Prelude: weaving through the wild

The taiga feels both known and new, carrying traces of landscapes I have walked before. There is a rhythm here—a quiet pulse beneath moss and root that stirs memory. The scent of the forest, the stretch of birch limbs, the play of light through leaves—these sensations thread through me, influencing how I move, pause, and listen. They remind me of places and times that have shaped my knowing yet ask me to attend anew.

Renske and I, as researchers, let a ball of hemp twine unspool behind us, each thread tracing a quiet entanglement with the landscape. Our practice, inspired by Fluxus, is simple but grounding. Each step is a gesture of attention where we listen—not with expectation, but with presence, and an openness to be affected. The twine does not follow a path of our making alone. It is shaped by the taiga, snagging on branches and bushes and caught in the slow curve of the terrain. The unpredictability of the landscape becomes a co-researcher, disrupting assumptions of control and inviting relational entanglement.

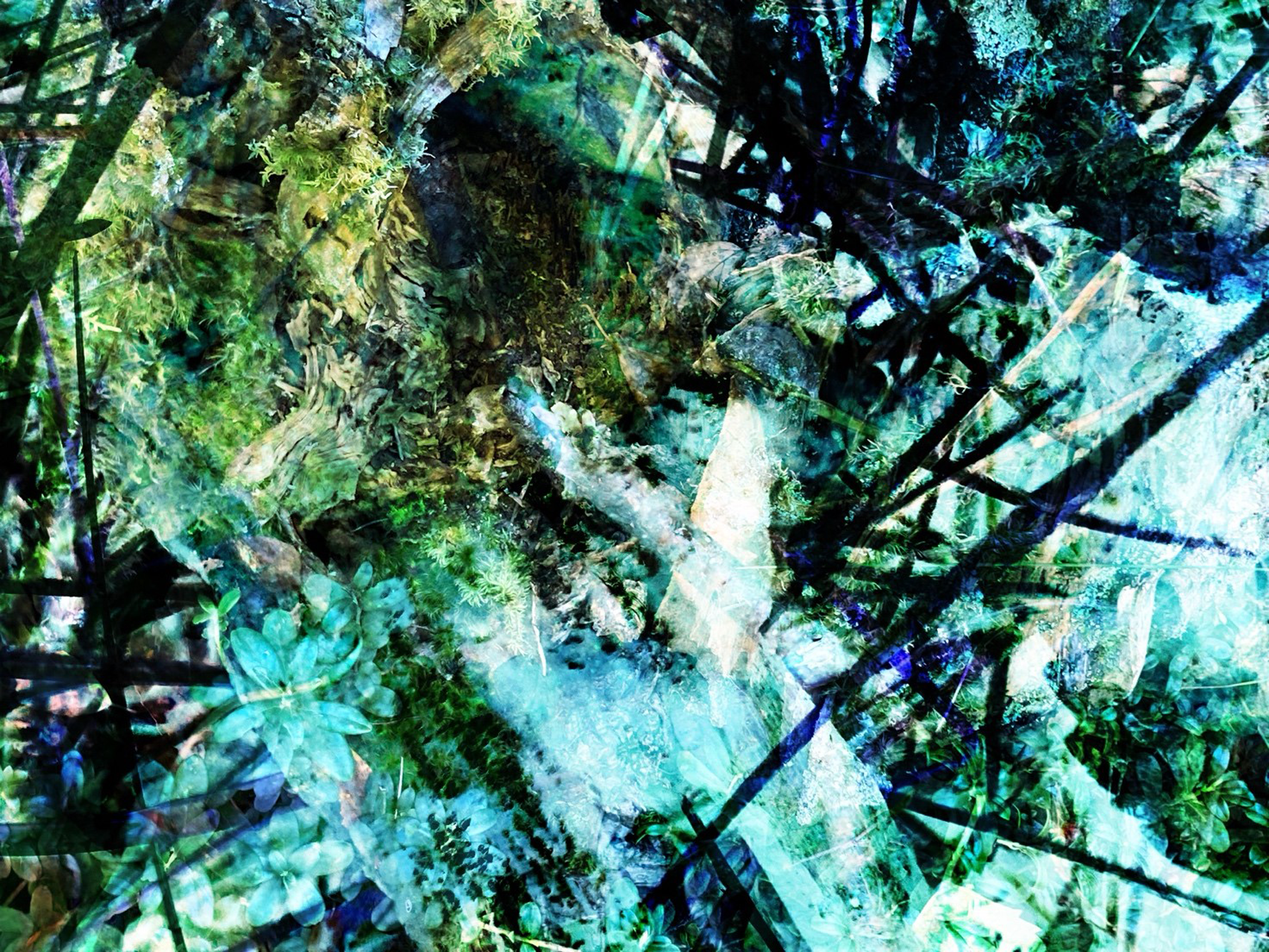

We do not walk through the taiga; we walk with it. Roots press into the soil, weaving unseen networks below our feet. Lingonberry leaves reach skyward. The twine traces not only our steps but the landscape’s quiet claim on us—its invitation to notice, to linger, to be claimed in return. It becomes more than a marker of where we have been; it becomes a record of where the forest has reached back, pressing itself into our awareness (Figure 1).

We move through the taiga where spruce and birch lean together like old companions, their branches knitting the world closer around all who pass. Each step feels like a negotiation, a conversation with the ground’s subtle insistence to move carefully. Walking with the taiga means yielding to its ongoing story—becoming woven into the layers of moss and root, light and shadow. It is a practice of presence, of learning to move as one who is already entangled.

Beneath the surface, the taiga carries stories of transformation, some unfolding slowly, others with urgent momentum. Climate change alters its ancient cycles of growth, decay, and renewal. The lichen signals its quiet distress in hues that mark change. It does not offer answers but asks for presence—a willingness to stay and listen. Walking becomes an act of witnessing, a way of carrying these transformations with care, knowing that each step presses lightly on the edge of loss and renewal.

Our senses sharpen. Damp moss, leaves deepening in autumn colour, the brush of the wind—hinting at a depth of aliveness that transcends us. This is not our space to tame but to meet, a call to step beyond ourselves. The taiga speaks in low, rooted tones, reminding us of the patience and presence it takes to live here.

A young birch leans into the path, prompting a quiet pause in our rhythm (Figure 2).

Nearby, Tuure—another researcher—lifts a handmade flute, exhaling a melody shaped by the land itself. The sound, earthy and unpolished, emerges from the hollow stem of an indigenous plant. It curls into the air and mingles with birdsong and wind—an exhalation dispersing into the landscape. A shiver runs through the birch leaves. The melody stills us. It dissolves the boundaries between self and forest, breath and wind. It carries the strain of a world in flux, the fragile grace of life’s persistence. Calling us toward something larger, already in motion.

When the last note fades, the silence that follows is not emptiness but presence—a lingering fullness. The twine, heavier now, holds the weight of where we lingered, each loop a record of entanglement. As we retrace our steps, we understand this was never about answers, but about listening. The taiga does not call us back; it simply remains—patient, enduring (Figure 3).

Prelude as an enactment of wild pedagogies

This Prelude enacts a process of attunement with the more-than-human world, where the taiga is not just observed but becomes an active participant in the encounter. It impresses itself upon us, asking for care, attention, and response, in a mode of sensing that recalls Baker’s (Reference Baker2020) intense, affective tracking of place . The twine, initially a simple marker of our path, becomes a record of entanglement, mapping where the taiga’s presence has met our awareness. The flute, unpolished and raw, does not simply sound—it disrupts, reorienting perception and blurring the boundary between self and world.

These encounters, where something shifts, where we are compelled to listen differently, create openings for new ways of relating. Wild Pedagogies call for threshold encounters (Manning, Reference Manning2016), where certainty dissolves, and sensing becomes porous, inviting the unknown. Such shimmering ruptures (Malone et al., Reference Malone, Logan, Siegel, Regalado and Wade-Leeuwen2020; Rose, Reference Rose2017) act as portals into deeper attunement, and gesture toward learning-with rather than learning-about the world. These are not abstract exchanges but embodied affective moments where the landscape asserts its presence and insists on response.

Wild Pedagogies invite this kind of openness, not as an intellectual exercise, but as an affective practice—learning through disruption, resonance, and attunement. Love, in this framework, is not sentimental; it both unsettles and binds. It can dissolve the illusion of separation, and pull us into entangled agency (Barad, Reference Barad2007). It is a force that reminds us we are already implicated, already shaped by the places we pass through and that pass through us.

This affirmative approach is an active engagement with alternative possibilities (Staunæs & Raffnsøe, Reference Staunæs and Raffnsøe2019)—ways of sensing, knowing, and becoming-with the more-than-human world. Even if attunements remain partial and incomplete, they serve as experiments in hope (Bloch, Reference Bloch1985), testing the boundaries of what is possible in education, ethics, and ecological care. They remind us that attunement is not about arriving but about staying—with questions, with loss, with the murmurs of the forest that ask us to linger longer, to listen deeper, to remain present.

To walk through the taiga is to be claimed by it. We do not simply come back to where we started; we return differently. If education is to cultivate an ethics of entanglement, it must move beyond mastery toward learning to be undone—surrendering to the shifting textures of relational becoming. The following discussion situates this within the theoretical landscape of Wild Pedagogies, tracing how love as an affective force compels new ways of knowing and becoming. Rather than offering universal claims, this inquiry is situated and experimental, aligning with post-qualitative commitments to relational, affective, and embodied modes of knowing (Østern et al., Reference Østern, Jusslin, Nødtvedt Knudsen, Maapalo and Bjørkøy2021; St. Pierre, Reference St. Pierre2021).

Introduction: reimagining education as an act of love

The taiga’s shifting rhythms invite a deeper kind of listening, one that requires patience, presence, and openness to being shaped by place. Yet, these rhythms are not steady. They carry subtle signals of change, reminding us of the urgencies embedded in the living world. These urgencies speak of the escalating environmental crises of our times, driven by unsustainable practices and a growing disconnection from the natural world, which threaten the intricate fabric of life. From human communities to ecosystems, from plants and animals to oceans, and even the very air we breathe (Kuchta, Reference Kuchta2022, p. 191), the earth speaks in insistent tones. Through shifting climates, rising storms, and vanishing species, the more-than-human world expresses the strain of deep disturbance. But do we know how to listen?

A growing number of scientists and environmental historians cautiously suggest that Earth is entering—or may have already entered—a new geological epoch known as the Anthropocene, marked by significant human influence on the planet’s systems (Jickling, Reference Jickling, Jickling, Blenkinsop, Timmerman and Sitka-Sage2018). The Anthropocene amplifies profound solitude and loss. Deborah Bird Rose (Reference Rose2011, p. 19) describes it as an epoch in which we witness “the actual loss of co-evolved life.” “As Earth others depart, we face a diminished and impoverished world,” writes Rose (ibid., p. 19). We are witnessing extinctions not only of species but of ways of being, knowing, and relating to the world. The rupture is ontological. How do we reorient ourselves? How do we cultivate pedagogies that do not simply acknowledge the crisis but invite us to feel-with the world—that entangle us more deeply in its rhythms, aches, and wild persistence?

Traditional education, rooted in Western modernity, offers little guidance. With its emphasis on mastery, control, and knowledge as commodity, it is poorly suited for to the kind of ethical, embodied attunement the current moment demands. Stemming from Enlightenment thought, traditional models prioritise rational abstraction over felt experience, reinforcing an anthropocentric logic that sees the natural world as a resource (Plumwood, Reference Plumwood2003). This rationalisation of domination has contributed to the ecological crises we now confront (ibid.). Cartesian dualism further embeds a hierarchical worldview in which the natural world is seen as inert matter rather than as an agentic force (Braidotti, Reference Braidotti2013, Reference Braidotti2019; Shiva, Reference Shiva1988). This “ontology of separation” (Escobar, Reference Escobar2020, p. 122) is not only a philosophical construct—it is an epistemological condition that structures how we learn, think, and relate.

Wild Pedagogies have emerged in response to this crisis, resisting dominant educational paradigms that prioritise mastery, control, and anthropocentric knowledge systems (Jickling et al., Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop and Morse2018, Reference Jones2024). However, they have yet to fully explore the role of affect—how relational intensities, disruptions, and resonances shape learning in ways that move beyond cognition toward deeper ethical entanglement with the world.

This article addresses that gap by foregrounding affect as a crucial force in ethical learning. It offers a different understanding of love—not as a sentimental disposition, but as an emergent, affective force that moves through encounters, shaping perception, responsiveness, and co-becoming. Unlike cognitive approaches that maintain a distinction between self and other, this study explores how affective forces can shape relationality, attunement, and ethical engagement (Massumi, Reference Massumi2002; Gregg & Siegworth, Reference Gregg and Seigworth2010; Mühlhoff, Reference Mühlhoff2019; Slaby & Von Scheve, Reference Slaby and Von Scheve2019, Slaby, Reference Slaby2019). It is situated within posthuman and post-qualitative traditions, drawing particularly on affect theory (Massumi, Reference Massumi2002; Slaby, Reference Slaby2019), feminist relational ontologies (Barad, Reference Barad2007; Despret, Reference Despret2002), and emergent ecological pedagogies (Haraway, Reference Haraway2016; Tsing, Reference Tsing2015). It approaches theory not as a fixed lens but as a companion to practice, unfolding through situated encounters. It extends Wild Pedagogies by emphasising how affect can move between human and more-than-human bodies, unsettling perception and enabling ethical responsiveness.

Love, in this sense, unfolds through three interwoven affective pathways:

1. Shimmering rupture—moments that unsettle habitual perception and create openings for new ways of relating.

2. Relational resonance—the movement of affect between bodies that binds them into co-becoming.

3. Cyclical attunement—an iterative deepening of ethical engagement over time.

Framing love as an affective force, this article extends Wild Pedagogies by showing that learning is less about mastery and more about being drawn into the world’s unfolding urgencies and entangled relations. Through immersive vignettes and theoretical reflection, it examines how attunement to love might foster an emergent ethic of care—one that can resist anthropocentric paradigms and embrace the uncertainties, fragilities, and the transformative possibilities of co-becoming (Innola, Reference Innola2024).

Research questions and purpose

This article explores love as an affective, relational force in Wild Pedagogies, fostering ethical co-becoming with the more-than-human world. It investigates:

How do love, care, and compassion emerge in learning encounters with the more-than-human world?

What affective pathways shape learning and ethical attunement within Wild Pedagogies?

How can Wild Pedagogies better account for affective forces in fostering ecological responsibility and transformation?

Positioning the contribution

Wild Pedagogies resist control-driven structures of mainstream education, emphasising relational, embodied, and eco-centric ways of learning. However, while previous scholarship highlights the importance of relationality, it has yet to fully theorise affect as an active force.

This article expands on the Learning to Love, Care, and Be Compassionate touchstone (Jickling, Blenkinsop & Morse Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop and Morse2024), bringing affect theory into dialogue with Wild Pedagogies. It reframes love not as a static ideal but as an emergent force unfolding through three interwoven processes: shimmering rupture, relational resonance, and cyclical attunement. By making these affective pathways explicit, this article repositions love as a material, relational force that reshapes perception, ethics, and pedagogical practice in Wild Pedagogies.

Literature review: wild pedagogies and their theoretical foundations

Wild Pedagogies challenge control-driven, anthropocentric education, advocating for relational, eco-centric, and responsive learning. Rather than treating nature as a passive backdrop, Wild Pedagogies recognise the more-than-human world as an active pedagogical force (Jickling et al., Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse and Jensen2018), disrupting human-nature dualisms and fostering ethical entanglement with the world.

These pedagogies draw from posthumanism, phenomenology, and deep ecology. Posthumanist perspectives decentre human exceptionalism, emphasising interdependence (Jickling & Blenkinsop, Reference Jickling and Blenkinsop2020). Phenomenology prioritises embodied, sensory experience, positioning learning as an affective and material. Deep ecology’s commitment to the intrinsic value of all life aligns with Wild Pedagogies’ rejection of nature as a resource (Næss, Reference Næss, Seed, Macy, Fleming and Næss1988). Indigenous epistemologies further shape this landscape, viewing education as a reciprocal relational process between human and more-than-human beings (Jickling & Morse, Reference Jickling and Morse2022).

Wild Pedagogies are structured around key “touchstones”, originally emphasising nature as a co-teacher, embracing complexity and spontaneity, locating the wild in both remote and built environments, rethinking time and pedagogical practice, fostering socio-cultural change, and building partnerships beyond human communities (Jickling et al., Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse and Jensen2018). In 2023, two new touchstones were introduced: “Learning to Love, Care, and Be Compassionate” and “Expanding the Imagination” (Jickling et al., Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop and Morse2024). The seventh touchstone underscores affect’s role in fostering ethical and reciprocal relationships with the more-than-human world, challenging human exceptionalism and advocating for deep ecological empathy (Jickling & Blenkinsop, Reference Jickling and Blenkinsop2020).

This idea is echoed in foundational environmental philosophy. Næss (Reference Næss, Seed, Macy, Fleming and Næss1988) was profoundly shaped by witnessing a flea’s death, catalysing his deep ecological perspective. Leopold (Reference Leopold1986) developed the land ethic after watching a wolf die, shifting his understanding of ecological interdependence. Carson (Reference Carson1962), through childhood roaming, cultivated a deep sense of wonder and care for the environment, later writing Silent Spring, a book that awakened public consciousness to ecological destruction. These examples show that care and compassion emerge not from abstract ethical principles but through affective, embodied encounters with the more-than-human world. Such experiences may evoke joy, grief, loss, or discomfort, all of which play a crucial role in fostering ecological awareness and responsibility. In this light, Wild Pedagogies advocate for an education that makes space for emotional and ethical complexity, recognising the role of feeling as central to learning.

Despite these contributions, Wild Pedagogies have yet to fully explore affect as an active force in learning encounters. While scholars acknowledge the role of love, care, and attunement, the specific affective pathways shaping pedagogical encounters remain undertheorised. This article addresses this gap by foregrounding affective intensities, disruptions and relational resonances as forces that unsettle perception and deepen ethical engagement. Rather than treating affect as an additional dimension, this study examines how it actively structures moments of learning, shaping ethical responsiveness and ecological attunement. In making these affective pathways explicit, this article extends Wild Pedagogies, potentially enriching our view of how learning unfolds through relational intensities and affective entanglements in wild pedagogical encounters with the more-than-human world.

Theoretical framework: love, affect, and ethical relationality

Wild Pedagogies emphasise love, care, and compassion as essential for fostering deeper connections between humans and the more-than-human world (Jickling et al., Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop and Morse2024). Love emerges not from abstract principles but through embodied affective encounters (Derby, Reference Derby2015), aligning with deep ecology’s call for relational ethics (Næss, Reference Næss, Seed, Macy, Fleming and Næss1988) and Indigenous epistemologies that view knowledge as reciprocal and emergent (Simpson, Reference Simpson2017; Todd, Reference Todd2016). While love’s ethical role is acknowledged, its affective dimensions—how it moves, disrupts, and binds human and more-than-human worlds—are less explored. Drawing on affect theory (Gregg & Seigworth, Reference Gregg and Seigworth2010; Mühlhoff, Reference Mühlhoff2019; Massumi, Reference Massumi2002; Slaby & Von Scheve, Reference Slaby and Von Scheve2019; Slaby, Reference Slaby2019) this article conceptualise love as an affective force—an unfolding intensity that does not reside in a subject but circulates through encounters, shaping and being shaped by perception, responsibility, and attunement.

Shimmering rupture: love as disruption of the habitual

Wild Pedagogies embrace uncertainty and transformation (Jickling et al., Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse and Jensen2018). Shimmering rupture theorises moments of affective breach, when habitual perception is unsettled, prompting new relational attunements (Rose, Reference Rose2017). This builds on Rose’s (Reference Rose2017) articulation of shimmer as an aesthetic and ethical force emerging through relational entanglements and Malone et al.’s (Reference Malone, Logan, Siegel, Regalado and Wade-Leeuwen2020) understanding of shimmer as an ontological and epistemological opening—a dynamic process that oscillates between past, present, and future, continually reconfiguring perception. Shimmering rupture marks the point at which love’s intensity unsettles the known (Allison, Reference Allison2019). It is a threshold experience (Manning, Reference Manning2016), an affective intensification that demands response before it is fully understood.

These ruptures—whether witnessing a felled tree, a drought-altered river, or the raw notes of a flute merging with wind—are felt before they are understood. They disrupt habitual knowing and invite deeper ethical engagement (Brennan, Reference Brennan2004; Malone et al., Reference Malone, Logan, Siegel, Regalado and Wade-Leeuwen2020). Such moments occur when an encounter breaks through the ordinary, making the world perceptible in unexpected ways. This can be a moment of profound grief, the recognition of ecological loss, or a sudden affective recognition of entanglement with another being (Malone et al., Reference Malone, Logan, Siegel, Regalado and Wade-Leeuwen2020). While often unsettling, such moments are generative, offering potential pathways for deeper ethical engagement.

From rupture to ethical attunement

A rupture alone is not enough, it must be carried forward into a sustained practice of attunement. This is where relational resonance emerges, transforming disruption into an ongoing ethical response. This perspective resists viewing shimmer as a metaphor for ecological wonder, instead recognising it as an affective, ethical phenomenon that challenges and reorients perception.

Relational resonance: love as an affective flow

Relational resonance describes how love circulates as an affective flow, binding beings into processes of co-becoming (Innola, Reference Innola2024; Mühlhoff, Reference Mühlhoff2019; Slaby, Reference Slaby2019). It builds on relational affect (Slaby, Reference Slaby2019) and affective resonance (Mühlhoff, Reference Mühlhoff2019) emphasising love’s pedagogical and ethical dimensions. Unlike forms of love framed in anthropocentric ethics, relational resonance shifts love into the realm of affective circulation, where it is neither given nor received but felt, carried, and reshaped through encounters with the more-than-human world. Here, love is not a conscious act or internal disposition, but an emergent force that claims participants in an entangled relationality (Malone et al., Reference Malone, Logan, Siegel, Regalado and Wade-Leeuwen2020), compelling responsiveness, not through moral obligation, but through the affective pull of co-becoming (Innola, Reference Innola2024).

Co-becoming (Innola, Reference Innola2024) is an ongoing, rhythmic, and emergent—aligned with Haraway’s (Reference Haraway2016) notion of becoming-with, emphasising that relationality is not simply given but continuously made, unmade, and remade through dynamic encounters, and relational ontologies (Barad, Reference Barad2007), arguing that entities do not pre-exist their relations but emerge through them. Relationality is not static but continuously made, unmade, and remade through dynamic encounters. Wild Pedagogies extend this to the ethical learning, challenging the assumption that humans give love to the natural world, and suggesting that love is already in motion—woven into the material flows of rivers, the vibratory presence of trees, and the more-than-human invitations to attune differently (Tsing, Reference Tsing2015).

Relational resonance reshapes perception, moving through affective pulls that disrupt separateness. To experience affective resonance with a landscape, an animal, or an atmosphere is to become aware of a shifting relationship—one that is not entirely within one’s control. Love here is not always comforting; it can be unsettling and disorienting. The Prelude elaborates this: the raw notes of the flute blur the line between human breath and wind, while the unravelling twine pulls attention to the unseen forces or more-than-human agency. These encounters press against perception and compel a different way of engaging with the world. Allison’s (Reference Allison2019) notion of affect folding back on itself helps articulate how love does not simply move outward but reverberates, altering perception over time. Relational resonance moves through and beyond immediate encounters, shaping attunement and evoking response and participation rather than detachment.

The demands of resonance: learning to be affected

Relational attunement requires developing the capacity to be affected (Despret, Reference Despret1999, Reference Despret2002)—to engage with others, human and more-than-human, in ways that are dynamic, reciprocal, and transformative. This is not simply about noticing but about being open to being touched, reoriented, and made vulnerable by relational forces (ibid). Attunement is not a passive state but an active process of participation (Mühlhoff, Reference Mühlhoff2019). To attune to another, whether a person, an ecosystem, or a shifting atmosphere, is to step into an encounter that is not fully within one’s control (Massumi, Reference Massumi2002). Caring-for is not merely an extension of care but an entanglement in reciprocal exchanges where one’s own subjectivity is altered. Being moved by the world means recognising that love is not a fixed internal state but a force that circulates through relations, compelling ethical responsiveness.

Rather than an abstract ideal, love emerges as an ongoing engagement with the urgencies and fragilities of the world. As Despret (Reference Despret2002, p. 125) suggests, attunement is a practice that requires sustained openness rather than certainty. Through this lens, love becomes an ethical mode of being—one that demands responsiveness, adaptation, and a willingness to be affected. Attunement is an active process of making oneself available for practices that “create and transform through the miracle of attunement” (Despret, Reference Despret2002, p. 125). This perspective extends Wild Pedagogies by shifting from love as a cultivated disposition to love as an affective entanglement—a force that acts upon and through bodies, reconfiguring relationships beyond language and cognition (Slaby & Von Scheve, Reference Slaby and Von Scheve2019).

Learning, then, is not about acquiring knowledge but about becoming implicated, or drawn into new modes of responsiveness. Within Wild Pedagogies, relational resonance invites us to ask: What does it mean to be claimed by a place, a moment, an encounter? How does love operate beyond human emotion, moving through ecologies and altering the ways we learn and relate? In what ways does love bind beings together in shared vulnerability, suggesting interdependence and fragility as the very conditions of existence? The answers to these questions do not reside in intellectual understanding alone. They must be felt, lived, and moved through. To experience relational resonance is to be drawn into the affective currents of the world, to be reshaped in their wake, to emerge—again and again—differently attuned.

Cyclical attunement: love as rhythmic practice

If shimmering rupture unsettles and relational resonance binds, then cyclical attunement is what sustains love over time. Cyclical attunement encapsulates how love persists through repeated acts of care, attention, and return, a concept drawing from Deleuze and Guattari’s refrain (Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1988). Love in this conceptualisation is not a single realisation but a refrain—a rhythmic iterative process of returning, noticing, and responding (ibid.).

This is a love that resists extraction or possession; instead, it unfolds through repetition, familiarity, and persistence (Manning, Reference Manning2016; Stewart, Reference Stewart2007). It is a practice of staying-with, moving beyond an affective spark into a sustained, ethical way of relating (Haraway, Reference Haraway2016). It is a love that is rhythmic rather than fixed, iterative rather than complete—one that does not impose control but instead listens, responds, and adapts to the shifting conditions of being-in-relation (Tsing, Reference Tsing2015). Allison’s (Reference Allison2019) discussion of self-formation (Bildung) as an affective process provides insight into how learning-with the world demands both vulnerability and endurance—a willingness to be changed over time. Love, in this sense, is made durable through the quiet insistence of relational rhythms (Tsing, Reference Tsing2015).

The rhythm of love in everyday life

Love’s movement is not linear. It does not build toward an endpoint but returns, loops, and shifts, finding its way through the ordinary and the repeated. A shared walk, a lingering glance, the habitual pause to listen to the wind moving through trees—these are not just moments of connection, but the pulse of relational life itself. As feminist theorists like Manning (Reference Manning2016) and Stewart (Reference Stewart2007) remind us, the ordinary carries its own intensity—it is where love is lived, sustained, and made real. These subtle rhythms of relation, while easy to overlook, are the very conditions that make love durable. A learner walking the same forest trail each morning begins to notice subtle shifts—the scent of wet earth after rain, the changing chorus of birdsong, the way light filters through trees. A researcher returns to the same river year after year, not to master its knowledge, but to enter into rhythm with its flows. These are the rhythms through which love holds, shifts, and deepens. Cyclical attunement is about persistence, about returning, even when things change.

Conclusion: love as an affective force in wild pedagogies

Through shimmering rupture, relational resonance, and cyclical attunement, love emerges as an affective force that shapes learning as participation in the world’s unfolding urgencies. Love does not merely reside in human emotions but circulates through relational intensities, rupturing the known, pulling beings into co-becoming, and sustaining ethical engagement with the more-than-human world. It demands attentiveness and ethical responsiveness—not as control or mastery, but as an ongoing, rhythmic engagement with the world. To attune is to take responsibility—to remain open, to keep listening, to stay-with (Haraway, Reference Haraway2016) the world’s unfolding rhythms. This form of attunement is not always easy nor harmonious. Relationships shift, fray, and drift apart, yet love’s rhythm can persist even in rupture and absence. A learner who initially perceives a forest as beautiful may, over time, attune to its deeper ecologies: the seasonal transformations, the movement of water, the interwoven histories of its species. Cyclical attunement offers a way of understanding love as a rhythmic practice, unfolding through iterative engagement with the world.

Returning to the guiding questions of this inquiry, love emerges not in isolation but through affective entanglements, shaping perception and ethical responsiveness. To love in Wild Pedagogies is to understand learning as a recursive process of returning, deepening engagement, and sustaining care. It is to recognise that attunement is never complete, that learning is iterative, rhythmic, and unfinished, a continual practice of noticing, responding, and staying-with the world’s unfolding complexities (Tsing, Reference Tsing2015).

Moving otherwise: a praxis of attuning with the living world

This research employs an experimental relational methodology—or more precisely—a more-than-method—inspired by post-qualitative inquiry (Østern et al., Reference Østern, Jusslin, Nødtvedt Knudsen, Maapalo and Bjørkøy2021; St. Pierre, Reference St. Pierre2021) to explore affective entanglements with the more-than-human world (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Holman Jones and Ellis2021). Instead of adhering to rigid structures, this approach unfolds as a co-becoming process, embracing “ambiguity, contradiction, contingency, and chance” (Bochner & Ellis, Reference Bochner and Ellis2022, p. 15). In line with Wild Pedagogies, it resists mastery, focusing instead on affective ruptures—moments that unsettle, provoke, and transform our ways of knowing. Walking and writing are approached in this article as relational, ethical experiments—open-ended practices shaped by attunement, interruption, and co-presence with the living world. In this sense, the inquiry resists the notion of methodology as fixed form; it becomes more-than-method, a living praxis of listening, moving, and responding with—one that asks not only what we know, but how we are moved in the process of knowing.

This inquiry approaches autoethnography as a critical, embodied practice—as “living bodies of thought” (Holman Jones, Reference Jones2016), where theory and experience are inseparable, and where the self is situated, relational, and in ongoing negotiation with the more-than-human world. This understanding of embodiment and relationality resonates with dos Santos’ (Reference Dos Santos2022) view of empathy as an emergent, embodied process shaped through sensory engagement and responsive attunement. Writing becomes a site of enounter—a movement-with fostering what Spry (Reference Spry2016, p. 15) calls “a wilful embodiment of ‘we.’” The inquiry draws on crystallisation (Richardson, Reference Richardson2000), adopting an experimental and multi-voiced form that weaves narrative, theory, and image—not to illustrate, but to evoke. Imagery is used as affective provocation, inviting readers into the study’s entanglements.

Walking follows Springgay and Truman’s (Reference Springgay and Truman2018) framing of embodied inquiry: an act of attunement shaped by the resistance and unpredictable nature of place. Following Halberstam’s (Reference Halberstam2011, p. 2–3) call to embrace “failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing”, this study seeks to cultivate a space for play, improvisation, and friction. These tensions, as Rose (2015, p. 3) suggests, offer “abrasive edges” that unsettle habitual thought and open new possibilities. This is not an extraction of knowledge but a “regenerative praxis” (Deger & Coffey, Reference Deger and Coffey2024, p. 87), enacting Wild Pedagogical principles of relationality, disruption, and emergence.

At its core, this more-than-methodology embodies Domínguez (Reference Domínguez2000, p. 389) call to “show love openly”—not sentimentally, but through care, vulnerability, and responsibility (Hansen & Thorsted, Reference Hansen and Thorsted2022, p. 352). In resonance with Rose’s (Reference Rose2013) call for “slow writing,” this research resists resolution, lingering with complexity, grief, and entanglement as it writes into the Anthropocene with care and correspondence (Ingold, Reference Ingold2021) rather than control. Echoing Richardson’s (Reference Richardson2001, p. 36) assertion that “what you write about and how you write it shapes your life, shapes what you become,” we embrace wildness, uncertainty, and relational experimentation as methodological principles in motion.

Encounters with wild pedagogies: learning through affect and entanglement

The following vignette illustrates how shimmering rupture, relational resonance, and cyclical attunement function as affective pathways in Wild Pedagogies. It is an enactment of how love, care, and ethical responsiveness might emerge through affective entanglements with the more-than-human world. It exemplifies learning as an affective force, unfolding through disruption, resonance, and return—movements that shape perception and ethical attunement.

Vignette: where the wild grows—a Dérive through the city’s cracks

The dérive (Debord, Reference Debord2014), a sensory-driven wandering, disrupts habitual ways of seeing and experiencing spaces, allowing for deeper entanglement with place. In this vignette, the dérive invites researchers into a co-becoming with the city’s shifting textures, histories, and rhythms. It offers more than just a way to move through the city; it becomes a form of wild pedagogy, teaching us (Blenkinsop & Beeman, Reference Blenkinsop and Beeman2010) to unlearn control and embrace uncertainty. As we step into its flow, we’re no longer passive observers but active participants in the urban landscape, writing the “long poem of walking” (Certeau, Reference Certeau1984, p. 101) with our feet.

As we move, the pavement cracks disrupt the illusion of control, unsettling spaces where wildness asserts itself. In these gaps, we see the city’s wild heart pushing back. The cracks serve as the sites where resilience emerges—small blades of grass push through, dandelions anchor themselves in the fractures, scattering seeds that ride the wind like “warrior words” escaping the “surfeit of faces” (Sissay, Reference Sissay2021).

Walking becomes a reciprocal exchange. The rhythm of our steps conforms to the unevenness of the ground, our feet adjusting to the shifting surfaces—smooth where fresh asphalt patches old fissures, rough where the sidewalk crumbles into dust. The surfaces we tread upon push back, wearing down our shoes, imprinting faint outlines of our paths onto the stone.

Tiny purple flowers spill from the curb and graffiti sprawls across weathered walls, a palimpsest of layered messages. The ground is alive with contradictions—decay and renewal, neglect and resilience. We pass butterfly bushes erupting from crumbling mortar and rusted rails, their fragrant plumes unfurling like soft defiance. Dirt stains the pavement, bubble gum hardens into permanent blotches, and the city keeps showing us its layers, its stories, in the places where it cracks.

A line of poetry, etched in bronze, catches the light:

“Pavement cracks are the places / where poets pack warrior words.” (Sissay, Reference Sissay2021)

The words resonate in the spaces between our steps, making the cracks something more than gaps in the concrete. They become places where the city breathes, where life forces its way into the forgotten corners. The cracks are a refuge, holding the smallest, toughest weeds, the life that clings to the edges where human hands have no control. Ivy snakes up the base of a nearby wall, twisting past the remnants of a faded mural, and a thin ribbon of water trickles down a curb, pooling briefly before seeping back into the earth. The cracks seem to draw all these elements together, telling stories of persistence and adaptation, of thriving against the odds (Figure 4).

These aren’t just nature’s stories—they’re stories of survival, of those pushed to the margins, where the city’s neglect runs deepest. Here, too, people find ways to endure, to thrive where the world has turned away. The cracks are where the earth and the overlooked meet, pressing forward where they are not meant to be. The city’s wild heart beats strongest here, in these rough edges, in the persistence that refuses erasure.

Sissay’s words linger as we walk:

“Pavement cracks are the places / where darkness swallows the sun.” (Sissay, Reference Sissay2021)

Light cuts through the spaces between buildings, casting shadows into the cracks where seeds have fallen and taken root. Life and language converge here, inscribed into the pavement, revealing as invitation, a city that holds more than just its surface. Wildness is not a backdrop—it’s part of the city itself, shifting our steps, urging us to notice what we have overlooked, to find the beauty in what is cracked. The cracks also reflect inequalities shaped by race, class, gender, and ability. The derive makes visible these differential experiences, compelling us to notice what remains unseen, to care enough to engage with the world’s broken complexities, both in nature and in the jagged lines of the city.

We move along, finding a rhythm in the uneven ground. The pavement gives beneath our weight, shaping us as we’re shaped by its textures, by the roughness and the resistance. There is love in this exchange—a quiet attunement to the city’s wild heart. Every crack, every defiant blade of grass, every faded word is part of a shared story, a refrain humming beneath the surface. Even in the grey, the cracks hold more than decay—they hold the promise of something waiting to rise.

Discussion: learning through affect and entanglement

The dérive vignette illuminates how Wild Pedagogies unfold through affective pathways of shimmering rupture, relational resonance, and cyclical attunement. It demonstrates that love, as an emergent, affective force, might be cultivated not through deliberate instruction but through embodied encounters that unsettle, resonate, and sustain engagement with place. Like Suchet-Pearson et al. (Reference Suchet-Pearson, Wright, Lloyd, Burarrwanga and Country2013), we approach place not as setting but as kin—an active participant in learning and care.

Shimmering rupture and urban wildness

The dérive disrupts habitual ways of perceiving the urban landscape, drawing attention to how wildness asserts itself in the overlooked spaces of the city. Cracks in the pavement become more than ruptures in the concrete; they are sites of resistance—thin fractures where imposed order gives way to the world’s refusal to be contained. Recognition of this creates moments where perception is unsettled and the ordinary becomes extraordinary. As we walk, the city is no longer a static structure but a place where wildness asserts itself in unexpected ways. Grass blades sway defiantly in the wind, dandelions root in concrete seams, ivy climbs neglected facades. The city breathes through its fissures, whispering of resilience and refusal. Such moments invite participants to dwell in the tension between decay and renewal, forcing a rethinking of how resilience, wildness, and survival manifest within human-made structures.

Deborah Bird Rose (Reference Rose2017) describes shimmer as an aesthetic and ethical force that unsettles perception, making visible the entangled vitality of the world. In these cracks, shimmering rupture occurs—an affective breach that forces us to see the city’s wild heart pushing back against control. The rigid geometries of the sidewalk break open, and in that rupture, new possibilities for relationality emerge. The vignette shows that shimmering rupture is not confined to untouched nature but can emerge in spaces marked by human intervention and neglect.

A bronze plaque embedded in the pavement catches the light:

“Pavement cracks are the places / where poets pack warrior words.” (Sissay, Reference Sissay2021)

The words echo in the rhythm of our steps. Here, rupture is not only an ecological force but a social and political one—a reminder that the cracks hold more than nature’s persistence; they hold stories of resistance, survival, and renewal. The cracks become thresholds where the cityscape surrenders to unruly vitality, inviting deeper ethical engagements with the world.

Relational resonance and ethical responsiveness

Relational resonance arises as participants move-with the city’s rhythms, feeling the roughness of the pavement and adjusting their steps in response. Walking becomes an exchange between body and environment, disrupting the boundary between walker and landscape, and inviting new forms of responsiveness. The poem embedded into the pavement functions as an anchor, slowing the pace of movement and inviting deeper attunement. The words disrupt the flow of walking, drawing attention to the resilience and defiance anchored within the city’s overlooked spaces. This moment of pause creates an opening for relational resonance, an invitation to linger with the cracks, to notice the interplay of nature, decay, and urban textures.

“Pavement cracks are the places / where darkness swallows the sun.” (Sissay, Reference Sissay2021)

In the city’s overlooked corners, relational resonance emerges. A thin ribbon of water trickles along the curb before disappearing into the earth. The air carries the damp scent of concrete and the honeyed fragrance of the butterfly bush. Love, here, is not grand or declarative but quiet, persistent, woven into the unnoticed spaces where life and decay intertwine. Affect circulates between the city’s textures and the bodies that move within it, illustrating how love becomes a felt force of attunement (Mühlhoff, Reference Mühlhoff2019)—one that compels attentiveness to entanglements of overlooked ecologies and social histories.

The vignette raises questions about accessibility and privilege, acknowledging that resonance is not evenly distributed. Social markers such as race, class, gender, and ability shape how each person moves through the city. For some, walking brings invitations; for others, it brings obstacles. The dérive brings these differential affective experiences into focus, making visible who wanders freely, who moves with caution, and whose presence is policed. Love, in this context, is not just noticing—it is recognition, an ethical call to engage with the complexities of who gets to move freely and who is constrained by the city’s structures.

These cracks hold more than wildness. They hold memory, loss, and histories of displacement. Yet, they also open space for new ways of relating, for learning to love differently—with openness, with care, with a willingness to be undone and remade through attunement.

Cyclical attunement and sustained engagement

The dérive reflects how love can be sustained through repetition and return. Each step brings new insights, making the dérive a practice of cyclical attunement, an ongoing practice of noticing, responding and staying-with the city’s evolving textures. Love deepens through this sustained engagement, where recurring encounters—whether with resilient weeds or the ephemeral words of the poem—become landmarks of ongoing relationality. This reiterative process aligns with Wild Pedagogies’ embrace of unpredictability, offering a model for how love and learning can be cultivated through persistent attention to what is often unseen or disregarded.

Extending wild pedagogies into urban contexts

This vignette challenges the assumption that Wild Pedagogies belong solely to natural environments. It extends the conversation into urban ecologies, showing that wildness, resilience, and love also emerge in spaces marked by rupture and neglect. The cracks in the pavement are not just disruptions; they are invitations for deeper attunement—portals into deeper modes of relationality (Slaby, Reference Slaby2019), asking how we relate to the more-than-human in all its forms. This invites a broader understanding of Wild Pedagogies, one that recognises the wild in diverse landscapes, in resilience and resistance. It underscores that learning with the world involves a willingness to be affected, unsettled, and reshaped by the everyday textures of place.

In this way, the vignette emphasises that love, as an affective force, does not depend on grand gestures or pristine settings. It is found in the persistence of weeds, the defiance of neglected corners, and the stories whispered through cracked surfaces. This reframes love as an ongoing, ethical engagement—one that demands noticing the overlooked, lingering in uncertainty, and responding with care and responsibility to the complexities of the world.

By tracing how shimmering rupture, relational resonance, and cyclical attunement emerge within an urban dérive, this discussion deepens our understanding of love as an affective, relational practice. It emphasises that Wild Pedagogies are not bound to particular geographies but can surface wherever the world presses back—wherever we are willing to stay-with, notice, and be moved.

Conclusion: love, learning, and the call to attunement

This article extends Wild Pedagogies by foregrounding affect as a central force in ethical learning. It offers a theoretical framework—shimmering rupture, relational resonance, and cyclical attunement—that articulates how love might emerge as a dynamic, relational, and material practice of ethical engagement. Love, in this framework, is not a static sentiment but a circulating force that moves through affective encounters, unsettling perception and demanding ethical response. It is found not only in grand encounters with nature but in the persistent textures of overlooked, urban spaces.

Shimmering ruptures destabilise habitual perception, relational resonance deepens engagements and shapes care, and cyclical attunement sustains these movements over time through iterative practices of returning, noticing, and responding. To cultivate ethical learning within Wild Pedagogies, it is necessary to recognise that ecological responsibility arises not from knowledge alone but from affective encounters that unsettle, recalibrate, and invite care. Learning is not about mastering concepts but about developing the capacity to be affected, to stay-with uncertainty, and to dwell within the discomfort of not knowing. It is an iterative process of returning to places, questions, and relationships, allowing ethical responsiveness to deepen over time.

This attunement is not always comfortable or harmonious. The more-than-human world often resists comprehension. Such resistance is not a failure of learning but a reminder of the world’s agency and unknowability. It invites an ethics of humility—an acknowledgement that ethical engagement is about dwelling with uncertainty, responding to what cannot be fully grasped, and listening to the world’s silences. Learning-with, therefore, is not about controlling meaning but about opening to it, allowing ethical relationships to unfold in ways that challenge and reshape us.

To love in Wild Pedagogies is to recognise that learning is always unfinished, iterative, and shaped by the wild urgencies of place. It is an ethical practice of noticing, returning, and responding, not to control the world but to participate in its unfolding. Love becomes the movement that sustains ethical engagement, compelling learners to listen, witness, and respond to the world’s shifting conditions.

Thus, this article invites educators, learners, and researchers to embrace love as an ongoing, affective commitment to ethical learning. For educators, accounting for affective forces requires them to design learning experiences that invite disruption and lingering engagement with discomfort—an aspect that supports fostering ecological responsibility. Ethical learning is not about seeking resolution but about cultivating deeper responsiveness to the entangled rhythms that shape our shared becoming. It is an ongoing practice of love, vulnerability, and relational care—an attunement to the world’s persistent urgencies and the possibilities for deeper connection, ethical responsiveness, and transformative ways of relating to the more-than-human world.

Figure 1. Lingonberries, blueberries, and birch leaves form a textured forest floor, capturing the taiga’s vibrant undergrowth.

Figure 2. The forest floor is not singular but multiple: textures of mushrooms, moss, taiga, and our own movements fold into one another.

Figure 3. The twine’s shifting tension mirrors the taiga’s pulse, a tactile reminder of our entanglement whispering its presence through fingertips, binding us to unseen rhythms.

Figure 4. Reflections of Lemn Sissay’s powerful words, diffracted through tiny purple flowers pushing from city cracks.

Acknowledgements

Photo Credits: All photos by Jennifer Ann Skriver, Oulu, Finland, 2024, and Manchester, UK, 2024, with layering and applied filter by Jennifer Ann Skriver, Kolding, Denmark, 2024.

Financial support

Part of this research was conducted in affiliation with the Small Matters Project in Oulu, Finland, which explores death and dying at different scales together with young children and their extended human and more-than-human families. We acknowledge the support of Research Council of Finland for making this portion of the work possible.

Ethical standards

This research was conducted in accordance with Danish national ethical guidelines and the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, revised in 2013. According to the Danish Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects, this study did not require approval by a research ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Author Biographies

Jennifer Ann Skriver is a postdoctoral researcher at Kolding School of Design’s Lab for Play and Design. Her PhD, Advancing Inclusive Playful Learning Practices, explored how artful educational practices can foster inclusive playful learning in higher education. Focusing on the affective and embodied dimensions of pedagogy, her work examines how play and art intersect to support inclusive atmospheres and challenge dynamics of exclusion and privilege in educational spaces. Jennifer’s thinking has been shaped by growing up in the wild landscapes of Alaska — formative experiences that continue to shape her engagement with ecological and relational philosophies. Her current work weaves together affect theory, post-qualitative inquiry, and critical pedagogy to reimagine play as a space of inclusion, ethics, and possibility.

Mathias Poulsen is a postdoctoral researcher at Kolding School of Design’s Lab for Play and Design. His research explores the intersections of play, design, and democratic participation, focusing on how playful practices can foster inclusive and participatory democratic experiences. In his Ph.D. project, Designing for Playful Democratic Participation, Mathias investigated the potential of junk playgrounds as spaces for embodied deliberation and collective imagination. Inspired by Braidotti’s (2013) notion of affirmative critique, Mathias approaches research as an experimental, situated, and often playful practice. He is also the founder of the international play festival CounterPlay, which brings together practitioners and researchers to explore the role of play in society.