Severe mental illnesses, including psychotic and bipolar disorders, are major contributors to distress, disability and early mortality worldwide. 1 The prediction and prevention of these disorders is a public health priority. Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana and Bolton2 Contemporary approaches to psychosis prediction have largely focused on either symptom-based approaches to detecting risk (i.e. clinical high-risk or ultra-high-risk strategies) Reference Fusar-Poli, Salazar de Pablo, Correll, Meyer-Lindenberg, Millan and Borgwardt3,Reference Yung and Nelson4 or identifying at-risk individuals based on genetic or familial risk (i.e. familial high-risk strategies). Reference Shah, Tandon and Keshavan5 Recent research, however, has shown that these approaches identify only a minority of future psychosis cases, with both clinical and familial high-risk strategies estimated to capture <7% of cases each. Reference Talukder, Kougianou, Healy, Lång, Kieseppä and Jalbrzikowski6 Higher-capacity strategies for psychosis risk detection are therefore needed.

One alternative to focusing on symptoms or family history as indicators of risk is to concentrate on systems where risk factors for psychosis are naturally concentrated (i.e. a systems-based approach). Reference Kelleher7 One such system is specialist child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS). CAMHS provide specialist out- and in-patient services that assess, diagnose and treat mental health problems in young people aged up to 18 years. Reference Signorini, Singh, Boricevic-Marsanic, Dieleman, Dodig-Ćurković and Franic8 Schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders are uncommon diagnoses in CAMHS – only 8% of schizophrenia and 13% of bipolar disorder cases are diagnosed before age 18 years. Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo and Salazar de Pablo9 However, many of the risk factors for psychosis, such as developmental difficulties, early psychopathology, substance use, adversity, deprivation and cognitive and education difficulties, are present in those attending CAMHS. Reference Dickson, Laurens, Cullen and Hodgins10–Reference Nielsen, Toftdahl, Nordentoft and Hjorthøj12 Therefore, although psychosis may be uncommon in CAMHS, it may be the case that risk for later psychosis is elevated in this cohort, providing opportunities for prediction and, ultimately, prevention.

Current study

In a recent study using longitudinal register data in Finland, approximately 50% of all psychotic disorders diagnosed in the population by age 28 years were in individuals who had, at some point in childhood or adolescence, attended CAMHS. Reference Lång, Ramsay, Yates, Veijola, Gyllenberg and Clarke13 This demonstrates important opportunities for prediction and prevention within CAMHS. Given the unique features of Scandinavian health and social care services, Reference Signorini, Singh, Boricevic-Marsanic, Dieleman, Dodig-Ćurković and Franic8 however, it is not clear to what extent this would be true in other parts of the world, including in the UK. We therefore wished to assess what proportion of psychotic and bipolar disorder diagnoses emerged in individuals who had, at some point up to 18 years of age, attended CAMHS in Wales, UK. In addition, we wished to assess whether particular population risk factors for psychosis also identified an increased risk for psychosis among these CAMHS patients. In order to do this, we used linked longitudinal administrative data for a population cohort in Wales followed up to a maximum age of 32 years. Our primary aim was to calculate the proportion of all psychotic and bipolar disorder diagnoses in the population by age 32 that occurred in individuals who had attended CAMHS. We also calculated the cumulative risk of psychotic and bipolar disorder diagnoses among individuals who attend CAMHS, and examined associations between sociodemographic and clinical risk markers and psychotic and bipolar disorder outcomes in adolescent patients.

Method

Study design

This study is reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. Reference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke14 Participants were identified from linked data hosted in the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) databank. Reference Ford, Jones, Verplancke, Lyons, John and Brown15–Reference Rodgers, Lyons, Dsilva, Jones, Brooks and Ford19 SAIL contains anonymised, routinely collected data from a variety of health, social care and administrative data-sets in Wales. Data-sets are linked using an established and validated split-file approach, which has a sensitivity of >99.8%. Reference Lyons, Jones, John, Brooks, Verplancke and Ford17 SAIL’s Information Governance Review Panel (IGRP) granted approval to conducting this research (IGRP no. 1635).

Information on exposures and outcomes was identified from a range of data-sets in the SAIL Databank: (a) the Welsh Demographic Service Data-set (WDSD), containing anonymised demographic and general practitioner practice registration history for all individuals in Wales that use NHS services; (b) the Patient Episode Data-set for Wales (PEDW), containing records of all in-patient hospital admissions to Welsh hospitals (available from 1995 to study end); (c) the Out-patient Database for Wales (OPDW), containing records of all hospital out-patient appointments in Wales (available from 2004 to study end); and (d) the Welsh Longitudinal General Practice Data-set (WLGP), containing electronic health records from ∼80% of general practitioner practices in Wales, covering ∼83% of the population. The start date for availability of WLGP records varies for each general practitioner practice, depending on when coded electronic records were implemented. Reference Thayer, Rees, Kennedy, Collins, Harris and Halcox20 In addition, information on risk markers was identified in the National Community Child Health Database (NCCHD), the Education Wales (EDUW) data-set, the Emergency Department Data-set (EDDS) and the Looked After Children Wales (LACW) data-set.

Cohort

Participants were included if they were born between 1991 and 1998 (inclusive) and were registered with a Welsh general practice before the age of 13 years.

Exposure

Child and adolescent mental health service contacts in Wales were identified from in-patient (PEDW), out-patient (OPDW) and general practitioner (WLGP) records. Wales is one of four nations in the UK. Child and adolescent mental health services are broadly similar across the four nations, in that these are publicly funded, specialist mental health services for youth aged up to 18 years and are free at the point of access. We created indicators for any CAMHS contact, and for in-patient CAMHS admission. In-patient CAMHS contact was defined as any admission beginning before age 18 years where the primary diagnosis was of a mental disorder (any ICD-10 F code), or where the specialty code for the admission was for a relevant psychiatry specialty (see Supplementary Table 1). Out-patient CAMHS contacts were defined as appointments that occurred before the individual was 18 years old and that had a relevant psychiatry specialty code (as above). CAMHS contacts in general practitioner records were identified using Read codes denoting specialist mental health service contact for events that occurred before the individual was 18 years old (Supplementary Table 1), adapted from Joseph et al Reference Joseph, Jack, Morriss, Knaggs, Butler and Hollis21 and reviewed by a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist on the study team (I. Kelleher). We derived indicators for having both a CAMHS contact at any point (<18 years) and a CAMHS contact in adolescence (13–18 years [inclusive]). Due to the different start dates of the three health data-sets, complete data on childhood (<13 years) CAMHS contacts were not available for all individuals, but complete data were available for adolescent (13–18 years) CAMHS contacts.

Outcome

Diagnosis of psychotic and bipolar disorder at any time during the study period was identified from clinical codes in in-patient (PEDW) and general practitioner (WLGP) records (see Supplementary Table 2 for codes). Psychotic disorder diagnoses recorded in administrative data are generally accurate, with a systematic review finding that such diagnoses had a relatively high positive predictive value (>80%) when externally validated. Reference Davis, Sudlow and Hotopf22 An overall indicator of any psychotic and/or bipolar disorder was calculated, as well as indicators for the subcategories of: (a) non-affective psychotic disorders (ICD 10 codes F20–9 and Read codes adapted from Abel et al Reference Abel, Hope, Swift, Parisi, Ashcroft and Kosidou23 ); (b) bipolar affective disorders (ICD 10 codes F30–1 and Read codes adapted from Carr et al Reference Carr, Ashcroft, Kontopantelis, While, Awenat and Cooper24 and Kuan et al Reference Kuan, Denaxas, Gonzalez-Izquierdo, Direk, Bhatti and Husain25 ); and (c) depressive disorders with psychotic features (ICD 10 codes F32.3 and F33.3 and Read codes adapted from John et al Reference John, McGregor, Jones, Lee, Walters and Owen26 ). Subcategories were not mutually exclusive.

Risk markers

We examined the following risk markers: (a) sex, identified from WDSD and categorised as male or female; (b) ethnicity, identified as the most common ethnicity code reported across PEDW, NCCH, EDUW and EDDS data-sets; due to low numbers of individuals in many ethnic groups, an indicator was derived for belonging to a minoritised ethnic group (defined as belonging to an Asian, Black, mixed or other ethnic group versus belonging to a White ethnic group); (c) socioeconomic deprivation in childhood, measured using the 2014 version of the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) 27 identified from the individual’s earliest available record in the WDSD, with an indicator calculated for belonging to the most deprived quintile of the WIMD (versus the other four quintiles); (d) urbanicity in childhood, indexed using the 2011 rural–urban classification 28 of each individual’s earliest available area code record in the WDSD. An indicator was calculated for living in an urban (versus rural) area; (e) winter birth, defined as month of birth (as reported in WDSD) that occurred in December, January or February; (f) low birth weight, classified as <2500 g; (g) out-of-home care experience, identified from the presence of any record in the LACW data-set; (h) in-patient CAMHS admission, excluding those that occurred prior to or during a diagnosis of psychotic or bipolar disorder; and (i) childhood (<13 years) CAMHS attendance, in addition to adolescent attendance.

Statistical analyses

We calculated the total proportion of psychotic and bipolar disorder cases by the study end-point (age 25–32 years) where the individual had, at some point in childhood or adolescence, attended CAMHS. We also calculated cumulative risk and hazard ratio with 95% CI for psychotic and bipolar disorder outcomes (diagnosed at any age before the study end-point) among individuals who had attended CAMHS. Hazard ratios were calculated using a Cox proportional hazards model, with date of entry set as either the date of the individual’s birth (for any CAMHS contact) or 13th birthday (for CAMHS contacts in adolescence), and date of exit set as the earliest of the date of the outcome, death, last available general practitioner registration (indicating emigration) or administrative censoring at the end of the study period (November 2023). Cumulative risk of psychosis or bipolar disorder onset (by age 32 years) was described using the Kaplan–Meier failure function (1 – survival). Reference Kaplan and Meier29 Descriptive statistics (median and interquartile range) of the time between psychosis and bipolar disorder outcomes and CAMHS attendance in adolescence were calculated for outcome diagnoses that occurred more than 3 months following the individual’s first CAMHS contact, or after their initial in-patient admission, in keeping with Lång et al. Reference Lång, Ramsay, Yates, Veijola, Gyllenberg and Clarke13

We used univariable and multivariable logistic regression to estimate associations between sociodemographic and clinical risk markers and psychotic and bipolar disorder outcomes in individuals who had a record of CAMHS attendance in adolescence. In these analyses, individuals were excluded if they had died or were no longer registered with a Welsh general practitioner at the end of the study period (indicating that they were not living in Wales throughout the entire duration of the study period). We first estimated unadjusted associations between each risk marker and psychotic and bipolar disorder diagnosis. Risk markers that had significant associations in univariable models were then included in a multivariable model, again examining the relationship with psychotic and bipolar disorder outcomes. Analyses resulted in odds ratios with 95% CIs as measures of effect size, with odds ratios of 1.00–1.49 interpreted as small, 1.50–2.49 as medium and 2.50 or more as large. Reference Rosenthal30 We also calculated the absolute risk of psychotic/bipolar disorder for subgroups of adolescent patients, stratified by the presence of each risk marker, using the number of individuals with both the risk marker and psychotic/bipolar disorder diagnosis as the numerator, and total number of individuals with the risk marker as the denominator.

SQL Db2 was used to interrogate data in the SAIL Databank, and analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.1.

Results

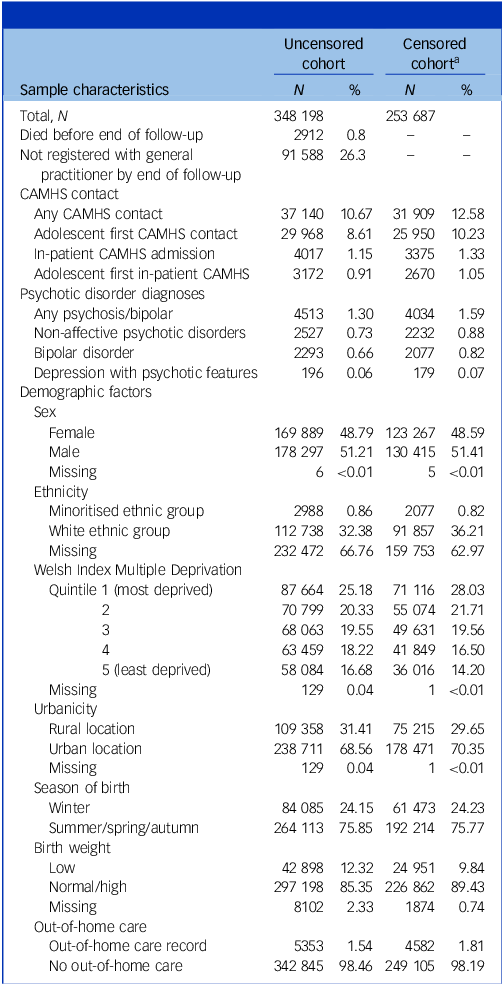

The overall sample included 348 198 individuals, of whom 2912 (0.8%) died during the study period and a further 91 588 (26.3%) were no longer registered with a Welsh general practitioner at the end of follow-up (i.e. had probably emigrated; see Supplementary Fig. 1 for flow diagram). Among the overall sample, 37 140 (10.7%) individuals had a record of CAMHS attendance and 4513 (1.30%) had a diagnosis of a psychotic or bipolar disorder by the end of follow-up. Sample characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1 Sample characteristics

CAMHS, child and adolescent mental health services.

a . Excluding individuals who died/were no longer registered with general practitioner before end of follow-up.

Our main finding was that, of all individuals with a psychotic or bipolar disorder among the total population, 44.78% had attended CAMHS at some point up to age 18 years (Table 2). In total, 41.41% of psychotic or bipolar disorder cases had attended CAMHS in their adolescence and 10.64% had had an in-patient CAMHS admission (Table 2). For schizophrenia specifically, 49.28% of cases had attended CAMHS prior to age 18. The proportion of bipolar disorder cases where the individual had attended CAMHS was 43.70% (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3). When analyses were stratified by sex, a greater proportion of female psychotic and bipolar disorder cases had attended CAMHS in adolescence compared with males – 45.93 and 36.59%, respectively (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 2 Child and adolescent mental health service contact and diagnoses of psychotic and bipolar disorders by age 25–32 years (N = 348 198)

CAMHS, child and adolescent mental health services. Predictive capacity is the proportion of all disorder cases in the population that occurred among CAMHS patients.

The cumulative risk of psychotic or bipolar disorder among CAMHS attenders was 6.99%, compared with 1.30% among the total population (hazard ratio = 6.28, 95% CI = 5.92, 6.65; Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Among adolescent patients the cumulative risk was 7.92% (hazard ratio = 6.92, 95% CI = 6.52, 7.34). CAMHS attenders had elevated risk of all three types of disorder compared with the total population. When analyses were stratified by sex, female adolescent patients had a higher cumulative risk of bipolar disorders and depression with psychotic features when compared with males, but males had a higher cumulative risk of non-affective psychotic disorders compared with females (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

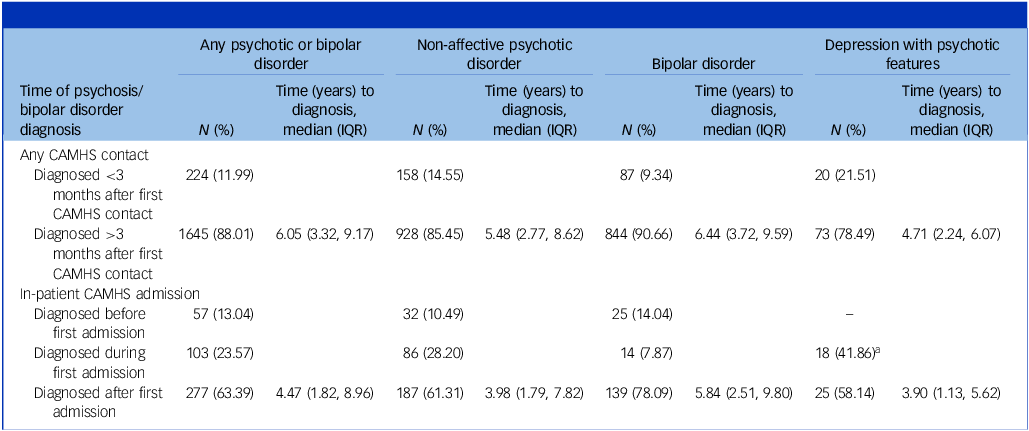

Time between CAMHS contact and psychosis outcomes: for the majority (88.01%) of cases, a psychotic or bipolar disorder was not the index diagnosis on attending CAMHS, defined as a diagnosis occurring within 3 months following initial CAMHS contact (Table 3). For those individuals, the median time to diagnosis was 6.05 years. Across the various disorder types the median length of time from CAMHS contact to diagnosis ranged from 4.71 years (depression with psychotic features) to 6.44 years (bipolar disorder). For those with in-patient admissions, the majority (63.39%) of cases were also diagnosed following their first admission; the median length of time to being diagnosed with a psychotic or bipolar disorder in this group was 4.47 years.

Table 3 Time to psychosis/bipolar disorder diagnosis following adolescent CAMHS attendance

CAMHS, child and adolescent mental health services; IQR, interquartile range.

a . Diagnosed during OR before first admission.

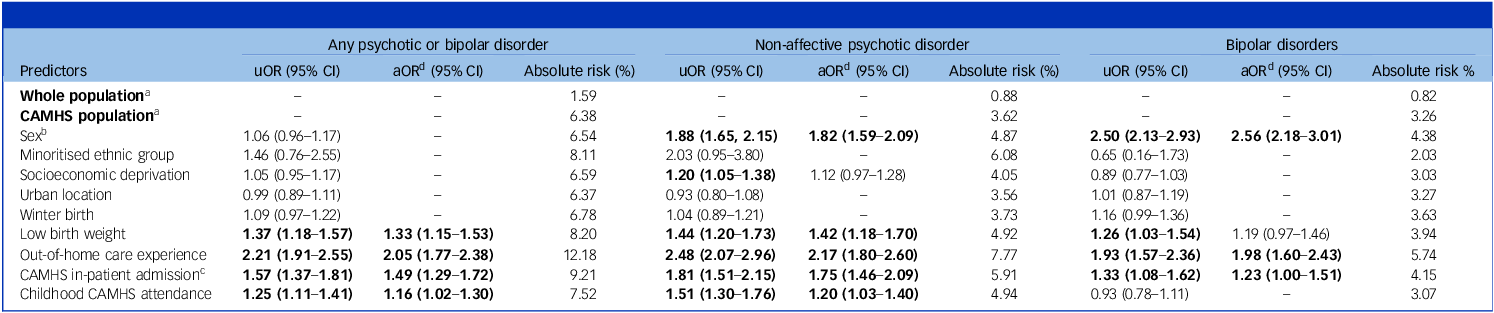

Associations between risk markers and psychosis outcomes: among the 25 950 individuals who attended CAMHS in adolescence (and had not died or were no longer registered with a Welsh general practitioner before the end of the study period), several risk markers were associated with a psychotic or bipolar disorder outcome in univariate analyses (Table 4). Low birth weight, out-of-home care, having an in-patient CAMHS admission (for a reason other than psychosis) and having had a CAMHS visit in childhood (in addition to having had a CAMHS visit in adolescence) were all associated with increased odds of any type or psychotic or bipolar disorder. Sex was not a predictor of any type of psychotic or bipolar disorder. However, this was a result of the fact that male sex predicted later non-affective psychosis and female sex predicted later bipolar disorder; thus, looking at a combined non-affective psychosis, bipolar outcome results in sex effects ostensibly disappearing when there are, in fact, sex-specific differences (Table 4). Male sex, socioeconomic deprivation, low birth weight, out-of-home care, in-patient CAMHS admission and childhood CAMHS attendance (in addition to adolescent CAMHS attendance) were all associated with an increased risk of non-affective psychosis. Bipolar disorders were predicted by female sex, low birth weight, out-of-home care and in-patient CAMHS admission. Effect sizes for associations were all small to medium.

Table 4 Associations between demographic factors and psychosis outcomes among individuals with CAMHS contact in adolescence (N = 25 950)

uOR, unadjusted odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio. Bold font indicates statistically significant associations (i.e. 95% CI does not include 1).

a . Absolute risk calculated in censored cohort (i.e. excluding those that died/were no longer registered with general practitioner prior to study end).

b . Female sex for any psychotic or bipolar disorder/bipolar disorder outcomes; male sex for non-affective psychotic disorder outcomes.

c . Excluding admissions where a psychotic or bipolar disorder diagnosis was made during or before the admission.

d . Adjusted for other predictors significantly associated with the outcome of interest.

In multivariable analyses, the majority of risk markers retained significant associations with psychosis outcomes when adjusted for the other risk markers, with the exception of the associations of socioeconomic deprivation with non-affective psychosis and low birth weight with bipolar disorder (Table 4).

Discussion

In this population cohort of almost 350,000 individuals living in Wales, we assessed the proportion of all psychotic and bipolar disorders diagnosed in the population up to age 32 years that occurred in individuals who had, at some stage in childhood or adolescence, attended CAMHS. We found that 47% of all non-affective psychosis (including 49% of schizophrenia), 44% of bipolar disorder and 48% of psychotic depression cases in the population diagnosed by age 32 years) occurred in individuals who had attended CAMHS. Our results are in keeping with recent findings in a Finnish population sample, where 50% of psychotic and bipolar disorder cases emerged in individuals who had attended CAMHS. Reference Lång, Ramsay, Yates, Veijola, Gyllenberg and Clarke13 Our results demonstrate that this finding is not unique to Finnish healthcare systems and that UK CAMHS offers similar important opportunities for psychosis prediction and prevention.

The proportion of psychosis cases that emerged from CAMHS services was substantially higher than that shown to emerge from other high-risk approaches. Research on the clinical high-risk approach, for example, has found that <7% of psychosis cases are identified by clinical high-risk services, Reference Talukder, Kougianou, Healy, Lång, Kieseppä and Jalbrzikowski6 and this approach appears to be even more limited in identifying at-risk children and adolescents. Reference Gandhi and Cullen31,Reference Lång, Yates, Leacy, Clarke, McNicholas and Cannon32 Similarly, recent research suggests that only a small proportion (7%) of psychotic disorders is captured using the familial high-risk approach. Reference Healy, Lång, O’Hare, Veijola, O’Connor and Lahti-Pulkkinen33 A new focus on CAMHS, therefore, would stand to substantially increase capacity for psychosis prediction and prevention.

The baseline absolute risk of a psychotic or bipolar disorder in patients who had attended CAMHS was 7% by the end of follow-up. Several sociodemographic and clinical risk markers predicted an increased risk beyond the baseline risk associated with CAMHS attendance, with small to medium effect sizes. This included (a) sex (male sex for non-affective psychosis; female sex for bipolar disorder), (b) low birthweight, (c) out-of-home care experience, (d) in-patient CAMHS admission (for reasons other than psychosis) and (e) having a childhood CAMHS visit (in addition to adolescence). Absolute risk differences associated with these factors were relatively small, and additional research will be necessary to identify higher-risk subgroups within this population, which may include genomic, proteomic, cognitive, neuroimaging, electrophysiological and other measures.

The baseline level of psychosis risk associated with CAMHS attendance was lower in Wales (7%) than in our previous Finnish research (13%). Reference Lång, Ramsay, Yates, Veijola, Gyllenberg and Clarke13 This probably reflects a difference in the prevalence of psychotic and bipolar disorders in Welsh and Finnish healthcare registers (1.3 v. 3.2%). This could represent real differences in the population prevalence of psychotic disorders between countries, but probably also reflects differences in how psychosis is recognised, diagnosed and recorded by services, because methodological differences have previously been found to be a major contributor to variance in prevalence estimates across settings. Reference Moreno-Küstner, Martín and Pastor34 While Wales has publicly funded mental health services, challenges with staffing levels contribute to longer waiting times and uneven access, particularly in rural areas, 35 which may impact case finding and recording. In any case, these findings, based only on register-captured diagnoses, probably represent a conservative estimate of the true risk of psychosis in this population.

Most (88%) psychotic and bipolar disorder cases were diagnosed more than 3 months following an index CAMHS visit – the median time to diagnosis from the point of first CAMHS contact was, in fact, 6 years. This is also in keeping with findings from Finland, Reference Lång, Ramsay, Yates, Veijola, Gyllenberg and Clarke13 where the median time to psychosis diagnosis was 6.5 years. This highlights that there is a wide window of opportunity in which to intervene prior to psychosis diagnosis, and suggests that CAMHS contact typically occurs far upstream of psychotic disorder, which is auspicious in terms of opportunities for intervention in the context of a disorder that typically has a slow, insidious onset.

There are a number of important clinical and research implications arising from our findings. Our results highlight that, although psychosis is an uncommon diagnosis in CAMHS, it is a common outcome for patients who have attended CAMHS when followed into adulthood. Clinicians in adult mental health services should be aware of the elevated risk of psychosis and bipolar disorder in patients who had previously attended CAMHS. Second, while the long median latency between CAMHS attendance and ultimate psychosis diagnosis in our cohort suggests that, in most cases, CAMHS patients were far upstream of psychosis, it is also likely that a minority of patients were, in fact, psychotic during their CAMHS presentation, and this was not identified. This highlights the importance of expertise in the recognition and management of psychosis within CAMHS. Third, the high proportion of psychosis and bipolar diagnoses that arose in former CAMHS patients highlights the need for an intense research focus on risk for severe, chronic and enduring mental illnesses within child and adolescent mental health services. Notably, our results demonstrate that a far higher proportion of psychosis cases emerge from child and adolescent mental health services than do from clinical high-risk services. Reference Talukder, Kougianou, Healy, Lång, Kieseppä and Jalbrzikowski6 Fourth, precision medicine research that allows us to identify individuals or subgroups at particularly elevated risk will also be valuable, including through examination of the impact of combinations of different risk factors that tend to act cumulatively rather than independently. Reference O’Hare, Watkeys, Whitten, Dean, Laurens and Harris36 Last, future research will need to examine ways to reduce risk for psychosis in patients who attend CAMHS. This clinical population holds promise for intervention, however, because (a) increased risk is identifiable based on routine administrative healthcare data (i.e. data that capture CAMHS attendance) and (b) risk is identified, by definition, while still in childhood, which may be a more opportune time to impact on neurobiological and psychosocial development, rather than the early adult stage typically associated with CHR diagnoses.

The strengths of this study include the use of a large population cohort covering approximately 83% of the Welsh population and the use of prospective administrative data that are not subject to interview or recall bias. That this study replicates and extends previous findings in Finland is also important given the ‘replication crisis’ in research. 37 Limitations include that complete information on CAMHS attendances before age 13 years was not available, meaning that we were likely to miss early childhood CAMHS contacts. However, young people attending CAMHS in adolescence appear to be at higher risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders than those attending in childhood, Reference Lång, Ramsay, Yates, Veijola, Gyllenberg and Clarke13 so the period of highest risk was likely to have been fully captured. Second, the exclusion of individuals without continuing general practitioner registration through the study period may have introduced selection bias because this may disproportionally exclude specific populations, including unhoused people and those who had emigrated out of Wales. Severe mental illness is associated with increased likelihood of residential mobility and migration, Reference Jongsma, Turner, Kirkbride and Jones38 and of experiencing homelessness. Reference Barry, Anderson, Tran, Bahji, Dimitropoulos and Ghosh39 Thus, excluding these populations may have contributed to underestimating the prevalence of psychotic and bipolar disorders and, for the same reasons, our estimates are likely to be conservative. Third, given that self-harm and suicidal behaviours often precede a psychosis diagnosis, Reference Bolhuis, Ghirardi, Kuja-Halkola, Lång, Cederlöf and Metsala40,Reference Bolhuis, Lång, Gyllenberg, Kääriälä, Veijola and Gissler41 it is also possible that, in some cases of suicide, there was an emerging (but hitherto undiagnosed) psychosis. This would also have led to an underestimation of psychosis risk in the CAMHS population in the current data. Fourth, it was not possible to investigate the relationship between specific adolescent mental disorder diagnoses and risk of psychosis and bipolar disorder, because information on CAMHS diagnoses is not, in most cases, captured in the register. This will be an important area for future research. Last, data on ethnicity were not available for a large proportion of the participants, as is common in electronic health records collected during earlier time periods in the UK. Reference Mathur, Bhaskaran, Chaturvedi, Leon, vanStaa and Grundy42 Future research should investigate the relationship between ethnicity, CAMHS attendance and psychotic/bipolar disorder outcomes in data-sets where this information is more complete.

In conclusion, we found that child and adolescent mental health services in Wales, UK, capture risk for a substantial proportion of the total population incidences of psychotic and bipolar disorders. This highlights important opportunities for psychosis and bipolar disorder prediction and prevention within existing child and adolescent mental health services, at a scale far exceeding current high-risk approaches.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material can be found at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.48

Data availability

Access to SAIL data is available on application to the SAIL Databank via their usage governance process (www.saildatabank.com).

Acknowledgements

This study makes use of anonymised data held in the SAIL Databank. We thank all the data providers who make anonymised data available for research. The findings and views reported are those of the authors and should not be attributed to SAIL Databank staff.

Author contributions

K.O. performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. U.L. and C.H. interpreted data and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. I. Kougianou and A.T. participated in data analysis and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. R.M., S.M.L. and A.J. critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. I. Kelleher conceived the study, supervised the design and coordination of the study, supervised analysis and acquired funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by awards to I. Kelleher from the Health Research Board (no. ECSA-2020-005), the Academy of Medical Sciences (no. APR8\1005) and the UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

Declaration of interest

S.M.L. is a member of the BJPsych editorial board. He did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper. Declaration of interest for all other authors: none.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.