, the number of visitors was large, and the exhibition was very successful.Footnote 118

Figure 7. Drawing of men and women at work at the tunnel mouth; The Daily Worker [London], 29 Oct. 1947, 4, ‘Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [1947]’, N. 24,771 A. 5.

Figure 8. Harry Baines, ‘A Girl Volunteer’, The Daily Worker [London], 29 Oct. 1947, 4, ‘Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [1947]’, N. 24,771 A. 5.

Figure 9. Paul Hogarth, ‘The Man Who Moves Mountains: “Dynamiter”’, The Daily Worker [London], 29 Oct. 1947, 4, ‘Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [1947]’, N. 24,771 A. 5.

Figure 10. Ronald Searle, ‘The British Brigade’s Camp from across the Railway’, The Daily Worker [London], 29 Oct. 1947, 4, ‘Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford [1947]’, N. 24,771 A. 5.

Conclusion

The Yugoslav government attached great importance to the Šamac–Sarajevo railway. The participation of British brigades and other foreign youth drew international attention to the ORAs. The enthusiasm of British youth stemmed from the post-war atmosphere of the Grand Alliance with the Soviet Union as well as the wish to build a new world out of the destruction of the Second World War. For leftist youth, especially CPGB members, helping to build the railway during the summer fulfilled their wish to promote international friendship and cooperation. It was also a good opportunity to travel to an interesting place. Inviting British youth, especially leftists, was a useful strategy to cultivate a friendly attitude towards Yugoslavia and its regime. The Šamac–Sarajevo railway embodied communist internationalism and became a symbol of Yugoslavia’s communism and peaceful cooperation between the East and the West.

Working in Yugoslavia did increase British awareness of the country. This included both the left brigadists themselves and the general British public, who usually received information through press coverage. At this stage, conducting cultural diplomacy through youth labour actions was still exploratory. The brigadists’ experience was far more complex than the ideal life pictured in Thompson’s booklet, filled with contradictions and uncertainties. As historian Tea Sindbæk Andersen comments, ‘their [the international brigadists] experiences in Yugoslavia did not leave an impression of a repressive dictatorship, but rather one of authentic public support for the development of a new form of socialist society’.Footnote 119

Although the Yugoslav authorities sought to promote the country by integrating British brigadists into its socialist ideology through labour and political-ideological engagement, they remained dissatisfied with the loose organisation and undisciplined behaviour of the British participants. The gap between the ideal depicted by the enthusiastic brigadists and practical problems has always existed. The positive narratives of the young communists, however, were inevitably categorised as communist propaganda and viewed with suspicion by members of the British public. This was partly due to the nature of such collective physical work in a communist country during the rising Cold War. It is also worth noting that the actual contribution of the British brigades in terms of production was more symbolic than real, as the Daily Worker commented: ‘the work they did mattered less than the spirit in which they came’.Footnote 120

Nevertheless, British youth brigades were paid ‘the highest tribute’. Together with Danish youth, they were awarded ‘special diplomas for their efforts in the construction of the line and the strengthening of friendship and solidarity with the PYY and the builders of the line from other countries’.Footnote 121

The majority of British young people came to work in Yugoslavia out of curiosity, driven both by a natural touristic interest and an ideological pilgrimage to see a socialist country. Most of the British brigadists were ideologically committed communists eager to contribute to peace work and help with the construction of socialism. They were enthusiastic about going to Yugoslavia and seized the opportunity of the multinational gathering to realise communist internationalism. For the Yugoslav authorities, they represented ideal messengers for promoting the country and had the potential to help establish a positive image of Yugoslavia in Britain and other countries.

However, several problems persisted. The organisation of the brigades in 1947 was relatively poor due to the country’s underdevelopment. Food and accommodation remained consistent challenges during the brigadists’ travels amidst the country’s disorder.Footnote 122 In addition, the educational and cultural materials and programmes were inadequate and monotonous. Certain everyday frictions also highlighted the differences in mindset between the young people from Britain and Yugoslavia, for instance, the Yugoslav delegates’ repeated emphasis on ‘collectivism’ and ‘discipline’ as virtues of the socialist new man, and their dissatisfaction with what they perceived as the British brigadists’ ‘individualism’ and ‘bourgeois’ attitudes.

The heyday of the Youth Labour Actions and the participation of international brigadists was from 1945 to 1952. The peak of the British youth brigades was at the Šamac–Sarajevo railway in 1947. After 1952, the ORAs almost ceased due to being deemed economically unbeneficial, until their restoration by the Communist Party in 1958. These Youth Labour Actions were ‘closely related to all political, economic, social and ideological processes of the time’.

The ORAs provided a stage for Cold War politics to penetrate individual lives. Yugoslavia was seen as a special destination for building socialism, appealing to idealistic youth with its developmental momentum and the allure of a communist ideology absent in the capitalist West. To some extent, the ORAs facilitated mutual learning through lectures, discussions, trips, visits around Yugoslavia and daily camp life, even though in a seemingly propagandistic way.

At first glance, the building of youth railways may seem more like an economic and developmental issue than a cultural one. However, the construction of the Šamac–Sarajevo railway served as a calling card in many Yugoslav cultural events arranged with Britain: it was featured, for instance, in a painting exhibition of British artists held in London in 1948; in social events organised by the British–Yugoslav Association; and in a film documentary. In addition, many cultural activities were organised for the British brigades, such as introductions to Yugoslav folklore, outings to places of interest, campfires, choirs and discussions.

Therefore, it is essential to examine these ORAs through a cultural lens and as a bottom-up practice within Yugoslavia’s cultural diplomacy. As Yugoslavia’s first cultural diplomacy practice, the ORAs targeted British leftist youth. The Yugoslav authorities hoped that the participation of British brigadists and related cultural events could enhance their image in Britain.Footnote 123 However, the lack of a systematic cultural diplomacy framework and its strong propagandistic character made this goal difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, the ORAs functioned as a laboratory for Yugoslavia to develop its cultural diplomacy, gradually expanding its audience from British leftists to the general public.