INTRODUCTION

Focus in natural language has an important communicative function: it indicates to the hearer what the speaker intends to assert. For successful communication, children need to learn to correctly identify, comprehend, and produce utterances with focus.

Previous research on how young children comprehend and produce focus has revealed an apparent paradox. Children as young as two to three years of age appear to produce prosodically marked focus correctly (Baltaxe, Reference Baltaxe1984; Furrow, Reference Furrow1984; Hornby & Hass, Reference Hornby and Hass1970; Wieman, Reference Wieman1976), but they do not seem to comprehend it in an adult-like manner before six years of age (Gualmini, Maciukaite, & Crain, Reference Gualmini, Maciukaite and Crain2003; Hornby, Reference Hornby1971; Paterson, Liversedge, Rowland, & Filik, Reference Paterson, Liversedge, Rowland and Filik2003; Szendrői, Reference Szendröi2004). Does focus constitute a genuine case in language development whereby comprehension lags behind production? Or can children's failure to understand prosodically marked focus in an adult-like fashion early in language development be attributed to task-effects or language-external cognitive limitations? The purpose of the current study is to address this question, suggesting that, with appropriately designed experimental tasks, children can show adult-like focus comprehension early on.

Focus marking in the world's languages

The focus of an utterance may be identified using the wh-question test: the part of the utterance that responds to the question is in focus (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky, Jakobovits and Steinberg1971). For example, in (1a), the focus is on the subject, and in (1b), it is on the object. Across languages, there is variation with respect to the linguistic means that mark information structure. While in some languages intonation may be the major device, in others syntactic means like word order variation or morphological markers may be more important (see, e.g., Vallduví & Engdahl, Reference Vallduví and Engdahl1996). In English, the focal part of an utterance bears prosodic prominence. (Capital letters indicate main stress throughout the paper.)

-

(1)

-

a. Subject focus: ENGLISH

Q: Who has the bottle?

A: The BIRDIE has the bottle.

-

b. Object focus:

Q: What does the birdie have?

A: The birdie has the BOTTLE.

-

Given its information-structural highlighting function, it is not surprising that focus is often (or perhaps always) marked prosodically in many languages including English (1), German (2) and French (3).

-

(2)

-

a. Subject focus: GERMAN

Der VOGEL hat die Flasche.

the bird has the bottle

‘The BIRD has the bottle.’

-

b. Object focus:

Der Vogel hat die FLASCHE.

the bird has the bottle

‘The bird has the BOTTLE.’

-

-

(3)

-

a. Subject focus: FRENCH

L'OISEAU a la bouteille.

the bird has the bottle

‘The BIRD has the bottle.’

-

b. Object focus:

L'oiseau a la BOUTEILLE.

the bird has the bottle

‘The bird has the BOTTLE.’

-

Furthermore, there is a theoretical asymmetry (Reinhart, Reference Reinhart2004) between utterances with subject focus, like (1a) and utterances with object focus, like (1b). The neutral position of prosodic prominence in sentences like (1)–(3) is believed to be on the object in these languages (Cinque, Reference Cinque1993; Reinhart, Reference Reinhart2004). The subject can get prominence by an extra prosodic operation, stress shift. One important consequence of this account is that object focus utterances are default, as they represent neutral prosody, while subject focus utterances are marked. Given this asymmetry, it is potentially possible that speakers treat utterances with stress shift on the subject and utterances with neutral, object stress differently.

At the same time, even though all three languages have default main stress on the object, they differ in how much flexibility they have in deviating from this default (Vallduví Reference Vallduví1992, Vallduví & Engdahl Reference Vallduví and Engdahl1996). English is highly flexible, because in this language stress shifting and marked pitch accent to the focal constituent can target essentially any constituent. In French, subject focus marked by shifting prosodic prominence to the subject is possible (3a), as in English, but the preferred method is to use a specific syntactic construction, the cleft (4) (Hamlaoui, Reference Hamlaoui2008, Reference Hamlaoui2009; Lambrecht, Reference Lambrecht1994).

-

(4) C'est l'OISEAU qui a la bouteille. FRENCH

it is the bird who has the bottle

‘The BIRDIE has the bottle’

German primarily uses prosody like English (2a). However, in addition to stress shift, syntactic operations, e.g., change in word order are also available (5).Footnote 1

-

(5) Die FLASCHE hat der Vogel. GERMAN

the bottle has the bird

‘The bird has the BOTTLE.’

Given such cross-linguistic differences, it is possible that prosodic focus marking is processed differently and acquired at a different rate in different languages. It could be that in English, children acquire prosodic focus marking earlier, especially in the case of shifted stress, than in French, where there is greater variation due to the prosodic accent shift option being only one of the options used by adults (Beyssade, Hemforth, Marandin, & Portes, Reference Beyssade, Hemforth, Marandin and Portes2009). The behaviour of German children is expected to be more similar to that of English children, given that German also allows stress shift freely.Footnote 2

Apart from cross-linguistic differences regarding the use of prosodic focus marking, there are two further important points to note. First, prosodic focus marking is not a stable cue. Phonetically, a wide range of pitch movements can be used for focus marking by different speakers in different contexts. Partly this is because prosodic focus marking interacts with other aspects of intonational marking, such as clause-typing (e.g., declarative), givenness marking (i.e., deaccentuation of constituents that are accessible in the discourse context). It is also subject to a high degree of phonetic variation due to speaker variation, speech rate, etc. Second, prosodic accents do not exclusively mark focus. They may have other functions, such as expressing the emotional attitude of the speaker (e.g., surprise or disapproval: The birdie has the BOTTLE?!). This means that the hearer has different options when trying to interpret prosodic accent: it could mark the focus, or the speaker could have used it to signal their emotional attitude or other pragmatic functions.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its ambiguous nature, in real-life discourse, prosodic focus marking is often a near-superfluous information structural cue. The focused constituent of a particular utterance is often predictable with a high probability from the preceding discourse. This is why it is mostly unnecessary to indicate focal prosody in writing: when reading a text, we can predict the correct accent placement from the discourse context and from the grammatical structure of the sentence. Consequently, listeners are hardly ever confronted with a discourse situation where their only cue to identify the focus of the utterance would be prosodic focus marking. For this reason, in any study where participants have to rely only on this subtle prosodic cue to determine the correct response, we can expect a relatively small effect. But prosodic focus marking is crucial for successful communication in precisely those situations where the focus of the utterance is not the only possible one given previous discourse.

The acquisition of focus

Given the ambiguous nature of prosodic focus marking, it is perhaps not surprising that previous findings on its acquisition show seemingly paradoxical behaviour: children have been found to produce prosodic focus marking correctly at least in certain pragmatic contexts as young as two years (Furrow, Reference Furrow1984, and Wieman, Reference Wieman1976, for spontaneous speech; Hornby & Hass, Reference Hornby and Hass1970, for a picture description task; Baltaxe, Reference Baltaxe1984, for elicited production), while they seem to find it problematic to interpret focal accent in an adult-like manner (again, at least in certain contexts) at least until the age of six (Lahey, Reference Lahey1974, for an act-out task; Bates, Reference Bates1976 for an imitation task; Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Liversedge, Rowland and Filik2003, for a picture selection task with children up to twelve years; Gualmini et al., Reference Gualmini, Maciukaite and Crain2003, Szendrői, Reference Szendröi2004, for truth-value judgement tasks). In fact, Hornby (Reference Hornby1971) found that the very same children who showed good production had comprehension problems.

As far as production is concerned, the available literature is largely based on spontaneous data. It is hard to design an elicitation task, as children often answer elicitation questions with a single-constituent reply. A. Chen (Reference Chen2010) employed a robot, which presented the answer in an abnormal prosody constructed from a randomized word list read by a native speaker. The children were instructed to “reconstruct the robot's answer in his/her intonation”. Chen found that both children and adults accented focal constituents (both subjects and objects) in over 90% of the cases. However, she also found that the non-focal, given constituent was also often accented both by children and adults, and, at least in the sentence-final position, more so by children. She interpreted this as evidence of partial competence of focus marking. In our interpretation, the fact that children almost always accented the focal constituent is evidence of full competence of prosodic focus marking. Adults can appropriately apply deaccenting to the sentence-final, given constituent, but children have difficulties doing so, ending up with a correctly placed focal accent and an additional incorrect default accent on the sentence-final constituent. There are at least two possible explanations that may account for why children show such over-accentuation. First, it is possible that they cannot successfully override default accent placement in the sentence-final position due to inhibition problems, which are widely documented to influence preschoolers’ linguistic abilities (Hamburger & Crain, Reference Hamburger and Crain1984; Trueswell, Sekerina, Hill & Logrip, Reference Trueswell, Sekerina, Hill and Logrip1998). Second, it is possible that children have not yet fully acquired givenness marking. There are other studies reporting deficient competence with respect to givenness marking in children (e.g., De Cat, Reference De Cat2009; Schaeffer & Matthewson, Reference Schaeffer and Matthewson2005).Footnote 3 Using a method similar to Chen's (Reference Chen2010), Müller, Höhle, Schmitz, and Weissenborn (Reference Müller, Höhle, Schmitz and Weissenborn2009) provided evidence that German four- to five-year-olds marked focus with a high pitch independently of the grammatical role and the sentence position of the constituent, further supporting our interpretation that the production of focus competence is in place by this age. We conclude then that Chen's production findings are thus consistent with the possibility that children are in fact fully competent with prosodic focus marking.

In comprehension, much of the previous research involved explicit judgement tasks (Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Liversedge, Rowland and Filik2003; Szendrői, Reference Szendröi2004). But there is reason to believe that the nature of these tasks may have influenced the results. Explicit judgement tasks come in two types. The first type involves the truth-value judgement task. For instance, Szendrői (Reference Szendröi2004) compared sentences like (6a) and (6b) with focal stress on the indirect object and the direct object, respectively. Such sentences are true and false in different situations: (6a) is true if Tigger did not throw a chair to any other creature apart from Piglet, and it is false if Tigger also threw a chair to another creature, say Winnie the Pooh. In contrast, (6b) is true if Tigger did not throw any other object to Piglet apart from a chair, and false if Tigger also threw another object, say a table, to Piglet.

-

(6)

-

a. Tigger only threw a chair to PIGLET.

-

b. Tigger only threw a CHAIR to Piglet.

-

Crucially, this truth-conditional difference is due to the presence of only in the test sentences. To see this, compare the sentences in (6) with their minimal pairs without only in (7) in the two situations described above. Both (7a) and (7b) are semantically true so long as Tigger threw a chair to Piglet, irrespective of what other events may or may not have taken place. So, in contrast to (6a), (7a) is not false in a situation where Tigger threw a chair to Piglet and also to Winnie the Pooh. It is pragmatically inappropriate to place marked focal stress on the indirect object, Piglet, in such a situation. But this does not make the utterance semantically false in this situation. Similarly, (7b) is not false in a situation where Tigger threw a chair and also a table to Piglet. It is, again, pragmatically inappropriate (in other words infelicitous) to use marked focal stress on the direct object chair, but not semantically false.

-

(7)

-

a. Tigger threw a chair to PIGLET.

-

b. Tigger threw a CHAIR to Piglet.

-

For this reason, judgement tasks relying on a different truth-value between the utterances with different focal stress placement always involve a semantic operator, such as only, which ensures that the pragmatic difference between the utterances involving different prosodic foci is augmented by a semantic difference affecting truth-conditions (see also Hüttner, Drenhaus, van der Vijver, & Weissenborn, Reference Hüttner, Drenhaus, van der Vijver and Weissenborn2004, Zhou, Su, Crain, Gao, & Zhan, Reference Zhou, Su, Crain, Gao and Zhan2012, for similar studies). This is potentially problematic because these tasks therefore also test children's ability to comprehend such operators, which may influence the results.

The second type of explicit judgement task taps directly into the pragmatic (in)felicity of the different focal stress placements in certain discourse situations. For instance, A. Chen (Reference Chen2010) relies on the fact, already illustrated above in (1), that in question–answer pairs, focal stress placement in the answer is determined by the wh-constituent. In particular, the declarative utterances in (8a) and (8b) are pragmatically inappropriate responses to the questions provided because their foci do not match the wh-element of the corresponding questions. (Pragmatic infelicity is marked by #.)

-

(8)

-

a. Q: Who did Tigger throw a chair to?

A: #Tigger threw a CHAIR to Piglet.

-

b. Q: What did Tigger throw to Piglet?

A: #Tigger threw a chair to PIGLET.

-

In accordance with this, A. Chen (Reference Chen2010) asked participants to determine whether a character gives a correct answer to another character's question in a dialogue that the child hears. But, contrary to her expectations, both children and adult participants interpreted answers that were pragmatically infelicitous, but semantically truthful, as correct. It is nevertheless possible that children, and especially adults, are able to determine the focus based on accentual information, but they do not consider the inappropriate focus placement a strong enough reason to judge the question–answer pair as incorrect. After all, it is possible to interpret correctness as simply providing an answer that is semantically truthful. Chierchia, Crain, Guasti, Gualmini, and Meroni (Reference Chierchia, Crain, Guasti, Gualmini and Meroni2001), Gualmini, Crain, Meroni, Chierchia, and Guasti (Reference Gualmini, Crain, Meroni, Chierchia and Guasti2001), and Papafragou and Musolino (Reference Papafragou and Musolino2003) make similar observations in other areas of the semantics–pragmatics interface in children.

This interpretation of the results might be supported by the fact that, in A. Chen's (Reference Chen2010) comprehension task, children had a significantly longer reaction time judging pragmatically infelicitous question–answer pairs, suggesting that they were aware of the inappropriate focal accent placement of such declarative utterances in the context. Similarly, implicit measures, in this case eye-fixation patterns, indicated sensitivity to focal accent placement in a study involving children's interpretation of sentences with the German particle auch ‘also’ (Höhle, Berger, Müller, Schmitz, & Weissenborn, Reference Höhle, Berger, Müller, Schmitz and Weissenborn2009), while explicit picture selection was non-adult-like (Hüttner et al., Reference Hüttner, Drenhaus, van der Vijver and Weissenborn2004). Zhou et al. (Reference Zhou, Su, Crain, Gao and Zhan2012) also found delayed but adult-like patterns in a visual-world eye-tracking task involving Mandarin-speaking children using the operator zhiyou ‘only’, but non-adult-like explicit judgements. Höhle, Berger et al. (Reference Höhle, Berger, Müller, Schmitz and Weissenborn2009) attribute the variation in children's performance in different tasks to different constraints the tasks place on the manifestation of the underlying knowledge, while Zhou et al. (Reference Zhou, Su, Crain, Gao and Zhan2012) argue that the prosody–pragmatics connection is less developed in children compared to adults.

Note that it is also unlikely that the comprehension problems reported in the literature would be the result of perceptual problems related to pitch or prosodic processing, given the range of evidence suggesting that even infants are highly sensitive to prosodic information, such as pitch and lexical stress patterns (e.g., Höhle, Bijeljac-Babic, Herold, Weissenborn, & Nazzi, Reference Höhle, Bijeljac-Babic, Herold, Weissenborn and Nazzi2009; Sansavini, Bertoncini, & Giovanelli, Reference Sansavini, Bertoncini and Giovanelli1997) or prosodic phrasing (Gervain & Werker, Reference Gervain and Werker2013; Nazzi, Kemler Nelson, Jusczyk, & Jusczyk, Reference Nazzi, Kemler Nelson, Jusczyk and Jusczyk2000; Wellmann, Holzgrefe, Truckenbrodt, Wartenburger, & Höhle, Reference Wellmann, Holzgrefe, Truckenbrodt, Wartenburger and Höhle2012). Further, focal accent is highly conspicuous in infant-directed speech, as it coincides with the pitch peak of the sentence, unlike in adult-directed speech, in which the pitch peak may be placed on another part of the utterance (Fernald & Mazzie, Reference Fernald and Mazzie1991). Cutler and Swinney (Reference Cutler and Swinney1987) explicitly showed that children are able to perceive focal accent.

As an alternative explanation for why children's comprehension of focus may not be adult-like, Cutler and Swinney (Reference Cutler and Swinney1987) proposed that children initially lack full competence concerning the grammar of focus. They attributed children's apparently adult-like production to an innate drive, a ‘physiological reflex’ to pronounce the parts of the utterance that evoke ‘greater excitement’ in the speaker with greater prosodic prominence. Specifically, they followed Bolinger's (Reference Bolinger1983) proposal when they proposed that “the basic mechanism underlying accent is that a greater level of speaker excitation is associated with certain parts of an utterance than with others, and those parts associated with greater excitation will tend to be spoken with prosodic prominence, i.e. accented. It is natural to suppose that the most semantically central parts of an utterance (i.e. the most ‘interesting’ parts) will be associated with greater excitation; therefore the most semantically central words will be accented” (Cutler & Swinney, Reference Cutler and Swinney1987, p. 163).

To sum up, in the literature there are essentially two different explanations to the ‘paradox of focus acquisition’, i.e., that production appears to precede comprehension. What we will call the ‘partial competence view’ maintains that children's early competence of focus is partial, as reflected by their impaired comprehension abilities. Their production abilities are either also not as fully competent as previously thought (A. Chen, Reference Chen2010), or only appear to be fully competent by some independent phenomenon masking partial competence (Cutler & Swinney, Reference Cutler and Swinney1987). In contrast, what we will call the ‘full competence view’ proposes that children's knowledge of prosodic focus marking is adult-like, as reflected by their adult-like production. Early comprehension problems do not reflect a lack of knowledge. Rather, they are due either to a reduced ability to put that knowledge to use (Höhle, Berger et al., Reference Höhle, Berger, Müller, Schmitz and Weissenborn2009) or to independent task effects arising specifically in certain truth-value or felicity judgement tasks. It is possible that the two are in fact connected. In certain tasks, children find it harder to put their knowledge to use, while other tasks allow them to manifest their knowledge more easily.

The current study

It is thus not yet fully clear whether children below six years of age have an adult-like comprehension of prosodically marked focus constructions. Furthermore, most previous experiments only tested English-speaking children. English is a language that makes strong use of prosody to mark different foci. However, as we have already illustrated in (2) and (3) for French and German, languages of the world show considerable variation in the extent to which they resort to prosodic means, morphology and syntax being additional focus-marking strategies. In the current study, therefore, we decided to explore the comprehension–production asymmetry in focus processing, using a cross-linguistic perspective. Another reason why a cross-linguistic perspective is warranted is because no cross-linguistic differences are expected under Cutler and Swinney's (Reference Cutler and Swinney1987) partial competence view. If children's production was simply indicating prosodic prominence evoked by ‘greater excitement’, as they suggest, then this should not be modulated by cross-linguistic differences.

Our hypothesis was that children have an adult-like knowledge of prosodic focus marking from an early age. Previous observations to the contrary might result from task-specific constraints that sometimes stop children from putting their knowledge to full use, especially in certain comprehension experiments. Thus, we subscribe to the ‘full competence view’. Our specific hypotheses were the following: (i) children in all three languages can exploit prosodic salience as a focus marker in comprehension from an early age; (ii) this ability may be modified by the language-specific use of different means to mark focus (with French listeners relying less on prosodic salience); and (iii) across languages, object focus utterances correspond to the default accent placement (Liberman & Prince, Reference Liberman and Prince1977). So, relevant conclusions as to knowledge of prosodic focus marking can only be made based on utterances that do not have the default accent placement, but where stress shift is involved, such as subject focus utterances.

To test these hypotheses, we designed a novel comprehension task, created to alleviate task-specific constraints and semantic–pragmatic ambiguity, to provide the first direct empirical evidence in favour of early adult-like competence in prosodically marked focus comprehension. We tested three-, four-, five-, and six-year-old children speaking English, German, or French to uncover any potential developmental trends and cross-linguistic differences. To the best of our knowledge, such a comprehensive, cross-linguistic study across the preschool to school age has not been previously performed.

EXPERIMENT: THREE-, FOUR-, FIVE-, AND SIX-YEAR-OLD CHILDREN ARE SENSITIVE TO PROSODIC FOCUS MANIPULATIONS IN A CORRECTIVE CONTEXT

To determine whether children show comprehension of focal differences marked by changes in accent placement alone in English, German, and French, we designed a comprehension task in which children correct false assertions made by the experimenter with either subject or object focus. Recall that focus marking by prosodic accent is an unreliable cue for hearers because prosodic accents can also have other grammatical or emotive functions. This means that, in real life, prosodic focus marking is often a superfluous cue: the focus is predictable from the previous discourse. In an experimental situation, we control the discourse and situational context, and make participants have to rely on the prosodic cue alone to identify the focus of the utterance. This is an unnatural and therefore hard task for them. For this reason, we must find a discourse situation where different focus possibilities are expected naturally. Correction is often identified as the strongest pragmatic cue for focus (Féry, Reference Féry2013). This means that corrective contexts may be sufficiently easy to process for children to potentially show their ability to comprehend focus. For this reason, our experiment involved a scenario where the participant was invited to correct the experimenter's utterance (for similar designs see also S. E. Chen, Reference Chen1998; Hornby, Reference Hornby1971). In the target condition, children were exposed to a picture while the experimenter made an incorrect assertion with contrastive focal accent on either the subject or the object.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental conditions (subject or object focus).

We tested 52 English native speaker children and 16 English adults, 47 French native speaker children and 11 French adults, and 57 German native speaker children and 11 German adults in the SUBJECT condition, and 57 English native speaker children and 24 English adults, 51 French native speaker children and 10 French adults, and 59 German native speaker children and 12 German adults in the OBJECT condition. The exact age ranges are reported in Table 1. The children's parents and teachers reported no cognitive disorders or speech delay. Out of the 407 participants, 203 were females. We tried to keep group sizes as similar as possible, but practical problems resulted in a certain amount of variation.

Table 1. English, French, and German participants’ breakdown of age in the SUBJECT and OBJECT condition

Participants with more than one irrelevant or missing response were excluded. We also excluded participants with less than three correct responses for the fillers. This resulted in the exclusion of 2 French (age 3: 2), 18 German (age 3: 16; age 6: 1; adults: 1) and 16 English (age 3: 5; age 4: 9; age 5: 2) participants who were tested, in addition to those included in the analyses described above.

Material

The material consisted of test, control, and filler items.

The test items in both the SUBJECT and the OBJECT condition involved a picture, as in Figure 1, accompanied by an utterance with subject or object focus, as given in Table 2.

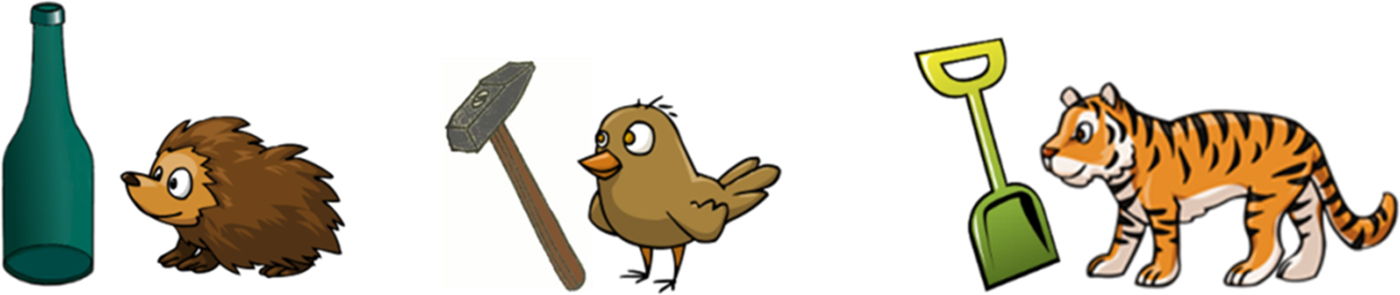

Fig. 1. Example of visual stimulus of test item (OBJECT and SUBJECT condition).

Table 2. Example of audio stimulus of test items in English, French, and German

Each visual stimulus depicted two contrast sets (Figure 1): a set of animals (e.g., hedgehog, bird, tiger) and a set of things (e.g., bottle, hammer, shovel). (So each picture contained an animal and an object referred to, a contrasted animal or object, and a third animal and object distractor.) Based on the idea that marked focal stress on the subject or the object would indicate to the hearer which contrast set is relevant for the speaker, we expected the responses to diverge in the two conditions as follows (see Table 3 for a summary). In the SUBJECT condition, we expected that responses would make reference to the contrast set of animals, e.g., for the test stimulus “The BIRDIE has the bottle, right?”, the response is expected to make reference to the hedgehog, which is the animal with the bottle in the picture. In the OBJECT condition, we expected that the responses would make reference to the contrast set of things, in particular, to the hammer, as this is what the bird has in the picture.

Table 3. Expected responses to the test items in English, French, and German

The visual stimuli were chosen in such a way that (i) none of the animals or things appeared more salient than the others, and (ii) the names of the animals and things that the experimenter referred to and the participant was expected to refer to are known to three-year-old children, the youngest age group tested in the study. The words referring to these animals and things in all three languages (i) consisted of (at least) two syllables, for easy detection of prosodic prominence, and (ii) featured the regular word stress pattern of the language in question. The position of the contrasting animal was counterbalanced for side.

In addition to test items, we also used control items, which were similar in grammatical form to the test items, except that they were true and required no correction by the participant (e.g., DUCKIE has the scissors, right? vs. Duckie has the SCISSORS, right?). These sentences allowed us to test for participants’ correct understanding of and attention to the task.

Filler items also consisted of an utterance and a corresponding visual stimulus. The visual stimuli were the same as in the test items. The filler utterances were sentences not containing a focus construction. Half of them made a correct, the other half an incorrect, statement about the animals or objects in the picture, referring to them as a group (e.g., All animals are awake.).

The audio stimuli were presented by the experimenter, who was a female native speaker of the experimental language. It was decided that prerecording utterances would be detrimental to the pragmatic felicity of the experimental situation and would make the task less engaging for the youngest participants. The experimenters were trained to present the stimuli with a clear contrastive focal accent on the subject or object, depending on the condition.

Procedure

Each experimental session started with a warm-up phase to familiarize children with the experimental set-up (especially with the task of rejecting and correcting or accepting statements about the pictures) and to make him or her feel comfortable in the testing situation. A puppet was introduced to the children and they were told that the puppet wanted to learn the names of colours. Coloured dots were presented on separate slides on a laptop screen to the puppet and the child. At each slide, the puppet would make a statement about the colour on the screen, which was sometimes correct and sometimes incorrect. Children were encouraged to listen to the puppet's statement and, if wrong, correct him, to help him learn the names of the colours. The warm-up phase ended with all the colours appearing on the same screen, and the puppet correctly enumerating their names. After this, the puppet was put on the side, as he was tired after learning all the colours, but remained present for comfort.

Before the main test, the experimenter explained that in the next game she would show the participant some pictures, but she herself would not look at them. Rather, she saw them the day before and she would now try to remember them. She then asked the children to correct her if she was wrong, just like they had corrected the puppet earlier.

In the main test, participants were presented with four test items that were incorrect in a between-subjects design (SUBJECT condition and OBJECT condition), four control items and four fillers. The between-subject design was chosen because pilots revealed a strong carry-over effect between the two test conditions. Participants were randomly assigned to the SUBJECT condition group or the OBJECT condition group.Footnote 4 The twelve items were presented in two pseudo-random orders, counterbalanced across participants.

The test session was preceded by a practice session comprising two fillers for each participant, one of which matched the picture, while the other did not match the picture. The practice trials did not use utterances with marked prosody. There was only one way in which the mismatch practice item could be regarded as not matching the picture. If participants failed to provide a correction for the experimenter's mismatched statement, the experimenter encouraged them to do so, including modelling a correction, and explained the task again. In this case, the practice items were repeated to make sure that the participants understood the task clearly. A participant who still failed to perform correctly on the practice items would have been excluded from the study, but that situation did not arise. No feedback was given during the test phase of the experiment.

RESULTS

We coded participants’ responses as follows. If in their responses they referred to the relevant member of the contrast set of animals (i.e., the hedgehog in Figure 1), we considered their response as an instance of ‘subject correction’. If they referred to the relevant member of the contrast set of things (i.e., the hammer in Figure 1), their response was counted as an instance of ‘object correction’. If they referred to both in a single utterance, this response was considered as ‘double correction’ (e.g., The birdie has the HAMMER (and) the HEDGEHOG has the bottle.). If they failed to refer to either of these elements, we treated their responses as ‘irrelevant or missing’. We did not analyze the responses prosodically, because many of the responses were single-word, fragment responses, where a prosodic analysis makes little sense.

Before analyzing the experimental trials, we checked compliance and general understanding. The proportion of correct (YES) responses in our control items was close to 100% in all groups of the experiment, suggesting that all age and language groups performed the task as expected.

Participants’ responses for the test items are shown in Figure 2 for the three languages, English, French, and German, respectively. We used the percent subject correction in each of the conditions as the dependent variable in our statistical analyses. Our predictions were that if children have full competence in prosodic focus, then those children who received the SUBJECT condition will give a higher proportion of subject correction responses than those children who received the OBJECT condition. A similar result was expected of adults. The predictions of the partial competence view would be that at least the younger children would fail to show a different performance in the two conditions. In terms of cross-linguistic variation, we expected that French adults may show less sensitivity to our prosodic manipulation, i.e., less pronounced difference in the proportion of subject responses between the SUBJECT and OBJECT conditions. Consequently, we were interested to see if this made it harder for French children to achieve full competence, and that perhaps they only achieve it later compared to their English and German peers.

Fig. 2. Proportion of subject corrections, object corrections, and double responses by English, French, and German three-, four-, five-, and six-year-old and adult participants in the test conditions. “S” indicates subject group, “O” indicates object group. Across ages and language groups, proportion of subject correction in the subject group is higher than in the object group. Overall subject corrections are less frequent for French than English participants.

We performed a three-way ANOVA with between-subject factors Language (English/French/German), Condition (SUBJECT/OBJECT) and Age (3y/4y/5y/6y/adult). We obtained a significant main effect of Condition (F(1,340) = 63·291, p < ·0001), because participants in the groups that were exposed to the SUBJECT condition provided more subject corrections than participants in the groups that were exposed to the OBJECT condition. We also found a significant main effect of Language (F(2,340) = 3·5041, p = ·0312), due to English participants giving more subject correction responses overall than French participants (Scheffé post hoc test: p = ·041).

Since we used three categories to code responses (subject correction, object correction, and double correction), we complemented the above ANOVA with a similar one using the proportion of double corrections as the dependent variable. This ANOVA with between-subject factors Language (English/French/German), Condition (SUBJECT/OBJECT), and Age (3y/4y/5y/6y/adult) revealed a main effect of Language, no effect of Condition or Age, and no significant interactions. Scheffé post hoc tests showed that the main effect of Language was due to the fact that German participants used double correction more often than English participants (although not more often than French participants).

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we tested how three-, four-, five-, and six-year-old English-, German-, and French-speaking children and adults understand prosodically marked subject and object focus in order to investigate whether children already show adult-like comprehension at this age in our correction task. This is relevant, as previous studies revealed a potentially paradoxical pattern of results: children were found to produce focus in an adult-like manner much earlier than when they were found to comprehend it. We hypothesized that, rather than having a paradoxical competence, children show this behaviour due to task constraints. We therefore designed an experiment to try to circumvent these constraints. We found that, independently of age and language, more subject corrections were provided in the subject condition than in the object condition, suggesting that French-, German-, and English-speaking adults and three- to six-year-old children are sensitive to the different prosodic marking of subject versus object focus in their comprehension. We also observed, however, that the native language influences this sensitivity, as English participants provided more subject corrections than French participants. We obtained no effect of age, suggesting that three-year-olds already understand prosodically marked focus. However, it needs to be noted that our individual age groups were relatively small.

This result supports our hypothesis that prosodic focus marking in the three tested languages is interpreted correctly by children from an early age. This is consistent with the production findings in the literature, which have indicated early mastery of prosodic focus marking. We propose that the inconsistency between our finding and some of the other findings from comprehension experiments can be explained by task effects. The comprehension studies that found that children have difficulties with the interpretation of marked focal stress used explicit judgement tasks. Our experiment used a more naturalistic setting involving a corrective situation, and there was no operator present in our test sentences. The participants had to use the pragmatic information provided in the form of the different accent placements to identify the focus of the utterance and thus identify the relevant contrast set for their correction. But they did not have to make an explicit judgement of pragmatic felicity (cf. A. Chen, Reference Chen2010).

Our study design was quite similar to that of Hornby (Reference Hornby1971), but there were two major differences. First, the current test is performed in a pragmatically felicitous situational setting. We are asking the child to check whether the experimenter remembers correctly, thus making correction a highly felicitous response. Second, we have three animal–object pairs in our visual stimuli. We decided to do this because a pilot study with only two pairs resulted in a high number of incorrect responses even for adults. Our interpretation of this pilot result was that with only two options in the picture, the relevant contrast can be inferred by exclusion even if the child corrects the non-focal constituent. By way of illustration, if the experimenter says “The BIRDIE has the bottle”, when in fact the hedgehog does and the birdie has the hammer in the picture, with no third animal–object pair, the focally non-matching answer “No, the birdie has the HAMMER.” is actually an appropriate response. The hearer can draw the simple inference that if the birdie has the hammer, then the hedgehog must have the bottle. No such inference can be drawn with three animal–object pairs in the picture. So, a focally non-matching utterance is not felicitous in this case.

The different focal prosodic patterns in our test sentences provided a strong enough cue for participants to determine the relevant contrast set for the correction most of the time. At the same time, focal accent placement on the subject constituent is clearly not an unambiguous cue: prosodic focus does not determine the relevant contrast set for correction in an exclusive manner. Other factors are at play, one of which is the unmarked nature of accent placement on the object in all three tested languages. The object is where main stress falls in neutral (i.e., out of the blue) utterances. Indeed, participants across the board had an object correction bias in their interpretation of the test utterances. This reflects their unwillingness to interpret shifted stress as an indication to determine the relevant contrast set for correction. Similarly, one further factor that might have contributed to our results was the fact that subjects in our test sentences always referred to animate creatures, i.e., different animals, while (grammatical) objects always referred to inanimate things (e.g., bottle). If animate beings are more likely to be interpreted as topics and inanimate things as foci (e.g., Aissen, Reference Aissen1999; Comrie, Reference Comrie1989), then our set-up introduced a further object-focus bias into our experiment. This could have contributed to the relatively high proportion of object corrections in the subject condition.

Another factor that might have contributed to a less than overwhelming proportion of correct performance in both our conditions is the non-deterministic nature of prosodic focus-marking, i.e., that pitch accents do not always mark focus, but can mark other grammatical and emotive content too. Participants understood correctly that prosodic accent can indicate focus, in which case they should use it to determine the intended contrast set, hence the significant difference in the proportion of subject responses between the two conditions, but they did not always interpret the pitch accent as focal, diminishing the proportion of correct responses in the two conditions. Nevertheless, our results show that the prosodic information can work against this bias, as indicated by the higher number of subject corrections in the SUBJECT-focus condition compared to the OBJECT-focus condition.

Indications for a cross-linguistic variation in the comprehension of focal accent were revealed by differences between French and English participants, French participants having an overall bias against assigning a subject correction interpretation compared to English participants (Figure 2). This was not unexpected, given that prosodic manipulation of focal stress is less widespread in French than in English (Hamlaoui, Reference Hamlaoui2008, Reference Hamlaoui2009; Lambrecht, Reference Lambrecht1994) and is subject to more variation (Beyssade et al., Reference Beyssade, Hemforth, Marandin and Portes2009). So, it is understandable that marked accent on the subject was interpreted by French participants less often as a cue to identify the contrast set of animals as the relevant one for correction. In French, there is a more natural way to express that intended meaning, i.e., the cleft. But, within their overall general reticence to assign a subject focus interpretation to utterances with marked stress, French participants, including children, reacted to the prosodic manipulation in the SUBJECT condition in the expected way.

One further cross-linguistic difference was revealed by the analysis of the double responses: German participants of all ages provided more double correction responses than English participants, independently of the experimental condition. It is possible that, despite our best efforts to harmonize experimental practices and training our experimenters in prosody and in other aspects of the experimental setting, slight differences may have remained, potentially resulting in more double corrections overall in the German group. Given that we tested a subtle pragmatic cue, our experiment is potentially sensitive to minor differences in the testing situation. However, crucially, there was no difference between the proportion of double corrections between the two test conditions, nor between the age groups. Thus, this general baseline difference between German and English participants’ double corrections notwithstanding, our main findings remain valid. It is, of course, also possible that the difference in proportion of the double corrections is not caused by an unintended procedural difference but is in fact genuine. We can only offer a speculation in this direction. Numerically, it seems that the group that showed an eagerness to give double correction responses were the German six-year-olds. Davies and Katsos (Reference Davies and Katsos2010) have found that this age-group is particularly prone to over-informativeness. By this age, French and English children will have been in formal school education for at least two years. But German children only go to school at age six. So, it is possible that English and French children's natural tendency to give over-informative answers at this age would have been dampened by their experience with formal education, where they learn not to give over-informative answers.

Our study only involved three languages, all of which are so-called stress-focus languages, which use prosodic means to mark focus. There are some reports of languages that lack prosodic focus marking altogether, or have a morphological focus marker, e.g., some Chadic languages (Hartmann & Zimmermann, Reference Hartmann and Zimmermann2007). At the same time, it appears to be the case universally that languages that have a stress system use stress (or pitch accents more generally) to mark focus (Reinhart, Reference Reinhart2006). If further empirical work on different languages turned out to support the validity of this language universal, this would raise the possibility that this stress–focus correspondence is some kind of language primitive. If so, we would in fact expect it to be acquired very early, or potentially already available to children at birth. Our results are consistent with such a state of affairs. In fact, if this is correct, children growing up with languages without stress–focus correspondence would show sensitivity to prosodic focus marking early in development and would lose it as a result of experience with the native language. This is not easily testable empirically though, because the loss of sensitivity might occur too early (S. E. Chen, Reference Chen1998).

Our study did not reveal any developmental change in the acquisition of focus marking, with even three-year old children showing the same performance patterns as adults on our task. To test whether there is developmental change earlier, future research will need to investigate younger children, perhaps using online measures such as eye-tracking to ease the task burden further.

On a theoretical level, our results support the ‘full competence view’ of prosodic focus, as opposed to the ‘partial competence view’, proposed by Cutler and Swinney (Reference Cutler and Swinney1987) and A. Chen (Reference Chen2010). We found that, in a pragmatically felicitous task, where children did not have to interpret semantic operators, such as only, and where they did not have to make an explicit felicity judgement, they showed adult-like understanding of prosodic focal differences. The reason why Cutler and Swinney's (Reference Cutler and Swinney1987) proposal fails to explain our findings satisfactorily is that according to them accentual information for children is merely an expression of ‘greater excitement’. So, for children accentual information is extra-grammatical. As a consequence, no cross-linguistic differences are expected under Cutler and Swinney's proposal. But we did find such a difference, namely that French participants showed an overall reticence to give subject correction responses compared to English participants, suggesting that prosodic focus marking is rooted in children's knowledge of their native language.

CONCLUSIONS

Our experiment found evidence that children and adults are sensitive to prosodic manipulations of focal accent in English, French, and German. Our results therefore support the ‘full competence view’ of the acquisition of focus, which argues that children's knowledge of prosodic focus marking is in place early. This is in accordance with their adult-like performance in production, and also in our comprehension task, which did not rely on a semantically determined truth-value difference between our conditions based on the use of semantic operators, such as only, or on explicit pragmatic felicity judgements on the part of the child.