Introduction

Morbid obesity is a growing problem worldwide, which has led to a significant parallel growth in bariatric surgical procedures. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) are currently the most common performed procedures worldwide, although more recently the One Anastomosis/Mini-Gastric Bypass (OAGB/MGB) has gained popularity(Reference Angrisani, Santonicola and Iovino1). Bariatric surgery results in rapid weight loss and reduction of obesity-related co-morbidities such as hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes mellitus type 2 and obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome(Reference Lee and Cha2). In spite of multiple clinical benefits, bariatric surgery can lead to deficiencies in macronutrients and micronutrients as a consequence of reduced intake, changes in eating pattern, food intolerance, gastrointestinal symptoms and malabsorption(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3,Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4) . This is confirmed by the recently published systematic review by Zarshenas et al. who found an unbalanced nutritional diet with inadequate protein intake and micronutrients in many included studies(Reference Zarshenas, Tapsell and Neale5).

Multivitamin supplements (MVSs) are routinely recommended lifelong to prevent vitamin deficiencies(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4,Reference Mechanick, Apovian and Brethauer6–Reference Ledoux, Calabrese and Bogard10) . However, vitamin deficiencies are quite common after bariatric surgery despite the use of MVS, which can lead to serious long-term complications(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3,Reference Abdeen and le Roux11–Reference Heusschen, Schijns and Ploeger13) . Zarshenas et al. reported about an inconsistent adherence of MVS intake after bariatric surgery(Reference Zarshenas, Tapsell and Neale5). Many other studies have shown that long-term adherence of bariatric patients to MVS intake is poor(Reference Ledoux, Calabrese and Bogard10,Reference Schijns, Schuurman and Melse-Boonstra12–Reference Sunil, Santiago and Gougeon18) . However, it is unclear which factors contribute to patient adherence in taking MVS. Zarshenas et al. also described that further longer term and more robust studies are needed to assist healthcare professionals in providing nutritional care for bariatric surgery patients(Reference Zarshenas, Tapsell and Neale5).

The aim of this narrative review is to analyse which factors have an influence on the adherence of MVS intake after bariatric surgery, which could be complementary to the study by Zharshenas et al. Insights in determinants of behaviour are therefore important if healthcare professionals want to optimise therapeutic adherence(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19). To give an extensive overview, we will discuss the different factors that influence MVS use in patients who underwent bariatric surgery, but also review the literature on MVS in other patient groups.

Methods

PubMed and The Cochrane Library were searched from the earliest date of each database up to May 2020. The following keywords were used: bariatric surgery, metabolic surgery, multivitamin supplementation (MVS), multivitamin intake, patient compliance and patient adherence.

The literature on the adherence of MVS intake after bariatric surgery is very limited. As a result, the search results were too limited to perform a systematic review. Therefore, a narrative review was chosen in which all the available literature was included. Afterwards, all references of all publications were checked to not miss important publications.

The following subheadings were used in this narrative review: (1) patient-related factors, (2) therapy-related factors, (3) psychosocial and economic factors, and (4) healthcare-related factors. This classification was established by our research group based on the studies by Jin et al. and Osterberg and Blaschke(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19,Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20) .

The terms ‘adherence’ and ‘compliance’ are widely used in the literature. In the world of bariatric surgery, the term adherence is most commonly used in the world of bariatric surgery. The term ‘adherence’ is therefore used in this narrative review to aim for clarity.

Our research group decided to analyse other patient groups as well, because the available literature on patient adherence after the bariatric surgery was too limited.

Patient after the bariatric surgery

Patient adherence to MVS intake is a complex problem, which is largely unsolved in current bariatric practice. In general, adherence for MVS intake is considered to be poor in the long term. A prospective analysis by Ben-Porat et al. described the prevalence of deficiencies and supplement consumption 4 years after LSG(Reference Ben-Porat, Elazary and Goldenshluger16). A significant decrease in adherence over the postoperative course was documented for MVS intake (92⋅6 v. 37 % for 1 and 4 years, P < 0⋅001), vitamin D intake (71⋅4 v. 11⋅1 % for 1 and 4 years, P < 0⋅001) and calcium (40⋅7 v. 3⋅7 % for 1 and 4 years, P 0⋅002)(Reference Ben-Porat, Elazary and Goldenshluger16). Ledoux et al. described long-term nutritional deficiencies based on adherence to a standardised MVS after LRYGB(Reference Ledoux, Calabrese and Bogard10). Non-adherence patients had more deficiencies than adherence patients (4⋅2 ± 1⋅9 v. 2⋅9 ± 2⋅0 per deficiency per patient, P < 0⋅01), and the number of patients with more than five deficiencies was significantly higher in the non-compliant patient group (P < 0⋅05)(Reference Ledoux, Calabrese and Bogard10). Non-adherence patients developed more vitamin deficiencies than good adherence patients(Reference Ledoux, Calabrese and Bogard10,Reference Ben-Porat, Elazary and Goldenshluger16) .

Bariatric surgery-related factors

Postoperative complaints can cause nausea, bloating, gastroesophageal reflux disease or dysphagia, which can lead to an inadequate food or MVS intake(Reference Tucker, Szomstein and Rosenthal21). One of the most common complaints is vomiting, occurring in 30 % of patients in the first postoperative period after LSG(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4,Reference Tucker, Szomstein and Rosenthal21) . Several other causes have been described in the literature: food intolerance, stomal outlet stenosis/obstruction, marginal ulceration, intestinal obstruction, symptomatic gallstones, medication and dumping syndrome(Reference Tucker, Szomstein and Rosenthal21). Prolonged vomiting can result in nutritional deficiencies(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4). Also, diarrhoea can occur due to early or late dumping syndrome, malabsorption, lactose or fructose or other food intolerances or bacterial overgrowth(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4,Reference Tucker, Szomstein and Rosenthal21,Reference Lizer, Papageorgeon and Glembot22) . Disturbed eating behaviour like inadequate chewing, over distention of the pouch by fluids, large volume meals, unhealthy product choice and simultaneous eating and drinking are major factors in developing these complaints(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3,Reference Tucker, Szomstein and Rosenthal21) . This implies that counselling bariatric patients prior to surgery to modify their eating behaviour should be recommended.

Patient-related factors

Age and sex could be contributing factors for MVS adherence following the bariatric surgery, but this impact is controversial. Particularly in adolescent bariatric patients, adherence with MVS intake appears to be low(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4). One of the possible explanations is that if adolescents initially experience problems with MVS intake, they never re-initiate this behaviour which could lead to a decline in adherence over time(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3). Modi et al. assessed multivitamin adherence in forty-one adolescents after the bariatric surgery in a prospective observational study(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3). In their study, no significant differences were found between baseline age and patient adherence. A prospective study by Ben-Porat et al. assessed the prevalence of vitamin deficiencies and supplement consumption 4 years after LSG, which show no significant differences between MVS intake and age or sex(Reference Ben-Porat, Elazary and Goldenshluger16).

A prospective cross-sectional study by Sunil et al. analysed the relationship between vitamin adherence and demographic or psychological factors after the bariatric surgery(Reference Sunil, Santiago and Gougeon18). Non-adherence was associated with male sex and employment (full-time work).

Therapy-related factors

The MVS regimen could have a major impact on patient adherence, because taking several pills every day is a problem for many bariatric patients(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4). Forgetting MVS and difficulty swallowing MVS are the two primary barriers identified for all assessment points by Modi et al. (all studied assessment points were forgetting, inconvenience, too expensive, difficult to understand doctors instruction, hard to swallow, dosing does not match my lifestyle, side effects and would rather do something else)(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3) (see also ‘patient-related factors’).

The composition of the MVS also has a major influence on the effect. Disintegration properties of the MVS are critical factors after the bariatric surgery(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3,Reference Lizer, Papageorgeon and Glembot22) . The solubility and surface area are compromised by malabsorptive procedures, which influence drug absorption and bioavailability. Reduction of functional gastrointestinal capacity after the bariatric surgery could lead to reduced MVS bioavailability. MVS with a long absorptive phase will have compromised dissolution and absorption. Therefore, slow-release MVS should be avoided after the bariatric surgery. In addition, the solubility of MVS is affected by pH due to the decreased production of hydrochloric acid(Reference Lizer, Papageorgeon and Glembot22,Reference Malone23) . Literature on the disintegration properties of MVS in bariatric surgery patients is limited and should be the subject of future research(Reference Smelt, Pouwels and Smulders24).

Psychosocial and economic factors

It is generally accepted that psychopathological conditions and emotional support from friends and family may have an impact on the clinical outcome. However, no well-designed studies have studied this impact on MVS adherence in bariatric surgery patients.

The costs of treatment with MVS have always been considered a major barrier to adequate lifelong adherence(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4,Reference Ahmad, Esmadi and Hammad25,Reference Homan, Schijns and Janssen26) . Patients believe that the costs of specialised MVS do not weigh up to the benefits which can lead to lower adherence(Reference Homan, Schijns and Janssen26). Homan et al. assessed the cost-effectiveness of high-dose specialised multivitamins (WLS Forte; weight loss surgery) and over-the-counter (regular) MVS(Reference Homan, Schijns and Janssen26). In terms of costs, there is a price difference between specialised WLS Forte and regular MVS: €30 v. €21, respectively. However, patients in the regular MVS group developed significantly more vitamin deficiencies (30 %) compared with the WLS Forte group (14 %). Therefore, the costs for the healthcare system are significantly higher for patients that use regular MVS in case of more vitamin deficiencies due to additional return visits and associated costs for medical staff. Total costs per patient for preventing and treating nutritional deficiencies were €306 for regular MVS and €216 for WLS Forte every 3 months. In terms of incremental costs per patient, the WLS Forte was less costly(Reference Homan, Schijns and Janssen26).

Healthcare related factors

Lier et al. have performed a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in patients eligible for bariatric surgery, where a preoperative counselling group and a control group without preoperative counselling were compared on patient adherence to treatment guidelines(Reference Lier, Biringer and Stubhaug27). Preoperative counselling consisted of improvement of coping skills to initiate and maintain postoperative lifestyle changes. Results showed no significant differences in recommended daily MVS intake (87 v. 86 % for the intervention group and the control group, respectively, P 0⋅981). Preoperative counselling did not increase MVS adherence(Reference Lier, Biringer and Stubhaug27).

Ledoux et al. performed a long-term prospective study of nutritional deficits based on adherence to a standardised nutritional care after LRYGB(Reference Ledoux, Calabrese and Bogard10). Non-adherence patients had more vitamin deficiencies than adherence patients (4⋅2 ± 1⋅9 v. 2⋅9 ± 2⋅0 deficiencies per patient, P < 0⋅01), and the number of vitamin deficiencies correlated with the time from the last visit (r 0⋅285, P < 0⋅01). Time from the last visit was significantly higher in non-adherence patients with a gap of 22 months (11⋅9 ± 1⋅5 v. 34⋅1 ± 8⋅3 months for adherence and non-adherence patients, respectively)(Reference Ledoux, Calabrese and Bogard10).

There are no data how knowledgeable healthcare professionals are at recognising and prescribing appropriate dosage formulations after the bariatric surgery(Reference Lizer, Papageorgeon and Glembot22). The literature was searched for the influence of postoperative bariatric visits and postoperative psychological and behavioural medicine visits, but these subjects were not investigated in the bariatric patient population.

What can we learn from topics of adherence in patients with other chronic diseases?

Patients with other chronic diseases

Patient-related factors

Jin et al. performed a systematic review of 102 included articles on patient adherence in general(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19). Studies with a very specific patient population were eliminated to make this review generalisable to the general patient population. In this study, age was correlated to patient adherence(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19). This effect of age could be divided into three groups: the young group (<40 years), the middle-age group (40–54 years) and the elderly group (>55 years). Patient adherence in the middle-age group increased with increasing age. Overall, a higher adherence was seen in the elderly group(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19). However, no correlation was found between adherence and age in the cross-sectional questionnaire study by Yavuz et al., which studied the influence of patient characteristics and behaviour loss on patient adherence in renal transplant recipients (P 0⋅509)(Reference Yavuz, Tuncer and Erdogan28). Contradictory, the adherence among men was lower than among women (P 0⋅087). Patients who smoke and/or drink alcohol during the pre- and post-transplant periods are more often non-adherence (P 0⋅008 and 0⋅03 for smoking and alcohol, respectively)(Reference Yavuz, Tuncer and Erdogan28).

A cross-sectional survey by Stone et al. examined the relationship between antiretroviral medication regimen complexity and patient understanding of the correct regimen dosing to adherence in woman with HIV/AIDS(Reference Stone, Hogan and Schuman29). No association was found between adherence and race or ethnicity(Reference Stone, Hogan and Schuman29), which is confirmed by the review of Osterberg and Blaschke(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20). Kaplan et al. describes the opposite in a study about sociocultural characteristics that predict non-adherence with lipid-lowering medication by patients’ self-assessment of medication taking practice(Reference Kaplan, Bhalodkar and Brown30). Independent predictors of non-adherence in multivariate analysis were race (OR 3⋅7, P < 0⋅01), unmarried status (OR 2⋅1, P < 0⋅01) and lack of insurance (OR 2⋅4, P 0⋅05)(Reference Kaplan, Bhalodkar and Brown30). The influence of education level on adherence can be considered contradictory as well: no associations were found by Stone et al.(Reference Stone, Hogan and Schuman29), while an association was found between good employment and adherence (P 0⋅01) in the prospective telephone survey by Shaw et al. to analyse factors associated with non-adherence in 243 hypertensive patients who used antihypertensive medication(Reference Shaw, Anderson and Maloney31). In addition, patient adherence tended to increase with educational background (P 0⋅059) by Yavuz et al.(Reference Yavuz, Tuncer and Erdogan28). However, the review by Jin et al. suggests that patients with lower educational levels may put more trust in the advice of healthcare professionals(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19). Patients with a low income are more likely to be non-adherence(Reference Kaplan, Bhalodkar and Brown30,Reference Berghofer, Schmidl and Rudas32) , whereas costs of medical therapy pose less of a problem if patients have a higher income(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19). At the same time, adherence may be threatened if patients are not able to take time off from work for healthcare treatment(Reference Shaw, Anderson and Maloney31,Reference Lawson, Lyne and Harvey33) .

Therapy-related factors

The complexity of treatment regimen is a major predictor of poor adherence, and this is inversely proportional to dosage frequency(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20). Long duration of the medical treatment period may adversely affect adherence as well(Reference Farmer, Jacobs and Phillips34). Some studies are elaborated for illustrative purposes. Farmer et al. used prescription claim records of calcium channel blocking agents (n 9807) to determine the mean adherence ratio over a period of 2 years(Reference Farmer, Jacobs and Phillips34). The mean adherence ratio was 78⋅2 %, and the associated factors were the number of daily doses (P < 0⋅001) and the length of treatment regimen (P < 0⋅001). Once-daily regimen provides the highest adherence of 84⋅9 % followed by twice-daily regimen (79⋅9 %), three times daily regimen (75⋅2 %) and four times daily regimen (73⋅1 %). Once- and twice-daily regimens differ significantly (P < 0⋅05)(Reference Farmer, Jacobs and Phillips34). Claxton et al. performed a systematic review of the association between dose regimens and medication adherence, and seventy-six studies were included(Reference Claxton, Cramer and Pierce35). Mean dose-taking adherence was 75 % (range 34–97 %), and patient adherence decreased as the number of daily doses increased: 79 ± 14 % for once-daily regimen followed by twice-daily regimen 69 ± 15 %, three doses daily 65 ± 16 % and four doses daily 51 ± 20 % (P < 0⋅001). Significant differences in adherence were seen between one v. three doses daily (P 0⋅008), one v. four doses daily (P < 0⋅001) and two v. four doses daily (P 0⋅001). One v. two doses daily and two v. three doses daily show no significant difference(Reference Claxton, Cramer and Pierce35). Iskedjian et al. reported a high adherence rate for once-daily antihypertensive medication regimen (91⋅5 ± 2⋅2 %) compared with a twice-daily regimen (90⋅8 ± 4⋅7 %, P 0⋅026) and multiple-daily dosing regimen (83⋅2 ± 3⋅5 %, P < 0⋅001)(Reference Iskedjian, Einarson and MacKeigan36). Therapeutic non-adherence is associated with poor treatment outcomes(Reference De Geest and Sabate37). For example, poor therapy adherence results in poorly controlled blood pressure which increases the risk of myocardial ischaemia, stroke or renal impairment(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19). Paes et al. evaluated the impact of dose frequency on adherence in patients who used oral antidiabetic agents(Reference Paes, Bakker and Soe-Agnie38). Patients received these antidiabetic drugs in a medication event monitoring system container. Each opening of the package was registered, and a questionnaire was completed at the time of the study (n 91). Overall adherence was 74⋅8 % with an average of 79 % in one-daily doses regimen and 38 % in three doses daily (P < 0⋅01). Overconsumption was occur, because one-third of this patients used more doses than prescribed(Reference Paes, Bakker and Soe-Agnie38).

Hungin et al. determined factors associated with adherence using diary cards and questionnaires in patients with chronic use of the proton pump inhibitor (PPI) (n 158)(Reference Hungin, Rubin and O'Flanagan39). Questionnaires showed an adherence rate of 70⋅9 % taking the PPI on a once-daily regimen followed by 15⋅8 % on most days and 13⋅3 % took them sometimes(Reference Hungin, Rubin and O'Flanagan39). Diaries showed complete adherence in nine patients and other patients take their medicines on less than 50 % of the days.

Overall, predominant barriers of non-adherence were the length of treatment period(Reference Farmer, Jacobs and Phillips34), daily dose frequency(Reference Farmer, Jacobs and Phillips34–Reference Iskedjian, Einarson and MacKeigan36), dose omission(Reference Iskedjian, Einarson and MacKeigan36,Reference Paes, Bakker and Soe-Agnie38) , personal preference about when to take the medicine(Reference Hungin, Rubin and O'Flanagan39), fear of side effects(Reference Hungin, Rubin and O'Flanagan39) and medication knowledge(Reference Seo and Min40,Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41) . Adverse effects of medical therapy have a major influence as these effects may cause physical discomfort and scepticism about the efficacy of the prescribed medication and subsequently a lowered trust in healthcare professionals(Reference Berghofer, Schmidl and Rudas32,Reference Christensen42) .

Psychosocial and economic factors

Patients’ beliefs about causes and meaning of illness and motivation are strongly associated with their adherence of medical therapy(Reference Kyngas and Rissanen43). Adherence is better if patients feel susceptible to the illness, believe that illness or its complications pose severe consequences for patients’ health and believe that the medical therapy will be effective and beneficial(Reference Seo and Min40,Reference Lacro, Dunn and Dolder44) . Contrarily, erroneous beliefs or misconceptions may contribute to poor adherence, and fear or negative attitude towards medical therapy is a strong predictor of poor adherence(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19,Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41) . Gascon et al. identified factors associated with non-adherence in patients with hypertension using antihypertensive medicines(Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41). A qualitative study with seven focus groups was performed. Patients’ beliefs and attitude towards antihypertensive drugs and about hypertension were identified as influencing treatment adherence: fears about the long-term use of medication (‘long-term use of antihypertensives is damaging’), being stuck with antihypertensive medication for life, negative feelings about the medication (‘antihypertensives are damaging’) and adverse effects. It was also noted that patients self-experimented with the antihypertensive doses when their blood pressure was controlled (‘disease is cured when my blood pressure is controlled’). In addition, many patients stop their medication to see how they feel without it, due to low awareness about treatment, risk factors and the complications of hypertension(Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41).

Sewitch et al. prospectively identified factors of non-adherence to medication in outpatients with established inflammatory bowel disease (n 153)(Reference Sewitch, Abrahamowicz and Barkun45). Non-adherence was predicted by disease activity (OR 0⋅55, P 0⋅002), disease duration (P < 0⋅001), scheduling a follow-up appointment (P < 0⋅001) and certainty that medication would be helpful (P 0⋅040)(Reference Sewitch, Abrahamowicz and Barkun45).

Forgetfulness (30 %) was another major factor resulting in poor adherence(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20).

Emotional support reduces negative behaviour and attitude to the therapy and improves motivation and remembering to implement the therapy(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19,Reference Kyngas and Rissanen43) . The influence of emotional support on adherence of adolescents with chronic disease (asthma, epilepsy, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus) was studied by Kyngas and Rissanen in a prospective questionnaire study (n 1061)(Reference Kyngas and Rissanen43). Logistic regression was used to indicate the good adherence predictors. Support from healthcare professionals, friends and family are statistically significant factors in predicting adherence. Support from nurses was the most powerful predictor (OR 7⋅28; 95 % CI 3⋅95–13⋅42, P < 0⋅001) followed by support from physicians (OR 3⋅42; 95 % CI 1⋅87–6⋅25, P < 0⋅001), parents (OR 2⋅69; 95 % CI 1⋅42–5⋅08, P 0⋅002) and friends (OR 2⋅11; 95 % CI 1⋅28–3⋅48, P 0⋅004), all compared to patients without support. Other interesting powerful predictors were energy and willpower to take care of themselves complied with treatment regimens (OR 6⋅69; 95 % CI 3⋅91–11⋅46, P < 0⋅001) and motivation (OR 5⋅28; 95 % CI 3⋅02–9⋅22, P < 0⋅001), compared with patients without energy, willpower and motivation(Reference Kyngas and Rissanen43).

Therapeutic non-adherence leads to an increased financial burden for society, because it is associated with more emergency care visits, hospitalisations and higher treatment costs(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19,Reference Svarstad, Shireman and Sweeney46) . Of all medication-related hospital admissions in Australia and in the USA, respectively, 25 and 33–69 % are due to poor medical therapy adherence(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19,Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20) . Svarstad et al. used drug claims data of mentally ill patients to assess the association of medication adherence (neuroleptic, lithium and antidepressant) with hospitalisation and costs(Reference Svarstad, Shireman and Sweeney46). Irregularly medication use was observed in 31 % of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 33 % in patients with bipolar disorder and 41 % in patients with other severe mental illness. Irregular medication users had significant higher rates of hospitalisation in all groups compared with regular users: more hospital days (16 v 4 days, P < 0⋅01) and higher hospital costs ($3992 v. $1048, P < 0⋅01)(Reference Svarstad, Shireman and Sweeney46). In addition, psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, anger or fears about the illness are major predictors for patient adherence(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19,Reference Kaplan, Bhalodkar and Brown30) .

Furthermore, medical therapy costs or co-payment were found to be associated with non-adherence as the treatment period could be lifelong(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19,Reference Shaw, Anderson and Maloney31,Reference Ellis, Erickson and Stevenson47) . Ellis et al. analysed the influence of medicine costs on adherence in patients using statin for primary and secondary prevention (n 4802)(Reference Ellis, Erickson and Stevenson47). Increasing medicine treatment costs had a large negative effect on adherence: 76⋅2 % non-adherence with costs of $20/month v. 49⋅4 % non-adherence with costs of less than $10/month. Patients who payed $10 till $20/month were 1⋅45 times more likely to be non-adherence, compared with medicine costs less than $10/month (OR 1⋅45; 95 % CI 1⋅25–1⋅69). Patients who paid more than $20/month were 3⋅23 times more likely to be non-adherence, compared with medicine costs less than $10/month (OR 3⋅23; 95 % CI 2⋅55–4⋅10)(Reference Ellis, Erickson and Stevenson47).

Healthcare related factors

There are many methods available for measuring adherence, but no method is considered the gold standard. However, patient questionnaires and self-reports are described as simple, inexpensive and most useful methods in a clinical setting(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20).

Patient's satisfaction with clinical visits improved their medical therapy adherence(Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41,Reference Christensen42) . However, the lack of accessibility and availability to healthcare and long waiting time for clinic visits contributed to poor adherence(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19,Reference Lawson, Lyne and Harvey33,Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41,Reference Spikmans, Brug and Doven48) . Major predictors associated with poor adherence are an inadequate follow-up or discharge planning, poor provider–patient relationship and missed appointments(Reference Lacro, Dunn and Dolder44,Reference Sewitch, Abrahamowicz and Barkun45,Reference Ellis, Erickson and Stevenson47,Reference Spikmans, Brug and Doven48) . Spikmans et al. analysed the reasons for non-adherence for nutritional care clinics in patients with diabetes mellitus in a cross-sectional survey study(Reference Spikmans, Brug and Doven48). One-third of these patients skipped one or more dietician visits. Non-adherence in the clinic was associated with satisfaction with the dietitian, risk perception and feelings of obligation to attend(Reference Spikmans, Brug and Doven48).

Sewitch et al. reported total patient–physician discordance as a predicted factor of non-adherence (P 0⋅01)(Reference Sewitch, Abrahamowicz and Barkun45). Gascon et al. described major predictors in the patient–doctor interaction: patient–doctor interaction not encouraged, short time consultation, little time is spent regarding information, difficulty to understand doctor's language, eye contact is rarely made during consultation and clinical encounter created nervousness. In addition, information is provided mostly upon request by the patient and just a few questions asked by the doctor (‘there is not really any conversation, the doctor is explaining what's wrong and he doesn't even look at you’), and information is too general and not tailored to patients individual (‘the doctor gives you advice, but he don't tell how to practice it’)(Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41). The overall ability of healthcare professionals to recognise patient non-adherence is poor(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20).

Using a mobile phone reminder app probably could improve patient adherence of medical therapy. The effect of mobile phone text messaging for medication adherence in patients with chronic disease was described in the meta-analysis by Thakkar et al.(Reference Thakkar, Kurup and Laba49). Sixteen RCTs with a total of 2742 patients were included (five of personalisation, eight using two-way communication and eight using a daily text message frequency). Text messaging significantly improved medication adherence from 50 to 67⋅8 %, which is promising. The authors advise to interpret the results carefully, due to the short follow-up and reliance on self-reported medication adherence measurements. Ramsey et al. published a pilot investigation of a mobile phone application and progressive reminder system to improve medication adherence in thirty-five patients with migraine(Reference Ramsey, Holbein and Powers50). Medication adherence was significantly improved in older patients with a lower baseline adherence during the first month of this study. Self-reported app-based adherence rates were significant lower when compared with electronically monitored adherence rates.

Future research needs to examine the effect of features of mobile phone message or reminder apps, appropriate patient populations, the influence on clinical outcomes and sustained long-term effects(Reference Thakkar, Kurup and Laba49,Reference Ramsey, Holbein and Powers50) .

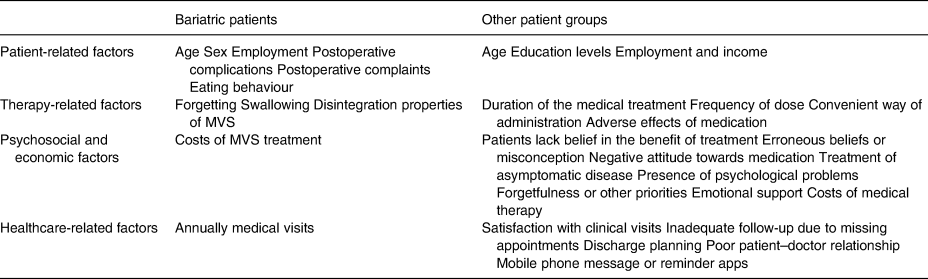

Table 1 gives an overview of the described barriers that influence patient adherence in bariatric surgery patients and other patient populations.

Table 1. Factors that influence patient adherence of medical therapy in bariatric patients and other patient populations.

MVS, multivitamin supplement.

Discussion

The long-term adherence of MVS intake after the bariatric surgery is often poor and underlying factors are unclear. This narrative review analysed which factors have an influence on the adherence of MVS intake after the bariatric surgery. Although data on the influence of demographic characteristics are limited and contradictory, many potential causes for poor MVS adherence in bariatric patients have been identified(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3,Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4,Reference Ben-Porat, Elazary and Goldenshluger16,Reference Sunil, Santiago and Gougeon18) . Among these the most important are eating behaviour(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3,Reference Tucker, Szomstein and Rosenthal21) , postoperative complications leading to gastrointestinal symptoms(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4,Reference Tucker, Szomstein and Rosenthal21,Reference Lizer, Papageorgeon and Glembot22) , treatment complexity (daily pill frequency)(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4), composition of MVS(Reference Modi, Zeller and Xanthakos3,Reference Lizer, Papageorgeon and Glembot22,Reference Malone23) and costs of MVS treatment(Reference Ziegler, Sirveaux and Brunaud4,Reference Ahmad, Esmadi and Hammad25,Reference Homan, Schijns and Janssen26) . Another important topic is that patients often believe that the costs of specialised MVS do not weight up to the benefits, which can lead to lower adherence(Reference Homan, Schijns and Janssen26). However, the available literature on the influence of these topics in bariatric surgery patients is limited. Knowledge gained from studies in other patient populations may therefore be useful for increasing long-term adherence. Major therapy-related factors are described more extensive in other patient populations. The complexity of treatment is a major predictor of poor adherence, and this is inversely proportional to dosage frequency and have been studied in many different patient populations, as well as the duration of medication treatment, side effects and medication knowledge(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20,Reference Farmer, Jacobs and Phillips34–Reference Iskedjian, Einarson and MacKeigan36,Reference Paes, Bakker and Soe-Agnie38–Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41) . The absence of disease symptoms worsened patient adherence(Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41). Patients lack of belief in the benefit of treatment, have erroneous beliefs or experience misconception. Therefore, negative attitudes towards medication may have negative effects on patient adherence(Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41,Reference Kyngas and Rissanen43) . The absence of emotional support, low satisfaction with clinical visits, inadequate follow-up due to missing appointments, discharge planning and a poor patient–doctor relationship are studied in many different patient groups and are associated with poor adherence(Reference Jin, Sklar and Min Sen Oh19,Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20,Reference Lawson, Lyne and Harvey33,Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41–Reference Sewitch, Abrahamowicz and Barkun45,Reference Ellis, Erickson and Stevenson47,Reference Spikmans, Brug and Doven48) . Perhaps, the most challenging objective for healthcare professionals is to have their patients compliant to the lifelong use of medical therapy. Early recognition and intervention may improve patient adherence. Overall, the ability of healthcare professionals to recognise patient non-adherence is poor(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20). They contribute to poor adherence by failing to explain the benefits and side effects, by prescribing complex medical therapy regimens, not giving consideration to a patient's lifestyle or the costs of the treatment and having a poor therapeutic relationship with their patients as the most important factor(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20). Not knowing patients’ priorities may have a high potential for low adherence(Reference Gascon, Sanchez-Ortuno and Llor41). However, the doctor–patient interaction on MVS adherence in bariatric patients remains poorly understood. Our hypothesis is that patients want to please the doctor due to the discrepancy between what the patient tells and what the patient actually does. This emphasises the importance of a good doctor–patient relationship.

When a patient's condition or illness is not responding to MVS, poor adherence should always be considered. One of the factors that leads to lower adherence is the belief patients have that the costs of specialised MVS do not weigh up to its benefits. Therefore, healthcare professionals should pay attention to explain the benefits and side effects when prescribing complex MVS regimens, hereby given consideration to a patient's lifestyle and the costs of treatment. Patients’ perceptions and their personal and social circumstances are crucial to their decision-making. An irrational act of non-adherence from the doctor's point of view may be a very rational action from the patient's point of view. Thus, the solution lies not in attempting to increase patient adherence, but in the development of a more open, co-operative doctor–patient relationship(Reference Donovan and Blake51). Enhancing communication between healthcare professionals and patients is an effective strategy boosting the patient's ability to follow a medication therapy regimen(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20). Other important issues are the daily dose regimen in bariatric patients and the prescription of supplements in the absence of symptoms. Bariatric patients often use three or four vitamin tablets daily, while literature in other patient populations shows that a simple regimen with one pill once a day helps to maximise adherence(Reference Osterberg and Blaschke20,Reference Iskedjian, Einarson and MacKeigan36) . Gastrointestinal symptoms or incorrect eating techniques probably play a very important role in taking MVS after the bariatric surgery, while patients often think that these symptoms are caused by the MVS adherence. However, this remains the subject of further studies. Another contributing factor is a significant postoperative change in taste following bariatric surgery such as a decrease in the intensity of taste, aversion to certain food types(Reference Tichansky, Boughter and Madan52). But the most important factor is a proper formulation of the supplements, which requires consideration of the biological, physical and chemical characteristics of all of the drug substances and pharmaceutical ingredients to be used in fabricating the product(Reference Allen53). Pharmaceutical and drug materials utilised must be compatible. Successful development of a formulation includes multiple considerations involving the drug, storage, packaging, stability and excipients. The proper combination of taste, appearance, flavour and colour in a pharmaceutical product contributes to its acceptance and a better adherence(Reference Allen53). However, these important pharmaceutical points are not studied in the bariatric patient population.

Limitations of this narrative review are the limited results of patient adherence of multivitamin intake after the bariatric surgery. Overall, a poor adherence of multivitamin intake is described, and this topic is described in almost every publication about vitamin deficiencies after the bariatric surgery. However, it remains only at percentages. Only a few studies described a limited number of factors that can affect this adherence. There is insufficient information available, therefore, to perform a systematic review about this subject.

Recommendations for future research

A prospective cross-sectional study after bariatric surgery is recommended to analyse the different barriers responsible for poor MVS adherence. Beside studying specific patient groups, it is advised to involve various healthcare professionals to educate patients on the nutritional consequences of their obesity treatment. A multidisciplinary approach, facilitating the expertise from all specialties, involved in bariatric care should also include a role for the general practitioner to improve long-term adherence.

Conclusion

Long-term adherence to MVS after the bariatric surgery is often poor, and there are only limited data on the different factors that influence MVS adherence in bariatric patients. These factors are limited to patient-related factors (age, sex and employment), bariatric surgery-related factors (postoperative complications, gastrointestinal complaints and eating behaviour), therapy-related factors (side effects and composition of MVS), economic factors (costs of MVS) and healthcare-related factors (annually medical visits). A prospective cross-sectional study after the bariatric surgery is recommended to analyse the different barriers responsible for poor MVS adherence. Knowledge gained from studies in other patient populations may therefore be useful for increasing long-term adherence. Patient-centred education is the cornerstone in achieving higher adherence rates, which emphasises the need for dedicated bariatric teams, including dietitians and mental health professionals, and also has an important role for the general practitioner.

Acknowledgments

Formal ethical approval for this study is not necessary.

H.J.M.S., S.P. and E.J.H. designed the study. H.J.M.S. conducted research and interpretation data. H.J.M.S., S.P., J.F.S. and E.J.H. drafted the article. H.J.M.S., S.P., J.F.S. and E.J.H. were primary responsibility for final content.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.