Introduction

Terrestrial vascular plants play a key role in Earth’s long-term geological processes, influencing and contributing to, for example, carbon cycling, chemical weathering and soil formation. These plants inhabit the subaerial and subterranean environment simultaneously, where they continuously transport elements from the shallow soil environment to above-ground organic structures. Concomitant with this life process is the sequestration of atmospheric CO2 into the organic architecture. Plants contain a wide range of macroelements translocated from the soil environment to their above-ground structures, most notably Na, K, Ca, Si, S, P and Cl. These elements can reach concentrations of 1000 to 10,000 ppm levels or higher in the dried plant material (Calva-Vázquez et al., Reference Calva-Vázquez, Razo-Angel, Rodríguez-Fernández and J.L2006; Garvie, Reference L.A.J2016; Ramírez et al., Reference Ramírez, González-Rodríguez, Ramírez-Orduña, Cerrillo-Soto and Juárez-Reyes2006; Ramírez-Orduña et al., Reference Ramírez-Orduña, Ramírez, González-Rodríguez and G.F.W2005; Zárubová et al., Reference Zárubová, Hejcman, Vondráčková, Mrnka, Száková and Tlustoš2015). Calcium occupies a special role in plants as it concentrates in the biominerals weddellite and whewellite, which can themselves concentrate to high levels. For example, a large saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea) contains on the order of 1x105 g of the Ca oxalate weddellite (Garvie, Reference L.A.J2006): the Ca is translocated from the soil in water taken up by the roots of the rhizosphere (White and Broadley, Reference White and M.R2003). The fate of the macroelements in plants can depend on the manner of their demise. During aerobic decay, plant carbon is largely emitted back into the atmosphere because of decomposition by bacteria and fungi. Whereas the fate of the macroelements during aerobic decay is less well understood, they are probably solubilised and returned to the soil. In contrast, combustion converts many of a plant’s macroelements into an inorganic ash that accumulates on the soil surface and is emitted into the atmosphere in smoke.

Wildfire is a geological process that influences widespread surficial mineral formation, erosion patterns, sediment transport, soil formation, and the shaping of vegetation patterns over geological time periods (Galloway and Lindström, Reference Galloway and Lindström2023; Rengers and McGuire, Reference Rengers and L.A2021). The immediate aftermath of a wildfire is charred plants and an inorganic ash residue. This residue is primarily inorganic (e.g. Anca-Couce et al., Reference Anca-Couce, Zobel, Berger and Behrend2012; Bodí et al., 2014; Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Veras and Carvalho2002; Daouk et al., Reference Daouk, Van de Steene, Paviet and Salvador2015; Garvie, Reference L.A.J2016), produced by a self-sustaining smouldering process, a form of non-flaming combustion. Smouldering is a complex physico-chemical process that generates a thermal wave that involves dehydration (<100°C), oxidation and pyrolysis (<400°C), leading to the formation of char (Anca-Couce et al., Reference Anca-Couce, Zobel, Berger and Behrend2012; Ohlemiller, Reference T.J1985). In most self-sustaining smouldering reactions, char oxidation serves as the primary heat source that drives the lower-temperature dehydration, oxidation and pyrolysis of wood. Char oxidation temperatures typically range from 400 to 700°C, with the formation of an inorganic residue of ash.

Plant ash formed by wildfires contains a wide range of minerals and bio-pyrophases, e.g. Vassilev et al. (Reference Vassilev, Baxter, Andersen and Vassileva2013). The mineralogy of ash is influenced by the concentration of plant macroelements, most commonly Na, K, Mg, Ca, Si, S and Cl, along with factors including oxygen availability, combustion temperature, type of fuel, and environmental conditions (Garvie, Reference L.A.J2016; Liodakis et al., Reference Liodakis, Katsigiannis and Kakali2005; Yusiharni and Gilkes, Reference Yusiharni and Gilkes2012). For instance, the wood of the desert tree Parkinsonia microphylla contains significant levels of K, Ca and Mg, resulting in ash dominated by fairchildite (K2Ca(CO3)2) and its dimorph bütschliite, calcite (CaCO3), lime (CaO), and periclase (MgO), with trace amounts of K-bearing salts (Garvie, Reference L.A.J2016). In the same region, the wood of the desert tree Prosopis juliflora is rich in K, Ca and Cl, with ash dominated by sylvite (KCl) and calcite (Garvie et al., Reference Garvie, Wilkens, Groy and Glaeser2015). Similarly, ash from Australian native plants contains a variety of minerals, including calcite, fairchildite, nesquehonite (MgCO3·3H2O), and sylvite (Yusiharni and Gilkes, Reference Yusiharni and Gilkes2012). The mineralogy of the ash is also influenced by burn conditions. For example, Liodakis et al. (Reference Liodakis, Katsigiannis and Kakali2005) examined the ash of six Greek forest species at combustion temperatures of 600, 800 and 1000°C. At 1000°C, the ash is dominated by simple oxides, carbonates and sulfates of Ca, Mg and K, such as lime, periclase, K2SO4, and K2CO3. At 600°C, the ash contained these same phases together with calcite, (Ca,Mg)CO3, and Ca(OH)2, and the double carbonates fairchildite and K2Ca(CO3)2. These studies illustrate the mineralogical diversity of plant ash.

Three K–Ca carbonates are expected at surficial pressures and below ~700°C, i.e. bütschliite K2Ca(CO3)2 and its dimorph fairchildite, and K2Ca2(CO3)3 (Arceo and Glasser, Reference Arceo and Glasser1995; Arefiev et al., Reference Arefiev, Podborodnikov, Shatskiy and Litasov2019a; Arefiev et al., Reference Arefiev, Shatskiy, Podborodnikov, Rashchenko, Chanyshev and Litasov2019b; Winbo et al., Reference Winbo, Bostrom and Gobbels1997). Fairchildite is widely reported in plant ash (Englis and Day, Reference Englis and W.N1929; Garvie, Reference L.A.J2016; Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Raven and Field2004; Milton and Axelrod, Reference Milton and Axelrod1947), with masses of a “hundred pounds or more” (Milton and Axelrod, Reference Milton and Axelrod1947). These large masses form clinkers within burning trees through a process called pyro-biomineralisation (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Shakesby, Doerr, Blake, Wallbrink, Hart and Roach2003). Clinkers from several locations have similar compositions, being dominated by fairchildite (Milton and Axelrod, Reference Milton and Axelrod1947) and calcite (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Raven and Field2004). Though less widely described, bütschliite is also found in ash (Dawson and Sabina, Reference Dawson and Sabina1957; Mandarino and Harris, Reference Mandarino and D.C1965). The experiments of (Pabst, Reference Pabst1974) show the formation of bütschliite as a reaction product of heating K2CO3 and CaCO3 at 420°C and 505°C. No reaction took place at 340°C, whereas fairchildite formed at 585°C. Depending on temperature and composition in the K2CO3–CaCO3 system, experiments at room pressure produce various proportions of K2CO3, calcite, fairchildite, bütschliite, and the double carbonate K2Ca2(CO3)3 (Arceo and Glasser, Reference Arceo and Glasser1995; Arefiev et al., Reference Arefiev, Podborodnikov, Shatskiy and Litasov2019a; Kröger et al., Reference Kröger, Illner and Graeser1943). The double carbonate K2Ca2(CO3)3 crystallises in space group R3 with unit cell dimensions a = 13.010(4) Å, c = 8.615(3) Å, V = 1262.9(9) Å3, Z = 6 (Winbo et al., Reference Winbo, Bostrom and Gobbels1997). To date, K2Ca2(CO3)3 has not been described as a mineral, though Winbo et al. (Reference Winbo, Bostrom and Gobbels1997) suggested that it “should occur in combustion products [of plant materials]”.

Here is described the double carbonate, K2Ca2(CO3)3, a new ash bio-pyrophase that occurs in the ash of the desert spoon plant (Dasylirion wheeleri) from the Sonoran Desert. Electron microprobe analysis, powder X-ray diffraction Rietveld refinement and Raman spectroscopy confirm that this phase matches synthetic rhombohedral (R3) K₂Ca₂(CO₃)₃. Note, though the description of the rhombohedral K₂Ca₂(CO₃)₃ was submitted to the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association as a new mineral (IMA2022-037a), the proposal was rejected. The rejection was based on the fact that a human cause for the ignition of the 180,757-acre Telegraph wildfire could not be unequivocally ruled out, and there is no consensus as to whether ‘wildfire’ constitutes a geological process. Because of this lack of consensus, the mineral status of inorganic materials formed by wildfires acting on plant matter remains uncertain.

Materials and methods

Field ash

Ash from Dasylirion wheeleri plants was collected at 33°15’7.62” N, 111°7’0.40” W, near the small town of Superior, Arizona, USA, following the Telegraph Fire in June 2021. Samples were taken from eight burnt D. wheeleri plants and stored in a dry nitrogen atmosphere to prevent moisture exposure. Many minerals in the ash, including K2Ca2(CO3)3, are sensitive to moisture. The samples studied here were collected within a few days of having formed during the Telegraph Fire. In addition, all sample preparation, such as grinding and polishing, required the use of non-polar solvents, as well as storage of samples in a dry atmosphere.

Powder X-ray diffraction and Rietveld refinement

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were acquired with a Rigaku MiniFlex 600 diffractometer. This diffractometer is operated with CuKα radiation and is equipped with an automatic divergence slit system and post-diffraction graphite monochromator. Data were acquired from 2 to 65°2θ at 0.02° steps and 30 s/step. The diffractometer was aligned with the Si powder standard (NBS 6d), and the experimental pattern was further corrected by adding the NDS Si powder as an internal standard. XRD samples were prepared from ~50 mg fragments of ash. Fragments were crushed and lightly ground to a fine powder and mixed with a few millilitres of toluene. The resulting slurry was pipetted and spread into a thin, smooth film on a low-background, single-crystal, quartz plate. This slurry was dried rapidly (~5 s) under flowing warm air, forming a thin film on the quartz plate.

Refinement of the powder XRD pattern was undertaken with Profex 5.3, which is a graphical user interface to the Rietveld refinement program BGMN (Döbelin and Kleeberg, Reference Döbelin and Kleeberg2015). The refinement pattern was acquired from 10 to 75°2θ at 0.01° steps and 25 s/step. The following structure files were used for the refinement: fairchildite (Pertlik, Reference Pertlik1981); K2Ca2(CO3)3 (Winbo et al., Reference Winbo, Bostrom and Gobbels1997); calcite (Sitepu, Reference Sitepu2009); arcanite (Ojima et al., Reference Ojima, Nishihata and Sawada1995); sylvite (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Verma, Cranswick, Jones, Clark and Buhre2004); hydroxylapatite (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Elliott and Dowker1999); and periclase (Hazen, Reference R.M1976).

Elemental analysis and imaging

Fragments of the ash were embedded in epoxy. The 1”-round sections were dry cut and dry ground down to 1200 grit and then polished for ~20 s with a 1-micron diamond suspended in mineral oil on lapping felt. The sample was then washed with toluene. Quantitative elemental microanalyses using wavelength dispersive spectroscopy (WDS) were acquired at the University of Arizona’s Michael J. Drake Electron Microprobe Lab with a CAMECA SX100 electron microprobe (15 kV and 6 nA, 10 mm beam). Ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 damages rapidly, even with a 10 µm beam. This damage was mitigated during the ~3 minute WDS acquisition by continuously moving the sample under the beam during the analysis – this movement was possible by simultaneously observing the crystal with an attached optical microscope while acquiring the WDS data. Element-distribution maps were acquired with the Zeiss Auriga high-resolution field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM) equipped with an Oxford X-Max energy dispersive X-ray Spectrometer (EDS) at the John M. Cowley Center for High Resolution Electron Microscopy at Arizona State University.

Raman microscopy

Raman spectra were acquired with the XploRA PLUS microRaman spectrometer microscope with a 532 nm solid-state laser using a Plan N100x objective. Ash was lightly ground in toluene, and a few ml was dried on a polished stainless steel planchette. The spectra were recorded with a beam power of 17 mW on the sample. Counting times ranged from 50 to 500 s for the 10–2000 cm–1 spectral range. Spectral resolution of ~1 cm–1 was achieved using an 1800 mm–1 grating.

Study site and plant

On June 4th, 2021, the Telegraph wildfire ignited near Superior, Arizona, burning 180,757 acres of native xeric wildlands. The cause of the Telegraph wildfire remains unproven; while human activity is a possibility, a natural origin cannot be ruled out. The fire swept through the Arizona Upland subdivision of the Sonoran Desert, the highest and coolest part of the desert, dominated by the ‘saguaro-paloverde forest’ plant community. Common in the burn area is Dasylirion wheeleri (Walker, Reference Walker2020), also known as desert spoon or sotol, which is a medium-sized evergreen xeric monocot shrub with an unbranched trunk, common in the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts.

D. wheeleri is a monocotyledon with a trunk anatomically similar to other monocots, such as palms (Fathi et al., Reference Fathi, Frühwald and Koch2014; Parthsarathy and Klotz, Reference Parthsarathy and L.H1976). Its trunk consists of a fibrous network of tangled primary vascular bundles embedded in lighter-coloured parenchymatous ground tissue (Fig. 1A). Powder XRD analysis of these vascular bundles shows reflections from whewellite, set against a broad background from scattering by the organic woody material. When a piece of trunk dominated by vascular bundles was submerged in sodium hypochlorite solution, the organic matter dissolved, leaving behind a white sediment composed of euhedral raphids (Fig. 1B). The powder XRD pattern of this sediment matches whewellite.

Figure 1. (A) Reflected-light optical photograph of a polished section of unburnt Dasylirion stem wood. (B) Whewellite crystals extracted from the stem wood viewed under cross-polarised light. (C) Calcium and (D) potassium EDS element-distribution maps showing the distribution of whewellite (pink) crystals in the wood.

The EDS spectroscopy of the vascular bundles shows prominent peaks for K and Cl, along with less intense peaks for Ca, Mg, S, Na, Si and P (Supplementary Fig. S1). The qualitative EDS analysis suggests the following (wt.% and at.%) averaged over a 1 × 0.75 mm area of the wood: 2 and 0.6 K; 1 and 0.37 Cl; 0.6 and 0.2 Ca; 0.3 and 0.12 S; and 0.1 and 0.05 Mg. Element-distribution imaging using EDS shows that whewellite is present within the parenchymatous tissue surrounding the vascular bundles (Fig. 1C), whereas the other macroelements, such as K (Fig. 1D), are more uniformly distributed throughout the organic material.

Ash results

The D. wheeleri ash logs consist of friable, decimetre-sized, porous, white to grey sintered masses (Fig. 2). Photographs of the char from the partially burnt trunk show interconnected tangles of the vascular bundles with an abundance of 200 µm long colourless, white crystals (Fig. S2). Powder XRD patterns of the char show Bragg reflections for calcite and minor whewellite sitting on the broad scattering maximum from the charred organic material. Char oxidation caused by the smouldering leaves sintered masses of inorganic ash that pseudomorphically preserves the fibrous structure of the original plant (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Photograph of a burnt Dasylirion wheeleri plant following the wildfire combustion. (A) The recumbent trunk has smouldered, leaving large chunks of white inorganic ash (red arrows). (B) Close-up photo of an ash chunk that preserves the fibrous nature of the plant.

Powder XRD patterns of the ash logs show reflections that are dominated by reflections for K2Ca2(CO3)3 (Winbo et al., Reference Winbo, Bostrom and Gobbels1997) and fairchildite (Fig. S3), lesser sylvite, calcite and arcanite, and minor hydroxylapatite and periclase. Multiple samples and areas of ash were sampled by XRD. Single-crystal X-ray studies could not be undertaken for the ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 because of its intimate association with the other minerals and because of the polycrystalline nature of the grains. The latter was confirmed by viewing the grains under crossed-polarised transmitted light. The structural identity of K2Ca2(CO3)3 in the ash was determined by Rietveld refinement (Fig. 3). The powder XRD pattern that showed the ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 phase was refined with a final χ2 = 1.58 (Rp=3.49%, Rwp= 3.97%, Rexp= 3.16%, GoF = 1.18, Durbin-Watson d = 0.62), for 6501 measured points, 465 peaks and 368 parameters (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary CIF and checkcif files). The K2Ca2(CO3)3 is associated intimately with the other minerals, and so all minerals in the ash were refined (Table 1). The ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 is trigonal, R3 (#146), and Rietveld refinement gives a = 13.0564(2) Å, c = 8.6369(2) Å, V = 1275.07(6) Å3 and Z = 6.

Figure 3. Rietveld refinement of the Dasylirion wheeleri ash showing the observed pattern (black), calculated profile (red), refined pattern for the ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 (tan), and the difference pattern (grey). The calculated pattern refines with 56.1% K2Ca2(CO3)3 + 17.6% sylvite, + 13.5% fairchildite, 7.5% calcite, 2.8% arcanite, 1.8% hydroxylapatite and 0.7% periclase. The patterns are shifted along the y-axis for clarity.

Table 1. Cell parameters and phase fractions determined by Rietveld refinement for the minerals in the wildfire ash

The structure of K2Ca2(CO3)3 comprises two crystallographically distinct carbonate ions, positioned in columns around the three-fold axes, where 25% of the cations (one Ca2+ and one K+) are located. The remaining cations are situated in general positions between the carbonate columns. There are two distinct cation sites: Ca(1) and K(1) are positioned on a three-fold axis in the special position ‘a’ , while Ca(2) and K(2) occupy general positions between the three-fold axes. Each O atom is shared between a C atom and either three or four cations. Tables S2a to S2f show selected interatomic distances and angles. In many common trigonal and orthorhombic carbonates, the carbonate groups are orientated parallel in planes, resulting in layered structures. In contrast, in K₂Ca₂(CO₃)₃, the carbonate groups are inclined relative to the principal axes. The structure of synthetic K2Ca2(CO3)3 is described in detail in Winbo et al. (Reference Winbo, Bostrom and Gobbels1997).

In ash containing a range of minerals, the ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 is most easily recognised in the powder XRD patterns by the two reflections between 12 and 14°2θ (CuKα) at 6.8639 (101) and 6.5288 (110, 1![]() $\bar 2$0) Å (Fig. S4). The 002 reflection for fairchildite occurs between the two ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 reflections forming a triplet. As this region of the diffraction pattern contains relatively few reflections from the other ash components, the presence of K2Ca2(CO3)3 and fairchildite can be readily determined in complex mineral mixtures.

$\bar 2$0) Å (Fig. S4). The 002 reflection for fairchildite occurs between the two ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 reflections forming a triplet. As this region of the diffraction pattern contains relatively few reflections from the other ash components, the presence of K2Ca2(CO3)3 and fairchildite can be readily determined in complex mineral mixtures.

Back-scattered electron (BSE) SEM images (Fig. 4) show aggregates with a branching architecture composed of intimately associated K2Ca2(CO3)3, fairchildite, calcite, sylvite and minor hydroxyapatite. K2Ca2(CO3)3 occurs as anhedral grains to 200 µm across in the aggregates, though polarised-light microscopy shows these grains to be polycrystalline at the micron scale. The ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 is colourless and transparent, with a vitreous lustre: no fluorescence was noted at either short- or long-wave UV. Aggregates are brittle and give a white streak.

Figure 4. BSE-SEM image of K2Ca2(CO3)3-bearing ash (grey) and coloured EDS element-distribution maps for K, Ca, Cl, S and P. The Cl map shows the location of sylvite, the S map for arcanite, and the P map the location of hydroxylapatite. Calcite is visible as the brighter signal in the Ca map, which is dark in the K map. Most of the green signal in the Ca map corresponds to ash K2Ca2(CO3)3, and small regions of fairchildite show a less intense green signal.

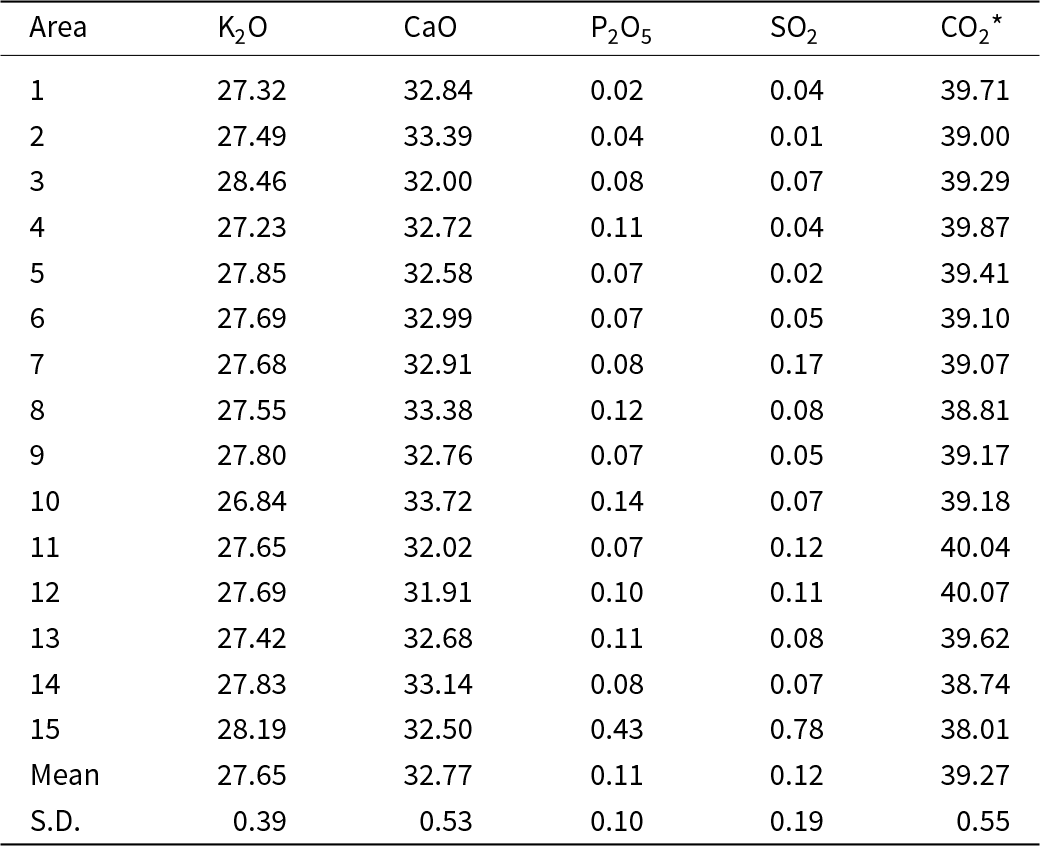

Electron microprobe data were acquired by WDS (Table 2). The composition of the ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 determined by WDS analysis is (wt.%, n = 15) K2O 27.65±0.39 and CaO 32.77±0.53, with CO2 determined by stoichiometry of 39.27 wt.%. The empirical formula (based on 16 atoms pfu) and normalised to 9 oxygen atoms is K2.01Ca2.00C3.00O9. The ideal formula is K2Ca2(CO3)3, which requires (wt.%) K2O 27.84, CaO 33.14, CO2 39.02. The elements Na, Si, Mg, Al, Fe, Mn, P and S were near or below the detection limit and totalled <0.16 wt.%, so they were not included in the table or empirical formula. Only P and S were regularly above detection limits with average P2O5 and SO2 at 0.11 and 0.12 wt.%, respectively. The intimate association of ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 with fairchildite and calcite prevented direct determination of the CO2 content. The CO2 concentration was calculated in the stoichiometry.

Table 2. Composition data (in wt.%) for the ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 determined by WDS

Notes: CO2* – determined by the stoichiometry. S.D. – standard deviation. Note, the minor P and S probably derive from the hydroxylapatite and arcanite, respectively, which are ubiquitous in the grains (see Fig. 4).

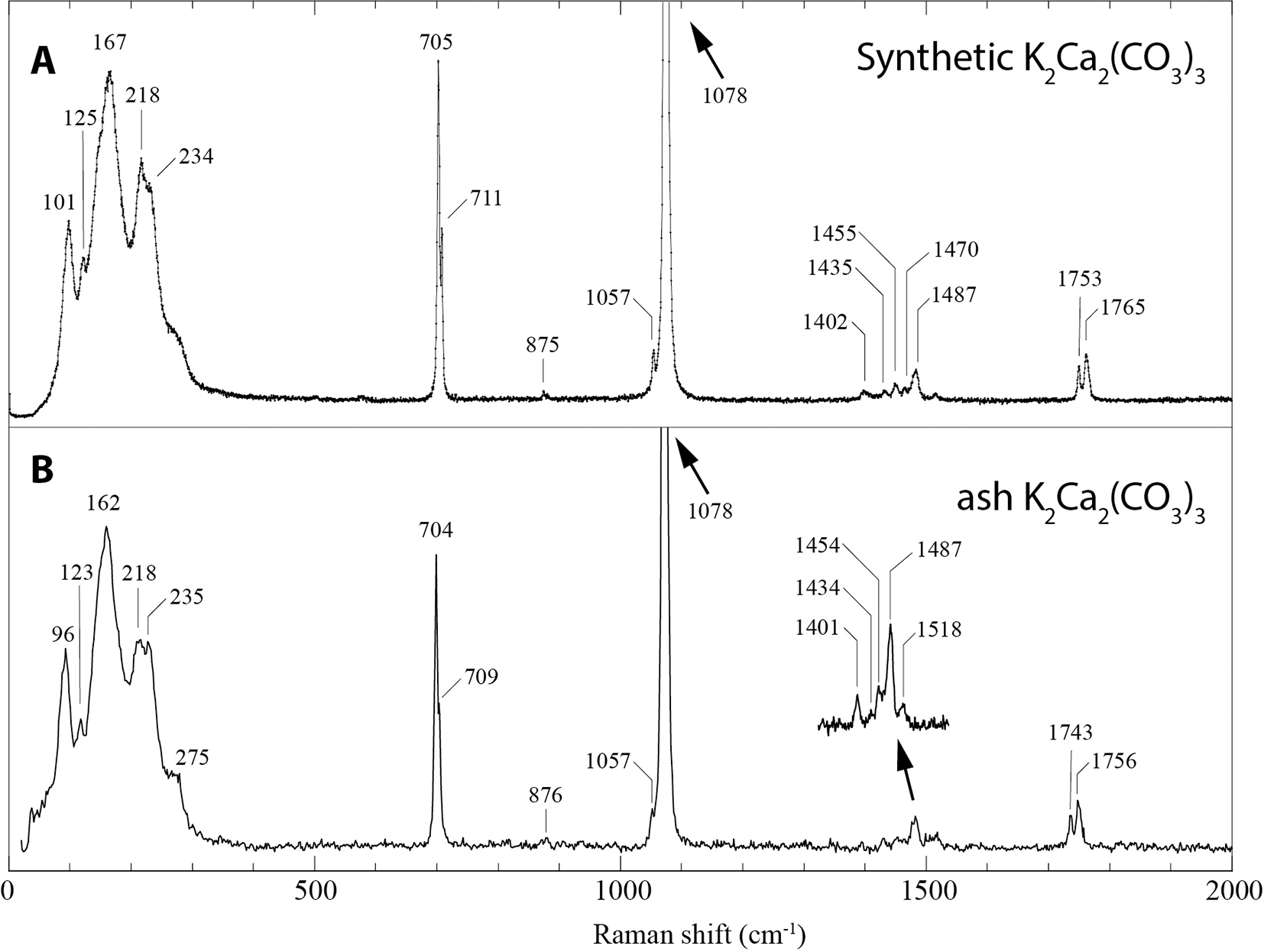

The Raman spectrum of ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 (Fig. 5) matches that of synthetic K2Ca2(CO3)3 (Arefiev et al., Reference Arefiev, Podborodnikov, Shatskiy and Litasov2019a; Arefiev et al., Reference Arefiev, Shatskiy, Podborodnikov, Rashchenko, Chanyshev and Litasov2019b). The spectrum is dominated by two intense but overlapping bands in the region of symmetric stretching C-O vibrations ν1(CO32–) at 1078 and 1076 cm–1, and low-frequency bands ascribed to lattice vibrations. This double band dominates the intensity of the Raman spectrum, with the next most intense band at 162 cm–1 only 7% of its intensity. The region attributed to ν4(CO32–) asymmetric in-plane bending shows two sharp resolved bands at 704 and 709 cm–1. In addition to these intense vibrations from the CO32– groups, the following bands and assignments are present: weak band at 876 cm–1 corresponding to the symmetric out-of-plane mode ν2(CO32–); several bands between 1400 and 1500 cm–1 corresponding to the asymmetric stretching ν3(CO32–) vibrations; and two bands at 1743 and 1756 cm–1 corresponding to the combination vibrations ν1 + ν4.

Figure 5. Raman spectrum of (A) synthetic K2Ca2(CO3)3 (from Arefiev et al., Reference Arefiev, Shatskiy, Podborodnikov, Rashchenko, Chanyshev and Litasov2019b) compared with (B) ash K2Ca2(CO3)3. The spectrum was acquired in high-resolution mode (slit = 50 μm, pinhole = 100 μm and 500 s acquisition), except for the inset region between 1400 to 1500 cm–1 which was acquired with a slit = 100 μm, pinhole = 500 μm and ten 50 s spectra summed.

The ash minerals, including ash K2Ca2(CO3)3, are stable in the air under normal laboratory low-humidity conditions. However, washing the ash with water leaves a residue of calcite, hydroxylapatite and minor periclase.

Discussion

Within the temperature range produced during smouldering, i.e. 400 to 700°C and at atmospheric pressure, the K2CO3–CaCO3 phase diagram contains several K, Ca and K–Ca carbonates, with compositions dependent on the K to Ca ratio and temperature (Arefiev et al., Reference Arefiev, Podborodnikov, Shatskiy and Litasov2019a; Reference Arefiev, Shatskiy, Podborodnikov, Rashchenko, Chanyshev and Litasov2019b). Above 50 mol.% K2CO3 and below 520°C, the system is dominated by K2CO3 and bütschliite, and above this temperature K2CO3 and fairchildite. Bütschliite and K2Ca2(CO3)3 form below 518°C and between 50 and 33 mol.% K2CO3, whereas K2Ca2(CO3)3 and fairchildite form between 518°C and 780°C. In addition, the presence and stability of K2Ca2(CO3)3 and fairchildite in biomass fuels are governed by the temperature and pCO2 of the combustion atmosphere (Winbo et al., Reference Winbo, Rosén and Heim1998). The thermoanalytical study of K2Ca2(CO3)3 suggests that it can form during the combustion of biomass, where pCO2 = 0.10 to 0.15 bar, and between 530–790°C (Winbo et al., Reference Winbo, Rosén and Heim1998). The published experimental data on the K₂CO₃–CaCO₃ system, together with the observed mineralogy, constrain the smouldering temperatures and are consistent with the following processes during ash formation in D. wheeleri: (1) Below ~400°C, dehydration, oxidation and pyrolysis of the wood produce char enriched in minor elements (detected by EDS), most notably K, Ca, Mg, Si, P, S and Cl. During this stage, the abundant whewellite concentrates as the wood dehydrates and decreases in volume. (2) Calcite is formed from whewellite above 480°C in the char as a result of the smouldering of the wood. Calcite is absent in uncharred wood and forms from the decomposition of whewellite, which occurs near 479°C through a series of intermediate Ca oxalate compounds (Frost and Weier, Reference Frost and M.L2004; Izatulina et al., Reference Izatulina, Gurzhiy, Krzhizhanovskaya, Kuz’mina, Leoni and Frank-Kamenetskaya2018). (3) There is combustion and formation of K2CO3 from K-rich char during oxidation above ~500°C. (4) The macroelements K-Ca-Mg-Cl are concentrated in the wood during combustion above 518°C, together with the reaction of K2CO3 with calcite to form K2Ca2(CO3)3 and K2Ca(CO3)2 (fairchildite).

Different areas of the ash log show variable amounts of ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 + fairchildite + calcite + sylvite. Some areas are dominated by calcite, sylvite and ash K2Ca2(CO3)3. It is speculated that during char oxidation, K2CO3 is formed, which then reacts with the abundant calcite, forming the K–Ca double carbonates. The presence of ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 + fairchildite, instead of ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 + bütschliite, is consistent with char oxidation above 520°C (Arefiev et al., Reference Arefiev, Podborodnikov, Shatskiy and Litasov2019a). The cation and Cl ratios in the wood give insights into the final minerals that form in the ash. For example, the following atom% for the general areal of the wood (Fig. S1) gives 0.6 K, 0.37 Cl, 0.2 Ca, 0.12 S and 0.05 Mg averaged over a 1 × 0.75 mm area. Given that K and Cl form KCl, this leaves the remaining K to react with Ca to form K2Ca2(CO3)3/fairchildite, and the remaining minerals found in the ash. Though ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 and fairchildite concentrations vary from different areas, calcite and sylvite are always present. The variations in mineral concentrations are probably governed, in part, by the local concentration of whewellite raphids.

Conclusions

Wildfire is an important geological process as it influences bulk, widespread surficial mineral formation, erosion patterns, sediment transport, soil formation and atmospheric chemistry. Thus, in this broader, time-scale perspective, wildfires are part of the geological processes that shape the Earth’s surface. In addition, the inorganic phases in the ash are minerals. The ash K2Ca2(CO3)3 phase is probably widespread in wildland fire ash but is up-to-now unreported. A difficulty in identifying and studying the K–Ca double carbonates stems from their moisture instability, all of which readily decompose to calcite and presumably a soluble K salt in water.

The discovery of K2Ca2(CO3)3 as an abundant phase in the ash of the D. wheeleri plant expands our understanding and knowledge of Earth’s mineral diversity, especially concerning the widespread geological process of wildfire ash formation. In addition, the occurrence of K₂Ca₂(CO₃)₃ in plant ash is an example of an inorganic phase that bridges the gap between biomineralisation and geological mineral formation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2025.10098.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Adam Bromley (Globe District Manager, United States Department of Agriculture) for giving me permission to access the area burned by the Telegraph Fire in the Tonto National Forest during the forest closure. I also thank Dr. Kenneth Domanik for his expertise and assistance on the microprobe in The Michael J. Drake Electron Microprobe Laboratory at the University of Arizona; Prof. James Bell for the use of the powder diffractometer in the Planetary Space Extreme Environments Laboratory at Arizona State University; to Dr. A.V. Arefiev for the synthetic K2Ca2(CO3)3 Raman data; and, to the staff and for the use of the facilities in the John M. Cowley Center for High Resolution Electron Microscopy at Arizona State University. LG is grateful to the editors, two anonymous reviewers, and the structures editor Prof. Peter Leverett for their reviews of this manuscript.

Funding statement

L.G. was funded in part by an ASU Investigator Incentive Award (IIA# PG04789).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.