1.1 Interaction between Technology and Human Cognitive Skills

It is often said that humans have created technology, but seldom is it acknowledged that technology has also created the modern human. Technology has been used to change nature, but what we failed to notice is that as we were using technology, it was also changing us. Literally, the use of technological tools has altered our neural connections (Chun et al. Reference Chun, Choi and Cho2018), and therefore, our way of seeing and understanding the world (Barr et al. Reference Barr, Pennycook, Stolz and Fugelsang2015). With a certain evolutionary perspective and awareness, we continue to perform the same behaviors as our early homo sapiens ancestors, although now mediated by technology. Homo sapiens went hunting while we order Uber Eats; they went out into the village to find a partner while we search for one on Tinder; they spoke with their friends in person while we communicate through WhatsApp. They even painted in caves, and we continue to paint using Photoshop or new artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms like Midjourney, DALL-E, or Stable Diffusion. In other words, we continue to behave in ways that aim to accomplish the same tasks, only now within a much more complex and technology-mediated cultural environment. But what is technology? Technology can be defined in many ways, but as Albert Einstein said, “everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” Therefore, to define what technology is, we can take a Vygotskian approach by considering it as cultural tools with the power to change the human mind (Vygotsky Reference Vygotsky1962, Reference Vygotsky1978). An extension of this definition can be taken from the philosopher Mario Bunge, who conceives of technology as objects or processes of possible practical value for individuals or groups, which have been constructed with the help of knowledge acquired through basic and applied sciences. Additionally, Bunge emphasizes a very important aspect that we do not always associate with technology – that it need not only be physical or chemical, but can also be biological (e.g., language) or social (e.g., education or economics) (Bunge Reference Bunge1983). Ortega y Gasset also contributes to the debate of defining the concept of technology by describing it as a human reaction toward nature or their personal circumstances, in a way that leads to the design and construction of a tool or device that mediates between them and nature (Ortega y Gasset Reference Ortega y Gassetn.d.). Therefore, technology could present the following attributes:

– Functional: Technology is an object, product, device, cultural artifact, or tool (all synonyms) oriented to solve a need, whose material nature may be physical, biological, or cultural.

– Reactive: Technology arises from the biopsychosocial impulse to solve an individual, group, or community need. If it succeeds in solving the need, this technology acquires value.

– Scientific: Technology is a cultural product that is born and updated through the transmission and accumulation of cultural knowledge.

If we review the history of our species, we can observe how tools have influenced the transformation of our species and culture, from the invention of fire to the creation of artificial intelligence algorithms that virtually think for us. It is possible that in the last 100 years more technological progress has occurred than in the rest of human history. This technological advancement is a violent process, so much so that it changes our environment and literally changes us through changing our brains. The brain is a large organ whose functions require a high metabolic expenditure for its operation (Aiello & Wheeler 1995). Once an adequate diet was achieved for the maintenance of its energy costs (Gupta Reference Gupta2016), the brain managed to develop certain higher cognitive skills through overcoming ecological (Clutton‐Brock & Harvey Reference Clutton‐Brock and Harvey1980; Rosati Reference Rosati2017), social (Dunbar Reference Dunbar1998), or cultural (Moll & Tomasello Reference Moll and Tomasello2007; van Schaik & Burkart Reference van Schaik and Burkart2011) challenges. Although it seems that social challenges were the ones that caused or triggered a cognitive explosion, recent research carried out by Mauricio González Forero and Andy Gardner of the University of St Andrews proposes that it was ecological challenges (human vs. nature) that led to an increase in brain size, and therefore, the development of cognitive skills (González-Forero & Gardner Reference González-Forero and Gardner2018). In this regard, one theory that can explain the particular development of human cognitive skills as overcoming ecological challenges is proposed by Nobel laureate Herbert Simon of Carnegie Mellon University, known as “bounded rationality” (Simon Reference Simon1957). Herbert suggests that cognitive development is neither greater nor lesser, but depends on one’s own cognitive limitations and environmental challenges. For example, animals that have easy access to food and/or lack predators do not need to develop complex strategies for obtaining their food, while animals with restricted access to food and/or with threats of being hunted by another predator need to develop skills that allow them to generate strategies for survival. In humans, community organization and the need to obtain resources for the group led to facing different challenges with the cognitive skills they had. The development of technological tools led to the release of new sources of supply and social organization, and therefore, also posed new challenges that promoted the phylogenetic development of executive skills through the reorganization of the prefrontal cortex of the brain (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Dawson and Dyrby2020).

To explain the processes by which technology is able to change our neural connections, we will start with Vygotsky and his sociocultural theory of cognitive development (Vygotsky 1978a). Vygotsky suggests in his theory that the cognitive development that occurs from childhood directly depends on our interactions with the elements of the environment that surround us. Specifically, he points out the importance for our development of symbolic cultural tools, such as language or, in a more contemporary case, the modern digital interfaces of smartphones. These person–tool interactions change our brain wiring, creating “specialized neural niches” in processing the information we obtain through interactions (Pinker Reference Pinker2010). The “neuronal recycling hypothesis” by Stanislas Dehaene offers a modern approach to understand the neuronal process that occurs in us when we acquire a new skill through cultural tools (Dehaene Reference Dehaene2014b; Dehaene & Cohen Reference Dehaene and Cohen2007). This hypothesis indicates that interaction transforms or directly recycles the structure and connectivity of the neural groups responsible for processing the sensory-motor or symbolic information necessary to master the new technology, so that once these brain regions are transformed, we are able to process and manipulate more complex information (Amalric & Dehaene Reference Amalric and Dehaene2016; Dehaene Reference Dehaene2009). Intuitively, we think that the greater the mastery of a skill, the more regions we activate, and this is false. A child who starts to perform simple arithmetic calculations such as addition and subtraction activates the same regions as an expert mathematician performing elaborate arithmetic calculations, only that the brain regions of the mathematician are much more connected (transformed) as a product of his experience in calculation (Cantlon et al. Reference Cantlon, Brannon, Carter and Pelphrey2006; Cantlon & Li Reference Cantlon and Li2013; Izard et al. Reference Izard, Dehaene-Lambertz and Dehaene2008). That is, it is the transmutation of a set of neural circuits that allows us to master the use of a new cultural artifact (Dehaene Reference Dehaene2005, Reference Dehaene2014a; Dehaene & Cohen Reference Dehaene and Cohen2007). A simple but curious experiment tries to explain how tools change the brain (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Montroni, Koun, Salemme, Hayward and Farnè2018, Reference Miller, Fabio and Ravenda2019). In this experiment, an individual was placed in front of a curtain, unable to visualize the object that was behind it. The experimenter asked the subject to grab a stick and hit the object behind the curtain (without being able to see either the object or the stick), and then indicate with which part of the stick he had hit the object. All individuals were able to locate the area of contact of the stick with the object. The authors proposed that this occurred because the stick was processed by the brain as if it were an extension of the hand (extended cognition), as occurs in other animals, such as cats’ whiskers when they brush against a wall. In some way, the brain fails to differentiate between the boundaries of the body and tools when they are in use, thereby integrating sensory information obtained through tools as if it were directly acquired by a sensory organ of the body. Consequently, this sensory information that arrives through tools seeks to adapt and find its own cognitive niche within the brain (Pinker Reference Pinker2010). In the specific case of the experiment just mentioned, the ability to sense tools as part of ourselves is due to the functional coupling between the biomechanical information from skin sensory receptors and the neural processing of higher brain regions (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Montroni, Koun, Salemme, Hayward and Farnè2018). This mechanism of accommodating sensory information, as if acquired through our own organs, has enabled us to rapidly acquire the skill to manipulate new tools, a skill that in turn serves as a foundation for enhancing these tools (Martel et al. Reference Martel, Cardinali, Roy and Farnè2016; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Longo and Saygin2014).

All of this evidence is splendidly summarized in the cultural brain hypothesis, which proposes that through cultural learning, our brains have been selecting and enhancing our cognitive skills for manipulating and storing information obtained through the use of technologies (Muthukrishna et al. Reference Muthukrishna and Henrich2016, Reference Muthukrishna, Doebeli, Chudek and Henrich2018). Among paleoscientists, there is a consensus that most technological innovations of Homo Sapiens have been developed due to the impact culture had on them (Colagè & d’Errico Reference Colagè and d’Errico2020; Bender & Beller Reference Bender and Beller2019; Sterelny Reference Sterelny2020). The impact of culture on humans can be assessed through two phenomena: cultural exaptation and the ratchet effect. The term “cultural exaptation” refers to how the manipulation of technological tools to solve novel challenges has generated a feedback loop of progressive and cumulative cognitive improvements by incorporating new information into cognitive schemas for tool use. The process of integrating this new information with existing cognitive schemas has transformed these schemas into new cognitive models for the use of these technological tools, thus facilitating the development of more advanced tools. In this way, cognitions evolved so that new tools could be created to solve new problems (d’Errico et al. Reference d’Errico, Doyon and Colagé2018; d’Errico & Colagè Reference d’Errico and Colagè2018; Schlaudt Reference Schlaudt2022). For example, stones that were used for cracking nuts came to be used for cutting meat and as a weapon for hunting and attacking enemies. The creation of these new tools results in what is known as a ratchet effect, indicating the irreversible accumulation of these changes, both cognitively and culturally (Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan2010; Tennie et al. Reference Tennie, Call and Tomasello2009). As another example, the ability to name and write numbers was the cognitive basis for performing more complex mathematical calculations. That is to say, our cognition employed these cultural tools (naming and writing) as a foundation to transform itself and be capable of acquiring and processing more elaborate information like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division (Miller & Paredes Reference Miller and Paredes1996). Similarly, the use of devices for problem-solving is able to transform our brain due to its plastic capabilities (Hecht et al. Reference Hecht, Pargeter, Khreisheh and Stout2023). The direct consequence of this ongoing adaptation of our cognitive framework to new technologies has caused us to handle and create increasingly complex tools. This creates a loop where the creation of new tools changes our cognitive environment enabling us to create even more complex tools, thereby changing our cognitive environment yet again, and so on indefinitely. The most recent loop has succeeded in creating digital and virtual technologies, which currently represent the pinnacle of technological development. Many theories aiming to explain the human–culture relationship advocate that most cognitive processes that have allowed for cumulative cultural evolution (the ratchet effect), such as social learning, imitation, teaching, social motivation, theory of mind, and particularly reading, are solely cultural products, denying the importance of genes (Heyes Reference Heyes2014). On the other hand, other positions such as the culture–gene coevolution theory (Chudek & Henrich Reference Chudek and Henrich2011), the dual inheritance theory (Richerson & Boyd Reference Richerson and Boyd1978), and the cultural niche construction theory (Laland et al. Reference Laland, Odling-Smee and Feldman2000) advocate more for an interaction between culture and genes in human evolution.Footnote 1 Regardless of the interaction between genes and culture, both mechanisms allow us to adapt to the environment. While genes are a slow and long-term adaptive mechanism, brain plasticity and cultural objects (such as technological tools) allow for rapid environmental adaptation (Waring & Wood Reference Waring and Wood2021). Indeed, human evolution would be determined by long-term gene–culture coevolution, where culture acts as an evolutionary vector. More recent research seems to validate this theoretical approach, maintaining that although genes significantly influence culture, culture is selecting them (Waring & Wood Reference Waring and Wood2021). In this regard, culture has been overtaking genes as the evolutionary force in humans, which means that genetic traits are increasingly taking a backseat. There is even evidence to suggest that this trend is accelerating with the emergence of technology, reaching the pinnacle of human evolution when people are capable of biologically integrating with technology through soft devices.Footnote 2 This point at which humans merge with machines is known as “technological singularity,” which would imply an exponential acceleration of evolution due to the artificial acquisition of biological and cognitive improvements (Petta Gomes da Costa Reference Petta Gomes da Costa2019), with which interaction would occur through bioelectronic interfaces (Schiavone et al. Reference Schiavone, Fallegger and Kang2020). The integration of individuals with technology is a transhumanist vision of human evolution and has sparked much debate in philosophical and academic circles, such as the dangers of artificial intelligence (Müller Reference Müller2020), the possible emergence of a collective consciousness (O’Lemmon Reference O’Lemmon2020), or even whether the new human resulting from the fusion of man and machine could be considered a new species (Enriquez & Gullans Reference Enriquez and Gullans2015). In this sense, technology, and its digital and virtual derivatives, seem to be determining the course of human evolution, making fields such as human factors or engineering psychology necessary to address not only the impact of technology on individuals and society but also to develop methodologies capable of generating ergonomic interfaces for individuals (APA 2014).

What is currently happening with the incessant emergence of new technologies? As Moore’s law predicted, technology is progressing at an increasingly rapid pace, meaning our brain does not have time to accommodate new tools in their respective neural spaces or niches. Technology is advancing at a pace much greater than the time our brain has to structurally and connectively integrate it. This decoupling between the use of new technology and its integration with neural circuits is known as the “evolutionary mismatch theory,” which could have a real impact on our health, such as an increase in the number of chronic diseases (Corbett et al. Reference Corbett, Courtiol, Lummaa, Moorad and Stearns2018; Pani Reference Pani2000), or chronic stress (Brenner et al. Reference Brenner, Jones, Rutanen-Whaley, Parker, Flinn and Muehlenbein2015). This may be due to the fact that the current technological environment is very different from that with which our central nervous system evolved over millennia. Some scientists question whether the structural organization and neural plasticity of the human brain are incapable of absorbing the evolution of the environments we have created (Pani Reference Pani2000). Even the biological cause of this evolutionary mismatch is hypothesized to lie in the mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic system, which could be overwhelmed by the dopamine release resulting from the continuous acquisition of reinforcers coming from digital environments (Wise & Rompre Reference Wise and Rompre1989). In this regard, the use of technology could induce changes in the dopaminergic system that could alter natural codes in reinforcement-aversion processes, sensorimotor mechanisms, and salient motivational cues; which have remained stable during human phylogenetic development, and which are necessary to associate the consequence of a behavior with a defined emotional state of the organism. This alteration of the dopaminergic system would affect its projections to the prefrontal cortex, which could affect intellectual capacities and emotional regulation of individuals (Pani Reference Pani2000). Therefore, the ways in which technologies currently gratify us are far from those with which our nervous system evolved. We no longer need to “waste” several hours hunting to get food, but we go down to any bar or supermarket and are instantly gratified. Gone are the days when one had to visit a friend’s house to inquire if they wished to go out; now we simply ask via WhatsApp and receive a response within seconds. We live in a society of instant gratification, which leads to an overactivation of the dopaminergic system and emotional deregulation. Nevertheless, technology has become a fundamental part of our lives and how we interact with our environment, with mobile phones being its primary standard-bearer. Mobile phones, with endless gratifications at our fingertips, have become an extension of our brains, fulfilling their needs swiftly and with minimal effort.

There is no doubt about the importance of technology in our lives, but we actually know very little about why and how we interact with it. There exists a vast body of knowledge historically generated from behavioral and cognitive sciences whose principles are perfectly transferable to the digital domain. Although classical authors such as Vygotsky, Skinner, Pavlov, and Hull lived in eras devoid of such technologies, they managed to produce ample theoretical and practical knowledge about human and animal behavior that could specifically explain human behavior within a digital environment, that is, digital behavior.

1.2 What Is Digital Behavior?

Behavior is the interaction of an individual in a physical environment. Conversely, digital behavior is the interaction of an individual in a digital environment (digital space). This distinction is crucial to emphasize, as it forms the axis around which the understanding of how and why digital behavior occurs revolves. Whereas in the physical reality, nature and culture provide us with stimuli, in the digital environment or space, it is technology that furnishes us with stimuli, which in this case are artificial and digitally natured. In the digital space, the technology interface sensorially presents us with stimuli, which can elicit the same effects as stimuli provided by nature or culture (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Robinson, Tsemg, Hsu, Hsieh and Chen2023). This is a central point, as even though the stimuli impacting us are of different natures (natural vs. digital), both are sensory and, therefore, their effects can be predicted using the body of knowledge and tools already created from behavioral and cognitive sciences. That is, digital behavior design aims to use this knowledge and tools to predict possible user behaviors in digital environments and to develop ergonomic services that facilitate habit implementation. Through a study of the needs or goals of users when using a digital service, the digital behavior designer can apply psychological knowledge to identify and analyze the functional elements guiding people’s behavior, thereby proposing an ergonomically sound digital technology solution aligned with their motivations. Digital behavior design can be described as a new subfield of human factors and engineering psychology. Human factors and engineering psychology is a science that studies human–machine interactions mainly to facilitate their use through error reduction and safety enhancement. This science draws from psychological knowledge for the design of products, systems, and devices used daily. The novel contribution of digital behavior design, and why it is included as a new subdiscipline within human factors, is that for the first time a theoretical and reference framework has been created for designing technological and digital products based primarily on the basic principles of associative learning. In this regard, digital behavior design would be a tool of human factors that would automate behavioral processes with which users would utilize various digital services or products. One of the subdisciplines that shares several epistemological areas with digital behavior design is human–computer interaction (HCI). The main difference, albeit nuanced, is that the body of knowledge guiding the former stems more from behavioral and cognitive sciences, while the latter originates from computer sciences.Footnote 3 Furthermore, there is also a significant epistemological difference. Professionals in HCI structure their work considering technology as an end-product, whereas digital behavior designers view technology as a means to satisfy a need. That is, habit formation and need satisfaction constitute the main epistemological core of digital behavior design.

1.3 Epistemological Principles of Digital Behavior Design

The design of digital behavior aims to establish the psychological foundations for the use of a technological service by anticipating user behavior in the digital environment. In this regard, personality and environment are the two best predictors of human behavior and, therefore, also of digital behavior (Cortina et al. Reference Cortina, Köhler, Keeler and Pugh2022; Ozer & Benet-Martínez Reference Ozer and Benet-Martínez2006). Digital behavior design primarily focuses on the environment, as it exerts more influence than personality in guiding specific behaviors (Cortina et al. Reference Cortina, Köhler, Keeler and Pugh2022). In situations where environmental pressure is “strong,” behavior is relatively uniform, regardless of an individual’s personality. Conversely, in situations where environmental pressure is “weak,” behavior is not constrained by the situation and may be more influenced by personality traits. This concept of the dependency of environmental pressure on behavior is known as “situational strength interaction,” which underpins many psychological models of human behavior (Cortina et al. Reference Cortina, Köhler, Keeler and Pugh2022). In this regard, behavioral and cognitive sciences have amassed over a century of scientific knowledge on how the environment affects behavior. These behavioral principles are scattered across various areas related to the development of digital services but are not structured and organized into a single discipline. Moreover, there is an urgent need for this knowledge to be applied in digital areas, given that we spend much of our lives there, and what we currently are and how we feel could be explained by understanding how we behave in the digital world. According to Skinner, the father of operant conditioning and a key figure in behavioral sciences: “We need to go beyond mere observation to a study of functional relationships. We need to establish laws by virtue of which we may predict behavior, and we may do this only by finding variables of which behavior is a function” (Skinner Reference Skinner1938, 8).

Therefore, to access these behavioral principles, which will also explain digital behavior, the scientific method must be used. Like all science, the study of digital behavior is also governed by general axioms:

– Realism: indicates that reality exists independently of the observer.

– Intelligibility: reality, in addition to existing, can be understood.

– Localism: two objects distant in space-time cannot interact instantaneously, so only two objects close in space-time can affect each other instantaneously. This axiom is required for the principle of causality, which states that every event has a cause and an effect.

– Unitarity: for an event that has not yet occurred, the sum of all probabilities of that event occurring must equal one.

It is important to pause here and clarify a crucial point: for many psychologists, determinism is an axiom of science, but this is not entirely accurate (Earman Reference Earman1986). Determinism is the idea or belief that the world follows the laws of cause and effect, not an undeniable axiomatic principle of science. Mechanical determinism summarizes the ideas of Hume and Descartes on causality (Márquez-Blanc Reference Márquez-Blanc2012). Henceforth, the term “causality” will be used to refer to the relationship between two events. To explain and predict the causes of digital behavior, the theoretical principles proposed by behaviorism and cognitivism will be utilized, particularly those represented by the 4Es (embodied, embedded, enacted, or extended) (Carney Reference Carney2020):

– Behaviorism: a set of principles that describe and explain behavior as a product of system–environment interaction.

– Cognitivism 4Es: a set of principles that explain that behavior is the result of interactions between our cognitive system and the environment, but mediated by mental representationsFootnote 4 (or models of the world) that formed as a result of previous interactions.

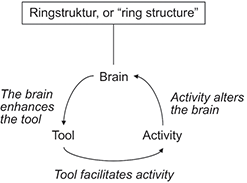

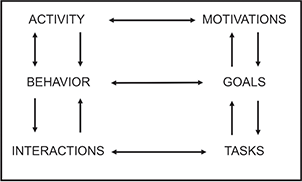

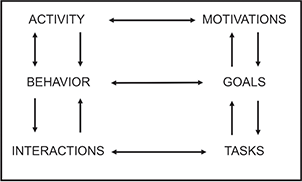

Within cognitivism, the neuroconstructivist approach can also be considered, which suggests that the development of our brain is not an isolated process but is shaped by interactions with other systems over time; thus, behavior and cognition are the result of past interactions (Astle et al. Reference Astle, Johnson and Akarca2023). Two other theoretical proposals that could have a significant impact on the study of digital behavior are Alekséi Leontiev’s activity theory (Leont’ev 1978a) and Karl Friston’s free energy principle (Friston Reference Friston2010). Both proposals could be considered cognitivist. Activity theory aims to explain how tools (such as a hammer or a smartphone) regulate an individual’s activity, which in turn transforms the individual’s psyche (Leont’ev 1978b). This activity is modulated on one hand by the needs, motives, and tasks of the activity itself; and on the other hand, by the actions and operations necessary to perform the activity (execution), which have been defined based on previous needs, motives, and tasks (see Figure 1.1).

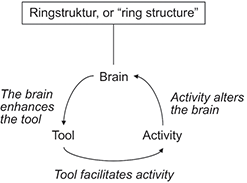

(A) The relationship among tool-activity-brain forms a loop resembling a “ring structure” where each component feeds back into the others. The type of tool determines the kind of activity that can be carried out, and it is this type of activity (behavior) that brings about cerebral changes, optimizing the use of the tool: “The object which the paleolithic tool-maker holds in her hand affects her mental representations (her plan, her goal) as much as those representations affect the changing object. Reciprocal relationships prevail” (Morf & Weber Reference Morf and Weber2000).

(B) This illustration is an adaptation of Leontiev’s model to the specificities of digital behavior. The term “actions” has been replaced with “behaviors” and “operations” has been substituted for “interactions.” For example, the activity of eating would be motivated by a caloric deficit. The behaviors one could engage in might vary, such as hunting, buying food, cooking it, or ordering it through a food delivery app. All of these behaviors aim to acquire food. To perform the digital behavior of ordering food through an app, numerous interactions with the technological object would be necessary, such as tapping the app icon, searching for the desired food option, and selecting the food choice, which are configured as sequential tasks aimed at obtaining the food (Hasan & Kazlauskas Reference Hasan, Kazlauskas and Hasan2014; Leont’ev Reference Leont’ev1978).

Figure 1.1 Activity theory

Activity theory is a theoretical framework for studying human practices as dynamic processes in continuous development.

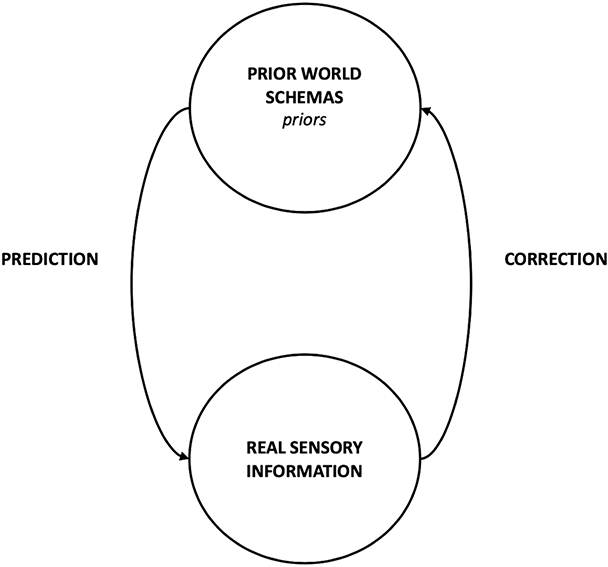

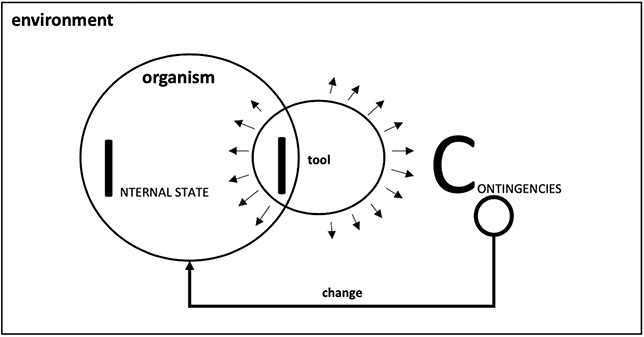

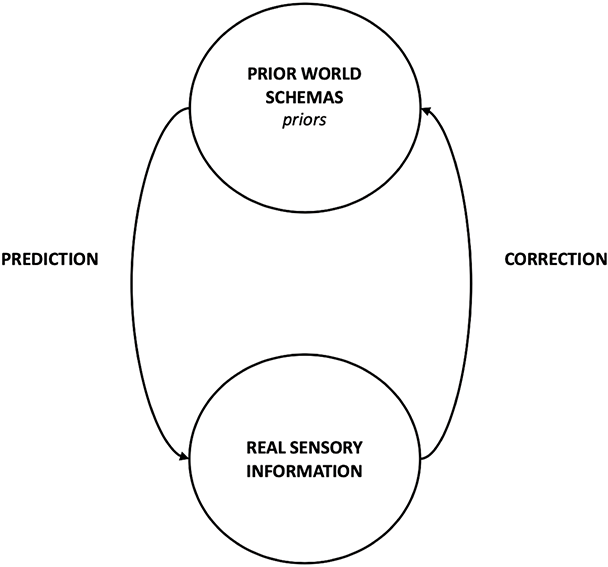

On the other hand, the design of digital behaviors is strongly influenced by the “free energy principle,” specifically its application to neuroscience known as the “theory of predictive coding,” which can be situated within the computational cognitive models of the human mind (Friston Reference Friston2010). This theory proposes that the brain is an adaptive system that is constantly generating and updating its models of the world (Bayesian brain). In other words, the brain generates predictions of the sensory information that will enter the system (anticipating incoming information without knowing what it will be), and once accessed, the actual sensory information is compared with the anticipated sensory information. If they do not match, the brain corrects the prediction error in such a way that it adapts and changes its internal representations of the world to also align with the new sensory information that has entered (see Figure 1.2). This point is critically important in the design of digital behavior, as the designer must consider this anticipatory mechanism as a key piece in the expectations of what contingencies will appear after the execution of a specific digital behavior.

Figure 1.2 Theory of predictive coding

The brain possesses prior schemas about how the world operates. According to these schemas, the brain “predicts” or anticipates what is expected to occur in the external environment. This prediction is compared to the actual sensory information, which represents events that have transpired. The actual sensory information is then compared with the prediction, and if there is a discrepancy, the prior world schema is adjusted. This adjustment is what is considered “learning” in the theory of predictive coding.

To anticipate user digital behavior, a tool already widely known in behavioral sciences will be utilized: functional behavior analysis. The distinction with this classic tool is that for the design of digital behavior, this approach will be adapted to incorporate certain theoretical elements from cognitivism. Cognitivism posits that mental representations modulate the relationship between the environment and behavior (Piccinini Reference Piccinini2020; Pickens & Holland Reference Pickens and Holland2004). In other words, expectations are considered based on the understanding that they belong to the realm of temporality. If someone learns that stimulus “X” is always followed by stimulus “Y,” in scenarios where “X” appears, the mental representation of “Y” will activate before the actual stimulus “Y” appears. This prior representation is what is considered an expectation (Reddy et al. Reference Reddy, Poncet and Self2015). In conclusion, digital behavior can be understood as a specific derivation of human behavior that occurs in a specific environment, namely the digital and/or virtual one.

1.4 Why Is It Important to Design Digital Behaviors?

Since the first commercial model of a personal computer in 1971 (Kenbak-1), the digital realm has pervaded all levels of our lives. This impact was particularly significant with the advent and development of smartphones in 1994, starting with IBM’s Simon. However, the digital world underwent a transformation only when Apple launched the iPhone 2 in 2008, featuring the first App Store. This was the first time a popular commercial brand allowed third-party developers to offer digital services using a smartphone platform.Footnote 5 Naturally, Apple would take a significant commission. Regardless of how we arrived at the current social and technological landscape, it is clear that smartphones and their myriad possibilities have captivated human civilization. This influence extends beyond culture to even alter our brains, thereby transforming us as individuals. While this section is not intended to delve into smartphone usage statistics, it is advisable to provide some brief data. In 2008, Apple’s marketplace, the App Store, started with 500 applications; by 2022, this number had ballooned to approximately 2.5 million. In contrast, Android and its Play Store had over 3.5 million apps. Between 2018 and 2022, it has been estimated that more than 194 billion apps have been downloaded from Android and Apple marketplaces (Aydin Gokgoz et al. Reference Aydin Gokgoz, Ataman and van Bruggen2021). Revenue generated from apps increased by 54 percent from 2016 to 2022, going from $101 billion to $156 billion in 2022 (Aydin Gokgoz et al. Reference Aydin Gokgoz, Ataman and van Bruggen2021). Notably, this market is dominated by a few; in 2019, 80 percent of all apps on the Apple Store and Google Play were created by 1 percent of developers (Inukollu et al. Reference Inukollu, Keshamoni, Kang and Inukollu2014). Downloading and using a technological service represents the most significant challenge for developers. Currently, the tool used for designing and enticing users to download and utilize mobile applications is the well-known Journey Map (Lavidge & Steiner Reference Lavidge and Steiner1961).

A Journey Map is tailored to the specific characteristics of marketplaces. The design and display of an app’s information on the platform (Apple Store or Google Play) are key elements affecting app discoverability and, consequently, the number of downloads. An app’s appearance among the top options in category-based searches is determined by factors such as its design, originality, media coverage, past revenue, downloads, app usage, and user retention (Engström & Forsell Reference Engström and Forsell2018). Most of these variables are beyond the control of developers and are known as “platform-controlled variables.” Once a user has discovered a list of relevant apps in the marketplace’s search page, they will assess which app to download. Their decision will be based on information such as the app’s icon, name, position in the list, average rating, number of reviews, and price. Reviews and ratings play a critical role in the evaluation for download as they reflect the value that other users have assigned to the app. As will be discussed later, this value assignment is a fundamental process for decision-making. All these factors are known as “user-side variables” and are also associated with app downloads. The evaluation occurs on the app’s description page, where further details are provided through user reviews, visual and verbal descriptions (either static or dynamic), and updates from the developers. The potential new user will assess if the app meets their needs and at what cost to decide whether the app is worth downloading.Footnote 6 The journey decision map concludes with the downloading of the app, while the same evaluation and decision-making process begins a new with other apps if the user chooses not to download (Aydin Gokgoz et al. Reference Aydin Gokgoz, Ataman and van Bruggen2021). Once an app is downloaded, there appears to be a critical timeframe to persuade the user to continue using it, as 77 percent of active app users are lost within the first three days (Inukollu et al. Reference Inukollu, Keshamoni, Kang and Inukollu2014). For example, technical glitches like freezing, crashing, slow responses, battery drainage, or excessive ads can lead to poor app reviews. But if these technical issues are resolved, what determines whether a user will form the habit of using an app? What variables contribute to app loyalty, and more importantly, can we design or anticipate which variables will enhance user engagement? Numerous studies focus on important elements in engagement for digital (Edney et al. Reference Edney, Ryan and Olds2019; Schwarz et al. Reference Schwarz, Huertas-Delgado, Cardon and Desmet2020) and virtual services (Leon-Dominguez Reference León-Domínguez2022), particularly those based on gamification (Darejeh & Salim Reference Darejeh and Salim2016; Welbers et al. Reference Welbers, Konijn, Burgers, de Vaate, Eden and Brugman2019). However, there is scant literature on the theoretical foundations or a methodology for original design elements that cause engagement. Studying how users interact with the app in a real-world scenario is an effective solution for improving the digital product, but the reality is that there is limited time to convince users that we offer the service they need.

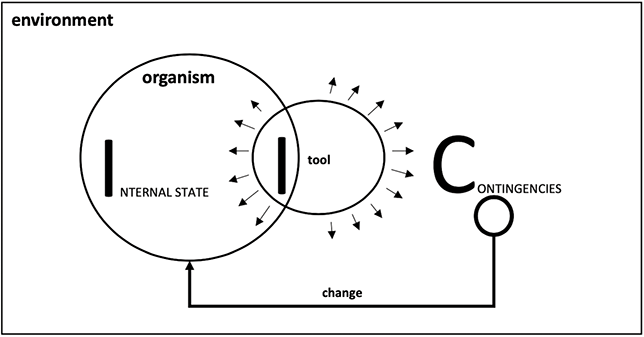

Engaging users can have a significant impact, not only on the user who fulfills a need but also on the economy of businesses that sponsor these apps or digital services. For instance, positive attitudes toward a specific business’s app result in a higher purchase frequency and an increase in loyalty to the business (Bellman et al. Reference Bellman, Potter, Treleaven-Hassard, Robinson and Varan2011; McLean et al. Reference McLean, Osei-Frimpong, Al-Nabhani and Marriott2020). Another factor that improves brand perception is if the apps are perceived as fun (van Noort & van Reijmersdal Reference van Noort and van Reijmersdal2022). In summary, companies that invest in app development (despite already having a website) not only see an improvement in sales, but customers also spend more (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Lobschat, Verhoef and Zhao2022; van Heerde et al. 2019a) and increase their engagement with the business (Boyd et al. Reference Boyd, Kannan and Slotegraaf2019; Cao et al. Reference Cao, Liu and Cao2018; Gill et al. 2017a). Nevertheless, assessing the economic return on investment in services that produce engagement is highly complex because often the primary objective is not to sell. Rather, it is to facilitate interaction between business-to-client or client-to-client, thereby promoting the formation of an emotional and psychological bond between the customers and the business (Gill et al. 2017b; Inman & Nikolova Reference Inman and Nikolova2017). One study estimated that apps with 100,000 users could generate a sales increase of 2.3 million dollars (van Heerde et al. Reference van Heerde, Dinner and Neslin2019b). This study demonstrates that the greatest increase in online purchases (up to 9.5 percent) was made by individuals who are far removed from physical stores and those who had never bought online and were given access to the app.Footnote 7 The main difference in buying behavior in a store and through the Internet is the mediation of a digital tool to interact with the business.Footnote 8 Operationally speaking, digital behavior is the interaction of an organism (in this case, humans) with the environment (which is largely cultural), mediated by a digital interface (software) contained in a technological tool (hardware), with the aim of obtaining certain rewards (hedonic and/or utilitarian) that satisfy a need (resolve imbalances in the internal state) (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 I-I-C Model

The passage of time and the environment can generate biochemical and psychological imbalances in an individual’s internal state, which require addressing. Often, the solution to these needs involves the use of technological tools with which the subject interacts and produces environmental changes. These environmental changes, contingent upon technological or digital behavior, can also provoke changes in the individual’s internal state. In this model, the individual who uses technology to solve a problem is considered a dynamic open system that experiences changes in response to the implementation of digital behaviors.

At the functional level, digital behavior occurs because the organism seeks to restore some form of physiological (e.g., hunger), psychological (e.g., self-esteem), or social (e.g., status) imbalance through interaction with various solutions provided by digital tools. For instance, when we are hungry, we order from Uber Eats; when we wish to improve our self-esteem, we use Strava or Strong; and if we want to enhance our social status, we upload a video to Instagram, YouTube, or TikTok. These needs, which we now address through technology, have always existed and are now fulfilled through the use of digital technology (see Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 A representation of an authentic newspaper advertisement from 1791 in Madrid, Spain

This advertisement illustrates how many needs are socially originated and that technologies merely act as intermediaries for their fulfillment. The text has been translated into English.

At this point, it is crucial to emphasize that many of the new terms frequently appearing in marketing and other disciplines related to app development are nothing more than substitutes for concepts extensively understood and studied in psychology. Terms like Growth Hacking, Customer Success, or Customer Effort Score are merely some examples that offer a biased and partial view of much more complex psychological concepts. The issue is not that these concepts are taught or that they are given much more dazzling names, but that the underlying basic psychological processes are not being taught. Consequently, they are inflexible and not generalizable to other contexts. If we do not understand the “why,” we cannot adequately adapt them to the specific characteristics of users and businesses. For example, Customer Success consists of ongoing reinforcement programs, and Customer Effort Score is a type of negative reinforcement, which removes aversive events such as cognitive effort and the time a customer usually requires to make a purchase. Those who understand what negative reinforcement is and why it works can generalize the effects of these mechanisms to other contexts beyond effort and time, thus generating a powerful impact on sales. For instance, a digital behavior expert could invent a concept like Customer Skill Improvement, a chained (or sequential compound) reinforcement program that increases my users’ skills in complex digital behaviors by breaking the behavior into intermediate steps and reinforcing the completion of each. This new technique could be applied to acquiring complex skills, such as using programs like AutoCAD or Garageband. Many nonprofessional users may give up due to its complexity, but if a company creates a Customer Skill Improvement program, it could enhance the engagement of a large portion of those users who want to learn but give up due to its difficulty. Therefore, understanding the behavioral and cognitive principles that operate on certain behaviors should be a technical imperative, not only to create more ergonomic digital services for users, but also to avoid certain actions by companies pressed by the need to produce profits when they ingeniously create reward management systems that “unintentionally” may encourage pathological behaviors in the use of technologies. An example is companies that pay people to directly play various video games. Such promotions aim “innocently” to create a community of players for certain video games, attracting other players as this artificially created community can generate interactions with new players and form emotional bonds. In this way, they manage to exponentially increase the number of players. Although this system pursues a corporate purpose, it may foster compulsive behavior to certain video games (Feiner Reference Feiner2023; Flayelle et al. Reference Flayelle, Brevers, King, Maurage, Perales and Billieux2023). So much so that already certain massively consumed and successful platforms like Instagram are implementing new features like “Take a Break.” This Instagram feature aims to protect adolescents from compulsive use of the platform by setting time limits and offering alternative behaviors, such as listening to a favorite song or writing about what they are thinking, among other options. It is possible that such new functionalities arise from the multiple demands that are occurring on these types of applications, which implement behavioral principles of psychology unchecked (Crosscut 2020). Therefore, the subspecialty of Digital Behavior Design as a branch of Human Factors and Engineering Psychology, and framed within the Behavioral and Cognitive Sciences, emerges as a social need for ergonomic design of technological and digital tools. The professionalization of this sub-specialty must develop from the field of psychology, although other professionals may also be interested, such as user experience designers, interface designers, graphic designers, product engineers, and computer engineers.