Introduction: Queering Minority Language Revitalisation

The purpose of this Element is to analyse the role of queer speakers of minoritised languages in the ongoing efforts to stabilise those languages in contemporary society. The minoritised languages in question are indigenous varieties that continue to be spoken to varying degrees in settings ranging from Ireland to Catalonia to New Zealand, in contact with hegemonic languages such as English or Spanish. The language revitalisation paradigm that emerged in European peripheral sociolinguistics in recent decades focused on protecting and expanding communities of such minoritised languages, with priority often given to the reproduction of ‘native speakers’ based on intergenerational transmission within the heterosexual nuclear family. In parallel with the work of ‘sociolinguists for language revival’ (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Pujolar and Ramallo2015: 11), language policy measures in these areas frequently focused on supporting intrafamily transmission or on established school-based immersion programmes where children could acquire communicative competence. Joshua Fishman’s seminal work Reversing Language Shift (Reference Fishman1991), with its emphasis on intergenerational transmission to children in the family-neighbourhood-community nexus, essentially attempts to reconstruct communities of native speakers. It was highly influential in the 1990s in language revitalisation circles around the world, particularly in Western Europe. Scholars such as Romaine (Reference Romaine2006) and McEwan-Fujita (2020) have since problematised the model, the latter pointing out that ‘families are not homogenous sites of language transmission’ (McEwan-Fujita, Reference McEwan-Fujita and McEwan-Fujita2020: 294) and convincingly showing that (intergenerational) transmission involves ‘not only parent-child and grandparent-grandchild relations, but also many other kinds of language socialisation relationships … Adults can socialise other adults and can socialise children of all ages in many capacities (extended family member, family friend, teacher, coach, lunchroom supervisor, religious leader, store clerk, etc.)’ (McEwan-Fujita, Reference McEwan-Fujita and McEwan-Fujita2020: 296). From a queer perspective, we add to this critique in our contention that with its central focus on the patrilineal cis-heterosexual family, Fishman’s RLS model excludes those practising non-normative sexual identities from language revitalisation and excludes queer people from community-based efforts to stabilise such languages.

In addition to the marginalisation of queer people within the revitalisation paradigm, both in terms of research and practice, the field of queer linguistics has largely ignored minoritised languages such as those featured in this Element and has been dominated by English or a presumption of English monolingualism, reflecting its academic origins in North America and the United Kingdom. Recent challenges to the anglophone lens include Borba’s (Reference Borba2020) analysis of queer linguistics in Brazil (although not from a revitalisation perspective) and Cashman’s (Reference Cashman2018) work on queer Spanish/English bilingualism in Arizona. Reflecting the minoritised status of Spanish in the southern United States, Cashman analyses how queer people navigate unequal power dynamics between named languages, even if one of those varieties – in this case, Spanish – is hegemonic in other contexts. Work on minoritised languages with much weaker demographic bases is less frequent still but a subfield related to sociological/anthropological and linguistic aspects of the question is emerging. This includes more socially oriented studies by authors such as Walsh on Irish (Reference Walsh2019), Hornsby on Breton (Reference Hornsby2019a), and Amarelo on Galician (Reference Amarelo2019), some of which emerged from a research network that developed within the field of critical sociolinguistics over the past decade on ‘new speakers’ (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Pujolar and Ramallo2015), people who adopt languages other than those acquired through primary socialisation. Although critical sociolinguistics has paid much attention to intersectional questions such as race (e.g. Grieser, Reference Grieser, Burkette and Warhol2021), gender (e.g. Heller, Reference Heller, Pavlenko, Blackledge, Piller and Teutsch-Dwyer2001; Pujolar, Reference Pujolar2001; Koch, Reference Koch2008), and migration (e.g. Márquez Reiter and Martín Rojo, Reference Márquez Reiter and Martín Rojo2019), there has been little attention to the social roles of queer speakers in language revitalisation or to questions of queering minoritised languages themselves in terms of gender-fair or non-binary morphology or in relation to terminology. Some recent exceptions in the case of Irish include An Foclóir Aiteach (‘the queer dictionary’; Mac Eoghain, Reference Mac Eoghain2022) and research on LGBTQ+ terminology (Murphy and Mac Murchaidh, Reference Murphy and Mac Murchaidh2023).

The lack of attention in the literature given to queer speakers of minoritised languages, both within the revitalisation and the queer linguistics paradigms, reflects and highlights the erasure of LGBTQ+ people in minority language settings. Intersectionality, while it has the potential to expand on the ‘experience of culture through identifying overlapping visible and invisible identifications with experiences of oppression and discrimination’ (Cor and Chan, Reference Cor, Chan, Ruth and Santacruz2017: 117), this has not been systematically applied to minority language communities. As a recent study on intergenerational transmission by Kircher (2019: 14) notes, ‘L1, proficiency, and attitudes on the solidarity dimension predicted a large proportion of the variance [in transmission] – but not all of it, indicating that other variables were at play’.

These ‘other variables’, including demographic variables such as sexual orientation and gender and other identity markers and life conditions such as family structure, socio-economic status and ethnic origin, are more than apparent when the transmission of minority languages is being discussed. We have already referred to the discursive exclusion of people of non-normative sexualities in Fishman’s RLS model and this possibly reflects community-driven discourses on the survival of minority languages and the assumption that a family unit of two adults of the opposite sex and 2.4 children is the optimal scenario for successful language transmission. And yet there have been major social changes over the past forty years or so, which have seen greater recognition for the rights of women, non-white people, and LGBTQ+ people (and intersections thereof), in turn leading to an increased awareness of societal diversity, inclusive of minority language communities.

As the intergenerational transmission of many minority languages continues to break down, communities are resorting to other modes of transmission, out of necessity, to complement traditional mechanisms and secure language maintenance. Romaine (Reference Romaine2006) points out that many language planners have ignored Fishman’s advice to focus on the home and community, instead investing in the relatively resource-heavy strategy of teaching minority languages through schools to each new generation. A recent volume edited by Hornsby and McLeod (2022) takes up the challenge of greater representation among minority and heritage language communities, and shows how, for example, minority language transmission is affected by modernising trends which are universal and not specific to any one type of language community. In this Element, it is shown that families from a minority background in the Breton-speaking community (like families anywhere) can experience disruption and drastic changes in circumstances when parents/caregivers decide to separate. Furthermore, language transmission is not just the responsibility of the nuclear family unit but it can (and often needs to) include grandparents, the extended family and the local community in general, to ensure the next generation of minority language speakers.

Crucially, when considering how queer people can be involved in language revitalisation, other modes of transmission need to be taken into account as well. A number of chapters in Hornsby and McLeod (Reference Hornsby and McLeod2022) look at routes of transmission for minority languages that are not necessarily intergenerationally based. For example, in the case of Upper Sorbian, transmission of the language through the agency of the schools needs to be accompanied by other factors (such as religious practice) if a new speaker of the language is to be accepted by the community (Dołowy-Rybińska, Reference Dołowy-Rybińska, Hornsby and McLeod2022). The successful maintenance of the highly endangered language of Guernésiais, it is claimed, lies in peer-to-peer transmission amongst adults, leading on to the development of proficient new speakers (Sallabank, Reference Sallabank, Hornsby and McLeod2022). However, what Hornsby and McLeod’s volume lacks – despite the best efforts of the editors – is a case study of how queer people are involved in the reception and transmission of minoritised languages. It is the experience of all the authors in this Element that LGBTQ+ people are deeply involved in minoritised language maintenance and revitalisation, and yet, as we have seen, their presence is very much missing from the academic literature on the subject.

This Element, therefore, aims to fill that research gap by providing the first anthology of papers about queer language revitalisation in Western European contexts, with a response from North America. There are two main thematic axes: (a) the sociological/anthropological, focussing on the roles of queer people in language revitalisation and their participation in policy implementation and (b) the linguistic, focussing on how minoritised languages are adapting to the demands for non-binary or gender-neutral features, as is increasingly the case in hegemonic languages across the world. The first section by Jonathan Morris and Samuel Parker analyses the intersection of linguistic and sexual identities among speakers of Welsh by examining their perceptions of representation within the language community and participation in its promotion. Using a reflexive thematic analysis, Morris and Parker identify the coexistence of Welsh-speaking and LGBTQ+ identities as the core theme and sub-themes relating to traditional values, community, and the association of English with gay culture. Despite the heteronormativity of traditional rural Welsh-speaking areas, greater visibility of LGBTQ+ people is noted across Wales and awareness of LGBTQ+ terminology is on the increase. The authors argue that the ability to express oneself has a direct bearing on language revitalisation efforts, hence the importance of consolidating queer Welsh-speaking spaces in the future.

The second section relates to another Celtic language, Irish, which despite promotional efforts by an independent state over the last century remains in a minoritised position. John Walsh analyses the work of a queer arts collective, AerachAiteachGaelach, that creates spaces for Irish speaking artists to collaborate and perform. Noting that historical discourses of Irish national identity and language policy excluded queer people, particularly in the early decades following independence in 1922, Walsh argues that the work of AerachAiteachGaelach represents a breakthrough by allowing queer Irish speakers to play an active part in the revitalisation of the language on their own terms. He analyses a theatrical production by the group in 2021, a multimedia immersive experience telling the life story of one of the group’s members, Alan Walpole, who emigrated due to homophobia but returned to Ireland and re-embraced the Irish language. Tracing Alan’s changing relationship to Ireland and the Irish language over time, Walsh’s article shows how language is interlinked with sexual identity and migration. It also underlines how the inclusive ethos of AerachAiteachGaelach allows Irish speakers of varying degrees of competence to reacquaint themselves with the language through the medium of radical artistic expression.

In the first of two sections with a more linguistic focus, Michael Hornsby examines the efforts to make a third Celtic language, Breton, more inclusive of LGBTQ+ people. With limited support from the French state and poor institutional provision in its own territory, Breton is strongly minoritised with a dramatic decline in the speaker base in recent decades. Leftist and feminist groups have nonetheless worked to make the language more gender fair, albeit along binary lines and often under the influence of approaches from French as the dominant language. Hornsby examines how more inclusive Breton terminology has been developed in the area of cultural production, for instance, in the reworking of lyrics of traditional songs. In a case study, he examines approaches to creating neologisms for a queer lexicon. While LGBTQ+-affirming language has been provided, often through voluntary effort, non-binary linguistic features are virtually non-existent. However, echoing the other sections, Hornsby points to the importance of greater inclusion of queer people as a way to enrich the base for future language revitalisation efforts.

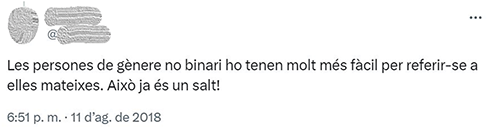

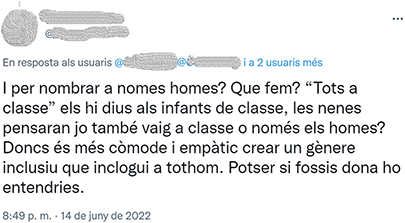

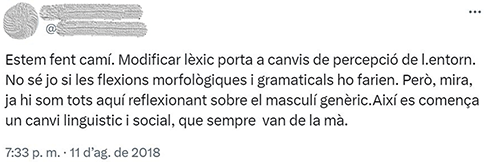

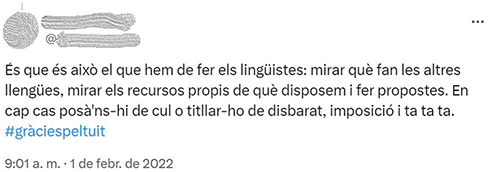

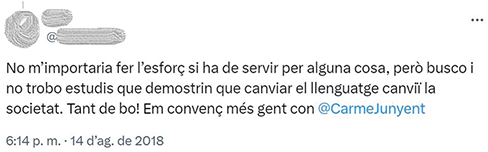

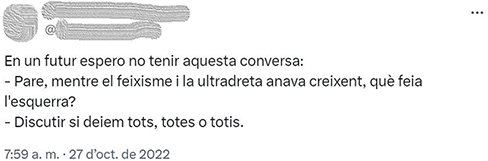

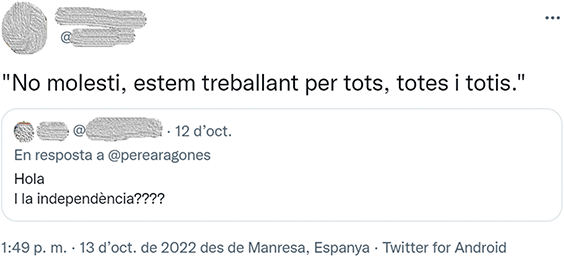

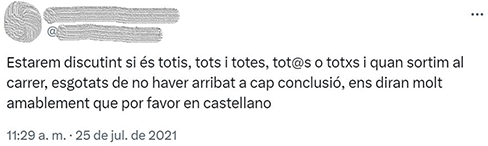

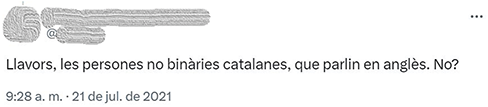

In the final section, Eva J. Daussà and Renée Pera-Ros analyse the debate about gender-neutral language in Catalan, using social media data over a seven-month period. Although Catalan is a medium-sized language by international standards and has far more speakers than the other sections featured in this Element, it remains minoritised due to hostility from the Spanish state and a continued shift to Spanish. Emphasising the need for inclusive language to accommodate the expression of performative needs of speakers, the authors analyse tweets responding to proposals for gender-neutral language in Catalan. Focussing on a thematic analysis of tweets related to neomorphemes and neopronouns, they find that attitudes are mostly negative and may intersect with transphobia and other phobias. They also highlight the use of Catalan’s perceived vulnerability as an excuse for linguistic conservatism and emphasise the potential cost to the language if the global trend of gender-neutral language is not adopted.

Long-standing and persistent attempts to minoritise speakers of Irish, Welsh, Breton, and Catalan have resulted in push-backs in the form of various revitalisation projects in each of the respective territories. Minority language speakers have been able, as a result, to find their own voice, in their own languages. Now it is the turn of queer minority language speakers to find their own voices in these sites of revitalisation and to resist the double minoritisation they have experienced over the years – minoritisation as speakers of non-majority languages, and their erasure as non-heteronormative speakers within their communities. The authors of this Element seek to open the dialogue with case studies from four particular minority language communities, in the hope that other communities will add to the dialogue in the future.

Intersecting Identities in Minority Language Contexts: LGBTQ+ Speakers of Welsh

Introduction

In critical sociolinguistics, sociology, and social psychology, thematic and discursive approaches to data analysis have contributed to our understanding of the experiences of LGBTQ+ people and how they construct their identity (e.g. Katsiveli-Siachou, Reference Katsiveli-Siachou2021; Surace et al., Reference Surace, Kang, Kahler and Operario2022; Santos, Reference Santos2023 and chapters therein). Relatively little is known, however, about the intersection between cultural/linguistic identities and other minority gender and sexual identities (Walsh, Reference Walsh2019). Specifically, the focus has been on how LGBTQ+ speakers express their identity through language rather than on the extent to which individuals combine a specific linguistic/cultural identity with their LGBTQ+ identity.

The significance of this intersection comes to the fore in the case of minority language bilingualism, where the minority language may be an important component of the speaker’s identity formation along with the idea that the speaker belongs to a wider community of minority language speakers. Furthermore, minority languages are often the subject of overt language planning measures in order to ensure their survival. In this context, the extent to which speakers who identify as LGBTQ+ (as well other minority groups) feel able to express themselves fully and be accepted within the minority language community might have direct repercussions for the vitality of that community (cf. Hornsby and Vigers, Reference Hornsby and Vigers2018).

In this section, we aim to address the gap in the previous research by investigating the experiences of LGBTQ+ speakers of the Welsh language in Wales. Specifically, we aim to ascertain how LGBTQ+ speakers of Welsh view their Welsh-speaking and their LGBTQ+ identities, and the extent to which these identities are seen to intersect. We address the following research questions:

(1) To what extent do LGBTQ+ Welsh speakers perceive there to be an intersection between their LGBTQ+ and Welsh-speaking identities?

(2) To what extent do LGBTQ+ Welsh speakers perceive barriers to representation and participation in the wider Welsh-speaking community?

Firstly, we outline the research context. We then outline the methodology and proceed to the reflexive thematic analysis of the data. Finally, we discuss the results with reference to the context of minority language revitalisation.

Research Context and Background

The current work is not situated explicitly within an intersectionality framework to the extent that we do not examine power dynamics or discrimination faced by LGBTQ+ speakers of Welsh here (see Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1989). However, we ascribe to the viewpoint that an individual’s self-ascribed identities intersect to varying degrees and that this intersection influences their lived experience (Burke and Stryker, Reference Burke, Stryker, Stets and Serpe2016: 663). Secondly, an individual’s lived experience is shaped, in part, by wider social power dynamics which are created by differences in intersectional identities (Angouri, Reference Angouri, Angouri and Baxter2021: 5). These power dynamics may lead to varying degrees of acceptance by the wider community on the one hand, or exclusion on the other hand, and have ramifications for the notions of both legitimacy and belonging. As Cashman (2020: 65) notes, ‘LGBTQ people might present themselves differently, might bring different aspects of who they are into the interaction, and might do so for different purposes’.

The study contributes to our understanding of the experiences of LGBTQ+ speakers of a minority language, and thus presents an analysis of bilingualism through a queer lens (e.g. Cashman, 2020). The decision to focus on the lived experiences of individual Welsh speakers who identify as LGBTQ+ was taken because we make no a priori assumptions about Welsh speakers representing a cohesive social group. Rather, we aim to shed new light on the extent to which LGBTQ+ speakers feel part of the wider Welsh-speaking community (see Walsh, Reference Walsh2019 for Irish). The results of the study will therefore allow us to address how greater community cohesion might be achieved in the context of Welsh language revitalisation.

The Welsh Context

Largely due to the pressure of grassroots movements and, later, the creation of the National Assembly for Wales in 1999 (now called Senedd Cymru/Welsh Parliament), the twentieth century saw an increase in language rights for Welsh speakers, the national implementation of Welsh-medium and bilingual education for children from both Welsh-speaking and non-Welsh-speaking backgrounds, and more concerted efforts to revitalise the language through governmental policy (see, for example, Carlin and Mac Giolla Chríost, Reference Carlin, Mac Giolla Chríost, Durham and Morris2016, for a more detailed overview). At present, the current Welsh Government’s aim is to increase the number of speakers to one million by 2050 and increase the percentage of speakers who use the language daily (Welsh Government, 2017).

It would be incorrect to state that civic and public discourse has ignored how more efforts might be made to increase inclusion for LGBTQ+ speakers of Welsh in Welsh-speaking public and cultural life. For example, efforts have been made to ensure that inclusive vocabulary exists in Welsh and is used in public-facing documents (Stonewall Cymru, Reference Cymru2016; Welsh Government, 2023). Within cultural events such as the National Eisteddfod of Wales (an annual Welsh language cultural festival, e.g. National Eisteddfod of Wales, 2022), LGBTQ+ spaces have been created and overtly LGBTQ+ themes have been showcased in various theatre and television productions (e.g. James, Reference James2010).

While mention of LGBTQ+ speakers of Welsh is seemingly absent from official language policy documents, the Welsh Government launched an LGBTQ+ Action Plan for Wales in February 2023 which aims to ‘make Wales the most LGBTQ+ friendly nation in Europe’ (Welsh Government, 2023). This strategy makes reference to the need for further research on the experiences of LGBTQ+ people across Wales and, particularly, those in rural communities. In addition, it outlines a commitment on the part of the Welsh Government to provide Welsh-medium support services for LGBTQ+ people as well as encouraging the visibility of LGBTQ+ people in Welsh literature and education and meeting the needs of Welsh speakers in LGBTQ+ culture more generally (Welsh Government, 2023).

There continues to be calls from the LGBTQ+ community for inclusion and LGBTQ+ initiatives which are pertinent for the current study. In recent years, for example, questions have been raised around LGBTQ+ representation on the Welsh language music scene (BBC 2022a), the wider community’s response to increased representation (BBC, 2022b) and the use of inclusive language in Welsh, particularly for non-binary people (BBC, 2023a). Furthermore, initiatives such as creating a LGBTQ+ local Eisteddfod continue to be under development (BBC, 2023b).

The study of LGBTQ+ identities in Welsh-speaking society is therefore timely and much needed. In a report commissioned by LGBTQ+ charity Stonewall Cymru and partner mental health charities, Maegusuku-Hewett et al. (Reference Maegusuku-Hewett, Raithby, Willis, Fish and Karban2015) examined policy-making, service provision and social inclusion among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults with mental health issues in Wales. They note that ‘it is not known at the present time how Welsh and LGB identities may intersect and shape each other – the ways in which LGB individuals living in Wales identify and affiliate with [the] Welsh language’ (Maegusuku-Hewett et al., Reference Maegusuku-Hewett, Raithby, Willis, Fish and Karban2015: 87).

Methods

(i) Data Collection and Participants

Full ethical approval for the study was granted by the first author’s institution and all participants gave their fully informed consent to participate in the study before a date for interview was arranged. Participants were reminded of their right to withdraw from the study at any point and to ensure anonymity were assigned pseudonyms that are used in this section.

The data for this study were collected using in-depth semi-structured interviews with eight participants who self-identified as LGBTQ+ and as a Welsh speaker. They were recruited using adverts that were placed on the social media channels of the School of Welsh at Cardiff University.

Interviews took place online in Welsh, and were recorded, using the Zoom application. Interviews lasted for between forty and eighty minutes (average of fifty-five minutes) using an interview schedule that consisted of seven main questions with additional sub-questions that were designed based on the research questions. Participants were asked to reflect on their experiences of being LGBTQ+ and Welsh speakers before talking about whether they perceive a crossover between their LGBTQ+, Welsh-speaking, and any other identities.

The sample consists of eight participants who ranged in age from twenty-one to fifty-one. Demographic information about each participant can be found in Table 1. Five participants identified as a gay man, one identified as queer, one identified as non-binary and one as a bisexual woman. Participants had all grown up in different areas of Wales, predominantly in rural areas or smaller towns, but at the time of interviews most were living in the larger towns and cities of Wales. In addition, several of the participants had spent time living in cities in England but had returned to live in Wales in recent years. Six participants had acquired Welsh via family language transmission, one participant had acquired the language through Welsh-medium education, and one participant had attended English-medium school where they had studied Welsh and gone on to complete a degree in the language. All participants were university educated.

Table 1 Participant demographic information

| Pseudonym | Age | Linguistic background | LGBTQ+ identity | Region in which the participant was raised | Current location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dylan | 23 | Family | Gay man | Southwest | Northwest |

| Mali | 38 | Family | Bisexual cisgender woman | Mid | Southeast |

| Rhian | 21 | Family | Queer | Northeast | Northeast |

| Tomos | 27 | English-medium ed. | Gay man | Southeast | Southeast |

| Ianto | 23 | Family | Gay man | Southeast | Southwest |

| Eirian | 23 | Welsh-medium ed. | Gay, he/they pronouns | Southeast | Southeast |

| Emyr | 28 | Family | Gay man | Southwest | Southeast |

| Morgan | 51 | Family | Gay man | Southwest | Southeast |

We acknowledge potential limitations in the sample and aim to address them in future research. As stated previously, all participants were university educated and were either undertaking postgraduate studies or in graduate-level employment. Furthermore, and perhaps more pertinently, no participants identified as transgender in this research, which should be considered when interpreting the results.

(ii) Data Analysis

Each interview was fully transcribed by the first author and then also translated into English. The data was analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022), an approach that identifies themes and patterns across a qualitative dataset. Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2023) refer to thematic analysis broadly as a family of methods and it should be recognised that there are a variety of approaches to thematic analysis across disciplines. They argue that distinctive features of reflexive thematic analysis are that researcher subjectivity is embraced as a resource for research and that the practice of thematic analysis is viewed as inherently subjective. Furthermore, they reject the notion that coding of the data can ever be accurate due to the inherently interpretative practice (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2023).

Another important aspect of taking a reflexive thematic analysis approach is recognising the researchers’ own positionality and relationship with the research topic (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2023). The first author is a white, cisgender, gay man who was born in Wales and has learnt Welsh as a second language both through the education system and independently. He now works at the School of Welsh, Cardiff University, where he teaches linguistics to undergraduate and postgraduate students of the Welsh language. His background allowed him to undertake the interviews in Welsh and meant that he was fully aware of cultural references made by the participants. While this was arguably beneficial for developing a relationship with participants, his own position as a white, cisgender, male academic may have placed him in a position of privilege and created an unequal power dynamic in the interview sessions.

In order to counterbalance any potential bias on his part, the data were also independently analysed by the second author. The second author is also a white, cisgender, gay male academic who was born in England, currently resides in Wales, and is a learner of Welsh.

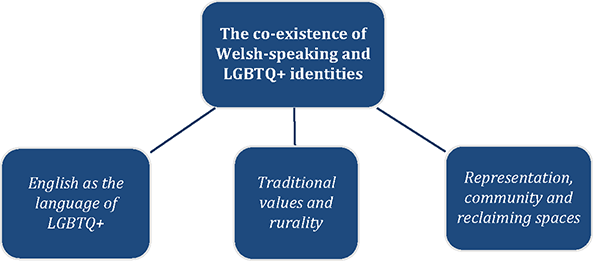

The transcripts were read by both authors and then coded separately by each author. Coding was conducted inductively, focussing on what the participant had said rather than attempting to impose pre-existing theory onto the data. Coding was reviewed and discussed by both authors and then organised into potential themes. During the discussions it became apparent that there was some overlap between themes and that several of the identified themes sat within an overarching theme of the coexistence of Welsh-speaking and LGBTQ+ identities. The three sub-themes are presented in the findings of this section with extracts from the interview data (translated into English by the authors) used to illustrate these themes.

Findings

The Coexistence of Welsh-Speaking and LGBTQ+ Identities

The thematic analysis identified that the key theme within the data was the coexistence of Welsh-speaking and LGBTQ+ identities which contained three sub-themes: traditional values and rurality; English as the language of LGBTQ+; and representation, community and reclaiming spaces. The theme structure is represented graphically in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Thematic map.

(i) ‘If I Wanted to Be Myself I Had to Be a Little Englishman’: Traditional Values and Rurality

This first sub-theme focuses on the ways in which participants discussed the perceived heteronormativity of Wales and Welsh-speaking communities that they attributed to the dominance of traditional values and rurality. This theme was apparent throughout the interviews as participants discussed the intersection between their Welsh-speaking and LGBTQ+ identities. However, it was particularly evident in parts of the interview in which participants discussed their school and family experiences at a time when they first began to develop their LGBTQ+ identities. In the following quote, Dylan talks about his experience of coming out in a rural Welsh community and his relationship with an older family member.

Ond o’n i jyst ddim yn disgwyl iddi hi fod mor cutthroat amdano fe, yrm, a bod yr agwedd yna, ti’n gwybod, y reputation a’r enw da a stwff … A fi’n credu bod hwnna’n really thing mewn cymunede fel [Enw Tref], yn enwedig cymunede Cymraeg gwledig.

But I just didn’t expect her to be so cutthroat about it, erm, and that that attitude, you know, the reputation and the good name and stuff … And I believe that is really a thing in rural communities like [Town name], especially rural Welsh-speaking communities.

Whilst later on in the interview Dylan describes having a good relationship with his relation, here he describes the challenges he faced when his sexuality was first discussed amongst his family. Dylan spoke about the importance of growing up in a close-knit rural Welsh-speaking community, and the reputation and ‘good name’ that his family had within that community. Indeed, it was him coming out as gay that he suggests not only threatened that reputation but also led to conflict with his older relation who most strongly held these traditional values.

The distinction between rural and urban areas was discussed by many participants, for example, Tomos, who talked about moving to a more rural area for university:

Dwi’n meddwl, oedd ’na bryder ynghylch hwnna achos, wrth feddwl am bobl Cymrâg yn fwy cyffredinol, dych chi’n meddwl am bobl wledig, o’r cefn gwlad a pethe. Yrm, sydd, wel mae jyst y teimlad hwnna bo’ nhw ddim mor dderbyniol â phobl yn y ddinas a pethe fel ’na. So ie, oedd ofn gen i am hwnna ond roedd fy mrhofiad i yn- oedd y rhan fwyaf o bobl yn dderbyniol iawn.

I think, there was apprehension about that because, when you think of Welsh-speaking people more generally, you think of rural people, from the countryside and things. Erm, which, well it’s just that feeling that they are not so accepting as people in the city and things like that. So yes, I was afraid of that but my experience was – most people were very accepting. (Tomos)

Tomos describes feeling ‘apprehension’ about how his LGBTQ+ identity would be accepted by ‘rural people’, suggesting that it was the rural location and community itself that was the source of this concern, rather than being related to the Welsh language specifically. Whilst he suggests that most people in rural locations were accepting of him, he uses specific contrasts with those ‘in the city’ to question whether this is always the case. Such contrasts were used commonly across the interviews, which may be reflective of the fact that the majority of participants had moved from rural to urban areas at some point. As such, many of the participants described the way in which they had only been able to fully develop their LGBTQ+ identity through moving away from traditional rural areas, particularly when they went to university.

In the following quote, Ianto describes his upbringing as being ‘heteronormative’, implying that Welsh-speaking life is equated to heterosexuality.

Dw i’n teimlo cynt pryd o’n i yn brifysgol, bod yn hoyw a bod yn Gymraeg yn eitha’ split. Ti’n gwybod, doedd dim lot o overlap rhwng nhw. Yrm, ti’n gwybod, oherwydd bod bywyd Cymraeg yn fwy, sort of, teulu heterosexual, ffrindiau heterosexual, ysgol eithaf heteronormative hefyd.

I feel that before when I was at university, being gay and being Welsh-speaking was quite split. You know, there wasn’t a lot of overlap between them. Erm, you know, because Welsh-speaking life was more sort of heterosexual family, heterosexual friends, quite a heteronormative school too.

The fact that Ianto refers directly to ‘Welsh-speaking life’ in this quote suggests that perceived heteronormativity led to a separation of his identities, leaving no space for his LGBTQ+ identity to develop at school or home. This is contrasted with his experiences at university where he suggests that his LGBTQ+ identity could take centre stage, implying that such spaces, and non-Welsh-speaking networks are less heteronormative.

When discussing the intersection of his identities, Emyr also considers heteronormativity and Welsh traditions:

I ryw raddau, ydyn, maen nhw’n plethu. Dw i’n credu. Yrm, dw i’n credu bo’ ’da fi ’falle ddealltwriaeth o, neu hen synnwyr o, yrm, yr hunaniaethe Cymrâg a Chymreig a hoyw lle dyn nhw ddim yn dod yn agos at ei gilydd o gwbl a, ti’n gwybod, does dim pobl hoyw yng Nghymru. A mae pobl sy’n siarad Cymrâg sy’n mynd i’r capel ac yn priodi ac yn cael plant a that’s it. A wedyn mae’r sort of deviants. A fi’n gwybod bod pobl dal yn meddwl fel ’na. Ond- a- mae hwnna’n effeithio arnot ti.

To some extent, yes, they intertwine. I think. Erm, I think that I perhaps have an understanding of, or an old sense of Welsh-speaking and Welsh and gay identities where they don’t get close to each other at all and, you know, there are no gay people in Wales. And there are people who speak Welsh who go to the chapel and get married and have children and that’s it. And then there are sort of deviants. And I know that there are still people who think like that. But – and – that affects you.

Here, Emyr offers a conditional acceptance of the intertwining of his LGBTQ+ and Welsh-speaking identities. He acknowledges that there is a perception of traditional values which rejects queerness and, in particular, he draws a contrast between people who ‘go to the chapel and get married and have children’ and what he refers to as ‘deviants’. As he acknowledges, the heteronormative assumptions and traditional values which he associates with some Welsh-speaking communities have made it a challenge for his identities to intersect.

Drawing on the distinction between rural and urban areas already discussed, but also the distinction between linguistic identities of being a Welsh-English bilingual, Morgan offers a similarly stark construction of the intersection of his identities when talking of the 1980s.

Doedd ’na ddim profiadau hoyw drwy gyfrwng y Gymraeg. Doeddwn i byth yn darllen, byth yn dod ar draws, hyd yn oed ddechreuadau S4C, roedd yna ychydig iawn o sôn am bobl hoyw ar S4C yn yr wythdegau. Fyddech chi byth yn clywed unrhyw beth cadarnhaol ar Radio Cymru o ran bod yn hoyw na dim byd. Rhywbeth tu hwnt i Gymru oedd e. Rhywbeth Seisnig, rhywbeth oedd e ddim yn perthyn i ddiwylliant Cymru.

There weren’t any gay experiences through the medium of Welsh. I never used to read, never came across, even at the start of S4C, there was little mention of gay people on [Welsh language television station] S4C in the eighties. You would never hear anything positive on [Welsh language radio station] Radio Cymru about being gay or anything. It was something beyond Wales. Something English, something that didn’t belong to Welsh culture.

Reflecting on growing up in a Welsh-speaking community in this extract we see the intersection between representation and culture. Morgan’s account suggests that these factors in many ways constrained his LGBTQ+ identity at that time. He emphasises this when talking about his first sexual relationship.

Oedd e’n beth rhyfedd achos, roedd yr elfen gudd ’ma ’de, mewn ffordd, yn rhywbeth Seisnig ond o’dd popeth arall amdana’ i yn rhywbeth Cymreig. Ie, oedd e’n- y ddeuloiaeth yna yn, wel, naturiol mewn ffordd […]. Os o’n i eisiau bod yn fi fy hyn, yr adeg honno, oedd angen ifi fod yn Sais bach.

It was a strange thing because, this hidden element really, in a way, was something English but everything else about me was Welsh. Yeah, it was – that dichotomy was, well, natural in a way […]. If I wanted to be myself, at that time, I had to be a little Englishman.

Overall, Morgan’s thoughts on the eighties are clear: to be gay he had to act English. In the next sub-theme, we consider further the relationship between the Welsh and English languages and how these allow or constrain particular types of LGBTQ+ identities for speakers of Welsh.

(ii) ‘Saying the Word “Hoyw” Sort of Feels Alien’: English as the Language of LGBTQ+

In the previous sub-theme, we demonstrated that there was a perceived incompatibility between aspects of Welsh-speaking and LGBTQ+ identities that was attributed to rurality and the perceived heteronormativity and traditional values in rural Welsh-speaking communities. In the final example, we saw how Morgan had seen the need be a ‘little Englishman’ in order to assert his identity as a gay man. In this sub-theme we focus on the ways in which participants in this research constructed English as being the language of LGBTQ+ people in Wales.

The first quote, from Eirian, reflects how many of the participants spoke about their use of the Welsh language generally when speaking about their LGBTQ+ identity.

Mae cwpl o ffrindiau fi sy’n siarad Cymraeg, maen nhw’n like naill yn pansexual, bisexual, neu jyst like experimenting a stwff so mae’n really neis siarad am bethau fel hwnna yn y Gymraeg. Ond, I wouldn’t say it’s like cant y cant yn Gymraeg achos bydden ni’n dechrau yn Gymraeg a newid i’r Saesneg achos mae’n fwy hawdd i drafod y pethau fel hwnna yn Saesneg achos rydyn ni wedi dysgu am y pethau ’na drwy gyfrwng y Saesneg.

There’s a couple of my friends who speak Welsh, they’re like either pansexual, bisexual or just like experimenting and stuff so it’s really nice to like speak about things like that in the Welsh language. But I wouldn’t say it was like a hundred per cent in Welsh because we would start in Welsh and change to English because it’s easier to discuss things like that in English because we’ve learned about those things through the medium of English.

Here, Eirian acknowledges that although they have Welsh-speaking LGBTQ+ friends, they might switch to English when having conversations with them about LGBTQ+ issues. Eirian appears disappointed that they are unable to have these conversations fully in the Welsh language and attributes this to LGBTQ+ issues being predominantly learnt through the medium of English. Other participants also suggested that this was due to not having LGBTQ+ specific vocabulary in Welsh, and a lack of use of particular words when they do exist, such as hoyw (gay).

O hyd, dydy pobl ddim yn dweud ‘hoyw’, maen nhw’n dal yn defnyddio ‘gay’, neu geiriau llai cadarnhaol wedwn i ond ychydig iawn iawn fydd yn defnyddio’r term ‘hoyw’. Ond maen nhw’n ymwybodol o’r gair, maen nhw’n gwybod beth yw ystyr y gair ond maen nhw dal yn peidio dewis y gair yn eu sgyrsiau bob dydd.

Still, people don’t say ‘hoyw’, they still use ‘gay’ or less positive words I would say, but very few will use the term ‘hoyw’. But they are aware of the word, they know what the word means but still don’t choose to use it in their everyday conversations.

Morgan acknowledges that whilst there is Welsh vocabulary for words associated with the LGBTQ+ community, he does not feel that they are words that are used in everyday conversations. This could suggest that there is a lack of awareness amongst the Welsh-speaking LGBTQ+ community about specific vocabulary or that the English terms come more easily to mind.

The existence of this theme in the data raises the question about the degree to which LGBTQ+ and Welsh-speaking identities can fully intersect if speakers do not identify closely with Welsh terms. Ianto similarly describes a lack of identifying with the term hoyw:

Oeddwn i ddim yn teimlo bod y gair ‘hoyw’ yn ffitio fi ac oedd e’n swnio’n od yn fy ngheg i ddiffinio fy hun fel hoyw. Ond byswn i’n gwylio stwff fel teledu, caneuon, ti’n gwybod, y cultural influences, mae’r gair gay yn- fi’n teimlo’n lot mwy socialised o fewn e […]. So mae dweud y gair ‘hoyw’ yn teimlo mor swreal ’falle, oedd e’n teimlo sort of yn alien.

I didn’t think the word ‘hoyw’ fitted me and it sounded odd in my mouth to define myself as ‘hoyw’. But I would watch stuff like television, songs, you know, the cultural influences, the word ‘gay’ is – I feel a lot more socialised within it […]. So saying the word ‘hoyw’ felt so surreal perhaps, it perhaps felt sort of alien.

The suggestion of using particular words feeling ‘alien’ again brings into question the degree to which there can be considered an intersection of these two identities. However, whilst most participants described English as the language of LGBTQ+, Dylan suggested that this was beginning to change.

Nawr mae’r termau yn cael eu defnyddio lot mwy yn Gymrâg. A, ti’n gwybod, mae’r – mae e – it’s on that shift fi’n teimlo a fi’n credu achos bod pobl yn gweld y shifft yna neu eisiau gweld shifft yn digwydd, maen nhw’n siarad amdano fe lot mwy ac mae pobl sydd eisiau dysgu hefyd eisiau dysgu a gwella eu hunan, which is great.

Now the terms are used a lot more in Welsh. And, you know, it’s the –, it’s – it’s on that shift I feel and I believe that because people see that shift or want to see a shift happen, they talk about it a lot more and people who want to learn too want to learn and improve themselves, which is great.

Dylan equates the use of LGBTQ+ terms in Welsh with a more general ‘shift’ to discussions of LGBTQ+ matters. It appears that the existence and use of Welsh terms therefore facilitates wider conversations and allows LGBTQ+ speakers of Welsh to view their identities as more intersectional, despite the fact that all Welsh speakers also speak English and that code-switching from Welsh to English is a common feature of Welsh-English bilinguals’ speech (e.g. Deuchar, Donnelly, and Piercy, Reference Deuchar, Donnelly, Piercy, Durham and Morris2016). This view was not shared by all participants, however, as exemplified by the quote from Mali’s data following:

A does gennai ddim, ti’n gwybod, tystiolaeth empirig o hyn ond dw i ddim yn teimlo’ ’mod i’n cael fy nerbyn, yrm, ie i mewn i’r gwerthoedd dinesig Cymreig yna fel person LGBTQ. Mae’n cael ei labelu fel rhywbeth really diweddar, woke, ffasiynol. Ond dyn ni wastad wedi bod yma.

And I haven’t got, you know, empirical evidence of this but I don’t feel that I’m accepted erm, yeah, into those Welsh civic values as an LGBTQ person. It’s labeled as something really recent, woke, fashionable. But we’ve always been here.

(iii) ‘Is There Space at All?’: Representation, Community, and Reclaiming Spaces

This sub-theme highlights how participants described LGBTQ+ representation in the wider Welsh-speaking community. Some participants, such as Rhian in the following quote, questioned the extent to which there was a space in Wales for Welsh-speaking LGBTQ+ communities.

Mae o’n bwysig ond dw i’n meddwl bod ’ne ddim gymaint o fel, yrm, sut dw i’n ddweud o, yrm, sdim gymaint o cyfle i fi gallu sort of mynegi fy hun yn y Gymraeg trwy’r ffaith fy mod i’n queer, so fel dw i isio ond mae ’ne ryw fath o barrier yn stopio fi. Chi’n gwybod, lle ydy cynrychioliad o pobl- neu experience fi, neu experience rhwyun arall yn y cymuned. Lle ydy o? Lle ydy o’n ffitio yn yr iaith Gymraeg? Where’s the space? Is there space at all?

It’s important but I think that there aren’t as many, erm, how do I say it, erm, there aren’t many chances for me to sort of express myself in the Welsh language through the fact that I’m queer, so I want to but there’s some sort of barrier stopping me. You know, where is the representation of people – or my experience, or the experience of someone else in the community. Where is it? Where does it fit in the Welsh language? Where’s the space? Is there space at all?

Rhian describes having a desire to be a part of a community of Welsh-speaking LGBTQ+ people but implies that these two communities exist separately and therefore the extent to which these two identities intertwine is more limited. Later in the interview, Rhian offered a more positive outlook on changes within Welsh-speaking LGBTQ+ communities:

So OK dwi’n person Cymraeg sy’n siarad Cymraeg ac mae hynny’n un rhan ohono fi a wedyn LHDT mae hwnna’n separate ond dwi’n meddwl dros amser rŵan dwi’n teimlo fel dwi’n gallu dod â’r ddau peth at ei gilydd mwy, yrm, achos y ffaith bo fi’n cyfarfod mwy mwy o pobl a’r ffaith bo fi’n gwybod bo fi ddim ddim ar fy mhen fy hun.

So OK I’m a Welsh person who speaks Welsh and that’s one part of me and then, LGBT, that’s separate but I think over time now I feel like I can bring the two things together more, erm, because of the fact that I’m meeting more people and the fact that I know I’m not alone.

Whilst previously Rhian had suggested there was little space for her Welsh-speaking and LGBTQ+ identities to intersect, here she suggests that things are starting to change and to improve so that they are ‘not alone’. Morgan also suggested that things are improving and that in part this is because Welsh-speaking LGBTQ+ people now have better representation in the media:

Mae’r rhaniad rhwng iaith a rhywioldeb yn llai nawr oherwydd y cyfryngau cymdeithasol, oherwydd dylanwad S4C mewn cymaint o wahanol ffyrdd a llai o ddylanwad y capel, eglwys ac ati […]. Ry’n ni’n llawer mwy gweladwy oherwydd S4C, a cyfryngau eraill wrth gwrs. Mae’r newidiad hynny – efallai fod cymdeithas wedi dod yn llawer mwy goddefgar ond dw i’n meddwl ein bod ni’n llawer mwy gweladwy.

The divide in terms of language and sexuality is less now because of social media, because of the influence of S4C in so many different ways and less influence of the chapel and the church and so on […]. We’re a lot more visible because of S4C, and other media of course. That change – perhaps society has become a lot more tolerant but I think that we are a lot more visible.

Some participants also suggested that traditional Welsh cultural events, such as the National Eisteddfod, were places in which they felt free to express their LGBTQ+ identities. Such accounts suggest that the intersection of participants’ LGBTQ+ and Welsh-speaking identities go beyond simply being able to speak about LGBTQ+ issues in Welsh, and that engagement in Welsh traditions also plays a key role here.

The Eisteddfod is the campest thing you can ever think of. Dyna sut dw i’n gweld e nawr, like, llefaru unigol and how it’s all expressive a dyna be’ dw i’n caru am y Steddfod mae fe – mae fe i gyd yn perfformio, mae fe i gyd i fod fel expressive a over the top and camp mewn ffordd a dyna sut dw i’n gweld e. A pob tro o’n i’n neud, like, cystadlu yn yr Eisteddfod […], o’dd ’na fechgyn yn canu, o’dd ’ na fechgyn yn perfformio, it was like, o, dyna be – I’ve been like starved of.

The Eisteddfod [cultural festival] is the campest thing you can ever think of. That’s how I see it now, like, individual recitation [competitions held at the Eisteddfod] and how it’s all expressive, and that’s what I love about the Eisteddfod it’s – it’s all performing, it’s all supposed to be like expressive and over the top and camp in a way and that’s how I see it. And every time I was, like, competing in the Eisteddfod […], boys were singing, boys were performing, it was like, oh, this is what I’ve been starved of.

The importance of both aspects of their identity was also noted specifically by Dylan:

Yrm, ie so fi ddim yn really teimlo bod ’da fi – bo fi’n fwy Cymrâg na beth i fi hoyw. A sai’n credu bo fi’n fwy, bo fi’n berson mwy hoyw na beth ydw i Cymrâg. Mae cael y dau peth yna yn intertwine – o efo’i gilydd yn really kind of diffinio fi fel person […]. Hwn ydw i, I am a Welsh homosexual.

Erm, yeah so I don’t really feel that I have – that I’m more Welsh-speaking than what I am gay. And I don’t think that I’m a gayer person than Welsh-speaking. Having those two things intertwine together really kind of defines me as a person […]. This is who I am, I am a Welsh homosexual.

Discussion and Conclusions

Minority languages are often linked to traditional values (e.g. Walsh, Reference Walsh2019 for Irish). At first glance, it could be argued that a barrier to a greater sense of cohesion between Welsh-speaking and LGBTQ+ identities is the perception that traditional Welsh-language cultural values normalise a heteronormative life experience which can often be seen as oppressive by LGBTQ+ people. The perception that minority language communities can be exclusionary has been found in other work in sociolinguistics, particularly those in the ‘new speaker’ paradigm (e.g. Hornsby & Vigers, Reference Hornsby and Vigers2018 for Welsh). We would argue, however, that in this instance the situation is more nuanced and that it is the perceived association between a Welsh-speaking heartland and rurality which merits further attention.

The deep-rooted association of tradition and rurality with heteronormativity can lead to a situation whereby Welsh-speaking communities, which are also often perceived as rural, can be seen as non-inclusive spaces. In the data, the perceived heteronormativity of Welsh-language culture and communities is often discussed with reference to rural areas. Jones (Reference Jones2019: 26) notes that ‘it is an association between a [rural heartland] region and identity that structures academic, political and popular discussions about the nature and place of “Welshness” to this day’. The perceived rurality of this region makes it difficult to disentangle perceptions of traditional values being associated with either Welsh-language culture or rural areas, the latter of which are often perceived to be more heteronormative than urban areas in work on gender and sexual identities in other contexts (even if this claim is increasingly questioned, see Driscoll-Evans, Reference Driscoll-Evans2020: 12).

The dominance of English as the language of LGBTQ+ culture was also seen as a barrier to a greater intersection between Welsh-speaking and LGBTQ+ identities. While all participants were aware of the Welsh terms for these identities, most did not use them and felt that the equivalent English terms were either quicker to come to mind or felt closer to them (see also Schmitz (Reference Schmitz2021) on lexical choice in the Deaf-queer community in Germany). On the one hand, there were clear practical reasons for this considering that Welsh terms were codified and propagated later than their English equivalents. On the other hand, this sub-theme speaks to the wider issue of the association of English (and, more specifically, American English) with LGBTQ+ culture and has been found in other language contexts (see Boellstorff & Leap, Reference Boellstorff, Leap, Leap and Boellstorff2004, and chapters therein).

Rather than represent a barrier to communication, we argue that the perceived lack in the circulation and wider use of Welsh terms for LGBTQ+ identities was symptomatic of a feeling that LGBTQ+ speakers have not been adequately represented in Welsh-speaking culture, and that it is this lack of representation which impedes increased cohesion between these aspects of identity. This was borne out more clearly in the data for the third sub-theme, where some participants questioned where the ‘space’ was for LGBTQ+ people within the Welsh-speaking community.

It would not be accurate to focus solely on barriers, however, and it was clear that experiences can change. A common thread across the three sub-themes was a perception that LGBTQ+ speakers of Welsh are more visible than in the past, and that this was a positive development which reduces feelings of being ‘alone’. The benefit of greater representation can be explained by the principle of psychological coherence (based on identity process theory), which posits that identity can be weakened when an individual cannot perceive relationships between aspects of their identity structure (Jaspal & Bayley, Reference Jaspal and Bayley2020: 208). We would therefore argue that greater psychological coherence, facilitated by representation and inclusion, fosters a greater sense of belonging for LGBTQ+ speakers of Welsh. This is a valuable aim in itself but also increases the vibrancy of Welsh-language communities and culture in the context of language revitalisation.

Queering Language Revitalisation: How a Queer Arts Collective Navigates Identity, Migration, and the Irish Language

Introduction

One aspect of discourse around many of the languages featured in this Element is that they are purportedly unsuited to the modern, urbanised world and spoken by declining conservative, rural populations. In the case of the Irish language, such a perception is amplified by historical ideologies framing native Irish as a cornerstone of national identity, linked to a powerful Catholic Church wielding significant influence over public policy. This repressive ideological framework had negative repercussions for women, LGBTQ+ people, and other minorities, many of whom emigrated in droves to escape the stultifying cultural atmosphere. Although Irish language literature contains many examples of cultural and sexual transgression, since the foundation of the state a century ago Irish speakers have been useful scapegoats for failed cultural and social policy, and the perceived link between the language and conservativism persisted until recent times. The centrality of Irish to national identity has been challenged since the 1960s and the language is increasingly seen as a minority rather than a national concern. This shift has witnessed the emergence of cultural and social groups asserting the inherent capacity of Irish to give a voice to queer people. One such group is AerachAiteachGaelach (‘gay, queer, Irish-speaking’), a queer Irish-language arts collective established in Dublin in 2020 comprising over sixty writers, musicians, dramatists, photographers, drag performers, and sound and visual artists. Many members of AerachAiteachGaelach are ‘new speakers’, people who were not raised with Irish but who have become fluent and regular speakers of it, often in parallel with their coming-out trajectories. This paper focuses on a public audio installation curated by the group, based on the story of one of its members, a gay man who emigrated to London in the 1980s but who since returned to Ireland, adapted to its changed culture, and became a new speaker of Irish.

Sociolinguistic and Policy Context

Irish is simultaneously a national, official and minoritised language spoken for the most part in Ireland but with speakers and learners in and beyond the Irish diaspora internationally. Although constitutionally the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland and a core subject in primary and secondary education, it is spoken regularly by only about four per cent of the population although a significant minority claims good to very good competence in it. In Northern Ireland, Irish was oppressed for decades under unionist government and remains minoritised, but it gained recognition as an official language under the hard-fought Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act 2022. Irish is spoken mostly among the nationalist community in Northern Ireland, but efforts continue to spread awareness and knowledge of it among unionists.Footnote 1

The 2022 census returns for the Republic of Ireland record 1,873,997 people or 40.4 per cent of the population as being capable of speaking Irish, a 6 per cent increase on 2016. The counties with the highest percentages of speakers are Galway (50%) and Clare (47%). A new question about self-reported ability in Irish revealed that 195,029 or 10 per cent of the total number of speakers reported speaking Irish very well and 593,898 or 32 per cent reported speaking Irish well. In terms of frequency of use, 115,065 or 2.3 per cent said that they spoke Irish weekly outside the education system, an increase of 3.2 per cent and 71,968 or 1.4 per cent reported speaking it every day both within and outside the education system, a drop of 2.5 per cent. In the historically Irish-speaking Gaeltacht areas, 65,156 people or 66.3 per cent indicated that they could speak Irish, an increase of 2.3 per cent from 2016. However, only 20,261 people or 19.7 per cent of the population reported speaking Irish every day, a drop of 1.6% on the previous census. However, this figure masks considerable differences between different areas where Irish may be weak or strong as a community language (Central Statistics Office, 2017 & 2022).Footnote 2

In Northern Ireland, 228,600 people or 12.4 per cent of the population aged three and over reported some ability in the Irish language in the 2021 census, an increase from 2011. Within the population, 126,700 or 6.9 per cent said that they could speak Irish with 43,500 or 2.4 per cent doing so every day. Asked to record their ‘main language’, Irish was the third largest option after English, with 0.3 per cent of respondents (6,000 people) choosing that option (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2022a & 2022b). Although all six counties of Northern Ireland contained the vestiges of Gaeltacht areas when it was established in 1921, no such community survived the twentieth century. Irish language networks in Co Derry and in west Belfast have been recognised by Foras na Gaeilge, the cross-border agency for the Irish language set up under the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 (Walsh, Reference Walsh2022: 29–34).

Background

When the Irish state was established in 1922, a key policy plank was the revival of the Irish language throughout the country and the maintenance of Irish as the primary language of the Gaeltacht, the scattered, mostly coastal, districts in the west that were historically Irish-speaking. Irish society and political culture were deeply conservative for most of the twentieth century and language policy was implemented in parallel with a raft of social policies that were strongly influenced by the Catholic Church (Walsh, Reference Walsh2022). This led to associations between the Irish language and conservative ideology, as outlined by one of the founders of AerachAiteachGaelachFootnote 3, who described the rationale for founding the group and staging the play Idir Mise agus Craiceann do ChluaiseFootnote 4 in 2021:

Tá sé an-tábhachtach dúinne cur i gcoinne an smaoinimh nach féidir dlúthbhaint a bheith idir Éireannachas/Gaelachas agus aiteacht. Sin rud ba mhaith linn a dhéanamh leis an ngrúpa seo agus le léiriú an dráma seo – is cuid den scéal náisiúnta é an scéal seo faoi dhaoine aiteacha.

It is very important for us to oppose the idea that there cannot be a close connection between Irishness/Irish speaking identity and queerness. That’s what we want to do with this group and with the production of this play – this story about queer people is part of the national story.

This statement echoed research that I have been doing for some years about queer Irish speakers and it reminded me of the tension that some participants felt between identity related to the Irish language and identity related to their sexuality. On the one hand, the historical burden of conservatism was associated with the Irish language after the establishment of the state and it was believed that a trace of that ideology persisted. Various minorities who did not fit the hegemonic version of identity, including LGBTQ+ people, had been marginalised over the decades. On the other hand, English was strongly linked with global queer culture (Motschenbacher, Reference Motschenbacher2011: 163) and there were concerns about the expression of sexuality in other languages, especially minority languages such as Irish. Some of the interviewees felt trapped between the global culture of the English language, on the one hand, and the historical conservative Irish culture, on the other hand (Walsh, Reference Walsh2019). It could be argued that there is a great diversity of opinion in the Irish community, that it has always contained a progressive strand, and that the people who spoke to me were not representative of the majority’s experience. However, that was not the purpose of the research: what I set out to do was to conduct an initial investigation of opinions about such issues among a sample of people who felt some kind of belonging to the ‘Irish language community’, however vague and uncertain that concept is. It was high time, in my opinion, to carry out social research on the identities of Irish-speaking queer people and my experience as a gay man whose coming-out story was linked to becoming a speaker of Irish was a strong personal motivation.

A leading historian of modern Irish history referred to a similar dynamic to that identified when he argued that many public intellectuals in the last century associated Irish language policy with a censorious and anti-intellectual official culture that was firmly rooted in the Catholic Church. Although some criticism of the Irish-speaking community was excessive and unfair, according to Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh (Reference Ó Tuathaigh and Mac Cormaic2011: 83) it was ‘unfortunate’ for the language that it was linked to conservatism and narrowness in the minds of progressive people in the past. There are many examples of that hostility in the public and intellectual discourse during the twentieth century and although Irish speakers were often unfairly and inaccurately stereotyped, such views gained a foothold in the public imagination and were a significant obstacle to the promotion of Irish over the years.

In the 2021 interview, Eoin McEvoy and his co-founder Ciara Ní É said that AerachAiteachGaelach aimed to challenge such understandings and provide a space where artists of all kinds could come together through the Irish language (Ní É, & McEvoy, Reference Ní É, McEvoy, Ní Mhuircheartaigh, Ní Ghairbhí and Liatháin2021: 263). In that way, it would be possible to tackle the void felt by those who wish to practise both Irish language and queer identities. In an interview with me in 2022, both drew strongly on a language revitalisation discourse and said that it was important that AerachAiteachGaelach attracted artists to continue working in Irish rather than returning to English. They also used the label ‘new speaker’ to describe themselves and McEvoy emphasised the similarities between ‘coming out’ as a queer person and the conscious effort people make to become new speakers (McEvoy & Ní É, Reference McEvoy and Ní É2022). The ‘new speaker’ concept has been proposed as a lens through which to understand people who speak languages with which they do not have historical associations or experiences of early socialisation, for instance, in their families or communities. It attempts to move beyond rigid categories of ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ speakers and proposes a framework of analysis that transcends categories of deficit that are long-established in linguistics and related academic strands. Work drawing on the new speaker framework over the past decade has analysed the practices, ideologies and trajectories of people adopting languages other than their initial language of socialisation or community (for an overview of the new speaker concept, see O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Pujolar and Ramallo2015; for an analysis of new speakers of Irish, including people who identity as gay or queer, see O’Rourke & Walsh, Reference O’Rourke and Walsh2020).

The remainder of this article consists of an analysis of the play referred to earlier in this section, Idir Mise agus Craiceann do Chluaise, which was staged in 2021 as part of the Dublin Fringe Theatre Festival. The discussion begins with an analysis of interviews with the writers and the protagonist and is followed by a textual analysis of extracts from the script that highlighted salient themes related to the link between language and sexuality. I will argue that the play brought together different strands of the complex relationship between national identity, the Irish language, and queerness and that the theme of migration was effectively used as an integral part of the Irish experience, especially at the end of the twentieth century. The play was based on the story of Alan Walpole, a musician and barber who emigrated as a youth in the 1980s to escape the homophobic atmosphere in Dublin. After emigrating to England, Alan decided to reconnect with the Irish language and took up language classes. When he returned permanently to Ireland in 2018, he registered with AerachAiteachGaelach where, he said, he could express both aspects of his identity. The founders of AerachAiteachGaelach decided that they would write the story of his life but as shown in the play, it was challenging for Alan to settle in Ireland again and the process involved both relief and heartache. Eoin McEvoy explained that the group wanted to show that the stories of queer people, many of whom had to leave Ireland, are an integral part of Irish history (Ní É & McEvoy, Reference Ní É, McEvoy, Ní Mhuircheartaigh, Ní Ghairbhí and Liatháin2021: 267). He gave more information in an interview with me:

Is cuimhin linn fós b’fhéidir ruball na tréimhse sin. Ní raibh sé éasca orainne ach ní raibh sé pioc cosúil leis an rud a raibh seisean [Alan] i ngleic leis ach ní raibh sé éasca ach an oiread dúinne agus mar sin d’aithin muid an-chuid de na rudaí a raibh sé ag caint mar gheall orthu. Ach theastaigh uainn go dtuigfeadh daoine atá níos óige arís ná muid gur rud an-nua é go bhfuil na saoirsí seo againn agus go bhfuil an saol níos fearr.

We still remember perhaps the tail of that period. It wasn’t easy for us but it wasn’t one bit like what he [Alan] was dealing with but it wasn’t easy for us either so we recognised a lot of what he was talking about. But we wanted people who are younger than us to understand that it is a very new thing to have these freedoms and that life is better now.

Regarding Alan Walpole’s linguistic background, his family in Dublin did not speak Irish but according to his own account, he acquired a reasonable ability from schooling and additional summer periods in the Irish-speaking Gaeltacht areas, where many children attend immersion courses during school holidays. While in England, he started learning Irish again and took the European Certificate in Irish (Teastas Eorpach na Gaeilge) exams at B2 (upper intermediate) level. After joining AerachAiteachGaelach back in Ireland, he was interviewed bilingually by the founders about his life and an immersive audio installation was created in seven different spaces representing various periods of his life. Among them were Alan’s family home, a barber’s shop in Dublin, a gay nightclub and bedroom in London, his family kitchen, the Dublin gay bar The George during the marriage referendum in 2015, and his mother’s home in recent years. All spaces were created in the social club of Conradh na Gaeilge, a centre used by the Irish-speaking community in Dublin. Idir Mise agus Craiceann do Chluaise was not a conventional piece of art in the sense that one would imagine a stage play: due to the restrictions of Covid-19, the audience had to walk through the spaces one person at a time and listen to a soundtrack that was a combination of Alan Walpole’s voice as a narrator and specially composed music. The installation was in Irish but an English translation of the script was available in the venue for those with limited Irish or no ability in it.

When interviewed by me, Alan Walpole explained the tension he had historically felt between his national and Irish language identity and his identity as a gay man and described how he came across AerachAiteachGaelach after returning to Dublin:

Chonaic mé fógra greamaithe ar an doras agus ar an bhfógra sin bhí ‘Queercal Comhrá’, grúpa daoine aeracha a bhí ann agus bhí Gaeilge acu ach dúirt mé liom féin ‘Jesus nach bhfuil sé sin iontach?’ Tharla sé sin beagnach ceithre bliana ó shin, an chéad uair i mo shaol go raibh mé chomh háthasach an saghas fógra sin a léamh ach thug sé sin dóchas dom go mbeadh mé in ann bualadh suas le daoine cosúil liomsa agus go mbeimis in ann comhrá a dhéanamh i nGaeilge … Chuir sé sin gliondar ar mo chroí ach fuair mé amach ar an bpointe boise nach raibh mórán Gaeilge agam [gáire].

I saw a notice stuck on the door and on that notice was ‘Queercal Comhrá’,Footnote 5 it was a group of gay people and they spoke Irish but I said to myself ‘Jesus isn’t that great?’ That happened almost four years ago, the first time in my life that I was so happy to read that kind of announcement but that gave me hope that I would be able to meet people like me and that we would be able to chat in Irish … That made me really happy but I found out right away that I didn’t know much Irish [laughter].

Analysis of Idir Mise agus Craiceann do Chluaise

Three extracts from the play have been chosen for analysis in this section. The first captures the homophobia of Alan’s youth before he emigrated, the second represents his elation during a visit home for the 2015 marriage equality referendum, and the third reflects his ambiguous feelings having returned home permanently in 2018. The play begins in his sitting room in 1980s Dublin where his parents condemn gay people while watching a television report on the AIDS crisis. Alan is outed when his mother reads his diary, describes him as ‘very sick’, and threatens to bring him to a psychiatrist. In the first extract, Alan tells us how this experience prompted him to decide to emigrate:

Níl uaim fágáil ach cén rogha atá agam? Tá grá agam d’Éirinn ach níl grá aici dom. Nílim san áit cheart in Éirinn.

[Guth na máthar:] You are not, you are not, you are not.

Thaispeáin leaid éigin cóip de The Gay Times dom is mé amuigh ag damhsa in Flikkers. Agus mé ag féachaint tríd ar na fir dhathúla ag damhsa, iad saor, sásta, gan léinte orthu thall i Londain, arsa mise liom féin: ‘Céard sa tsioc atá á dhéanamh anseo agam?’

Deir Mam go bhfuil sí ag guí nach n-imeoidh mé. Tá sí buartha fúm – áit éigin in íochtar a croí. Ach caithfidh mé imeacht. Le mé féin a tharrtháil.

Fág an tír sin nár ghlac ariamh leat. Téigh suas an pasáiste i dtreo do thodhchaí. Éalaigh liom is imigh liom ón oileán sin a mhúch tú. Siúil, siúil. Lean an ceol, lean do chosa, trasna na farraige. Teith liom. Go Sasana.

[*Ceol: ‘Upbeat X Fill a Rún’, meascán idir port le hAries Beats agus amhrán Aoife Ní Mhórdha a rinneadh go speisialta don dráma*].

I don’t want to leave but what choice do I have? I love Ireland but it doesn’t love me. I’m not in the right place in Ireland.

[Mother’s voice in English:] You are not, you are not, you are not.

A lad showed me a copy of The Gay Times while I was out dancing in Flikkers. As I looked through it at the handsome men dancing, free, happy, shirtless over in London, I said to myself: ‘What the hell am I doing here?’

Mam says she’s praying that I won’t go. She’s worried about me – somewhere deep in her heart. But I have to go. To save myself.

Leave that country that never accepted you. Walk up the aisle towards your future. Escape with me and depart with me from that island that suffocated you. Walk, walk. Follow the music, follow your feet, across the sea. Run away with me to England.

[*Music: ‘Upbeat X Fill a Rún’, a mix of a tune by Aries Beats and a song by Aoife Ní Mhórdha composed especially for the play*].

We see some of the tension between identities here: although Alan Walpole ‘loves’ Ireland, he feels completely out of place in it. Ireland is a suffocating country for him and he must flee to save himself. His mother adds to that alienation and the decision to recite her words in English creates a gap in the audience’s mind between Alan and her. Flikkers was Dublin’s gay club, based in the Hirschfeld Centre in Temple Bar until it burned to the ground in 1988. The use of music is very effective: the song ‘Upbeat X Fill a Rún’, a track specially composed for the play, is a mix of the traditional sean-nós style of unaccompanied Irish singing and synth-pop or new wave music of the 1980s.

The play then moves to London and the audience enters a gay nightclub and goes into Alan’s bedroom. In a space containing the family kitchen table, the listener is told about a painful visit home by Alan with his new lover, Tony, in the 1990s. His parents denied them recognition as a couple by prohibiting any displays of affection and putting them in separate bedrooms. Later in the play, Alan describes a happier trip that he made to Ireland in 2015 for the marriage referendum:

Téimis go hÉirinn le chéile. Lean an téip, siúil tríd an doras.

[*Láithreán: Cóisir mhór ag Pantibar, dathanna, bratacha i ngach áit.*]

An bhfeiceann tú na dathanna?

[*Ceol: Retro Electro EDM le hAries Beats*]

Cas timpeall, cas arís, cas is cas, luasc timpeall is timpeall, lig dóibh meascadh romhat: dearg, oráiste, buí, glas, gorm, corcra, bándearg, bánghorm, donn, dubh. Cá bhfuil tú? Tá tú in Éirinn. Sa bhaile! Fillte. Suigh in airde ar an stól. An difríocht atá ann! An meon. Athraithe go huile is go hiomlán. Ní chreidim gurb é an saol céanna é, gurb é an domhan céanna é. Éire athraithe. Tír a vótáil ‘tá for grá’.

GLÓR OIFIGIÚIL: Líon na vótaí i bhfabhar an togra: milliún, dhá chéad is a haon míle, sé chéad agus a seacht.

[*Fuaim: Slua ag ceiliúradh go glórach. Tagann deireadh leis an gceol.*].

Let’s go to Ireland together. Follow the tape, walk through the door.

[*Site: Big party at Pantibar,Footnote 6 colours, flags everywhere.*]

Do you see the colours?

[*Music: Retro Electro EDM by Aries Beats*]

Turn around, turn again, turn and turn, swing around and around, let them mix before you: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple, pink, white, brown, black. Where are you? You are in Ireland. At home! Returned. Sit up on the stool. What a difference! The mood. Completely changed. I don’t believe it’s the same world, it’s the same world. A changed Ireland. A country that voted ‘tá for grá’.Footnote 7

OFFICIAL VOICE: Number of votes in favour of the proposal: one million, two hundred and one thousand, six hundred and seven.

[*Sound: Crowd celebrating loudly. Music ends*]

In this extract, Alan shows his amazement at the result of the referendum, a public response that echoed the huge social change that took place in Ireland since he left years before. That transformation was incredible for him in light of what he suffered in his youth. Clever use is made of the country’s official bilingualism by including the Irish part of the declaration of the referendum result on the soundtrack. The Irish language is rarely mentioned explicitly in Idir Mise but because Alan made a conscious decision to tell the story of his life in that language, the chosen medium has profound symbolic importance. One reference to his learning journey is made in the play when Alan mentions a time when he was waiting for friends from the Queercal Comhrá in Pantibar. He called them ‘my tribe’ (mo threibh), an expression of the solidarity and belonging he felt with them.

The final passage to be discussed relates to the end of the play, where the story is told from 2018 onwards when Alan decided to return to Ireland on a long-term basis. At home again in the house where he was raised, he has mixed feelings because his mother still refuses to accept him as a gay man, but there is a glimmer of hope nonetheless:

Mar gach ábhar díomá i mo shaol, d’eascair sé as an rud seo: gur fear aerach Éireannach mé. Ach gach cúis áthais freisin, tá a fhréamh sa rud céanna, gur fear aerach Éireannach mé, ar ais in Éirinn nua.

Cá mbeidh mo thriall nuair a chaillfear Mam? Níl a fhios agam. Ach táim beo.

[*Ceol: ‘Upbeat X Fill a Rún’ arís.*]

Agus tá an t-ádh liom bheith beo. Tuigim sin. Táim fós chomh folláin leis an mbradán seang. Tá mo chroí fós lán de ghrá, de ghnéas, de mhianta. Ach ní raibh mé riamh in ann mé féin a chur in iúl mar is ceart. Go dtí anois.

Tá cogadh mór fada buaite agam inniu. Má fhanaim, nó má fhillim thar farraige, táim ábalta labhairt faoi na rudaí seo ar deireadh. Leatsa.

Like all disappointments in my life, it stemmed from this: that I was a gay Irish man. But every reason for joy is also rooted in the same thing, that I am an gay Irish man, back in the new Ireland.

Where will I go when Mam dies? I don’t know. But I’m alive.

[*Music: ‘Upbeat X Fill a Rún’ again.*]

And I’m lucky to be alive. I understand that. I’m still as fit as a fiddle. My heart is still full of love, sex, desires. But I was never able to express myself properly. Until now.

I have won a great long war today. If I stay, or go abroad again, I’m able to talk about these things at last. With you.