Introduction

Climate change and biodiversity loss are examples of socio-ecological challenges caused by anthropic pressures at a global scale (Lam, Reference Lam2006; Roggero et al., Reference Roggero, Bisaro and Villamayor-Tomas2018; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Carpenter, Rockstrom, Crépin and Peterson2012). These challenges result in complex and intractable social dilemmas, related, for example, to the governance of common-pool resources in large socio-ecological systems (SESs) (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2012a). These dilemmas inform a long-standing debate in institutional and organizational economics concerning the relation between collective actions and polycentric governance (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Arnold and Villamayor-Tomas2010; Roggero et al., Reference Roggero, Bisaro and Villamayor-Tomas2018), and how complex SESs work, both theoretically and empirically (Jenssen, Reference Janssen2006; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2012a; Roggero et al., Reference Roggero, Bisaro and Villamayor-Tomas2018; Young et al., Reference Young, Berkhout, Gallopin, Janssen, Ostrom and van der Leeuw2006). This debate largely builds on research investigating institutional dynamics introduced by North (Reference North2005), Williamson (Reference Williamson2000), and Ostrom’s pioneering work on institutional analysis and development (IAD) (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2013; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2011), and the social-ecological systems framework (SESF) (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2009a, Reference Ostrom2010b). On one hand, this debate has focused on how norms and rules are defined to manage resources in complex SESs, including polycentric governance (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2009b ), and collective actions (Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Burger, Field, Norgaard and Policansky1999; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a). In this framework, norms and rules assume the functions of framing agents’ behaviour, either by defining and prescribing a social order (e.g. when regulations and laws limit or allow specific activities in society), and/or by supporting agents in making decisions and allocating resources in environments that require adaptation and resilience, and a trial and error approach (Kunneke et al., Reference Kunneke, Ménard and Groenewegen2021; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a). Rules are understood as ‘institutional artefacts that delineate the domain within which actions are required, prohibited, or permitted’ (Kunneke et al., Reference Kunneke, Ménard and Groenewegen2021: 52). On the other hand, this debate has started to investigate the governance of complex systems, such as network infrastructures, looking at institutional embeddedness, as well as coordination and alignment between agents operating at different institutional layers (Kunneke et al., Reference Kunneke, Ménard and Groenewegen2021; Menard, Reference Ménard2017). This approach understands the governance of complex systems as subject to biophysical laws, technological conditions, and socio-cultural norms (particularly in terms of reciprocity and trust) (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2014), and how human-made rules and rights are framed and defined (Kunneke et al., Reference Kunneke, Ménard and Groenewegen2021).

This debate has so far contributed to theorize how institutional dynamics define multi-layered and nested arrangements through which socio-ecological challenges and dilemmas can be tackled effectively (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a; Roggero et al., Reference Roggero, Bisaro and Villamayor-Tomas2018). However, what scholars are still exploring is a more fine-grained understanding of how individuals, organizations, and communities establish, develop, and/or discontinue processes of governance between different institutional layers in a context of uncertain and rapidly changing socio-ecological conditions. These conditions, particularly, question the principles of how to design effective collective governance and mechanisms of appropriate coordination among relevant groups operating in such complex and uncertain conditions (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Ostrom and Cox2013). Often appropriate coordination can be achieved by mechanisms of subsidiarity, which ‘assigns governance tasks by default to the lowest jurisdiction, unless this is explicitly determined to be ineffective’ (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Ostrom and Cox2013: 22). However, agents tackling global socio-ecological challenges deal with a rather fragmented and scattered legal and regulatory landscape, and a weak or emergent institutional environment, lacking operational and enforceable rules and norms. Some of the phenomena are newly and rapidly emerging, in fact, leaving out the possibility of relying on informal and historically constructed rules and norms. Climate change and biodiversity loss, two of the most debated and investigated global challenges, provide a striking example in this sense (Roggero et al., Reference Roggero, Bisaro and Villamayor-Tomas2018; Whiteman et al., Reference Whiteman, Walker and Perego2013). In this context, rules and norms have mostly been confined to the national governmental level while inter-governmental actions have struggled to emerge, even after decades of fierce political discussion, and remain confined to international treaties and legal frameworks, like the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UN Global Compact, or the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (Heinen et al., Reference Heinen, Arlati and Knieling2022). In our view, the absence or fragmentation of more general rules and the lack of macro-institutions to tackle global socio-ecological challenges pose relevant questions on how subsidiary mechanisms of coordination can be adopted and enhanced in a polycentric governance approach. This unsolved puzzle informs our research questions, and namely, an investigation of (i) how agents define subsidiary mechanisms of coordination related to polycentric governance when dealing with absent or weak institutional environments and subsequently, (ii) how subsidiary mechanisms of coordination are relevant to the definition of macro-institutions and constitutional or collective rules. We tackle these questions through a process of institutional analysis of social-ecological systems (Janssen, Reference Janssen2006) and theory-building from cases (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt2019) to investigate how subsidiarity in large SESs unfolds through nested and interrelated institutional processes to manage global challenges. Building on the current debate on meso-institutional processes (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022) and Ostrom’s polycentric governance (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2014; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010b) and design principles (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Ostrom and Cox2013), we investigate meso-institutional processes emerging in so-called cross-sectoral and multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs), where businesses, governments, and civil society organizations try to address global grand challenges (Dentoni et al., Reference Dentoni, Pinkse and Lubberink2021). During the last two decades, MSPs have been set up around different global socio-ecological problems, for example, involving agriculture and food provisioning (Dentoni et al., Reference Dentoni, Bitzer and Pascucci2016), fishery, forestry, water, energy, public health, sanitation, and urban planning (Dentoni et al., Reference Dentoni, Pinkse and Lubberink2021). The recognition of these institutional processes in the context of the establishment and formation of MSPs allows us to further explore and theorize the polycentric governance of global socio-ecological challenges in large social systems, looking at nested, interrelated, and multi-layered relations between multiple agents, organizations, and communities.

The paper is organized as follows: in the next section, we present the theoretical background, with a specific focus on the SESF (section Global socio-ecological challenges and design principles for collective governance) and the meso-institutional framework (MIF) (section Combining the SESF with a meso-institutional approach). In the section, Research and methodological strategy, we present our research strategy and methodological approach. Section Findings presents our main findings, while in section Towards a meso-institutional theory of polycentric governance of global challenges, we discuss our contribution to theorize the polycentric governance of socio-ecological challenges through a meso-institutional perspective. Section Conclusions presents concluding remarks, main limitations, and future research agendas.

Theory background

Global socio-ecological challenges and design principles for collective governance

The SESF has been used in interdisciplinary research for co-constructing and testing alternative theories and models relevant for the ‘micro-analyses of social dilemmas’ (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2014; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2011). The SESF has been able to provide a context for investigating ‘complexity’ inherently connected with issues of governance of socio-ecological challenges (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2013; Janssen, Reference Janssen2006; Lam, Reference Lam2006), stimulating work on ‘governance of complex and adaptive systems’ (Nagel and Partelow, Reference Nagel and Partelow2022), for example, related to climate change (Roggero et al., Reference Roggero, Bisaro and Villamayor-Tomas2018), global pandemics (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2012a; Paniagua and Rayamajhee, Reference Paniagua and Rayamajhee2022), urban governance (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom and McGinnis1999; Ostrom Reference Ostrom2012b), groundwater and irrigation systems (Janssen and Anderies, Reference Janssen and Anderies2013; Lam, Reference Lam2006), forestry and fishery resources (Collen et al., Reference Collen, Krause, Mundaca and Nicholas2016; Nagendra and Ostrom, Reference Nagendra and Ostrom2012; Paniagua and Rayamajhee, Reference Paniagua and Rayamajhee2024), and development policy (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2014), amongst others. Ostrom has extensively discussed the importance of identifying challenges, dilemmas, decisions, and related outcomes in relation to the institutional level at which they take place (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2012a).

When challenges or dilemmas affect agents and outcomes at different levels, it is expected that polycentric governance will (or should) emerge as an effective institutional process (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a). This is a crucial point since it implies that global socio-ecological challenges do not need to be resolved only at a global scale (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2012a). In fact, a polycentric approach to tackle these challenges should be built upon the principle of subsidiarity, which indicates that actions and interventions should be placed as close as possible (in terms of level of governance and/or geographical/ecological scale) to where they are meant to influence actors concerned with the problem, but always embedded in a larger system that supports the autonomy of lower level governance and provides the essential support, including conflict resolution (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Ostrom and Cox2013). At the core of this approach sits the idea of nested and interrelated centres (nodes) of decision-making, forming a polycentric system of governance as ‘one where many elements are capable of making mutual adjustments for ordering their relationships with one another within a general system of rules where each element acts with independence of other elements’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom and McGinnis1999: 57). As such, in a polycentric system, multiple (public and private) organizations and communities operate at different institutional levels and socio-ecological scales, simultaneously affecting and being affected by collective benefits and costs (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010b). This approach distinguishes between three institutional levels (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2014): an operational level, where actors (either as individuals or representatives of collective entities) make practical choices (e.g. develop and enact practices) among their available options as determined by collective norms and rules. Similarly, constitutional-level choices relate to and create constraints for actors participating in the making of collective and operational-level choices and decisions. At the same time, and following the principle of subsidiarity, in designing or supporting collective governance to tackle socio-ecological challenges, decision-makers should primarily enable solutions and interventions at the operational level, and if ineffective, allow mechanisms of support from the collective or constitutional level. Put differently, the SESF considers a hierarchical and multilevel approach to rule-making that defines and constrains operational activities (practices) of agents immersed in an action situation representing a socio-ecological challenge (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2011). Operational activities are enabled and constrained by socio-ecological conditions, collective and constitutional norms, as established by previous or concurrent collective and constitutional processes. In this way, socio-ecological challenges can be treated and investigated at different levels, and most importantly, the outcomes of interactions in different levels of analysis are explicitly connected to each other (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2014). This approach to polycentric governance also emphasizes the fundamental links between institutional levels and the identification of ways to address challenges through collective actions (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2013). It questions, particularly through the principle of subsidiarity, the assumption that only high-level institutional processes, for example through the state and public authorities’ interventions, are relevant for the provision and production of (global) public or common-pool goods, and that only a global scale is relevant for the governance of global challenges, such as climate change (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2012a). Instead, extensive empirical research has demonstrated that while high-level institutional processes are an essential part of an effective collective governance of large-scale challenges, small and medium-level processes are also necessary components (Nagel and Partelow, Reference Nagel and Partelow2022). For example, Heikkila and colleagues (Reference Heikkila, Villamayor-Tomas and Garrick2018) present a vast set of empirical and theoretical contributions related to polycentric systems and environmental governance. They describe polycentric systems as having multiple independent centres of authority that overlap and coordinate through forms of cooperation, competition, conflict, and their resolution. In their view, polycentric systems depend on some level of ‘constitutional authority’ afforded to a diversity of decision units, which is common in federalist and decentralized governance levels. While this is founded on the principle of subsidiarity, it is the coordination or degree of interaction across these levels that differentiates polycentric systems from fragmented systems, meaning that not all decentralized systems are necessarily polycentric. Dressel and colleagues (Reference Dressel, Ericsson and Sandström2018) have investigated polycentric governance to tackle the challenges of wildlife management at the regional level and informed an adaptive policy approach accordingly. While biodiversity loss remains one of the most complex global challenges, actions to mitigate, reduce, and potentially revert losses require governance approaches implementable at the local level, while rules and incentives are defined by national policy frameworks. Albareda and Branzei (Reference Albareda and Branzei2024) have recently investigated subsidiary governance processes by which local actors attempt to regenerate over-exploited and polluted inland lakes in Finland. An important implication of this strand of empirical research is the increased understanding of the relevance of subsidiary mechanisms between different institutional levels, based on nested and interrelated relations affecting nodes of decision-making able to tackle, and perhaps solve, global socio-ecological problems. However, what seems to be still overlooked in this scholarship is a clearer understanding of subsidiary mechanisms of coordination taking place when constitutional rules are absent or fragmented, and in the context of weak macro-institutions.

Combining the SESF with a meso-institutional approach

To tackle this gap, we explore a more recent theoretical approach looking at the governance of complex systems, like network infrastructures, through a multi-layered perspective of institutional embeddedness and change (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). In this approach, the governance of complex systems is understood as subject to both physical laws, through their technological dimension, and how human-made rules are framed and defined (Kunneke et al., Reference Kunneke, Ménard and Groenewegen2021). Moreover, this framework more explicitly investigates the governance of complex systems through the lenses of institutional embeddedness, connecting rules, norms, and agents situated at different institutional layers (Kunneke et al., Reference Kunneke, Ménard and Groenewegen2021; Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). This framework interestingly connects Ostrom’s notion of operational, collective, and constitutional norms and rules with North’s (Reference North2005) and Williamson’s (Reference Williamson2000) theorizing of institutional change, and how norms and rules emerge, develop, and eventually disappear. This scholarship suggests distinguishing what is defined as an ‘institutional environment’ from a context of ‘institutional arrangements’ (Davis and North, Reference Davis and North1970). The former indicates an institutional layer where general rules, both formal and informal, are established, for example, laws, regulations, norms, and customs defining and allocating rights to use resources, while the latter indicates an institutional layer where actors, such as firms, associations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), play their ‘economic game’ given the rules set at the level of the institutional environment (Davis and North, Reference Davis and North1970; Williamson, Reference Williamson2000). The rules at this level tend to be ‘general’, set at the societal level, and affect several actors, often operating in different markets, industries, or jurisdictions (Williamson, Reference Williamson2000). These rules are often formal and regulatory in nature, but they are not necessarily set in regulations and laws. For example, they can be rooted in customs or cultural norms (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Jimenez and Tropp2018). Moreover, general rules can be defined and applied to different territorial scales, from regional to international, according to where and how they are set. In this sense, we can define the institutional environment as a ‘macro-institutional layer’ (Kruglova, Reference Kruglova2018; Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). Actors operating at the layer of institutional arrangements are expected to take these general rules to form the institutional framework in which they can operate, but they also engage in ‘rule making’, in the sense of set ‘idiosyncratic rules’ needed for the arrangement to be effective and efficient (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Jimenez and Tropp2018). Institutional arrangements define a ‘micro-institutional level’ (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). Moreover, what this literature is highlighting is the missing link between the macro- and micro- institutional layers (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Jimenez and Tropp2018), also defined as the ‘meso-institutional layer’ (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). This is a layer where a set of devices (entities) and mechanisms (procedures) translate, adapt, monitor, and enforce general rules, thus providing guidelines to operators and users and feedback to actors/decision-makers (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Jimenez and Tropp2018; Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). Examples of meso-institutional devices are regulatory agencies, public bureaus, local commissions, and stakeholders’ committees (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). Examples of meso-institutional mechanisms are administrative rules, guidelines, or protocols. The combination of devices and mechanisms defines different meso-institutions and makes them a key aspect in understanding and explaining policy and regulatory implementation gaps (Menard et al. Reference Ménard, Jimenez and Tropp2018). The relevance of this nascent theorization of the governance of complex systems is starting to be recognized in several empirical contexts, ranging from agriculture and food systems (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022) to water management systems and network infrastructure (Kunneke et al., Reference Kunneke, Ménard and Groenewegen2021; Vinholis et al., Reference Vinholis, Saes, Carrer and de Souza Filho2021).

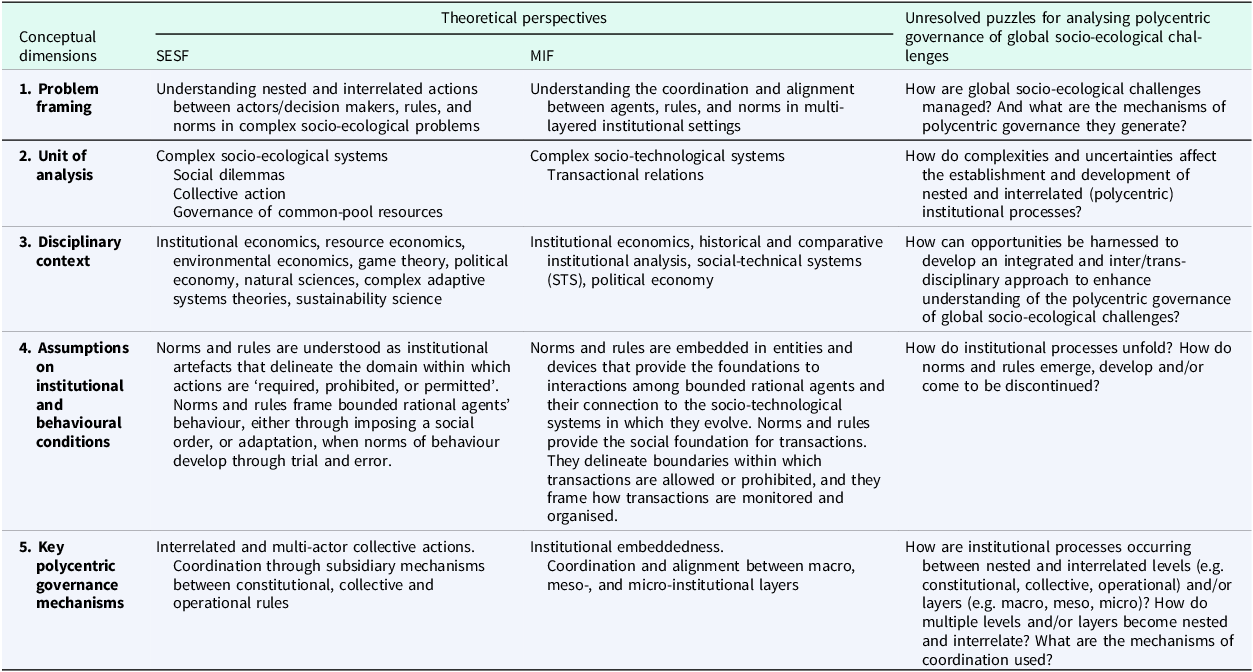

We see connections and complementarities between the SESF and the MIF relevant to investigating the polycentric governance of global socio-ecological challenges. More specifically, we suggest using a more explicit combination of SESF and MIF (Table 1) to investigate subsidiary mechanisms relevant for the establishment of polycentric institutional processes in the context of global challenges, and particularly how lower layers of institutions are defined in the absence of a macro layer, and eventually how these mechanisms can support the emergence of such a macro-institutional layer. From this perspective, there are a few similarities worth mentioning between the two frameworks. First, both SESF and MIF focus on the relevance of a systemic view to frame and analyse global challenges. From this common problem framing, we derive that global socio-ecological challenges need to be addressed through the analysis of the interrelation of institutional processes occurring simultaneously between levels (e.g. constitutional, collective, operational) or layers (e.g. macro, meso, and micro). While not perfectly overlapping, the notion of levels in the SESF and layers in MIF is comparable from the point of view of nestedness and interrelations of norms and rules relevant to actors addressing/impacted collectively by a dilemma or a challenge. Second, complexities and uncertainties are core in both frameworks to explain how social dilemmas arise and how polycentric governance emerges to manage them. Both frameworks assume that actors make decisions under conditions of bounded rationality, and in the context of high (extreme) uncertainties and complexities. Moreover, the nature of these complexities and uncertainties requires mobilizing multiple knowledge domains, and a more explicit interdisciplinary approach in the field of institutional analysis.

Table 1. Combining SESF and MIF to analyse complex socio-ecological systems

However, the two frameworks also present some key differences. First, while the SESF emphasizes more clearly the interplay between socio-economic-political and ecological settings as sources of uncertainties and complexities, the MIF more clearly defines the boundaries of different institutional layers. The latter enhances the opportunities to better analyse nested and interconnected institutional processes, particularly when transactional relations are concerned. Furthermore, the MIF adds a more distinctive role for technology, which is less prominent in the SESF, but particularly relevant to understanding transactional relations on an international and global scale. Finally, both frameworks converge in identifying global socio-ecological problems related to the management of common-pool resources and public goods. However, SESF has been overwhelmingly applied to investigate polycentric governance of natural resources, or complex SESs, such as agriculture, forestry, and fisheries. The MIF has been used to analyse resources such as water and energy, and complex systems such as food provisioning and network infrastructures.

In our view, a combined approach of these two frameworks enables institutional analysts to identify more effectively core research puzzles that appear to be unresolved in the investigation of polycentric governance of global challenges. For example, a SESF approach enhanced by a meso-institutional analysis can help to better understand coordination and alignment between individuals, organizations, and communities operating at different institutional layers, and to enact mechanisms of subsidiarity when dealing with uncertain and complex challenges, and weak or absent macro-institutions. In this way, it can help researchers to further investigate how collective polycentric governance for tackling global challenges can emerge in the absence, or strong fragmentation, of norms and rules at a constitutional level or macro layer.

Research and methodological strategy

Methodology and data collection strategy

We use the establishment and formation of MSPs to govern global challenges in agriculture and food systems as an informative empirical context to investigate how institutional processes unfold when dealing with highly uncertain and complex global challenges. In this section, we present the methodological strategy based on an abductive approach to build theory from cases (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt2019). Usually, an abductive approach is motivated by the need to explain a surprising set of empirical evidence, given extant knowledge, or to further develop an initial stage of theorization (Philipsen, Reference Philipsen2018). The subsequent stages, instead, focus on data collection and a more systematic and analysis-driven approach to support conceptualization and more granular theorizing (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt2019). In our case, the first step has been triggered by the observation of the proliferation of MSPs during the last two decades, and particularly in relation to fostering sustainability in the agriculture and food sector (Dentoni and Peterson, Reference Dentoni and Peterson2011; Dentoni et al., Reference Dentoni, Bitzer and Pascucci2016). These partnerships have been initiated by multinational corporations as a way of expanding their sustainability initiatives (Dentoni and Peterson, Reference Dentoni and Peterson2011), to support their need to strategically adapt to global socio-ecological challenges, such as climate change and biodiversity loss, and at the same time develop a variety of specific activities that are usually reported according to environmental and/or social standards (such as the UN Global Compact, the Global Reporting Initiative and the Carbon Footprint DisclosureFootnote 1 ). Going beyond bilateral partnership with certification standards (e.g. the UTZ, Rainforest Alliance, or Fairtrade), multinationals operating in global supply chains have used multi-stakeholder dialogues and alliances more strategically, and since the early 2010s, moved into a platform and partnership structure. Multinationals such as Nestlé, PepsiCo, Kraft, Coca-Cola, and Unilever, amongst others, have established several MSPs that cover multiple sectors with a focus on environmental and social sustainability (Dentoni and Peterson, Reference Dentoni and Peterson2011).

In systematically reviewing the MSPs operating in the agriculture and food sector, the focus of the research moved into more theoretical questions, for example, engaging with the organizational theory of SESs (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Kennedy, Philipp and Whiteman2017). In line with the methodological strategy, at this stage, it was necessary to select and focus on a set of in-depth and informative cases that could provide empirical illustrations of institutional processes focused on tackling global socio-ecological challenges over time (Eisenhardt and Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007). Criteria for case selection included the need to focus on partnerships dealing with socio-ecological challenges relevant to supply chain relations, the presence and leadership of large food multinationals, long-standing establishment with a global reach rather than a regional focus, and being active in several regions and biophysical contexts. Out of 42 MSPs initially mapped in our analysis, the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative Platform (SAI), the World Cocoa Foundation (WCF), and the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) were selected and analysed in further detail. These MSPs were amongst the first to be established as global partnerships, sometime between 2000 and 2004, and they had all been attempting to foster sustainable agricultural practices to enhance carbon sequestration and soil fertility, improve water management, reduce land use conducive to deforestation, and support biodiversity and diversification in farming systems (Dentoni and Peterson, Reference Dentoni and Peterson2011; Dentoni and Bitzer, Reference Dentoni and Bitzer2015).

Previous studies have looked at MSPs from a governance standpoint (Dentoni and Bitzer, Reference Dentoni and Bitzer2015), for instance framing these partnerships as collaborative arrangements in which different actors, for example from business, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and, in some cases, governments and academia, join forces to find a collective approach to tackling complex and unstructured problems that affect them all (Dentoni et al., Reference Dentoni, Pinkse and Lubberink2021). MSPs are often conceptualized as forms of private governance and deliberative structures (Mena and Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012). Consistent with this approach, SAI, WCF, and RSPO all engage in the establishment of working groups, dialogues, and roundtables to enhance cooperation and collaboration, bringing together actors with complementary resources to address issues they would be unable to address individually (Dentoni et al., Reference Dentoni, Pinkse and Lubberink2021). As Dentoni and colleagues (Reference Dentoni, Bitzer and Schouten2018) pointed out, MSPs like SAI, WCF, and RSPO often operate through networked structures and flexibility in decision-making and action, to deal with the nature of global, interrelated, and complex problems. The SAI platform, for instance, was established in 2002 by Danone, Nestlé, and Unilever as a pre-competitive collaborative space within the food and drink industry to address common challenges and promote sustainable agriculture. The platform began by helping members to navigate their way through the issues influencing the development of sustainable agriculture and to bring together knowledge from across agriculture, research, stakeholder, and supply chain management, and help make it accessible and usefulFootnote 2 . SAI stimulated member companies to come together in commodity-specific Working Groups and share information, to understand what implementing sustainable agriculture meant for business, and to define best practices and standards. Similarly, the WCF, established in 2000, initially worked to support research and education programmes related to cocoa agronomy and sustainability, from both an environmental and social perspective. In the same line, in 2004, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was established with the objective of promoting the growth and use of sustainable palm oil products through global standards and multi-stakeholder governance. All these partnerships emerged when a particular problem became urgent (Dentoni et al., Reference Dentoni, Bitzer and Pascucci2016), and collaboration was typically established among a small number of organizations, usually involving NGOs and a group of businesses who self-select to be pioneer members, either to gain reputational benefits vis-à-vis competitors or to establish a level playing field (Dentoni and Bitzer, Reference Dentoni and Bitzer2015).

In order to analyse the governance processes underpinning the establishment and development of MSPs such as the SAI, WCF, and RSPO, and in line with the abductive approach adopted in our research, an iterative process of data collection and analysis was undertaken (Philipsen, Reference Philipsen2018). Data were collected using secondary sources such as 34 academic studies (i.e. peer-reviewed publications), 56 industry reports, 21 websites, and 73 blogs and newsletters. The selected data offered sufficient insights for the purpose of this research without requiring new empirical research. All sources were integrated and triangulated according to the specific requirements suggested by evidence from the field (Eisenhardt and Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007).

Findings

Subsidiary mechanisms and polycentric governance in MSPs

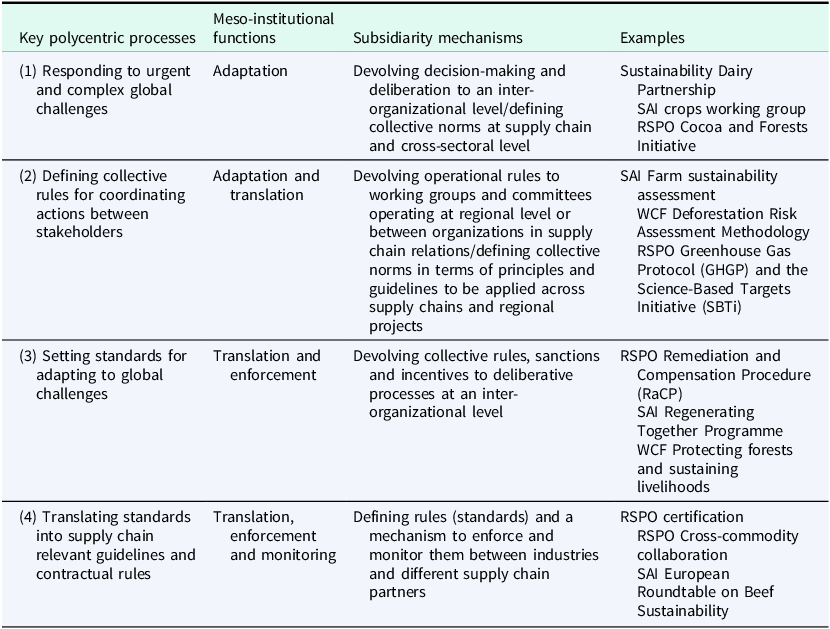

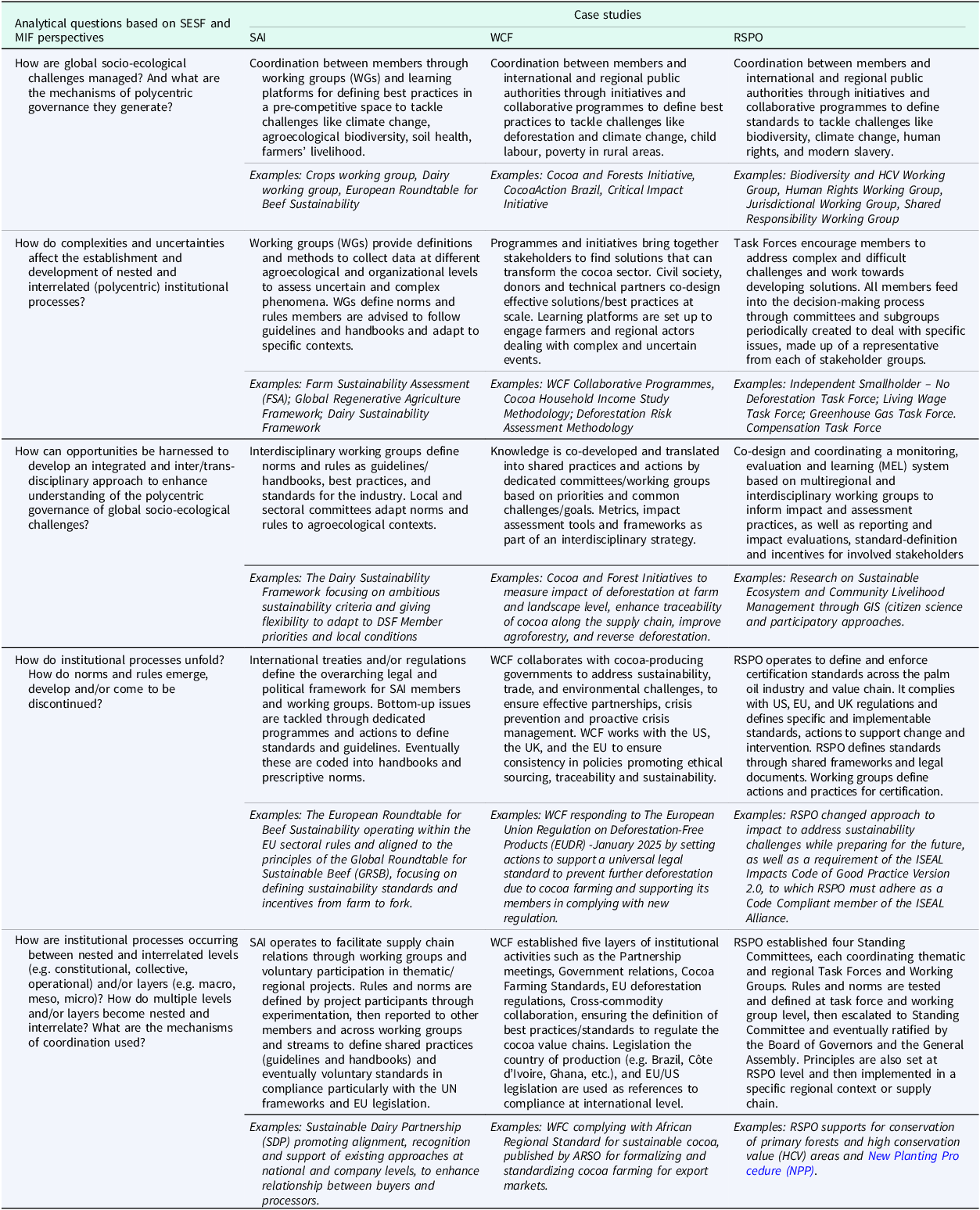

The first set of our findings (Table 2) refers to the analysis of the empirical evidence gathered in our case studies. We used the five conceptual dimensions we have identified in the section Theory background, and focused on analysing subsidiary mechanisms and polycentric governance in the SAI, WCF, and RSPO platforms throughout their formation and establishment. The first conceptual and analytical dimension identified through the SESF and MIF lenses refers to the way challenges have been framed and subsequently mobilized institutional activities. Our analysis indicates a shared pattern of problem framing between the different platforms, we have investigated, and specifically the need to respond to at least one of the global challenges that towards the end of the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s, posed severe questions on the license to operate of several multinational food companies. As widely reported in the literature we have examined, and consistent with the evidence from the SAI, WCF, and RSPO cases, the response to these global challenges has been the establishment of networked organizations, with a multi-stakeholder approach. They have all articulated subsidiary entities, mostly framed as working groups, task forces, and/or standing committees, to identify and eventually operationalize principles and practices of sustainable agriculture. Climate change and biodiversity loss are overwhelmingly the ecological challenges addressed by the SAI, WCF, and RSPO platforms, while social challenges such as fairness in supply chain relations and eradication of child labour practices are the most represented in terms of institutional activities and rule-making, particularly.

Table 2. Key subsidiary mechanisms in the analysed MSPs

The second dimension refers to the way complexities and uncertainties have been managed and how they shaped institutional processes inside and outside the platforms. Our findings highlight that a multi-layered structure has been adopted in all platforms through an agile and adaptable approach: while principles are identified and adopted at platform level, and through the influence of their members, best practices and guidelines emerge from working groups and task forces, often considering local or regional circumstances. These activities often focus on the identification and implementation of voluntary standards, monitoring mechanisms, and impact assessment tools. The key approach is to delegate actions to groups of members working locally, to adapt to agroecological and socio-economic conditions, but under a unified framework of rules and norms, often codified in handbooks and guidelines. For example, the SAI platform has introduced the Farm Sustainability Assessment (FSA) as part of the actions supported by the SAI Farm Management Group (FMG), reporting to different working groups (e.g. the Crops Working Group), to assess, improve, and validate on-farm sustainability. The FSA is a tool that farmers and members can use to identify and track the progress of sustainable farming practices at the farm level. It is in line with global best practice and can be used for any crop, anywhere in the world. Members engaging with the FSA align and coordinate their activities from farm to fork and go through a process of voluntary assessment and monitoring. The FSA constitutes a framework to standardize data and information, such that learning platforms in SAI can use these sources to experiment with other groups around the world. A similar approach has been used in the Global Regenerative Agriculture Framework and the Dairy Sustainability Framework.

The third conceptual and analytical dimension engages with the type of knowledge the platforms use to develop subsidiary mechanisms and support polycentrism. Our findings indicate that SAI, WCF, and RSPO extensively use multi- and interdisciplinary methods to inform their change-making actions, to align and coordinate tasks between members and across working groups. A science-based approach leads to how they operate and tackle global challenges. For example, the WCF has launched and established the Cocoa and Forest Initiatives to measure the impact of deforestation at the farm and landscape level, to enhance traceability of cocoa along the supply chain, improve agroforestry, and reverse deforestation regionally. These initiatives are designed through interactions with multiple scientists, practitioners, and knowledge flows are adapted to practices relevant to the local context. Similar approaches are supported by SAI and RSPO. They all appear to create opportunities for adaptation and mitigation by first testing practices in a small-scale setting, coordinating activities between soil scientists, climatologists, ecologists, agronomists, and business management experts, and then deriving more generalizable actions, rules, and norms to update handbooks and guidelines useful for members operating in other countries and supply chains. This approach also informs our analysis of the core institutional and behavioural premises used by the platforms to operate, and more practically, how they develop, establish, and eventually dismiss rules and norms.

Our findings highlight the presence of ‘cycles’ of institutional processes, which follow both a top-down and bottom-up approach. In all three platforms, for example, working groups and task forces are established through executive decisions and rules, aligned with common and shared principles and practices. Working groups respond to urgent needs of members, represented by interest groups within the platform, and through the general assembly of members and core teams, all reporting to or informing a board of directors or executive team. The RSPO is a striking example of this approach when task forces and committees have been established to harmonize and standardize approaches related to sustainability practices in the palm oil sector. However, the initial top-down mechanism is then followed, sequentially, by the feedback that the working groups/standing committees provide, based on the experimentations of members in dedicated projects, often in specific locations and/or supply chains. This feedback informs processes of revision and refinement of the general rules and norms, such that handbooks, guidelines, and principles can be adapted to the changing circumstances, constituencies, and needs. Based on all these analytical and conceptual dimensions, we have been able to identify four key polycentric processes and meso-institutional functions, all based on principles of subsidiarity and coordination between actors operating at different institutional layers. Since this represents the core of our findings and directly tackles our research questions, we present them more in-depth in the following section.

Key polycentric and meso-institutional processes

We have further investigated the emergence of meso-institutional processes related to how MSPs tackle global socio-ecological challenges. Our findings indicate that when macro-institutions (e.g. general/constitutional rules) are absent or weak, for example, in the absence of international laws and regulations, and in the presence of severe uncertainties and complexities, firms seek to enact meso-institutional processes through MSPs, which result in the formation and establishment of a polycentric governance of global challenges. More specifically, our analysis highlights that MSPs such as the SAI, WCF, and RSPO apply subsidiary principles and mobilize meso-institutional processes of translation, adaptation, monitoring, and enforcement. The key finding is that in the presence of global socio-ecological challenges, MSPs implement these processes to define and shape different institutional layers. However, since a macro-institutional layer is absent or very fragmented, MSPs systematically begin by adapting to these institutional conditions (process 1) and forming a layer of collective rules that compensate for the absence of general and constitutional rules (process 2). MSPs then translate collective rules into standards and procedures (process 3) that can be used in supply chain and contractual settings, supporting processes of monitoring and enforcement at the supply chain level (process 4). We describe the four processes below and give an overview in Table 3.

Table 3. Key polycentric processes and meso-institutional functions

Process 1 – Responding to global challenges by forming a meso-institutional layer

The RSPO, SAI, and WCF were all established by the largest multinational food companies, in collaboration with public authorities and governments, NGOs, and research organizations, in response to an urgent and immediate challenge, such as climate change or biodiversity loss, entailing an unprecedented level of complexity and uncertainty. This required the involvement of multiple actors, and in the absence of international rules and regulations. Consistent with evidence from other studies, the initiation of the SAI, RSPO, and WCF corresponds to the globalization of food supply chains. For example, when establishing the RSPO in the early 2000s, Unilever was confronted with the complexity and uncertainty of resolving the trade-off between palm oil production and deforestation (Whiteman et al., Reference Whiteman, Walker and Perego2013). Environmental NGOs, such as the WWF, were advocating for a ban on the trading of products that incentivizing plantations at the expense of primary rainforests. As reported by Dentoni and colleagues (Reference Dentoni, Bitzer and Schouten2018: 340) ‘priority in the newly founded RSPO was given to establishing credible sustainability criteria that were acceptable to all stakeholders’. Similarly, companies engaged in the establishment of the SAI and WCF were interested in mitigating the risk of investing in practices supporting sustainable agriculture without a clear legal and regulatory pathway to claim them in terms of brand reputation and marketing strategies.

Process 2 – Defining collective rules for coordinating actions between stakeholders

After their establishment and during their consolidation, SAI, WCF, and RSPO have progressively focused on defining collective rules to address enhanced coordination, and mitigate conflicting views and values among involved actors, inside and outside the partnership. Particularly, MSPs have defined rules to support deliberative and consultative decision-making and codified guidelines and protocols. For example, in the SAI platform and WCF, deliberative negotiation processes were pivotal in the definition of common guidelines, handbooks, and codes of conduct. The RSPO, for example, developed expert committees to collectively manage value conflict related to the impact of palm oil production practices. Often, mitigation of conflictual views entailed the establishment of working groups aimed at interpreting and synthesizing the diversity of values informing and motivating the stakeholders in and outside the platform. These processes resulted in the establishment of rules that had a much-defined focus on the scope and impact of the stakeholders’ activities and how much they were influencing or were affected by the problem they intended to manage. For example, the SAI platform worked on water management practices in relation to prolonged droughts, crop diversification, soil health, and crop rotation, and enhancement of biodiversity to support resilience of agri-food systems.

Process 3 – Setting standards for adapting to global challenges

Subsequently, MSPs such as SAI, WCF, and RSPO have operationalized those rules by devising standards to codify practices involving multinational companies and other actors cutting across different societal sectors and multiple supply chains. Evidence-based practices deriving from specific projects and working groups have been systematically used to define standards, guidelines, assessment tools, and protocols for the stakeholders involved. In parallel, standards developed and scaled across supply chains have been coupled with assessment tools and guidelines to enforce standards more generally (Dentoni et al., Reference Dentoni, Bitzer and Schouten2018). In the RSPO, standardized methods and toolkits have been used to enforce member decisions. For example, the standardization of measurements of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, soil fertility, and biodiversity enhancements have all been subject to standardization in the SAI, RSPO, and WCF. Moreover, self-assessment and reporting tools have largely been co-developed in these platforms based on data collection and analysis defined by the standards of the involved actors.

Process 4 – Translating standards into supply chain-relevant guidelines and contractual rules

The establishment of standards helped multinational companies in MSPs to make global socio-ecological challenges more tractable, leading to adopt rules applicable in commercial contexts, and particularly in supply chain contracts. These rules have become increasingly relevant to regulating actions undertaken in the production, distribution, and consumption of key agricultural/food commodities. The RSPO and WCF translated these processes into voluntary guidelines and standards for the organization of their supply chains. SAI platform members had used these rules to support some flexible networking in their supply chain and procurement strategies, to source from multiple locations using similar standards. In the specific case of the SAI platform, for example, codifying practices, guidelines, and principles informed other initiatives outside the platform and clearly became the global reference for best practices in sustainable agriculture. This set of codified principles was then translated into more fine-grained contractual rules, so that they could be used in emerging farming and commercial practices. These rules are not legally binding in a general sense, because they are based on ‘best practices’ and rely on principles of collective legitimacy and voluntary actions, but become visible and enforceable constraints for the actors operating at supply chain level, so in a ‘micro-institutional layer’, for example, they limit or enhance the set of farming practices, as well as their supply chain relations, and contractual obligations.

More generally, through our analysis of the MSPs, we suggest the emergence of a polycentric meso-institutional governance of global challenges, in which organizational practices (micro/idiosyncratic rules) tested through multi-stakeholder platforms are defined and operationalized under absent or severely fragmented macro-institutions. As the SAI, WCF, and RSPO cases have demonstrated, platforms can be recognized as sites of rule-making rather than an arena for planning and implementation of pre-existing rules. MSPs operate as a network of actors where operational rules, for example, practices of carbon sequestration, water management, soil restoration, and crop diversification, are discussed, and through collective deliberation translated into industry standards, applicable to different decision-making and biophysical contexts. This is a process enhanced by subsidiarity mechanisms.

Towards a meso-institutional theory of polycentric governance of global challenges

Starting from our findings and the initial theorizing, we moved into constructing a meso-institutional theory of polycentric governance of global socio-ecological challenges. In our theorizing, we move beyond the current approach to meso-institutions that assume a rather hierarchical, and to a certain extent ‘linear’ institutional dynamics, to explain institutional embeddedness (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). In the current approach, in fact, it is assumed that macro-institutions are set as necessary conditions (e.g. general rules) to regulate the allocation and usage of rights supporting social and economic actors to organize, exchange, and access resources and transact. Second, it is assumed that meso-institutions adapt these general rules to the specific context and/or conditions while micro-institutions organize, following the general rules to operationalize the production, distribution, provisioning, and consumption of goods and services (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). The underpinning assumption is the presence of a ‘well-defined’ institutional environment, and particularly a macro-institutional layer, where general rules are devised, such that socio-economic actors can follow them. This assumption is also present in the SESF (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2009b), where constitutional rules constrain collective rules, which, in turn, constrain operational rules (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2011). However, as our research has demonstrated, these are conditions far from being represented when actors are dealing with global socio-ecological challenges, which often undermine the principles of how to design effective collective governance (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Arnold and Villamayor-Tomas2010; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Ostrom and Cox2013). MSPs operate in uncertain and complex conditions, affecting actors operating at different institutional levels and biophysical contexts. In these conditions, MSPs help to enact principles of subsidiarity and to establish an effective level of coordination in large and interrelated networks of social and ecological relations, even if a macro-institutional layer is absent. According to our research, in fact, a polycentric meso-institutional governance is enhanced through subsidiary processes of coordination in which actors in MSPs become rule-makers and takers, by working together to deliberate on challenges for which they have no unique and final solution(s) or outcome(s). As our cases have demonstrated, MSPs perform key meso-institutional functions, despite the absence or weakness of macro-institutions, and the complexity and uncertainty of the challenges they are dealing with. In our view, these findings can be used to define an extended conceptual framework and expand our understanding of polycentric governance of socio-ecological challenges through a meso-institutional perspective (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). We claim that this approach provides two contributions to extend the institutional theory of polycentric governance. First, we suggest that the assumption that an ‘institutional environment’ is always well-defined and ‘distinguishable’ from the context of ‘institutional arrangements’ should be more explicitly challenged. Through our analysis of MSPs, we have seen, in fact, that rules at the macro-institutional level can be ill-defined, fragmented, or absent, due to the complexity of the problem they try to regulate, or its novel and/or emergent nature. These general rules are often fragmented and not formally codified in regulatory or policy frameworks. Equally, more informal and culturally informed norms are not yet in place, mostly because of the conflictual views different actors have about the problem, its emergent nature, novelty, and ambiguity.

Second, as our findings have highlighted, collective partnerships around global challenges result in the formation of meso-institutions, such as MSPs, where more operational rules (e.g. practices) are identified, enforced, and monitored, and then translated into codified rules (e.g. standards). In our case, guidelines for sustainable agriculture and farming, handbooks shared by several farmers and organizations in the supply chain (see Weituschat et al., Reference Weituschat, Pascucci, Materia and Caracciolo2023 for an overview), are examples of how subsidiary mechanisms define nested and interrelated institutional relations, allocating decision rights at different institutional layers. Handbooks and codes of conduct are formalized rules that help multinational companies manage supply chain relations and connect these rules to a wider context, where further alignment and generalization are enacted through (voluntary) industry standards. If we look at this institutional process, we can notice that the emergence of meso-institutional functions creates ‘connections’ between rules at different institutional levels and eventually helps to define a nascent macro-institutional level. These findings expand the initial conceptualization of meso-institutional functions (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022) as well as extend the idea of institutional embeddedness based on coordination mechanisms and alignment. Particularly, we have defined a sequence of polycentric meso-institutional processes in which first actors define and establish collective rules to tackle global challenges, increasing their alignment and coordination, and then translate these rules into standards, and enforce and monitor them, further increasing alignment and coordination in contractual settings. These institutional dynamics indicate that actors attempting to manage complex socio-ecological challenges need to define general principles and guidelines, using meso-institutions as a ‘means-to-an-end’. Moreover, our findings indicate that meso-institutional devices are not solely constituted by local commissions, regulatory agencies, or stakeholders’ bureaus or committees (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022), or made up of mechanisms such as administrative rules, guidelines or protocols, but also operate as collective engagement, through deliberative platforms and networks, such as MSPs.

Our theorization is not limited to the MIF but attempts to extend our understanding of the polycentric governance of complex SESs more generally. In line with the burgeoning literature on governance of global socio-ecological challenges (Lam, Reference Lam2006; Roggero et al., Reference Roggero, Bisaro and Villamayor-Tomas2018; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Carpenter, Rockstrom, Crépin and Peterson2012), our contribution aims at recognizing the relevance and ubiquity of contemporary socio-ecological challenges to explain forms of polycentric governance at a global scale. What appears to be the key promising dimension of our theoretical framework is its capacity to unpack different institutional layers and help to understand how subsidiarity manifests in the definition of rules generated and shaped at different institutional layers. In this perspective, our approach adds to SESF by further enhancing the opportunity for theory-building and testing in multiple and diverse institutional and socio-ecological conditions. For example, it creates an opportunity to theorize about institutional change in the context of extreme uncertainty and complexity. As indicated by Ostrom, the framework she helped to define has emerged around the idea of resolving social dilemmas instilled by ‘well-defined challenges’, such as managing a lake, a forest, or fishing stocks (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a). These are contexts where decision-makers take, make, and shape rules while dealing with manageable levels of complexity and uncertainty. Moreover, they build on cultural norms, or traditions and beliefs accumulated through historical patterns and mechanisms, and a pre-existing set of strategies and rules. This is due to the long-standing nature of the problem and the need for the decision-makers to cope and adapt over time. Instead, socio-ecological challenges are becoming increasingly unpredictable, volatile, and ambiguous, manifesting at unprecedented scales, triggering the need for information and knowledge that are not ready to be used in decision-making processes. As such, global socio-ecological challenges entail extreme levels of adaptation with a pace that might be difficult to predict for the involved actors and decision-makers. We advance an opportunity to further theorize polycentric governance in contexts of unstructured problems, where volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity are severe, the scale of the problem unprecedented, and the knowledge about the problem is limited and bounded to decision-makers, while general rules do not exist and/or struggle to emerge.

Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a theoretical framework to better understand the polycentric governance of global socio-ecological challenges through the lenses of meso-institutional analysis (Menard et al., Reference Ménard, Martino, de Oliveira, Royer, Saes and Schnaide2022). Our approach has been able to start underpinning institutional processes that define socio-ecological challenges and particularly the interconnection between social (institutional) and ecological processes. Moreover, our approach helps institutional scholars to better investigate and understand how markets, firms, and communities can cope with ‘complex uncertainties’ and align with planetary SESs. We also claim that this effort defines an emerging interdisciplinary field where institutional theories related to the polycentric governance of socio-ecological challenges are defined by the contribution of different fields of institutional inquiries. Our work contributes to the still emerging literature on the governance of MSPs, used as an empirical context where collective and collaborative engagements define actions (e.g. partnerships) among businesses, governments, and civil society organizations to address complex social and ecological challenges (Dentoni et al., Reference Dentoni, Pinkse and Lubberink2021). We have looked at these partnerships through the lenses of meso-institutional functions. Our analysis of the formation and establishment of MSPs, in the context of global challenges, has been used to theorize meso-institutional functions in the context of weak macro-institutional settings. Extending our initial theorizing to various forms of partnerships, such as intersectoral partnerships, social alliances, and multi-stakeholder strategic partnerships, creates the opportunity to define the foundations for a new wave of research and theorizing about MSPs as meso-institutions. Despite the limitations of our work, and namely, the potential idiosyncratic nature of the MSPs in food and agriculture, such as the SAI, WCF, and RSPO, and the related empirical evidence, we believe that this approach is conducive to more theory development about collective partnerships as a means to tackle a wide set of global socio-ecological crises. Our work, despite being inherently theoretical, also stimulates reflections on more specific challenges affecting the agriculture and food sector, where the establishment of several MSPs with the involvement of multinational corporations, international NGOs, and universities has skyrocketed during the last two decades. We believe that this is an exercise that can support the design of novel institutions to better manage and govern the socio-ecological challenges humanity is facing.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his gratitude to Domenico Dentoni for his inspiring work on the exploration of multistakeholder partnerships and the governance of global challenges and wicked problems. The author is grateful to the organisers of the ‘Pirates series’ where an early draft of this work was presented and discussed. Special gratitute goes to Lisbeth Dries, Anna Grandori, Kostas Karantininis, Gaetano Martino, Valentina C Materia, Claude Menard, Annie Royer, and Sophia Weituschat for initial comments on an early draft of this manuscript, and to the editor of the special issue and two referees for their very useful comments.

Case study documents

SAI Platform – Sustainable Agriculture Initiative Platform

A global partnership to make palm oil sustainable – Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)

Collaboration. Impact. Sustainability. – World Cocoa Foundation