The past decade has seen the rise of a new dimension in the delivery of psychosocial interventions: the study of psychotherapy across race, religions and cultures, or ‘ethnopsychotherapy’ (Naeem Reference Naeem, Phiri and Munshi2015a). This article will focus on cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) across cultures, which we have dubbed ‘ethno-CBT’. This interest in the study of racial, religious and cultural factors in the application of psychotherapies is hardly surprising considering recent changes in political, economic, social and health systems worldwide.

Globalisation is making many countries culturally, religiously and racially more diverse. This places an enormous responsibility on healthcare systems to ensure that health disparities are addressed by providing equitable, culturally responsive, appropriate and effective clinical services so that practice is relevant to the cultural backgrounds of the diverse populations. It has been suggested that inability to provide culturally competent and culturally adapted healthcare services leads to a disparity in services for people from ethnic minority cultures that in turn leads to poor access to available services, poor outcomes and increasing costs to society (Kirmayer Reference Kirmayer2012). There is a drive towards improving equity and equality in healthcare (Culyer Reference Culyer and Wagstaff1993) in most healthcare systems.

Furthermore, the improving economic situation in many countries, especially in Latin America and Asia (UN Economic Analysis & Policy Division 2018), together with raised awareness of evidence-based interventions, has led to an increase in demand for evidence-based health interventions, including psychosocial interventions. Unlike most surgical or medical interventions, psychosocial interventions are underpinned by the social, cultural, political and religious values of their developers: hence, the interest in studying cultural factors in delivering psychosocial interventions in these countries.

Why should psychosocial interventions be culturally adapted?

The literature points out that cultural differences can influence the process of psychosocial interventions (Bhugra Reference Bhugra and Bhui1998; Sue Reference Sue, Zane and Nagayama Hall2009; Bhui Reference Bhui2010; Barrera Reference Barrera, Castro and Strycker2013; Rathod Reference Rathod and Kingdon2014; Edge Reference Edge, Degnan and Cotterill2018). Several decades ago it was noted that ‘because white males from the West developed most psychotherapy theories they may conflict with the cultural values and beliefs of clients from Non-Western background’ (Scorzelli Reference Scorzelli and Reinke-Scorzelli1994).

Laungani argued that Asian and Western cultures differ in four core value dimensions (Laungani Reference Laungani2004): individualism–communalism, cognitivism–emotionalism, free will–determinism and materialism–spiritualism. He observed that Asians are more likely to be community oriented, to make less use of a reasoning approach, can be inclined towards spiritual explanations and prone to a deterministic view of life. The monotheistic religions view some aspects of life as predetermined and this belief controls the way people think. Hindus believe in a similar ‘karma’. Buddhism, on the other hand, takes a nonlinear view of life. Li et al (Reference Bhugra and Bhui2017) have discussed the impact of teachings of Confucianism (respect for familial and social hierarchy, filial piety, discouragement of self-centredness, emphasis on academic achievement and the importance of interpersonal harmony) and Taoism (a simple life, being connected with nature and non-interference in the course of natural events) on the mental and emotional health of Chinese individuals.

Fierros & Smith (Reference Fierros and Smith2006) point out that many persons of Latino (Hispanic) background have strong religious beliefs and these can have a profound impact on their view of mental illness as well as its management, which in turn affects how the therapist is viewed. An associated concept is that of fatalism, which is the belief that divine powers are governing the world and that an individual cannot control or prevent adversity. Similarly, some Latinos see their mental or emotional problems as being caused by evil spirits or witchcraft (Fierros Reference Fierros and Smith2006). A qualitative study from Montreal exploring the health beliefs of persons of Caribbean origin reported a belief in the curative power of non-medical interventions, most notably God and, to a lesser extent, traditional folk medicine (Whitley Reference Whitley, Kirmayer and Groleau2006). Karenga's Nguzo Saba, which is comprised of seven humanistic principles originating in Africa (unity, self-determination, collective work and responsibility, cooperative economics, purpose, creativity and faith), are values of African culture which contribute to building and reinforcing community among African-Americans. (Karenga Reference Karenga, Karenga and McAdoo2007).

What is culture?

Although the term ‘culture’ is part of our everyday vocabulary, there is still a great deal of uncertainty about just how the word itself, let alone the phenomenon to which it refers, should be understood (Parveen Reference Parveen2001). Hence, for example, in everyday use, the terms ‘culture’, ‘ethnic group’ and ‘race’ are regularly used as if they were wholly interchangeable. There are different ways of defining culture. For example, Triandis prefers a broad-brush approach, with the result that he includes the physical as well as the subjective aspects of the world in which we live in his definition (Triandis Reference Triandis and Lambert1980). He argues that environmental features such as roads and buildings can be seen as constituting the ‘physical’ elements of culture, as opposed to myths, values, attitudes and so forth, which he identifies as its more ‘subjective’ elements.

Fernando suggests that ‘in a broad sense, the term culture is applied to all features of an individual's environment, but generally refers to its non-material aspects that the person holds in common with other individuals forming a social group’ (Fernando Reference Fernando1991). In contrast to this all-inclusive approach, Reber defines culture much more specifically, as ‘the system of information that codes how people in an organised group, society or nation interact with their social and physical environment’ (Reber Reference Reber1985). In arguing that cultures are systems and structures that people must learn, he identifies culture quite explicitly as a cognitive phenomenon. However, we should keep in mind the physical manifestations of this phenomenon.

According to anthropologists, culture has three components: things or artefacts; ideas and knowledge; and patterns of behaviour. They also suggest that the most fundamental concept of human culture, and the one that essentially distinguishes humans from animals, is the use of symbols. It has been suggested that the term ‘culture’ as it is used by anthropologists has its origin in German Romanticism and the idea of the Volksgeist (the ‘spirit’ of people) (Hendry Reference Hendry and Underdown2012). The term diffused into British and later into American anthropology and it denotes the totality of the humanly created world, from material culture and cultivated landscapes, via social institutions (political, religious, economic, etc.), to knowledge and meaning. Culture has also been defined as ‘the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, and […] it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs’ (UNESCO 2002: p. 62). We prefer this last definition as it comes along with a declaration by UNESCO that accepts cultural diversity, promotes cultural pluralism, delineates cultural diversity and asserts that it presupposes the respect for human rights. Most importantly, this definition does not limit culture to race, religion or nationality. These values underpin the principle of cultural adaptation of evidence-based psychosocial interventions to persons of diverse cultural backgrounds. However, with the Westernisation of many non-Western countries, and with ready access to global social and electronic media, some of these concepts need reconsidering.

What is cultural adaptation?

Cultural adaptation of CBT can be defined as ‘making adjustments in how therapy is delivered, through the acquisition of awareness, knowledge, and skills related to a given culture, without compromising on theoretical underpinning of CBT’ (Naeem Reference Naeem2012a).

Working under the assumption that individuals from non-Western cultures might have different sets of beliefs, values and perceptions, some therapists in the USA have developed guidelines for adaptation of psychosocial interventions on the basis of their work with people from non-Western backgrounds (Bernal Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995; Tseng Reference Tseng2004; Hwang Reference Hwang2006). However, these first guidelines describe therapists' personal experiences of working with Latino and Chinese patients and address broader philosophical, theoretical and clinical concerns. Furthermore, the guidelines did not directly result from research addressing cultural factors and, as far as we are aware, did not form the basis of adapted therapy that had passed the test of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). In general, the literature on guidance of this kind for cognitive therapists is limited (Hays Reference Hays and Iwamasa2006).

Why focus on CBT?

We selected CBT for several reasons: first, it is short-term, focused, cost-effective and evidence-based; second, there was at least some literature describing its use with individuals from collectivist cultures; and third we were trained in CBT. However, it should be emphasised that there are notable examples of cultural adaptation of other psychosocial interventions, such as family therapy (Davey Reference Davey, Kissil and Lynch2013; Edge Reference Edge, Degnan and Cotterill2018), dialectical behaviour therapy (Ramaiya Reference Ramaiya, Fiorillo and Regmi2017), interpersonal psychotherapy (Brown Reference Brown, Conner, McMurray, Bernal and Domenech Rodriguez2012) and mindfulness (Sipe Reference Sipe and Eisendrath2012) (although in the case of mindfulness, an Eastern tradition, the adaptation took place for Western culture).

Furthermore, CBT is recommended by national organisations in most high-income countries, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK and the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in the USA for a variety of emotional and mental health problems.

Finally, an important aspect of cognitive therapy is that it is tailored to the individual's needs. A collaborative negotiated approach can help therapists understand and adapt to the culture of the patient, provided that they know how to read cultural cues. This makes CBT the ideal candidate for cultural adaptation. In a recent review of meta-analyses of culturally adapted interventions, we found that CBT was the most commonly used culturally adapted therapy (Rathod Reference Rathod, Gega and Degnan2018).

CBT and culture

It has been suggested that CBT is as value-laden as any other psychotherapy (Hays Reference Hays and Iwamasa2006). CBT involves exploration of core beliefs and unhelpful patterns of thinking and attempts to modify them. People with depressive illness and anxiety usually have beliefs about self, others and the world that are unhelpful. Such core beliefs, underlying assumptions and even the content of automatic thoughts might vary with culture (Sahin Reference Sahin and Sahin1992).

One study from India reported that 82% of psychology students felt that principles underlying cognitive therapy conflicted with their values and beliefs (Scorzelli Reference Scorzelli and Reinke-Scorzelli1994). Of these, 46% said that the therapy clashed with their cultural and family values and 40% described conflict with their religious beliefs. Our own study explored whether the concepts underpinning CBT were consistent with the personal, family, sociocultural and religious values of university students in Pakistan. Although there was little disagreement with the principles of CBT in relation to personal values, some controversy existed for family, social and, most importantly, religious values (Naeem Reference Naeem, Gobbi and Ayub2009a). Qualitative interviews with mental health professionals in England (Rathod Reference Rathod, Kingdon and Phiri2010), Pakistan (Naeem Reference Naeem, Gobbi and Ayub2010), China (Li Reference Li, Zhang and Luo2017) and the Middle East (details available from authors on request) revealed the need for cultural adaptation of CBT for persons of non-Western origin.

An evidence-based framework for culturally adapting CBT

As mentioned earlier, previous adaptation frameworks were not developed using a robust methodology or tested through RCTs. During the past few years our group has developed and tested culturally sensitive CBT using mixed-methods research (Rathod Reference Rathod, Kingdon and Phiri2010, Reference Rathod, Phiri and Harris2013; Naeem Reference Naeem, Phiri and Munshi2015a, Reference Naeem, Gul and Irfan2015b, Reference Naeem, Saeed and Irfan2015c, Reference Naeem, Phiri and Nasar2016; Li Reference Li, Zhang and Luo2017).

Methodology

We started with open-ended interviews to gather information that can be used in the development of more or less precise guidelines for adaptation (Naeem Reference Naeem, Gobbi and Ayub2009a, Reference Naeem, Ayub and Gobbi2009b, Reference Naeem, Gobbi and Ayub2010, Reference Naeem, Ayub and Kingdon2012b). Over the years these interviews evolved into semi-structured interviews that can be conducted by less experienced researchers under supervision (Naeem Reference Naeem, Sarhandi and Gul2014a; Li Reference Li, Zhang and Luo2017). We have typically involved patients, their carers, therapists or mental health professionals working with them, and community leaders. The qualitative work explored themes such as beliefs held by patients, carers and community leaders about a given problem, its causes and treatment, especially non-medical treatments, and included patients' experience of any non-pharmacological help received. Interviews with professionals focussed on their experiences, barriers and the solutions they used, if any. A name-the-title technique (Naeem Reference Naeem, Ayub and Gobbi2009b) was used to find equivalent terminology, rather than using literal translations. A feasibility pilot study was conducted to determine whether the adapted therapy was acceptable. Finally, a larger RCT was conducted to determine the therapy's effectiveness.

The process of adaptation

The process of culturally adapting the CBT starts with gathering information from the literature, and the experts in the area. Next, views of the different stakeholders are explored using a qualitative methodology. This information is then analysed to develop guidelines that can be used to adapt an existing CBT manual to deliver a culturally adapted CBT. The therapy material is then translated and field-tested again to allow further adjustments and refinements. The steps of this process are summarised in Fig. 1).

FIG 1 The process of culturally adapting cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT).

The focus of adaptation

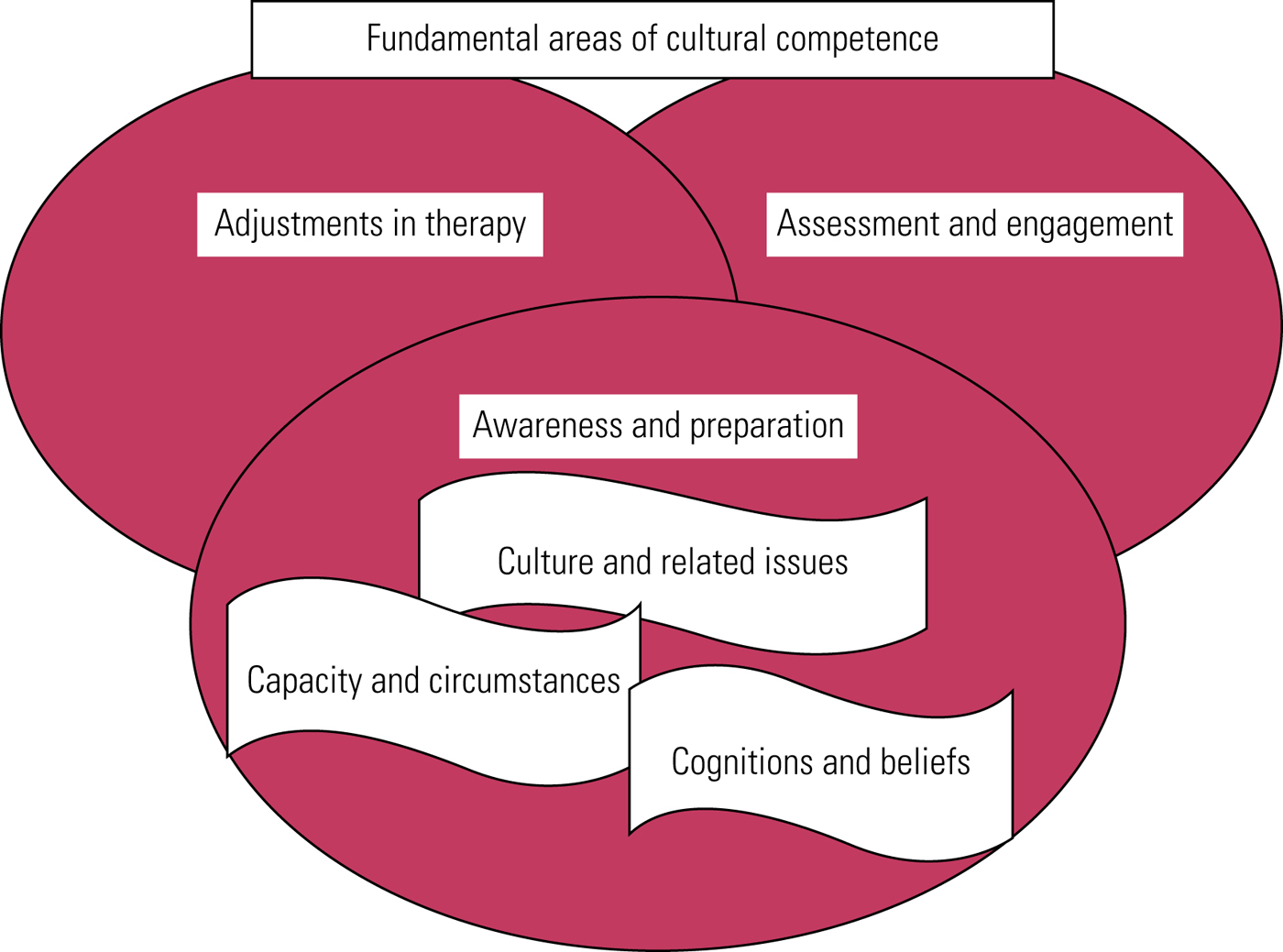

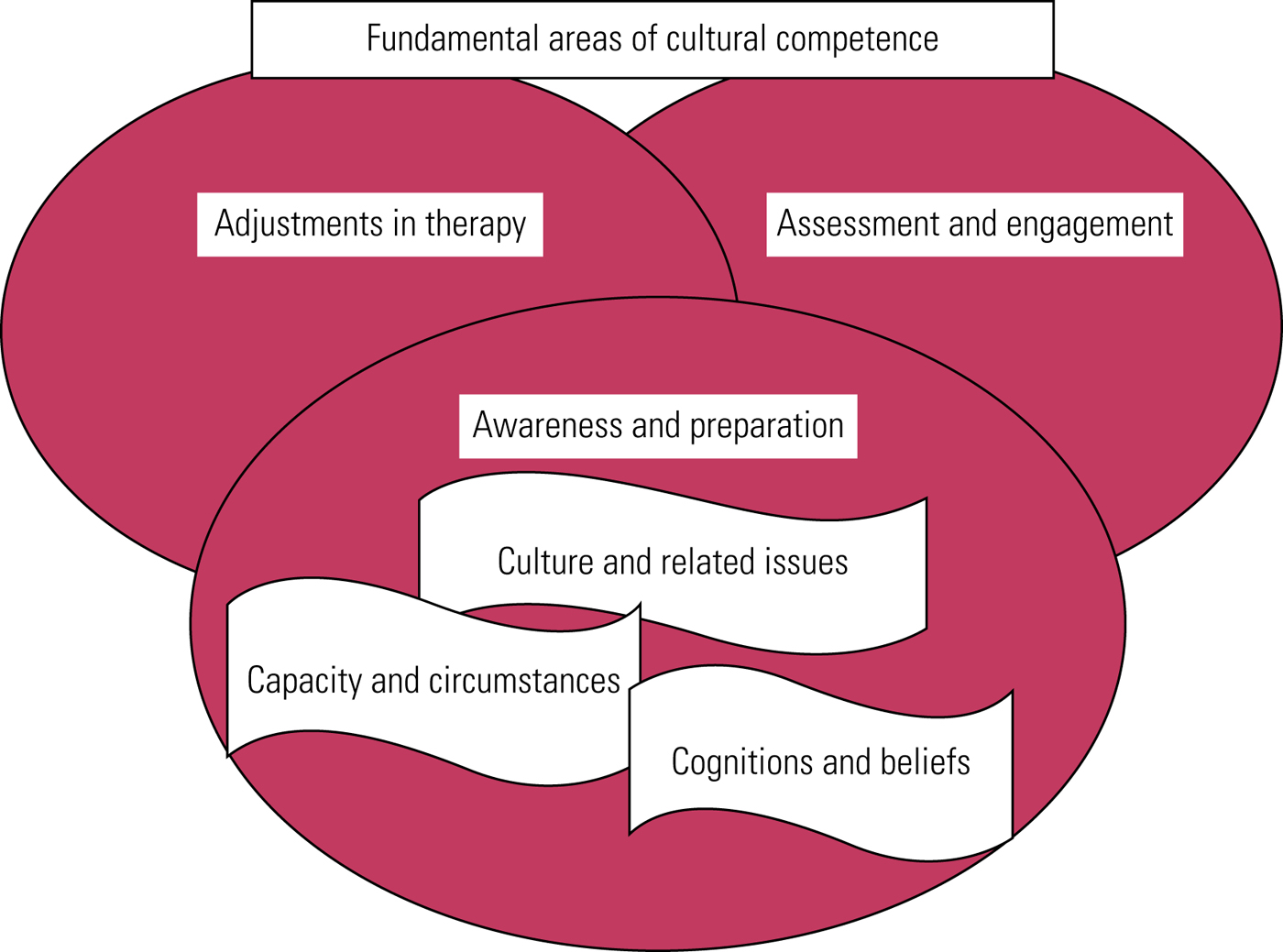

To effectively adapt CBT for a given culture, the following areas of cultural competence (the triple-A principle) must be covered:

• awareness of relevant issues and preparation for therapy

• assessment and engagement

• adjustments in therapy techniques (‘technical adjustments’).

Awareness of relevant cultural issues, in turn, involves:

• matters related to culture, religion and spirituality

• consideration of the capacity and characteristics of the healthcare system

• the cultural context of cognitions and (dysfunctional) beliefs.

The fundamental areas of cultural competence are outlined in Fig. 2.

FIG 2 Fundamental areas of cultural competence.

Lessons learned from our research

Awareness of cultural knowledge and preparation for therapy

The therapist's first step in preparation for working with a patient from a different culture should be to do some homework before meeting the patient. For example, the therapist could talk to someone from the same culture or look for information in the literature. Here we will describe some relevant areas only briefly, as detailed discussions are provided in the publications mentioned.

Culture, religion and spirituality

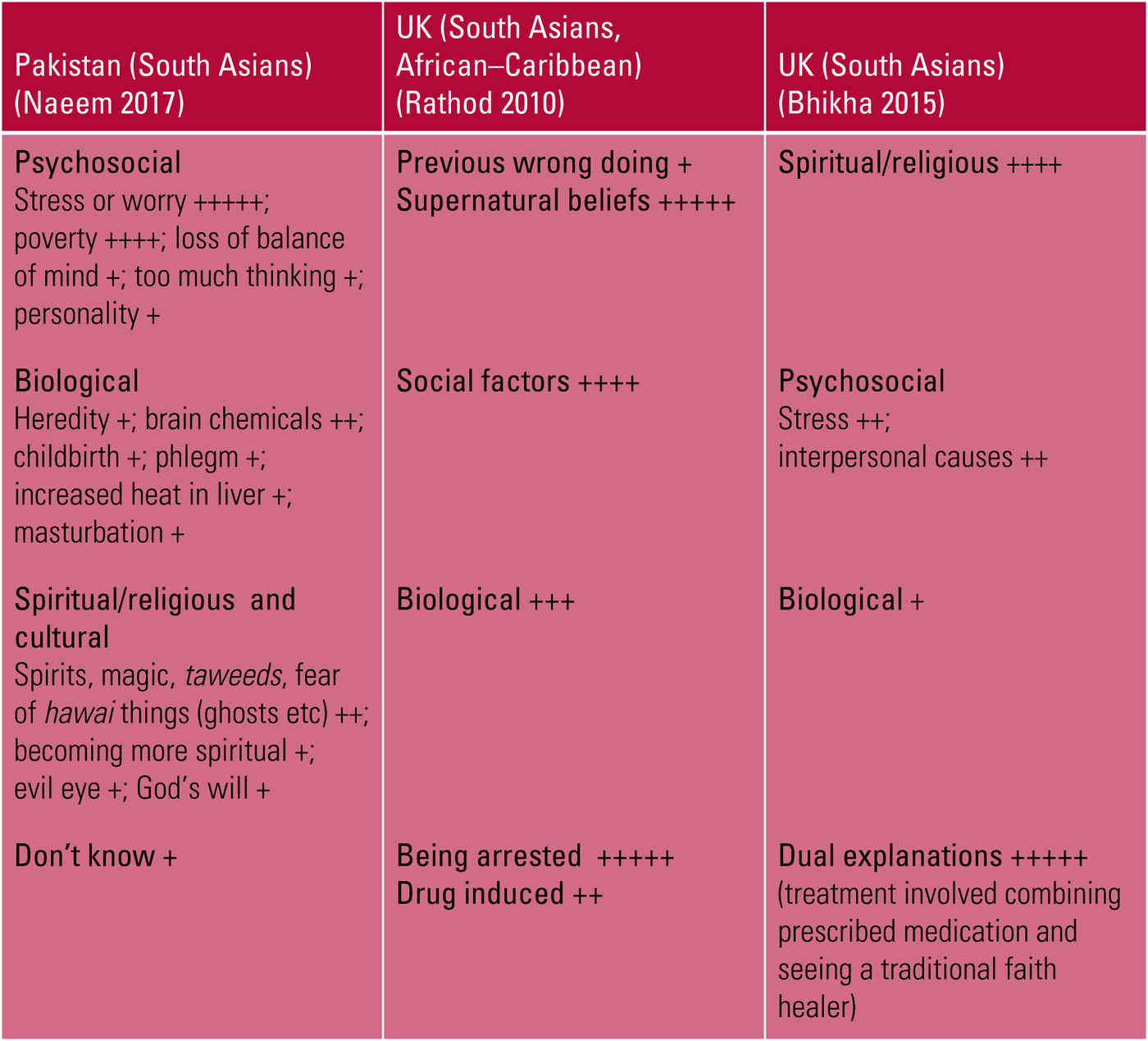

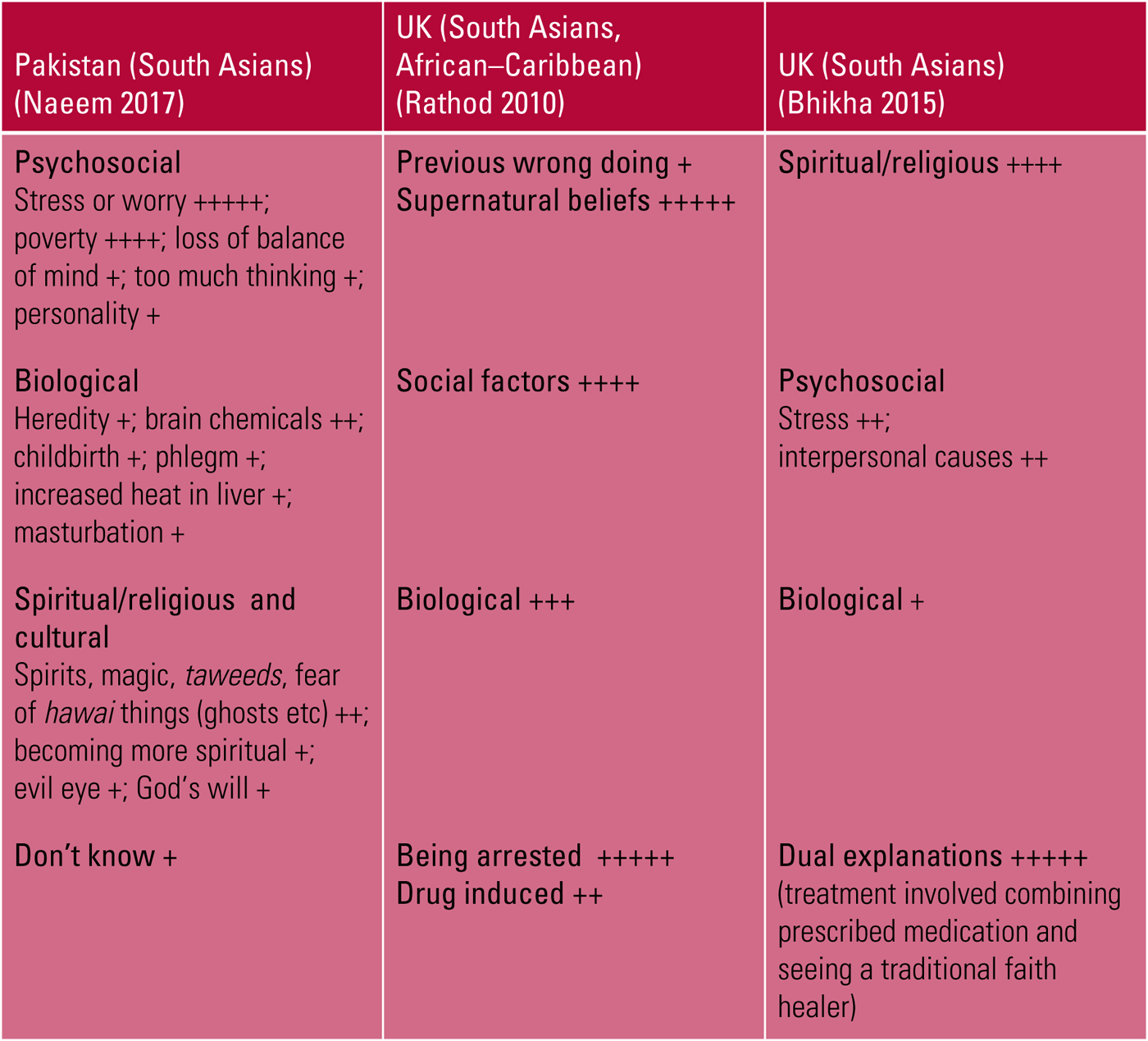

Patients from many non-Western cultures use a biopsychosocial–spiritual model of illness (Fig. 3) (Naeem Reference Naeem, Phiri and Nasar2016). This model influences their belief systems, especially those related to health, well-being, illness and help-seeking in times of distress. Culture and religion influence beliefs about the ‘cause–effect relationship’ (Razali Reference Razali, Khan and Hasanah1996; Cinnirella Reference Cinnirella and Loewenthal1999). For example, the cause of an accident might be described as the ‘evil eye’ or ‘God's will’. People often use religious coping strategies when dealing with distress (Bhugra Reference Bhugra, Bhui and Rosemarie1999). However, it should be emphasised that culture, religion and spirituality can also give rise to myths and stigma associated with mental illness (for example, some Muslims believe that not being a good follower can make a person depressed (Naeem Reference Naeem2012a)). Most important, beliefs about the causes of mental illness can influence the choice of treatment and help-seeking pathways (Lloyd Reference Lloyd, Jacob and Patel1998).

FIG 3 Explanatory models of psychosis among different ethnic groups.

Language

It is essential to consider language barriers. Assertiveness can be used as an example here. Many non-Western cultures do not have the concept of assertiveness. In patriarchal cultures individual assertiveness might be inappropriate in certain situations. However, patients can be taught assertiveness techniques in a culturally sensitive manner, for example learning the ‘apology technique’, in which they use phrases such as ‘With a big apology, I would like to seek your permission to disagree’ (Hays Reference Hays and Iwamasa2006; Naeem Reference Naeem, Ayub and McGuire2013).

Healthcare systems: accessibility and capacity

Women from some cultures are less likely to attend therapy as they might need permission from a man and might be dependent on men to be brought to the clinic (Shaikh Reference Shaikh and Hatcher2005). When working with female patients, it would therefore help to engage the accompanying man or the family during the assessment and to psychoeducate them. In many low- and middle-income countries where psychiatric facilities are limited to bigger cities, distance from the treatment facility might be a barrier for all patients (Naeem Reference Naeem, Gobbi and Ayub2010; Li Reference Li, Zhang and Luo2017). Availability of culturally sensitive therapists can be a further systemic barrier. Patients' knowledge of the healthcare system, available treatments and their likely outcomes are key factors influencing service utilisation and engagement.

Cognitive errors and dysfunctional beliefs

Dysfunctional beliefs vary across the cultures. Research from Turkey and Hong Kong, for example, provides evidence of such variations (Sahin Reference Sahin and Sahin1992; Tam Reference Tam, Wong and Chow2007). Typical examples of beliefs that might be considered dysfunctional by a Western therapist include feeling that one must depend on others, please others, submit to the demands of those in authority and sacrifice one's own needs for the sake of family (Laungani Reference Laungani2004; Chen Reference Chen and Davenport2005; Naeem Reference Naeem, Ayub and McGuire2013).

Assessment

Being aware of the factors mentioned above can guide a culturally sensitive assessment. The therapist can begin by exploring the patient's beliefs about mental illness, healing and healers. For example, they might ask what the patient or their family thinks is the cause of the illness and seek the patient's opinions about spiritual and religious causes of symptoms. Next, the therapist can explore the patient's knowledge and expectations of the healthcare system and their involvement with any healers (e.g. faith healers, religious healers, magicians and herbalists). Assessing somatic concerns is important, as some patients with anxiety or depression present with physical complaints (Bridges Reference Bridges and Goldberg1987). The initial assessment can also include exploration of stigma, racism and feelings of shame and guilt. Finally, structured assessment tools can be used to assess the patient's beliefs about illness and its treatment (Lloyd Reference Lloyd, Jacob and Patel1998) and their level of acculturation (Frey Reference Frey and Roysircar2004; Wallace Reference Wallace, Pomery and Latimer2010; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014).

Being aware of explanatory models of mental illness, such as the biopsychosocial (Kinderman Reference Kinderman and Kinderman2014) and the spiritual models (Verghese Reference Verghese2008), and their components will be helpful. Just like their Western counterparts, people in non-Western cultures believe in many aspects of the biopsychosocial model. For example, South Asians have a strong belief in genetic predisposition to mental illness and may avoid marrying into families with a history of mental illness. This leads to stigma and even hiding of those with mental illness. Weakness of personality and character have also been described as causes of mental illnesses (Naeem Reference Naeem, Ayub and Kingdon2012b, Reference Naeem, Habib and Gul2014b). Many people in Pakistan believe that depression is more common among those who are not practising Muslims (Naeem Reference Naeem, Phiri and Munshi2015a) or that it can be caused by magic spells (Rathod Reference Rathod, Kingdon and Phiri2010; Naeem Reference Naeem, Habib and Gul2014b). It therefore becomes an integral part of the therapy to educate the patient and their family about biopsychosocial causes of illness. We also advise therapists to seek information from religious scholars or even arrange a meeting with a religious scholar when a spiritual or magical cause is put forward. Extreme caution is required in dealing with spiritual and magical beliefs as they are usually underpinned by the person's religious belief system.

Engagement

High rates of drop-out from therapy have been reported among patients from non-Western cultures (Rathod Reference Rathod and Kingdon2014). The first few sessions are always significant. Some patients expect immediate relief from troubling symptoms, so focusing on symptom management at the start of therapy can improve engagement and boost the patient's confidence in the therapist. The following pointers might improve engagement.

Paying attention to non-verbal cues

In most non-Western cultures therapists are seen to be in a position of authority. So a patient might not openly disagree with their therapist. Instead, they might express their disagreement by not turning up for the next appointment. Therapists should therefore pay attention to the patient's body language and subtle changes in language and expression.

Using examples from therapy as evidence

Patients like to know how successful their therapist is. We therefore recommend discussion of similar cases and how the individuals concerned benefitted from therapy, in addition to describing evidence from research.

A personal connection

Patients from many non-Western cultures like a personal touch. Use of religious, spiritual or cultural examples can help. Offering food or gifts to therapists is normal, and rejecting these might be considered rude.

Family as a valuable resource in therapy

Although the family can be a cause of conflict and stress and even a barrier to access to or engagement with therapy, it can be a valuable resource to help and support patients. Tactfully involving the family, after an initial discussion on setting rules and boundaries and once the patient has consented, can improve engagement. The family can especially assist in information-gathering, therapy (by being ‘co-therapists’), supporting the patient and bringing the patient back for follow-up. Valuable lessons in this area can be learned from culturally adapted family therapy (Edge Reference Edge, Degnan and Cotterill2018).

Adjustments to the therapy process and techniques

Use of stories

Experienced healers from non-Western cultural backgrounds use stories to convey their messages. Stories can be compelling when used along with images in handouts (Naeem Reference Naeem, Ayub and McGuire2013, Reference Naeem, Sarhandi and Gul2014a).

Therapy style

A more directive counselling style might be helpful to start. As therapy proceeds a collaborative approach can be used. The non-Western model of spiritual and emotional healing is a saint or a guru who gives sermons, as opposed to a professional teaching through ‘Socratic dialogue’ as is preferred in individualistic Western cultures. Patients from non-Western cultures often feel uncomfortable if Socratic dialogue is used without sufficient preparation. They do not expect therapists to ask questions – therapists are supposed to provide guidance or solutions to their problems. Consequently, asking questions using a Socratic dialogue can create serious doubts about the therapist's competence.

Homework

Homework tasks can be a significant problem in Western cultures. For patients from many non-Western cultures, it is even a bigger problem. Engaging the family can help, as can less use of the written word. For example, the patient could be given audio tapes of the session or of bibliographic material, and encouraged to use beads or counters, which are commonly used in Asia and Africa, rather than pen and paper to count negative thoughts.

Use of the cognitive model

Literal translations of CBT terminology might not help. For example, in teaching about cognitive errors it might be better to explain the concept (e.g. black and white thinking) and to ask the patient what they call this style of thinking in their language. This will help them discover an idiom of distress that is more relevant to them. Focus on teaching the patient to recognise their thoughts. It might help to define ‘thoughts’ as the images the person has in their mind or as their self-talk – in our experience, patients find ‘self-talk’ the easiest description to follow. We advise therapists to include physical symptoms in thought diaries to help patients to see the link between thoughts and physical symptoms (Naeem Reference Naeem, Phiri and Munshi2015a).

Therapy techniques

Patients from non-Western cultures often find behavioural methods (behavioural activation, behavioural experiments) and problem-solving particularly useful. Problem-solving can be used without any changes or adjustments and is especially useful where depression is associated with social and financial difficulties. Muscle relaxation and breathing are favourite among non-Western patients. Breathing exercises are part of many religious and spiritual traditions and are commonly practised in non-Western cultures.

Structural factors in therapy

In our experience, patients from non-Western cultures are much more likely than Western patients to want to be informed of the number of sessions, structure and focus of the therapy and some information on what will happen in sessions in advance. This is because they are concerned about the cost – even those receiving therapy through the public health sector have to think about their travel costs and days off work because of the lack of a benefit system – and because they might not have heard of therapy, unlike their Western counterparts. Involving family members can be useful, particularly as they often want to know what the therapist is going to talk to the patient about.

Practical application of the adaptation framework: barriers and pitfalls

Additional factors might need careful consideration. For example, it is obviously wrong to assume that everyone from a given culture is the same or has identical characteristics. There must be flexibility in applying culturally adapted therapy. Migrants, although sharing some commonalities with their culture of origin, might have wide variations. Racial tensions, experiences related to migration, and political and social systems in the host culture should be taken into consideration. There might be wide variations between the first- and second-generation immigrants. An assessment of acculturation might help. It might also be helpful to explore trauma, shame, guilt and stigma with all patients. Finally, when working with patients from a different background, therapists should be aware of their own assumptions, biases and prejudices.

The way forward

We are still at the start of an emerging field in psychotherapy, and we will learn more over time. There is a need to further adapt therapies for patients from different religious, racial and cultural backgrounds, both in their native land and among migrant populations. Further comparisons and contrasts can help identify the commonalities and differences. As far as we are aware, only limited data are available on comparisons of culturally adapted and non-adapted therapies (Kohn Reference Kohn, Oden and Muñoz2002; Hwang Reference Hwang, Myers and Chiu2015).

No information is available on the cost-effectiveness of culturally adapted therapies. Use of self-help is a neglected area in this field. This is especially true for the use of self-help through social and electronic media.

Finally, adapting therapy can improve engagement and outcomes but it will be of little assistance until and unless barriers to accessing treatments in general and adapted therapies in particular are addressed.

Conclusions

The study of cultural factors in psychotherapy – ethnopsychotherapy in general, and also the ethno-CBT discussed in this article – is an emerging field. CBT has been adapted for various ethnic minority groups in the West and local populations in non-Western cultures through a series of steps and using mixed-methods research. Only minor adjustments are required in CBT. The focus of adaptation should be on addressing barriers that can hinder assessment, engagement and the therapeutic process. The overall aim should therefore be to understand the patient's cultural background and to make appropriate changes to how therapy is delivered and to the techniques used, without altering the theoretical underpinnings of CBT. Further research is required to move the field forward. However, without improving access to services these adaptations might not be beneficial.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge colleagues and collaborators over the years, and especially Dr Muhammad Irfan, Dr Mirrat Gul, Dr Madeeha Latif, Mr Muhammad Aslam and our mentor Dr David Kingdon. We also want to express our gratitude to our research collaborators in England, Pakistan, China and the Middle East and, most importantly, to the patients, carers and mental health professionals who participated in numerous qualitative and quantitative studies.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 ‘Ethno-CBT’ can be described as:

a the study of racism in CBT

b the study of effectiveness of CBT in different cultures

c the study of CBT across race, religion and cultures

d applying CBT only to those from a White background

e study of the limitations of CBT in Asian populations.

2 It has been argued that psychosocial interventions should be culturally adapted because:

a people from some cultures are more psychologically minded than others

b governments in low-income countries do not approve of Western therapies

c somatisation only occurs in Black and minority ethnic populations

d people from non-Western cultures are not used to psychological interventions

e modern psychosocial interventions are underpinned by Western values.

3 Cultural adaptation of CBT can include:

a making adjustments in how therapy is delivered to make CBT more acceptable to another culture without compromising its theoretical underpinnings

b making adjustments in the theory and application of CBT to make it more acceptable to another culture

c training therapists in cultural sensitivity

d improving access to CBT services for people from Black and minority ethnic populations

e making adjustments in how therapy is delivered and adding indigenous therapies.

4 Which of the following is not a step in culturally adapting CBT?

a applying for resreach funding

b literature review and discussions with experts, plus qualitative studies to gather information from stakeholders (e.g. patients, carers, mental health practitioners and service managers) about their experiences and views

c producing guidance on adapting a CBT manual

d translation and adaptation of therapy material to produce a modified manual

e field-testing the modified manual and further refinement of the guidelines.

5 As regards the application of culturally adapted CBT:

a patients from non-Western cultures often use a biopsychosocial–magical model of mental illness

b gender does not influence engagement with therapy across cultures

c cognitive errors and dysfunctional beliefs are the same across cultures

d the family should be discouraged from attending therapy in many non-Western cultures

e patients from non-Western cultures find behavioural techniques and problem-solving particularly useful.

MCQ answers

1 c 2 e 3 a 4 a 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.