While corporations are targets of contentious politics in much the same way as the state is, company responses to social mobilization and their consequences have received much less attention. In the mining sector, company responses to local protest may include advertising campaigns, distributive benefits, private environmental governance, and the establishment of mechanisms for public consultation, commonly captured by the term corporate social responsibility (CSR). However, such practices have mostly been understood by activists and scholars of extractivism as insincere “greenwashing” that aims to cynically manipulate local populations—amounting to little more than a public relations strategy (Leiva Reference Leiva2019; Clark and North Reference Clark, North, Clark and Patroni2006; Svampa et al. Reference Svampa, Sola Álvarez, Bottaro and Antonelli2010; 23CLSA).

We argue that firm responses to protest, seen in localized changes to corporate social responsibility practices, are an important and neglected part of the equation for understanding the effectiveness of social mobilization against mining in Latin America. In particular, we argue that firms should be considered as actors that potentially mediate between social movement pressures and policy (regulatory) outcomes, as other organizations have been (Amenta et al. Reference Amenta, Caren, Chiarello and Su2010; Silva Reference Silva2018). This article shows that at the mining project level, social mobilization can generate important changes in corporate practices toward nearby communities, and that these practices can undermine the cohesion of social movement coalitions advocating for regulatory intervention or reform, thus limiting their ability to make compelling claims on the state. In this way, company interpretations of and responses to protest are an important mediating process that conditions civil society efforts to activate state institutions in their favor.

Our argument extends recent work on the social foundations of regulation in Latin America (Hochstetler Reference Hochstetler2012; Amengual Reference Amengual2016; Abers Reference Abers2019; Brinks et al. Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2019; Amengual and Dargent Reference Amengual, Dargent, Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2020) to corporate actors by focusing on the key role of managers who struggle to translate activist demands into corporate practices. It also aims to identify the conditions that make corporate responses to protest more and less effective. More generally, it offers an explanation for the observation by quantitative researchers that frequently, mining projects neither generate much social conflict nor attract the regulatory attention of the state (Haslam and Ary Tanimoune Reference Haslam and Ary Tanimoune2016; Akchurin Reference Akchurin2020; Orihuela et al. Reference Orihuela, Pérez Cavero and Contreras2022).

The article is structured as follows. First, it contextualizes mining firms’ corporate social responsibility practices within the literatures on social conflict and the social foundations of regulation in Latin America. It does so by arguing that firms respond strategically to social mobilization against their activities, thus potentially meditating between social movement pressures and regulatory interventions. Second, we theorize the mechanism through which companies articulate their response as a process of “corporate translation,” in which managers interpret activist demands into local practices that may be viewed as an attempted settlement with activists. As some locally embedded activist groups make demands that pose existential threats to the project (i No a la mina!), we underscore that managers are likely to attain a settlement with only a fraction of mobilized societal groups. These partial settlements are often nonetheless effective by demobilizing important contributors to multisectoral activist coalitions, but also unstable by invariably leaving some groups active and able to adapt their oppositional strategies.

The empirical section uses the comparative sequential method (Falleti and Mahoney Reference Falleti, Mahoney and Thelen2015) to examine the corporate social responsibility practices of the multinational mining company Barrick Gold at the Pascua Lama/Veladero projects in Argentina and Chile (2005–2018). In both countries, we compare short causal sequences in which corporate managers respond to localized protest with practices that function to fragment multisectoral activist coalitions and forestall regulatory intervention.

Firms at the Center of the Politics of Regulation

The explosion of contentious politics associated with Latin America’s turn toward an extractivist model of development is well documented (Arce Reference Arce2014; Bebbington et al. Reference Bebbington, Abdulai and Bebbington2018; Svampa Reference Svampa2019). Resource-seeking firms are frequently the target “authority” against which protests and demands are directed, especially at the local level—and protestors often also make simultaneous claims on the state to cancel or regulate projects. Yet for most scholars of extractivism, firm responses to local mobilization are epiphenomenal to the regulation and outcome of social conflicts. In significant part, this is because researchers are more interested in activist strategies and successes (Svampa et al. Reference Svampa, Sola Álvarez, Bottaro and Antonelli2010) and choose to focus on emblematic cases of resistance in which company responses are less effective. Such research biases also contribute to a proclivity to view corporate social responsibility as a purely discursive exercise (Clark and North Reference Clark, North, Clark and Patroni2006; Leiva Reference Leiva2019) and to a normative concern with project cancellation as the only outcome of significance (Scheidel et al. Reference Scheidel, Del Bene and Liu2020; Walter and Urkidi Reference Walter and Urkidi2017; Walter and Wagner Reference Walter and Wagner2021).

This neglect of firm responses can no longer be justified, in light of both recent theorizing that shows mine-community relations to be more varied in nature and outcome than the emblematic cases would suggest (Perla Reference Perla and Drinot2014; Paredes Reference Paredes2022) and empirical evidence from larger-N studies that negotiated continuity is, in fact, the dominant tendency in the sector (Haslam and Ary Tanimoune Reference Haslam and Ary Tanimoune2016; Akchurin Reference Akchurin2020; Orihuela et al. Reference Orihuela, Pérez Cavero and Contreras2022; Jaskoski Reference Jaskoski2022). In this context, we need to consider that firm responses could be part of the explanation for the failure of social mobilization and the absence of regulatory intervention in the resource sector.

To date, Latin Americanists working on companies have not considered a longer causal chain that connects mobilization to firm practices and state regulatory responses. A few political scientists and sociologists have connected protest to firms’ CSR activities. When appropriately adapted to local realities (Dougherty and Olsen Reference Dougherty and Olsen2014) and social pressures (Perla Reference Perla2012), CSR, some scholars suggest, can reduce the likelihood or severity of conflict by shaping perceptions and responding to distributive demands from social actors (Himley Reference Himley2013; Amengual Reference Amengual2018). Localized corporate practices also have an institutional dimension by emphasizing a stakeholder logic centered on the firm (Costanza Reference Costanza2016; Betchum Reference Betchum2018; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson2018), and may undermine independent micromobilization processes (Haslam Reference Haslam2021).

In terms of regulatory action, scholars interested in the role of businesses have traditionally focused on how elite pacts, informal networks, and active lobbying by firms can contribute to a pro-investor orientation in bureaucracies with regulatory authority (Durand Reference Durand2016; Bebbington et al. Reference Bebbington, Abdulai and Bebbington2018), or result in the creation of regulatory institutions or laws that are born weak (Gustafsson and Scurrah Reference Gustafsson and Scurrah2019; Paredes and Figueroa Reference Paredes and Figueroa2021; Damonte and Schorr Reference Damonte and Schorr2021). Although some researchers suggest that the corporate provision of public goods reinforces neoliberal forms of governance (Bebbington Reference Bebbington, Raman and Lipschutz2010; Cisneros and Christel Reference Cisneros and Christel2014), no causal chain has been established linking protest to company responses and specific regulatory interventions.

Therefore, in order to conceptualize the role of companies in mediating between social mobilization and regulatory interventions, we turn to the literature on the social foundations of policy implementation in Latin America, which highlights how pressures from societal actors on political principals and bureaucracies explain variation in regulatory enforcement. This relational view of institutional effectiveness (Brinks et al. Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2019) emphasizes the collaboration between civil society and bureaucratic actors, wherein the former provides information, external monitoring, operational resources, and legitimacy to the latter that can reinforce both state capacity and the will to regulate (Hochstetler Reference Hochstetler2012; Amengual Reference Amengual2016; Falleti and Riofrancos Reference Falleti and Riofrancos2018; Abers Reference Abers2019).

Amengual and Dargent (Reference Amengual, Dargent, Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2020) make a particularly important contribution by building a bridge between this literature and the resource sector, showing how the “standoffish” states that characterize Latin America will unevenly commit resources to policy implementation, depending on the political incentives do so. At the project level, they recognize that localized support or opposition “proximate to the point of enforcement” can explain the willingness to enforce locally, even if it has little effect on the big picture of regulatory enforcement countrywide (2020, 163). However, they do not consider how large mining firms may act to weaken the influence of local societal actors mobilized for regulatory enforcement in a way that may be considered similar to the “political mediation” process identified for other actors, including parties, the media, and the court of public opinion (Amenta et al. Reference Amenta, Caren, Chiarello and Su2010, 289, 296; Silva Reference Silva2018).

Thus, the CSR practices that mining firms deploy in response to localized protest have the potential to disrupt the chain of causality between social mobilization and (proximate) regulatory enforcement identified by Amengual and Dargent, insofar as they contribute to demobilizing protestors and reducing their ability to make compelling claims on the state. This approach has implications for how we understand the absence of visible protest or regulatory intervention in much of Latin America’s vast rural “brown areas” (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2004; also Perla Reference Perla and Drinot2014) occupied by mining. Rather than assuming the absence of societal pressures on the state in these areas, we highlight the agency of companies in potentially mediating between social movements and regulatory intervention. We prefer the term regulatory intervention because we focus on the moment when the state chooses to regulate, but remain agnostic as to its effectiveness.

The Corporate Translation of Activist Demands

To understand the mechanism through which mining firms mediate between social mobilization and regulatory intervention, we need to look inside the firm to understand both how protest affects CSR practices and how CSR practices affect subsequent mobilization. Here we focus on how corporate managers interpret and respond to protest and the resulting “settlement” they aim to achieve with societal actors.

The first part of this equation has been examined by sociologists working at the intersection of social movement studies and the sociology of organizations. They show that actors internal and external to the firm shape its response to activist mobilization (King and Pearce Reference King and Pearce2010). Firms tend to be more open to demands from primary and internal stakeholders, such as investors, managers, employees, and suppliers, whom executives view as being aligned with the firm’s interests (Soule Reference Soule2009; Vasi and King Reference Vasi and King2012). External to the firm, boycotts and blockades by social actors can impose direct costs and damage the firm’s reputation and legitimacy (Vasi and King Reference Vasi and King2012, 578). Perhaps the most important external consideration for the firm is the indirect risk that social mobilization will draw in the state as an effective regulator that threatens its interests (Haufler Reference Haufler2001). In this regard, the corporate social responsibility practices of mining firms can be understood as motivated by social mobilization and the concomitant risk of both direct (disruption) and indirect (regulatory) costs.

But firms’ specific responses to protest are the result of an internal process through which managers translate activist demands into a set of corporate practices. Building on Campbell’s concept of institutional translation (Reference Campbell, Morgan, Campbell and Crouch2010, 98–99), we argue that company representatives who cannot directly concede to the demands of local actors are instead compelled to translate their social demands into CSR programs according to their own institutional principles, traditions, and practices—a process that we call corporate translation. A similar translation process has been identified in regulatory agencies, in which “institutional environments shape the meanings staff attach to key movement principles” (Harrison Reference Harrison2016, 535). This is an important point, because without acknowledging the corporate translation of activist demands, it may look as though social movements have little direct influence on corporate social responsibility practices.

Institutional repertoires in mining companies constrain managers to interpret activist demands in a way that can be operationalized through CSR practices. This means that managers can respond to some demands better than others. The literature has already noted that social mobilization against mining typically includes mixed motives within heterogeneous coalitions that encompass both distributional and socioenvironmental concerns about the defense of agricultural livelihoods (Haslam and Ary Tanimoune Reference Haslam and Ary Tanimoune2016). Protestors with “all or nothing” motivations (Arellano-Yanguas Reference Arellano-Yanguas2011), and more recently identified in the literature as environmental justice movements (Scheidel et al. Reference Scheidel, Del Bene and Liu2020) that call for a rejection of “extractivism,” simply cannot be accommodated by the company (Mena and Waeger Reference Mena and Waeger2014). However, it is also important to recognize that many mining disputes have a distributional logic that makes negotiation about mitigation, compensation, and benefits possible (Perla Reference Perla and Drinot2014; Amengual Reference Amengual2018; Betchum Reference Betchum2018; Orihuela et al. Reference Orihuela, Pérez Cavero and Contreras2022; Paredes Reference Paredes2022).

This process of corporate translation is central to understanding how companies mediate social movement pressures that could otherwise activate the state to regulate to benefit activists. The private politics literature has generally seen company compliance with activist demands as a kind of “settlement” between actors that buys social peace in exchange for higher standards of social or environmental performance by the firm (King and Pearce Reference King and Pearce2010; Abito et al. Reference Abito, Besanko and Diermeier2016; Baron Reference Baron2001). However, the bifurcated nature of social movement demands, combined with the process of corporate translation of them into CSR practices, means that a “settlement” between the firm and activists in the mining sector is likely, in practice, to be only partial in scope.

Nevertheless, a partial settlement also implies that a firm, through its CSR practices, may successfully buy social peace with some societal groups within a heterogeneous activist coalition—and effectively remove them from the streets. In this regard, CSR practices must be viewed as potentially reducing the cohesiveness of local social movement coalitions and weakening their ability to make WUNC claims to political authorities—claims of being worthy, united, numerous, and committed (Tilly Reference Tilly2008, 120). A fragmented multisectoral movement is weakened in its ability to socially construct the lens through which corporate actions are viewed by other important actors in the organizational field of the firm (Georgallis Reference Georgallis2017), and most importantly, to draw in the state as a regulator (Almeida Reference Almeida2015; King and Pearce Reference King and Pearce2010). As a result, we expect that corporate social responsibility practices, insofar as they are “successful” in reducing the cohesiveness of local social movements, contribute to weakening the ability of social movements to pressure the state for proximate (project-specific) regulatory intervention in their favor.

Our emphasis on the partial nature of firm–social movement settlements in the mining sector also means that CSR is unlikely to extinguish protest. Weaker, fragmented multiactor coalitions may continue to innovate in their oppositional strategies and cast around for opportunities to reignite the embers of protest into a full-blown conflagration, especially outside of the local scale, where company strategies are likely to be most effective. In this regard, we need to recognize that corporate responses to mobilization are embedded within a broader context of political and institutional opportunities for the societal actors excluded from any partial settlement attained through CSR practices.

Methodology

This study of how mining firms, through their CSR practices, mediate between social movement pressures and regulatory interventions at the project level is supported by the comparative study of the social conflict that emerged at two subsidiaries of a single mining project that straddled an international border. Developed by the Canadian mining company Barrick Gold, they were the Pascua Lama project in Chile and the Pascua Lama project/Veladero mine in Argentina. Looking at these cases permits a sort of natural experiment in which certain variables are broadly similar across the cases (including ownership and project characteristics, the headquarters’ corporate social responsibility policy, and activist framing strategies), thereby allowing us to focus on the temporal variability of localized social mobilization, CSR practices, and regulatory interventions.

We employ the comparative sequential method, a specification of comparative historical analysis in which a complex causal chain is broken into distinct (shorter) sequences that are then compared (Falletti and Mahoney Reference Falleti, Mahoney and Thelen2015). In this regard, the sequence is the unit of analysis, not the mining project. Since our primary interest is in how mining firms, through their CSR practices, mediate between social movement pressures and regulatory outcomes at the project level, this implies identifying “reactive sequences,” in which companies respond to mobilization by intensifying their CSR activity and succeed in undermining social movement cohesiveness (Falleti and Mahoney Reference Falleti, Mahoney and Thelen2015, 221). Where reactive sequences fail to take hold, we may imagine a “self-reproducing” sequence, in which growing mobilization is reinforced over time and eventually spurs regulatory intervention by the state—the scenario described by Amengual and Dargent (Reference Amengual, Dargent, Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2020). By focusing on sequences instead of cases, we also highlight the contingent, agent-oriented, and temporal expansiveness of mining conflicts.

Data sources used in this article include stakeholder interviews, researcher-coded data about social mobilization, and secondary documentation. The interview material presented reflects the combined efforts of two separate but thematically aligned research projects, each led by one of the article’s co-authors. They involved fieldwork in Argentina in 2011–13 and 2016–19 comprising a total of 156 interviews (167 people), and in Chile in 2011–14 comprising 22 interviews (27 people). The cases are unbalanced because one of the original projects was structured around an Argentina-Chile comparison and the other focused entirely on Argentina. In both projects, interviewees were sampled purposively, or as a result of snowballing, to reflect major stakeholder categories—namely, company representatives, government officials, and activists—at the national, provincial (Argentina only), and local levels (see table). Interview schedules from both projects considered the relationship between state, firm, and communities. Extensive secondary material was also available, especially on the Chilean side.

Additional data on social mobilization were collected and recorded by the authors for this article according the techniques of protest event (PE) analysis based on media accounts, reports from information aggregators associated with activist NGOs (such as OCMAL, the Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina, and the Environmental Justice Atlas), and secondary sources (including academic analyses, NGO reports, and agencies of the state). We used simple counts of events (the vast majority of which were local and capital-city–based), and thus the PE data provide an overview of the intensity of the social mobilization by number of events.

With regard to corporate responses to mobilization, we use the umbrella term corporate social responsibility (CSR). In mining, the purpose of CSR is to facilitate the operation of the firm by managing social risks (Yakovleva Reference Yakovleva2005; Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen2018). Modern CSR is usually viewed as integral to the business mission of the firm and reflected in various aspects of internal corporate governance (such as ethics, reporting, and decisionmaking procedures), as well as mechanisms for engagement with external stakeholders (Soule Reference Soule2009; Dashwood Reference Dashwood2012). In practice, modern CSR coexists with traditional approaches that include philanthropy and clientelism (Clark and North Reference Clark, North, Clark and Patroni2006; Himley Reference Himley2013). In this article, we are interested in the relatively standardized bundle of practices used to structure relationships with external stakeholders, which encompasses public relations campaigns, corporate mechanisms to consider community viewpoints (consultation or complaint procedures), programs to distribute benefits, and private environmental governance (Yakovleva and Vazquez-Brust Reference Yakovleva and Vazquez-Brust2012).

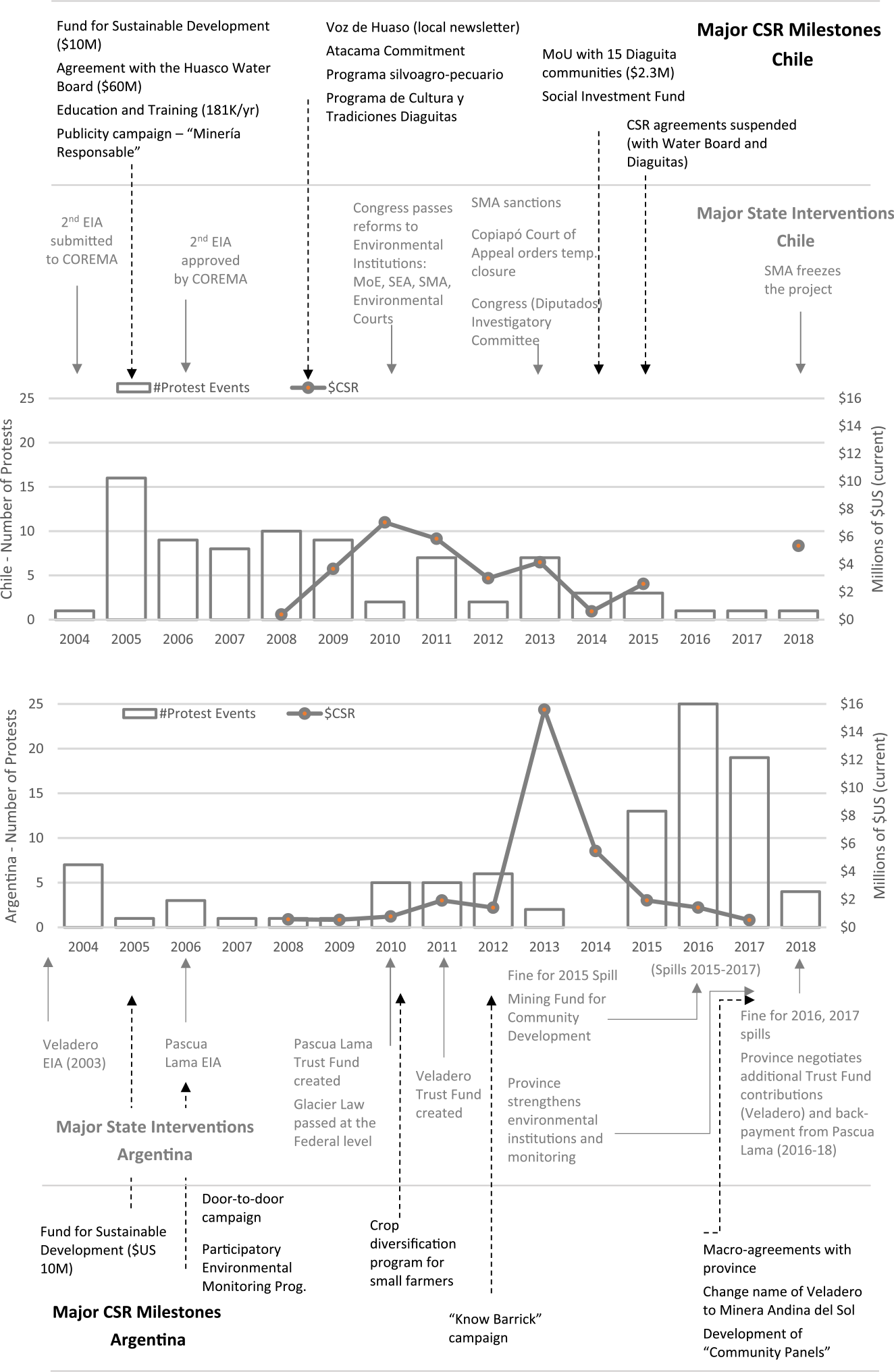

Qualitative data on CSR policy and practice were drawn from environmental filings with the regulatory authorities, corporate “sustainability” reports, media reports, secondary sources, and interviews. Where possible, we used data on CSR spending provided by the company—although such data are not consistently reported using clearly established criteria over time. A graphical overview of the key data for both projects, the number of PE events per year, major changes to corporate social responsibility practices and yearly spending, and important regulatory interventions by state agencies, is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1. Protests and CSR Spending at Pascua Lama/Veladero.

The Pascua Lama/Veladero projects achieved notoriety as emblematic social conflicts on both sides of the Andes, which has implications for the analysis. In this regard, the occurrence of self-reproducing sequences that resulted in regulatory intervention was a “most likely” outcome, and reactive sequences in which the company successfully used CSR to forestall or shape state involvement were a “least likely” or “hard case” scenario. Evidence of the latter would therefore constitute strong evidence for our central hypothesis (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005). Moreover, if such reactive sequences can be shown to be important in a context so unpropitious for the company, it implies that the local deployment of CSR practices by mining companies may help to explain the limited regulatory intervention observed in the literature more broadly.

The Pascua Lama/Veladero Projects

The Pascua Lama project is located in the Andes Mountains between 4,200 and 5,200 meters above sea level and is estimated to contain 17.8 millionounces of gold and 718 million ounces of silver, divided 75 perent to 25 percent across the border between Chile and Argentina (Barrick Sudamérica 2008, 18). In Chile, the impact area follows the rivers that spring from headwaters below the project, down the Huasco Valley in the Atacama Region, through small communities of Diaguita agriculturalists, and the administrative centers of Alto de Carmen and Vallenar. On the Argentine side, Pascua Lama is a few kilometers from the operating Veladero gold mine at 4,000 to 4,850 meters’ altitude in the Province of San Juan. The original plans for the site involved processing the ore at Veladero’s facilities in an integrated industrial complex. In Argentina, the impact area is identical for both projects, constituted by small rural communities downstream in the Jáchal Basin, and for this reason, it is impossible to separate the activism and CSR associated with each of these mining projects, so we treat them as a single unit.

The Pascua Lama and Veladero projects were owned by the Canadian major mining company Barrick Gold, which had full operational responsibility for project development and CSR for the 2003–2018 period considered in this article. Barrick had a well-developed head office CSR policy that was broadly comparable to other multinationals of similar size (Dashwood Reference Dashwood2012, 215–16). However, initial engagement with communities around the Pascua Lama and Veladero projects began in 2000, well before the company started to formalize its CSR practices and policy, when individual mines were run quite independently, almost as fiefdoms (Dashwood Reference Dashwood2012, 190, 196). In 2010, a Community Relations Management System (CRMS) was rolled out in Chile and Argentina, which provided a toolkit for CSR practitioners to assess and manage social risk (36ARSJ; 59CLSA; Dashwood Reference Dashwood2012, 190). Although CSR teams in both countries highlighted the importance of the CRMS to structuring their engagement with communities, it should be noted that some industry observers (including in peer companies) viewed Barrick’s CSR practices at Pascua Lama/ Veladero as substandard (71CLSA; 76CLSA).

The original concerns of the organized social movements that emerged in the Huasco Valley, Chile and in the departments of Iglesia and Jáchal, Argentina were principally related to the project’s threat to water and related livelihoods. The revelation (during the 2001 environmental impact assessment process) that the project would impact nearby glaciers emerged as the central activist framing device that consolidated opposition at the local level but also bridged local livelihood concerns into an emblematic national and international cause (Taillant Reference Taillant2015; 23CLSA). In both impact areas, multisectoral coalitions developed to oppose the conflict and networked across the Andes, as well as with national organizations, contributing to similar strategies that combined direct and legal actions (Rodríguez Pardo Reference Rodríguez Pardo2011). The long-term objective of both coalitions was the cancellation of the project, although it is important to note that citizens outside the core antimining organizations remained interested in distributive benefits or compensation from the firm. Since we focus on company responses to mobilization, detailed consideration of activist strategies is available from other sources (Cortez and Maillet Reference Cortez and Maillet2018; Muñoz Cuevas Reference Muñoz Cuevas2016; Urkidi Reference Urkidi2010; Urkidi and Walter Reference Urkidi and Walter2011; Rodríguez Pardo Reference Rodríguez Pardo2011; Svampa et al. Reference Svampa, Sola Álvarez, Bottaro and Antonelli2010; Taillant Reference Taillant2015).

Regulatory authority over the project was located at the national level in Chile (and with the regional services of those authorities) and at the provincial level in Argentina (though framed by federal environmental legislation). In the early years of the project, both Chile and San Juan, Argentina, exhibited a strong elite consensus in favor of mining (Svampa Reference Svampa2019; Silva Reference Silva2018). However, in both countries, reforms occurred during the Pascua Lama conflict that expanded the regulatory and legal options for activists.

In Chile, rising environmental consciousness associated with a number of contentious projects in the early 2000s, including Celco-Arauco’s Valdivia plant, Hydro Aysén, and Pascua Lama, motivated important institutional reforms under President Michelle Bachelet (2006–10) that aimed to improve regulatory enforcement (Sepúlveda and Villarroel Reference Sepúlveda and Villarroel2012; Silva Reference Silva2018; 73CLVP; 74CLSA). The Chilean environmental licensing system, under which Pascua Lama had been approved (in 2001 and 2006), was broadly viewed as oriented toward project approval, politicized in favor of project proponents, and lacking any opportunities for meaningful participation (Pizarro Reference Pizarro2006, 4, 9–12; Carruthers Reference Carruthers2001, 349–50; Barandiarán Reference Barandiarán2018). The reforms adopted in 2010, which became operational in 2012, established a Ministry of the Environment, a Superintendency of the Environment (Superintendencia del Medio Ambiente, SMA) to enforce environmental regulations and sanction violations, as well as a system of environmental courts focused on the judicial review of regulatory decisions. These reforms created new, albeit limited, institutional opportunities for activists to contest extractive projects (Haslam and Godfrid Reference Haslam and Godfrid2020; Rabi and Campos Reference Rabi and Campos2021).

In Argentina, provinces have the principal authority over the permitting and regulation of mineral resources, although the weakness of provincial regulatory authority has been widely noted (Amengual Reference Amengual2016; Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and Murillo2013). In the province of San Juan, Peronist Governor José Luis Gioja (2003–15) and his successor, Sergio Uñac (2015–), viewed mining as the driver of provincial economic development and were significantly more interested in promoting mining activity than regulating it (Godfrid Reference Godfrid2021). Although the federal Glacier Law (2010) prohibited mining from impacting glaciers or “periglacial” (permafrost) areas and was widely thought by activists to require the cancellation of the Pascua Lama project, provinces remained the regulating and sanctioning authority (Taillant Reference Taillant2015, 196).

In this context, authorities in San Juan refused to implement the legislation to alter the viability of the Pascua Lama project. Nevertheless, the federal legislation created opportunities for activists to bypass provincial institutions and reorient their activities toward the federal courts. As in other historically poor provinces of the Northwest, authorities cultivated clientelist relationships with society based on the provision of public employment (Gervasoni Reference Gervasoni2010; Svampa et al. Reference Svampa, Sola Álvarez, Bottaro and Antonelli2010, 157–60; Rodriguez Pardo Reference Rodríguez Pardo2011, 47–48). San Juan authorities were probably more interventionist than those in Chile, retaining considerable discretion to informally pressure private mining companies on local procurement, employment, and social responsibility spending (Haslam and Godfrid Reference Haslam and Godfrid2020).

On both sides of the border, the project faced considerable social, legal, and regulatory difficulties, principally as a result of social movement actions. In Chile, two parallel but occasionally intertwined processes unfolded: one centered on allegations (denuncias) of violations to Barrick’s environmental license, granted in 2006; and the second based on claims for recognition of indigenous rights by Diaguita actors. It was the first process that was ultimately salient to the closure of the project on the Chilean side. In 2013, the SMA ordered the project halted (temporarily) in order to complete various environmental mitigation measures. However, a subsequent Environmental Court ruling (2014) found that the SMA’s order was incomplete and required it to reopen the sanctioning process in a context in which additional citizen denuncias had been registered with the regulator (Muñoz Cuevas Reference Muñoz Cuevas2016, 119). On January 17, 2018, the SMA issued its revised sanction requiring the definitive closure of the project as then proposed, which the Supreme Court upheld the following year. With the closure of the project in Chile, work in Argentina was also suspended, but for reasons of feasibility. In 2022, the Argentine side of the project (Lama) continued to be considered a potential project.

Chile

The Chilean case focuses on two sequences in which Barrick responded to social pressure with targeted CSR programs aimed at achieving a settlement with mobilized actors. The first was a reactive sequence, in which an agreement with the Huasco Water Board fragmented the opposition and permitted the environmental licensing of the project. In a second sequence, the company negotiated a partial settlement with Diaguita communities, known as the memorandum of understanding (MoU), but failed to demobilize significant actors or forestall regulatory intervention.

Agreement with the Huasco Water Board, 2005–2006

In Chile, mobilization by a multisectoral and multiscalar (local to national) coalition of actors during the second environmental impact assessment for an enlarged project seemed to pose a real risk of nonapproval by the regional service of the regulatory authority, COREMA Atacama (Comisión Regional del Medio Ambiente Atacama), between 2004 and 2006. Barrick’s submission, which proposed moving 10 hectares of ice from one small glacier that obstructed the planned pit to another nearby glacier, contributed to consolidating a multisectoral opposition focused on the role of glaciers in the hydrological health of the valley (Muñoz Cuevas Reference Muñoz Cuevas2016, 50; Urkidi Reference Urkidi2010; Rodríguez Pardo Reference Rodríguez Pardo2011). Figure 1 shows a dramatic increase in protest activity associated with the second EIA (2004–6), which, in a context of rising environmental consciousness and known politicization of environmental licensing decisions (Pizarro Reference Pizarro2006; Sepúlveda and Villarroel Reference Sepúlveda and Villarroel2012; Silva Reference Silva2018), dramatically increased the risk of nonapproval by the state.

CSR managers in Barrick’s Santiago office (the regional head office responsible for projects in both Chile and Argentina) understood how social mobilization created regulatory risks for the firm.

Companies have, in quotation marks, become more vulnerable. We have to adapt to this new reality, need to use the competitive pressure from civil society groups to do better, and to get the social license. Another issue is that although politicians want investment, they also want votes, so sometimes they are willing to support civil society groups. (59CLSA)

They also recognized the challenge of translating activist demands into concrete projects and reported that what they perceived as excessive community demands could cause a breakdown of the dialogue process, either because stakeholders would not “sit down with you” or because such demands could not be accommodated within the logic and profitability of the mine (59CLSA). In this regard, the company had a limited ability to address the concerns of socioenvironmental activists through specific CSR projects (COREMA 2006, 167; 97CLSA; 101CLVA).

In response to the social mobilization associated with the 2004–6 EIA process, Barrick’s CSR proposals clearly showed how the company was ratcheting up its portfolio of activities, the specificity of commitments, the funds to be allocated, and the integration of local stakeholder participation in spending decisions (see figure 1) (CMN 2000, 9–14; COREMA 2006, 141–42). Several initiatives emerged at this time, including a Fund for Sustainable Development, education and training programs to support suppliers and future employees, and a national publicity campaign branding Barrick as “Responsible Mining” (99CLVA). However, the centerpiece of this new spending was an agreement with the Huasco Water Board signed on June 30, 2005, after the conflict had attained national emblematic status but before COREMA Atacama had authorized the project. The agreement between the company and the board created a US$60 million fund (US$3 million per year over the 20-year life of the mine) for the improvement of irrigation systems and hydrological infrastructure and committed both parties to jointly answer questions on the environmental impact of the project. As a contract between private parties, it also functioned to keep disputes between the signatories out of the courts (23CLSA).

The agreement had important consequences for the conflict. Although the Board of Directors was principally composed of the largest rightsholders, the Huasco Water Board represented all water rightsholders in the valley, and in this regard its decision to seek a separate peace with Barrick added legitimacy to the company’s position that Pascua Lama was compatible with agricultural livelihoods (Muñoz Cuevas Reference Muñoz Cuevas2016, 60). For example, a member of the board asserted that the infrastructure investments associated with the deal left the Huasco Valley with much better water management than neighboring valleys (97CLSA). Moreover, the agreement broke away an influential organization representing larger farmers from the rest of the opposition coalition, undermining its multisectoral credentials (Urkidi Reference Urkidi2010, 223; 23CLSA). In her definitive account of the conflict, Muñoz Cuevas notes that in the wake of the agreement with the Water Board and the intensification of CSR activities in the Huasco Valley, local mobilization against the project weakened—an observation that is supported by our count of protest events in this period, which declined from the highs recorded in 2005 (see figure 1).

Most important, the agreement with the Huasco Water Board seems to have allowed COREMA to approve the environmental license (Resolución de Calificación Ambiental, RCA). Evidence suggests that RCA 024/2006 was barely approved, since it included some four hundred demanding conditions, which were probably a response to political pressure rather than technical considerations (Barandiarán Reference Barandiarán2018, 146–48). Thus, in the context of a broad-based multiscalar mobilization and increasing interest from politicians in Santiago, including President Ricardo Lagos and then-candidate Michelle Bachelet, it seems likely that project approval depended on Barrick’s partial settlement with the Huasco Water Board. Other actors, who remained excluded from the partial settlement with the water board and unwilling to accept other CSR benefits offered by the company, found themselves with limited institutional opportunities to oppose the RCA after it was granted (Muñoz Cuevas Reference Muñoz Cuevas2016, 67, 125). Until Chile’s environmental reforms became operational in 2012, the partial settlement with the Huasco Water Board was sufficient to weaken the ability of activists to achieve regulation of the project in their favor.

The Memorandum of Understanding with Diaguita Communities, 2012–2014

Diaguita organizations were also involved in the multisectoral coalition against the project, principally through the Comunidad Agrícola Diaguita Los Huascoaltinos (CADHA), an agricultural community composed of small agriculturalists who identified as Diaguita (100 CLVA; 102CLAC). However, with the recognition of the Diaguita as an Indigenous people by the Chilean state in 2006, both traditional peasant organizations such as CADHA and Diaguita communities that were newly “recognized” by CONADI (Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indígena) were able to link the Pascua Lama project to the violation of human rights, including their rights to consultation, property, and traditional livelihoods (Aguilar Cavallo Reference Aguilar Cavallo2013; Urkidi and Walter Reference Urkidi and Walter2011; 18CLSA).

The strategic location of Diaguita communities in the Huasco Alto (high valley), combined with the increasing legal salience of indigenous rights claims, led Barrick to privilege this relationship within its broader set of CSR activities. Since at least 2004 it had provided support to the Diaguita Cultural Center, including developing workshops and certification for traditional handicraft activities, legal advice for recognition of status and property (accreditation by CONADI), technical and productive assistance to farmers, and educational scholarships (Barrick Sudamérica 2008, 78), contributing to the folkloristic “reethnicization” of the Diaguita (Gajardo Reference Gajardo2014). The CSR program also succeeded in producing positive impressions of the company among some community members, especially women, who found both personal valorization and economic opportunities as guardians of traditional culture and the production of handicrafts, although CADHA remained steadfast in its opposition (Gajardo Reference Gajardo2021).

In 2012–14, the project faced a series of legal and regulatory challenges as the environmental reforms passed by the Bachelet government came into effect. Sanctions determined by the new SMA would ultimately determine the fate of the project. Staff within the organization were responsive to citizen denunicas, and characterized their early regulatory actions against the company as an “achievement” that sent a message that “open negligence” and non-compliance with the RCA was unacceptable (71CLSA; 74CLSA). However, in 2013 the outcome of that regulatory process was unclear, and a parallel legal process led by 12 CONADI-recognized Diaguita communities succeeded in positioning these communities as important obstacles to the development of the project (Muñoz Cuevas Reference Muñoz Cuevas2016; Gajardo Reference Gajardo2021). In July 2013, lawyers for the recognized communities obtained a freeze on the project from the Copiapó Court of Appeal, which was later upheld by the Supreme Court (Aguilar Cavallo Reference Aguilar Cavallo2013).

In response to these pressures, Barrick leveraged its lengthy engagement with Diaguita culture to attempt a settlement through the memorandum of understanding signed by Barrick and the leadership of 15 indigenous communities in April 2014. The agreement provided for information sharing about the environmental effects of the project and mitigation measures and implied a future agreement about benefits (Gajardo Reference Gajardo2021, 98). Barrick portrayed the agreement as a “world first” and “aligning with the standards of ILO 169”—and also made a US$2.3 million fund available to support the collection and analysis of data regarding the impact of the project on the Diaguita’s “ancestral territory” (Muñoz Cuevas Reference Muñoz Cuevas2016, 142–43).

The MoU can be viewed as an explicit attempt to address the risk of court-ordered intervention in the project. Like the agreement with the Water Board, it constituted a private contract between two parties that limited both recourse to the courts and state oversight of its contents (Maher et al. Reference Maher, Monciardini and Böhm2021). Moreover, the MoU initially garnered the support of the minister of the environment, lending credence to the idea that Barrick had solved its problematic relationship with the Diaguita in a way that would permit the mining project to move forward (Muñoz Cuevas Reference Muñoz Cuevas2016).

However, the settlement was too partial to be effective and failed to translate substantive activist demands into CSR practices. The MoU was quickly denounced by other organizations claiming to represent Diaguita interests, such as CADHA. It was portrayed as a private deal with “bought” community leaders who had failed to gain consent of their communities and who had engaged in a superficial trading of benefits for signatures (Weibe Reference Wiebe2015, 10; Maher et al. Reference Maher, Monciardini and Böhm2021, 56). Most important, institutional opportunities to contest the project continued to be accessible in the postenvironmental reform context in Chile. Local activist organizations, supported by Santiago-based OLCA (Observatorio Latinoamericano de Conflictos Ambientales), challenged the initial SMA ruling in the courts as being incomplete, and committed to “activist monitoring” and reporting additional violations of the RCA to the SMA (Muñoz Cuevas Reference Muñoz Cuevas2016, 111, 201). These efforts led the SMA to reopen its sanctioning process and incorporate new denuncias—ultimately concluding with the definitive closure of the project in 2018. In this regard, the MoU failed to achieve its objectives.

Argentina

In San Juan, the focus is on three sequences in which the company responded to social mobilization with targeted CSR programs aimed at achieving a settlement with important societal actors. The first was a successful reactive sequence, in which the firm’s response to distributional and environmental concerns maintained social mobilization at a low level. The second, associated with Argentina’s Glacier Law, provides insights into the limits of corporate responses, as the government of San Juan began to collaborate with Barrick to backstop its CSR programs. Ultimately, a cohesive mass mobilization associated with a series of accidents overwhelmed the defensive potential of any corporate social responsibility strategy, drawing in the state as a regulator.

Geographically Varied Environmental and Distributional Concerns, 2002–2007

Barrick’s early engagement with communities (2002–4) identified key concerns of the population, including both distributive and environmental justice issues: employment and training, water use and quality, health and hospital infrastructure in rural towns, control of environmental pollution, and road safety (Knight Piésold Consulting 2003, table 5.6). These concerns varied geographically across the impact area and began to manifest as mobilization when construction began on Veladero.

In Iglesia, the department closest to the mine, local inhabitants were primarily interested in employment opportunities. Also, in Tudcum, vecinos (neighbors) concerned about the negative effects of mining traffic on their adobe houses organized several roadblocks of the access to the mine, resulting in “face to face” negotiations with company managers (14TDARSJ). However, in Jáchal, the neighboring department, the main concern was the socioenvironmental impacts of Veladero, particularly the possible contamination of the Jáchal River. In Jáchal between 2004 and 2006, women known as the Mothers of Jáchal organized mobilizations, meetings, and local petitions to demand environmental information and protest the presence of Barrick in San Juan.

Barrick responded effectively to demands from societal actors with targeted CSR programs, and as a result, social mobilization remained at a relatively low level during this period, in a context of heavy-handed public support for the project from the provincial government (Svampa et al. Reference Svampa, Sola Álvarez, Bottaro and Antonelli2010). It opened two CSR offices in the impact area (Iglesia and Jáchal) and hired local workers as implementers (5PDC). The employment issue was relatively easy to assimilate into Barrick´s logic, but in 2005 the lack of skills among local people remained an obstacle (33TDARSJ). Barrick developed programs to train suppliers and contractors, including programs in truck driving, gastronomy, safety, and hygiene, as well as supporting agricultural cooperatives (Barrick Argentina 2010, 30; Ministerio de Minería, San Juan Argentina 2005). Over the years, Veladero directly employed approximately 1,500 workers, of whom about 17 percent to 22 percent came from the departments of Iglesia and Jáchal (Barrick Gold 2019). Barrick was also able to respond to the protests in Tudcum by building a bypass for the exclusive use of its mining trucks.

Environmental claims were harder to address directly, and were translated by company managers into Barrick´s organizational logic. A manager at Barrick’s San Juan office emphasized that “Adaptation is key, because without it you don’t have effectiveness” (36ARSJ). Principally, this was viewed as a question of appropriately adapting head office guidelines, technical language, and practices to the local context, as a result of ongoing engagement with community organizations (36ARSJ; 98CLVA). For example, concerns over the lack of information about the environmental consequences of the mine and the quality of water were addressed by several programs: the Participatory Environmental Monitoring Program, launched in 2006, allowed Community members to participate in the collection of monitoring data; the construction of infrastructure to improve drinking water in Iglesia and Jáchal (Barrick Argentina 2010); and programs to develop drip irrigation systems and construct water reservoirs (6TDARSJ, 52TDARSJ).

These CSR programs enabled the company to achieve a settlement with some local actors; for example, small farmers (13TDARSJ; 30TDARSJ), entrepreneurs and job seekers, and households affected by traffic. For others, these programs were “propaganda” that did not resolve their environmental concerns (28TDARGSJ; 7TDARSJ). The company’s CSR practices were relatively successful in limiting social movement cohesion, as mobilization remained at a low level until 2009 (figure 1). Throughout this period, Barrick made adjustments in response to mobilization over particular issues and without any significant coordination with state institutions (42PDB).

The Glacier Laws, 2008–2010

In 2008, the federal congress passed legislation to protect glaciers and periglacial areas from mining. After President Cristina Kirchner vetoed the law, a group of intellectuals, NGOs (including Greenpeace; FARN, Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales; and Conciencia Solidaria), and socioenvironmental organizations launched a national educational campaign to raise awareness about the importance of protecting glaciers, which culminated in the passage of a second federal Glacier Law (No. 26.639). The legislation and social mobilization associated with it constituted an existential threat to the project, which was then in the construction phase. Figure 1 also shows an increase in social mobilization around 2010 related to the federal Glacier Law as activists seized on its potential to cancel the project, and by 2011, antimining protests had emerged across the country, including neighboring provinces (Wagner Reference Wagner2016). Social movements in San Juan federalized their opposition to Pascua Lama by framing their conflict with Barrick as a dispute over glaciers and by networking with other like-minded organizations nationally to demand the implementation of the federal law, in the streets and the courts (Haslam and Godfrid Reference Haslam and Godfrid2020).

In this context, Barrick also federalized its CSR strategy as it faced a national movement against the Pascua Lama project. As shown in figure 1, this period was characterized by a dramatic increase in CSR spending by the firm. First it launched a new national media campaign for Argentina. “Know Barrick” focused on promoting the company’s activities in Argentina (Barrick Argentina 2012, 3). Until then, the company’s communication strategy had focused on the province of San Juan, and especially on Iglesia and Jáchal. Second, starting in 2009, Barrick began to coordinate its CSR programs much more closely with the province of San Juan and other nonprofit foundations. For example, the Tomato Program (developed 2009–14) was a joint initiative between the Ministry of Production, Barrick Gold, and rural cooperatives (3TDARSJ).

The government of San Juan did not respond to this increased social and juridical pressure by regulating the company in favor of activists. It challenged the implementation of the Glacier Law in the courts (jointly with Barrick), and as regulating authority, refused to implement it to undermine the Pascua Lama project. Instead, it doubled down on supporting Barrick’s voluntary engagement with communities, but also pressured the company to spend more in collaboration with the province to assure the legitimacy of mining within the impact area (Haslam Reference Haslam2016; 28ARSJ).

In 2010 and in 2011 the provincial government pressured Barrick to establish trust funds for Pascua Lama and Veladero. For the Pascua Lama fund, the company agreed to allocate US$70 million during the period 2009–29, of which 88 percent was to be used for infrastructure projects in water, health, education, and agriculture in the impact area (Boletín Oficial 2018, 192.392). For Veladero, the company agreed to pay US$5.7 million over a period of three years. Although San Juan acted opportunistically to extract more rent from Barrick, the province continued to view the distributive benefits associated with CSR spending as sufficient to ensure that social mobilization did not disrupt operations and resisted societal pressure to regulate Barrick’s environmental performance more aggressively.

Environmental Accidents, 2015–2017

In September 2015, a cyanide-bearing solution spilled into a nearby waterway at the Veladero mine (Barrick Gold 2020). The first spill was followed by two other accidents in September 2016 and March 2017 (Barrick Gold 2018), which were widely covered by the national media (Infobae, Clarín, La Nación, Página 12).

As figure 1 makes evident, the spills contributed to a dramatic increase in social mobilization and political opposition. Direct collective actions against the company were organized at the departmental (Jáchal), as well as at the provincial and federal levels (Buenos Aires). These actions included roadblocks and demonstrations carried out by a network of neighborhood assemblies, environmental actors, and NGOs. Protesters occupied the main plaza in Jáchal between October 2015 and 2019. Inhabitants of San Juan also presented two criminal judicial complaints against Barrick Gold and state officials (in both provincial and federal courts), alleging lack of compliance with environmental legislation and failure to protect the glaciers in the area as required by Law No. 26,639 (Mira Reference Mira2016). The cases before the judiciary were also promoted by prominent national politicians and the Environmental Lawyers’ Association of Argentina.

In the aftermath of the accidents, Barrick sought to change its national branding by abandoning its slogan “Responsible Mining,” in response to a long-running spoof campaign organized by NGOs: “Barrick Gold. Irresponsible Mining” (Godfrid Reference Godfrid and Merlinsky2020). The head office in Canada intervened, and senior management was replaced several times between 2015 and 2018, including the community relations manager in 2016. In 2017, a 50 percent stake in Veladero was sold to Shandong Gold Group, and the merged company was renamed Minera Andina del Sol. Between 2017 and the end of 2019, the company replaced the name Veladero with Minera Andina del Sol and refreshed its branding across social networks (Facebook and Instagram). Only in 2020, after protests had diminished, did the company return to the Veladero brand when communicating CSR initiatives on social media and in public events.

In Iglesia and Jáchal in 2015 and 2016, most of Barrick’s CSR programs were scaled down or placed on standby, but they were reactivated sometime in 2017. For example, the Participatory Environmental Monitoring Program carried out since 2006 was interrupted during that period (33TDARSJ). In Iglesia, the local CSR office agency continued to function normally, but in Jáchal, because of the local demonstrations, the agency worked without a logo until 2019.

In this sequence, Barrick was unable to offer a CSR response that could blunt the sudden consolidation of a multisectoral social movement or forestall state regulation. The province of San Juan, facing unprecedented “self-reproducing” mobilization in Jáchal that threatened the legitimacy of its extractivist development strategy, was compelled to sanction the company and deepen its regulatory oversight of the project.

The mine was forced to suspend its operations for a few months in 2016 and again in 2017 (until it had completed infrastructure investments to prevent new accidents). Then a series of major fines were imposed: $US10 million for the 2015 accident and $US5.6 million for the 2016 and 2017 events (Barrick Gold 2018, 167–69). The government created an environmental prosecutor’s office to be located in mining communities to receive and investigate denuncias from the population. The Ministry of Mining signed an agreement with the University of San Juan to develop an environmental monitoring system. Furthermore, the number of environmental inspections of the mine was increased, and a camera monitoring program was installed to provide real-time monitoring (Diario de Cuyo 2016; Servicio Informativo 2019; Haslam and Godfrid Reference Haslam and Godfrid2020). The province continued to see distributive benefits as contributing to social peace. Fines were paid into a Community Development Fund, and the Ministry of Mining also worked to develop and coordinate a series of macro-agreements with the company to increase its CSR contribution to local communities and enhance confidence in environmental management.

Conclusions

This article has argued that the CSR practices of firms should be considered an important intervening variable between social mobilization and the regulatory responses of states in Latin America. At the mining project level, social mobilization can generate important changes in corporate practices toward nearby communities, and these practices can undermine the cohesion of social movements advocating for regulatory intervention or reform, thus limiting their ability to make compelling claims on the state.

All five sequences examined in Chile and Argentina reveal a consistent relationship between mobilization and corporate response. Faced with direct social mobilization or a judicial process resulting from mobilization, the company responded with additional CSR programming that aimed to produce a settlement with local actors, limit recourse to the courts, and forestall the risk of regulatory intervention. Although this study focused on the local (project) level, in both countries, local CSR practices were complimented by national branding campaigns when the social conflicts threatened to involve political principals at the national and federal levels. Settlements with mobilized social groups were constrained by a process of corporate translation of activist grievances into initiatives that made sense within a corporate logic. Managers were unable to translate movement demands that constituted existential threats to the mine to the satisfaction of these actors—meaning that settlements with mobilized actors were consistently partial—some social actors demobilized, but others remained active in their opposition.

The sequences examined also varied in terms of how successful the company was in demobilizing key groups in a multisectoral coalition and weakening their ability to call on the state for regulation in their favor. The comparison of within-country sequences suggests that when activists have few institutional opportunities to advance claims outside of the local context, where the company is particularly influential, then corporate social responsibility responses are more likely to be effective in contributing to demobilization. Such was the case in Chile, where there were few opportunities to contest COREMA’s decision to approve the Pascua Lama project in 2006, and regulatory sanctions were weak—before the reform of environmental institutions. In Argentina, in the early years of the projects, CSR practices were also effective in keeping conflict at a low level, as the company was able to reach partial settlements with some groups that prevented an emerging social movement from cohering in the impact area of the project.

However, in both countries, CSR had a more limited effect in containing events that transcended the local scale, especially when institutional opportunities to contest the project opened for those activists excluded from the partial settlements with the company. Such was the case for the Diaguita organizations, such as CADHA, and other oppositional groups excluded from the MoU, who were able to channel their denuncias directly to the SMA, as well as to keep pressure on the SMA to sanction to the letter of the law through the courts, after the 2012 reforms. Similarly, the federal Glacier Law in Argentina opened opportunities for activists to pursue their claims through federal courts, although the government of San Juan continued to use its regulatory authority to obstruct the implementation of the law, thus restricting the utility of these opportunities.

In San Juan, the government’s promining orientation led it to support and collaborate with Barrick’s CSR initiatives, which also limited activists’ ability to pressure the state for regulatory intervention. It was only after the series of accidents in San Juan (2015–17), which resulted in a very intense and cohesive local mobilization, that the provincial government was forced to respond with enhanced regulatory oversight of the project. In that context, intensive mobilization rendered the CSR activities of the firm redundant.

Our analysis shows that company interpretations of and responses to protest are an important mediating process that conditions civil society efforts to activate state institutions in their favor during mining conflicts. However, it is also important to recognize the limits of this analysis. We view our theory about how CSR affects regulatory intervention as being most relevant at the project level, where local pressures can change the incentives for standoffish states to act (Amengual and Dargent Reference Amengual, Dargent, Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2020). CSR practices are more likely to achieve these goals when the partial settlements they represent demobilize important and influential actors and when those excluded from the settlement have few institutional opportunities to advance their cause outside of the local context. Furthermore, the analysis does not discount the possibility of corporate lobbying for regulatory benefits or nonenforcement, but does identify an additional and observable process by which corporate practices can affect regulatory intervention.

Conflict of interest

Paul Haslam and Julieta Godfrid declare none.