I Introduction

At a May 2019 rally in Dresden for the far-right Patriotic Europeans against the Islamification of the Occident (PEGIDA), young men handed out party literature for the nativist party Alternative for Germany (AfD). An organizer wore a blue cornflower, the famous symbol of the Nazis, and the crowd loudly sang songs extolling German virtue. Despite such an open display of anti-Semitic ritual, nobody blinked an eye at the multiple large Israeli flags waved enthusiastically by several attendees. When asked about the apparent contradiction between PEGIDA and support for Israel, an elementary school teacher and PEGIDA supporter expressed confusion: “Of course we support Israel.” When pressed, he responded, “Why do you want to know? Do you have Jewish roots?” (PEGIDA Rally 2019, Dresden).Footnote 1

In this article, I document that nativist parties and politicians increasingly use positive religious references to Jews and Israel, rather than derogatory racial terms. Yet rather than reflect a change in attitude toward national Jewish minorities, however, these references still serve to further a white supremacist agenda, a strategy totally at odds with the historic place of the Jew in white supremacist ideology. In fact, positive references to Judaism in white supremacist discourse would have been almost unthinkable one hundred years ago. White supremacist ideology in both Europe and North America is founded on the alleged deviousness of the Jewish race and its manipulation of governments and markets on national and global scales. The original concept of the Master Race was based on the premise that members were not Jews (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2017). Hatred of Jews and anti-Semitism is so integral to the intellectual foundation of white supremacy that it is used to justify other forms of racism, such as anti-Black racism in the United States. Further, anti-Semitism is key to justifying the white supremacist original narrative of victimhood and oppression. What explains this pivot? More specifically, what explains the de-racialization of Jews in white supremacist discourse? Further, what are the political implications?

Counterintuitively, I argue that the rhetorical pivot in white supremacist discourse is a harbinger of a new electoral strategy by nativist parties and evidence of the growth of identitarianism rather than an ideological de-escalation in anti-Semitism. By changing the discourse from race to religion when it comes to Jews and Israel, nativist parties that employ white supremacist rhetoric are credibly distancing themselves from the most unpopular aspects of their history just as white supremacist discourse continues to grow in the public sphere. Second, the support for Zionism in white supremacist discourse reveals the increasing influence of identitarianism on white supremacy. In this article, I argue that promoting a public perception of pro-Jewish and pro-Israel attitudes is an intentional, electoral strategy for far-right parties. This platform allows them to appeal to a more diverse constituency that would be turned off by Nazi associations and lack of support for Israel. Second, the emphasis on positive references to Israel is evidence of the growth of identitarianism, which advocates racial and ethnic segregation along identity markers, rather than annihilation. This study demonstrates that despite the deep association between anti-Semitism and white supremacy, the discourse increasingly espoused by nativist parties – parties with identitarian conservative ethno-nationalist platforms – now contains positive references to Jews and Israel, referring to Jews in religious rather than racial terms.

Nativism as a political phenomenon is hardly something new. However, the unanticipated success of twenty-first-century nativist parties, often classified as right-wing populist, has been accompanied by an ideology that has evolved since its heyday in the mid-twentieth century (Hanebrink Reference Hanebrink2018). In the twenty-first century, there has been a shift to nativism that relies on cultural, civilizational, and religious differences, rather than on nationalities and race (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017; Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2005). Additionally, nativism has embraced identitarianism, an ideology that promotes the segregation of peoples as a solution to inter-ethnic and racial conflict. Identitarianism allows white supremacists a way to sidestep allegations of racism as they position themselves as defenders of all peoples, just not defenders of multi-culturalism. Evolution of the white supremacist rhetorical use of the Jew and Israel reflects new developments and the need to tailor communications to a more mainstream electoral base. More specifically, de-racializing Israel and the Jew allows nativist parties to overcome two major challenges to expanding their electoral bases: (1) negative associations with Nazism, (2) lack of credibility with devout Christians, especially Evangelicals, who support Israel, while still allowing them to signal a commitment to ethnic purity.

This article is organized as follows: I first explore the shift in twenty-first-century nativism from a nineteenth and twentieth century preoccupation with racial identities to a focus on civilizational, cultural, and religious identities. I next trace the relationship between white supremacism and religious identities with a focus on Judaism. I demonstrate an overall shift in how Israel and the Jew are portrayed in some of the seminal white supremacist texts of the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. In the context of increasingly religious white supremacist discourse, pro- Jewish rhetoric can achieve strategic recruitment goals while mitigating negative perceptions. Positive references to Israel can appeal to Evangelical theology but also identitarian ideology both through the idea of support for a separate homeland for the Jews and support for an ethno-nationalist state with anti-Muslim policies. To demonstrate this, I use two cases studies: Germany and the United States. In Germany, pro- Jewish white supremacist rhetoric is deployed by nativist politicians to distance themselves from the disastrous Nazi past. Moreover, nativist politicians avoid allegations of a contemporary parallel between the treatment of Muslims and the historic persecution of Jews. In the United States, white supremacist support for Israel overcomes a critical hurdle for retaining and enlarging a necessary Evangelical base for the Republican party. These cases illustrate the political strategy behind shifting tropes in white supremacist rhetoric. I conclude with a discussion of the political implications of this rhetorical pivot.

II Nativist Parties, White Supremacy, Race, and Religion

Nativist parties are socially conservative, nationalistic, identitarian populist parties that promote a return to a golden past premised on a mythical nationalism. More specifically, nativist parties view society the way Mudde (Reference Mudde2004) characterizes populist parties’ perspective as “ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’” and claims to represent “the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (543). Further, they embody what Betz (Reference Betz2001) calls “exclusionary populism”: a “cultural nativism,” which advocates “advancing the notion of ‘rights’ – of ‘ethnic people,’ to a ‘culture’… that address deep-seated and understandable fears about the erosion of identity and tradition by the globalizing (but only partially homogenizing) forces of modernity” (394). Finally, nativist parties are identitarian; the parties firmly believe that their countries are on the brink of disappearing and the threat is a religious one. Nativist parties buy into the concept that, as scholar of identitarianims Zúquete (Reference Zúquete2018) describes it, “Europe is on the verge of being conquered by Islam, a young, rooted, and spiritually strong civilization that is superior to an aging and frail Europe whose treacherous elites are behaving in a manner that is the greatest expression of a civilization in free fall” (2). Unlike Nazism and other forms of fascism, which advocated for the annihilation of minorities, identitarianism argues that racial, ethnic, and cultural conflict is due to the presence of groups in places they do not belong; identitarians argue that they are not racists – they are the champions of all minorities; however, minorities would be happiest and best served by returning from whence they came. In essence, nativist parties see themselves as the last political bastions against a threat to the cultural identity of the people they claim to represent. Although many scholars refer to nativist parties such as the German Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and the French Rassemblement National (formerly le Front National) as do right-wing populist parties Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019); Taggart (Reference Taggart, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017); Mudde (Reference Mudde2004), this downplays the central role played by a constantly referenced threat to the national identity: what de Cleen (Reference de Cleen, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017) terms “exclusionary nationalism” (350). Additionally, many of these parties, especially those in Europe, have socially redistributive platforms; thus, placement along a traditional left-right continuum is problematic (Noury and Roland Reference Noury and Roland2020, 425). Scholar of the radical-right David Art (Reference Art2020) takes calls the category of populist parties “deeply misleading”:

Nativism – not populism – is the defining feature of both radical right parties in Western Europe and of radical right politicians like Donald Trump in the United States… Calling these disparate phenomena “populist” obscures their core features and mistakenly attaches normatively redeeming qualities to nativists and authoritarians. (1)

As Art explains, these are not “new” parties but parties that reflect the need to keep up with the times. While a populist communication strategy is present in nearly all these parties, it is an exclusionary, ethno-nationalist citizenship that is the essence of their agendas. In other words, nativism, not populism, is the essential attribute of these parties. Therefore, I refer to these parties as “nativist” due to the primacy of a nationalist agenda that focuses on protecting a “native” population, real or fictional, from threat.

In the twenty-first century, nativist parties have reframed how they present themselves to voters. While in the past, “the old (fascist) far right had one common denominator despite all the differences between nations and nationalisms: antisemitism,” this legacy has become a political liability (Wodak Reference Wodak and Rydgren2018, 62). More specifically,

Radical right groups began to attempt to rid themselves of the antisemitism that defined the far-right for much of the 20th century, building on the Nouvelle Droite’s new concept of nationhood, based on the cultural rather than the pseudo-biological. This allowed parties to appeal to a new audience, who did not consider themselves to be racists or extremists but sympathised with many of the radical right’s softer rhetoric on immigration and national identity. (Rose Reference Rose2020, 16)

In other words, nativist parties cast themselves in civilizational, cultural, and religious terms rather than the racial ones associated with an undesirable political past (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Similarly, the role of the nation-state has receded in importance, as “European” and “Western” ways of life, rather than national, are perceived as threatened. Rhetorically, Christianity, in the form of Christian Identitarianism, along with Western and European cultures increasingly replace race and nationality as integral to nativist agendas.Footnote 2 The “tribe” or “people” who nativist parties purport to represent has shifted from being “broadly defined by bonds of nationality and citizenship” to being “demarcated more narrowly by signifiers of social identity that provide symbolic attachments of belonging and loyalty for the in-group and barriers for the out-groups, signified by, for example, race, religion, ethnicity, location, generation, party, gender, or sex” (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019, 7). In other words, religious identity has become a useful shorthand for ethno-nationalist agendas. I argue that this new rhetorical framework offers nativist parties with white supremacist agendas the opportunity to appeal to mainstream electorates.

The nativist political parties and politicians that have risen to power in the twenty-first century, such as Viktor Orbán and Fidesz, or the Polish Law and Justice Party, espouse populist agendas based on defending a pure, homogenous people against an outside “other.” Nativist parties capitalize on the extent to which nationalities can be defined not only by who the “people” but by who the “people” are not by drawing sharp distinctions between the national “in-group” and the foreign “out-group.” Some nativist parties are radical right or right-wing parties that have been around for decades and undergone an ethno-nationalist shift, such as the Austrian FPÖ (Arwine and Mayer Reference Arwine and Mayer2008), the American Republican Party (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Parker Reference Parker and Barreto2014), and the Hungarian Fidesz (Krekó and Enyedi Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018; Zoltán and Bozóki Reference Zoltán and Bozóki2016). Other parties are new, such as the German AfD (Arzheimer and Berning Reference Arzheimer and Berning2019) and the Czech ANO (Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018).

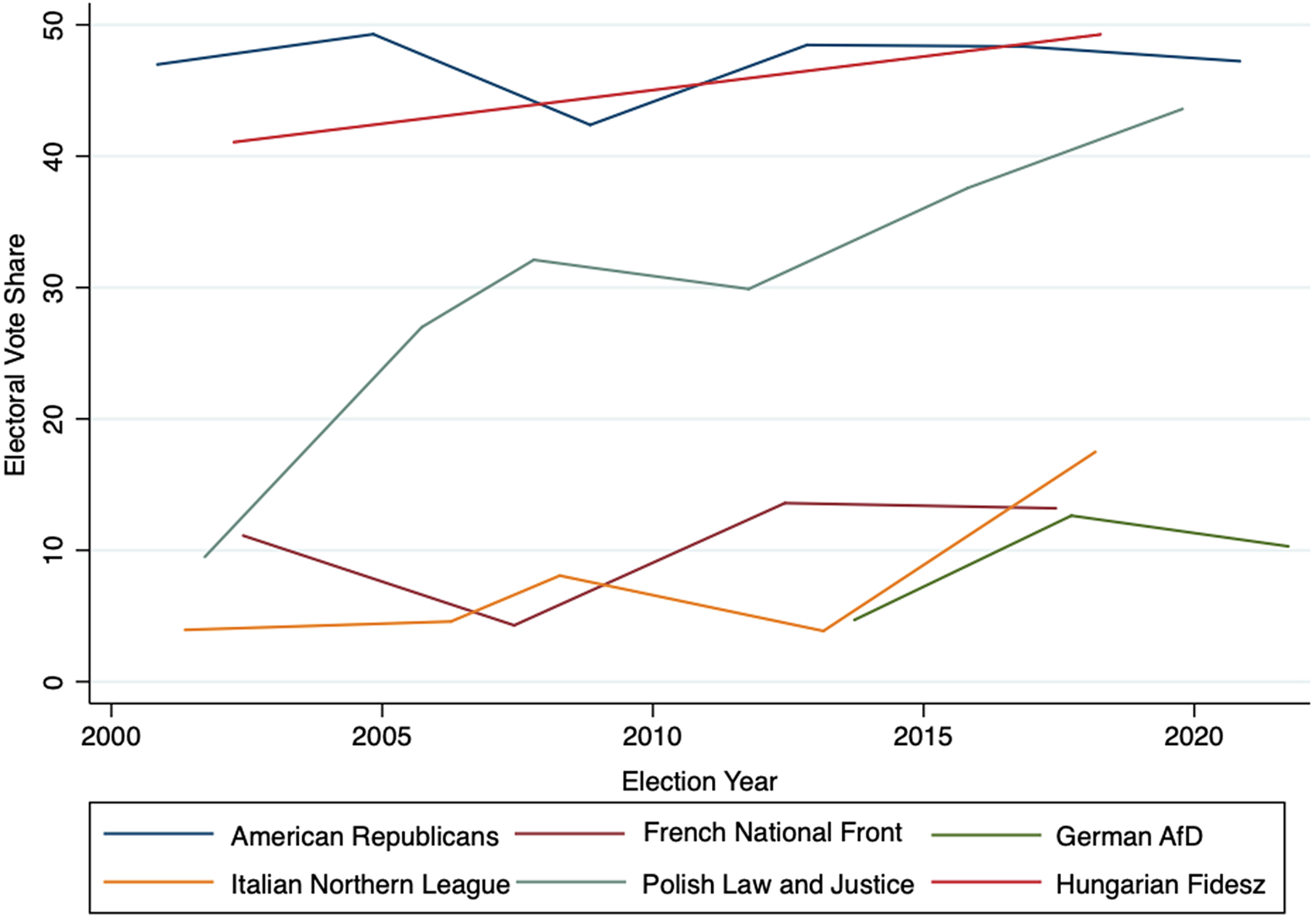

As figure 1 demonstrates, far-right nativist parties in Hungary, Italy, France, Germany, and Poland have become more successful since 2000. While the American Republic Party has hovered around the 50% mark since 2000, its rightward shift has been well-documented and should be interpreted in that context.

Figure 1. Select Nativist Party Vote Shares (2000–2020)

These parties were selected as prototypical examples of nativist parties. Extensive literature has addressed each party’s twenty-first-century success and right-wing, nativist agendas. For the Hungarian Fidesz, see Zoltán and Bozóki (Reference Zoltán and Bozóki2016); for the French National Front, see Cremer (Reference Cremer2021); for the American Republican Party, see Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) and Rowland (Reference Rowland2021); for the Polish Law and Justice Party, see Sadurski (Reference Sadurski2019); for the Italian Northern League, see Spektorowski (Reference Spektorowski2003), Morini (Reference Morini2018), and Zuquéte Reference Zúquete2007); for the German AfD, see Arzheimer and Berning (Reference Arzheimer and Berning2019).

Nativist parties present themselves as the protectors of a “threatened” nation, composed of corrupt elites and a threatening foreign element (Taguieff Reference Taguieff1995; Mudde Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017). Religion, as Marzouki, McDonnell, and Roy (Reference Marzouki, McDonnell and Roy2016) explain, plays a pivotal role in reinforcing in-groups and out-groups:

The populist use of religion is much more about ‘belonging’ than ‘belief’ and revolves around two main notions: ‘restoration’ and ‘battle’. What has to be restored is usually described as the importance afforded within society to a particular native religious identity or set of traditions and symbols rather than a theological doctrine with rules and precepts. This restoration, however, requires battling two groups of ‘enemies of the people’: the elites who disregard the importance of the people’s religious heritage, and the ‘others’ who seek to impose their religious values and laws upon the native population. (2)

Similarly, Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2017) documents a shift from delineating the “other” in national terms to civilizational ones, arguing that this has given rise to “an identitarian ‘Christianism’” (1193). White supremacy is a critical component of nativism in both Europe and North America because it provides ideological justification for the social dominance of the “native” people as well. Together, nativism and Christian Identitarianism create a more socially acceptable ethno-nationalist narrative.

White supremacy is an umbrella term for a variety of belief systems and groups based on a common understanding of a morally and eugenically white social dominance. It is based on a few basic tenets, including the need for a whites-only society and the danger of white genocide – or the Great Replacement, which is the looming extinction of the white race because of non-white reproduction rates and interracial births, allegedly orchestrated by the Jews. Journalist Talia Lavin describes the difference between general racism and white supremacists as a question of scale and of intellectual justification:

The chief distinction between members of the white supremacist movement and the explicit and implicit anti-black racists of mainstream American politics is a gleeful reveling in the terms of the racial contrast, and a desire to render injustice starker and more violent, explicit, and total. White supremacists are consumed by a desire to perpetrate violence on nonwhites, to “cleanse” the country of them, to destroy their communities through state and extrajudicial violence. But what underpins this fixation – the intellectual foundation of the white supremacist movement – is a stalwart belief in the omnipresence of the cunning, world-controlling, whiteness-diluting Jew. (Lavin Reference Lavin2020, 24–25)

In other words, the intensity of white supremacism is much greater and their goals more absolute in comparison with institutionalized racism. Further, the intellectual justifications are based on the original white supremacist literature and discourse, which first defined whiteness in terms of a negation of Jewishness.

I define white supremacist discourse as any written or spoken rhetoric that references this ideology – be it employed by movements and groups such as the American Ku Klux Klan or the Italian Casa Pound, nativist political parties such as the Hungarian Fidesz and the British National Party, or by individuals with white supremacist agendas such as the American Steve Bannon and the German Götz Kubitschek. Less obviously, white supremacist discourse is also found in places that are not explicitly racial in nature, such as from members of center-right parties or even clergy. Famously, it was a minister in the center right German CDU/CSU, Hörst Seehofer, who originated the famous refrain in an interview with der Welt “Islam does not belong to Germany” (“Der Islam gehört nicht zu Deutschland.” Der Welt. March 15, 2018). As white supremacy can be both the explicit agenda as well as a component of a party, movement, or politician, tracking its rise and evolution is especially challenging.

Although many intellectual strains contributed to the rise of contemporary white supremacist ideology, there is general consensus that much is owed to the late nineteenth-century Germanic Völkisch Movement, which framed German identity in ethno-nationalist terms and ascribed an almost mythical element to a “golden past” (Cohn Reference Cohn1998). The Völkisch Movement, which historian Norman Cohn (Reference Cohn1998) labels a “pseudo-religion,” acquired these characteristics as a reaction to the invasion of Germany and Austria by Napoleon in 1806. The invasion produced a “German nationalism [that] was from the start partly backward-looking, partly inspired by a repudiation of modernity and a nostalgia for a past which was imagined as in every way unlike the modern world” (169–170). In an era of empires, such as the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, which were composed of myriad nationalities, ethnicities, and religions, grounding sovereign legitimacy in a homogenous ethnicity was revolutionary from both a liberal and conservative perspective. On one hand, this reasoning led naturally to the sort of ethnic self-determination that redrew the European map in the aftermath of the First World War. On the other hand, it was used to justify the ethno-nationalist hierarchy responsible for European fascism and its genocides during World War II. The significance of conflating ethnicity with nationality cannot be overemphasized.

From the beginning, the relationship between white supremacy and religion was fraught. Christianity had originally been a colonizing tool of the invading Romans loathed by the Germanic tribes. Because of this, Germanic and Norse paganism become heavily romanticized in white supremacist discourse – in some cases leading to conflict (Lavin Reference Lavin2020). The Nazis famously persecuted and murdered hundreds of Catholic and Protestant leaders in concentration camps while retaining those elements of the religions that bolstered Nazi lore. Nothing perhaps exemplifies this as much as the Nazi rebuilding of the Church of St. Servatius for the celebration of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry I, of whom Hitler was rumored to be the reincarnate:

In support of his position that the thoroughly Christian Henry I was a proto- Nazi, Himmler cited a tenth century historian who tells us that Henry, at his coronation, did not seek priestly anointing. For Himmler, this was proof that Henry thought that the Christian church should not meddle in politics. But this blatantly misreads the medieval source, which is explicit that Henry refused anointment not on political grounds, but because he did not believe himself worthy of the honor; he was, in other words, acting on the Judeo-Christian virtue of humility. (Albin et al. Reference Albin, Erler, O’Donnell, Paul and Rowe2019, 109)

Another ideological contributor to white supremacist ideology, especially in North America, was the British Zionist movement. British Zionism, a precursor to Christian Identitarianism, argued that Aryans were the true Israelites, and Jews were con artists (Davis Reference Davis2010). The British Zionist narrative allowed for Israel to maintain its symbolic importance in Christianity while maintaining that Jews were an inferior, devious race. From its inception, white supremacists cherry-picked which aspects of Christianity bolstered their agenda and suppressed or coopted which aspects threatened it.

In contrast to the convoluted historic relationship between white supremacy and Christianity, the relationship between white supremacy and Jews has been straightforward. As scholar of religious terrorism Mark Juergensmeyer (Reference Juergensmeyer2017) points out,

Put simply, one cannot have a war without an enemy. This means that some enemies have to be manufactured… The demonization of an opponent is easy enough when people feel oppressed or have suffered injuries at the hands of a dominant, unforgiving, and savage power. But when this is not the case, the reasons for demonization are more tenuous and the attempts to make satanic beings out of relatively innocent foes more creative. (213)

When it came to demonizing Jews, white supremacists have been nothing if not creative. From building upon medieval myths of well-poisoning to widespread rumors of kidnapped Christian children, which sparked anti-Jewish riots, white supremacists used Jews as a foil for any social discontent. Jews were a visible, transnational minority – which meant that they could be villainized across national borders without rhetorical gymnastics. Further, there was a long and deep history of European anti-Semitism, pitting European Christians against a nefarious Jewish “other.” For the most part, because Jews lacked the political recourse and material resources for defense, they were an easy target with few consequences. In many ways, white supremacism gained an additional Christian layer to their identity by virtue of not being Jewish. At the root of this was the white supremacist idea of Jews as a separate race.

Bunzl (Reference Bunzl2005) explains that anti-Semitism was a nineteenth-century invention that grew out of a desire to “police the ethnically pure nation-state,” more specifically,

the idea of “race” gave Jews an immutable biological destiny. All of this was connected to the project of nationalism, with the champions of anti-Semitism seeing themselves, first and foremost, as guardians of the ethnically pure nation-state. Given their racial difference, Jews could never belong to this national community, no matter their strivings for cultural assimilation. Jews, in other words, could never become German (or French, or English, etc.). (502)

Anti-Semitism was integral to defining who the “people” were not –racially, but also politically, as Jews were associated with Bolshevist, Communist, and Socialist threats that presented an “international Jewish plot to rob their nations of sovereignty” (Hanebrink Reference Hanebrink2018, 3). More specifically, for over a century,

nationalist extremists and far-right movements on both sides of the Atlantic have made the idea of Judeo-Bolshevism – the belief that Communism was a Jewish plot – a prominent element of their worldview. They have interpreted different episodes in the history of Communism in the twentieth century as proof of a transhistorical global conspiracy by Jews to destroy Western civilization. (Hanebrink Reference Hanebrink2018, 2)

In other words, white supremacist rhetoric was able to employ the Jewish trope as a multifaceted threat, which appealed to a variety of right-wing interests.

The power and efficacy of white supremacist movements and parties has fluctuated over the late nineteenth, twentieth, and early twenty-first centuries. Across Europe and North America, white supremacist agendas peaked in the early to mid-twentieth century with movements and parties, such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazis, before dipping in popularity following the end of World War II. The start of the twenty-first century saw a rise in new iterations of white supremacist movement building, such as the American Aryan Nations, the British National Party, and the Italian Casa Pound. The early success of white supremacist movements in Europe and North America operated in social contexts with few constraints. As explicit racism went unchecked, racial justification of the social status quo was unlikely to ruffle feathers. White supremacy’s “second wave,” however, must contend with the advent of an evolved social desirability, particularly following Nazism and the Holocaust. It operates, therefore, largely underground, in the dark, and through dog-whistle politics (Myers Reference Myers2021; Albertson Reference Albertson2015). In some ways, this rhetoric is more dangerous, because the true agenda and capabilities are largely hidden while adherents’ preferences remain obscured. In this new social context, Christian identity plays a positive and more powerful role while still affecting the white supremacist original agenda.

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, Christianity in Europe and North America has increasingly become positively associated with white supremacy discourse. Often studied as Christian nationalism or Christian Identitarianism, Christian identity in Europe has become conflated in these movements with white racial supremacy on an unprecedented scale – not only within the discourse of white supremacist movements such as the American Base or the German Identitäre but also in the political discourse of far-right parties and their white supremacist elements (Bednarz Reference Bednarz2018; Stewart Reference Stewart2020; Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020). French philosopher André-Pierre Taguieff (Reference Taguieff1993) characterizes the use of religious rhetoric by right-wing populist parties as “neo-racism,” claiming that in “presenting itself as an ‘authentic’ antiracism…. this ‘cultural’ racism moves from the idea of zoological races (physical anthropology) to that of ethnicity and ‘culture’” (101). In other words, religious rhetoric and identities can provide a socially acceptable shield for hate. More specifically, Taguieff explains, “the difference between ‘us’ and ‘them’ is made absolute and is the basis for the prescription: exclusion/expulsion. ‘We’ are the descendants and inheritors of the Crusaders – the last legitimate sons of the Indo- European cavaliers” (124). Quite simply, religious rhetoric and identities can provide a socially acceptable shield for hate.

III Anti-Semitism or Philo-Semitism among Nativist Parties?

Anti-Semitism on the political far-right has not only not disappeared but is experiencing a renaissance. Waxman, Schraub, and Hosein (Reference Waxman, Schraub and Hosein2022) document how

antisemitism has returned as a major political and social issue across the Western world. With hate crimes against Jews, including deadly violence, rising, and antisemitic extremist groups thriving, barely a week goes by when antisemitism is not in the news headlines in the United States and Europe. (1803)

In fact, despite President Trump’s widely publicized support for Israel, “there were more physical antisemitic attacks in the United States in 2019 than ever since the tracking in the United States began”(Subotic Reference Subotic2021, 10). Yet now more than ever, political anti-Semitism on the right presents a political hurdle to attracting mainstream votes. In Europe, for example, Kahmann (Reference Kahmann2017) notes, “the open avowal of antisemitism is restricted by in the Member States of the European Union” where there is “an agreement among the democratic elites in politics and the media that the use of antisemitism as an element of political debate is taboo” (396). Subotic (Reference Subotic2021) similarly claims that “even today’s antisemites know that calling someone a Nazi is the ultimate discreditation,” so counterintuitively, “they are constructing a framework where their antisemitism is being shielded by the easiest mark of all – the universal hatred of Nazis” (9). In other words, even when nativist parties have anti-Semitic agendas, they are not politically expedient. In fact, Kahmann (Reference Kahmann2017) documents that “since the early 2000s, the kind of anti-antisemitism espoused by European right-wing parties has usually been complemented by an ostentatious display of solidarity with Israel” (401). Kahmann concludes that nativist parties “openly expressing their solidarity with Israel, as well as criticizing antisemitism, are united in their attempt to distance themselves from the Nazi past and the present neo-Nazi scene” (398). In short, pro-Jewish and pro-Israel rhetoric are powerful tools against allegations of racism and Nazism.

Many scholars identify the use of pro-Jewish and pro-Israel rhetoric by nativist parties with white supremacist agendas as a deliberate strategy to do more than simply distance themselves from undesirable political associations. Kahmann (Reference Kahmann2017) demonstrates “that the pro-Israel and anti-antisemitic turn serves primarily as a pretext for fending off Muslim immigrants, which is claimed as a contribution to the security of the Jewish population,” and support for Israel in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict “serves as a convenient screen on which to project the popular right-wing narrative of a battle between the Judaeo-Christian Occident and the Muslim world” (396). Subotic (Reference Subotic2021) highlights how support for Israel is also support for an ethno-nationally exclusive anti-Muslim state: “By redefining Zionism as an inherently anti-Muslim ideology, which sees a Europeanised idealisation of Israel defend itself from its Muslim neighbours, the European radical right has been able to claim support for Zionism and Israel” (9). Additionally, pro-Israel rhetoric is especially attractive to Evangelical Christians who are increasingly vocal in nativist politics, especially in the United States (Waxman Reference Waxman2010). In the United States, this is the result of a political realignment concerning Israel where, since the 1950s, Republicans have increased their support for Israel while Democrats have decreased their support (Oldmixon, Rosenson, and Wald Reference Oldmixon, Rosenson and Wald2005). Of interest is Cohen’s (Reference Cohen2018) finding that the realignment on Israel is not accompanied by a partisan realignment on attitudes toward Jews; Republicans still exhibit greater negativity than Democrats despite their increasing support for Israel. More specifically, in a 2021 report for the International Center for the Study of Radicalisation, Hannah Rose documents that a

shift from antisemitism to philosemitism has originated from a fundamental re-imagining of Jewishness, where Jews and Judaism are understood through far-right framings in order to legitimise existing ideologies. For example, by seeing Jews as European, pro-Israel and anti-Muslim, the far-right allows itself to align philosemitism to its own interests… In this way, deliberately positive sentiments of Jews based on stereotypes are rooted in the same processes as antisemitism, whereby the two phenomena are two sides of the same coin. (Rose Reference Rose2020, i)

In other words, Rose claims, nativist philo-Semitism is, at heart, anti-Semitic in its flattening of Jewish identity and its use as a shield against allegations of racism and Nazisim. This furthers a mainstream electoral goal by “by using Jewish people as a shield against accusations of racism…. this buffer has permitted the election of many such parties to legislative bodies and the implementation of far-right policies under the guise of liberalism” (Rose Reference Rose2020, ii). Subotic (Reference Subotic2021) similarly points out that the embrace of Israel and Jews by the far-right “does not welcome Jews for being Jews but for providing a barrier to Muslims” and is predicated on “the antisemitic concept of ‘powerful Jews,’ whose support is courted for a particular political goal (e.g., fight against Islam)” (11). Wodak (Reference Wodak2020) finds nativist pro-Jewish and pro-Israel rhetoric problematic in as “presupposing that Israel is a homogenous nation can be interpreted as a nativist and antisemitic imaginary, fallaciously generalizing negative opinions onto an entire community” (138).

For contemporary nativist parties with white supremacist agendas, anti-Semitism and overt racism serve as less effective recruitment strategies as explicit anti-Semitism renders white supremacist movements vulnerable to public criticism. Instead, demarcating in-groups and out-groups according to religious identities is more efficient and useful. By reframing anti-Semitism in civilizational and religious terms, white supremacist agendas gain political ground and can actually further a white supremacist agenda in four ways. First, pro-Jewish and pro-Israel rhetoric can distance nativist parties from associations with racist and Nazi pasts. Second, support of Israel and, especially, former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, can signal support for institutionalized ethno-nationalism in general, and anti-Muslim policies specifically.Footnote 3 Additionally, support of Israel is also support for a separate homeland for Jews, which is an identitarian solution to anti-Semitism. Finally, pro-Israel rhetoric can appeal to conservative Evangelical voters on religious grounds. In essence, it would be a mistake to interpret a rise in nativist pro-Jewish and pro-Israel rhetoric as a sign of decreasing anti-Semitism.

IV White Supremacist Literature and the Trope of the Jew

The Jew as threatening “other” is perhaps the longest-running consistent element of white supremacist ideology, certainly older and stronger than an affinity with Christianity. White supremacist discourse, which is enormously self-referential and builds upon itself over time, reflects this. While white supremacist discourse abounds with diversity; however, a few seminal works demonstrate the evolving discursive frame of the Jew. Among perhaps the most famous piece of white supremacist literature is The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. First published in English in 1919 following decades of circulation in Europe, the Protocols is a forged account of Jewish global conspiracy, alleging a future revolution that allows Jews to take over the world. The Protocols include accompanying essays meant to add layers of credibility to the forgery with headings such as “How the Protocols were suppressed in America” and “More Attempts at Refutation the London Times Lends a Hand” (Marsden Reference Marsden1934). A typical excerpt includes the Yiddish term for non-Jew, an additional reminder that not even the Jews considered themselves Aryans: “The goyim are a flock of sheep and we are their wolves. And you know what happens when the wolves get hold of the flock?” (Marsden Reference Marsden1934, 172; 178). At one point, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion was estimated to be “the most widely distributed book in the world after the Bible” (Cohn Reference Cohn1998, 22).

Only a few decades after the Protocols circulated around Europe and North America, Adolf Hitler published Mein Kampf (My Struggle), which was partially written from his prison cell after his failed 1923 coup. Mein Kampf is the story of Hitler’s journey to anti-Semitism and his vision for a revitalized Germany. It contains over 400 references to Jews, more than one every two pages. Of the “Jewish race,” Hitler writes: “Was there any form of filth or profligacy, particularly in cultural life, without at least one Jew involved in it? If you cut even cautiously into such an abscess, you found, like a maggot in a rotting body, often dazzled by the sudden light a kike!” (Hitler and Murphy Reference Hitler and Murphy1925, 61). Hitler takes great care to emphasize that Jews are a race, not a religion: “It is one of the most ingenious tricks that was ever devised, to make this state sail under the flag of ‘religion,’ thus assuring it of the tolerance which the Aryan is always ready to accord a religious creed.” This racialization of Jews was critical to Hitler’s concept of the state, whose purpose is to “preserve the existence of the race” (389).

Across the Atlantic, auto-maker and industrial titan Henry Ford was responsible for printing the American version of the Protocols. In the post-war era, when German and Austrian presses struggled to print works of white supremacy in the face of state-censorship, American presses picked up the slack (Hasselbach Reference Hasselbach and Reiss1996). White supremacist literature from this period recalls the trope of a scheming, manipulative Jewish conspiracy, albeit moderated by a shift in focus from the state to civilization and culture.

The Turner Diaries, published in 1978 by William Luther Pierce and branded “the bible of the racist right” by the FBI, contains dozens of references to a worldwide Jewish conspiracy (Jackson Reference Jackson2004). The Diaries are a work of fiction written from the perspective of Earl Turner, a member of the underground white supremacist movement, that eventually overthrows the American government run by Jews and Black people. Disputing the veracity of the Holocaust, Turner claims that Jews fabricated the horrors of the Holocaust as part of a “media campaign against Hitler and the Germans back in the 1940’s” and once the “Jews convinced the American people that those stories were true, and the result was World War II, with millions of the best of our race butchered by us and all of eastern and central Europe turned into a huge, communist prison camp” (Pierce Reference Pierce1978, 30). In contrast to the Protocols and Mein Kampf, Pierce spent as much, if not more, time decrying the danger posed by Black people. As the twentieth century got underway, the hybrid focus of far-right discourse expanded, and the Jew figured more infrequently. Additionally, Pierce took great care to emphasize the shared civilizational and racial heritage of North Americans and Europeans, despite being on opposing sides of World War II.

In the twenty-first century, popular heroes of the far-right such as Christian terrorists Andre Breivik, Dylann Roof, and Brenton Harrison Tarrant all published personal manifestos. In contrast to Pierce, Breivik – who murdered 77 Norwegians, primarily children – vacillated between textbook anti-Semitic propaganda and a novel reframing of Jews as co-victims of Christians of Muslim aggression and repression. On the one hand, Breivik disputes the Holocaust, a traditional far-right trope: “As has been pointed out, the Nazis employed Jewish guards in the Warsaw ghetto, disprove the Nazi oppression of the Jews” (Breivik Reference Breivik2011, 51). On the other hand, Breivik paints a picture of historic Muslim persecution of Jews and Christians:

If one acknowledges that Islam has always oppressed the Jews, one accepts that Israel was a necessary refuge for the Jews fleeing not only the European but also the Islamic variety of anti-Judaism. Let us not forget that decolonization was followed immediately by renewed discrimination of and attacks on the Jewish and Christian minorities, and that those Jews who could get out have promptly fled to Israel (or France, in the case of Algeria). It is no coincidence that these Sephardic Jews are mostly supporters of the hard- liners in Israel. (55)

Breivik saw himself more as a citizen of Western and European cultures than as a Norwegian citizen. Perhaps no more clearly is this obvious than in his choice of title, 2083 – A European Declaration of Independence. Not only is Breivik’s tone explicitly sympathetic to Jews but he acknowledges a rationale for Israel as a Jewish state, something unthinkable in discourses like Mein Kampf or the Protocols. This serves three purposes: first, Breivik superficially distances himself from anti-Semitic Nazism; second, Breivik underlines an identitarian solution to multi-culturalism, which removes Jews from Europe; and third, Breivik signals his support for an Islamophobic agenda.

Only a few years after Breivik’s massacre in Norway, Dylann Roof murdered nine Black people in a church in Charleston, South Carolina. His orientation to anti-Semitism displayed a similar hybrid approach to depicting Jews. Roof’s manifesto, despite deploying anti-Semitic stereotypes, is nonetheless toned down from the century earlier: “Unlike many White naitonalists [sic], I am of the opinion that the majority of American and European jews are White”; however, Roof still saw Jews as problematic: “The problem is that Jews look White, and in many cases are White, yet they see themselves as minorities. Just like niggers, most jews are always thinking about the fact that they are jewish. The other issue is that they network” (Roof Reference Roof2015). In addition to a tempered anti-Semitism, Roof explained how his intellectual awakening came about as he became more aware of parallels between America and Europe: “As an American we are taught to accept living in the melting pot, and black and other minorities have just as much right to be here as we do, since we are all immigrants. But Europe is the homeland of White people, and in many ways the situation is even worse there” (Roof Reference Roof2015).

The most recent white supremacist manifesto, authored by Brenton Harrison Tarrant in 2017 before he murdered 51 Muslims in two Australian mosques, marks the culmination of the far-right narrative of Jews and Israel. In the introductory FAQ section of his manifesto, Tarrant writes, “Were/are you an anti-semite? No. a jew [sic] living in Israel is no enemy of mine, so long as they do not seek to subvert or harm my people” (Tarrant Reference Tarrant2019, 20). Like Breivik, Tarrant’s support of Jews is contingent on their presence outside of the United States. Even more than his predecessors, Tarrant explicitly conflates whiteness, “Westerness,” and civilizations in Europe, North America, and New Zealand. Tarrant begins his manifesto lamenting the low birthrates of white people and the high birthrates of non-white immigrants, primarily Muslims:

In 2100, despite the ongoing effect of sub-replacement fertility, the population figures show that the population does not decrease inline with the sub-replacement fertility levels, but actually maintains and, even in many White nations, rapidly increases. All through immigration. This is ethnic replacement. This is cultural replacement. This is racial replacement. This is WHITE GENOCIDE. (Tarrant Reference Tarrant2019, 5)

The rhetorical parallels with earlier white supremacist rhetoric, such as The Protocols, are clear – with the glaring exception of no Jewish scapegoat. But what relationship is there between white supremacist texts like these and contemporary politics?

In 2020, several hundred far-right protesters, encouraged by leaders such as the AfD MP Björn Höcke and Martin Sellner, infamous leader of the Austrian Identitäre Beweung (Identitarian Movement), stormed the Reichstag (Bennhold Reference Bennhold2020). The mob was subdued within minutes. One year later, on January 6, several thousand Trump supporters stormed the Capitol in response to Trump’s claim that the election he had lost was fraudulent. Both scenes could have been ripped from the pages of The Turner Diaries, as both mobs claimed to seize the nation back for the “people.” In Berlin, protestors waved the pre-1918 red, white, and black German imperial flag, a common symbol of white supremacism (Bennhold Reference Bennhold2020). Images from the American January 6th insurrection includes crosses, flags that read “Jesus 2020,” “Jesus Saves,” and a Confederate flag (Ciliberto and Russell-Kraft Reference Ciliberto and Russell-Kraft2021). In both cases, protestors echoed the sentiments espoused in the works discussed above, and AfD and Republican politicians either explicitly supported them or implicitly supported them by relativizing the insurrectionist nature of the events. In neither case, despite the far-right nature of both riots, was (explicit) anti-Semitism a focal point.

The best known and most popular pieces of nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century far-right discourse demonstrates how references to Jews and Israel have deviated from their historic homogenous iterations. This shift from negative to positive tone, and from racial to religious, was also accompanied by a shift in delineating the “native” through the state and nationality to cultural, civilizational, religious delineations. In short, references to Israel and the Jew are now more diverse and have been largely driven underground to platforms such as the dark we –, an anonymous network that requires a specific browser: 8kum, formerly 8chan, an extremist message board; and Telegram, an encrypted messenger system. And while anti-Semitic rhetoric can still be found in far-right platforms, such as the political platforms of the Hungarian Jobbik and the Croatian SMER, there are some important elements of discontinuity that point to a shift in nativist recruitment strategies. As I demonstrate with the cases of Germany and the United States, an increase in positive references to Jews and Israel indicates a pivot by the white supremacist elements in political groups to recruit among both devout Christians and those turned off by Nazi associations, while still signaling a commitment to identitarian agendas.

V Case Studies: Germany and the United States

German and American political parties and politicians with nativist agendas have much in common. Both advocate xenophobic agendas specifically aimed at reducing non-white immigration. Both oppose interracial relationships and both promote Christian Identitarianism. However, differences in the electoral challenges, shaped by each country’s history, dictate how they have pivoted in their use of positive references to Jews. In Germany, the taboo culture surrounding Nazism means that white supremacist rhetoric refers to Jews as co-civilizationists, members of the same Western civilization, with Christians in the face of a threatening Islam. In the United States, the Christian Identitarian focus on Israel and the rise of the Evangelical vote translates to a white supremacist discourse focusing on supporting Israel. Reframing Jews in religious rather than racial terms is politically expedient in both Germany and the United States.

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, center-right parties in Germany and the United States shifted radically to embrace white supremacist agendas and rhetoric. In Germany, the libertarian and Euroskeptic Alternative for Germany (AfD –Alternative für Deutschland) acquired a nativist, xenophobic, and anti-Muslim agenda between the 2013 and 2021 elections. They achieved this goal efficiently by coopting elements of the grassroots movements, which rose in opposition to Germany’s admission of Muslim refugees from Syria. In America, the conservative Republican party adopted a similarly xenophobic and nativist agenda, albeit with a more diverse target, aimed at both Muslims and immigrants from Latin America. Both parties also became homes for far-right intellectuals and activists previously operating outside of the spectrum of polite politics. This resulted in exceptionally vigorous support of Israel and solicitation of support of Israel’s right-wing government and solicitation of support from American Jewish politicians and leaders. Given the anti-Semitic history of far-right politics in each country, one would expect that an increase in xenophobic and anti-religious minority rhetoric would include Jews among its targets. However, the opposite proved true. What explains this pivot?

If one were to conjure up an image of the far-right in Germany, it would undoubtedly involve a Swastika. The Third Reich was the period during which a white ethno-nationalist agenda was most completely realized. At the heart of Third Reich ideology was the racialization of Jews. The depth of this racism is best exemplified by the Nuremberg Race Laws, which forbid intermarriage, stripped Jews of German citizenship due to lack of “German blood,” and established physical parameters measured under Aryan race determination tests, meant to weed out Jews through such physical characteristics as hooked noses.

The post-war partition of Germany into West and East resulted in divergent processing of a shared Nazi past. The West underwent a relatively rigorous bureaucratic de-Nazification process that involved explicit admission of culpability for the Holocaust and the removal of many Nazis from positions of power, even if large portions of the population were left untouched by the process. East Germans, under the atheistic Soviets, did not distinguish Nazi victims by religion, resulting in a smoldering, widespread anti-Semitism that was never fully extinguished. As a result of these differences in foreign occupation, East and West Germans acquired divergent associations with their outlawed former regime. In the East, Nazis and their successors acquired a positive layer of anti-Soviet resistance, while in the West identification with Nazis was highly taboo. Upon reunification in 1990, the new German government continued to disband all Nazi and Nazi-like political parties and movements under the Criminal Code Strafgesetzbuch. However, they now faced an additional challenge of emerging East German factions. Today, there are various examples of such outlawed parties and movements, such as the Wolfsbrigade 44, Wiking Jugend, Nationalistische Front, and Blut und Ehre. Still, similar parties, such as the Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD – National-Democratic Party) and the Republikaner (Republicans) have evaded legal dissolution.

In addition to the challenge posed by the German criminal code to recruitment, social desirability also shifted during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. More specifically, the rhetorical shift in white supremacist rhetoric from villainizing Jews and Israel to positively referencing them occurred due to three main developments. First, there was the significant and substantial backlash to all things Nazi-related following the fall of the Third Reich in World War II. On the right, there was a sense of shame and blame, and on the left a total disavowal. This was exacerbated by East Germany’s lack of exposure to the same narrative of German guilt for the Holocaust until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Second, the far-left in West Germany became associated with the movement for a free Palestine, most famously, the left-wing terrorist Baader-Meinhoff Group or Red Army Faction trained in Jordan with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In 1977, when 4 Palestinians hijacked a Lufthansa flight, their terms included the release of 11 Red Army Faction members. Finally, and most recently, the refugee crisis and the acceptance of over a million – primarily Muslim – refugees from Syria gave rise to new opposition movements against the perceived threat of Islam, such as Pro Deutschland (For Germany) and PEGIDA (Patriotische Europäer Gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlands – Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamification of the West). Post-war disillusionment with Nazism, the association of left-wing terrorism with Palestine, and the refugee crisis together contributed first to a social desirability bias against Nazi associations, a positive realignment of Jews and Israel with the political right, and, finally, a shift in the target of white supremacist agendas from Jews to Muslims.

In Germany, the biggest recruitment challenge to movements and parties with white supremacist agendas is staying on the right side of the law and distancing themselves from associations with Nazism. At the same time, white supremacist support of anti-Muslim and xenophobic agendas has never been higher. I argue that, combined, this creates a need for a shift in affect toward Jews. Positive references to Jews serve two purposes. First, they allow the AfD and nativist movements to credibly argue that they have no ties to Nazism and therefore remain in legal operation – a critical component to successful recruitment. Second, these references entice the many thousands of potential recruits already motivated by anti-Muslim and xenophobic sentiments. As demonstrated by myriad organizations such as Pro Deutschland and PEGIDA, which arose during the Syrian refugee crisis, today’s voters would be turned off by associations with Nazis or the risk of being associated by others with Nazis.

In the United States, parties and movements with white supremacist agendas face much different recruitment challenges than those in Germany. As in Germany, the pinnacle of white supremacist success was in the first half of the twentieth century, when a Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan was elected Governor of Indiana in 1923. By 1925, the KKK had “had anywhere from 2 million to 5 million members and the sympathy or support of millions more” (Rothman Reference Rothman2016). However, the American non-white minority was far more diverse than in Germany. While originally the focus of white supremacist ire included Blacks, Jews, Catholics, and Italians, by the end of the twentieth century, white identity expanded to include Catholics and other nonwhite Christians, as well as Italians and Irish. As the twentieth century progressed, the initial non-white target contracted and grew by turns to incorporate new “undesirable” waves of immigrants such as Chinese and Latinos. Jews faced a road, which, while broader than the path for Black people, was nonetheless heavily racialized (Jones Reference Jones2020). The lynching of Leo Frank in 1915 for being found guilty of killing a Christian girl was followed by more institutionalized forms of racism than violence, such as quotas and bans on various forms of civil society membership.

In the United States, the Republican party occupies a broader range of conservatism along the left-right continuum than the German AfD. Still, Republican elites and public intellectuals who espouse white supremacist rhetoric have achieved mainstream celebrity in the wake of Donald Trump’s election to the US presidency in 2016. Trump rose to power on a platform that advocated white supremacist policies, such as building a wall along the Mexican border and a Muslim travel ban, not dissimilar to the anti-Muslim immigrant platform of the AfD. Trump’s platform and those of his like-minded contemporaries harness Evangelical fever with white supremacy. Andrew Whitehead and Sam Perry (Reference Whitehead and Perry2020) call this Christian nationalism, based on “assumptions of nativism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and heteronormativity, along with divine sanction for authoritarian control and militarism” (10). Whitehead and Perry argue that the Christian element grants this white supremacist agenda additional power by “allow[ing] those who embrace it to express a racialized identity without resorting to racialized terms” (16). Whitehead and Perry argue that the Christian element grants this white supremacist agenda additional power. To be clear, I am not arguing that race and racism were not pillars of Trump’s agenda leading up to his 2016 election. Rather, I argue that an innovative framing of Jews and support for Israel allowed Trump and other nativist candidates who used white supremacist discourse to partially obfuscate the racist elements of their platforms. In fact, despite significant and well-documented anti-Semitic policy and rhetoric, such as the use of “existing antisemitic frames to portray their [MAGA] various enemies – mostly the Democratic Party, but also social movements such as Black Lives Matter – as being in the pocket of Jews and influenced by global Jewish capital,” (10) Trump is still seen as a champion of Israel. My analysis and comparison of the German and American cases affirms that the synthesis of Christianity and white supremacy allows for white supremacist goals to hide behind socially acceptable religious ones.

Two major shifts in the Republican electoral base are responsible for new recruitment challenges faced by white supremacist agendas. First, support for Israel evolved from a Democratic issue to a Republican cause between 1999 and 2001 (Inbari, Bumin, and Byrd Reference Inbari, Bumin and Byrd2021; Oldmixon, Rosenson, and Wald Reference Oldmixon, Rosenson and Wald2005). For over a decade, there has been a well-documented shift toward support for Israel as the Republican Evangelical base expanded (Uslaner and Lichbach Reference Uslaner and Lichbach2009; Barker, Hurwitz, and Nelson Reference Barker, Hurwitz and Nelson2008). In the first Republican presidential debate in 2015, for example, there were 12 mentions of Israel in contrast to a single reference in the Democratic presidential debate (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp2015). Political commentator Beauchamp explained “Why are Republicans so much more interested in Israel? The answer seems obvious on the surface: It’s better politics. Republicans are way more likely to sympathize with Israel over the Palestinians than Democrats are” (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp2015). This assertion is supported by public opinion data that demonstrates a widening gap in Republican and Democratic support for Israel. A 2019 Gallup survey documents that Republican voters’ sympathy for Israel over Palestine in the Israel-Palestinian conflict has risen from 59% in 2001 to 76% in 2019 (Saad Reference Saad2019). In contrast, Democratic sympathy for Israel over Palestine has only risen from 42% to 43% (Saad Reference Saad2019). In other words, while the gap between parties was only 17% in 2001, over nearly two decades later, Republican voters led Democratic voters by 33% in their support for Israel (Saad Reference Saad2019).

Second, Evangelicals with literalist Biblical interpretations and conservative social policies grew as an increasingly important share of far-right Republican votes. This shift in attitudes and party membership culminated in Trump’s 2016 presidential win (Margolis Reference Margolis2020; Martí Reference Martí2019; Whitehead, Perry, and Baker Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018). As in Germany, the politically consequential intersection of these two shifts occurred as white supremacist rhetoric reached unprecedented use in the political sphere. At the same time, this taboo language and its ideas became increasingly normalized. To achieve white supremacist goals without provocation required a strategic pivot in rhetoric concerning Israel.

The importance of Israel to Evangelicals cannot be emphasized enough. A 2019 Pew survey found that Jews were nearly three times more likely than Evangelicals to say that Trump favors Israel too much (Gjelten Reference Gjelten2019). For Evangelicals, Israel symbolizes God’s covenant with man as well as the teleological purpose of mankind through the End of Days. According to a 2017 LifeWay survey, 80% of Evangelicals believe that Judgement Day requires the return of all Jews to Israel, something that cannot occur without Israel’s existence (Gjelten Reference Gjelten2019). Ironically, this renders Evangelical support for Israel “simultaneously pro-Israel and anti-Semitic (from a Jewish perspective, in that evangelicals seek their conversion)” (Balmer Reference Balmer2020, 102).

i German and American Party Platforms

To test my theory of a shift in rhetorical target by German and American right-wing parties, I use the Manifesto Project’s collection of political party manifestos. I define religious rhetoric as any reference that implicitly or explicitly mentions a religious group, symbol, or faith. Although religious rhetoric can be found, for instance, on Facebook, Twitter, in political platforms, and in interviews, for comparability, I limit my analysis to written national-party political platforms. An argument can be made that negative references to Islam and Muslim behavior are simply proxies for prejudice and xenophobia. Similarly, positive references to Christian holidays and traditions could also be interpreted as support for a culture. I agree that extrapolating religiosity from party religious references is a mistake. However, I argue that when a nationality is demarcated using religious identities and references, there is not only a religious aspect to it, but we should look for religious explanations for the patterns in its deployment.

This article relies on an original dataset of a comprehensive list of nativist rhetoric for nine years between 2012 and 2021 from platforms collected by the Berlin Center for Social Science Research’s Manifesto Project (MARPOR 2021). I build on the significant scholarship that has already used these platforms to make important contributions to the analysis right-wing populist rhetoric (Dancygier and Margalit Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020; Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2015; Schwörer and Romero-Vidal Reference Schwörer and Romero-Vidal2020) but I focus on the rhetoric as a response to the increased political salience of religious identity. I chose to use the Manifesto Project for the comparability and the comprehensiveness of the data. While alternate measures of party rhetoric – such as those found on Twitter, Facebook, or newsletters – could undoubtedly provide important insights, other forms of party communications are less easy to compare across the US and Germany. More specifically, the German AfD as a new party with less resources disproportionately uses Facebook to spread its message. In contrast, the American Republican party has a sophisticated communications machine that has been developed over more than 150 years, which allows them to use different platforms in different ways.

My study contributes an eighth additional domain “Attitudes Towards Religion” to the MARPOR coding criteria’s existing seven domains – External Relations, Freedom and Democracy, Political System, Economy, Welfare and Quality of Life, Fabric of Society, and Social Groups. None of MARPOR’s domains or 58 categories, ranging from attitudes toward immigrants to European and regional integration, directly address religion. “Attitudes Towards Religion” is composed of any appeal that explicitly or implicitly references religion and classifies them according to six categories: (1) Positive Reference to Christianity, (2) Negative Reference to Christianity, (3/4) Positive Reference to Islam/Judaism, (5/6) Negative Reference to Islam/Judaism. Every manifesto was independently read and coded by the author and a second, native-German speaking coder before the two were reconciled. I followed the MARPOR protocol in coding individual quasi-sentences or appeals; although a sentence may contain more than one appeal, no appeal is longer than one sentence. An appeal’s subject was first identified as Christianity or minority religion, and then further classified according to type of minority religion. In the United States and Germany, nativist parties refer to an overarching “Christianity” that flattens mainstream sectarian differences such as Protestants and Catholics, so I did not further code that. I then identified the tone of the appeal, whether it is a positive or a negative reference to the subject. Within the American and German platforms, there were no anti-Jewish or anti-Christian references – solely anti-Muslim references. Negative, anti-Muslim appeals include references to 9/11, Islamic terrorism, and objections to Muslim female veiling, such as the following statement: “The headscarf as a religious-political sign should not be permitted in civil service and should not be worn by teachers or students in public schools” (AfD 2021, 86).Footnote 4 Positive references to Jews and Israel include statements against anti-Semitism, such as “Attacks on Jews and anti-Semitic insults must be consistently punished under criminal law”Footnote 5 (AfD 2021, 84) and support for Israel, such as “We recognize Jerusalem as the eternal and indivisible capital of the Jewish state and call for the American embassy to be moved there in fulfillment of U.S. law. and call for the American embassy to be moved there in fulfillment of U.S. law” (RNC 2016/2021, 48). Finally, to measure ideological shifts in line with white supremacy, I employ MARPOR’s indicators for pro-national way of life, anti-immigration, and anti-multiculturalism rhetoric.

Figure 2 presents the simultaneous use of anti-Muslim with pro-Jewish rhetoric in AfD and Republican party platforms between 2012 and 2021. I find that both parties dramatically increased their use of white supremacist rhetoric between 2012 and 2017, especially targeting Muslims. After the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Republican National Committee did not meet and voted instead to use its 2016 platform for 2020. Therefore, the percentage of positive references to Jews and Israel and negative references remain the same. The AfD, however, did draft a platform for 2021. Although negative references to Muslims declined from the 2017 platform, pro-Jewish references increased from 2017. Overall, the “othering” of Muslims did not correspond with an increase in anti-Semitic rhetoric over the same period.

Figure 2. Pro-Jewish/Israel Rhetoric in AfD and Republican Party Platforms (2012–2021)

As expected, with the exception of two references to combatting anti-Semitism, all of the references to Jews and Israel by Republicans in the US signal support for Israel. For example, “We reaffirm America’s commitment to Israel’s security”; and “Therefore, support for Israel is an expression of Americanism” (RNC 2016, 47). In Germany, by contrast, the AfD’s lone positive reference to Jews and Israel in 2017 was made all the more significant by its minimal scale in comparison to the 10% of all rhetoric made up by anti-Muslim references in their platform. At times, this vernacular explicitly describes threatening Muslim practices in contrast to an acceptable Jewish understanding of the role of religion in modern society: “The minaret and muezzin call contradict the tolerant coexistence of religions that the Christian churches, Jewish communities and other religious communities practice in modern times” (AfD 2017, 35).Footnote 6 By 2021, although the AfD’s platform was shorter, it made six times the references to Jews and Israel. However, the tone was still anti-Muslim even if the subject was pro-Jewish, as Jews were depicted as needing protection from a threatening Islam, as this example shows: “Jewish life in Germany is not only threatened by right-wing extremists, but also increasingly by anti-Jewish and anti-Israel Muslims (AfD 2021, 84).Footnote 7 This initial comparison of Germany and the US demonstrates the existence of a pivot in public-facing white supremacist rhetoric. However, a more fine-grained analysis of the rhetorical sentiments is necessary to expose the strategy behind it.

ii Germany

Contemporary German white supremacist rhetoric simultaneously employs phrases to describe Muslims that are hauntingly similar to the sort of rhetoric used to describe Jews under the Third Reich, yet political leaders are very much self-aware of perceptions of Nazi ties. In an interview, PEGIDA spokesman Christian Meyerhoff framed allegations of anti-Semitism as a leftist conspiracy among the intelligentsia and a deterrence from the real threat – Islam:

We are no Nazis… In PEGIDA there are leftists, centrists and conservatives. In the city of Kassel our committee includes a Croatian, a Jew and a secularized Muslim… Sociologists and pollsters who monitor Muslim communities in Europe regularly reveal that anti-Semitism is rampant, especially among young religious Muslims. In mosque sermons preaching against Jews is a Friday pastime… For example, last summer in Berlin, Sheikh Abu Bilal Ismail openly called for Jews to be exterminated. He was not incarcerated. This indulgence is suicidal… Writers and artists love to sign appeals. They should sign more appeals against ISIS and Boko Haram instead of being obsessed about PEGIDA… All religions should respect the law in Europe. We do not see Europe priests or rabbis calling for believers of other faiths to be murdered… We want Jews and Israelis to feel safe in Europe. We want you to be able to show your faith on Europe’s streets openly. We must stand united against Islamism and jihadism. (Schulman Reference Schulman2015)

East German Bundestag member Detlev Spangenberg is renowned for his right-wing credentials and his open embrace of the PEGIDA movement. For this and other reasons, he has been under state surveillance for years. Yet in an interview peppered with ethnically motivated anti-Muslim rhetoric concerning the dangerousness of their conflated culture and religion, Spangenberg reduced Judaism to a religion, asking of one who no longer observed: “But if you are not religious now, what is Jewish about you?” (Author Interview Reference Spangenberg2019).Footnote 8

His West German colleague, AfD Bavarian representative, Uli Henkel, also under state surveillance, compared the persecution of the AfD to that of the Jews under the Nazis:

But this country is changing for the worse and our employers, the landlords, are all foreigners, are all foreigners. Germans no longer have anything ‘local’. We don’t get anything local from Germans because the Germans are all afraid that along comes the SPD, comes the mayor of Munich… who writes to the landlords that the AfD shouldn’t rent any rooms. It’s like 1933, don’t buy from Jews. And now there are no AfD people. I mean we are in all parliaments. We are democratically elected. It’s incredible. (Author Interview Reference Henkel2019)Footnote 9

Henkel continued, emphasizing the similarities between Jews and Christians and framing them in comparable civilizational and cultural terms: “We also have Jews in the AfD. They are all people, yes, they are Jews, but they are Jews like I am a Christian and not much more” (Author Interview 2019).Footnote 10

The success of the German white supremacist rhetorical pivot is demonstrated by positive overtures to the Jewish community and its relationship with the AfD. Within the party, there is a small but vocal Jewish faction: Juden in der AfD (Jews in the AfD). They believe the AfD to be their saviors, protecting them from the threat of militant Islam, a threat which no other party takes seriously. In an interview, Artur Abramovych, leader of the youth branch of JAfD explained: “As a Jew I’ve had no negative experiences with conservatives. I actually see it as the opposite, that they have a great understanding for Judaism” (Author Interview Reference Abramovych2019).Footnote 11 In response to a question about whether Judaism was in danger in Germany, Abramovych answered: “Yes, obviously, otherwise I wouldn’t be in the AfD.” Abramovych elaborated on how his support for Israel as part of his Jewishness resonated more with the far-right AfD than with left-wing parties who showed a discomfort with religion: “For the Zionist Jews like me it is very closely related… But the Left insists that anti-Zionism has nothing to do with anti-Semitism. It’s not like that, of course.”Footnote 12 In addition to finding an ideological home for his Zionism, Abramovych also adopted seemingly unrelated white supremacist rhetoric and issue positions in return. Referencing the trope that guilt over the Holocaust – Schuldkult (culture of guilt) – led to the downfall of German pride and culture, Abramovych said “I am convinced that something like the Schuldkult exists even though I am a Jew.”Footnote 13

iii The United States

In the immediate aftermath of Trump’s 2016 presidential victory, KKK leader David Duke tweeted: “Make no mistake about it, our people have played a HUGE role in electing Trump!” (Cancryn Reference Cancryn2016). Trump and far-right Republicans who entered office alongside him shared open ties to white supremacist movements and blatantly indulged white supremacist rhetoric. However, the KKK and white supremacist movements of the twenty-first century have evolved considerably since their nineteenth-century births. With each new perceived threat, a new layer was added to white supremacy in America – from an initial anti-Black and anti-Jewish focus, to an anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant focus, to an anti-Black and anti-Brown focus. Scholars of the KKK Rory McVeigh and Kevin Estep (Reference McVeigh and Estep2019) explain that “important structural changes were taking place in the United States that cut a path for a white nationalist agenda – an agenda that not only entered our political discourse, but found a warm reception from Americans, most of whom did not think of themselves as political extremists” (11). This muddying of the ideological waters created the perfect environment for a strategic and credible shift in white supremacist framing of Jews to resonate.

On December 6, 2017, President Trump tweeted, “I have determined that it is time to officially recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel” (Trump Reference Trump. Donald2017). The dedication ceremony made it clear that the intended audience was an Evangelical, not a Jewish, one:

The dedication featured Robert Jeffress, a Trump supporter and pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas. Jeffress, who previously had declared that Jews who refuse to convert to Christianity would never be admitted into heaven, opened the ceremonies in prayer, thanking the Almighty for a president who “boldly stands on the right side of history, but more importantly, stands on the right side of you, oh God, when it comes to Israel.” John Hagee, an evangelical Zionist from San Antonio, delivered the benediction. (Balmer Reference Balmer2020, 100)

Within white supremacist Republican rhetoric, Israel plays an important role in winning over Evangelical voters. As with AfD elected officials who spout virulent anti-Muslim rhetoric but make positive references to Jews, some of the most far-right members of the Republican party support Israel. Republican Corey Stewart, a staunch defender of Confederate memorials, characterized the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement as “not just anti-Israeli, it’s an anti-Semitic movement” (Olivo Reference Olivo2018).

Similarly, Iowan Republican Congressman Steve King, whose white supremacist rhetoric was so explicit as to cost him the support of mainstream Republicans, is adamant in his support for Israel: “The State of Israel is the only consistent and reliable beacon of freedom and democracy in the Middle East, and it is a crucial ally of the United States in the region as well as in the larger war against radical Islam,” said King (2017). King continued,

Thus, I believe in advocating for a new approach concerning America’s prime policy objective between Israel and the people who call themselves Palestinians that prioritizes the State of Israel’s sovereignty, security, and borders. I have introduced my own resolution reaffirming my position to stand with Israel and reject the “two-state solution” that has failed to result in a secure environment for either Israel, a free country, or the Palestinians, who are led by Islamists and autocrats. Palestinian-led entities in the West Bank and Gaza have been and are being controlled by terrorist groups who incite acts of violence against innocents. As a result, Israel should be allowed to determine what is best for itself. My resolution encourages Israel to do just that by taking up its own course in direct negotiations with the Palestinians, instead of Washington dictating terms upon Jerusalem. (King 2017)

In short, King equated support for a two-state solution with support for Islamist terrorism, even going so far as to accuse the American government of indirect collaboration.

At a rally a few years earlier, King compared Americans murdered by illegal immigrants to Jews killed during WWII: “We have a slow motion holocaust on our hands” (Hatewatch Staff 2006). King saw nothing at odds between his support of Israel and his understanding of white Christians as co-civilizationist with the Jews with supporting white supremacy: “White nationalist, white supremacist, Western civilization – how did that language become offensive?” Mr. King asked in an interview (Gabriel Reference Gabriel2019). My point is that white supremacist rhetoric coheres with a religious and Israel-centric conception of Judaism and Jews, rather than a racial conception of Jewishness.