Introduction

Since 2011, archaeology has been employed as an innovative vehicle to support military veterans and serving personnel recovering from traumatic experiences or adapting to life-changing physical injuries. Although a number of initiatives now exist, only two peer-reviewed articles examining the role of archaeological fieldwork in the rehabilitation of veterans have been published to date (Nimenko & Simpson Reference Nimenko and Simpson2014; Finnegan Reference Finnegan2016). These two studies, conducted by military medical professionals, are based on small convenience samples, but both indicate the effectiveness of archaeology in terms of an uplift in wellbeing for the participants. With greater numbers of veterans now participating in a range of archaeological projects, there is a heightened need for more extensive, longitudinal data on the impact on wellbeing during and following excavation, along with a rigorous evaluation of the potential risks. The current prevalence of informal observation and a reliance on non-systematically collected data obscures a full understanding of the effectiveness of this use of archaeology, and whether different individuals, each with unique requirements and experiences, respond better or worse to different projects or settings. There is also a need to explore the specific position of archaeology, not simply as providing the backdrop for a group activity, but rather in terms of ownership, particularly with regard to the supervision of fieldwork and stewardship of the historic environment. While these varied initiatives now offer many examples of high-quality fieldwork, including via developer-funded investigations (e.g. Osgood & McCulloch Reference Osgood and McCulloch2018; Figure 1), the archaeological and mental health outcomes require thorough investigation.

Figure 1. Veterans excavating a Hessian Mercenary dugout with Pre-Construct Archaeology at Barton Farm, Winchester in July 2018 (photograph © Harvey Mills).

In bridging the disciplines of archaeology and psychology, the authors of the current article have three aims: to consider the evolution of support for veterans and the emergence of veteran-focused archaeology; to review the extant literature; and to present results from the largest ‘service evaluation’ undertaken to date. A service evaluation is a commonly used tool in the assessment of psychological change in service users over time. Routine service evaluations utilise standardised measures, recognised as valid and reliable measures of psychological constructs, such as depression and anxiety. These measures make it possible to assess change between a baseline so that the existing health needs are understood, and an end point, so that any change can be calculated and demonstrated.

In this article, we concentrate on the situation in the UK because it was here that veteran-focused archaeological initiatives were first established. The phenomenon has, however, inspired an international movement, with British-led projects taking place in Cyprus, Belgium and France (and Polish veterans working with Operation Nightingale in the UK (Figure 2)); a programme established specifically to support US veterans that has excavated in the UK, USA and Israel; and, since 2017, Georgian, British, Ukrainian and Estonian veterans excavating at the site of Nokalakevi, in west Georgia. The global interest in this therapeutic use of archaeology makes it increasingly important that the benefits and risks are better understood.

Figure 2. Polish veterans taking part in an excavation to recover a Battle of Britain Hurricane, West Sussex 2015 (photograph © Harvey Mills).

Background

The first efforts in the UK to provide support for retired and injured soldiers included the establishment in 1681 of the Royal Hospital at Chelsea by Royal Warrant. King Charles II saw, in the plight of those “broken by age or war” (Ingham Reference Ingham2016: 33), an unfulfilled debt owed to those who had served their country. It was the First World War, however, which transformed the landscape of charitable work. The sheer number who served, and the dependence on irregulars, was as unimaginable to previous generations as the scale of the losses and the new horrors of mechanised war. A proliferation of associations and federations were formed through which ex-servicemen sought to support each other, such as the Comrades of the Great War, the National Association of Discharged Sailors and Soldiers, the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilised Sailors and Soldiers, and the Officers’ Association, all of which merged in 1921 to form the Royal British Legion.

The physical impact of the war was most evident in the large numbers of men who lost limbs, and, in subsequent years, the first branch of the Limbless Ex-Service Men's Association (LESMA) was formed in Glasgow, later merging with other regional branches to form a national charity (BLESMA). The Ex-Servicemen's Welfare Society, founded in 1919 and now known as Combat Stress, was a ground-breaking approach to mental healthcare, with rehabilitation promoted as an alternative to the Mental War Hospitals and civilian asylums into which many of those suffering from ‘shell-shock’ were placed. The society created work programmes to help veterans retrain and support themselves in its first ‘recuperative home’ in Putney, London, from 1920. The remainder of the twentieth century saw the establishment of further charitable institutions and, crucially, the founding of the National Health Service (NHS) in 1948.

By spring 2007, the British military had, for the first time in over a generation, seen four years of continuous deployment in two simultaneous, major conflicts. The social impact of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—including the numbers wounded and requiring treatment through the NHS, and the repatriation of the fallen through the streets of Royal Wootton Bassett from RAF Lyneham—contributed to a growing public awareness of the limitations in state provision. At the same time, the concept of a ‘Military Covenant’ (Armed Forces Covenant; Ministry of Defence 2016), a formal recognition of the debt owed by civilian society to its military personnel, gained political traction through media coverage and lobbying by the Royal British Legion (Ingham Reference Ingham2016: 2). By the end of 2007, the newly founded charity Help for Heroes was able to capitalise successfully on the growing public desire, given voice by several national newspapers, to ensure that current and former service personnel were fully supported in their recovery and transition back to civilian life. The change in British public opinion in this period might explain the huge interest in Operation Nightingale from the outset, and the continuing support for veteran-focused archaeological projects in the years since.

Archaeology as a non-medical intervention

Previous generations of returning service personnel were advised not to talk about their traumatic experiences for fear of alarming their loved ones; many thus retained the damaging effects of these experiences into old age (Burnell et al. Reference Burnell, Coleman and Hunt2010, Reference Burnell, Crossland, Greenberg and Hacker-Hughes2017). Recently there has been a recognition of the importance of being able to talk through, and make sense of, those experiences, and by far the most effective support networks include individuals with shared or similar experiences. Peer support, as a non-medical intervention, is thought to be a promising way to help veterans, and can complement psychological intervention (Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Thomas, Melton, Harden and Eastwood2018). Thus, an important aspect of archaeological fieldwork may be the peer support that it provides.

Against this background, in 2011, an initiative called Operation Nightingale was developed by Sergeant Diarmaid Walshe VR of the Royal Army Medical Corps, at the time attached to 1 Rifles, and Richard Osgood, the Senior Historic Advisor to the Ministry of Defence's (MoD) Defence Infrastructure Organisation (Walshe Reference Walshe2013). The scheme sought to promote an innovative way of facilitating the recovery and rehabilitation of serving soldiers through participation in archaeological fieldwork and post-excavation tasks. In September 2011, a group of serving soldiers from 1st Battalion, The Rifles, took part in excavations of archaeological material redeposited by badger activity at East Chisenbury Midden on Salisbury Plain. This represented the first iteration of the Operation Nightingale initiative, with Wessex Archaeology and English Heritage providing specialist support (Walshe et al. Reference Walshe, Osgood and Brown2012). Shortly after the work at Chisenbury, eight of the soldiers took part in excavations at East Wear Bay, Folkestone, as part of a community archaeology project directed by Keith Parfitt of Canterbury Archaeological Trust (Heritage Daily 2011).

The following year, the Defence Archaeology Group (DAG) was established by individuals already actively supporting Operation Nightingale in order to help facilitate its work, but it was somewhat overtaken by events as the latter quickly established its own momentum. From 2011–2015, when its focus shifted to project management rather than participant recruitment, Operation Nightingale provided places on a variety of projects, including further seasons at East Chisenbury Midden; at Barrow Clump in Wiltshire (Figure 3; Pitts Reference Pitts2012: 6), where it worked for three seasons; and the investigation of a crashed Spitfire on Salisbury Plain in 2013 (Osgood Reference Osgood2014). Operation Nightingale was recognised with a special award at the British Archaeological Awards in 2012, and won ‘Best Community Action Project’ in the 2016 Historic England Angel Awards. Perhaps one of its most significant achievements, however, was to inspire some of its participants to establish new, veteran-led archaeological initiatives in 2015: Breaking Ground Heritage (BGH), Waterloo Uncovered and American Veterans Archaeological Recovery (AVAR).

Figure 3. Veterans excavating a sixth-century Anglo-Saxon grave at Barrow Clump, July 2018 (photograph © Harvey Mills).

BGH was founded by Richard Bennett, a former Troop Sergeant in the Royal Marines and co-author of the present article, who first experienced Operation Nightingale as a participant in 2012 before going on to study archaeology at the University of Exeter. Operation Nightingale now focuses on facilitating veteran-focused archaeological projects on land owned by the MoD, often working in partnership with BGH, the latter recruiting and providing pastoral care for participants on projects such as Operation Nightingale's return in 2016 and 2017 to East Chisenbury Midden, and Barrow Clump in 2017 and 2018. This complementary arrangement enables the MoD to continue supporting veterans in a capacity that also manages its estates. BGH also organises its own fieldwork away from MoD land, including the excavation of both a First World War tank and a section of the Hindenburg Line at Bullecourt, France (Figure 4). Since 2015, BGH has facilitated over 300 placements on more than 35 veteran-focused archaeological and heritage-based projects, and was highly commended by the judges of the 2018 Marsh Award for Community Archaeology.

Figure 4. A wounded-in-service veteran, who lost a leg due to an improvised explosive device, carefully excavates the foot and boot of a British soldier from the 1917 Battle of Bullecourt (photograph © Harvey Mills).

Waterloo Uncovered was established by Mark Evans and Charles Foinette, who had previously studied archaeology together at University College London before joining the Coldstream Guards (Mark Evans pers. comm.). By 2015, Evans had retired from the army following a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and had found his way back to archaeology through Operation Nightingale. Foinette, still serving and now a Major, was involved in running the Coldstream Guards’ Waterloo bicentenary celebrations. The Battle of Waterloo and the defence of Hougoumont Farm in particular rank highly in the history of the regiment. In 2015, a team of archaeologists alongside injured serving personnel from the Coldstream Guards began excavations at Hougoumont Farm. Initially intended to run for a single season, the project proved so successful that it has returned to the site each summer since. A relatively small team of 25 participants in 2015 had, by 2018, expanded to nearly 150, more than 60 of whom were serving personnel and veterans. To date, the project has included participants from 11 countries. The project, supported by its key partners—Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, Glasgow University; L - P : Archaeology; ORBit team, Department of Soil Management, Ghent University; University College Roosevelt, Utrecht University; Service Public de Wallonie—will continue to work at the battlefield for at least another decade. It has also begun to develop other initiatives, including a Battlefields Uncovered Summer School at Utrecht University, along with creative writing and ethical metal-detecting courses.

AVAR began life as Operation Nightingale USA, inspired by the British initiative, before rebranding as AVAR in 2016. It was founded by Stephen Humphreys, a former US Air Force officer and history graduate. At the time of writing, Humphreys has recently completed a PhD in archaeology at Durham University. Following a small initial excavation in Yorkshire in summer 2016, a joint Operation Nightingale/Operation Nightingale USA project, and subsequent investigations of a US Air Force Second World War airfield in Norfolk, UK, and a French and Indian War fort in Pennsylvania, AVAR has developed a range of opportunities for participants. Working in conjunction with a number of partners has enabled AVAR to offer supported placements for veterans on excavations as varied as Beth She'arim in Israel (led by Haifa University) and a Shaker settlement in the State of New York (led by DigVentures). In 2019, AVAR is collaborating with the US National Park Service to undertake work at the battlefield of Saratoga, which is also in New York State (Stephen Humphreys pers. comm.). To date, approximately 75 veterans have participated in AVAR-supported projects, and the initiative continues to grow, securing funding from National Geographic in 2018.

In 2012, the University of Leicester established an initiative to support veterans who wished to take their interest in archaeology further, offering discounts on distance-learning fees for wounded service personnel interested in studying archaeology. While this was ground-breaking, distance-learning could not offer the same benefits in terms of rehabilitation and transition as an immersive student experience. In 2016, the University of Winchester offered its first fee-waiver studentships in archaeology, with Help for Heroes acting as gatekeeper and providing functional skills training and access courses. That year, four individuals, three of whom had archaeological experience via Breaking Ground Heritage or Waterloo Uncovered, enrolled at the university as full-time students. Their commitment to, and enthusiasm for, studying at this level has certainly overcome their own initial perception that higher education was out of their reach, and it is hoped that this initiative can be replicated at other universities.

Existing literature

The study of social and peer support as a psychosocial intervention in the treatment of PTSD (Burnell et al. Reference Burnell, Coleman and Hunt2006; Caddick et al. Reference Caddick, Phoenix and Smith2015a), and of the role of outdoor, physical pursuits in improving wellbeing among veterans (e.g. Caddick & Smith Reference Caddick and Smith2014; Caddick et al. Reference Caddick, Smith and Phoenix2015b; Poulton Reference Poulton2015; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Townsend and Gareth2016), are increasingly well established in the academic literature. The individual narratives presented by Burnell et al. (Reference Burnell, Coleman and Hunt2010), which span several decades, suggest that service personnel who witness psychologically traumatic events may seek to protect their family and friends by not discussing them; yet sharing experiences can support the processing of traumatic memories. Ideally, veterans would use naturally existing support networks, such as family and friends, to discuss these experiences, but reality is often different, and peer support as a more formalised intervention may need to be provided to support recovery. To date, the placement of veterans on archaeological projects to facilitate such support has been assessed only by military medical practitioners (Nimenko & Simpson Reference Nimenko and Simpson2014; Finnegan Reference Finnegan2016), and there is a scarcity of rigorously collected data. From an archaeological perspective, the ‘Invisible Diggers’ surveys of British professional archaeologists (Everill Reference Everill2012) highlight the key importance of camaraderie in the retention of staff, alongside enjoyment of the archaeological process and physical engagement with archaeological remains. Where archaeological fieldwork has been utilised as a general (i.e. for non-military individuals) therapeutic intervention (Sayer Reference Sayer2015), the scales used to measure outcomes appear to have been modified, meaning that they are no longer valid; consequently, conclusions are weakened.

The first Operation Nightingale excavations at Chisenbury Midden in 2011 focused on the placement of serving soldiers, with the support of professional archaeologists and the Rear Operations Group Civilian Medical Practitioner and Combat Medical Technician. The project was assessed for its potential contribution to the psychological decompression of the soldiers and its effectiveness in helping them return to operational roles (Nimenko & Simpson Reference Nimenko and Simpson2014). Although the project is not referred to as Operation Nightingale by Nimenko and Simpson, it is clear from media reports of the time that the initiative had adopted the name by this point. Nimenko and Simpson (Reference Nimenko and Simpson2014: 296) assessed 24 soldiers over the course of two, five-day excavations, seeking to measure any change in relation to depression, generalised anxiety disorder, impaired social functioning, alcohol-use disorders and PTSD. The authors conclude that, despite the small sample size and the lack of a longitudinal perspective, the results indicate a positive reaction to the experience, stating that “the exercise helped isolated and distressed battle-injured soldiers return to effective operational roles within the regiment” (Nimenko & Simpson Reference Nimenko and Simpson2014: 297).

Finnegan (Reference Finnegan2016) conducted semi-structured interviews with a convenience sample of 14 veterans participating in what are described, interchangeably, as ‘DAG’ or ‘Operation Nightingale’ excavations in April and August 2015. Finnegan reports improved self-esteem, confidence and motivation to seek help among his study group. In terms of the value of archaeology to this rehabilitation process, Finnegan (Reference Finnegan2016: 16) notes that “veterans may identify more strongly with outdoor activities that involve physical challenge, camaraderie and achievement of an objective”. He also makes an assertion, however, that there is a “close correlation between the skills required by the modern soldier and those of the professional archaeologist […including…] scrutiny of the ground” (Finnegan Reference Finnegan2016: 16). Undoubtedly, aspects of military training can help to prepare soldiers to carry out archaeological tasks—from specialist survey techniques, through logistics and site management, to the simple preparedness to work hard within a team in all weathers. The notion that military training prepares an individual to interpret an archaeological site, however, represents an over-simplification that has become entangled with the very concept of ‘rehabilitation archaeology’. The powers of observation that are so crucial to an archaeologist and potentially lifesaving to a soldier do not, in themselves, give insight into the story of an archaeological site's formation.

The limited extant literature does indicate a positive response to rehabilitation archaeology, and the need for more data is pressing. With 95 per cent of BGH beneficiaries, for example, disclosing mental health needs and reporting concerns including ‘self-imposed isolation’ and ‘burdensomeness’, it is clearly crucial to understand how and why involvement in ‘rehabilitation archaeology’ is helping to break down those negative feelings.

Methods

As part of a routine service evaluation, data were collected from 40 individuals before and after participation on three BGH projects over the summer of 2018. The participants were on-site for between seven days and three weeks. Three validated scales were used to measure dimensions of mental health, generating a robust psychological dataset. These measures were as follows: the Patient Health Questionnaire-8, to measure depression (PHQ-8; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Strine, Spitzer, Williams, Berry and Mondadori2008); the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) to measure anxiety; and the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS; Tennant et al. Reference Tennant, Hiller, Fishwick, Platt, Joseph, Weich, Parkinson, Secker and Stewart-Brown2007) to measure mental wellbeing.

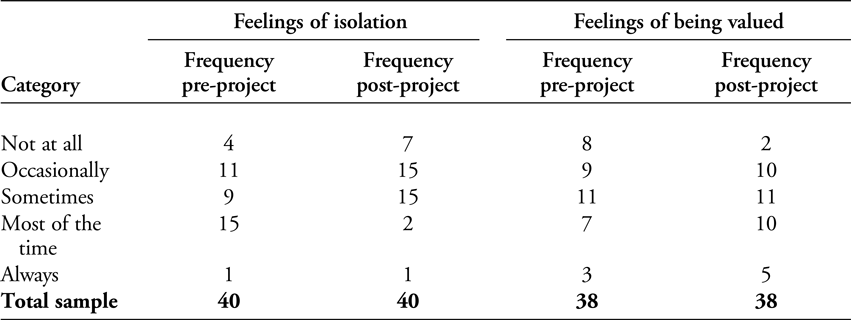

BGH developed and used its own simple scales to record self-declared feelings of isolation and value among participants, both before and after the projects. These scales are based on the work of Castro and Kintzle (Reference Castro and Kintzle2014) and their ‘interpersonal-psychological theory of suicides in the military community’, which suggests that the increasing suicide rate among US veterans results from the interplay between an acquired ability to enact lethal self-harm, an enhanced sense of not belonging—of isolation—and a strong perception that the individual is a burden to others. While it is not possible to prevent military veterans being able to enact lethal self-harm, interventions can and should focus on increasing a sense of belonging while reducing feelings of isolation and the perception of being a burden to others. Indeed, monitoring these feelings is an important aspect of risk assessment. Even though these measures are not validated, they do provide further contextual information.

Results

Depression: PHQ-8

The PHQ-8 measures depressive symptom severity and comprises eight items scored on a scale of 0–3, with total scores of 0–24. It provides a classification of depressive symptoms from none to minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), to severe (20–24). Before participating in a project, 22 individuals reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms, while 14 scored within the none-to-minimal and mild categories (Table 1). Post-project, the number of participants who scored in moderate to severe categories fell to 12, with 24 scoring within the none-to-minimal and mild categories, demonstrating a reduction in the severity of depressive symptoms.

Table 1. Pre- and post-project category frequencies for PHQ-8.

A paired samples t-test to compare mean depression symptom severity scores pre- and post-project shows a statistically significant improvement in the scores recorded before (M = 12.3, SD = 6.70) and after participation (M = 8.38, SD = 5.64); t(35) = −3.63, p<.001.

Anxiety: GAD-7

The GAD-7 measures anxiety symptom severity and comprises seven items. These items are scored on a scale of 0–3, with total scores of 0–21. It provides a classification of anxiety symptoms from none to minimal (0–4), to mild (5–9), moderate (10–14) and severe (15–21). Table 2 shows that, pre-project, 22 participants reported moderate to severe anxiety symptoms, while 14 scored within the none-to-minimal and mild categories. Post-project, only 10 scored within moderate to severe symptoms, and 26 scored within the none-to-minimal to mild categories, thus demonstrating a decrease in the severity of anxiety symptoms.

Table 2. Pre- and post-project category frequencies for GAD-7.

A paired samples t-test to compare mean anxiety symptom severity scores shows a significant improvement in the scores from pre- (M = 11.14, SD = 5.10) to post-project (M = 7.02, SD = 4.90); t(35) = −5.58, p<.001.

Mental wellbeing (WEMWBS)

Wellbeing is at the centre of what BGH seeks to promote. Without improvements in wellbeing, it becomes harder to reduce levels of anxiety and depression. The WEMWBS is measured on a scale of 1–5 over 14 items, giving a minimum score of 14 and maximum of 70; a higher score indicates higher mental wellbeing. A paired samples t-test was conducted to compare mean WEMWBS scores pre- and post-project. There was a significant improvement in the mean scores (M) pre- (M = 37.56, SD = 9.74) to post-project (M = 48.44, SD = 10.66); t(35) = −3.63, p<.001. Notably, the mean post score is approaching the mean score for the general population (M = 51).

Findings from BGH-developed measures

BGH project participants were assessed for feelings of isolation and their sense of value as part of a questionnaire to assess changes in overall wellbeing, confidence and employability prospects. Isolation is scored on a five-point scale, where 0 = not at all isolated, and 4 = always isolated; sense of value is scored on a five-point scale, where 0 = always valued and 4 = not at all valued. Table 3 shows a general trend towards a decrease in feelings of isolation from 16 participants pre-project, to only three post-project. Sense of value had also improved following the projects, with reports of feeling valued most or all of the time rising from 10 to 15 participants.

Table 3. Pre- and post-project category frequencies for isolation and sense of value.

Discussion

The results demonstrate decreases in the severity of the symptoms of depression and anxiety, and of feelings of isolation, along with an increase in mental wellbeing and in sense of value. Due to the lack of a control group (i.e. similar individuals who do not join BGH projects), it is currently unknown whether these changes are associated with BGH, archaeology, social support opportunities or natural improvement over time. These changes, however, resonate with the field observations of the BGH Director (co-author of the present article) and enable reflection on the relationship between the results and these personal observations.

Depression seems to be very fluid in the wounded, injured and sick veteran population. The majority of these individuals experience depression, along with periods of self-imposed isolation due to flare-ups in depression, which affect other areas such as self-worth and perceived value. This may explain why both symptoms of depression and feelings of isolation lessen, and perceived value increases over the course of the project. While BGH projects seem to lower depression, there are, of course, external factors that may increase it, such as family problems, increased pain and employment concerns. Anxiety can create barriers to those wishing to join BGH. Months can be invested in individuals by the project in order to reduce anxiety sufficiently to even visit a site, yet, after that initial visit, anxiety seems to dissipate.

It is important to note that the post-project data were collected on the final day of a project, by which time participants reported feeling low and anxious, faced with their impending return to ‘normal’ life and leaving the supportive environment of the project. It is salient, therefore, that reductions in depression and anxiety are seen at all.

While positive change seems to take place during time with BGH, there are risk factors for participants, such as the re-occurrence of dependency issues or the triggering of traumatic memories; these need to be fully understood and, where possible mitigated to ensure that harmful situations are avoided. Alongside staff equipped with Mental Health First Aid training, the presence of a Psychological Wellbeing Lead (recognised by the Health and Care Professions Council) might make the difference between improving participants’ wellbeing, or participants leaving the project having suffered setbacks in their recovery. At Bullecourt, this proved a vital element in the success of the project. Anxiety attacks are a common occurrence on projects, and are recognised and handled through careful management by the BGH welfare team, as well as through peer support offered by other participants.

When leaving the project, participant testimonials (not to be mistaken for qualitative data as they lack the rigour required of research) are collected. These too reflect the changes seen in the outcome measures. Prior feelings of isolation seem to have lessened. One participant, for example, states that “having isolated myself over the last few years … I am a step closer to joining the world again”. When asked why feelings of isolation may have reduced, the most common response is that participants feel like they are back within a familiar environment, alongside others who understand them.

A sense of value is central to military service, and underpins section, troop, company and unit/regiment cohesion. Leaving the services as a respected combatant or technician to become lost in a civilian world can have a profound effect. Participants on BGH projects seem to feel that, due to injuries, poor mental health, addiction or lack of employment, they are not valued by society. Yet this outlook changes during participation in a project. This is unlikely to relate to feeling valued as archaeological practitioners, given the limited experience of most participants. Rather, it may reflect a sense of value that comes from being part of a cohesive team, contributing to over-arching project goals, or supporting those around them. One participant's testimonial, for example, states “the pride I now feel having achieved this feat with my new friends has given me greater confidence and belief in myself”.

It seems probable that the ‘community group’ is a key element here. Individuals have shared experiences of military life, from a distinctive vocabulary to banter and black humour. As one project participant indicates, “it allows me to switch off from my own head, to talk to others going through similar experiences and generally be what I consider to be normal again”. The tribal nature and alpha-based social structures of the military world carry with them their own risks, which might serve to exclude individuals or ‘outside’ groups. From personal observation, however, the mixed military and archaeological community participating on BGH projects seems to be inclusive and equal, regardless of time served, rank, arm of the service or disability. A recurring phrase, which underscores both the great strength of the project community and efficacy of the peer support it engenders, is “that was the first time I have told anyone that”.

Longitudinal data and investigation of clinically significant change are still required. Despite this, the data presented here show evidence of a significant relationship between participation in archaeological fieldwork and improved wellbeing among veterans. Future research will utilise rigorous qualitative methods to explore the ways in which BGH affects those involved, focusing particularly on the role of peer support and determining the causal nature of this relationship.

Conclusion

For nearly a decade, claims have been made that participation in archaeological fieldwork can improve the wellbeing of military veterans. Most of the evidence offered in support of these claims, however, has been anecdotal in nature and susceptible to misuse in support of a media-friendly good-news story. There is a clear need for the disciplines of archaeology and psychology to engage critically with these initiatives, to assess rigorously the benefits and potential risks, both to those participating and to the fragile historic environment, and to inform best practice. This article represents the first output of a new area of interdisciplinary study, bridging archaeology and psychology, which could, for simplicity, be referred to as ‘rehabilitation archaeology’ or ‘wellbeing archaeology’. The implications, however, are even more significant. The demonstrable capacity for archaeological fieldwork to improve the wellbeing of participants need not be limited to specific groups, and might even explain its wider appeal. Far more data are required to understand fully the mechanisms at play, and this is particularly true of the effect on those with mental health issues. The veteran-led initiatives outlined in this article also recognise the need to establish a rigorous dataset that can help protect the vulnerable and ensure the best possible outcomes.

In 2018, key stakeholders from organisations including the Ministry of Defence, Defence Archaeology Group, the National Trust, Breaking Ground Heritage, the National Health Service, the Council for British Archaeology, Step Together, the British Archaeological Jobs Resource, the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists and the Universities of Cardiff, Solent and Winchester met to discuss best-practice guidelines for veteran-focused archaeology. Clearly, this is a welcome and important step towards formalising the requirements for appropriate, qualified, mental health support to be put in place, and producing a list of potential risk factors to be addressed, alongside strategies for maximising positive outcomes. In order to ensure the most effective wellbeing uplift for participants, however, we still need to understand better how, why and whom archaeology can help, and for how long. The results presented here are, to date, the largest published study of its kind. Yet this is simply the first step on which to build longitudinal and qualitative approaches. Measurable improvements in wellbeing, including reduction in the occurrence of anxiety, depression and isolation, and a greater sense of being valued after project participation, are particularly noteworthy. Future data collection and analysis will further illuminate the longevity of these improvements following participation, as well as helping to identify which sites and projects are the most effective.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all those who work to support the improved wellbeing of serving personnel and veterans through archaeology. Most importantly, however, we wish to thank the members of Breaking Ground Heritage themselves for the enthusiasm, banter and hard work they bring to the projects. We offer our sincerest gratitude to all personnel and veterans for their service.